User login

Comments & Controversies

The perils of hubris

Dr. Nasrallah’s fascinating editorial on the psychiatric aspects of prominent individuals’ fall from grace (“From famous to infamous: Psychiatric aspects of the fall from grace,” From the Editor,

Perhaps fittingly, the phenomenon of self-destruction as a byproduct of success was most prominently “diagnosed” by business school professors, not physicians. The propensity for ethical failure at the apex of achievement was coined the “Bathsheba Syndrome,” in reference to the biblical tale of King David’s degenerative sequence of temptation, infidelity, deceit, and treachery while at the height of his power.2 David’s transgressions are enabled by the very success he has achieved.3

One of my valued mentors had an interesting, albeit unscientific, method of mitigating hubris. When he was a senior military lawyer, or judge advocate (JAG), and I was a junior one, my mentor took me to a briefing in which he provided a legal overview to newly minted colonels assuming command billets. One of the functions of JAGs is to provide counsel and advice to commanders. As Dr. Nasrallah noted in his editorial, military leaders are by no means immune from the proverbial fall from grace, and arguably particularly susceptible to it. In beginning his remarks, my mentor offered his heartfelt congratulations to the attendees on their promotion and then proceeded to hand out a pocket mirror for them to pass around. He asked each officer to look in the mirror and personally confirm for him that they were just as unattractive today as they were yesterday.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

The views expressed in this letter are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency.

1. Wolfe T. Bonfire of the vanities. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1987.

2. Ludwig DC, Longenecker CO. The Bathsheba syndrome: the ethical failure of successful leaders. J Bus Ethics. 1993;12:265-273.

3. 2 Samuel 11-12.

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial and his discussion of the dangers of hubris. This brought to mind the role of the auriga in ancient Rome: "the auriga was a slave with gladiator status, whose duty it was to drive a biga, the light vehicle powered by two horses, to transport some important Romans, mainly duces (military commanders). An auriga was a sort of “chauffeur” for important men and was carefully selected from among trustworthy slaves only. It has been supposed also that this name was given to the slave who held a laurel crown, during Roman Triumphs, over the head of the dux, standing at his back but continuously whispering in his ears “Memento Mori” (“remember you are mortal”) to prevent the celebrated commander from losing his sense of proportion in the excesses of the celebrations.”1

Continue to: Mark S. Komrad, MD...

Mark S. Komrad, MD

Faculty of Psychiatry

Johns Hopkins Hospital

University of Maryland

Tulane University

Towson, Maryland

Reference

1. Auriga (slave). Accessed November 9, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auriga_(slave)

Barriers to care faced by African American patients

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the 5 domains of social determinants of health are Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context.1 Patients who are African American face many socioeconomic barriers to access to psychiatric care, including economic inequality, inadequate knowledge about mental health, and deficient social environments. These barriers have a significant impact on the accessibility of psychiatric health care within this community, and they need to be addressed.

Jegede et al2 discussed how financial woes and insecurity within the African American community contribute to health care inequalities and adverse health outcomes. According to the US Census Bureau,in 2020, compared to other ethnic groups, African American individuals had the lowest median income.3 Alang4 discussed how the stigma of mental health was a barrier among younger, college-educated individuals who are African American, and that those with higher education were more likely to minimize and report low treatment effectiveness. As clinicians, we often fail to discuss the effects the perceived social and cultural stigma of being diagnosed with a substance use or mental health disorder has on seeking care, treatment, and therapy by African American patients. The stigma of being judged by family members or the community and being seen as “weak” for seeking treatment has a detrimental impact on access to psychiatric care.2 It is our duty as clinicians to understand these kinds of stigmas and seek ways to mitigate them within this community.

Also, we must not underestimate the importance of patients having access to transportation to treatment. We know that social support is integral to treatment, recovery, and relapse prevention. Chronic cycles of treatment and relapse can occur due to inadequate social support. Having access to a reliable driver—especially one who is a family member or member of the community—can be vital to establishing social support. Jegede et al2 found that access to adequate transportation has proven therapeutic benefits and lessens the risk of relapse with decreased exposure to risky environments. We need to devise solutions to help patients find adequate and reliable transportation.

Clinicians should be culturally mindful and aware of the barriers to psychiatric care faced by patients who are African American. They should understand the importance of removing these barriers, and work to improve this population’s access to psychiatric care. Though this may be a daunting task that requires considerable time and resources, as health care providers, we can start the process by communicating and working with local politicians and community leaders. By working together, we can develop a plan to combat these socioeconomic barriers and provide access to psychiatric care within the African American community.

Craig Perry, MD

Elohor Otite, MD

Stacy Doumas, MD

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

- Healthy People 2030, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

2. Jegede O, Muvvala S, Katehis E, et al. Perceived barriers to access care, anticipated discrimination and structural vulnerability among African Americans with substance use disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(2):136-143.

3. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-273, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. US Government Publishing Office; 2021.

The perils of hubris

Dr. Nasrallah’s fascinating editorial on the psychiatric aspects of prominent individuals’ fall from grace (“From famous to infamous: Psychiatric aspects of the fall from grace,” From the Editor,

Perhaps fittingly, the phenomenon of self-destruction as a byproduct of success was most prominently “diagnosed” by business school professors, not physicians. The propensity for ethical failure at the apex of achievement was coined the “Bathsheba Syndrome,” in reference to the biblical tale of King David’s degenerative sequence of temptation, infidelity, deceit, and treachery while at the height of his power.2 David’s transgressions are enabled by the very success he has achieved.3

One of my valued mentors had an interesting, albeit unscientific, method of mitigating hubris. When he was a senior military lawyer, or judge advocate (JAG), and I was a junior one, my mentor took me to a briefing in which he provided a legal overview to newly minted colonels assuming command billets. One of the functions of JAGs is to provide counsel and advice to commanders. As Dr. Nasrallah noted in his editorial, military leaders are by no means immune from the proverbial fall from grace, and arguably particularly susceptible to it. In beginning his remarks, my mentor offered his heartfelt congratulations to the attendees on their promotion and then proceeded to hand out a pocket mirror for them to pass around. He asked each officer to look in the mirror and personally confirm for him that they were just as unattractive today as they were yesterday.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

The views expressed in this letter are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency.

1. Wolfe T. Bonfire of the vanities. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1987.

2. Ludwig DC, Longenecker CO. The Bathsheba syndrome: the ethical failure of successful leaders. J Bus Ethics. 1993;12:265-273.

3. 2 Samuel 11-12.

