User login

What to do when a patient presents with breast pain

Breast pain is one of the most common breast-related patient complaints and is found to affect at least 50% of the female population.1 Most cases are self-limiting and are related to hormonal and normal fibrocystic changes. The median age of onset of symptoms is 36 years, with most women experiencing pain for 5 to 12 years.2 Because the cause of breast pain is not always clear, its presence can produce anxiety in patients and physicians over the possibility of underlying malignancy. Although breast cancer is not associated with breast pain, many patients presenting with pain are referred for diagnostic imaging (usually with negative results). The majority of women with mastalgia and normal clinical examination findings can be reassured with education about the many benign causes of breast pain.

What are causes of breast pain without an imaging abnormality?

Hormones. Mastalgia can be focal or generalized and is mostly due to hormonal changes. Elevated estrogen can stimulate the growth of breast tissue, which is known as epithelial hyperplasia.3 Fluctuations in hormone levels can occur in perimenopausal women in their forties and can result in new symptoms of breast pain.4 Sometimes starting a new contraceptive medication or hormone replacement therapy can exacerbate the pain. Switching brands or medications may help. Another cause of mastalgia may be elevated prolactin levels, with hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction.5,6

Diet. There is evidence to link a high-fat diet with breast pain. The pain has been shown to improve when lipid intake is reduced and high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are normalized. As estrogen is a steroid hormone that can be synthesized from lipids and fatty acids, elevated lipid metabolism can increase estrogen levels and exacerbate breast pain symptoms.7,8 Essential fatty acids, such as evening primrose oil and vitamin E, have been used to treat mastalgia because they reduce inflammation in fatty breast tissue through the prostaglandin pathway.9,10

Caffeine. Methylxanthines can be found in coffee, tea, and chocolate and can aggravate mastalgia by enhancing the cyclin adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway. This pathway stimulates cellular proliferation and fibrocystic changes which in turn can exacerbate breast pain.11

Smoking. In my clinical practice I have clearly noted a higher incidence of breast pain in patients who smoke. The pain tends to improve significantly when the patient quits or even cuts back on smoking. The exact reasons for smoking’s effects on breast pain are not well known; however, they are thought to be related to acceleration of the cAMP pathway.

Large breast size. Very large breasts will strain and weaken the suspensory ligaments, leading to pain and discomfort. It has been shown that wearing a supportive sports bra during episodes of breast pain is effective.

Types of breast pain

Cyclical

Women with fibrocystic breasts tend to experience more breast pain. Breast sensitivity can be localized to the upper outer quadrants or to the nipple and sub-areolar area. It also can be generalized. The pain tends to peak with ovulation, improve with menses, and to recur every few weeks. Patients who have had partial hysterectomy (with ovaries in situ) or endometrial ablation will be unable to correlate their symptoms to menstruation. Therefore, women are encouraged to keep a diary or calendar of their symptoms to detect any correlation with their ovarian cycle. Such correlation is reassuring.

Continue to: Noncyclical...

Noncyclical

Noncyclical breast pain is not associated with the menstrual cycle and can be unilateral or bilateral. Providers should perform a good history of patients presenting with noncyclicalbreast pain, to include character, onset, duration, location, radiation, alleviating, and aggravating factors. A physical examination may elicit point tenderness at the chest by pushing the breast tissue off of the chest wall while the patient is in supine position and pressing directly over the ribs. Lack of tenderness on palpation of the breast parenchyma, but pain on the chest wall, points to a musculoskeletal etiology. Chest wall pain may be related to muscle spasm or muscle strain, trauma, rib fracture, or costochondritis (Tietze syndrome). Finally, based on history of review of systems and physical examination, referred pain from biliary or cardiac etiology should be considered.

When breast pain occurs with skin changes

Skin changes usually have an underlying pathology. Infectious processes, such as infected epidermal inclusion cyst, hidradenitis of the cleavage and inframammary crease, or breast abscess will present with pain and induration with an acute onset of 5 to 10 days. Large pendulous breasts may develop yeast infection at the inframammary crease. Chronic infectious irritation can lead to hyperpigmentation of that area. Eczema or contact dermatitis frequently can affect the areola and become confused with Paget disease (ductal carcinoma in situ of the nipple). With Paget, the excoriation always starts at the nipple and can then spread to the areola. However, with dermatitis, the rash begins on the peri-areolar skin, without affecting the nipple itself.

When breast pain occurs with nipple discharge

Breast pain with nipple discharge usually is bilateral and more common in patients with significant fibrocystic changes who smoke. If the nipple discharge is bilateral, serous and non-bloody, and multiduct, it is considered benign and physiologic. Physiologic nipple discharge can be multifactorial and hormonal. It may be related to thyroid disorders or medications such as antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, or antipsychotics. The only nipple discharge that is considered pathologic is unilateral spontaneous bloody discharge for which diagnostic imaging and breast surgeon referral is indicated. Women should be discouraged from self-expressing their nipples, as 80% will experience serous nipple discharge upon manual self-expression.

Breast pain is not associated with breast cancer. Most breast cancers do not hurt; they present as firm, painless masses. However, when a woman notices pain in her breast, her first concern is breast cancer. This concern is re-enforced by the medical provider whose first impulse is to order diagnostic imaging. Yet less than 3% of breast cancers are associated with breast pain.

There have been multiple published retrospective and prospective radiologic studies about the utility of breast imaging in women with breast pain without a palpable mass. All of the studies have demonstrated that breast imaging with mammography and ultrasonography in these patients yields mostly negative or benign findings. The incidence of breast cancer during imaging work-up in women with breast pain and no clinical abnormality is only 0.4% to 1.8%.1-3 Some patients may develop future subsequent breast cancer in the symptomatic breast. But this is considered incidental and possibly related to increased cell turnover related to fibrocystic changes. Breast imaging for evaluation of breast pain only provides reassurance to the physician. The patient's reassurance will come from a medical explanation for the symptoms and advice on symptom management from the provider.

Researchers from MD Anderson Cancer Center reported imaging findings and cost analysis for 799 patients presenting with breast pain from 3 large network community-based breast imaging centers in 2014. Breast ultrasound was the initial imaging modality for women younger than age 30. Digital mammography (sometimes with tomosynthesis) was used for those older than age 30 that had not had a mammogram in the last 6 months. Breast magnetic resonance imaging was performed only when ordered by the referring physician. Most of the patients presented for diagnostic imaging, and 95% had negative findings and 5% had a benign finding. Only 1 patient was found to have an incidental cancer in the contralateral breast, which was detected by tomosynthesis. The cost of breast imaging was $87,322 in younger women and $152,732 in women older than age 40, representing overutilization of health care resources and no association between breast pain and breast cancer.4

References

- Chetlan AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

- Arslan M, Kücükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

- Noroozian M, Stein LF, Gaetke-Udager K, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in women with breast pain in the absence of additional clinical findings: Mammography remains indicated. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:417-424.

- Kushwaha AC, Shin K, Kalambo M, et al. Overutilization of health care resources for breast pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018; 211:217-223.

Management of mastalgia

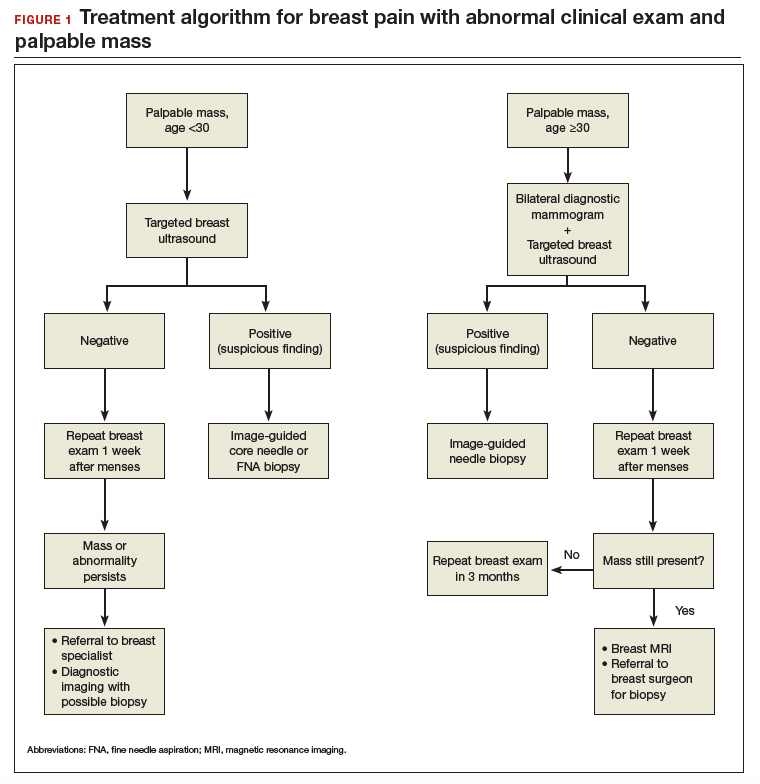

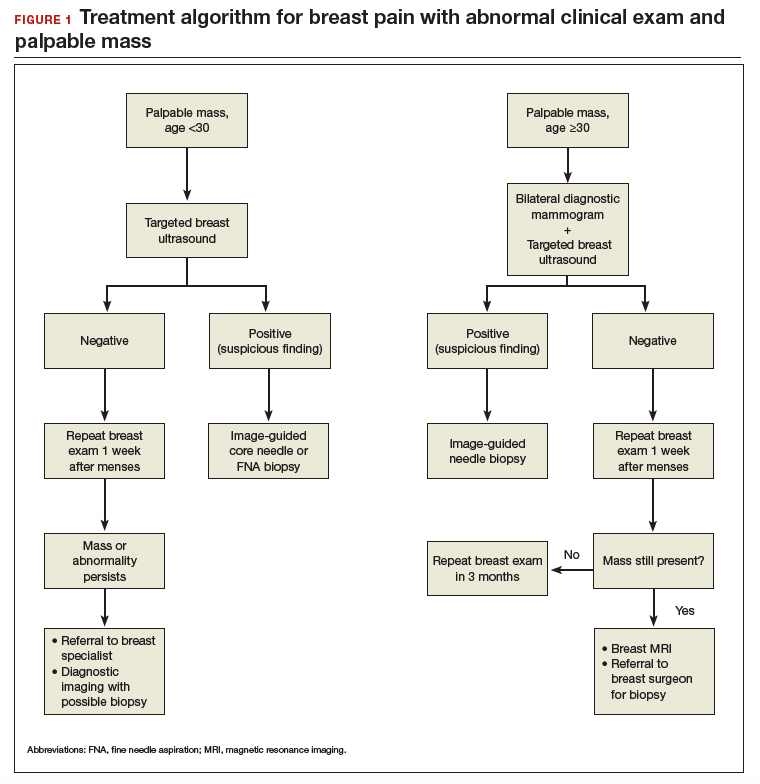

Appropriate breast pain management begins with a good history and physical examination. The decision to perform imaging should depend on clinical exam findings and not on symptoms of breast pain. If there is a palpable mass, then breast imaging and possible biopsy is appropriate. However, if clinical exam is normal, there is no indication for breast imaging in low-risk women under the age of 40 whose only symptom is breast pain. Women older than age 40 can undergo diagnostic imaging, if they have not had a negative screening mammogram in the past year.

Breast pain with abnormal clinical exam

In the patient who is younger than age 30 with a palpable mass. For this patient order targeted breast ultrasound (US) (FIGURE 1). If results are negative, repeat the clinical examination 1 week after menses. If the mass is persistent, refer the patient to a breast surgeon. If diagnostic imaging results are negative, consider breast MRI, especially if there is a strong family history of breast cancer.

In the patient who is aged 30 and older with a palpable mass. For this patient, bilateral diagnostic mammogram and US are in order. The testing is best performed 1 week after menses to reduce false-positive findings. If imaging is negative and the patient still has a clinically suspicious finding or mass, refer her to a breast surgeon and consider breast MRI. At this point if there is a persistent firm dominant mass, a biopsy is indicated as part of the triple test. If the mass resolves with menses, the patient can be reassured that the cause is most likely benign, with clinical examination repeated in 3 months.

Continue to: Breast pain and normal clinical exam...

