User login

A Severe Case of Paliperidone Palmitate-Induced Parkinsonism Leading to Prolonged Hospitalization: Opportunities for Improvement

Many patients with psychiatric illness have difficulty with medication adherence. Patients with impaired reality testing especially are at risk.

Keck and McElroy evaluated 141 patients who were initially hospitalized for bipolar disorder prospectively over 1 year to assess adherence with medication. During the follow-up period, 71 patients (51%) were partially or totally nonadherent with medication as prescribed. The most commonly cited reason for nonadherence was denial of need.1

Clinicians and patients face additional challenges due to the deleterious effects of relapse in the setting of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Almost all oral antipsychotic or mood stabilizer medications require a minimum dosing schedule to effectively treat these disorders, and some of these oral medications require regular laboratory monitoring. Moreover, some of the agents can have serious adverse effects (AEs), such as seizure or withdrawal, if stopped abruptly. Social support from family or friends may improve adherence, but many psychiatric outpatients have a smaller social support network than do patients without psychiatric illnesses.2

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have been available for the past 40 years. These medications have provided clinicians with an additional option for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who are nonadherent to their medication treatment plans or who desire an administration choice that is more convenient than daily oral pills.3-7 Some clinical practice guidelines recommend considering LAIs as a maintenance treatment for schizophrenia.5 Like the rest of the pharmacopoeia, these formulations have AEs, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and metabolic syndrome.1 The longer half-life of these drugs may make such effects difficult to reverse.

This article presents a case of the use of depot formulation paliperidone palmitate in an elderly patient with bipolar disorder who was previously on high-dose oral second generation antipsychotics. He developed severe parkinsonism during a protracted hospitalization that ended in death.

Case Presentation

Mr. W was a 68-year-old homeless white male with a history of coronary artery disease status-post coronary artery bypass surgery, obstructive sleep apnea, and bipolar 1 disorder who presented to a large rural VAMC emergency department (ED) as a transfer from an outside hospital (OSH). He originally presented at the OSH for vomiting and diarrhea, but while there, he was placed under involuntary psychiatric commitment. The involuntary commitment form noted him to be tangential and disorganized; he was found walking about the ED without clothes. During the initial psychiatry interview, the clinician noted a disorganized thought process. When asked about circumstances leading to admission, he stated he was “a scuba diver, pilot, actor, submarine commander.” He also reported he had given “seminars to 6,000 people,” he held a psychology degree, and he came from a family that owned part of the island of Kodiak, Alaska. Mr. W stated he had no mental health history and believed psychiatry was witchcraft. He reported having no hallucinations and stated he heard the voice of god. He also reported to have met god multiple times and to have been married to a supermodel.

Mr. W’s chart demonstrated a history of mental illness over 30 years and that he previously was prescribed psychiatric medications. He had multiple inpatient psychiatric admissions with grandiose ideations, disorganized behaviors, and hypersexuality. He had been prescribed quetiapine, divalproex, lithium, carbamazepine, and lorazepam. He was formally diagnosed in the past with bipolar 1 disorder. There also was a family history of psychiatric illness. His mother had received electroconvulsive therapy, and both parents had alcohol substance use disorder.

Mr. W had been homeless for 20 years and had several psychiatric admissions during this period. Mr. W also had chronic difficulty with obtaining food and taking medications as prescribed. Sometimes he would only be able to eat 1 to 2 meals per day. He often changed location and had lived in at least 7 different states. Currently, he was estranged from his family. About 19 years ago, his sister reported that the veteran had told her that he was Jesus Christ, per clinical records. His estranged sister’s statement was corroborated by past psychology consult records citing episodes of the patient hearing god 30 and 26 years before the current admission. His second ex-wife cited inappropriate sexual behavior in front of their children. He had difficulty in school, failed at least 2 grades, and joined the U.S. Navy in tenth grade. A Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination given 19 years ago showed mild impairment on attention and severe impairment in memory.

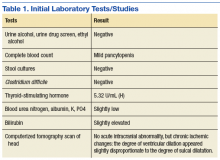

The physical examination on presentation to the OSH was unremarkable. Mr. W did not cooperate with formal neurocognitive testing, and he consistently made errors during orientation testing. Complete blood count from a OSH ED laboratory test was remarkable for a mild pancytopenia with a leukocyte count of 3,100 cells/mcL, hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 38.4%. Red cell distribution width was within normal limits at 13.5%. Stool cultures showed normal fecal flora and no salmonella, shigella, or campylobacter. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was slightly elevated at 5.32 U/mL. An electrocardiogram showed a QTc interval of 412 ms. A computerized tomography scan of his head showed no acute intracranial abnormality along with chronic ischemic changes in the brain (Table 1). Presumed cause of his nausea and diarrhea was viral gastroenteritis likely acquired at a homeless shelter.

Once stabilized, Mr. W was admitted to the VA hospital inpatient psychiatry unit under involuntary commitment for acute mania. Risperidone 0.25 mg orally twice a day was started for mood stabilization and psychosis along with trazodone 50 mg orally as needed for insomnia. Despite upward titration and change in frequency of the risperidone dose, Mr. W’s manic episode persisted. He remained on the psychiatric floor for 2 months (Figure). His TSH and free T4 were monitored during his stay, and levothyroxine was started. Risperidone was titrated to 8 mg/d. Mr. W’s Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score decreased from 30 to 24. Mr. W had a mild improvement in irritability and speech rate but little change in elevated mood and delusional content.

He continued to endorse “speaking to god 16 times” even at the highest risperidone dose. The treatment team prescribed dissolvable risperidone tablets secondary to diversion concerns. In addition, the team added benztropine 0.5 mg once a day after observing a stooped posture and decreased arm swing. Mr. W noted risperidone made him “lethargic” and that his “body did not need” it. After 1 month of treatment with risperidone, the treatment team decided to cross taper the veteran from risperidone to a combination of olanzapine and divalproex secondary to inadequate treatment response.

The inpatient team started Mr. W on oral disintegrating tablets of olanzapine 5 mg once a day, and oral divalproex 1,000 mg once a day. An intramuscular backup of olanzapine was made available if oral medication was refused. Divalproex was titrated to 1,250 mg once a day to target a serum level of 61.7 µg/mL, and olanzapine was titrated to 10 mg once a day. After 9 days, the veteran showed moderate improvement in mania symptoms with a YMRS score < 20, indicating the absence of mania. However, the veteran made it very clear that he would stop taking the prescribed medication on discharge. The team elected to initiate a LAI.

The veteran received his first injection of the LAI psychiatric medication paliperidone palmitate 234 mg and a second 156-mg injection of the same medication 1 week later as per loading protocol. He was concurrently on daily oral divalproex 1,250 mg and olanzapine 10 mg. Mr. W continued to note he felt sedated during this period; his sedation worsened after the second injection. He also began to forget the location of his room and developed mumbled speech. His gait deteriorated to where he required a walker 6 days after injection and a wheelchair 3 days later. He became incontinent of urine and feces. Mr. W exhibited masked facies with severe drooling. This eventually progressed to difficulty swallowing. At the advice of speech pathology, he was downgraded to a pureed and nectar-thick liquid diet. He required assistance with meals.

Because of his sedation and parkinsonism symptoms, he was tapered off both olanzapine and divalproex. His last dose of olanzapine was on the date of his first injection and last dose of divalproex was 15 days after the second injection. The benztropine, which was originally given to counteract the effects of risperidone monotherapy, was discontinued over concern of anticholinergic load and sedation. The neurology consultant recommended carbidopa 25 mg and levodopa 100 mg 3 times per day for treatment of parkinsonism symptoms. Mr. W was only able to take 1 dose because of trouble swallowing. Twenty days after his second injection, a rapid response team (local clinical team 1 step below a code team) was called as Mr. W was unusually lethargic and unable to eat. He was then transferred to the medical floor.

