User login

Are unmatched residency graduates a solution for ‘shrinking shrinks’?

‘Physician associates’ could be used to expand the reach of psychiatry

For many years now, we have been lamenting the shortage of psychiatrists practicing in the United States. At this point, we must identify possible solutions.1,2 Currently, the shortage of practicing psychiatrists in the United States could be as high as 45,000.3 The major problem is that the number of psychiatry residency positions will not increase in the foreseeable future, thus generating more psychiatrists is not an option.

Medicare pays about $150,000 per residency slot per year. To solve the mental health access problem, $27 billion (45,000 x $150,000 x 4 years)* would be required from Medicare, which is not feasible.4 The national average starting salary for psychiatrists from 2018-2019 was about $273,000 (much lower in academic institutions), according to Merritt Hawkins, the physician recruiting firm. That salary is modest, compared with those offered in other medical specialties. For this reason, many graduates choose other lucrative specialties. And we know that increasing the salaries of psychiatrists alone would not lead more people to choose psychiatry. On paper, it may say they work a 40-hour week, but they end up working 60 hours a week.

To make matters worse, family medicine and internal medicine doctors generally would rather not deal with people with mental illness and do “cherry-picking and lemon-dropping.” While many patients present to primary care with mental health issues, lack of time and education in psychiatric disorders and treatment hinder these physicians. In short, the mental health field cannot count on primary care physicians.

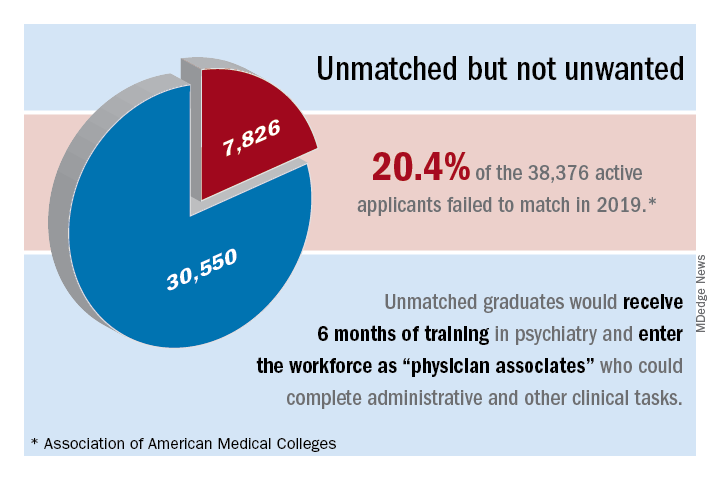

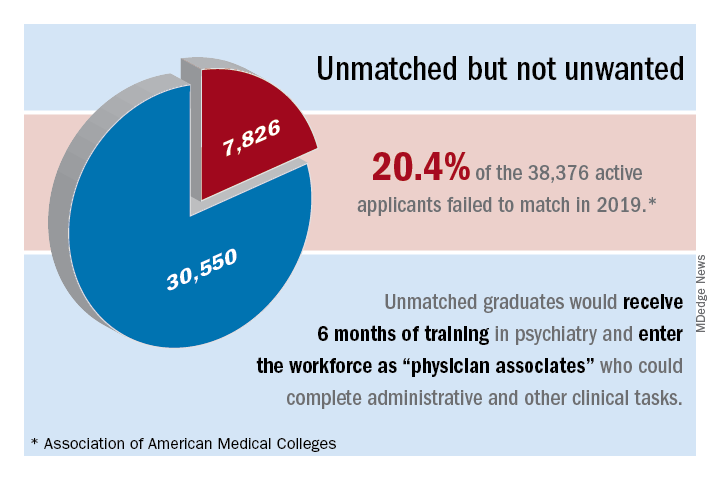

Meanwhile, there are thousands of unmatched residency graduates. In light of those realities, perhaps psychiatry residency programs could provide these unmatched graduates with 6 months of training and use them to supplement the workforce. These medical doctors, or “physician associates,” could be paired with a few psychiatrists to do clinical and administrative work. With one in four individuals having mental health issues, and more and more people seeking help because of increasing awareness and the benefits that accompanied the Affordable Care Act (ACA), physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists so that they can deliver better care to more people. We must take advantage of these two trends: The surge in unmatched graduates and “shrinking shrinks,” or the decline in the psychiatric workforce pool. (The Royal College of Physicians has established a category of clinicians called physician associates,5 but they are comparable to physician assistants in the United States. As you will see, the construct I am proposing is different.)

The current landscape

Currently, psychiatrists are under a lot of pressure to see a certain number of patients. Patients consistently complain that psychiatrists spend a maximum of 15 minutes with them, that the visits are interrupted by phone calls, and that they are not being heard and helped. Burnout, a silent epidemic among physicians, is relatively prevalent in psychiatry.6 Hence, some psychiatrists are reducing their hours and retiring early. Psychiatry has the third-oldest workforce, with 59% of current psychiatrists aged 55 years or older.7 A better pay/work ratio and work/life balance would enable psychiatrists to enjoy more fulfilling careers.

Many psychiatrists are spending a lot of their time in research, administration, and the classroom. In addition to those issues, the United States currently has a broken mental health care system.8 Finally, the medical practice landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, and those changes undermine both the effectiveness and well-being of clinicians.

The historical landscape

Some people proudly refer to the deinstitutionalization of mental asylums and state mental hospitals in the United States. But where have these patients gone? According to a U.S. Justice Department report, 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in U.S. federal and state prisons and county jails in 2013.9 In addition, 4,751,400 adults in 2013 were on probation or parole. The percentages of inmates in state and federal prisons and local jails with a psychiatric diagnosis were 56%, 45%, and 64%, respectively.

I work at the Maryland correctional institutions, part of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. One thing that I consistently hear from several correctional officers is “had these inmates received timely help and care, they wouldn’t have ended up behind bars.” Because of the criminalization of mental illness, in 44 states, the number of people with mental illness is higher in a jail or prison than in the largest state psychiatric hospital, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. We have to be responsible for many of the inmates currently in correctional facilities for committing crimes related to mental health problems. In Maryland, a small state, there are 30,000 inmates in jails, and state and federal prison. The average cost of a meal is $1.36, thus $1.36 x 3 meals x 30,000 inmates = $122,400.00 for food alone for 1 day – this average does not take other expenses into account. By using money and manpower wisely and taking care of individuals’ mental health problems before they commit crimes, better outcomes could be achieved.

I used to work for MedOptions Inc. doing psychiatry consults at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists and nurse practitioners, especially in the suburbs and rural areas, those patients could not be seen in a timely manner even for their 3-month routine follow-ups. As my colleagues and I have written previously, many elderly individuals with major neurocognitive disorders are not on the Food and Drug Administration–approved cognitive enhancers, such as donepezil, galantamine, and memantine.10 Instead, those patients are on benzodiazepines, which are associated with cognitive impairments, and increased risk of pneumonia and falls. Benzodiazepines also can cause and/or worsen disinhibited behavior. Also, in those settings, crisis situations often are addressed days to weeks later because of the doctor shortage. This situation is going to get worse, because this patient population is growing.

Child and geriatric psychiatry shortages

Child and geriatric psychiatrist shortages are even higher than those in general psychiatry.11 Many years of training and low salaries are a few of the reasons some choose not to do a fellowship. These residency graduates would rather join a practice at an attending salary than at a fellow’s salary, which requires an additional 1 to 2 years of training. Student loans of $100,000–$500,000 after residency also discourage some from pursuing fellowship opportunities. We need to consider models such as 2 years of residency with 2 years of a child psychiatry fellowship or 3 years of residency with 1 year of geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Working as an adult attending physician (50% of the time) and concurrently doing a fellowship (50% of the time) while receiving an attending salary might motivate more people to complete a fellowship.