Breast pain and normal clinical exam

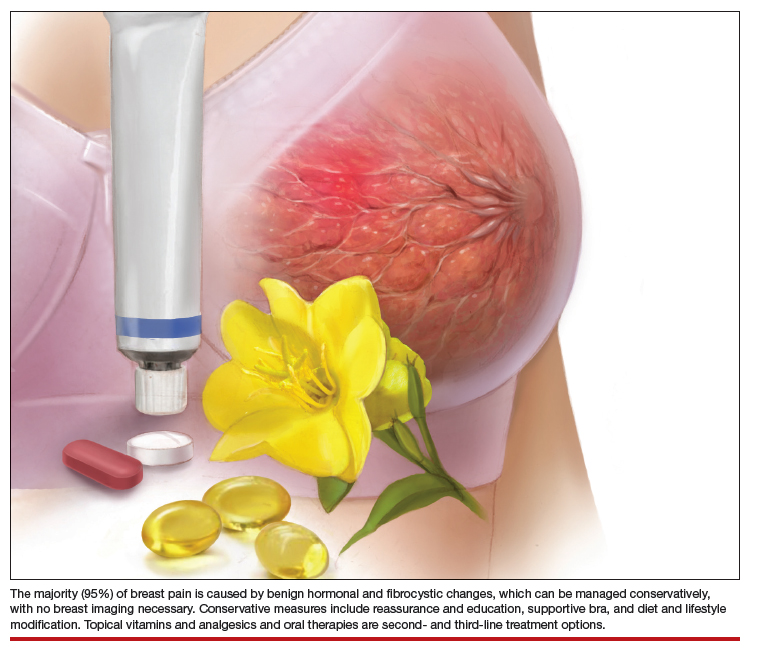

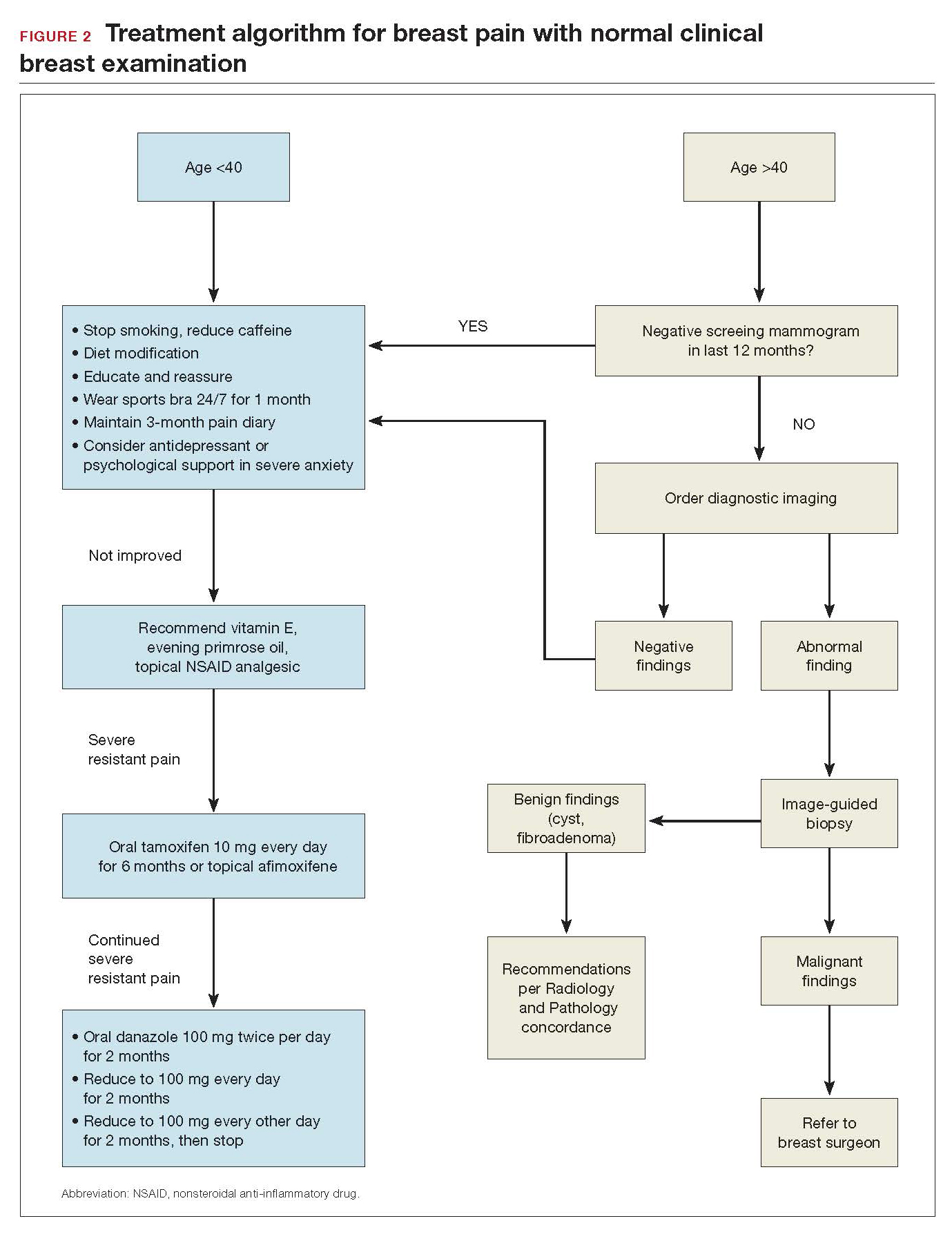

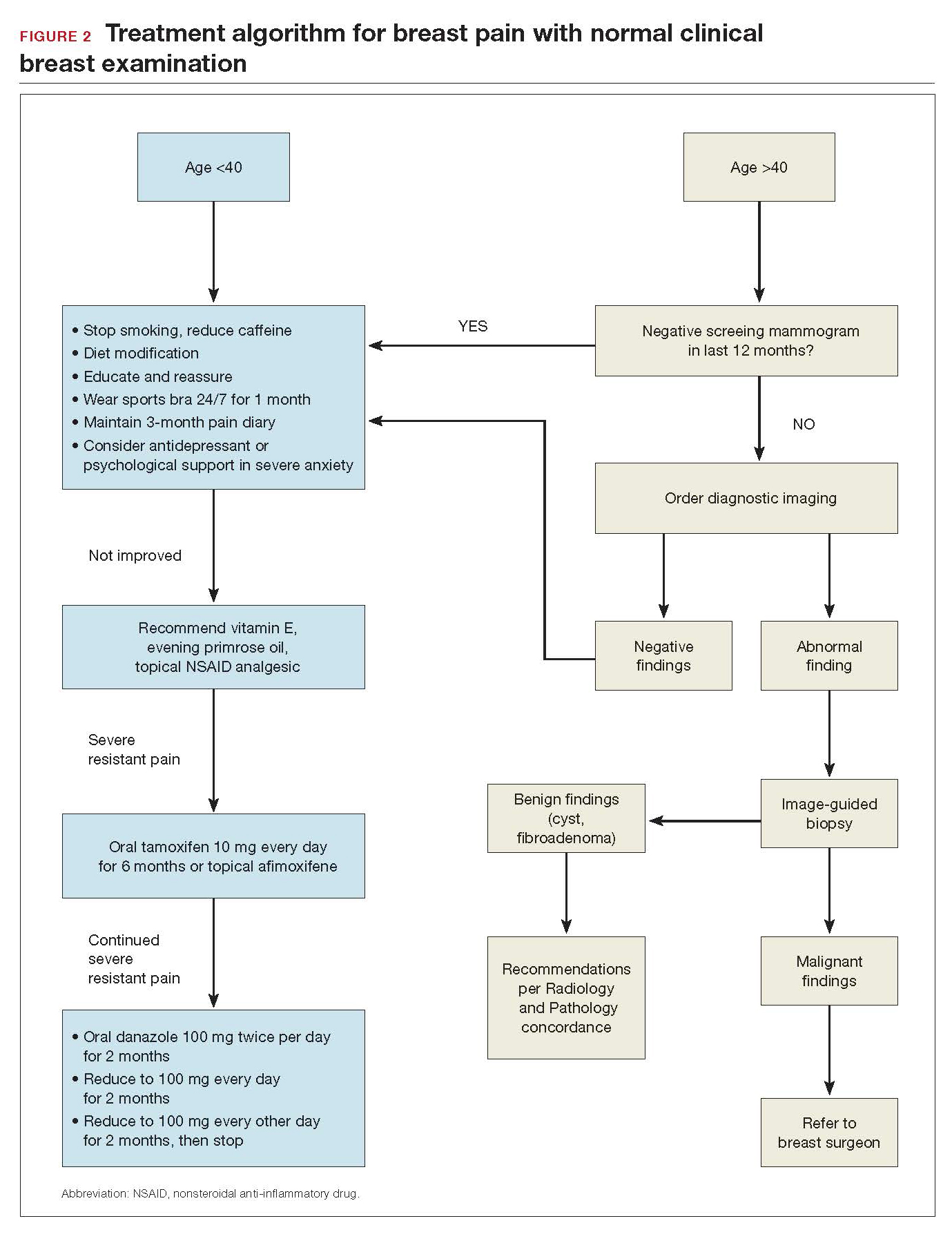

When women who report breast pain have normal clinical examination findings (and have a negative screening mammogram in the past 12 months if older than age 40), there are several management strategies you can offer (FIGURE 2).

Reassurance and education. The majority of women with breast pain can be managed with reassurance and education, which are often sufficient to reduce their anxieties.

Supportive bra. The most effective intervention is to wear and sleep in a well-fitted supportive sports bra for 4 to 12 weeks. In a nonrandomized single-center trial of danazol versus sports bra, 85% of women reported relief of their breast pain with bra alone (vs 58% with danazol).12 A supportive bra is the first-line management of mastalgia (Level II evidence).

Symptom diary/calendar. Many women do not know whether or not their symptoms correspond to their ovarian cycle or are related to hormonal fluctuations. Therefore, it is reassuring and informative for them to keep a calendar or a diary of their symptoms to determine whether their symptoms occur or are exacerbated in a cyclical pattern.

Diet and lifestyle modification. Women should avoid caffeine (especially when having pain). Studies on methylxanthines have demonstrated some symptom relief with reducing caffeine intake.11,13 One cup of coffee or tea per day most likely will not make a difference. However, if a woman is drinking large quantities of caffeinated beverages throughout the day, it will very likely improve her breast pain if she cuts back. This is especially true during the times of exacerbated pain prior to her menses.

In addition, recommend reduced dietary fat (overall good health). This is good advice for any patient. There were 2 small studies that showed improvement in breast pain with a 15% reduction in dietary fat.7,8

Finally, advise that patients stop smoking. Smoking aggravates and exacerbates fibrocystic changes, and these will lead to more breast pain.

Medical management. Over-the-counter medications that are found in the vitamin section of a local drug store are vitamin E and evening primrose oil. There are no significant adverse effects with these treatments. Their efficacy is theoretical, however; 3 randomized controlled trials demonstrated no significant clinical benefit with evening primrose oil versus placebo for treatment of mastalgia.14

Topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; Voltaren gel, topical compound pain creams) are useful as second-line management after using a supportive bra. Three randomized controlled trials have demonstrated up to 90% improvement of mastalgia with topical NSAIDs.15-17

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM), which is an antagonist to the estrogen receptor (ER) in the breast and an agonist to the ER in the endometrium. Tamoxifen has been found to reduce symptoms of mastalgia by 70% even at a lower dosage of 10-mg per day (for 6 months), or as a topical gel (afimoxifene). The oral form can have some adverse effects, including hot flashes, and has a low risk for thromboembolic events and endometrial neoplasia.18-20

Danazol is very effective in reducing breast pain symptoms (by 80%), with a higher relapse after stopping the medication. Danazol is less tolerated due to its androgenic effects, such as hirsutism, acne, menorrhagia, and voice changes. Both danazol and tamoxifen can be teratogenic and should be used with caution in women of child-bearing age.21

Finally, bromocriptine inhibits serum prolactin and has been reported to provide 65% improvement in breast pain. Its use for breast pain is not US Food and Drug Administration–approved and adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, and hypotension.22

Tamoxifen, danazol, and bromocriptine can be considered as third-line management options for severe treatment-resistant mastalgia.

Continue to: FIGURE 2 Treatment algorithm for breast pain...

In summary

Evaluation and counseling for breast pain should be managed by women’s health care providers in a primary care setting. Most patients need reassurance and medical explanation of their symptoms. They should be educated that more than 95% of the time breast pain is not caused by an underlying malignancy but rather due to hormonal and fibrocystic changes, which can be managed conservatively. If the clinical breast examination and recent screening mammogram (in women over age 40) results are negative, patients should be educated that their pain is benign and undergo a trial of conservative measures: wear and sleep in a supporting bra; keep a calendar of symptoms to determine any relation to cyclical changes; and avoid nicotine, caffeine, and fatty food. Topical pain creams with diclofenac and evening primrose oil also can be effective in ameliorating the symptoms. Breast pain is not a surgical disease; referral to a surgical specialist and diagnostic imaging can be unnecessary and expensive.

- Scurr J, Hedger W, Morris P, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of breast pain in the general population. Breast J. 2014;20:508-513.

- Davies EL, Gateley CA, Miers M, et al. The long-term course of mastalgia. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:462-464.

- Singletary SE, Robb GL, Hortobagy GN. Advanced Therapy of Breast Disease. 2nd ed. Ontario, Canada: BC Decker Inc.; 2004.

- Gong C, Song E, Jia W, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of toremifen therapy for mastaglia. Arch Surg. 2006;141:43-47.

- Kumar S, Mansel RE, Scanlon MF, et al. Altered responses of prolactin, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone secretion to thyrotrophin releasing hormone/gonadotrophin releasing hormone stimulation in cyclical mastalgia. Br J Surg. 1984;71:870-873.

- Mansel RE, Dogliotti L. European multicentre trial of bromocriptine in cyclical mastalgia. Lancet. 1990;335:190-193.

- Rose DP, Boyar AP, Cohen C, et al. Effect of a low-fat diet on hormone levels in women with cystic breast disease. I. Serum steroids and gonadotropins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:623-626.

- Goodwin JP, Miller A, Del Giudice ME, et al. Elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and dietary fat intake in women with cyclic mastopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:430-437.

- Goyal A, Mansel RE. Efamast Study Group. A randomized multicenter study of gamolenic acid (Efamast) with and without antioxidant vitamins and minerals in the management of mastalgia. Breast J. 2005;11(1):41-47.

- Parsay S, Olfati F, Nahidi S. Therapeutic effects of vitamin E on cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2009;15:510-514.

- Allen SS, Froberg DG. The effect of decreased caffeine consumption on benign proliferative breast disease: a randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1987;101:720-730.

- Hadi MS. Sports brassiere: is it a solution for mastalgia? Breast J. 2000;6:407-409.

- Russell LC. Caffeine restriction as initial treatment for breast pain. Nurse Pract. 1989; 14(2): 36-7.

- Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

- Irving AD, Morrison SL. Effectiveness of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of breast pain. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:158-159.

- Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficiency of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(4):525-530.

- Kaviani A, Mehrdad N, Najafi M, et al. Comparison of naproxen with placebo for the management of noncyclical breast pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. World J Surg. 2008;32:2464-2470.

- Fentiman IS, Caleffi M, Brame K, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of tamoxifen therapy for mastalgia. Lancet. 1986;1:287-288.

- Jain BK, Bansal A, Choudhary D, et al. Centchroman vs tamoxifen for regression of mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Intl J Surg. 2015;15:11-16.

- Mansel R, Goyal A, Le Nestour EL, et al; Afimoxifene (4-OHT) Breast Pain Research group. A phase II trial of Afimoxifene (4-hydroxyamoxifen gel) for cyclical mastalgia in premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:389-397.

- O'Brien PM, Abukhalil IE. Randomized controlled trial of the management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase-only danazol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:18-23.

- Blichert-Toft M, Andersen AN, Henriksen OB, et al. Treatment of mastalgia with bromocriptine: a double-blind cross-over study. Br Med J. 1979;1:237.

Breast pain is one of the most common breast-related patient complaints and is found to affect at least 50% of the female population.1 Most cases are self-limiting and are related to hormonal and normal fibrocystic changes. The median age of onset of symptoms is 36 years, with most women experiencing pain for 5 to 12 years.2 Because the cause of breast pain is not always clear, its presence can produce anxiety in patients and physicians over the possibility of underlying malignancy. Although breast cancer is not associated with breast pain, many patients presenting with pain are referred for diagnostic imaging (usually with negative results). The majority of women with mastalgia and normal clinical examination findings can be reassured with education about the many benign causes of breast pain.

What are causes of breast pain without an imaging abnormality?

Hormones. Mastalgia can be focal or generalized and is mostly due to hormonal changes. Elevated estrogen can stimulate the growth of breast tissue, which is known as epithelial hyperplasia.3 Fluctuations in hormone levels can occur in perimenopausal women in their forties and can result in new symptoms of breast pain.4 Sometimes starting a new contraceptive medication or hormone replacement therapy can exacerbate the pain. Switching brands or medications may help. Another cause of mastalgia may be elevated prolactin levels, with hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction.5,6

Diet. There is evidence to link a high-fat diet with breast pain. The pain has been shown to improve when lipid intake is reduced and high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are normalized. As estrogen is a steroid hormone that can be synthesized from lipids and fatty acids, elevated lipid metabolism can increase estrogen levels and exacerbate breast pain symptoms.7,8 Essential fatty acids, such as evening primrose oil and vitamin E, have been used to treat mastalgia because they reduce inflammation in fatty breast tissue through the prostaglandin pathway.9,10

Caffeine. Methylxanthines can be found in coffee, tea, and chocolate and can aggravate mastalgia by enhancing the cyclin adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway. This pathway stimulates cellular proliferation and fibrocystic changes which in turn can exacerbate breast pain.11

Smoking. In my clinical practice I have clearly noted a higher incidence of breast pain in patients who smoke. The pain tends to improve significantly when the patient quits or even cuts back on smoking. The exact reasons for smoking’s effects on breast pain are not well known; however, they are thought to be related to acceleration of the cAMP pathway.

Large breast size. Very large breasts will strain and weaken the suspensory ligaments, leading to pain and discomfort. It has been shown that wearing a supportive sports bra during episodes of breast pain is effective.

Types of breast pain

Cyclical

Women with fibrocystic breasts tend to experience more breast pain. Breast sensitivity can be localized to the upper outer quadrants or to the nipple and sub-areolar area. It also can be generalized. The pain tends to peak with ovulation, improve with menses, and to recur every few weeks. Patients who have had partial hysterectomy (with ovaries in situ) or endometrial ablation will be unable to correlate their symptoms to menstruation. Therefore, women are encouraged to keep a diary or calendar of their symptoms to detect any correlation with their ovarian cycle. Such correlation is reassuring.

Continue to: Noncyclical...

Noncyclical

Noncyclical breast pain is not associated with the menstrual cycle and can be unilateral or bilateral. Providers should perform a good history of patients presenting with noncyclicalbreast pain, to include character, onset, duration, location, radiation, alleviating, and aggravating factors. A physical examination may elicit point tenderness at the chest by pushing the breast tissue off of the chest wall while the patient is in supine position and pressing directly over the ribs. Lack of tenderness on palpation of the breast parenchyma, but pain on the chest wall, points to a musculoskeletal etiology. Chest wall pain may be related to muscle spasm or muscle strain, trauma, rib fracture, or costochondritis (Tietze syndrome). Finally, based on history of review of systems and physical examination, referred pain from biliary or cardiac etiology should be considered.

When breast pain occurs with skin changes

Skin changes usually have an underlying pathology. Infectious processes, such as infected epidermal inclusion cyst, hidradenitis of the cleavage and inframammary crease, or breast abscess will present with pain and induration with an acute onset of 5 to 10 days. Large pendulous breasts may develop yeast infection at the inframammary crease. Chronic infectious irritation can lead to hyperpigmentation of that area. Eczema or contact dermatitis frequently can affect the areola and become confused with Paget disease (ductal carcinoma in situ of the nipple). With Paget, the excoriation always starts at the nipple and can then spread to the areola. However, with dermatitis, the rash begins on the peri-areolar skin, without affecting the nipple itself.

When breast pain occurs with nipple discharge

Breast pain with nipple discharge usually is bilateral and more common in patients with significant fibrocystic changes who smoke. If the nipple discharge is bilateral, serous and non-bloody, and multiduct, it is considered benign and physiologic. Physiologic nipple discharge can be multifactorial and hormonal. It may be related to thyroid disorders or medications such as antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, or antipsychotics. The only nipple discharge that is considered pathologic is unilateral spontaneous bloody discharge for which diagnostic imaging and breast surgeon referral is indicated. Women should be discouraged from self-expressing their nipples, as 80% will experience serous nipple discharge upon manual self-expression.

Breast pain is not associated with breast cancer. Most breast cancers do not hurt; they present as firm, painless masses. However, when a woman notices pain in her breast, her first concern is breast cancer. This concern is re-enforced by the medical provider whose first impulse is to order diagnostic imaging. Yet less than 3% of breast cancers are associated with breast pain.

There have been multiple published retrospective and prospective radiologic studies about the utility of breast imaging in women with breast pain without a palpable mass. All of the studies have demonstrated that breast imaging with mammography and ultrasonography in these patients yields mostly negative or benign findings. The incidence of breast cancer during imaging work-up in women with breast pain and no clinical abnormality is only 0.4% to 1.8%.1-3 Some patients may develop future subsequent breast cancer in the symptomatic breast. But this is considered incidental and possibly related to increased cell turnover related to fibrocystic changes. Breast imaging for evaluation of breast pain only provides reassurance to the physician. The patient's reassurance will come from a medical explanation for the symptoms and advice on symptom management from the provider.

Researchers from MD Anderson Cancer Center reported imaging findings and cost analysis for 799 patients presenting with breast pain from 3 large network community-based breast imaging centers in 2014. Breast ultrasound was the initial imaging modality for women younger than age 30. Digital mammography (sometimes with tomosynthesis) was used for those older than age 30 that had not had a mammogram in the last 6 months. Breast magnetic resonance imaging was performed only when ordered by the referring physician. Most of the patients presented for diagnostic imaging, and 95% had negative findings and 5% had a benign finding. Only 1 patient was found to have an incidental cancer in the contralateral breast, which was detected by tomosynthesis. The cost of breast imaging was $87,322 in younger women and $152,732 in women older than age 40, representing overutilization of health care resources and no association between breast pain and breast cancer.4

References

- Chetlan AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

- Arslan M, Kücükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

- Noroozian M, Stein LF, Gaetke-Udager K, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in women with breast pain in the absence of additional clinical findings: Mammography remains indicated. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:417-424.

