User login

Self-mutilation after recent-onset psychosis

CASE Bleeding, bewildered

Mr. K, age 23, a South Asian male, is discovered in the bathroom bleeding profusely. Mr. K’s parents inform emergency medical services (EMS) personnel that Mr. K is “not in his right mind” and speculate that he is depressed. EMS personnel find Mr. K sitting in a pool of blood in the bathtub, holding a cloth over his pubic area and complaining of significant pain. They estimate that Mr. K has lost approximately 1 L of blood. Cursory evaluation reveals that his penis is severed; no other injuries or lacerations are notable. Mr. K states, “I did not want it anymore.” A kitchen knife that he used to self-amputate is found nearby. He is awake, alert, and able to follow simple directives.

In the emergency room, Mr. K is in mild-to-moderate distress. He has no history of medical illness, but his parents report that he previously required psychiatric treatment. Mr. K is not able to elaborate. He reluctantly discloses an intermittent history of Cannabis use. Physical examination reveals tachycardia (heart rate: 115 to 120 beats per minute), and despite blood loss, systolic hypertension (blood pressure: 142/70 to 167/70 mm Hg). His pulse oximetry is 97% to 99%; he is afebrile. Laboratory tests are notable for anemia (hemoglobin, 7.2 g/dL [reference range, 14.0 to 17.5 g/dL]; hematocrit, 21.2% [reference range, 41% to 50%]) and serum toxicology screen is positive for benzodiazepines, which had been administered en route to allay his distress.

Mr. K continues to hold pressure on his pubic area. When pressure is released, active arterial spurting of bright red blood is notable. Genital examination reveals a cleanly amputated phallus. Emergent surgical intervention is required to stop the hemorrhage and reattach the penis. Initially, Mr. K is opposed to reattachment, but after a brief discussion with his parents, he consents to surgery. Urology and plastic surgery consultations are elicited to perform the microvascular portion of the procedure.

[polldaddy:9881368]

The authors’ observations

Self-injurious behaviors occur in approximately 1% to 4% of adults in the United States, with chronic and severe self-injury occurring among approximately 1% of the U.S. population.1,2 Intentional GSM is a relatively rare catastrophic event that is often, but not solely, associated with severe mental illness. Because many cases go unreported, the prevalence of GSM is difficult to estimate.3,4 Although GSM has been described in both men and women, the literature has predominantly focused on GSM among men.5 Genital self-injury has been described in several (ie, ethnic/racial and religious) contexts and has been legally sanctioned.6-8

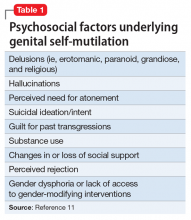

Psychiatric disorders associated with, and precipitating factors underlying, GSM have long remained elusive.8 GSM has been described in case reports and small case series in both psychiatric and urologic literature. These reports provide incomplete descriptions of the diagnostic conditions and psychosocial factors underlying male GSM.

A recent systematic review of 173 cases of men who engaged in GSM published in the past 115 years (since the first case of GSM was published in the psychiatric literature9) revealed that having some form of psychopathology elevates the probability of GSM10,11; rarely the individual did not have a psychiatric condition.11-17 Nearly one-half of the men had psychosis; most had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis. Other psychiatric conditions associated with GSM include personality disorders, substance use disorder, and gender dysphoria. GSM is rarely associated with anxiety or mood disorders.

GSM is a heterogeneous form of self-injury that ranges from superficial genital lacerations, amputation, or castration to combinations of these injuries. Compared with individuals with other psychiatric disorders, a significantly greater proportion of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders engage in self-amputation (auto-penectomy). By contrast, persons with gender dysphoria tend to engage in self-castration at significantly higher rates than those with other psychiatric conditions.11 Despite these trends, clinicians should not infer a specific psychiatric diagnosis based on the severity or type of self-inflicted injury.

HISTORY Command hallucinations

Postoperatively, Mr. K is managed in the trauma intensive care unit. During psychiatric consultation, Mr. K demonstrates a blunted affect. His speech is low in volume but clear and coherent. His thoughts are generally linear for specific lines of inquiry (eg, about perceived level of pain) but otherwise are impoverished. Mr. K often digresses into repetitively mumbled prayers. He appears distracted, as if responding to internal stimuli. Although he acknowledges the GSM, he does not discuss the factors underlying his decision to proceed with auto-penectomy. Over successive evaluations, he reluctantly discloses that he had been experiencing disparaging auditory hallucinations that told him that his penis “was too small” and commanded him to “cut it off.”

Psychiatric history reveals that Mr. K required psychiatric hospitalization 7 months earlier due to new-onset auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and thought disorganization, in the context of daily Cannabis use. At the time, the differential diagnosis included new-onset schizophrenia and substance-induced psychosis. His symptoms improved quickly with risperidone, 2 mg/d, and he was discharged in a stable condition with referrals for outpatient care. Mr. K admits he had stopped taking risperidone several weeks before the GSM because he was convinced that he had been cured. At that time, Mr. K had told his parents he was no longer required to take medication or engage in outpatient psychiatric treatment, and they did not question this. Mr. K struggled to sustain part-time employment (in a family business), having taken a leave of absence from graduate school after his first hospitalization. He continued to use Cannabis regularly but denies being intoxicated at the time of the GSM. Throughout his surgical hospitalization, Mr. K’s thoughts remain disorganized. He denies that the GSM was a suicide attempt or having current suicidal thoughts, intent, or plans. He also denies having religious preoccupations, over-valued religious beliefs, or delusions.

Mr. K identifies as heterosexual, and denies experiencing distress related to sexual orientation or gender identity or guilt related to sexual impulses or actions. He also denies having a history of trauma or victimization and does not report any symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder or body dysmorphic disorder.

The authors’ observations

Little is known about how many individuals who engage in GSM eventually complete suicide. Although suicidal ideation and intent have been infrequently associated with GSM, suicide has been most notably reported among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and psychotic mood disorders.11,18,23-26 For these individuals, suicidal ideation co-occurred with delusions, hallucinations, and pathological guilt preoccupations. Significant self-inflicted injury can be harbinger of distress that could lead to suicide if not optimally treated. Other psychosocial stressors, such as disruptions in interpersonal functioning arising from changes in or loss of social support or perceived rejection, may contribute to a patient’s level of distress, complicating underlying psychiatric disturbances and increasing vulnerability toward GSM.11,27

Substance use also increases vulnerability toward GSM.11,18,24,28 As is the case with patients who engage in various non-GSM self-injurious behaviors,29,30 substance use or intoxication likely contribute to disinhibition or a dissociative state, which enables individuals to engage in self-injury.30

A lack of access to treatment is a rare precipitant for GSM, except among individuals with gender dysphoria. Studies have found that many patients with gender dysphoria who performed self-castration did so in a premeditated manner with low suicidal intent, and the behavior often was related to a lack of or refusal for gender confirmation surgery.31-34

In the hospital setting, surgical/urological interventions need to be directed at the potentially life-threatening sequelae of self-injury. Although complications vary, depending on the type of injury incurred, urgent measures are needed to manage blood loss because hemorrhage can be fatal.23,35,36 Other consequences that can arise include urinary fistulae, urethral strictures, mummification of the glans penis, and development of sensory abnormalities after repair of the injured tissues or reattachment.8 More superficial injuries may require only hemostasis and simple suturing, whereas extensive injuries, such as complete amputation, can be addressed through microvascular techniques.

