User login

Intraoperative Radiofrequency Ablation for Osteoid Osteoma

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is one of the most common benign tumors of bone, representing roughly 10% of all benign bone-forming tumors and 5% of all primary bone tumors.1 The majority of cases occur in individuals under age 20 years and more frequently in males (2:1).2 These lesions tend to be cortically based and most often located about the hip and in the diaphysis of long bones. They typically are characterized radiographically by a nidus less than 2 cm in diameter surrounded by dense, reactive bone of variable thickness.

The classic presentation of OO is localized, dull, aching pain that is worse at night and that is relieved with use of salicylates or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3 The diagnosis is made by patient history and plain radiographs, often supported by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging for appropriate identification of the tumor nidus. Despite effective pain relief with NSAIDs as well as evidence suggesting that the natural history of these tumors is self-limited, most patients forgo medical management in favor of elective surgical treatment.4,5

Initially, treatment for OO focused on either symptom management or en bloc surgical resection of the tumor nidus. Several different minimally invasive therapies have since been developed, and good results reported.6-8 More recently, use of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has increased, as this method has demonstrated high efficacy and minimal morbidity.9-11 RFA for OO traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite, but advances in intraoperative imaging techniques now allow orthopedic oncologists to perform image-guided RFA in the operating room.

To our knowledge, there have been no reports documenting use of intraoperative CT for localization of OO and use of RFA in the treatment of this lesion. In this article, we report the results of a series of 28 patients with OO treated with intraoperative CT-guided RFA by a single surgeon. We also provide a brief description of this novel technique.

Materials and Methods

The protocol used was approved by our institutional review board. All patients and/or their legal guardians provided informed consent to participate in the study and were informed at the time consent was obtained that case-related data would be submitted for publication.

Patients

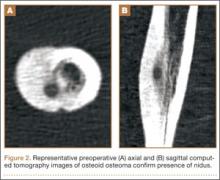

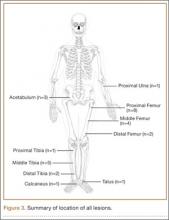

Between September 2004 and December 2008, 28 patients (19 males, 9 females) with OO underwent intraoperative percutaneous image-guided RFA at a university hospital. Mean age was 19.5 years, median age was 16 years (range, 7-54 years). Patients were referred for RFA if they had clinical and radiographic features of OO (Figures 1, 2) and wanted to forgo continued medical management. As we selected only patients with lesions that we thought were amenable to percutaneous RFA—lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper or lower extremity and selected flat bones—en bloc surgical resection was not offered to these patients. Lesions were located in the upper extremity (n = 1), lower extremity (n = 24), and pelvis (n = 3) (Figure 3). Twenty-seven procedures were performed for initial tumor treatment and 1 for recurrence after previous open excision. Two additional procedures were later performed on separate patients with recurrent symptoms after the index procedure. All procedures were performed by the senior author (DML).

Procedure

With each patient, all options were discussed, including continued medical management versus surgical treatment, and informed consent was obtained. All procedures were performed with the patient under general anesthesia in the operating room. RFA for an upper extremity lesion was performed with the patient in the supine position with the ipsilateral extremity draped over a hand table. The 2 procedures for lesions in the talus or calcaneus were performed with the patient in the supine position using a standard table with the bottom of the table flexed down 90° to allow the nonaffected leg to hang over the end of the table. The affected extremity in each case was then positioned in a well-padded leg holder to allow the foot and ankle to be draped free for 360° imaging.

