User login

Community Outreach Benefits Dermatology Residents and Their Patients

The sun often is rising in the rearview mirror as I travel with the University of New Mexico dermatology team from Albuquerque to our satellite clinic in Gallup, New Mexico. This twice-monthly trip—with a group usually comprising an attending physician, residents, and medical students—provides an invaluable opportunity for me to take part in delivering care to a majority Native American population and connects our institution and its trainees to the state’s rural and indigenous cultures and communities.

Community outreach is an important initiative for many dermatology residency training programs. Engaging with the community outside the clinic setting allows residents to hone their clinical skills, interact with and meet new people, and help to improve access to health care, especially for members of underserved populations.

Limited access to health care remains a pressing issue in the United States, especially for underserved and rural communities. There currently is no standardized way to measure access to care, but multiple contributing factors have been identified, including but not limited to patient wait times and throughput, provider turnover, ratio of dermatologists to patient population, insurance type, and patient outcomes.1 Fortunately, there are many ways for dermatology residents to get involved and improve access to dermatologic services in their communities, including skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology.

Skin Cancer Screenings

More than 40% of community outreach initiatives offered by dermatology residency programs are related to skin cancer screening and prevention.2 The American Academy of Dermatology’s free skin cancer check program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/spot) offers a way to participate in or even host a skin cancer screening in your community. Since 1985, this program has identified nearly 300,000 suspicious lesions and more than 30,000 suspected melanomas. Resources for setting up a skin cancer screening in your community are available on the program’s website. Residents may take this opportunity to teach medical students how to perform full-body skin examinations and/or practice making independent decisions as the supervisor for medical trainees. Skin cancer screening events not only expand access to care in underserved communities but also help residents feel more connected to the local community, especially if they have moved to a new location for their residency training.

Free Clinics

Engaging in educational opportunities offered through residency programs is another way to participate in community outreach. In particular, many programs are affiliated with a School of Medicine within their institution that allows residents to spearhead volunteer opportunities such as working at a free clinic. In fact, more than 30% of initiatives offered at dermatology residency programs are free general dermatology clinics.2 Residents are in the unique position of being both learners themselves as well as educators to trainees.3 As part of our role, we can provide crucial specialty care to the community by working in concert with medical students and while also familiarizing ourselves with treating populations that we may not reach in our daily clinical work. For example, by participating in free clinics, we can provide care to vulnerable populations who typically may have financial or time barriers that prevent them from seeking care at the institution-associated clinic, including individuals experiencing homelessness, patients who are uninsured, and individuals who cannot take time off work to pursue medical care. Our presence in the community helps to reduce barriers to specialty care, particularly in the field of dermatology where the access shortage in the context of rising skin cancer rates prompts public health concerns.4

Teledermatology

Teledermatology became a way to extend our reach in the community more than ever before during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in audio, visual, and data telecommunication have been particularly helpful in dermatology, a specialty that relies heavily on visual cues for diagnosis. Synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid teledermatology services implemented during the pandemic have gained favor among patients and dermatologists and are still applied in current practice.5,6

For example, in the state of New Mexico (where there is a severe shortage of board-certified dermatologists to care for the state’s population), teledermatology has allowed rural providers of all specialties to consult University of New Mexico dermatologists by sending clinical photographs along with patient information and history via secure messaging. Instead of having the patient travel hundreds of miles to see the nearest dermatologist for their skin condition or endure long wait times to get in to see a specialist, primary providers now can initiate treatment or work-up for their patient’s skin issue in a timely manner with the use of teledermatology to consult specialists.

Teledermatology has demonstrated cost-effectiveness, accuracy, and efficiency in conveniently expanding access to care. It offers patients and dermatologists flexibility in receiving and delivering health care, respectively.7 As residents, learning how to navigate this technologic frontier in health care delivery is imperative, as it will remain a prevalent tool in the future care of our communities, particularly in underserved areas.

Final Thoughts

Through community outreach initiatives, dermatology residents have an opportunity not only to enrich our education but also to connect with and become closer to our patients. Skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology have provided ways to reach more communities and remain important aspects of dermatology residency.

- Patel B, Blalock TW. Defining “access to care” for dermatology at academic medical institutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:627-628. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.014

- Fritsche M, Maglakelidze N, Zaenglein A, et al. Community outreach initiatives in dermatology: cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2693-2695. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02629-y

- Chiu LW. Teaching tips for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;113:E17-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.1046

- Duniphin DD. Limited access to dermatology specialty care: barriers and teledermatology. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023031. doi:10.5826/dpc.1301a31

- Ibrahim AE, Magdy M, Khalaf EM, et al. Teledermatology in the time of COVID-19. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e15000. doi:10.1111/ijcp.15000

- Farr MA, Duvic M, Joshi TP. Teledermatology during COVID-19: an updated review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:467-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00601-y

- Lipner SR. Optimizing patient care with teledermatology: improving access, efficiency, and satisfaction. Cutis. 2024;114:63-64. doi:10.12788/cutis.1073

The sun often is rising in the rearview mirror as I travel with the University of New Mexico dermatology team from Albuquerque to our satellite clinic in Gallup, New Mexico. This twice-monthly trip—with a group usually comprising an attending physician, residents, and medical students—provides an invaluable opportunity for me to take part in delivering care to a majority Native American population and connects our institution and its trainees to the state’s rural and indigenous cultures and communities.

Community outreach is an important initiative for many dermatology residency training programs. Engaging with the community outside the clinic setting allows residents to hone their clinical skills, interact with and meet new people, and help to improve access to health care, especially for members of underserved populations.

Limited access to health care remains a pressing issue in the United States, especially for underserved and rural communities. There currently is no standardized way to measure access to care, but multiple contributing factors have been identified, including but not limited to patient wait times and throughput, provider turnover, ratio of dermatologists to patient population, insurance type, and patient outcomes.1 Fortunately, there are many ways for dermatology residents to get involved and improve access to dermatologic services in their communities, including skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology.

Skin Cancer Screenings

More than 40% of community outreach initiatives offered by dermatology residency programs are related to skin cancer screening and prevention.2 The American Academy of Dermatology’s free skin cancer check program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/spot) offers a way to participate in or even host a skin cancer screening in your community. Since 1985, this program has identified nearly 300,000 suspicious lesions and more than 30,000 suspected melanomas. Resources for setting up a skin cancer screening in your community are available on the program’s website. Residents may take this opportunity to teach medical students how to perform full-body skin examinations and/or practice making independent decisions as the supervisor for medical trainees. Skin cancer screening events not only expand access to care in underserved communities but also help residents feel more connected to the local community, especially if they have moved to a new location for their residency training.

Free Clinics

Engaging in educational opportunities offered through residency programs is another way to participate in community outreach. In particular, many programs are affiliated with a School of Medicine within their institution that allows residents to spearhead volunteer opportunities such as working at a free clinic. In fact, more than 30% of initiatives offered at dermatology residency programs are free general dermatology clinics.2 Residents are in the unique position of being both learners themselves as well as educators to trainees.3 As part of our role, we can provide crucial specialty care to the community by working in concert with medical students and while also familiarizing ourselves with treating populations that we may not reach in our daily clinical work. For example, by participating in free clinics, we can provide care to vulnerable populations who typically may have financial or time barriers that prevent them from seeking care at the institution-associated clinic, including individuals experiencing homelessness, patients who are uninsured, and individuals who cannot take time off work to pursue medical care. Our presence in the community helps to reduce barriers to specialty care, particularly in the field of dermatology where the access shortage in the context of rising skin cancer rates prompts public health concerns.4

Teledermatology

Teledermatology became a way to extend our reach in the community more than ever before during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in audio, visual, and data telecommunication have been particularly helpful in dermatology, a specialty that relies heavily on visual cues for diagnosis. Synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid teledermatology services implemented during the pandemic have gained favor among patients and dermatologists and are still applied in current practice.5,6

For example, in the state of New Mexico (where there is a severe shortage of board-certified dermatologists to care for the state’s population), teledermatology has allowed rural providers of all specialties to consult University of New Mexico dermatologists by sending clinical photographs along with patient information and history via secure messaging. Instead of having the patient travel hundreds of miles to see the nearest dermatologist for their skin condition or endure long wait times to get in to see a specialist, primary providers now can initiate treatment or work-up for their patient’s skin issue in a timely manner with the use of teledermatology to consult specialists.

Teledermatology has demonstrated cost-effectiveness, accuracy, and efficiency in conveniently expanding access to care. It offers patients and dermatologists flexibility in receiving and delivering health care, respectively.7 As residents, learning how to navigate this technologic frontier in health care delivery is imperative, as it will remain a prevalent tool in the future care of our communities, particularly in underserved areas.

Final Thoughts

Through community outreach initiatives, dermatology residents have an opportunity not only to enrich our education but also to connect with and become closer to our patients. Skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology have provided ways to reach more communities and remain important aspects of dermatology residency.

The sun often is rising in the rearview mirror as I travel with the University of New Mexico dermatology team from Albuquerque to our satellite clinic in Gallup, New Mexico. This twice-monthly trip—with a group usually comprising an attending physician, residents, and medical students—provides an invaluable opportunity for me to take part in delivering care to a majority Native American population and connects our institution and its trainees to the state’s rural and indigenous cultures and communities.