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial and his discussion of the dangers of hubris. This brought to mind the role of the auriga in ancient Rome: "the auriga was a slave with gladiator status, whose duty it was to drive a biga, the light vehicle powered by two horses, to transport some important Romans, mainly duces (military commanders). An auriga was a sort of “chauffeur” for important men and was carefully selected from among trustworthy slaves only. It has been supposed also that this name was given to the slave who held a laurel crown, during Roman Triumphs, over the head of the dux, standing at his back but continuously whispering in his ears “Memento Mori” (“remember you are mortal”) to prevent the celebrated commander from losing his sense of proportion in the excesses of the celebrations.”1

Continue to: Mark S. Komrad, MD...

Mark S. Komrad, MD

Faculty of Psychiatry

Johns Hopkins Hospital

University of Maryland

Tulane University

Towson, Maryland

Reference

1. Auriga (slave). Accessed November 9, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auriga_(slave)

Barriers to care faced by African American patients

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the 5 domains of social determinants of health are Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context.1 Patients who are African American face many socioeconomic barriers to access to psychiatric care, including economic inequality, inadequate knowledge about mental health, and deficient social environments. These barriers have a significant impact on the accessibility of psychiatric health care within this community, and they need to be addressed.

Jegede et al2 discussed how financial woes and insecurity within the African American community contribute to health care inequalities and adverse health outcomes. According to the US Census Bureau,in 2020, compared to other ethnic groups, African American individuals had the lowest median income.3 Alang4 discussed how the stigma of mental health was a barrier among younger, college-educated individuals who are African American, and that those with higher education were more likely to minimize and report low treatment effectiveness. As clinicians, we often fail to discuss the effects the perceived social and cultural stigma of being diagnosed with a substance use or mental health disorder has on seeking care, treatment, and therapy by African American patients. The stigma of being judged by family members or the community and being seen as “weak” for seeking treatment has a detrimental impact on access to psychiatric care.2 It is our duty as clinicians to understand these kinds of stigmas and seek ways to mitigate them within this community.

Also, we must not underestimate the importance of patients having access to transportation to treatment. We know that social support is integral to treatment, recovery, and relapse prevention. Chronic cycles of treatment and relapse can occur due to inadequate social support. Having access to a reliable driver—especially one who is a family member or member of the community—can be vital to establishing social support. Jegede et al2 found that access to adequate transportation has proven therapeutic benefits and lessens the risk of relapse with decreased exposure to risky environments. We need to devise solutions to help patients find adequate and reliable transportation.

Clinicians should be culturally mindful and aware of the barriers to psychiatric care faced by patients who are African American. They should understand the importance of removing these barriers, and work to improve this population’s access to psychiatric care. Though this may be a daunting task that requires considerable time and resources, as health care providers, we can start the process by communicating and working with local politicians and community leaders. By working together, we can develop a plan to combat these socioeconomic barriers and provide access to psychiatric care within the African American community.

Craig Perry, MD

Elohor Otite, MD

Stacy Doumas, MD

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

The perils of hubris

Dr. Nasrallah’s fascinating editorial on the psychiatric aspects of prominent individuals’ fall from grace (“From famous to infamous: Psychiatric aspects of the fall from grace,” From the Editor,

Perhaps fittingly, the phenomenon of self-destruction as a byproduct of success was most prominently “diagnosed” by business school professors, not physicians. The propensity for ethical failure at the apex of achievement was coined the “Bathsheba Syndrome,” in reference to the biblical tale of King David’s degenerative sequence of temptation, infidelity, deceit, and treachery while at the height of his power.2 David’s transgressions are enabled by the very success he has achieved.3

One of my valued mentors had an interesting, albeit unscientific, method of mitigating hubris. When he was a senior military lawyer, or judge advocate (JAG), and I was a junior one, my mentor took me to a briefing in which he provided a legal overview to newly minted colonels assuming command billets. One of the functions of JAGs is to provide counsel and advice to commanders. As Dr. Nasrallah noted in his editorial, military leaders are by no means immune from the proverbial fall from grace, and arguably particularly susceptible to it. In beginning his remarks, my mentor offered his heartfelt congratulations to the attendees on their promotion and then proceeded to hand out a pocket mirror for them to pass around. He asked each officer to look in the mirror and personally confirm for him that they were just as unattractive today as they were yesterday.

Charles G. Kels, JD

Defense Health Agency

San Antonio, Texas

The views expressed in this letter are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any government agency.

1. Wolfe T. Bonfire of the vanities. Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 1987.

2. Ludwig DC, Longenecker CO. The Bathsheba syndrome: the ethical failure of successful leaders. J Bus Ethics. 1993;12:265-273.

3. 2 Samuel 11-12.

I enjoyed Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial and his discussion of the dangers of hubris. This brought to mind the role of the auriga in ancient Rome: "the auriga was a slave with gladiator status, whose duty it was to drive a biga, the light vehicle powered by two horses, to transport some important Romans, mainly duces (military commanders). An auriga was a sort of “chauffeur” for important men and was carefully selected from among trustworthy slaves only. It has been supposed also that this name was given to the slave who held a laurel crown, during Roman Triumphs, over the head of the dux, standing at his back but continuously whispering in his ears “Memento Mori” (“remember you are mortal”) to prevent the celebrated commander from losing his sense of proportion in the excesses of the celebrations.”1

Continue to: Mark S. Komrad, MD...

Mark S. Komrad, MD

Faculty of Psychiatry

Johns Hopkins Hospital

University of Maryland

Tulane University

Towson, Maryland

Reference

1. Auriga (slave). Accessed November 9, 2021. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Auriga_(slave)

Barriers to care faced by African American patients

According to the US Department of Health and Human Services, the 5 domains of social determinants of health are Economic Stability, Education Access and Quality, Health Care Access and Quality, Neighborhood and Built Environment, and Social and Community Context.1 Patients who are African American face many socioeconomic barriers to access to psychiatric care, including economic inequality, inadequate knowledge about mental health, and deficient social environments. These barriers have a significant impact on the accessibility of psychiatric health care within this community, and they need to be addressed.

Jegede et al2 discussed how financial woes and insecurity within the African American community contribute to health care inequalities and adverse health outcomes. According to the US Census Bureau,in 2020, compared to other ethnic groups, African American individuals had the lowest median income.3 Alang4 discussed how the stigma of mental health was a barrier among younger, college-educated individuals who are African American, and that those with higher education were more likely to minimize and report low treatment effectiveness. As clinicians, we often fail to discuss the effects the perceived social and cultural stigma of being diagnosed with a substance use or mental health disorder has on seeking care, treatment, and therapy by African American patients. The stigma of being judged by family members or the community and being seen as “weak” for seeking treatment has a detrimental impact on access to psychiatric care.2 It is our duty as clinicians to understand these kinds of stigmas and seek ways to mitigate them within this community.

Also, we must not underestimate the importance of patients having access to transportation to treatment. We know that social support is integral to treatment, recovery, and relapse prevention. Chronic cycles of treatment and relapse can occur due to inadequate social support. Having access to a reliable driver—especially one who is a family member or member of the community—can be vital to establishing social support. Jegede et al2 found that access to adequate transportation has proven therapeutic benefits and lessens the risk of relapse with decreased exposure to risky environments. We need to devise solutions to help patients find adequate and reliable transportation.

