User login

Association of Atrial Fibrillation and/or Flutter With Adverse Cardiac Outcomes and Mortality in Patients With Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by the presence of ≥ 1 accessory pathways and the development of both recurrent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) and supraventricular tachycardia that can lead to further malignant arrhythmias resulting in sudden cardiac death (SCD).1-7 Historically, incidental, ventricular pre-excitation on electrocardiogram has conferred a relatively low SCD risk in adults; however, newer WPW syndrome data suggest the endpoint may not be as benign as previously thought.7 The current literature has defined atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, rather than symptoms, as an independent risk factor for malignant arrhythmias. Still, long-term data detailing the association of AF with serious cardiac events and death in patients with WPW syndrome are still limited.1-7

While previous guidelines for the treatment of WPW syndrome only recommended routine electrophysiology testing (EPT) with liberal catheter ablation for symptomatic individuals, the 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines now suggest its potential benefit for risk stratification in the asymptomatic population.8-12 Given the limited existing data, more long-term studies are needed to corroborate the latest EPT recommendations before routinely applying them in practice. Furthermore, since concomitant AF can lead to adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with WPW syndrome, additional data evaluating this association are also necessary. In this study, we aimed to determine the impact of atrial fibrillation and/or flutter (AF/AFL) on adverse cardiac outcomes and mortality in patients with WPW syndrome.

METHODS

This study used data from the Military Health System (MHS) Database Repository. The MHS is one of the largest health care systems in the country and includes information on about 10 million active duty and retired military service members and their families (51% male; 49% female).13,14 Data were fully anonymized and complied in accordance with federal and state laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study Design

This retrospective, observational cohort study identified MHS patients with WPW syndrome from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2019. Patients were included if they had ≥ 2 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for WPW syndrome (ICD-9, 426.7; ICD-10, I45.6) on separate dates; were aged ≥ 18 years at index date; and had ≥ 1 year of continuous eligibility prior to the index date (enrollment gaps ≤ 30 days were considered continuous). Patients were then divided into 2 subgroups by the presence or absence of AF/AFL using diagnostic codes. Patients were excluded if they had evidence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, permanent pacemaker or were missing age or sex data. Patients were followed from index date until the first occurrence of the outcome of interest, MHS disenrollment, or the end of the study period.

Cardiac composite outcomes comprised of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), ventricular fibrillation (VF), ventricular tachycardia and death, as well as death specifically, were the outcomes of interest and assessed after index date using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Death was defined as all-cause mortality. Time to event was calculated based on the date of the initial component from the composite outcome and date of death specifically for mortality. Those not experiencing an outcome were followed until MHS disenrollment or the end of the study period.

Various patient characteristics were assessed at index including age, sex, military sponsor (the patient’s active or retired duty member through which their dependent receives TRICARE benefits) rank and branch, geographic region, type of US Department of Defense beneficiary, and index year. Clinical characteristics were assessed over a 1-year baseline period prior to index date and included the number of cardiologist and clinical visits for WPW syndrome, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores calculated from diagnostic codes outlined in the Quan coding method, and preindex time.15 Comorbidities were assessed at baseline and defined as having ≥ 1 ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for a corresponding condition within 1 year prior to index.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were assessed and descriptive statistics for categorical and continuous variables were presented accordingly. To assess bivariate association with exposure, χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables, while t tests were used to compare continuous variables by exposure status. Incidence proportions and rates were reported for each outcome of interest. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to assess the bivariate association between exposure and study outcomes. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed to estimate the association between AF/AFL and time to each of the outcomes. Multiple models were designed to assess cardiac and metabolic covariates, in addition to baseline characteristics. This included a base model adjusted for age, sex, military sponsor rank and branch, geographic region, and duty status.

Additional models adjusted for cardiac and metabolic confounders and CCI score. A comprehensive model included the base, cardiac, and metabolic covariates. Multicollinearity between covariates was assessed. Variables with a variance inflation factor > 4 or a tolerance level < 0.1 were added to the models. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of the association between AF/AFL and the study outcomes. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 for Windows.

RESULTS

From 2014 through 2019, 35,539 patients with WPW syndrome were identified in the MHS, 5291 had AF/AFL (14.9%); 19,961 were female (56.2%), the mean (SD) age was 62.9 (18.0) years, and 11,742 were aged ≥ 75 years (33.0%) (Table 1).

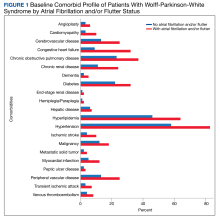

There were 4121 (11.6%), 322 (0.9%), and 848 (2.4%) patients with AF, AFL, and both arrhythmias, respectively. The mean (SD) number of cardiology visits was 3.9 (3.0). The mean (SD) baseline CCI score for the AF/AFL subgroup was 5.9 (3.5) vs 3.7 (2.2) for the non-AF/AFL subgroup (P < .001). The most prevalent comorbid conditions were hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes (P < .001) (Figure 1).

Composite Outcomes

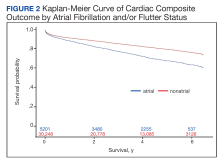

In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.4 (2.0) years comprising 119,682 total person-years, the components of the composite outcome occurred 6506 times with an incidence rate of 5.44 per 100 person-years. Ventricular tachycardia was the most common event, occurring 3281 times with an incidence rate of 2.74 per 100 person-years. SCA and VF occurred 841 and 135 times with incidence rates of 0.70 and 0.11 per 100 person-years, respectively. Death was the initial event 2249 times with an incidence rate of 1.88 per 100 person-years. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of cardiac composite outcome by AF/AFL status.

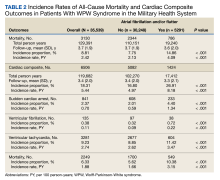

The subgroup with AF/AFL comprised 17,412 total person-years and 1424 cardiac composite incidences compared with 102,270 person years and 5082 incidences in the no AF/AFL group (Table 2). Comparing AF/AFL vs no AF/AFL incidence rates were 8.18 vs 4.97 per 100 person-years, respectively (P < .001). SCA and VF occurred 233 and 38 times and respectively had incidence rates of 1.34 and 0.22 per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL group vs 0.59 and 0.09 per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). There were 549 deaths and a 3.15 per 100 person-years incidence rate in the AF/AFL group vs 1700 deaths and a 1.66 incidence rate in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001).

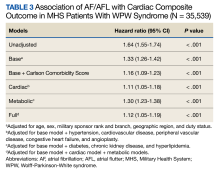

The HR for the composite outcome in the base model was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.26-1.42, P < .001) (Table 3). The association between AF/AFL and the composite outcome remained significant after adjusting for additional metabolic and cardiac covariates. The HRs for the metabolic and cardiac models were 1.30 (95% CI, 1.23-1.38, P < .001) and 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05-1.18, P < .001), respectively. After adjusting for the full model, the HR was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05-1.19, P < .001).

