User login

Blaschkolinear Lupus Erythematosus: Strategies for Early Detection and Management

To the Editor:

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) is an inflammatory condition with myriad cutaneous manifestations. Most forms of CCLE have the potential to progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus (BLE) is an exceedingly rare subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that usually manifests during childhood as linear plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,3 Under normal conditions, Blaschko lines are not noticeable; they correspond to the direction of ectodermal cell migration during cutaneous embryogenesis.4,5 The embryonic cells travel ventrolaterally, forming a V-shaped pattern on the back, an S-shaped pattern on the trunk, and an hourglass-shaped pattern on the face with several perpendicular intersections near the mouth and nose.6 During their migration, the cells are susceptible to somatic mutations and clonal expansion, resulting in a monoclonal population of genetically heterogenous cells. This phenomenon is known as somatic mosaicism and may lead to an increased susceptibility to an array of congenital and inflammatory dermatoses, such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.4 Blaschkolinear entities tend to manifest in a unilateral distribution following exposure to a certain environmental trigger, such as trauma, viral illness, or UV radiation, although a trigger is not always present.7 We report a case of BLE manifesting on the head and neck in an adult patient.

A 46-year-old man presented with a pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration on the right cheek that extended inferiorly to the right upper chest. He had a medical history of well-controlled psoriasis, and he denied any antecedent trauma, fevers, chills, arthralgia, or night sweats. There had been no improvement with mometasone ointment 0.1% applied daily for 2 months as prescribed by his primary care provider. Physical examination revealed indurated, red-brown, atrophic plaques in a blaschkolinear distribution around the nose, right upper jaw, right side of the neck, and right upper chest (Figure, A).

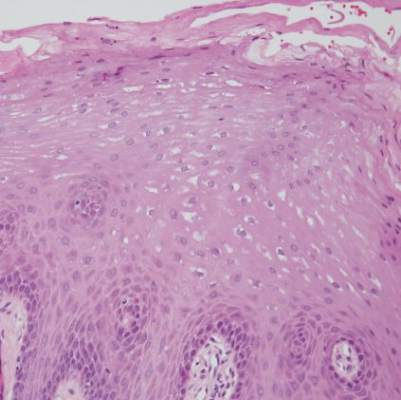

Histopathology of punch biopsies from the right jaw and right upper chest showed an atrophic epidermis with scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer. A superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate was observed in both biopsies. Staining with Verhoeff-van Gieson elastin and periodic acid–Schiff highlighted prominent basement membrane thickening and loss of elastic fibers in the superficial dermis. These findings favored a diagnosis of CCLE, and the clinical blaschkolinear distribution of the rash led to our specific diagnosis of BLE. Laboratory workup for SLE including a complete blood cell count; urine analysis; and testing for liver and kidney function, antinuclearantibodies, complement levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate revealed no abnormalities.

The patient started hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and methotrexate 25 mg weekly along with strict photoprotection measures, including wearing photoprotective clothing and avoiding sunlight during the most intense hours of the day.

Linear lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis to consider in patients with a blaschkolinear eruption.7 Although the clinical manifestations of BLE and linear lichen planus are similar, they differ histopathologically. One study found that only 33.3% of patients (6/18) who clinically presented with blaschkolinear eruptions were correctly diagnosed before histologic examination.7 Visualization of the adnexa as well as the superficial and deep vascular plexuses is paramount in distinguishing between linear lichen planus and BLE; linear lichen planus does not have perivascular and periadnexal infiltration, while BLE does. Thus, in our experience, a punch biopsy—rather than a shave biopsy—should be performed to access the deeper layers of the skin.

Because these 2 entities have noteworthy differences in their management, prognosis, and long-term follow-up, accurate diagnosis is critical. To start, BLE is treated with the use of photoprotection, whereas linear lichen planus is commonly treated with phototherapy. Given the potential for forms of CCLE to progress to SLE, serial monitoring is indicated in patients with BLE. As the risk for progression to SLE is highest in the first 3 years after diagnosis, a review of systems and laboratory testing should occur every 2 to 3 months in the first year after diagnosis (sooner if the disease presentation is more severe).9 Also, treatment with hydroxychloroquine likely delays transformation to SLE and is important in the early management of BLE.10 On the other hand, linear lichen planus tends to self-resolve without progression to systemic involvement, warranting limited follow-up.9

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus typically manifests in childhood, but it also can be seen in adults, such as in our patient. Adult-onset BLE is rare but may be underrecognized or underreported in the literature.11 However, dermatologists should consider it in the differential diagnosis for any patient with a blaschkolinear eruption, as establishing the correct diagnosis is key to ensuring prompt and effective treatment for this rare inflammatory condition.

- Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the association with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort of 1088 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1335-1341. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10272.x

- Requena C, Torrelo A, de Prada I, et al. Linear childhood cutaneous lupus erythematosus following Blaschko lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:618-620. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00588.x

- Lim D, Hatami A, Kokta V, et al. Linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in children-report of two cases and review of the literature: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313x20979206. doi:10.1177/2050313X20979206

- Jin H, Zhang G, Zhou Y, et al. Old lines tell new tales: Blaschko linear lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:291-306. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.014

- Yu S, Yu H-S. A patient with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus along Blaschko lines: implications for the role of keratinocytes in lupus erythematosus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2016;34:144-147. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2015.12.002

- Kouzak SS, Mendes MST, Costa IMC. Cutaneous mosaicisms: concepts, patterns and classifications. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:507-517. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132015

- Liu W, Vano-Galvan S, Liu J-W, et al. Pigmented linear discoid lupus erythematosus following the lines of Blaschko: a retrospective study of a Chinese series. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:359-365. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_341_19

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

- Curtiss P, Walker AM, Chong BF. A systematic review of the progression of cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2022:13:866319. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.866319

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

- Milosavljevic K, Fibeger E, Virata AR. A case of linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a 55-year-old woman. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:E921495. doi:10.12659/AJCR.921495

To the Editor:

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) is an inflammatory condition with myriad cutaneous manifestations. Most forms of CCLE have the potential to progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus (BLE) is an exceedingly rare subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that usually manifests during childhood as linear plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,3 Under normal conditions, Blaschko lines are not noticeable; they correspond to the direction of ectodermal cell migration during cutaneous embryogenesis.4,5 The embryonic cells travel ventrolaterally, forming a V-shaped pattern on the back, an S-shaped pattern on the trunk, and an hourglass-shaped pattern on the face with several perpendicular intersections near the mouth and nose.6 During their migration, the cells are susceptible to somatic mutations and clonal expansion, resulting in a monoclonal population of genetically heterogenous cells. This phenomenon is known as somatic mosaicism and may lead to an increased susceptibility to an array of congenital and inflammatory dermatoses, such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.4 Blaschkolinear entities tend to manifest in a unilateral distribution following exposure to a certain environmental trigger, such as trauma, viral illness, or UV radiation, although a trigger is not always present.7 We report a case of BLE manifesting on the head and neck in an adult patient.

A 46-year-old man presented with a pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration on the right cheek that extended inferiorly to the right upper chest. He had a medical history of well-controlled psoriasis, and he denied any antecedent trauma, fevers, chills, arthralgia, or night sweats. There had been no improvement with mometasone ointment 0.1% applied daily for 2 months as prescribed by his primary care provider. Physical examination revealed indurated, red-brown, atrophic plaques in a blaschkolinear distribution around the nose, right upper jaw, right side of the neck, and right upper chest (Figure, A).