Clinicians should be culturally mindful and aware of the barriers to psychiatric care faced by patients who are African American. They should understand the importance of removing these barriers, and work to improve this population’s access to psychiatric care. Though this may be a daunting task that requires considerable time and resources, as health care providers, we can start the process by communicating and working with local politicians and community leaders. By working together, we can develop a plan to combat these socioeconomic barriers and provide access to psychiatric care within the African American community.

Craig Perry, MD

Elohor Otite, MD

Stacy Doumas, MD

Jersey Shore University Medical Center

Neptune, New Jersey

- Healthy People 2030, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

2. Jegede O, Muvvala S, Katehis E, et al. Perceived barriers to access care, anticipated discrimination and structural vulnerability among African Americans with substance use disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(2):136-143.

3. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-273, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. US Government Publishing Office; 2021.

- Healthy People 2030, US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social determinants of health. Accessed November 9, 2021. https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

2. Jegede O, Muvvala S, Katehis E, et al. Perceived barriers to access care, anticipated discrimination and structural vulnerability among African Americans with substance use disorders. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(2):136-143.

3. Shrider EA, Kollar M, Chen F, et al. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports, P60-273, Income and Poverty in the United States: 2020. US Government Publishing Office; 2021.

Medical ethics in the time of COVID-19

It is clear that the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic is one of the most extraordinary epochs of our professional and personal lives. Besides the challenges to the techniques and technologies of care for this illness, we are seeing challenges to the fundamentals of health care, both to the systems whereby it is delivered, and to the ethical principles that guide that delivery. There is unprecedented relevance of certain ethical issues in the practice of medicine, many of which have previously been discussed in classrooms and textbooks, but now are at play in daily practice, particularly at the frontlines of the war against COVID-19.1 In this article, I highlight several ethical dilemmas that are salient to these unique times. Some of the most compelling issues can be sorted into 2 clearly overlapping domains: triage ethics and equity ethics.

Triage ethics

In the areas most greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, scarcity of treatment resources, such as ventilators, is a legitimate concern. French surgeon Dominique Jean Larry was the first to establish medical sorting protocols in the context of the battles of the Napoleonic wars, for which he used the French word triage, meaning “sorting.”2 He articulated 3 prognostic categories: 1) those who would die even with treatment, 2) those who would live without treatment, and 3) those who would die unless treated. Triage decisions arise in the context of insufficient resources, particularly space, staff, and supplies. Although usually identified with disasters, these decisions can arise in other contexts where personnel or technological resources are inadequate. Indeed, one of the first modern incarnations of triage ethics in American civilian life was in the early days of hemodialysis, when so-called “God committees” made complex decisions about which patients would be able to use this new, rare technology.3

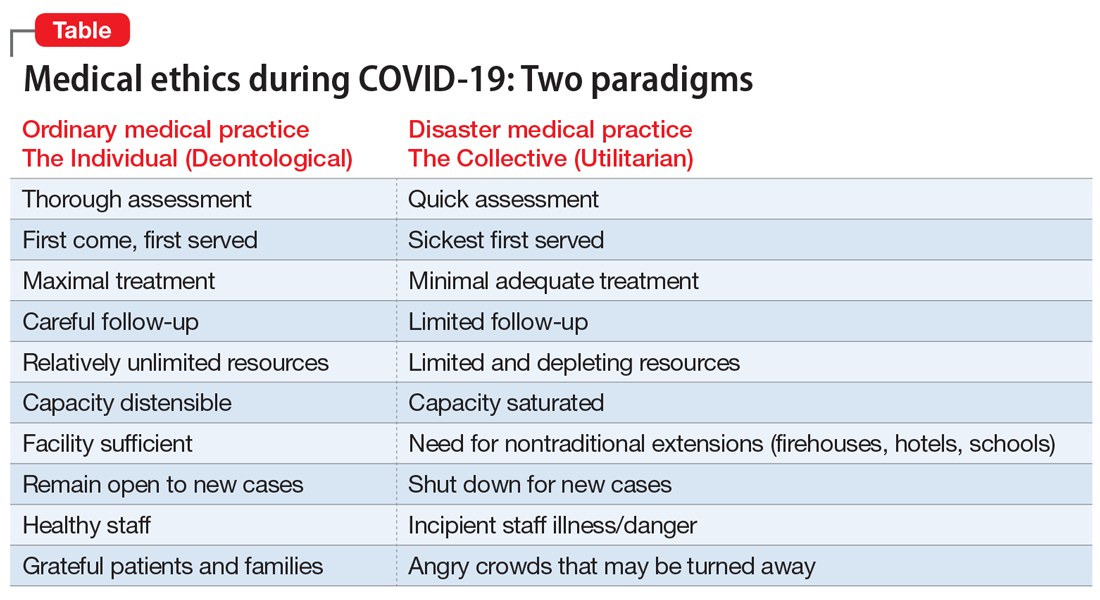

Two fundamental moral constructs undergird medical ethics: deontological and utilitarian. The former, in which most clinicians traffic in ordinary practice, is driven by principles or moral rules such as the sanctity of life, the rule of fairness, and the principle of autonomy.4 They apply primarily in the context of treating an individual patient. The utilitarian way of reasoning is not as familiar to clinicians. It is focused on the broader context, the common good, the health of the group. It asks to calculate “the greatest good for the greatest number” as a means of navigating ethical dilemmas.5 The utilitarian perspective is far more familiar to policymakers, health care administrators, and public health professionals. It tends to be anathema to clinicians. However, disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic ask some clinicians, particularly inpatient physicians, to shift from their usual deontological perspective to a utilitarian one, because triage ethics fundamentally draw on utilitarian reasoning. This can be quite anguishing to clinicians who typically work with individual patients in settings of more adequate, if not abundant, resources. What may feel wrong in a deontological mode can be seen as ethically right in a utilitarian framework.

The Table compares and contrasts these 2 paradigms and how they manifest in the clinical trenches, in a protracted health care crisis with limited resources.

The COVID-19 crisis has produced an unprecedented and extended exposure of clinicians to triage situations in the face of limited resources such as ventilators, personnel, personal protective equipment, etc.6 Numerous possible approaches to deploying limited supplies are being considered. On what basis should such decisions be made? How can fairness be optimally manifest? Some possibilities include:

- first come, first served

- youngest first

- lottery

- short-term survivability

- long-term prognosis for quality of life

- value of a patient to the lives of others (eg, parents, health care workers, vaccine researchers).