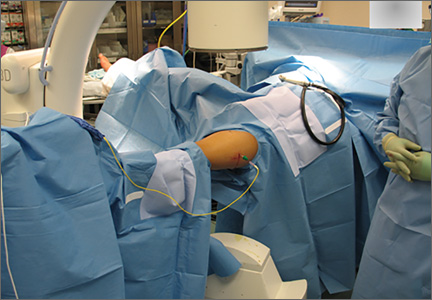

All other procedures for lower extremity diaphyseal or pelvic lesions were performed with a fracture table. After successful induction of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned supine on the table with the contralateral lower extremity abducted and externally rotated in a well-leg holder. The ipsilateral leg was held in the traction apparatus without traction applied and was prepared and draped accordingly (Figure 4). With use of the Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, Pennsylvania), a radiograph was taken of the affected area to identify the lesion. Local anesthetic was infiltrated into the surgical site down to the periosteum. A stab incision was made, and, with fluoroscopic guidance, a 0.062-mm Kirschner wire (K-wire) was placed into the lesion. Location within the tumor nidus was confirmed with biplanar fluoroscopic imaging. A Bonopty cannula (AprioMed, Uppsala, Sweden) was then passed over the K-wire. After the wire was removed, a 5-mm radiofrequency probe (Radionics, Burlington, Massachusetts) was placed through the cannula, and positioning within the nidus was confirmed with 3-dimensional (3-D) CT reconstructions in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes (Figure 5). A radiofrequency generator (Radionics) was used to heat the lesion at 93°C for 7 minutes. The probe and trocar were then removed. Steri-strips and a sterile dressing were used to cover the wound, and the patient was taken to the recovery area after extubation. All patients were discharged home the day of the procedure.

Follow-Up

We phoned all the patients to ask about symptom recurrence, outside treatment, and satisfaction with RFA and to obtain informed consent to participate in our study. Only 1 of the 28 patients could not be reached and was lost to follow-up. Mean follow-up at time of study completion was 31.1 months (range, 5.2-55.8 months).

The 27 patients were asked a series of questions about their treatment: Have you had any recurrence of symptoms following treatment for your OO? Have you received treatment elsewhere? Were you satisfied with your treatment? Would you have the procedure again if you had a recurrence of symptoms?

Primary success was defined as complete pain relief after initial RFA with no evidence of recurrence at time of final follow-up, and secondary success was defined as presence of recurrent symptoms after initial RFA with complete pain relief after a second procedure with no evidence of recurrence.

Results

All RFAs were technically successful with adequate localization of the tumor nidus and subsequent probe placement within the lesion. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. All 28 patients were discharged home the day of procedure. Twenty-six patients (92.8%) experienced complete pain relief after primary RFA, had no evidence of recurrence at final follow-up, and denied symptom recurrence at time of study completion.

The other 2 patients reported symptom recurrence after the index treatment (1 proximal femur lesion, 1 distal femur lesion). One of these patients did well initially but had a recurrence about 2 months after the primary RFA; a second RFA provided complete resolution of pain with no evidence of recurrence at time of study completion. In the other patient’s case, intermittent pain persisted for 2 weeks after the primary RFA, and evidence of recurrence was documented 3 months after surgery; a second RFA was performed shortly thereafter, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

At time of study completion, all 27 patients who had been contacted by phone denied seeking additional treatment elsewhere and stated they would have the procedure again if their symptoms ever recurred.

Discussion

Osteoid osteoma is one of the most common benign tumors of bone. Over the past 2 decades, percutaneous RFA, in comparison with open excision, has emerged as a safe and effective treatment option with minimal patient morbidity.9-11 RFA traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite. However, now orthopedic surgeons can obtain advanced intraoperative imaging beyond standard fluoroscopy. The Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm is an innovative intraoperative imaging device that functions as a standard fluoroscope but also generates 3-D reconstructions of surgical anatomy. The isocentric design and integrated motor unit allow the C-arm to move through a 190º arc while centering its beam directly on the area of interest. This data set is transferred to a computer workstation, where it is reformatted so that CT-quality images are generated in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. This acquisition process takes only minutes, and the multiplanar images produced may be simultaneously displayed and manipulated on the screen in real time.

One concern about this technology is the amount of radiation exposure for patients, surgeons, and operating room staff. The device measures only radiation time, and the amount of exposure during that time depends on the volume and density of the radiated body. We did not calculate the amount of exposure for this study. Mean exposure time was between 20 and 40 seconds, reflecting the number of attempts required to localize the lesion and the surgeon’s experience with the technique. Although the potential for increased exposure is a valid concern, previous studies using this technology have demonstrated that a similar average exposure time is equivalent to that of standard CT, and that use of the device, over conventional techniques, potentially can lead to decreased overall radiation exposure.12,13

This series demonstrated that OO can be safely and effectively treated with intraoperative percutaneous RFA by an orthopedic oncologist. Our success rate is very similar to rates reported in the radiology literature. Studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of this novel technique in comparison with what has been reported in that literature. Given these promising preliminary results, and the relative ease of use and minimal learning curve associated with this technology, all orthopedic oncologists should be able to offer this treatment for OO. Furthermore, this technique allows orthopedic oncologists to provide appropriate definitive treatment and care directly, rather than by referring patients to radiologists.