Histopathology of punch biopsies from the right jaw and right upper chest showed an atrophic epidermis with scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer. A superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate was observed in both biopsies. Staining with Verhoeff-van Gieson elastin and periodic acid–Schiff highlighted prominent basement membrane thickening and loss of elastic fibers in the superficial dermis. These findings favored a diagnosis of CCLE, and the clinical blaschkolinear distribution of the rash led to our specific diagnosis of BLE. Laboratory workup for SLE including a complete blood cell count; urine analysis; and testing for liver and kidney function, antinuclearantibodies, complement levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate revealed no abnormalities.

The patient started hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and methotrexate 25 mg weekly along with strict photoprotection measures, including wearing photoprotective clothing and avoiding sunlight during the most intense hours of the day.

Linear lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis to consider in patients with a blaschkolinear eruption.7 Although the clinical manifestations of BLE and linear lichen planus are similar, they differ histopathologically. One study found that only 33.3% of patients (6/18) who clinically presented with blaschkolinear eruptions were correctly diagnosed before histologic examination.7 Visualization of the adnexa as well as the superficial and deep vascular plexuses is paramount in distinguishing between linear lichen planus and BLE; linear lichen planus does not have perivascular and periadnexal infiltration, while BLE does. Thus, in our experience, a punch biopsy—rather than a shave biopsy—should be performed to access the deeper layers of the skin.

Because these 2 entities have noteworthy differences in their management, prognosis, and long-term follow-up, accurate diagnosis is critical. To start, BLE is treated with the use of photoprotection, whereas linear lichen planus is commonly treated with phototherapy. Given the potential for forms of CCLE to progress to SLE, serial monitoring is indicated in patients with BLE. As the risk for progression to SLE is highest in the first 3 years after diagnosis, a review of systems and laboratory testing should occur every 2 to 3 months in the first year after diagnosis (sooner if the disease presentation is more severe).9 Also, treatment with hydroxychloroquine likely delays transformation to SLE and is important in the early management of BLE.10 On the other hand, linear lichen planus tends to self-resolve without progression to systemic involvement, warranting limited follow-up.9

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus typically manifests in childhood, but it also can be seen in adults, such as in our patient. Adult-onset BLE is rare but may be underrecognized or underreported in the literature.11 However, dermatologists should consider it in the differential diagnosis for any patient with a blaschkolinear eruption, as establishing the correct diagnosis is key to ensuring prompt and effective treatment for this rare inflammatory condition.

To the Editor:

Chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CCLE) is an inflammatory condition with myriad cutaneous manifestations. Most forms of CCLE have the potential to progress to systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE).1

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus (BLE) is an exceedingly rare subtype of cutaneous lupus erythematosus that usually manifests during childhood as linear plaques along the lines of Blaschko.2,3 Under normal conditions, Blaschko lines are not noticeable; they correspond to the direction of ectodermal cell migration during cutaneous embryogenesis.4,5 The embryonic cells travel ventrolaterally, forming a V-shaped pattern on the back, an S-shaped pattern on the trunk, and an hourglass-shaped pattern on the face with several perpendicular intersections near the mouth and nose.6 During their migration, the cells are susceptible to somatic mutations and clonal expansion, resulting in a monoclonal population of genetically heterogenous cells. This phenomenon is known as somatic mosaicism and may lead to an increased susceptibility to an array of congenital and inflammatory dermatoses, such as cutaneous lupus erythematosus.4 Blaschkolinear entities tend to manifest in a unilateral distribution following exposure to a certain environmental trigger, such as trauma, viral illness, or UV radiation, although a trigger is not always present.7 We report a case of BLE manifesting on the head and neck in an adult patient.

A 46-year-old man presented with a pruritic rash of 3 months’ duration on the right cheek that extended inferiorly to the right upper chest. He had a medical history of well-controlled psoriasis, and he denied any antecedent trauma, fevers, chills, arthralgia, or night sweats. There had been no improvement with mometasone ointment 0.1% applied daily for 2 months as prescribed by his primary care provider. Physical examination revealed indurated, red-brown, atrophic plaques in a blaschkolinear distribution around the nose, right upper jaw, right side of the neck, and right upper chest (Figure, A).

Histopathology of punch biopsies from the right jaw and right upper chest showed an atrophic epidermis with scattered dyskeratotic keratinocytes and vacuolar alteration of the basal cell layer. A superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytic infiltrate was observed in both biopsies. Staining with Verhoeff-van Gieson elastin and periodic acid–Schiff highlighted prominent basement membrane thickening and loss of elastic fibers in the superficial dermis. These findings favored a diagnosis of CCLE, and the clinical blaschkolinear distribution of the rash led to our specific diagnosis of BLE. Laboratory workup for SLE including a complete blood cell count; urine analysis; and testing for liver and kidney function, antinuclearantibodies, complement levels, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate revealed no abnormalities.

The patient started hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily and methotrexate 25 mg weekly along with strict photoprotection measures, including wearing photoprotective clothing and avoiding sunlight during the most intense hours of the day.

Linear lichen planus is an important differential diagnosis to consider in patients with a blaschkolinear eruption.7 Although the clinical manifestations of BLE and linear lichen planus are similar, they differ histopathologically. One study found that only 33.3% of patients (6/18) who clinically presented with blaschkolinear eruptions were correctly diagnosed before histologic examination.7 Visualization of the adnexa as well as the superficial and deep vascular plexuses is paramount in distinguishing between linear lichen planus and BLE; linear lichen planus does not have perivascular and periadnexal infiltration, while BLE does. Thus, in our experience, a punch biopsy—rather than a shave biopsy—should be performed to access the deeper layers of the skin.

Because these 2 entities have noteworthy differences in their management, prognosis, and long-term follow-up, accurate diagnosis is critical. To start, BLE is treated with the use of photoprotection, whereas linear lichen planus is commonly treated with phototherapy. Given the potential for forms of CCLE to progress to SLE, serial monitoring is indicated in patients with BLE. As the risk for progression to SLE is highest in the first 3 years after diagnosis, a review of systems and laboratory testing should occur every 2 to 3 months in the first year after diagnosis (sooner if the disease presentation is more severe).9 Also, treatment with hydroxychloroquine likely delays transformation to SLE and is important in the early management of BLE.10 On the other hand, linear lichen planus tends to self-resolve without progression to systemic involvement, warranting limited follow-up.9

Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus typically manifests in childhood, but it also can be seen in adults, such as in our patient. Adult-onset BLE is rare but may be underrecognized or underreported in the literature.11 However, dermatologists should consider it in the differential diagnosis for any patient with a blaschkolinear eruption, as establishing the correct diagnosis is key to ensuring prompt and effective treatment for this rare inflammatory condition.

- Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the association with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort of 1088 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1335-1341. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10272.x

- Requena C, Torrelo A, de Prada I, et al. Linear childhood cutaneous lupus erythematosus following Blaschko lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:618-620. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00588.x

- Lim D, Hatami A, Kokta V, et al. Linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in children-report of two cases and review of the literature: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313x20979206. doi:10.1177/2050313X20979206

- Jin H, Zhang G, Zhou Y, et al. Old lines tell new tales: Blaschko linear lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:291-306. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.014

- Yu S, Yu H-S. A patient with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus along Blaschko lines: implications for the role of keratinocytes in lupus erythematosus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2016;34:144-147. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2015.12.002

- Kouzak SS, Mendes MST, Costa IMC. Cutaneous mosaicisms: concepts, patterns and classifications. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:507-517. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132015

- Liu W, Vano-Galvan S, Liu J-W, et al. Pigmented linear discoid lupus erythematosus following the lines of Blaschko: a retrospective study of a Chinese series. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:359-365. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_341_19

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

- Curtiss P, Walker AM, Chong BF. A systematic review of the progression of cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2022:13:866319. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.866319

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

- Milosavljevic K, Fibeger E, Virata AR. A case of linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a 55-year-old woman. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:E921495. doi:10.12659/AJCR.921495

- Grönhagen CM, Fored CM, Granath F, et al. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus and the association with systemic lupus erythematosus: a population-based cohort of 1088 patients in Sweden. Br J Dermatol. 2011;164:1335-1341. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10272.x

- Requena C, Torrelo A, de Prada I, et al. Linear childhood cutaneous lupus erythematosus following Blaschko lines. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:618-620. doi:10.1046/j.1468-3083.2002.00588.x

- Lim D, Hatami A, Kokta V, et al. Linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in children-report of two cases and review of the literature: a case report. SAGE Open Med Case Rep. 2020;8:2050313x20979206. doi:10.1177/2050313X20979206

- Jin H, Zhang G, Zhou Y, et al. Old lines tell new tales: Blaschko linear lupus erythematosus. Autoimmun Rev. 2016;15:291-306. doi:10.1016/j.autrev.2015.11.014

- Yu S, Yu H-S. A patient with subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus along Blaschko lines: implications for the role of keratinocytes in lupus erythematosus. Dermatologica Sinica. 2016;34:144-147. doi:10.1016/j.dsi.2015.12.002

- Kouzak SS, Mendes MST, Costa IMC. Cutaneous mosaicisms: concepts, patterns and classifications. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:507-517. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20132015

- Liu W, Vano-Galvan S, Liu J-W, et al. Pigmented linear discoid lupus erythematosus following the lines of Blaschko: a retrospective study of a Chinese series. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:359-365. doi:10.4103/ijdvl.IJDVL_341_19

- O’Brien JC, Chong BF. Not just skin deep: systemic disease involvement in patients with cutaneous lupus. J Invest Dermatol Symp Proc. 2017;18:S69-S74. doi:10.1016/j.jisp.2016.09.001

- Curtiss P, Walker AM, Chong BF. A systematic review of the progression of cutaneous lupus to systemic lupus erythematosus. Front Immunol. 2022:13:866319. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2022.866319

- Okon LG, Werth VP. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: diagnosis and treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27:391-404. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.07.008

- Milosavljevic K, Fibeger E, Virata AR. A case of linear cutaneous lupus erythematosus in a 55-year-old woman. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21:E921495. doi:10.12659/AJCR.921495

Practice Points

- Blaschkolinear lupus erythematosus (BLE), an exceedingly rare subtype of chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus, usually presents during childhood as linear plaques along the lines of Blaschko.

- It is important to consider linear lichen planus in patients with a blaschkolinear eruption, as the clinical manifestations are similar but there are differences in histopathology, management, prognosis, and long-term follow-up.

- Serial monitoring is indicated in patients with BLE given the potential for progression to systemic lupus erythematosus, which may be delayed with early use of hydroxychloroquine.

Pedunculated Tumor on the Posterior Neck

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

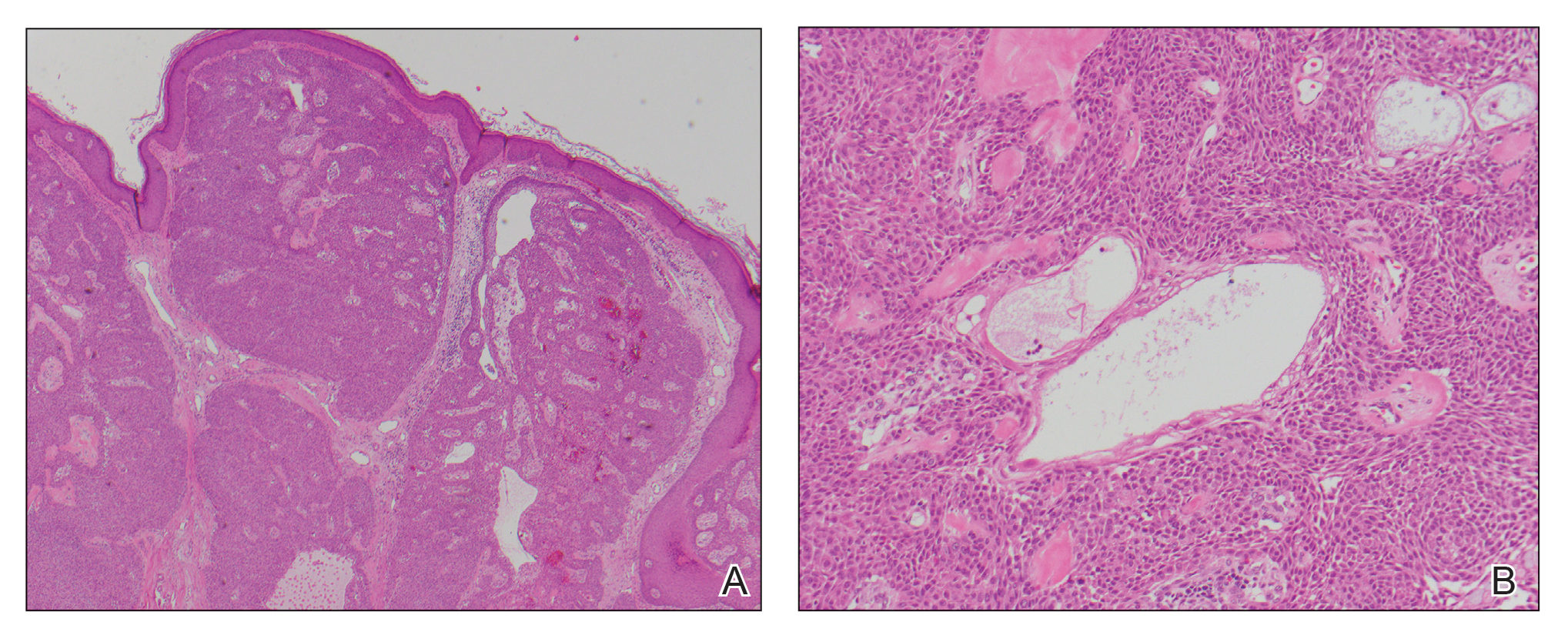

A biopsy of the nodule showed a large, fungating, well-circumscribed, multilobulated neoplasm composed of primarily monotonous eosinophilic cells in a background of keloidal stroma (Figure). There was a minority population of small, monotonous, clear cells within the lobules, and no glandular structures were noted. Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. MART-1/Melan-A and S-100 stains were negative, consistent with a diagnosis of benign nodular hidradenoma.