In specialties such as radiology, international medical graduates (IMGs) who have completed residency training in radiology in other countries can complete a radiology fellowship in a particular area for several years and can practice in the United States as board-eligible certified MDs. Likewise, in line with the model proposed here, we could provide unmatched graduates who have no residency training with 3 to 4 years of child psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry training in addition to some adult psychiatry training.

Implementation of such a model might take care of the shortage of child and geriatric psychiatrists. In 2015, there were 56 geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs; 54 positions were filled, and 51 fellows completed training.12 “It appears that a reasonable percentage of IMGs who obtain a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry do not have an intent of pursuing a career in the field,” Marc H. Zisselman, MD, former geriatric psychiatry fellowship director and currently with the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, told me in 2016. These numbers are not at all sufficient to take care of the nation’s unmet need. Hence, implementing alternate strategies is imperative.

Administrative tasks and care

What consumes a psychiatrist’s time and leads to burnout? The answer has to do with administrative tasks at work. Administrative tasks are not an effective use of time for an MD who has spent more than a decade in medical school, residency, and fellowship training. Although electronic medical record (EMR) systems are considered a major advancement, engaging in the process throughout the day is associated with exhaustion.

Many physicians feel that EMRs have slowed them down, and some are not well-equipped to use them in quick and efficient ways. EMRs also have led to physicians making minimal eye contact in interviews with patients. Patients often complain: “I am talking, and the doctor is looking at the computer and typing.” Patients consider this behavior to be unprofessional and rude. In a survey of 57 U.S. physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics, results showed that during the work day, 27% of their time was spent on direct clinical face time with patients and 49.2% was spent on EMR and desk work. While in the examination room with patients, physicians spent 52.9% of their time on direct clinical face time and 37.0% on EMR and desk work. Outside office hours, physicians spend up to 2 hours of personal time each night doing additional computer and other clerical work.13

Several EMR software systems, such as CareLogic, Cerner, Epic,NextGen, PointClickCare, and Sunrise, are used in the United States. The U.S. Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) use the computerized patient record system (CPRS) across the country. VA clinicians find CPRS extremely useful when they move from one VAMC to another. Likewise, hospitals and universities may use one software system such as the CPRS and thus, when clinicians change jobs, they find it hard to adapt to the new system.

Because psychiatrists are wasting a lot of time doing administrative tasks, they might be unable to do a good job with regard to making the right diagnoses and prescribing the best treatments.When I ask patients what are they diagnosed with, they tell me: “It depends on who you ask,” or “I’ve been diagnosed with everything.” This shows that we are not doing a good job or something is not right.

Currently, psychiatrists do not have the time and/or interest to make the right diagnoses and provide adequate psychoeducation for their patients. This also could be attributable to a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, time constraints, cynicism, and apathy. Time constraints also lead to the gross underutilization14 of relapse prevention strategies such as long-acting injectables and medications that can prevent suicide, such as lithium and clozapine.15

Other factors that undermine good care include not participating in continuing medical education (CME) and not staying up to date with the literature. For example, haloperidol continues to be one of the most frequently prescribed (probably, the most common) antipsychotic, although it is clearly neurotoxic16,17 and other safer options are available.18 Board certification and maintenance of certification (MOC) are not synonymous with good clinical practice. Many physicians are finding it hard to complete daily documentation, let alone time for MOC. For a variety of reasons, many are not maintaining certification, and this number is likely to increase. Think about how much time is devoted to the one-to-one interview with the patient and direct patient care during the 15-minute medical check appointment and the hour-long new evaluation. In some clinics, psychiatrists are asked to see more than 25 patients in 4 hours. Some U.S.-based psychiatrists see 65 inpatients and initiate 10 new evaluations in a single day. Under those kinds of time constraints, how can we provide quality care?

A model that would address the shortage

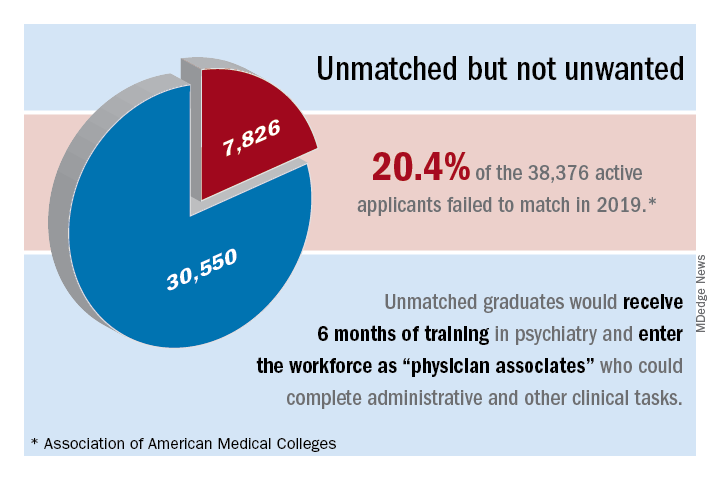

Overall, 7,826 PGY-1 applicants were unmatched in 2019, according to data from the 2019 Main Residency Match.19 Psychiatry residency programs could give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training (arbitrary duration) in psychiatry, which is not at all difficult with the program modules that are available.20 We could use them as physician associates as a major contributor to our workforce to complete administrative and other clinical tasks.

Administrative tasks are not necessarily negative, as all psychiatrists have done administrative tasks as medical students, residents, and fellows. However, at this point, administrative tasks are not an effective use of a psychiatrist’s time. Those physician associates could be paired with two to three psychiatrists to do administrative tasks (for making daytime and overnight phone calls; handling prescriptions, prior authorizations, and medication orders, especially over-the-counter and comfort medications in the inpatient units; doing chart reviews; ordering and checking laboratory tests; collecting collateral information from previous clinicians and records; printing medication education pamphlets; faxing; corresponding with insurance companies/utilization review; performing documentation; billing; and taking care of other clinical and administrative paperwork).

In addition, physician associates could collect information using rating scales such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire for measurement-based care21 and Geriatric Depression Scale, both of which are currently not used in psychiatric practice because of time constraints and lack of manpower. Keep in mind that these individuals are medical doctors and could do a good job with these kinds of tasks. Most of them already have clinical experience in the United States and know the health care system. These MDs could conduct an initial interview (what medical students, residents, and fellows do) and present to the attending psychiatrist. Psychiatrists could then focus on the follow-up interview; diagnoses and treatment; major medical decision making, including shared decision making (patients feel that they are not part of the treatment plan); and seeing more patients, which is a more effective use of their time. This training would give these physician associates a chance to work as doctors and make a living. These MDs have completed medical school training after passing Medical College Admission Test – equivalent exams in their countries. They have passed all steps of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination and have received Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates certification. Some have even completed residency programs in their home countries.

Some U.S. states already have implemented these kinds of programs. In Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri,22,23 legislators have passed laws allowing unmatched graduates who have not completed a residency program to work in medically underserved areas with a collaborating physician. These physicians must directly supervise the new doctors for at least a month before they can see patients on their own. Another proposal that has been suggested to address the psychiatrist shortage is employing physician assistants to provide care.24-26

The model proposed here is comparable to postdoctoral fellow-principal investigator and resident-attending collaborative work. At hospitals, a certified nurse assistant helps patients with health care needs under the supervision of a nurse. Similarly, a physician associate could help a psychiatrist under his or her supervision. In the Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, where I worked previously, for example, nurses dictate and prepare discharge summaries for the attending physician with whom they work. These are the kinds of tasks that physician associates could do as well.

The wait time to get a new evaluation with a psychiatrist is enormous. The policy is that a new patient admitted to an inpatient unit must be seen within 24 hours. With this model, the physician associates could see patients within a few hours, take care of their most immediate needs, take a history and conduct a physical, and write an admission note for the attending psychiatrist to sign. Currently, the outpatient practice is so busy that psychiatrists do not have the time to read the discharge summaries of patients referred to them after a recent hospitalization, which often leads to poor aftercare. The physician associates could read the discharge summaries and provide pertinent information to the attending psychiatrists.

