User login

Depression is a common condition that significantly impairs social and occupational functioning. Many patients do not respond to first-line pharmacotherapies and are considered to have treatment-resistant depression (TRD). These patients may benefit from augmentation of their antidepressant to reduce depression. Multiple medications have demonstrated various degrees of efficacy for augmentation, including psychostimulants. This article reviews studies of psychostimulants as augmentation agents for TRD and discusses risks, offers advice, and makes recommendations for clinicians who prescribe stimulants.

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychiatric condition that significantly impairs quality of life.1 It is a recurrent illness, averaging 2 relapses per decade. The probability of recurrence increases with the number of depressive episodes.2,3 A patient who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with euthymia has unipolar depression; whereas one who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with episodes of mania or hypomania has bipolar depression.4

Despite adequate dose and duration of pharmacotherapy, many individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression do not achieve and sustain remission.5 Remission rates decrease and relapse rates increase with subsequent failed antidepressant trials.6 It is difficult to identify factors that predict treatment resistance, but one review of antidepressant studies found that patients who did not demonstrate a response within 3 weeks of medication initiation were less likely to respond after a longer duration.7

Treatment-resistant depression is commonly, but not universally, defined as lack of response after trials of 2 or more antidepressants with different mechanisms of action for sufficient duration.5 This definition will be used here as well. Other definitions have proposed stages of TRD, but these require further study to evaluate their reliability and predictive utility.8 Due to lack of consensus regarding the definition of TRD, it is not possible to determine the exact prevalence of TRD.

Patients with TRD may benefit from augmentation of their medication regimen. Augmentation with lithium has yielded conflicting results, and its efficacy with newer antidepressants is not well studied.9-12 Triiodothyronine, buspirone, and pindolol have demonstrated some efficacy when added to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).10,12,13 Second-generation antipsychotic drugs, antidepressant drug combinations, omega-3 fatty acids, S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), and L-methylfolate have demonstrated some efficacy in some studies as well.12,14-23 In patients with depression who have not responded to these strategies, psychostimulant augmentation may be appropriate.

Methods

A literature search was conducted following an algorithmic approach in the MEDLINE/PubMed database for studies in English from January 1985 to August 2014 of stimulants as augmenting agents for depression, using the Medical Subject Headings stimulant, depression, and augmentation, combined with an AND operator. The search was limited to adult humans and excluded case reports and letters, to identify studies with stronger evidence. Also excluded were studies using caffeine (to augment electroconvulsive therapy for depression) and pemoline as the sole augmenting stimulant as well as studies of patients with comorbid mental health diagnoses and studies that initiated stimulants and antidepressants simultaneously to assess antidepressant response.

This review organized results by stimulant rather than by depression type, even though some studies used > 1 stimulant or recruited patients with different types of depression. Although prevalence, prognosis, and monotherapy differ for unipolar and bipolar depression, psychostimulants target similar symptoms, despite augmenting different monotherapies in unipolar and bipolar depression. Therefore, no distinction is made between assessing studies of stimulants for unipolar and bipolar depression.

Results

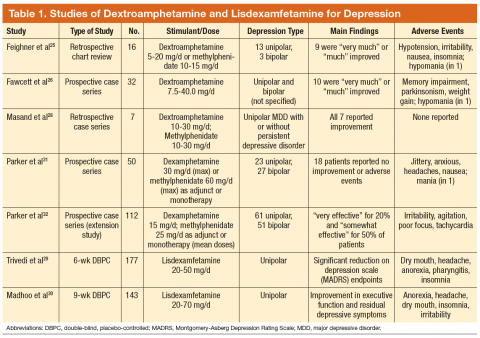

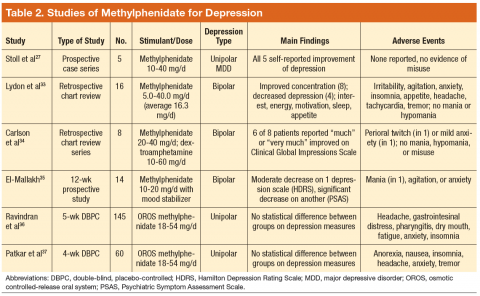

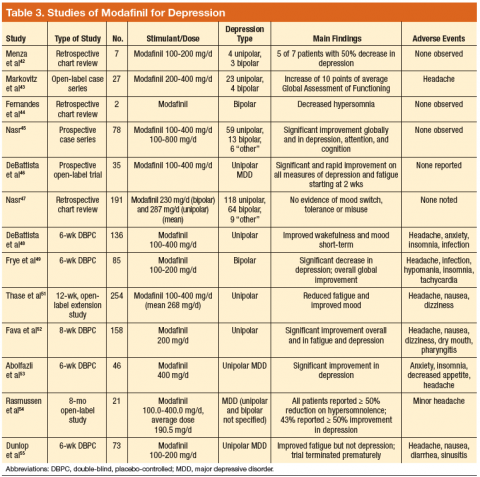

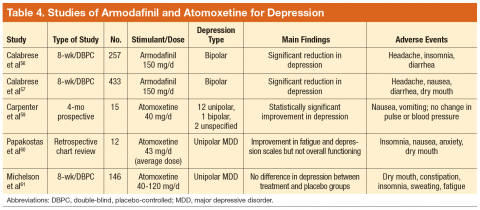

A total of 70 articles were identified, and 31 studies met inclusion criteria (Figure). Of the studies included, 12 were double-blind, placebo-controlled (DBPC) trials and 19 were retrospective chart reviews or open studies. Most studies evaluated depression, using validated scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, Carroll Depression Rating Scale, Global Assessment of Functioning, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, or the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. Study details are provided in Tables 1 to 4.

Dextroamphetamine and Methylphenidate

Dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate are indicated for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and exert their effects by inhibiting uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine.24 In one chart review, patients received dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) alone or with concurrent tricyclic antidepressants; the majority reported decreased depression.25 In an openlabel trial, dextroamphetamine was titrated to efficacy in patients who were receiving an MAOI with or without pemoline.26 Nearly 80% of patients reported long-lasting improvement in depression. In an open-label trial, all patients reported decreased depression when methylphenidate was added to SRIs; however, no scales were used.27

In a case series, patients with both major depression and persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) experienced a substantial, quick, and sustained response to dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation.28 Addition of lisdexamfetamine significantly reduced depressive symptoms in individuals with inadequate response to escitalopram.29 Patients with full or partial remission of depression noted improved executive function and residual depressive symptoms after lisdexamfetamine was added to SRI monotherapy.30 In a trial in which patients received dexamphetamine or methylphenidate as monotherapy or augmentation, 30% to 34% of patients reported mood improvement, but 36% reported no improvement.31 In an extension study, low-dose psychostimulants quickly diminished melancholia.32

Methylphenidate was safe and effective in patients with bipolar depression receiving treatment for 1 to 5 years; 44% evidenced significant improvement.33 When offered to patients with bipolar depression, patients receiving methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine reported less depression or sedation and did not develop tolerance, mania, or misuse.34 A case series concluded that methylphenidate addition to mood stabilizers was generally effective and safe.35

However, not all preparations of methylphenidate have demonstrated efficacy. In one study, osmotic controlledrelease oral system (OROS) methylphenidate improved apathy and fatigue but not overall depression.36 Although OROS methylphenidate similarly failed to demonstrate statistically significant efficacy in another study, more responders were documented in the treatment group.37

