User login

Naloxone Dispensing in Patients at Risk for Opioid Overdose After Total Knee Arthroplasty Within the Veterans Health Administration

Opioid overdose is a major public health challenge, with recent reports estimating 41 deaths per day in the United States from prescription opioid overdose.1,2 Prescribing naloxone has increasingly been advocated to reduce the risk of opioid overdose for patients identified as high risk. Naloxone distribution has been shown to decrease the incidence of opioid overdoses in the general population.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends considering naloxone prescription for patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, opioid dosages ≥ 50 morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and concurrent use of benzodiazepines.5

Although the CDC guidelines are intended for primary care clinicians in outpatient settings, naloxone prescribing is also relevant in the postsurgical setting.5 Many surgical patients are at risk for opioid overdose and data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has shown that risk of opioid overdose is 11-fold higher in the 30 days following discharge from a surgical admission, when compared with the subsequent calendar year.6,7 This likely occurs due to new prescriptions or escalated doses of opioids following surgery. Overdose risk may be particularly relevant to orthopedic surgery as postoperative opioids are commonly prescribed.8 Patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may represent a vulnerable population to overdose as it is one of the most commonly performed surgeries for the treatment of chronic pain, and is frequently performed in older adults with medical comorbidities.9,10

Identifying patients at high risk for opioid overdose is important for targeted naloxone dispensing.5 A risk index for overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (RIOSORD) tool has been developed and validated in veteran and other populations to identify such patients.11 The RIOSORD tool classifies patients by risk level (1-10) and predicts probability of overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (OSORD). A patient’s level of risk is based on a weighted combination of the 15 independent risk factors most highly associated with OSORD, including comorbid conditions, prescription drug use, and health care utilization.12 Using the RIOSORD tool, the VHA Opioid Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program is a risk mitigation initiative that aims to decrease opioid-related overdose morbidity and mortality. This is achieved via opioid overdose education for prevention, recognition, and response and includes outpatient naloxone prescription.13,14

Despite the comprehensive OEND program, there exists very little data to guide postsurgical naloxone prescribing. The prevalence of known risk factors for overdose in surgical patients remains unknown, as does the prevalence of perioperative naloxone distribution. Understanding overdose risk factors and naloxone prescribing patterns in surgical patients may identify potential targets for OEND efforts. This study retrospectively estimated RIOSORD scores for TKA patients between 2013 to 2016 and described naloxone distribution based on RIOSORD scores and risk factors.

Methods

We identified patients who had undergone primary TKA at VHA hospitals using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes, and data extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) of electronic health records (EHRs). Our study was granted approval with exemption from informed consent by the Durham Veteran Affairs Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

This retrospective cohort study included all veterans who underwent elective primary TKA from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2016. We excluded patients who died before discharge.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was being dispensed an outpatient naloxone prescription following TKA. Naloxone dispensing was identified by examining CDW outpatient pharmacy records with a final dispense date from 1 year before surgery through 7 days after discharge following TKA. To exclude naloxone administration that may have been given in a clinic, prescription data included only records with an outpatient prescription copay. Naloxone dispensing in the year before surgery was chosen to estimate likely preoperative possession of naloxone which could be available in the postoperative period. Naloxone dispensing until 7 days after discharge was chosen to identify any new dispensing that would be available in the postoperative period. These outcomes were examined over the study time frame on an annual basis.

Patient Factors

Demographic variables included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Independent risk factors for overdose from RIOSORD were identified for each patient.15 These risk factors included comorbidities (opioid use disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, or lung disease) and prescription drug use (use of opioids, benzodiazepines, long-acting opioids, ≥ 50 MEDD or ≥ 100 MEDD). ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to identify comorbidities. Risk classes on day of surgery were identified using a RIOSORD algorithm code. Consistent with the display of RIOSORD risk classes on the VHA Academic Detailing Service OEND risk report, patients were grouped into 3 groups based on their RIOSORD score: classes 1 to 4 (low risk), 5 to 7 (moderate risk), and 8 to 10 (high risk).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data on patient demographics, RIOSORD risk factors, overdose events, and naloxone dispensing over time.

Results

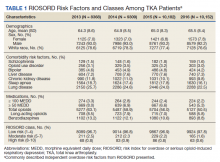

The study cohort included 38,011 veterans who underwent primary TKA in the VHA between January 1, 2013 and December 30, 2016. In this cohort, the mean age was 65 years, 93% were male, and 77% were White patients (Table 1). The most common comorbidities were lung disease in 9170 (24.1%) patients, sleep apnea in 6630 (17.4%) patients, chronic kidney disease in 4036 (10.6%) patients, liver disease in 2822 (7.4%) patients, and bipolar disorder in 1748 (4.6%) patients.

In 2013, 63.1% of patients presenting for surgery were actively prescribed opioids. By 2016, this decreased to 50.5%. Benzodiazepine use decreased from 13.2 to 8.8% and long-acting opioid use decreased from 8.5 to 5.8% over the same period. Patients taking ≥ 50 MEDD decreased from 8.0 to 5.3% and patients taking ≥ 100 MEDD decreased from 3.3 to 2.2%. The prevalence of moderate-risk patients decreased from 2.5 to 1.6% and high-risk patients decreased from 0.8 to 0.6% (Figure 1). Cumulatively, the prevalence of presenting with either moderate or high risk of overdose decreased from 3.3 to 2.2% between 2013 to 2016.

Naloxone Dispensing

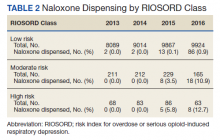

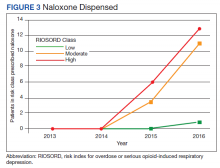

In 2013, naloxone was not dispensed to any patients at moderate or high risk for overdose between 365 days prior to surgery until 7 days after discharge (Table 2 and Figure 2). Low-risk group naloxone dispensing increased to 2 (0.0%) in 2014, to 13 (0.1%), in 2015, and to 86 (0.9%) in 2016. Moderate-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 8 (3.5%) in 2015, and to 18 (10.9%) in 2016. High-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 5 (5.8%) in 2015, and to 8 (12.7%) in 2016 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that patients presenting for TKA between 2013 and 2016 routinely had individual risk factors for overdose related to either prescription drug use or comorbidities. We also show that, although the number of patients at moderate and high risk for opioid overdose is decreasing, 2.2% of TKA patients remain at moderate or high risk for opioid overdose based on a weighted combination of these individual risk factors using RIOSORD. As demand for primary TKA is projected to grow to 3.5 million procedures by 2030, using prevalence from 2016, we estimate that 76,560 patients may present for TKA across the US with moderate or high risk for opioid overdose.9 Following discharge, this risk may be even higher as this estimate does not yet account for postoperative opioid use. We demonstrate that through a VHA OEND initiative, naloxone distribution increased and appeared to be targeted to those most at risk using a simple validated tool like RIOSORD.

Presence of an individual risk factor for overdose was present in as many as 63.1% of patients presenting for TKA, as was seen in 2013 with preoperative opioid use. The 3 highest scoring prescription use–related risk factors in RIOSORD are use of opioids ≥ 100 MEDD (16 points), ≥ 50 MEDD (9 points), and long-acting formulations (9 points). All 3 decreased in prevalence over the study period but by 2016 were still seen in 2.2% for ≥ 100 MEDD, 5.3% for ≥ 50 MEDD, and 5.8% for long-acting opioids. This decrease was not surprising given implementation of a VHA-wide opioid safety initiative and the OEND program, but this could also be related to changes in patient selection for surgery in the context of increased awareness of the opioid epidemic. Despite the trend toward safer opioid prescribing, by 2016 over half of patients (50.5%) who presented for TKA were already taking opioids, with 10.6% (543 of 5127) on doses ≥ 50 MEDD.