While on the medical floor, dobhoff tube access was established for nutrition and to allow administration of carbidopa and levodopa. Mr. W could still speak at this time and was distraught. He stated, “I don’t know why god would do this to me.” Further workup was performed to look for other etiologies of the patient’s change in status. Creatinine kinase testing, lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) bacterial culture, CSF cryptococcal testing, and syphilis antigens were all negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated diffuse cerebral atrophy with widened cistern and sulci resulting in ex vacuo dilatation.

Neurology thought that the ventriculomegaly did not have features of normal pressure hydrocephalus and was secondary to chronic ischemic demyelination caused by chronic malnutrition. During follow-up visits, the veteran was less and less verbal. It progressed to where he answered questions only in grunts. Eight days after transfer to the medical floor, Mr. W was noted to have his neck locked in a laterally rotated position with clonus of the sternocleidomastoid. Due to concern about possibility of neck dystonia and the poor adherence of the patient with carbidopa and levodopa given orally, the psychiatric team made the recommendation to start benztropine 1 mg given twice a day, delivered via the dobhoff tube to treat both the parkinsonism and dystonia. The following day Mr. W failed a repeat swallow study and was no longer allowed to receive anything orally.

Mild icterus and jaundice were noted on physical examination along with transaminitis and elevated bilirubin. He developed a fever. Thirteen days after transfer to the medical floor, blood cultures revealed Klebsiella septicemia. Benztropine was discontinued at this time because of concern the medication was causing or exacerbating the fever. While being treated for Klebsiella sepsis, the psychiatry team addressed his continued hypophonia, inability to ambulate, masked facies, and neck dystonia with diphenhydramine 50 mg given intramuscular (IM) twice per day.

Mr. W developed several more iatrogenic complications near this time, including urinary tract infection septicemia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure with lung infiltrate on X-ray, requiring ventilator support. His clinical status led to a number of transfers in and out of the medical intensive care unit (MICU). During this time, his parkinsonism symptoms were managed through a combination of carbidopa and levodopa and amantadine. Cervical dystonia was managed with botulism toxin injections. Mr. W spent 6 weeks in the MICU until the decision was made to terminate life support, and he was taken off the ventilator. He died shortly thereafter. Autopsy findings suggested that Mr. W had severe Alzheimer disease.

Discussion

Following the IM injection of paliperidone palmitate, Mr. W had a complicated hospital stay resulting in his demise from sepsis and multiorgan failure. Severe immobilization, rigidity, and dystonia prevented Mr. W from conducting activities of daily living, which resulted in invasive interventions, such as continued foley catheterization. His sepsis was likely secondary to aspiration, catheterization, and eventual ventilation—all iatrogenic complications. Previous estimates in the U.S. have suggested a total of 225,000 deaths per year from iatrogenic causes.8

There are several areas of concern. Clearly, Mr. W had severe illness that greatly affected his life. He was estranged from family and had endured a 2-decade period of homelessness. He deserved effective treatment for his psychiatric illness to relieve his suffering. His long period of mental illness without effective treatment very likely biased the initial treatment team toward an aggressive approach.

Fragmented Care

The prolonged hospital stay and multiple complications directly led to fragmentation in Mr. W’s care. He was hospitalized for months on 3 different main services: psychiatry, medicine, and the MICU. Even when he remained on the same service, the primary members of his treatment team changed every few weeks. Many different specialties were consulted and reconsulted. Members of the specialty consult teams changed throughout the hospitalization as well. Given the nature of the local clinical administration, Mr. W likely received the most consistent team members from the attendings on the psychiatry consult-liaison service (who do not rotate) and from a local subspecialty delirium consult team (all members stay consistent except pharmacy residents).

Documentation of clinical reasoning behind treatment decisions was not ideal and occasionally lacking. This led to a tendency to “reinvent the wheel” with Mr. W’s treatment approach every few weeks. It was not until Mr. W had spent a significant amount of time on the medical service that an interdisciplinary treatment team meeting involving medicine, psychiatry, nursing, delirium, and neurology experts occurred. Although the interdisciplinary meeting helped by reviewing the hospital course, agreeing on a likely cause of the symptoms, and creating a treatment plan going forward, Mr. W was not able to recover.

Even when team members were stable, communication in a timely fashion did not always occur. At several points, expert recommendations were delayed by a day or more. Difficulties in treatment implementation were not communicated back to the specialty teams. The most significant example was a delay in recognition when Mr. W could no longer take oral pills secondary to the parkinsonism. Many days passed before an alternative liquid or dissolved medication was recommended on 2 separate occasions.

Subspecialty Consult

Addressing these documentation, communication, and transition challenges is neither easy nor unique to this large rural VA medical center. The authors have attempted to address this in the local system with the creation of a delirium team subspecialty consult service. Team members do not rotate and are able to follow patients throughout their hospital course. At the time of Mr. W’s hospitalization, the team included representatives from nursing, psychiatry, and occasionally pharmacy. Since then, it has expanded to include geriatrics and medicine. In addition to delirium being a marker for complex patients at risk for hospital complications, medical reasons for an extended length of stay could serve as a trigger for a referral to such a team of experts. In Mr. W’s case, that could have led to interdisciplinary consultation up to 2 months before it occurred. This may have led to a much better outcome.

Secondary parkinsonism is most notable with the typical antipychotics. The prevalence can vary between 50% and 75% and may be higher within the elderly population. However, all antipsychotics have a chance of demonstrating EPS. Risperidone has a low incidence at low doses; studies have shown dose-related parkinsonism at doses of 2 to 6 mg/d. Significant risk of parkinsonism is further exacerbated when drug-drug interactions are considered.9 Concurrently receiving 2 antipsychotics, olanzapine and paliperidone, initially caused the EPS. The veteran’s cerebral atrophy from significant malnutrition related to chronic homelessness, and the presence of Alzheimer disease only identified postmortem exacerbated this AE. Further complicating the management of the EPS, paliperidone palmitate has a long half-life of 25 to 49 days.9 Simply discontinuing the medication did not remove it from Mr. W’s system. Paliperidone would have continued to be present for months.

Conclusion

In this case, aggressive changes in the antipsychotic medications in a short period led to Mr. W effectively having 3 different agents in his system at the same time. This significantly elevated his risk of AEs, including parkinsonism. The clinician must be vigilant to further recognize the initial symptoms of parkinsonism on clinical presentation. Administration of clinical scales, such as the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effect, can help in these situations.10 Malnutrition and increased age can predispose patients to neurolepticAEs, so treatment teams should exercise caution when administering antipsychotics in such a population. Pharmacokinetic changes in all major organ systems from aging result in higher and more variable drug concentrations. This leads to an increased sensitivity to drugs and AEs.9

Given the increasing geriatric patient population in the U.S., treating mania in the elderly will become more common. Providers should carefully consider the risks vs benefit ratio for each individual because a serious adverse reaction may result in detrimental consequences. Even with severe symptoms leading to a bias toward an aggressive approach, it may be better to “start low and go slow.” Early inclusion of interdisciplinary expertise should be sought in complex cases.

1. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Bourne ML, West SA. Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):87-91.

2. Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, McAuley H, Ritchie K. The patient’s primary group. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:74-86.

3. Buoli M, Ciappolino V, Altamura AC. Paliperidone palmitate depot in the long-term treatment of psychotic bipolar disorder: a case series. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):209-211.

4. Chou YH, Chu PC, Wu SW, et al. A systematic review and experts’ consensus for long-acting injectable antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):121-128.

