User login

Multispecialty Opioid Risk Reduction Program Targeting Chronic Pain and Addiction Management in Veterans

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

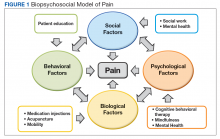

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

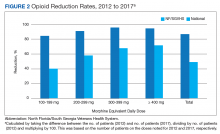

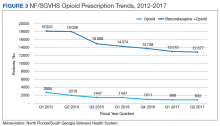

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

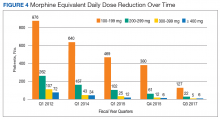

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

Chronic pain significantly affects 100 million Americans.1,2 Pain accounts for $560 to $635 billion in annual financial costs to society, including health care costs and loss of productivity (ie, days missed from work, hours of work lost, and lower wages).2,3 Although pain prevalence exceeds other chronic diseases, such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, and heart disease, it lacks a sufficient body of evidence-based research and guidelines on the underlying mechanisms, valid methods of assessment, and comparative effectiveness of treatments to effectively implement into clinical practice.2,4 Prevention and treatment of pain are often delayed, inaccessible, or inadequate.2 Primary care providers (PCPs) are most often sought for pain management and treat about 52% of chronic pain patients.2,3,5 Veterans are especially vulnerable to chronic pain and are at risk for inadequate treatment.2

Background

There is an epidemic of drug abuse and mortality from opioid prescription medication.6 In the US, rates of overdose deaths from prescription opioids were 6.1 per 100,000 for men and 4.2 per 100,000 for women in 2017. Opioids were involved in 47,600 overdose deaths in 2017, accounting for 67.8% of all drug overdose deaths.7

A large number of patients on long-term opioids have preexisting substance use disorders and/or psychiatric disease, further complicating chronic pain management.8-10 Prescription opioid use has been the precursor for about 80% of people who are now heroin addicts.11 Iatrogenic addiction from prescription medications isn’t easily captured by standard addiction criteria. Consequently, in patients who are on opioid therapy for prolonged periods, separating complex opioid dependence from addiction is difficult.12 Improved addiction screening and risk mitigation strategies are needed along with aggressive treatment monitoring to curb the opioid epidemic.

Opioid Management in Primary Care

The majority of opioid medications are prescribed by PCPs, which is magnified in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system due to the high prevalence of service-related injuries.3,13 The VA is at the forefront of addressing the complexities of opioid addiction through several initiatives.14 The ability to offer the frequent visits needed to safely manage patients prescribed opioids and the integration of mental health and addiction treatment are often lacking in non-VA primary care clinics. Therefore, a key to solving the opioid crisis is developing these capabilities so they can be delivered within the primary care setting. There is substantial evidence in support of nonopioid alternatives to chronic pain management, including other pharmacologic approaches, exercise, physical therapy, acupuncture, weight loss, smoking cessation, chiropractic care, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and other integrative health modalities.

A 2009 VA directive mandated the development of a comprehensive, integrated, systemwide approach to pain management.15 The VA Stepped-Care Biopsychosocial Model for Pain Management is dependent on timely access to secondary consultation from pain medicine, behavioral health, physical medicine, and other specialty consultation.15

History of VHA SCAN-ECHO Model

The Specialty Care Access Network–Extension for Community Health Outcomes (SCAN-ECHO) is a Veterans Health Administration (VHA) adaptation of a program that originated at the University of Mexico.16,17 The SCAN-ECHO model uses a multisite videoconferencing network to provide specialty care consultations to PCPs and patient aligned care teams (PACTs). During the 60- to 90-minute weekly sessions, case presentations are analyzed in real time so that over time, the PCPs gain knowledge, competency, and confidence in learning how to handle complex chronic conditions.