Community outreach is an important initiative for many dermatology residency training programs. Engaging with the community outside the clinic setting allows residents to hone their clinical skills, interact with and meet new people, and help to improve access to health care, especially for members of underserved populations.

Limited access to health care remains a pressing issue in the United States, especially for underserved and rural communities. There currently is no standardized way to measure access to care, but multiple contributing factors have been identified, including but not limited to patient wait times and throughput, provider turnover, ratio of dermatologists to patient population, insurance type, and patient outcomes.1 Fortunately, there are many ways for dermatology residents to get involved and improve access to dermatologic services in their communities, including skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology.

Skin Cancer Screenings

More than 40% of community outreach initiatives offered by dermatology residency programs are related to skin cancer screening and prevention.2 The American Academy of Dermatology’s free skin cancer check program (https://www.aad.org/member/career/volunteer/spot) offers a way to participate in or even host a skin cancer screening in your community. Since 1985, this program has identified nearly 300,000 suspicious lesions and more than 30,000 suspected melanomas. Resources for setting up a skin cancer screening in your community are available on the program’s website. Residents may take this opportunity to teach medical students how to perform full-body skin examinations and/or practice making independent decisions as the supervisor for medical trainees. Skin cancer screening events not only expand access to care in underserved communities but also help residents feel more connected to the local community, especially if they have moved to a new location for their residency training.

Free Clinics

Engaging in educational opportunities offered through residency programs is another way to participate in community outreach. In particular, many programs are affiliated with a School of Medicine within their institution that allows residents to spearhead volunteer opportunities such as working at a free clinic. In fact, more than 30% of initiatives offered at dermatology residency programs are free general dermatology clinics.2 Residents are in the unique position of being both learners themselves as well as educators to trainees.3 As part of our role, we can provide crucial specialty care to the community by working in concert with medical students and while also familiarizing ourselves with treating populations that we may not reach in our daily clinical work. For example, by participating in free clinics, we can provide care to vulnerable populations who typically may have financial or time barriers that prevent them from seeking care at the institution-associated clinic, including individuals experiencing homelessness, patients who are uninsured, and individuals who cannot take time off work to pursue medical care. Our presence in the community helps to reduce barriers to specialty care, particularly in the field of dermatology where the access shortage in the context of rising skin cancer rates prompts public health concerns.4

Teledermatology

Teledermatology became a way to extend our reach in the community more than ever before during the COVID-19 pandemic. Advances in audio, visual, and data telecommunication have been particularly helpful in dermatology, a specialty that relies heavily on visual cues for diagnosis. Synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid teledermatology services implemented during the pandemic have gained favor among patients and dermatologists and are still applied in current practice.5,6

For example, in the state of New Mexico (where there is a severe shortage of board-certified dermatologists to care for the state’s population), teledermatology has allowed rural providers of all specialties to consult University of New Mexico dermatologists by sending clinical photographs along with patient information and history via secure messaging. Instead of having the patient travel hundreds of miles to see the nearest dermatologist for their skin condition or endure long wait times to get in to see a specialist, primary providers now can initiate treatment or work-up for their patient’s skin issue in a timely manner with the use of teledermatology to consult specialists.

Teledermatology has demonstrated cost-effectiveness, accuracy, and efficiency in conveniently expanding access to care. It offers patients and dermatologists flexibility in receiving and delivering health care, respectively.7 As residents, learning how to navigate this technologic frontier in health care delivery is imperative, as it will remain a prevalent tool in the future care of our communities, particularly in underserved areas.

Final Thoughts

Through community outreach initiatives, dermatology residents have an opportunity not only to enrich our education but also to connect with and become closer to our patients. Skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology have provided ways to reach more communities and remain important aspects of dermatology residency.

- Patel B, Blalock TW. Defining “access to care” for dermatology at academic medical institutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:627-628. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.014

- Fritsche M, Maglakelidze N, Zaenglein A, et al. Community outreach initiatives in dermatology: cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2693-2695. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02629-y

- Chiu LW. Teaching tips for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;113:E17-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.1046

- Duniphin DD. Limited access to dermatology specialty care: barriers and teledermatology. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023031. doi:10.5826/dpc.1301a31

- Ibrahim AE, Magdy M, Khalaf EM, et al. Teledermatology in the time of COVID-19. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e15000. doi:10.1111/ijcp.15000

- Farr MA, Duvic M, Joshi TP. Teledermatology during COVID-19: an updated review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:467-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00601-y

- Lipner SR. Optimizing patient care with teledermatology: improving access, efficiency, and satisfaction. Cutis. 2024;114:63-64. doi:10.12788/cutis.1073

- Patel B, Blalock TW. Defining “access to care” for dermatology at academic medical institutions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:627-628. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2023.03.014

- Fritsche M, Maglakelidze N, Zaenglein A, et al. Community outreach initiatives in dermatology: cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2693-2695. doi:10.1007/s00403-023-02629-y

- Chiu LW. Teaching tips for dermatology residents. Cutis. 2024;113:E17-E19. doi:10.12788/cutis.1046

- Duniphin DD. Limited access to dermatology specialty care: barriers and teledermatology. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2023;13:E2023031. doi:10.5826/dpc.1301a31

- Ibrahim AE, Magdy M, Khalaf EM, et al. Teledermatology in the time of COVID-19. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75:e15000. doi:10.1111/ijcp.15000

- Farr MA, Duvic M, Joshi TP. Teledermatology during COVID-19: an updated review. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2021;22:467-475. doi:10.1007/s40257-021-00601-y

- Lipner SR. Optimizing patient care with teledermatology: improving access, efficiency, and satisfaction. Cutis. 2024;114:63-64. doi:10.12788/cutis.1073

Resident Pearls

- Outreach initiatives can help residents feel more connected to their community and expand access to care.

- Skin cancer screenings, free clinics, and teledermatology are a few ways residents may get involved in their local communities.

Teaching Tips for Dermatology Residents

Dermatology residents interact with trainees of various levels throughout the workday—from undergraduate or even high school students to postgraduate fellows. Depending on the institution’s training program, residents may have responsibilities to teach through lecture series such as Grand Rounds and didactics. Therefore, it is an integral part of resident training to become educators in addition to being learners; however, formal pedagogy education is rare in dermatology programs. 1,2 Herein, I discuss several techniques that residents can apply to their practice to cultivate ideal learning environments and outcomes for trainees.

Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Experiences

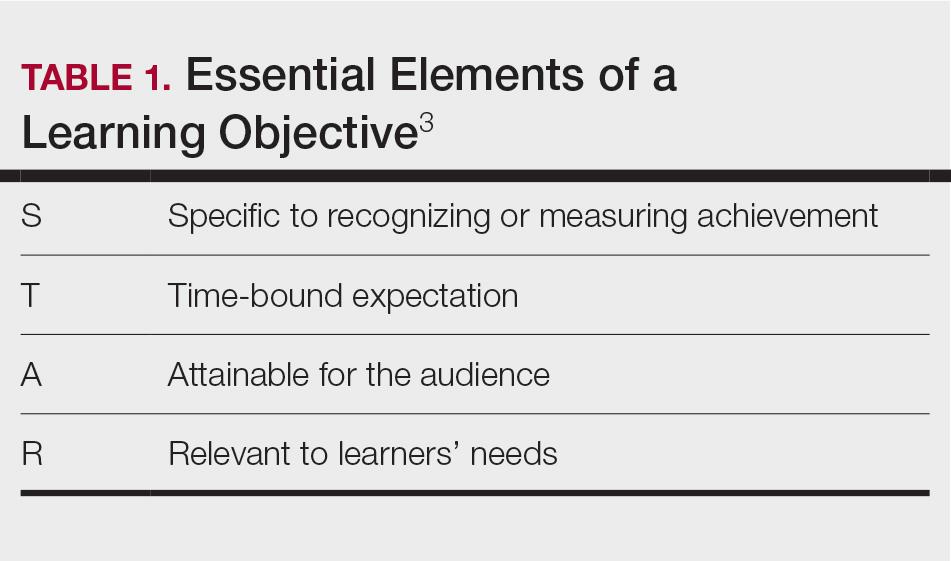

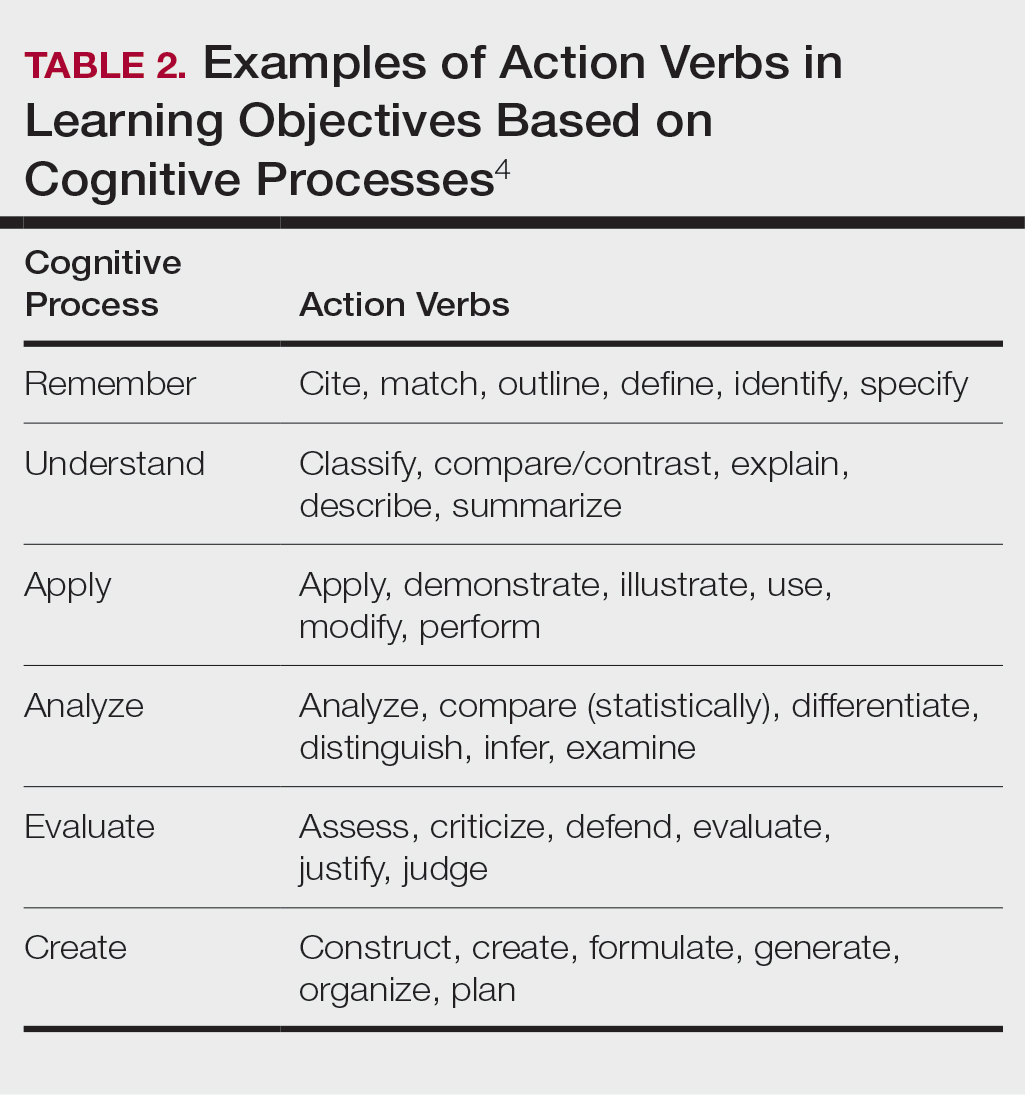

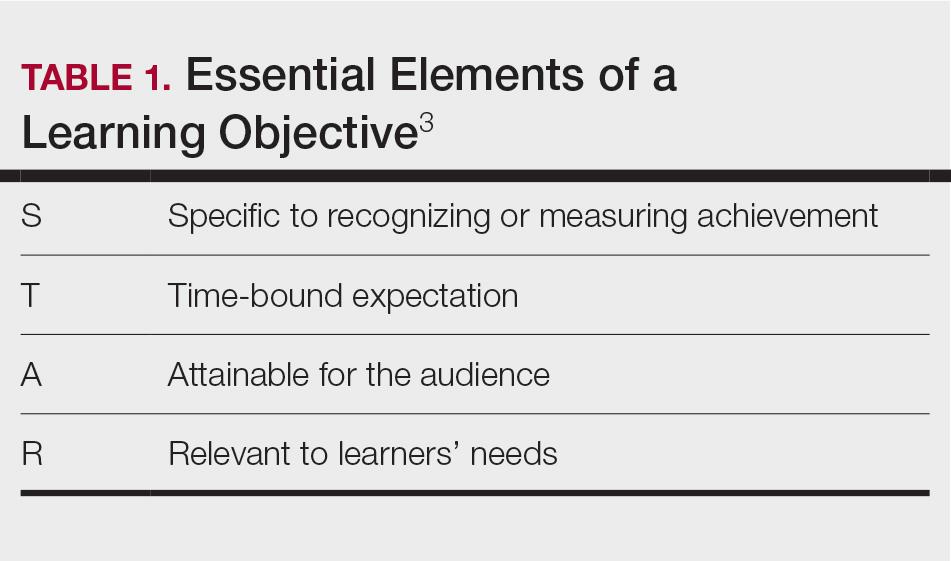

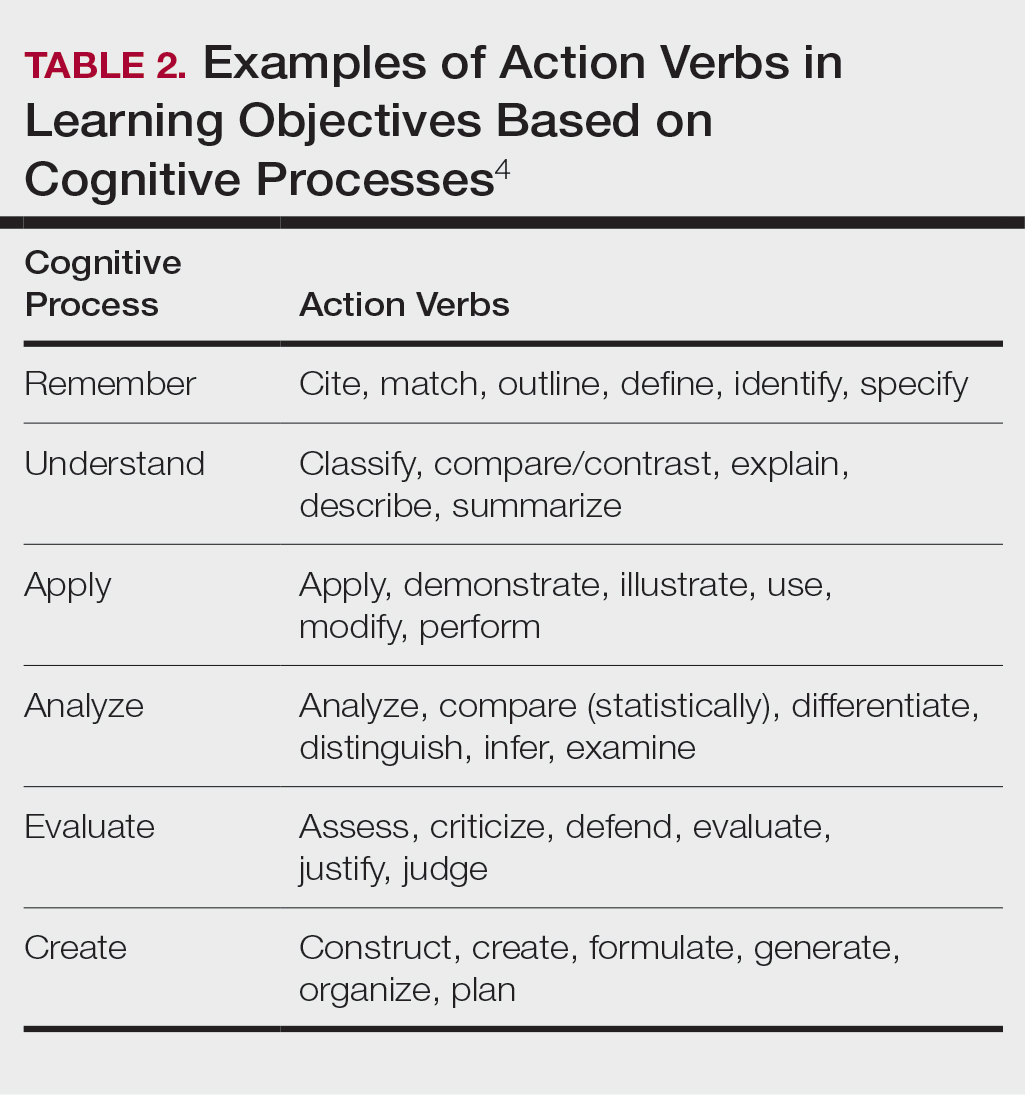

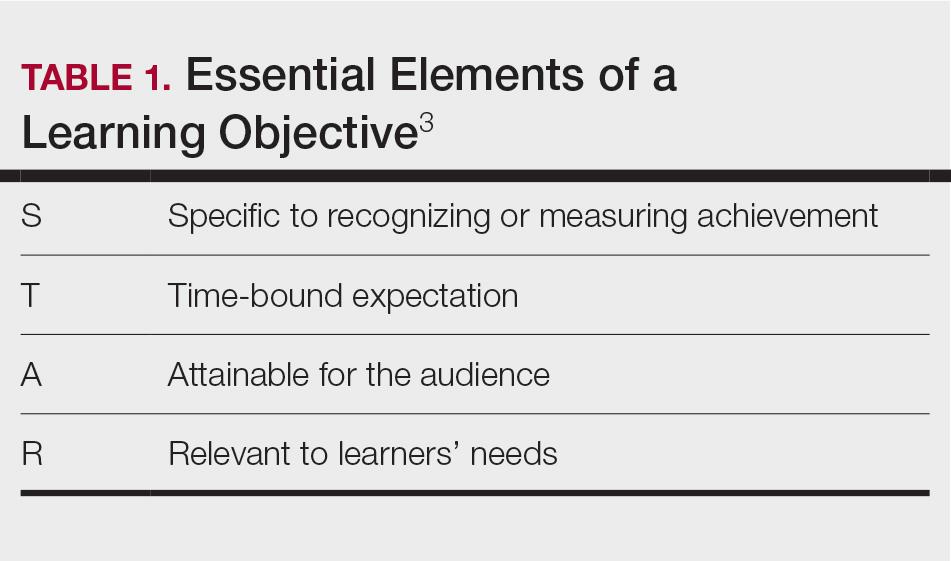

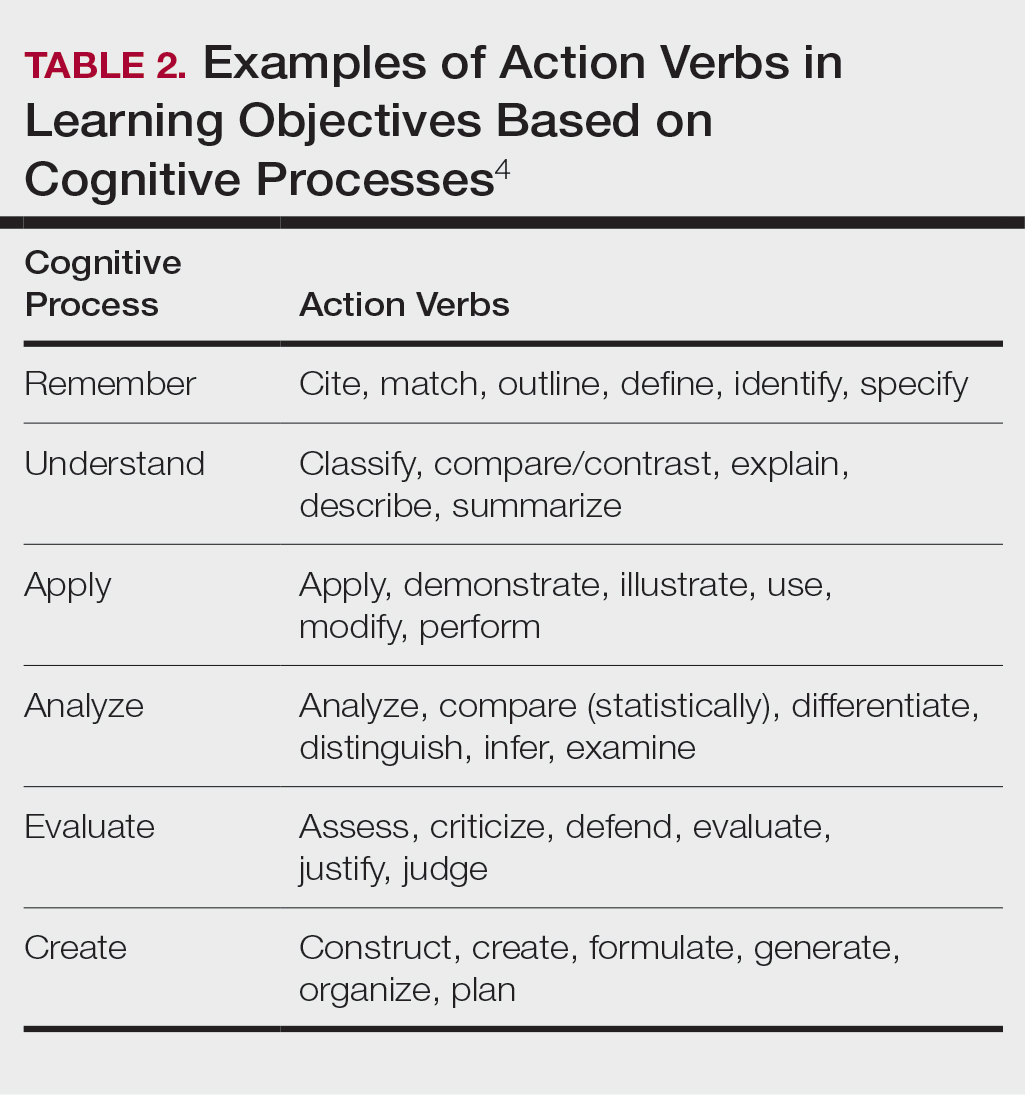

Planning to teach can be as important as teaching itself. Developing learning objectives can help to create effective teaching and learning experiences. Learning objectives should be specific, time bound, attainable, and learner centered (Table 1). It is recommended that residents aim for no more than 4 objectives per hour of learning.3 By creating clear learning objectives, residents can make connections between the content and any assessments. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives gives guidance on action verbs to use in writing learning objectives depending on the cognitive process being tested (Table 2).4

