User login

Hypotrichosis and Hair Loss on the Occipital Scalp

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

A diagnosis of monilethrix was rendered based on the clinical and trichoscopic findings. Simple surveillance of the patient’s condition and prevention of further hair trauma were proposed as management options.

Monilethrix is a hair shaft disorder that is inherited in a predominantly autosomal-dominant pattern with variable expressiveness and penetrance resulting from heterozygous mutations in hair keratin genes KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86 in a region of chromosome 12q13.13.1,2 An autosomalrecessive form has been described with mutation in desmoglein 4, but it differs from the classical form by the variable periodicity of the region between the nodules.3,4

The morphologic alteration consists of the formation of fusiform nodules of normal structure alternated with narrow and dystrophic constrictions (Figure). These internodes are fragile areas that cause breakage at constricted points.5 Clinically, monilethrix presents as areas of focal or diffuse alopecia with frequent involvement of the terminal follicles, mainly in areas of friction. The hair is normal at birth due to the predominance of lanugo in the neonatal period, but it subsequently is replaced by abnormal hairs in the first months of life.6 Initial clinical signs begin to appear when the terminal hairs begin to form.7 Although rarer, the eyebrows and eyelashes, as well as the axillary, pubic, and body hair, may be involved.5

Other hair shaft anomalies merit consideration in the differential diagnosis of monilethrix, including pseudomonilethrix, pressure alopecia, trichorrhexis invaginata, ectodermal dysplasia, tinea capitis, and trichothiodystrophy.6 The diagnosis is reached by clinical history and physical examination. Trichoscopy and light microscopy are used to confirm the diagnosis. Trichoscopic examination shows markedly higher rates of anagen hair. The shafts examined in our patient revealed 0.7- to 1-mm intervals between nodes. Hair can be better visualized under a polarized microscope, and the condition can be distinguished from pseudomonilethrix using this approach.5,6 In our patient, the diagnosis was made based on light microscopy and trichoscopic findings with no genetic testing; however, genetic testing for the classic mutations of the keratin genes would be desirable to confirm the diagnosis but was not done in our patient.6 The prognosis of monilethrix is variable; most cases persist into adulthood, though spontaneous improvement may occur with advancing age, during summer, and during pregnancy.8

There is no definitive therapy for monilethrix. Although there have been reports of cases treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral retinoids, topical minoxidil, vitamins, and peeling ointments (desquamative oil), the cornerstone of management is protecting the hair against traumatic procedures such as excessive combing, brushing, and friction, as well as parent and patient education about the benign nature of the condition.9 Additionally, some cases have shown improvement with minoxidil solution at 2% and 5% concentrations, oral minoxidil, or acitretin.7-9

- Fontenelle de Oliveira E, Cotta de Alencar Araripe AL. Monilethrix: a typical case report with microscopic and dermatoscopic findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:126-127.

- de Cruz R, Horev L, Green J, et al. A novel monilethrix mutation in coil 2A of KRT86 causing autosomal dominant monilethrix with incomplete penetrance. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(suppl 2):20-26.

- Baltazard T, Dhaille F, Chaby G, et al. Value of dermoscopy for the diagnosis of monilethrix. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030 /qt9hf1p3xm.

- Kato M, Shimizu A, Yokoyama Y, et al. An autosomal recessive mutation of DSG4 causes monilethrix through the ER stress response. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1253-1260.

- Gummer CL, Dawber RP, Swift JA. Monilethrix: an electron microscopic and electron histochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 1981;105:529-541.

- Sharma VK, Chiramel MJ, Rao A. Dermoscopy: a rapid bedside tool to assess monilethrix. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:73-74.

- Sinclair R. Treatment of monilethrix with oral minoxidil. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:212-215.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Czuwara J, et al. Dermoscopy as a tool for rapid diagnosis of monilethrix. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:222-224.

- Karincaoglu Y, Coskun BK, Seyhan ME, et al. Monilethrix. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:407-410.

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

A diagnosis of monilethrix was rendered based on the clinical and trichoscopic findings. Simple surveillance of the patient’s condition and prevention of further hair trauma were proposed as management options.