In the inpatient units and emergency departments, nurses and social workers see patients before the attending physician, present patient information to the attending psychiatrist, and document their findings. It is redundant for the physician to write the same narrative again. Rather, the physician could add an addendum to the nurse’s or social worker’s notes and sign off. This would save a lot of time.

Numerous well-designed studies support the adoption of collaborative care models as one means of providing quality psychiatric care to larger populations.27,28 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is currently training 3,500 psychiatrists in collaborative care through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative.29,30 Despite this training and the services provided by the nurse practitioners and physician assistants, the shortage of psychiatrists has not been adequately addressed. Hence, we need to think outside the box to find other potential pragmatic solutions.

Simply increasing the hours of work or the number of nurse practitioners or physician assistants already in practice is not going to solve the problem completely. The model proposed here and previously31 is likely to improve the quality of care that we now provide. This model should not be seen as exploiting these unmatched medical graduates and setting up a two-tiered health care system. The salary for these physicians would be a small percentage (5%-10%; these are arbitrary percentages) from the reimbursement of the attending psychiatrist. This model would not affect the salary of the attending psychiatrists; with this model, they would be able to see 25%-50% more patients (again, arbitrary percentages) with the help and support from these physician associates.

Potential barriers to implementation

There could be inherent barriers and complications to implementation of this model that are difficult to foresee at this point. Nurse practitioners (222,000 plus) and physician assistants (83,000 plus) have a fixed and structured curriculum, have national examining boards and national organizations with recertification requirements, and are licensed as independent practitioners, at least as far as CME is concerned.

Physician associates would need a standardized curriculum and examinations to validate what they have studied and learned. This process might be an important part of the credentialing of these individuals, as well as evaluation of cultural competency. If this model is to successfully lead to formation of a specific clinical group, it might need its own specific identity, national organization, national standards of competency, national certification and recertification processes, and national conference and CME or at least a subsection in a national behavioral and medical health organization, such as the APA or the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

It would be desirable to “field test” the physician associate concept to clarify implementation difficulties, including the ones described above, that could arise. The cost of implementation of this program should not be of much concern; the 6-month training could be on a volunteer basis, or a small stipend might be paid by graduate medical education funding. This model could prove to be rewarding long term, save trillions of health care dollars, and allow us to provide exceptional and timely care.

Conclusion

The 2020 Mental Health America annual State of Mental Health in America report found that more than 70% of youth with severe major depressive disorder were in need of treatment in 2017. The percentage of adults with any mental illness who did not receive treatment stood at about 57.2%.32 Meanwhile, from 1999 through 2014, the age-adjusted suicide rate in the United States increased 24%.33 More individuals are seeking help because of increased awareness.34,35 In light of the access to services afforded by the ACA, physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists and enable them to deliver better care to more people. We would not necessarily have to use the term “physician associate” and could generate better terminologies later. In short, let’s tap into the pools of unmatched graduates and shrinking shrinks! If this model is successful, it could be used in other specialties and countries. The stakes for our patients have never been higher.

References

1. Bishop TF et al. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1271-7.

2. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: Causes and solutions. 2017. Washington: National Council for Behavioral Health.

3. Satiani A et al. Psychiatric Serv. 2018;69:710-3.

4. Carlat D. Psychiatric Times. 2010 Aug 3;27(8).

5. McCartney M. BMJ. 2017;359:j5022.

6. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 5;15:103-11.

7. Merritt Hawkins. “The silent shortage: A white paper examining supply, demand and recruitment trends in psychiatry.” 2018.

8. Sederer LI and Sharfstein SS. JAMA. 2014 Sep 24;312:1195-6.

9. James DJ and Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. 2006 Sep. U.S. Justice Department, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report.

10. Koola MM et al. J Geriatr Care Res. 2018;5(2):57-67.

11. Buckley PF and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2016;15:23-4.

12. American Medical Association Database. Open Residency and Fellowship Positions.

13. Sinsky C et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-60.

14. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2017 Mar. 16(3):19-20,47,e1.

15. Koola MM and Sebastian J. HSOA J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2016;(2):1-11.

16. Nasrallah HA and Chen AT. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017 Aug;29(3):195-202.

17. Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2013 Jul;7-8.

18. Chen AT and Nasrallah HA. Schizophr Res. 2019 Jun;208:1-7.

19. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, 2019.

20. Masters KJ. J Physician Assist Educ. 2015 Sep;26(3):136-43.

21. Koola MM et al. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-90.

22. “New Missouri licensing offers ‘Band-Aid’ for physician shortages.” Kansas City Business Journal. Updated 2017 May 16.

23. “After earning an MD, she’s headed back to school – to become a nurse.” STAT. 2016 Nov 8.

24. Keizer TB and Trangle MA. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):691-4.

25. Miller JG and Peterson DJ. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):685-6.

26. Smith MS. Curr Psychiatr. 2019 Sep;18(9):17-24.

27. Osofsky HJ et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;40(5):747-54.

28. Dreier-Wolfgramm A et al. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017 May;50(Suppl 2):68-77.

29. Huang H and Barkil-Oteo A. Psychosomatics. 2015 Nov-Dec;56(6):658-61.

30. Raney L et al. Fam Syst Health. 2014 Jun;32(2):147-8.

31. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2016 Dec. 15(12):33-4.

32. Mental Health America. State of Mental Health in America 2020.

33. Curtin SC et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2016 Apr;(241):1-8.

34. Kelly DL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):167-8.

35. Miller JP and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2015;14(12):45-6.

Dr. Koola is an associate professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. His main area of interest is novel therapeutic discovery in the treatment of schizophrenia. He has a particular interest in improving the health care delivery system for people with psychiatric illness. Dr. Koola declared no conflicts of interest. He can be reached at maju.koola@stonybrook.edu.

*This commentary was updated 2/2/2020.

‘Physician associates’ could be used to expand the reach of psychiatry

‘Physician associates’ could be used to expand the reach of psychiatry

For many years now, we have been lamenting the shortage of psychiatrists practicing in the United States. At this point, we must identify possible solutions.1,2 Currently, the shortage of practicing psychiatrists in the United States could be as high as 45,000.3 The major problem is that the number of psychiatry residency positions will not increase in the foreseeable future, thus generating more psychiatrists is not an option.

Medicare pays about $150,000 per residency slot per year. To solve the mental health access problem, $27 billion (45,000 x $150,000 x 4 years)* would be required from Medicare, which is not feasible.4 The national average starting salary for psychiatrists from 2018-2019 was about $273,000 (much lower in academic institutions), according to Merritt Hawkins, the physician recruiting firm. That salary is modest, compared with those offered in other medical specialties. For this reason, many graduates choose other lucrative specialties. And we know that increasing the salaries of psychiatrists alone would not lead more people to choose psychiatry. On paper, it may say they work a 40-hour week, but they end up working 60 hours a week.

To make matters worse, family medicine and internal medicine doctors generally would rather not deal with people with mental illness and do “cherry-picking and lemon-dropping.” While many patients present to primary care with mental health issues, lack of time and education in psychiatric disorders and treatment hinder these physicians. In short, the mental health field cannot count on primary care physicians.

Meanwhile, there are thousands of unmatched residency graduates. In light of those realities, perhaps psychiatry residency programs could provide these unmatched graduates with 6 months of training and use them to supplement the workforce. These medical doctors, or “physician associates,” could be paired with a few psychiatrists to do clinical and administrative work. With one in four individuals having mental health issues, and more and more people seeking help because of increasing awareness and the benefits that accompanied the Affordable Care Act (ACA), physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists so that they can deliver better care to more people. We must take advantage of these two trends: The surge in unmatched graduates and “shrinking shrinks,” or the decline in the psychiatric workforce pool. (The Royal College of Physicians has established a category of clinicians called physician associates,5 but they are comparable to physician assistants in the United States. As you will see, the construct I am proposing is different.)