Mortality

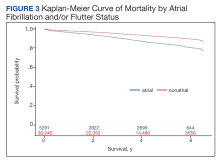

Over the 6-year study period, there was a lower survival probability for patients with AF/AFL. In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 129,391 total person-years, there were 3130 (8.8%) deaths and an incidence rate of 2.42 per 100 person-years. Death occurred 786 times with a 4.09 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL vs 2344 deaths and a 2.13 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). In the non-AF/AFL subgroup, death occurred 2344 times during a mean (SD) follow-up of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 110,151 total person-years. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of mortality by AF/AFL status.

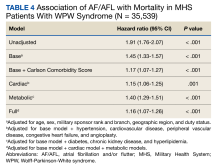

After adjusting for the base, metabolic and cardiac covariates, the HRs for mortality were 1.45 (95% CI, 1.33-1.57, P < .001), 1.40 (95% CI, 1.29-1.51, P < .001) and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.06-1.25, P = .001), respectively (Table 4). The HR after adjusting for the full model was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26, P < .001).

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, patients with WPW syndrome and comorbid AF/AFL had a significantly higher association with the cardiac composite outcome and death during a 3-year follow-up period when compared with patients without AF/AFL. After adjusting for confounding variables, the AF/AFL subgroup maintained a 12% and 16% higher association with the composite outcome and mortality, respectively. There was minimal difference in confounding effects between demographic data and metabolic profiles, suggesting one may serve as a proxy for the other.

To our knowledge, this is the largest WPW syndrome cohort study evaluating cardiac outcomes and mortality to date. Although previous research has shown the relatively low and mostly anecdotal SCD incidence within this population,our results demonstrate a higher association of adverse cardiac outcomes and death in an AF/AFL subgroup.16-18 Notably, in this study the AF/AFL cohort was older and had higher CCI scores than their counterparts (P < .001), thus inferring an inherently greater degree of morbidity and 10-year mortality risk. Our study is also unique in that the mean patient age was significantly older than previously reported (63 vs 27 years), which may suggest a longer living history of both ventricular pre-excitation and the comorbidities outlined in Figure 1.19 Given these age discrepancies, it is possible that our overall study population was still relatively low risk and that not all reported deaths were necessarily related to WPW syndrome. Despite these assumptions, when comparing the WPW syndrome subgroups, we still found the AF/AFL cohort maintained a statistically significant higher association with the 2 study outcomes, even after adjusting for the greater presence of comorbidities. This suggests that the presence of AF/AFL may still portend a worse prognosis in patients with WPW syndrome.

Although the association of AF and development of VF in patients with WPW syndrome—due to rapid conduction over the accessory pathway(s)—was first reported > 40 years ago, there has still been few large, long-term data studies exploring mortality in this cohort.19-25 Furthermore, even though the current literature attributes the development of AF with the electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, as well as intrinsic atrial architecture and muscle vulnerability, there is still equivocal consensus regarding EPT screening and ablation indications for asymptomatic patients with WPW syndrome.26-28 Notably, Pappone and colleagues demonstrated the potential benefit of liberal ablation indications for asymptomatic patients, arguing that the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway—ie, short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period, inducibility of atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, and multiple accessory pathway—rather than symptoms, are independent predictors of developing malignant arrhythmia.1-5

These findings contradict those reported by Obeyesekere and colleagues, who concluded that the low SCD incidence rates in patients with WPW syndrome precluded routine invasive screening.19,28 They argued that Pappone and colleagues used malignant arrhythmia as a surrogate marker for death, and that the positive predictive value of a short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period for developing malignant arrhythmia was lower than reported (15% vs 82%, respectively) and that its negative predictive value was 100%.1,19,28 Given these conflicting recommendations, we hope our data elucidates the higher association of adverse outcomes and support considerations for more intensive EPT indications in patients with WPW syndrome.

While our study does not report SCD incidence, it does provide robust and reliable mortality data that suggests a greater association of death within an AF/AFL subgroup. Our findings would support more liberal EPT recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome.1-5,8,9 In this study, the SCA incidence rate was more than double the rate in the AF/AFL cohort (P < .001) and is commonly the initial presenting event in WPW syndrome.9 Even though the reported SCD incidence rate is low in WPW syndrome, our data demonstrated an increased association of death within the AF/AFL cohort. Physicians should consider early risk stratification and ablation to prevent potential recurrent malignant arrhythmia leading to death.1-5,8,9,12,19,20

Limitations

As a retrospective study and without access to the National Death Index, we were unable to determine the exact cause or events leading to death and instead utilized all-cause mortality data. Subsequently, our observations may only demonstrate association, rather than causality, between AF/AFL and death in patients with WPW syndrome. Additionally, we could not distinguish between AF and AFL as the arrhythmia leading to death. However, since overall survivability was the outcome of interest, our adjusted HR models were still able to demonstrate the increased association of the composite outcome and death within an AF/AFL cohort.

Although a large cohort was analyzed, due to the constraints of utilizing diagnostic codes to determine study outcomes, we could not distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, nor how they were managed prior to the outcome event. However, as recent literature demonstrates, updated predictors of malignant arrhythmia and decisions for early EPT are similar for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and should be driven by the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, rather than symptomatology;thus, our inability to discern this should have negligible consequence in determining when to perform risk stratification and ablation.1

MHS eligible patients have direct access to care; the generalizability of our data may not necessarily correspond to a community population with lower socioeconomic status (we did adjust for military sponsor rank which has been used as a proxy), reduced access to care, or uninsured individuals. However, the prevalence of WPW syndrome within our cohort was comparable to the general population, 0.4% vs 0.1%-0.3%, respectively.13,14,19 Similarly, the incidence of AF within our population was comparable to the general population, 15% vs 16%-26%, respectively.23 These similar data points suggest our results may apply beyond MHS patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with WPW syndrome and AF/AFL have a higher association with adverse cardiac outcomes and death. Despite previously reported low SCD incidence rates in this population, our study demonstrates the increased association of mortality in an AF/AFL cohort. The limitations of utilizing all-cause mortality data necessitate further investigation into the etiology behind the deaths in our study population. Since ventricular pre-excitation can predispose patients to AF and potentially lead to malignant arrhythmia and SCD, understanding the cause of mortality will allow physicians to determine the appropriate monitoring and intervention strategies to improve outcomes in this population. Our results suggest consideration for more aggressive EPT screening and ablation recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome may be warranted.

1. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of WPW syndrome. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2015; 17 (Supplement A):A8-A11.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suv004

2. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Risk of malignant arrhythmias in initially symptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: results of a prospective long-term electrophysiological follow-up study. Circulation. 2012;125(5):661-668. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.065722

3. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Rosanio S, et al. Usefulness of invasive electrophysiologic testing to stratify the risk of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern: results from a large prospective long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(2):239-244. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02706-7

4. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014;130(10):811-819. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011154

5. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, et al. A randomized study of prophylactic catheter ablation in asymptomatic patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1803-1811. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035345

6. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. Asymptomatic ventricular preexcitation: a long-term prospective follow-up study of 293 adult patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(2):102-107. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.827550

7. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation a long-term prospective follow-up study of 184 asymptomatic children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(3):275-280. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.037

8. Al-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, et al. Risk Stratification for Arrhythmic Events in Patients With Asymptomatic Pre-Excitation: A Systematic Review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1624-1638. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.018

9. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias). Circulation. 2003;108(15):1871-1909.doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000091380.04100.84

10. Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF); PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm. 2012;9(6):1006-1024. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050

11. Cohen M, Triedman J. Guidelines for management of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation: brave new world or Pandora’s box?. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(2):187-189. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001528

12. Svendsen JH, Dagres N, Dobreanu D, et al. Current strategy for treatment of patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and asymptomatic preexcitation in Europe: European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace. 2013;15(5):750-753. doi:10.1093/europace/eut094

13. Gimbel RW, Pangaro L, Barbour G. America’s “undiscovered” laboratory for health services research. Med Care. 2010;48(8):751-756. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35be8

14. Dorrance KA, Ramchandani S, Neil N, Fisher H. Leveraging the military health system as a laboratory for health care reform. Mil Med. 2013;178(2):142-145. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-12-00168

15. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83

16. Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Behr ER, Sharma S, Sheppard M. Sudden Cardiac Death in Pre-Excitation and Wolff-Parkinson-White: Demographic and Clinical Features. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(12):1644-1645. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.023

17. Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993;87(3):866-873. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.3.866

18. Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. Am Heart J. 2001;142(3):530-536. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.117779

19. Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;125(19):2308-2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350

20. Waspe LE, Brodman R, Kim SG, Fisher JD. Susceptibility to atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: role of the accessory pathway. Am Heart J. 1986;112(6):1141-1152. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(86)90342-x

21. Pietersen AH, Andersen ED, Sandøe E. Atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(5):38A-43A. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)91076-g

22. Della Bella P, Brugada P, Talajic M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with an accessory pathway: importance of the conduction properties of the accessory pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(6):1352-1356. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80146-9

23. Fujimura O, Klein GJ, Yee R, Sharma AD. Mode of onset of atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how important is the accessory pathway?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(5):1082-1086. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(90)90244-j

24. Montoya PT, Brugada P, Smeets J, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(2):144-150. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059860

25. Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, Pritchett EL, Smith WM, Gallagher JJ. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(20):1080-1085. doi:10.1056/NEJM197911153012003

26. Centurion OA. Atrial Fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation. 2011;4(1):287. Published 2011 May 4. doi:10.4022/jafib.287

27. Song C, Guo Y, Zheng X, et al. Prognostic Significance and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation of Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(9):1546-1550. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.07.021

28. Obeyesekere M, Gula LJ, Skanes AC, Leong-Sit P, Klein GJ. Risk of sudden death in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how high is the risk?. Circulation. 2012;125(5):659-660. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.085159

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by the presence of ≥ 1 accessory pathways and the development of both recurrent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) and supraventricular tachycardia that can lead to further malignant arrhythmias resulting in sudden cardiac death (SCD).1-7 Historically, incidental, ventricular pre-excitation on electrocardiogram has conferred a relatively low SCD risk in adults; however, newer WPW syndrome data suggest the endpoint may not be as benign as previously thought.7 The current literature has defined atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, rather than symptoms, as an independent risk factor for malignant arrhythmias. Still, long-term data detailing the association of AF with serious cardiac events and death in patients with WPW syndrome are still limited.1-7

While previous guidelines for the treatment of WPW syndrome only recommended routine electrophysiology testing (EPT) with liberal catheter ablation for symptomatic individuals, the 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines now suggest its potential benefit for risk stratification in the asymptomatic population.8-12 Given the limited existing data, more long-term studies are needed to corroborate the latest EPT recommendations before routinely applying them in practice. Furthermore, since concomitant AF can lead to adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with WPW syndrome, additional data evaluating this association are also necessary. In this study, we aimed to determine the impact of atrial fibrillation and/or flutter (AF/AFL) on adverse cardiac outcomes and mortality in patients with WPW syndrome.

METHODS

This study used data from the Military Health System (MHS) Database Repository. The MHS is one of the largest health care systems in the country and includes information on about 10 million active duty and retired military service members and their families (51% male; 49% female).13,14 Data were fully anonymized and complied in accordance with federal and state laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study Design

This retrospective, observational cohort study identified MHS patients with WPW syndrome from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2019. Patients were included if they had ≥ 2 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for WPW syndrome (ICD-9, 426.7; ICD-10, I45.6) on separate dates; were aged ≥ 18 years at index date; and had ≥ 1 year of continuous eligibility prior to the index date (enrollment gaps ≤ 30 days were considered continuous). Patients were then divided into 2 subgroups by the presence or absence of AF/AFL using diagnostic codes. Patients were excluded if they had evidence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, permanent pacemaker or were missing age or sex data. Patients were followed from index date until the first occurrence of the outcome of interest, MHS disenrollment, or the end of the study period.

Cardiac composite outcomes comprised of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), ventricular fibrillation (VF), ventricular tachycardia and death, as well as death specifically, were the outcomes of interest and assessed after index date using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Death was defined as all-cause mortality. Time to event was calculated based on the date of the initial component from the composite outcome and date of death specifically for mortality. Those not experiencing an outcome were followed until MHS disenrollment or the end of the study period.

Various patient characteristics were assessed at index including age, sex, military sponsor (the patient’s active or retired duty member through which their dependent receives TRICARE benefits) rank and branch, geographic region, type of US Department of Defense beneficiary, and index year. Clinical characteristics were assessed over a 1-year baseline period prior to index date and included the number of cardiologist and clinical visits for WPW syndrome, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores calculated from diagnostic codes outlined in the Quan coding method, and preindex time.15 Comorbidities were assessed at baseline and defined as having ≥ 1 ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for a corresponding condition within 1 year prior to index.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were assessed and descriptive statistics for categorical and continuous variables were presented accordingly. To assess bivariate association with exposure, χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables, while t tests were used to compare continuous variables by exposure status. Incidence proportions and rates were reported for each outcome of interest. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to assess the bivariate association between exposure and study outcomes. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed to estimate the association between AF/AFL and time to each of the outcomes. Multiple models were designed to assess cardiac and metabolic covariates, in addition to baseline characteristics. This included a base model adjusted for age, sex, military sponsor rank and branch, geographic region, and duty status.

Additional models adjusted for cardiac and metabolic confounders and CCI score. A comprehensive model included the base, cardiac, and metabolic covariates. Multicollinearity between covariates was assessed. Variables with a variance inflation factor > 4 or a tolerance level < 0.1 were added to the models. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of the association between AF/AFL and the study outcomes. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 for Windows.

RESULTS

From 2014 through 2019, 35,539 patients with WPW syndrome were identified in the MHS, 5291 had AF/AFL (14.9%); 19,961 were female (56.2%), the mean (SD) age was 62.9 (18.0) years, and 11,742 were aged ≥ 75 years (33.0%) (Table 1).

