User login

Cutaneous Presentation of Metastatic Salivary Duct Carcinoma

To the Editor:

Metastatic spread of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) to the skin is rare. Diagnosing SDC can be challenging because the cutaneous manifestations of this disease are variable and include nodules, papules, and erysipelaslike inflammation (also known as shield sign) with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles. We describe a case of cutaneous metastatic SDC that originated from the parotid gland and presented with 2 distinct cutaneous findings: sharply demarcated erythematous plaques and focally hemorrhagic angiomatous papules.

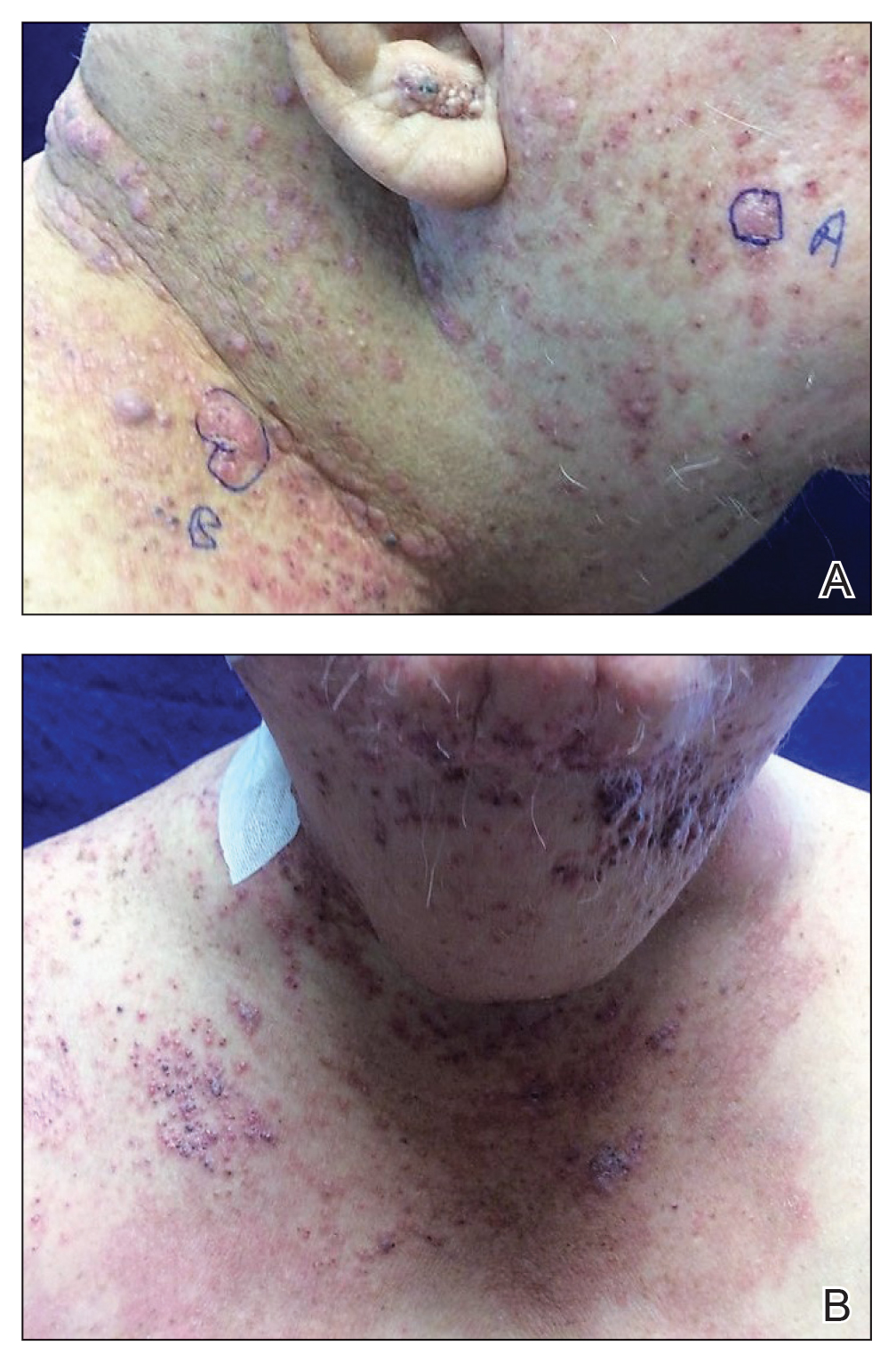

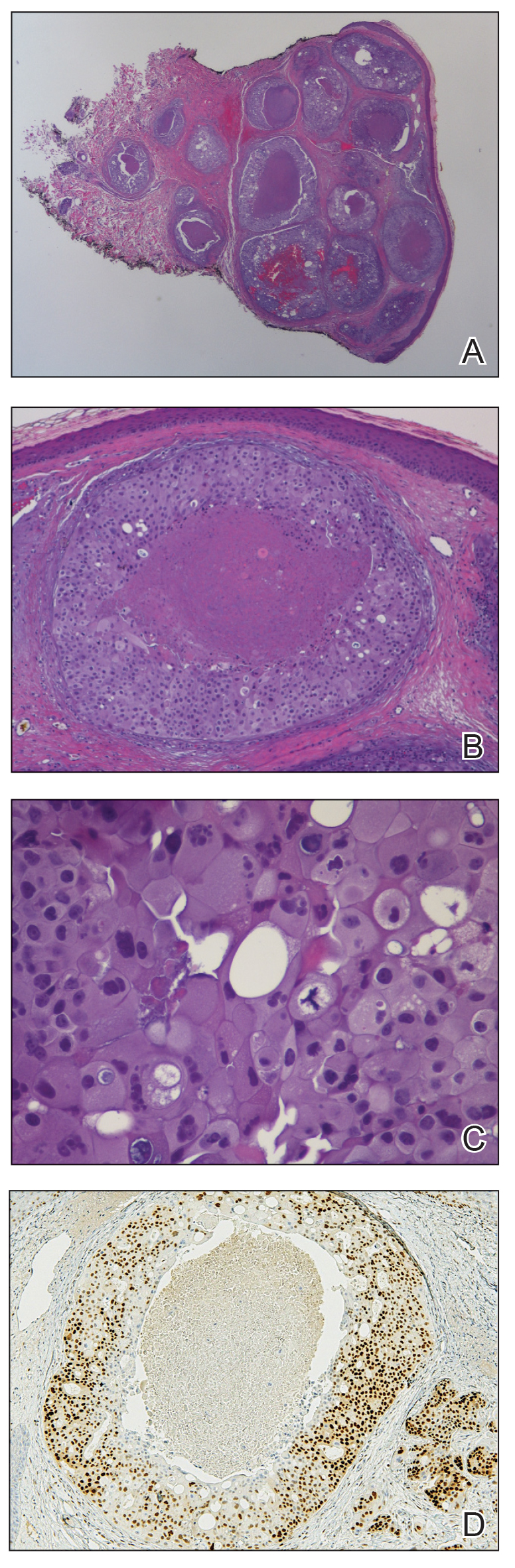

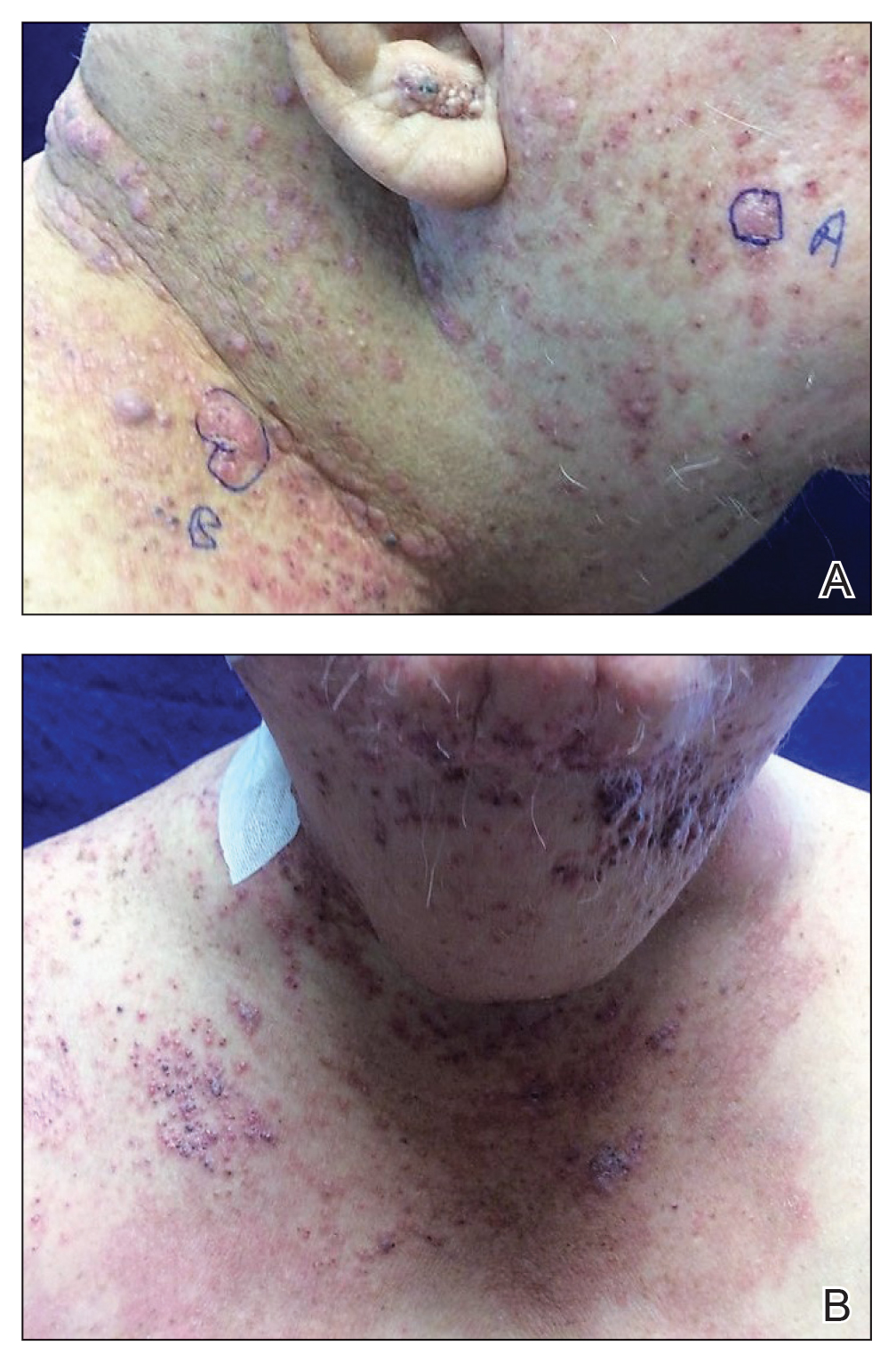

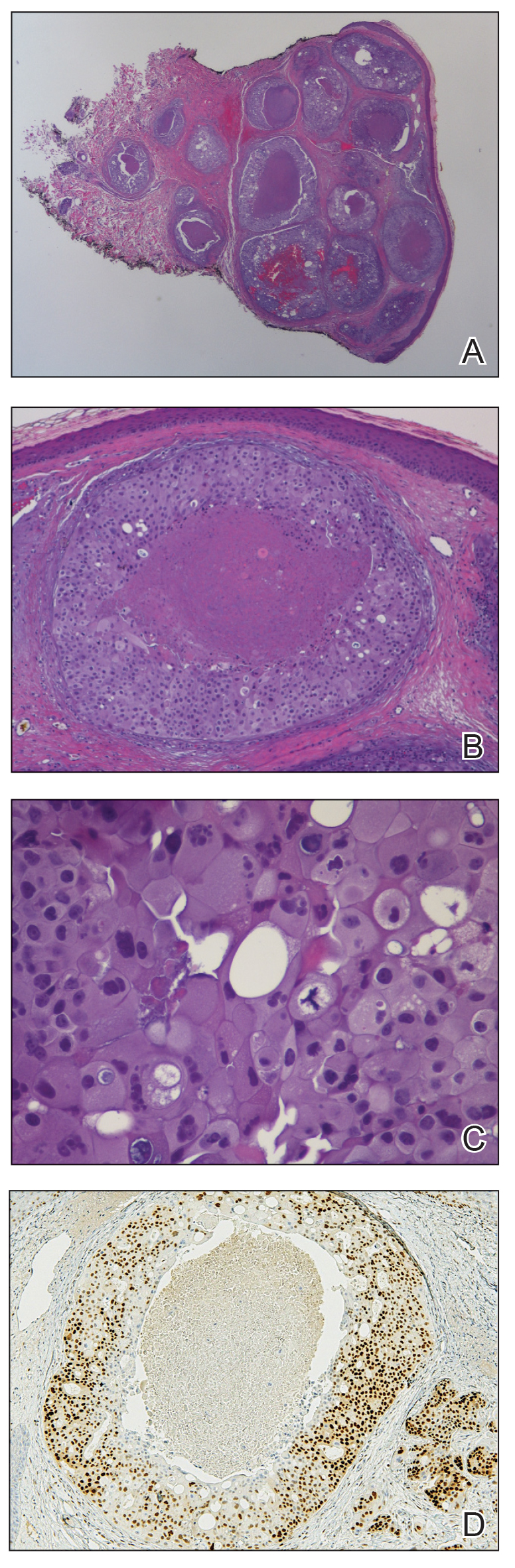

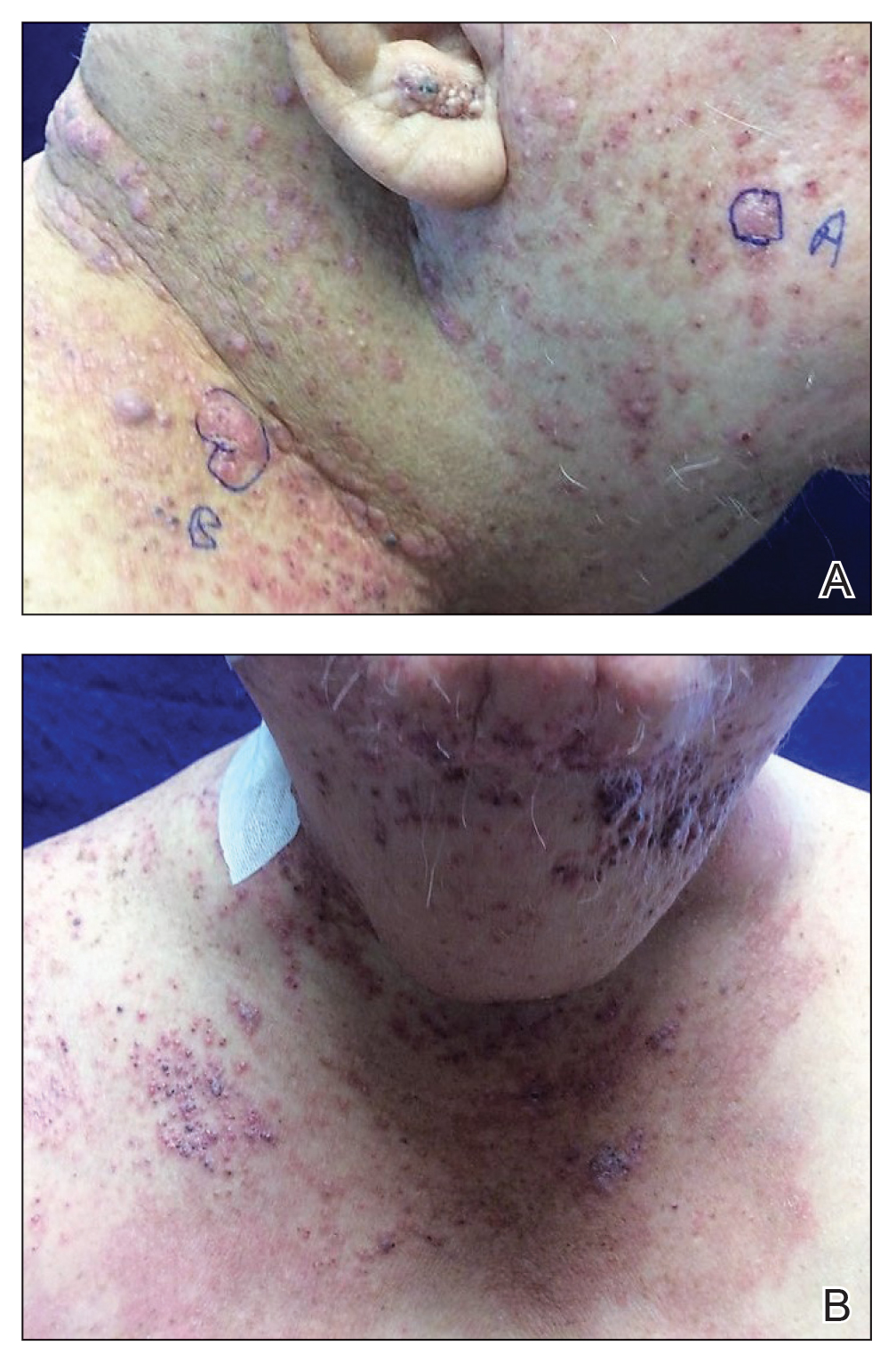

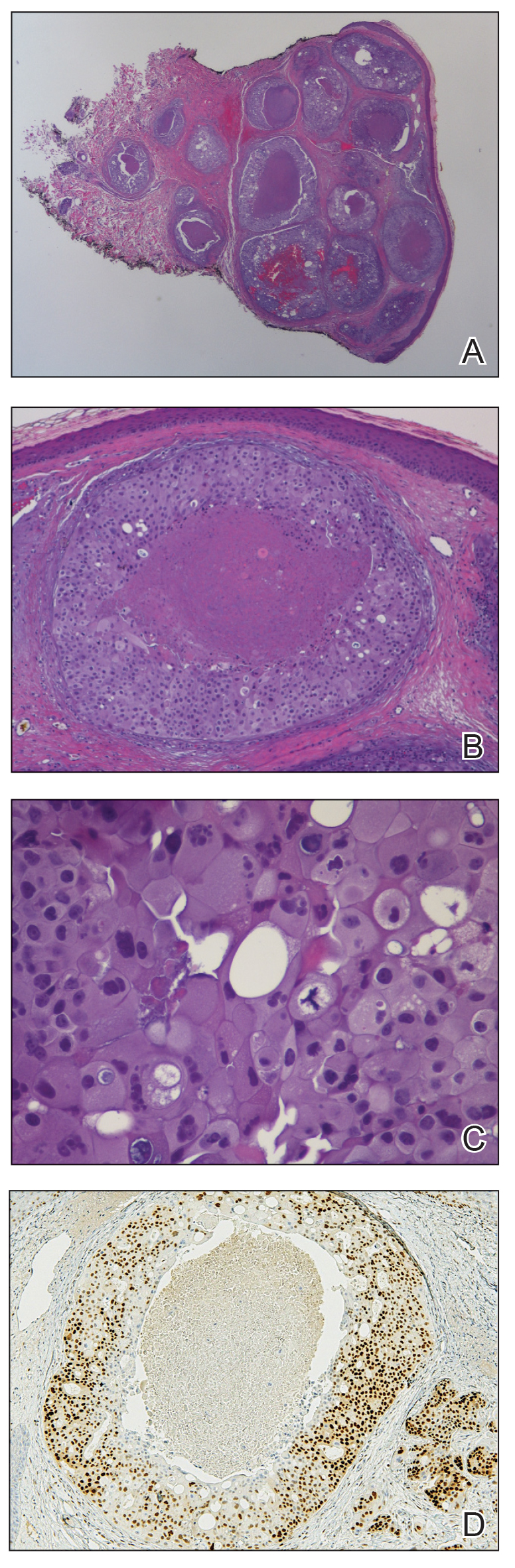

A 60-year-old man presented with a persistent polymorphous pruritic eruption of several months’ duration involving the entire face, ears, neck, and upper chest. He had a history of unspecified adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland diagnosed 2 years prior and underwent multiple treatment cycles with several chemotherapeutic agents over the course of 18 months. Physical examination showed erythematous papules and nodules on the face and neck with slight overlying scale. Sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules were noted on the neck and chest (Figure 1). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were sampled from representative nodular areas. Histopathology showed multiple round solid-tumor nodules with central necrosis in the superficial and deep dermis that were not associated with the overlying epidermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The tumor cells appeared polygonal and contained ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tumor nuclei showed marked pleomorphism, and numerous atypical mitotic figures were readily identifiable (Figure 2C). There was diffuse cytoplasmic staining with cytokeratin 7 and nuclear staining with androgen receptor (Figure 2D). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SDC metastatic to the skin.