We observed a decrease in RIOSORD risk each year, consistent with decreasing prescription-related risk factors over time. This was most obvious in the moderate-risk group. It is unclear why a similar decrease was not as obvious in the high-risk group, but this in part may be due to the already low numbers of patients in the high-risk group. This may also represent the high-risk group being somewhat resistant to the initiatives that shifted moderate-risk patients to the low-risk group. There were proportionately more patients in the moderate- and high-risk groups in the original RIOSORD population than in our surgical population, which may be attributed to the fewer comorbidities seen in our surgical population, as well as the higher opioid-prescribing patterns seen prior to the VA OEND initiative.12

Naloxone prescribing was rare prior to the OEND initiative and increased from 2013 to 2016. Increases were most marked in those in moderate- and high-risk groups, although naloxone prescribing also increased among the low-risk group. Integration of RIOSORD stratification into the OEND initiative likely played a role in targeting increased access to naloxone among those at highest risk of overdose. Naloxone dispensing increased for every group, although a significant proportion of moderate- and high-risk patients, 89.1% and 87.3%, respectively, were still not dispensed naloxone by 2016. Moreover, our estimates of perioperative naloxone access were likely an overestimate by including patients dispensed naloxone up to 1 year before surgery until 7 days after surgery. The aim was to include patients who may not have been prescribed naloxone postoperatively because of an existing naloxone prescription at home. Perioperative naloxone access estimates would have been even lower if a narrower window had been used to approximate perioperative access. This identifies an important gap between those who may benefit from naloxone dispensing and those who received naloxone. This in part may be because OEND has not been implemented as routinely in surgical settings as other settings (eg, primary care). OEND efforts may more effectively increase naloxone prescribing among surgical patients if these efforts were targeted at surgical and anesthesia departments. Given that the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 requires an assessment of patient risk prior to opioid prescribing and VHA efforts to increase utilization of tools like the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM), which estimates patient risk when initiating an opioid prescription and includes naloxone as one of many risk mitigation strategies, we anticipate that rates of naloxone prescribing will increase over time.

Limitations

Our study captures a large number of patients across VHA hospitals of varying size nationwide, including a mix of those with and without academic medical center affiliations. This veteran population may not represent the US commercially insured population (CIP). Zedler and colleagues highlighted the differences in prevalence of individual risk factors: notably, the CIP had a substantially higher proportion of females and younger patients.11 VHA had a greater prevalence of common chronic conditions associated with older age. The frequency of opioid dependence was similar among CIP and VHA. However, substance abuse and nonopioid substance dependence diagnoses were 4-fold more frequent among VHA controls as CIP controls. Prescribing of all opioids, except morphine and methadone, was substantially greater in CIP than in VHA.11 Despite a difference in individual risk factors, a CIP-specific RIOSORD has been validated and can be used outside of the VHA to obviate the limitations of the VHA-specific RIOSORD.11

Other limitations include our estimation of naloxone access. We do not know whether naloxone was administered or have a reliable estimate of overdose incidence in this postoperative TKA population. Also, it is important to note that RIOSORD was not developed for surgical patients. The use of RIOSORD in a postoperative population likely underestimates risk of opioid overdose due to the frequent prescriptions of new opioids or escalation of existing MEDD to the postoperative patient. Our study was also retrospective in nature and reliant on accurate coding of patient risk factors. It is possible that comorbidities were not accurately identified by EHR and therefore subject to inconsistency.

Conclusions

Veterans presenting for TKA routinely have risk factors for opioid overdose. We observed a trend toward decreasing overdose risk which coincided with the Opioid Safety and OEND initiatives within the VHA. We also observed an increase in naloxone prescription for moderate- and high-risk patients undergoing TKA, although most of these patients still did not receive naloxone as of 2016. More research is needed to refine and validate the RIOSORD score for surgical populations. Expanding initiatives such as OEND to include surgical patients presents an opportunity to improve access to naloxone for postoperative patients that may help reduce opioid overdose in this population.

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. Published 2016 Dec 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

2. Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4

3. Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. Jan 30 2013;346:f174. doi:10.1136/bmj.f174

4. McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90-95. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1464

6. Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. Published 2018 Jan 17. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5790

7. Mudumbai SC, Lewis ET, Oliva EM, et al. Overdose risk associated with opioid use upon hospital discharge in Veterans Health Administration surgical patients. Pain Med. 2019;20(5):1020-1031. doi:10.1093/pm/pny150

8. Hsia HL, Takemoto S, van de Ven T, et al. Acute pain is associated with chronic opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(7):705-711. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000831

9. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222

10. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00285

11. Zedler BK, Saunders WB, Joyce AR, Vick CC, Murrelle EL. Validation of a screening risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in a US commercial health plan claims database. Pain Med. 2018;19(1):68-78. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx009

12. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-79. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

13. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

14. Oliva EM, Christopher MLD, Wells D, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: development of the Veterans Health Administration’s national program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S168-S179.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.022

15. Noël PH, Copeland LA, Perrin RA, et al. VHA Corporate Data Warehouse height and weight data: opportunities and challenges for health services research. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(8):739-750. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.08.0110

Opioid overdose is a major public health challenge, with recent reports estimating 41 deaths per day in the United States from prescription opioid overdose.1,2 Prescribing naloxone has increasingly been advocated to reduce the risk of opioid overdose for patients identified as high risk. Naloxone distribution has been shown to decrease the incidence of opioid overdoses in the general population.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends considering naloxone prescription for patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, opioid dosages ≥ 50 morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and concurrent use of benzodiazepines.5

Although the CDC guidelines are intended for primary care clinicians in outpatient settings, naloxone prescribing is also relevant in the postsurgical setting.5 Many surgical patients are at risk for opioid overdose and data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has shown that risk of opioid overdose is 11-fold higher in the 30 days following discharge from a surgical admission, when compared with the subsequent calendar year.6,7 This likely occurs due to new prescriptions or escalated doses of opioids following surgery. Overdose risk may be particularly relevant to orthopedic surgery as postoperative opioids are commonly prescribed.8 Patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may represent a vulnerable population to overdose as it is one of the most commonly performed surgeries for the treatment of chronic pain, and is frequently performed in older adults with medical comorbidities.9,10

Identifying patients at high risk for opioid overdose is important for targeted naloxone dispensing.5 A risk index for overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (RIOSORD) tool has been developed and validated in veteran and other populations to identify such patients.11 The RIOSORD tool classifies patients by risk level (1-10) and predicts probability of overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (OSORD). A patient’s level of risk is based on a weighted combination of the 15 independent risk factors most highly associated with OSORD, including comorbid conditions, prescription drug use, and health care utilization.12 Using the RIOSORD tool, the VHA Opioid Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program is a risk mitigation initiative that aims to decrease opioid-related overdose morbidity and mortality. This is achieved via opioid overdose education for prevention, recognition, and response and includes outpatient naloxone prescription.13,14

Despite the comprehensive OEND program, there exists very little data to guide postsurgical naloxone prescribing. The prevalence of known risk factors for overdose in surgical patients remains unknown, as does the prevalence of perioperative naloxone distribution. Understanding overdose risk factors and naloxone prescribing patterns in surgical patients may identify potential targets for OEND efforts. This study retrospectively estimated RIOSORD scores for TKA patients between 2013 to 2016 and described naloxone distribution based on RIOSORD scores and risk factors.