Creating a Safe Educational Environment

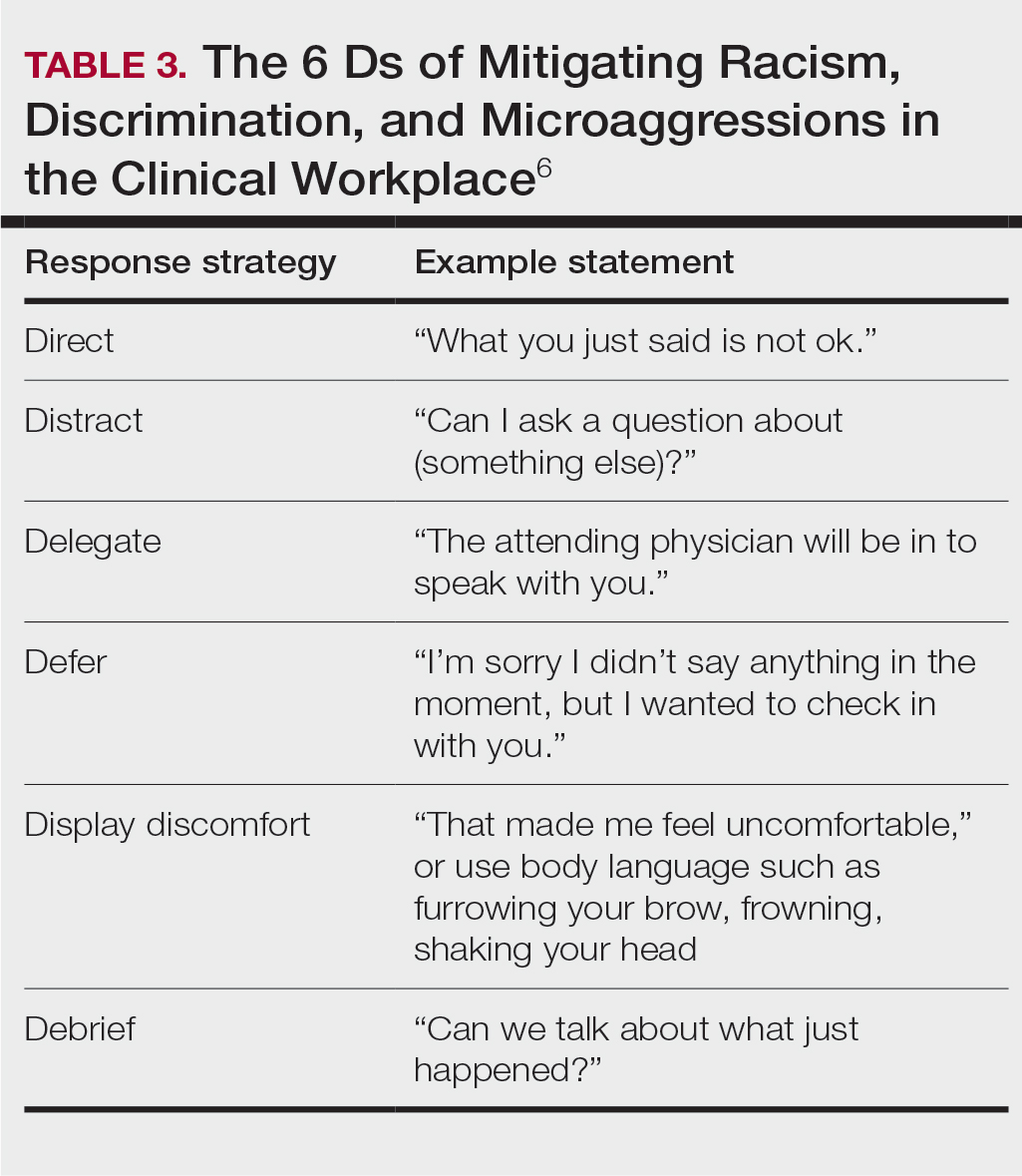

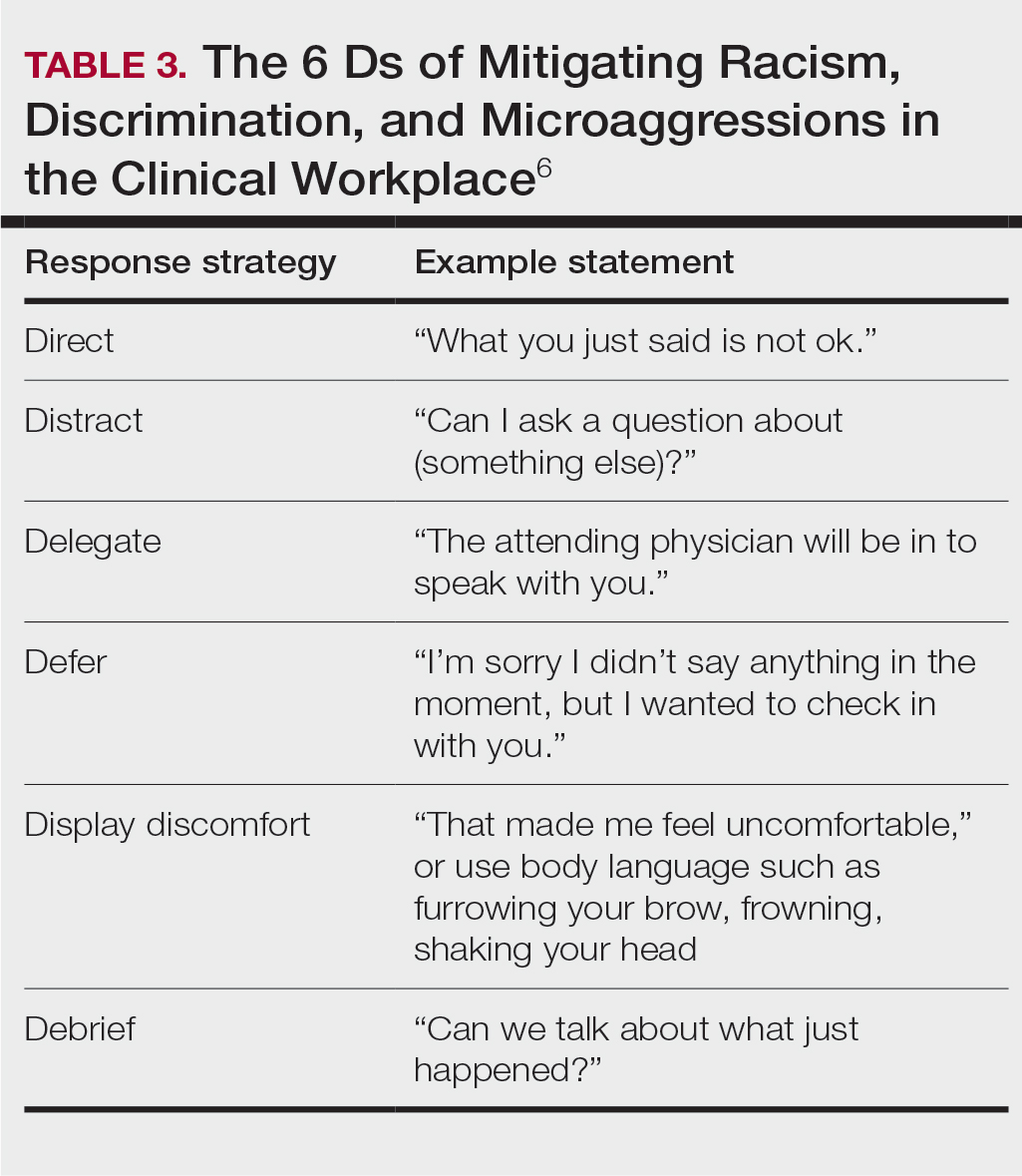

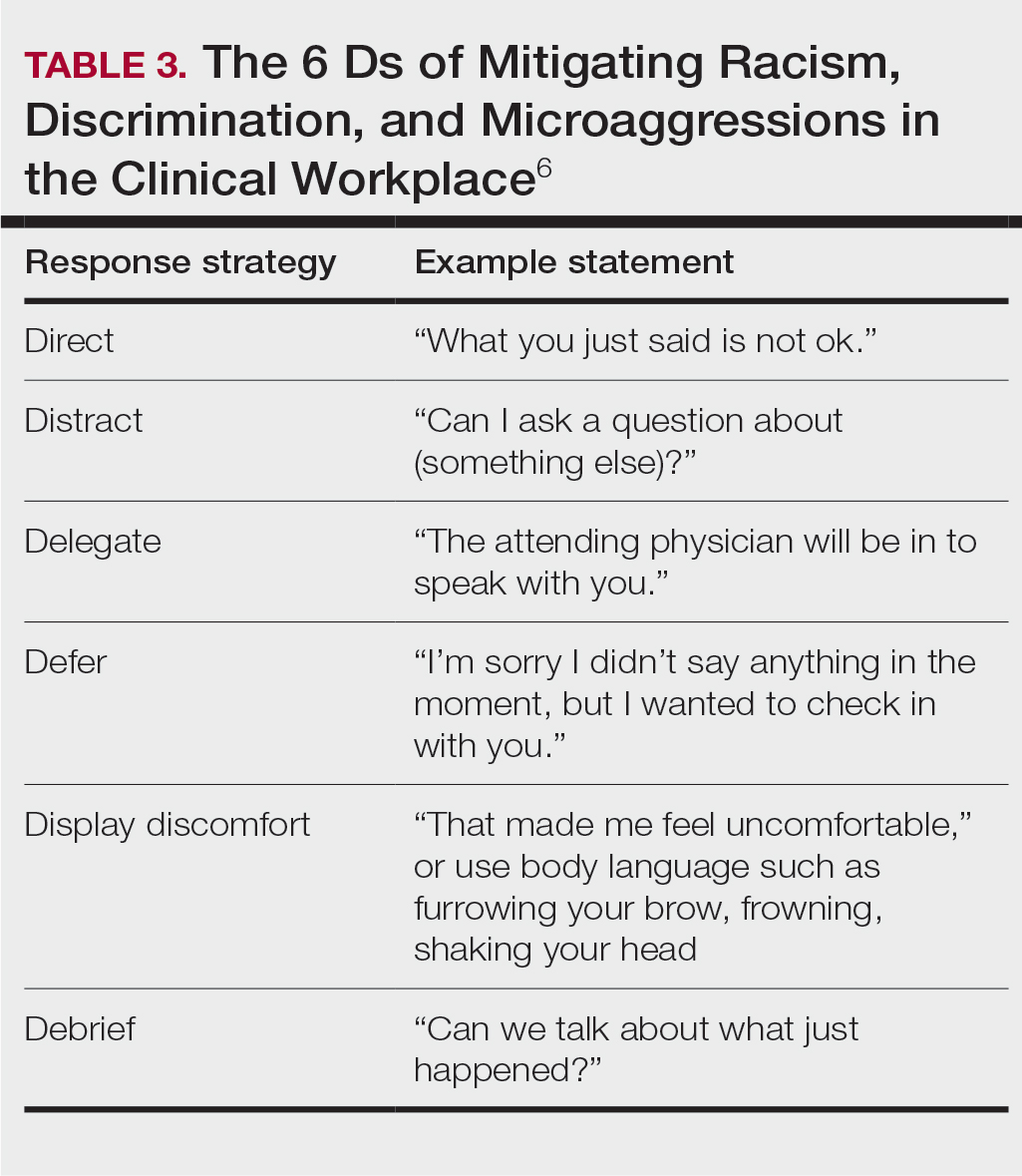

Psychological safety is the belief that a learning environment is a safe place in which to take risks.5 A clinical learning environment that is psychologically safe can support trainee well-being and learning. Cultivating a safe educational environment may include addressing microaggressions and bias in the clinical workplace. Table 3 provides examples of statements using the 6 Ds, which can be used to mitigate these issues.6 The first 4—direct, distract, delegate, and defer—represent ways to respond to racism, microaggressions, and bias, and the last 2—display discomfort and debrief—are responses that may be utilized in any problematic incident. Residents can play an important supportive role in scenarios where learners are faced with an incident that may not be regarded as psychologically safe. This is especially true if the learner is at a lower training level than the dermatology resident. We all play a role in creating a safe workplace for our teams.

Teaching in the Clinic and Hospital

There are multiple challenges to teaching in both inpatient and outpatient environments, including limited space and time; thus, more informal teaching methods are common. For example, in an outpatient dermatology clinic, the patient schedule can become a “table of contents” of potential teaching and learning opportunities. This technique is called the focused half day.3,7 By reviewing the clinic schedule, students can focus on a specific area of interest or theme throughout the course of the day.3

Priming and framing are other focused techniques that work well in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3,8,9 Priming means alerting the trainee to upcoming learning objective(s) and focusing their attention on what to observe or do during a shared visit with a patient. Framing—instructing learners to collect information that is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment—allows trainees to help move patient care forward while the resident attends to other patients.3

Modeling involves describing a thought process out loud for a learner3,10; for example, prior to starting a patient encounter, a dermatology resident may clearly state the goal of a patient conversation to the learner, describe their thought process about the topic, summarize the important points, and ask the learner if they have any questions about what was just said. Using this technique, learners may have a better understanding of why and how to go about conducting a patient encounter after the resident models one for them.

Effectively Integrating Visual Media and Presentations

Research supported by the cognitive load theory and cognitive theory of multimedia learning has led to the assertion-evidence approach for creating presentation slides that are built around messages, not topics, and messages are supported with visuals, not bullets.3,11,12 For example, slides should be constructed with 1- to 2-line assertion statements as titles and relevant illustrations or figures as supporting evidence to enhance visual memory.3

Written text on presentation slides often is redundant with spoken narration and also decreases learning because of cognitive load. Busy background colors and/or designs consume working memory and also can be detrimental to learning. Limiting these common distractors in a presentation makes for more effective delivery and retention of knowledge.3

Final Thoughts

There are multiple avenues for teaching as a resident and not all techniques may be applicable depending on the clinical or academic scenario. This column provides a starting point for residents to augment their pedagogical skills, particularly because formal teaching on pedagogy is lacking in medical education.