Although this review focuses on stimulants as augmenting agents in patients with depression, it is worth noting the limited number of studies evaluating stimulants’ effect on depression in patients with traumatic brain injury. This observation is of concern, as these conditions are frequently comorbid in returning veterans. One study noted that methylphenidate was an effective monotherapy for depression; whereas another study found that methylphenidate monotherapy reduced depression as well as sertraline, was better tolerated, and improved fatigue and cognition.38,39

Modafinil and Armodafinil

Modafinil and armodafinil (the R-enantiomer of modafinil) are indicated for improving wakefulness in individuals with narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder by modulating glutamate, gamma amino-butyric acid, and histamine.40,41 Although they increase extracellular dopamine concentrations, they do not cause an increase in dopamine release and may have less misuse potential than that of dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate.40,41 In a study of 7 patients with unipolar or bipolar depression, all patients achieved full or partial remission with minimal adverse effects (AEs).42 In a prospective study, 41% of patients reported only mild depression or full remission with modafinil augmentation.43

Multiple trials and a pooled analysis noted decreased depression and fatigue and improved cognition in patients receiving modafinil augmentation compared with mood stabilizers or antidepressants.44-49 Modafinil is a useful adjunct for partial responders to SRIs, resulting in rapid mood improvement and decreased fatigue.50-54 However, in one study, modafinil did not demonstrate efficacy compared with placebo. This result was attributed to premature study termination after 2 modafinil-treated patients developed suicidal ideation.55 A post hoc analysis found no difference in frequency of suicidal ideation between groups.

Two DBPC studies evaluated armodafinil in patients with bipolar depression. In both studies it was added to a mood-stabilizing agent (lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, olanzapine, lamotrigine, risperidone, or ziprasidone), and patients receiving armodafinil reported significant reductions

in depression.56,57

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor indicated for the treatment of ADHD and is considered to have no misuse potential due to lack of dopamine modulation.58 In one study, 15 patients received atomoxetine added to their antidepressant, and 60% experienced significant symptom reduction.59 A chart review noted decreases in fatigue and depression when atomoxetine was added to an SRI, mirtazapine, or amitriptyline.60 However, in a DBPC trial, atomoxetine did not lead to significant changes in depression.61

Discussion

There is a limited amount of high-quality evidence to support psychostimulant augmentation, as noted by the relatively few DBPC trials, most of short duration. The evidence supports their efficacy primarily for unipolar depression, as 14 studies evaluated patients with unipolar depression, whereas only 7 studies evaluated patients with bipolar depression. The remaining studies recruited patients with both depression types. Collectively, modafinil and armodafinil have the most evidence in DBPC trials.

There are relatively few DBPC trials with high power and sufficient duration for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate preparations. This discovery is surprising, considering the duration that these medications have been available. However, several chart reviews and open-label trials provided some evidence to support their use in patients without a history of substance misuse or cardiac conditions.62 Osmotic controlled- release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective, and the efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation

is uncertain.

Precautions

Prescribing physicians who offer stimulants should consider potential AEs, such as psychosis, anorexia, anxiety, insomnia, mood changes (eg, anger), misuse, addiction, mania, and cardiovascular problems. Psychostimulants have been implicated in precipitating psychosis.63,64 However, in a 12-month study of 250 adults with ADHD, 73 reported AEs, and only 31 discontinued the stimulant. Adverse effects leading to discontinuation included mood instability (n = 7), agitation (n = 6), irritability (n = 4), or decreased appetite (n = 4).65

Although associated with the risks of anorexia and insomnia in patients with ADHD, methylphenidate rapidly improved daytime sleepiness and mood, and—paradoxically—appetite and nighttime sleep in medically ill elderly patients with depression.66 Misuse or abuse of methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine were noted in 23% of patients referred for substance misuse.67 Nonetheless, little evidence exists that these drugs possess significant misuse potential in patients taking them as prescribed. As a prodrug, lisdexamfetamine is hypothesized to have less abuse potential compared with dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, but it carries the same prescribing and monitoring precautions.68 Risks related to stimulant usage extend to manic symptoms.69 Patients with bipolar disorder should not receive stimulants if they have a history of stimulant-induced mania, rapid cycling, or psychosis.70

Long-term cardiovascular safety data exist for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate but are limited or unavailable for modafinil, armodafinil, and atomoxetine. A retrospective cohort study found no significant increase in the number of cardiac events in patients receiving dextroamphetamine,

methylphenidate, or atomoxetine for an average of 1 year compared with controls.71 Another cohort study of > 44,000 patients found that initiation of

methylphenidate was associated with increased risk of sudden death or arrhythmia, but the risk was attributed to an unmeasured confounding factor, as the authors found a negative correlation between methylphenidate dose and all cardiovascular events.72

Recent practice guidelines recommend that before prescribing stimulants, clinicians should perform a physical examination (including heart and lung auscultation), obtain vital signs and height and weight, and request an electrocardiogram in case of abnormal findings on a cardiovascular examination or in case of a personal or family history of heart disease. Before offering atomoxetine, clinicians should evaluate the patient for a history of liver disease (and check liver function studies in case of a positive history). Clinicians should also assess risk of self-harm prior to initiating psychostimulant therapy.73 Throughout treatment, clinicians should evaluate the patient for changes in blood pressure, pulse, weight or mood, as well as the development of dependence or misuse. Urine toxicology testing is recommended for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate to screen for adherence and diversion.

Limitations

Using only PubMed and MEDLINE databases limited the search to articles published in English after 1985, excluding letters and case reports to identify studies with higher evidence (the studies were not weighted based on study design). In addition, the studies had certain limitations. These include a limited number of DBPC trials, most were of short duration. It is also difficult to compare studies due to various rating scales used and concurrent

medication regimens of study subjects. These limitations raise questions surrounding the long-term efficacy of stimulants, and there is no consensus for how long a stimulant should be continued if beneficial. Longer, higherpowered, DBPC trials are warranted to determine longterm efficacy and safety of stimulant augmentation.62

Conclusion

For patients with depression who have not responded to other augmentation strategies, psychostimulants may be offered to improve mood, energy, and concentration. For clinicians considering stimulant augmentation, modafinil and armodafinil are reasonable choices given their efficacy in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and lower risk of misuse. Dextroamphetamine (particularly lisdexamphetamine) and methylphenidate may be appropriate for patients who have not benefited from or tolerated modafinil or armodafinil, provided these patients do not have a medical history of cardiac disease or current substance use.

Osmotic controlled-release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective as an augmenting agent. The efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation is questionable, but atomoxetine could be offered if other stimulants were contraindicated, ineffective, or poorly tolerated. Both OROS methylphenidate and atomoxetine should be evaluated in additional trials before they can be recommended as augmentation therapies. Certain psychostimulants may be appropriate and reasonable adjunctive pharmacotherapies for patients with unipolar or bipolar depression who have failed other augmentation strategies, for patients who have significant fatigue or cognitive complaints, or for elderly patients with melancholic or somatic features of depression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maureen Humphrey-Shelton and Kathy Thomas for their help in obtaining references.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229-233.

3. Katon WJ, Fan MY, Lin EH, Unützer J. Depressive symptom deterioration in a large

primary care-based elderly cohort. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):246-254.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. McIntyre RS, Filteau M-J, Martin L, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: Definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7.

6. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Rush AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Focus. 2012;10(4):510-517.

7. Kudlow PA, Cha DS, McIntyre RS. Predicting treatment response in major depressive disorder: The impact of early symptomatic improvement. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(12):782-788.

