User login

Mental Health Outcomes Among Transgender Veterans and Active-Duty Service Members in the United States: A Systematic Review

According to the United States Transgender Survey, 39% of respondents reported experiencing serious psychological distress (based on the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale) in the past 30 days compared with 5% in the general population.1 Additionally, 40% of respondents attempted suicide in their lifetime, compared with 5% in the general population.1 Almost half of respondents reported being sexually assaulted at some time in their life, and 10% reported being sexually assaulted in the past year.1

Studies have also shown that veterans and active-duty service members experience worse mental health outcomes and are at increased risk for suicide than civilians and nonveterans.2-5 About 1 in 4 active-duty service members meet the criteria for diagnosis of a mental illness.4 Service members were found to have higher rates of probable anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared with the general population.2,6 In 2018, veteran suicide deaths accounted for about 13% of all deaths by suicide in the US even though veterans only accounted for about 7% of the adult population in that year.5,7 Also in 2018, about 17 veterans committed suicide per day.5 According to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, about 18% reported thinking about attempting suicide some time in their lives compared with 4% of the general population.2,3 Additionally, 5% of service members reported previous suicide attempts compared with 0.5% in the general population.2,3 It is clear that transgender individuals, veterans, and service members have certain mental health outcomes that are worse than that of the general population.1-7

Transgender individuals along with LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) individuals have long faced discrimination and unfair treatment in the military.8-11 In the 1920s, the first written policies were established that banned gay men from serving in the military.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) continued these policies until in 1993, the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy was established, which had the façade of being more inclusive for LGB individuals but forced LGB service members to hide their sexual identity and continued the anti-LGBTQ messages that previous policies had created.8,10,11 In 2010, “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” was repealed, which allowed LGB individuals to serve in the military without concealing their sexual orientation and without fear of discharge based on their sexual identity.11 This repeal did not allow transgender individuals to serve their country as the DoD categorized transgender identity as a medical and mental health disorder.8,11

In 2016, the ban on transgender individuals serving in the military was lifted, and service members could no longer be discharged or turned away from joining the military based on gender identity.8,12 However, in 2018, this order was reversed. The new policy stated that new service members must meet requirements and standards of their sex assigned at birth, and individuals with a history of gender dysphoria or those who have received gender-affirming medical or surgical treatment were prohibited to serve in the military.8,13 This policy did not apply to service members who joined before it took effect. Finally, in April 2021, the current policy took effect, permitting transgender individuals to openly serve in the military. The current policy states that service members cannot be discharged or denied reenlistment based on their gender identity and provides support to receive gender-affirming medical care.14 Although transgender individuals are now accepted in military service, there is still much progress needed to promote equity among transgender service members.

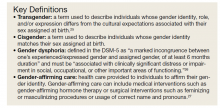

In 2015, according to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, 0.6% of service members identified as transgender, the same percentage as US adults who identify as transgender.2,15 Previous research has shown that the prevalence of gender identity disorder among veterans is higher than that among the general US population.16 Many studies have shown that worse mental health outcomes exist among LGBTQ veterans and service members compared with heterosexual, cisgender veterans and service members.17-24 However, fewer studies have focused solely on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans and active-duty service members, and there exists no current literature review on this topic. In this article, we present data from the existing literature on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. We hypothesize, based on the current literature, that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. Key terms used in this paper are defined in the Key Definitions.25-27

Methods

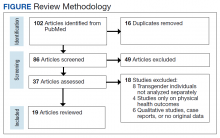

We conducted a systematic review of articles presenting data on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. The National Library of Medicine PubMed database was searched using the following search terms in various combinations: mental health outcomes, transgender, veterans, military, active duty, substance use, and sexual trauma. The literature search was performed in August 2021 and included articles published through July 31, 2021. Methodology, size, demographics, measures, and main findings were extracted from each article. All studies were eligible for inclusion regardless of sample size. Studies that examined the LGBTQ population without separating transgender individuals were excluded. Studies that examined mental health outcomes including, but not limited to, PTSD, depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUDs) in addition to sexual trauma were included. Studies that only examined physical health outcomes were excluded. Qualitative studies, case reports, and papers that did not present original data were excluded (Figure).

Results

Our search resulted in 86 publications. After excluding 65 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 19 studies were included in this review. The Appendix shows the summary of findings from each study, including the study size and results. All studies were conducted in the United States. Most papers used a cross-sectional study design. Most of the studies focused on transgender veterans, but some included data on transgender active-duty service members.

We separated the findings into the following categories based on the variables measured: mental health, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and serious mental illness; suicidality and self-harm; substance use; and military sexual trauma (MST). Many studies overlapped multiple categories.

Mental Health

Most of the studies included reported that transgender veterans have statistically significant worse mental health outcomes compared with cisgender veterans.28-30 In addition, transgender active-duty service members were found to have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender active-duty service members.31 MST and discrimination were associated with worse mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.32,33 One study showed a different result than others and found that transgender older adults with prior military service had higher psychological health-related quality of life and lower depressive symptoms than those without prior military service (P = .02 and .04, respectively).34 Another study compared transgender veterans with active-duty service members and found that transgender veterans reported higher rates of depression (64.6% vs 30.9%; χ2 = 11.68; P = .001) and anxiety (41.3% vs 18.2%; χ2 = 6.54; P = .01) compared with transgender service members.35

Suicidality and Self-harm

Eleven of the 19 studies included measured suicidality and/or self-harm as an outcome. Transgender veterans and active-duty service members were found to have higher odds of suicidality than their cisgender counterparts.16,28,29,31 In addition, transgender veterans may die by suicide at a younger age than cisgender veterans.36 Stigma and gender-related discrimination were found to be associated with suicidal ideation.33,37-39 Transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI).40

Substance Use

Two studies focused on substance use, while 5 other studies included substance use in their measures. One of these 2 studies that focused only on substance use outcomes found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any SUD (7.2% vs 3.9%; P < .001), in addition to specifically cannabis (3.4% vs 1.5%; P < .001), amphetamine (1.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001), and cocaine use disorders (1.5% vs 1.1%; P < .001).41

Another study reported that transgender veterans had lower odds of self-reported alcohol use but had greater odds of having alcohol-related diagnoses compared with cisgender veterans.42 Of the other studies, it was found that a higher percentage of transgender veterans were diagnosed with an SUD compared with transgender active-duty service members, and transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to be diagnosed with alcohol use disorder.29,31 Additionally, rural transgender veterans had increased odds of tobacco use disorder compared with transgender veterans who lived in urban areas.43

Military Sexual Trauma

Five of the studies included examined MST, defined as sexual assault or sexual harassment that is experienced during military service.44 Studies found that 15% to 17% of transgender veterans experienced MST.32,45 Transgender veterans were more likely to report MST than cisgender veterans.28,29 MST was found to be consistently associated with depression and PTSD.32,45 A high percentage (83.9%) of transgender active-duty service members reported experiencing sexual harassment and almost one-third experienced sexual assault.46

Discussion

Outcomes examined in this review included MST, substance use, suicidality, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among transgender active-duty service members and veterans. To our knowledge, no other review on this topic exists. There is a review of the health and well-being of LGBTQ veterans and service members, but a majority of the included studies did not separate transgender individuals from LGB persons.17 This review of transgender individuals showed similar results to the review of LGBTQ individuals.17 This review also presented similar results to previous studies that indicated that transgender individuals in the general population have worse mental health outcomes compared with their cisgender counterparts, in addition to studies that showed that veterans and active-duty service members have worse mental health outcomes compared with civilians and nonveterans.1-5 The population of focus in this review faced a unique set of challenges, being that they belonged to both of these subsets of the population, both of which experienced worse mental health outcomes, according to the literature.