Monilethrix is a hair shaft disorder that is inherited in a predominantly autosomal-dominant pattern with variable expressiveness and penetrance resulting from heterozygous mutations in hair keratin genes KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86 in a region of chromosome 12q13.13.1,2 An autosomalrecessive form has been described with mutation in desmoglein 4, but it differs from the classical form by the variable periodicity of the region between the nodules.3,4

The morphologic alteration consists of the formation of fusiform nodules of normal structure alternated with narrow and dystrophic constrictions (Figure). These internodes are fragile areas that cause breakage at constricted points.5 Clinically, monilethrix presents as areas of focal or diffuse alopecia with frequent involvement of the terminal follicles, mainly in areas of friction. The hair is normal at birth due to the predominance of lanugo in the neonatal period, but it subsequently is replaced by abnormal hairs in the first months of life.6 Initial clinical signs begin to appear when the terminal hairs begin to form.7 Although rarer, the eyebrows and eyelashes, as well as the axillary, pubic, and body hair, may be involved.5

Other hair shaft anomalies merit consideration in the differential diagnosis of monilethrix, including pseudomonilethrix, pressure alopecia, trichorrhexis invaginata, ectodermal dysplasia, tinea capitis, and trichothiodystrophy.6 The diagnosis is reached by clinical history and physical examination. Trichoscopy and light microscopy are used to confirm the diagnosis. Trichoscopic examination shows markedly higher rates of anagen hair. The shafts examined in our patient revealed 0.7- to 1-mm intervals between nodes. Hair can be better visualized under a polarized microscope, and the condition can be distinguished from pseudomonilethrix using this approach.5,6 In our patient, the diagnosis was made based on light microscopy and trichoscopic findings with no genetic testing; however, genetic testing for the classic mutations of the keratin genes would be desirable to confirm the diagnosis but was not done in our patient.6 The prognosis of monilethrix is variable; most cases persist into adulthood, though spontaneous improvement may occur with advancing age, during summer, and during pregnancy.8

There is no definitive therapy for monilethrix. Although there have been reports of cases treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral retinoids, topical minoxidil, vitamins, and peeling ointments (desquamative oil), the cornerstone of management is protecting the hair against traumatic procedures such as excessive combing, brushing, and friction, as well as parent and patient education about the benign nature of the condition.9 Additionally, some cases have shown improvement with minoxidil solution at 2% and 5% concentrations, oral minoxidil, or acitretin.7-9

The Diagnosis: Monilethrix

A diagnosis of monilethrix was rendered based on the clinical and trichoscopic findings. Simple surveillance of the patient’s condition and prevention of further hair trauma were proposed as management options.

Monilethrix is a hair shaft disorder that is inherited in a predominantly autosomal-dominant pattern with variable expressiveness and penetrance resulting from heterozygous mutations in hair keratin genes KRT81, KRT83, and KRT86 in a region of chromosome 12q13.13.1,2 An autosomalrecessive form has been described with mutation in desmoglein 4, but it differs from the classical form by the variable periodicity of the region between the nodules.3,4

The morphologic alteration consists of the formation of fusiform nodules of normal structure alternated with narrow and dystrophic constrictions (Figure). These internodes are fragile areas that cause breakage at constricted points.5 Clinically, monilethrix presents as areas of focal or diffuse alopecia with frequent involvement of the terminal follicles, mainly in areas of friction. The hair is normal at birth due to the predominance of lanugo in the neonatal period, but it subsequently is replaced by abnormal hairs in the first months of life.6 Initial clinical signs begin to appear when the terminal hairs begin to form.7 Although rarer, the eyebrows and eyelashes, as well as the axillary, pubic, and body hair, may be involved.5

