User login

Many findings of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness in schizophrenia (CATIE) were unexpected,1,2 but one was arguably the most surprising. It was that schizophrenia patients showed similar rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), whether treated with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) or any of four second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

This finding in CATIE phase 1 runs contrary to the understanding that SGAs, compared with FGAs, provide a broader spectrum of efficacy with significantly fewer motor side effects. A substantial body of evidence and virtually all schizophrenia treatment guidelines3-5 support this prevailing view.

Did earlier schizophrenia treatment studies misinform us, or was CATIE’s comparison of FGAs and SGAs “flawed”?6,7 This article attempts to reconcile the divergent findings about antipsychotics and EPS and reveals a clinical pearl that suggests how to provide optimum antipsychotic therapy to schizophrenia patients.

What did catie find?

CATIE was a three-phase, 18-month, randomized controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of five SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and clozapine) and two FGAs (perphenazine and fluphenazine) in treating schizophrenia. Findings from phases 1 and 2 have been published or presented (Table 1),2,8-9 and results from phase 3 are awaited.

Table 1

5 key findings from CATIE phases 1 and 2

|

CATIE phase 1 found no difference in efficacy, safety/tolerability, or effectiveness among perphenazine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and quetiapine. Soon-to-be-published data also will show no significant difference in cognitive effects among patients receiving perphenazine or any of four SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or ziprasidone).8 Because no FGA was used in CATIE phase 2,9-11 its results added little to phase 1 observations about how “typical” and “atypical” antipsychotics compare.

‘Atypicals’ and EPS. By definition, a reduced tendency to cause EPS (such as parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia, and akinesia) distinguishes SGAs from FGAs. In fact, SGAs were called “atypical” because they disproved the belief that EPS are an unavoidable consequence of drugs that produce an antipsychotic effect.12,13 The CATIE trial’s inability to detect a difference in EPS rates between typical and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2)2 is therefore the study’s most surprising finding.

Table 2

CATIE: Similar EPS rates with perphenazine and SGAs*

| EPS measurement | Perphenazine-treated patients | SGA-treated patients |

|---|---|---|

| Increased mean Simpson-Angus Scale score | 6% | 4% to 8% |

| Increased AIMS global severity score | 17% | 13% to 16% |

| Increased Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale score | 7% | 5% to 9% |

| Anticholinergic added | 10% | 3% to 9% |

| * Differences were not statistically significant | ||

| EPS: extrapyramidal side effects | ||

| SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

| AIMS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale | ||

| Source: Reference 2 | ||

Making sense of catie

Most studies suggest consistent differences between FGAs and SGAs in risk of EPS and tardive dyskinesia.14-16 One explanation for CATIE’s discrepant findings may be that the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the typical comparator in pre-CATIE studies magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs.17,18

Conversely, CATIE researchers minimized this difference by studying a population of schizophrenia patients at an unusually low risk for EPS. The study design:

- assigned 231 patients with a history of tardive dyskinesia to an SGA, without the opportunity to be randomly assigned to an FGA

- excluded patients with first-episode schizophrenia

- enrolled patients who had been treated with antipsychotics for an average of 14 years without a history of significant adverse effects from study treatments.19

Just as prior studies might have exaggerated the EPS advantage for SGAs, CATIE might have minimized the FGA-SGA difference by studying a low-risk cohort in a way that reduced the trial’s ability to detect such differences.

Interpretation. How can we reconcile the absence of a difference between FGAs and SGAs in EPS liability in CATIE with the preponderance of data suggesting otherwise? It appears that SGAs may be less likely to cause EPS than FGAs, but this difference is not evident in all populations. Furthermore, SGAs and FGAs differ in their ability to provide an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS.

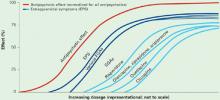

Among FGAs, low-potency agents are less likely to cause EPS or require concomitant anticholinergics than high-potency agents. Among SGAs, the gradient of EPS liability appears to be risperidone > olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine (Figure). Clinically, these pharmacologic differences interact with physiologic differences in EPS vulnerability—some patients are more liable to develop EPS than others. Individuals who are more susceptible to developing EPS are more likely to benefit from antipsychotics with lower EPS liability.