8. Ruhé HG, van Rooijen G, Spijker J, Peeters FP, Schene AH. Staging methods for treatment resistant depression. A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;137(1-3):35-45.

9. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation treatment-resistant depression: Metaanalysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

10. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530.

11. Nierenberg AA, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Lithium augmentation of nortriptyline

for subjects resistant to multiple antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(1):92-95.

12. Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you don’t succeed: A review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination, and switching strategies. Drugs. 2011;71(1):43-64.

13. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

14. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, Fava M. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment resistant major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):826-831.

15. Mahmoud RA, Pandina GJ, Turkoz I, et al. Risperidone for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):593-602.

16. Barbee JG, Conrad EJ, Jamhour NJ. The effectiveness of olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone as augmentation agents in treatment resistant depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):975-981.

17. Fatemi SH, Emamian ES, Kist DA. Venlafaxine and bupropion combination therapy in a case of treatment-resistant depression. Ann Pharmacother.1999;33(6):701-703.

18. Carpenter LL, Yasman S, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(2):183-188.

19. Hannan N, Hamzah Z, Akinpeloye HO, Meagher D. Venlafaxine-mirtazapine combination therapy in the treatment of persistent depressive illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(2):161-164.

20. McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1531-1541.

21. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hébert C, Bergeron R. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: A double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

22. Papakostas GI, Mischoulon D, Shyu I, Alpert JE, Fava M. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):942-948.

23. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy

for SSRI-resistant major depression: Results of two randomized, double-blind,

parallel-sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

24. Korston TR. Drugs of abuse. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:521-523.

25. Feighner JP, Herbstein J, Damlouji N. Combined MAOI, TCA, and direct stimulant therapy of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(6):206-209.

26. Fawcett J, Kravitz HM, Zajecka JM, Schaff MR. CNS stimulant potentiation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;11(2):127-132.

27. Stoll AL, Pillay SS, Diamond L, Workum SB, Cole JO. Methylphenidate augmentation of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors: A case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(2):72-76.

28. Masand PS, Anand VS, Tanquary JF. Psychostimulant augmentation of second generation antidepressants: A case series. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7(2):89-91.

29. Trivedi MH, Cutler AJ, Richards C, et al. A randomized control trial of the efficacy and safety of lisdesxamfetamine dimesylate as augmentation therapy in adults with residual symptoms of major depressive disorder after treatment with escitalopram. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):802-809.

30. Madhoo M, Keefe RS, Roth RM, et al. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate augmentation in adults with persistent executive dysfunction after partial or full remission of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(6):1388-1398.

31. Parker G, Brotchie H. Do the old psychostimulant drugs have a role in managing treatment-resistant depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(4):308-314.

32. Parker G, Brotchie H, McClure G, Fletcher K. Psychostimulants for managing unipolar and bipolar treatment-resistant melancholic depression: A medium term evaluation of cost benefits. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):360-364.

33. Lydon E, El-Mallakh RS. Naturalistic long-term use of methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(5):516-518.

34. Carlson PJ, Merlock MC, Suppes T. Adjunctive stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder: Treatment of residual depression and sedation. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):416-420.

35. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(1):56-59.

36. Ravindran AV, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan MC, Fallu A, Camacho F, Binder CE. Osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate augmentation of antidepressant monotherapy in major depressive disorder: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):87-94.

37. Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled

trial of augmentation with an extended release formulation of methylphenidate in outpatients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):653-656.

38. Lee H, Kim SW, Kim JM, Shin IS, Yang SJ, Yoon JS Comparing effects of methylphenidate, sertraline, and placebo on neuropsychiatric sequelae in patients with

traumatic brain injury. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(2):97-104.

39. Gualtieri CT, Evans RW. Stimulant treatment for the neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1988;2(4):273-290.

40. Provigil [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Cephalon Inc; 2015.

41. Nuvigil [package insert]. Frazer, PA: Cephalon, Inc; 2013.

42. Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(5):378-381.

43. Markovitz PJ, Wagner S. An open-label trial of modafinil augmentation in patients with partial response to antidepressant therapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(2):207-209.

44. Fernandes PP, Petty F. Modafinil for remitted bipolar depression with hypersomnia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(12):1807-1809.

45. Nasr S. Modafinil as adjunctive therapy in depressed outpatients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):133-138.

46. DeBattista C, Lembke A, Solvason HB, Ghebremichael R, Poirier J. A prospective trial of modafinil as an adjunctive treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(1):87-90.

47. Nasr S, Wendt B, Steiner K. Absence of mood switch with and tolerance to modafinil: A replication study from a large private practice. J Affect Disord. 2006;95(1-3):111-114.

48. DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Menza MA, Rosenthal MH, Fieve RR; Modafinil in Depression Study Group. Adjunct modafinil for the short-term treatment of fatigue and sleepiness in patients with major depressive disorder: A preliminary doubleblind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1057-1064.

49. Frye MA, Grunze H, Suppes T, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of adjunctive modafinil in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1242-1249.

50. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Arora S, Hughes RJ. Modafinil augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy in MDD partial responders with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(3):153-159.

51. Thase ME, Fava M, DeBattista C, Arora S, Hughes RJ. Modafinil augmentation of SSRI therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and excessive sleepiness and fatigue: A 12-week, open-label, extension study. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(2):93-102.

52. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):85-93.

53. Abolfazli R, Hosseini M, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Double-blind randomized parallelgroup clinical trial of efficacy of the combination fluoxetine plus modafinil versus fluoxetine plus placebo in the treatment of major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(4):297-302.

54. Rasmussen NA, Schrøder P, Olsen LR, Brødsgaard M, Undén M, Bech P. Modafinil augmentation in depressed patients with partial response to antidepressants: A pilot study on self-reported symptoms covered by the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) and the Symptom Checklist (SCL-92). Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(3):173-178.

55. Dunlop BW, Crits-Christoph P, Evans DL, et al. Coadministration of modafinil and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor from the initiation of treatment of major depressive disorder with fatigue and sleepiness: A double-blind, placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):614-619.

56. Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Youakim JM, Tiller JM, Yang R, Frye MA. Adjunctive armodafinil

for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: A randomized multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1363-1370.

57. Calabrese JR, Frye MA, Yang R, Ketter TA; Armodafinil Treatment Trial Study Network. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive armodafinil in adults with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):1054-1061.

58. Strattera [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN. Lilly; 2015.

59. Carpenter LL, Milosavljevic N, Schecter JM, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Augmentation with open-label atomoxetine for partial or nonresponse to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1234-1238.

60. Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Burns AM, Fava M. Adjunctive atomoxetine for residual

fatigue in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):370-373.

61. Michelson D, Adler LA, Amsterdam JD, et al. Addition of atomoxetine for depression

incompletely responsive to sertraline: A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(4):582-587.

62. Corp SA, Gitlin MJ, Altshuler LL. A review of the use of stimulants and stimulant alternatives in treating bipolar depression and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(9):1010-1018.

63. Kraemer M, Uekermann J, Wiltfang J, Kis B. Methylphenidate-induced psychosis in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Report of 3 new cases and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(4):204-206.

64. Berman SM, Kuczenski R, McCracken JT, London ED. Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: A review. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(2):123-142.

65. Fredriksen M, Dahl AA, Martinsen EW, Klungsøyr O, Haavik J, Peleikis DE. Effectiveness of one-year pharmacological treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An open-label prospective study of time in treatment, dose, side-effects and comorbidity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(12):1873-1874.