The current landscape

Currently, psychiatrists are under a lot of pressure to see a certain number of patients. Patients consistently complain that psychiatrists spend a maximum of 15 minutes with them, that the visits are interrupted by phone calls, and that they are not being heard and helped. Burnout, a silent epidemic among physicians, is relatively prevalent in psychiatry.6 Hence, some psychiatrists are reducing their hours and retiring early. Psychiatry has the third-oldest workforce, with 59% of current psychiatrists aged 55 years or older.7 A better pay/work ratio and work/life balance would enable psychiatrists to enjoy more fulfilling careers.

Many psychiatrists are spending a lot of their time in research, administration, and the classroom. In addition to those issues, the United States currently has a broken mental health care system.8 Finally, the medical practice landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, and those changes undermine both the effectiveness and well-being of clinicians.

The historical landscape

Some people proudly refer to the deinstitutionalization of mental asylums and state mental hospitals in the United States. But where have these patients gone? According to a U.S. Justice Department report, 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in U.S. federal and state prisons and county jails in 2013.9 In addition, 4,751,400 adults in 2013 were on probation or parole. The percentages of inmates in state and federal prisons and local jails with a psychiatric diagnosis were 56%, 45%, and 64%, respectively.

I work at the Maryland correctional institutions, part of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. One thing that I consistently hear from several correctional officers is “had these inmates received timely help and care, they wouldn’t have ended up behind bars.” Because of the criminalization of mental illness, in 44 states, the number of people with mental illness is higher in a jail or prison than in the largest state psychiatric hospital, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. We have to be responsible for many of the inmates currently in correctional facilities for committing crimes related to mental health problems. In Maryland, a small state, there are 30,000 inmates in jails, and state and federal prison. The average cost of a meal is $1.36, thus $1.36 x 3 meals x 30,000 inmates = $122,400.00 for food alone for 1 day – this average does not take other expenses into account. By using money and manpower wisely and taking care of individuals’ mental health problems before they commit crimes, better outcomes could be achieved.

I used to work for MedOptions Inc. doing psychiatry consults at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists and nurse practitioners, especially in the suburbs and rural areas, those patients could not be seen in a timely manner even for their 3-month routine follow-ups. As my colleagues and I have written previously, many elderly individuals with major neurocognitive disorders are not on the Food and Drug Administration–approved cognitive enhancers, such as donepezil, galantamine, and memantine.10 Instead, those patients are on benzodiazepines, which are associated with cognitive impairments, and increased risk of pneumonia and falls. Benzodiazepines also can cause and/or worsen disinhibited behavior. Also, in those settings, crisis situations often are addressed days to weeks later because of the doctor shortage. This situation is going to get worse, because this patient population is growing.

Child and geriatric psychiatry shortages

Child and geriatric psychiatrist shortages are even higher than those in general psychiatry.11 Many years of training and low salaries are a few of the reasons some choose not to do a fellowship. These residency graduates would rather join a practice at an attending salary than at a fellow’s salary, which requires an additional 1 to 2 years of training. Student loans of $100,000–$500,000 after residency also discourage some from pursuing fellowship opportunities. We need to consider models such as 2 years of residency with 2 years of a child psychiatry fellowship or 3 years of residency with 1 year of geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Working as an adult attending physician (50% of the time) and concurrently doing a fellowship (50% of the time) while receiving an attending salary might motivate more people to complete a fellowship.

In specialties such as radiology, international medical graduates (IMGs) who have completed residency training in radiology in other countries can complete a radiology fellowship in a particular area for several years and can practice in the United States as board-eligible certified MDs. Likewise, in line with the model proposed here, we could provide unmatched graduates who have no residency training with 3 to 4 years of child psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry training in addition to some adult psychiatry training.

Implementation of such a model might take care of the shortage of child and geriatric psychiatrists. In 2015, there were 56 geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs; 54 positions were filled, and 51 fellows completed training.12 “It appears that a reasonable percentage of IMGs who obtain a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry do not have an intent of pursuing a career in the field,” Marc H. Zisselman, MD, former geriatric psychiatry fellowship director and currently with the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, told me in 2016. These numbers are not at all sufficient to take care of the nation’s unmet need. Hence, implementing alternate strategies is imperative.

Administrative tasks and care

What consumes a psychiatrist’s time and leads to burnout? The answer has to do with administrative tasks at work. Administrative tasks are not an effective use of time for an MD who has spent more than a decade in medical school, residency, and fellowship training. Although electronic medical record (EMR) systems are considered a major advancement, engaging in the process throughout the day is associated with exhaustion.

Many physicians feel that EMRs have slowed them down, and some are not well-equipped to use them in quick and efficient ways. EMRs also have led to physicians making minimal eye contact in interviews with patients. Patients often complain: “I am talking, and the doctor is looking at the computer and typing.” Patients consider this behavior to be unprofessional and rude. In a survey of 57 U.S. physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics, results showed that during the work day, 27% of their time was spent on direct clinical face time with patients and 49.2% was spent on EMR and desk work. While in the examination room with patients, physicians spent 52.9% of their time on direct clinical face time and 37.0% on EMR and desk work. Outside office hours, physicians spend up to 2 hours of personal time each night doing additional computer and other clerical work.13

Several EMR software systems, such as CareLogic, Cerner, Epic,NextGen, PointClickCare, and Sunrise, are used in the United States. The U.S. Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) use the computerized patient record system (CPRS) across the country. VA clinicians find CPRS extremely useful when they move from one VAMC to another. Likewise, hospitals and universities may use one software system such as the CPRS and thus, when clinicians change jobs, they find it hard to adapt to the new system.

Because psychiatrists are wasting a lot of time doing administrative tasks, they might be unable to do a good job with regard to making the right diagnoses and prescribing the best treatments.When I ask patients what are they diagnosed with, they tell me: “It depends on who you ask,” or “I’ve been diagnosed with everything.” This shows that we are not doing a good job or something is not right.

Currently, psychiatrists do not have the time and/or interest to make the right diagnoses and provide adequate psychoeducation for their patients. This also could be attributable to a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, time constraints, cynicism, and apathy. Time constraints also lead to the gross underutilization14 of relapse prevention strategies such as long-acting injectables and medications that can prevent suicide, such as lithium and clozapine.15

Other factors that undermine good care include not participating in continuing medical education (CME) and not staying up to date with the literature. For example, haloperidol continues to be one of the most frequently prescribed (probably, the most common) antipsychotic, although it is clearly neurotoxic16,17 and other safer options are available.18 Board certification and maintenance of certification (MOC) are not synonymous with good clinical practice. Many physicians are finding it hard to complete daily documentation, let alone time for MOC. For a variety of reasons, many are not maintaining certification, and this number is likely to increase. Think about how much time is devoted to the one-to-one interview with the patient and direct patient care during the 15-minute medical check appointment and the hour-long new evaluation. In some clinics, psychiatrists are asked to see more than 25 patients in 4 hours. Some U.S.-based psychiatrists see 65 inpatients and initiate 10 new evaluations in a single day. Under those kinds of time constraints, how can we provide quality care?

A model that would address the shortage

Overall, 7,826 PGY-1 applicants were unmatched in 2019, according to data from the 2019 Main Residency Match.19 Psychiatry residency programs could give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training (arbitrary duration) in psychiatry, which is not at all difficult with the program modules that are available.20 We could use them as physician associates as a major contributor to our workforce to complete administrative and other clinical tasks.

Administrative tasks are not necessarily negative, as all psychiatrists have done administrative tasks as medical students, residents, and fellows. However, at this point, administrative tasks are not an effective use of a psychiatrist’s time. Those physician associates could be paired with two to three psychiatrists to do administrative tasks (for making daytime and overnight phone calls; handling prescriptions, prior authorizations, and medication orders, especially over-the-counter and comfort medications in the inpatient units; doing chart reviews; ordering and checking laboratory tests; collecting collateral information from previous clinicians and records; printing medication education pamphlets; faxing; corresponding with insurance companies/utilization review; performing documentation; billing; and taking care of other clinical and administrative paperwork).