CATIE found no difference among the various FGAs and SGAs with regard to overall efficacy, effects on cognition, and occurrence of tardive dyskinesia in treating chronic schizophrenia. Perhaps it was CATIE’s failure to find a difference in EPS that explains its inability to demonstrate FGA-SGA differences in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

Figure Dose-response curves: Antipsychotic vs extrapyramidal effects

All FGAs and SGAs produce an equivalent antipsychotic effect (red), but they vary in the degree of separation between dosages at which their antipsychotic and extrapyramidal effects occur.

Source: Adapted from reference 13

What catie tells us

The exaggerated view of SGAs as uniformly more efficacious, safer, and better tolerated than FGAs needs to be revised. At the same time, however, the results of CATIE should not be over-interpreted. They tell us that if the four phase 1 SGAs and the FGA perphenazine are used at certain dosages in a particular manner in a specific schizophrenia population—chronic, moderately ill, without tardive dyskinesia—then no differences might be expected among these antipsychotics. But CATIE’s findings might not generalize beyond individuals with schizophrenia at low risk for EPS.

CATIE underlines the importance of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS and without using anticholinergics. Clinical consequences of EPS extend beyond motor manifestations and include:

- worse cognition (bradyphrenia)

- worse negative symptoms (neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome)

- worse depression and suicidality (neuroleptic dysphoria)

- higher risk of tardive dyskinesia.20

SGAs’ presumed ability to provide broader efficacy—cognition, negative symptoms, dysphoria—and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia appears to be driven by their lower EPS liability in association with an equivalent antipsychotic effect. Evidence for an SGA advantage independent of this effect is weak.21,22

Thus, CATIE’s inability to find an FGA-SGA difference in EPS might explain its failure to observe an FGA-SGA difference in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

The clinical pearl

Avoiding EPS and anticholinergics appears to be the key to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with FGAs and SGAs. SGAs’ ability to achieve an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS also seems related to their lower risk of tardive dyskinesia.

SGAs’ main advantage may be their greater ease of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS or the need to add an anticholinergic to treat or prevent EPS. This comes from the broader separation between dosages at which SGAs produce their antipsychotic versus EPS effects, compared with FGAs (Figure).13

In clinical practice, then, we must achieve an adequate antipsychotic effect for our patients without EPS—whether we are using FGAs or SGAs—to obtain “atypical” benefits. The purported benefits of an “atypical” antipsychotic are not unique to a particular class of agents but relate to achieving a good antipsychotic effect without EPS—and the SGAs are better able to accomplish this than the FGAs.

Careful EPS monitoring is crucial to achieving optimal antipsychotic therapy. Reduced emphasis on EPS in the past decade (in awareness of EPS and training to detect symptoms) and overlap between behavioral aspects of EPS and psychopathology need to be addressed.

CATIE confirms clinical observations that:

Different agents are associated with different adverse effects, which can make achieving maximum efficacy and safety/tolerability challenging.

But differences among antipsychotics and heterogeneity in individual response and vulnerabilities may allow us to optimize treatment.

Different agents at different dosages may provide the best outcomes for individual patients, and the optimal agent and/or dosage can vary in the same patient at different stages of the illness. The CATIE trial contributes to evidence that guides our efforts to provide optimal antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia (Table 3). Its “surprising” findings are most useful when considered in the context of the database to which it adds.25

Table 3

Treating chronic schizophrenia: 4 clinical tips from CATIE

| Minimizing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) is essential, whether using FGAs or SGAs |

| Avoiding EPS and not using adjunctive anticholinergics is the key to SGAs’ purported benefits, such better cognition, less dysphoria, lower negative symptom burden, and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia |

| Antipsychotic dosing is key to accomplishing an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS |

| Match the antipsychotic choice and dosage to the individual patient’s vulnerability, then make adjustments based on response |

Related resources

- Tandon R. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: What does CATIE tell us? Parts 1 and 2. Int Drug Ther Newsl 2006;41:51-8;67-74.

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia.