66. Hardy SE. Methylphenidate for the treatment of depressive symptoms, including fatigue and apathy, in medically ill older adults and terminally ill adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7(1):34-59.

67. Williams RJ, Goodale LA, Shay-Fiddler MA, Gloster SP, Chang SY. Methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine abuse in substance-abusing adolescents. Am J Addict. 2004;13(4):381-389.

68. Madaan V, Kolli V, Bestha DP, Shah MJ. Update on optimal use of lisdexamfetamine in the treatment of ADHD. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:977-983.

69. Ross RG. Psychotic and manic-like symptoms during stimulant treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1149-1152.

70. Dell’Osso B, Ketter TA. Use of adjunctive stimulants in adult bipolar depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16(1):55-68.

71. Habel LA, Cooper WO, Sox CM, et al. ADHD medications and risk of serious cardiovascular events in young and middle-aged adults. JAMA. 2011;306(24):2673-2683.

72. Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Kimmel SE, et al. Methylphenidate and risk of serious cardiovascular events in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(2):178-185.

73. Bolea-Alamañac B, Nutt DJ, Adamou M, et al; British Association for Psychopharmacology. Evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological management of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Update on recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28(3):179-203.

74. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(6):e1000097.

Depression is a common condition that significantly impairs social and occupational functioning. Many patients do not respond to first-line pharmacotherapies and are considered to have treatment-resistant depression (TRD). These patients may benefit from augmentation of their antidepressant to reduce depression. Multiple medications have demonstrated various degrees of efficacy for augmentation, including psychostimulants. This article reviews studies of psychostimulants as augmentation agents for TRD and discusses risks, offers advice, and makes recommendations for clinicians who prescribe stimulants.

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychiatric condition that significantly impairs quality of life.1 It is a recurrent illness, averaging 2 relapses per decade. The probability of recurrence increases with the number of depressive episodes.2,3 A patient who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with euthymia has unipolar depression; whereas one who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with episodes of mania or hypomania has bipolar depression.4

Despite adequate dose and duration of pharmacotherapy, many individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression do not achieve and sustain remission.5 Remission rates decrease and relapse rates increase with subsequent failed antidepressant trials.6 It is difficult to identify factors that predict treatment resistance, but one review of antidepressant studies found that patients who did not demonstrate a response within 3 weeks of medication initiation were less likely to respond after a longer duration.7

Treatment-resistant depression is commonly, but not universally, defined as lack of response after trials of 2 or more antidepressants with different mechanisms of action for sufficient duration.5 This definition will be used here as well. Other definitions have proposed stages of TRD, but these require further study to evaluate their reliability and predictive utility.8 Due to lack of consensus regarding the definition of TRD, it is not possible to determine the exact prevalence of TRD.

Patients with TRD may benefit from augmentation of their medication regimen. Augmentation with lithium has yielded conflicting results, and its efficacy with newer antidepressants is not well studied.9-12 Triiodothyronine, buspirone, and pindolol have demonstrated some efficacy when added to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).10,12,13 Second-generation antipsychotic drugs, antidepressant drug combinations, omega-3 fatty acids, S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), and L-methylfolate have demonstrated some efficacy in some studies as well.12,14-23 In patients with depression who have not responded to these strategies, psychostimulant augmentation may be appropriate.

Methods

A literature search was conducted following an algorithmic approach in the MEDLINE/PubMed database for studies in English from January 1985 to August 2014 of stimulants as augmenting agents for depression, using the Medical Subject Headings stimulant, depression, and augmentation, combined with an AND operator. The search was limited to adult humans and excluded case reports and letters, to identify studies with stronger evidence. Also excluded were studies using caffeine (to augment electroconvulsive therapy for depression) and pemoline as the sole augmenting stimulant as well as studies of patients with comorbid mental health diagnoses and studies that initiated stimulants and antidepressants simultaneously to assess antidepressant response.

This review organized results by stimulant rather than by depression type, even though some studies used > 1 stimulant or recruited patients with different types of depression. Although prevalence, prognosis, and monotherapy differ for unipolar and bipolar depression, psychostimulants target similar symptoms, despite augmenting different monotherapies in unipolar and bipolar depression. Therefore, no distinction is made between assessing studies of stimulants for unipolar and bipolar depression.

Results

A total of 70 articles were identified, and 31 studies met inclusion criteria (Figure). Of the studies included, 12 were double-blind, placebo-controlled (DBPC) trials and 19 were retrospective chart reviews or open studies. Most studies evaluated depression, using validated scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, Carroll Depression Rating Scale, Global Assessment of Functioning, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, or the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. Study details are provided in Tables 1 to 4.

Dextroamphetamine and Methylphenidate

Dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate are indicated for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and exert their effects by inhibiting uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine.24 In one chart review, patients received dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) alone or with concurrent tricyclic antidepressants; the majority reported decreased depression.25 In an openlabel trial, dextroamphetamine was titrated to efficacy in patients who were receiving an MAOI with or without pemoline.26 Nearly 80% of patients reported long-lasting improvement in depression. In an open-label trial, all patients reported decreased depression when methylphenidate was added to SRIs; however, no scales were used.27

In a case series, patients with both major depression and persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) experienced a substantial, quick, and sustained response to dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation.28 Addition of lisdexamfetamine significantly reduced depressive symptoms in individuals with inadequate response to escitalopram.29 Patients with full or partial remission of depression noted improved executive function and residual depressive symptoms after lisdexamfetamine was added to SRI monotherapy.30 In a trial in which patients received dexamphetamine or methylphenidate as monotherapy or augmentation, 30% to 34% of patients reported mood improvement, but 36% reported no improvement.31 In an extension study, low-dose psychostimulants quickly diminished melancholia.32

Methylphenidate was safe and effective in patients with bipolar depression receiving treatment for 1 to 5 years; 44% evidenced significant improvement.33 When offered to patients with bipolar depression, patients receiving methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine reported less depression or sedation and did not develop tolerance, mania, or misuse.34 A case series concluded that methylphenidate addition to mood stabilizers was generally effective and safe.35

However, not all preparations of methylphenidate have demonstrated efficacy. In one study, osmotic controlledrelease oral system (OROS) methylphenidate improved apathy and fatigue but not overall depression.36 Although OROS methylphenidate similarly failed to demonstrate statistically significant efficacy in another study, more responders were documented in the treatment group.37

Although this review focuses on stimulants as augmenting agents in patients with depression, it is worth noting the limited number of studies evaluating stimulants’ effect on depression in patients with traumatic brain injury. This observation is of concern, as these conditions are frequently comorbid in returning veterans. One study noted that methylphenidate was an effective monotherapy for depression; whereas another study found that methylphenidate monotherapy reduced depression as well as sertraline, was better tolerated, and improved fatigue and cognition.38,39

Modafinil and Armodafinil

Modafinil and armodafinil (the R-enantiomer of modafinil) are indicated for improving wakefulness in individuals with narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder by modulating glutamate, gamma amino-butyric acid, and histamine.40,41 Although they increase extracellular dopamine concentrations, they do not cause an increase in dopamine release and may have less misuse potential than that of dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate.40,41 In a study of 7 patients with unipolar or bipolar depression, all patients achieved full or partial remission with minimal adverse effects (AEs).42 In a prospective study, 41% of patients reported only mild depression or full remission with modafinil augmentation.43

Multiple trials and a pooled analysis noted decreased depression and fatigue and improved cognition in patients receiving modafinil augmentation compared with mood stabilizers or antidepressants.44-49 Modafinil is a useful adjunct for partial responders to SRIs, resulting in rapid mood improvement and decreased fatigue.50-54 However, in one study, modafinil did not demonstrate efficacy compared with placebo. This result was attributed to premature study termination after 2 modafinil-treated patients developed suicidal ideation.55 A post hoc analysis found no difference in frequency of suicidal ideation between groups.