- Kushwaha AC, Shin K, Kalambo M, et al. Overutilization of health care resources for breast pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018; 211:217-223.

Management of mastalgia

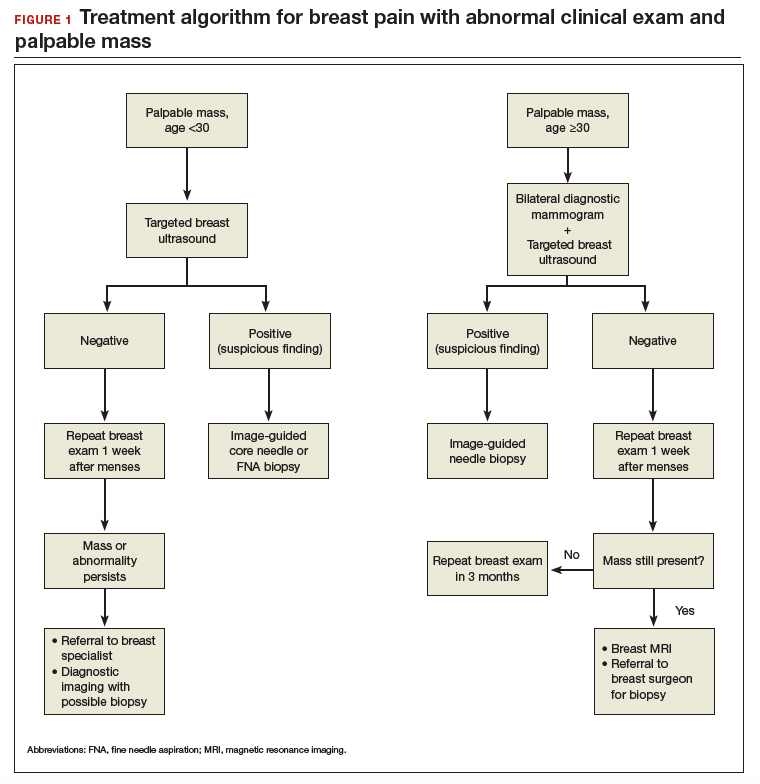

Appropriate breast pain management begins with a good history and physical examination. The decision to perform imaging should depend on clinical exam findings and not on symptoms of breast pain. If there is a palpable mass, then breast imaging and possible biopsy is appropriate. However, if clinical exam is normal, there is no indication for breast imaging in low-risk women under the age of 40 whose only symptom is breast pain. Women older than age 40 can undergo diagnostic imaging, if they have not had a negative screening mammogram in the past year.

Breast pain with abnormal clinical exam

In the patient who is younger than age 30 with a palpable mass. For this patient order targeted breast ultrasound (US) (FIGURE 1). If results are negative, repeat the clinical examination 1 week after menses. If the mass is persistent, refer the patient to a breast surgeon. If diagnostic imaging results are negative, consider breast MRI, especially if there is a strong family history of breast cancer.

In the patient who is aged 30 and older with a palpable mass. For this patient, bilateral diagnostic mammogram and US are in order. The testing is best performed 1 week after menses to reduce false-positive findings. If imaging is negative and the patient still has a clinically suspicious finding or mass, refer her to a breast surgeon and consider breast MRI. At this point if there is a persistent firm dominant mass, a biopsy is indicated as part of the triple test. If the mass resolves with menses, the patient can be reassured that the cause is most likely benign, with clinical examination repeated in 3 months.

Continue to: Breast pain and normal clinical exam...

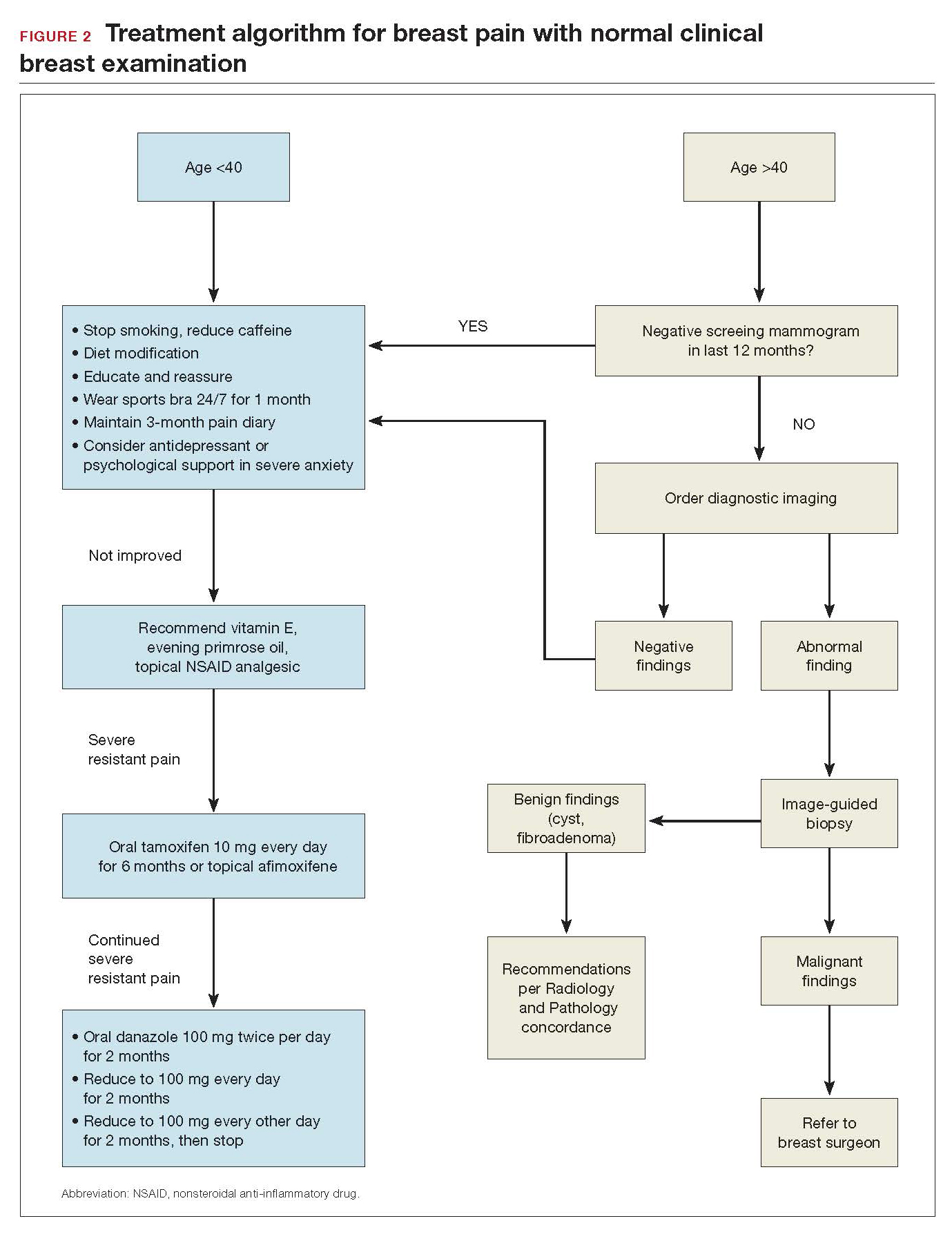

Breast pain and normal clinical exam

When women who report breast pain have normal clinical examination findings (and have a negative screening mammogram in the past 12 months if older than age 40), there are several management strategies you can offer (FIGURE 2).

Reassurance and education. The majority of women with breast pain can be managed with reassurance and education, which are often sufficient to reduce their anxieties.

Supportive bra. The most effective intervention is to wear and sleep in a well-fitted supportive sports bra for 4 to 12 weeks. In a nonrandomized single-center trial of danazol versus sports bra, 85% of women reported relief of their breast pain with bra alone (vs 58% with danazol).12 A supportive bra is the first-line management of mastalgia (Level II evidence).

Symptom diary/calendar. Many women do not know whether or not their symptoms correspond to their ovarian cycle or are related to hormonal fluctuations. Therefore, it is reassuring and informative for them to keep a calendar or a diary of their symptoms to determine whether their symptoms occur or are exacerbated in a cyclical pattern.

Diet and lifestyle modification. Women should avoid caffeine (especially when having pain). Studies on methylxanthines have demonstrated some symptom relief with reducing caffeine intake.11,13 One cup of coffee or tea per day most likely will not make a difference. However, if a woman is drinking large quantities of caffeinated beverages throughout the day, it will very likely improve her breast pain if she cuts back. This is especially true during the times of exacerbated pain prior to her menses.

In addition, recommend reduced dietary fat (overall good health). This is good advice for any patient. There were 2 small studies that showed improvement in breast pain with a 15% reduction in dietary fat.7,8

Finally, advise that patients stop smoking. Smoking aggravates and exacerbates fibrocystic changes, and these will lead to more breast pain.

Medical management. Over-the-counter medications that are found in the vitamin section of a local drug store are vitamin E and evening primrose oil. There are no significant adverse effects with these treatments. Their efficacy is theoretical, however; 3 randomized controlled trials demonstrated no significant clinical benefit with evening primrose oil versus placebo for treatment of mastalgia.14

Topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; Voltaren gel, topical compound pain creams) are useful as second-line management after using a supportive bra. Three randomized controlled trials have demonstrated up to 90% improvement of mastalgia with topical NSAIDs.15-17

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM), which is an antagonist to the estrogen receptor (ER) in the breast and an agonist to the ER in the endometrium. Tamoxifen has been found to reduce symptoms of mastalgia by 70% even at a lower dosage of 10-mg per day (for 6 months), or as a topical gel (afimoxifene). The oral form can have some adverse effects, including hot flashes, and has a low risk for thromboembolic events and endometrial neoplasia.18-20

Danazol is very effective in reducing breast pain symptoms (by 80%), with a higher relapse after stopping the medication. Danazol is less tolerated due to its androgenic effects, such as hirsutism, acne, menorrhagia, and voice changes. Both danazol and tamoxifen can be teratogenic and should be used with caution in women of child-bearing age.21

Finally, bromocriptine inhibits serum prolactin and has been reported to provide 65% improvement in breast pain. Its use for breast pain is not US Food and Drug Administration–approved and adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, and hypotension.22

Tamoxifen, danazol, and bromocriptine can be considered as third-line management options for severe treatment-resistant mastalgia.

Continue to: FIGURE 2 Treatment algorithm for breast pain...

In summary

Evaluation and counseling for breast pain should be managed by women’s health care providers in a primary care setting. Most patients need reassurance and medical explanation of their symptoms. They should be educated that more than 95% of the time breast pain is not caused by an underlying malignancy but rather due to hormonal and fibrocystic changes, which can be managed conservatively. If the clinical breast examination and recent screening mammogram (in women over age 40) results are negative, patients should be educated that their pain is benign and undergo a trial of conservative measures: wear and sleep in a supporting bra; keep a calendar of symptoms to determine any relation to cyclical changes; and avoid nicotine, caffeine, and fatty food. Topical pain creams with diclofenac and evening primrose oil also can be effective in ameliorating the symptoms. Breast pain is not a surgical disease; referral to a surgical specialist and diagnostic imaging can be unnecessary and expensive.

Breast pain is one of the most common breast-related patient complaints and is found to affect at least 50% of the female population.1 Most cases are self-limiting and are related to hormonal and normal fibrocystic changes. The median age of onset of symptoms is 36 years, with most women experiencing pain for 5 to 12 years.2 Because the cause of breast pain is not always clear, its presence can produce anxiety in patients and physicians over the possibility of underlying malignancy. Although breast cancer is not associated with breast pain, many patients presenting with pain are referred for diagnostic imaging (usually with negative results). The majority of women with mastalgia and normal clinical examination findings can be reassured with education about the many benign causes of breast pain.

What are causes of breast pain without an imaging abnormality?

Hormones. Mastalgia can be focal or generalized and is mostly due to hormonal changes. Elevated estrogen can stimulate the growth of breast tissue, which is known as epithelial hyperplasia.3 Fluctuations in hormone levels can occur in perimenopausal women in their forties and can result in new symptoms of breast pain.4 Sometimes starting a new contraceptive medication or hormone replacement therapy can exacerbate the pain. Switching brands or medications may help. Another cause of mastalgia may be elevated prolactin levels, with hypothalamic-pituitary dysfunction.5,6

Diet. There is evidence to link a high-fat diet with breast pain. The pain has been shown to improve when lipid intake is reduced and high- and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels are normalized. As estrogen is a steroid hormone that can be synthesized from lipids and fatty acids, elevated lipid metabolism can increase estrogen levels and exacerbate breast pain symptoms.7,8 Essential fatty acids, such as evening primrose oil and vitamin E, have been used to treat mastalgia because they reduce inflammation in fatty breast tissue through the prostaglandin pathway.9,10

Caffeine. Methylxanthines can be found in coffee, tea, and chocolate and can aggravate mastalgia by enhancing the cyclin adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) pathway. This pathway stimulates cellular proliferation and fibrocystic changes which in turn can exacerbate breast pain.11

Smoking. In my clinical practice I have clearly noted a higher incidence of breast pain in patients who smoke. The pain tends to improve significantly when the patient quits or even cuts back on smoking. The exact reasons for smoking’s effects on breast pain are not well known; however, they are thought to be related to acceleration of the cAMP pathway.

Large breast size. Very large breasts will strain and weaken the suspensory ligaments, leading to pain and discomfort. It has been shown that wearing a supportive sports bra during episodes of breast pain is effective.

Types of breast pain

Cyclical

Women with fibrocystic breasts tend to experience more breast pain. Breast sensitivity can be localized to the upper outer quadrants or to the nipple and sub-areolar area. It also can be generalized. The pain tends to peak with ovulation, improve with menses, and to recur every few weeks. Patients who have had partial hysterectomy (with ovaries in situ) or endometrial ablation will be unable to correlate their symptoms to menstruation. Therefore, women are encouraged to keep a diary or calendar of their symptoms to detect any correlation with their ovarian cycle. Such correlation is reassuring.

Continue to: Noncyclical...

Noncyclical

Noncyclical breast pain is not associated with the menstrual cycle and can be unilateral or bilateral. Providers should perform a good history of patients presenting with noncyclicalbreast pain, to include character, onset, duration, location, radiation, alleviating, and aggravating factors. A physical examination may elicit point tenderness at the chest by pushing the breast tissue off of the chest wall while the patient is in supine position and pressing directly over the ribs. Lack of tenderness on palpation of the breast parenchyma, but pain on the chest wall, points to a musculoskeletal etiology. Chest wall pain may be related to muscle spasm or muscle strain, trauma, rib fracture, or costochondritis (Tietze syndrome). Finally, based on history of review of systems and physical examination, referred pain from biliary or cardiac etiology should be considered.

When breast pain occurs with skin changes

Skin changes usually have an underlying pathology. Infectious processes, such as infected epidermal inclusion cyst, hidradenitis of the cleavage and inframammary crease, or breast abscess will present with pain and induration with an acute onset of 5 to 10 days. Large pendulous breasts may develop yeast infection at the inframammary crease. Chronic infectious irritation can lead to hyperpigmentation of that area. Eczema or contact dermatitis frequently can affect the areola and become confused with Paget disease (ductal carcinoma in situ of the nipple). With Paget, the excoriation always starts at the nipple and can then spread to the areola. However, with dermatitis, the rash begins on the peri-areolar skin, without affecting the nipple itself.

When breast pain occurs with nipple discharge

Breast pain with nipple discharge usually is bilateral and more common in patients with significant fibrocystic changes who smoke. If the nipple discharge is bilateral, serous and non-bloody, and multiduct, it is considered benign and physiologic. Physiologic nipple discharge can be multifactorial and hormonal. It may be related to thyroid disorders or medications such as antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), mood stabilizers, or antipsychotics. The only nipple discharge that is considered pathologic is unilateral spontaneous bloody discharge for which diagnostic imaging and breast surgeon referral is indicated. Women should be discouraged from self-expressing their nipples, as 80% will experience serous nipple discharge upon manual self-expression.

Breast pain is not associated with breast cancer. Most breast cancers do not hurt; they present as firm, painless masses. However, when a woman notices pain in her breast, her first concern is breast cancer. This concern is re-enforced by the medical provider whose first impulse is to order diagnostic imaging. Yet less than 3% of breast cancers are associated with breast pain.

There have been multiple published retrospective and prospective radiologic studies about the utility of breast imaging in women with breast pain without a palpable mass. All of the studies have demonstrated that breast imaging with mammography and ultrasonography in these patients yields mostly negative or benign findings. The incidence of breast cancer during imaging work-up in women with breast pain and no clinical abnormality is only 0.4% to 1.8%.1-3 Some patients may develop future subsequent breast cancer in the symptomatic breast. But this is considered incidental and possibly related to increased cell turnover related to fibrocystic changes. Breast imaging for evaluation of breast pain only provides reassurance to the physician. The patient's reassurance will come from a medical explanation for the symptoms and advice on symptom management from the provider.