The psychiatrist’s role. The psychiatrist should act as an advocate for the GSM patient to create an environment conducive to healing. A patient who is experiencing hallucinations or delusions may feel overwhelmed by medical and familial attention. Pharmacologic treatment for prevailing mental illness, such as psychosis, should be initiated in the inpatient setting. An estimated 20% to 25% of those who self-inflict genital injury may repeatedly mutilate their genitals.19,28 Patients unduly influenced by command hallucinations, delusional thought processes, mood disturbances, or suicidal ideation may attempt to complete the injury, or reinjure themselves after surgical/urological intervention, which may require safety measures, such as 1:1 observation, restraints, or physical barriers, to prevent reinjury.37

Self-injury elicits strong, emotional responses from health care professionals, including fascination, apprehension, and hopelessness. Psychiatrists who care for such patients should monitor members of the patient’s treatment team for psychological reactions. In addition, the patient’s behavior while hospitalized may stir feelings of retaliation, anger, fear, and frustration.11,24,37 Collaborative relationships with medical and surgical specialties can help staff manage emotional reactions and avoid the inadvertent expression of those feelings in their interactions with the patient; these reactions might otherwise undermine treatment.24,34 Family education can help mitigate any guilt family members may harbor for not preventing the injury.37

Although efforts to understand the intended goal(s) and precipitants of the self-injury are likely to be worthwhile, the overwhelming distress associated with GSM and its emergent treatment may preclude intensive exploration.

TREATMENT Restarting medication

While on the surgical unit, Mr. K is restarted on risperidone, 2 mg/d. He appears to tolerate the medication without adverse effects. However, because Mr. K continues to experience auditory hallucinations, and the treatment team remains concerned that he might again experience commands to harm himself, he is transferred to an acute psychiatric inpatient setting.

Urology follow-up reveals necrosis/mummification of the replanted penis and an open scrotal wound. After discussing options with the patient and family, the urologist transfers Mr. K back to the surgical unit for wound closure and removal of the replanted penis. A urethrostomy is performed to allow for bladder emptying.

[polldaddy:9881371]

The authors’ observations

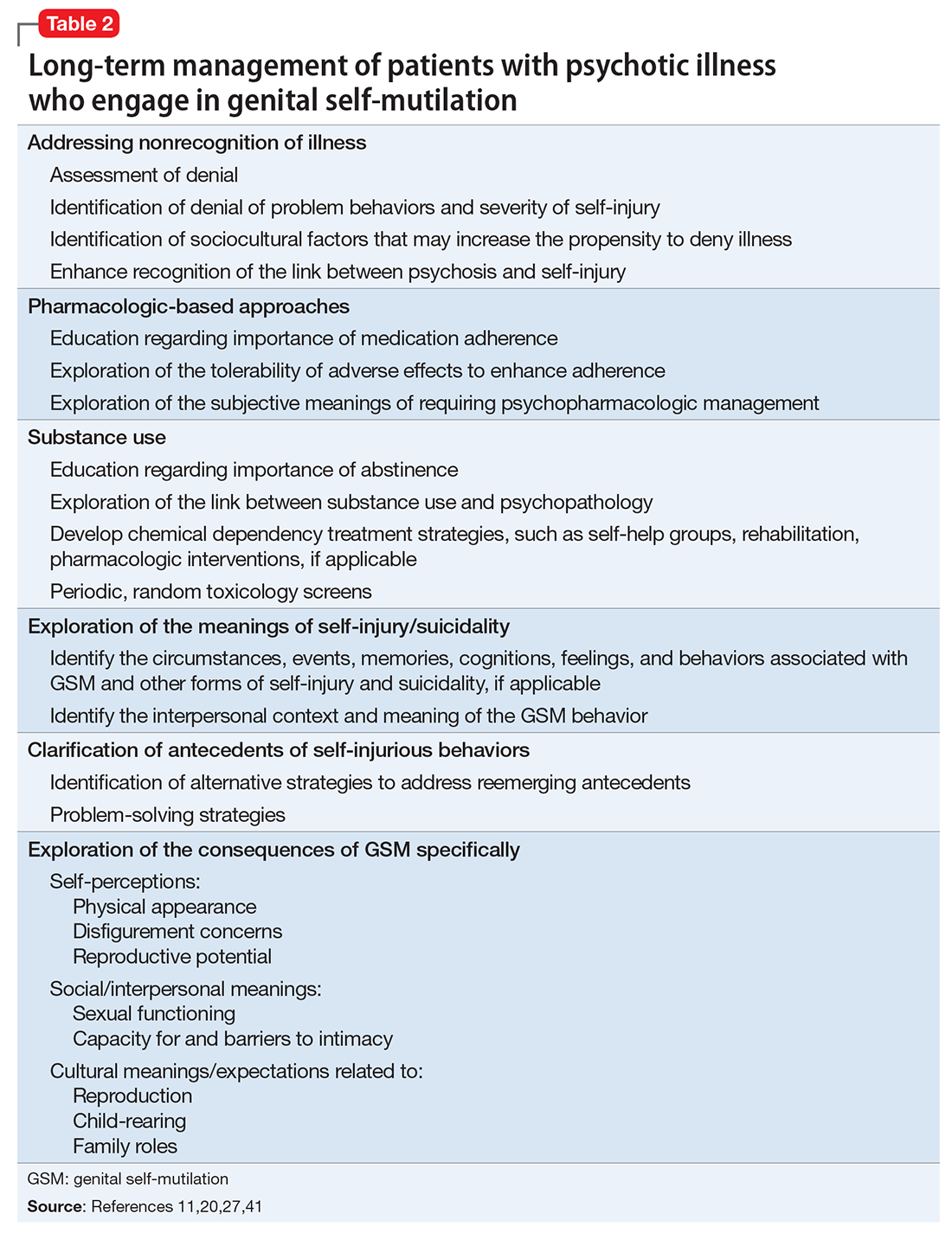

Because most published case reports of GSM among men have focused on acute treatment, there is a dearth of literature available on the long-term course of GSM to inform treatment strategies. Because recovery is a non-static process and a patient’s reactions to his injury will likely evolve over time, a multifaceted approach invoking psychiatric and psychotherapeutic interventions is necessary to help patients after initial injury and surgical management37,40-43 (Table 211,20,27,41).

OUTCOME Return to school, work

Mr. K is discharged with close follow-up at a specialized clinic for new-onset psychosis. Post-discharge treatment consists of education about the course of schizophrenia and the need for medication adherence to prevent relapse. Mr. K also is educated on the relationship between Cannabis use and psychosis, and he abstains from illicit substance use. Family involvement is encouraged to help with medication compliance and monitoring for symptom reemergence.

Therapy focuses on exploring the antecedents of the auto-penectomy, Mr. K’s body image issue concerns, and his feelings related to eventual prosthesis implantation. He insists that he cannot recall any precipitating factors for his self-injury other than the command hallucinations. He does not report sexual guilt, although he had been sexually active with his girlfriend in the months prior to his GSM, which goes against his family’s religious beliefs. He reports significant regret and shame for the self-mutilation, and blames himself for not informing family members about his hallucinations. Therapy involves addressing his attribution of blame using cognitive techniques and focuses on measures that can be taken to prevent further self-harm. Efforts are directed at exploring whether cultural and religious traditions impacted the therapeutic alliance, medication adherence, self-esteem and body image, sexuality, and future goals. Over the course of 1 year, he resumes his graduate studies and part-time work, and explores prosthetic placement for cosmetic purposes.