Studies included in our review found that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender veterans and service members.28-31 This outcome was predicted based on previous data collection among transgender individuals, veterans, and active-duty service members. One of the studies included found different results and concluded that prior military service was a protective factor against poorer mental health outcomes.34 This could be, in part, due to veterans’ access to care through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system. It has been found that transgender veterans use VA services at higher rates than the general population of veterans and that barriers to care were found more for medical treatment than for mental health treatment.47 One study found that almost 70% of transgender veterans who used VA services were satisfied with their mental health care.48 In contrast, another study included in our review found that transgender veterans had worse mental health outcomes than transgender service members, possibly showing that even with access to care, the burden of stigma and discrimination worsens mental health over time.31 Although it has been shown that transgender veterans may feel comfortable disclosing their gender identity to their health care professional, many barriers to care have been identified, such as insensitivity and lack of knowledge about transgender care among clinicians.49-51 With this information, it would be useful to ensure proper training for health care professionals on providing gender-affirming care.

Most of the studies also found that transgender veterans and service members had greater odds of suicidal thoughts and events than cisgender veterans and service members.16,28,29,35 On the contrary, transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report NSSI, which could be for various reasons.40 Transgender veterans may report less NSSI but experience it at similar rates, or veteran status may be a protective factor for NSSI.

Very few studies included SUDs in their measurements, but it was found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any drug and alcohol use disorder.29,41 In addition, transgender veterans were more likely than transgender service members to be diagnosed with an SUD, again showing that over time and after time of service, mental health may worsen due to the burden of stigma and discrimination.31 Studies that examined MST found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to report MST, which replicates previous data that found high rates of sexual assault experienced among transgender individuals.1,28,29

There is a lack of literature surrounding transgender veterans and active-duty service members, especially with regard to gender-affirming care provided to these populations. To the best of our knowledge, there exists only one original study that examines the effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.52 Further research in this area is needed, specifically longitudinal studies examining the effects of gender-affirming medical care on various outcomes, including mental health. Few longitudinal studies exist that examine the mental health effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on transgender individuals in the general population.53-60 Most of these studies have shown a significant improvement in parameters of depression and anxiety following hormonal treatment, although long-term large follow-up studies to understand whether these improvements persist over time are missing also in the general population. However, as previously described, transgender veterans and service members are a unique subset of the transgender population and require separate data collection. Hence, further research is required to provide optimal care for this population. In addition, early screening for symptoms of mental illness, substance use, and MST is important to providing optimal care.

Limitations

This review was limited due to the lack of data collected from transgender veterans and service members. The studies included did not allow for standardized comparisons and did not use identical measures. Some papers compared transgender veterans with transgender nonveterans, some transgender veterans and/or service members with cisgender veterans and/or service members, and some transgender veterans with transgender service members. There were some consistent results found across the studies, but some studies showed contradictory results or no significant differences within a certain category. It is difficult to compare such different study designs and various participant populations. Additional research is required to verify and replicate these results.

Conclusions

Although this review was limited due to the lack of consistent study designs in the literature examining the mental health of transgender veterans and active-duty service members, overall results showed that transgender veterans and service members experience worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. With this knowledge and exploring the history of discrimination that this population has faced, improved systems must be put into place to better serve this population and improve health outcomes. Additional research is required to examine the effects of gender-affirming care on mental health among transgender veterans and service members.

1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. December 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.ustranssurvey.org

2. Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Rand Health Q. 2018;8(2):434.

3. Lipari R, Piscopo K, Kroutil LA, Miller GK. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. 2015:1-14. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR2-2014/NSDUH-FRR2-2014.pdf

4. Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):504-513. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. November 2020. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2020/2020-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-11-2020-508.pdf

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

7. Vespa J. Those who SERVED: America’s veterans from World War II to the war on terror. The United States Census Bureau. June 2, 2020. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/acs-43.html

8. Seibert DC, Keller N, Zapor L, Archer H. Military transgender care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(11):764-770. doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000000519

9. Rigby WC. Military penal law: A brief survey of the 1920 revision of the Articles of War. J Crim Law Criminol. 1921;12(1):84.

10. Department of Defense Directive Number 1332.14: Enlisted Administrative Separations. December 21, 1993. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blaw/dodd/corres/pdf/d133214wch1_122193/d133214p.pdf

11. Aford B, Lee SJ. Toward complete inclusion: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender military service members after repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Soc Work. 2016;61(3):257-265. doi:10.1093/sw/sww033

12. Department of Defense Instruction 1300.28: In-Service Transition for Transgender Service Members. June 30, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2016/0616_policy/DoD-Instruction-1300.28.pdf

13. Department of Defense. Directive-type Memorandum (DTM)-19-004 - Military Service by Transgender Persons and Persons with Gender Dysphoria. March 12. 2019. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Policies/2020/03/17/Military-Service-by-Transgender-Persons-and-Persons-with-Gender-Dysphoria

14. US Department of Defense Instruction 1300.28: In-Service Transition for Transgender Service Members. April 30, 2021. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/130028p.pdf

15. Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute; 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

16. Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Shipherd Phd JC, Kauth M, Piegari RI, Bossarte RM. Prevalence of gender identity disorder and suicide risk among transgender veterans utilizing veterans health administration care. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):e27-e32. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301507

17. Mark KM, McNamara KA, Gribble R, et al. The health and well-being of LGBTQ serving and ex-serving personnel: a narrative review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):75-94. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1575190

18. Blosnich J, Foynes MM, Shipherd JC. Health disparities among sexual minority women veterans. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(7):631-636. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.4214

19. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM, Silenzio VM. Suicidal ideation among sexual minority veterans: results from the 2005-2010 Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S44-S47. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300565

20. Blosnich JR, Gordon AJ, Fine MJ. Associations of sexual and gender minority status with health indicators, health risk factors, and social stressors in a national sample of young adults with military experience. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(9):661-667. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.06.001