- Burgin S, Zhong CS, Rana J. A resident-as-teacher program increases dermatology residents’ knowledge and confidence in teaching techniques: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:651-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.008

- Burgin S, Homayounfar G, Newman LR, et al. Instruction in teaching and teaching opportunities for residents in US dermatology programs: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:703-706. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.043

- UNM School of Medicine Continuous Professional Learning. Residents as Educators. UNM School of Medicine; 2023.

- Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Book 1, Cognitive Domain. Longman; 1979.

- McClintock AH, Fainstad T, Blau K, et al. Psychological safety in medical education: a scoping review and synthesis of the literature. Med Teach. 2023;45:1290-1299. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2216863

- Ackerman-Barger K, Jacobs NN, Orozco R, et al. Addressing microaggressions in academic health: a workshop for inclusiveexcellence. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11103. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11103

- Taylor C, Lipsky MS, Bauer L. Focused teaching: facilitating early clinical experience in an office setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:547-548.

- Pan Z, Kosicki G. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit Commun. 1993;10:55-75. doi:10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- Price V, Tewksbury D, Powers E. Switching trains of thought: the impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Commun Res. 1997;24:481-506. doi:10.1177/009365097024005002

- Haston W. Teacher modeling as an effective teaching strategy. Music Educators J. 2007;93:26. doi:10.2307/4127130

- Alley M. Build your scientific talk on messages, not topics. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385725653

- Alley M. Support your presentation messages with visual evidence, not bullet lists. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385729603

Dermatology residents interact with trainees of various levels throughout the workday—from undergraduate or even high school students to postgraduate fellows. Depending on the institution’s training program, residents may have responsibilities to teach through lecture series such as Grand Rounds and didactics. Therefore, it is an integral part of resident training to become educators in addition to being learners; however, formal pedagogy education is rare in dermatology programs. 1,2 Herein, I discuss several techniques that residents can apply to their practice to cultivate ideal learning environments and outcomes for trainees.

Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Experiences

Planning to teach can be as important as teaching itself. Developing learning objectives can help to create effective teaching and learning experiences. Learning objectives should be specific, time bound, attainable, and learner centered (Table 1). It is recommended that residents aim for no more than 4 objectives per hour of learning.3 By creating clear learning objectives, residents can make connections between the content and any assessments. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives gives guidance on action verbs to use in writing learning objectives depending on the cognitive process being tested (Table 2).4

Creating a Safe Educational Environment

Psychological safety is the belief that a learning environment is a safe place in which to take risks.5 A clinical learning environment that is psychologically safe can support trainee well-being and learning. Cultivating a safe educational environment may include addressing microaggressions and bias in the clinical workplace. Table 3 provides examples of statements using the 6 Ds, which can be used to mitigate these issues.6 The first 4—direct, distract, delegate, and defer—represent ways to respond to racism, microaggressions, and bias, and the last 2—display discomfort and debrief—are responses that may be utilized in any problematic incident. Residents can play an important supportive role in scenarios where learners are faced with an incident that may not be regarded as psychologically safe. This is especially true if the learner is at a lower training level than the dermatology resident. We all play a role in creating a safe workplace for our teams.

Teaching in the Clinic and Hospital

There are multiple challenges to teaching in both inpatient and outpatient environments, including limited space and time; thus, more informal teaching methods are common. For example, in an outpatient dermatology clinic, the patient schedule can become a “table of contents” of potential teaching and learning opportunities. This technique is called the focused half day.3,7 By reviewing the clinic schedule, students can focus on a specific area of interest or theme throughout the course of the day.3

Priming and framing are other focused techniques that work well in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3,8,9 Priming means alerting the trainee to upcoming learning objective(s) and focusing their attention on what to observe or do during a shared visit with a patient. Framing—instructing learners to collect information that is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment—allows trainees to help move patient care forward while the resident attends to other patients.3

Modeling involves describing a thought process out loud for a learner3,10; for example, prior to starting a patient encounter, a dermatology resident may clearly state the goal of a patient conversation to the learner, describe their thought process about the topic, summarize the important points, and ask the learner if they have any questions about what was just said. Using this technique, learners may have a better understanding of why and how to go about conducting a patient encounter after the resident models one for them.

Effectively Integrating Visual Media and Presentations

Research supported by the cognitive load theory and cognitive theory of multimedia learning has led to the assertion-evidence approach for creating presentation slides that are built around messages, not topics, and messages are supported with visuals, not bullets.3,11,12 For example, slides should be constructed with 1- to 2-line assertion statements as titles and relevant illustrations or figures as supporting evidence to enhance visual memory.3

Written text on presentation slides often is redundant with spoken narration and also decreases learning because of cognitive load. Busy background colors and/or designs consume working memory and also can be detrimental to learning. Limiting these common distractors in a presentation makes for more effective delivery and retention of knowledge.3

Final Thoughts

There are multiple avenues for teaching as a resident and not all techniques may be applicable depending on the clinical or academic scenario. This column provides a starting point for residents to augment their pedagogical skills, particularly because formal teaching on pedagogy is lacking in medical education.

Dermatology residents interact with trainees of various levels throughout the workday—from undergraduate or even high school students to postgraduate fellows. Depending on the institution’s training program, residents may have responsibilities to teach through lecture series such as Grand Rounds and didactics. Therefore, it is an integral part of resident training to become educators in addition to being learners; however, formal pedagogy education is rare in dermatology programs. 1,2 Herein, I discuss several techniques that residents can apply to their practice to cultivate ideal learning environments and outcomes for trainees.

Creating Effective Teaching and Learning Experiences

Planning to teach can be as important as teaching itself. Developing learning objectives can help to create effective teaching and learning experiences. Learning objectives should be specific, time bound, attainable, and learner centered (Table 1). It is recommended that residents aim for no more than 4 objectives per hour of learning.3 By creating clear learning objectives, residents can make connections between the content and any assessments. Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives gives guidance on action verbs to use in writing learning objectives depending on the cognitive process being tested (Table 2).4

Creating a Safe Educational Environment

Psychological safety is the belief that a learning environment is a safe place in which to take risks.5 A clinical learning environment that is psychologically safe can support trainee well-being and learning. Cultivating a safe educational environment may include addressing microaggressions and bias in the clinical workplace. Table 3 provides examples of statements using the 6 Ds, which can be used to mitigate these issues.6 The first 4—direct, distract, delegate, and defer—represent ways to respond to racism, microaggressions, and bias, and the last 2—display discomfort and debrief—are responses that may be utilized in any problematic incident. Residents can play an important supportive role in scenarios where learners are faced with an incident that may not be regarded as psychologically safe. This is especially true if the learner is at a lower training level than the dermatology resident. We all play a role in creating a safe workplace for our teams.

Teaching in the Clinic and Hospital

There are multiple challenges to teaching in both inpatient and outpatient environments, including limited space and time; thus, more informal teaching methods are common. For example, in an outpatient dermatology clinic, the patient schedule can become a “table of contents” of potential teaching and learning opportunities. This technique is called the focused half day.3,7 By reviewing the clinic schedule, students can focus on a specific area of interest or theme throughout the course of the day.3

Priming and framing are other focused techniques that work well in both outpatient and inpatient settings.3,8,9 Priming means alerting the trainee to upcoming learning objective(s) and focusing their attention on what to observe or do during a shared visit with a patient. Framing—instructing learners to collect information that is relevant to the diagnosis and treatment—allows trainees to help move patient care forward while the resident attends to other patients.3

Modeling involves describing a thought process out loud for a learner3,10; for example, prior to starting a patient encounter, a dermatology resident may clearly state the goal of a patient conversation to the learner, describe their thought process about the topic, summarize the important points, and ask the learner if they have any questions about what was just said. Using this technique, learners may have a better understanding of why and how to go about conducting a patient encounter after the resident models one for them.

Effectively Integrating Visual Media and Presentations

Research supported by the cognitive load theory and cognitive theory of multimedia learning has led to the assertion-evidence approach for creating presentation slides that are built around messages, not topics, and messages are supported with visuals, not bullets.3,11,12 For example, slides should be constructed with 1- to 2-line assertion statements as titles and relevant illustrations or figures as supporting evidence to enhance visual memory.3

Written text on presentation slides often is redundant with spoken narration and also decreases learning because of cognitive load. Busy background colors and/or designs consume working memory and also can be detrimental to learning. Limiting these common distractors in a presentation makes for more effective delivery and retention of knowledge.3

Final Thoughts

There are multiple avenues for teaching as a resident and not all techniques may be applicable depending on the clinical or academic scenario. This column provides a starting point for residents to augment their pedagogical skills, particularly because formal teaching on pedagogy is lacking in medical education.

- Burgin S, Zhong CS, Rana J. A resident-as-teacher program increases dermatology residents’ knowledge and confidence in teaching techniques: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:651-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.008

- Burgin S, Homayounfar G, Newman LR, et al. Instruction in teaching and teaching opportunities for residents in US dermatology programs: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:703-706. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.043

- UNM School of Medicine Continuous Professional Learning. Residents as Educators. UNM School of Medicine; 2023.

- Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Book 1, Cognitive Domain. Longman; 1979.

