User login

Is There a Relationship Between Facility Peer Review Findings and Quality in the Veterans Health Administration?

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

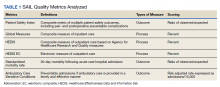

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

Hospital leaders report the most common aim of peer review (PR) is to improve quality and patient safety, thus it is a potentially powerful quality improvement (QI) driver.1 “When conducted systematically and credibly, peer review for quality management can result in both short-term and long-term improvements in patient care by revealing areas for improvement in the provision of care,” Veterans Health Administration (VHA) Directive 1190 states. “This ultimately contributes to organizational improvements.” At the same time, there are anecdotal concerns that PR may be used punitively and driven by case outcomes rather than by accepted best practices supporting QI.

Studies of the PR process suggest these concerns are valid. A key tenet of QI is standardization. PR is problematic in that regard; studies show poor interrater reliability for judgments on care, as well as hindsight bias—the fact that raters are strongly influenced by the outcome of care, not the process of care.2-5 There are concerns that case selection or review process when not standardized may be wielded as punitive too.6 In this study, we sought to identify the relationship between PR findings and subsequent institution quality metrics. If PR does lead to an improvement in quality, or if quality concerns are managed within the PR committee, it should be possible to identify a measurable relationship between the PR process and a facility’s subsequent quality measures.

A handful of studies describe the association between PR and quality of care. Itri and colleagues noted that random, not standardized PR in radiology does not achieve reductions in diagnostic error rate.7 However, adoption of just culture principles in PR resulted in a significant improvement in facility leaders’ self-reports of quality measures at surveyed institutions.8 The same author reported that increases in PR standardization and integration with performance improvement activities could explain up to 18% of objective quality measure variation.9

We sought to determine whether a specific aspect of the PR process, the PR committee judgment of quality of care by clinicians, was related to medical center quality in a cross-sectional study of 136 Veterans Health Administration (VHA) medical centers. The VHA is a good source of study because there are standardized PR processes and training for committee members and reviewers. Our hypothesis was that medical centers with a higher number of Level 2 (“most experienced and competent clinicians might have managed the case differently”) and Level 3 (“most experienced and competent providers would have managed the case differently”) PR findings would also have lower quality metric scores for processes and outcomes of care.

Methods

We used PR data from fiscal year 2018 and 2019. VHA PR data are available quarterly and are self-reported by each facility to the VHA Office of Clinical Risk Management. These data are broken down by facility. The following data, when available in both fiscal years 2018 and 2019, were used for this analysis: percent and number of PR that are ranked as level 1, 2, or 3; medical center group (MCG) acuity measure assigned by the VHA (1 is highest, 3 is lowest); and number of PR per 100,000 unique veteran encounters in 2019. Measures of facility quality are drawn from Strategic Analytics for Improvement and Learning (SAIL) data from 2019, which are available quarterly by facility and are rolling for 12 months. SAIL measures processes and outcomes of care. Table 1 indicates which measures are focused on outcomes vs quality processes.

SAS Version 9.2 was used to perform statistical analyses. We used Spearman correlation to estimate the PR and quality relationship.

Results

There were 136 facilities with 2 years of PR data available. The majority of these facilities (89) were highest complexity MCG 1 facilities; 19 were MCG 2, and 28 were MCG 3. Of 13,515 PRs, most of the 9555 PR findings were level 1 (70.7%). The between-facility range of level 2 and 3 findings was large, varying from 3.5% to nearly 70% in 2019 (Table 2). Findings were similar in 2018; facilities level 2 and 3 ratings ranged from 3.6% to 73.5% of all PR findings.

There was no correlation between most quality measures and facility PR findings (Table 3). The only exception was for Global Measures (GM90), an inpatient process of care measure. Unexpectedly, the correlation was positive—facilities with a higher percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings had better inpatient processes of care SAIL score. The strongest correlation was between 2018 and 2019 PR findings.

Discussion

We hypothesized that a high percentage of level 2 and 3 PR findings would be negatively associated with objective facility measures of care processes in SAIL but we did not see this association. The only quality measure associated with PR findings was GM90, a score of inpatient care processes. However, the association was positive, with better performance associated with more level 2 and 3 PR findings.

The best predictor of the proportion of a facility’s PR findings is the previous year’s PR findings. With an R = 0.59, the previous year findings explain about 35% of the variability in level assignment. Our analysis may describe a new bias in PR, in which committees consistently assign either low or high proportions of level 2 and 3 findings. This correlation could be due to individual PR committee culture or composition, but it does not relate to objective quality measures.