In the treatment of OO, we reserve RFA for lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper and lower extremities, as well as selected flat bones, such as those in the pelvis. Although percutaneous RFA of spinal lesions has been reported in the literature, we think these represent a relative contraindication for this technique; image resolution, in our opinion, is not high enough to justify risking injury to the nerves in the spinal canal, lateral recesses, and neural foramina. In addition, given the radiation exposure, we recommend caution when using this technique for a pelvic or proximal femoral lesion in a woman of childbearing age.

1. Gitelis S, Wilkins R, Conrad EU 2nd. Benign bone tumors. Instr Course Lect. 1996;45:425-424.

2. Schajowicz F. Bone forming tumors. In: Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions of Bone. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1994:36-62.

3. Frassica FJ, Waltrip RL, Sponseller PD, Ma LD, McCarthy EF Jr. Clinicopathologic features and treatment of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(3):559-574.

4. Golding JS. The natural history of osteoid osteoma; with a report of twenty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36(2):218-229.

5. Simm RJ. The natural history of osteoid osteoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1975;45(4):412-415.

6. Sans N, Galy-Fourcade D, Assoun J, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous resection and follow-up in 38 patients. Radiology. 1999;212(3):687-692.

7. Skjeldal S, Lilleås F, Follerås G, et al. Real time MRI-guided excision and cryo-treatment of osteoid osteoma in os ischii—a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(6):637-638.

8. Sanhaji L, Gharbaoui IS, Hassani RE, Chakir N, Jiddane M, Boukhrissi N. A new treatment of osteoid osteoma: percutaneous sclerosis with ethanol under scanner guidance [in French]. J Radiol. 1996;77(1):37-40.

9. Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Torriani M, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous treatment with radiofrequency energy. Radiology. 2003;229(1):171-175.

10. Cantwell CP, Obyrne J, Eustace S. Current trends in treatment of osteoid osteoma with an emphasis on radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(4):607-617.

11. Ruiz Santiago F, Castellano García Mdel M, Guzmán Álvarez L, Martínez Montes JL, Ruiz García M, Tristán Fernández JM. Percutaneous treatment of bone tumors by radiofrequency thermal ablation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):156-163.

12. Richter M, Geerling J, Zech S, Goesling T, Krettek C. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging with a motorized mobile C-Arm (SIREMOBIL ISO-C-3D) in foot and ankle trauma care: a preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(4):259-266.

13. Gebhard F, Kraus M, Schneider E, et al. Radiation dosage in orthopedics—a comparison of computer-assisted procedures [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2003;106(6):492-497.

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is one of the most common benign tumors of bone, representing roughly 10% of all benign bone-forming tumors and 5% of all primary bone tumors.1 The majority of cases occur in individuals under age 20 years and more frequently in males (2:1).2 These lesions tend to be cortically based and most often located about the hip and in the diaphysis of long bones. They typically are characterized radiographically by a nidus less than 2 cm in diameter surrounded by dense, reactive bone of variable thickness.

The classic presentation of OO is localized, dull, aching pain that is worse at night and that is relieved with use of salicylates or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3 The diagnosis is made by patient history and plain radiographs, often supported by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging for appropriate identification of the tumor nidus. Despite effective pain relief with NSAIDs as well as evidence suggesting that the natural history of these tumors is self-limited, most patients forgo medical management in favor of elective surgical treatment.4,5

Initially, treatment for OO focused on either symptom management or en bloc surgical resection of the tumor nidus. Several different minimally invasive therapies have since been developed, and good results reported.6-8 More recently, use of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has increased, as this method has demonstrated high efficacy and minimal morbidity.9-11 RFA for OO traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite, but advances in intraoperative imaging techniques now allow orthopedic oncologists to perform image-guided RFA in the operating room.