21. Cochran BN, Balsam K, Flentje A, Malte CA, Simpson T. Mental health characteristics of sexual minority veterans. J Homosex. 2013;60(2-3):419-435. doi:10.1080/00918369.2013.744932

22. Lehavot K, Browne KC, Simpson TL. Examining sexual orientation disparities in alcohol misuse among women veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5):554-562. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.002

23. Scott RL, Lasiuk GC, Norris CM. Depression in lesbian, gay, and bisexual members of the Canadian Armed Forces. LGBT Health. 2016;3(5):366-372. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0050

24. Wang J, Dey M, Soldati L, Weiss MG, Gmel G, Mohler-Kuo M. Psychiatric disorders, suicidality, and personality among young men by sexual orientation. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(8):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.05.001

25. American Psychological Association. Gender. APA Style. September 2019. Updated July 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/gender

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed., American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Deutsch MB. Overview of gender-affirming treatments and procedures. UCSF Transgender Care. June 17, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/overview

28. Brown GR, Jones KT. Health correlates of criminal justice involvement in 4,793 transgender veterans. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):297-305. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0052

29. Brown GR, Jones KT. Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the Veterans Health Administration: a case-control study. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):122-131. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058

30. Downing J, Conron K, Herman JL, Blosnich JR. Transgender and cisgender US veterans have few health differences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1160-1168. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0027

31. Holloway IW, Green D, Pickering C, et al. Mental health and health risk behaviors of active duty sexual minority and transgender service members in the United States military. LGBT Health. 2021;8(2):152-161. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0031

32. Beckman K, Shipherd J, Simpson T, Lehavot K. Military sexual assault in transgender veterans: results from a nationwide survey. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(2):181-190. doi:10.1002/jts.22280

33. Blosnich JR, Marsiglio MC, Gao S, Gordon AJ, Shipherd JC, Kauth M, Brown GR, Fine MJ. Mental health of transgender veterans in US states with and without discrimination and hate crime legal protection. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):534-540. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302981

34. Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, Kim HJ, Sturges AM, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl 1):S63-S71. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw173

35. Hill BJ, Bouris A, Barnett JT, Walker D. Fit to serve? Exploring mental and physical health and well-being among transgender active-duty service members and veterans in the U.S. military. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):4-11. Published 2016 Jan 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0002

36. Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Wojcio S, Jones KT, Bossarte RM. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2000-2009. LGBT Health. 2014;1(4):269-276. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050

37. Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: the role of social support and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

38. Lehavot K, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Factors associated with suicidality among a national sample of transgender veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):507-524. doi:10.1111/sltb.12233

39. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Reger MA, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Current and military-specific gender minority stress factors and their relationship with suicide ideation in transgender veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(1):155-166. doi:10.1111/sltb.12432

40. Aboussouan A, Snow A, Cerel J, Tucker RP. Non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation, and past suicide attempts: Comparison between transgender and gender diverse veterans and non-veterans. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:186-194. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.046

41. Frost MC, Blosnich JR, Lehavot K, Chen JA, Rubinsky AD, Glass JE, Williams EC. Disparities in documented drug use disorders between transgender and cisgender U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients. J Addict Med. 2021;15(4):334-340. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000769

42. Williams EC, Frost MC, Rubinsky AD, et al. Patterns of alcohol use among transgender patients receiving care at the Veterans Health Administration: overall and relative to nontransgender patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021;82(1):132-141. doi:10.15288/jsad.2021.82.132

43. Bukowski LA, Blosnich J, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Brown GR, Gordon AJ. Exploring rural disparities in medical diagnoses among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses utilizing Veterans Health Administration care. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 9):S97-S103. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000745

44. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Military Sexual Trauma. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/mentalhealth/msthome/index.asp

45. Lindsay JA, Keo-Meier C, Hudson S, Walder A, Martin LA, Kauth MR. Mental health of transgender veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who experienced military sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(6):563-567. doi:10.1002/jts.22146

46. Schuyler AC, Klemmer C, Mamey MR, et al. Experiences of sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault during military service among LGBT and Non-LGBT service members. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):257-266. doi:10.1002/jts.22506

47. Shipherd JC, Mizock L, Maguen S, Green KE. Male-to-female transgender veterans and VA health care utilization. Int J Sexual Health. 2012;24(1):78-87. doi:10.1080/19317611.2011.639440

48. Lehavot K, Katon JG, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Transgender veterans’ satisfaction with care and unmet health needs. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 9):S90-S96. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000723

49. Kauth MR, Barrera TL, Latini DM. Lesbian, gay, and transgender veterans’ experiences in the Veterans Health Administration: positive signs and room for improvement. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(2):346-351. doi:10.1037/ser0000232

50. Rosentel K, Hill BJ, Lu C, Barnett JT. Transgender veterans and the Veterans Health Administration: exploring the experiences of transgender veterans in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):108-116. Published 2016 Jun 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0006

51. Dietert M, Dentice D, Keig Z. Addressing the needs of transgender military veterans: better access and more comprehensive care. Transgend Health. 2017;2(1):35-44. Published 2017 Mar 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0040

52. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Blosnich JR, Lehavot K. Hormone therapy, gender affirmation surgery, and their association with recent suicidal ideation and depression symptoms in transgender veterans. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2329-2336. doi:10.1017/S0033291717003853

53. Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients’ psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:65-73. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.029

54. Heylens G, Verroken C, De Cock S, T’Sjoen G, De Cuypere G. Effects of different steps in gender reassignment therapy on psychopathology: a prospective study of persons with a gender identity disorder. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):119-126. doi:10.1111/jsm.12363

55. Fisher AD, Castellini G, Ristori J, et al. Cross-sex hormone treatment and psychobiological changes in transsexual persons: two-year follow-up data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4260-4269. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-1276

56. Aldridge Z, Patel S, Guo B, et al. Long-term effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on depression and anxiety symptoms in transgender people: a prospective cohort study. Andrology. 2021;9(6):1808-1816. doi:10.1111/andr.12884

57. Costantino A, Cerpolini S, Alvisi S, Morselli PG, Venturoli S, Meriggiola MC. A prospective study on sexual function and mood in female-to-male transsexuals during testosterone administration and after sex reassignment surgery. J Sex Marital Ther. 2013;39(4):321-335. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.736920

58. Keo-Meier CL, Herman LI, Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Sharp C, Babcock JC. Testosterone treatment and MMPI-2 improvement in transgender men: a prospective controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):143-156. doi:10.1037/a0037599

59. Turan S‚ , Aksoy Poyraz C, Usta Sag˘lam NG, et al. Alterations in body uneasiness, eating attitudes, and psychopathology before and after cross-sex hormonal treatment in patients with female-to-male gender dysphoria. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(8):2349-2361. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1189-4

60. Oda H, Kinoshita T. Efficacy of hormonal and mental treatments with MMPI in FtM individuals: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):256. Published 2017 Jul 17. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1423-y