Nodular hidradenoma (also known as acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, clear cell hidradenoma, and eccrine sweat gland adenoma) is a benign adnexal tumor of the apocrine or eccrine glands.1,2 Nodular hidradenoma can arise at any cutaneous site but most commonly arises on the head and anterior portion of the trunk and rarely on the extremities.2 It presents as a solitary nodular, cystic, or pedunculated mass that can reach up to several centimeters in diameter.2,3 Nodular hidradenoma more commonly affects women compared to men with a ratio of 1.7 to 1 and commonly presents between the third and fifth decades of life, with an average age at presentation of 37.2 years.2,4 There can be associated skin changes, including smoothening, thickening, ulceration, and bluish discoloration. Dermoscopy commonly shows a pinkish homogenous area that extends throughout the entire lesion. This homogenous area less commonly can be bluish, brownish, or pink-blue. Most nodular hidradenomas also can exhibit vascularization, with arborizing telangiectases, polymorphous atypical vessels, and linear irregular vessels being most common; however, this is not specific to nodular hidradenoma.3 Occasionally, tumors can drain serous or hemorrhagic fluid. Nodular hidradenoma commonly is a slow-growing tumor.5 Rapid increase in tumor size can be indicative of malignant transformation, hemorrhage into the tumor, or trauma to the area.2

Histologically, nodular hidradenoma consists of a circumscribed, nonencapsulated, multilobular tumor commonly found in the dermis and sometimes extending into the subcutaneous tissue. There usually is no epidermal attachment, and the overlying epidermis largely is normal. The tumor consists of large multilobulated areas of epithelial cells, tubular lamina, and large cystic areas filled with homogenous eosinophilic material.1 It notably is composed of 2 epithelial cell types: (1) fusiform cells with elongated vesicular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm, and (2) large polygonal cells with round eccentric nuclei and eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive cytoplasm that washes away during fixation, giving the appearance of clear cells.5 Both types of cells are small, monotonous, and void of mitosis or dyskeratosis. Although there can be ducts with apocrine secretion present within the lobulated tumor, they are not consistently found. Due to the varying features that are neither mandatory nor consistent to arrive at this diagnosis, some dermatopathologists view the term hidradenoma as a catch-all term that includes several different types of benign sweat gland tumors. Some authors divide the terminology into apocrine hidradenoma and eccrine hidradenoma based on whether the tumor is composed of solely clear mucinous cells, or poroid and cuticular cells, respectively.

Although nodular hidradenoma classically is a benign tumor, total surgical excision is recommended due to the rare risk for malignant transformation. Rarely, longstanding hidradenomas can metastasize to lymph nodes, bone, or viscera; in these instances, metastatic hidradenoma has a 5-year survival rate of 30%. Recurrence may occur in tumors that are inadequately excised, and the rate of recurrence is estimated to be approximately 10% of surgically excised tumors.5 However, utilization of Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of nodular hidradenoma is associated with a reduced recurrence rate.6

Keloids present as painful, sometimes pruritic, raised scars that extend beyond the boundary of the initial injury, commonly arising on the shoulder, upper arm, and chest. Histopathology reveals nodules of thick hyalinized collagen bundles, keloidal collagen with mucinous ground substance, and few fibroblasts.7

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the skin most commonly presents on the face and scalp as a nodular, rapidly growing, round to oval lesion that is flesh colored to reddish purple in a patient with history of renal cell carcinoma.8 Histopathology shows clusters of atypical, nucleated clear cells surrounded by chicken wire vasculature.8,9

Verruca vulgaris is caused by human papillomavirus and most commonly occurs on the hands and feet. It presents as a pink to white, sessile lesion with a verrucous surface and exophytic growths. Histopathology shows acanthosis; hypergranulosis; exophytic projections with a fibrovascular core; inward cupping of the rete ridges; and koilocytes, which are cells with an eccentric, raisinlike nucleus and vacuolated cytoplasm in the granular layer of the epidermis.10

Similar to nodular hidradenoma, nodular melanoma most commonly presents on the head and neck as a symmetric, elevated, amelanotic nodule, but in contrast to nodular hidradenoma, it typically is confined to a smaller diameter.11 Histologically, it is characterized by sheets of atypical, commonly epithelioid melanocytes with a lack of maturation and brisk mitotic activity extending through the epidermis and dermis with lateral extension limited to less than 3 rete ridges.12

- Patterson JW, Weedon D. Tumors of cutaneous appendages. In: Patterson JW, Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:951-1016.

- Ngo N, Susa M, Nakagawa T, et al. Malignant transformation of nodular hidradenoma in the lower leg. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11:298-304. doi:10.1159/000489255

- Zaballos P, Gómez-Martín I, Martin JM, et al. Dermoscopy of adnexal tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:397-412. doi:10.1016/j .det.2018.05.007

- Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 12:15-20. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70002-3

- Stratigos AJ, Olbricht S, Kwan TH, et al. Nodular hidradenoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:387-391. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04173.x

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Lee JY-Y, Yang C-C, Chao S-C, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:379-384. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00006

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Jaitly V, Jahan-Tigh R, Belousova T, et al. Case report and literature review of nodular hidradenoma, a rare adnexal tumor that mimics breast carcinoma, in a 20-year-old woman. Lab Med. 2019;50:320-325. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmy084

- Betz SJ. HPV-related papillary lesions of the oral mucosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:80-90. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01003-7

- Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:311-318. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.369

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40. doi:10.1038 /modpathol.3800508

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

A biopsy of the nodule showed a large, fungating, well-circumscribed, multilobulated neoplasm composed of primarily monotonous eosinophilic cells in a background of keloidal stroma (Figure). There was a minority population of small, monotonous, clear cells within the lobules, and no glandular structures were noted. Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. MART-1/Melan-A and S-100 stains were negative, consistent with a diagnosis of benign nodular hidradenoma.

Nodular hidradenoma (also known as acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, clear cell hidradenoma, and eccrine sweat gland adenoma) is a benign adnexal tumor of the apocrine or eccrine glands.1,2 Nodular hidradenoma can arise at any cutaneous site but most commonly arises on the head and anterior portion of the trunk and rarely on the extremities.2 It presents as a solitary nodular, cystic, or pedunculated mass that can reach up to several centimeters in diameter.2,3 Nodular hidradenoma more commonly affects women compared to men with a ratio of 1.7 to 1 and commonly presents between the third and fifth decades of life, with an average age at presentation of 37.2 years.2,4 There can be associated skin changes, including smoothening, thickening, ulceration, and bluish discoloration. Dermoscopy commonly shows a pinkish homogenous area that extends throughout the entire lesion. This homogenous area less commonly can be bluish, brownish, or pink-blue. Most nodular hidradenomas also can exhibit vascularization, with arborizing telangiectases, polymorphous atypical vessels, and linear irregular vessels being most common; however, this is not specific to nodular hidradenoma.3 Occasionally, tumors can drain serous or hemorrhagic fluid. Nodular hidradenoma commonly is a slow-growing tumor.5 Rapid increase in tumor size can be indicative of malignant transformation, hemorrhage into the tumor, or trauma to the area.2

Histologically, nodular hidradenoma consists of a circumscribed, nonencapsulated, multilobular tumor commonly found in the dermis and sometimes extending into the subcutaneous tissue. There usually is no epidermal attachment, and the overlying epidermis largely is normal. The tumor consists of large multilobulated areas of epithelial cells, tubular lamina, and large cystic areas filled with homogenous eosinophilic material.1 It notably is composed of 2 epithelial cell types: (1) fusiform cells with elongated vesicular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm, and (2) large polygonal cells with round eccentric nuclei and eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive cytoplasm that washes away during fixation, giving the appearance of clear cells.5 Both types of cells are small, monotonous, and void of mitosis or dyskeratosis. Although there can be ducts with apocrine secretion present within the lobulated tumor, they are not consistently found. Due to the varying features that are neither mandatory nor consistent to arrive at this diagnosis, some dermatopathologists view the term hidradenoma as a catch-all term that includes several different types of benign sweat gland tumors. Some authors divide the terminology into apocrine hidradenoma and eccrine hidradenoma based on whether the tumor is composed of solely clear mucinous cells, or poroid and cuticular cells, respectively.