One particularly interesting exploration of these questions was done in Maryland and reported in the “Maryland Framework for the Allocation of Scarce Life-sustaining Medical Resources in a Catastrophic Public Health Emergency.”7 This was the product of a multi-year consultation, ending in 2017, with several constituencies, including clinicians, politicians, hospital administrators, and members of the public brainstorming about approaches to allocating a hypothetical scarcity of ventilators. Interestingly, there was one broad consensus among these groups: a ventilator should not be withdrawn from a patient already using it to give to a “better” candidate who comes along later.

Some institutions have developed a method of making triage decisions that takes such decisions out of the hands of individual clinicians and instead assigns them to specialized “triage teams” made up of ethicists and clinicians experienced in critical care, to develop more distance from the emotions at the bedside. To minimize bias, such teams are often insulated from getting personal information about the patient, and receive only acute clinical information.8

Continue to: The pros and cons of these approaches...

The pros and cons of these approaches and the underlying ethical reasoning is beyond the scope of this overview. Policy documents from different states, regions, nations, and institutions have various approaches to making these choices. Presently, there is no coherent national or international agreement on triage ethics.9 It is important, however, that there be transparency in whatever approach an institution adopts for triage decisions.

Equity ethics

Though the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by the COVID-19 crisis. Race, sex, age, socioeconomic class, and type of illness have all been perennial sources of division between those who have better or worse access to health care and its outcomes. All of these distinctions have created differentials in rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic.10

The shifting of acute health care facilities to mostly COVID-19–related treatment, and postponing less critical and more “elective” care, creates a divide based on illness type. Many facilities have stopped taking admissions for other kinds of cases. This is particularly relevant to psychiatric units, many of which have had to decrease their bed capacities to make all rooms private, and limit their usual treatments offered to inpatients.11 Many long-term units, such as at state hospitals, are closing to new admissions. Many day hospitals and intensive outpatient programs remain closed, not even shifting to telehealth. In areas most affected by COVID-19, some institutions have closed psychiatric wards and reallocated psychiatrists to cover some of the medical units. So the availability of the more intensive, institutionally-based levels of care is significantly reduced, particularly for psychiatric patients.12 These patients already are a disadvantaged population in the distribution of health care resources, and the care of individuals with serious mental illness is more likely to be seen as “nonessential” in this time of suddenly scarcer institutional resources.

One of the cherished ethical values in health care is autonomy, and in a deontological triage environment, honoring patient autonomy is carefully and tenderly administered. However, in a utilitarian-driven triage environment, considerations of the common good can trump autonomy, even in subtle ways that create inequities. Clinicians have been advised to have more frank conversations with patients, particularly those with chronic illnesses, stepping up initiatives to make advanced directives during this crisis, explicitly reminding patients that there may not be enough ventilators for all who need one.13 Some have argued that such physician-initiated conversations can be inherently coercive, making these decisions not as autonomous as it may appear, similar to physicians suggesting medical euthanasia as an option.14 Interestingly, some jurisdictions that offer euthanasia have been suspending such services during the COVID-19 crisis.15 Some hospitals have even wrestled with the possibility that all COVID-19 admissions should be considered “do not resuscitate,” especially because cardiopulmonary resuscitation significantly elevates the risks of viral exposure for the treatment team.16,17 A more explicit example of how current standards protecting patient autonomy may be challenged is patients who are admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric unit. These are patients whose presumptively impaired autonomy is already being overridden by the involuntary nature of the admission. If a psychiatric unit requires admissions to be COVID-19–negative, and if patients refuse COVID-19 testing, should the testing be forced upon them to protect the entire milieu?

Many ethicists are highlighting the embedded equity bias known as “ableism” inherent in triage decisions—implicitly disfavoring resources for patients with COVID-19 who are already physically or intellectually disabled, chronically ill, aged, homeless, psychosocially low functioning, etc.18 Without explicit protections for individuals who are chronically disabled, triage decisions unguided by policy safeguards may reflexively favor the more “abled.” This bias towards the more abled is often inherent in how difficult it is to access health care. It can also be manifested in bedside triage decisions made in the moment by individual clinicians. Many disability rights advocates have been sounding this alarm during the COVID-19 crisis.19

Continue to: A special circumstance of equity...

A special circumstance of equity is arising during this ongoing pandemic—the possibility of treating health care workers as a privileged class. Unlike typical disasters, where health care workers come in afterwards, and therefore are in relatively less danger, pandemics create particularly high risks of danger for such individuals, with repeated exposure to the virus. They are both responders and potential victims. Should they have higher priority for ventilators, vaccines, funding, etc?6 This is a more robust degree of compensatory justice than merely giving appreciation. Giving health care workers such advantages may seem intuitively appealing, but perhaps professionalism and the self-obligation of duty mitigates such claims.20

A unique opportunity

The magnitude and pervasiveness of this pandemic crisis is unique in our lifetimes, as both professionals and as citizens. In the crucible of this extraordinary time, these and other medical ethics dilemmas burn hotter than ever before. Different societies and institutions may come up with different answers, based on their cultures and values. It is important, however, that the venerable ethos of medical ethics, which has evolved through the millennia, codified in oaths, codes, and scholarship, can be a compass at the bedside and in the meetings of legislatures, leaders, and policymakers. Perhaps we can emerge from this time with more clarity about how to balance the preciousness of individual rights with the needs of the common good.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought increased attention to triage ethics and equity ethics. There is no coherent national or international agreement on how to best deploy limited supplies such as ventilators and personal protective equipment. Although the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by COVID-19. Clinicians may be asked to view health care through the less familiar lens of the common good, as opposed to focusing strictly on an individual patient.

Related Resources

- Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Coronavirus ethics and policy insights and resources. https://bioethics.jhu.edu/research-and-outreach/covid-19-bioethics-expert-insights/.

- Daugherty-Biddison L, Gwon H, Regenberg A, et al. Maryland framework for the allocation of scarce lifesustaining medical resources in a catastrophic public health emergency. www.law.umaryland.edu/media/SOL/pdfs/Programs/Health-Law/MHECN/ASR%20Framework_Final.pdf.

1. AMA Journal of Ethics. COVID-19 ethics resource center. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/COVID-19-ethics-resource-center. Updated May 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

2. Skandakalis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, et al. “To afford the wounded speedy assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1392-1399.

3. Ross W. God panels and the history of hemodialysis in America: a cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(11):890-896.

4. Alexander L, Moore M. Deontological ethics. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/. Revised October 17, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2020.

5. Driver J. The history of utilitarianism. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/. Revised September 22, 2014. Accessed May 26, 2020.

6. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055.

7. Daugherty-Biddison EL, Faden R, Gwon HW, et al. Too many patients…a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019;155(4):848-854.