Drug brand names

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Permitil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Nasrallah HA. CATIE’s surprises. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(2):48-65.

2. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

3. Kane JM, Leucht S, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: optimizing pharmacologic treatment of psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 12):1-100.

4. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2003 update. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:500-8.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

6. Kane JM. Commentary on the CATIE trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:831-2.

7. Glick ID. Understanding the results of CATIE in the context of the field. CNS Spectrums 2006;1(suppl 7):40-7.

8. Keefe RSE. Neurocognitive effects of antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Paper presented at: 61st Society of Biological Psychiatry annual meeting; May 18-20, 2006; Toronto, Canada.

9. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:600-10.

10. Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:611-22.

11. Buckley PF. Which antipsychotic do I choose next? CATIE phase 2 offers insights on efficacy and tolerability. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(9):27-43.

12. Casey DE. Motor and mental aspects of EPS. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;10:105-14.

13. Jibson MD, Tandon R. New atypical antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32:215-28.

14. Pierre JM. Extrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics. Drug Safety 2005;28:191-208.

15. Kelly DL, Conley RR, Carpenter WT. First-episode schizophrenia: A focus on pharmacological treatment and safety considerations. Drugs 2005;65:1113-38.

16. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

17. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. BMJ 2000;231:1371-6.

18. Hugenholtz GW, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparator in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:897-903.

19. Casey D. Implications of the CATIE trial on treatment: extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):25-31.

20. Tandon R. Jibson MD: Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic treatment: Scope of problem and impact on outcome. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2002;14:123-9.

21. Thornton AE, Snellenberg JXV, Sepehry AA, Honer WG. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on long-term memory dysfunction in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a quantitative review. J Psychopharmacol 2006;20:335-46.

22. Carpenter WT, Gold JM. Another view of therapy for cognition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51:972-8.

23. Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24:192-208.

24. Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Subjecting meta-analyses to closer scrutiny: Little support for differential efficacy among second-generation antipsychotics at equivalent doses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;62:935-7.

25. Tandon R. Comparing antipsychotic efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1645.-

Many findings of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness in schizophrenia (CATIE) were unexpected,1,2 but one was arguably the most surprising. It was that schizophrenia patients showed similar rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), whether treated with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) or any of four second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

This finding in CATIE phase 1 runs contrary to the understanding that SGAs, compared with FGAs, provide a broader spectrum of efficacy with significantly fewer motor side effects. A substantial body of evidence and virtually all schizophrenia treatment guidelines3-5 support this prevailing view.

Did earlier schizophrenia treatment studies misinform us, or was CATIE’s comparison of FGAs and SGAs “flawed”?6,7 This article attempts to reconcile the divergent findings about antipsychotics and EPS and reveals a clinical pearl that suggests how to provide optimum antipsychotic therapy to schizophrenia patients.

What did catie find?

CATIE was a three-phase, 18-month, randomized controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of five SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and clozapine) and two FGAs (perphenazine and fluphenazine) in treating schizophrenia. Findings from phases 1 and 2 have been published or presented (Table 1),2,8-9 and results from phase 3 are awaited.

Table 1

5 key findings from CATIE phases 1 and 2

|

CATIE phase 1 found no difference in efficacy, safety/tolerability, or effectiveness among perphenazine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and quetiapine. Soon-to-be-published data also will show no significant difference in cognitive effects among patients receiving perphenazine or any of four SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or ziprasidone).8 Because no FGA was used in CATIE phase 2,9-11 its results added little to phase 1 observations about how “typical” and “atypical” antipsychotics compare.

‘Atypicals’ and EPS. By definition, a reduced tendency to cause EPS (such as parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia, and akinesia) distinguishes SGAs from FGAs. In fact, SGAs were called “atypical” because they disproved the belief that EPS are an unavoidable consequence of drugs that produce an antipsychotic effect.12,13 The CATIE trial’s inability to detect a difference in EPS rates between typical and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2)2 is therefore the study’s most surprising finding.