Although nodular hidradenoma classically is a benign tumor, total surgical excision is recommended due to the rare risk for malignant transformation. Rarely, longstanding hidradenomas can metastasize to lymph nodes, bone, or viscera; in these instances, metastatic hidradenoma has a 5-year survival rate of 30%. Recurrence may occur in tumors that are inadequately excised, and the rate of recurrence is estimated to be approximately 10% of surgically excised tumors.5 However, utilization of Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of nodular hidradenoma is associated with a reduced recurrence rate.6

Keloids present as painful, sometimes pruritic, raised scars that extend beyond the boundary of the initial injury, commonly arising on the shoulder, upper arm, and chest. Histopathology reveals nodules of thick hyalinized collagen bundles, keloidal collagen with mucinous ground substance, and few fibroblasts.7

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the skin most commonly presents on the face and scalp as a nodular, rapidly growing, round to oval lesion that is flesh colored to reddish purple in a patient with history of renal cell carcinoma.8 Histopathology shows clusters of atypical, nucleated clear cells surrounded by chicken wire vasculature.8,9

Verruca vulgaris is caused by human papillomavirus and most commonly occurs on the hands and feet. It presents as a pink to white, sessile lesion with a verrucous surface and exophytic growths. Histopathology shows acanthosis; hypergranulosis; exophytic projections with a fibrovascular core; inward cupping of the rete ridges; and koilocytes, which are cells with an eccentric, raisinlike nucleus and vacuolated cytoplasm in the granular layer of the epidermis.10

Similar to nodular hidradenoma, nodular melanoma most commonly presents on the head and neck as a symmetric, elevated, amelanotic nodule, but in contrast to nodular hidradenoma, it typically is confined to a smaller diameter.11 Histologically, it is characterized by sheets of atypical, commonly epithelioid melanocytes with a lack of maturation and brisk mitotic activity extending through the epidermis and dermis with lateral extension limited to less than 3 rete ridges.12

The Diagnosis: Nodular Hidradenoma

A biopsy of the nodule showed a large, fungating, well-circumscribed, multilobulated neoplasm composed of primarily monotonous eosinophilic cells in a background of keloidal stroma (Figure). There was a minority population of small, monotonous, clear cells within the lobules, and no glandular structures were noted. Neither cytological nor architectural atypia were evident. MART-1/Melan-A and S-100 stains were negative, consistent with a diagnosis of benign nodular hidradenoma.

Nodular hidradenoma (also known as acrospiroma, solid-cystic hidradenoma, clear cell hidradenoma, and eccrine sweat gland adenoma) is a benign adnexal tumor of the apocrine or eccrine glands.1,2 Nodular hidradenoma can arise at any cutaneous site but most commonly arises on the head and anterior portion of the trunk and rarely on the extremities.2 It presents as a solitary nodular, cystic, or pedunculated mass that can reach up to several centimeters in diameter.2,3 Nodular hidradenoma more commonly affects women compared to men with a ratio of 1.7 to 1 and commonly presents between the third and fifth decades of life, with an average age at presentation of 37.2 years.2,4 There can be associated skin changes, including smoothening, thickening, ulceration, and bluish discoloration. Dermoscopy commonly shows a pinkish homogenous area that extends throughout the entire lesion. This homogenous area less commonly can be bluish, brownish, or pink-blue. Most nodular hidradenomas also can exhibit vascularization, with arborizing telangiectases, polymorphous atypical vessels, and linear irregular vessels being most common; however, this is not specific to nodular hidradenoma.3 Occasionally, tumors can drain serous or hemorrhagic fluid. Nodular hidradenoma commonly is a slow-growing tumor.5 Rapid increase in tumor size can be indicative of malignant transformation, hemorrhage into the tumor, or trauma to the area.2

Histologically, nodular hidradenoma consists of a circumscribed, nonencapsulated, multilobular tumor commonly found in the dermis and sometimes extending into the subcutaneous tissue. There usually is no epidermal attachment, and the overlying epidermis largely is normal. The tumor consists of large multilobulated areas of epithelial cells, tubular lamina, and large cystic areas filled with homogenous eosinophilic material.1 It notably is composed of 2 epithelial cell types: (1) fusiform cells with elongated vesicular nuclei and basophilic cytoplasm, and (2) large polygonal cells with round eccentric nuclei and eosinophilic, periodic acid–Schiff–positive cytoplasm that washes away during fixation, giving the appearance of clear cells.5 Both types of cells are small, monotonous, and void of mitosis or dyskeratosis. Although there can be ducts with apocrine secretion present within the lobulated tumor, they are not consistently found. Due to the varying features that are neither mandatory nor consistent to arrive at this diagnosis, some dermatopathologists view the term hidradenoma as a catch-all term that includes several different types of benign sweat gland tumors. Some authors divide the terminology into apocrine hidradenoma and eccrine hidradenoma based on whether the tumor is composed of solely clear mucinous cells, or poroid and cuticular cells, respectively.

Although nodular hidradenoma classically is a benign tumor, total surgical excision is recommended due to the rare risk for malignant transformation. Rarely, longstanding hidradenomas can metastasize to lymph nodes, bone, or viscera; in these instances, metastatic hidradenoma has a 5-year survival rate of 30%. Recurrence may occur in tumors that are inadequately excised, and the rate of recurrence is estimated to be approximately 10% of surgically excised tumors.5 However, utilization of Mohs micrographic surgery for excision of nodular hidradenoma is associated with a reduced recurrence rate.6

Keloids present as painful, sometimes pruritic, raised scars that extend beyond the boundary of the initial injury, commonly arising on the shoulder, upper arm, and chest. Histopathology reveals nodules of thick hyalinized collagen bundles, keloidal collagen with mucinous ground substance, and few fibroblasts.7

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma to the skin most commonly presents on the face and scalp as a nodular, rapidly growing, round to oval lesion that is flesh colored to reddish purple in a patient with history of renal cell carcinoma.8 Histopathology shows clusters of atypical, nucleated clear cells surrounded by chicken wire vasculature.8,9

Verruca vulgaris is caused by human papillomavirus and most commonly occurs on the hands and feet. It presents as a pink to white, sessile lesion with a verrucous surface and exophytic growths. Histopathology shows acanthosis; hypergranulosis; exophytic projections with a fibrovascular core; inward cupping of the rete ridges; and koilocytes, which are cells with an eccentric, raisinlike nucleus and vacuolated cytoplasm in the granular layer of the epidermis.10

Similar to nodular hidradenoma, nodular melanoma most commonly presents on the head and neck as a symmetric, elevated, amelanotic nodule, but in contrast to nodular hidradenoma, it typically is confined to a smaller diameter.11 Histologically, it is characterized by sheets of atypical, commonly epithelioid melanocytes with a lack of maturation and brisk mitotic activity extending through the epidermis and dermis with lateral extension limited to less than 3 rete ridges.12

- Patterson JW, Weedon D. Tumors of cutaneous appendages. In: Patterson JW, Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:951-1016.