The authors’ observations

Research suggests that major self-mutilation among patients with psychotic illness is likely to occur during the first episode or early in the course of illness and/or with suboptimal treatment.44,45 Mr. K was enlisted in an intensive outpatient treatment program involving biweekly psychotherapy sessions and psychiatric follow-up. Initial sessions focused on education regarding the importance of medication adherence and exploration of signs and symptoms that might suggest reemergence of a psychotic decompensation. The psychiatrist monitored Mr. K closely to ensure he was able to tolerate his medications to mitigate the possibility that adverse effects would undermine adherence. Mr. K’s reactions to having a psychiatric illness also were explored because of concerns that such self-appraisals might trigger shame, embarrassment, denial, and other responses that might undermine treatment adherence. His family members were apprised of treatment goals and enlisted to foster adherence with medication and follow-up appointments.

Mr. K’s Cannabis use was addressed because ongoing use likely had a negative impact on his schizophrenia (ie, a greater propensity toward relapse and rehospitalization and a poorer therapeutic response to antipsychotic medication).46,47 He was strongly encouraged to avoid Cannabis and other illicit substances.

Psychiatrists can help in examining the meaning behind the injury while helping the patient to adapt to the sequelae and cultivate skills to meet functional demands.41 Once Mr. K’s psychotic symptoms were in remission, treatment began to address the antecedents of the GSM, as well as the resultant physical consequences. It was reasonable to explore how Mr. K now viewed his actions, as well as the consequences that his actions produced in terms of his physical appearance, sexual functioning, capacity for sexual intimacy, and reproductive potential. It was also important to recognize how such highly intimate and deeply personal self-schema are framed and organized against his cultural and religious background.27,33

Body image concerns and expectations for future urologic intervention also should be explored. Although Mr. K was not averse to such exploration, he did not spontaneously address such topics in great depth. The discussion was unforced and effectively left open as an issue that could be explored in future sessions.

1. Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):609-620.

2. Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: prevalence and psychological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1501-1508.

3. Krasucki C, Kemp R, David A. A case study of female genital self-mutilation in schizophrenia. Br J Med Psychol. 1995;68(pt 2):179-186.

4. Lennon S. Genital self-mutilation in acute mania. Med J Aust. 1963;50(1):79-81.

5. Schweitzer I. Genital self-amputation and the Klingsor syndrome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990;24(4):566-569.

6. Anumonye A. Self-inflicted amputation of the penis in two Nigerian males. Niger Med J. 1973;3(1):51-52.

7. Bowman KM, Crook GH. Emotional changes following castration. Psychiatr Res Rep Am Psychiatr Assoc. 1960;12:81-96.

8. Eke N. Genital self-mutilation: there is no method in this madness. BJU Int. 2000;85(3):295-298.

9. Stroch D. Self-castration. JAMA. 1901;36(4):270.

10. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a comprehensive review of psychiatric disorders. Poster presented at: Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 10, 2016.

11. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a systematic review of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:43-50.

12. Battle AO. The psychological appraisal of a patient who had performed self-castration. British Journal of Projective Psychology & Personality Study. 1973;18(2):5-17.

13. Bhatia MS, Arora S. Penile self-mutilation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(1):86-87.

14. Gleeson MJ, Connolly J, Grainger R. Self-castration as treatment for alopecia. Br J Urol. 1993;71(5):614-615.

15. Hendershot E, Stutson AC, Adair TW. A case of extreme sexual self-mutilation. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55(1):245-247.

16. Hermann M, Thorstenson A. A rare case of male‐to‐eunuch gender dysphoria. Sex Med. 2015;3(4):331-333.

17. Nerli RB, Ravish IR, Amarkhed SS, et al. Genital self-mutilation in nonpsychotic heterosexual males: case report of two cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50(4):285-287.

18. Blacker KH, Wong N. Four cases of autocastration. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;8:169-176.

19. Catalano G, Catalano MC, Carroll KM. Repetitive male genital self-mutilation: a case report and discussion of possible risk factors. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(1):27-37.

20. Martin T, Gattaz WF. Psychiatric aspects of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1991;24(3):170-178.

21. Money J. The Skoptic syndrome: castration and genital self-mutilation as an example of sexual body-image pathology. J Psychol Human Sex. 1988;1(1):113-128.

22. Nakaya M. On background factors of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1996;29(4):242-248.

23. Borenstein A, Yaffe B, Seidman DS, et al. Successful microvascular replantation of an amputated penis. Isr J Med Sci. 1991;27(7):395-398.

24. Greilsheimer H, Groves JE. Male genital self-mutilation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(4):441-446.

25. Mendez R, Kiely WF, Morrow JW. Self-emasculation. J Urol. 1972;107(6):981-985.

26. Siddique RA, Deshpande S. A case of genital self-mutilation in a patient with psychosis. German J Psychiatry. 2007;10(1):25-28.

27. Qureshi NA. Male genital self-mutilation with special emphasis on the sociocultural meanings. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2009;14(2):178-181.

28. Romilly CS, Isaac MT. Male genital self-mutilation. Br J Hosp Med. 1996;55(7):427-431.

29. Gahr M, Plener PL, Kölle MA, et al. Self-mutilation induced by psychotropic substances: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):977-983.

30. Evren C, Sar V, Evren B, et al. Self-mutilation among male patients with alcohol dependency: the role of dissociation. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):489-495.

31. Brown GR. Autocastration and autopenectomy as surgical self-treatment in incarcerated persons with gender identity disorder. Int J Transgend. 2010;12(1):31-39.

32. Master VA, McAninch JW, Santucci RA. Genital self-mutilation and the Internet. J Urol. 2000;164(5):1656.

33. Premand NE, Eytan A. A case of non-psychotic autocastration: the importance of cultural factors. Psychiatry. 2005;68(2):174-178.

34. Simopoulos EF, Trinidad AC. Two cases of male genital self-mutilation: an examination of liaison dynamics. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):178-180.

35. Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, et al. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33(2):385-386.

36. Raheem OA, Mirheydar HS, Patel ND, et al. Surgical management of traumatic penile amputation: a case report and review of the world literature. Sex Med. 2015;3(1):49-53.

37. Young LD, Feinsilver DL. Male genital self-mutilation: combined surgical and psychiatric care. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(7):513-517.

38. Walsh B. Clinical assessment of self-injury: a practical guide. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1057-1066.

39. Nafisi N, Stanley B. Developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance with self-injuring patients. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1069-1079.

40. Fisch RZ. Genital self-mutilation in males: psychodynamic anatomy of a psychosis. Am J Psychother. 1987;41(3):453-458.

41. King PR. Cognitive-behavioral intervention in a case of self-mutilation. Clin Case Stud. 2014;13(2):181-189.

42. Muehlenkamp JJ. Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. J Ment Health Couns. 2006;28(2):166-185.

43. Walsh BW. Treating self-injury: a practical guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006.

44. Large M, Babidge N, Andrews D, et al. Major self-mutilation in the first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):1012-1021.

45. Large MM, Nielssen OB, Babidge N. Untreated psychosis is the main cause of major self-mutilation. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(1):65.

46. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell NR. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychol Med. 2003;33(1):15-21.

47. Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM, Nelson JC, et al. Psychotogenic drug use and neuroleptic response. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16(1):81-85.