Table 2

CATIE: Similar EPS rates with perphenazine and SGAs*

| EPS measurement | Perphenazine-treated patients | SGA-treated patients |

|---|---|---|

| Increased mean Simpson-Angus Scale score | 6% | 4% to 8% |

| Increased AIMS global severity score | 17% | 13% to 16% |

| Increased Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale score | 7% | 5% to 9% |

| Anticholinergic added | 10% | 3% to 9% |

| * Differences were not statistically significant | ||

| EPS: extrapyramidal side effects | ||

| SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

| AIMS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale | ||

| Source: Reference 2 | ||

Making sense of catie

Most studies suggest consistent differences between FGAs and SGAs in risk of EPS and tardive dyskinesia.14-16 One explanation for CATIE’s discrepant findings may be that the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the typical comparator in pre-CATIE studies magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs.17,18

Conversely, CATIE researchers minimized this difference by studying a population of schizophrenia patients at an unusually low risk for EPS. The study design:

- assigned 231 patients with a history of tardive dyskinesia to an SGA, without the opportunity to be randomly assigned to an FGA

- excluded patients with first-episode schizophrenia

- enrolled patients who had been treated with antipsychotics for an average of 14 years without a history of significant adverse effects from study treatments.19

Just as prior studies might have exaggerated the EPS advantage for SGAs, CATIE might have minimized the FGA-SGA difference by studying a low-risk cohort in a way that reduced the trial’s ability to detect such differences.

Interpretation. How can we reconcile the absence of a difference between FGAs and SGAs in EPS liability in CATIE with the preponderance of data suggesting otherwise? It appears that SGAs may be less likely to cause EPS than FGAs, but this difference is not evident in all populations. Furthermore, SGAs and FGAs differ in their ability to provide an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS.

Among FGAs, low-potency agents are less likely to cause EPS or require concomitant anticholinergics than high-potency agents. Among SGAs, the gradient of EPS liability appears to be risperidone > olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine (Figure). Clinically, these pharmacologic differences interact with physiologic differences in EPS vulnerability—some patients are more liable to develop EPS than others. Individuals who are more susceptible to developing EPS are more likely to benefit from antipsychotics with lower EPS liability.

CATIE found no difference among the various FGAs and SGAs with regard to overall efficacy, effects on cognition, and occurrence of tardive dyskinesia in treating chronic schizophrenia. Perhaps it was CATIE’s failure to find a difference in EPS that explains its inability to demonstrate FGA-SGA differences in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

Figure Dose-response curves: Antipsychotic vs extrapyramidal effects

All FGAs and SGAs produce an equivalent antipsychotic effect (red), but they vary in the degree of separation between dosages at which their antipsychotic and extrapyramidal effects occur.

Source: Adapted from reference 13

What catie tells us

The exaggerated view of SGAs as uniformly more efficacious, safer, and better tolerated than FGAs needs to be revised. At the same time, however, the results of CATIE should not be over-interpreted. They tell us that if the four phase 1 SGAs and the FGA perphenazine are used at certain dosages in a particular manner in a specific schizophrenia population—chronic, moderately ill, without tardive dyskinesia—then no differences might be expected among these antipsychotics. But CATIE’s findings might not generalize beyond individuals with schizophrenia at low risk for EPS.

CATIE underlines the importance of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS and without using anticholinergics. Clinical consequences of EPS extend beyond motor manifestations and include:

- worse cognition (bradyphrenia)

- worse negative symptoms (neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome)

- worse depression and suicidality (neuroleptic dysphoria)

- higher risk of tardive dyskinesia.20

SGAs’ presumed ability to provide broader efficacy—cognition, negative symptoms, dysphoria—and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia appears to be driven by their lower EPS liability in association with an equivalent antipsychotic effect. Evidence for an SGA advantage independent of this effect is weak.21,22

Thus, CATIE’s inability to find an FGA-SGA difference in EPS might explain its failure to observe an FGA-SGA difference in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

The clinical pearl

Avoiding EPS and anticholinergics appears to be the key to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with FGAs and SGAs. SGAs’ ability to achieve an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS also seems related to their lower risk of tardive dyskinesia.