- Ngo N, Susa M, Nakagawa T, et al. Malignant transformation of nodular hidradenoma in the lower leg. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11:298-304. doi:10.1159/000489255

- Zaballos P, Gómez-Martín I, Martin JM, et al. Dermoscopy of adnexal tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:397-412. doi:10.1016/j .det.2018.05.007

- Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 12:15-20. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70002-3

- Stratigos AJ, Olbricht S, Kwan TH, et al. Nodular hidradenoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:387-391. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04173.x

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Lee JY-Y, Yang C-C, Chao S-C, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:379-384. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00006

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Jaitly V, Jahan-Tigh R, Belousova T, et al. Case report and literature review of nodular hidradenoma, a rare adnexal tumor that mimics breast carcinoma, in a 20-year-old woman. Lab Med. 2019;50:320-325. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmy084

- Betz SJ. HPV-related papillary lesions of the oral mucosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:80-90. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01003-7

- Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:311-318. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.369

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40. doi:10.1038 /modpathol.3800508

- Patterson JW, Weedon D. Tumors of cutaneous appendages. In: Patterson JW, Weedon D. Weedon’s Skin Pathology. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2020:951-1016.

- Ngo N, Susa M, Nakagawa T, et al. Malignant transformation of nodular hidradenoma in the lower leg. Case Rep Oncol. 2018;11:298-304. doi:10.1159/000489255

- Zaballos P, Gómez-Martín I, Martin JM, et al. Dermoscopy of adnexal tumors. Dermatol Clin. 2018;36:397-412. doi:10.1016/j .det.2018.05.007

- Hernández-Pérez E, Cestoni-Parducci R. Nodular hidradenoma and hidradenocarcinoma: a 10-year review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985; 12:15-20. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70002-3

- Stratigos AJ, Olbricht S, Kwan TH, et al. Nodular hidradenoma. Dermatol Surg. 1998;24:387-391. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.1998.tb04173.x

- Yavel R, Hinshaw M, Rao V, et al. Hidradenomas and a hidradenocarcinoma of the scalp managed using Mohs micrographic surgery and a multidisciplinary approach. Dermatol Surg. 2009;35:273-281. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2008.34424.x

- Lee JY-Y, Yang C-C, Chao S-C, et al. Histopathological differential diagnosis of keloid and hypertrophic scar. Am J Dermatopathol. 2004;26:379-384. doi:10.1097/00000372-200410000-00006

- Ferhatoglu MF, Senol K, Filiz AI. Skin metastasis of renal cell carcinoma: a case report. Cureus. 2018;10:E3614. doi:10.7759/cureus.3614

- Jaitly V, Jahan-Tigh R, Belousova T, et al. Case report and literature review of nodular hidradenoma, a rare adnexal tumor that mimics breast carcinoma, in a 20-year-old woman. Lab Med. 2019;50:320-325. doi:10.1093/labmed/lmy084

- Betz SJ. HPV-related papillary lesions of the oral mucosa: a review. Head Neck Pathol. 2019;13:80-90. doi:10.1007/s12105-019-01003-7

- Kalkhoran S, Milne O, Zalaudek I, et al. Historical, clinical, and dermoscopic characteristics of thin nodular melanoma. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:311-318. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2009.369

- Smoller BR. Histologic criteria for diagnosing primary cutaneous malignant melanoma. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(suppl 2):S34-S40. doi:10.1038 /modpathol.3800508

A 56-year-old man presented with a progressively enlarging lesion on the posterior neck of 8 months’ duration. He reported localized pruritus of the lesion that improved with triamcinolone cream 0.05% and oral hydroxyzine as well as occasional irritation of the mass with oozing of clear fluid and blood. He denied associated pain and constitutional symptoms. Physical examination revealed a 2.5-cm, nodular, pedunculated, rubbery mass with foci of crusting on the central posterior neck. The mass was flesh colored to pink, and no lymphadenopathy was noted on physical examination.

Isolated Scrotal Granular Parakeratosis: An Atypical Clinical Presentation

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

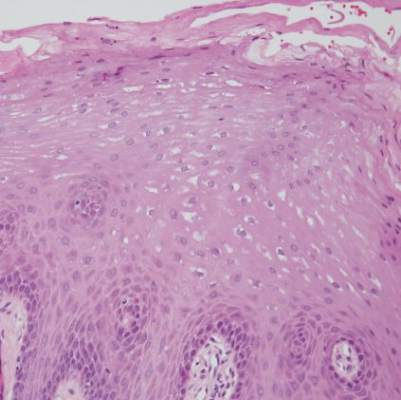

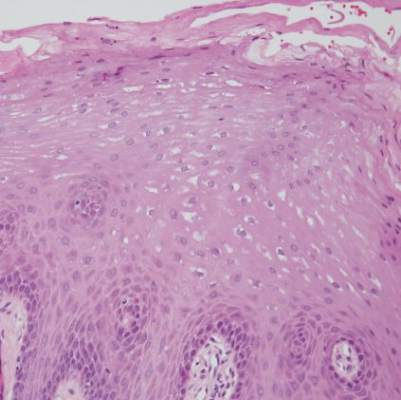

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

To the Editor:

Granular parakeratosis is a rare condition with an unclear etiology that results from a myriad of factors, including exposure to irritants, friction, moisture, and heat. The diagnosis is made based on a distinct histologic reaction pattern that may be protective against the triggers. We present a case of isolated scrotal granular parakeratosis in a patient with compensatory hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy.

A 52-year-old man presented with a 5-year history of a recurrent rash affecting the scrotum. He experienced monthly flares that were exacerbated by inguinal hyperhidrosis. His symptoms included a burning sensation and pruritus followed by superficial desquamation, with gradual yet temporary improvement. His medical history was remarkable for primary axillary and palmoplantar hyperhidrosis, with compensatory inguinal hyperhidrosis after endoscopic thoracic sympathectomy 8 years prior to presentation.

Physical examination revealed a well-demarcated, scaly, erythematous plaque affecting the scrotal skin with sparing of the median raphe, penis, and inguinal folds (Figure 1). There were no other lesions noted in the axillary region or other skin folds.

Prior treatments prescribed by other providers included topical pimecrolimus, antifungal creams, topical corticosteroids, zinc oxide ointment, and daily application of an over-the-counter medicated powder with no resolution.

A punch biopsy performed at the current presentation showed psoriasiform hyperplasia of the epidermis with only a focally diminished granular layer. There was overlying thick parakeratosis and retention of keratohyalin granules (Figure 2). Grocott-Gomori methenamine- silver staining was negative for fungal elements in the sections examined. Clinical history, morphology of the eruption, and histologic features were consistent with granular parakeratosis.

Since the first reported incident of granular parakeratosis of the axilla in 1991,1 granular parakeratosis has been reported in other intertriginous areas, including the inframammary folds, inguinal folds, genitalia, perianal skin, and beneath the abdominal pannus.2 One case study in 1998 reported a patient with isolated involvement of the inguinal region3; however, this presentation is rare.4 This condition has been reported in both sexes and all age groups, including children.5

Granular parakeratosis classically presents as erythematous to brown hyperkeratotic papules that coalesce into plaques.6 It is thought to be a reactive inflammatory condition secondary to aggravating factors such as exposure to heat,7 moisture, and friction; skin occlusion; repeated washing; irritation from external agents; antiperspirants; and use of depilatory creams.8 Histopathology is characteristic and consists of retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum, beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum. Epidermal changes may be varied and include atrophy or hyperplasia.