In addition, physician associates could collect information using rating scales such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire for measurement-based care21 and Geriatric Depression Scale, both of which are currently not used in psychiatric practice because of time constraints and lack of manpower. Keep in mind that these individuals are medical doctors and could do a good job with these kinds of tasks. Most of them already have clinical experience in the United States and know the health care system. These MDs could conduct an initial interview (what medical students, residents, and fellows do) and present to the attending psychiatrist. Psychiatrists could then focus on the follow-up interview; diagnoses and treatment; major medical decision making, including shared decision making (patients feel that they are not part of the treatment plan); and seeing more patients, which is a more effective use of their time. This training would give these physician associates a chance to work as doctors and make a living. These MDs have completed medical school training after passing Medical College Admission Test – equivalent exams in their countries. They have passed all steps of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination and have received Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates certification. Some have even completed residency programs in their home countries.

Some U.S. states already have implemented these kinds of programs. In Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri,22,23 legislators have passed laws allowing unmatched graduates who have not completed a residency program to work in medically underserved areas with a collaborating physician. These physicians must directly supervise the new doctors for at least a month before they can see patients on their own. Another proposal that has been suggested to address the psychiatrist shortage is employing physician assistants to provide care.24-26

The model proposed here is comparable to postdoctoral fellow-principal investigator and resident-attending collaborative work. At hospitals, a certified nurse assistant helps patients with health care needs under the supervision of a nurse. Similarly, a physician associate could help a psychiatrist under his or her supervision. In the Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, where I worked previously, for example, nurses dictate and prepare discharge summaries for the attending physician with whom they work. These are the kinds of tasks that physician associates could do as well.

The wait time to get a new evaluation with a psychiatrist is enormous. The policy is that a new patient admitted to an inpatient unit must be seen within 24 hours. With this model, the physician associates could see patients within a few hours, take care of their most immediate needs, take a history and conduct a physical, and write an admission note for the attending psychiatrist to sign. Currently, the outpatient practice is so busy that psychiatrists do not have the time to read the discharge summaries of patients referred to them after a recent hospitalization, which often leads to poor aftercare. The physician associates could read the discharge summaries and provide pertinent information to the attending psychiatrists.

In the inpatient units and emergency departments, nurses and social workers see patients before the attending physician, present patient information to the attending psychiatrist, and document their findings. It is redundant for the physician to write the same narrative again. Rather, the physician could add an addendum to the nurse’s or social worker’s notes and sign off. This would save a lot of time.

Numerous well-designed studies support the adoption of collaborative care models as one means of providing quality psychiatric care to larger populations.27,28 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is currently training 3,500 psychiatrists in collaborative care through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative.29,30 Despite this training and the services provided by the nurse practitioners and physician assistants, the shortage of psychiatrists has not been adequately addressed. Hence, we need to think outside the box to find other potential pragmatic solutions.

Simply increasing the hours of work or the number of nurse practitioners or physician assistants already in practice is not going to solve the problem completely. The model proposed here and previously31 is likely to improve the quality of care that we now provide. This model should not be seen as exploiting these unmatched medical graduates and setting up a two-tiered health care system. The salary for these physicians would be a small percentage (5%-10%; these are arbitrary percentages) from the reimbursement of the attending psychiatrist. This model would not affect the salary of the attending psychiatrists; with this model, they would be able to see 25%-50% more patients (again, arbitrary percentages) with the help and support from these physician associates.

Potential barriers to implementation

There could be inherent barriers and complications to implementation of this model that are difficult to foresee at this point. Nurse practitioners (222,000 plus) and physician assistants (83,000 plus) have a fixed and structured curriculum, have national examining boards and national organizations with recertification requirements, and are licensed as independent practitioners, at least as far as CME is concerned.

Physician associates would need a standardized curriculum and examinations to validate what they have studied and learned. This process might be an important part of the credentialing of these individuals, as well as evaluation of cultural competency. If this model is to successfully lead to formation of a specific clinical group, it might need its own specific identity, national organization, national standards of competency, national certification and recertification processes, and national conference and CME or at least a subsection in a national behavioral and medical health organization, such as the APA or the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

It would be desirable to “field test” the physician associate concept to clarify implementation difficulties, including the ones described above, that could arise. The cost of implementation of this program should not be of much concern; the 6-month training could be on a volunteer basis, or a small stipend might be paid by graduate medical education funding. This model could prove to be rewarding long term, save trillions of health care dollars, and allow us to provide exceptional and timely care.

Conclusion

The 2020 Mental Health America annual State of Mental Health in America report found that more than 70% of youth with severe major depressive disorder were in need of treatment in 2017. The percentage of adults with any mental illness who did not receive treatment stood at about 57.2%.32 Meanwhile, from 1999 through 2014, the age-adjusted suicide rate in the United States increased 24%.33 More individuals are seeking help because of increased awareness.34,35 In light of the access to services afforded by the ACA, physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists and enable them to deliver better care to more people. We would not necessarily have to use the term “physician associate” and could generate better terminologies later. In short, let’s tap into the pools of unmatched graduates and shrinking shrinks! If this model is successful, it could be used in other specialties and countries. The stakes for our patients have never been higher.

References

1. Bishop TF et al. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1271-7.

2. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: Causes and solutions. 2017. Washington: National Council for Behavioral Health.

3. Satiani A et al. Psychiatric Serv. 2018;69:710-3.

4. Carlat D. Psychiatric Times. 2010 Aug 3;27(8).

5. McCartney M. BMJ. 2017;359:j5022.

6. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 5;15:103-11.

7. Merritt Hawkins. “The silent shortage: A white paper examining supply, demand and recruitment trends in psychiatry.” 2018.

8. Sederer LI and Sharfstein SS. JAMA. 2014 Sep 24;312:1195-6.

9. James DJ and Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. 2006 Sep. U.S. Justice Department, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report.

10. Koola MM et al. J Geriatr Care Res. 2018;5(2):57-67.

11. Buckley PF and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2016;15:23-4.

12. American Medical Association Database. Open Residency and Fellowship Positions.

13. Sinsky C et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-60.

14. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2017 Mar. 16(3):19-20,47,e1.

15. Koola MM and Sebastian J. HSOA J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2016;(2):1-11.

16. Nasrallah HA and Chen AT. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017 Aug;29(3):195-202.

17. Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2013 Jul;7-8.

18. Chen AT and Nasrallah HA. Schizophr Res. 2019 Jun;208:1-7.

19. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, 2019.

20. Masters KJ. J Physician Assist Educ. 2015 Sep;26(3):136-43.

21. Koola MM et al. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-90.

22. “New Missouri licensing offers ‘Band-Aid’ for physician shortages.” Kansas City Business Journal. Updated 2017 May 16.

23. “After earning an MD, she’s headed back to school – to become a nurse.” STAT. 2016 Nov 8.

24. Keizer TB and Trangle MA. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):691-4.

25. Miller JG and Peterson DJ. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):685-6.

26. Smith MS. Curr Psychiatr. 2019 Sep;18(9):17-24.

27. Osofsky HJ et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;40(5):747-54.

28. Dreier-Wolfgramm A et al. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017 May;50(Suppl 2):68-77.

29. Huang H and Barkil-Oteo A. Psychosomatics. 2015 Nov-Dec;56(6):658-61.

30. Raney L et al. Fam Syst Health. 2014 Jun;32(2):147-8.

31. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2016 Dec. 15(12):33-4.

32. Mental Health America. State of Mental Health in America 2020.

33. Curtin SC et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2016 Apr;(241):1-8.

34. Kelly DL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):167-8.

35. Miller JP and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2015;14(12):45-6.

Dr. Koola is an associate professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. His main area of interest is novel therapeutic discovery in the treatment of schizophrenia. He has a particular interest in improving the health care delivery system for people with psychiatric illness. Dr. Koola declared no conflicts of interest. He can be reached at maju.koola@stonybrook.edu.