Other hair shaft anomalies merit consideration in the differential diagnosis of monilethrix, including pseudomonilethrix, pressure alopecia, trichorrhexis invaginata, ectodermal dysplasia, tinea capitis, and trichothiodystrophy.6 The diagnosis is reached by clinical history and physical examination. Trichoscopy and light microscopy are used to confirm the diagnosis. Trichoscopic examination shows markedly higher rates of anagen hair. The shafts examined in our patient revealed 0.7- to 1-mm intervals between nodes. Hair can be better visualized under a polarized microscope, and the condition can be distinguished from pseudomonilethrix using this approach.5,6 In our patient, the diagnosis was made based on light microscopy and trichoscopic findings with no genetic testing; however, genetic testing for the classic mutations of the keratin genes would be desirable to confirm the diagnosis but was not done in our patient.6 The prognosis of monilethrix is variable; most cases persist into adulthood, though spontaneous improvement may occur with advancing age, during summer, and during pregnancy.8

There is no definitive therapy for monilethrix. Although there have been reports of cases treated with systemic corticosteroids, oral retinoids, topical minoxidil, vitamins, and peeling ointments (desquamative oil), the cornerstone of management is protecting the hair against traumatic procedures such as excessive combing, brushing, and friction, as well as parent and patient education about the benign nature of the condition.9 Additionally, some cases have shown improvement with minoxidil solution at 2% and 5% concentrations, oral minoxidil, or acitretin.7-9

- Fontenelle de Oliveira E, Cotta de Alencar Araripe AL. Monilethrix: a typical case report with microscopic and dermatoscopic findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:126-127.

- de Cruz R, Horev L, Green J, et al. A novel monilethrix mutation in coil 2A of KRT86 causing autosomal dominant monilethrix with incomplete penetrance. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(suppl 2):20-26.

- Baltazard T, Dhaille F, Chaby G, et al. Value of dermoscopy for the diagnosis of monilethrix. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030 /qt9hf1p3xm.

- Kato M, Shimizu A, Yokoyama Y, et al. An autosomal recessive mutation of DSG4 causes monilethrix through the ER stress response. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1253-1260.

- Gummer CL, Dawber RP, Swift JA. Monilethrix: an electron microscopic and electron histochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 1981;105:529-541.

- Sharma VK, Chiramel MJ, Rao A. Dermoscopy: a rapid bedside tool to assess monilethrix. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:73-74.

- Sinclair R. Treatment of monilethrix with oral minoxidil. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:212-215.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Czuwara J, et al. Dermoscopy as a tool for rapid diagnosis of monilethrix. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:222-224.

- Karincaoglu Y, Coskun BK, Seyhan ME, et al. Monilethrix. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:407-410.

- Fontenelle de Oliveira E, Cotta de Alencar Araripe AL. Monilethrix: a typical case report with microscopic and dermatoscopic findings. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:126-127.

- de Cruz R, Horev L, Green J, et al. A novel monilethrix mutation in coil 2A of KRT86 causing autosomal dominant monilethrix with incomplete penetrance. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166(suppl 2):20-26.

- Baltazard T, Dhaille F, Chaby G, et al. Value of dermoscopy for the diagnosis of monilethrix. Dermatol Online J. 2017;23:13030 /qt9hf1p3xm.

- Kato M, Shimizu A, Yokoyama Y, et al. An autosomal recessive mutation of DSG4 causes monilethrix through the ER stress response. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:1253-1260.

- Gummer CL, Dawber RP, Swift JA. Monilethrix: an electron microscopic and electron histochemical study. Br J Dermatol. 1981;105:529-541.

- Sharma VK, Chiramel MJ, Rao A. Dermoscopy: a rapid bedside tool to assess monilethrix. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:73-74.

- Sinclair R. Treatment of monilethrix with oral minoxidil. JAAD Case Rep. 2016;2:212-215.

- Rakowska A, Slowinska M, Czuwara J, et al. Dermoscopy as a tool for rapid diagnosis of monilethrix. J Drugs Dermatol. 2007;6:222-224.

- Karincaoglu Y, Coskun BK, Seyhan ME, et al. Monilethrix. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:407-410.

