User login

Finding catatonia requires knowing what to look for

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome identified by its clinical phenotype. Unlike common psychiatric syndromes such as major depression that are characterized by self-report of symptoms, catatonia is identified chiefly by empirically evaluated signs on clinical evaluation. Its signs are recognized through observation, physical examination, or elicitation by clinical maneuvers or the presentation of stimuli. However, catatonia is often overlooked even though its clinical signs are often visibly apparent, including to the casual observer.

Why is catatonia underdiagnosed? A key modifiable factor appears to be a prevalent misunderstanding over what catatonia looks like.1 We have sought to address this in a few ways.

First identified was the need for comprehensive educational resources on how to assess for and recognize catatonia. Using the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale – the most widely used scale for catatonia in both research and clinical settings and the most cited publication in the catatonia literature– our team developed the BFCRS Training Manual and Coding Guide.2,3 This manual expands on the definitions of each BFCRS item based on how it was originally operationalized by the scale’s authors. Subsequently, we created a comprehensive set of educational resources including videos illustrating how to assess for catatonia, a video for each of the 23 items on the BFCRS, and self-assessment tools. All resources are freely available online at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.4

Through this project it became apparent that there are many discrepancies across the field regarding the phenotype of catatonia. Specifically, a recent review inspired by this project set about to characterize the scope of distinctions across diagnostic systems and rating scales.5 For instance, each diagnostic system and rating scale includes a unique set of signs, approaches diagnostic thresholds differently, and often operationalizes clinical features in ways that lead either to criterion overlap (for example, combativeness would be scored both as combativeness and agitation on ICD-11) or contradictions with other systems or scales (for example, varied definitions of waxy flexibility). In the face of so many inconsistencies, what is a clinician to do? What follows is a discussion of how to apply the insights from this recent review in clinical and research settings.

Starting with DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 – the current editions of the two leading diagnostic systems – one might ask: How do they compare?6,7 Overall, these two systems are broadly aligned in terms of the catatonic syndrome. Both systems identify individual clinical signs (as opposed to symptom complexes). Both require three features as a diagnostic threshold. Most of the same clinical signs are included in both systems, and the definitions of individual items are largely equivalent. Additionally, both systems allow for diagnosis of catatonia in association with psychiatric and medical conditions and include a category for unspecified catatonia.

Despite these core agreements, though, there are several important distinctions. First, whereas all 12 signs included in DSM-5-TR count toward an ICD-11 catatonia diagnosis, the opposite cannot be said. ICD-11 includes several features that are not in DSM-5-TR: rigidity, verbigeration, withdrawal, staring, ambitendency, impulsivity, and combativeness. Next, autonomic abnormality, which signifies the most severe type of catatonia called malignant catatonia, is included as a potential comorbidity in ICD-11 but not mentioned in DSM-5-TR. Third, ICD-11 includes a separate diagnosis for substance-induced catatonia, whereas this condition would be diagnosed as unspecified catatonia in DSM-5-TR.

There are also elements missing from both systems. The most notable of these is that neither system specifies the period over which findings must be present for diagnosis. By clinical convention, the practical definition of 24 hours is appropriate in most instances. The clinical features identified during direct evaluation are usually sufficient for diagnosis, but additional signs observed or documented over the prior 24 hours should be incorporated as part of the clinical evaluation. Another distinction is how to handle clinical features before and after lorazepam challenge. As noted in the BFCRS Training Manual, it would be appropriate to compare “state assessments” (that is, restricted to features identified only during direct, in-person assessment) from before and after lorazepam administration to document improvement.4

Whereas DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 are broadly in agreement, comparing these systems with catatonia rating scales reveals many sources of potential confusion, but also concrete guidance on operationalizing individual items.5 How exactly should each of catatonia’s clinical signs be defined? Descriptions differ, and thresholds of duration and frequency vary considerably across scales. As a result, clinicians who use different scales and then convert these results to diagnostic criteria are liable to come to different clinical conclusions. For instance, both echophenomena and negativism must be elicited more than five times to be scored per Northoff,8 but even a single convincing instance of either would be scored on the BFCRS as “occasional.”2

Such discrepancies are important because, whereas the psychometric properties of several catatonia scales have been documented, there are no analogous studies on the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 criteria. Therefore, it is essential for clinicians and researchers to document how diagnostic criteria have been operationalized. The most practical and evidence-based way to do this is to use a clinically validated scale and convert these to diagnostic criteria, yet in doing so a few modifications will be necessary.