According to the United States Transgender Survey, 39% of respondents reported experiencing serious psychological distress (based on the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale) in the past 30 days compared with 5% in the general population.1 Additionally, 40% of respondents attempted suicide in their lifetime, compared with 5% in the general population.1 Almost half of respondents reported being sexually assaulted at some time in their life, and 10% reported being sexually assaulted in the past year.1

Studies have also shown that veterans and active-duty service members experience worse mental health outcomes and are at increased risk for suicide than civilians and nonveterans.2-5 About 1 in 4 active-duty service members meet the criteria for diagnosis of a mental illness.4 Service members were found to have higher rates of probable anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared with the general population.2,6 In 2018, veteran suicide deaths accounted for about 13% of all deaths by suicide in the US even though veterans only accounted for about 7% of the adult population in that year.5,7 Also in 2018, about 17 veterans committed suicide per day.5 According to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, about 18% reported thinking about attempting suicide some time in their lives compared with 4% of the general population.2,3 Additionally, 5% of service members reported previous suicide attempts compared with 0.5% in the general population.2,3 It is clear that transgender individuals, veterans, and service members have certain mental health outcomes that are worse than that of the general population.1-7

Transgender individuals along with LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) individuals have long faced discrimination and unfair treatment in the military.8-11 In the 1920s, the first written policies were established that banned gay men from serving in the military.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) continued these policies until in 1993, the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy was established, which had the façade of being more inclusive for LGB individuals but forced LGB service members to hide their sexual identity and continued the anti-LGBTQ messages that previous policies had created.8,10,11 In 2010, “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” was repealed, which allowed LGB individuals to serve in the military without concealing their sexual orientation and without fear of discharge based on their sexual identity.11 This repeal did not allow transgender individuals to serve their country as the DoD categorized transgender identity as a medical and mental health disorder.8,11

In 2016, the ban on transgender individuals serving in the military was lifted, and service members could no longer be discharged or turned away from joining the military based on gender identity.8,12 However, in 2018, this order was reversed. The new policy stated that new service members must meet requirements and standards of their sex assigned at birth, and individuals with a history of gender dysphoria or those who have received gender-affirming medical or surgical treatment were prohibited to serve in the military.8,13 This policy did not apply to service members who joined before it took effect. Finally, in April 2021, the current policy took effect, permitting transgender individuals to openly serve in the military. The current policy states that service members cannot be discharged or denied reenlistment based on their gender identity and provides support to receive gender-affirming medical care.14 Although transgender individuals are now accepted in military service, there is still much progress needed to promote equity among transgender service members.

In 2015, according to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, 0.6% of service members identified as transgender, the same percentage as US adults who identify as transgender.2,15 Previous research has shown that the prevalence of gender identity disorder among veterans is higher than that among the general US population.16 Many studies have shown that worse mental health outcomes exist among LGBTQ veterans and service members compared with heterosexual, cisgender veterans and service members.17-24 However, fewer studies have focused solely on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans and active-duty service members, and there exists no current literature review on this topic. In this article, we present data from the existing literature on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. We hypothesize, based on the current literature, that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. Key terms used in this paper are defined in the Key Definitions.25-27

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of articles presenting data on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. The National Library of Medicine PubMed database was searched using the following search terms in various combinations: mental health outcomes, transgender, veterans, military, active duty, substance use, and sexual trauma. The literature search was performed in August 2021 and included articles published through July 31, 2021. Methodology, size, demographics, measures, and main findings were extracted from each article. All studies were eligible for inclusion regardless of sample size. Studies that examined the LGBTQ population without separating transgender individuals were excluded. Studies that examined mental health outcomes including, but not limited to, PTSD, depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUDs) in addition to sexual trauma were included. Studies that only examined physical health outcomes were excluded. Qualitative studies, case reports, and papers that did not present original data were excluded (Figure).

Results

Our search resulted in 86 publications. After excluding 65 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 19 studies were included in this review. The Appendix shows the summary of findings from each study, including the study size and results. All studies were conducted in the United States. Most papers used a cross-sectional study design. Most of the studies focused on transgender veterans, but some included data on transgender active-duty service members.

We separated the findings into the following categories based on the variables measured: mental health, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and serious mental illness; suicidality and self-harm; substance use; and military sexual trauma (MST). Many studies overlapped multiple categories.

Mental Health

Most of the studies included reported that transgender veterans have statistically significant worse mental health outcomes compared with cisgender veterans.28-30 In addition, transgender active-duty service members were found to have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender active-duty service members.31 MST and discrimination were associated with worse mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.32,33 One study showed a different result than others and found that transgender older adults with prior military service had higher psychological health-related quality of life and lower depressive symptoms than those without prior military service (P = .02 and .04, respectively).34 Another study compared transgender veterans with active-duty service members and found that transgender veterans reported higher rates of depression (64.6% vs 30.9%; χ2 = 11.68; P = .001) and anxiety (41.3% vs 18.2%; χ2 = 6.54; P = .01) compared with transgender service members.35

Suicidality and Self-harm

Eleven of the 19 studies included measured suicidality and/or self-harm as an outcome. Transgender veterans and active-duty service members were found to have higher odds of suicidality than their cisgender counterparts.16,28,29,31 In addition, transgender veterans may die by suicide at a younger age than cisgender veterans.36 Stigma and gender-related discrimination were found to be associated with suicidal ideation.33,37-39 Transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI).40

Substance Use

Two studies focused on substance use, while 5 other studies included substance use in their measures. One of these 2 studies that focused only on substance use outcomes found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any SUD (7.2% vs 3.9%; P < .001), in addition to specifically cannabis (3.4% vs 1.5%; P < .001), amphetamine (1.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001), and cocaine use disorders (1.5% vs 1.1%; P < .001).41

Another study reported that transgender veterans had lower odds of self-reported alcohol use but had greater odds of having alcohol-related diagnoses compared with cisgender veterans.42 Of the other studies, it was found that a higher percentage of transgender veterans were diagnosed with an SUD compared with transgender active-duty service members, and transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to be diagnosed with alcohol use disorder.29,31 Additionally, rural transgender veterans had increased odds of tobacco use disorder compared with transgender veterans who lived in urban areas.43

Military Sexual Trauma

Five of the studies included examined MST, defined as sexual assault or sexual harassment that is experienced during military service.44 Studies found that 15% to 17% of transgender veterans experienced MST.32,45 Transgender veterans were more likely to report MST than cisgender veterans.28,29 MST was found to be consistently associated with depression and PTSD.32,45 A high percentage (83.9%) of transgender active-duty service members reported experiencing sexual harassment and almost one-third experienced sexual assault.46

Discussion

Outcomes examined in this review included MST, substance use, suicidality, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among transgender active-duty service members and veterans. To our knowledge, no other review on this topic exists. There is a review of the health and well-being of LGBTQ veterans and service members, but a majority of the included studies did not separate transgender individuals from LGB persons.17 This review of transgender individuals showed similar results to the review of LGBTQ individuals.17 This review also presented similar results to previous studies that indicated that transgender individuals in the general population have worse mental health outcomes compared with their cisgender counterparts, in addition to studies that showed that veterans and active-duty service members have worse mental health outcomes compared with civilians and nonveterans.1-5 The population of focus in this review faced a unique set of challenges, being that they belonged to both of these subsets of the population, both of which experienced worse mental health outcomes, according to the literature.