Since its implementation, the SCAN-ECHO program has been adopted across the VHA in a variety of specialties. One program, the SCAN-ECHO for Pain Management (SCAN-ECHO-PM) was implemented in 7 VHA networks in 31 states, spanning 47 medical centers and 148 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs).18 The SCAN-ECHO-PM program successfully conducted 257 multidisciplinary pain consultations between 2011 and 2013, resulting in increased initiation of nonopioid medications.18

The aim of this article is to describe the implementation of a multicomponent primary care-based pain clinic with a fully integrated mental health service and addiction service at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NF/SGVHS). A practiced-based intervention of the biopsychosocial model with robust patient engagement has guided the development of the NF/SGVHS pain clinic (Figure 1).4,19

Pain CLinic

NF/SGVHS comprises the Malcom Randall and Lake City VA medical centers (VAMCs) hospitals, 3 satellite outpatient clinics, and 8 CBOCs. Spanning 33 counties in North Florida and 19 counties in South Georgia, the NF/SGVHS serves more than 140,000 patients. In 2010, the Malcom Randall VAMC established a multidisciplinary primary care pain clinic to manage veterans at high-risk for noncancer chronic pain and addiction. The noncancer pain policy was revised after garnering support from stakeholders who treat chronic pain, including the chiefs of psychiatry, rehabilitation medicine, neurosurgery, psychology, interventional pain, pharmacy, nursing, addiction medicine, and primary care. The clinic is staffed by primary care physicians trained in internal medicine and family medicine and is structured with 1-hour first visits, and 30-minute follow-up visits to allow enough time for comprehensive evaluation while meeting the needs for close follow-up support.

All physicians in the clinic have buprenorphine prescribing credentials to aid in the management of opioid addiction, as some patients feel more comfortable receiving addiction treatment in a primary care setting. The multimodal care model consists of several services that include addiction psychiatrists, interventional pain specialists, pain psychologists, and pain pharmacologists who coordinate the care to the veterans. The addiction psychiatrists offer a full range of services with inpatient residential and outpatient programs. Through recurring meetings with primary care pain clinic staff, the addiction psychiatrists are available to discuss use of buprenorphine and arrange follow-up for patients with complex pain addiction. There is ongoing collaboration to develop the best care plan that meets the patient’s needs for chronic pain, addiction, and/or mental health issues. The interventional pain service has 3 fellowship-trained pain care providers who deliver comprehensive evaluation, pharmacologic recommendations, and a full range of interventional and complementary therapies with an emphasis on objective functional improvement. Pain care providers offer alternatives to patients who are being weaned from opioids and support the multidisciplinary patient engagement model.

The pain psychology program, established in 2011, delivers CBT to 5 onsite locations and 5 telehealth locations. The service includes an advanced CBT program and a couples CBT program. The pharmacy pain fellowship program provides staff for an outpatient e-consult pain management service and an inpatient pharmacy consult service. Harnessing pain specialty pharmacists, the pharmacy service addresses pharmacokinetic issues, urine drug screen (UDS) results, opioid tapering and discharge planning for pain, addiction and mental health needs. The NF/SGVHS Primary Care Pain Clinic was established to support PCPs who did not feel comfortable managing chronic pain patients. These patients were typically on high-dose opioid therapy (> 100-mg morphine equivalent daily doses [MEDDs]); patients with a history of opioid addiction; patients with an addiction to opioids combined with benzodiazepines; and patients with comorbid medical issues (eg, sleep apnea), which complicated their management. The process of addressing opioid safety in these complex pain patients can be labor intensive and generally cannot be accomplished in a brief visit in a primary care setting where many other medical problems often need to be addressed.

Most patients on high-dose opioids are fearful of any changes in their medications. The difficult conversation regarding opioid safety is a lengthy one and frequently will occur over multiple visits. In addition, safely tapering opioids requires frequent follow-up to provide psychological support and to address withdrawal and mental health issues that may arise. As opioids are tapered, the clinic reinforces improved pain care through a multimodal biopsychosocial model. All veterans receiving pain care outside the VA are monitored annually to assure they are receiving evidence-based pain care as defined by the biopsychosocial model.

Education

Since 2011, the NF/SGVHS SCAN-ECHO pain and addiction educational forum has created > 50 hours of approved annual continuing medical education (CME) on pain management and addiction for PCPs. Initially, the 1-hour weekly educational audioconferences presented a pain management case along with related topics and involved specialists from interventional pain, physical therapy, psychiatry, nursing, neurology, and psychology departments. In 2013, in conjunction with the VA SCAN-ECHO program of Hunter Holmes McGuire VAMC in Richmond, Virginia, and Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, the audioconference was expanded to 2 days each week with additional topics on addiction management. Residency and fellowship rotations were developed that specifically targeted fellows from psychiatry, pharmacology, and interventional pain departments.