*This commentary was updated 2/2/2020.

For many years now, we have been lamenting the shortage of psychiatrists practicing in the United States. At this point, we must identify possible solutions.1,2 Currently, the shortage of practicing psychiatrists in the United States could be as high as 45,000.3 The major problem is that the number of psychiatry residency positions will not increase in the foreseeable future, thus generating more psychiatrists is not an option.

Medicare pays about $150,000 per residency slot per year. To solve the mental health access problem, $27 billion (45,000 x $150,000 x 4 years)* would be required from Medicare, which is not feasible.4 The national average starting salary for psychiatrists from 2018-2019 was about $273,000 (much lower in academic institutions), according to Merritt Hawkins, the physician recruiting firm. That salary is modest, compared with those offered in other medical specialties. For this reason, many graduates choose other lucrative specialties. And we know that increasing the salaries of psychiatrists alone would not lead more people to choose psychiatry. On paper, it may say they work a 40-hour week, but they end up working 60 hours a week.

To make matters worse, family medicine and internal medicine doctors generally would rather not deal with people with mental illness and do “cherry-picking and lemon-dropping.” While many patients present to primary care with mental health issues, lack of time and education in psychiatric disorders and treatment hinder these physicians. In short, the mental health field cannot count on primary care physicians.

Meanwhile, there are thousands of unmatched residency graduates. In light of those realities, perhaps psychiatry residency programs could provide these unmatched graduates with 6 months of training and use them to supplement the workforce. These medical doctors, or “physician associates,” could be paired with a few psychiatrists to do clinical and administrative work. With one in four individuals having mental health issues, and more and more people seeking help because of increasing awareness and the benefits that accompanied the Affordable Care Act (ACA), physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists so that they can deliver better care to more people. We must take advantage of these two trends: The surge in unmatched graduates and “shrinking shrinks,” or the decline in the psychiatric workforce pool. (The Royal College of Physicians has established a category of clinicians called physician associates,5 but they are comparable to physician assistants in the United States. As you will see, the construct I am proposing is different.)

The current landscape

Currently, psychiatrists are under a lot of pressure to see a certain number of patients. Patients consistently complain that psychiatrists spend a maximum of 15 minutes with them, that the visits are interrupted by phone calls, and that they are not being heard and helped. Burnout, a silent epidemic among physicians, is relatively prevalent in psychiatry.6 Hence, some psychiatrists are reducing their hours and retiring early. Psychiatry has the third-oldest workforce, with 59% of current psychiatrists aged 55 years or older.7 A better pay/work ratio and work/life balance would enable psychiatrists to enjoy more fulfilling careers.

Many psychiatrists are spending a lot of their time in research, administration, and the classroom. In addition to those issues, the United States currently has a broken mental health care system.8 Finally, the medical practice landscape has changed dramatically in recent years, and those changes undermine both the effectiveness and well-being of clinicians.

The historical landscape

Some people proudly refer to the deinstitutionalization of mental asylums and state mental hospitals in the United States. But where have these patients gone? According to a U.S. Justice Department report, 2,220,300 adults were incarcerated in U.S. federal and state prisons and county jails in 2013.9 In addition, 4,751,400 adults in 2013 were on probation or parole. The percentages of inmates in state and federal prisons and local jails with a psychiatric diagnosis were 56%, 45%, and 64%, respectively.

I work at the Maryland correctional institutions, part of the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services. One thing that I consistently hear from several correctional officers is “had these inmates received timely help and care, they wouldn’t have ended up behind bars.” Because of the criminalization of mental illness, in 44 states, the number of people with mental illness is higher in a jail or prison than in the largest state psychiatric hospital, according to the Treatment Advocacy Center. We have to be responsible for many of the inmates currently in correctional facilities for committing crimes related to mental health problems. In Maryland, a small state, there are 30,000 inmates in jails, and state and federal prison. The average cost of a meal is $1.36, thus $1.36 x 3 meals x 30,000 inmates = $122,400.00 for food alone for 1 day – this average does not take other expenses into account. By using money and manpower wisely and taking care of individuals’ mental health problems before they commit crimes, better outcomes could be achieved.

I used to work for MedOptions Inc. doing psychiatry consults at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities. Because of the shortage of psychiatrists and nurse practitioners, especially in the suburbs and rural areas, those patients could not be seen in a timely manner even for their 3-month routine follow-ups. As my colleagues and I have written previously, many elderly individuals with major neurocognitive disorders are not on the Food and Drug Administration–approved cognitive enhancers, such as donepezil, galantamine, and memantine.10 Instead, those patients are on benzodiazepines, which are associated with cognitive impairments, and increased risk of pneumonia and falls. Benzodiazepines also can cause and/or worsen disinhibited behavior. Also, in those settings, crisis situations often are addressed days to weeks later because of the doctor shortage. This situation is going to get worse, because this patient population is growing.

Child and geriatric psychiatry shortages

Child and geriatric psychiatrist shortages are even higher than those in general psychiatry.11 Many years of training and low salaries are a few of the reasons some choose not to do a fellowship. These residency graduates would rather join a practice at an attending salary than at a fellow’s salary, which requires an additional 1 to 2 years of training. Student loans of $100,000–$500,000 after residency also discourage some from pursuing fellowship opportunities. We need to consider models such as 2 years of residency with 2 years of a child psychiatry fellowship or 3 years of residency with 1 year of geriatric psychiatry fellowship. Working as an adult attending physician (50% of the time) and concurrently doing a fellowship (50% of the time) while receiving an attending salary might motivate more people to complete a fellowship.

In specialties such as radiology, international medical graduates (IMGs) who have completed residency training in radiology in other countries can complete a radiology fellowship in a particular area for several years and can practice in the United States as board-eligible certified MDs. Likewise, in line with the model proposed here, we could provide unmatched graduates who have no residency training with 3 to 4 years of child psychiatry and geriatric psychiatry training in addition to some adult psychiatry training.

Implementation of such a model might take care of the shortage of child and geriatric psychiatrists. In 2015, there were 56 geriatric psychiatry fellowship programs; 54 positions were filled, and 51 fellows completed training.12 “It appears that a reasonable percentage of IMGs who obtain a fellowship in geriatric psychiatry do not have an intent of pursuing a career in the field,” Marc H. Zisselman, MD, former geriatric psychiatry fellowship director and currently with the Einstein Medical Center in Philadelphia, told me in 2016. These numbers are not at all sufficient to take care of the nation’s unmet need. Hence, implementing alternate strategies is imperative.

Administrative tasks and care

What consumes a psychiatrist’s time and leads to burnout? The answer has to do with administrative tasks at work. Administrative tasks are not an effective use of time for an MD who has spent more than a decade in medical school, residency, and fellowship training. Although electronic medical record (EMR) systems are considered a major advancement, engaging in the process throughout the day is associated with exhaustion.

Many physicians feel that EMRs have slowed them down, and some are not well-equipped to use them in quick and efficient ways. EMRs also have led to physicians making minimal eye contact in interviews with patients. Patients often complain: “I am talking, and the doctor is looking at the computer and typing.” Patients consider this behavior to be unprofessional and rude. In a survey of 57 U.S. physicians in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, and orthopedics, results showed that during the work day, 27% of their time was spent on direct clinical face time with patients and 49.2% was spent on EMR and desk work. While in the examination room with patients, physicians spent 52.9% of their time on direct clinical face time and 37.0% on EMR and desk work. Outside office hours, physicians spend up to 2 hours of personal time each night doing additional computer and other clerical work.13

Several EMR software systems, such as CareLogic, Cerner, Epic,NextGen, PointClickCare, and Sunrise, are used in the United States. The U.S. Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) use the computerized patient record system (CPRS) across the country. VA clinicians find CPRS extremely useful when they move from one VAMC to another. Likewise, hospitals and universities may use one software system such as the CPRS and thus, when clinicians change jobs, they find it hard to adapt to the new system.