The patient underwent 8 cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy. With disease progression, the chemotherapy regimen was changed to gemcitabine and methotrexate. The patient continued to experience disease progression and died 9 months after diagnosis of skin metastases.

Salivary duct carcinoma is rare and is estimated to represent 1% to 3% of all salivary malignancies.1 It is a highly aggressive form of salivary gland carcinoma and is associated with a poor clinical outcome. The 3-year overall survival rate for stage I disease is 42% and only 23% for stage IV disease.2 Salivary duct carcinoma has a high rate of distant metastasis,3 but cases of cutaneous metastases are rare.3-8 Previously reported cases of SDC that metastasized to the skin originated from the parotid gland (n=6) and submandibular gland (n=1).3

The diagnosis of cutaneous metastases is challenging due to the variability of the skin manifestations. Three cases described small firm nodules in patients,3-5 while others presented with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles.6-8 Our patient presented with sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules, which further emphasizes the capricious nature of skin findings.

The morphology of SDC is strikingly similar to ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast, which can lead to diagnostic confusion. Both carcinomas may show oncocytic cells, ductal formations, and cribriform structures with central comedo necrosis. Moreover, immunohistochemical features overlap, including positive staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. Positive immunohistochemistry with androgen receptor is consistent with SDC but also can be expressed in some cases of breast carcinoma.9,10 Therefore, the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement from metastatic SDC requires not just an evaluation of the pathologic features but careful attention to the clinical history and a thorough staging evaluation.

- D’heygere E, Meulemans J, Vander Poorten V. Salivary duct carcinoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26:142-151.

- Gilbert MR, Sharma A, Schmitt NC, et al. A 20-year review of 75 cases of salivary duct carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:489-495.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Andersen JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Tok J, Kao GF, Berberian BJ, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid adenocarcinoma. Report of a case with immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:303-306.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Hafiji J, Rytina E, Jani P, et al. A rare cutaneous presentation of metastatic parotid adenocarcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:E40-E42.

