User login

A man with HIV and papules and nodules on the knees

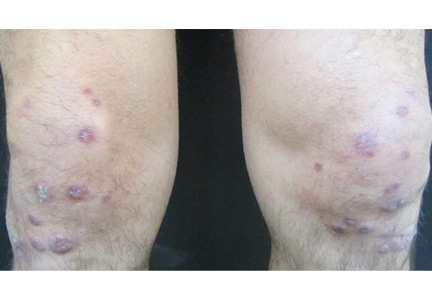

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

A 39-year-old man with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and a CD4 cell count of 528 × 106/L without treatment was referred for evaluation of periarticular, indurated, erythematous papules and nodules on the knees and elbows and purpuric lesions on the ankles (Figure 1). He has had recurrent fever, arthralgia, and mild constitutional symptoms during the past month. He also reported a diagnosis of polyclonal immunoglobulin A gammopathy.

Punch biopsy of the purpuric lesions was performed, and histologic study showed leukocytoclastic vasculitis with eosinophilic necrosis of the epithelium.

Treatment with a systemic corticosteroid was started. The purpuric lesions disappeared after 3 weeks of therapy, but the nodules over the extensor surface of both knees showed no improvement (Figure 2). Subsequent biopsy of late-stage lesions (3 months after the start of therapy) demonstrated perivascular fibrosis with small, persistent foci of vasculitis, and confirmed the diagnosis of HIV-associated nodular erythema elevatum diutinum (EED). Antiretroviral therapy was started in addition to intralesional corticosteroids and topical dapsone 5% gel, with resolution of the lesions 1 month later.

ERYTHEMA ELEVATUM DIUTINUM

EED is an uncommon chronic dermatosis, classified as a fibrosing form of leukocytoclastic vasculitis and characterized clinically by violaceous papules, plaques, and nodules, usually distributed acrally and symmetrically over extensor surfaces. The histopathologic picture depends on the stage of the lesion. Features of leukocytoclastic vasculitis are found in early-stage lesions, while a fibrotic replacement of the dermis with small persistent foci of vasculitis is typical of late-stage lesions.

EED has clinical and histopathologic similarities to Sweet syndrome, but EED is distinguished from neutrophilic dermatosis by vasculitis.

In HIV-infected patients, it is important to include pruritic papular eruption in the differential diagnosis. It is characterized by chronic bilaterally symmetric pruritic papules on the trunk and extremities and is the most common cutaneous noninfectious manifestation of HIV.

The clinical presentation of EED may also be easily confused with Kaposi sarcoma and bacillary angiomatosis.2

AN EMERGING HIV-RELATED DERMATOSIS

EED is emerging as a specific HIV-associated dermatosis, with 20 cases reported in the medical literature as of this writing.3

The cause of EED is not known, but it is often associated with streptococcal infection, monoclonal IgA gammopathy, hematologic malignancy, cryoglobulinemia, rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune disease.3 The stimulus could be immune-complex deposition in blood vessels triggered by HIV infection, or by another infection acting as an antigenic stimulus.4 The nodular variant of EED is even rarer, but it evolves most often in HIV-positive individuals.5,6

Oral dapsone is the treatment of choice but is less effective in late-stage fibrotic lesions.7 Treatment courses tend to be long and recurrence is common.8 Intralesional, topical, and oral corticosteroids, topical dapsone 5% gel,9 tetracycline and nicotinamide, sulfonamides, colchicine, chloroquine, and surgical excision are other options.

Our patient’s presentation reminds us to consider EED in HIV-infected patients and illustrates the importance of histologic diagnosis to differentiate EED from assumed Kaposi sarcoma in patients with HIV. EED can also be the first clinical sign of HIV infection. It is important to rule out underlying disorders such as HIV infection, because directed therapy is often the best management.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.

- Yiannias JA, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a clinical and histopathologic study of 13 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1992; 26:38–44.

- Requena L, Sánchez Yus E, Martín L, Barat A, Arias D. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Another clinical simulator of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Arch Dermatol 1991; 127:1819–1822.

- Momen SE, Jorizzo J, Al-Niaimi F. Erythema elevatum diutinum: a review of presentation and treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2014; 28:1594–1602.

- Muratori S, Carrera C, Gorani A, Alessi E. Erythema elevatum diutinum and HIV infection: a report of five cases. Br J Dermatol 1999; 141:335–338.

- LeBoit PE, Cockerell CJ. Nodular lesions of erythema elevatum diutinum in patients infected with the human immunodeficiency virus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1993; 28:919–922.

- Rover PA, Bittencourt C, Discacciati MP, Zaniboni MC, Arruda LH, Cintra ML. Erythema elevatum diutinum as a first clinical manifestation for diagnosing HIV infection: case history. Sao Paulo Med J 2005; 123:201–203.

- Fakheri A, Gupta SM, White SM, Don PC, Weinberg JM. Erythema elevatum diutinum in a patient with human immunodeficiency virus. Cutis 2001; 68:41–42.

- Katz SI, Gallin JL, Hertz KC, Fauci AS, Lawley TJ. Erythema elevatum diutinum: skin and systemic manifestations, immunologic studies, and successful treatment with dapsone. Medicine (Baltimore) 1977; 56:443–455.

- Frieling GW, Williams NL, Lim SJ, Rosenthal SI. Novel use of topical dapsone 5% gel for erythema elevatum diutinum: safer and effective. J Drugs Dermatol 2013; 12:481–484.