CASE Bleeding, bewildered

Mr. K, age 23, a South Asian male, is discovered in the bathroom bleeding profusely. Mr. K’s parents inform emergency medical services (EMS) personnel that Mr. K is “not in his right mind” and speculate that he is depressed. EMS personnel find Mr. K sitting in a pool of blood in the bathtub, holding a cloth over his pubic area and complaining of significant pain. They estimate that Mr. K has lost approximately 1 L of blood. Cursory evaluation reveals that his penis is severed; no other injuries or lacerations are notable. Mr. K states, “I did not want it anymore.” A kitchen knife that he used to self-amputate is found nearby. He is awake, alert, and able to follow simple directives.

In the emergency room, Mr. K is in mild-to-moderate distress. He has no history of medical illness, but his parents report that he previously required psychiatric treatment. Mr. K is not able to elaborate. He reluctantly discloses an intermittent history of Cannabis use. Physical examination reveals tachycardia (heart rate: 115 to 120 beats per minute), and despite blood loss, systolic hypertension (blood pressure: 142/70 to 167/70 mm Hg). His pulse oximetry is 97% to 99%; he is afebrile. Laboratory tests are notable for anemia (hemoglobin, 7.2 g/dL [reference range, 14.0 to 17.5 g/dL]; hematocrit, 21.2% [reference range, 41% to 50%]) and serum toxicology screen is positive for benzodiazepines, which had been administered en route to allay his distress.

Mr. K continues to hold pressure on his pubic area. When pressure is released, active arterial spurting of bright red blood is notable. Genital examination reveals a cleanly amputated phallus. Emergent surgical intervention is required to stop the hemorrhage and reattach the penis. Initially, Mr. K is opposed to reattachment, but after a brief discussion with his parents, he consents to surgery. Urology and plastic surgery consultations are elicited to perform the microvascular portion of the procedure.

[polldaddy:9881368]

The authors’ observations

Self-injurious behaviors occur in approximately 1% to 4% of adults in the United States, with chronic and severe self-injury occurring among approximately 1% of the U.S. population.1,2 Intentional GSM is a relatively rare catastrophic event that is often, but not solely, associated with severe mental illness. Because many cases go unreported, the prevalence of GSM is difficult to estimate.3,4 Although GSM has been described in both men and women, the literature has predominantly focused on GSM among men.5 Genital self-injury has been described in several (ie, ethnic/racial and religious) contexts and has been legally sanctioned.6-8

Psychiatric disorders associated with, and precipitating factors underlying, GSM have long remained elusive.8 GSM has been described in case reports and small case series in both psychiatric and urologic literature. These reports provide incomplete descriptions of the diagnostic conditions and psychosocial factors underlying male GSM.

A recent systematic review of 173 cases of men who engaged in GSM published in the past 115 years (since the first case of GSM was published in the psychiatric literature9) revealed that having some form of psychopathology elevates the probability of GSM10,11; rarely the individual did not have a psychiatric condition.11-17 Nearly one-half of the men had psychosis; most had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis. Other psychiatric conditions associated with GSM include personality disorders, substance use disorder, and gender dysphoria. GSM is rarely associated with anxiety or mood disorders.

GSM is a heterogeneous form of self-injury that ranges from superficial genital lacerations, amputation, or castration to combinations of these injuries. Compared with individuals with other psychiatric disorders, a significantly greater proportion of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders engage in self-amputation (auto-penectomy). By contrast, persons with gender dysphoria tend to engage in self-castration at significantly higher rates than those with other psychiatric conditions.11 Despite these trends, clinicians should not infer a specific psychiatric diagnosis based on the severity or type of self-inflicted injury.

HISTORY Command hallucinations

Postoperatively, Mr. K is managed in the trauma intensive care unit. During psychiatric consultation, Mr. K demonstrates a blunted affect. His speech is low in volume but clear and coherent. His thoughts are generally linear for specific lines of inquiry (eg, about perceived level of pain) but otherwise are impoverished. Mr. K often digresses into repetitively mumbled prayers. He appears distracted, as if responding to internal stimuli. Although he acknowledges the GSM, he does not discuss the factors underlying his decision to proceed with auto-penectomy. Over successive evaluations, he reluctantly discloses that he had been experiencing disparaging auditory hallucinations that told him that his penis “was too small” and commanded him to “cut it off.”

Psychiatric history reveals that Mr. K required psychiatric hospitalization 7 months earlier due to new-onset auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and thought disorganization, in the context of daily Cannabis use. At the time, the differential diagnosis included new-onset schizophrenia and substance-induced psychosis. His symptoms improved quickly with risperidone, 2 mg/d, and he was discharged in a stable condition with referrals for outpatient care. Mr. K admits he had stopped taking risperidone several weeks before the GSM because he was convinced that he had been cured. At that time, Mr. K had told his parents he was no longer required to take medication or engage in outpatient psychiatric treatment, and they did not question this. Mr. K struggled to sustain part-time employment (in a family business), having taken a leave of absence from graduate school after his first hospitalization. He continued to use Cannabis regularly but denies being intoxicated at the time of the GSM. Throughout his surgical hospitalization, Mr. K’s thoughts remain disorganized. He denies that the GSM was a suicide attempt or having current suicidal thoughts, intent, or plans. He also denies having religious preoccupations, over-valued religious beliefs, or delusions.

Mr. K identifies as heterosexual, and denies experiencing distress related to sexual orientation or gender identity or guilt related to sexual impulses or actions. He also denies having a history of trauma or victimization and does not report any symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder or body dysmorphic disorder.

The authors’ observations

Little is known about how many individuals who engage in GSM eventually complete suicide. Although suicidal ideation and intent have been infrequently associated with GSM, suicide has been most notably reported among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and psychotic mood disorders.11,18,23-26 For these individuals, suicidal ideation co-occurred with delusions, hallucinations, and pathological guilt preoccupations. Significant self-inflicted injury can be harbinger of distress that could lead to suicide if not optimally treated. Other psychosocial stressors, such as disruptions in interpersonal functioning arising from changes in or loss of social support or perceived rejection, may contribute to a patient’s level of distress, complicating underlying psychiatric disturbances and increasing vulnerability toward GSM.11,27

Substance use also increases vulnerability toward GSM.11,18,24,28 As is the case with patients who engage in various non-GSM self-injurious behaviors,29,30 substance use or intoxication likely contribute to disinhibition or a dissociative state, which enables individuals to engage in self-injury.30

A lack of access to treatment is a rare precipitant for GSM, except among individuals with gender dysphoria. Studies have found that many patients with gender dysphoria who performed self-castration did so in a premeditated manner with low suicidal intent, and the behavior often was related to a lack of or refusal for gender confirmation surgery.31-34

In the hospital setting, surgical/urological interventions need to be directed at the potentially life-threatening sequelae of self-injury. Although complications vary, depending on the type of injury incurred, urgent measures are needed to manage blood loss because hemorrhage can be fatal.23,35,36 Other consequences that can arise include urinary fistulae, urethral strictures, mummification of the glans penis, and development of sensory abnormalities after repair of the injured tissues or reattachment.8 More superficial injuries may require only hemostasis and simple suturing, whereas extensive injuries, such as complete amputation, can be addressed through microvascular techniques.