Researchers from MD Anderson Cancer Center reported imaging findings and cost analysis for 799 patients presenting with breast pain from 3 large network community-based breast imaging centers in 2014. Breast ultrasound was the initial imaging modality for women younger than age 30. Digital mammography (sometimes with tomosynthesis) was used for those older than age 30 that had not had a mammogram in the last 6 months. Breast magnetic resonance imaging was performed only when ordered by the referring physician. Most of the patients presented for diagnostic imaging, and 95% had negative findings and 5% had a benign finding. Only 1 patient was found to have an incidental cancer in the contralateral breast, which was detected by tomosynthesis. The cost of breast imaging was $87,322 in younger women and $152,732 in women older than age 40, representing overutilization of health care resources and no association between breast pain and breast cancer.4

References

- Chetlan AL, Kapoor MM, Watts MR. Mastalgia: imaging work-up appropriateness. Acad Radiol. 2017;24:345-349.

- Arslan M, Kücükerdem HS, Can H, et al. Retrospective analysis of women with only mastalgia. J Breast Health. 2016;12:151-154.

- Noroozian M, Stein LF, Gaetke-Udager K, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes in women with breast pain in the absence of additional clinical findings: Mammography remains indicated. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;149:417-424.

- Kushwaha AC, Shin K, Kalambo M, et al. Overutilization of health care resources for breast pain. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2018; 211:217-223.

Management of mastalgia

Appropriate breast pain management begins with a good history and physical examination. The decision to perform imaging should depend on clinical exam findings and not on symptoms of breast pain. If there is a palpable mass, then breast imaging and possible biopsy is appropriate. However, if clinical exam is normal, there is no indication for breast imaging in low-risk women under the age of 40 whose only symptom is breast pain. Women older than age 40 can undergo diagnostic imaging, if they have not had a negative screening mammogram in the past year.

Breast pain with abnormal clinical exam

In the patient who is younger than age 30 with a palpable mass. For this patient order targeted breast ultrasound (US) (FIGURE 1). If results are negative, repeat the clinical examination 1 week after menses. If the mass is persistent, refer the patient to a breast surgeon. If diagnostic imaging results are negative, consider breast MRI, especially if there is a strong family history of breast cancer.

In the patient who is aged 30 and older with a palpable mass. For this patient, bilateral diagnostic mammogram and US are in order. The testing is best performed 1 week after menses to reduce false-positive findings. If imaging is negative and the patient still has a clinically suspicious finding or mass, refer her to a breast surgeon and consider breast MRI. At this point if there is a persistent firm dominant mass, a biopsy is indicated as part of the triple test. If the mass resolves with menses, the patient can be reassured that the cause is most likely benign, with clinical examination repeated in 3 months.

Continue to: Breast pain and normal clinical exam...

Breast pain and normal clinical exam

When women who report breast pain have normal clinical examination findings (and have a negative screening mammogram in the past 12 months if older than age 40), there are several management strategies you can offer (FIGURE 2).

Reassurance and education. The majority of women with breast pain can be managed with reassurance and education, which are often sufficient to reduce their anxieties.

Supportive bra. The most effective intervention is to wear and sleep in a well-fitted supportive sports bra for 4 to 12 weeks. In a nonrandomized single-center trial of danazol versus sports bra, 85% of women reported relief of their breast pain with bra alone (vs 58% with danazol).12 A supportive bra is the first-line management of mastalgia (Level II evidence).

Symptom diary/calendar. Many women do not know whether or not their symptoms correspond to their ovarian cycle or are related to hormonal fluctuations. Therefore, it is reassuring and informative for them to keep a calendar or a diary of their symptoms to determine whether their symptoms occur or are exacerbated in a cyclical pattern.

Diet and lifestyle modification. Women should avoid caffeine (especially when having pain). Studies on methylxanthines have demonstrated some symptom relief with reducing caffeine intake.11,13 One cup of coffee or tea per day most likely will not make a difference. However, if a woman is drinking large quantities of caffeinated beverages throughout the day, it will very likely improve her breast pain if she cuts back. This is especially true during the times of exacerbated pain prior to her menses.

In addition, recommend reduced dietary fat (overall good health). This is good advice for any patient. There were 2 small studies that showed improvement in breast pain with a 15% reduction in dietary fat.7,8

Finally, advise that patients stop smoking. Smoking aggravates and exacerbates fibrocystic changes, and these will lead to more breast pain.

Medical management. Over-the-counter medications that are found in the vitamin section of a local drug store are vitamin E and evening primrose oil. There are no significant adverse effects with these treatments. Their efficacy is theoretical, however; 3 randomized controlled trials demonstrated no significant clinical benefit with evening primrose oil versus placebo for treatment of mastalgia.14

Topical or oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs; Voltaren gel, topical compound pain creams) are useful as second-line management after using a supportive bra. Three randomized controlled trials have demonstrated up to 90% improvement of mastalgia with topical NSAIDs.15-17

Tamoxifen is a selective estrogen-receptor modulator (SERM), which is an antagonist to the estrogen receptor (ER) in the breast and an agonist to the ER in the endometrium. Tamoxifen has been found to reduce symptoms of mastalgia by 70% even at a lower dosage of 10-mg per day (for 6 months), or as a topical gel (afimoxifene). The oral form can have some adverse effects, including hot flashes, and has a low risk for thromboembolic events and endometrial neoplasia.18-20

Danazol is very effective in reducing breast pain symptoms (by 80%), with a higher relapse after stopping the medication. Danazol is less tolerated due to its androgenic effects, such as hirsutism, acne, menorrhagia, and voice changes. Both danazol and tamoxifen can be teratogenic and should be used with caution in women of child-bearing age.21

Finally, bromocriptine inhibits serum prolactin and has been reported to provide 65% improvement in breast pain. Its use for breast pain is not US Food and Drug Administration–approved and adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, and hypotension.22

Tamoxifen, danazol, and bromocriptine can be considered as third-line management options for severe treatment-resistant mastalgia.

Continue to: FIGURE 2 Treatment algorithm for breast pain...

In summary

Evaluation and counseling for breast pain should be managed by women’s health care providers in a primary care setting. Most patients need reassurance and medical explanation of their symptoms. They should be educated that more than 95% of the time breast pain is not caused by an underlying malignancy but rather due to hormonal and fibrocystic changes, which can be managed conservatively. If the clinical breast examination and recent screening mammogram (in women over age 40) results are negative, patients should be educated that their pain is benign and undergo a trial of conservative measures: wear and sleep in a supporting bra; keep a calendar of symptoms to determine any relation to cyclical changes; and avoid nicotine, caffeine, and fatty food. Topical pain creams with diclofenac and evening primrose oil also can be effective in ameliorating the symptoms. Breast pain is not a surgical disease; referral to a surgical specialist and diagnostic imaging can be unnecessary and expensive.

- Scurr J, Hedger W, Morris P, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of breast pain in the general population. Breast J. 2014;20:508-513.

- Davies EL, Gateley CA, Miers M, et al. The long-term course of mastalgia. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:462-464.

- Singletary SE, Robb GL, Hortobagy GN. Advanced Therapy of Breast Disease. 2nd ed. Ontario, Canada: BC Decker Inc.; 2004.

- Gong C, Song E, Jia W, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of toremifen therapy for mastaglia. Arch Surg. 2006;141:43-47.

- Kumar S, Mansel RE, Scanlon MF, et al. Altered responses of prolactin, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone secretion to thyrotrophin releasing hormone/gonadotrophin releasing hormone stimulation in cyclical mastalgia. Br J Surg. 1984;71:870-873.

- Mansel RE, Dogliotti L. European multicentre trial of bromocriptine in cyclical mastalgia. Lancet. 1990;335:190-193.

- Rose DP, Boyar AP, Cohen C, et al. Effect of a low-fat diet on hormone levels in women with cystic breast disease. I. Serum steroids and gonadotropins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:623-626.

- Goodwin JP, Miller A, Del Giudice ME, et al. Elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and dietary fat intake in women with cyclic mastopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:430-437.

- Goyal A, Mansel RE. Efamast Study Group. A randomized multicenter study of gamolenic acid (Efamast) with and without antioxidant vitamins and minerals in the management of mastalgia. Breast J. 2005;11(1):41-47.

- Parsay S, Olfati F, Nahidi S. Therapeutic effects of vitamin E on cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2009;15:510-514.

- Allen SS, Froberg DG. The effect of decreased caffeine consumption on benign proliferative breast disease: a randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1987;101:720-730.

- Hadi MS. Sports brassiere: is it a solution for mastalgia? Breast J. 2000;6:407-409.

- Russell LC. Caffeine restriction as initial treatment for breast pain. Nurse Pract. 1989; 14(2): 36-7.

- Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

- Irving AD, Morrison SL. Effectiveness of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of breast pain. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:158-159.

- Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficiency of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(4):525-530.

- Kaviani A, Mehrdad N, Najafi M, et al. Comparison of naproxen with placebo for the management of noncyclical breast pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. World J Surg. 2008;32:2464-2470.

- Fentiman IS, Caleffi M, Brame K, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of tamoxifen therapy for mastalgia. Lancet. 1986;1:287-288.

- Jain BK, Bansal A, Choudhary D, et al. Centchroman vs tamoxifen for regression of mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Intl J Surg. 2015;15:11-16.

- Mansel R, Goyal A, Le Nestour EL, et al; Afimoxifene (4-OHT) Breast Pain Research group. A phase II trial of Afimoxifene (4-hydroxyamoxifen gel) for cyclical mastalgia in premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:389-397.

- O'Brien PM, Abukhalil IE. Randomized controlled trial of the management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase-only danazol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:18-23.

- Blichert-Toft M, Andersen AN, Henriksen OB, et al. Treatment of mastalgia with bromocriptine: a double-blind cross-over study. Br Med J. 1979;1:237.

- Scurr J, Hedger W, Morris P, et al. The prevalence, severity, and impact of breast pain in the general population. Breast J. 2014;20:508-513.

- Davies EL, Gateley CA, Miers M, et al. The long-term course of mastalgia. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:462-464.

- Singletary SE, Robb GL, Hortobagy GN. Advanced Therapy of Breast Disease. 2nd ed. Ontario, Canada: BC Decker Inc.; 2004.

- Gong C, Song E, Jia W, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of toremifen therapy for mastaglia. Arch Surg. 2006;141:43-47.

- Kumar S, Mansel RE, Scanlon MF, et al. Altered responses of prolactin, luteinizing hormone and follicle stimulating hormone secretion to thyrotrophin releasing hormone/gonadotrophin releasing hormone stimulation in cyclical mastalgia. Br J Surg. 1984;71:870-873.

- Mansel RE, Dogliotti L. European multicentre trial of bromocriptine in cyclical mastalgia. Lancet. 1990;335:190-193.

- Rose DP, Boyar AP, Cohen C, et al. Effect of a low-fat diet on hormone levels in women with cystic breast disease. I. Serum steroids and gonadotropins. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;78:623-626.

- Goodwin JP, Miller A, Del Giudice ME, et al. Elevated high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and dietary fat intake in women with cyclic mastopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:430-437.

- Goyal A, Mansel RE. Efamast Study Group. A randomized multicenter study of gamolenic acid (Efamast) with and without antioxidant vitamins and minerals in the management of mastalgia. Breast J. 2005;11(1):41-47.

- Parsay S, Olfati F, Nahidi S. Therapeutic effects of vitamin E on cyclic mastalgia. Breast J. 2009;15:510-514.

- Allen SS, Froberg DG. The effect of decreased caffeine consumption on benign proliferative breast disease: a randomized clinical trial. Surgery. 1987;101:720-730.

- Hadi MS. Sports brassiere: is it a solution for mastalgia? Breast J. 2000;6:407-409.

- Russell LC. Caffeine restriction as initial treatment for breast pain. Nurse Pract. 1989; 14(2): 36-7.

- Srivastava A, Mansel RE, Arvind N, et al. Evidence-based management of mastalgia: a meta-analysis of randomised trials. Breast. 2007;16:503-512.

- Irving AD, Morrison SL. Effectiveness of topical non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the management of breast pain. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1998;43:158-159.

- Colak T, Ipek T, Kanik A, et al. Efficiency of topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in mastalgia treatment. J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196(4):525-530.

- Kaviani A, Mehrdad N, Najafi M, et al. Comparison of naproxen with placebo for the management of noncyclical breast pain: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. World J Surg. 2008;32:2464-2470.

- Fentiman IS, Caleffi M, Brame K, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of tamoxifen therapy for mastalgia. Lancet. 1986;1:287-288.

- Jain BK, Bansal A, Choudhary D, et al. Centchroman vs tamoxifen for regression of mastalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Intl J Surg. 2015;15:11-16.

- Mansel R, Goyal A, Le Nestour EL, et al; Afimoxifene (4-OHT) Breast Pain Research group. A phase II trial of Afimoxifene (4-hydroxyamoxifen gel) for cyclical mastalgia in premenopausal women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:389-397.

- O'Brien PM, Abukhalil IE. Randomized controlled trial of the management of premenstrual syndrome and premenstrual mastalgia using luteal phase-only danazol. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:18-23.

- Blichert-Toft M, Andersen AN, Henriksen OB, et al. Treatment of mastalgia with bromocriptine: a double-blind cross-over study. Br Med J. 1979;1:237.

Modern breast surgery: What you should know

In a striking trend, the rate of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy (CPM) has risen by 30% over the last 10 years in the United States.1 Many women undergo CPM because of the fear and anxiety of cancer recurrence and their perceived risk of contralateral breast cancer; however, few women have a medical condition that necessitates removal of the contralateral breast. The medical indications for CPM include having a pathogenic genetic mutation (eg, BRCA1 and BRCA2), a strong family history of breast cancer, or prior mediastina chest radiation.

The actual risk of contralateral breast cancer is much lower than perceived. In women without a genetic mutation, the 10-year risk of contralateral breast cancer is only 3% to 5%.1 Also, CPM does not prevent the development of metastatic disease and offers no survival benefit over breast conservation or unilateral mastectomy.2 Furthermore, compared with unilateral therapeutic mastectomy, the “upgrade” to a CPM carries a 2.7-fold risk of a major surgical complication.3 It is therefore important that patients receive appropriate counseling regarding CPM, and that this counseling include cancer stage at diagnosis, family history and genetic risk, and cancer versus surgical risk (see “Counseling patients on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy” for key points to cover in patient discussions).

Counseling patients on contralateral prophylactic mastectomy

Commonly, patients diagnosed with breast cancer consider having their contralateral healthy breast removed as part of a bilateral mastectomy. They often experience severe anxiety about the cancer coming back and believe that removing both breasts will enable them to live longer. Keep the following key facts in mind when discussing treatment options with breast cancer patients.

Cancer stage at diagnosis. How long a patient lives from the time of her breast cancer diagnosis depends on the stage of the cancer at diagnosis, not the type of surgery performed. A woman with early stage I or stage II breast cancer has an 80% to 90% chance of being cancer free in 5 years.1 The chance of cancer recurring in the bones, liver, or lungs (metastatic breast cancer) will not be changed by removing the healthy breast. The risk of metastatic recurrence can be reduced, however, with chemotherapy and/or with hormone-blocker therapy.

Family history and genetic risk. Few women have a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian and other cancers, and this issue should be addressed with genetic counseling and testing prior to surgery. Those who carry a cancer-causing gene, such as BRCA1 or BRCA2, are at increased risk (40% to 60%) for a second or third breast cancer, especially if they are diagnosed at a young age (<50 years).2,3 In women who have a genetic mutation, removing both breasts and sometimes the ovaries can prevent development of another breast cancer. But this will not prevent spread of the cancer that is already present. Only chemotherapy and hormone blockers can prevent the spread of cancer.

Cancer risk versus surgical risk. For women with no family history of breast cancer, no genetic mutation, and no prior chest wall radiation, the risk of developing a new breast cancer in their other breast is only 3% to 5% every 10 years.3,4 This means that they have a 95% chance of not developing a new breast cancer in their healthy breast. Notably, removing the healthy breast can double the risk of postsurgical complications, including bleeding, infection, and loss of tissue and implant. The mastectomy site will be numb and the skin and nipple areola will not have any function other than cosmetic. Finally, wound complications from surgery could delay the start of important cancer treatment, such as chemotherapy or radiation.

The bottom line. Unless a woman has a strong family history of breast cancer, is diagnosed at a very young age, or has a genetic cancer-causing mutation, removing the contralateral healthy breast is not medically necessary and is not routinely recommended.

References

- Hennigs A, Riedel F, Gondos A, et al. Prognosis of breast cancer molecular subtypes in routine clinical care: a large prospective cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2016;16(1):734.

- Graeser MK, Engel C, Rhiem K, et al. Contralateral breast cancer risk in BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(35):5887–5992.

- Curtis RE, Ron E, Hankey BF, Hoover RN. New malignancies following breast cancer. In: Curtis RE, Freedman DM, Ron E, et al, eds. New Malignancies Among Cancer Survivors: SEER Cancer Registries, 1973-2000. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. NIH Publ. No. 05-5302. 2006:181–205. http://seer.cancer.gov/archive/publications/mpmono. Accessed September 18, 2016.

- Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1564–1569.

Women should be made aware that there are alternatives to mastectomy that have similar, or even better, outcomes with improved quality of life. Furthermore, a multi‑disciplinary, team-oriented approach with emphasis on minimally invasive biopsy and better cosmetic outcomes has enhanced quality of care. Knowledge of this team approach and of modern breast cancer treatments is essential for general ObGyns as this understanding improves the overall care and guidance—specifically regarding referral to expert, high-volume breast surgeons—provided to those women most in need.

Expanded treatment options for breast cancer

Advancements in breast surgery, better imaging, and targeted therapies are changing the paradigm of breast cancer treatment.

Image-guided biopsy is key in decision making

When an abnormality is found in the breast, surgical excision of an undiagnosed breast lesion is no longer considered an appropriate first step. Use of image-guided biopsy or minimally invasive core needle biopsy allows for accurate diagnosis of a breast lesion while avoiding a potentially breast deforming and expensive surgical operation. It is always better to go into the operating room (OR) with a diagnosis and do the right operation the first time.

A core needle biopsy, results of which demonstrate a benign lesion, helps avoid breast surgery in women who do not need it. If cancer is diagnosed on biopsy, the extent of disease can be better evaluated and decision making can be more informed, with a multidisciplinary approach used to consider the various options, including genetic counseling, plastic surgery consultation, or neoadjuvant therapy. Some lesions, such as those too close to the skin, chest wall, or an implant, may not be amenable to core needle biopsy and therefore require surgical excision for diagnosis.

Benefits of a multidisciplinary tumor conference

It is important for a multidisciplinary group of cancer specialists to review a patient’s case and discuss the ideal treatment plan prior to surgery. Some breast cancer subtypes (such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 [HER2]–overamplified breast cancer and many triple-negative breast cancers) are very sensitive to chemotherapy, and patients with these tumor types may benefit from receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy prior to surgery. New types of chemotherapy may allow up to 60% of some breast cancers to diminish almost completely, with subsequent improved cosmetic results of breast surgery.4 It may also allow time for genetic counseling and testing prior to surgery. (See “How to code for a multidisciplinary tumor conference” for appropriate coding procedure.)

How to code for a multidisciplinary tumor conference

Melanie Witt, RN, MA

There are two coding choices for team conferences involving physician participation. If the patient and/or family is present, the CPT instruction is to bill a problem E/M service code (99201-99215) based on the time spent during this coordination of care/counseling. Documentation would include details about the conference decisions and implications for care, rather than history or examination.

If the patient is not present, report 99367 (Medical team conference with interdisciplinary team of health care professionals, patient and/or family not present, 30 minutes or more; participation by physician), but note that this code was developed under the assumption that the conference would be performed in a facility setting. Diagnostic coding would be breast cancer.

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The author reports no financial relationships relevant to this article.

This is an excerpt from a companion coding resource for breast cancer–related procedures by Ms. Witt. To read the companion article, “Coding for breast cancer–related procedures: A how-to guide,” in its entirety, click here.

Image-guided lumpectomy

Advances in breast imaging have led to increased identification of nonpalpable breast cancers. Surgical excision of nonpalpable breast lesions requires image guidance, which can be done using a variety of techniques.

Wire-guided localization (WGL) has been used in practice for the past 40 years. The procedure involves placement of a hooked wire under local anesthesia using either mammographic or ultrasound guidance. This procedure is mostly done in the radiology department on the same day as the surgery and requires that the radiologist coordinate with the OR schedule. Besides scheduling conflicts and delays in surgery, this procedure can be complicated by wires becoming dislodged, transected, or migrated, and limits the surgeon’s ability to cosmetically hide the scar in relation to position of the wire. It is uncomfortable for the patient, who must be transported from the radiology department to the OR with a wire extruding from her breast.

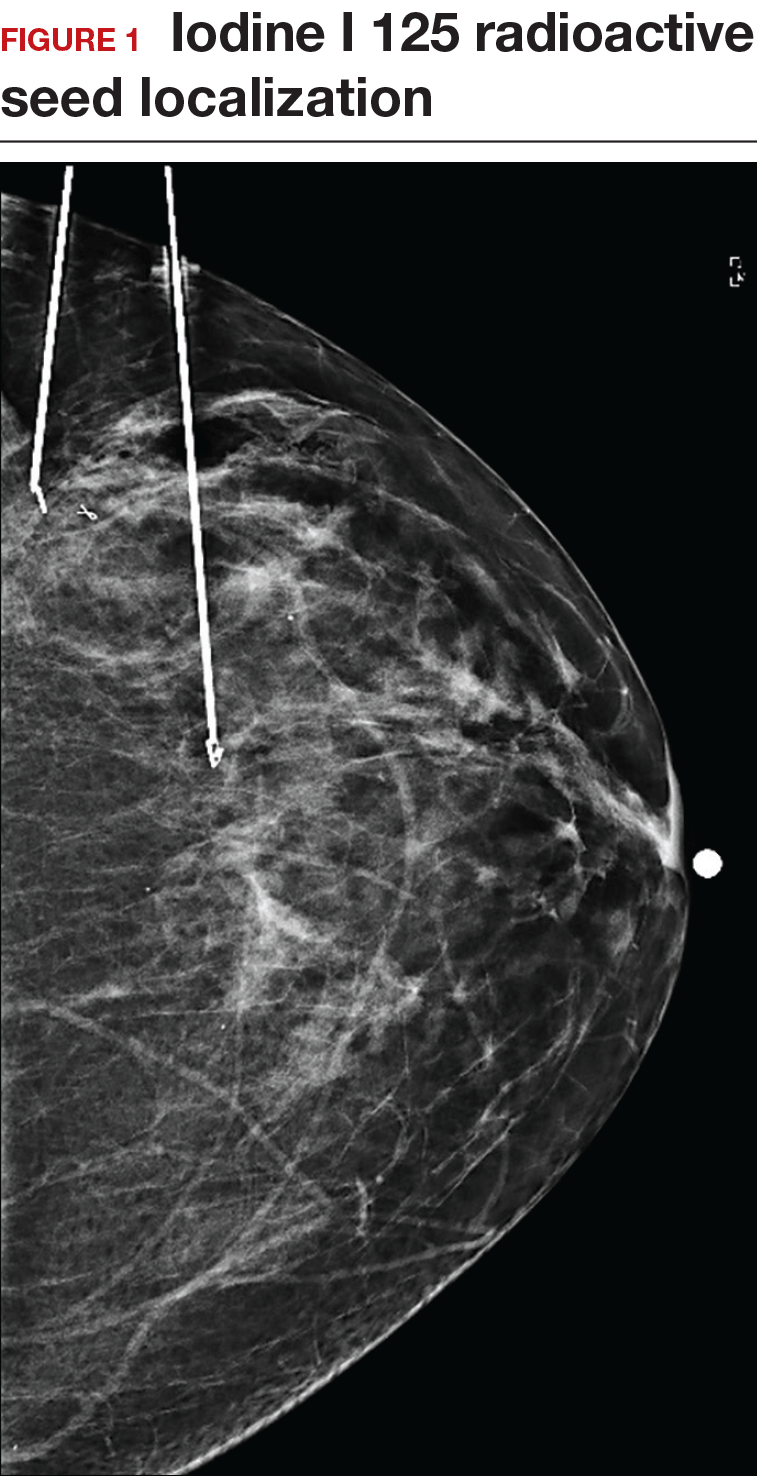

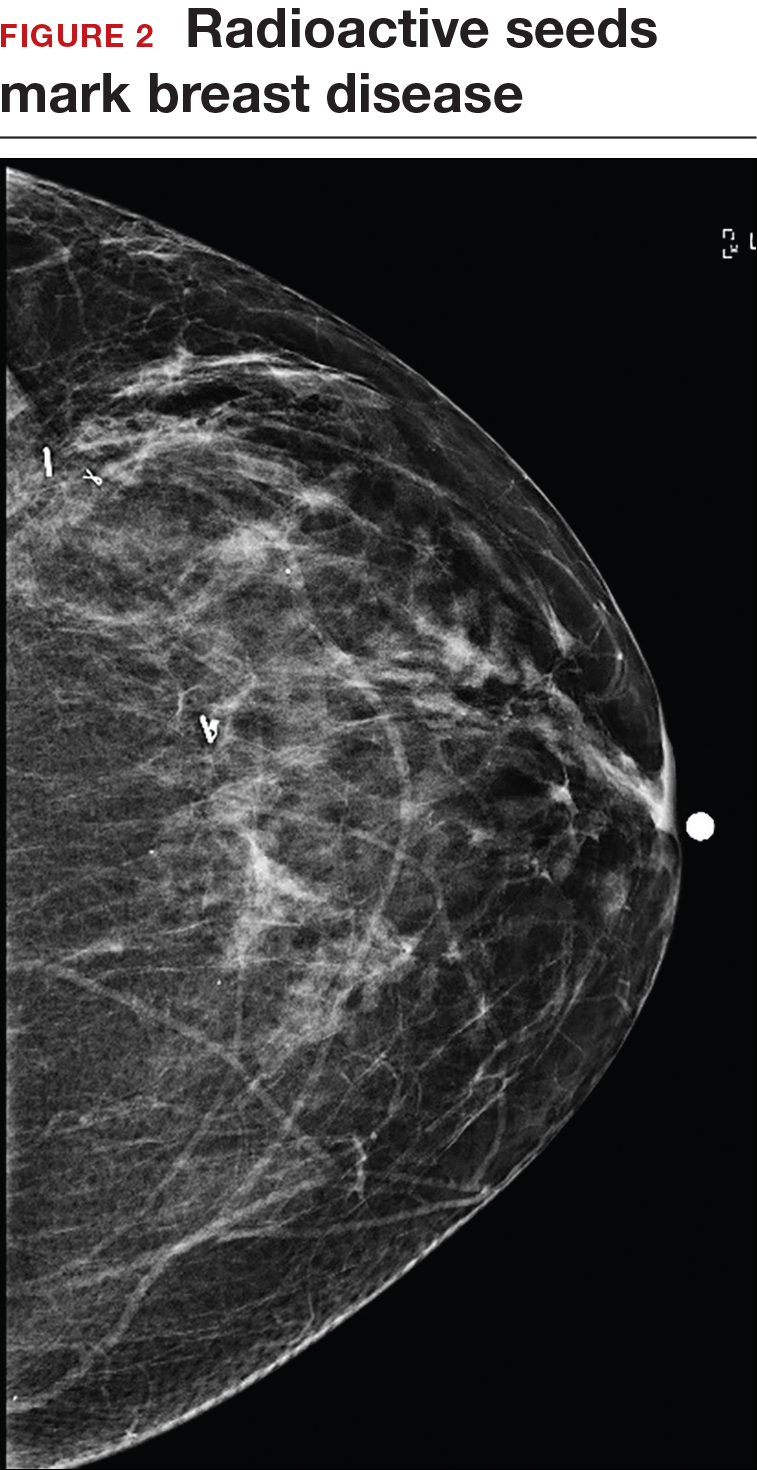

An alternative localization technique is placement of a radioactive source within the tumor, which can then be identified in the OR with a gamma probe.