SGAs’ main advantage may be their greater ease of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS or the need to add an anticholinergic to treat or prevent EPS. This comes from the broader separation between dosages at which SGAs produce their antipsychotic versus EPS effects, compared with FGAs (Figure).13

In clinical practice, then, we must achieve an adequate antipsychotic effect for our patients without EPS—whether we are using FGAs or SGAs—to obtain “atypical” benefits. The purported benefits of an “atypical” antipsychotic are not unique to a particular class of agents but relate to achieving a good antipsychotic effect without EPS—and the SGAs are better able to accomplish this than the FGAs.

Careful EPS monitoring is crucial to achieving optimal antipsychotic therapy. Reduced emphasis on EPS in the past decade (in awareness of EPS and training to detect symptoms) and overlap between behavioral aspects of EPS and psychopathology need to be addressed.

CATIE confirms clinical observations that:

Different agents are associated with different adverse effects, which can make achieving maximum efficacy and safety/tolerability challenging.

But differences among antipsychotics and heterogeneity in individual response and vulnerabilities may allow us to optimize treatment.

Different agents at different dosages may provide the best outcomes for individual patients, and the optimal agent and/or dosage can vary in the same patient at different stages of the illness. The CATIE trial contributes to evidence that guides our efforts to provide optimal antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia (Table 3). Its “surprising” findings are most useful when considered in the context of the database to which it adds.25

Table 3

Treating chronic schizophrenia: 4 clinical tips from CATIE

| Minimizing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) is essential, whether using FGAs or SGAs |

| Avoiding EPS and not using adjunctive anticholinergics is the key to SGAs’ purported benefits, such better cognition, less dysphoria, lower negative symptom burden, and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia |

| Antipsychotic dosing is key to accomplishing an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS |

| Match the antipsychotic choice and dosage to the individual patient’s vulnerability, then make adjustments based on response |

Related resources

- Tandon R. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: What does CATIE tell us? Parts 1 and 2. Int Drug Ther Newsl 2006;41:51-8;67-74.

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia.

Drug brand names

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Permitil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Many findings of the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness in schizophrenia (CATIE) were unexpected,1,2 but one was arguably the most surprising. It was that schizophrenia patients showed similar rates of extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS), whether treated with a first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) or any of four second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs).

This finding in CATIE phase 1 runs contrary to the understanding that SGAs, compared with FGAs, provide a broader spectrum of efficacy with significantly fewer motor side effects. A substantial body of evidence and virtually all schizophrenia treatment guidelines3-5 support this prevailing view.

Did earlier schizophrenia treatment studies misinform us, or was CATIE’s comparison of FGAs and SGAs “flawed”?6,7 This article attempts to reconcile the divergent findings about antipsychotics and EPS and reveals a clinical pearl that suggests how to provide optimum antipsychotic therapy to schizophrenia patients.

What did catie find?

CATIE was a three-phase, 18-month, randomized controlled clinical trial designed to evaluate the effectiveness of five SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, ziprasidone, and clozapine) and two FGAs (perphenazine and fluphenazine) in treating schizophrenia. Findings from phases 1 and 2 have been published or presented (Table 1),2,8-9 and results from phase 3 are awaited.

Table 1

5 key findings from CATIE phases 1 and 2

|

CATIE phase 1 found no difference in efficacy, safety/tolerability, or effectiveness among perphenazine, risperidone, ziprasidone, and quetiapine. Soon-to-be-published data also will show no significant difference in cognitive effects among patients receiving perphenazine or any of four SGAs (risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine, or ziprasidone).8 Because no FGA was used in CATIE phase 2,9-11 its results added little to phase 1 observations about how “typical” and “atypical” antipsychotics compare.

‘Atypicals’ and EPS. By definition, a reduced tendency to cause EPS (such as parkinsonism, dystonia, akathisia, and akinesia) distinguishes SGAs from FGAs. In fact, SGAs were called “atypical” because they disproved the belief that EPS are an unavoidable consequence of drugs that produce an antipsychotic effect.12,13 The CATIE trial’s inability to detect a difference in EPS rates between typical and atypical antipsychotics (Table 2)2 is therefore the study’s most surprising finding.

