User login

Cutaneous Pemphigus Vegetans Co-occurring With Oral Pemphigus Vulgaris

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

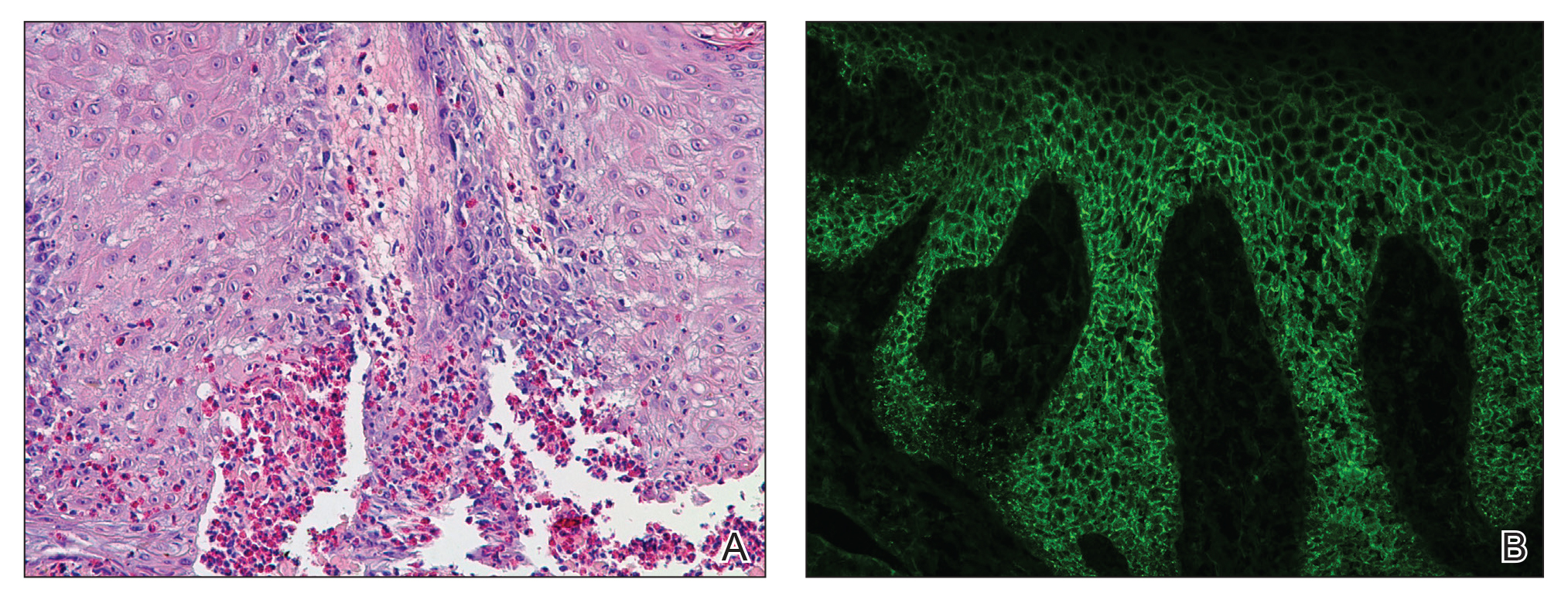

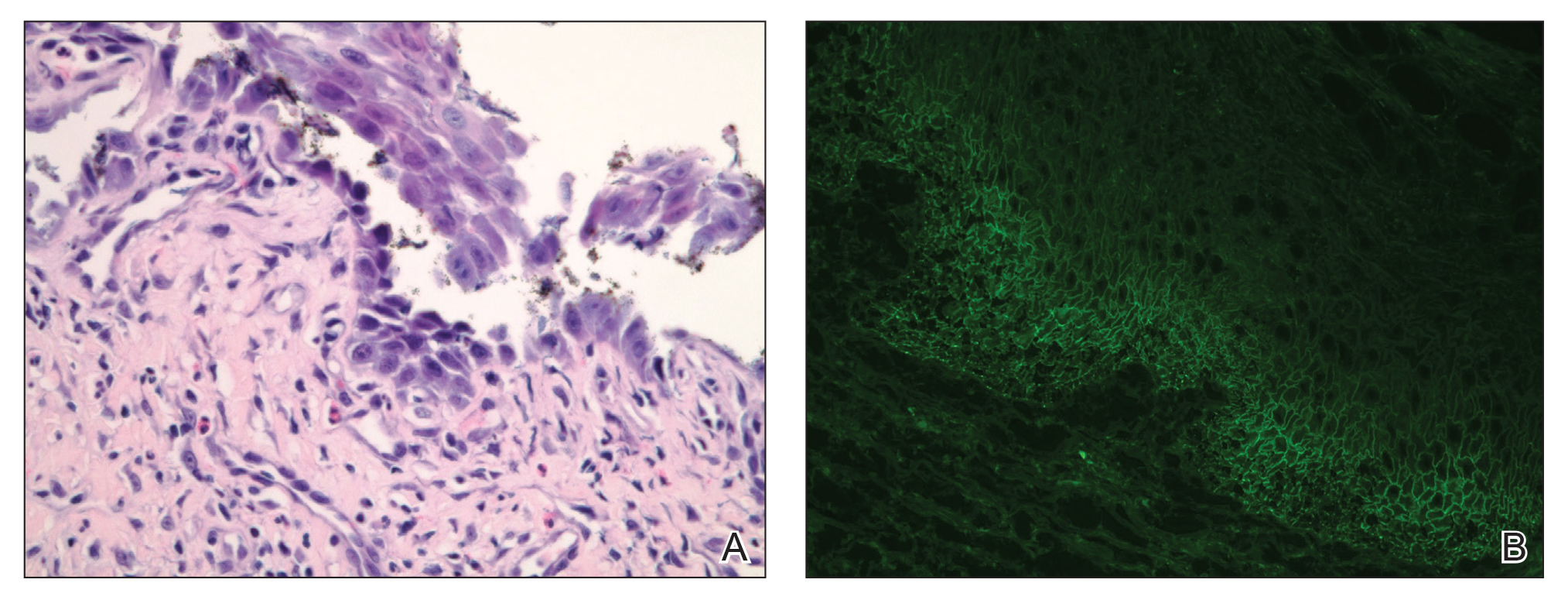

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

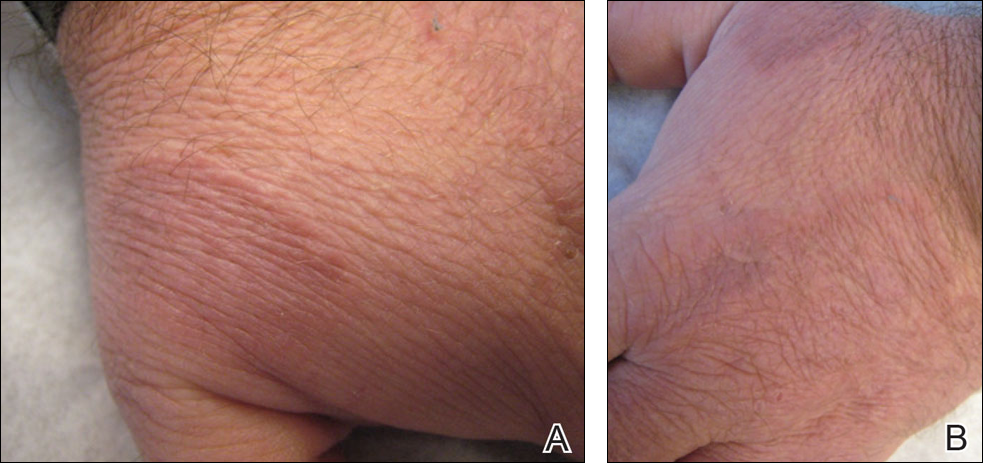

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

To the Editor:

A 74-year-old man with a history of colon cancer and no history of sexually transmitted diseases presented with tender, moist, vegetating, and verrucous plaques localized to the inguinal creases and behind the scrotum of 3 weeks’ duration (Figure 1). The patient recently had taken lisinopril prescribed by his primary care physician for a couple of years for hypertension before switching to losartan prior to the current presentation. He later noticed the groin eruptions. He also noticed white tongue plaques temporally associated with the groin plaques and a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations. Prior to being seen in our clinic, outside physicians cultured methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus from the groin plaques and treated him with oral clindamycin, cephalexin, and topical mupirocin without a clinical response.