Because psychiatrists are wasting a lot of time doing administrative tasks, they might be unable to do a good job with regard to making the right diagnoses and prescribing the best treatments.When I ask patients what are they diagnosed with, they tell me: “It depends on who you ask,” or “I’ve been diagnosed with everything.” This shows that we are not doing a good job or something is not right.

Currently, psychiatrists do not have the time and/or interest to make the right diagnoses and provide adequate psychoeducation for their patients. This also could be attributable to a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, time constraints, cynicism, and apathy. Time constraints also lead to the gross underutilization14 of relapse prevention strategies such as long-acting injectables and medications that can prevent suicide, such as lithium and clozapine.15

Other factors that undermine good care include not participating in continuing medical education (CME) and not staying up to date with the literature. For example, haloperidol continues to be one of the most frequently prescribed (probably, the most common) antipsychotic, although it is clearly neurotoxic16,17 and other safer options are available.18 Board certification and maintenance of certification (MOC) are not synonymous with good clinical practice. Many physicians are finding it hard to complete daily documentation, let alone time for MOC. For a variety of reasons, many are not maintaining certification, and this number is likely to increase. Think about how much time is devoted to the one-to-one interview with the patient and direct patient care during the 15-minute medical check appointment and the hour-long new evaluation. In some clinics, psychiatrists are asked to see more than 25 patients in 4 hours. Some U.S.-based psychiatrists see 65 inpatients and initiate 10 new evaluations in a single day. Under those kinds of time constraints, how can we provide quality care?

A model that would address the shortage

Overall, 7,826 PGY-1 applicants were unmatched in 2019, according to data from the 2019 Main Residency Match.19 Psychiatry residency programs could give these unmatched graduates 6 months of training (arbitrary duration) in psychiatry, which is not at all difficult with the program modules that are available.20 We could use them as physician associates as a major contributor to our workforce to complete administrative and other clinical tasks.

Administrative tasks are not necessarily negative, as all psychiatrists have done administrative tasks as medical students, residents, and fellows. However, at this point, administrative tasks are not an effective use of a psychiatrist’s time. Those physician associates could be paired with two to three psychiatrists to do administrative tasks (for making daytime and overnight phone calls; handling prescriptions, prior authorizations, and medication orders, especially over-the-counter and comfort medications in the inpatient units; doing chart reviews; ordering and checking laboratory tests; collecting collateral information from previous clinicians and records; printing medication education pamphlets; faxing; corresponding with insurance companies/utilization review; performing documentation; billing; and taking care of other clinical and administrative paperwork).

In addition, physician associates could collect information using rating scales such as the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire for measurement-based care21 and Geriatric Depression Scale, both of which are currently not used in psychiatric practice because of time constraints and lack of manpower. Keep in mind that these individuals are medical doctors and could do a good job with these kinds of tasks. Most of them already have clinical experience in the United States and know the health care system. These MDs could conduct an initial interview (what medical students, residents, and fellows do) and present to the attending psychiatrist. Psychiatrists could then focus on the follow-up interview; diagnoses and treatment; major medical decision making, including shared decision making (patients feel that they are not part of the treatment plan); and seeing more patients, which is a more effective use of their time. This training would give these physician associates a chance to work as doctors and make a living. These MDs have completed medical school training after passing Medical College Admission Test – equivalent exams in their countries. They have passed all steps of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination and have received Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates certification. Some have even completed residency programs in their home countries.

Some U.S. states already have implemented these kinds of programs. In Arkansas, Kansas, and Missouri,22,23 legislators have passed laws allowing unmatched graduates who have not completed a residency program to work in medically underserved areas with a collaborating physician. These physicians must directly supervise the new doctors for at least a month before they can see patients on their own. Another proposal that has been suggested to address the psychiatrist shortage is employing physician assistants to provide care.24-26

The model proposed here is comparable to postdoctoral fellow-principal investigator and resident-attending collaborative work. At hospitals, a certified nurse assistant helps patients with health care needs under the supervision of a nurse. Similarly, a physician associate could help a psychiatrist under his or her supervision. In the Sheppard Pratt Health System in Baltimore, where I worked previously, for example, nurses dictate and prepare discharge summaries for the attending physician with whom they work. These are the kinds of tasks that physician associates could do as well.

The wait time to get a new evaluation with a psychiatrist is enormous. The policy is that a new patient admitted to an inpatient unit must be seen within 24 hours. With this model, the physician associates could see patients within a few hours, take care of their most immediate needs, take a history and conduct a physical, and write an admission note for the attending psychiatrist to sign. Currently, the outpatient practice is so busy that psychiatrists do not have the time to read the discharge summaries of patients referred to them after a recent hospitalization, which often leads to poor aftercare. The physician associates could read the discharge summaries and provide pertinent information to the attending psychiatrists.

In the inpatient units and emergency departments, nurses and social workers see patients before the attending physician, present patient information to the attending psychiatrist, and document their findings. It is redundant for the physician to write the same narrative again. Rather, the physician could add an addendum to the nurse’s or social worker’s notes and sign off. This would save a lot of time.

Numerous well-designed studies support the adoption of collaborative care models as one means of providing quality psychiatric care to larger populations.27,28 The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is currently training 3,500 psychiatrists in collaborative care through the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative.29,30 Despite this training and the services provided by the nurse practitioners and physician assistants, the shortage of psychiatrists has not been adequately addressed. Hence, we need to think outside the box to find other potential pragmatic solutions.

Simply increasing the hours of work or the number of nurse practitioners or physician assistants already in practice is not going to solve the problem completely. The model proposed here and previously31 is likely to improve the quality of care that we now provide. This model should not be seen as exploiting these unmatched medical graduates and setting up a two-tiered health care system. The salary for these physicians would be a small percentage (5%-10%; these are arbitrary percentages) from the reimbursement of the attending psychiatrist. This model would not affect the salary of the attending psychiatrists; with this model, they would be able to see 25%-50% more patients (again, arbitrary percentages) with the help and support from these physician associates.

Potential barriers to implementation

There could be inherent barriers and complications to implementation of this model that are difficult to foresee at this point. Nurse practitioners (222,000 plus) and physician assistants (83,000 plus) have a fixed and structured curriculum, have national examining boards and national organizations with recertification requirements, and are licensed as independent practitioners, at least as far as CME is concerned.

Physician associates would need a standardized curriculum and examinations to validate what they have studied and learned. This process might be an important part of the credentialing of these individuals, as well as evaluation of cultural competency. If this model is to successfully lead to formation of a specific clinical group, it might need its own specific identity, national organization, national standards of competency, national certification and recertification processes, and national conference and CME or at least a subsection in a national behavioral and medical health organization, such as the APA or the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry.

It would be desirable to “field test” the physician associate concept to clarify implementation difficulties, including the ones described above, that could arise. The cost of implementation of this program should not be of much concern; the 6-month training could be on a volunteer basis, or a small stipend might be paid by graduate medical education funding. This model could prove to be rewarding long term, save trillions of health care dollars, and allow us to provide exceptional and timely care.

Conclusion

The 2020 Mental Health America annual State of Mental Health in America report found that more than 70% of youth with severe major depressive disorder were in need of treatment in 2017. The percentage of adults with any mental illness who did not receive treatment stood at about 57.2%.32 Meanwhile, from 1999 through 2014, the age-adjusted suicide rate in the United States increased 24%.33 More individuals are seeking help because of increased awareness.34,35 In light of the access to services afforded by the ACA, physician associates might ease the workload of psychiatrists and enable them to deliver better care to more people. We would not necessarily have to use the term “physician associate” and could generate better terminologies later. In short, let’s tap into the pools of unmatched graduates and shrinking shrinks! If this model is successful, it could be used in other specialties and countries. The stakes for our patients have never been higher.