A 6-month-old infant girl was referred to the dermatology service with hypotrichosis and hair loss on the occipital region of the scalp of 4 months’ duration (top). The patient was born at full term by cesarean delivery without complications. There were no comorbidities or family history of alopecia. Clinical examination revealed an alopecic plaque in the occipital region with broken hairs and some dystrophic hairs associated with follicular papules and perifollicular hyperkeratosis. A hair pull test was positive for telogen hairs. Trichoscopy revealed black dots and broken hairs resembling Morse code (bottom). Hair microscopy showed regular alternation of constriction zones separated by intervals of normal thickness.

Cardiofaciocutaneous Syndrome and the Dermatologist’s Contribution to Diagnosis

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

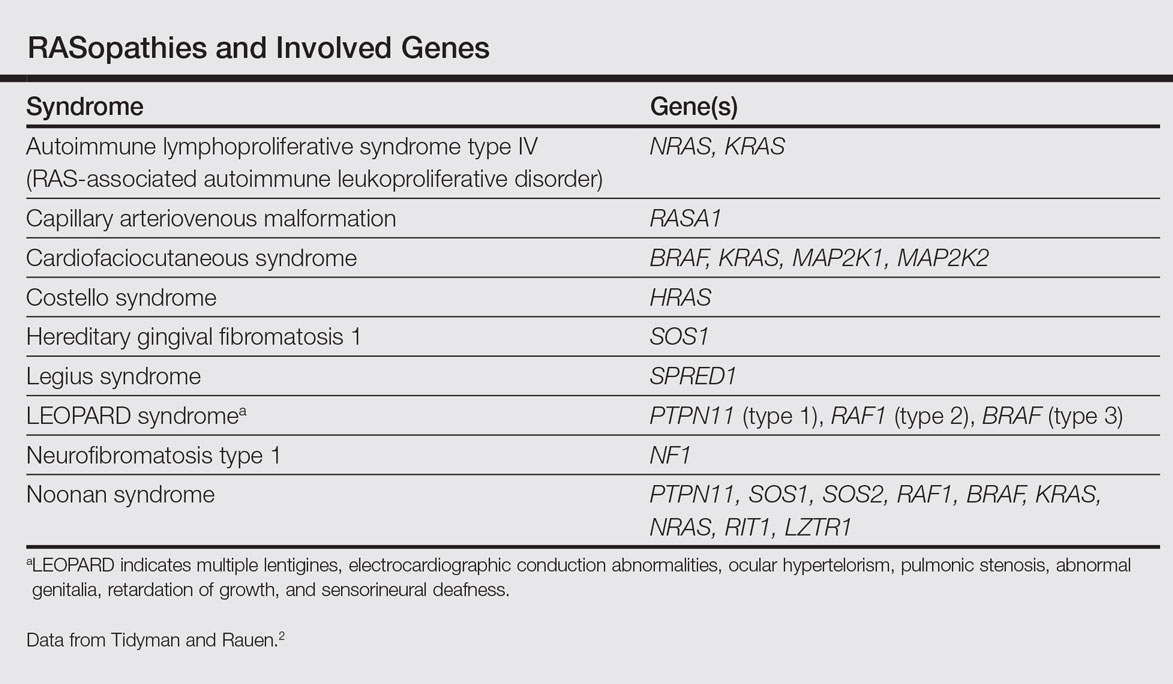

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

To the Editor:

RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway. Each syndrome exhibits its phenotypic features; however, because all of them cause dysregulation of the RAS/MAPK pathway, there are numerous overlapping phenotypic features between the syndromes including cardiac defects, cutaneous abnormalities, characteristic facial features, neurocognitive impairment, and increased risk for developing some neoplastic disorders.

Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy and is a genetic sporadic disease characterized by multiple congenital anomalies associated with mental retardation. It has a complex dermatological phenotype with many cutaneous features that can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes, which also are classified as RASopathies.

A 3-year-old girl presented with skin xerosis and follicular hyperkeratosis of the face, neck, trunk, and limbs (Figure 1). Facial follicular hyperkeratotic papules on an erythematous base were associated with alopecia of the eyebrows (ulerythema ophryogenes). Hair was sparse and curly (Figure 2A). Facial dysmorphic features included a prominent forehead with bitemporal constriction, bilateral ptosis, a broad nasal base, lip contour in a Cupid’s bow, low-set earlobes with creases (Figure 2B), and a short and webbed neck.

