User login

Multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program Targeting Chronic Pain and Addiction Management in Veterans

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

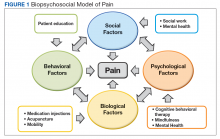

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

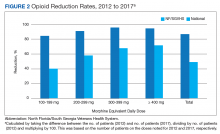

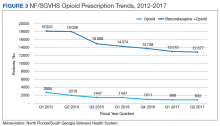

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

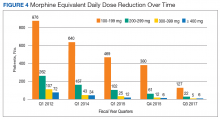

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.