5. Kishi T, Oya K, Iwata N. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(9):1-10.

6. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

7. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

8. Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000;284(4):483-485.

9. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Arana GW. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

10. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11-19.

Many patients with psychiatric illness have difficulty with medication adherence. Patients with impaired reality testing especially are at risk.

Keck and McElroy evaluated 141 patients who were initially hospitalized for bipolar disorder prospectively over 1 year to assess adherence with medication. During the follow-up period, 71 patients (51%) were partially or totally nonadherent with medication as prescribed. The most commonly cited reason for nonadherence was denial of need.1

Clinicians and patients face additional challenges due to the deleterious effects of relapse in the setting of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Almost all oral antipsychotic or mood stabilizer medications require a minimum dosing schedule to effectively treat these disorders, and some of these oral medications require regular laboratory monitoring. Moreover, some of the agents can have serious adverse effects (AEs), such as seizure or withdrawal, if stopped abruptly. Social support from family or friends may improve adherence, but many psychiatric outpatients have a smaller social support network than do patients without psychiatric illnesses.2

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have been available for the past 40 years. These medications have provided clinicians with an additional option for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who are nonadherent to their medication treatment plans or who desire an administration choice that is more convenient than daily oral pills.3-7 Some clinical practice guidelines recommend considering LAIs as a maintenance treatment for schizophrenia.5 Like the rest of the pharmacopoeia, these formulations have AEs, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and metabolic syndrome.1 The longer half-life of these drugs may make such effects difficult to reverse.

This article presents a case of the use of depot formulation paliperidone palmitate in an elderly patient with bipolar disorder who was previously on high-dose oral second generation antipsychotics. He developed severe parkinsonism during a protracted hospitalization that ended in death.

Case Presentation

Mr. W was a 68-year-old homeless white male with a history of coronary artery disease status-post coronary artery bypass surgery, obstructive sleep apnea, and bipolar 1 disorder who presented to a large rural VAMC emergency department (ED) as a transfer from an outside hospital (OSH). He originally presented at the OSH for vomiting and diarrhea, but while there, he was placed under involuntary psychiatric commitment. The involuntary commitment form noted him to be tangential and disorganized; he was found walking about the ED without clothes. During the initial psychiatry interview, the clinician noted a disorganized thought process. When asked about circumstances leading to admission, he stated he was “a scuba diver, pilot, actor, submarine commander.” He also reported he had given “seminars to 6,000 people,” he held a psychology degree, and he came from a family that owned part of the island of Kodiak, Alaska. Mr. W stated he had no mental health history and believed psychiatry was witchcraft. He reported having no hallucinations and stated he heard the voice of god. He also reported to have met god multiple times and to have been married to a supermodel.

Mr. W’s chart demonstrated a history of mental illness over 30 years and that he previously was prescribed psychiatric medications. He had multiple inpatient psychiatric admissions with grandiose ideations, disorganized behaviors, and hypersexuality. He had been prescribed quetiapine, divalproex, lithium, carbamazepine, and lorazepam. He was formally diagnosed in the past with bipolar 1 disorder. There also was a family history of psychiatric illness. His mother had received electroconvulsive therapy, and both parents had alcohol substance use disorder.

Mr. W had been homeless for 20 years and had several psychiatric admissions during this period. Mr. W also had chronic difficulty with obtaining food and taking medications as prescribed. Sometimes he would only be able to eat 1 to 2 meals per day. He often changed location and had lived in at least 7 different states. Currently, he was estranged from his family. About 19 years ago, his sister reported that the veteran had told her that he was Jesus Christ, per clinical records. His estranged sister’s statement was corroborated by past psychology consult records citing episodes of the patient hearing god 30 and 26 years before the current admission. His second ex-wife cited inappropriate sexual behavior in front of their children. He had difficulty in school, failed at least 2 grades, and joined the U.S. Navy in tenth grade. A Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination given 19 years ago showed mild impairment on attention and severe impairment in memory.

The physical examination on presentation to the OSH was unremarkable. Mr. W did not cooperate with formal neurocognitive testing, and he consistently made errors during orientation testing. Complete blood count from a OSH ED laboratory test was remarkable for a mild pancytopenia with a leukocyte count of 3,100 cells/mcL, hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 38.4%. Red cell distribution width was within normal limits at 13.5%. Stool cultures showed normal fecal flora and no salmonella, shigella, or campylobacter. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was slightly elevated at 5.32 U/mL. An electrocardiogram showed a QTc interval of 412 ms. A computerized tomography scan of his head showed no acute intracranial abnormality along with chronic ischemic changes in the brain (Table 1). Presumed cause of his nausea and diarrhea was viral gastroenteritis likely acquired at a homeless shelter.

Once stabilized, Mr. W was admitted to the VA hospital inpatient psychiatry unit under involuntary commitment for acute mania. Risperidone 0.25 mg orally twice a day was started for mood stabilization and psychosis along with trazodone 50 mg orally as needed for insomnia. Despite upward titration and change in frequency of the risperidone dose, Mr. W’s manic episode persisted. He remained on the psychiatric floor for 2 months (Figure). His TSH and free T4 were monitored during his stay, and levothyroxine was started. Risperidone was titrated to 8 mg/d. Mr. W’s Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score decreased from 30 to 24. Mr. W had a mild improvement in irritability and speech rate but little change in elevated mood and delusional content.

He continued to endorse “speaking to god 16 times” even at the highest risperidone dose. The treatment team prescribed dissolvable risperidone tablets secondary to diversion concerns. In addition, the team added benztropine 0.5 mg once a day after observing a stooped posture and decreased arm swing. Mr. W noted risperidone made him “lethargic” and that his “body did not need” it. After 1 month of treatment with risperidone, the treatment team decided to cross taper the veteran from risperidone to a combination of olanzapine and divalproex secondary to inadequate treatment response.

The inpatient team started Mr. W on oral disintegrating tablets of olanzapine 5 mg once a day, and oral divalproex 1,000 mg once a day. An intramuscular backup of olanzapine was made available if oral medication was refused. Divalproex was titrated to 1,250 mg once a day to target a serum level of 61.7 µg/mL, and olanzapine was titrated to 10 mg once a day. After 9 days, the veteran showed moderate improvement in mania symptoms with a YMRS score < 20, indicating the absence of mania. However, the veteran made it very clear that he would stop taking the prescribed medication on discharge. The team elected to initiate a LAI.

The veteran received his first injection of the LAI psychiatric medication paliperidone palmitate 234 mg and a second 156-mg injection of the same medication 1 week later as per loading protocol. He was concurrently on daily oral divalproex 1,250 mg and olanzapine 10 mg. Mr. W continued to note he felt sedated during this period; his sedation worsened after the second injection. He also began to forget the location of his room and developed mumbled speech. His gait deteriorated to where he required a walker 6 days after injection and a wheelchair 3 days later. He became incontinent of urine and feces. Mr. W exhibited masked facies with severe drooling. This eventually progressed to difficulty swallowing. At the advice of speech pathology, he was downgraded to a pureed and nectar-thick liquid diet. He required assistance with meals.

Because of his sedation and parkinsonism symptoms, he was tapered off both olanzapine and divalproex. His last dose of olanzapine was on the date of his first injection and last dose of divalproex was 15 days after the second injection. The benztropine, which was originally given to counteract the effects of risperidone monotherapy, was discontinued over concern of anticholinergic load and sedation. The neurology consultant recommended carbidopa 25 mg and levodopa 100 mg 3 times per day for treatment of parkinsonism symptoms. Mr. W was only able to take 1 dose because of trouble swallowing. Twenty days after his second injection, a rapid response team (local clinical team 1 step below a code team) was called as Mr. W was unusually lethargic and unable to eat. He was then transferred to the medical floor.