- Zanca A, Ferracini U, Bertazzoni MG. Telangiectatic metastasis from ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:113-114.

- Brys´ M, Wójcik M, Romanowicz-Makowska H, et al. Androgen receptor status in female breast cancer: RT-PCR and Western blot studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:85-90.

- Udager AM, Chiosea SI. Salivary duct carcinoma: an update on morphologic mimics and diagnostic use of androgen receptor immunohistochemistry. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:288-294.

To the Editor:

Metastatic spread of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) to the skin is rare. Diagnosing SDC can be challenging because the cutaneous manifestations of this disease are variable and include nodules, papules, and erysipelaslike inflammation (also known as shield sign) with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles. We describe a case of cutaneous metastatic SDC that originated from the parotid gland and presented with 2 distinct cutaneous findings: sharply demarcated erythematous plaques and focally hemorrhagic angiomatous papules.

A 60-year-old man presented with a persistent polymorphous pruritic eruption of several months’ duration involving the entire face, ears, neck, and upper chest. He had a history of unspecified adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland diagnosed 2 years prior and underwent multiple treatment cycles with several chemotherapeutic agents over the course of 18 months. Physical examination showed erythematous papules and nodules on the face and neck with slight overlying scale. Sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules were noted on the neck and chest (Figure 1). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were sampled from representative nodular areas. Histopathology showed multiple round solid-tumor nodules with central necrosis in the superficial and deep dermis that were not associated with the overlying epidermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The tumor cells appeared polygonal and contained ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tumor nuclei showed marked pleomorphism, and numerous atypical mitotic figures were readily identifiable (Figure 2C). There was diffuse cytoplasmic staining with cytokeratin 7 and nuclear staining with androgen receptor (Figure 2D). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SDC metastatic to the skin.

The patient underwent 8 cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy. With disease progression, the chemotherapy regimen was changed to gemcitabine and methotrexate. The patient continued to experience disease progression and died 9 months after diagnosis of skin metastases.

Salivary duct carcinoma is rare and is estimated to represent 1% to 3% of all salivary malignancies.1 It is a highly aggressive form of salivary gland carcinoma and is associated with a poor clinical outcome. The 3-year overall survival rate for stage I disease is 42% and only 23% for stage IV disease.2 Salivary duct carcinoma has a high rate of distant metastasis,3 but cases of cutaneous metastases are rare.3-8 Previously reported cases of SDC that metastasized to the skin originated from the parotid gland (n=6) and submandibular gland (n=1).3

The diagnosis of cutaneous metastases is challenging due to the variability of the skin manifestations. Three cases described small firm nodules in patients,3-5 while others presented with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles.6-8 Our patient presented with sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules, which further emphasizes the capricious nature of skin findings.

The morphology of SDC is strikingly similar to ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast, which can lead to diagnostic confusion. Both carcinomas may show oncocytic cells, ductal formations, and cribriform structures with central comedo necrosis. Moreover, immunohistochemical features overlap, including positive staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. Positive immunohistochemistry with androgen receptor is consistent with SDC but also can be expressed in some cases of breast carcinoma.9,10 Therefore, the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement from metastatic SDC requires not just an evaluation of the pathologic features but careful attention to the clinical history and a thorough staging evaluation.