There were 4121 (11.6%), 322 (0.9%), and 848 (2.4%) patients with AF, AFL, and both arrhythmias, respectively. The mean (SD) number of cardiology visits was 3.9 (3.0). The mean (SD) baseline CCI score for the AF/AFL subgroup was 5.9 (3.5) vs 3.7 (2.2) for the non-AF/AFL subgroup (P < .001). The most prevalent comorbid conditions were hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes (P < .001) (Figure 1).

Composite Outcomes

In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.4 (2.0) years comprising 119,682 total person-years, the components of the composite outcome occurred 6506 times with an incidence rate of 5.44 per 100 person-years. Ventricular tachycardia was the most common event, occurring 3281 times with an incidence rate of 2.74 per 100 person-years. SCA and VF occurred 841 and 135 times with incidence rates of 0.70 and 0.11 per 100 person-years, respectively. Death was the initial event 2249 times with an incidence rate of 1.88 per 100 person-years. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of cardiac composite outcome by AF/AFL status.

The subgroup with AF/AFL comprised 17,412 total person-years and 1424 cardiac composite incidences compared with 102,270 person years and 5082 incidences in the no AF/AFL group (Table 2). Comparing AF/AFL vs no AF/AFL incidence rates were 8.18 vs 4.97 per 100 person-years, respectively (P < .001). SCA and VF occurred 233 and 38 times and respectively had incidence rates of 1.34 and 0.22 per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL group vs 0.59 and 0.09 per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). There were 549 deaths and a 3.15 per 100 person-years incidence rate in the AF/AFL group vs 1700 deaths and a 1.66 incidence rate in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001).

The HR for the composite outcome in the base model was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.26-1.42, P < .001) (Table 3). The association between AF/AFL and the composite outcome remained significant after adjusting for additional metabolic and cardiac covariates. The HRs for the metabolic and cardiac models were 1.30 (95% CI, 1.23-1.38, P < .001) and 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05-1.18, P < .001), respectively. After adjusting for the full model, the HR was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05-1.19, P < .001).

Mortality

Over the 6-year study period, there was a lower survival probability for patients with AF/AFL. In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 129,391 total person-years, there were 3130 (8.8%) deaths and an incidence rate of 2.42 per 100 person-years. Death occurred 786 times with a 4.09 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL vs 2344 deaths and a 2.13 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). In the non-AF/AFL subgroup, death occurred 2344 times during a mean (SD) follow-up of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 110,151 total person-years. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of mortality by AF/AFL status.

After adjusting for the base, metabolic and cardiac covariates, the HRs for mortality were 1.45 (95% CI, 1.33-1.57, P < .001), 1.40 (95% CI, 1.29-1.51, P < .001) and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.06-1.25, P = .001), respectively (Table 4). The HR after adjusting for the full model was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26, P < .001).

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, patients with WPW syndrome and comorbid AF/AFL had a significantly higher association with the cardiac composite outcome and death during a 3-year follow-up period when compared with patients without AF/AFL. After adjusting for confounding variables, the AF/AFL subgroup maintained a 12% and 16% higher association with the composite outcome and mortality, respectively. There was minimal difference in confounding effects between demographic data and metabolic profiles, suggesting one may serve as a proxy for the other.

To our knowledge, this is the largest WPW syndrome cohort study evaluating cardiac outcomes and mortality to date. Although previous research has shown the relatively low and mostly anecdotal SCD incidence within this population,our results demonstrate a higher association of adverse cardiac outcomes and death in an AF/AFL subgroup.16-18 Notably, in this study the AF/AFL cohort was older and had higher CCI scores than their counterparts (P < .001), thus inferring an inherently greater degree of morbidity and 10-year mortality risk. Our study is also unique in that the mean patient age was significantly older than previously reported (63 vs 27 years), which may suggest a longer living history of both ventricular pre-excitation and the comorbidities outlined in Figure 1.19 Given these age discrepancies, it is possible that our overall study population was still relatively low risk and that not all reported deaths were necessarily related to WPW syndrome. Despite these assumptions, when comparing the WPW syndrome subgroups, we still found the AF/AFL cohort maintained a statistically significant higher association with the 2 study outcomes, even after adjusting for the greater presence of comorbidities. This suggests that the presence of AF/AFL may still portend a worse prognosis in patients with WPW syndrome.

Although the association of AF and development of VF in patients with WPW syndrome—due to rapid conduction over the accessory pathway(s)—was first reported > 40 years ago, there has still been few large, long-term data studies exploring mortality in this cohort.19-25 Furthermore, even though the current literature attributes the development of AF with the electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, as well as intrinsic atrial architecture and muscle vulnerability, there is still equivocal consensus regarding EPT screening and ablation indications for asymptomatic patients with WPW syndrome.26-28 Notably, Pappone and colleagues demonstrated the potential benefit of liberal ablation indications for asymptomatic patients, arguing that the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway—ie, short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period, inducibility of atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, and multiple accessory pathway—rather than symptoms, are independent predictors of developing malignant arrhythmia.1-5

These findings contradict those reported by Obeyesekere and colleagues, who concluded that the low SCD incidence rates in patients with WPW syndrome precluded routine invasive screening.19,28 They argued that Pappone and colleagues used malignant arrhythmia as a surrogate marker for death, and that the positive predictive value of a short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period for developing malignant arrhythmia was lower than reported (15% vs 82%, respectively) and that its negative predictive value was 100%.1,19,28 Given these conflicting recommendations, we hope our data elucidates the higher association of adverse outcomes and support considerations for more intensive EPT indications in patients with WPW syndrome.

While our study does not report SCD incidence, it does provide robust and reliable mortality data that suggests a greater association of death within an AF/AFL subgroup. Our findings would support more liberal EPT recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome.1-5,8,9 In this study, the SCA incidence rate was more than double the rate in the AF/AFL cohort (P < .001) and is commonly the initial presenting event in WPW syndrome.9 Even though the reported SCD incidence rate is low in WPW syndrome, our data demonstrated an increased association of death within the AF/AFL cohort. Physicians should consider early risk stratification and ablation to prevent potential recurrent malignant arrhythmia leading to death.1-5,8,9,12,19,20

Limitations

As a retrospective study and without access to the National Death Index, we were unable to determine the exact cause or events leading to death and instead utilized all-cause mortality data. Subsequently, our observations may only demonstrate association, rather than causality, between AF/AFL and death in patients with WPW syndrome. Additionally, we could not distinguish between AF and AFL as the arrhythmia leading to death. However, since overall survivability was the outcome of interest, our adjusted HR models were still able to demonstrate the increased association of the composite outcome and death within an AF/AFL cohort.