To our knowledge, there have been no reports documenting use of intraoperative CT for localization of OO and use of RFA in the treatment of this lesion. In this article, we report the results of a series of 28 patients with OO treated with intraoperative CT-guided RFA by a single surgeon. We also provide a brief description of this novel technique.

Materials and Methods

The protocol used was approved by our institutional review board. All patients and/or their legal guardians provided informed consent to participate in the study and were informed at the time consent was obtained that case-related data would be submitted for publication.

Patients

Between September 2004 and December 2008, 28 patients (19 males, 9 females) with OO underwent intraoperative percutaneous image-guided RFA at a university hospital. Mean age was 19.5 years, median age was 16 years (range, 7-54 years). Patients were referred for RFA if they had clinical and radiographic features of OO (Figures 1, 2) and wanted to forgo continued medical management. As we selected only patients with lesions that we thought were amenable to percutaneous RFA—lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper or lower extremity and selected flat bones—en bloc surgical resection was not offered to these patients. Lesions were located in the upper extremity (n = 1), lower extremity (n = 24), and pelvis (n = 3) (Figure 3). Twenty-seven procedures were performed for initial tumor treatment and 1 for recurrence after previous open excision. Two additional procedures were later performed on separate patients with recurrent symptoms after the index procedure. All procedures were performed by the senior author (DML).

Procedure

With each patient, all options were discussed, including continued medical management versus surgical treatment, and informed consent was obtained. All procedures were performed with the patient under general anesthesia in the operating room. RFA for an upper extremity lesion was performed with the patient in the supine position with the ipsilateral extremity draped over a hand table. The 2 procedures for lesions in the talus or calcaneus were performed with the patient in the supine position using a standard table with the bottom of the table flexed down 90° to allow the nonaffected leg to hang over the end of the table. The affected extremity in each case was then positioned in a well-padded leg holder to allow the foot and ankle to be draped free for 360° imaging.

All other procedures for lower extremity diaphyseal or pelvic lesions were performed with a fracture table. After successful induction of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned supine on the table with the contralateral lower extremity abducted and externally rotated in a well-leg holder. The ipsilateral leg was held in the traction apparatus without traction applied and was prepared and draped accordingly (Figure 4). With use of the Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, Pennsylvania), a radiograph was taken of the affected area to identify the lesion. Local anesthetic was infiltrated into the surgical site down to the periosteum. A stab incision was made, and, with fluoroscopic guidance, a 0.062-mm Kirschner wire (K-wire) was placed into the lesion. Location within the tumor nidus was confirmed with biplanar fluoroscopic imaging. A Bonopty cannula (AprioMed, Uppsala, Sweden) was then passed over the K-wire. After the wire was removed, a 5-mm radiofrequency probe (Radionics, Burlington, Massachusetts) was placed through the cannula, and positioning within the nidus was confirmed with 3-dimensional (3-D) CT reconstructions in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes (Figure 5). A radiofrequency generator (Radionics) was used to heat the lesion at 93°C for 7 minutes. The probe and trocar were then removed. Steri-strips and a sterile dressing were used to cover the wound, and the patient was taken to the recovery area after extubation. All patients were discharged home the day of the procedure.

Follow-Up

We phoned all the patients to ask about symptom recurrence, outside treatment, and satisfaction with RFA and to obtain informed consent to participate in our study. Only 1 of the 28 patients could not be reached and was lost to follow-up. Mean follow-up at time of study completion was 31.1 months (range, 5.2-55.8 months).

The 27 patients were asked a series of questions about their treatment: Have you had any recurrence of symptoms following treatment for your OO? Have you received treatment elsewhere? Were you satisfied with your treatment? Would you have the procedure again if you had a recurrence of symptoms?

Primary success was defined as complete pain relief after initial RFA with no evidence of recurrence at time of final follow-up, and secondary success was defined as presence of recurrent symptoms after initial RFA with complete pain relief after a second procedure with no evidence of recurrence.