To the Editor:

Metastatic spread of salivary duct carcinoma (SDC) to the skin is rare. Diagnosing SDC can be challenging because the cutaneous manifestations of this disease are variable and include nodules, papules, and erysipelaslike inflammation (also known as shield sign) with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles. We describe a case of cutaneous metastatic SDC that originated from the parotid gland and presented with 2 distinct cutaneous findings: sharply demarcated erythematous plaques and focally hemorrhagic angiomatous papules.

A 60-year-old man presented with a persistent polymorphous pruritic eruption of several months’ duration involving the entire face, ears, neck, and upper chest. He had a history of unspecified adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland diagnosed 2 years prior and underwent multiple treatment cycles with several chemotherapeutic agents over the course of 18 months. Physical examination showed erythematous papules and nodules on the face and neck with slight overlying scale. Sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules were noted on the neck and chest (Figure 1). Two 4-mm punch biopsies were sampled from representative nodular areas. Histopathology showed multiple round solid-tumor nodules with central necrosis in the superficial and deep dermis that were not associated with the overlying epidermis (Figures 2A and 2B). The tumor cells appeared polygonal and contained ample eosinophilic cytoplasm. Tumor nuclei showed marked pleomorphism, and numerous atypical mitotic figures were readily identifiable (Figure 2C). There was diffuse cytoplasmic staining with cytokeratin 7 and nuclear staining with androgen receptor (Figure 2D). These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of SDC metastatic to the skin.

The patient underwent 8 cycles of docetaxel chemotherapy. With disease progression, the chemotherapy regimen was changed to gemcitabine and methotrexate. The patient continued to experience disease progression and died 9 months after diagnosis of skin metastases.

Salivary duct carcinoma is rare and is estimated to represent 1% to 3% of all salivary malignancies.1 It is a highly aggressive form of salivary gland carcinoma and is associated with a poor clinical outcome. The 3-year overall survival rate for stage I disease is 42% and only 23% for stage IV disease.2 Salivary duct carcinoma has a high rate of distant metastasis,3 but cases of cutaneous metastases are rare.3-8 Previously reported cases of SDC that metastasized to the skin originated from the parotid gland (n=6) and submandibular gland (n=1).3

The diagnosis of cutaneous metastases is challenging due to the variability of the skin manifestations. Three cases described small firm nodules in patients,3-5 while others presented with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles.6-8 Our patient presented with sharply demarcated, erythematous plaques studded with focally hemorrhagic, angiomatous papules, which further emphasizes the capricious nature of skin findings.

The morphology of SDC is strikingly similar to ductal adenocarcinoma of the breast, which can lead to diagnostic confusion. Both carcinomas may show oncocytic cells, ductal formations, and cribriform structures with central comedo necrosis. Moreover, immunohistochemical features overlap, including positive staining for cytokeratin 7 and gross cystic disease fluid protein 15. Positive immunohistochemistry with androgen receptor is consistent with SDC but also can be expressed in some cases of breast carcinoma.9,10 Therefore, the diagnosis of cutaneous involvement from metastatic SDC requires not just an evaluation of the pathologic features but careful attention to the clinical history and a thorough staging evaluation.

- D’heygere E, Meulemans J, Vander Poorten V. Salivary duct carcinoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26:142-151.

- Gilbert MR, Sharma A, Schmitt NC, et al. A 20-year review of 75 cases of salivary duct carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:489-495.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Andersen JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Tok J, Kao GF, Berberian BJ, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid adenocarcinoma. Report of a case with immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:303-306.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Hafiji J, Rytina E, Jani P, et al. A rare cutaneous presentation of metastatic parotid adenocarcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:E40-E42.

- Zanca A, Ferracini U, Bertazzoni MG. Telangiectatic metastasis from ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:113-114.

- Brys´ M, Wójcik M, Romanowicz-Makowska H, et al. Androgen receptor status in female breast cancer: RT-PCR and Western blot studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:85-90.

- Udager AM, Chiosea SI. Salivary duct carcinoma: an update on morphologic mimics and diagnostic use of androgen receptor immunohistochemistry. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:288-294.

- D’heygere E, Meulemans J, Vander Poorten V. Salivary duct carcinoma. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26:142-151.

- Gilbert MR, Sharma A, Schmitt NC, et al. A 20-year review of 75 cases of salivary duct carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2016;142:489-495.

- Chakari W, Andersen L, Andersen JL. Cutaneous metastases from salivary duct carcinoma of the submandibular gland. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017;9:254-258.

- Tok J, Kao GF, Berberian BJ, et al. Cutaneous metastasis from a parotid adenocarcinoma. Report of a case with immunohistochemical findings and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 1995;17:303-306.

- Aygit AC, Top H, Cakir B, et al. Salivary duct carcinoma of the parotid gland metastasizing to the skin: a case report and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2005;27:48-50.

- Cohen PR, Prieto VG, Piha-Paul SA, et al. The “shield sign” in two men with metastatic salivary duct carcinoma to the skin: cutaneous metastases presenting as carcinoma hemorrhagiectoides. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2012;5:27-36.

- Hafiji J, Rytina E, Jani P, et al. A rare cutaneous presentation of metastatic parotid adenocarcinoma. Australas J Dermatol. 2013;54:E40-E42.

- Zanca A, Ferracini U, Bertazzoni MG. Telangiectatic metastasis from ductal carcinoma of the parotid gland. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28:113-114.

- Brys´ M, Wójcik M, Romanowicz-Makowska H, et al. Androgen receptor status in female breast cancer: RT-PCR and Western blot studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128:85-90.

- Udager AM, Chiosea SI. Salivary duct carcinoma: an update on morphologic mimics and diagnostic use of androgen receptor immunohistochemistry. Head Neck Pathol. 2017;11:288-294.

Practice Points

- Skin manifestations of metastatic salivary duct carcinoma can be variable, ranging from nodules to erysipelaslike inflammation (also known as shield sign) with purpuric papules and pseudovesicles.

- The specific clinical findings as well as histologic and immunohistochemical characteristics can aid in the diagnosis of this rare disease.

Postirradiation Pseudosclerodermatous Panniculitis: A Rare Complication of Megavoltage External Beam Radiotherapy

To the Editor:

Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis (PIPP) is a rarely reported complication of megavoltage external beam radiotherapy that was first identified in 1993 by Winkelmann et al.1 The condition presents as an erythematous or hyperpigmented indurated plaque at a site of prior radiotherapy. Lesions caused by PIPP most commonly arise several months after treatment, although they may emerge up to 17 years following exposure.2 Herein, we report a rare case of a patient with PIPP occurring on the leg who previously had been treated for Kaposi sarcoma.