8. Dudzinski D, Campelia G, Brazg T. Pandemic resources including COVID-19 materials. Department of Bioethics and Humanities, University of Washington Medicine. http://depts.washington.edu/bhdept/ethics-medicine/bioethics-topics/detail/245. Published April 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

9. Antommaria AHM, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al; Task Force of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors [published online April 24, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020;M20-1738. doi: 10.7326/M20-1738.

10. Cooney E. Who gets hospitalized for COVID-19? Report shows differences by race and sex. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/09/hospitalized-COVID-19-patients-differences-by-race-and-sex/. Published April 9, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

11. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

12. American Psychiatric Association Ethics Committee. COVID-19 related opinions of the APA Ethics Committee. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Ethics/APA-COVID-19-Ethics-Opinions.pdf. Published May 5, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

13. Wee M. Coronavirus and the misuse of ‘do not resuscitate’ orders. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/coronavirus-and-the-misuse-of-do-not-resuscitate-orders. Published May 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

14. Prokopetz JZ, Lehmann LS. Redefining physicians’ role in assisted dying. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):97-99.

15. Yuill K, Boer T. What COVID-19 has revealed about euthanasia. spiked. https://www.spiked-online.com/2020/04/14/COVID-19-has-revealed-the-ugliness-of-euthanasia/. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

16. Plunkett AJ. COVID-19: hospitals should consider CoP carefully before deciding on DNR policy. PSQH. https://www.psqh.com/news/COVID-19-hospitals-should-consider-cop-carefully-before-deciding-on-dnr-policy/. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

17. Kramer DB, Lo B, Dickert NW. CPR in the COVID-19 era: an ethical framework [published online May 6, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2010758.

18. Mykitiuk R, Lemmens T. Assessing the value of a life: COVID-19 triage orders mustn’t work against those with disabilities. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-disabled-COVID-19-triage-orders-1.5532137. Published April 19, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

19. Solomon MZ, Wynia MK, Gostin LO. COVID-19 crisis triage—optimizing health outcomes and disability rights [published online May 19, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008300.

20. Appel JM. Ethics consult: who’s first to get COVID-19 Vax? MD/JD bangs gavel. MedPage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/COVID19/86260. Published May 1, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

It is clear that the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic is one of the most extraordinary epochs of our professional and personal lives. Besides the challenges to the techniques and technologies of care for this illness, we are seeing challenges to the fundamentals of health care, both to the systems whereby it is delivered, and to the ethical principles that guide that delivery. There is unprecedented relevance of certain ethical issues in the practice of medicine, many of which have previously been discussed in classrooms and textbooks, but now are at play in daily practice, particularly at the frontlines of the war against COVID-19.1 In this article, I highlight several ethical dilemmas that are salient to these unique times. Some of the most compelling issues can be sorted into 2 clearly overlapping domains: triage ethics and equity ethics.

Triage ethics

In the areas most greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, scarcity of treatment resources, such as ventilators, is a legitimate concern. French surgeon Dominique Jean Larry was the first to establish medical sorting protocols in the context of the battles of the Napoleonic wars, for which he used the French word triage, meaning “sorting.”2 He articulated 3 prognostic categories: 1) those who would die even with treatment, 2) those who would live without treatment, and 3) those who would die unless treated. Triage decisions arise in the context of insufficient resources, particularly space, staff, and supplies. Although usually identified with disasters, these decisions can arise in other contexts where personnel or technological resources are inadequate. Indeed, one of the first modern incarnations of triage ethics in American civilian life was in the early days of hemodialysis, when so-called “God committees” made complex decisions about which patients would be able to use this new, rare technology.3

Two fundamental moral constructs undergird medical ethics: deontological and utilitarian. The former, in which most clinicians traffic in ordinary practice, is driven by principles or moral rules such as the sanctity of life, the rule of fairness, and the principle of autonomy.4 They apply primarily in the context of treating an individual patient. The utilitarian way of reasoning is not as familiar to clinicians. It is focused on the broader context, the common good, the health of the group. It asks to calculate “the greatest good for the greatest number” as a means of navigating ethical dilemmas.5 The utilitarian perspective is far more familiar to policymakers, health care administrators, and public health professionals. It tends to be anathema to clinicians. However, disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic ask some clinicians, particularly inpatient physicians, to shift from their usual deontological perspective to a utilitarian one, because triage ethics fundamentally draw on utilitarian reasoning. This can be quite anguishing to clinicians who typically work with individual patients in settings of more adequate, if not abundant, resources. What may feel wrong in a deontological mode can be seen as ethically right in a utilitarian framework.

The Table compares and contrasts these 2 paradigms and how they manifest in the clinical trenches, in a protracted health care crisis with limited resources.

The COVID-19 crisis has produced an unprecedented and extended exposure of clinicians to triage situations in the face of limited resources such as ventilators, personnel, personal protective equipment, etc.6 Numerous possible approaches to deploying limited supplies are being considered. On what basis should such decisions be made? How can fairness be optimally manifest? Some possibilities include:

- first come, first served

- youngest first

- lottery

- short-term survivability

- long-term prognosis for quality of life

- value of a patient to the lives of others (eg, parents, health care workers, vaccine researchers).

One particularly interesting exploration of these questions was done in Maryland and reported in the “Maryland Framework for the Allocation of Scarce Life-sustaining Medical Resources in a Catastrophic Public Health Emergency.”7 This was the product of a multi-year consultation, ending in 2017, with several constituencies, including clinicians, politicians, hospital administrators, and members of the public brainstorming about approaches to allocating a hypothetical scarcity of ventilators. Interestingly, there was one broad consensus among these groups: a ventilator should not be withdrawn from a patient already using it to give to a “better” candidate who comes along later.

Some institutions have developed a method of making triage decisions that takes such decisions out of the hands of individual clinicians and instead assigns them to specialized “triage teams” made up of ethicists and clinicians experienced in critical care, to develop more distance from the emotions at the bedside. To minimize bias, such teams are often insulated from getting personal information about the patient, and receive only acute clinical information.8

Continue to: The pros and cons of these approaches...

The pros and cons of these approaches and the underlying ethical reasoning is beyond the scope of this overview. Policy documents from different states, regions, nations, and institutions have various approaches to making these choices. Presently, there is no coherent national or international agreement on triage ethics.9 It is important, however, that there be transparency in whatever approach an institution adopts for triage decisions.