Studies included in our review found that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender veterans and service members.28-31 This outcome was predicted based on previous data collection among transgender individuals, veterans, and active-duty service members. One of the studies included found different results and concluded that prior military service was a protective factor against poorer mental health outcomes.34 This could be, in part, due to veterans’ access to care through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system. It has been found that transgender veterans use VA services at higher rates than the general population of veterans and that barriers to care were found more for medical treatment than for mental health treatment.47 One study found that almost 70% of transgender veterans who used VA services were satisfied with their mental health care.48 In contrast, another study included in our review found that transgender veterans had worse mental health outcomes than transgender service members, possibly showing that even with access to care, the burden of stigma and discrimination worsens mental health over time.31 Although it has been shown that transgender veterans may feel comfortable disclosing their gender identity to their health care professional, many barriers to care have been identified, such as insensitivity and lack of knowledge about transgender care among clinicians.49-51 With this information, it would be useful to ensure proper training for health care professionals on providing gender-affirming care.

Most of the studies also found that transgender veterans and service members had greater odds of suicidal thoughts and events than cisgender veterans and service members.16,28,29,35 On the contrary, transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report NSSI, which could be for various reasons.40 Transgender veterans may report less NSSI but experience it at similar rates, or veteran status may be a protective factor for NSSI.

Very few studies included SUDs in their measurements, but it was found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any drug and alcohol use disorder.29,41 In addition, transgender veterans were more likely than transgender service members to be diagnosed with an SUD, again showing that over time and after time of service, mental health may worsen due to the burden of stigma and discrimination.31 Studies that examined MST found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to report MST, which replicates previous data that found high rates of sexual assault experienced among transgender individuals.1,28,29

There is a lack of literature surrounding transgender veterans and active-duty service members, especially with regard to gender-affirming care provided to these populations. To the best of our knowledge, there exists only one original study that examines the effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.52 Further research in this area is needed, specifically longitudinal studies examining the effects of gender-affirming medical care on various outcomes, including mental health. Few longitudinal studies exist that examine the mental health effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on transgender individuals in the general population.53-60 Most of these studies have shown a significant improvement in parameters of depression and anxiety following hormonal treatment, although long-term large follow-up studies to understand whether these improvements persist over time are missing also in the general population. However, as previously described, transgender veterans and service members are a unique subset of the transgender population and require separate data collection. Hence, further research is required to provide optimal care for this population. In addition, early screening for symptoms of mental illness, substance use, and MST is important to providing optimal care.

Limitations

This review was limited due to the lack of data collected from transgender veterans and service members. The studies included did not allow for standardized comparisons and did not use identical measures. Some papers compared transgender veterans with transgender nonveterans, some transgender veterans and/or service members with cisgender veterans and/or service members, and some transgender veterans with transgender service members. There were some consistent results found across the studies, but some studies showed contradictory results or no significant differences within a certain category. It is difficult to compare such different study designs and various participant populations. Additional research is required to verify and replicate these results.

Conclusions

Although this review was limited due to the lack of consistent study designs in the literature examining the mental health of transgender veterans and active-duty service members, overall results showed that transgender veterans and service members experience worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. With this knowledge and exploring the history of discrimination that this population has faced, improved systems must be put into place to better serve this population and improve health outcomes. Additional research is required to examine the effects of gender-affirming care on mental health among transgender veterans and service members.

According to the United States Transgender Survey, 39% of respondents reported experiencing serious psychological distress (based on the Kessler 6 Psychological Distress Scale) in the past 30 days compared with 5% in the general population.1 Additionally, 40% of respondents attempted suicide in their lifetime, compared with 5% in the general population.1 Almost half of respondents reported being sexually assaulted at some time in their life, and 10% reported being sexually assaulted in the past year.1

Studies have also shown that veterans and active-duty service members experience worse mental health outcomes and are at increased risk for suicide than civilians and nonveterans.2-5 About 1 in 4 active-duty service members meet the criteria for diagnosis of a mental illness.4 Service members were found to have higher rates of probable anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) compared with the general population.2,6 In 2018, veteran suicide deaths accounted for about 13% of all deaths by suicide in the US even though veterans only accounted for about 7% of the adult population in that year.5,7 Also in 2018, about 17 veterans committed suicide per day.5 According to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, about 18% reported thinking about attempting suicide some time in their lives compared with 4% of the general population.2,3 Additionally, 5% of service members reported previous suicide attempts compared with 0.5% in the general population.2,3 It is clear that transgender individuals, veterans, and service members have certain mental health outcomes that are worse than that of the general population.1-7

Transgender individuals along with LGB (lesbian, gay, bisexual) individuals have long faced discrimination and unfair treatment in the military.8-11 In the 1920s, the first written policies were established that banned gay men from serving in the military.9 The US Department of Defense (DoD) continued these policies until in 1993, the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” policy was established, which had the façade of being more inclusive for LGB individuals but forced LGB service members to hide their sexual identity and continued the anti-LGBTQ messages that previous policies had created.8,10,11 In 2010, “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” was repealed, which allowed LGB individuals to serve in the military without concealing their sexual orientation and without fear of discharge based on their sexual identity.11 This repeal did not allow transgender individuals to serve their country as the DoD categorized transgender identity as a medical and mental health disorder.8,11

In 2016, the ban on transgender individuals serving in the military was lifted, and service members could no longer be discharged or turned away from joining the military based on gender identity.8,12 However, in 2018, this order was reversed. The new policy stated that new service members must meet requirements and standards of their sex assigned at birth, and individuals with a history of gender dysphoria or those who have received gender-affirming medical or surgical treatment were prohibited to serve in the military.8,13 This policy did not apply to service members who joined before it took effect. Finally, in April 2021, the current policy took effect, permitting transgender individuals to openly serve in the military. The current policy states that service members cannot be discharged or denied reenlistment based on their gender identity and provides support to receive gender-affirming medical care.14 Although transgender individuals are now accepted in military service, there is still much progress needed to promote equity among transgender service members.