While on the medical floor, dobhoff tube access was established for nutrition and to allow administration of carbidopa and levodopa. Mr. W could still speak at this time and was distraught. He stated, “I don’t know why god would do this to me.” Further workup was performed to look for other etiologies of the patient’s change in status. Creatinine kinase testing, lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) bacterial culture, CSF cryptococcal testing, and syphilis antigens were all negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated diffuse cerebral atrophy with widened cistern and sulci resulting in ex vacuo dilatation.

Neurology thought that the ventriculomegaly did not have features of normal pressure hydrocephalus and was secondary to chronic ischemic demyelination caused by chronic malnutrition. During follow-up visits, the veteran was less and less verbal. It progressed to where he answered questions only in grunts. Eight days after transfer to the medical floor, Mr. W was noted to have his neck locked in a laterally rotated position with clonus of the sternocleidomastoid. Due to concern about possibility of neck dystonia and the poor adherence of the patient with carbidopa and levodopa given orally, the psychiatric team made the recommendation to start benztropine 1 mg given twice a day, delivered via the dobhoff tube to treat both the parkinsonism and dystonia. The following day Mr. W failed a repeat swallow study and was no longer allowed to receive anything orally.

Mild icterus and jaundice were noted on physical examination along with transaminitis and elevated bilirubin. He developed a fever. Thirteen days after transfer to the medical floor, blood cultures revealed Klebsiella septicemia. Benztropine was discontinued at this time because of concern the medication was causing or exacerbating the fever. While being treated for Klebsiella sepsis, the psychiatry team addressed his continued hypophonia, inability to ambulate, masked facies, and neck dystonia with diphenhydramine 50 mg given intramuscular (IM) twice per day.

Mr. W developed several more iatrogenic complications near this time, including urinary tract infection septicemia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure with lung infiltrate on X-ray, requiring ventilator support. His clinical status led to a number of transfers in and out of the medical intensive care unit (MICU). During this time, his parkinsonism symptoms were managed through a combination of carbidopa and levodopa and amantadine. Cervical dystonia was managed with botulism toxin injections. Mr. W spent 6 weeks in the MICU until the decision was made to terminate life support, and he was taken off the ventilator. He died shortly thereafter. Autopsy findings suggested that Mr. W had severe Alzheimer disease.

Discussion

Following the IM injection of paliperidone palmitate, Mr. W had a complicated hospital stay resulting in his demise from sepsis and multiorgan failure. Severe immobilization, rigidity, and dystonia prevented Mr. W from conducting activities of daily living, which resulted in invasive interventions, such as continued foley catheterization. His sepsis was likely secondary to aspiration, catheterization, and eventual ventilation—all iatrogenic complications. Previous estimates in the U.S. have suggested a total of 225,000 deaths per year from iatrogenic causes.8

There are several areas of concern. Clearly, Mr. W had severe illness that greatly affected his life. He was estranged from family and had endured a 2-decade period of homelessness. He deserved effective treatment for his psychiatric illness to relieve his suffering. His long period of mental illness without effective treatment very likely biased the initial treatment team toward an aggressive approach.

Fragmented Care

The prolonged hospital stay and multiple complications directly led to fragmentation in Mr. W’s care. He was hospitalized for months on 3 different main services: psychiatry, medicine, and the MICU. Even when he remained on the same service, the primary members of his treatment team changed every few weeks. Many different specialties were consulted and reconsulted. Members of the specialty consult teams changed throughout the hospitalization as well. Given the nature of the local clinical administration, Mr. W likely received the most consistent team members from the attendings on the psychiatry consult-liaison service (who do not rotate) and from a local subspecialty delirium consult team (all members stay consistent except pharmacy residents).

Documentation of clinical reasoning behind treatment decisions was not ideal and occasionally lacking. This led to a tendency to “reinvent the wheel” with Mr. W’s treatment approach every few weeks. It was not until Mr. W had spent a significant amount of time on the medical service that an interdisciplinary treatment team meeting involving medicine, psychiatry, nursing, delirium, and neurology experts occurred. Although the interdisciplinary meeting helped by reviewing the hospital course, agreeing on a likely cause of the symptoms, and creating a treatment plan going forward, Mr. W was not able to recover.

Even when team members were stable, communication in a timely fashion did not always occur. At several points, expert recommendations were delayed by a day or more. Difficulties in treatment implementation were not communicated back to the specialty teams. The most significant example was a delay in recognition when Mr. W could no longer take oral pills secondary to the parkinsonism. Many days passed before an alternative liquid or dissolved medication was recommended on 2 separate occasions.

Subspecialty Consult

Addressing these documentation, communication, and transition challenges is neither easy nor unique to this large rural VA medical center. The authors have attempted to address this in the local system with the creation of a delirium team subspecialty consult service. Team members do not rotate and are able to follow patients throughout their hospital course. At the time of Mr. W’s hospitalization, the team included representatives from nursing, psychiatry, and occasionally pharmacy. Since then, it has expanded to include geriatrics and medicine. In addition to delirium being a marker for complex patients at risk for hospital complications, medical reasons for an extended length of stay could serve as a trigger for a referral to such a team of experts. In Mr. W’s case, that could have led to interdisciplinary consultation up to 2 months before it occurred. This may have led to a much better outcome.

Secondary parkinsonism is most notable with the typical antipychotics. The prevalence can vary between 50% and 75% and may be higher within the elderly population. However, all antipsychotics have a chance of demonstrating EPS. Risperidone has a low incidence at low doses; studies have shown dose-related parkinsonism at doses of 2 to 6 mg/d. Significant risk of parkinsonism is further exacerbated when drug-drug interactions are considered.9 Concurrently receiving 2 antipsychotics, olanzapine and paliperidone, initially caused the EPS. The veteran’s cerebral atrophy from significant malnutrition related to chronic homelessness, and the presence of Alzheimer disease only identified postmortem exacerbated this AE. Further complicating the management of the EPS, paliperidone palmitate has a long half-life of 25 to 49 days.9 Simply discontinuing the medication did not remove it from Mr. W’s system. Paliperidone would have continued to be present for months.

Conclusion

In this case, aggressive changes in the antipsychotic medications in a short period led to Mr. W effectively having 3 different agents in his system at the same time. This significantly elevated his risk of AEs, including parkinsonism. The clinician must be vigilant to further recognize the initial symptoms of parkinsonism on clinical presentation. Administration of clinical scales, such as the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effect, can help in these situations.10 Malnutrition and increased age can predispose patients to neurolepticAEs, so treatment teams should exercise caution when administering antipsychotics in such a population. Pharmacokinetic changes in all major organ systems from aging result in higher and more variable drug concentrations. This leads to an increased sensitivity to drugs and AEs.9

Given the increasing geriatric patient population in the U.S., treating mania in the elderly will become more common. Providers should carefully consider the risks vs benefit ratio for each individual because a serious adverse reaction may result in detrimental consequences. Even with severe symptoms leading to a bias toward an aggressive approach, it may be better to “start low and go slow.” Early inclusion of interdisciplinary expertise should be sought in complex cases.

Many patients with psychiatric illness have difficulty with medication adherence. Patients with impaired reality testing especially are at risk.