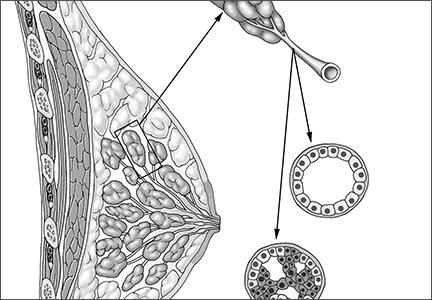

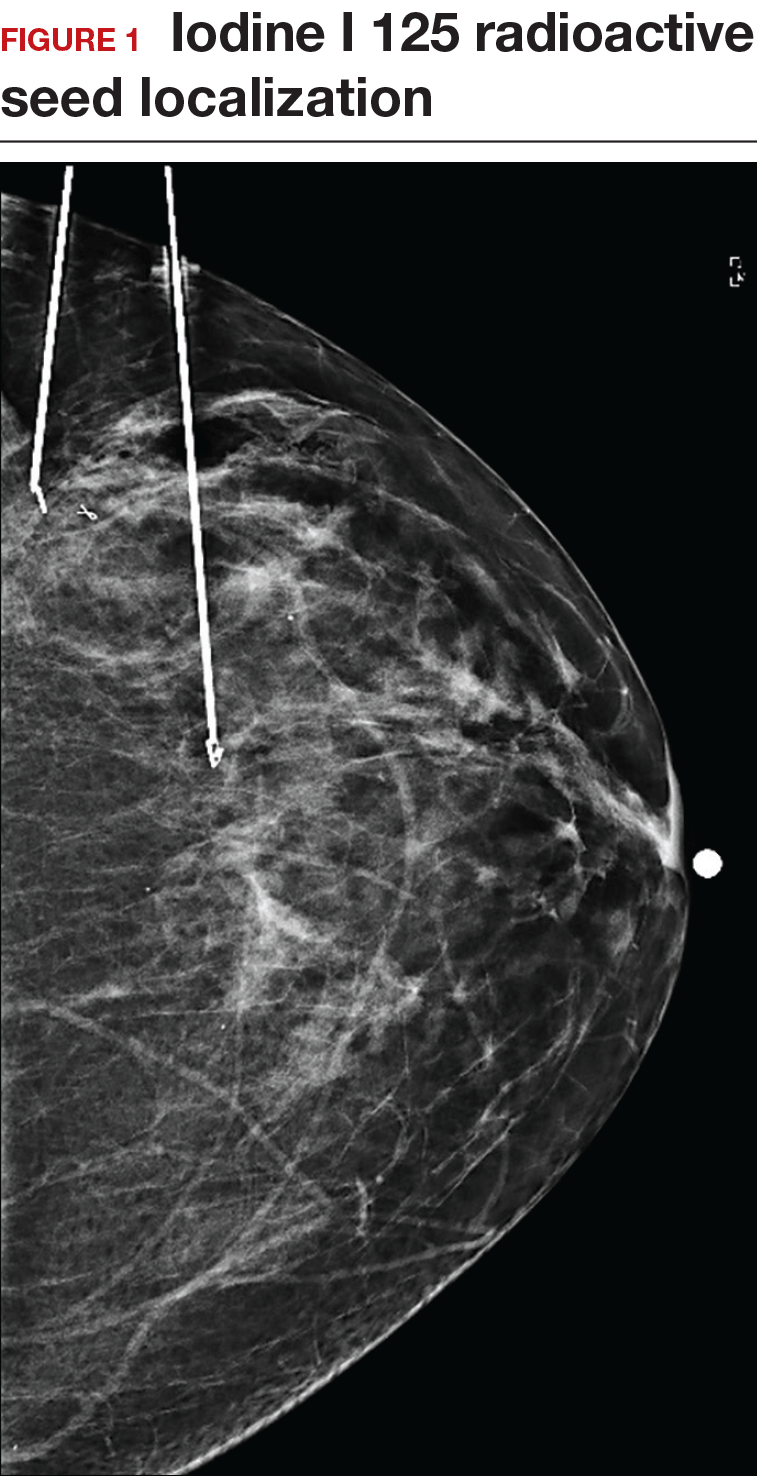

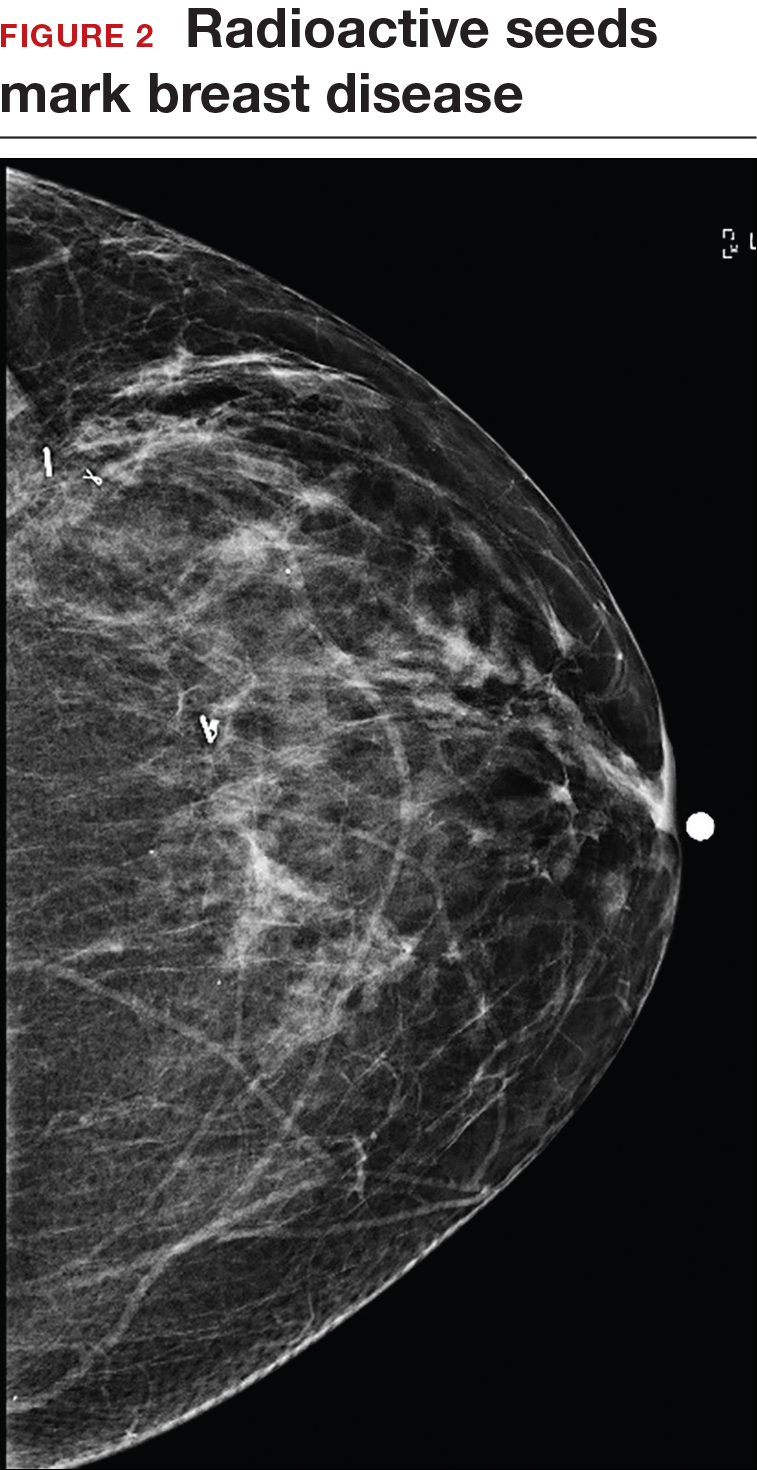

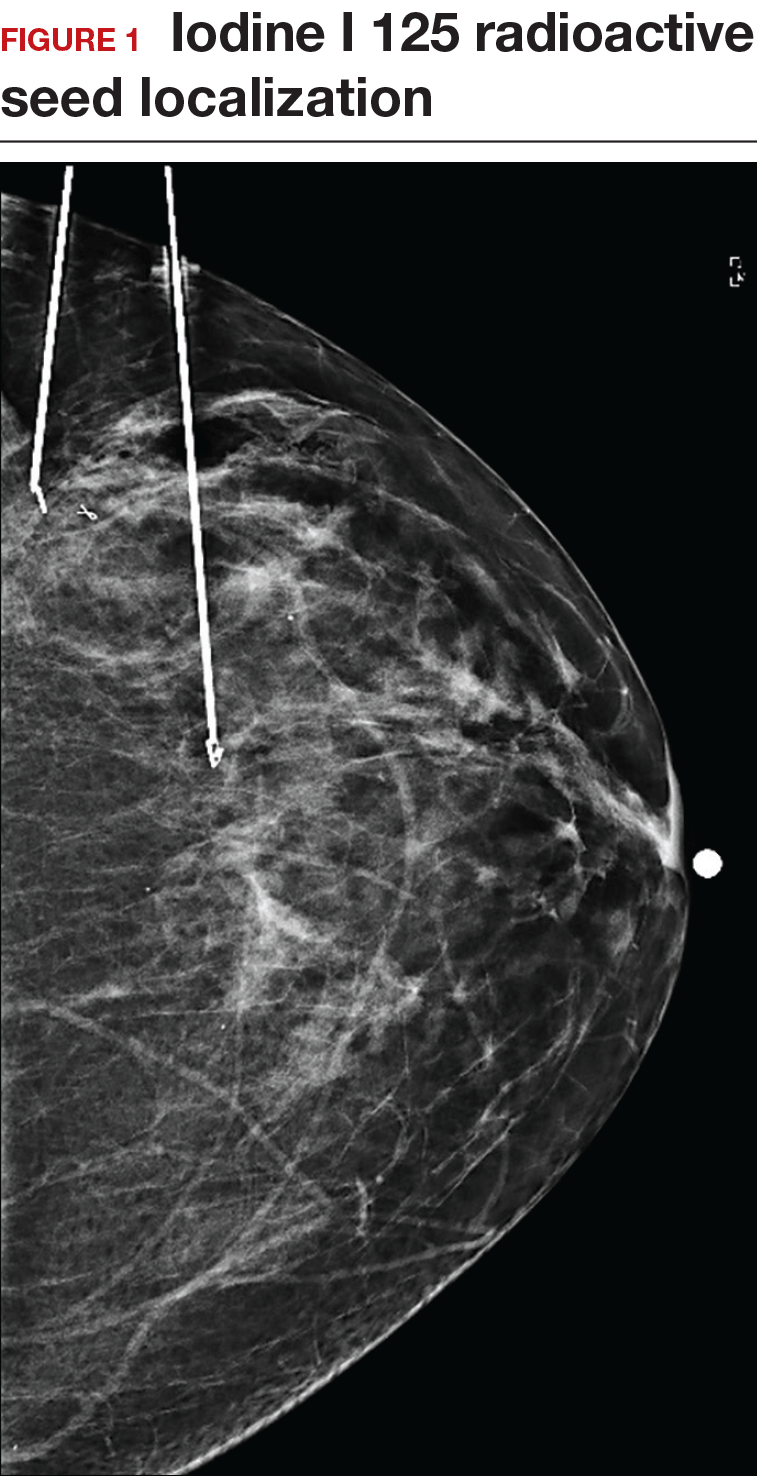

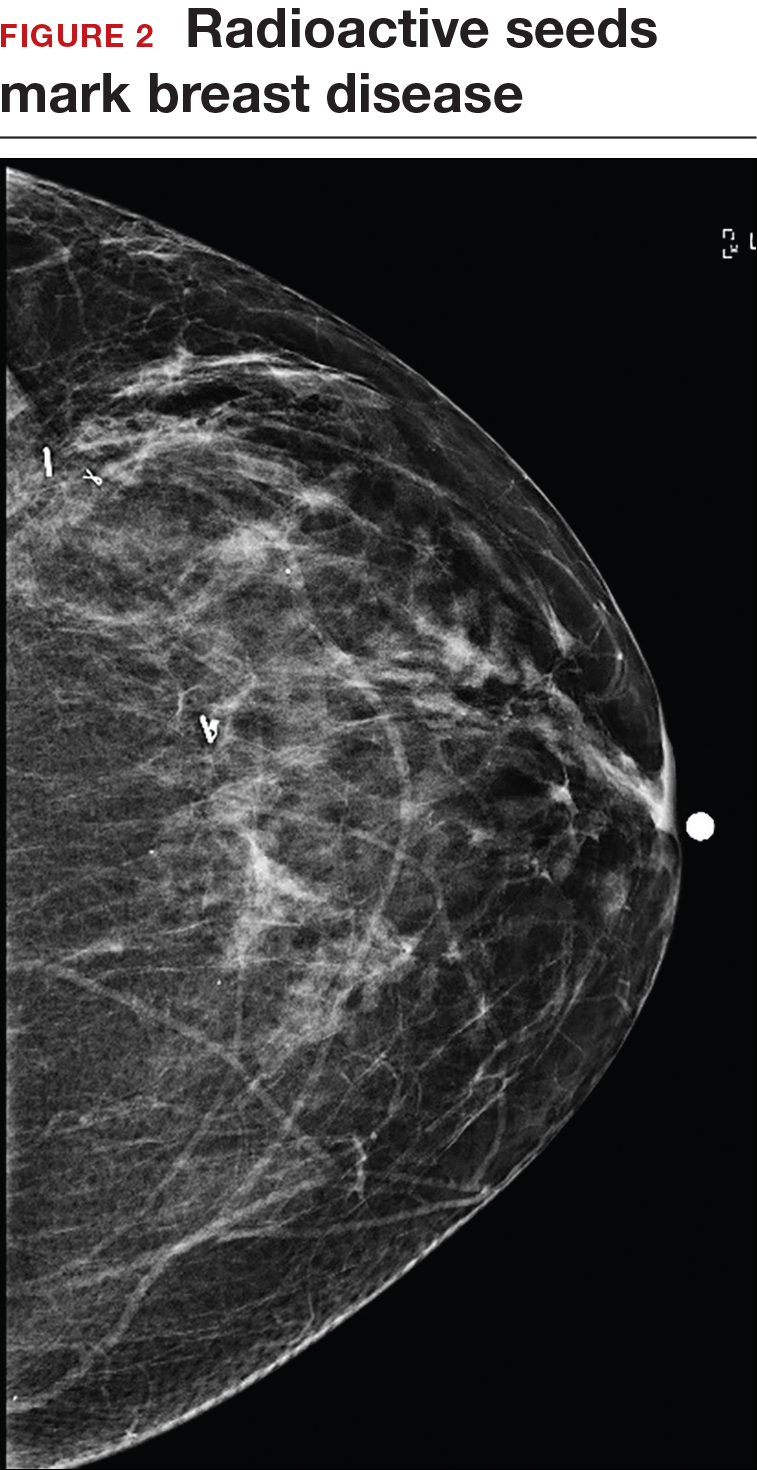

Iodine I 125 Radioactive seed localization (RSL) involves placing a 4-mm titanium radiolabeled seed into the breast lesion under mammographic or ultrasound guidance (FIGURES 1 and 2). The procedure can be performed a few days before surgery in the radiology department, and there is less chance for the seed to become displaced or dislodged. This technique provides scheduling flexibility for the radiologist and reduces OR delays. The surgeon uses the same gamma probe for sentinel node biopsy to find the lesion in the breast, using the setting specific for iodine I 125. Incisions can be tailored anywhere in the breast, and the seed is detected by a focal gamma signal. Once the lumpectomy is performed, the specimen is probed and radiographed to confirm removal of the seed and adequate margins.

Limitations of this procedure include potential loss of the seed during the operation and radiation safety issues regarding handling and disposal of the radioactive isotope. Once the seed has been placed in the patient’s body, it must be removed surgically, as the half-life of iodine I 125 is long (60 days).5 Care must therefore be taken to optimize medical clearance prior to seed placement and to avoid surgery cancellations.

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) allows the surgeon to identify the lesion under general anesthesia in the OR, which is more comfortable for the patient. The surgical incision can be tailored cosmetically and the lumpectomy can be performed with real-time ultrasound visualization of the tumor during dissection. This technique eliminates the need for a separate preoperative seed or wire localization in radiology. However, it can be used only for lesions or clips that are visible by ultrasound. The excised specimen can be evaluated for confirmation of tumor removal and adequate margins via ultrasound and re-excision of close margins can be accomplished immediately if needed.

Results of a meta-analysis of WGL versus IOUS demonstrated a significant reduction of positive margins with the use of IOUS.6 Results of the COBALT trial, in which patients were assigned randomly to excision of palpable breast cancers with either IOUS or palpation, demonstrated a 14% reduction in positive margins in favor of IOUS.7 Surgeon-performed breast ultrasound requires advanced training and accreditation in breast ultrasound through a rigorous certification process offered by the American Society of Breast Surgeons (www.breastsurgeons.org).

Oncoplastic lumpectomy

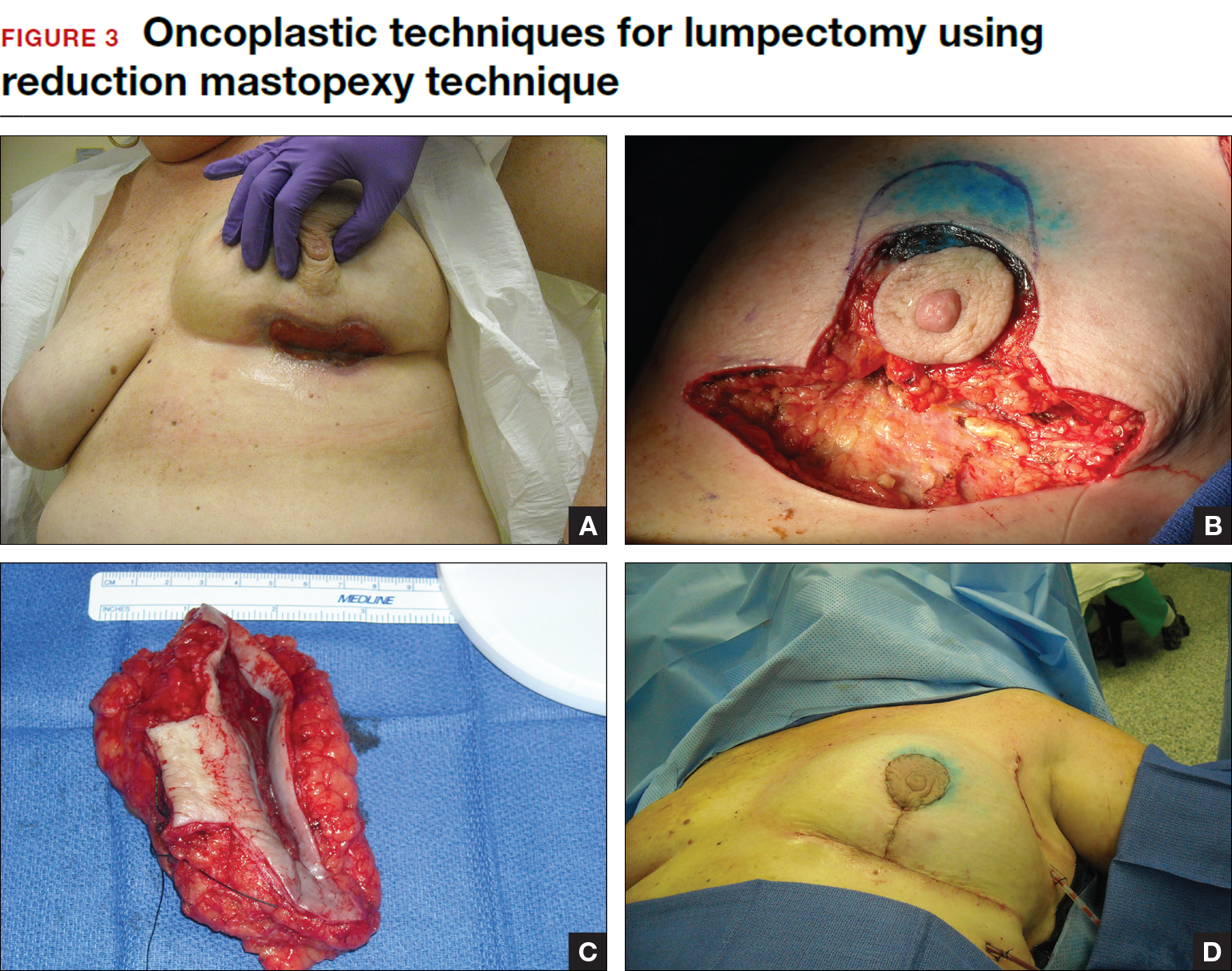

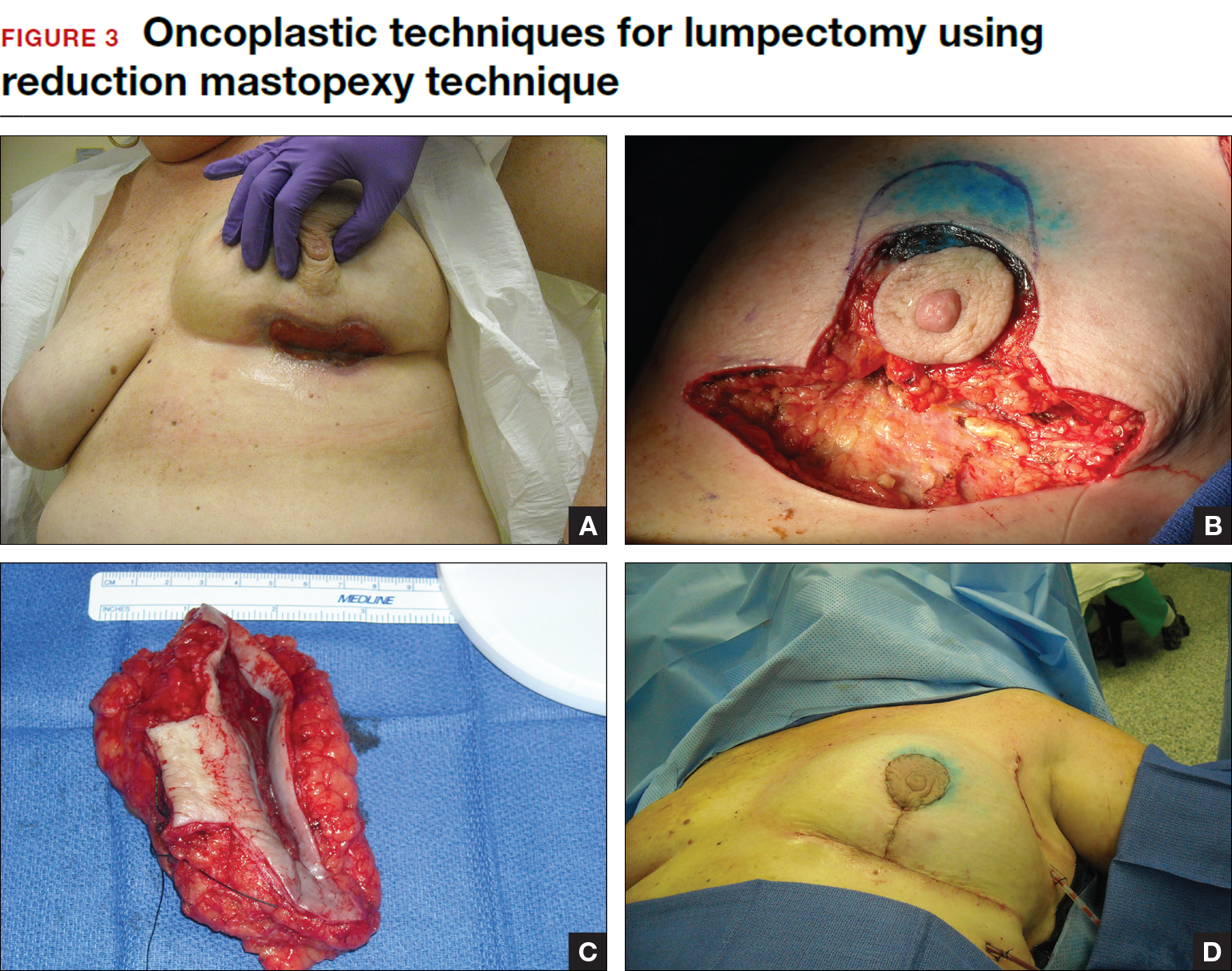

This approach to lumpectomy combines adequate oncologist resection of the breast tumor with plastic surgery techniques to achieve superior cosmesis. This approach allows complete removal of the tumor with negative margins, yet maintains the normal shape and contour of the breast. Two techniques have been described: volume displacement and volume replacement.