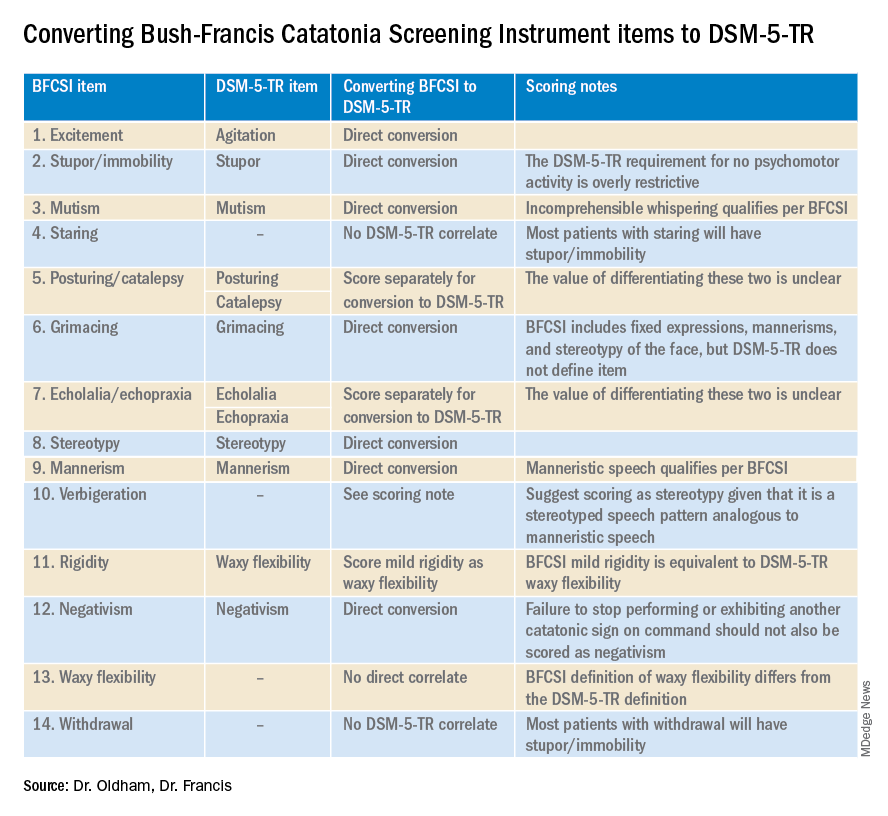

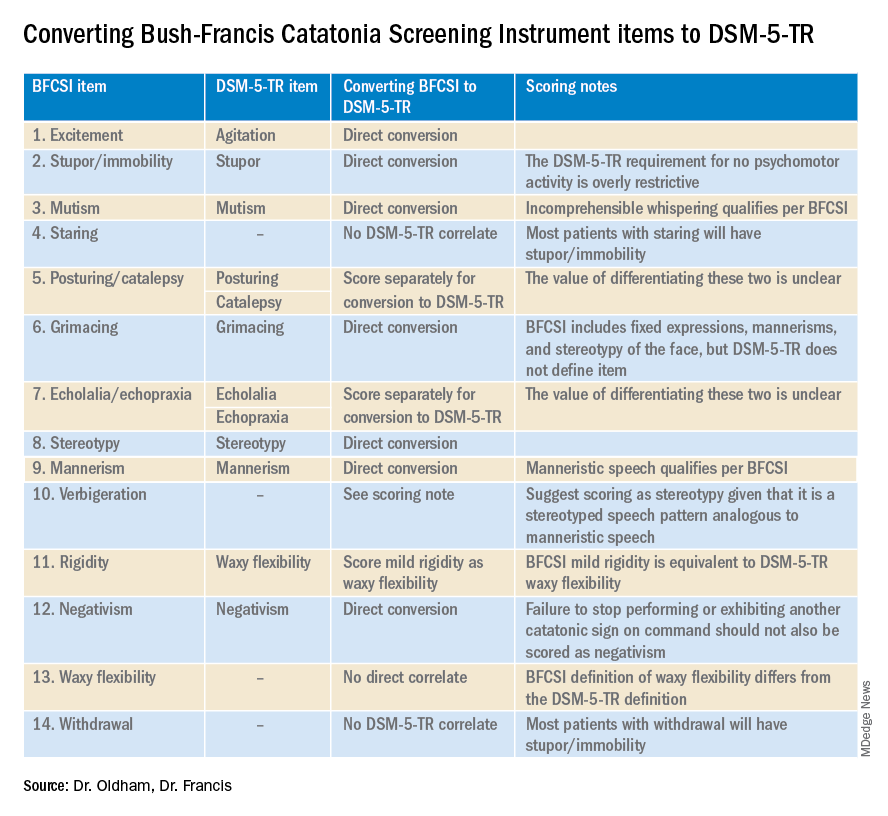

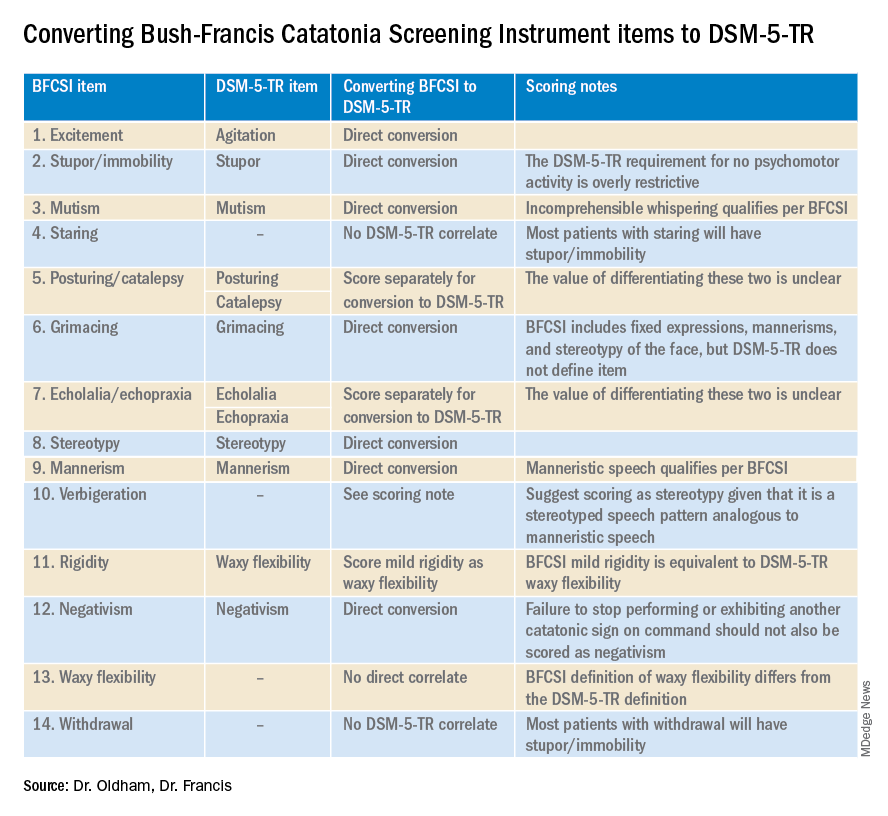

Of the available clinical scales, the BFCRS is best positioned for clinical use. The BFCRS has been validated clinically and has good reliability, detailed item definitions and audiovisual examples available. In addition, it is the only scale with a published semistructured evaluation (see initial paper and Training Manual), which takes about 5 minutes.2,4 In terms of utility, all 12 signs included by DSM-5-TR are among the first 14 items on the BFCRS, which constitutes a standalone tool known as the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI, see Table).