Currently, an 8-session pain school is delivered onsite and at 7 telehealth locations. The school is a collaborative effort involving interventional pain, psychology, pharmacy, nutrition, and the primary care pain clinic staff. As the cornerstone of the program, the pain school stresses the biopsychosocial patient engagement model.

Program Evaluation

The VA is equipped with multiple telehealth service networks that allow for the delivery of programs, such as the pain school, a pain psychology program, and a yoga program, onsite or offsite. The VA Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) manages electronic health records, allowing for rapid chart review and e-consults. The NF/SGVHS Pain Management Program provides about 1500 e-consults yearly. The CPRS includes templates with pain metrics to help PCPs deliver pain care more efficiently and evaluate performance measures. This system also allows for the capture of data to track improvements in the care of the veterans served.

From 2012 to 2017, more than 5000 NF/SGVHS patients were weaned from opioids. Overall, there was an 87% reduction in patients receiving opioids ( ≥ 100-mg MEDDs) within the NF/SGVHS, which is significantly more than the 49% seen nationally across the VHA (Figure 2). Percent reduction was calculated by taking the difference in number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and 2017, dividing by the number of patients receiving opioids in 2012 and multiplying by 100. The largest proportion of opioid dose reductions for NF/SGVHS and VHA patients, respectively, were seen in 300-mg to 399-mg MEDDs (95% vs 67%, respectively); followed by ≥ 400-mg MEDDs (94% vs 71%, respectively); 200-mg to 299-mg MEDDs (91% vs 58%, respectively); and 100-mg to 199-mg MEDDs (84% vs 40%, respectively). When examining NF/SGVHS trends over time, there has been a consistent decline in patients prescribed opioids (18 223 in 2012 compared with 12 877 in 2017) with similar trends in benzodiazepine-opioid combination therapy (2694 in 2012 compared with 833 in 2017) (Figure 3).

Similar declines are seen when patients are stratified by the MEDD (Figure 4). From 2012 to 2017, 92% of the patients were successfully tapered off doses ≥ 400-mg MEDD (2012, n = 72; 2017, n = 6), and tapered off 300-mg to 399-mg MEDD (2012, n = 107; 2017, n = 5); 95% were tapered off 200-mg to 299-mg MEDD (2012, n = 262; 2017, n = 22); and 86% were tapered off 100-mg to 199-mg MEDD (2012, n = 876; 2017; n = 127).

Conclusion

Successful integration of primary care with mental health and addiction services is paramount to aggressively taper patients with chronic pain from opioids. There is evidence that drug dependence and chronic pain should be treated like other chronic illness.20 Both chronic pain and addiction can be treated with a multidimensional self-management approach. In view of the high incidence of mental health and addiction associated with opioid use, it makes sense that an integrated, 1-stop pain and addiction clinic that understands and addresses both issues is more likely to improve patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported by the resources and facilities at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System, Geriatric Research Education Clinical Center in Gainesville, Florida.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

1. Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457-467.

2. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 2011.

3. Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738-747.

4. Gatchel RJ, McGeary DD, McGeary CA, Lippe B. Interdisciplinary chronic pain management: past, present, and future. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):119-130.

5. Meghani SH, Polomano RC, Tait RC, Vallerand AH, Anderson KO, Gallagher RM. Advancing a national agenda to eliminate disparities in pain care: directions for health policy, education, practice, and research. Pain Med. 2012;13(1):5-28.

6. McHugh RK, Nielsen S, Weiss RD. Prescription drug abuse: from epidemiology to public policy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2015;48(1):1-7.

7. Scholl L, Seth P, Kariisa M, Wilson N, Baldwin G. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths-United States, 2013-2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(5152):1419-1427.

8. Edlund MJ, Martin BC, Devries A, Fan MY, Braden JB, Sullivan MD. Trends in use of opioids for chronic noncancer pain among individuals with mental health and substance use disorders: the TROUP study. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):1-8.

9. Højsted J, Sjøgren P. Addiction to opioids in chronic pain patients: a literature review. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(5):490-518.

10. Seal KH, Shi Y, Cohen G, et al. Association of mental health disorders with prescription opioids and high-risk opioid use in US veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. JAMA. 2012;307(9):940-947.

11. Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36:559-574.

12. Ballantyne JC, Sullivan MD, Kolodny A. Opioid dependence vs addiction: a distinction without a difference? Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(17):1342-1343.