Methods

We identified patients who had undergone primary TKA at VHA hospitals using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes, and data extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) of electronic health records (EHRs). Our study was granted approval with exemption from informed consent by the Durham Veteran Affairs Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

This retrospective cohort study included all veterans who underwent elective primary TKA from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2016. We excluded patients who died before discharge.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was being dispensed an outpatient naloxone prescription following TKA. Naloxone dispensing was identified by examining CDW outpatient pharmacy records with a final dispense date from 1 year before surgery through 7 days after discharge following TKA. To exclude naloxone administration that may have been given in a clinic, prescription data included only records with an outpatient prescription copay. Naloxone dispensing in the year before surgery was chosen to estimate likely preoperative possession of naloxone which could be available in the postoperative period. Naloxone dispensing until 7 days after discharge was chosen to identify any new dispensing that would be available in the postoperative period. These outcomes were examined over the study time frame on an annual basis.

Patient Factors

Demographic variables included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Independent risk factors for overdose from RIOSORD were identified for each patient.15 These risk factors included comorbidities (opioid use disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, or lung disease) and prescription drug use (use of opioids, benzodiazepines, long-acting opioids, ≥ 50 MEDD or ≥ 100 MEDD). ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to identify comorbidities. Risk classes on day of surgery were identified using a RIOSORD algorithm code. Consistent with the display of RIOSORD risk classes on the VHA Academic Detailing Service OEND risk report, patients were grouped into 3 groups based on their RIOSORD score: classes 1 to 4 (low risk), 5 to 7 (moderate risk), and 8 to 10 (high risk).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data on patient demographics, RIOSORD risk factors, overdose events, and naloxone dispensing over time.

Results

The study cohort included 38,011 veterans who underwent primary TKA in the VHA between January 1, 2013 and December 30, 2016. In this cohort, the mean age was 65 years, 93% were male, and 77% were White patients (Table 1). The most common comorbidities were lung disease in 9170 (24.1%) patients, sleep apnea in 6630 (17.4%) patients, chronic kidney disease in 4036 (10.6%) patients, liver disease in 2822 (7.4%) patients, and bipolar disorder in 1748 (4.6%) patients.

In 2013, 63.1% of patients presenting for surgery were actively prescribed opioids. By 2016, this decreased to 50.5%. Benzodiazepine use decreased from 13.2 to 8.8% and long-acting opioid use decreased from 8.5 to 5.8% over the same period. Patients taking ≥ 50 MEDD decreased from 8.0 to 5.3% and patients taking ≥ 100 MEDD decreased from 3.3 to 2.2%. The prevalence of moderate-risk patients decreased from 2.5 to 1.6% and high-risk patients decreased from 0.8 to 0.6% (Figure 1). Cumulatively, the prevalence of presenting with either moderate or high risk of overdose decreased from 3.3 to 2.2% between 2013 to 2016.

Naloxone Dispensing

In 2013, naloxone was not dispensed to any patients at moderate or high risk for overdose between 365 days prior to surgery until 7 days after discharge (Table 2 and Figure 2). Low-risk group naloxone dispensing increased to 2 (0.0%) in 2014, to 13 (0.1%), in 2015, and to 86 (0.9%) in 2016. Moderate-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 8 (3.5%) in 2015, and to 18 (10.9%) in 2016. High-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 5 (5.8%) in 2015, and to 8 (12.7%) in 2016 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that patients presenting for TKA between 2013 and 2016 routinely had individual risk factors for overdose related to either prescription drug use or comorbidities. We also show that, although the number of patients at moderate and high risk for opioid overdose is decreasing, 2.2% of TKA patients remain at moderate or high risk for opioid overdose based on a weighted combination of these individual risk factors using RIOSORD. As demand for primary TKA is projected to grow to 3.5 million procedures by 2030, using prevalence from 2016, we estimate that 76,560 patients may present for TKA across the US with moderate or high risk for opioid overdose.9 Following discharge, this risk may be even higher as this estimate does not yet account for postoperative opioid use. We demonstrate that through a VHA OEND initiative, naloxone distribution increased and appeared to be targeted to those most at risk using a simple validated tool like RIOSORD.

Presence of an individual risk factor for overdose was present in as many as 63.1% of patients presenting for TKA, as was seen in 2013 with preoperative opioid use. The 3 highest scoring prescription use–related risk factors in RIOSORD are use of opioids ≥ 100 MEDD (16 points), ≥ 50 MEDD (9 points), and long-acting formulations (9 points). All 3 decreased in prevalence over the study period but by 2016 were still seen in 2.2% for ≥ 100 MEDD, 5.3% for ≥ 50 MEDD, and 5.8% for long-acting opioids. This decrease was not surprising given implementation of a VHA-wide opioid safety initiative and the OEND program, but this could also be related to changes in patient selection for surgery in the context of increased awareness of the opioid epidemic. Despite the trend toward safer opioid prescribing, by 2016 over half of patients (50.5%) who presented for TKA were already taking opioids, with 10.6% (543 of 5127) on doses ≥ 50 MEDD.

We observed a decrease in RIOSORD risk each year, consistent with decreasing prescription-related risk factors over time. This was most obvious in the moderate-risk group. It is unclear why a similar decrease was not as obvious in the high-risk group, but this in part may be due to the already low numbers of patients in the high-risk group. This may also represent the high-risk group being somewhat resistant to the initiatives that shifted moderate-risk patients to the low-risk group. There were proportionately more patients in the moderate- and high-risk groups in the original RIOSORD population than in our surgical population, which may be attributed to the fewer comorbidities seen in our surgical population, as well as the higher opioid-prescribing patterns seen prior to the VA OEND initiative.12

Naloxone prescribing was rare prior to the OEND initiative and increased from 2013 to 2016. Increases were most marked in those in moderate- and high-risk groups, although naloxone prescribing also increased among the low-risk group. Integration of RIOSORD stratification into the OEND initiative likely played a role in targeting increased access to naloxone among those at highest risk of overdose. Naloxone dispensing increased for every group, although a significant proportion of moderate- and high-risk patients, 89.1% and 87.3%, respectively, were still not dispensed naloxone by 2016. Moreover, our estimates of perioperative naloxone access were likely an overestimate by including patients dispensed naloxone up to 1 year before surgery until 7 days after surgery. The aim was to include patients who may not have been prescribed naloxone postoperatively because of an existing naloxone prescription at home. Perioperative naloxone access estimates would have been even lower if a narrower window had been used to approximate perioperative access. This identifies an important gap between those who may benefit from naloxone dispensing and those who received naloxone. This in part may be because OEND has not been implemented as routinely in surgical settings as other settings (eg, primary care). OEND efforts may more effectively increase naloxone prescribing among surgical patients if these efforts were targeted at surgical and anesthesia departments. Given that the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 requires an assessment of patient risk prior to opioid prescribing and VHA efforts to increase utilization of tools like the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM), which estimates patient risk when initiating an opioid prescription and includes naloxone as one of many risk mitigation strategies, we anticipate that rates of naloxone prescribing will increase over time.