Murine models have postulated that granular parakeratosis may result from a deficiency in caspase 14, a protease vital to the formation of a well-functioning skin barrier.9 A cornified envelope often is noted in granular parakeratotic cells with no defects in desmosomes and cell membranes, suggesting that the pathogenesis lies within processing of profilaggrin to filaggrin, resulting in a failure to degrade keratohyalin granules and aggregation of keratin filaments.10 Granular parakeratosis is not known to be associated with other medical conditions, but it has been observed in patients receiving chemotherapy for breast11 and ovarian12 carcinomas. In infants with atopic dermatitis, granular parakeratosis was reported in 5 out of 7 cases.6 In our patient with secondary inguinal hyperhidrosis after thoracic sympathectomy, granular parakeratosis may be reactive to excess sweating and friction in the scrotal area.

Granular parakeratosis follows a waxing and waning pattern that may spontaneously resolve without any treatment; it also can follow a protracted course, as in a case with associated facial papules that persisted for 20 years.13 Topical corticosteroids alone or in combination with topical antifungal agents have been used for the treatment of granular parakeratosis with the goal of accelerating resolution.2,14 However, the efficacy of these therapeutic interventions is limited, and no controlled trials are underway. Topical vitamin D analogues15,16 and topical retinoids17 also have been reported with successful outcomes. Spontaneous resolution also has been observed in 2 different cases after previously being unresponsive to topical treatment.18,19 Treatment with Clostridium botulinum toxin A resulted in complete remission of the disease observed at 6-month follow-up. The pharmacologic action of the neurotoxin disrupts the stimulation of eccrine sweat glands, resulting in decreased sweating, a known exacerbating factor of granular parakeratosis.20

In summary, our case represents a unique clinical presentation of granular parakeratosis with classic histopathologic features. A high index of suspicion and a biopsy are vital to arriving at the correct diagnosis.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

- Northcutt AD, Nelson DM, Tschen JA. Axillary granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;24:541-544.

- Burford C. Granular parakeratosis of multiple intertriginous areas. Australas J Dermatol. 2008;49:35-38.

- Mehregan DA, Thomas JE, Mehregan DR. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:495-496.

- Leclerc-Mercier S, Prost-Squarcioni C, Hamel-Teillac D, et al. A case of congenital granular parakeratosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2011;33:531-533.

- Scheinfeld NS, Mones J. Granular parakeratosis: pathologic and clinical correlation of 18 cases of granular parakeratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:863-867.

- Akkaya AD, Oram Y, Aydin O. Infantile granular parakeratosis: cytologic examination of superficial scrapings as an aid to diagnosis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2015;32:392-396.

- Rodríguez G. Axillary granular parakeratosis [in Spanish]. Biomedica. 2002;22:519-523.

- Samrao A, Reis M, Niedt G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: response to calcipotriene and brief review of current therapeutic options. Skinmed. 2010;8:357-359.

- Hoste E, Denecker G, Gilbert B, et al. Caspase-14-deficient mice are more prone to the development of parakeratosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:742-750.

- Metze D, Rutten A. Granular parakeratosis—a unique acquired disorder of keratinization. J Cutan Pathol. 1999;26:339-352.

- Wallace CA, Pichardo RO, Yosipovitch G, et al. Granular parakeratosis: a case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2003;30:332-335.

- Jaconelli L, Doebelin B, Kanitakis J, et al. Granular parakeratosis in a patient treated with liposomal doxorubicin for ovarian carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58(5 suppl 1):S84-S87.

- Reddy IS, Swarnalata G, Mody T. Intertriginous granular parakeratosis persisting for 20 years. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2008;74:405-407.

- Dearden C, al-Nakib W, Andries K, et al. Drug resistant rhinoviruses from the nose of experimentally treated volunteers. Arch Virol. 1989;109:71-81.

- Patel U, Patel T, Skinner RB Jr. Resolution of granular parakeratosis with topical calcitriol. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:997-998.

- Contreras ME, Gottfried LC, Bang RH, et al. Axillary intertriginous granular parakeratosis responsive to topical calcipotriene and ammonium lactate. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:382-383.

- Brown SK, Heilman ER. Granular parakeratosis: resolution with topical tretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47(5 suppl):S279-S280.

- Compton AK, Jackson JM. Isotretinoin as a treatment for axillary granular parakeratosis. Cutis. 2007;80:55-56.

- Webster CG, Resnik KS, Webster GF. Axillary granular parakeratosis: response to isotretinoin. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1997; 37:789-790.

- Ravitskiy L, Heymann WR. Botulinum toxin-induced resolution of axillary granular parakeratosis. Skinmed. 2005;4:118-120.

Practice Points

- Granular parakeratosis can occur in response to triggers such as irritants, friction, hyperhidrosis, and heat.

- Granular parakeratosis can have an atypical presentation; therefore, a high index of suspicion and punch biopsy are vital to arrive at the correct diagnosis.

- Classic histopathology demonstrates retained nuclei and keratohyalin granules within the stratum corneum beneath which there is a retained stratum granulosum.

Oral Leukoedema with Mucosal Desquamation Caused by Toothpaste Containing Sodium Lauryl Sulfate

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented for evaluation of dry mouth and painless peeling of the oral mucosa of 2 months’ duration. She denied any other skin eruptions, dry eyes, vulvar or vaginal pain, or recent hair loss. A recent antinuclear antibodies test was negative. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable and her current medications included multivitamins only.

Oral examination revealed peeling gray-white tissue on the buccal mucosa and mouth floor (Figure 1). After the tissue was manually removed with a tongue blade, the mucosal base was normal in color and texture. The patient denied bruxism, biting of the mucosa or other oral trauma, or use of tobacco or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