The psychiatrist’s role. The psychiatrist should act as an advocate for the GSM patient to create an environment conducive to healing. A patient who is experiencing hallucinations or delusions may feel overwhelmed by medical and familial attention. Pharmacologic treatment for prevailing mental illness, such as psychosis, should be initiated in the inpatient setting. An estimated 20% to 25% of those who self-inflict genital injury may repeatedly mutilate their genitals.19,28 Patients unduly influenced by command hallucinations, delusional thought processes, mood disturbances, or suicidal ideation may attempt to complete the injury, or reinjure themselves after surgical/urological intervention, which may require safety measures, such as 1:1 observation, restraints, or physical barriers, to prevent reinjury.37

Self-injury elicits strong, emotional responses from health care professionals, including fascination, apprehension, and hopelessness. Psychiatrists who care for such patients should monitor members of the patient’s treatment team for psychological reactions. In addition, the patient’s behavior while hospitalized may stir feelings of retaliation, anger, fear, and frustration.11,24,37 Collaborative relationships with medical and surgical specialties can help staff manage emotional reactions and avoid the inadvertent expression of those feelings in their interactions with the patient; these reactions might otherwise undermine treatment.24,34 Family education can help mitigate any guilt family members may harbor for not preventing the injury.37

Although efforts to understand the intended goal(s) and precipitants of the self-injury are likely to be worthwhile, the overwhelming distress associated with GSM and its emergent treatment may preclude intensive exploration.

TREATMENT Restarting medication

While on the surgical unit, Mr. K is restarted on risperidone, 2 mg/d. He appears to tolerate the medication without adverse effects. However, because Mr. K continues to experience auditory hallucinations, and the treatment team remains concerned that he might again experience commands to harm himself, he is transferred to an acute psychiatric inpatient setting.

Urology follow-up reveals necrosis/mummification of the replanted penis and an open scrotal wound. After discussing options with the patient and family, the urologist transfers Mr. K back to the surgical unit for wound closure and removal of the replanted penis. A urethrostomy is performed to allow for bladder emptying.

[polldaddy:9881371]

The authors’ observations

Because most published case reports of GSM among men have focused on acute treatment, there is a dearth of literature available on the long-term course of GSM to inform treatment strategies. Because recovery is a non-static process and a patient’s reactions to his injury will likely evolve over time, a multifaceted approach invoking psychiatric and psychotherapeutic interventions is necessary to help patients after initial injury and surgical management37,40-43 (Table 211,20,27,41).

OUTCOME Return to school, work

Mr. K is discharged with close follow-up at a specialized clinic for new-onset psychosis. Post-discharge treatment consists of education about the course of schizophrenia and the need for medication adherence to prevent relapse. Mr. K also is educated on the relationship between Cannabis use and psychosis, and he abstains from illicit substance use. Family involvement is encouraged to help with medication compliance and monitoring for symptom reemergence.

Therapy focuses on exploring the antecedents of the auto-penectomy, Mr. K’s body image issue concerns, and his feelings related to eventual prosthesis implantation. He insists that he cannot recall any precipitating factors for his self-injury other than the command hallucinations. He does not report sexual guilt, although he had been sexually active with his girlfriend in the months prior to his GSM, which goes against his family’s religious beliefs. He reports significant regret and shame for the self-mutilation, and blames himself for not informing family members about his hallucinations. Therapy involves addressing his attribution of blame using cognitive techniques and focuses on measures that can be taken to prevent further self-harm. Efforts are directed at exploring whether cultural and religious traditions impacted the therapeutic alliance, medication adherence, self-esteem and body image, sexuality, and future goals. Over the course of 1 year, he resumes his graduate studies and part-time work, and explores prosthetic placement for cosmetic purposes.

The authors’ observations

Research suggests that major self-mutilation among patients with psychotic illness is likely to occur during the first episode or early in the course of illness and/or with suboptimal treatment.44,45 Mr. K was enlisted in an intensive outpatient treatment program involving biweekly psychotherapy sessions and psychiatric follow-up. Initial sessions focused on education regarding the importance of medication adherence and exploration of signs and symptoms that might suggest reemergence of a psychotic decompensation. The psychiatrist monitored Mr. K closely to ensure he was able to tolerate his medications to mitigate the possibility that adverse effects would undermine adherence. Mr. K’s reactions to having a psychiatric illness also were explored because of concerns that such self-appraisals might trigger shame, embarrassment, denial, and other responses that might undermine treatment adherence. His family members were apprised of treatment goals and enlisted to foster adherence with medication and follow-up appointments.

Mr. K’s Cannabis use was addressed because ongoing use likely had a negative impact on his schizophrenia (ie, a greater propensity toward relapse and rehospitalization and a poorer therapeutic response to antipsychotic medication).46,47 He was strongly encouraged to avoid Cannabis and other illicit substances.

Psychiatrists can help in examining the meaning behind the injury while helping the patient to adapt to the sequelae and cultivate skills to meet functional demands.41 Once Mr. K’s psychotic symptoms were in remission, treatment began to address the antecedents of the GSM, as well as the resultant physical consequences. It was reasonable to explore how Mr. K now viewed his actions, as well as the consequences that his actions produced in terms of his physical appearance, sexual functioning, capacity for sexual intimacy, and reproductive potential. It was also important to recognize how such highly intimate and deeply personal self-schema are framed and organized against his cultural and religious background.27,33

Body image concerns and expectations for future urologic intervention also should be explored. Although Mr. K was not averse to such exploration, he did not spontaneously address such topics in great depth. The discussion was unforced and effectively left open as an issue that could be explored in future sessions.

CASE Bleeding, bewildered

Mr. K, age 23, a South Asian male, is discovered in the bathroom bleeding profusely. Mr. K’s parents inform emergency medical services (EMS) personnel that Mr. K is “not in his right mind” and speculate that he is depressed. EMS personnel find Mr. K sitting in a pool of blood in the bathtub, holding a cloth over his pubic area and complaining of significant pain. They estimate that Mr. K has lost approximately 1 L of blood. Cursory evaluation reveals that his penis is severed; no other injuries or lacerations are notable. Mr. K states, “I did not want it anymore.” A kitchen knife that he used to self-amputate is found nearby. He is awake, alert, and able to follow simple directives.

In the emergency room, Mr. K is in mild-to-moderate distress. He has no history of medical illness, but his parents report that he previously required psychiatric treatment. Mr. K is not able to elaborate. He reluctantly discloses an intermittent history of Cannabis use. Physical examination reveals tachycardia (heart rate: 115 to 120 beats per minute), and despite blood loss, systolic hypertension (blood pressure: 142/70 to 167/70 mm Hg). His pulse oximetry is 97% to 99%; he is afebrile. Laboratory tests are notable for anemia (hemoglobin, 7.2 g/dL [reference range, 14.0 to 17.5 g/dL]; hematocrit, 21.2% [reference range, 41% to 50%]) and serum toxicology screen is positive for benzodiazepines, which had been administered en route to allay his distress.

Mr. K continues to hold pressure on his pubic area. When pressure is released, active arterial spurting of bright red blood is notable. Genital examination reveals a cleanly amputated phallus. Emergent surgical intervention is required to stop the hemorrhage and reattach the penis. Initially, Mr. K is opposed to reattachment, but after a brief discussion with his parents, he consents to surgery. Urology and plastic surgery consultations are elicited to perform the microvascular portion of the procedure.

[polldaddy:9881368]

The authors’ observations

Self-injurious behaviors occur in approximately 1% to 4% of adults in the United States, with chronic and severe self-injury occurring among approximately 1% of the U.S. population.1,2 Intentional GSM is a relatively rare catastrophic event that is often, but not solely, associated with severe mental illness. Because many cases go unreported, the prevalence of GSM is difficult to estimate.3,4 Although GSM has been described in both men and women, the literature has predominantly focused on GSM among men.5 Genital self-injury has been described in several (ie, ethnic/racial and religious) contexts and has been legally sanctioned.6-8

Psychiatric disorders associated with, and precipitating factors underlying, GSM have long remained elusive.8 GSM has been described in case reports and small case series in both psychiatric and urologic literature. These reports provide incomplete descriptions of the diagnostic conditions and psychosocial factors underlying male GSM.