Limitations

Our study captures a large number of patients across VHA hospitals of varying size nationwide, including a mix of those with and without academic medical center affiliations. This veteran population may not represent the US commercially insured population (CIP). Zedler and colleagues highlighted the differences in prevalence of individual risk factors: notably, the CIP had a substantially higher proportion of females and younger patients.11 VHA had a greater prevalence of common chronic conditions associated with older age. The frequency of opioid dependence was similar among CIP and VHA. However, substance abuse and nonopioid substance dependence diagnoses were 4-fold more frequent among VHA controls as CIP controls. Prescribing of all opioids, except morphine and methadone, was substantially greater in CIP than in VHA.11 Despite a difference in individual risk factors, a CIP-specific RIOSORD has been validated and can be used outside of the VHA to obviate the limitations of the VHA-specific RIOSORD.11

Other limitations include our estimation of naloxone access. We do not know whether naloxone was administered or have a reliable estimate of overdose incidence in this postoperative TKA population. Also, it is important to note that RIOSORD was not developed for surgical patients. The use of RIOSORD in a postoperative population likely underestimates risk of opioid overdose due to the frequent prescriptions of new opioids or escalation of existing MEDD to the postoperative patient. Our study was also retrospective in nature and reliant on accurate coding of patient risk factors. It is possible that comorbidities were not accurately identified by EHR and therefore subject to inconsistency.

Conclusions

Veterans presenting for TKA routinely have risk factors for opioid overdose. We observed a trend toward decreasing overdose risk which coincided with the Opioid Safety and OEND initiatives within the VHA. We also observed an increase in naloxone prescription for moderate- and high-risk patients undergoing TKA, although most of these patients still did not receive naloxone as of 2016. More research is needed to refine and validate the RIOSORD score for surgical populations. Expanding initiatives such as OEND to include surgical patients presents an opportunity to improve access to naloxone for postoperative patients that may help reduce opioid overdose in this population.

Opioid overdose is a major public health challenge, with recent reports estimating 41 deaths per day in the United States from prescription opioid overdose.1,2 Prescribing naloxone has increasingly been advocated to reduce the risk of opioid overdose for patients identified as high risk. Naloxone distribution has been shown to decrease the incidence of opioid overdoses in the general population.3,4 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain recommends considering naloxone prescription for patients with a history of overdose or substance use disorder, opioid dosages ≥ 50 morphine equivalent daily dose (MEDD), and concurrent use of benzodiazepines.5

Although the CDC guidelines are intended for primary care clinicians in outpatient settings, naloxone prescribing is also relevant in the postsurgical setting.5 Many surgical patients are at risk for opioid overdose and data from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) has shown that risk of opioid overdose is 11-fold higher in the 30 days following discharge from a surgical admission, when compared with the subsequent calendar year.6,7 This likely occurs due to new prescriptions or escalated doses of opioids following surgery. Overdose risk may be particularly relevant to orthopedic surgery as postoperative opioids are commonly prescribed.8 Patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty (TKA) may represent a vulnerable population to overdose as it is one of the most commonly performed surgeries for the treatment of chronic pain, and is frequently performed in older adults with medical comorbidities.9,10

Identifying patients at high risk for opioid overdose is important for targeted naloxone dispensing.5 A risk index for overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (RIOSORD) tool has been developed and validated in veteran and other populations to identify such patients.11 The RIOSORD tool classifies patients by risk level (1-10) and predicts probability of overdose or serious opioid-induced respiratory depression (OSORD). A patient’s level of risk is based on a weighted combination of the 15 independent risk factors most highly associated with OSORD, including comorbid conditions, prescription drug use, and health care utilization.12 Using the RIOSORD tool, the VHA Opioid Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program is a risk mitigation initiative that aims to decrease opioid-related overdose morbidity and mortality. This is achieved via opioid overdose education for prevention, recognition, and response and includes outpatient naloxone prescription.13,14

Despite the comprehensive OEND program, there exists very little data to guide postsurgical naloxone prescribing. The prevalence of known risk factors for overdose in surgical patients remains unknown, as does the prevalence of perioperative naloxone distribution. Understanding overdose risk factors and naloxone prescribing patterns in surgical patients may identify potential targets for OEND efforts. This study retrospectively estimated RIOSORD scores for TKA patients between 2013 to 2016 and described naloxone distribution based on RIOSORD scores and risk factors.

Methods

We identified patients who had undergone primary TKA at VHA hospitals using Current Procedural Terminology (CPT), International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) procedure codes, and data extracted from the VHA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) of electronic health records (EHRs). Our study was granted approval with exemption from informed consent by the Durham Veteran Affairs Healthcare System Institutional Review Board.

This retrospective cohort study included all veterans who underwent elective primary TKA from January 1, 2013 through December 31, 2016. We excluded patients who died before discharge.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was being dispensed an outpatient naloxone prescription following TKA. Naloxone dispensing was identified by examining CDW outpatient pharmacy records with a final dispense date from 1 year before surgery through 7 days after discharge following TKA. To exclude naloxone administration that may have been given in a clinic, prescription data included only records with an outpatient prescription copay. Naloxone dispensing in the year before surgery was chosen to estimate likely preoperative possession of naloxone which could be available in the postoperative period. Naloxone dispensing until 7 days after discharge was chosen to identify any new dispensing that would be available in the postoperative period. These outcomes were examined over the study time frame on an annual basis.

Patient Factors

Demographic variables included age, sex, and race/ethnicity. Independent risk factors for overdose from RIOSORD were identified for each patient.15 These risk factors included comorbidities (opioid use disorder, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, liver disease, chronic kidney disease, sleep apnea, or lung disease) and prescription drug use (use of opioids, benzodiazepines, long-acting opioids, ≥ 50 MEDD or ≥ 100 MEDD). ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnosis codes were used to identify comorbidities. Risk classes on day of surgery were identified using a RIOSORD algorithm code. Consistent with the display of RIOSORD risk classes on the VHA Academic Detailing Service OEND risk report, patients were grouped into 3 groups based on their RIOSORD score: classes 1 to 4 (low risk), 5 to 7 (moderate risk), and 8 to 10 (high risk).

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize data on patient demographics, RIOSORD risk factors, overdose events, and naloxone dispensing over time.

Results

The study cohort included 38,011 veterans who underwent primary TKA in the VHA between January 1, 2013 and December 30, 2016. In this cohort, the mean age was 65 years, 93% were male, and 77% were White patients (Table 1). The most common comorbidities were lung disease in 9170 (24.1%) patients, sleep apnea in 6630 (17.4%) patients, chronic kidney disease in 4036 (10.6%) patients, liver disease in 2822 (7.4%) patients, and bipolar disorder in 1748 (4.6%) patients.

In 2013, 63.1% of patients presenting for surgery were actively prescribed opioids. By 2016, this decreased to 50.5%. Benzodiazepine use decreased from 13.2 to 8.8% and long-acting opioid use decreased from 8.5 to 5.8% over the same period. Patients taking ≥ 50 MEDD decreased from 8.0 to 5.3% and patients taking ≥ 100 MEDD decreased from 3.3 to 2.2%. The prevalence of moderate-risk patients decreased from 2.5 to 1.6% and high-risk patients decreased from 0.8 to 0.6% (Figure 1). Cumulatively, the prevalence of presenting with either moderate or high risk of overdose decreased from 3.3 to 2.2% between 2013 to 2016.

