User login

Worsening agitation and hallucinations: Could it be PTSD?

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

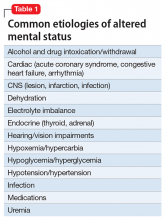

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

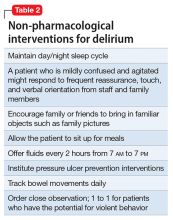

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

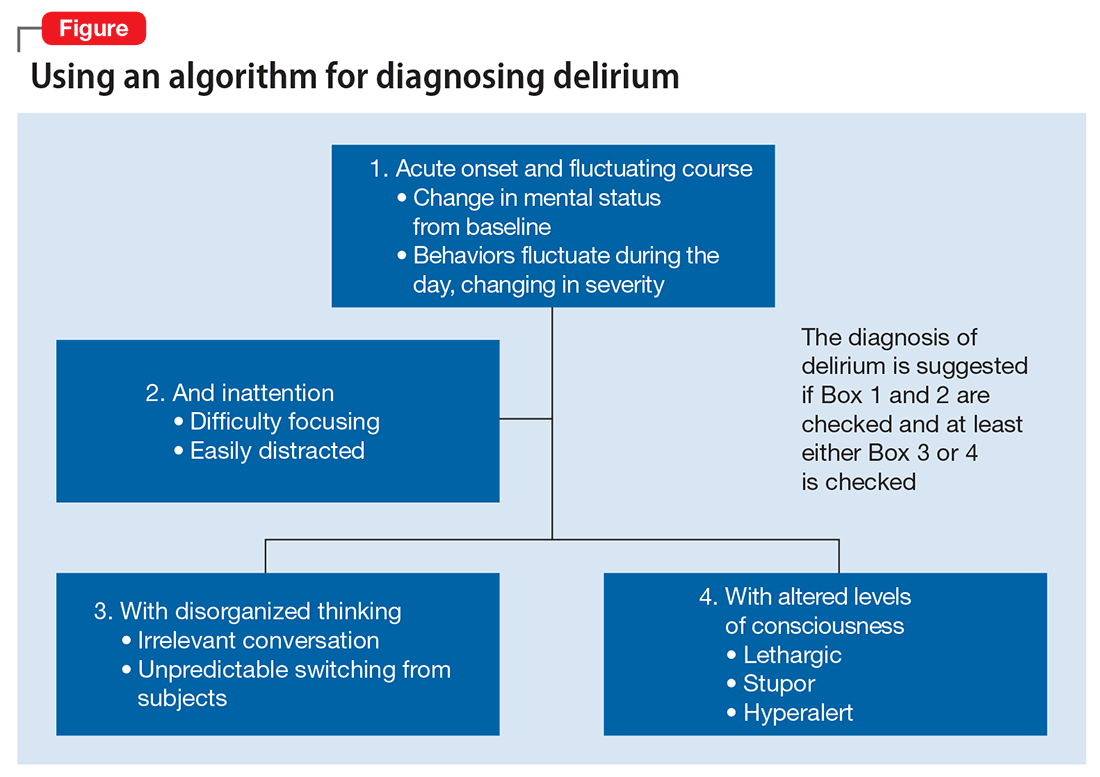

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.