Keck and McElroy evaluated 141 patients who were initially hospitalized for bipolar disorder prospectively over 1 year to assess adherence with medication. During the follow-up period, 71 patients (51%) were partially or totally nonadherent with medication as prescribed. The most commonly cited reason for nonadherence was denial of need.1

Clinicians and patients face additional challenges due to the deleterious effects of relapse in the setting of both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Almost all oral antipsychotic or mood stabilizer medications require a minimum dosing schedule to effectively treat these disorders, and some of these oral medications require regular laboratory monitoring. Moreover, some of the agents can have serious adverse effects (AEs), such as seizure or withdrawal, if stopped abruptly. Social support from family or friends may improve adherence, but many psychiatric outpatients have a smaller social support network than do patients without psychiatric illnesses.2

Long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics have been available for the past 40 years. These medications have provided clinicians with an additional option for patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder who are nonadherent to their medication treatment plans or who desire an administration choice that is more convenient than daily oral pills.3-7 Some clinical practice guidelines recommend considering LAIs as a maintenance treatment for schizophrenia.5 Like the rest of the pharmacopoeia, these formulations have AEs, such as extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), weight gain, and metabolic syndrome.1 The longer half-life of these drugs may make such effects difficult to reverse.

This article presents a case of the use of depot formulation paliperidone palmitate in an elderly patient with bipolar disorder who was previously on high-dose oral second generation antipsychotics. He developed severe parkinsonism during a protracted hospitalization that ended in death.

Case Presentation

Mr. W was a 68-year-old homeless white male with a history of coronary artery disease status-post coronary artery bypass surgery, obstructive sleep apnea, and bipolar 1 disorder who presented to a large rural VAMC emergency department (ED) as a transfer from an outside hospital (OSH). He originally presented at the OSH for vomiting and diarrhea, but while there, he was placed under involuntary psychiatric commitment. The involuntary commitment form noted him to be tangential and disorganized; he was found walking about the ED without clothes. During the initial psychiatry interview, the clinician noted a disorganized thought process. When asked about circumstances leading to admission, he stated he was “a scuba diver, pilot, actor, submarine commander.” He also reported he had given “seminars to 6,000 people,” he held a psychology degree, and he came from a family that owned part of the island of Kodiak, Alaska. Mr. W stated he had no mental health history and believed psychiatry was witchcraft. He reported having no hallucinations and stated he heard the voice of god. He also reported to have met god multiple times and to have been married to a supermodel.

Mr. W’s chart demonstrated a history of mental illness over 30 years and that he previously was prescribed psychiatric medications. He had multiple inpatient psychiatric admissions with grandiose ideations, disorganized behaviors, and hypersexuality. He had been prescribed quetiapine, divalproex, lithium, carbamazepine, and lorazepam. He was formally diagnosed in the past with bipolar 1 disorder. There also was a family history of psychiatric illness. His mother had received electroconvulsive therapy, and both parents had alcohol substance use disorder.

Mr. W had been homeless for 20 years and had several psychiatric admissions during this period. Mr. W also had chronic difficulty with obtaining food and taking medications as prescribed. Sometimes he would only be able to eat 1 to 2 meals per day. He often changed location and had lived in at least 7 different states. Currently, he was estranged from his family. About 19 years ago, his sister reported that the veteran had told her that he was Jesus Christ, per clinical records. His estranged sister’s statement was corroborated by past psychology consult records citing episodes of the patient hearing god 30 and 26 years before the current admission. His second ex-wife cited inappropriate sexual behavior in front of their children. He had difficulty in school, failed at least 2 grades, and joined the U.S. Navy in tenth grade. A Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination given 19 years ago showed mild impairment on attention and severe impairment in memory.

The physical examination on presentation to the OSH was unremarkable. Mr. W did not cooperate with formal neurocognitive testing, and he consistently made errors during orientation testing. Complete blood count from a OSH ED laboratory test was remarkable for a mild pancytopenia with a leukocyte count of 3,100 cells/mcL, hemoglobin 13.1 g/dL, and hematocrit 38.4%. Red cell distribution width was within normal limits at 13.5%. Stool cultures showed normal fecal flora and no salmonella, shigella, or campylobacter. Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) was slightly elevated at 5.32 U/mL. An electrocardiogram showed a QTc interval of 412 ms. A computerized tomography scan of his head showed no acute intracranial abnormality along with chronic ischemic changes in the brain (Table 1). Presumed cause of his nausea and diarrhea was viral gastroenteritis likely acquired at a homeless shelter.

Once stabilized, Mr. W was admitted to the VA hospital inpatient psychiatry unit under involuntary commitment for acute mania. Risperidone 0.25 mg orally twice a day was started for mood stabilization and psychosis along with trazodone 50 mg orally as needed for insomnia. Despite upward titration and change in frequency of the risperidone dose, Mr. W’s manic episode persisted. He remained on the psychiatric floor for 2 months (Figure). His TSH and free T4 were monitored during his stay, and levothyroxine was started. Risperidone was titrated to 8 mg/d. Mr. W’s Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) score decreased from 30 to 24. Mr. W had a mild improvement in irritability and speech rate but little change in elevated mood and delusional content.

He continued to endorse “speaking to god 16 times” even at the highest risperidone dose. The treatment team prescribed dissolvable risperidone tablets secondary to diversion concerns. In addition, the team added benztropine 0.5 mg once a day after observing a stooped posture and decreased arm swing. Mr. W noted risperidone made him “lethargic” and that his “body did not need” it. After 1 month of treatment with risperidone, the treatment team decided to cross taper the veteran from risperidone to a combination of olanzapine and divalproex secondary to inadequate treatment response.

The inpatient team started Mr. W on oral disintegrating tablets of olanzapine 5 mg once a day, and oral divalproex 1,000 mg once a day. An intramuscular backup of olanzapine was made available if oral medication was refused. Divalproex was titrated to 1,250 mg once a day to target a serum level of 61.7 µg/mL, and olanzapine was titrated to 10 mg once a day. After 9 days, the veteran showed moderate improvement in mania symptoms with a YMRS score < 20, indicating the absence of mania. However, the veteran made it very clear that he would stop taking the prescribed medication on discharge. The team elected to initiate a LAI.

The veteran received his first injection of the LAI psychiatric medication paliperidone palmitate 234 mg and a second 156-mg injection of the same medication 1 week later as per loading protocol. He was concurrently on daily oral divalproex 1,250 mg and olanzapine 10 mg. Mr. W continued to note he felt sedated during this period; his sedation worsened after the second injection. He also began to forget the location of his room and developed mumbled speech. His gait deteriorated to where he required a walker 6 days after injection and a wheelchair 3 days later. He became incontinent of urine and feces. Mr. W exhibited masked facies with severe drooling. This eventually progressed to difficulty swallowing. At the advice of speech pathology, he was downgraded to a pureed and nectar-thick liquid diet. He required assistance with meals.

Because of his sedation and parkinsonism symptoms, he was tapered off both olanzapine and divalproex. His last dose of olanzapine was on the date of his first injection and last dose of divalproex was 15 days after the second injection. The benztropine, which was originally given to counteract the effects of risperidone monotherapy, was discontinued over concern of anticholinergic load and sedation. The neurology consultant recommended carbidopa 25 mg and levodopa 100 mg 3 times per day for treatment of parkinsonism symptoms. Mr. W was only able to take 1 dose because of trouble swallowing. Twenty days after his second injection, a rapid response team (local clinical team 1 step below a code team) was called as Mr. W was unusually lethargic and unable to eat. He was then transferred to the medical floor.

While on the medical floor, dobhoff tube access was established for nutrition and to allow administration of carbidopa and levodopa. Mr. W could still speak at this time and was distraught. He stated, “I don’t know why god would do this to me.” Further workup was performed to look for other etiologies of the patient’s change in status. Creatinine kinase testing, lumbar puncture with cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) bacterial culture, CSF cryptococcal testing, and syphilis antigens were all negative. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain demonstrated diffuse cerebral atrophy with widened cistern and sulci resulting in ex vacuo dilatation.