Equity ethics

Though the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by the COVID-19 crisis. Race, sex, age, socioeconomic class, and type of illness have all been perennial sources of division between those who have better or worse access to health care and its outcomes. All of these distinctions have created differentials in rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic.10

The shifting of acute health care facilities to mostly COVID-19–related treatment, and postponing less critical and more “elective” care, creates a divide based on illness type. Many facilities have stopped taking admissions for other kinds of cases. This is particularly relevant to psychiatric units, many of which have had to decrease their bed capacities to make all rooms private, and limit their usual treatments offered to inpatients.11 Many long-term units, such as at state hospitals, are closing to new admissions. Many day hospitals and intensive outpatient programs remain closed, not even shifting to telehealth. In areas most affected by COVID-19, some institutions have closed psychiatric wards and reallocated psychiatrists to cover some of the medical units. So the availability of the more intensive, institutionally-based levels of care is significantly reduced, particularly for psychiatric patients.12 These patients already are a disadvantaged population in the distribution of health care resources, and the care of individuals with serious mental illness is more likely to be seen as “nonessential” in this time of suddenly scarcer institutional resources.

One of the cherished ethical values in health care is autonomy, and in a deontological triage environment, honoring patient autonomy is carefully and tenderly administered. However, in a utilitarian-driven triage environment, considerations of the common good can trump autonomy, even in subtle ways that create inequities. Clinicians have been advised to have more frank conversations with patients, particularly those with chronic illnesses, stepping up initiatives to make advanced directives during this crisis, explicitly reminding patients that there may not be enough ventilators for all who need one.13 Some have argued that such physician-initiated conversations can be inherently coercive, making these decisions not as autonomous as it may appear, similar to physicians suggesting medical euthanasia as an option.14 Interestingly, some jurisdictions that offer euthanasia have been suspending such services during the COVID-19 crisis.15 Some hospitals have even wrestled with the possibility that all COVID-19 admissions should be considered “do not resuscitate,” especially because cardiopulmonary resuscitation significantly elevates the risks of viral exposure for the treatment team.16,17 A more explicit example of how current standards protecting patient autonomy may be challenged is patients who are admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric unit. These are patients whose presumptively impaired autonomy is already being overridden by the involuntary nature of the admission. If a psychiatric unit requires admissions to be COVID-19–negative, and if patients refuse COVID-19 testing, should the testing be forced upon them to protect the entire milieu?

Many ethicists are highlighting the embedded equity bias known as “ableism” inherent in triage decisions—implicitly disfavoring resources for patients with COVID-19 who are already physically or intellectually disabled, chronically ill, aged, homeless, psychosocially low functioning, etc.18 Without explicit protections for individuals who are chronically disabled, triage decisions unguided by policy safeguards may reflexively favor the more “abled.” This bias towards the more abled is often inherent in how difficult it is to access health care. It can also be manifested in bedside triage decisions made in the moment by individual clinicians. Many disability rights advocates have been sounding this alarm during the COVID-19 crisis.19

Continue to: A special circumstance of equity...

A special circumstance of equity is arising during this ongoing pandemic—the possibility of treating health care workers as a privileged class. Unlike typical disasters, where health care workers come in afterwards, and therefore are in relatively less danger, pandemics create particularly high risks of danger for such individuals, with repeated exposure to the virus. They are both responders and potential victims. Should they have higher priority for ventilators, vaccines, funding, etc?6 This is a more robust degree of compensatory justice than merely giving appreciation. Giving health care workers such advantages may seem intuitively appealing, but perhaps professionalism and the self-obligation of duty mitigates such claims.20

A unique opportunity

The magnitude and pervasiveness of this pandemic crisis is unique in our lifetimes, as both professionals and as citizens. In the crucible of this extraordinary time, these and other medical ethics dilemmas burn hotter than ever before. Different societies and institutions may come up with different answers, based on their cultures and values. It is important, however, that the venerable ethos of medical ethics, which has evolved through the millennia, codified in oaths, codes, and scholarship, can be a compass at the bedside and in the meetings of legislatures, leaders, and policymakers. Perhaps we can emerge from this time with more clarity about how to balance the preciousness of individual rights with the needs of the common good.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought increased attention to triage ethics and equity ethics. There is no coherent national or international agreement on how to best deploy limited supplies such as ventilators and personal protective equipment. Although the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by COVID-19. Clinicians may be asked to view health care through the less familiar lens of the common good, as opposed to focusing strictly on an individual patient.

Related Resources

- Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Coronavirus ethics and policy insights and resources. https://bioethics.jhu.edu/research-and-outreach/covid-19-bioethics-expert-insights/.

- Daugherty-Biddison L, Gwon H, Regenberg A, et al. Maryland framework for the allocation of scarce lifesustaining medical resources in a catastrophic public health emergency. www.law.umaryland.edu/media/SOL/pdfs/Programs/Health-Law/MHECN/ASR%20Framework_Final.pdf.

It is clear that the coronavirus 2019 disease (COVID-19) pandemic is one of the most extraordinary epochs of our professional and personal lives. Besides the challenges to the techniques and technologies of care for this illness, we are seeing challenges to the fundamentals of health care, both to the systems whereby it is delivered, and to the ethical principles that guide that delivery. There is unprecedented relevance of certain ethical issues in the practice of medicine, many of which have previously been discussed in classrooms and textbooks, but now are at play in daily practice, particularly at the frontlines of the war against COVID-19.1 In this article, I highlight several ethical dilemmas that are salient to these unique times. Some of the most compelling issues can be sorted into 2 clearly overlapping domains: triage ethics and equity ethics.

Triage ethics

In the areas most greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, scarcity of treatment resources, such as ventilators, is a legitimate concern. French surgeon Dominique Jean Larry was the first to establish medical sorting protocols in the context of the battles of the Napoleonic wars, for which he used the French word triage, meaning “sorting.”2 He articulated 3 prognostic categories: 1) those who would die even with treatment, 2) those who would live without treatment, and 3) those who would die unless treated. Triage decisions arise in the context of insufficient resources, particularly space, staff, and supplies. Although usually identified with disasters, these decisions can arise in other contexts where personnel or technological resources are inadequate. Indeed, one of the first modern incarnations of triage ethics in American civilian life was in the early days of hemodialysis, when so-called “God committees” made complex decisions about which patients would be able to use this new, rare technology.3

Two fundamental moral constructs undergird medical ethics: deontological and utilitarian. The former, in which most clinicians traffic in ordinary practice, is driven by principles or moral rules such as the sanctity of life, the rule of fairness, and the principle of autonomy.4 They apply primarily in the context of treating an individual patient. The utilitarian way of reasoning is not as familiar to clinicians. It is focused on the broader context, the common good, the health of the group. It asks to calculate “the greatest good for the greatest number” as a means of navigating ethical dilemmas.5 The utilitarian perspective is far more familiar to policymakers, health care administrators, and public health professionals. It tends to be anathema to clinicians. However, disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic ask some clinicians, particularly inpatient physicians, to shift from their usual deontological perspective to a utilitarian one, because triage ethics fundamentally draw on utilitarian reasoning. This can be quite anguishing to clinicians who typically work with individual patients in settings of more adequate, if not abundant, resources. What may feel wrong in a deontological mode can be seen as ethically right in a utilitarian framework.