Our differential diagnosis included condyloma acuminata, condyloma lata, and cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Laboratory testing revealed a nonreactive rapid plasma reagin test and peripheral eosinophilia of 14.9% (reference range, 0%–6%). Biopsy of a left groin plaque revealed epidermal hyperplasia with spongiosis and an eosinophilic-rich infiltrate on hematoxylin and eosin staining (Figure 2A), and direct immunofluorescence revealed diffuse epidermal intercellular IgG deposits (Figure 2B). The patient’s clinical and histologic presentation was consistent with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans. Biopsy of an oral ulcer revealed denuded acantholytic mucositis with eosinophilic-rich submucosal infiltrate and fibrosis (Figure 3A). Direct immunofluorescence was positive for lacelike intercellular staining for IgG and C3 within the squamous epithelium (Figure 3B). Together the clinical and histologic findings were consistent with oral pemphigus vulgaris.

The patient initially was started on oral minocycline 100 mg twice daily and mometasone furoate cream 0.1% twice daily to affected groin areas. With these interventions, the groin plaques almost completely resolved after several months, leaving only residual hyperpigmentation (Figure 4). The oral pemphigus vulgaris initially was treated with dexamethasone 0.5 mg/5 mL solution 2 to 3 times daily, but the lesions were refractory to this approach and also did not improve after the losartan was discontinued for several months. As such, mycophenolate mofetil was started. He was titrated to the lowest effective dose and showed near-complete resolution with 500 mg 3 times daily.

Cutaneous pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris, is characterized by vegetating plaques commonly localized to the skin folds, scalp, face, and mucous membranes.1 Involvement of the oral mucosa occurs in a majority of cases. Although our patient had oral ulcerations, he did not have characteristic cerebriform changes of the dorsal tongue or associated verrucous hyperkeratotic lesions involving the buccal mucosa, hard and soft palate, or vermilion border of the lips that typically are seen in pemphigus vegetans.2-5 Subsequent biopsy of the oral mucosa confirmed oral pemphigus vulgaris in our patient.

This case presentation of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris is uncommonly reported in the literature. Although the etiology of this co-occurrence is not clear, it could represent a form of epitope spread, with the mechanism similar to that proposed for the progression of pemphigus vulgaris from the mucosal to the mucocutaneous stage by Chan et al,6 who suggested that an autoimmune reaction against specific desmoglein 3 epitopes (an important protein component for desmosomes and the autoantigen in pemphigus vulgaris) on mucosal membranes could induce local damage. These injuries could then expose the autoreactive immune cells to a secondary desmoglein 3 epitope present in the skin, leading to the development of cutaneous lesions.6 Salato et al7 also supported this idea of intramolecular epitope spread in pemphigus vulgaris, explaining that at various stages of the disease (mucosal and mucocutaneous), the antibodies have “different tissue-binding patterns and pathogenic activities, suggesting that they may recognize distinct epitopes.” This concept of epitope spread from the oral mucosal form to the cutaneous form of pemphigus vulgaris also could help explain our patient’s presentation, as he had a long history of recurrent oral ulcerations prior to developing the vegetating cutaneous plaques of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

We also appreciate that either the cutaneous pemphigus vegetans or oral pemphigus vulgaris could have been drug induced in our case. Captopril has been reported to cause pemphigus vulgaris,8 so it is conceivable that the related medication lisinopril was the culprit in our case. A prior case report described an elderly man who developed lisinopril-induced pemphigus foliaceus; however, there was no oral involvement in this case and no further blister formation within 48 hours of discontinuing lisinopril.9 An additional case report implicated lisinopril in the development of a bullous eruption on the oral mucosa in a female patient, though direct and indirect immunofluorescence did not reveal the autoantibodies that typically are seen in pemphigus vulgaris.10 Our patient’s blood eosinophilia also could support an adverse drug reaction. Our patient’s losartan was discontinued for several months without respite of the oral ulcerations and thus was restarted. The cutaneous pemphigus vegetans continues to be in remission and was unaffected by restarting the losartan, making it a less likely culprit for his presentation.

We identified another case in the literature in which an individual with a history of colon cancer was diagnosed with cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.11 As such, we considered a possible link between the 2 diagnoses; however, the temporal disconnect between both conditions in our patient makes this less likely, unlike the other reported case in which the internal neoplasm and pemphigus vegetans appeared nearly simultaneously.11

Finally, our case supports a combination of topical steroids and minocycline for treatment of cutaneous pemphigus vegetans.