Results

All RFAs were technically successful with adequate localization of the tumor nidus and subsequent probe placement within the lesion. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. All 28 patients were discharged home the day of procedure. Twenty-six patients (92.8%) experienced complete pain relief after primary RFA, had no evidence of recurrence at final follow-up, and denied symptom recurrence at time of study completion.

The other 2 patients reported symptom recurrence after the index treatment (1 proximal femur lesion, 1 distal femur lesion). One of these patients did well initially but had a recurrence about 2 months after the primary RFA; a second RFA provided complete resolution of pain with no evidence of recurrence at time of study completion. In the other patient’s case, intermittent pain persisted for 2 weeks after the primary RFA, and evidence of recurrence was documented 3 months after surgery; a second RFA was performed shortly thereafter, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

At time of study completion, all 27 patients who had been contacted by phone denied seeking additional treatment elsewhere and stated they would have the procedure again if their symptoms ever recurred.

Discussion

Osteoid osteoma is one of the most common benign tumors of bone. Over the past 2 decades, percutaneous RFA, in comparison with open excision, has emerged as a safe and effective treatment option with minimal patient morbidity.9-11 RFA traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite. However, now orthopedic surgeons can obtain advanced intraoperative imaging beyond standard fluoroscopy. The Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm is an innovative intraoperative imaging device that functions as a standard fluoroscope but also generates 3-D reconstructions of surgical anatomy. The isocentric design and integrated motor unit allow the C-arm to move through a 190º arc while centering its beam directly on the area of interest. This data set is transferred to a computer workstation, where it is reformatted so that CT-quality images are generated in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. This acquisition process takes only minutes, and the multiplanar images produced may be simultaneously displayed and manipulated on the screen in real time.

One concern about this technology is the amount of radiation exposure for patients, surgeons, and operating room staff. The device measures only radiation time, and the amount of exposure during that time depends on the volume and density of the radiated body. We did not calculate the amount of exposure for this study. Mean exposure time was between 20 and 40 seconds, reflecting the number of attempts required to localize the lesion and the surgeon’s experience with the technique. Although the potential for increased exposure is a valid concern, previous studies using this technology have demonstrated that a similar average exposure time is equivalent to that of standard CT, and that use of the device, over conventional techniques, potentially can lead to decreased overall radiation exposure.12,13

This series demonstrated that OO can be safely and effectively treated with intraoperative percutaneous RFA by an orthopedic oncologist. Our success rate is very similar to rates reported in the radiology literature. Studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of this novel technique in comparison with what has been reported in that literature. Given these promising preliminary results, and the relative ease of use and minimal learning curve associated with this technology, all orthopedic oncologists should be able to offer this treatment for OO. Furthermore, this technique allows orthopedic oncologists to provide appropriate definitive treatment and care directly, rather than by referring patients to radiologists.

In the treatment of OO, we reserve RFA for lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper and lower extremities, as well as selected flat bones, such as those in the pelvis. Although percutaneous RFA of spinal lesions has been reported in the literature, we think these represent a relative contraindication for this technique; image resolution, in our opinion, is not high enough to justify risking injury to the nerves in the spinal canal, lateral recesses, and neural foramina. In addition, given the radiation exposure, we recommend caution when using this technique for a pelvic or proximal femoral lesion in a woman of childbearing age.

Osteoid osteoma (OO) is one of the most common benign tumors of bone, representing roughly 10% of all benign bone-forming tumors and 5% of all primary bone tumors.1 The majority of cases occur in individuals under age 20 years and more frequently in males (2:1).2 These lesions tend to be cortically based and most often located about the hip and in the diaphysis of long bones. They typically are characterized radiographically by a nidus less than 2 cm in diameter surrounded by dense, reactive bone of variable thickness.

The classic presentation of OO is localized, dull, aching pain that is worse at night and that is relieved with use of salicylates or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).3 The diagnosis is made by patient history and plain radiographs, often supported by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging for appropriate identification of the tumor nidus. Despite effective pain relief with NSAIDs as well as evidence suggesting that the natural history of these tumors is self-limited, most patients forgo medical management in favor of elective surgical treatment.4,5

Initially, treatment for OO focused on either symptom management or en bloc surgical resection of the tumor nidus. Several different minimally invasive therapies have since been developed, and good results reported.6-8 More recently, use of percutaneous radiofrequency ablation (RFA) has increased, as this method has demonstrated high efficacy and minimal morbidity.9-11 RFA for OO traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite, but advances in intraoperative imaging techniques now allow orthopedic oncologists to perform image-guided RFA in the operating room.