The Table compares and contrasts these 2 paradigms and how they manifest in the clinical trenches, in a protracted health care crisis with limited resources.

The COVID-19 crisis has produced an unprecedented and extended exposure of clinicians to triage situations in the face of limited resources such as ventilators, personnel, personal protective equipment, etc.6 Numerous possible approaches to deploying limited supplies are being considered. On what basis should such decisions be made? How can fairness be optimally manifest? Some possibilities include:

- first come, first served

- youngest first

- lottery

- short-term survivability

- long-term prognosis for quality of life

- value of a patient to the lives of others (eg, parents, health care workers, vaccine researchers).

One particularly interesting exploration of these questions was done in Maryland and reported in the “Maryland Framework for the Allocation of Scarce Life-sustaining Medical Resources in a Catastrophic Public Health Emergency.”7 This was the product of a multi-year consultation, ending in 2017, with several constituencies, including clinicians, politicians, hospital administrators, and members of the public brainstorming about approaches to allocating a hypothetical scarcity of ventilators. Interestingly, there was one broad consensus among these groups: a ventilator should not be withdrawn from a patient already using it to give to a “better” candidate who comes along later.

Some institutions have developed a method of making triage decisions that takes such decisions out of the hands of individual clinicians and instead assigns them to specialized “triage teams” made up of ethicists and clinicians experienced in critical care, to develop more distance from the emotions at the bedside. To minimize bias, such teams are often insulated from getting personal information about the patient, and receive only acute clinical information.8

Continue to: The pros and cons of these approaches...

The pros and cons of these approaches and the underlying ethical reasoning is beyond the scope of this overview. Policy documents from different states, regions, nations, and institutions have various approaches to making these choices. Presently, there is no coherent national or international agreement on triage ethics.9 It is important, however, that there be transparency in whatever approach an institution adopts for triage decisions.

Equity ethics

Though the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by the COVID-19 crisis. Race, sex, age, socioeconomic class, and type of illness have all been perennial sources of division between those who have better or worse access to health care and its outcomes. All of these distinctions have created differentials in rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in the COVID-19 pandemic.10

The shifting of acute health care facilities to mostly COVID-19–related treatment, and postponing less critical and more “elective” care, creates a divide based on illness type. Many facilities have stopped taking admissions for other kinds of cases. This is particularly relevant to psychiatric units, many of which have had to decrease their bed capacities to make all rooms private, and limit their usual treatments offered to inpatients.11 Many long-term units, such as at state hospitals, are closing to new admissions. Many day hospitals and intensive outpatient programs remain closed, not even shifting to telehealth. In areas most affected by COVID-19, some institutions have closed psychiatric wards and reallocated psychiatrists to cover some of the medical units. So the availability of the more intensive, institutionally-based levels of care is significantly reduced, particularly for psychiatric patients.12 These patients already are a disadvantaged population in the distribution of health care resources, and the care of individuals with serious mental illness is more likely to be seen as “nonessential” in this time of suddenly scarcer institutional resources.

One of the cherished ethical values in health care is autonomy, and in a deontological triage environment, honoring patient autonomy is carefully and tenderly administered. However, in a utilitarian-driven triage environment, considerations of the common good can trump autonomy, even in subtle ways that create inequities. Clinicians have been advised to have more frank conversations with patients, particularly those with chronic illnesses, stepping up initiatives to make advanced directives during this crisis, explicitly reminding patients that there may not be enough ventilators for all who need one.13 Some have argued that such physician-initiated conversations can be inherently coercive, making these decisions not as autonomous as it may appear, similar to physicians suggesting medical euthanasia as an option.14 Interestingly, some jurisdictions that offer euthanasia have been suspending such services during the COVID-19 crisis.15 Some hospitals have even wrestled with the possibility that all COVID-19 admissions should be considered “do not resuscitate,” especially because cardiopulmonary resuscitation significantly elevates the risks of viral exposure for the treatment team.16,17 A more explicit example of how current standards protecting patient autonomy may be challenged is patients who are admitted involuntarily to a psychiatric unit. These are patients whose presumptively impaired autonomy is already being overridden by the involuntary nature of the admission. If a psychiatric unit requires admissions to be COVID-19–negative, and if patients refuse COVID-19 testing, should the testing be forced upon them to protect the entire milieu?

Many ethicists are highlighting the embedded equity bias known as “ableism” inherent in triage decisions—implicitly disfavoring resources for patients with COVID-19 who are already physically or intellectually disabled, chronically ill, aged, homeless, psychosocially low functioning, etc.18 Without explicit protections for individuals who are chronically disabled, triage decisions unguided by policy safeguards may reflexively favor the more “abled.” This bias towards the more abled is often inherent in how difficult it is to access health care. It can also be manifested in bedside triage decisions made in the moment by individual clinicians. Many disability rights advocates have been sounding this alarm during the COVID-19 crisis.19

Continue to: A special circumstance of equity...

A special circumstance of equity is arising during this ongoing pandemic—the possibility of treating health care workers as a privileged class. Unlike typical disasters, where health care workers come in afterwards, and therefore are in relatively less danger, pandemics create particularly high risks of danger for such individuals, with repeated exposure to the virus. They are both responders and potential victims. Should they have higher priority for ventilators, vaccines, funding, etc?6 This is a more robust degree of compensatory justice than merely giving appreciation. Giving health care workers such advantages may seem intuitively appealing, but perhaps professionalism and the self-obligation of duty mitigates such claims.20

A unique opportunity

The magnitude and pervasiveness of this pandemic crisis is unique in our lifetimes, as both professionals and as citizens. In the crucible of this extraordinary time, these and other medical ethics dilemmas burn hotter than ever before. Different societies and institutions may come up with different answers, based on their cultures and values. It is important, however, that the venerable ethos of medical ethics, which has evolved through the millennia, codified in oaths, codes, and scholarship, can be a compass at the bedside and in the meetings of legislatures, leaders, and policymakers. Perhaps we can emerge from this time with more clarity about how to balance the preciousness of individual rights with the needs of the common good.

Bottom Line

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has brought increased attention to triage ethics and equity ethics. There is no coherent national or international agreement on how to best deploy limited supplies such as ventilators and personal protective equipment. Although the equitable distribution of health care delivery has long been a concern, this problem has become magnified by COVID-19. Clinicians may be asked to view health care through the less familiar lens of the common good, as opposed to focusing strictly on an individual patient.

Related Resources

- Johns Hopkins Berman Institute of Bioethics. Coronavirus ethics and policy insights and resources. https://bioethics.jhu.edu/research-and-outreach/covid-19-bioethics-expert-insights/.

- Daugherty-Biddison L, Gwon H, Regenberg A, et al. Maryland framework for the allocation of scarce lifesustaining medical resources in a catastrophic public health emergency. www.law.umaryland.edu/media/SOL/pdfs/Programs/Health-Law/MHECN/ASR%20Framework_Final.pdf.