Two DBPC studies evaluated armodafinil in patients with bipolar depression. In both studies it was added to a mood-stabilizing agent (lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, olanzapine, lamotrigine, risperidone, or ziprasidone), and patients receiving armodafinil reported significant reductions

in depression.56,57

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor indicated for the treatment of ADHD and is considered to have no misuse potential due to lack of dopamine modulation.58 In one study, 15 patients received atomoxetine added to their antidepressant, and 60% experienced significant symptom reduction.59 A chart review noted decreases in fatigue and depression when atomoxetine was added to an SRI, mirtazapine, or amitriptyline.60 However, in a DBPC trial, atomoxetine did not lead to significant changes in depression.61

Discussion

There is a limited amount of high-quality evidence to support psychostimulant augmentation, as noted by the relatively few DBPC trials, most of short duration. The evidence supports their efficacy primarily for unipolar depression, as 14 studies evaluated patients with unipolar depression, whereas only 7 studies evaluated patients with bipolar depression. The remaining studies recruited patients with both depression types. Collectively, modafinil and armodafinil have the most evidence in DBPC trials.

There are relatively few DBPC trials with high power and sufficient duration for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate preparations. This discovery is surprising, considering the duration that these medications have been available. However, several chart reviews and open-label trials provided some evidence to support their use in patients without a history of substance misuse or cardiac conditions.62 Osmotic controlled- release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective, and the efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation

is uncertain.

Precautions

Prescribing physicians who offer stimulants should consider potential AEs, such as psychosis, anorexia, anxiety, insomnia, mood changes (eg, anger), misuse, addiction, mania, and cardiovascular problems. Psychostimulants have been implicated in precipitating psychosis.63,64 However, in a 12-month study of 250 adults with ADHD, 73 reported AEs, and only 31 discontinued the stimulant. Adverse effects leading to discontinuation included mood instability (n = 7), agitation (n = 6), irritability (n = 4), or decreased appetite (n = 4).65

Although associated with the risks of anorexia and insomnia in patients with ADHD, methylphenidate rapidly improved daytime sleepiness and mood, and—paradoxically—appetite and nighttime sleep in medically ill elderly patients with depression.66 Misuse or abuse of methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine were noted in 23% of patients referred for substance misuse.67 Nonetheless, little evidence exists that these drugs possess significant misuse potential in patients taking them as prescribed. As a prodrug, lisdexamfetamine is hypothesized to have less abuse potential compared with dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, but it carries the same prescribing and monitoring precautions.68 Risks related to stimulant usage extend to manic symptoms.69 Patients with bipolar disorder should not receive stimulants if they have a history of stimulant-induced mania, rapid cycling, or psychosis.70

Long-term cardiovascular safety data exist for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate but are limited or unavailable for modafinil, armodafinil, and atomoxetine. A retrospective cohort study found no significant increase in the number of cardiac events in patients receiving dextroamphetamine,

methylphenidate, or atomoxetine for an average of 1 year compared with controls.71 Another cohort study of > 44,000 patients found that initiation of

methylphenidate was associated with increased risk of sudden death or arrhythmia, but the risk was attributed to an unmeasured confounding factor, as the authors found a negative correlation between methylphenidate dose and all cardiovascular events.72

Recent practice guidelines recommend that before prescribing stimulants, clinicians should perform a physical examination (including heart and lung auscultation), obtain vital signs and height and weight, and request an electrocardiogram in case of abnormal findings on a cardiovascular examination or in case of a personal or family history of heart disease. Before offering atomoxetine, clinicians should evaluate the patient for a history of liver disease (and check liver function studies in case of a positive history). Clinicians should also assess risk of self-harm prior to initiating psychostimulant therapy.73 Throughout treatment, clinicians should evaluate the patient for changes in blood pressure, pulse, weight or mood, as well as the development of dependence or misuse. Urine toxicology testing is recommended for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate to screen for adherence and diversion.

Limitations

Using only PubMed and MEDLINE databases limited the search to articles published in English after 1985, excluding letters and case reports to identify studies with higher evidence (the studies were not weighted based on study design). In addition, the studies had certain limitations. These include a limited number of DBPC trials, most were of short duration. It is also difficult to compare studies due to various rating scales used and concurrent

medication regimens of study subjects. These limitations raise questions surrounding the long-term efficacy of stimulants, and there is no consensus for how long a stimulant should be continued if beneficial. Longer, higherpowered, DBPC trials are warranted to determine longterm efficacy and safety of stimulant augmentation.62

Conclusion

For patients with depression who have not responded to other augmentation strategies, psychostimulants may be offered to improve mood, energy, and concentration. For clinicians considering stimulant augmentation, modafinil and armodafinil are reasonable choices given their efficacy in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and lower risk of misuse. Dextroamphetamine (particularly lisdexamphetamine) and methylphenidate may be appropriate for patients who have not benefited from or tolerated modafinil or armodafinil, provided these patients do not have a medical history of cardiac disease or current substance use.

Osmotic controlled-release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective as an augmenting agent. The efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation is questionable, but atomoxetine could be offered if other stimulants were contraindicated, ineffective, or poorly tolerated. Both OROS methylphenidate and atomoxetine should be evaluated in additional trials before they can be recommended as augmentation therapies. Certain psychostimulants may be appropriate and reasonable adjunctive pharmacotherapies for patients with unipolar or bipolar depression who have failed other augmentation strategies, for patients who have significant fatigue or cognitive complaints, or for elderly patients with melancholic or somatic features of depression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maureen Humphrey-Shelton and Kathy Thomas for their help in obtaining references.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Depression is a common condition that significantly impairs social and occupational functioning. Many patients do not respond to first-line pharmacotherapies and are considered to have treatment-resistant depression (TRD). These patients may benefit from augmentation of their antidepressant to reduce depression. Multiple medications have demonstrated various degrees of efficacy for augmentation, including psychostimulants. This article reviews studies of psychostimulants as augmentation agents for TRD and discusses risks, offers advice, and makes recommendations for clinicians who prescribe stimulants.

Background

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a common psychiatric condition that significantly impairs quality of life.1 It is a recurrent illness, averaging 2 relapses per decade. The probability of recurrence increases with the number of depressive episodes.2,3 A patient who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with euthymia has unipolar depression; whereas one who experiences major depressive episodes alternating with episodes of mania or hypomania has bipolar depression.4

Despite adequate dose and duration of pharmacotherapy, many individuals with unipolar or bipolar depression do not achieve and sustain remission.5 Remission rates decrease and relapse rates increase with subsequent failed antidepressant trials.6 It is difficult to identify factors that predict treatment resistance, but one review of antidepressant studies found that patients who did not demonstrate a response within 3 weeks of medication initiation were less likely to respond after a longer duration.7

Treatment-resistant depression is commonly, but not universally, defined as lack of response after trials of 2 or more antidepressants with different mechanisms of action for sufficient duration.5 This definition will be used here as well. Other definitions have proposed stages of TRD, but these require further study to evaluate their reliability and predictive utility.8 Due to lack of consensus regarding the definition of TRD, it is not possible to determine the exact prevalence of TRD.