A recent systematic review of 173 cases of men who engaged in GSM published in the past 115 years (since the first case of GSM was published in the psychiatric literature9) revealed that having some form of psychopathology elevates the probability of GSM10,11; rarely the individual did not have a psychiatric condition.11-17 Nearly one-half of the men had psychosis; most had a schizophrenia spectrum disorder diagnosis. Other psychiatric conditions associated with GSM include personality disorders, substance use disorder, and gender dysphoria. GSM is rarely associated with anxiety or mood disorders.

GSM is a heterogeneous form of self-injury that ranges from superficial genital lacerations, amputation, or castration to combinations of these injuries. Compared with individuals with other psychiatric disorders, a significantly greater proportion of individuals with schizophrenia spectrum disorders engage in self-amputation (auto-penectomy). By contrast, persons with gender dysphoria tend to engage in self-castration at significantly higher rates than those with other psychiatric conditions.11 Despite these trends, clinicians should not infer a specific psychiatric diagnosis based on the severity or type of self-inflicted injury.

HISTORY Command hallucinations

Postoperatively, Mr. K is managed in the trauma intensive care unit. During psychiatric consultation, Mr. K demonstrates a blunted affect. His speech is low in volume but clear and coherent. His thoughts are generally linear for specific lines of inquiry (eg, about perceived level of pain) but otherwise are impoverished. Mr. K often digresses into repetitively mumbled prayers. He appears distracted, as if responding to internal stimuli. Although he acknowledges the GSM, he does not discuss the factors underlying his decision to proceed with auto-penectomy. Over successive evaluations, he reluctantly discloses that he had been experiencing disparaging auditory hallucinations that told him that his penis “was too small” and commanded him to “cut it off.”

Psychiatric history reveals that Mr. K required psychiatric hospitalization 7 months earlier due to new-onset auditory hallucinations, paranoia, and thought disorganization, in the context of daily Cannabis use. At the time, the differential diagnosis included new-onset schizophrenia and substance-induced psychosis. His symptoms improved quickly with risperidone, 2 mg/d, and he was discharged in a stable condition with referrals for outpatient care. Mr. K admits he had stopped taking risperidone several weeks before the GSM because he was convinced that he had been cured. At that time, Mr. K had told his parents he was no longer required to take medication or engage in outpatient psychiatric treatment, and they did not question this. Mr. K struggled to sustain part-time employment (in a family business), having taken a leave of absence from graduate school after his first hospitalization. He continued to use Cannabis regularly but denies being intoxicated at the time of the GSM. Throughout his surgical hospitalization, Mr. K’s thoughts remain disorganized. He denies that the GSM was a suicide attempt or having current suicidal thoughts, intent, or plans. He also denies having religious preoccupations, over-valued religious beliefs, or delusions.

Mr. K identifies as heterosexual, and denies experiencing distress related to sexual orientation or gender identity or guilt related to sexual impulses or actions. He also denies having a history of trauma or victimization and does not report any symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder or body dysmorphic disorder.

The authors’ observations

Little is known about how many individuals who engage in GSM eventually complete suicide. Although suicidal ideation and intent have been infrequently associated with GSM, suicide has been most notably reported among patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and psychotic mood disorders.11,18,23-26 For these individuals, suicidal ideation co-occurred with delusions, hallucinations, and pathological guilt preoccupations. Significant self-inflicted injury can be harbinger of distress that could lead to suicide if not optimally treated. Other psychosocial stressors, such as disruptions in interpersonal functioning arising from changes in or loss of social support or perceived rejection, may contribute to a patient’s level of distress, complicating underlying psychiatric disturbances and increasing vulnerability toward GSM.11,27

Substance use also increases vulnerability toward GSM.11,18,24,28 As is the case with patients who engage in various non-GSM self-injurious behaviors,29,30 substance use or intoxication likely contribute to disinhibition or a dissociative state, which enables individuals to engage in self-injury.30

A lack of access to treatment is a rare precipitant for GSM, except among individuals with gender dysphoria. Studies have found that many patients with gender dysphoria who performed self-castration did so in a premeditated manner with low suicidal intent, and the behavior often was related to a lack of or refusal for gender confirmation surgery.31-34

In the hospital setting, surgical/urological interventions need to be directed at the potentially life-threatening sequelae of self-injury. Although complications vary, depending on the type of injury incurred, urgent measures are needed to manage blood loss because hemorrhage can be fatal.23,35,36 Other consequences that can arise include urinary fistulae, urethral strictures, mummification of the glans penis, and development of sensory abnormalities after repair of the injured tissues or reattachment.8 More superficial injuries may require only hemostasis and simple suturing, whereas extensive injuries, such as complete amputation, can be addressed through microvascular techniques.

The psychiatrist’s role. The psychiatrist should act as an advocate for the GSM patient to create an environment conducive to healing. A patient who is experiencing hallucinations or delusions may feel overwhelmed by medical and familial attention. Pharmacologic treatment for prevailing mental illness, such as psychosis, should be initiated in the inpatient setting. An estimated 20% to 25% of those who self-inflict genital injury may repeatedly mutilate their genitals.19,28 Patients unduly influenced by command hallucinations, delusional thought processes, mood disturbances, or suicidal ideation may attempt to complete the injury, or reinjure themselves after surgical/urological intervention, which may require safety measures, such as 1:1 observation, restraints, or physical barriers, to prevent reinjury.37

Self-injury elicits strong, emotional responses from health care professionals, including fascination, apprehension, and hopelessness. Psychiatrists who care for such patients should monitor members of the patient’s treatment team for psychological reactions. In addition, the patient’s behavior while hospitalized may stir feelings of retaliation, anger, fear, and frustration.11,24,37 Collaborative relationships with medical and surgical specialties can help staff manage emotional reactions and avoid the inadvertent expression of those feelings in their interactions with the patient; these reactions might otherwise undermine treatment.24,34 Family education can help mitigate any guilt family members may harbor for not preventing the injury.37

Although efforts to understand the intended goal(s) and precipitants of the self-injury are likely to be worthwhile, the overwhelming distress associated with GSM and its emergent treatment may preclude intensive exploration.

TREATMENT Restarting medication

While on the surgical unit, Mr. K is restarted on risperidone, 2 mg/d. He appears to tolerate the medication without adverse effects. However, because Mr. K continues to experience auditory hallucinations, and the treatment team remains concerned that he might again experience commands to harm himself, he is transferred to an acute psychiatric inpatient setting.

Urology follow-up reveals necrosis/mummification of the replanted penis and an open scrotal wound. After discussing options with the patient and family, the urologist transfers Mr. K back to the surgical unit for wound closure and removal of the replanted penis. A urethrostomy is performed to allow for bladder emptying.

[polldaddy:9881371]

The authors’ observations

Because most published case reports of GSM among men have focused on acute treatment, there is a dearth of literature available on the long-term course of GSM to inform treatment strategies. Because recovery is a non-static process and a patient’s reactions to his injury will likely evolve over time, a multifaceted approach invoking psychiatric and psychotherapeutic interventions is necessary to help patients after initial injury and surgical management37,40-43 (Table 211,20,27,41).