- McClintock AH, Fainstad T, Blau K, et al. Psychological safety in medical education: a scoping review and synthesis of the literature. Med Teach. 2023;45:1290-1299. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2216863

- Ackerman-Barger K, Jacobs NN, Orozco R, et al. Addressing microaggressions in academic health: a workshop for inclusiveexcellence. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11103. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11103

- Taylor C, Lipsky MS, Bauer L. Focused teaching: facilitating early clinical experience in an office setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:547-548.

- Pan Z, Kosicki G. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit Commun. 1993;10:55-75. doi:10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- Price V, Tewksbury D, Powers E. Switching trains of thought: the impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Commun Res. 1997;24:481-506. doi:10.1177/009365097024005002

- Haston W. Teacher modeling as an effective teaching strategy. Music Educators J. 2007;93:26. doi:10.2307/4127130

- Alley M. Build your scientific talk on messages, not topics. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385725653

- Alley M. Support your presentation messages with visual evidence, not bullet lists. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385729603

- Burgin S, Zhong CS, Rana J. A resident-as-teacher program increases dermatology residents’ knowledge and confidence in teaching techniques: a pilot study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:651-653. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.12.008

- Burgin S, Homayounfar G, Newman LR, et al. Instruction in teaching and teaching opportunities for residents in US dermatology programs: results of a national survey. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:703-706. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.043

- UNM School of Medicine Continuous Professional Learning. Residents as Educators. UNM School of Medicine; 2023.

- Bloom BS. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Book 1, Cognitive Domain. Longman; 1979.

- McClintock AH, Fainstad T, Blau K, et al. Psychological safety in medical education: a scoping review and synthesis of the literature. Med Teach. 2023;45:1290-1299. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2023.2216863

- Ackerman-Barger K, Jacobs NN, Orozco R, et al. Addressing microaggressions in academic health: a workshop for inclusiveexcellence. MedEdPORTAL. 2021;17:11103. doi:10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11103

- Taylor C, Lipsky MS, Bauer L. Focused teaching: facilitating early clinical experience in an office setting. Fam Med. 1998;30:547-548.

- Pan Z, Kosicki G. Framing analysis: an approach to news discourse. Polit Commun. 1993;10:55-75. doi:10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

- Price V, Tewksbury D, Powers E. Switching trains of thought: the impact of news frames on readers’ cognitive responses. Commun Res. 1997;24:481-506. doi:10.1177/009365097024005002

- Haston W. Teacher modeling as an effective teaching strategy. Music Educators J. 2007;93:26. doi:10.2307/4127130

- Alley M. Build your scientific talk on messages, not topics. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385725653

- Alley M. Support your presentation messages with visual evidence, not bullet lists. Vimeo website. January 18, 2020. Accessed June 14, 2024. https://vimeo.com/385729603

Resident Pearls

- Emphasizing specific learning objectives, prioritizing safety in the learning environment, utilizing clinical teaching techniques, and using multimedia to present messages all contribute to effective dermatology teaching by residents.

How to Navigate Challenging Patient Encounters in Dermatology Residency

Dermatologists in training are exposed to many different clinical scenarios—from the quick 15-minute encounter to diagnose a case of atopic dermatitis to hours of digging through a medical record to identify a culprit medication in a hospitalized patient with a life-threatening cutaneous drug reaction. Amidst the day-to-day clinical work that we do, there inevitably are interactions we have with patients that are less than ideal. These challenging encounters—whether they be subtle microaggressions that unfortunately enter the workplace or blatant quarrels between providers and patients that leave both parties dissatisfied—are notable contributors to physician stress levels and can lead to burnout.1,2 However, there are positive lessons to be learned from these challenging patient encounters if we manage to withstand them. When we start to understand the factors contributing to difficult clinical encounters, we can begin to develop and apply effective communication tools to productively navigate these experiences.

Defining the Difficult Patient

In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease study revealed that skin disease is the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden worldwide.3 Based on this statistic, it is easy to see how some patients may experience frustration associated with their condition and subsequently displace their discontent on the physician. In one study, nearly 1 of every 6 (16.7%) outpatient encounters was considered difficult by physicians.4 Family medicine physicians defined the difficult patient as one who is violent, demanding, aggressive, and rude.5 Others in primary care specialties have considered difficult patients to have characteristics that include mental health problems, more than 5 somatic symptoms, and abrasive personalities.4,6

Situational and Physician-Centered Factors in Difficult Patient Encounters

In our medical system, the narrative often is focused on the patient, for better or worse—the patient was difficult, thereby making the encounter difficult. However, it is important to remember that difficult encounters can be attributed to several different factors, including those related to the physician, the clinical situation, or both. For example, dermatology residents juggle their clinical duties; academic work including studying, teaching, and/or research; and systemic and personal pressures at all times, whether they are cognizant of it or not. For better or worse, by virtue of being human, residents bring these factors with them to each clinical encounter. The delicate balance of these components can have a considerable impact on our delivery of good health care. This is particularly relevant in dermatology, where residents are subject to limited time during visits, work culture among clinic staff that is out of our control, and prominent complex social issues (for those of us practicing in medically underserved areas). Poor communication skills, underlying bias toward specific health conditions, limited knowledge as a trainee, and our own personal stressors also may play large roles in perceiving a clinical encounter as difficult during dermatology residency.7

Strategies to Mitigate Difficult Encounters

As a resident, if you make a statement that sparks a negative response from the patient, acknowledge their negative emotion, try to offer help, or rephrase the original statement to quickly dispel the tension. Validating a patient’s emotions and helping them embrace uncertainty can go a long way in the therapeutic relationship, especially in dermatology where so many of our diseases are chronic and without a definite cure.8 Additionally, it is important to apply strategies to redirect and de-escalate the situation during emotionally charged conversations, such as active listening, validating and empathizing with emotions, exploring alternative solutions, and providing closure to the conversation. Consensus recommendations for managing challenging encounters established by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2013 include setting boundaries or modifying schedules, as needed, to handle difficult encounters; employing empathetic listening skills and a nonjudgmental attitude to facilitate trust and adherence to treatment; and assessing for underlying psychological illnesses with referral for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Finally, the CALMER method—catalyst for change, alter thoughts to change feelings, listen and then make a diagnosis, make an agreement, education and follow-up, reach out and discuss feelings—is another approach that may be useful.7 In dermatology, this approach may not only dissipate unwanted tension but also make progress toward a therapeutic relationship. We cannot control the patient’s behavior in a visit, but we need to keep in mind that we are in control of our own reactions to said behavior.9 After first acknowledging this, we can then guide patients to take steps toward overcoming the issue. Within the time restrictions of a dermatology clinic visit, residents may use this approach to quickly feel more in control of a distressing situation and remain calm to better care for the patient.

Final Thoughts

Difficult patient encounters are impossible to avoid in any field of medicine, and dermatology is no exception. It will only benefit residents to recognize the multiple factors impacting a challenging encounter now and learn or enhance conflict resolution and communication skills to navigate these dissatisfying and uncomfortable situations, as they are inevitable in our careers.

- Bodner S. Stress management in the difficult patient encounter. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:579-603, ix-xx. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.02.012

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi:10.1111/joim.12752

- Seth D, Cheldize K, Brown D, et al. Global burden of skin disease: inequities and innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2017;6:204-210. doi:10.1007/s13671-017-0192-7

- An PGRabatin JSManwell LB, et al. Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:410-414. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.549

- Steinmetz D, Tabenkin H. The ‘difficult patient’ as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18:495-500. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.5.495

- Breuner CC, Moreno MA. Approaches to the difficult patient/parent encounter. Pediatrics. 2011;127:163-169. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0072

- Cannarella Lorenzetti R, Jacques CH, Donovan C, et al. Managing difficult encounters: understanding physician, patient, and situational factors. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:419-425.

- Bailey J, Martin SA, Bangs A. Managing difficult patient encounters. Am Fam Physician. 2023;108:494-500.

- Pomm HA, Shahady E, Pomm RM. The CALMER approach: teaching learners six steps to serenity when dealing with difficult patients. Fam Med. 2004;36:467-469.

Dermatologists in training are exposed to many different clinical scenarios—from the quick 15-minute encounter to diagnose a case of atopic dermatitis to hours of digging through a medical record to identify a culprit medication in a hospitalized patient with a life-threatening cutaneous drug reaction. Amidst the day-to-day clinical work that we do, there inevitably are interactions we have with patients that are less than ideal. These challenging encounters—whether they be subtle microaggressions that unfortunately enter the workplace or blatant quarrels between providers and patients that leave both parties dissatisfied—are notable contributors to physician stress levels and can lead to burnout.1,2 However, there are positive lessons to be learned from these challenging patient encounters if we manage to withstand them. When we start to understand the factors contributing to difficult clinical encounters, we can begin to develop and apply effective communication tools to productively navigate these experiences.