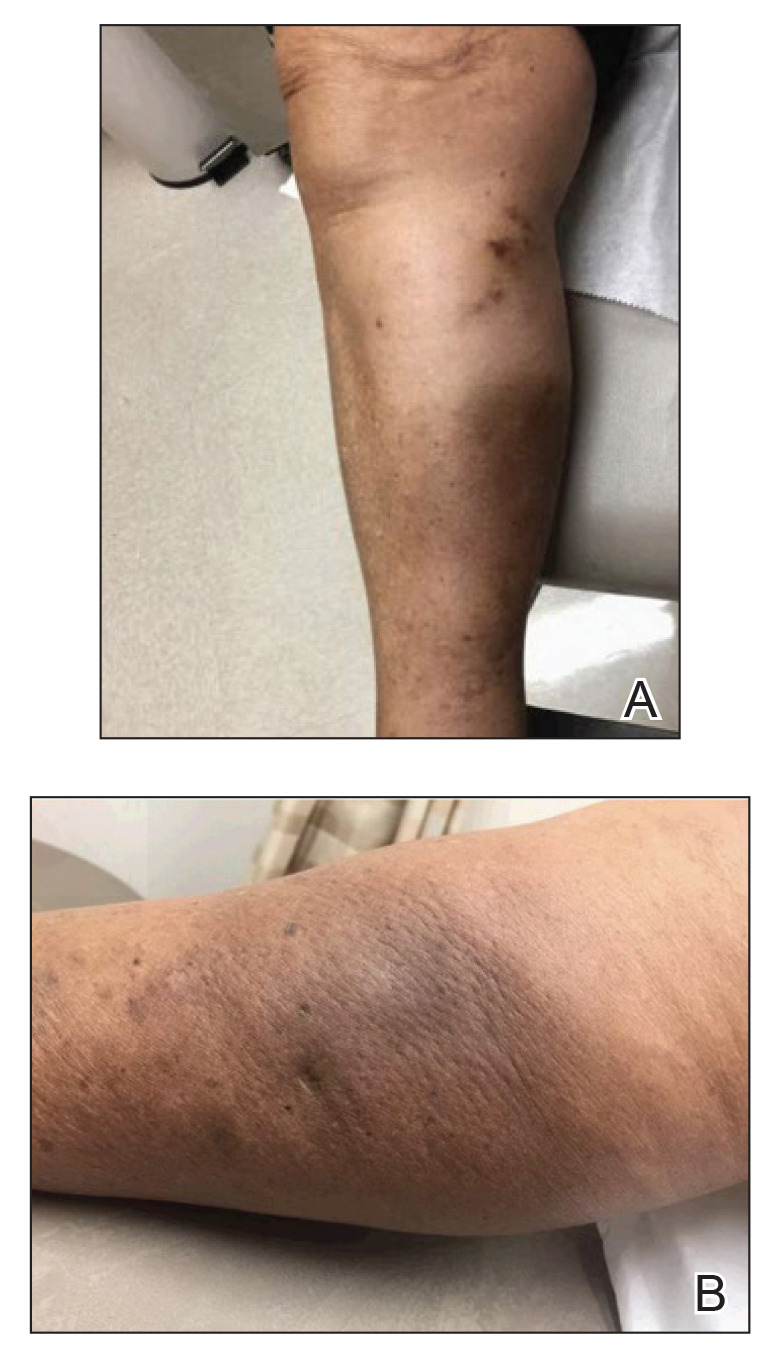

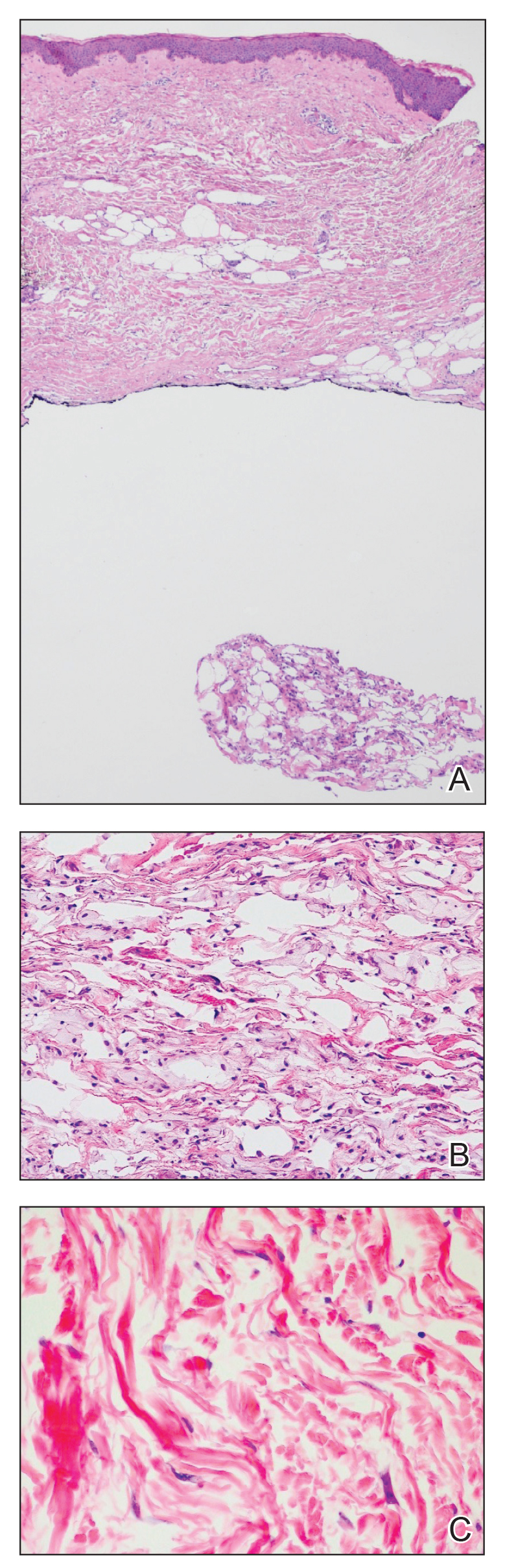

An 84-year-old woman presented with a tender plaque on the right lower leg of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for Kaposi sarcoma, with multiple sites on the body treated with megavoltage external beam radiotherapy during the prior 4 years. The most recent treatment occurred 8 months prior to presentation, at which time she had undergone radiotherapy for lesions on the posterior lower right leg. Physical examination demonstrated a hyperpigmented and indurated plaque at the treatment site (Figure 1). Skin biopsy results showed a mildly sclerotic dermis with atypical radiation fibroblasts scattered interstitially between collagen bundles, and a lobular panniculitis with degenerated adipocytes and foamy histiocytes (Figure 2). Hyalinized dermal vessels also were present. Based on the constellation of these biopsy findings, a diagnosis of PIPP was made.