References

1. Bishop TF et al. Health Aff. 2016;35(7):1271-7.

2. National Council Medical Director Institute. The psychiatric shortage: Causes and solutions. 2017. Washington: National Council for Behavioral Health.

3. Satiani A et al. Psychiatric Serv. 2018;69:710-3.

4. Carlat D. Psychiatric Times. 2010 Aug 3;27(8).

5. McCartney M. BMJ. 2017;359:j5022.

6. Maslach C and Leiter MP. World Psychiatry. 2016 Jun 5;15:103-11.

7. Merritt Hawkins. “The silent shortage: A white paper examining supply, demand and recruitment trends in psychiatry.” 2018.

8. Sederer LI and Sharfstein SS. JAMA. 2014 Sep 24;312:1195-6.

9. James DJ and Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. 2006 Sep. U.S. Justice Department, Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report.

10. Koola MM et al. J Geriatr Care Res. 2018;5(2):57-67.

11. Buckley PF and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2016;15:23-4.

12. American Medical Association Database. Open Residency and Fellowship Positions.

13. Sinsky C et al. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-60.

14. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2017 Mar. 16(3):19-20,47,e1.

15. Koola MM and Sebastian J. HSOA J Psychiatry Depress Anxiety. 2016;(2):1-11.

16. Nasrallah HA and Chen AT. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017 Aug;29(3):195-202.

17. Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2013 Jul;7-8.

18. Chen AT and Nasrallah HA. Schizophr Res. 2019 Jun;208:1-7.

19. National Resident Matching Program, Results and Data: 2019 Main Residency Match. National Resident Matching Program, Washington, 2019.

20. Masters KJ. J Physician Assist Educ. 2015 Sep;26(3):136-43.

21. Koola MM et al. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2011;199(12):989-90.

22. “New Missouri licensing offers ‘Band-Aid’ for physician shortages.” Kansas City Business Journal. Updated 2017 May 16.

23. “After earning an MD, she’s headed back to school – to become a nurse.” STAT. 2016 Nov 8.

24. Keizer TB and Trangle MA. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):691-4.

25. Miller JG and Peterson DJ. Acad Psychiatry. 2015 Dec;39(6):685-6.

26. Smith MS. Curr Psychiatr. 2019 Sep;18(9):17-24.

27. Osofsky HJ et al. Acad Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;40(5):747-54.

28. Dreier-Wolfgramm A et al. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2017 May;50(Suppl 2):68-77.

29. Huang H and Barkil-Oteo A. Psychosomatics. 2015 Nov-Dec;56(6):658-61.

30. Raney L et al. Fam Syst Health. 2014 Jun;32(2):147-8.

31. Koola MM. Curr Psychiatr. 2016 Dec. 15(12):33-4.

32. Mental Health America. State of Mental Health in America 2020.

33. Curtin SC et al. NCHS Data Brief. 2016 Apr;(241):1-8.

34. Kelly DL et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172(2):167-8.

35. Miller JP and Nasrallah HA. Curr Psychiatr. 2015;14(12):45-6.

Dr. Koola is an associate professor in the department of psychiatry and behavioral health at Stony Brook (N.Y.) University. His main area of interest is novel therapeutic discovery in the treatment of schizophrenia. He has a particular interest in improving the health care delivery system for people with psychiatric illness. Dr. Koola declared no conflicts of interest. He can be reached at maju.koola@stonybrook.edu.

*This commentary was updated 2/2/2020.

Can anti-inflammatory medications improve symptoms and reduce mortality in schizophrenia?

Consider 3 observations:

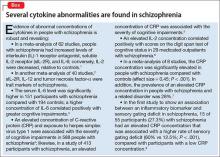

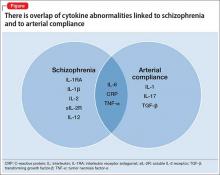

- Evidence is mounting that cytokine abnormalities are present in schizophrenia (Box1-8).

- Reduced arterial compliance (change in volume divided by change in pressure [ΔV/ΔP] in an artery during the cardiac cycle) is an early marker of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and a robust predictor of mortality, and is associated with cytokine abnormalities.

- People with schizophrenia experience increased mortality from CVD.

Taken together, the 3 statements hint at a hypothesis: a common inflammatory process involving cytokine imbalance is associated with symptoms of schizophrenia, reduced arterial compliance, and CVD.

Anti-inflammatory therapeutics that target specific cytokines might both decrease psychiatric symptoms and reduce cardiac mortality in people with schizophrenia. In this article, we (1) highlight the potential role of anti-inflammatory medications in reducing both psychiatric symptoms and cardiac mortality in people with schizophrenia and (2) review the pathophysiological basis of this inflammatory commonality and the evidence for its presence in schizophrenia.

The ‘membrane hypothesis’ of schizophrenia

In this hypothesis, a disturbance in the synthesis and structure of membrane phospholipids results in a subsequent disturbance in the function of neuronal membrane proteins, which might be associated with symptoms and mortality in schizophrenia.9-12 The synaptic vesicle protein synaptophysin, a marker for synaptic density, was found to be decreased in postmortem tissue from the gyrus cinguli in 11 patients with schizophrenia, compared with 13 controls.10 Intracellular phospholipases A2 (inPLA2) act as key enzymes in cell membrane repair and remodeling and in neuroplasticity, neurodevelopment, apoptosis, synaptic pruning, neurodegenerative processes, and neuroinflammation.

In a study, people with first-episode schizophrenia (n = 24) who were drug-naïve or off antipsychotic medication were compared with 25 healthy controls using voxel-based morphometry analysis of T1 high-resolution MRI. inPLA2 activity was increased in the patient group compared with controls; the analysis revealed abnormalities of the frontal and medial temporal cortices, hippocampus, and left-middle and superior temporal gyri in first-episode patients.11 In another study, inPLA2 activity was increased in 35 people with first-episode schizophrenia, compared with 22 controls, and was associated with symptom severity and outcome after 12 weeks of antipsychotic treatment.12

Early CVD mortality in schizophrenia

People with schizophrenia have an elevated rate of CVD compared with the general population; in part, this elevation is linked to magnified risk factors for CVD, including obesity, metabolic syndrome, cigarette smoking, and diabetes13-17; furthermore, most antipsychotics can cause or worsen metabolic syndrome.17

CVD is one of the most common causes of death among people with schizophrenia.17,18 Their life expectancy is reported to be 51 to 61 years—20 to 25 years less than what is seen in the general population.19-21

Arterial compliance in schizophrenia

Reduced arterial compliance has been found to be a robust predictor of atherosclerosis, stroke, and myocardial infarction22-29:

- In 376 subjects who had routine diagnostic coronary angiography associated with coronary stenosis, arterial compliance was reduced significantly—even after controlling for age, sex, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and obesity.24

In a cross-sectional study, 63 male U.S. veterans age 18 to 70 who had a psychiatric diagnosis (16 taking quetiapine, 19 taking risperidone, and 28 treated in the past but off antipsychotics for 2 months) had significantly reduced compliance in thigh- and calf-level arteries than male controls (n = 111), adjusting for body mass index and Framingham Risk Score (FRS). Of the 63 patients, 23 had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder.30 (The FRS is an estimate of a person’s 10-year cardiovascular risk, calculated using age, sex, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein, smoker or not, systolic blood pressure, and whether taking an antihypertensive or not. Compliance was measured using computerized plethysmography). Although not statistically significant, secondary analyses from this data set (n = 77, including men for whom factors for metabolic syndrome were available) showed that calf-level compliance (1.82 vs 2.06 mL) and thigh-level compliance (3.6 vs 4.26 mL; P = .06) were reduced in subjects with schizophrenia, compared with those who had another psychiatric diagnosis.31

- In another study, arterial compliance was significantly reduced in 10 subjects with schizophrenia, compared with 10 healthy controls.32

- Last, reduced total arterial compliance has been shown to be a robust predictor of mortality in older people, compared with reduced local or regional arterial compliance.33

Cytokine abnormalities in arterial compliance