Naloxone Dispensing

In 2013, naloxone was not dispensed to any patients at moderate or high risk for overdose between 365 days prior to surgery until 7 days after discharge (Table 2 and Figure 2). Low-risk group naloxone dispensing increased to 2 (0.0%) in 2014, to 13 (0.1%), in 2015, and to 86 (0.9%) in 2016. Moderate-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 8 (3.5%) in 2015, and to 18 (10.9%) in 2016. High-risk group naloxone dispensing remained at 0 (0.0%) in 2014, but increased to 5 (5.8%) in 2015, and to 8 (12.7%) in 2016 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Our data demonstrate that patients presenting for TKA between 2013 and 2016 routinely had individual risk factors for overdose related to either prescription drug use or comorbidities. We also show that, although the number of patients at moderate and high risk for opioid overdose is decreasing, 2.2% of TKA patients remain at moderate or high risk for opioid overdose based on a weighted combination of these individual risk factors using RIOSORD. As demand for primary TKA is projected to grow to 3.5 million procedures by 2030, using prevalence from 2016, we estimate that 76,560 patients may present for TKA across the US with moderate or high risk for opioid overdose.9 Following discharge, this risk may be even higher as this estimate does not yet account for postoperative opioid use. We demonstrate that through a VHA OEND initiative, naloxone distribution increased and appeared to be targeted to those most at risk using a simple validated tool like RIOSORD.

Presence of an individual risk factor for overdose was present in as many as 63.1% of patients presenting for TKA, as was seen in 2013 with preoperative opioid use. The 3 highest scoring prescription use–related risk factors in RIOSORD are use of opioids ≥ 100 MEDD (16 points), ≥ 50 MEDD (9 points), and long-acting formulations (9 points). All 3 decreased in prevalence over the study period but by 2016 were still seen in 2.2% for ≥ 100 MEDD, 5.3% for ≥ 50 MEDD, and 5.8% for long-acting opioids. This decrease was not surprising given implementation of a VHA-wide opioid safety initiative and the OEND program, but this could also be related to changes in patient selection for surgery in the context of increased awareness of the opioid epidemic. Despite the trend toward safer opioid prescribing, by 2016 over half of patients (50.5%) who presented for TKA were already taking opioids, with 10.6% (543 of 5127) on doses ≥ 50 MEDD.

We observed a decrease in RIOSORD risk each year, consistent with decreasing prescription-related risk factors over time. This was most obvious in the moderate-risk group. It is unclear why a similar decrease was not as obvious in the high-risk group, but this in part may be due to the already low numbers of patients in the high-risk group. This may also represent the high-risk group being somewhat resistant to the initiatives that shifted moderate-risk patients to the low-risk group. There were proportionately more patients in the moderate- and high-risk groups in the original RIOSORD population than in our surgical population, which may be attributed to the fewer comorbidities seen in our surgical population, as well as the higher opioid-prescribing patterns seen prior to the VA OEND initiative.12

Naloxone prescribing was rare prior to the OEND initiative and increased from 2013 to 2016. Increases were most marked in those in moderate- and high-risk groups, although naloxone prescribing also increased among the low-risk group. Integration of RIOSORD stratification into the OEND initiative likely played a role in targeting increased access to naloxone among those at highest risk of overdose. Naloxone dispensing increased for every group, although a significant proportion of moderate- and high-risk patients, 89.1% and 87.3%, respectively, were still not dispensed naloxone by 2016. Moreover, our estimates of perioperative naloxone access were likely an overestimate by including patients dispensed naloxone up to 1 year before surgery until 7 days after surgery. The aim was to include patients who may not have been prescribed naloxone postoperatively because of an existing naloxone prescription at home. Perioperative naloxone access estimates would have been even lower if a narrower window had been used to approximate perioperative access. This identifies an important gap between those who may benefit from naloxone dispensing and those who received naloxone. This in part may be because OEND has not been implemented as routinely in surgical settings as other settings (eg, primary care). OEND efforts may more effectively increase naloxone prescribing among surgical patients if these efforts were targeted at surgical and anesthesia departments. Given that the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act of 2016 requires an assessment of patient risk prior to opioid prescribing and VHA efforts to increase utilization of tools like the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM), which estimates patient risk when initiating an opioid prescription and includes naloxone as one of many risk mitigation strategies, we anticipate that rates of naloxone prescribing will increase over time.

Limitations

Our study captures a large number of patients across VHA hospitals of varying size nationwide, including a mix of those with and without academic medical center affiliations. This veteran population may not represent the US commercially insured population (CIP). Zedler and colleagues highlighted the differences in prevalence of individual risk factors: notably, the CIP had a substantially higher proportion of females and younger patients.11 VHA had a greater prevalence of common chronic conditions associated with older age. The frequency of opioid dependence was similar among CIP and VHA. However, substance abuse and nonopioid substance dependence diagnoses were 4-fold more frequent among VHA controls as CIP controls. Prescribing of all opioids, except morphine and methadone, was substantially greater in CIP than in VHA.11 Despite a difference in individual risk factors, a CIP-specific RIOSORD has been validated and can be used outside of the VHA to obviate the limitations of the VHA-specific RIOSORD.11

Other limitations include our estimation of naloxone access. We do not know whether naloxone was administered or have a reliable estimate of overdose incidence in this postoperative TKA population. Also, it is important to note that RIOSORD was not developed for surgical patients. The use of RIOSORD in a postoperative population likely underestimates risk of opioid overdose due to the frequent prescriptions of new opioids or escalation of existing MEDD to the postoperative patient. Our study was also retrospective in nature and reliant on accurate coding of patient risk factors. It is possible that comorbidities were not accurately identified by EHR and therefore subject to inconsistency.

Conclusions

Veterans presenting for TKA routinely have risk factors for opioid overdose. We observed a trend toward decreasing overdose risk which coincided with the Opioid Safety and OEND initiatives within the VHA. We also observed an increase in naloxone prescription for moderate- and high-risk patients undergoing TKA, although most of these patients still did not receive naloxone as of 2016. More research is needed to refine and validate the RIOSORD score for surgical populations. Expanding initiatives such as OEND to include surgical patients presents an opportunity to improve access to naloxone for postoperative patients that may help reduce opioid overdose in this population.

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. Published 2016 Dec 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

2. Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4

3. Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. Jan 30 2013;346:f174. doi:10.1136/bmj.f174

4. McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90-95. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1464

6. Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. Published 2018 Jan 17. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5790

7. Mudumbai SC, Lewis ET, Oliva EM, et al. Overdose risk associated with opioid use upon hospital discharge in Veterans Health Administration surgical patients. Pain Med. 2019;20(5):1020-1031. doi:10.1093/pm/pny150

8. Hsia HL, Takemoto S, van de Ven T, et al. Acute pain is associated with chronic opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(7):705-711. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000831

9. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222

10. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00285

11. Zedler BK, Saunders WB, Joyce AR, Vick CC, Murrelle EL. Validation of a screening risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in a US commercial health plan claims database. Pain Med. 2018;19(1):68-78. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx009

12. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-79. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

13. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

14. Oliva EM, Christopher MLD, Wells D, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: development of the Veterans Health Administration’s national program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S168-S179.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.022

15. Noël PH, Copeland LA, Perrin RA, et al. VHA Corporate Data Warehouse height and weight data: opportunities and challenges for health services research. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(8):739-750. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.08.0110

1. Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2010-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(50-51):1445-1452. Published 2016 Dec 30. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm655051e1

2. Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290-297. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4

3. Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, et al. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. Jan 30 2013;346:f174. doi:10.1136/bmj.f174

4. McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90-95. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.03.014

5. Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain--United States, 2016. JAMA. 2016;315(15):1624-1645. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1464

6. Brat GA, Agniel D, Beam A, et al. Postsurgical prescriptions for opioid naive patients and association with overdose and misuse: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2018;360:j5790. Published 2018 Jan 17. doi:10.1136/bmj.j5790