Neurology thought that the ventriculomegaly did not have features of normal pressure hydrocephalus and was secondary to chronic ischemic demyelination caused by chronic malnutrition. During follow-up visits, the veteran was less and less verbal. It progressed to where he answered questions only in grunts. Eight days after transfer to the medical floor, Mr. W was noted to have his neck locked in a laterally rotated position with clonus of the sternocleidomastoid. Due to concern about possibility of neck dystonia and the poor adherence of the patient with carbidopa and levodopa given orally, the psychiatric team made the recommendation to start benztropine 1 mg given twice a day, delivered via the dobhoff tube to treat both the parkinsonism and dystonia. The following day Mr. W failed a repeat swallow study and was no longer allowed to receive anything orally.

Mild icterus and jaundice were noted on physical examination along with transaminitis and elevated bilirubin. He developed a fever. Thirteen days after transfer to the medical floor, blood cultures revealed Klebsiella septicemia. Benztropine was discontinued at this time because of concern the medication was causing or exacerbating the fever. While being treated for Klebsiella sepsis, the psychiatry team addressed his continued hypophonia, inability to ambulate, masked facies, and neck dystonia with diphenhydramine 50 mg given intramuscular (IM) twice per day.

Mr. W developed several more iatrogenic complications near this time, including urinary tract infection septicemia and acute hypoxic respiratory failure with lung infiltrate on X-ray, requiring ventilator support. His clinical status led to a number of transfers in and out of the medical intensive care unit (MICU). During this time, his parkinsonism symptoms were managed through a combination of carbidopa and levodopa and amantadine. Cervical dystonia was managed with botulism toxin injections. Mr. W spent 6 weeks in the MICU until the decision was made to terminate life support, and he was taken off the ventilator. He died shortly thereafter. Autopsy findings suggested that Mr. W had severe Alzheimer disease.

Discussion

Following the IM injection of paliperidone palmitate, Mr. W had a complicated hospital stay resulting in his demise from sepsis and multiorgan failure. Severe immobilization, rigidity, and dystonia prevented Mr. W from conducting activities of daily living, which resulted in invasive interventions, such as continued foley catheterization. His sepsis was likely secondary to aspiration, catheterization, and eventual ventilation—all iatrogenic complications. Previous estimates in the U.S. have suggested a total of 225,000 deaths per year from iatrogenic causes.8

There are several areas of concern. Clearly, Mr. W had severe illness that greatly affected his life. He was estranged from family and had endured a 2-decade period of homelessness. He deserved effective treatment for his psychiatric illness to relieve his suffering. His long period of mental illness without effective treatment very likely biased the initial treatment team toward an aggressive approach.

Fragmented Care

The prolonged hospital stay and multiple complications directly led to fragmentation in Mr. W’s care. He was hospitalized for months on 3 different main services: psychiatry, medicine, and the MICU. Even when he remained on the same service, the primary members of his treatment team changed every few weeks. Many different specialties were consulted and reconsulted. Members of the specialty consult teams changed throughout the hospitalization as well. Given the nature of the local clinical administration, Mr. W likely received the most consistent team members from the attendings on the psychiatry consult-liaison service (who do not rotate) and from a local subspecialty delirium consult team (all members stay consistent except pharmacy residents).

Documentation of clinical reasoning behind treatment decisions was not ideal and occasionally lacking. This led to a tendency to “reinvent the wheel” with Mr. W’s treatment approach every few weeks. It was not until Mr. W had spent a significant amount of time on the medical service that an interdisciplinary treatment team meeting involving medicine, psychiatry, nursing, delirium, and neurology experts occurred. Although the interdisciplinary meeting helped by reviewing the hospital course, agreeing on a likely cause of the symptoms, and creating a treatment plan going forward, Mr. W was not able to recover.

Even when team members were stable, communication in a timely fashion did not always occur. At several points, expert recommendations were delayed by a day or more. Difficulties in treatment implementation were not communicated back to the specialty teams. The most significant example was a delay in recognition when Mr. W could no longer take oral pills secondary to the parkinsonism. Many days passed before an alternative liquid or dissolved medication was recommended on 2 separate occasions.

Subspecialty Consult

Addressing these documentation, communication, and transition challenges is neither easy nor unique to this large rural VA medical center. The authors have attempted to address this in the local system with the creation of a delirium team subspecialty consult service. Team members do not rotate and are able to follow patients throughout their hospital course. At the time of Mr. W’s hospitalization, the team included representatives from nursing, psychiatry, and occasionally pharmacy. Since then, it has expanded to include geriatrics and medicine. In addition to delirium being a marker for complex patients at risk for hospital complications, medical reasons for an extended length of stay could serve as a trigger for a referral to such a team of experts. In Mr. W’s case, that could have led to interdisciplinary consultation up to 2 months before it occurred. This may have led to a much better outcome.

Secondary parkinsonism is most notable with the typical antipychotics. The prevalence can vary between 50% and 75% and may be higher within the elderly population. However, all antipsychotics have a chance of demonstrating EPS. Risperidone has a low incidence at low doses; studies have shown dose-related parkinsonism at doses of 2 to 6 mg/d. Significant risk of parkinsonism is further exacerbated when drug-drug interactions are considered.9 Concurrently receiving 2 antipsychotics, olanzapine and paliperidone, initially caused the EPS. The veteran’s cerebral atrophy from significant malnutrition related to chronic homelessness, and the presence of Alzheimer disease only identified postmortem exacerbated this AE. Further complicating the management of the EPS, paliperidone palmitate has a long half-life of 25 to 49 days.9 Simply discontinuing the medication did not remove it from Mr. W’s system. Paliperidone would have continued to be present for months.

Conclusion

In this case, aggressive changes in the antipsychotic medications in a short period led to Mr. W effectively having 3 different agents in his system at the same time. This significantly elevated his risk of AEs, including parkinsonism. The clinician must be vigilant to further recognize the initial symptoms of parkinsonism on clinical presentation. Administration of clinical scales, such as the Simpson-Angus Extrapyramidal Side Effect, can help in these situations.10 Malnutrition and increased age can predispose patients to neurolepticAEs, so treatment teams should exercise caution when administering antipsychotics in such a population. Pharmacokinetic changes in all major organ systems from aging result in higher and more variable drug concentrations. This leads to an increased sensitivity to drugs and AEs.9

Given the increasing geriatric patient population in the U.S., treating mania in the elderly will become more common. Providers should carefully consider the risks vs benefit ratio for each individual because a serious adverse reaction may result in detrimental consequences. Even with severe symptoms leading to a bias toward an aggressive approach, it may be better to “start low and go slow.” Early inclusion of interdisciplinary expertise should be sought in complex cases.

1. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Bourne ML, West SA. Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):87-91.

2. Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, McAuley H, Ritchie K. The patient’s primary group. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:74-86.

3. Buoli M, Ciappolino V, Altamura AC. Paliperidone palmitate depot in the long-term treatment of psychotic bipolar disorder: a case series. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):209-211.

4. Chou YH, Chu PC, Wu SW, et al. A systematic review and experts’ consensus for long-acting injectable antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):121-128.

5. Kishi T, Oya K, Iwata N. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(9):1-10.

6. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

7. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

8. Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000;284(4):483-485.

9. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Arana GW. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

10. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11-19.

1. Keck PE Jr, McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Bourne ML, West SA. Compliance with maintenance treatment in bipolar disorder. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1997;33(1):87-91.

2. Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, McAuley H, Ritchie K. The patient’s primary group. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;132:74-86.

3. Buoli M, Ciappolino V, Altamura AC. Paliperidone palmitate depot in the long-term treatment of psychotic bipolar disorder: a case series. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(5):209-211.

4. Chou YH, Chu PC, Wu SW, et al. A systematic review and experts’ consensus for long-acting injectable antipsychotics in bipolar disorder. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2015;13(2):121-128.