Patients with TRD may benefit from augmentation of their medication regimen. Augmentation with lithium has yielded conflicting results, and its efficacy with newer antidepressants is not well studied.9-12 Triiodothyronine, buspirone, and pindolol have demonstrated some efficacy when added to serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs).10,12,13 Second-generation antipsychotic drugs, antidepressant drug combinations, omega-3 fatty acids, S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe), and L-methylfolate have demonstrated some efficacy in some studies as well.12,14-23 In patients with depression who have not responded to these strategies, psychostimulant augmentation may be appropriate.

Methods

A literature search was conducted following an algorithmic approach in the MEDLINE/PubMed database for studies in English from January 1985 to August 2014 of stimulants as augmenting agents for depression, using the Medical Subject Headings stimulant, depression, and augmentation, combined with an AND operator. The search was limited to adult humans and excluded case reports and letters, to identify studies with stronger evidence. Also excluded were studies using caffeine (to augment electroconvulsive therapy for depression) and pemoline as the sole augmenting stimulant as well as studies of patients with comorbid mental health diagnoses and studies that initiated stimulants and antidepressants simultaneously to assess antidepressant response.

This review organized results by stimulant rather than by depression type, even though some studies used > 1 stimulant or recruited patients with different types of depression. Although prevalence, prognosis, and monotherapy differ for unipolar and bipolar depression, psychostimulants target similar symptoms, despite augmenting different monotherapies in unipolar and bipolar depression. Therefore, no distinction is made between assessing studies of stimulants for unipolar and bipolar depression.

Results

A total of 70 articles were identified, and 31 studies met inclusion criteria (Figure). Of the studies included, 12 were double-blind, placebo-controlled (DBPC) trials and 19 were retrospective chart reviews or open studies. Most studies evaluated depression, using validated scales, such as the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale, Clinical Global Impressions of Severity, Inventory of Depressive Symptoms, Carroll Depression Rating Scale, Global Assessment of Functioning, Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology, or the Psychiatric Symptom Assessment Scale. Study details are provided in Tables 1 to 4.

Dextroamphetamine and Methylphenidate

Dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate are indicated for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and exert their effects by inhibiting uptake of norepinephrine and dopamine.24 In one chart review, patients received dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) alone or with concurrent tricyclic antidepressants; the majority reported decreased depression.25 In an openlabel trial, dextroamphetamine was titrated to efficacy in patients who were receiving an MAOI with or without pemoline.26 Nearly 80% of patients reported long-lasting improvement in depression. In an open-label trial, all patients reported decreased depression when methylphenidate was added to SRIs; however, no scales were used.27

In a case series, patients with both major depression and persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) experienced a substantial, quick, and sustained response to dextroamphetamine or methylphenidate augmentation.28 Addition of lisdexamfetamine significantly reduced depressive symptoms in individuals with inadequate response to escitalopram.29 Patients with full or partial remission of depression noted improved executive function and residual depressive symptoms after lisdexamfetamine was added to SRI monotherapy.30 In a trial in which patients received dexamphetamine or methylphenidate as monotherapy or augmentation, 30% to 34% of patients reported mood improvement, but 36% reported no improvement.31 In an extension study, low-dose psychostimulants quickly diminished melancholia.32

Methylphenidate was safe and effective in patients with bipolar depression receiving treatment for 1 to 5 years; 44% evidenced significant improvement.33 When offered to patients with bipolar depression, patients receiving methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine reported less depression or sedation and did not develop tolerance, mania, or misuse.34 A case series concluded that methylphenidate addition to mood stabilizers was generally effective and safe.35

However, not all preparations of methylphenidate have demonstrated efficacy. In one study, osmotic controlledrelease oral system (OROS) methylphenidate improved apathy and fatigue but not overall depression.36 Although OROS methylphenidate similarly failed to demonstrate statistically significant efficacy in another study, more responders were documented in the treatment group.37

Although this review focuses on stimulants as augmenting agents in patients with depression, it is worth noting the limited number of studies evaluating stimulants’ effect on depression in patients with traumatic brain injury. This observation is of concern, as these conditions are frequently comorbid in returning veterans. One study noted that methylphenidate was an effective monotherapy for depression; whereas another study found that methylphenidate monotherapy reduced depression as well as sertraline, was better tolerated, and improved fatigue and cognition.38,39

Modafinil and Armodafinil

Modafinil and armodafinil (the R-enantiomer of modafinil) are indicated for improving wakefulness in individuals with narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea, and shift work sleep disorder by modulating glutamate, gamma amino-butyric acid, and histamine.40,41 Although they increase extracellular dopamine concentrations, they do not cause an increase in dopamine release and may have less misuse potential than that of dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate.40,41 In a study of 7 patients with unipolar or bipolar depression, all patients achieved full or partial remission with minimal adverse effects (AEs).42 In a prospective study, 41% of patients reported only mild depression or full remission with modafinil augmentation.43

Multiple trials and a pooled analysis noted decreased depression and fatigue and improved cognition in patients receiving modafinil augmentation compared with mood stabilizers or antidepressants.44-49 Modafinil is a useful adjunct for partial responders to SRIs, resulting in rapid mood improvement and decreased fatigue.50-54 However, in one study, modafinil did not demonstrate efficacy compared with placebo. This result was attributed to premature study termination after 2 modafinil-treated patients developed suicidal ideation.55 A post hoc analysis found no difference in frequency of suicidal ideation between groups.

Two DBPC studies evaluated armodafinil in patients with bipolar depression. In both studies it was added to a mood-stabilizing agent (lithium, valproate, aripiprazole, olanzapine, lamotrigine, risperidone, or ziprasidone), and patients receiving armodafinil reported significant reductions

in depression.56,57

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor indicated for the treatment of ADHD and is considered to have no misuse potential due to lack of dopamine modulation.58 In one study, 15 patients received atomoxetine added to their antidepressant, and 60% experienced significant symptom reduction.59 A chart review noted decreases in fatigue and depression when atomoxetine was added to an SRI, mirtazapine, or amitriptyline.60 However, in a DBPC trial, atomoxetine did not lead to significant changes in depression.61

Discussion

There is a limited amount of high-quality evidence to support psychostimulant augmentation, as noted by the relatively few DBPC trials, most of short duration. The evidence supports their efficacy primarily for unipolar depression, as 14 studies evaluated patients with unipolar depression, whereas only 7 studies evaluated patients with bipolar depression. The remaining studies recruited patients with both depression types. Collectively, modafinil and armodafinil have the most evidence in DBPC trials.

There are relatively few DBPC trials with high power and sufficient duration for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate preparations. This discovery is surprising, considering the duration that these medications have been available. However, several chart reviews and open-label trials provided some evidence to support their use in patients without a history of substance misuse or cardiac conditions.62 Osmotic controlled- release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective, and the efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation

is uncertain.