Although a large cohort was analyzed, due to the constraints of utilizing diagnostic codes to determine study outcomes, we could not distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, nor how they were managed prior to the outcome event. However, as recent literature demonstrates, updated predictors of malignant arrhythmia and decisions for early EPT are similar for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and should be driven by the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, rather than symptomatology;thus, our inability to discern this should have negligible consequence in determining when to perform risk stratification and ablation.1

MHS eligible patients have direct access to care; the generalizability of our data may not necessarily correspond to a community population with lower socioeconomic status (we did adjust for military sponsor rank which has been used as a proxy), reduced access to care, or uninsured individuals. However, the prevalence of WPW syndrome within our cohort was comparable to the general population, 0.4% vs 0.1%-0.3%, respectively.13,14,19 Similarly, the incidence of AF within our population was comparable to the general population, 15% vs 16%-26%, respectively.23 These similar data points suggest our results may apply beyond MHS patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with WPW syndrome and AF/AFL have a higher association with adverse cardiac outcomes and death. Despite previously reported low SCD incidence rates in this population, our study demonstrates the increased association of mortality in an AF/AFL cohort. The limitations of utilizing all-cause mortality data necessitate further investigation into the etiology behind the deaths in our study population. Since ventricular pre-excitation can predispose patients to AF and potentially lead to malignant arrhythmia and SCD, understanding the cause of mortality will allow physicians to determine the appropriate monitoring and intervention strategies to improve outcomes in this population. Our results suggest consideration for more aggressive EPT screening and ablation recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome may be warranted.

Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome is characterized by the presence of ≥ 1 accessory pathways and the development of both recurrent paroxysmal atrial fibrillation (AF) and supraventricular tachycardia that can lead to further malignant arrhythmias resulting in sudden cardiac death (SCD).1-7 Historically, incidental, ventricular pre-excitation on electrocardiogram has conferred a relatively low SCD risk in adults; however, newer WPW syndrome data suggest the endpoint may not be as benign as previously thought.7 The current literature has defined atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, rather than symptoms, as an independent risk factor for malignant arrhythmias. Still, long-term data detailing the association of AF with serious cardiac events and death in patients with WPW syndrome are still limited.1-7

While previous guidelines for the treatment of WPW syndrome only recommended routine electrophysiology testing (EPT) with liberal catheter ablation for symptomatic individuals, the 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guidelines now suggest its potential benefit for risk stratification in the asymptomatic population.8-12 Given the limited existing data, more long-term studies are needed to corroborate the latest EPT recommendations before routinely applying them in practice. Furthermore, since concomitant AF can lead to adverse cardiac outcomes in patients with WPW syndrome, additional data evaluating this association are also necessary. In this study, we aimed to determine the impact of atrial fibrillation and/or flutter (AF/AFL) on adverse cardiac outcomes and mortality in patients with WPW syndrome.

METHODS

This study used data from the Military Health System (MHS) Database Repository. The MHS is one of the largest health care systems in the country and includes information on about 10 million active duty and retired military service members and their families (51% male; 49% female).13,14 Data were fully anonymized and complied in accordance with federal and state laws, including the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996. The Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Study Design

This retrospective, observational cohort study identified MHS patients with WPW syndrome from January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2019. Patients were included if they had ≥ 2 International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes for WPW syndrome (ICD-9, 426.7; ICD-10, I45.6) on separate dates; were aged ≥ 18 years at index date; and had ≥ 1 year of continuous eligibility prior to the index date (enrollment gaps ≤ 30 days were considered continuous). Patients were then divided into 2 subgroups by the presence or absence of AF/AFL using diagnostic codes. Patients were excluded if they had evidence of an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator, permanent pacemaker or were missing age or sex data. Patients were followed from index date until the first occurrence of the outcome of interest, MHS disenrollment, or the end of the study period.

Cardiac composite outcomes comprised of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), ventricular fibrillation (VF), ventricular tachycardia and death, as well as death specifically, were the outcomes of interest and assessed after index date using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes. Death was defined as all-cause mortality. Time to event was calculated based on the date of the initial component from the composite outcome and date of death specifically for mortality. Those not experiencing an outcome were followed until MHS disenrollment or the end of the study period.

Various patient characteristics were assessed at index including age, sex, military sponsor (the patient’s active or retired duty member through which their dependent receives TRICARE benefits) rank and branch, geographic region, type of US Department of Defense beneficiary, and index year. Clinical characteristics were assessed over a 1-year baseline period prior to index date and included the number of cardiologist and clinical visits for WPW syndrome, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) scores calculated from diagnostic codes outlined in the Quan coding method, and preindex time.15 Comorbidities were assessed at baseline and defined as having ≥ 1 ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for a corresponding condition within 1 year prior to index.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics were assessed and descriptive statistics for categorical and continuous variables were presented accordingly. To assess bivariate association with exposure, χ2 tests were used to compare categorical variables, while t tests were used to compare continuous variables by exposure status. Incidence proportions and rates were reported for each outcome of interest. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to assess the bivariate association between exposure and study outcomes. Cox proportional hazard modeling was performed to estimate the association between AF/AFL and time to each of the outcomes. Multiple models were designed to assess cardiac and metabolic covariates, in addition to baseline characteristics. This included a base model adjusted for age, sex, military sponsor rank and branch, geographic region, and duty status.

Additional models adjusted for cardiac and metabolic confounders and CCI score. A comprehensive model included the base, cardiac, and metabolic covariates. Multicollinearity between covariates was assessed. Variables with a variance inflation factor > 4 or a tolerance level < 0.1 were added to the models. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% CIs of the association between AF/AFL and the study outcomes. Data were analyzed using SAS, version 9.4 for Windows.

RESULTS

From 2014 through 2019, 35,539 patients with WPW syndrome were identified in the MHS, 5291 had AF/AFL (14.9%); 19,961 were female (56.2%), the mean (SD) age was 62.9 (18.0) years, and 11,742 were aged ≥ 75 years (33.0%) (Table 1).

There were 4121 (11.6%), 322 (0.9%), and 848 (2.4%) patients with AF, AFL, and both arrhythmias, respectively. The mean (SD) number of cardiology visits was 3.9 (3.0). The mean (SD) baseline CCI score for the AF/AFL subgroup was 5.9 (3.5) vs 3.7 (2.2) for the non-AF/AFL subgroup (P < .001). The most prevalent comorbid conditions were hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes (P < .001) (Figure 1).

Composite Outcomes

In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.4 (2.0) years comprising 119,682 total person-years, the components of the composite outcome occurred 6506 times with an incidence rate of 5.44 per 100 person-years. Ventricular tachycardia was the most common event, occurring 3281 times with an incidence rate of 2.74 per 100 person-years. SCA and VF occurred 841 and 135 times with incidence rates of 0.70 and 0.11 per 100 person-years, respectively. Death was the initial event 2249 times with an incidence rate of 1.88 per 100 person-years. Figure 2 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of cardiac composite outcome by AF/AFL status.

The subgroup with AF/AFL comprised 17,412 total person-years and 1424 cardiac composite incidences compared with 102,270 person years and 5082 incidences in the no AF/AFL group (Table 2). Comparing AF/AFL vs no AF/AFL incidence rates were 8.18 vs 4.97 per 100 person-years, respectively (P < .001). SCA and VF occurred 233 and 38 times and respectively had incidence rates of 1.34 and 0.22 per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL group vs 0.59 and 0.09 per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). There were 549 deaths and a 3.15 per 100 person-years incidence rate in the AF/AFL group vs 1700 deaths and a 1.66 incidence rate in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001).