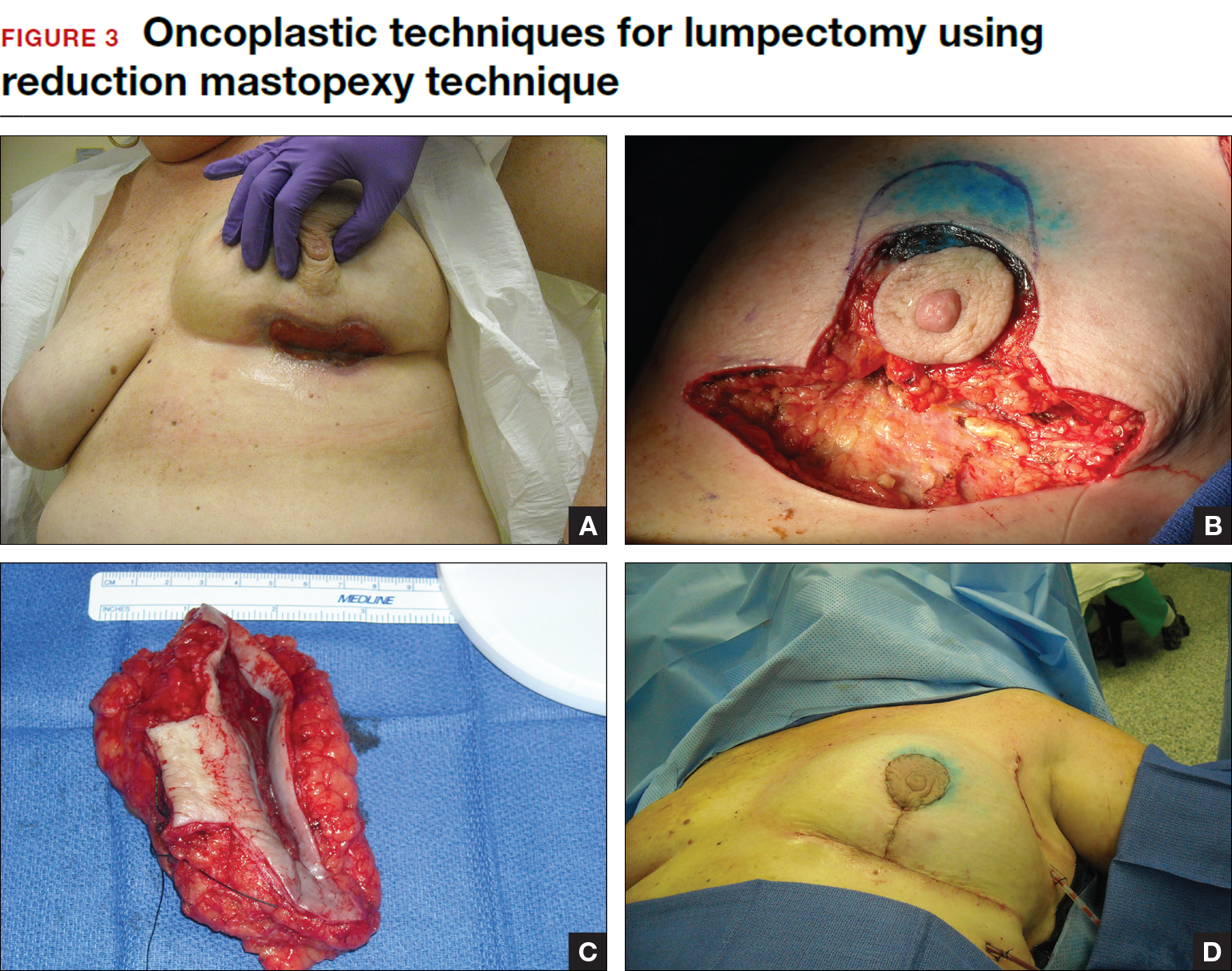

With the volume displacement technique, the surgeon uses adjacent tissue advancement to fill the lumpectomy cavity with the patient’s own surrounding breast tissue (FIGURE 3). The volume replacement technique requires the transposition of autologous tissue from elsewhere in the body.

Oncoplastic lumpectomy allows more women with larger tumors to undergo breast conservation with better cosmetic results. It reduces the number of mastectomies performed without compromising local control and avoids the need for extensive plastic surgery reconstruction and implants. Special effort and attention must be paid to ensure adequate margins utilizing intraoperative specimen radiograph and pathology evaluation.

This procedure requires that the surgeon acquire specialized skills and knowledge of oncologic and plastic surgery techniques, and it is best performed with the collaboration of a multidisciplinary team. Compared with conventional lumpectomy or mastectomy, oncoplastic breast conservation has been shown to reduce re-excision rates, and it has similar rates of local and distant recurrence and similar disease-free survival and overall survival.8,9

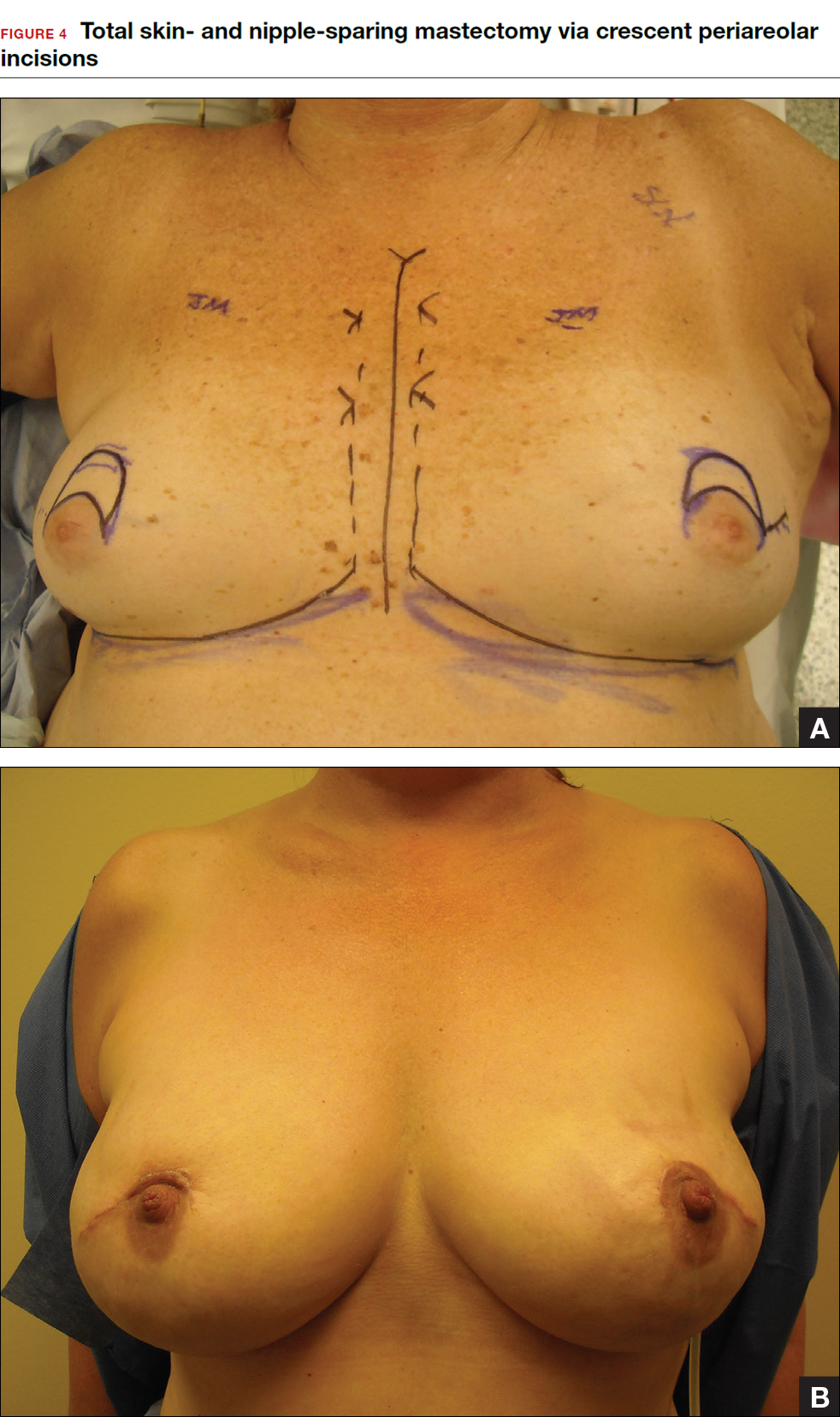

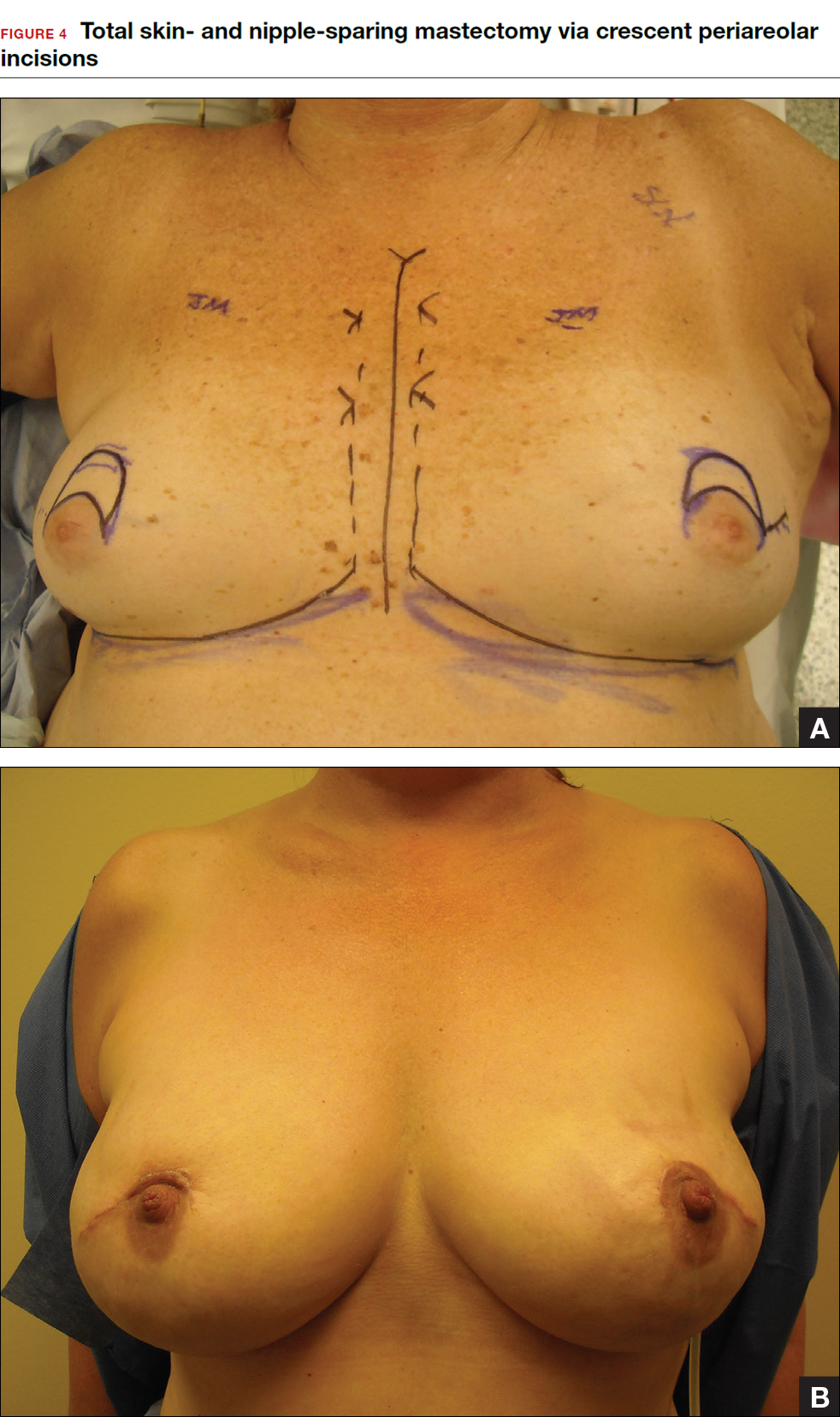

Total skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy

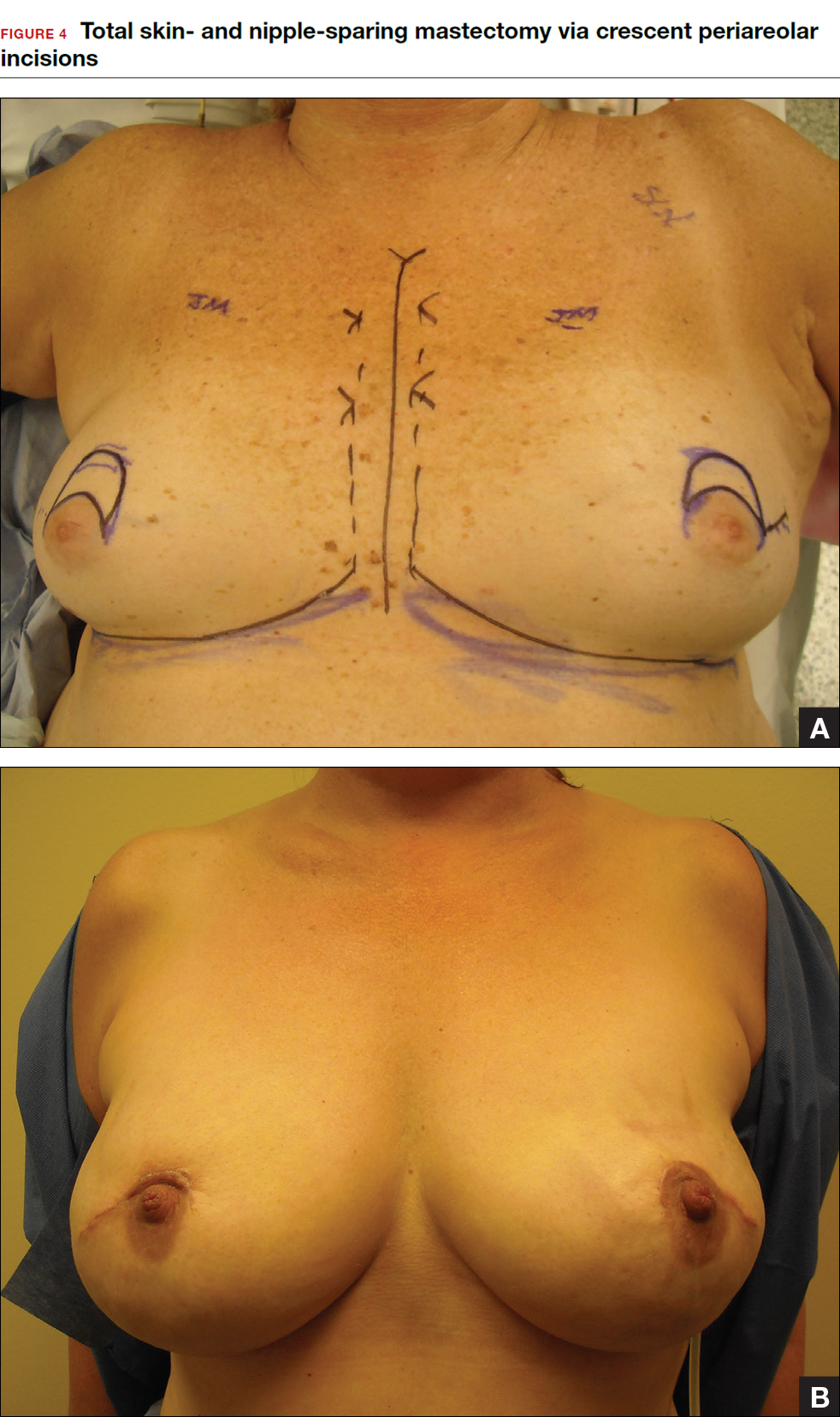

Some patients do not have the option of breast conservation. Women with multicentric breast cancer (more than 1 tumor in different quadrants of the breast) are better served with mastectomy. Surgical techniques for mastectomy have improved and provide women with various options. One option is skin- and nipple-sparing mastectomy, which preserves the skin envelope overlying the breast (including the skin of the nipple and areola) while removing the glandular elements of the breast and the majority of ductal tissue beneath the nipple-areola complex (FIGURE 4). This surgery can be performed via hidden scars at the inframammary crease or periareolar and is combined with immediate reconstruction, which provides an excellent cosmetic result.