Our case demonstrates the importance of considering cutaneous pemphigus vegetans in the differential diagnosis, despite its rarity, when patients present with vegetating plaques. In addition, although oral involvement is common with this condition, if the patient’s oral lesions do not fit the characteristic oral findings seen in pemphigus vegetans, alternative diagnoses should be considered.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

- de Almeida HL Jr, Neugebauer MG, Guarenti IM, et al. Pemphigus vegetans associated with verrucous lesions: expanding a phenotype. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2006;61:279-282.

- Danopoulou I, Stavropoulos P, Stratigos A, et al. Pemphigus vegetans confined to the scalp. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1008-1009.

- Markopoulos AK, Antoniades DZ, Zaraboukas T. Pemphigus vegetans of the oral cavity. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:425-428.

- Woo TY, Solomon AR, Fairley JA. Pemphigus vegetans limited to the lips and oral mucosa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:271-272.

- Yuen KL, Yau KC. An old gentleman with vegetative plaques and erosions: a case of pemphigus vegetans. Hong Kong J Dermatol Venereol. 2012;20:179-182.

- Chan LS, Vanderlugt CJ, Hashimoto T, et al. Epitope spreading: lessons from autoimmune skin diseases. J Invest Dermatol. 1998;110:103-109.

- Salato VK, Hacker-Foegen MK, Lazarova Z, et al. Role of intramolecular epitope spreading in pemphigus vulgaris. Clin Immunol. 2005;116:54-64.

- Dashore A, Choudhary SD. Captopril induced pemphigus vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1987;53:293-294.

- Patterson CR, Davies MG. Pemphigus foliaceus: an adverse reaction to lisinopril. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15:60-62.

- Baričević M, Mravak Stipeti´c M, Situm M, et al. Oral bullous eruption after taking lisinopril—case report and literature review. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2013;125:408-411.

- Torres T, Ferreira M, Sanches M, et al. Pemphigus vegetans in a patient with colonic cancer. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2009;75:603-605.

Practice Points

- Recognize the clinical and histologic features of pemphigus vegetans, a rare variant of pemphigus vulgaris.

- Consider mechanisms of co-occurring cutaneous pemphigus vegetans and oral pemphigus vulgaris.