Table 2

CATIE: Similar EPS rates with perphenazine and SGAs*

| EPS measurement | Perphenazine-treated patients | SGA-treated patients |

|---|---|---|

| Increased mean Simpson-Angus Scale score | 6% | 4% to 8% |

| Increased AIMS global severity score | 17% | 13% to 16% |

| Increased Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale score | 7% | 5% to 9% |

| Anticholinergic added | 10% | 3% to 9% |

| * Differences were not statistically significant | ||

| EPS: extrapyramidal side effects | ||

| SGA: second-generation antipsychotic | ||

| AIMS: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale | ||

| Source: Reference 2 | ||

Making sense of catie

Most studies suggest consistent differences between FGAs and SGAs in risk of EPS and tardive dyskinesia.14-16 One explanation for CATIE’s discrepant findings may be that the use of high-dose, high-potency haloperidol as the typical comparator in pre-CATIE studies magnified differences between FGAs and SGAs.17,18

Conversely, CATIE researchers minimized this difference by studying a population of schizophrenia patients at an unusually low risk for EPS. The study design:

- assigned 231 patients with a history of tardive dyskinesia to an SGA, without the opportunity to be randomly assigned to an FGA

- excluded patients with first-episode schizophrenia

- enrolled patients who had been treated with antipsychotics for an average of 14 years without a history of significant adverse effects from study treatments.19

Just as prior studies might have exaggerated the EPS advantage for SGAs, CATIE might have minimized the FGA-SGA difference by studying a low-risk cohort in a way that reduced the trial’s ability to detect such differences.

Interpretation. How can we reconcile the absence of a difference between FGAs and SGAs in EPS liability in CATIE with the preponderance of data suggesting otherwise? It appears that SGAs may be less likely to cause EPS than FGAs, but this difference is not evident in all populations. Furthermore, SGAs and FGAs differ in their ability to provide an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS.

Among FGAs, low-potency agents are less likely to cause EPS or require concomitant anticholinergics than high-potency agents. Among SGAs, the gradient of EPS liability appears to be risperidone > olanzapine, aripiprazole, ziprasidone > quetiapine > clozapine (Figure). Clinically, these pharmacologic differences interact with physiologic differences in EPS vulnerability—some patients are more liable to develop EPS than others. Individuals who are more susceptible to developing EPS are more likely to benefit from antipsychotics with lower EPS liability.

CATIE found no difference among the various FGAs and SGAs with regard to overall efficacy, effects on cognition, and occurrence of tardive dyskinesia in treating chronic schizophrenia. Perhaps it was CATIE’s failure to find a difference in EPS that explains its inability to demonstrate FGA-SGA differences in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

Figure Dose-response curves: Antipsychotic vs extrapyramidal effects

All FGAs and SGAs produce an equivalent antipsychotic effect (red), but they vary in the degree of separation between dosages at which their antipsychotic and extrapyramidal effects occur.

Source: Adapted from reference 13

What catie tells us

The exaggerated view of SGAs as uniformly more efficacious, safer, and better tolerated than FGAs needs to be revised. At the same time, however, the results of CATIE should not be over-interpreted. They tell us that if the four phase 1 SGAs and the FGA perphenazine are used at certain dosages in a particular manner in a specific schizophrenia population—chronic, moderately ill, without tardive dyskinesia—then no differences might be expected among these antipsychotics. But CATIE’s findings might not generalize beyond individuals with schizophrenia at low risk for EPS.

CATIE underlines the importance of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS and without using anticholinergics. Clinical consequences of EPS extend beyond motor manifestations and include:

- worse cognition (bradyphrenia)

- worse negative symptoms (neuroleptic-induced deficit syndrome)

- worse depression and suicidality (neuroleptic dysphoria)

- higher risk of tardive dyskinesia.20

SGAs’ presumed ability to provide broader efficacy—cognition, negative symptoms, dysphoria—and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia appears to be driven by their lower EPS liability in association with an equivalent antipsychotic effect. Evidence for an SGA advantage independent of this effect is weak.21,22

Thus, CATIE’s inability to find an FGA-SGA difference in EPS might explain its failure to observe an FGA-SGA difference in cognition and other effectiveness domains.