Many fundamental questions remain about catatonia,but the importance of a shared understanding of its clinical features is clear.9 Catatonia should be on the differential whenever a patient exhibits a markedly altered level of activity or grossly abnormal behavior, especially when inappropriate to context. We encourage readers to familiarize themselves with the phenotype of catatonia through online educational resources4 because the optimal care of patients with catatonia requires – at a minimum – that we know what we’re looking for.

Dr. Oldham is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center. Dr. Francis is professor of psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey. The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest. Funding for the educational project hosted at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu was provided by the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Dr. Oldham is currently supported by a K23 career development award from the National Institute on Aging (AG072383). The educational resources referenced in this piece could not have been created were it not for the intellectual and thespian collaboration of Joshua R. Wortzel, MD, who is currently a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Brown University, Providence, R.I. The authors are also indebted to Hochang B. Lee, MD, for his gracious support of this project.

References

1. Wortzel JR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 17;82(5):21m14025. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14025.

2. Bush G et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996 Feb;93(2):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x.

3. Weleff J et al. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023 Jan-Feb;64(1):13-27. doi:10.1016/j.jaclp.2022.07.002.

4. Oldham MA et al. Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale Assessment Resources. University of Rochester Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry. https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.

5. Oldham MA. Schizophr Res. 2022 Aug 19;S0920-9964(22)00294-8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.08.002.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022.

7. World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Stastistics. 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/486722075.

8. Northoff G et al. Mov Disord. May 1999;14(3):404-16. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<404::AID-MDS1004>3.0.CO;2-5.

9. Walther S et al. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;6(7):610-9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30474-7.

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome identified by its clinical phenotype. Unlike common psychiatric syndromes such as major depression that are characterized by self-report of symptoms, catatonia is identified chiefly by empirically evaluated signs on clinical evaluation. Its signs are recognized through observation, physical examination, or elicitation by clinical maneuvers or the presentation of stimuli. However, catatonia is often overlooked even though its clinical signs are often visibly apparent, including to the casual observer.

Why is catatonia underdiagnosed? A key modifiable factor appears to be a prevalent misunderstanding over what catatonia looks like.1 We have sought to address this in a few ways.

First identified was the need for comprehensive educational resources on how to assess for and recognize catatonia. Using the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale – the most widely used scale for catatonia in both research and clinical settings and the most cited publication in the catatonia literature– our team developed the BFCRS Training Manual and Coding Guide.2,3 This manual expands on the definitions of each BFCRS item based on how it was originally operationalized by the scale’s authors. Subsequently, we created a comprehensive set of educational resources including videos illustrating how to assess for catatonia, a video for each of the 23 items on the BFCRS, and self-assessment tools. All resources are freely available online at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.4

Through this project it became apparent that there are many discrepancies across the field regarding the phenotype of catatonia. Specifically, a recent review inspired by this project set about to characterize the scope of distinctions across diagnostic systems and rating scales.5 For instance, each diagnostic system and rating scale includes a unique set of signs, approaches diagnostic thresholds differently, and often operationalizes clinical features in ways that lead either to criterion overlap (for example, combativeness would be scored both as combativeness and agitation on ICD-11) or contradictions with other systems or scales (for example, varied definitions of waxy flexibility). In the face of so many inconsistencies, what is a clinician to do? What follows is a discussion of how to apply the insights from this recent review in clinical and research settings.