13. Levy B, Paulozzi L, Mack KA, Jones CM. Trends in opioid analgesic-prescribing rates by specialty, U.S., 2007-2012. Am J Prev Med. 2015;49(3):409-413.

14. Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611-612.

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Veteran Health Administration Directive 2009-053, Pain Management. https://www.va.gov/painmanagement/docs/vha09paindirective.pdf. Published October 28, 2009. Accessed August 19, 2019.

16. Arora S, Geppert CM, Kalishman S, et al. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82(2):154-160.

17. Kirsh S, Su GL, Sales A, Jain R. Access to outpatient specialty care: solutions from an integrated health care system. Am J Med Qual. 2015;30(1):88-90.

18. Frank JW, Carey EP, Fagan KM, et al. Evaluation of a telementoring intervention for pain management in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2015;16(6):1090-1100.

19. Fillingim RB. Individual differences in pain: understanding the mosaic that makes pain personal. Pain. 2017;158 (suppl 1):S11-S18.

20. McLellan AT, Lewis DC, O’Brien CP, Kleber HD. Drug dependence, a chronic medical illness: implications for treatment, insurance, and outcomes evaluation. JAMA. 2000;284(13):1689-1695.

Worsening agitation and hallucinations: Could it be PTSD?

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

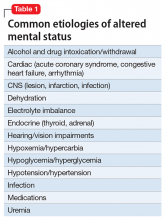

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

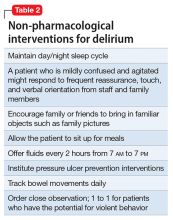

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

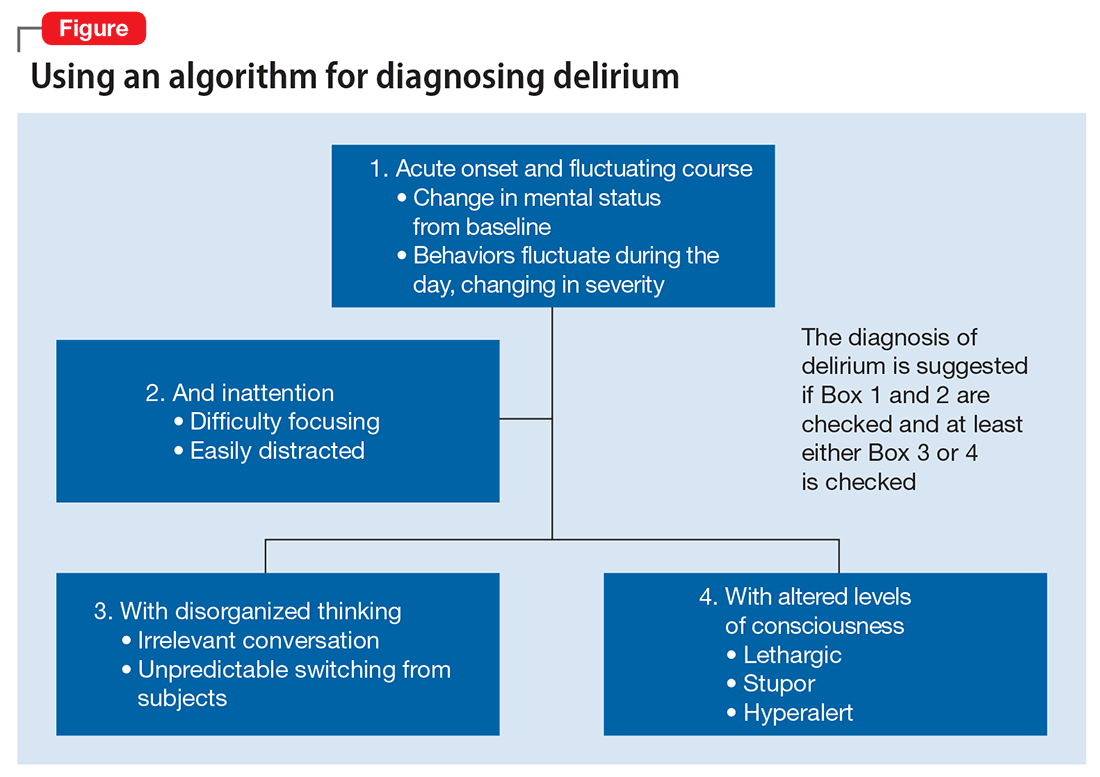

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.