Strengths

For this study we use objective measures of PR processes, the assignment of levels of care.

Limitations

Facilities self-report PR outcomes, so there could be errors in reporting. In addition, this study was cross sectional and not longitudinal and it is possible that change in quality measures over time are correlated with PR findings. Future studies using the VHA PR and SAIL data could evaluate whether changes over time, and perhaps in response to level 2 and 3 findings, would be a more sensitive indicator of the impact of the PR process on quality metrics. Future studies could incorporate the relationship between findings from the All Employee Survey, which is conducted annually, such as psychologic safety, as well as the distance the facility has gone on the high reliability organization journey, with PR findings and SAIL metrics. Finally, PR is focused on the practice of an individual clinician, while SAIL quality metrics reflect facility performance. Interventions possibly stay at the clinician level and do not drive subsequent QI processes.

What does this mean for PR? Since the early 1990s, there have been exhortations from experts to improve PR, by adopting a QI model, or for a deeper integration of PR and QI.1,2,10 Just culture tools, which include QI, are promoted as a means to improve PR.8,11,12 Other studies show PR remains problematic in terms of standardization, incorporation of best practices, redesigning systems of care, or demonstrable improvements to facility safety and care quality.1,4,6,8 Several publications have described interventions to improve PR. Deyo-Svedson discussed a program with standardized training and triggers, much like VHA.13 Itri and colleagues standardized PR in radiology to target areas of known diagnostic error, as well as use the issues assessed in PR to perform QI and education. One example of a successful QI effort involved changing the radiology reporting template to make sure areas that are prone to diagnostic error are addressed.7

Conclusions

Since 35% of PR level variance is correlated with prior year’s results, PR committees should look at increased standardization in reviews and findings. We endorse a strong focus on standardization, application of just culture tools to case reviews, and tighter linkage between process and outcome metrics measured by SAIL and PR case finding. Studies should be performed to pilot interventions to improve the linkage between PR and quality, so that greater and faster gains can be made in quality processes and, leading from this, outcomes. Additionally, future research should investigate why some facilities consistently choose higher or lower PR ratings.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Dr. George “Web” Ross for his helpful edits.

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113

1. Edwards MT. In pursuit of quality and safety: an 8-year study of clinical peer review best practices in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2018;30(8):602-607. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzy069

2. Dans PE. Clinical peer Review: burnishing a tarnished icon. Ann Intern Med. 1993;118(7):566-568. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-118-7-199304010-00014

3. Goldman RL. The reliability of peer assessments of quality of care. JAMA. 1992;267(7):958-960. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03480070074034

4. Swaroop R. Disrupting physician clinical practice peer review. Perm J. 2019;23:18-207. doi:10.7812/TPP/18-207

5. Caplan RA, Posner KL, Cheney FW. Effect of outcome on physician judgments of appropriateness of care. JAMA. 1991;265(15):1957–1960. doi:10.1001/jama.1991.03460150061024

6. Vyas D, Hozain AE. Clinical peer review in the United States: history, legal development and subsequent abuse. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(21):6357-6363. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i21.6357

7. Itri JN, Donithan A, Patel SH. Random versus nonrandom peer review: a case for more meaningful peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2018;15(7):1045-1052. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.03.054

8. Edwards MT. An assessment of the impact of just culture on quality and safety in US hospitals. Am J Med Qual. 2018; 33(5):502-508. doi:10.1177/1062860618768057

9. Edwards MT. The objective impact of clinical peer review on hospital quality and safety. Am J Med Qual. 2011;26(2);110-119. doi:10.1177/1062860610380732

10. Berwick DM. Peer review and quality management: are they compatible?. QRB Qual Rev Bull. 1990;16(7):246-251. doi:10.1016/s0097-5990(16)30377-3

11. Volkar JK, Phrampus P, English D, et al. Institution of just culture physician peer review in an academic medical center. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(7):e689-e693. doi:10.1097/PTS.0000000000000449

12. Burns J, Miller T, Weiss JM, Erdfarb A, Silber D, Goldberg-Stein S. Just culture: practical implementation for radiologist peer review. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019;16(3):384-388. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2018.10.021

13. Deyo-Svendsen ME, Phillips MR, Albright JK, et al. A systematic approach to clinical peer review in a critical access hospital. Qual Manag Health Care. 2016;25(4):213-218. doi:10.1097/QMH.0000000000000113