To our knowledge, there have been no reports documenting use of intraoperative CT for localization of OO and use of RFA in the treatment of this lesion. In this article, we report the results of a series of 28 patients with OO treated with intraoperative CT-guided RFA by a single surgeon. We also provide a brief description of this novel technique.

Materials and Methods

The protocol used was approved by our institutional review board. All patients and/or their legal guardians provided informed consent to participate in the study and were informed at the time consent was obtained that case-related data would be submitted for publication.

Patients

Between September 2004 and December 2008, 28 patients (19 males, 9 females) with OO underwent intraoperative percutaneous image-guided RFA at a university hospital. Mean age was 19.5 years, median age was 16 years (range, 7-54 years). Patients were referred for RFA if they had clinical and radiographic features of OO (Figures 1, 2) and wanted to forgo continued medical management. As we selected only patients with lesions that we thought were amenable to percutaneous RFA—lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper or lower extremity and selected flat bones—en bloc surgical resection was not offered to these patients. Lesions were located in the upper extremity (n = 1), lower extremity (n = 24), and pelvis (n = 3) (Figure 3). Twenty-seven procedures were performed for initial tumor treatment and 1 for recurrence after previous open excision. Two additional procedures were later performed on separate patients with recurrent symptoms after the index procedure. All procedures were performed by the senior author (DML).

Procedure

With each patient, all options were discussed, including continued medical management versus surgical treatment, and informed consent was obtained. All procedures were performed with the patient under general anesthesia in the operating room. RFA for an upper extremity lesion was performed with the patient in the supine position with the ipsilateral extremity draped over a hand table. The 2 procedures for lesions in the talus or calcaneus were performed with the patient in the supine position using a standard table with the bottom of the table flexed down 90° to allow the nonaffected leg to hang over the end of the table. The affected extremity in each case was then positioned in a well-padded leg holder to allow the foot and ankle to be draped free for 360° imaging.

All other procedures for lower extremity diaphyseal or pelvic lesions were performed with a fracture table. After successful induction of general anesthesia, the patient was positioned supine on the table with the contralateral lower extremity abducted and externally rotated in a well-leg holder. The ipsilateral leg was held in the traction apparatus without traction applied and was prepared and draped accordingly (Figure 4). With use of the Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm (Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, Pennsylvania), a radiograph was taken of the affected area to identify the lesion. Local anesthetic was infiltrated into the surgical site down to the periosteum. A stab incision was made, and, with fluoroscopic guidance, a 0.062-mm Kirschner wire (K-wire) was placed into the lesion. Location within the tumor nidus was confirmed with biplanar fluoroscopic imaging. A Bonopty cannula (AprioMed, Uppsala, Sweden) was then passed over the K-wire. After the wire was removed, a 5-mm radiofrequency probe (Radionics, Burlington, Massachusetts) was placed through the cannula, and positioning within the nidus was confirmed with 3-dimensional (3-D) CT reconstructions in the sagittal, coronal, and axial planes (Figure 5). A radiofrequency generator (Radionics) was used to heat the lesion at 93°C for 7 minutes. The probe and trocar were then removed. Steri-strips and a sterile dressing were used to cover the wound, and the patient was taken to the recovery area after extubation. All patients were discharged home the day of the procedure.

Follow-Up

We phoned all the patients to ask about symptom recurrence, outside treatment, and satisfaction with RFA and to obtain informed consent to participate in our study. Only 1 of the 28 patients could not be reached and was lost to follow-up. Mean follow-up at time of study completion was 31.1 months (range, 5.2-55.8 months).

The 27 patients were asked a series of questions about their treatment: Have you had any recurrence of symptoms following treatment for your OO? Have you received treatment elsewhere? Were you satisfied with your treatment? Would you have the procedure again if you had a recurrence of symptoms?