7. Mudumbai SC, Lewis ET, Oliva EM, et al. Overdose risk associated with opioid use upon hospital discharge in Veterans Health Administration surgical patients. Pain Med. 2019;20(5):1020-1031. doi:10.1093/pm/pny150

8. Hsia HL, Takemoto S, van de Ven T, et al. Acute pain is associated with chronic opioid use after total knee arthroplasty. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2018;43(7):705-711. doi:10.1097/AAP.0000000000000831

9. Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, Mowat F, Halpern M. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):780-785. doi:10.2106/JBJS.F.00222

10. Kurtz SM, Ong KL, Lau E, Bozic KJ. Impact of the economic downturn on total joint replacement demand in the United States: updated projections to 2021. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(8):624-630. doi:10.2106/JBJS.M.00285

11. Zedler BK, Saunders WB, Joyce AR, Vick CC, Murrelle EL. Validation of a screening risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in a US commercial health plan claims database. Pain Med. 2018;19(1):68-78. doi:10.1093/pm/pnx009

12. Zedler B, Xie L, Wang L, et al. Development of a risk index for serious prescription opioid-induced respiratory depression or overdose in Veterans Health Administration patients. Pain Med. 2015;16(8):1566-79. doi:10.1111/pme.12777

13. Oliva EM, Bowe T, Tavakoli S, et al. Development and applications of the Veterans Health Administration’s Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Mitigation (STORM) to improve opioid safety and prevent overdose and suicide. Psychol Serv. 2017;14(1):34-49. doi:10.1037/ser0000099

14. Oliva EM, Christopher MLD, Wells D, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: development of the Veterans Health Administration’s national program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S168-S179.e4. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2017.01.022

15. Noël PH, Copeland LA, Perrin RA, et al. VHA Corporate Data Warehouse height and weight data: opportunities and challenges for health services research. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2010;47(8):739-750. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2009.08.0110

Creating an Intensive Care Unit From a Postanesthesia Care Unit for the COVID-19 Surge at the Veterans Affairs Ann Arbor Healthcare System

The rise in prevalence of the community spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the US in early March 2020 led to hospital systems across the country preparing for an increase in critically ill patients.1 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) anticipated an increased census of veterans who would need hospital admission for severe COVID-19 as well as the potential need to receive patients from community hospitals in Southeast Michigan, the location of one of the worst outbreaks in the US at that time.2

Through the facility’s incident command center, a hospital operations group identified the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) as a space to convert to an intensive care unit (ICU) for patients with COVID-19 needing mechanical ventilation. Other hospitals throughout the world have created similar makeshift ICUs to help care for the surge of patients with COVID-19, recognizing the high level of monitoring and resources available in the perioperative setting.3-5 These ICUs have been successfully created in operating rooms,3 recovery rooms,5 and procedural settings.4

Between March 27, 2020 and April 25, 2020, a great multidisciplinary effort enabled the VAAAHS PACU-ICU to care for critically ill veterans with COVID-19 from Southeast Michigan as well as civilian transfers from overwhelmed neighboring community hospitals. This article will discuss planning considerations, including facility preparation, equipment, and staffing models. The unique challenges faced in managing an open-plan surge-capacity ICU also will be discussed as well as the solutions that were enacted.

Methods

Hospital Preparation

Maintaining a 2-zone model in which patients with COVID-19 and without COVID-19 could be cared for separately was of major importance. The VAAAHS traditional ICU was converted into a 16-bed COVID-19 ICU and staffed by the Pulmonary Critical Care Service. A separate wing of the hospital was converted into a 19-bed non-COVID-19 ICU, which also was staffed by the Pulmonary Critical Care Service that increased its staffing of residents, fellows, and attending physicians to meet the increasing clinical demands. Elective major surgery cases were postponed, and surgeons managed the care of postoperative surgical ICU patients. This arrangement allowed the existing 4 anesthesiologist intensivists to staff the PACU COVID-19 ICU.

Considerations, including space requirements, staffing, equipment, infection control requirements, and ability for facilities to engineer a negative pressure space were factored into the decision to convert the PACU to an additional 12-bed ICU. This effectively tripled the VAAAHS ICU capacity, enabling patient transfers from the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan, which was being impacted by a surge of cases in Detroit. In addition, this allowed for the opening of the hospital for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ICU transfers from hospitals in Southeast Michigan in order to fulfill the fourth VA mission to provide care and support to state and local communities for emergency management, public health, and safety.

PACU Preparation

PACU was selected as an overflow ICU due to its open floor plan, allowing patients on ventilators to be seen from a central nursing station. This would allow for the safe use of ventilators without central alarm capabilities (especially anesthesia machines). Given the risk of a circuit disconnect, all ventilators without central alarm capabilities needed to be seen and heard within the space to ensure patient safety.

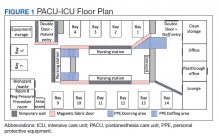

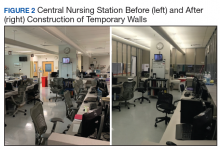

Facilities Management was able to construct temporary barriers with vinyl covered sheetrock and plexiglass to partition the central nursing workstation from the patient area in a U-shape (Figure 1). The patient area was turned into a negative pressure space where strict airborne precautions could be observed. Although the air handling unit serving this space is equipped with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, it was mechanically manipulated to ensure that all air coming from the space was discharged through exhaust and not recirculated into another occupied space within the hospital. Total air exchange rates were measured and calculated for both the positive and negative spaces to ensure they met or exceeded at least 6 air changes per hour, as recommended by Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidance.6,7 A differential pressure indicator was installed to provide staff with the ability to monitor the pressure relationship between the 2 spaces in real time.

Twelve patient care beds were created. A traditionally engineered airborne infection isolation room in PACU served as a procedure room for aerosol-generating procedures, especially intubation, extubation, use of high-flow nasal cannula, and tracheostomy placement. Strict airborne precautions were taken within the patient area. The area inside the nursing station was positively pressurized to allow for surgical masks only to be required for the comfort of health care workers (Figure 2). A clear donning and doffing workflow was created for movement between the nursing area and the patient care area.

Personal Protective Equipment

Personal protective equipment (PPE) was of paramount importance in this open care unit. Airborne precautions were used in the entire patient care area. Powered air-purifying respirators (PAPRs) were used when possible to conserve the supply of N95 masks. Each health care worker was issued a reusable PAPR hood, which was cleaned by the user after each use by wiping the exterior of the entire hood with virucidal wipes. The brand and active ingredient of the virucidal wipes varied by availability of supplies, but the “virus kill time” was clearly labeled on each container. Each health care worker had a paper bag for storing his or her PAPR hood between usage to allow drying and ventilation. PAPR units were charged in between uses and shared by all clinical staff. Two layers of nonsterile gloves were worn.

Because of the open care area, attention had to be given to adhere to infection control policies if health care workers wanted to care for multiple patients while in the area. A new gown was placed over the existing gown, and the outer layer of gloves was removed. The under layer of gloves was then sanitized with hand sanitizer, and a new pair of outer gloves was then worn.