1. AMA Journal of Ethics. COVID-19 ethics resource center. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/COVID-19-ethics-resource-center. Updated May 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

2. Skandakalis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, et al. “To afford the wounded speedy assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1392-1399.

3. Ross W. God panels and the history of hemodialysis in America: a cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(11):890-896.

4. Alexander L, Moore M. Deontological ethics. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/. Revised October 17, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2020.

5. Driver J. The history of utilitarianism. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/. Revised September 22, 2014. Accessed May 26, 2020.

6. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055.

7. Daugherty-Biddison EL, Faden R, Gwon HW, et al. Too many patients…a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019;155(4):848-854.

8. Dudzinski D, Campelia G, Brazg T. Pandemic resources including COVID-19 materials. Department of Bioethics and Humanities, University of Washington Medicine. http://depts.washington.edu/bhdept/ethics-medicine/bioethics-topics/detail/245. Published April 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

9. Antommaria AHM, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al; Task Force of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors [published online April 24, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020;M20-1738. doi: 10.7326/M20-1738.

10. Cooney E. Who gets hospitalized for COVID-19? Report shows differences by race and sex. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/09/hospitalized-COVID-19-patients-differences-by-race-and-sex/. Published April 9, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

11. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

12. American Psychiatric Association Ethics Committee. COVID-19 related opinions of the APA Ethics Committee. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Ethics/APA-COVID-19-Ethics-Opinions.pdf. Published May 5, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

13. Wee M. Coronavirus and the misuse of ‘do not resuscitate’ orders. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/coronavirus-and-the-misuse-of-do-not-resuscitate-orders. Published May 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

14. Prokopetz JZ, Lehmann LS. Redefining physicians’ role in assisted dying. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):97-99.

15. Yuill K, Boer T. What COVID-19 has revealed about euthanasia. spiked. https://www.spiked-online.com/2020/04/14/COVID-19-has-revealed-the-ugliness-of-euthanasia/. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

16. Plunkett AJ. COVID-19: hospitals should consider CoP carefully before deciding on DNR policy. PSQH. https://www.psqh.com/news/COVID-19-hospitals-should-consider-cop-carefully-before-deciding-on-dnr-policy/. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

17. Kramer DB, Lo B, Dickert NW. CPR in the COVID-19 era: an ethical framework [published online May 6, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2010758.

18. Mykitiuk R, Lemmens T. Assessing the value of a life: COVID-19 triage orders mustn’t work against those with disabilities. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-disabled-COVID-19-triage-orders-1.5532137. Published April 19, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

19. Solomon MZ, Wynia MK, Gostin LO. COVID-19 crisis triage—optimizing health outcomes and disability rights [published online May 19, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008300.

20. Appel JM. Ethics consult: who’s first to get COVID-19 Vax? MD/JD bangs gavel. MedPage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/COVID19/86260. Published May 1, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

1. AMA Journal of Ethics. COVID-19 ethics resource center. https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/COVID-19-ethics-resource-center. Updated May 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

2. Skandakalis PN, Lainas P, Zoras O, et al. “To afford the wounded speedy assistance”: Dominique Jean Larrey and Napoleon. World J Surg. 2006;30(8):1392-1399.

3. Ross W. God panels and the history of hemodialysis in America: a cautionary tale. Virtual Mentor. 2012;14(11):890-896.

4. Alexander L, Moore M. Deontological ethics. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/ethics-deontological/. Revised October 17, 2016. Accessed May 26, 2020.

5. Driver J. The history of utilitarianism. In: Zalta EN, ed. Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/utilitarianism-history/. Revised September 22, 2014. Accessed May 26, 2020.

6. Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(21):2049-2055.

7. Daugherty-Biddison EL, Faden R, Gwon HW, et al. Too many patients…a framework to guide statewide allocation of scarce mechanical ventilation during disasters. Chest. 2019;155(4):848-854.

8. Dudzinski D, Campelia G, Brazg T. Pandemic resources including COVID-19 materials. Department of Bioethics and Humanities, University of Washington Medicine. http://depts.washington.edu/bhdept/ethics-medicine/bioethics-topics/detail/245. Published April 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

9. Antommaria AHM, Gibb TS, McGuire AL, et al; Task Force of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors. Ventilator triage policies during the COVID-19 pandemic at U.S. hospitals associated with members of the Association of Bioethics Program Directors [published online April 24, 2020]. Ann Intern Med. 2020;M20-1738. doi: 10.7326/M20-1738.

10. Cooney E. Who gets hospitalized for COVID-19? Report shows differences by race and sex. STAT. https://www.statnews.com/2020/04/09/hospitalized-COVID-19-patients-differences-by-race-and-sex/. Published April 9, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

11. Gessen M. Why psychiatric wards are uniquely vulnerable to the coronavirus. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/why-psychiatric-wards-are-uniquely-vulnerable-to-the-coronavirus. Published April 21, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

12. American Psychiatric Association Ethics Committee. COVID-19 related opinions of the APA Ethics Committee. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Psychiatrists/Practice/Ethics/APA-COVID-19-Ethics-Opinions.pdf. Published May 5, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

13. Wee M. Coronavirus and the misuse of ‘do not resuscitate’ orders. The Spectator. https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/coronavirus-and-the-misuse-of-do-not-resuscitate-orders. Published May 6, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

14. Prokopetz JZ, Lehmann LS. Redefining physicians’ role in assisted dying. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(20):97-99.

15. Yuill K, Boer T. What COVID-19 has revealed about euthanasia. spiked. https://www.spiked-online.com/2020/04/14/COVID-19-has-revealed-the-ugliness-of-euthanasia/. Published April 14, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

16. Plunkett AJ. COVID-19: hospitals should consider CoP carefully before deciding on DNR policy. PSQH. https://www.psqh.com/news/COVID-19-hospitals-should-consider-cop-carefully-before-deciding-on-dnr-policy/. Published March 26, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

17. Kramer DB, Lo B, Dickert NW. CPR in the COVID-19 era: an ethical framework [published online May 6, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2010758.

18. Mykitiuk R, Lemmens T. Assessing the value of a life: COVID-19 triage orders mustn’t work against those with disabilities. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/news/opinion/opinion-disabled-COVID-19-triage-orders-1.5532137. Published April 19, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.

19. Solomon MZ, Wynia MK, Gostin LO. COVID-19 crisis triage—optimizing health outcomes and disability rights [published online May 19, 2020]. N Engl J Med. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008300.

20. Appel JM. Ethics consult: who’s first to get COVID-19 Vax? MD/JD bangs gavel. MedPage Today. https://www.medpagetoday.com/infectiousdisease/COVID19/86260. Published May 1, 2020. Accessed May 26, 2020.