Primary success was defined as complete pain relief after initial RFA with no evidence of recurrence at time of final follow-up, and secondary success was defined as presence of recurrent symptoms after initial RFA with complete pain relief after a second procedure with no evidence of recurrence.

Results

All RFAs were technically successful with adequate localization of the tumor nidus and subsequent probe placement within the lesion. There were no intraoperative or postoperative complications. All 28 patients were discharged home the day of procedure. Twenty-six patients (92.8%) experienced complete pain relief after primary RFA, had no evidence of recurrence at final follow-up, and denied symptom recurrence at time of study completion.

The other 2 patients reported symptom recurrence after the index treatment (1 proximal femur lesion, 1 distal femur lesion). One of these patients did well initially but had a recurrence about 2 months after the primary RFA; a second RFA provided complete resolution of pain with no evidence of recurrence at time of study completion. In the other patient’s case, intermittent pain persisted for 2 weeks after the primary RFA, and evidence of recurrence was documented 3 months after surgery; a second RFA was performed shortly thereafter, but the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

At time of study completion, all 27 patients who had been contacted by phone denied seeking additional treatment elsewhere and stated they would have the procedure again if their symptoms ever recurred.

Discussion

Osteoid osteoma is one of the most common benign tumors of bone. Over the past 2 decades, percutaneous RFA, in comparison with open excision, has emerged as a safe and effective treatment option with minimal patient morbidity.9-11 RFA traditionally has been performed by radiologists under CT guidance in the radiology suite. However, now orthopedic surgeons can obtain advanced intraoperative imaging beyond standard fluoroscopy. The Siemens Siremobil ISO-C3D fluoroscopic C-arm is an innovative intraoperative imaging device that functions as a standard fluoroscope but also generates 3-D reconstructions of surgical anatomy. The isocentric design and integrated motor unit allow the C-arm to move through a 190º arc while centering its beam directly on the area of interest. This data set is transferred to a computer workstation, where it is reformatted so that CT-quality images are generated in axial, sagittal, and coronal planes. This acquisition process takes only minutes, and the multiplanar images produced may be simultaneously displayed and manipulated on the screen in real time.

One concern about this technology is the amount of radiation exposure for patients, surgeons, and operating room staff. The device measures only radiation time, and the amount of exposure during that time depends on the volume and density of the radiated body. We did not calculate the amount of exposure for this study. Mean exposure time was between 20 and 40 seconds, reflecting the number of attempts required to localize the lesion and the surgeon’s experience with the technique. Although the potential for increased exposure is a valid concern, previous studies using this technology have demonstrated that a similar average exposure time is equivalent to that of standard CT, and that use of the device, over conventional techniques, potentially can lead to decreased overall radiation exposure.12,13

This series demonstrated that OO can be safely and effectively treated with intraoperative percutaneous RFA by an orthopedic oncologist. Our success rate is very similar to rates reported in the radiology literature. Studies are needed to confirm the efficacy of this novel technique in comparison with what has been reported in that literature. Given these promising preliminary results, and the relative ease of use and minimal learning curve associated with this technology, all orthopedic oncologists should be able to offer this treatment for OO. Furthermore, this technique allows orthopedic oncologists to provide appropriate definitive treatment and care directly, rather than by referring patients to radiologists.

In the treatment of OO, we reserve RFA for lesions involving the long and short bones of the upper and lower extremities, as well as selected flat bones, such as those in the pelvis. Although percutaneous RFA of spinal lesions has been reported in the literature, we think these represent a relative contraindication for this technique; image resolution, in our opinion, is not high enough to justify risking injury to the nerves in the spinal canal, lateral recesses, and neural foramina. In addition, given the radiation exposure, we recommend caution when using this technique for a pelvic or proximal femoral lesion in a woman of childbearing age.

1. Gitelis S, Wilkins R, Conrad EU 2nd. Benign bone tumors. Instr Course Lect. 1996;45:425-424.

2. Schajowicz F. Bone forming tumors. In: Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions of Bone. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1994:36-62.

3. Frassica FJ, Waltrip RL, Sponseller PD, Ma LD, McCarthy EF Jr. Clinicopathologic features and treatment of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(3):559-574.

4. Golding JS. The natural history of osteoid osteoma; with a report of twenty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36(2):218-229.