Equipment

Much of the ICU-level equipment needed was already present within the operating room (OR) area. Existing patient monitors were used and connected to a central monitoring station present in the nurses station. Relevant contents of the ICU storage room were duplicated and placed on shelves in the patient care area. Out-of-use anesthesia carts were used for a dedicated COVID-19 invasive line cart. A designated ultrasound with cardiac and vascular access probes was assigned to the PACU-ICU. Anesthesia machines were brought into the PACU-ICU and prepared with viral filters in line to prevent contamination of the machines, in keeping with national guidance from the American Society of Anesthesiologists and Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation.8

Multidisciplinary Staffing Model

With the reduced surgical and procedural case load due to halting nonemergent operations, the Anesthesiology and Perioperative Care Service was able to staff the PACU-ICU with critical care anesthesiologists, nurse anesthetists, residents, and PACU and procedural nurses without hindering access to emergent surgeries. A separate preoperative area was maintained with an 8-bed capacity for both preoperative and postoperative management of non-COVID-19 surgical patients.

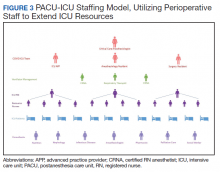

The staffing model was designed using guidance on the expansion of ICU staffing with non-ICU resources from the Society of Critical Care Medicine as well as local guidance on appropriate nursing ratios (Figure 3).9 Given the high acuity and dynamic nature of COVID-19 coupled with the unique considerations that exist using anesthesia machines as long-term ICU ventilators, 24-hour inhospital attending intensivist coverage was provided in the ICU by 4 critical care anesthesiologists who rotated between 12-hour day and night shifts. The critical care anesthesiologists led a team of anesthesiology and surgery residents and ICU advanced practice providers dedicated solely to the PACU-ICU. Non-ICU anesthesiologists helped with procedures such as intubation and invasive line placement and provided coverage of the ICU patients during sign-out and rounding. Certified registered nurse anesthetists (CRNAs) performed intubations and helped offload respiratory therapists (one of the resources most in shortage) by managing and weaning ventilators and were instrumental in prone positioning of patients. Dedicated ICU nurses were deployed every shift to oversee the unit and act as a resource to the PACU nurses. Fortunately, many PACU nurses had prior ICU training and experience, and nurses from outpatient areas also were recruited to help with patient care. Together, they provided direct patient care. OR nurses assisted with delivering supplies, medications and transporting specimens to the laboratory, as no formal hospital tube station was present in the PACU.

Because of the open-unit setting, nurses practiced bundled care and staggered their turns in the patient care area. For example, a nurse who entered to administer medication to patient A, could then receive communication to check the urine output for patient B and do so without completely doffing and redonning. This allowed preservation of PPE and reduced time in PPE for the health care providers (HCPs).

A scheduled daily meeting included staff from PACU-ICU; Medical ICU (MICU), which also treated patients with COVID-19; and the Palliative Care Service (Figure 4). Patients with single-organ failure were preferentially sent to PACU-ICU, as the ability to do renal replacement therapy (RRT) in an open unit proved difficult. The palliative care team and VAAAHS social workers assisted both MICU and PACU-ICU with communicating with patients’ families, which provided a great help during a clinically demanding time. Physical therapists increased their staffing of the ICU to specifically help with mobilization of patients with COVID-19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome, given the prolonged mechanical ventilation courses that were seen. Other consulting services frequently involved included infectious disease and nephrology.

Challenges and Solutions

Communication between staff located within the patient area and staff located in the nursing station was difficult given the loud noise generated by a PAPR and the plexiglass walls that separated the areas. Multiple techniques were attempted to overcome this. Dry erase boards were placed within the space to facilitate requests, but these were found to be time consuming. Two-way radios worked well if the users were wearing N95s but were harder to communicate when users were wearing PAPRs. Baby monitors were purchased to facilitate 2-way communication and were useful at times although quieter than desired. Vocera B3000N Communication Badges, which were already utilized in the perioperative period at the facility, could be utilized underneath PPE and were ultimately the best form of clear communication between staff within the patient care area and outside the negative pressure zone. In accordance with company guidance, these mobile devices were cleaned with virucidal wipes after use.10

Communication with patients’ families was critically important. The ICU team, palliative care team, or social workers made daily telephone calls to family members. The facility telehealth coordinator provided a designated tablet device to enable the intensivists to video conference with the patients’ families at bedside, utilizing virtual care manager appointments. This allowed families to see and interact with their loved ones despite the prohibition of family visitors. Every effort was made to utilize video calling daily; however, clinical demands as well as Internet and technological constraints from individual family members intermittently precluded video calls.

Clinical Challenges

Patients with severe COVID-19 infections requiring mechanical ventilation have proven to be exceptionally high-acuity patients with myriad organ-based complications reported.11 Specific to our PACU-ICU, we determined that it was impractical to arrange for continuous RRT given the amount of training PACU nursing staff would have required and the limited ICU nursing staff in the PACU-ICU. Intermittent hemodialysis required replumbing for water supply and drainage but was ultimately not required as our facility expanded the number of continuous RRT machines available, allowing all patients in the COVID-19 ICU who required RRT to stay in the 16-bed ICU. Daily communication with the MICU allowed for safe transfer of patients with imminent needs for RRT to the MICU, providing a coordinated strategy for the deployment of scarce resources across our expanded ICU footprint.

Using anesthesia machines as ICU ventilators proved challenging, despite following best practice guidance.8 Notably, anesthesia machines are not actively humidified and require very high fresh gas flows, necessitating the addition of heat moisture exchangers (HME) to the circuit. Also, viral filters were placed in the circuit to prevent machine contamination. The addition of the HME and viral filters to each circuit increased the present dead space and led todifficulty in providing adequate ventilation to patients who already may have had a high proportion of physiologic dead space. The high fresh gas flows used still seemed inadequate in preventing moisture buildup in the machine parts, necessitating frequent exchanges of viral filters, HMEs, and circuits to prevent high peak airway pressures. In addition, anesthesia machines directly sample gas from the patient's breathing circuit, creating the risk for contamination of the space. This required a reconfiguration to allow for a suction scavenging system by VAAAHS biomedical engineers. Also, anesthesia machines are not designed for long-term ventilation and have different ventilation modes compared with modern ICU ventilators. Although they were used for several patients when the PACU-ICU opened, the hospital was able to acquire additional ICU ventilators, and extensive or prolonged use of anesthesia machine ventilators was avoided.

Infection Control

The open care setting provided unique infection control issues that had to be addressed.12 The open setting allowed preservation of PPE and the ability for bundled care to be delivered easily. The VAAAHS infection control team worked closely with the ICU team to develop practices to ensure both patient and health care worker protection. Notable challenges included donning new gowns between patients when a PAPR was already being worn, leading to draping of new gowns over existing gowns when going between patients. True hand hygiene was also difficult, as health care workers did not want to completely remove gloves while in the patient care area. Layering of 2 pairs of gloves allowed the outer gloves to be removed after care of each patient, at which time alcohol gel was applied to the inner gloves, a new gown was placed over the existing gown, and a new pair of gloves was layered on top.

Although patients were intubated for long periods in the PACU-ICU, there was concern for increased risk of exposure of health care workers after extubation given the inability to contain the coughing patients within a private room. If a patient did well, they were transferred to a private room on the general medical floors within 24 hours of extubation to minimize this risk.

Privacy

The open care design meant less privacy for patients than would be provided in a private room. Curtains were drawn around patient beds as much as possible, especially for nursing care, but priority was given to visualization of the ventilator when a HCP was not present to ensure safety at all times. The majority of patients cared for in the PACU-ICU were intubated and sedated on arrival, but thankfully many were extubated. After extubation privacy in the open care area became more of an issue and may have led to more nighttime disturbances and substandard delirium prevention measures. Priority was given to expediting the transfer of these patients to private rooms on the general medical floor once their respiratory status was deemed stable.