In 2015, according to the Health Related Behaviors Survey of active-duty service members, 0.6% of service members identified as transgender, the same percentage as US adults who identify as transgender.2,15 Previous research has shown that the prevalence of gender identity disorder among veterans is higher than that among the general US population.16 Many studies have shown that worse mental health outcomes exist among LGBTQ veterans and service members compared with heterosexual, cisgender veterans and service members.17-24 However, fewer studies have focused solely on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans and active-duty service members, and there exists no current literature review on this topic. In this article, we present data from the existing literature on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. We hypothesize, based on the current literature, that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. Key terms used in this paper are defined in the Key Definitions.25-27

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of articles presenting data on mental health outcomes in transgender veterans and active-duty service members. The National Library of Medicine PubMed database was searched using the following search terms in various combinations: mental health outcomes, transgender, veterans, military, active duty, substance use, and sexual trauma. The literature search was performed in August 2021 and included articles published through July 31, 2021. Methodology, size, demographics, measures, and main findings were extracted from each article. All studies were eligible for inclusion regardless of sample size. Studies that examined the LGBTQ population without separating transgender individuals were excluded. Studies that examined mental health outcomes including, but not limited to, PTSD, depression, suicidality, anxiety, and substance use disorders (SUDs) in addition to sexual trauma were included. Studies that only examined physical health outcomes were excluded. Qualitative studies, case reports, and papers that did not present original data were excluded (Figure).

Results

Our search resulted in 86 publications. After excluding 65 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 19 studies were included in this review. The Appendix shows the summary of findings from each study, including the study size and results. All studies were conducted in the United States. Most papers used a cross-sectional study design. Most of the studies focused on transgender veterans, but some included data on transgender active-duty service members.

We separated the findings into the following categories based on the variables measured: mental health, including depression, anxiety, PTSD, and serious mental illness; suicidality and self-harm; substance use; and military sexual trauma (MST). Many studies overlapped multiple categories.

Mental Health

Most of the studies included reported that transgender veterans have statistically significant worse mental health outcomes compared with cisgender veterans.28-30 In addition, transgender active-duty service members were found to have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender active-duty service members.31 MST and discrimination were associated with worse mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.32,33 One study showed a different result than others and found that transgender older adults with prior military service had higher psychological health-related quality of life and lower depressive symptoms than those without prior military service (P = .02 and .04, respectively).34 Another study compared transgender veterans with active-duty service members and found that transgender veterans reported higher rates of depression (64.6% vs 30.9%; χ2 = 11.68; P = .001) and anxiety (41.3% vs 18.2%; χ2 = 6.54; P = .01) compared with transgender service members.35

Suicidality and Self-harm

Eleven of the 19 studies included measured suicidality and/or self-harm as an outcome. Transgender veterans and active-duty service members were found to have higher odds of suicidality than their cisgender counterparts.16,28,29,31 In addition, transgender veterans may die by suicide at a younger age than cisgender veterans.36 Stigma and gender-related discrimination were found to be associated with suicidal ideation.33,37-39 Transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI).40

Substance Use

Two studies focused on substance use, while 5 other studies included substance use in their measures. One of these 2 studies that focused only on substance use outcomes found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any SUD (7.2% vs 3.9%; P < .001), in addition to specifically cannabis (3.4% vs 1.5%; P < .001), amphetamine (1.1% vs 0.3%; P < .001), and cocaine use disorders (1.5% vs 1.1%; P < .001).41

Another study reported that transgender veterans had lower odds of self-reported alcohol use but had greater odds of having alcohol-related diagnoses compared with cisgender veterans.42 Of the other studies, it was found that a higher percentage of transgender veterans were diagnosed with an SUD compared with transgender active-duty service members, and transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to be diagnosed with alcohol use disorder.29,31 Additionally, rural transgender veterans had increased odds of tobacco use disorder compared with transgender veterans who lived in urban areas.43

Military Sexual Trauma

Five of the studies included examined MST, defined as sexual assault or sexual harassment that is experienced during military service.44 Studies found that 15% to 17% of transgender veterans experienced MST.32,45 Transgender veterans were more likely to report MST than cisgender veterans.28,29 MST was found to be consistently associated with depression and PTSD.32,45 A high percentage (83.9%) of transgender active-duty service members reported experiencing sexual harassment and almost one-third experienced sexual assault.46

Discussion

Outcomes examined in this review included MST, substance use, suicidality, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD among transgender active-duty service members and veterans. To our knowledge, no other review on this topic exists. There is a review of the health and well-being of LGBTQ veterans and service members, but a majority of the included studies did not separate transgender individuals from LGB persons.17 This review of transgender individuals showed similar results to the review of LGBTQ individuals.17 This review also presented similar results to previous studies that indicated that transgender individuals in the general population have worse mental health outcomes compared with their cisgender counterparts, in addition to studies that showed that veterans and active-duty service members have worse mental health outcomes compared with civilians and nonveterans.1-5 The population of focus in this review faced a unique set of challenges, being that they belonged to both of these subsets of the population, both of which experienced worse mental health outcomes, according to the literature.

Studies included in our review found that transgender veterans and service members have worse mental health outcomes than cisgender veterans and service members.28-31 This outcome was predicted based on previous data collection among transgender individuals, veterans, and active-duty service members. One of the studies included found different results and concluded that prior military service was a protective factor against poorer mental health outcomes.34 This could be, in part, due to veterans’ access to care through the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) system. It has been found that transgender veterans use VA services at higher rates than the general population of veterans and that barriers to care were found more for medical treatment than for mental health treatment.47 One study found that almost 70% of transgender veterans who used VA services were satisfied with their mental health care.48 In contrast, another study included in our review found that transgender veterans had worse mental health outcomes than transgender service members, possibly showing that even with access to care, the burden of stigma and discrimination worsens mental health over time.31 Although it has been shown that transgender veterans may feel comfortable disclosing their gender identity to their health care professional, many barriers to care have been identified, such as insensitivity and lack of knowledge about transgender care among clinicians.49-51 With this information, it would be useful to ensure proper training for health care professionals on providing gender-affirming care.

Most of the studies also found that transgender veterans and service members had greater odds of suicidal thoughts and events than cisgender veterans and service members.16,28,29,35 On the contrary, transgender veterans were less likely than transgender nonveterans to report NSSI, which could be for various reasons.40 Transgender veterans may report less NSSI but experience it at similar rates, or veteran status may be a protective factor for NSSI.

Very few studies included SUDs in their measurements, but it was found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to have any drug and alcohol use disorder.29,41 In addition, transgender veterans were more likely than transgender service members to be diagnosed with an SUD, again showing that over time and after time of service, mental health may worsen due to the burden of stigma and discrimination.31 Studies that examined MST found that transgender veterans were more likely than cisgender veterans to report MST, which replicates previous data that found high rates of sexual assault experienced among transgender individuals.1,28,29

There is a lack of literature surrounding transgender veterans and active-duty service members, especially with regard to gender-affirming care provided to these populations. To the best of our knowledge, there exists only one original study that examines the effect of gender-affirming hormone therapy and surgery on mental health outcomes among transgender veterans.52 Further research in this area is needed, specifically longitudinal studies examining the effects of gender-affirming medical care on various outcomes, including mental health. Few longitudinal studies exist that examine the mental health effects of gender-affirming hormone therapy on transgender individuals in the general population.53-60 Most of these studies have shown a significant improvement in parameters of depression and anxiety following hormonal treatment, although long-term large follow-up studies to understand whether these improvements persist over time are missing also in the general population. However, as previously described, transgender veterans and service members are a unique subset of the transgender population and require separate data collection. Hence, further research is required to provide optimal care for this population. In addition, early screening for symptoms of mental illness, substance use, and MST is important to providing optimal care.