Defining the Difficult Patient

In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease study revealed that skin disease is the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden worldwide.3 Based on this statistic, it is easy to see how some patients may experience frustration associated with their condition and subsequently displace their discontent on the physician. In one study, nearly 1 of every 6 (16.7%) outpatient encounters was considered difficult by physicians.4 Family medicine physicians defined the difficult patient as one who is violent, demanding, aggressive, and rude.5 Others in primary care specialties have considered difficult patients to have characteristics that include mental health problems, more than 5 somatic symptoms, and abrasive personalities.4,6

Situational and Physician-Centered Factors in Difficult Patient Encounters

In our medical system, the narrative often is focused on the patient, for better or worse—the patient was difficult, thereby making the encounter difficult. However, it is important to remember that difficult encounters can be attributed to several different factors, including those related to the physician, the clinical situation, or both. For example, dermatology residents juggle their clinical duties; academic work including studying, teaching, and/or research; and systemic and personal pressures at all times, whether they are cognizant of it or not. For better or worse, by virtue of being human, residents bring these factors with them to each clinical encounter. The delicate balance of these components can have a considerable impact on our delivery of good health care. This is particularly relevant in dermatology, where residents are subject to limited time during visits, work culture among clinic staff that is out of our control, and prominent complex social issues (for those of us practicing in medically underserved areas). Poor communication skills, underlying bias toward specific health conditions, limited knowledge as a trainee, and our own personal stressors also may play large roles in perceiving a clinical encounter as difficult during dermatology residency.7

Strategies to Mitigate Difficult Encounters

As a resident, if you make a statement that sparks a negative response from the patient, acknowledge their negative emotion, try to offer help, or rephrase the original statement to quickly dispel the tension. Validating a patient’s emotions and helping them embrace uncertainty can go a long way in the therapeutic relationship, especially in dermatology where so many of our diseases are chronic and without a definite cure.8 Additionally, it is important to apply strategies to redirect and de-escalate the situation during emotionally charged conversations, such as active listening, validating and empathizing with emotions, exploring alternative solutions, and providing closure to the conversation. Consensus recommendations for managing challenging encounters established by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2013 include setting boundaries or modifying schedules, as needed, to handle difficult encounters; employing empathetic listening skills and a nonjudgmental attitude to facilitate trust and adherence to treatment; and assessing for underlying psychological illnesses with referral for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Finally, the CALMER method—catalyst for change, alter thoughts to change feelings, listen and then make a diagnosis, make an agreement, education and follow-up, reach out and discuss feelings—is another approach that may be useful.7 In dermatology, this approach may not only dissipate unwanted tension but also make progress toward a therapeutic relationship. We cannot control the patient’s behavior in a visit, but we need to keep in mind that we are in control of our own reactions to said behavior.9 After first acknowledging this, we can then guide patients to take steps toward overcoming the issue. Within the time restrictions of a dermatology clinic visit, residents may use this approach to quickly feel more in control of a distressing situation and remain calm to better care for the patient.

Final Thoughts

Difficult patient encounters are impossible to avoid in any field of medicine, and dermatology is no exception. It will only benefit residents to recognize the multiple factors impacting a challenging encounter now and learn or enhance conflict resolution and communication skills to navigate these dissatisfying and uncomfortable situations, as they are inevitable in our careers.

Dermatologists in training are exposed to many different clinical scenarios—from the quick 15-minute encounter to diagnose a case of atopic dermatitis to hours of digging through a medical record to identify a culprit medication in a hospitalized patient with a life-threatening cutaneous drug reaction. Amidst the day-to-day clinical work that we do, there inevitably are interactions we have with patients that are less than ideal. These challenging encounters—whether they be subtle microaggressions that unfortunately enter the workplace or blatant quarrels between providers and patients that leave both parties dissatisfied—are notable contributors to physician stress levels and can lead to burnout.1,2 However, there are positive lessons to be learned from these challenging patient encounters if we manage to withstand them. When we start to understand the factors contributing to difficult clinical encounters, we can begin to develop and apply effective communication tools to productively navigate these experiences.

Defining the Difficult Patient

In 2017, the Global Burden of Disease study revealed that skin disease is the fourth leading cause of nonfatal disease burden worldwide.3 Based on this statistic, it is easy to see how some patients may experience frustration associated with their condition and subsequently displace their discontent on the physician. In one study, nearly 1 of every 6 (16.7%) outpatient encounters was considered difficult by physicians.4 Family medicine physicians defined the difficult patient as one who is violent, demanding, aggressive, and rude.5 Others in primary care specialties have considered difficult patients to have characteristics that include mental health problems, more than 5 somatic symptoms, and abrasive personalities.4,6

Situational and Physician-Centered Factors in Difficult Patient Encounters

In our medical system, the narrative often is focused on the patient, for better or worse—the patient was difficult, thereby making the encounter difficult. However, it is important to remember that difficult encounters can be attributed to several different factors, including those related to the physician, the clinical situation, or both. For example, dermatology residents juggle their clinical duties; academic work including studying, teaching, and/or research; and systemic and personal pressures at all times, whether they are cognizant of it or not. For better or worse, by virtue of being human, residents bring these factors with them to each clinical encounter. The delicate balance of these components can have a considerable impact on our delivery of good health care. This is particularly relevant in dermatology, where residents are subject to limited time during visits, work culture among clinic staff that is out of our control, and prominent complex social issues (for those of us practicing in medically underserved areas). Poor communication skills, underlying bias toward specific health conditions, limited knowledge as a trainee, and our own personal stressors also may play large roles in perceiving a clinical encounter as difficult during dermatology residency.7

Strategies to Mitigate Difficult Encounters

As a resident, if you make a statement that sparks a negative response from the patient, acknowledge their negative emotion, try to offer help, or rephrase the original statement to quickly dispel the tension. Validating a patient’s emotions and helping them embrace uncertainty can go a long way in the therapeutic relationship, especially in dermatology where so many of our diseases are chronic and without a definite cure.8 Additionally, it is important to apply strategies to redirect and de-escalate the situation during emotionally charged conversations, such as active listening, validating and empathizing with emotions, exploring alternative solutions, and providing closure to the conversation. Consensus recommendations for managing challenging encounters established by the American Academy of Family Physicians in 2013 include setting boundaries or modifying schedules, as needed, to handle difficult encounters; employing empathetic listening skills and a nonjudgmental attitude to facilitate trust and adherence to treatment; and assessing for underlying psychological illnesses with referral for appropriate diagnosis and treatment. Finally, the CALMER method—catalyst for change, alter thoughts to change feelings, listen and then make a diagnosis, make an agreement, education and follow-up, reach out and discuss feelings—is another approach that may be useful.7 In dermatology, this approach may not only dissipate unwanted tension but also make progress toward a therapeutic relationship. We cannot control the patient’s behavior in a visit, but we need to keep in mind that we are in control of our own reactions to said behavior.9 After first acknowledging this, we can then guide patients to take steps toward overcoming the issue. Within the time restrictions of a dermatology clinic visit, residents may use this approach to quickly feel more in control of a distressing situation and remain calm to better care for the patient.

Final Thoughts

Difficult patient encounters are impossible to avoid in any field of medicine, and dermatology is no exception. It will only benefit residents to recognize the multiple factors impacting a challenging encounter now and learn or enhance conflict resolution and communication skills to navigate these dissatisfying and uncomfortable situations, as they are inevitable in our careers.

- Bodner S. Stress management in the difficult patient encounter. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:579-603, ix-xx. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.02.012

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi:10.1111/joim.12752

- Seth D, Cheldize K, Brown D, et al. Global burden of skin disease: inequities and innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2017;6:204-210. doi:10.1007/s13671-017-0192-7

- An PGRabatin JSManwell LB, et al. Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:410-414. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.549

- Steinmetz D, Tabenkin H. The ‘difficult patient’ as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18:495-500. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.5.495

- Breuner CC, Moreno MA. Approaches to the difficult patient/parent encounter. Pediatrics. 2011;127:163-169. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0072

- Cannarella Lorenzetti R, Jacques CH, Donovan C, et al. Managing difficult encounters: understanding physician, patient, and situational factors. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:419-425.

- Bailey J, Martin SA, Bangs A. Managing difficult patient encounters. Am Fam Physician. 2023;108:494-500.

- Pomm HA, Shahady E, Pomm RM. The CALMER approach: teaching learners six steps to serenity when dealing with difficult patients. Fam Med. 2004;36:467-469.

- Bodner S. Stress management in the difficult patient encounter. Dent Clin North Am. 2008;52:579-603, ix-xx. doi:10.1016/j.cden.2008.02.012

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi:10.1111/joim.12752

- Seth D, Cheldize K, Brown D, et al. Global burden of skin disease: inequities and innovations. Curr Dermatol Rep. 2017;6:204-210. doi:10.1007/s13671-017-0192-7

- An PGRabatin JSManwell LB, et al. Burden of difficult encounters in primary care: data from the minimizing error, maximizing outcomes study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:410-414. doi:10.1001/archinternmed.2008.549

- Steinmetz D, Tabenkin H. The ‘difficult patient’ as perceived by family physicians. Fam Pract. 2001;18:495-500. doi:10.1093/fampra/18.5.495

- Breuner CC, Moreno MA. Approaches to the difficult patient/parent encounter. Pediatrics. 2011;127:163-169. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0072

- Cannarella Lorenzetti R, Jacques CH, Donovan C, et al. Managing difficult encounters: understanding physician, patient, and situational factors. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87:419-425.

- Bailey J, Martin SA, Bangs A. Managing difficult patient encounters. Am Fam Physician. 2023;108:494-500.

- Pomm HA, Shahady E, Pomm RM. The CALMER approach: teaching learners six steps to serenity when dealing with difficult patients. Fam Med. 2004;36:467-469.

RESIDENT PEARLS

- Challenging patient encounters are inevitable in our work as dermatology residents. Both physician- and patient-related factors can contribute.

- Setting boundaries, active listening, and addressing emotions during and after the visit can help to mitigate challenging encounters.