Conclusions

The COVID-19 pandemic is truly an unprecedented event in our nation’s history, which has led to the first nationwide authorization of the fourth mission of VA to provide support for national, state, and local public health. The PACU-ICU was designed, engineered, built, and staffed by perioperative HCPs through an exceptional multidisciplinary effort in a matter of days. Through this dedication of health care workers and staff, the VAAAHS was able to care for critically ill veterans from Southeast Michigan and serve the community during a time of overwhelming demand on the national health care system.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the outstanding team of administrators, engineers, physical therapists, pharmacists, nurses, advanced practice providers, CRNAs, respiratory therapists, and physicians who made it possible to respond to our veterans’ and our community’s needs in a time of unprecedented demand on our health care system. A special thank you to Eric Deters, Chief Strategy Officer; Brittany McClure, ICU Nurse Manager; and Mark Dotson, Chief Supply Chain Officer. It was a privilege to serve on this mission together.

1. Murray CJL; IHME COVID-19 Health Service Utilization Forecasting Team. Forecasting COVID-19 impact on hospital bed-days, ICU-days, ventilator days and deaths by US state in the next 4 months. https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.27.20043752v1.full.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2020.

2. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine. Coronavirus resource center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/data/state-timeline/new-confirmed-cases/michigan. Updated July 17, 2020. Accessed July 17, 2020.

3. Mojoli F, Mongodi S, Grugnetti G, et al. Setup of a dedicated coronavirus intensive care unit: logistical aspects. Anesthesiology. 2020;133(1):244-246. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003325

4. Peters AW, Chawla KS, Turnbull ZA. Transforming ORs into ICUs. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(19):e52. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2010853

5. Lund E, Whitten A, Middleton R, Phlippeau N, Flynn DN. Converting peri-anesthesia care units into COVID-19 critical care units: one community hospital’s response. Anesthesiology News. April 30, 2020. https://www.anesthesiologynews.com/Online-First/Article/04-20/Converting-Peri-Anesthesia-Care-Units-Into-COVID-19-Critical-Care-Units/58167. Accessed July 14, 2020.

6. American Institute of Architects. Guidelines for Design and Construction of Hospitals and Healthcare Facilities. Washington, DC: American Institute of Architects Press; 2001.

7. Garner JS. The CDC Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1993;21(3):160-162. doi:10.1016/0196-6553(93)90009-s

8. American Society of Anesthesiologists. APSF/ASA Guidance on Purposing Anesthesia Machines as ICU Ventilators. https://www.asahq.org/in-the-spotlight/coronavirus-covid-19-information/purposing-anesthesia-machines-for-ventilators. Updated May 7, 2020. Accessed July 14, 2020.

9. Halpern NA, Tan KS. United States Resource Availability for COVID-19. https://sccm.org/getattachment/Blog/March-2020/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19.pdf. Updated May 12, 2020. Accessed July 14, 2020.

10. Vocera. Vocera devices and accessories cleaning guide. http://pubs.vocera.com/device/vseries/production/docs/vseries_device_cleaning_guide.pdf. Updated June 24, 2020. Accessed July 14, 2020.

11. Poston JT, Patel BK, Davis AM. Management of Critically Ill Adults With COVID-19 [published online ahead of print, 2020 Mar 26]. JAMA. 2020;10.1001/jama.2020.4914. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.4914

12. O’Connell NH, Humphreys H. Intensive care unit design and environmental factors in the acquisition of infection. J Hosp Infect. 2000;45(4):255-262. doi:10.1053/jhin.2000.0768

The rise in prevalence of the community spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the US in early March 2020 led to hospital systems across the country preparing for an increase in critically ill patients.1 The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Ann Arbor Healthcare System (VAAAHS) anticipated an increased census of veterans who would need hospital admission for severe COVID-19 as well as the potential need to receive patients from community hospitals in Southeast Michigan, the location of one of the worst outbreaks in the US at that time.2

Through the facility’s incident command center, a hospital operations group identified the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) as a space to convert to an intensive care unit (ICU) for patients with COVID-19 needing mechanical ventilation. Other hospitals throughout the world have created similar makeshift ICUs to help care for the surge of patients with COVID-19, recognizing the high level of monitoring and resources available in the perioperative setting.3-5 These ICUs have been successfully created in operating rooms,3 recovery rooms,5 and procedural settings.4

Between March 27, 2020 and April 25, 2020, a great multidisciplinary effort enabled the VAAAHS PACU-ICU to care for critically ill veterans with COVID-19 from Southeast Michigan as well as civilian transfers from overwhelmed neighboring community hospitals. This article will discuss planning considerations, including facility preparation, equipment, and staffing models. The unique challenges faced in managing an open-plan surge-capacity ICU also will be discussed as well as the solutions that were enacted.

Methods

Hospital Preparation

Maintaining a 2-zone model in which patients with COVID-19 and without COVID-19 could be cared for separately was of major importance. The VAAAHS traditional ICU was converted into a 16-bed COVID-19 ICU and staffed by the Pulmonary Critical Care Service. A separate wing of the hospital was converted into a 19-bed non-COVID-19 ICU, which also was staffed by the Pulmonary Critical Care Service that increased its staffing of residents, fellows, and attending physicians to meet the increasing clinical demands. Elective major surgery cases were postponed, and surgeons managed the care of postoperative surgical ICU patients. This arrangement allowed the existing 4 anesthesiologist intensivists to staff the PACU COVID-19 ICU.

Considerations, including space requirements, staffing, equipment, infection control requirements, and ability for facilities to engineer a negative pressure space were factored into the decision to convert the PACU to an additional 12-bed ICU. This effectively tripled the VAAAHS ICU capacity, enabling patient transfers from the John D. Dingell VA Medical Center in Detroit, Michigan, which was being impacted by a surge of cases in Detroit. In addition, this allowed for the opening of the hospital for both COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 ICU transfers from hospitals in Southeast Michigan in order to fulfill the fourth VA mission to provide care and support to state and local communities for emergency management, public health, and safety.

PACU Preparation

PACU was selected as an overflow ICU due to its open floor plan, allowing patients on ventilators to be seen from a central nursing station. This would allow for the safe use of ventilators without central alarm capabilities (especially anesthesia machines). Given the risk of a circuit disconnect, all ventilators without central alarm capabilities needed to be seen and heard within the space to ensure patient safety.

Facilities Management was able to construct temporary barriers with vinyl covered sheetrock and plexiglass to partition the central nursing workstation from the patient area in a U-shape (Figure 1). The patient area was turned into a negative pressure space where strict airborne precautions could be observed. Although the air handling unit serving this space is equipped with high efficiency particulate air (HEPA) filters, it was mechanically manipulated to ensure that all air coming from the space was discharged through exhaust and not recirculated into another occupied space within the hospital. Total air exchange rates were measured and calculated for both the positive and negative spaces to ensure they met or exceeded at least 6 air changes per hour, as recommended by Occupational Safety and Health Administration guidance.6,7 A differential pressure indicator was installed to provide staff with the ability to monitor the pressure relationship between the 2 spaces in real time.

Twelve patient care beds were created. A traditionally engineered airborne infection isolation room in PACU served as a procedure room for aerosol-generating procedures, especially intubation, extubation, use of high-flow nasal cannula, and tracheostomy placement. Strict airborne precautions were taken within the patient area. The area inside the nursing station was positively pressurized to allow for surgical masks only to be required for the comfort of health care workers (Figure 2). A clear donning and doffing workflow was created for movement between the nursing area and the patient care area.

Personal Protective Equipment