Limitations

This review was limited due to the lack of data collected from transgender veterans and service members. The studies included did not allow for standardized comparisons and did not use identical measures. Some papers compared transgender veterans with transgender nonveterans, some transgender veterans and/or service members with cisgender veterans and/or service members, and some transgender veterans with transgender service members. There were some consistent results found across the studies, but some studies showed contradictory results or no significant differences within a certain category. It is difficult to compare such different study designs and various participant populations. Additional research is required to verify and replicate these results.

Conclusions

Although this review was limited due to the lack of consistent study designs in the literature examining the mental health of transgender veterans and active-duty service members, overall results showed that transgender veterans and service members experience worse mental health outcomes than their cisgender counterparts. With this knowledge and exploring the history of discrimination that this population has faced, improved systems must be put into place to better serve this population and improve health outcomes. Additional research is required to examine the effects of gender-affirming care on mental health among transgender veterans and service members.

1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. December 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.ustranssurvey.org

2. Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Rand Health Q. 2018;8(2):434.

3. Lipari R, Piscopo K, Kroutil LA, Miller GK. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. 2015:1-14. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR2-2014/NSDUH-FRR2-2014.pdf

4. Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):504-513. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. November 2020. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2020/2020-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-11-2020-508.pdf

6. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

7. Vespa J. Those who SERVED: America’s veterans from World War II to the war on terror. The United States Census Bureau. June 2, 2020. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2020/demo/acs-43.html

8. Seibert DC, Keller N, Zapor L, Archer H. Military transgender care. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2020;32(11):764-770. doi:10.1097/JXX.0000000000000519

9. Rigby WC. Military penal law: A brief survey of the 1920 revision of the Articles of War. J Crim Law Criminol. 1921;12(1):84.

10. Department of Defense Directive Number 1332.14: Enlisted Administrative Separations. December 21, 1993. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/blaw/dodd/corres/pdf/d133214wch1_122193/d133214p.pdf

11. Aford B, Lee SJ. Toward complete inclusion: lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender military service members after repeal of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell. Soc Work. 2016;61(3):257-265. doi:10.1093/sw/sww033

12. Department of Defense Instruction 1300.28: In-Service Transition for Transgender Service Members. June 30, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://dod.defense.gov/Portals/1/features/2016/0616_policy/DoD-Instruction-1300.28.pdf

13. Department of Defense. Directive-type Memorandum (DTM)-19-004 - Military Service by Transgender Persons and Persons with Gender Dysphoria. March 12. 2019. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://health.mil/Reference-Center/Policies/2020/03/17/Military-Service-by-Transgender-Persons-and-Persons-with-Gender-Dysphoria

14. US Department of Defense Instruction 1300.28: In-Service Transition for Transgender Service Members. April 30, 2021. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.esd.whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/dodi/130028p.pdf

15. Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? The Williams Institute; 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://williamsinstitute.law.ucla.edu/publications/trans-adults-united-states/

16. Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Shipherd Phd JC, Kauth M, Piegari RI, Bossarte RM. Prevalence of gender identity disorder and suicide risk among transgender veterans utilizing veterans health administration care. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(10):e27-e32. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301507

17. Mark KM, McNamara KA, Gribble R, et al. The health and well-being of LGBTQ serving and ex-serving personnel: a narrative review. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(1):75-94. doi:10.1080/09540261.2019.1575190

18. Blosnich J, Foynes MM, Shipherd JC. Health disparities among sexual minority women veterans. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013;22(7):631-636. doi:10.1089/jwh.2012.4214

19. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM, Silenzio VM. Suicidal ideation among sexual minority veterans: results from the 2005-2010 Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S44-S47. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300565

20. Blosnich JR, Gordon AJ, Fine MJ. Associations of sexual and gender minority status with health indicators, health risk factors, and social stressors in a national sample of young adults with military experience. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25(9):661-667. doi:10.1016/j.annepidem.2015.06.001

21. Cochran BN, Balsam K, Flentje A, Malte CA, Simpson T. Mental health characteristics of sexual minority veterans. J Homosex. 2013;60(2-3):419-435. doi:10.1080/00918369.2013.744932

22. Lehavot K, Browne KC, Simpson TL. Examining sexual orientation disparities in alcohol misuse among women veterans. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(5):554-562. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.002

23. Scott RL, Lasiuk GC, Norris CM. Depression in lesbian, gay, and bisexual members of the Canadian Armed Forces. LGBT Health. 2016;3(5):366-372. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2016.0050

24. Wang J, Dey M, Soldati L, Weiss MG, Gmel G, Mohler-Kuo M. Psychiatric disorders, suicidality, and personality among young men by sexual orientation. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29(8):514-522. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2014.05.001

25. American Psychological Association. Gender. APA Style. September 2019. Updated July 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/bias-free-language/gender

26. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. 5th ed., American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

27. Deutsch MB. Overview of gender-affirming treatments and procedures. UCSF Transgender Care. June 17, 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://transcare.ucsf.edu/guidelines/overview

28. Brown GR, Jones KT. Health correlates of criminal justice involvement in 4,793 transgender veterans. LGBT Health. 2015;2(4):297-305. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0052

29. Brown GR, Jones KT. Mental health and medical health disparities in 5135 transgender veterans receiving healthcare in the Veterans Health Administration: a case-control study. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):122-131. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2015.0058

30. Downing J, Conron K, Herman JL, Blosnich JR. Transgender and cisgender US veterans have few health differences. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018;37(7):1160-1168. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2018.0027

31. Holloway IW, Green D, Pickering C, et al. Mental health and health risk behaviors of active duty sexual minority and transgender service members in the United States military. LGBT Health. 2021;8(2):152-161. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2020.0031

32. Beckman K, Shipherd J, Simpson T, Lehavot K. Military sexual assault in transgender veterans: results from a nationwide survey. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(2):181-190. doi:10.1002/jts.22280

33. Blosnich JR, Marsiglio MC, Gao S, Gordon AJ, Shipherd JC, Kauth M, Brown GR, Fine MJ. Mental health of transgender veterans in US states with and without discrimination and hate crime legal protection. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):534-540. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2015.302981

34. Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, Kim HJ, Sturges AM, Fredriksen-Goldsen KI. Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. Gerontologist. 2017;57(suppl 1):S63-S71. doi:10.1093/geront/gnw173