Precautions

Prescribing physicians who offer stimulants should consider potential AEs, such as psychosis, anorexia, anxiety, insomnia, mood changes (eg, anger), misuse, addiction, mania, and cardiovascular problems. Psychostimulants have been implicated in precipitating psychosis.63,64 However, in a 12-month study of 250 adults with ADHD, 73 reported AEs, and only 31 discontinued the stimulant. Adverse effects leading to discontinuation included mood instability (n = 7), agitation (n = 6), irritability (n = 4), or decreased appetite (n = 4).65

Although associated with the risks of anorexia and insomnia in patients with ADHD, methylphenidate rapidly improved daytime sleepiness and mood, and—paradoxically—appetite and nighttime sleep in medically ill elderly patients with depression.66 Misuse or abuse of methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine were noted in 23% of patients referred for substance misuse.67 Nonetheless, little evidence exists that these drugs possess significant misuse potential in patients taking them as prescribed. As a prodrug, lisdexamfetamine is hypothesized to have less abuse potential compared with dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate, but it carries the same prescribing and monitoring precautions.68 Risks related to stimulant usage extend to manic symptoms.69 Patients with bipolar disorder should not receive stimulants if they have a history of stimulant-induced mania, rapid cycling, or psychosis.70

Long-term cardiovascular safety data exist for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate but are limited or unavailable for modafinil, armodafinil, and atomoxetine. A retrospective cohort study found no significant increase in the number of cardiac events in patients receiving dextroamphetamine,

methylphenidate, or atomoxetine for an average of 1 year compared with controls.71 Another cohort study of > 44,000 patients found that initiation of

methylphenidate was associated with increased risk of sudden death or arrhythmia, but the risk was attributed to an unmeasured confounding factor, as the authors found a negative correlation between methylphenidate dose and all cardiovascular events.72

Recent practice guidelines recommend that before prescribing stimulants, clinicians should perform a physical examination (including heart and lung auscultation), obtain vital signs and height and weight, and request an electrocardiogram in case of abnormal findings on a cardiovascular examination or in case of a personal or family history of heart disease. Before offering atomoxetine, clinicians should evaluate the patient for a history of liver disease (and check liver function studies in case of a positive history). Clinicians should also assess risk of self-harm prior to initiating psychostimulant therapy.73 Throughout treatment, clinicians should evaluate the patient for changes in blood pressure, pulse, weight or mood, as well as the development of dependence or misuse. Urine toxicology testing is recommended for dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate to screen for adherence and diversion.

Limitations

Using only PubMed and MEDLINE databases limited the search to articles published in English after 1985, excluding letters and case reports to identify studies with higher evidence (the studies were not weighted based on study design). In addition, the studies had certain limitations. These include a limited number of DBPC trials, most were of short duration. It is also difficult to compare studies due to various rating scales used and concurrent

medication regimens of study subjects. These limitations raise questions surrounding the long-term efficacy of stimulants, and there is no consensus for how long a stimulant should be continued if beneficial. Longer, higherpowered, DBPC trials are warranted to determine longterm efficacy and safety of stimulant augmentation.62

Conclusion

For patients with depression who have not responded to other augmentation strategies, psychostimulants may be offered to improve mood, energy, and concentration. For clinicians considering stimulant augmentation, modafinil and armodafinil are reasonable choices given their efficacy in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials and lower risk of misuse. Dextroamphetamine (particularly lisdexamphetamine) and methylphenidate may be appropriate for patients who have not benefited from or tolerated modafinil or armodafinil, provided these patients do not have a medical history of cardiac disease or current substance use.

Osmotic controlled-release oral system methylphenidate seems to be ineffective as an augmenting agent. The efficacy of atomoxetine for augmentation is questionable, but atomoxetine could be offered if other stimulants were contraindicated, ineffective, or poorly tolerated. Both OROS methylphenidate and atomoxetine should be evaluated in additional trials before they can be recommended as augmentation therapies. Certain psychostimulants may be appropriate and reasonable adjunctive pharmacotherapies for patients with unipolar or bipolar depression who have failed other augmentation strategies, for patients who have significant fatigue or cognitive complaints, or for elderly patients with melancholic or somatic features of depression.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Maureen Humphrey-Shelton and Kathy Thomas for their help in obtaining references.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distribution of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):593-602.

2. Solomon DA, Keller MB, Leon AC, et al. Multiple recurrences of major depressive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(2):229-233.

3. Katon WJ, Fan MY, Lin EH, Unützer J. Depressive symptom deterioration in a large

primary care-based elderly cohort. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14(3):246-254.

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. McIntyre RS, Filteau M-J, Martin L, et al. Treatment-resistant depression: Definitions, review of the evidence, and algorithmic approach. J Affect Disord. 2014;156:1-7.

6. Gaynes BN, Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, Rush AJ. What did STAR*D teach us? Results from a large-scale, practical, clinical trial for patients with depression. Focus. 2012;10(4):510-517.

7. Kudlow PA, Cha DS, McIntyre RS. Predicting treatment response in major depressive disorder: The impact of early symptomatic improvement. Can J Psychiatry. 2012;57(12):782-788.

8. Ruhé HG, van Rooijen G, Spijker J, Peeters FP, Schene AH. Staging methods for treatment resistant depression. A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2012;137(1-3):35-45.

9. Bauer M, Dopfmer S. Lithium augmentation treatment-resistant depression: Metaanalysis of placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):427-434.

10. Nierenberg AA, Fava M, Trivedi MH, et al. A comparison of lithium and T(3) augmentation following two failed medication treatments for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1519-1530.

11. Nierenberg AA, Papakostas GI, Petersen T, et al. Lithium augmentation of nortriptyline

for subjects resistant to multiple antidepressants. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(1):92-95.

12. Connolly KR, Thase ME. If at first you don’t succeed: A review of the evidence for antidepressant augmentation, combination, and switching strategies. Drugs. 2011;71(1):43-64.

13. Trivedi MH, Fava M, Wisniewski SR, et al; STAR*D Study Team. Medication augmentation after the failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1243-1252.

14. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Smith J, Fava M. Augmentation of antidepressants with atypical antipsychotic medications for treatment resistant major depressive disorder: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(6):826-831.

15. Mahmoud RA, Pandina GJ, Turkoz I, et al. Risperidone for treatment-refractory major depressive disorder: A randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(9):593-602.

16. Barbee JG, Conrad EJ, Jamhour NJ. The effectiveness of olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, and ziprasidone as augmentation agents in treatment resistant depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(7):975-981.

17. Fatemi SH, Emamian ES, Kist DA. Venlafaxine and bupropion combination therapy in a case of treatment-resistant depression. Ann Pharmacother.1999;33(6):701-703.

18. Carpenter LL, Yasman S, Price LH. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antidepressant augmentation with mirtazapine. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51(2):183-188.

19. Hannan N, Hamzah Z, Akinpeloye HO, Meagher D. Venlafaxine-mirtazapine combination therapy in the treatment of persistent depressive illness. J Psychopharmacol. 2007;21(2):161-164.

20. McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Fava M, et al. Tranylcypromine versus venlafaxine plus mirtazapine following three failed antidepressant medication trials for depression: A STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(9):1531-1541.

21. Blier P, Ward HE, Tremblay P, Laberge L, Hébert C, Bergeron R. Combination of antidepressant medications from treatment initiation for major depressive disorder: A double-blind randomized study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(3):281-288.

22. Papakostas GI, Mischoulon D, Shyu I, Alpert JE, Fava M. S-adenosyl methionine (SAMe) augmentation of serotonin reuptake inhibitors for antidepressant nonresponders with major depressive disorder: A double blind randomized clinical trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(8):942-948.

23. Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Zajecka JM, et al. L-methylfolate as adjunctive therapy

for SSRI-resistant major depression: Results of two randomized, double-blind,

parallel-sequential trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(12):1267-1274.