Congenital heart disease, hypothyroidism, bilateral hydronephrosis, delayed motor development, and seizures were noted for the first 2 years. Brain computed tomography detected a dilated ventricular system with hydrocephalus. There was no family history of consanguinity.

Pregnancy was complicated by polyhydramnios and preeclampsia. The neonate was delivered at full-term and was readmitted at 6 days of age due to respiratory failure secondary to congenital chylothorax. Cardiac malformation was diagnosed as the ostium secundum atrial septal defect and interventricular and atrioventricular septal defects. Up to this point she was being treated for Turner syndrome.

The RASopathies are a class of human genetic syndromes that are caused by germ line mutations in genes that encode components of the RAS/MAPK pathway.1 There are many syndromes classified as RASopathies (Table).2,3

Cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man [OMIM] 115150) is a genetic disorder first described by Reynolds et al4 and is characterized by several cutaneous abnormalities, cardiac defects, dysmorphic craniofacial features, gastrointestinal dysmotility, and mental retardation. It occurs sporadically and is caused by functional activation of mutations in 4 different genes—BRAF, KRAS, MAP2K1, MAP2K2—of the RAS extracellular signal–regulated kinase molecular cascade that regulates cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis.1

As a RASopathy, CFC syndrome is a member of a family of syndromes with similar phenotypes, which includes mainly Noonan and Costello syndromes. Psychomotor retardation and physical anomalies, the common denominator of all syndromes, may be explained by the effects of the mutations during early development.5,6

In CFC, relative macrocephaly, prominent forehead, bitemporal constriction, absence of eyebrows, palpebral ptosis, broad nasal root, bulbous nasal tip, and small chin commonly are found. The eyes are widely spaced and the palpebral fissures are downward slanting with epicanthic folds.1,4,7

Follicular keratosis of the arms, legs, and face occurs in 80% of cases of CFC and ulerythema ophryogenes with sparse eyebrows in 90% of cases. Sparse, curly, and slow-growing hair is found in 93% of patients. Xerotic scaly skin, hyperkeratosis of the palms and soles, infantile hemangiomas, and multiple melanocytic nevi also may occur.8

Cardiac abnormalities are seen in 75.7% of patients.1 Other features include mental retardation, delayed motor development, and structural abnormalities in the central nervous system, as well as seizures and electroencephalogram abnormalities. Unlike Noonan and Costello syndromes, it is unclear if patients with CFC syndrome are at an increased risk for cancer.1

Noonan syndrome (OMIM #163950) is a disorder characterized by congenital heart defects, short stature, skeletal abnormalities, distinctive facial dysmorphic features, and variable cognitive deficits. Other associated features include cryptorchidism, lymphatic dysplasia, bleeding tendency, and occasional hematologic malignancies during childhood. This syndrome is related to mutations in the PTPN11, SOS1, SOS2, RAF1, BRAF, KRAS, NRAS, RIT1, and LZTR1 genes.2,9-11 The typical ear shape and placement in Noonan syndrome is oval with an overfolded helix that is low set and posteriorly angulated, which is uncommon in CFC syndrome. Noonan syndrome is characterized by an inverted triangular face; hypertelorism; blue or blue-green iris color; webbed neck; limited skin involvement, mainly represented by multiple nevi; and a much milder developmental delay compared to CFC and Costello syndromes.1,11

Costello syndrome (OMIM #218040) is a rare condition comprised of severe postnatal feeding difficulties, mental retardation, coarse facial features, cardiovascular abnormalities (eg, pulmonic stenosis, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, atrial tachycardia), tumor predisposition, and skin and musculoskeletal abnormalities.12 Costello syndrome is clinically diagnosed. This syndrome shows coarse facies with macrocephaly, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, epicanthal folds, bulbous nose with anteversed nostrils and low nasal bridge, full cheeks, large mouth, thick lips, large tongue, nasal papillomas, cutis laxa, low-set ears, short neck, diffuse skin hyperpigmentation, ulnar deviation of the hands, and nail dystrophy that are not observed in CFC. It is now accepted that the term Costello syndrome should be reserved for patients with HRAS mutation because of the specific risk profile of these patients.12 Remarkably, patients with Costello syndrome are at increased tumor risk (eg, rhabdomyosarcoma, neuroblastoma, bladder carcinoma).2,12