35. Hill BJ, Bouris A, Barnett JT, Walker D. Fit to serve? Exploring mental and physical health and well-being among transgender active-duty service members and veterans in the U.S. military. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):4-11. Published 2016 Jan 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2015.0002

36. Blosnich JR, Brown GR, Wojcio S, Jones KT, Bossarte RM. Mortality among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses in the Veterans Health Administration, FY2000-2009. LGBT Health. 2014;1(4):269-276. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2014.0050

37. Carter SP, Allred KM, Tucker RP, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Discrimination and suicidal ideation among transgender veterans: the role of social support and connection. LGBT Health. 2019;6(2):43-50. doi:10.1089/lgbt.2018.0239

38. Lehavot K, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Factors associated with suicidality among a national sample of transgender veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46(5):507-524. doi:10.1111/sltb.12233

39. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Reger MA, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Lehavot K. Current and military-specific gender minority stress factors and their relationship with suicide ideation in transgender veterans. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49(1):155-166. doi:10.1111/sltb.12432

40. Aboussouan A, Snow A, Cerel J, Tucker RP. Non-suicidal self-injury, suicide ideation, and past suicide attempts: Comparison between transgender and gender diverse veterans and non-veterans. J Affect Disord. 2019;259:186-194. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2019.08.046

41. Frost MC, Blosnich JR, Lehavot K, Chen JA, Rubinsky AD, Glass JE, Williams EC. Disparities in documented drug use disorders between transgender and cisgender U.S. Veterans Health Administration patients. J Addict Med. 2021;15(4):334-340. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000769

42. Williams EC, Frost MC, Rubinsky AD, et al. Patterns of alcohol use among transgender patients receiving care at the Veterans Health Administration: overall and relative to nontransgender patients. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2021;82(1):132-141. doi:10.15288/jsad.2021.82.132

43. Bukowski LA, Blosnich J, Shipherd JC, Kauth MR, Brown GR, Gordon AJ. Exploring rural disparities in medical diagnoses among veterans with transgender-related diagnoses utilizing Veterans Health Administration care. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 9):S97-S103. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000745

44. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Military Sexual Trauma. Updated August 1, 2022. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/mentalhealth/msthome/index.asp

45. Lindsay JA, Keo-Meier C, Hudson S, Walder A, Martin LA, Kauth MR. Mental health of transgender veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts who experienced military sexual trauma. J Trauma Stress. 2016;29(6):563-567. doi:10.1002/jts.22146

46. Schuyler AC, Klemmer C, Mamey MR, et al. Experiences of sexual harassment, stalking, and sexual assault during military service among LGBT and Non-LGBT service members. J Trauma Stress. 2020;33(3):257-266. doi:10.1002/jts.22506

47. Shipherd JC, Mizock L, Maguen S, Green KE. Male-to-female transgender veterans and VA health care utilization. Int J Sexual Health. 2012;24(1):78-87. doi:10.1080/19317611.2011.639440

48. Lehavot K, Katon JG, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC. Transgender veterans’ satisfaction with care and unmet health needs. Med Care. 2017;55(suppl 9):S90-S96. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000723

49. Kauth MR, Barrera TL, Latini DM. Lesbian, gay, and transgender veterans’ experiences in the Veterans Health Administration: positive signs and room for improvement. Psychol Serv. 2019;16(2):346-351. doi:10.1037/ser0000232

50. Rosentel K, Hill BJ, Lu C, Barnett JT. Transgender veterans and the Veterans Health Administration: exploring the experiences of transgender veterans in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare System. Transgend Health. 2016;1(1):108-116. Published 2016 Jun 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0006

51. Dietert M, Dentice D, Keig Z. Addressing the needs of transgender military veterans: better access and more comprehensive care. Transgend Health. 2017;2(1):35-44. Published 2017 Mar 1. doi:10.1089/trgh.2016.0040

52. Tucker RP, Testa RJ, Simpson TL, Shipherd JC, Blosnich JR, Lehavot K. Hormone therapy, gender affirmation surgery, and their association with recent suicidal ideation and depression symptoms in transgender veterans. Psychol Med. 2018;48(14):2329-2336. doi:10.1017/S0033291717003853

53. Colizzi M, Costa R, Todarello O. Transsexual patients’ psychiatric comorbidity and positive effect of cross-sex hormonal treatment on mental health: results from a longitudinal study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2014;39:65-73. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.09.029

54. Heylens G, Verroken C, De Cock S, T’Sjoen G, De Cuypere G. Effects of different steps in gender reassignment therapy on psychopathology: a prospective study of persons with a gender identity disorder. J Sex Med. 2014;11(1):119-126. doi:10.1111/jsm.12363

55. Fisher AD, Castellini G, Ristori J, et al. Cross-sex hormone treatment and psychobiological changes in transsexual persons: two-year follow-up data. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(11):4260-4269. doi:10.1210/jc.2016-1276

56. Aldridge Z, Patel S, Guo B, et al. Long-term effect of gender-affirming hormone treatment on depression and anxiety symptoms in transgender people: a prospective cohort study. Andrology. 2021;9(6):1808-1816. doi:10.1111/andr.12884

57. Costantino A, Cerpolini S, Alvisi S, Morselli PG, Venturoli S, Meriggiola MC. A prospective study on sexual function and mood in female-to-male transsexuals during testosterone administration and after sex reassignment surgery. J Sex Marital Ther. 2013;39(4):321-335. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2012.736920

58. Keo-Meier CL, Herman LI, Reisner SL, Pardo ST, Sharp C, Babcock JC. Testosterone treatment and MMPI-2 improvement in transgender men: a prospective controlled study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2015;83(1):143-156. doi:10.1037/a0037599

59. Turan S‚ , Aksoy Poyraz C, Usta Sag˘lam NG, et al. Alterations in body uneasiness, eating attitudes, and psychopathology before and after cross-sex hormonal treatment in patients with female-to-male gender dysphoria. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47(8):2349-2361. doi:10.1007/s10508-018-1189-4

60. Oda H, Kinoshita T. Efficacy of hormonal and mental treatments with MMPI in FtM individuals: cross-sectional and longitudinal studies. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):256. Published 2017 Jul 17. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1423-y

1. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anafi M. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. National Center for Transgender Equality. December 2016. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.ustranssurvey.org

2. Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Rand Health Q. 2018;8(2):434.

3. Lipari R, Piscopo K, Kroutil LA, Miller GK. Suicidal thoughts and behavior among adults: results from the 2014 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. NSDUH Data Review. 2015:1-14. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/sites/default/files/NSDUH-FRR2-2014/NSDUH-FRR2-2014.pdf

4. Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, et al. Thirty-day prevalence of DSM-IV mental disorders among nondeployed soldiers in the US Army: results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(5):504-513. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28

5. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. November 2020. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2020/2020-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-11-2020-508.pdf