5. Kishi T, Oya K, Iwata N. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for prevention of relapse in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;19(9):1-10.

6. Llorca PM, Abbar M, Courtet P, Guillaume S, Lancrenon S, Samalin L. Guidelines for the use and management of long-acting injectable antipsychotics in serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:340.

7. Spanarello S, La Ferla T. The pharmacokinetics of long-acting antipsychotic medications. Curr Clin Pharmacol. 2014;9(3):310-317.

8. Starfield B. Is US health really the best in the world? JAMA. 2000;284(4):483-485.

9. Labbate LA, Fava M, Rosenbaum JF, Arana GW. Handbook of Psychiatric Drug Therapy. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.

10. Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11-19.

Worsening agitation and hallucinations: Could it be PTSD?

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

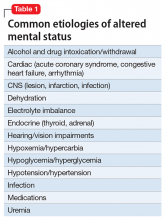

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

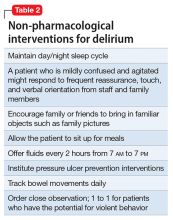

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2

The psychiatry consult service suspects delirium due to polypharmacy or Mr. G’s metastatic brain lesion. However, other collaborating treatment teams feel that Mr. G’s presentation was precipitated by an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms because of the observed psychotic themes, in addition to metabolic encephalopathy. Acute stress disorder can present with emotional numbing, depersonalization, reduced awareness of surroundings, or dissociative amnesia. However, Mr. G has not experienced PTSD symptoms involving mental status changes with fluctuating orientation in the past nor has he displayed persistent dissociation during outpatient psychiatric care. Therefore, it is unlikely that PTSD is the primary cause of his hospital admission.

The palliative care team recommends switching Mr. G’s pain medications to methadone, 20 mg, every 6 hours, to reduce possibility that opioids are contributing to his delirious state. Mr. G’s medical providers report that the chest radiography is suspicious for pneumonia and start him on levofloxacin, 500 mg/d.

The authors’ observations

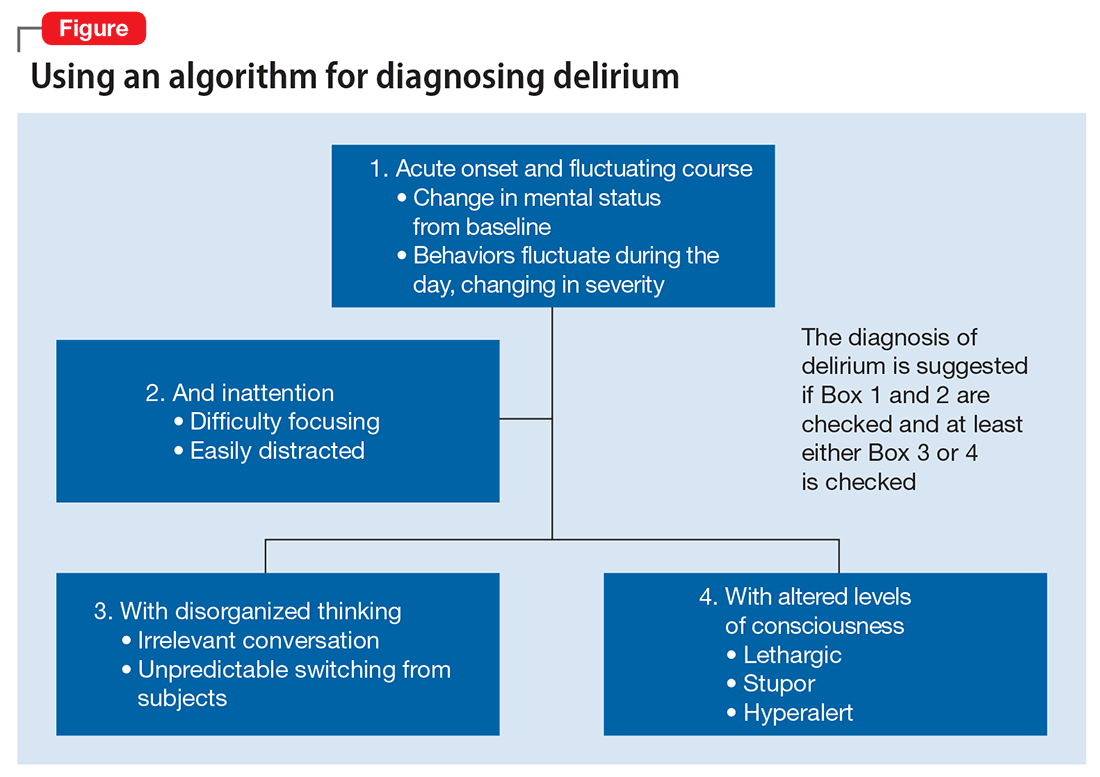

DSM-5 criteria for delirium has 4 components:

- disturbance in attention and awareness

- change in cognition

- the disturbance develops over a short period of time

- there is evidence that the disturbance is a direct consequence of a medical condition, medication, or substance, or more than 1 cause.3

Mr. G presented with multi-factorial delirium, and as a result, all underlying contributions, including infection, polypharmacy, brain metastasis, and steroids needed to be considered. Treating delirium requires investigating the underlying cause and keeping the patient safe in the process (Figure). Mr. G was agitated at presentation; therefore, low-dosage olanzapine was initiated to address the imbalance between the cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in the CNS, which are thought to be the mechanism behind delirious presentations.

In Mr. G’s case, methadone was lowered, with continual monitoring and evaluation for his comfort. Infections, specifically urinary tract infections and pneumonia, can cause delirium states and must be treated with appropriate antibiotics. Metastatic tumors have been known to precipitate changes in mental status and can be ruled out via imaging. In Mr. G’s case, his metastatic lesion remained stable from prior radiographic studies.

TREATMENT Delirium resolves

Mr. G slowly responds to multi-modal treatment including decreased opioids and benzodiazepines and the use of low-dosage antipsychotics. He begins to return to baseline with antibiotic administration. By hospital day 5, Mr. G is alert and oriented. He notes resolution of his auditory and visual hallucinations and denies any persistent paranoia or delusions. The medical team observes Mr. G is having difficulty swallowing with meals, and orders a speech therapy evaluation. After assessment, the team suspects that aspiration pneumonia could have precipitated Mr. G’s initial decline and recommends a mechanic diet with thin liquids to reduce the risk of future aspiration.

Mr. G is discharged home in his wife’s care with home hospice to continue end-of-life care. His medication regimen includes olanzapine, 10 mg/d, to continue until his next outpatient appointment, trazodone, 50 mg/d, for depression and PTSD symptoms, and clonazepam is decreased to 0.5 mg, at bedtime, for anxiety.

The authors’ observations

Mr. G’s case highlights the importance of fully evaluating all common underlying causes of delirium. The etiology of delirium is more likely to be missed in medically complex patients or in patients with a history of psychiatric illness. Palliative care patients have several risk factors for delirium, such as benzodiazepine or opioid treatment, dementia, and organic diseases such as brain metastasis.6 A recent study assessed the frequency of delirium in cancer patients admitted to an inpatient palliative unit and found that 71% of individuals had a diagnosis of delirium at admission and 26% developed delirium afterward.7 Despite the increased likelihood of developing delirium, more than one-half of palliative patients have delirium that is missed by their primary providers.8 Similarly, patients with documented psychiatric illness were approximately 2.5 times more likely to have overlooked delirium compared with patients without psychiatric illness.9

Risk and prevention

Patients with risk factors for delirium—which includes sedative and narcotic usage, advanced cancer, older age, prolonged hospital stays, surgical procedures, and/or cognitive impairment—should receive interventions to prevent delirium. However, if symptoms of AMS are present, providers should perform a complete workup for underlying causes of delirium. Remembering that individuals with delirium have an impaired ability to voice symptoms, such as dyspnea, dysuria, and headache, clinicians should have a high index of suspicion for delirium in patients at heightened risk.10

Perhaps most important, teams treating patients at high risk for delirium should employ preventive measures to reduce the development of delirium. Although more studies are needed to clarify the role of drug therapies for preventing delirium, there is strong evidence for several non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions including:

- frequent orientation activities

- early mobilization

- maintaining healthy sleep–wake cycles

- minimizing the use of psychoactive drugs and frequently reviewing the medication regimen

- allowing use of eyeglasses and hearing aids

- treating volume depletion.10

These preventive measures are important when treating delirium, such as minimizing Mr. G’s use of benzodiazepine and opioids—medications known to contribute to iatrogenic delirium.