Starting with DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 – the current editions of the two leading diagnostic systems – one might ask: How do they compare?6,7 Overall, these two systems are broadly aligned in terms of the catatonic syndrome. Both systems identify individual clinical signs (as opposed to symptom complexes). Both require three features as a diagnostic threshold. Most of the same clinical signs are included in both systems, and the definitions of individual items are largely equivalent. Additionally, both systems allow for diagnosis of catatonia in association with psychiatric and medical conditions and include a category for unspecified catatonia.

Despite these core agreements, though, there are several important distinctions. First, whereas all 12 signs included in DSM-5-TR count toward an ICD-11 catatonia diagnosis, the opposite cannot be said. ICD-11 includes several features that are not in DSM-5-TR: rigidity, verbigeration, withdrawal, staring, ambitendency, impulsivity, and combativeness. Next, autonomic abnormality, which signifies the most severe type of catatonia called malignant catatonia, is included as a potential comorbidity in ICD-11 but not mentioned in DSM-5-TR. Third, ICD-11 includes a separate diagnosis for substance-induced catatonia, whereas this condition would be diagnosed as unspecified catatonia in DSM-5-TR.

There are also elements missing from both systems. The most notable of these is that neither system specifies the period over which findings must be present for diagnosis. By clinical convention, the practical definition of 24 hours is appropriate in most instances. The clinical features identified during direct evaluation are usually sufficient for diagnosis, but additional signs observed or documented over the prior 24 hours should be incorporated as part of the clinical evaluation. Another distinction is how to handle clinical features before and after lorazepam challenge. As noted in the BFCRS Training Manual, it would be appropriate to compare “state assessments” (that is, restricted to features identified only during direct, in-person assessment) from before and after lorazepam administration to document improvement.4

Whereas DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 are broadly in agreement, comparing these systems with catatonia rating scales reveals many sources of potential confusion, but also concrete guidance on operationalizing individual items.5 How exactly should each of catatonia’s clinical signs be defined? Descriptions differ, and thresholds of duration and frequency vary considerably across scales. As a result, clinicians who use different scales and then convert these results to diagnostic criteria are liable to come to different clinical conclusions. For instance, both echophenomena and negativism must be elicited more than five times to be scored per Northoff,8 but even a single convincing instance of either would be scored on the BFCRS as “occasional.”2

Such discrepancies are important because, whereas the psychometric properties of several catatonia scales have been documented, there are no analogous studies on the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 criteria. Therefore, it is essential for clinicians and researchers to document how diagnostic criteria have been operationalized. The most practical and evidence-based way to do this is to use a clinically validated scale and convert these to diagnostic criteria, yet in doing so a few modifications will be necessary.

Of the available clinical scales, the BFCRS is best positioned for clinical use. The BFCRS has been validated clinically and has good reliability, detailed item definitions and audiovisual examples available. In addition, it is the only scale with a published semistructured evaluation (see initial paper and Training Manual), which takes about 5 minutes.2,4 In terms of utility, all 12 signs included by DSM-5-TR are among the first 14 items on the BFCRS, which constitutes a standalone tool known as the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI, see Table).

Many fundamental questions remain about catatonia,but the importance of a shared understanding of its clinical features is clear.9 Catatonia should be on the differential whenever a patient exhibits a markedly altered level of activity or grossly abnormal behavior, especially when inappropriate to context. We encourage readers to familiarize themselves with the phenotype of catatonia through online educational resources4 because the optimal care of patients with catatonia requires – at a minimum – that we know what we’re looking for.

Dr. Oldham is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center. Dr. Francis is professor of psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey. The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest. Funding for the educational project hosted at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu was provided by the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Dr. Oldham is currently supported by a K23 career development award from the National Institute on Aging (AG072383). The educational resources referenced in this piece could not have been created were it not for the intellectual and thespian collaboration of Joshua R. Wortzel, MD, who is currently a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Brown University, Providence, R.I. The authors are also indebted to Hochang B. Lee, MD, for his gracious support of this project.