The HR for the composite outcome in the base model was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.26-1.42, P < .001) (Table 3). The association between AF/AFL and the composite outcome remained significant after adjusting for additional metabolic and cardiac covariates. The HRs for the metabolic and cardiac models were 1.30 (95% CI, 1.23-1.38, P < .001) and 1.11 (95% CI, 1.05-1.18, P < .001), respectively. After adjusting for the full model, the HR was 1.12 (95% CI, 1.05-1.19, P < .001).

Mortality

Over the 6-year study period, there was a lower survival probability for patients with AF/AFL. In the overall cohort, during a mean (SD) follow-up time of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 129,391 total person-years, there were 3130 (8.8%) deaths and an incidence rate of 2.42 per 100 person-years. Death occurred 786 times with a 4.09 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the AF/AFL vs 2344 deaths and a 2.13 incidence rate per 100 person-years in the no AF/AFL group (P < .001). In the non-AF/AFL subgroup, death occurred 2344 times during a mean (SD) follow-up of 3.7 (1.9) years comprising 110,151 total person-years. Figure 3 shows the Kaplan-Meier curve of mortality by AF/AFL status.

After adjusting for the base, metabolic and cardiac covariates, the HRs for mortality were 1.45 (95% CI, 1.33-1.57, P < .001), 1.40 (95% CI, 1.29-1.51, P < .001) and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.06-1.25, P = .001), respectively (Table 4). The HR after adjusting for the full model was 1.16 (95% CI, 1.07-1.26, P < .001).

DISCUSSION

In this large retrospective cohort study, patients with WPW syndrome and comorbid AF/AFL had a significantly higher association with the cardiac composite outcome and death during a 3-year follow-up period when compared with patients without AF/AFL. After adjusting for confounding variables, the AF/AFL subgroup maintained a 12% and 16% higher association with the composite outcome and mortality, respectively. There was minimal difference in confounding effects between demographic data and metabolic profiles, suggesting one may serve as a proxy for the other.

To our knowledge, this is the largest WPW syndrome cohort study evaluating cardiac outcomes and mortality to date. Although previous research has shown the relatively low and mostly anecdotal SCD incidence within this population,our results demonstrate a higher association of adverse cardiac outcomes and death in an AF/AFL subgroup.16-18 Notably, in this study the AF/AFL cohort was older and had higher CCI scores than their counterparts (P < .001), thus inferring an inherently greater degree of morbidity and 10-year mortality risk. Our study is also unique in that the mean patient age was significantly older than previously reported (63 vs 27 years), which may suggest a longer living history of both ventricular pre-excitation and the comorbidities outlined in Figure 1.19 Given these age discrepancies, it is possible that our overall study population was still relatively low risk and that not all reported deaths were necessarily related to WPW syndrome. Despite these assumptions, when comparing the WPW syndrome subgroups, we still found the AF/AFL cohort maintained a statistically significant higher association with the 2 study outcomes, even after adjusting for the greater presence of comorbidities. This suggests that the presence of AF/AFL may still portend a worse prognosis in patients with WPW syndrome.

Although the association of AF and development of VF in patients with WPW syndrome—due to rapid conduction over the accessory pathway(s)—was first reported > 40 years ago, there has still been few large, long-term data studies exploring mortality in this cohort.19-25 Furthermore, even though the current literature attributes the development of AF with the electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, as well as intrinsic atrial architecture and muscle vulnerability, there is still equivocal consensus regarding EPT screening and ablation indications for asymptomatic patients with WPW syndrome.26-28 Notably, Pappone and colleagues demonstrated the potential benefit of liberal ablation indications for asymptomatic patients, arguing that the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway—ie, short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period, inducibility of atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia triggering AF, and multiple accessory pathway—rather than symptoms, are independent predictors of developing malignant arrhythmia.1-5

These findings contradict those reported by Obeyesekere and colleagues, who concluded that the low SCD incidence rates in patients with WPW syndrome precluded routine invasive screening.19,28 They argued that Pappone and colleagues used malignant arrhythmia as a surrogate marker for death, and that the positive predictive value of a short accessory-pathway antegrade effective refractory period for developing malignant arrhythmia was lower than reported (15% vs 82%, respectively) and that its negative predictive value was 100%.1,19,28 Given these conflicting recommendations, we hope our data elucidates the higher association of adverse outcomes and support considerations for more intensive EPT indications in patients with WPW syndrome.

While our study does not report SCD incidence, it does provide robust and reliable mortality data that suggests a greater association of death within an AF/AFL subgroup. Our findings would support more liberal EPT recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome.1-5,8,9 In this study, the SCA incidence rate was more than double the rate in the AF/AFL cohort (P < .001) and is commonly the initial presenting event in WPW syndrome.9 Even though the reported SCD incidence rate is low in WPW syndrome, our data demonstrated an increased association of death within the AF/AFL cohort. Physicians should consider early risk stratification and ablation to prevent potential recurrent malignant arrhythmia leading to death.1-5,8,9,12,19,20

Limitations

As a retrospective study and without access to the National Death Index, we were unable to determine the exact cause or events leading to death and instead utilized all-cause mortality data. Subsequently, our observations may only demonstrate association, rather than causality, between AF/AFL and death in patients with WPW syndrome. Additionally, we could not distinguish between AF and AFL as the arrhythmia leading to death. However, since overall survivability was the outcome of interest, our adjusted HR models were still able to demonstrate the increased association of the composite outcome and death within an AF/AFL cohort.

Although a large cohort was analyzed, due to the constraints of utilizing diagnostic codes to determine study outcomes, we could not distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic patients, nor how they were managed prior to the outcome event. However, as recent literature demonstrates, updated predictors of malignant arrhythmia and decisions for early EPT are similar for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients and should be driven by the intrinsic electrophysiologic properties of the accessory pathway, rather than symptomatology;thus, our inability to discern this should have negligible consequence in determining when to perform risk stratification and ablation.1

MHS eligible patients have direct access to care; the generalizability of our data may not necessarily correspond to a community population with lower socioeconomic status (we did adjust for military sponsor rank which has been used as a proxy), reduced access to care, or uninsured individuals. However, the prevalence of WPW syndrome within our cohort was comparable to the general population, 0.4% vs 0.1%-0.3%, respectively.13,14,19 Similarly, the incidence of AF within our population was comparable to the general population, 15% vs 16%-26%, respectively.23 These similar data points suggest our results may apply beyond MHS patients.

CONCLUSIONS

Patients with WPW syndrome and AF/AFL have a higher association with adverse cardiac outcomes and death. Despite previously reported low SCD incidence rates in this population, our study demonstrates the increased association of mortality in an AF/AFL cohort. The limitations of utilizing all-cause mortality data necessitate further investigation into the etiology behind the deaths in our study population. Since ventricular pre-excitation can predispose patients to AF and potentially lead to malignant arrhythmia and SCD, understanding the cause of mortality will allow physicians to determine the appropriate monitoring and intervention strategies to improve outcomes in this population. Our results suggest consideration for more aggressive EPT screening and ablation recommendations in patients with WPW syndrome may be warranted.

1. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of WPW syndrome. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2015; 17 (Supplement A):A8-A11.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suv004

2. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Risk of malignant arrhythmias in initially symptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: results of a prospective long-term electrophysiological follow-up study. Circulation. 2012;125(5):661-668. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.065722

3. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Rosanio S, et al. Usefulness of invasive electrophysiologic testing to stratify the risk of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern: results from a large prospective long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(2):239-244. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02706-7

4. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014;130(10):811-819. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011154

5. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, et al. A randomized study of prophylactic catheter ablation in asymptomatic patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1803-1811. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035345

6. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. Asymptomatic ventricular preexcitation: a long-term prospective follow-up study of 293 adult patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(2):102-107. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.827550

7. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation a long-term prospective follow-up study of 184 asymptomatic children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(3):275-280. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.037

8. Al-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, et al. Risk Stratification for Arrhythmic Events in Patients With Asymptomatic Pre-Excitation: A Systematic Review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1624-1638. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.018

9. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias). Circulation. 2003;108(15):1871-1909.doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000091380.04100.84

10. Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF); PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm. 2012;9(6):1006-1024. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050

11. Cohen M, Triedman J. Guidelines for management of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation: brave new world or Pandora’s box?. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(2):187-189. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001528

12. Svendsen JH, Dagres N, Dobreanu D, et al. Current strategy for treatment of patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and asymptomatic preexcitation in Europe: European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace. 2013;15(5):750-753. doi:10.1093/europace/eut094

13. Gimbel RW, Pangaro L, Barbour G. America’s “undiscovered” laboratory for health services research. Med Care. 2010;48(8):751-756. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35be8

14. Dorrance KA, Ramchandani S, Neil N, Fisher H. Leveraging the military health system as a laboratory for health care reform. Mil Med. 2013;178(2):142-145. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-12-00168

15. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83

16. Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Behr ER, Sharma S, Sheppard M. Sudden Cardiac Death in Pre-Excitation and Wolff-Parkinson-White: Demographic and Clinical Features. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(12):1644-1645. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.023

17. Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993;87(3):866-873. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.3.866

18. Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. Am Heart J. 2001;142(3):530-536. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.117779

19. Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;125(19):2308-2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350

20. Waspe LE, Brodman R, Kim SG, Fisher JD. Susceptibility to atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: role of the accessory pathway. Am Heart J. 1986;112(6):1141-1152. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(86)90342-x

21. Pietersen AH, Andersen ED, Sandøe E. Atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(5):38A-43A. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)91076-g

22. Della Bella P, Brugada P, Talajic M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with an accessory pathway: importance of the conduction properties of the accessory pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(6):1352-1356. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80146-9

23. Fujimura O, Klein GJ, Yee R, Sharma AD. Mode of onset of atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how important is the accessory pathway?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(5):1082-1086. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(90)90244-j

24. Montoya PT, Brugada P, Smeets J, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(2):144-150. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059860

25. Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, Pritchett EL, Smith WM, Gallagher JJ. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(20):1080-1085. doi:10.1056/NEJM197911153012003

26. Centurion OA. Atrial Fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation. 2011;4(1):287. Published 2011 May 4. doi:10.4022/jafib.287

27. Song C, Guo Y, Zheng X, et al. Prognostic Significance and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation of Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(9):1546-1550. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.07.021

28. Obeyesekere M, Gula LJ, Skanes AC, Leong-Sit P, Klein GJ. Risk of sudden death in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how high is the risk?. Circulation. 2012;125(5):659-660. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.085159

1. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of WPW syndrome. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2015; 17 (Supplement A):A8-A11.doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suv004

2. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Risk of malignant arrhythmias in initially symptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: results of a prospective long-term electrophysiological follow-up study. Circulation. 2012;125(5):661-668. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.065722

3. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Rosanio S, et al. Usefulness of invasive electrophysiologic testing to stratify the risk of arrhythmic events in asymptomatic patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White pattern: results from a large prospective long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41(2):239-244. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02706-7

4. Pappone C, Vicedomini G, Manguso F, et al. Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in the era of catheter ablation: insights from a registry study of 2169 patients. Circulation. 2014;130(10):811-819. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011154

5. Pappone C, Santinelli V, Manguso F, et al. A randomized study of prophylactic catheter ablation in asymptomatic patients with the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(19):1803-1811. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa035345

6. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. Asymptomatic ventricular preexcitation: a long-term prospective follow-up study of 293 adult patients. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2009;2(2):102-107. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.108.827550

7. Santinelli V, Radinovic A, Manguso F, et al. The natural history of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation a long-term prospective follow-up study of 184 asymptomatic children. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(3):275-280. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2008.09.037

8. Al-Khatib SM, Arshad A, Balk EM, et al. Risk Stratification for Arrhythmic Events in Patients With Asymptomatic Pre-Excitation: A Systematic Review for the 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS Guideline for the Management of Adult Patients With Supraventricular Tachycardia: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1624-1638. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.09.018

9. Blomström-Lundqvist C, Scheinman MM, Aliot EM, et al. ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with supraventricular arrhythmias--executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Develop Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Supraventricular Arrhythmias). Circulation. 2003;108(15):1871-1909.doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000091380.04100.84

10. Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES); Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF); PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm. 2012;9(6):1006-1024. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2012.03.050

11. Cohen M, Triedman J. Guidelines for management of asymptomatic ventricular pre-excitation: brave new world or Pandora’s box?. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2014;7(2):187-189. doi:10.1161/CIRCEP.114.001528

12. Svendsen JH, Dagres N, Dobreanu D, et al. Current strategy for treatment of patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome and asymptomatic preexcitation in Europe: European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace. 2013;15(5):750-753. doi:10.1093/europace/eut094

13. Gimbel RW, Pangaro L, Barbour G. America’s “undiscovered” laboratory for health services research. Med Care. 2010;48(8):751-756. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181e35be8

14. Dorrance KA, Ramchandani S, Neil N, Fisher H. Leveraging the military health system as a laboratory for health care reform. Mil Med. 2013;178(2):142-145. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-12-00168

15. Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, et al. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43(11):1130-1139. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000182534.19832.83

16. Finocchiaro G, Papadakis M, Behr ER, Sharma S, Sheppard M. Sudden Cardiac Death in Pre-Excitation and Wolff-Parkinson-White: Demographic and Clinical Features. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(12):1644-1645. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2017.01.023

17. Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill SC, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953-1989. Circulation. 1993;87(3):866-873. doi:10.1161/01.cir.87.3.866

18. Fitzsimmons PJ, McWhirter PD, Peterson DW, Kruyer WB. The natural history of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome in 228 military aviators: a long-term follow-up of 22 years. Am Heart J. 2001;142(3):530-536. doi:10.1067/mhj.2001.117779