A delirium diagnosis portends grave adverse outcomes. Research has shown significant associations with morbidity and mortality, financial and emotional burden, and prolonged hospitalizations. Often, symptoms of delirium persist for months and patients do not recover completely. However, studies have found that when underlying causes are treated effectively, delirium is more likely to be reversible.11

The prompt diagnosis of delirium with good interdisciplinary communication can reduce the risk of these adverse outcomes.12 Consultation-liaison psychiatrists are well positioned to facilitate the diagnoses of delirium and play a role in educating other health care providers of the importance of prevention, early symptom recognition, full workup, and effective treatment of its underlying causes.

1. Posner JB, Saper CB, Schiff ND, et al. Plum and Posner’s diagnosis of stupor and coma. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

2. Skrobik YK, Bergeron N, Dumont M, et al. Olanzapine vs haldoperidol: treating delirium in a critical care setting. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(3):444-449.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

4. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A, et al. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub2.

5. Vella-Brincat J, Macleod AD. Adverse effects of opioids on the central nervous system of palliative care patients. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2007;21(1):15-25.

6. Grassi L, Caraceni A, Mitchell AJ, et al. Management of delirium in palliative care: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(3):550.

7. de la Cruz M, Ransing V, Yennu S, et al. The frequency, characteristics, and outcomes among cancer patients with delirium admitted to an acute palliative care unit. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1425-1431.

8. de la Cruz, M, Fan J, Yennu S, et al. The frequency of missed delirium in patients referred to palliative care in a comprehensive cancer center. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(8):2427-2433.

9. Swigart SE, Kishi Y, Thurber S, et al. Misdiagnosed delirium in patient referrals to a university-based hospital psychiatry department. Psychosomatics. 2008;49(2):104-108.

10. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST Jr, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(9):669-676.

11. Dasgupta M, Hillier LM. Factors associated with prolonged delirium: a systematic review. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(3):373-394.

12. Detweiler MB, Kenneth A, Bader G, et al. Can improved intra- and inter-team communication reduce missed delirium? Psychiatr Q. 2014;85(2):211-224.

CASE Confusion, hallucinations

Mr. G, age 57, is brought to the emergency department (ED) from a hospice care facility for worsening agitation and psychosis over 2 days. His wife, who accompanies him, describes a 2-month onset of “confusion” with occasional visual hallucinations. She says that at baseline Mr. G was alert and oriented and able to engage appropriately in conversations. The hospice facility administered emergency medications, including unknown dosages of haloperidol and chlorpromazine, the morning before transfer to the ED.

Mr. G has a history of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, and depression that has been managed for 6 years with several trials of antidepressant monotherapy, including fluoxetine, citalopram, mirtazapine, bupropion, and augmentation using aripiprazole, risperidone, topiramate, and zolpidem. At the time of this hospital presentation, his symptoms are controlled on clonazepam, 2 mg/d, and trazodone, 50 mg/d. For his pain attributed to non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), he receives methadone, 25 mg, 6 times a day, and hydromorphone, 8 mg, every 4 hours as needed, for breakthrough pain. Mr. G underwent a right upper lobectomy 5 years ago and neurosurgery with a right suboccipital craniectomy for right-sided cerebellar metastatic tumor measuring 2 × 1 × 0.6 cm, along with chemotherapy and radiation for metastasis in the brain 1 year ago. His last chemotherapy session was 3 months ago.

In the ED, Mr. G is sedated and oriented only to person and his wife. He is observed mumbling incoherently. Abnormal vital signs and laboratory findings are elevated pulse, 97 beats per minute; mild anemia, 13.5 g/dL hemoglobin and 40.8% hematocrit; an elevated glucose of 136 mg/dL; and small amounts of blood, trace ketones, and hyaline casts in urinalysis. Vital signs, laboratory resu

In addition to psychotropic and pain medication, Mr. G is taking cyclobenzaprine, 5 mg, every 6 hours as needed, for muscle spasms; docusate, 200 mg/d; enoxaparin, 100 mg/1mL, every 12 hours; folic acid, 1 mg/d; gabapentin, 600 mg, 3 times daily; lidocaine ointment, twice daily as needed, for pain; omeprazole, 80 mg/d; ondansetron, 4 mg, every 8 hours as needed, for nausea; and tamsulosin, 0.4 mg/d.

What is your differential diagnosis for Mr. G?

a) brain metastases

b) infection

c) PTSD

d) polypharmacy

e) benzodiazepine withdrawal

The authors’ observations

Altered mental status (AMS), or acute confusional state, describes an individual who fails to interact with environmental stimuli in an appropriate, anticipated manner. The disturbance usually is acute and transient.1 Often providers struggle to obtain relevant facts about a patient’s history of illness and must use laboratory and diagnostic data to determine the underlying cause of the patient’s disorientation.

Mental status includes 2 components: arousal and awareness. Arousal refers to a person’s wakeful state and how an individual responds to his (her) surroundings. Impairment in arousal can result in variable states including lethargy, drowsiness, and even coma. Awareness, on the other hand, is an individual’s perception of his environment, including orientation to surroundings, executive functioning, and memory. Although arousal level is controlled by the reticular activating system of the brainstem, awareness of consciousness is mediated at the cortical level. Mr. G experienced increased arousal and AMS with a clear change in behavior from his baseline. With increasing frequency of hallucinations and agitated behaviors, several tests must be ordered to determine the etiology of his altered mentation (Table 1).

Which test would you order next?

a) urine drug screen (UDS)

b) chest CT with pulmonary embolism protocol

c) CT of the head

d) blood cultures

e) chest radiography

EVALUATION Awake, still confused

The ED physician orders a UDS, non-contrasted CT of the head, and chest radiography for preliminary workup investigating the cause of Mr. G’s AMS. UDS is negative for illicit substances. The non-contrasted CT of the head shows a stable, right cerebellar hemisphere lesion from a prior lung metastasis. Mr. G’s chest radiography reading describes an ill-defined opacity at the left lung base.

Mr. G is admitted to the medical service and is started on dexamethasone, 8 mg/d, for his NSCLC with brain metastasis. Clonazepam is continued to prevent benzodiazepine withdrawal. The psychiatry and palliative care teams are consulted to determine if Mr. G’s PTSD symptoms and/or opioids are contributing to his AMS and psychosis. After evaluation, the psychiatry team recommends decreasing clonazepam to 0.5 mg, twice daily, starting olanzapine, 5 mg, every 12 hours, for agitation and psychosis involving auditory and visual hallucinations as well as paranoid themes related to food contamination, and using non-pharmacologic interventions for delirium treatment (Table 2). In a prospective, randomized controlled trial of olanzapine vs haloperidol, clinical improvement in delirious states was seen in individuals who received either antipsychotic medication; however, haloperidol was associated with extrapyramidal side effects. Therefore, olanzapine is a safe alternative to haloperidol in delirious patients.2