The diagnosis of PIPP is challenging and invariably requires histologic examination. Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes cutaneous metastasis of the primary neoplasm, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic radiation dermatitis.

Histologically, PIPP is characterized by a lobular panniculitis without vasculitis. Typical findings include the presence of centrilobular necrotic adipocytes along with a foamy histiocytic infiltrate containing lipophagic granulomas at the periphery of the fat lobules. Septal thickening and sclerosis around fat lobules also have been described, and dermal changes associated with chronic radiation dermatitis, such as papillary dermal sclerosis, endothelial swelling, vascular hyaline arteriosclerosis, and atypical star-shaped radiation fibroblasts, may be present.2 Features of radiation-induced vasculopathy commonly are seen, although the appearance of these features varies over time. Intimal injury and mural thrombosis can develop within 5 years of radiation therapy, fibrosis of the vessel wall can occur within 10 years of radiation therapy, and atherosclerosis and periarterial fibrosis can appear within 20 years of radiation therapy.2,3 The histologic findings in our patient showed characteristic dermal findings seen in radiation dermatitis in addition to a lobular panniculitis with foamy histiocytes and mild vessel damage.

In contrast, lipodermatosclerosis is a septal and lobular panniculitis with septal fibrosis. Membranocystic fat necrosis is present, characterized by fat microcysts lined by feathery eosinophilic material. Stasis changes in the dermis and epidermis are accompanied by a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Patients with traumatic panniculitis, which also may enter the clinical differential diagnosis of PIPP, often demonstrate nonspecific histologic changes. Early lesions show a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages. Evolving lesions show variably sized fat microcysts surrounded by histiocytes, in addition to possible calcifications and a foreign-body giant cell reaction. A fibrous capsule may develop, surrounding the fat necrosis to form a mobile encapsulated lipoma. Late lesions frequently demonstrate lipomembranous changes and calcium deposits.4

To date, nearly all cases of PIPP in the literature have been described in breast cancer patients.1,2,5,6 However, Sandoval et al7 reported a case of PIPP occurring in the leg of a patient after radiotherapy for a soft tissue sarcoma. Similar to our patient, this patient presented with a painful, dully erythematous, indurated plaque, although her symptoms arose 5 years after radiotherapy.

Megavoltage external beam radiotherapy has become a widely used modality in the treatment of various cancers. As such, PIPP may represent an underdiagnosed condition with potential cases remaining unidentified when the clinical differential diagnosis does not lead to biopsy. Effective therapies have yet to be widely reported, and our patient failed to experience notable improvement with either topical or intralesional corticosteroids. Further studies are needed in order to address this knowledge gap.

- Winkelmann RK, Grado GL, Quimby SR, et al. Pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis after irradiation: an unusual complication of megavoltage treatment of breast carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:122-127.

- Pielasinski U, Machan S, Camacho D, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis: three new cases with additional histopathologic features supporting the radiotherapy etiology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:129-134.

- Butler MJ, Lane RH, Webster JH. Irradiation injury to large arteries. Br J Surg. 1980;67:341-343. Moreno A, Marcoval J, Peyri J. Traumatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:481-483.

- Shirsat HS, Walsh NM, McDonald LJ, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis with involvement of breast parenchyma: a dramatic example of a rare entity and a pitfall in diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:444-450.

- Carrasco L, Moreno C, Pastor MA, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:283-287.

- Sandoval M, Giesen L, Cataldo K, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis of the leg: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:587-589.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis (PIPP) is a rarely reported complication of megavoltage external beam radiotherapy that was first identified in 1993 by Winkelmann et al.1 The condition presents as an erythematous or hyperpigmented indurated plaque at a site of prior radiotherapy. Lesions caused by PIPP most commonly arise several months after treatment, although they may emerge up to 17 years following exposure.2 Herein, we report a rare case of a patient with PIPP occurring on the leg who previously had been treated for Kaposi sarcoma.

An 84-year-old woman presented with a tender plaque on the right lower leg of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for Kaposi sarcoma, with multiple sites on the body treated with megavoltage external beam radiotherapy during the prior 4 years. The most recent treatment occurred 8 months prior to presentation, at which time she had undergone radiotherapy for lesions on the posterior lower right leg. Physical examination demonstrated a hyperpigmented and indurated plaque at the treatment site (Figure 1). Skin biopsy results showed a mildly sclerotic dermis with atypical radiation fibroblasts scattered interstitially between collagen bundles, and a lobular panniculitis with degenerated adipocytes and foamy histiocytes (Figure 2). Hyalinized dermal vessels also were present. Based on the constellation of these biopsy findings, a diagnosis of PIPP was made.

The diagnosis of PIPP is challenging and invariably requires histologic examination. Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes cutaneous metastasis of the primary neoplasm, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic radiation dermatitis.

Histologically, PIPP is characterized by a lobular panniculitis without vasculitis. Typical findings include the presence of centrilobular necrotic adipocytes along with a foamy histiocytic infiltrate containing lipophagic granulomas at the periphery of the fat lobules. Septal thickening and sclerosis around fat lobules also have been described, and dermal changes associated with chronic radiation dermatitis, such as papillary dermal sclerosis, endothelial swelling, vascular hyaline arteriosclerosis, and atypical star-shaped radiation fibroblasts, may be present.2 Features of radiation-induced vasculopathy commonly are seen, although the appearance of these features varies over time. Intimal injury and mural thrombosis can develop within 5 years of radiation therapy, fibrosis of the vessel wall can occur within 10 years of radiation therapy, and atherosclerosis and periarterial fibrosis can appear within 20 years of radiation therapy.2,3 The histologic findings in our patient showed characteristic dermal findings seen in radiation dermatitis in addition to a lobular panniculitis with foamy histiocytes and mild vessel damage.

In contrast, lipodermatosclerosis is a septal and lobular panniculitis with septal fibrosis. Membranocystic fat necrosis is present, characterized by fat microcysts lined by feathery eosinophilic material. Stasis changes in the dermis and epidermis are accompanied by a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Patients with traumatic panniculitis, which also may enter the clinical differential diagnosis of PIPP, often demonstrate nonspecific histologic changes. Early lesions show a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages. Evolving lesions show variably sized fat microcysts surrounded by histiocytes, in addition to possible calcifications and a foreign-body giant cell reaction. A fibrous capsule may develop, surrounding the fat necrosis to form a mobile encapsulated lipoma. Late lesions frequently demonstrate lipomembranous changes and calcium deposits.4

To date, nearly all cases of PIPP in the literature have been described in breast cancer patients.1,2,5,6 However, Sandoval et al7 reported a case of PIPP occurring in the leg of a patient after radiotherapy for a soft tissue sarcoma. Similar to our patient, this patient presented with a painful, dully erythematous, indurated plaque, although her symptoms arose 5 years after radiotherapy.