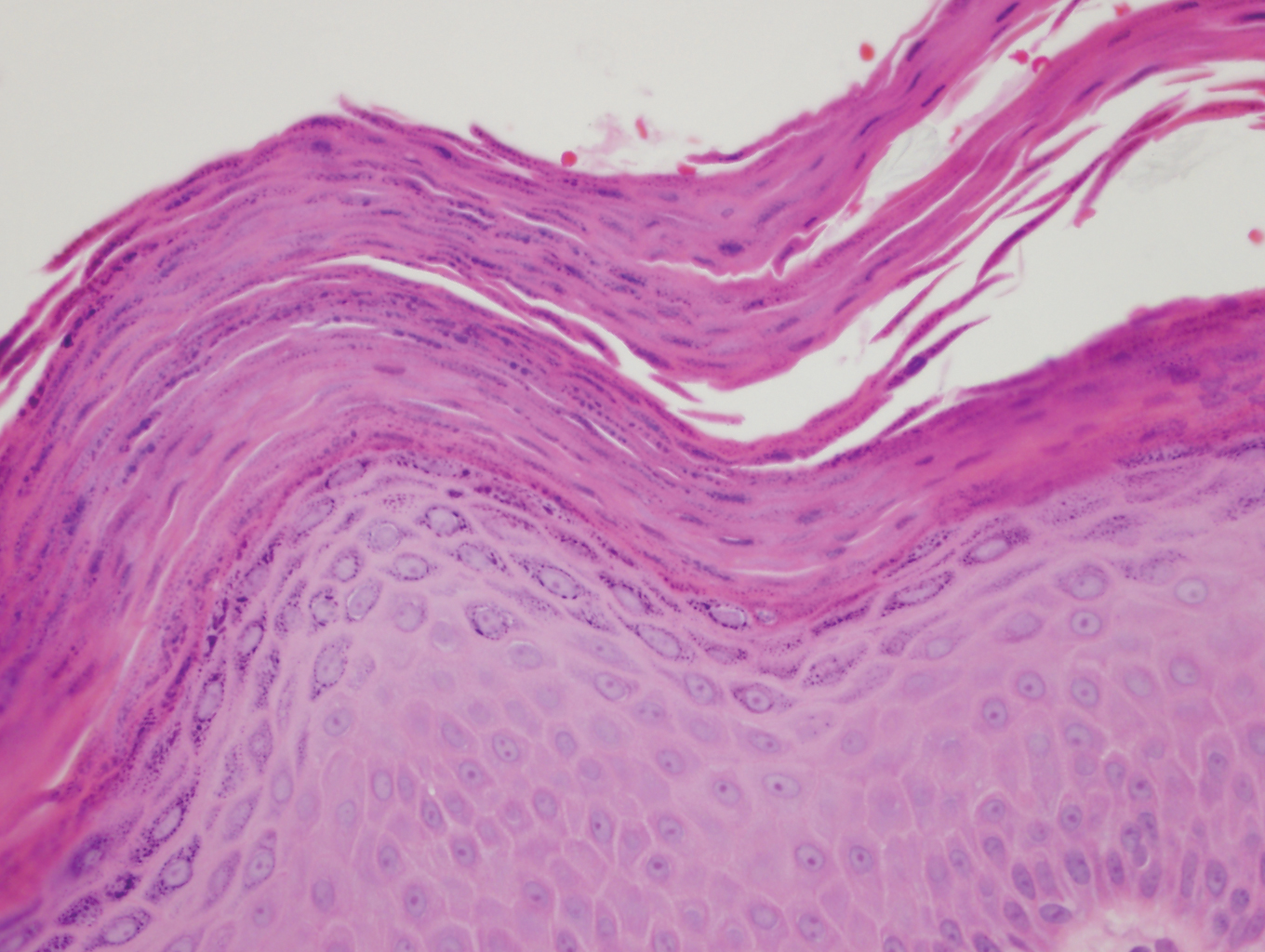

Biopsies from the buccal mucosa were performed to rule out erosive lichen planus and autoimmune blistering disorders. Microscopy revealed parakeratosis and intracellular edema of the mucosa. An intraepithelial cleft at the parakeratotic surface also was present (Figure 2). Minimal inflammation was noted. Fungal staining and direct immunofluorescence were negative.

The gray-white clinical appearance of the oral mucosa resembled leukoedema, but the peeling phenomenon was uncharacteristic. Histologically, leukoedema typically has a parakeratotic and acanthotic epithelium with marked intracellular edema of the spinous layer.1,2 Our patient demonstrated intracellular edema with the additional finding of a superficial intraepithelial cleft. These features were consistent with the observed mucosal sloughing and normal tissue base and led to our diagnosis of leukoedema with mucosal desquamation. This clinical and histologic picture was previously described in another report, but a causative agent could not be identified.2

Because leukoedema can be secondary to chemical or mechanical trauma,3 we hypothesized that the patient’s toothpaste may be the causative agent. After discontinuing use of her regular toothpaste and keeping the rest of her oral hygiene routine unchanged, the patient’s condition resolved within 2 days. The patient could not identify how long she had been using the toothpaste before symptoms began.

Our case as well as a report in the literature suggest that leukoedema with mucosal desquamation may be the result of contact mucositis to dental hygiene products.3 Reports in the dental literature suggest that a possible cause for oral mucosal desquamation is sensitivity to sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS),1,4 an ingredient used in some toothpastes, including the one used by our patient. The patient has since switched to a non–SLS-containing toothpaste and has remained asymptomatic. She was unwilling to reintroduce an SLS-containing product for further evaluation.

Sodium lauryl sulfate is a strong anionic detergent that is commonly used as a foaming agent in dentifrices.4 In products with higher concentrations of SLS, the incidence of oral epithelial desquamation increases. Triclosan has been shown to protect against this irritant phenomenon.5 Interestingly, the SLS-containing toothpaste used by our patient did not contain triclosan.

Although leukoedema and mucosal desquamation induced by oral care products are well-described in the dental literature, it is important for dermatologists to be aware of this phenomenon, as the differential diagnosis includes autoimmune blistering disorders and erosive lichen planus, for which dermatology referral may be requested. Further studies of SLS and other toothpaste ingredients are needed to establish if sloughing of the oral mucosa is primarily caused by SLS or another ingredient.

- Shafer WG, Hine MK, Levy BM. A Textbook of Oral Pathology. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 1983.

- Zegarelli DJ, Silvers DN. Shedding oral mucosa. Cutis. 1994;54:323-326.

- Archard HO, Carlson KP, Stanley HR. Leukoedema of the human oral mucosa. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1971;25:717-728.

- Herlofson BB, Barkvoll P. Desquamative effect of sodium lauryl sulfate on oral mucosa. a preliminary study. Acta Odontol Scand. 1993;51:39-43.

- Skaare A, Eide G, Herlofson B, et al. The effect of toothpaste containing triclosan on oral mucosal desquamation. a model study. J Clin Periodontology. 1996;23:1100-1103.

To the Editor:

A 34-year-old woman presented for evaluation of dry mouth and painless peeling of the oral mucosa of 2 months’ duration. She denied any other skin eruptions, dry eyes, vulvar or vaginal pain, or recent hair loss. A recent antinuclear antibodies test was negative. The patient’s medical history was otherwise unremarkable and her current medications included multivitamins only.

Oral examination revealed peeling gray-white tissue on the buccal mucosa and mouth floor (Figure 1). After the tissue was manually removed with a tongue blade, the mucosal base was normal in color and texture. The patient denied bruxism, biting of the mucosa or other oral trauma, or use of tobacco or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Biopsies from the buccal mucosa were performed to rule out erosive lichen planus and autoimmune blistering disorders. Microscopy revealed parakeratosis and intracellular edema of the mucosa. An intraepithelial cleft at the parakeratotic surface also was present (Figure 2). Minimal inflammation was noted. Fungal staining and direct immunofluorescence were negative.

The gray-white clinical appearance of the oral mucosa resembled leukoedema, but the peeling phenomenon was uncharacteristic. Histologically, leukoedema typically has a parakeratotic and acanthotic epithelium with marked intracellular edema of the spinous layer.1,2 Our patient demonstrated intracellular edema with the additional finding of a superficial intraepithelial cleft. These features were consistent with the observed mucosal sloughing and normal tissue base and led to our diagnosis of leukoedema with mucosal desquamation. This clinical and histologic picture was previously described in another report, but a causative agent could not be identified.2

Because leukoedema can be secondary to chemical or mechanical trauma,3 we hypothesized that the patient’s toothpaste may be the causative agent. After discontinuing use of her regular toothpaste and keeping the rest of her oral hygiene routine unchanged, the patient’s condition resolved within 2 days. The patient could not identify how long she had been using the toothpaste before symptoms began.

Our case as well as a report in the literature suggest that leukoedema with mucosal desquamation may be the result of contact mucositis to dental hygiene products.3 Reports in the dental literature suggest that a possible cause for oral mucosal desquamation is sensitivity to sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS),1,4 an ingredient used in some toothpastes, including the one used by our patient. The patient has since switched to a non–SLS-containing toothpaste and has remained asymptomatic. She was unwilling to reintroduce an SLS-containing product for further evaluation.

Sodium lauryl sulfate is a strong anionic detergent that is commonly used as a foaming agent in dentifrices.4 In products with higher concentrations of SLS, the incidence of oral epithelial desquamation increases. Triclosan has been shown to protect against this irritant phenomenon.5 Interestingly, the SLS-containing toothpaste used by our patient did not contain triclosan.