The diagnosis of CFC syndrome is purely clinical. There have been many attempts to delineate the syndrome, but none of the described traits are pathognomonic. In 2002, Kavamura et al7 created the CFC index, a useful diagnostic approach based on 82 clinical characteristics and their frequencies in the CFC population.

Skin abnormalities are helpful manifestations to differentiate CFC syndrome from Noonan and Costello syndromes. Patients with CFC syndrome present with follicular hyperkeratosis and absent eyebrows. Absent eyebrows, narrowed temples, and Cupid’s bow lip are hallmark features of CFC syndrome and are absent in Noonan and Costello syndromes. The presentation of palmoplantar hyperkeratosis also is a differentiating feature; in patients with Costello syndrome, it is found outside the pressure zones, whereas in those with CFC syndrome, it is present mainly in the pressure zones.1 Dermatologists can assist geneticists in the differential diagnosis of these syndromes.

The treatment of disorders with follicular plugging and xerosis is challenging. Emollients with urea, glycolic acid, and lactic acid could improve the appearance of the skin. Treatment with mutated MEK gene inhibitors is under investigation to restore normal development of affected embryos with CFC.2,13 This case and theoretical data show that skin manifestations can be helpful to differentiate CFC syndrome from other RASopathies such as Noonan and Costello syndromes.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

- Roberts A, Allanson J, Jadico SK, et al. The cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. J Med Genet. 2006;43:833-842.

- Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. The RASopathies: developmental syndromes of Ras/MAPK pathway dysregulation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2009;19:230-236.

- Stevenson D, Viskochil D, Mao R, et al. Legius syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK47312.

- Reynolds JF, Neri G, Herrmann JP, et al. New multiple congenital anomalies/mental retardation syndrome with cardio-facio-cutaneous involvement—the CFC syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 1986;25:413-427.

- Zenker M, Lehmann K, Schulz AL, et al. Expansion of the genotypic and phenotypic spectrum in patients with KRAS germline mutations. J Med Genet. 2007;44:131-135.

- Rodriguez-Viciana P, Tetsu O, Tidyman WE, et al. Germline mutations in genes within the MAPK pathway cause cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Science. 2006;311:1287-1290.

- Kavamura MI, Peres CA, Alchorne MM, et al. CFC index for the diagnosis of cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Am J Med Genet. 2002;112:12-16.

- Siegel DH, McKenzie J, Frieden IJ, et al. Dermatological findings in 61 mutation-positive individuals with cardiofaciocutaneous syndrome. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:521-529.

- Tartaglia M, Zampino G, Gelb BD. Noonan syndrome: clinical aspects and molecular pathogenesis. Mol Syndromol. 2010;1:2-26.

- Lo FS, Lin JL, Kuo MT, et al. Noonan syndrome caused by germline KRAS mutation in Taiwan: report of two patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2009;168:919-923.

- Allanson JE, Roberts AE. Noonan syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1124/.

- Gripp KW, Lin AE. Costello syndrome. In: Pagon RA, Bird TD, Dolan CR, et al, eds. GeneReviews. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1507/.

- Inoue S, Moriya M, Watanabe Y, et al. New BRAF knockin mice provide a pathogenetic mechanism of developmental defects and a therapeutic approach in cardio-facio-cutaneous syndrome. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:6553-6566.

Practice Points

- RASopathies, a class of developmental disorders, are caused by mutations in genes that encode protein components of the RAS/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Cardiofaciocutaneous (CFC) syndrome is a RASopathy.

- Skin manifestations may help in differentiating CFC syndrome from other RASopathies.