References

1. Wortzel JR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 17;82(5):21m14025. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14025.

2. Bush G et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996 Feb;93(2):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x.

3. Weleff J et al. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023 Jan-Feb;64(1):13-27. doi:10.1016/j.jaclp.2022.07.002.

4. Oldham MA et al. Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale Assessment Resources. University of Rochester Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry. https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.

5. Oldham MA. Schizophr Res. 2022 Aug 19;S0920-9964(22)00294-8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.08.002.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022.

7. World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Stastistics. 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/486722075.

8. Northoff G et al. Mov Disord. May 1999;14(3):404-16. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<404::AID-MDS1004>3.0.CO;2-5.

9. Walther S et al. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;6(7):610-9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30474-7.

Catatonia is a psychomotor syndrome identified by its clinical phenotype. Unlike common psychiatric syndromes such as major depression that are characterized by self-report of symptoms, catatonia is identified chiefly by empirically evaluated signs on clinical evaluation. Its signs are recognized through observation, physical examination, or elicitation by clinical maneuvers or the presentation of stimuli. However, catatonia is often overlooked even though its clinical signs are often visibly apparent, including to the casual observer.

Why is catatonia underdiagnosed? A key modifiable factor appears to be a prevalent misunderstanding over what catatonia looks like.1 We have sought to address this in a few ways.

First identified was the need for comprehensive educational resources on how to assess for and recognize catatonia. Using the Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale – the most widely used scale for catatonia in both research and clinical settings and the most cited publication in the catatonia literature– our team developed the BFCRS Training Manual and Coding Guide.2,3 This manual expands on the definitions of each BFCRS item based on how it was originally operationalized by the scale’s authors. Subsequently, we created a comprehensive set of educational resources including videos illustrating how to assess for catatonia, a video for each of the 23 items on the BFCRS, and self-assessment tools. All resources are freely available online at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.4

Through this project it became apparent that there are many discrepancies across the field regarding the phenotype of catatonia. Specifically, a recent review inspired by this project set about to characterize the scope of distinctions across diagnostic systems and rating scales.5 For instance, each diagnostic system and rating scale includes a unique set of signs, approaches diagnostic thresholds differently, and often operationalizes clinical features in ways that lead either to criterion overlap (for example, combativeness would be scored both as combativeness and agitation on ICD-11) or contradictions with other systems or scales (for example, varied definitions of waxy flexibility). In the face of so many inconsistencies, what is a clinician to do? What follows is a discussion of how to apply the insights from this recent review in clinical and research settings.

Starting with DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 – the current editions of the two leading diagnostic systems – one might ask: How do they compare?6,7 Overall, these two systems are broadly aligned in terms of the catatonic syndrome. Both systems identify individual clinical signs (as opposed to symptom complexes). Both require three features as a diagnostic threshold. Most of the same clinical signs are included in both systems, and the definitions of individual items are largely equivalent. Additionally, both systems allow for diagnosis of catatonia in association with psychiatric and medical conditions and include a category for unspecified catatonia.

Despite these core agreements, though, there are several important distinctions. First, whereas all 12 signs included in DSM-5-TR count toward an ICD-11 catatonia diagnosis, the opposite cannot be said. ICD-11 includes several features that are not in DSM-5-TR: rigidity, verbigeration, withdrawal, staring, ambitendency, impulsivity, and combativeness. Next, autonomic abnormality, which signifies the most severe type of catatonia called malignant catatonia, is included as a potential comorbidity in ICD-11 but not mentioned in DSM-5-TR. Third, ICD-11 includes a separate diagnosis for substance-induced catatonia, whereas this condition would be diagnosed as unspecified catatonia in DSM-5-TR.