Surgical considerations include removing glandular breast tissue within its anatomic boundaries while maintaining the blood supply to the skin and nipple-areola complex. Furthermore, there must be close dissection of ductal tissue beneath the nipple-areola complex and intraoperative frozen section of the nipple margin in cancer cases. Nipple-sparing mastectomy is oncologically safe in carefully selected patients who do not have cancer near or within the skin or nipple (eg, Paget disease).10 It is also safe as a prophylactic procedure for patients with genetic mutations, such as BRCA1 and BRCA2.11 The procedure is not ideal for smokers or patients with large, pendulous breasts. There is a 3% risk of breast cancer recurrence at the nipple or in the skin or muscle.10 Surgical complications include a 10% to 20% risk of skin or nipple necrosis.12

How do we manage the lymph nodes: Axillary dissection vs sentinel node biopsy?

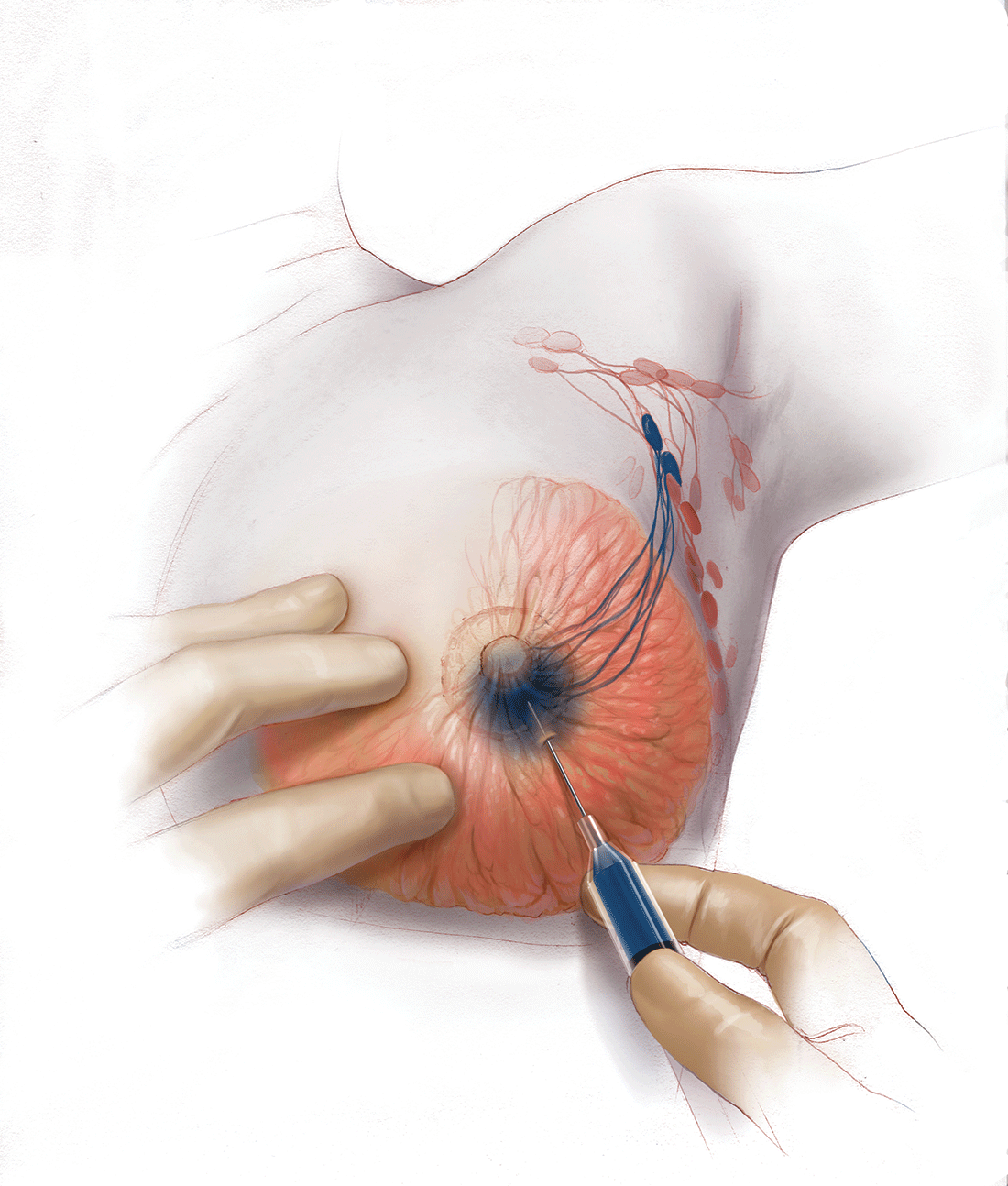

Evaluation of the axillary nodes is currently part of breast cancer staging and can help the clinician determine the need for adjuvant chemotherapy. It also may assist in assessing the need for extending the radiation field beyond the breast to include the regional lymph nodes. Patients with early stage (stage I and II) breast cancer who do not have abnormal palpable lymph nodes or biopsy-proven metastasis to axillary nodes qualify for sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy.

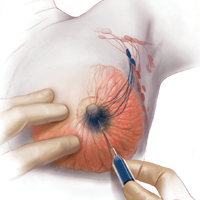

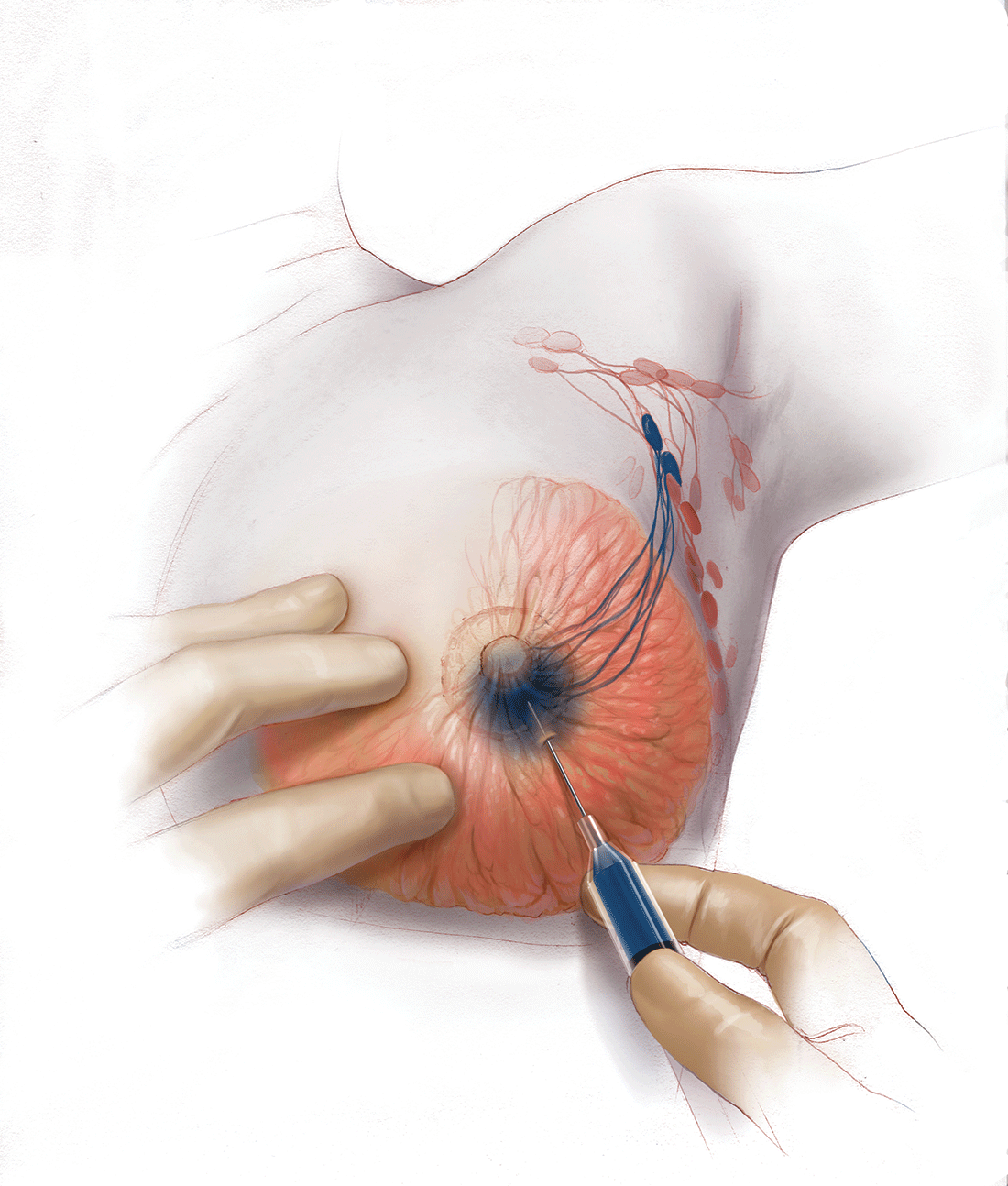

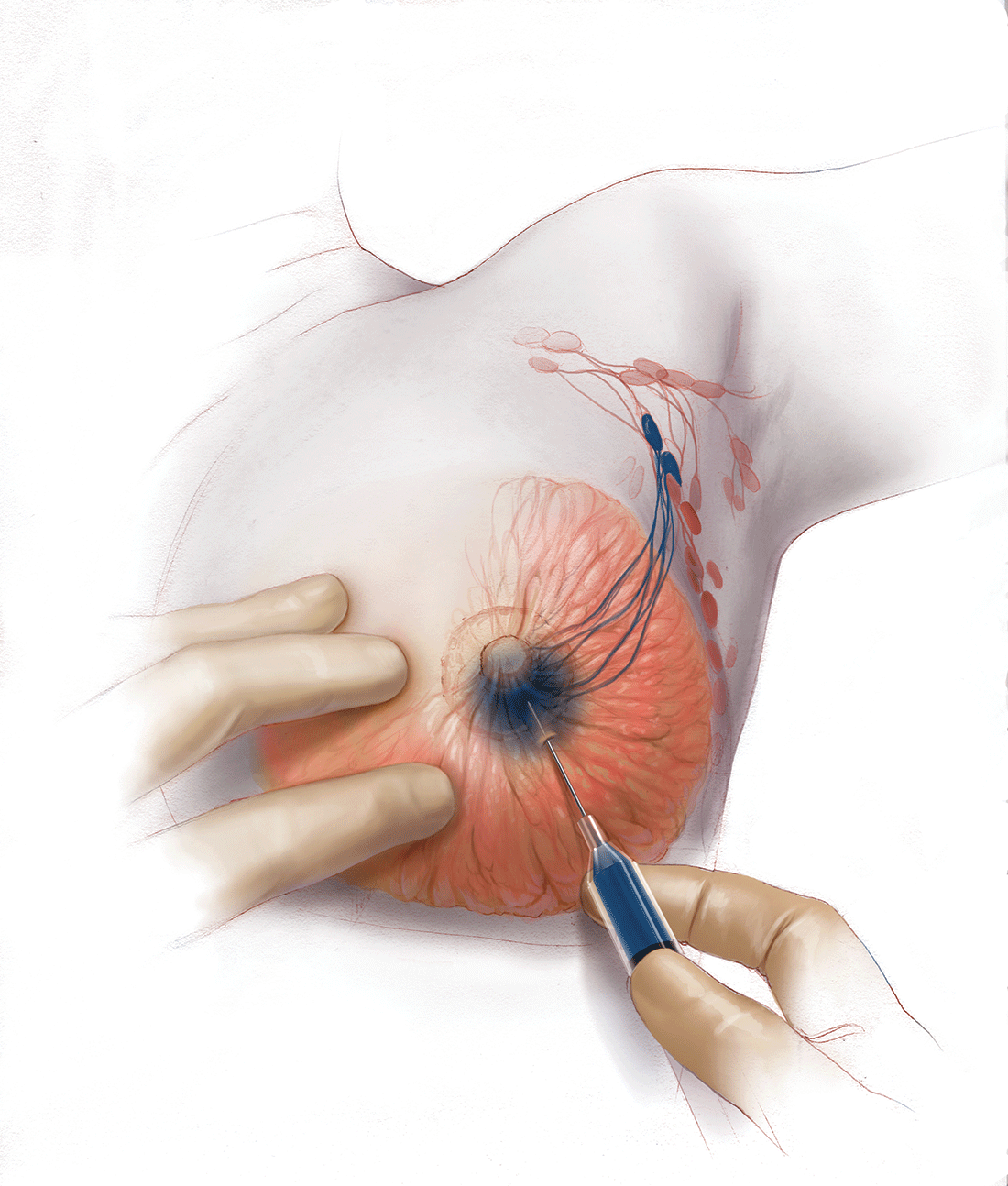

Sentinel node biopsy = less morbidity with no loss of accuracy. Compared with axillary lymph node dissection (ALND; removing all the level I and II nodes in the axilla), SLN biopsy has a 98% accuracy and is associated with less morbidity from lymphedema. The procedure involves injecting the breast with 2 tracers: a radioactive isotope, injected into the breast within 24 hours of the operation, and isosulfan blue dye, injected into the breast in the OR at the time of surgery (see illustration). Both tracers travel through the breast lymphatics and concentrate in the first few lymph nodes that drain the breast. The surgery is performed through a separate axillary incision, and the blue and radioactive lymph nodes are individually dissected and removed for pathologic evaluation. On average, 2 to 4 sentinel nodes are removed, including any suspicious palpable nodes. In experienced hands, this procedure has a false-negative rate of less than 5% to 10%.13

Axillary node dissection no longer standard of care. The indication for a completion ALND has changed based on the results of the randomized trial, ACOSOG Z0011.14 In this trial, patients with early stage breast cancer and 1 to 2 positive SLNs who were undergoing breast conservation therapy with radiation and adjuvant systemic therapy were randomly assigned to ALND or no ALND. (The trial did not include patients who were undergoing mastectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, or who had more than 2 metastatic lymph nodes.) The investigators found no difference in overall or disease-free survival or local-regional recurrence between the 2 treatment groups over 9.2 years of follow up.14

Based on this practice-changing trial result, guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network no longer recommend completion ALND for patients who meet the ACOSOG Z0011 criteria. For patients who do not meet ACOSOG Z0011 criteria, we do intraoperative pathologic lymph node assessment with either frozen section or imprint cytology, and we perform immediate ALND when results are positive.

Indications for SLN biopsy include:

- invasive breast cancer with clinically negative axillary nodes

- ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with microinvasion or extensive enough to require mastectomy

- clinically negative axillary nodes after neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Contraindications for SLN biopsy include:

- bulky palpable lymphadenopathy

- pregnancy, as the safety of radioactive isotope and blue dye is not well studied; in isotope mapping the radiation dose is small and within safety limits for pregnant patients

- inflammatory breast cancer.

Complications of any axillary surgery may include risk of lymphedema (5% with SLN biopsy and 30% to 40% with ALND).15 Other complications include neuropathy of the affected arm with chronic pain and numbness of the skin.

Positive trends: Improved patient outcomes, specialized clinician training

Management of breast cancer has changed dramatically over the past several decades. More women are surviving breast cancer thanks to improvements in early detection, an individualized treatment approach with less aggressive surgery, and more effective targeted systemic therapies. A multidisciplinary, team-oriented approach with emphasis on minimally invasive biopsy and better cosmetic outcomes has enhanced quality of care.

Complexity in breast disease management has led to the development of formal fellowship training in breast surgical oncology. Studies have demonstrated that patients treated by high-volume breast surgeons are more satisfied with their care and have improved cancer outcomes.16,17 Women should be aware that they have different options for their breast cancer care, and surgeons with advanced specialization in this field may provide optimal results and better quality of care.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to rbarbieri@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Nichols HB, Berrington de Gonzalez A, Lacey JV Jr, Rosenberg PS, Anderson WF. Declining incidence of contralateral breast cancer in the United States from 1975 to 2006. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(12):1564–1569.

- Wong SM, Freedman RA, Sagara Y, Aydogan F, Barry WT, Golshan M. Growing use of contralateral prophylactic mastectomy despite no improvement in long-term survival for invasive breast cancer [published online ahead of print March 8, 2016]. Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001698.

- Miller ME, Czechura T, Martz B, et al. Operative risks associated with contralateral prophylactic mastectomy: a single institution experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(13):4113–4120.

- Zhang X, Zhang XJ, Zhang TY, et al. Effect and safety of dual anti-human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 therapy compared to monotherapy in patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2-positive breast cancer: a systematic review. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:625.