The clinical pearl

Avoiding EPS and anticholinergics appears to be the key to improving cognition, dysphoria, and negative symptoms with FGAs and SGAs. SGAs’ ability to achieve an equivalent antipsychotic effect without EPS also seems related to their lower risk of tardive dyskinesia.

SGAs’ main advantage may be their greater ease of achieving an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS or the need to add an anticholinergic to treat or prevent EPS. This comes from the broader separation between dosages at which SGAs produce their antipsychotic versus EPS effects, compared with FGAs (Figure).13

In clinical practice, then, we must achieve an adequate antipsychotic effect for our patients without EPS—whether we are using FGAs or SGAs—to obtain “atypical” benefits. The purported benefits of an “atypical” antipsychotic are not unique to a particular class of agents but relate to achieving a good antipsychotic effect without EPS—and the SGAs are better able to accomplish this than the FGAs.

Careful EPS monitoring is crucial to achieving optimal antipsychotic therapy. Reduced emphasis on EPS in the past decade (in awareness of EPS and training to detect symptoms) and overlap between behavioral aspects of EPS and psychopathology need to be addressed.

CATIE confirms clinical observations that:

Different agents are associated with different adverse effects, which can make achieving maximum efficacy and safety/tolerability challenging.

But differences among antipsychotics and heterogeneity in individual response and vulnerabilities may allow us to optimize treatment.

Different agents at different dosages may provide the best outcomes for individual patients, and the optimal agent and/or dosage can vary in the same patient at different stages of the illness. The CATIE trial contributes to evidence that guides our efforts to provide optimal antipsychotic treatment of schizophrenia (Table 3). Its “surprising” findings are most useful when considered in the context of the database to which it adds.25

Table 3

Treating chronic schizophrenia: 4 clinical tips from CATIE

| Minimizing extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) is essential, whether using FGAs or SGAs |

| Avoiding EPS and not using adjunctive anticholinergics is the key to SGAs’ purported benefits, such better cognition, less dysphoria, lower negative symptom burden, and lower risk of tardive dyskinesia |

| Antipsychotic dosing is key to accomplishing an adequate antipsychotic effect without EPS |

| Match the antipsychotic choice and dosage to the individual patient’s vulnerability, then make adjustments based on response |

Related resources

- Tandon R. Comparative effectiveness of antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: What does CATIE tell us? Parts 1 and 2. Int Drug Ther Newsl 2006;41:51-8;67-74.

- Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia study. www.catie.unc.edu/schizophrenia.

Drug brand names

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Fluphenazine • Permitil

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Nasrallah HA. CATIE’s surprises. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(2):48-65.

2. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

3. Kane JM, Leucht S, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: optimizing pharmacologic treatment of psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 12):1-100.

4. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2003 update. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:500-8.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

6. Kane JM. Commentary on the CATIE trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:831-2.

7. Glick ID. Understanding the results of CATIE in the context of the field. CNS Spectrums 2006;1(suppl 7):40-7.

8. Keefe RSE. Neurocognitive effects of antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Paper presented at: 61st Society of Biological Psychiatry annual meeting; May 18-20, 2006; Toronto, Canada.

9. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:600-10.

10. Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:611-22.

11. Buckley PF. Which antipsychotic do I choose next? CATIE phase 2 offers insights on efficacy and tolerability. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(9):27-43.

12. Casey DE. Motor and mental aspects of EPS. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;10:105-14.

13. Jibson MD, Tandon R. New atypical antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32:215-28.

14. Pierre JM. Extrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics. Drug Safety 2005;28:191-208.

15. Kelly DL, Conley RR, Carpenter WT. First-episode schizophrenia: A focus on pharmacological treatment and safety considerations. Drugs 2005;65:1113-38.

16. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

17. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. BMJ 2000;231:1371-6.

18. Hugenholtz GW, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparator in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:897-903.

19. Casey D. Implications of the CATIE trial on treatment: extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):25-31.