5. Simm RJ. The natural history of osteoid osteoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1975;45(4):412-415.

6. Sans N, Galy-Fourcade D, Assoun J, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous resection and follow-up in 38 patients. Radiology. 1999;212(3):687-692.

7. Skjeldal S, Lilleås F, Follerås G, et al. Real time MRI-guided excision and cryo-treatment of osteoid osteoma in os ischii—a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(6):637-638.

8. Sanhaji L, Gharbaoui IS, Hassani RE, Chakir N, Jiddane M, Boukhrissi N. A new treatment of osteoid osteoma: percutaneous sclerosis with ethanol under scanner guidance [in French]. J Radiol. 1996;77(1):37-40.

9. Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Torriani M, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous treatment with radiofrequency energy. Radiology. 2003;229(1):171-175.

10. Cantwell CP, Obyrne J, Eustace S. Current trends in treatment of osteoid osteoma with an emphasis on radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(4):607-617.

11. Ruiz Santiago F, Castellano García Mdel M, Guzmán Álvarez L, Martínez Montes JL, Ruiz García M, Tristán Fernández JM. Percutaneous treatment of bone tumors by radiofrequency thermal ablation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):156-163.

12. Richter M, Geerling J, Zech S, Goesling T, Krettek C. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging with a motorized mobile C-Arm (SIREMOBIL ISO-C-3D) in foot and ankle trauma care: a preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(4):259-266.

13. Gebhard F, Kraus M, Schneider E, et al. Radiation dosage in orthopedics—a comparison of computer-assisted procedures [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2003;106(6):492-497.

1. Gitelis S, Wilkins R, Conrad EU 2nd. Benign bone tumors. Instr Course Lect. 1996;45:425-424.

2. Schajowicz F. Bone forming tumors. In: Tumors and Tumorlike Lesions of Bone. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 1994:36-62.

3. Frassica FJ, Waltrip RL, Sponseller PD, Ma LD, McCarthy EF Jr. Clinicopathologic features and treatment of osteoid osteoma and osteoblastoma in children and adolescents. Orthop Clin North Am. 1996;27(3):559-574.

4. Golding JS. The natural history of osteoid osteoma; with a report of twenty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36(2):218-229.

5. Simm RJ. The natural history of osteoid osteoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1975;45(4):412-415.

6. Sans N, Galy-Fourcade D, Assoun J, et al. Osteoid osteoma: CT-guided percutaneous resection and follow-up in 38 patients. Radiology. 1999;212(3):687-692.

7. Skjeldal S, Lilleås F, Follerås G, et al. Real time MRI-guided excision and cryo-treatment of osteoid osteoma in os ischii—a case report. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71(6):637-638.

8. Sanhaji L, Gharbaoui IS, Hassani RE, Chakir N, Jiddane M, Boukhrissi N. A new treatment of osteoid osteoma: percutaneous sclerosis with ethanol under scanner guidance [in French]. J Radiol. 1996;77(1):37-40.

9. Rosenthal DI, Hornicek FJ, Torriani M, Gebhardt MC, Mankin HJ. Osteoid osteoma: percutaneous treatment with radiofrequency energy. Radiology. 2003;229(1):171-175.

10. Cantwell CP, Obyrne J, Eustace S. Current trends in treatment of osteoid osteoma with an emphasis on radiofrequency ablation. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(4):607-617.

11. Ruiz Santiago F, Castellano García Mdel M, Guzmán Álvarez L, Martínez Montes JL, Ruiz García M, Tristán Fernández JM. Percutaneous treatment of bone tumors by radiofrequency thermal ablation. Eur J Radiol. 2011;77(1):156-163.

12. Richter M, Geerling J, Zech S, Goesling T, Krettek C. Intraoperative three-dimensional imaging with a motorized mobile C-Arm (SIREMOBIL ISO-C-3D) in foot and ankle trauma care: a preliminary report. J Orthop Trauma. 2005;19(4):259-266.

13. Gebhard F, Kraus M, Schneider E, et al. Radiation dosage in orthopedics—a comparison of computer-assisted procedures [in German]. Unfallchirurg. 2003;106(6):492-497.