Resolution of Disseminated Granuloma Annulare With Removal of Surgical Hardware

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

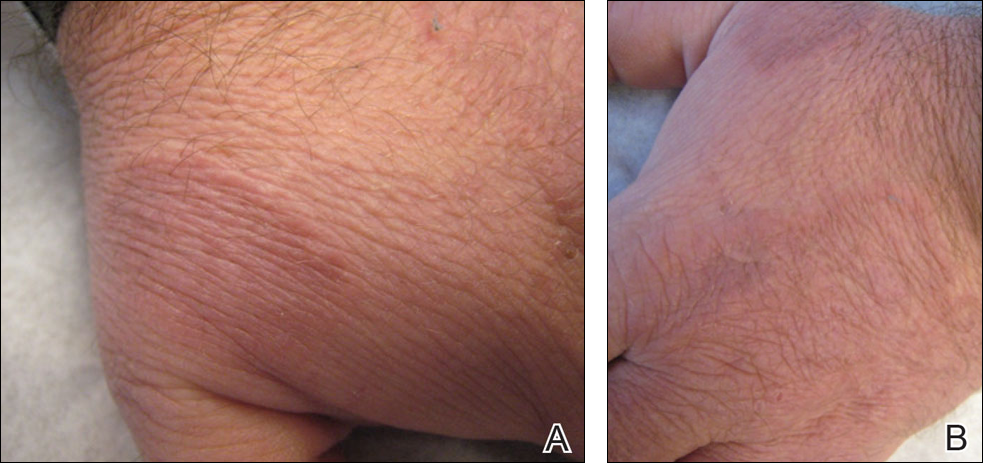

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

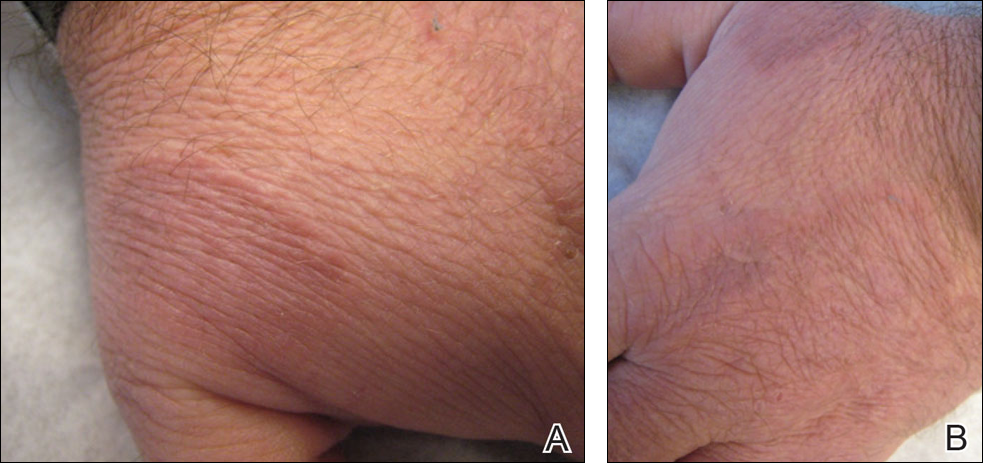

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

To the Editor:

Disseminated granuloma annulare is a noninfectious granulomatous disease of unknown etiology. Reported precipitating factors include trauma, sun exposure, viral infection, vaccination, and malignancy.1 In contrast to a localized variant, disseminated granuloma annulare is associated with a later age of onset, longer duration, and recalcitrance to therapy.2 Although a variety of therapeutic approaches exist, there are limited efficacy data, which is complicated by the spontaneous, self-limited nature of the disease.3,4

A 47-year-old man presented with an eruption of a thick red plaque on the dorsal aspect of the left hand (Figure). The eruption began 6 weeks following fixation of a Galeazzi fracture of the right radius with a stainless steel volar plate. Subsequent to the initial eruption, similar indurated plaques developed on the left thenar area, bilateral axillae, and bilateral legs. A punch biopsy was conducted to rule out necrobiosis lipoidica diabeticorum and sarcoidosis as well as to histopathologically confirm the clinical diagnosis of disseminated granuloma annulare. Following diagnosis, the patient received topical clobetasol for application to the advancing borders of the plaques. At 4-month follow-up, additional plaques continued to develop. The patient was not interested in pursuing alternative courses of therapy and felt that the implantation of surgical hardware was the cause. To the best of our knowledge, there have been no reports of precipitation of disseminated granuloma annulare in response to surgical hardware. Given the time course of onset of the eruption it was plausible that the hardware was the inciting event. The orthopedist thought that the fracture had healed sufficiently to remove the volar plate. The patient elected to have the hardware removed to potentially resolve or arrest the progression of the plaques. Resolution of the plaques was observed by the patient 2 weeks following surgical removal of the volar plate. At 4 months following hardware removal, the patient only had 2 slightly pink, hyperpigmented lesions on the left hand in the areas most severely affected, with complete resolution of all other plaques. The patient was given topical clobetasol for the residual lesions.

Precipitation and spontaneous resolution of disseminated granuloma annulare following the implantation and removal of surgical hardware is rare. Resolution following hardware removal is consistent with the theory that pathogenesis is due to a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to an inciting factor.5 Our case suggests that disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware, which should be considered in the etiology and potential therapeutic options for this disorder.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

- Mills A, Chetty R. Auricular granuloma annulare. a consequence of trauma? Am J Dermatopathol. 1992;14:431-433.

- Dicken CH, Carrington SG, Winkelmann RK. Generalized granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1969;99:556-563.

- Yun JH, Lee JY, Kim MK, et al. Clinical and pathological features of generalized granuloma annulare with their correlation: a retrospective multicenter study in Korea [published online May 31, 2009]. Ann Dermatol. 2009:21:113-119

- Cyr PR. Diagnosis and management of granuloma annulare. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:1729-1734.

- Buechner SA, Winkelmann RK, Banks PM. Identification of T-cell subpopulations in granuloma annulare. Arch Dermatol. 1983;119:125-128.

Practice Points

- Disseminated granuloma annulare may occur as a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction to implanted surgical hardware.

- Resolution may occur following removal of surgical hardware.