24. Korston TR. Drugs of abuse. In: Katzung BG, ed. Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2004:521-523.

25. Feighner JP, Herbstein J, Damlouji N. Combined MAOI, TCA, and direct stimulant therapy of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1985;46(6):206-209.

26. Fawcett J, Kravitz HM, Zajecka JM, Schaff MR. CNS stimulant potentiation of monoamine oxidase inhibitors in treatment-refractory depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1991;11(2):127-132.

27. Stoll AL, Pillay SS, Diamond L, Workum SB, Cole JO. Methylphenidate augmentation of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors: A case series. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(2):72-76.

28. Masand PS, Anand VS, Tanquary JF. Psychostimulant augmentation of second generation antidepressants: A case series. Depress Anxiety. 1998;7(2):89-91.

29. Trivedi MH, Cutler AJ, Richards C, et al. A randomized control trial of the efficacy and safety of lisdesxamfetamine dimesylate as augmentation therapy in adults with residual symptoms of major depressive disorder after treatment with escitalopram. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(8):802-809.

30. Madhoo M, Keefe RS, Roth RM, et al. Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate augmentation in adults with persistent executive dysfunction after partial or full remission of major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2014;39(6):1388-1398.

31. Parker G, Brotchie H. Do the old psychostimulant drugs have a role in managing treatment-resistant depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(4):308-314.

32. Parker G, Brotchie H, McClure G, Fletcher K. Psychostimulants for managing unipolar and bipolar treatment-resistant melancholic depression: A medium term evaluation of cost benefits. J Affect Disord. 2013;151(1):360-364.

33. Lydon E, El-Mallakh RS. Naturalistic long-term use of methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(5):516-518.

34. Carlson PJ, Merlock MC, Suppes T. Adjunctive stimulant use in patients with bipolar disorder: Treatment of residual depression and sedation. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6(5):416-420.

35. El-Mallakh RS. An open study of methylphenidate in bipolar depression. Bipolar Disord. 2000;2(1):56-59.

36. Ravindran AV, Kennedy SH, O’Donovan MC, Fallu A, Camacho F, Binder CE. Osmotic-release oral system methylphenidate augmentation of antidepressant monotherapy in major depressive disorder: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(1):87-94.

37. Patkar AA, Masand PS, Pae CU, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled

trial of augmentation with an extended release formulation of methylphenidate in outpatients with treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;26(6):653-656.

38. Lee H, Kim SW, Kim JM, Shin IS, Yang SJ, Yoon JS Comparing effects of methylphenidate, sertraline, and placebo on neuropsychiatric sequelae in patients with

traumatic brain injury. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20(2):97-104.

39. Gualtieri CT, Evans RW. Stimulant treatment for the neurobehavioural sequelae of traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 1988;2(4):273-290.

40. Provigil [package insert]. North Wales, PA: Cephalon Inc; 2015.

41. Nuvigil [package insert]. Frazer, PA: Cephalon, Inc; 2013.

42. Menza MA, Kaufman KR, Castellanos A. Modafinil augmentation of antidepressant treatment in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(5):378-381.

43. Markovitz PJ, Wagner S. An open-label trial of modafinil augmentation in patients with partial response to antidepressant therapy. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;23(2):207-209.

44. Fernandes PP, Petty F. Modafinil for remitted bipolar depression with hypersomnia. Ann Pharmacother. 2003;37(12):1807-1809.

45. Nasr S. Modafinil as adjunctive therapy in depressed outpatients. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2004;16(3):133-138.

46. DeBattista C, Lembke A, Solvason HB, Ghebremichael R, Poirier J. A prospective trial of modafinil as an adjunctive treatment of major depression. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(1):87-90.

47. Nasr S, Wendt B, Steiner K. Absence of mood switch with and tolerance to modafinil: A replication study from a large private practice. J Affect Disord. 2006;95(1-3):111-114.

48. DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Menza MA, Rosenthal MH, Fieve RR; Modafinil in Depression Study Group. Adjunct modafinil for the short-term treatment of fatigue and sleepiness in patients with major depressive disorder: A preliminary doubleblind, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(9):1057-1064.

49. Frye MA, Grunze H, Suppes T, et al. A placebo-controlled evaluation of adjunctive modafinil in the treatment of bipolar depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(8):1242-1249.

50. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C, Doghramji K, Arora S, Hughes RJ. Modafinil augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor therapy in MDD partial responders with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19(3):153-159.

51. Thase ME, Fava M, DeBattista C, Arora S, Hughes RJ. Modafinil augmentation of SSRI therapy in patients with major depressive disorder and excessive sleepiness and fatigue: A 12-week, open-label, extension study. CNS Spectr. 2006;11(2):93-102.

52. Fava M, Thase ME, DeBattista C. A multicenter, placebo-controlled study of modafinil augmentation in partial responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors with persistent fatigue and sleepiness. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(1):85-93.

53. Abolfazli R, Hosseini M, Ghanizadeh A, et al. Double-blind randomized parallelgroup clinical trial of efficacy of the combination fluoxetine plus modafinil versus fluoxetine plus placebo in the treatment of major depression. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(4):297-302.

54. Rasmussen NA, Schrøder P, Olsen LR, Brødsgaard M, Undén M, Bech P. Modafinil augmentation in depressed patients with partial response to antidepressants: A pilot study on self-reported symptoms covered by the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) and the Symptom Checklist (SCL-92). Nord J Psychiatry. 2005;59(3):173-178.

55. Dunlop BW, Crits-Christoph P, Evans DL, et al. Coadministration of modafinil and a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor from the initiation of treatment of major depressive disorder with fatigue and sleepiness: A double-blind, placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27(6):614-619.

56. Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Youakim JM, Tiller JM, Yang R, Frye MA. Adjunctive armodafinil

for major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: A randomized multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1363-1370.

57. Calabrese JR, Frye MA, Yang R, Ketter TA; Armodafinil Treatment Trial Study Network. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive armodafinil in adults with major depressive episodes associated with bipolar I disorder: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(10):1054-1061.

58. Strattera [package insert]. Indianapolis, IN. Lilly; 2015.

59. Carpenter LL, Milosavljevic N, Schecter JM, Tyrka AR, Price LH. Augmentation with open-label atomoxetine for partial or nonresponse to antidepressants. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(10):1234-1238.

60. Papakostas GI, Petersen TJ, Burns AM, Fava M. Adjunctive atomoxetine for residual

fatigue in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):370-373.

61. Michelson D, Adler LA, Amsterdam JD, et al. Addition of atomoxetine for depression

incompletely responsive to sertraline: A randomized, double-blind, placebocontrolled study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(4):582-587.

62. Corp SA, Gitlin MJ, Altshuler LL. A review of the use of stimulants and stimulant alternatives in treating bipolar depression and major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(9):1010-1018.

63. Kraemer M, Uekermann J, Wiltfang J, Kis B. Methylphenidate-induced psychosis in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Report of 3 new cases and review of the literature. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2010;33(4):204-206.

64. Berman SM, Kuczenski R, McCracken JT, London ED. Potential adverse effects of amphetamine treatment on brain and behavior: A review. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14(2):123-142.

65. Fredriksen M, Dahl AA, Martinsen EW, Klungsøyr O, Haavik J, Peleikis DE. Effectiveness of one-year pharmacological treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): An open-label prospective study of time in treatment, dose, side-effects and comorbidity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(12):1873-1874.