OUTCOME Return to school, work

Mr. K is discharged with close follow-up at a specialized clinic for new-onset psychosis. Post-discharge treatment consists of education about the course of schizophrenia and the need for medication adherence to prevent relapse. Mr. K also is educated on the relationship between Cannabis use and psychosis, and he abstains from illicit substance use. Family involvement is encouraged to help with medication compliance and monitoring for symptom reemergence.

Therapy focuses on exploring the antecedents of the auto-penectomy, Mr. K’s body image issue concerns, and his feelings related to eventual prosthesis implantation. He insists that he cannot recall any precipitating factors for his self-injury other than the command hallucinations. He does not report sexual guilt, although he had been sexually active with his girlfriend in the months prior to his GSM, which goes against his family’s religious beliefs. He reports significant regret and shame for the self-mutilation, and blames himself for not informing family members about his hallucinations. Therapy involves addressing his attribution of blame using cognitive techniques and focuses on measures that can be taken to prevent further self-harm. Efforts are directed at exploring whether cultural and religious traditions impacted the therapeutic alliance, medication adherence, self-esteem and body image, sexuality, and future goals. Over the course of 1 year, he resumes his graduate studies and part-time work, and explores prosthetic placement for cosmetic purposes.

The authors’ observations

Research suggests that major self-mutilation among patients with psychotic illness is likely to occur during the first episode or early in the course of illness and/or with suboptimal treatment.44,45 Mr. K was enlisted in an intensive outpatient treatment program involving biweekly psychotherapy sessions and psychiatric follow-up. Initial sessions focused on education regarding the importance of medication adherence and exploration of signs and symptoms that might suggest reemergence of a psychotic decompensation. The psychiatrist monitored Mr. K closely to ensure he was able to tolerate his medications to mitigate the possibility that adverse effects would undermine adherence. Mr. K’s reactions to having a psychiatric illness also were explored because of concerns that such self-appraisals might trigger shame, embarrassment, denial, and other responses that might undermine treatment adherence. His family members were apprised of treatment goals and enlisted to foster adherence with medication and follow-up appointments.

Mr. K’s Cannabis use was addressed because ongoing use likely had a negative impact on his schizophrenia (ie, a greater propensity toward relapse and rehospitalization and a poorer therapeutic response to antipsychotic medication).46,47 He was strongly encouraged to avoid Cannabis and other illicit substances.

Psychiatrists can help in examining the meaning behind the injury while helping the patient to adapt to the sequelae and cultivate skills to meet functional demands.41 Once Mr. K’s psychotic symptoms were in remission, treatment began to address the antecedents of the GSM, as well as the resultant physical consequences. It was reasonable to explore how Mr. K now viewed his actions, as well as the consequences that his actions produced in terms of his physical appearance, sexual functioning, capacity for sexual intimacy, and reproductive potential. It was also important to recognize how such highly intimate and deeply personal self-schema are framed and organized against his cultural and religious background.27,33

Body image concerns and expectations for future urologic intervention also should be explored. Although Mr. K was not averse to such exploration, he did not spontaneously address such topics in great depth. The discussion was unforced and effectively left open as an issue that could be explored in future sessions.

1. Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):609-620.

2. Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: prevalence and psychological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1501-1508.

3. Krasucki C, Kemp R, David A. A case study of female genital self-mutilation in schizophrenia. Br J Med Psychol. 1995;68(pt 2):179-186.

4. Lennon S. Genital self-mutilation in acute mania. Med J Aust. 1963;50(1):79-81.

5. Schweitzer I. Genital self-amputation and the Klingsor syndrome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990;24(4):566-569.

6. Anumonye A. Self-inflicted amputation of the penis in two Nigerian males. Niger Med J. 1973;3(1):51-52.

7. Bowman KM, Crook GH. Emotional changes following castration. Psychiatr Res Rep Am Psychiatr Assoc. 1960;12:81-96.

8. Eke N. Genital self-mutilation: there is no method in this madness. BJU Int. 2000;85(3):295-298.

9. Stroch D. Self-castration. JAMA. 1901;36(4):270.

10. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a comprehensive review of psychiatric disorders. Poster presented at: Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 10, 2016.

11. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a systematic review of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:43-50.

12. Battle AO. The psychological appraisal of a patient who had performed self-castration. British Journal of Projective Psychology & Personality Study. 1973;18(2):5-17.

13. Bhatia MS, Arora S. Penile self-mutilation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(1):86-87.

14. Gleeson MJ, Connolly J, Grainger R. Self-castration as treatment for alopecia. Br J Urol. 1993;71(5):614-615.

15. Hendershot E, Stutson AC, Adair TW. A case of extreme sexual self-mutilation. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55(1):245-247.

16. Hermann M, Thorstenson A. A rare case of male‐to‐eunuch gender dysphoria. Sex Med. 2015;3(4):331-333.

17. Nerli RB, Ravish IR, Amarkhed SS, et al. Genital self-mutilation in nonpsychotic heterosexual males: case report of two cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50(4):285-287.

18. Blacker KH, Wong N. Four cases of autocastration. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;8:169-176.

19. Catalano G, Catalano MC, Carroll KM. Repetitive male genital self-mutilation: a case report and discussion of possible risk factors. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(1):27-37.

20. Martin T, Gattaz WF. Psychiatric aspects of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1991;24(3):170-178.

21. Money J. The Skoptic syndrome: castration and genital self-mutilation as an example of sexual body-image pathology. J Psychol Human Sex. 1988;1(1):113-128.

22. Nakaya M. On background factors of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1996;29(4):242-248.

23. Borenstein A, Yaffe B, Seidman DS, et al. Successful microvascular replantation of an amputated penis. Isr J Med Sci. 1991;27(7):395-398.

24. Greilsheimer H, Groves JE. Male genital self-mutilation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(4):441-446.

25. Mendez R, Kiely WF, Morrow JW. Self-emasculation. J Urol. 1972;107(6):981-985.

26. Siddique RA, Deshpande S. A case of genital self-mutilation in a patient with psychosis. German J Psychiatry. 2007;10(1):25-28.

27. Qureshi NA. Male genital self-mutilation with special emphasis on the sociocultural meanings. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2009;14(2):178-181.

28. Romilly CS, Isaac MT. Male genital self-mutilation. Br J Hosp Med. 1996;55(7):427-431.

29. Gahr M, Plener PL, Kölle MA, et al. Self-mutilation induced by psychotropic substances: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):977-983.

30. Evren C, Sar V, Evren B, et al. Self-mutilation among male patients with alcohol dependency: the role of dissociation. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):489-495.

31. Brown GR. Autocastration and autopenectomy as surgical self-treatment in incarcerated persons with gender identity disorder. Int J Transgend. 2010;12(1):31-39.

32. Master VA, McAninch JW, Santucci RA. Genital self-mutilation and the Internet. J Urol. 2000;164(5):1656.

33. Premand NE, Eytan A. A case of non-psychotic autocastration: the importance of cultural factors. Psychiatry. 2005;68(2):174-178.

34. Simopoulos EF, Trinidad AC. Two cases of male genital self-mutilation: an examination of liaison dynamics. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):178-180.

35. Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, et al. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33(2):385-386.

36. Raheem OA, Mirheydar HS, Patel ND, et al. Surgical management of traumatic penile amputation: a case report and review of the world literature. Sex Med. 2015;3(1):49-53.