19. Obeyesekere MN, Leong-Sit P, Massel D, et al. Risk of arrhythmia and sudden death in patients with asymptomatic preexcitation: a meta-analysis. Circulation. 2012;125(19):2308-2315. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.055350

20. Waspe LE, Brodman R, Kim SG, Fisher JD. Susceptibility to atrial fibrillation and ventricular tachyarrhythmia in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: role of the accessory pathway. Am Heart J. 1986;112(6):1141-1152. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(86)90342-x

21. Pietersen AH, Andersen ED, Sandøe E. Atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1992;70(5):38A-43A. doi:10.1016/0002-9149(92)91076-g

22. Della Bella P, Brugada P, Talajic M, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with an accessory pathway: importance of the conduction properties of the accessory pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991;17(6):1352-1356. doi:10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80146-9

23. Fujimura O, Klein GJ, Yee R, Sharma AD. Mode of onset of atrial fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how important is the accessory pathway?. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15(5):1082-1086. doi:10.1016/0735-1097(90)90244-j

24. Montoya PT, Brugada P, Smeets J, et al. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. Eur Heart J. 1991;12(2):144-150. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059860

25. Klein GJ, Bashore TM, Sellers TD, Pritchett EL, Smith WM, Gallagher JJ. Ventricular fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1979;301(20):1080-1085. doi:10.1056/NEJM197911153012003

26. Centurion OA. Atrial Fibrillation in the Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome. J Atr Fibrillation. 2011;4(1):287. Published 2011 May 4. doi:10.4022/jafib.287

27. Song C, Guo Y, Zheng X, et al. Prognostic Significance and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation of Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome in Patients With Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2018;122(9):1546-1550. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.07.021

28. Obeyesekere M, Gula LJ, Skanes AC, Leong-Sit P, Klein GJ. Risk of sudden death in Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome: how high is the risk?. Circulation. 2012;125(5):659-660. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.085159

Reporting Coronary Artery Calcium on Low-Dose Computed Tomography Impacts Statin Management in a Lung Cancer Screening Population

Cigarette smoking is an independent risk factor for lung cancer and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).1-3 The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) demonstrated both lung cancer mortality reduction with the use of surveillance low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) and ASCVD as the most common cause of death among smokers.4,5 ASCVD remains the leading cause of death in the lung cancer screening (LCS) population.2,3 After publication of the NLST results, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) established LCS eligibility among smokers and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services approved payment for annual LDCT in this group.1,6,7

Recently LDCT has been proposed as an adjunct diagnostic tool for detecting coronary artery calcium (CAC), which is independently associated with ASCVD and mortality.8-13 CAC scores have been recommended by the 2019 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol treatment guidelines and shown to be cost-effective in guiding statin therapy for patients with borderline to intermediate ASCVD risk.14-16 While CAC is conventionally quantified using electrocardiogram (ECG)-gated CT, these scans are not routinely performed in clinical practice because preventive CAC screening is neither recommended by the USPSTF nor covered by most insurance providers.17,18 LDCT, conversely, is reimbursable and a well-validated ASCVD risk predictor.18,19

In this study, we aimed to determine the validity of LDCT in identifying CAC among the military LCS population and whether it would impact statin recommendations based on 10-year ASCVD risk.

Methods

Participants were recruited from a retrospective cohort of 563 Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries who received LCS with LDCT at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (NMCP) in Virginia between January 1, 2019, and December 31, 2020. The 2013 USPSTF LCS guidelines were followed as the 2021 guidelines had not been published before the start of the study; thus, eligible participants included adults aged 55 to 80 years with at least a 30-pack-year smoking history and currently smoked or had quit within 15 years from the date of study consent.6,7

Between November 2020 and May 2021, study investigators screened 287 patient records and recruited 190 participants by telephone, starting with individuals who had the most recent LDCT and working backward until reaching the predetermined 170 subjects who had undergone in-office consents before ECG-gated CT scans. Since LDCT was not obtained simultaneously with the ECG-gated CT, participants were required to complete their gated CT within 24 months of their last LDCT. Of the 190 subjects initially recruited, those who were ineligible for LCS (n = 4), had a history of angioplasty, stent, or bypass revascularization procedure (n = 4), did not complete their ECG-gated CT within the specified time frame (n = 8), or withdrew from the study (n = 4) were excluded. While gated CT scans were scored for CAC in the present time, LDCT (previously only read for general lung pathology) was not scored until after participant consent. Patients were peripherally followed, via health record reviews, for 3 months after their gated CT to document any additional imaging ordered by their primary care practitioners. The study was approved by the NMCP Institutional Review Board.

Coronary Artery Calcification Scoring

We performed CT scans using Siemens SOMATOM Flash, a second-generation dual-source scanner; and GE LightSpeed VCT, a single-source, 64-slice scanner. A step-and-shoot prospective trigger technique was used, and contiguous axial images were reconstructed at 2.5-mm or 3-mm intervals for CAC quantification using the Agatston method.20 ECG-gated CT scans were electrocardiographically triggered at mid-diastole (70% of the R-R interval). Radiation dose reduction techniques involved adjustments of the mA according to body mass index and iterative reconstruction. LDCT scans were performed without ECG gating. We reconstructed contiguous axial images at 1-mm intervals for evaluation of the lung parenchyma. Similar dose-reduction techniques were used, to limit radiation exposure for each LDCT scan to < 1.5 mSv, per established guidelines.21 CAC on LDCT was also scored using the Agatston method. CAC was scored on the 2 scan types by different blinded reviewers.

Covariates

We reviewed outpatient health records to obtain participants’ age, sex, medical history, statin use, smoking status (current or former), and pack-years. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes within medical encounters were used to document prevalent hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes mellitus. Participants’ most recent low-density lipoprotein value (within 24 months of ECG-gated CT) was recorded and 10-year ASCVD risk scores were calculated using the pooled cohorts equation.

Statistical Analysis

A power analysis performed before study initiation determined that a prospective sample size of 170 would be sufficient to provide strength of correlation between CAC scores calculated from ECG-gated CT and LDCT and achieve a statistical power of at least 80%. The Wilcoxon rank sum and Fisher exact tests were used to evaluate differences in continuous and categorical CAC scores, respectively. Given skewed distributions, Spearman rank correlations and Kendall W coefficient of concordance were respectively used to evaluate correlation and concordance of CAC scores between the 2 scan types. κ statistics were used to rate agreement between categorical CAC scores. Bland-Altman analysis was performed to determine the bias and limits of agreement between ECG-gated CT and LDCT.22 For categorical CAC score analysis, participants were categorized into 5 groups according to standard Agatston score cut-off points. We defined the 5 categories of CAC for both scan types based on previous analysis from Rumberger and colleagues: CAC = 0 (absent), CAC = 1-10 (minimal), CAC = 11-100 (mild), CAC = 101-400 (moderate), CAC > 400 (severe).23 Of note, LDCT reports at NMCP include a visual CAC score using these qualitative descriptors that were available to LDCT reviewers. Analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.4 and Microsoft Excel; P values < .05 were considered statistically significant.

Results