20. Tandon R. Jibson MD: Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic treatment: Scope of problem and impact on outcome. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2002;14:123-9.

21. Thornton AE, Snellenberg JXV, Sepehry AA, Honer WG. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on long-term memory dysfunction in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a quantitative review. J Psychopharmacol 2006;20:335-46.

22. Carpenter WT, Gold JM. Another view of therapy for cognition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51:972-8.

23. Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24:192-208.

24. Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Subjecting meta-analyses to closer scrutiny: Little support for differential efficacy among second-generation antipsychotics at equivalent doses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;62:935-7.

25. Tandon R. Comparing antipsychotic efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1645.-

1. Nasrallah HA. CATIE’s surprises. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(2):48-65.

2. Lieberman JA, Stroup ST, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1209-23.

3. Kane JM, Leucht S, Carpenter D, et al. The expert consensus guideline series: optimizing pharmacologic treatment of psychotic disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 12):1-100.

4. Miller AL, Hall CS, Buchanan RW, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project antipsychotic algorithm for schizophrenia: 2003 update. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:500-8.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, 2nd ed. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(suppl 2):1-56.

6. Kane JM. Commentary on the CATIE trial. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:831-2.

7. Glick ID. Understanding the results of CATIE in the context of the field. CNS Spectrums 2006;1(suppl 7):40-7.

8. Keefe RSE. Neurocognitive effects of antipsychotic medications in patients with chronic schizophrenia in the CATIE trial. Paper presented at: 61st Society of Biological Psychiatry annual meeting; May 18-20, 2006; Toronto, Canada.

9. McEvoy JP, Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, et al. Effectiveness of clozapine versus olanzapine, quetiapine, and risperidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia who did not respond to prior antipsychotic treatment. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:600-10.

10. Stroup TS, Lieberman JA, McEvoy JP, et al. Effectiveness of olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone in patients with chronic schizophrenia following discontinuation of a previous atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:611-22.

11. Buckley PF. Which antipsychotic do I choose next? CATIE phase 2 offers insights on efficacy and tolerability. Current Psychiatry 2006;5(9):27-43.

12. Casey DE. Motor and mental aspects of EPS. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1995;10:105-14.

13. Jibson MD, Tandon R. New atypical antipsychotic medications. J Psychiatr Res 1998;32:215-28.

14. Pierre JM. Extrapyramidal symptoms with atypical antipsychotics. Drug Safety 2005;28:191-208.

15. Kelly DL, Conley RR, Carpenter WT. First-episode schizophrenia: A focus on pharmacological treatment and safety considerations. Drugs 2005;65:1113-38.

16. Correll CU, Leucht S, Kane JM. Lower risk for tardive dyskinesia associated with second-generation antipsychotics: a systematic review of 1-year studies. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:414-25.

17. Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, et al. Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: a systematic overview and meta-regression analysis. BMJ 2000;231:1371-6.

18. Hugenholtz GW, Heerdink ER, Stolker JJ, et al. Haloperidol dose when used as active comparator in randomized controlled trials with atypical antipsychotics in schizophrenia: comparison with officially recommended doses. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67:897-903.

19. Casey D. Implications of the CATIE trial on treatment: extrapyramidal symptoms. CNS Spectrums 2006;11(suppl 7):25-31.

20. Tandon R. Jibson MD: Extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic treatment: Scope of problem and impact on outcome. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2002;14:123-9.

21. Thornton AE, Snellenberg JXV, Sepehry AA, Honer WG. The impact of atypical antipsychotic medications on long-term memory dysfunction in schizophrenia spectrum disorder: a quantitative review. J Psychopharmacol 2006;20:335-46.

22. Carpenter WT, Gold JM. Another view of therapy for cognition in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2002;51:972-8.

23. Davis JM, Chen N. Dose response and dose equivalence of antipsychotics. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2004;24:192-208.

24. Tandon R, Nasrallah HA. Subjecting meta-analyses to closer scrutiny: Little support for differential efficacy among second-generation antipsychotics at equivalent doses. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006;62:935-7.

25. Tandon R. Comparing antipsychotic efficacy. Am J Psychiatry 2006;163:1645.-