37. Young LD, Feinsilver DL. Male genital self-mutilation: combined surgical and psychiatric care. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(7):513-517.

38. Walsh B. Clinical assessment of self-injury: a practical guide. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1057-1066.

39. Nafisi N, Stanley B. Developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance with self-injuring patients. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1069-1079.

40. Fisch RZ. Genital self-mutilation in males: psychodynamic anatomy of a psychosis. Am J Psychother. 1987;41(3):453-458.

41. King PR. Cognitive-behavioral intervention in a case of self-mutilation. Clin Case Stud. 2014;13(2):181-189.

42. Muehlenkamp JJ. Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. J Ment Health Couns. 2006;28(2):166-185.

43. Walsh BW. Treating self-injury: a practical guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006.

44. Large M, Babidge N, Andrews D, et al. Major self-mutilation in the first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):1012-1021.

45. Large MM, Nielssen OB, Babidge N. Untreated psychosis is the main cause of major self-mutilation. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(1):65.

46. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell NR. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychol Med. 2003;33(1):15-21.

47. Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM, Nelson JC, et al. Psychotogenic drug use and neuroleptic response. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16(1):81-85.

1. Briere J, Gil E. Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: prevalence, correlates, and functions. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68(4):609-620.

2. Klonsky ED, Oltmanns TF, Turkheimer E. Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: prevalence and psychological correlates. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(8):1501-1508.

3. Krasucki C, Kemp R, David A. A case study of female genital self-mutilation in schizophrenia. Br J Med Psychol. 1995;68(pt 2):179-186.

4. Lennon S. Genital self-mutilation in acute mania. Med J Aust. 1963;50(1):79-81.

5. Schweitzer I. Genital self-amputation and the Klingsor syndrome. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1990;24(4):566-569.

6. Anumonye A. Self-inflicted amputation of the penis in two Nigerian males. Niger Med J. 1973;3(1):51-52.

7. Bowman KM, Crook GH. Emotional changes following castration. Psychiatr Res Rep Am Psychiatr Assoc. 1960;12:81-96.

8. Eke N. Genital self-mutilation: there is no method in this madness. BJU Int. 2000;85(3):295-298.

9. Stroch D. Self-castration. JAMA. 1901;36(4):270.

10. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a comprehensive review of psychiatric disorders. Poster presented at: Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine Meeting, Austin, Texas, November 10, 2016.

11. Veeder TA, Leo RJ. Male genital self-mutilation: a systematic review of psychiatric disorders and psychosocial factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;44:43-50.

12. Battle AO. The psychological appraisal of a patient who had performed self-castration. British Journal of Projective Psychology & Personality Study. 1973;18(2):5-17.

13. Bhatia MS, Arora S. Penile self-mutilation. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178(1):86-87.

14. Gleeson MJ, Connolly J, Grainger R. Self-castration as treatment for alopecia. Br J Urol. 1993;71(5):614-615.

15. Hendershot E, Stutson AC, Adair TW. A case of extreme sexual self-mutilation. J Forensic Sci. 2010;55(1):245-247.

16. Hermann M, Thorstenson A. A rare case of male‐to‐eunuch gender dysphoria. Sex Med. 2015;3(4):331-333.

17. Nerli RB, Ravish IR, Amarkhed SS, et al. Genital self-mutilation in nonpsychotic heterosexual males: case report of two cases. Indian J Psychiatry. 2008;50(4):285-287.

18. Blacker KH, Wong N. Four cases of autocastration. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1963;8:169-176.

19. Catalano G, Catalano MC, Carroll KM. Repetitive male genital self-mutilation: a case report and discussion of possible risk factors. J Sex Marital Ther. 2002;28(1):27-37.

20. Martin T, Gattaz WF. Psychiatric aspects of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1991;24(3):170-178.

21. Money J. The Skoptic syndrome: castration and genital self-mutilation as an example of sexual body-image pathology. J Psychol Human Sex. 1988;1(1):113-128.

22. Nakaya M. On background factors of male genital self-mutilation. Psychopathology. 1996;29(4):242-248.

23. Borenstein A, Yaffe B, Seidman DS, et al. Successful microvascular replantation of an amputated penis. Isr J Med Sci. 1991;27(7):395-398.

24. Greilsheimer H, Groves JE. Male genital self-mutilation. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36(4):441-446.

25. Mendez R, Kiely WF, Morrow JW. Self-emasculation. J Urol. 1972;107(6):981-985.

26. Siddique RA, Deshpande S. A case of genital self-mutilation in a patient with psychosis. German J Psychiatry. 2007;10(1):25-28.

27. Qureshi NA. Male genital self-mutilation with special emphasis on the sociocultural meanings. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2009;14(2):178-181.

28. Romilly CS, Isaac MT. Male genital self-mutilation. Br J Hosp Med. 1996;55(7):427-431.

29. Gahr M, Plener PL, Kölle MA, et al. Self-mutilation induced by psychotropic substances: a systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2012;200(2-3):977-983.

30. Evren C, Sar V, Evren B, et al. Self-mutilation among male patients with alcohol dependency: the role of dissociation. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(5):489-495.

31. Brown GR. Autocastration and autopenectomy as surgical self-treatment in incarcerated persons with gender identity disorder. Int J Transgend. 2010;12(1):31-39.

32. Master VA, McAninch JW, Santucci RA. Genital self-mutilation and the Internet. J Urol. 2000;164(5):1656.

33. Premand NE, Eytan A. A case of non-psychotic autocastration: the importance of cultural factors. Psychiatry. 2005;68(2):174-178.

34. Simopoulos EF, Trinidad AC. Two cases of male genital self-mutilation: an examination of liaison dynamics. Psychosomatics. 2012;53(2):178-180.

35. Darewicz B, Galek L, Darewicz J, et al. Successful microsurgical replantation of an amputated penis. Int Urol Nephrol. 2001;33(2):385-386.

36. Raheem OA, Mirheydar HS, Patel ND, et al. Surgical management of traumatic penile amputation: a case report and review of the world literature. Sex Med. 2015;3(1):49-53.

37. Young LD, Feinsilver DL. Male genital self-mutilation: combined surgical and psychiatric care. Psychosomatics. 1986;27(7):513-517.

38. Walsh B. Clinical assessment of self-injury: a practical guide. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1057-1066.

39. Nafisi N, Stanley B. Developing and maintaining the therapeutic alliance with self-injuring patients. J Clin Psychol. 2007;63(11):1069-1079.

40. Fisch RZ. Genital self-mutilation in males: psychodynamic anatomy of a psychosis. Am J Psychother. 1987;41(3):453-458.

41. King PR. Cognitive-behavioral intervention in a case of self-mutilation. Clin Case Stud. 2014;13(2):181-189.

42. Muehlenkamp JJ. Empirically supported treatments and general therapy guidelines for non-suicidal self-injury. J Ment Health Couns. 2006;28(2):166-185.

43. Walsh BW. Treating self-injury: a practical guide. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2006.

44. Large M, Babidge N, Andrews D, et al. Major self-mutilation in the first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35(5):1012-1021.

45. Large MM, Nielssen OB, Babidge N. Untreated psychosis is the main cause of major self-mutilation. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2011;48(1):65.

46. Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Swain-Campbell NR. Cannabis dependence and psychotic symptoms in young people. Psychol Med. 2003;33(1):15-21.

47. Bowers MB Jr, Mazure CM, Nelson JC, et al. Psychotogenic drug use and neuroleptic response. Schizophr Bull. 1990;16(1):81-85.