Megavoltage external beam radiotherapy has become a widely used modality in the treatment of various cancers. As such, PIPP may represent an underdiagnosed condition with potential cases remaining unidentified when the clinical differential diagnosis does not lead to biopsy. Effective therapies have yet to be widely reported, and our patient failed to experience notable improvement with either topical or intralesional corticosteroids. Further studies are needed in order to address this knowledge gap.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis (PIPP) is a rarely reported complication of megavoltage external beam radiotherapy that was first identified in 1993 by Winkelmann et al.1 The condition presents as an erythematous or hyperpigmented indurated plaque at a site of prior radiotherapy. Lesions caused by PIPP most commonly arise several months after treatment, although they may emerge up to 17 years following exposure.2 Herein, we report a rare case of a patient with PIPP occurring on the leg who previously had been treated for Kaposi sarcoma.

An 84-year-old woman presented with a tender plaque on the right lower leg of 2 months’ duration. Her medical history was remarkable for Kaposi sarcoma, with multiple sites on the body treated with megavoltage external beam radiotherapy during the prior 4 years. The most recent treatment occurred 8 months prior to presentation, at which time she had undergone radiotherapy for lesions on the posterior lower right leg. Physical examination demonstrated a hyperpigmented and indurated plaque at the treatment site (Figure 1). Skin biopsy results showed a mildly sclerotic dermis with atypical radiation fibroblasts scattered interstitially between collagen bundles, and a lobular panniculitis with degenerated adipocytes and foamy histiocytes (Figure 2). Hyalinized dermal vessels also were present. Based on the constellation of these biopsy findings, a diagnosis of PIPP was made.

The diagnosis of PIPP is challenging and invariably requires histologic examination. Clinically, the differential diagnosis includes cutaneous metastasis of the primary neoplasm, cellulitis, lipodermatosclerosis, morphea, and chronic radiation dermatitis.

Histologically, PIPP is characterized by a lobular panniculitis without vasculitis. Typical findings include the presence of centrilobular necrotic adipocytes along with a foamy histiocytic infiltrate containing lipophagic granulomas at the periphery of the fat lobules. Septal thickening and sclerosis around fat lobules also have been described, and dermal changes associated with chronic radiation dermatitis, such as papillary dermal sclerosis, endothelial swelling, vascular hyaline arteriosclerosis, and atypical star-shaped radiation fibroblasts, may be present.2 Features of radiation-induced vasculopathy commonly are seen, although the appearance of these features varies over time. Intimal injury and mural thrombosis can develop within 5 years of radiation therapy, fibrosis of the vessel wall can occur within 10 years of radiation therapy, and atherosclerosis and periarterial fibrosis can appear within 20 years of radiation therapy.2,3 The histologic findings in our patient showed characteristic dermal findings seen in radiation dermatitis in addition to a lobular panniculitis with foamy histiocytes and mild vessel damage.

In contrast, lipodermatosclerosis is a septal and lobular panniculitis with septal fibrosis. Membranocystic fat necrosis is present, characterized by fat microcysts lined by feathery eosinophilic material. Stasis changes in the dermis and epidermis are accompanied by a mild perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate.

Patients with traumatic panniculitis, which also may enter the clinical differential diagnosis of PIPP, often demonstrate nonspecific histologic changes. Early lesions show a perivascular infiltrate of lymphocytes and macrophages. Evolving lesions show variably sized fat microcysts surrounded by histiocytes, in addition to possible calcifications and a foreign-body giant cell reaction. A fibrous capsule may develop, surrounding the fat necrosis to form a mobile encapsulated lipoma. Late lesions frequently demonstrate lipomembranous changes and calcium deposits.4

To date, nearly all cases of PIPP in the literature have been described in breast cancer patients.1,2,5,6 However, Sandoval et al7 reported a case of PIPP occurring in the leg of a patient after radiotherapy for a soft tissue sarcoma. Similar to our patient, this patient presented with a painful, dully erythematous, indurated plaque, although her symptoms arose 5 years after radiotherapy.

Megavoltage external beam radiotherapy has become a widely used modality in the treatment of various cancers. As such, PIPP may represent an underdiagnosed condition with potential cases remaining unidentified when the clinical differential diagnosis does not lead to biopsy. Effective therapies have yet to be widely reported, and our patient failed to experience notable improvement with either topical or intralesional corticosteroids. Further studies are needed in order to address this knowledge gap.

- Winkelmann RK, Grado GL, Quimby SR, et al. Pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis after irradiation: an unusual complication of megavoltage treatment of breast carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:122-127.

- Pielasinski U, Machan S, Camacho D, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis: three new cases with additional histopathologic features supporting the radiotherapy etiology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:129-134.

- Butler MJ, Lane RH, Webster JH. Irradiation injury to large arteries. Br J Surg. 1980;67:341-343. Moreno A, Marcoval J, Peyri J. Traumatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:481-483.

- Shirsat HS, Walsh NM, McDonald LJ, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis with involvement of breast parenchyma: a dramatic example of a rare entity and a pitfall in diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:444-450.

- Carrasco L, Moreno C, Pastor MA, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:283-287.

- Sandoval M, Giesen L, Cataldo K, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis of the leg: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:587-589.

- Winkelmann RK, Grado GL, Quimby SR, et al. Pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis after irradiation: an unusual complication of megavoltage treatment of breast carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 1993;68:122-127.

- Pielasinski U, Machan S, Camacho D, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis: three new cases with additional histopathologic features supporting the radiotherapy etiology. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35:129-134.

- Butler MJ, Lane RH, Webster JH. Irradiation injury to large arteries. Br J Surg. 1980;67:341-343. Moreno A, Marcoval J, Peyri J. Traumatic panniculitis. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:481-483.

- Shirsat HS, Walsh NM, McDonald LJ, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis with involvement of breast parenchyma: a dramatic example of a rare entity and a pitfall in diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:444-450.

- Carrasco L, Moreno C, Pastor MA, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis. Am J Dermatopathol. 2001;23:283-287.

- Sandoval M, Giesen L, Cataldo K, et al. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis of the leg: report of a case and review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2015;37:587-589.

Practice Points

- Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis presents as an erythematous or indurated plaque at a site of prior radiotherapy.

- This rare entity may be underreported and requires biopsy for accurate diagnosis.