There are also elements missing from both systems. The most notable of these is that neither system specifies the period over which findings must be present for diagnosis. By clinical convention, the practical definition of 24 hours is appropriate in most instances. The clinical features identified during direct evaluation are usually sufficient for diagnosis, but additional signs observed or documented over the prior 24 hours should be incorporated as part of the clinical evaluation. Another distinction is how to handle clinical features before and after lorazepam challenge. As noted in the BFCRS Training Manual, it would be appropriate to compare “state assessments” (that is, restricted to features identified only during direct, in-person assessment) from before and after lorazepam administration to document improvement.4

Whereas DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 are broadly in agreement, comparing these systems with catatonia rating scales reveals many sources of potential confusion, but also concrete guidance on operationalizing individual items.5 How exactly should each of catatonia’s clinical signs be defined? Descriptions differ, and thresholds of duration and frequency vary considerably across scales. As a result, clinicians who use different scales and then convert these results to diagnostic criteria are liable to come to different clinical conclusions. For instance, both echophenomena and negativism must be elicited more than five times to be scored per Northoff,8 but even a single convincing instance of either would be scored on the BFCRS as “occasional.”2

Such discrepancies are important because, whereas the psychometric properties of several catatonia scales have been documented, there are no analogous studies on the DSM-5-TR and ICD-11 criteria. Therefore, it is essential for clinicians and researchers to document how diagnostic criteria have been operationalized. The most practical and evidence-based way to do this is to use a clinically validated scale and convert these to diagnostic criteria, yet in doing so a few modifications will be necessary.

Of the available clinical scales, the BFCRS is best positioned for clinical use. The BFCRS has been validated clinically and has good reliability, detailed item definitions and audiovisual examples available. In addition, it is the only scale with a published semistructured evaluation (see initial paper and Training Manual), which takes about 5 minutes.2,4 In terms of utility, all 12 signs included by DSM-5-TR are among the first 14 items on the BFCRS, which constitutes a standalone tool known as the Bush-Francis Catatonia Screening Instrument (BFCSI, see Table).

Many fundamental questions remain about catatonia,but the importance of a shared understanding of its clinical features is clear.9 Catatonia should be on the differential whenever a patient exhibits a markedly altered level of activity or grossly abnormal behavior, especially when inappropriate to context. We encourage readers to familiarize themselves with the phenotype of catatonia through online educational resources4 because the optimal care of patients with catatonia requires – at a minimum – that we know what we’re looking for.

Dr. Oldham is assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of Rochester (N.Y.) Medical Center. Dr. Francis is professor of psychiatry at Penn State University, Hershey. The authors declare no relevant conflicts of interest. Funding for the educational project hosted at https://bfcrs.urmc.edu was provided by the department of psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center. Dr. Oldham is currently supported by a K23 career development award from the National Institute on Aging (AG072383). The educational resources referenced in this piece could not have been created were it not for the intellectual and thespian collaboration of Joshua R. Wortzel, MD, who is currently a fellow in child and adolescent psychiatry at Brown University, Providence, R.I. The authors are also indebted to Hochang B. Lee, MD, for his gracious support of this project.

References

1. Wortzel JR et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2021 Aug 17;82(5):21m14025. doi: 10.4088/JCP.21m14025.

2. Bush G et al. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996 Feb;93(2):129-36. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09814.x.

3. Weleff J et al. J Acad Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2023 Jan-Feb;64(1):13-27. doi:10.1016/j.jaclp.2022.07.002.

4. Oldham MA et al. Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale Assessment Resources. University of Rochester Medical Center, Department of Psychiatry. https://bfcrs.urmc.edu.

5. Oldham MA. Schizophr Res. 2022 Aug 19;S0920-9964(22)00294-8. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2022.08.002.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5-TR. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing, 2022.

7. World Health Organization. ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Stastistics. 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en#/http://id.who.int/icd/entity/486722075.

8. Northoff G et al. Mov Disord. May 1999;14(3):404-16. doi: 10.1002/1531-8257(199905)14:3<404::AID-MDS1004>3.0.CO;2-5.

9. Walther S et al. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2019 Jul;6(7):610-9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30474-7.