User login

Nontraditional therapies for treatment-resistant depression: Part 2

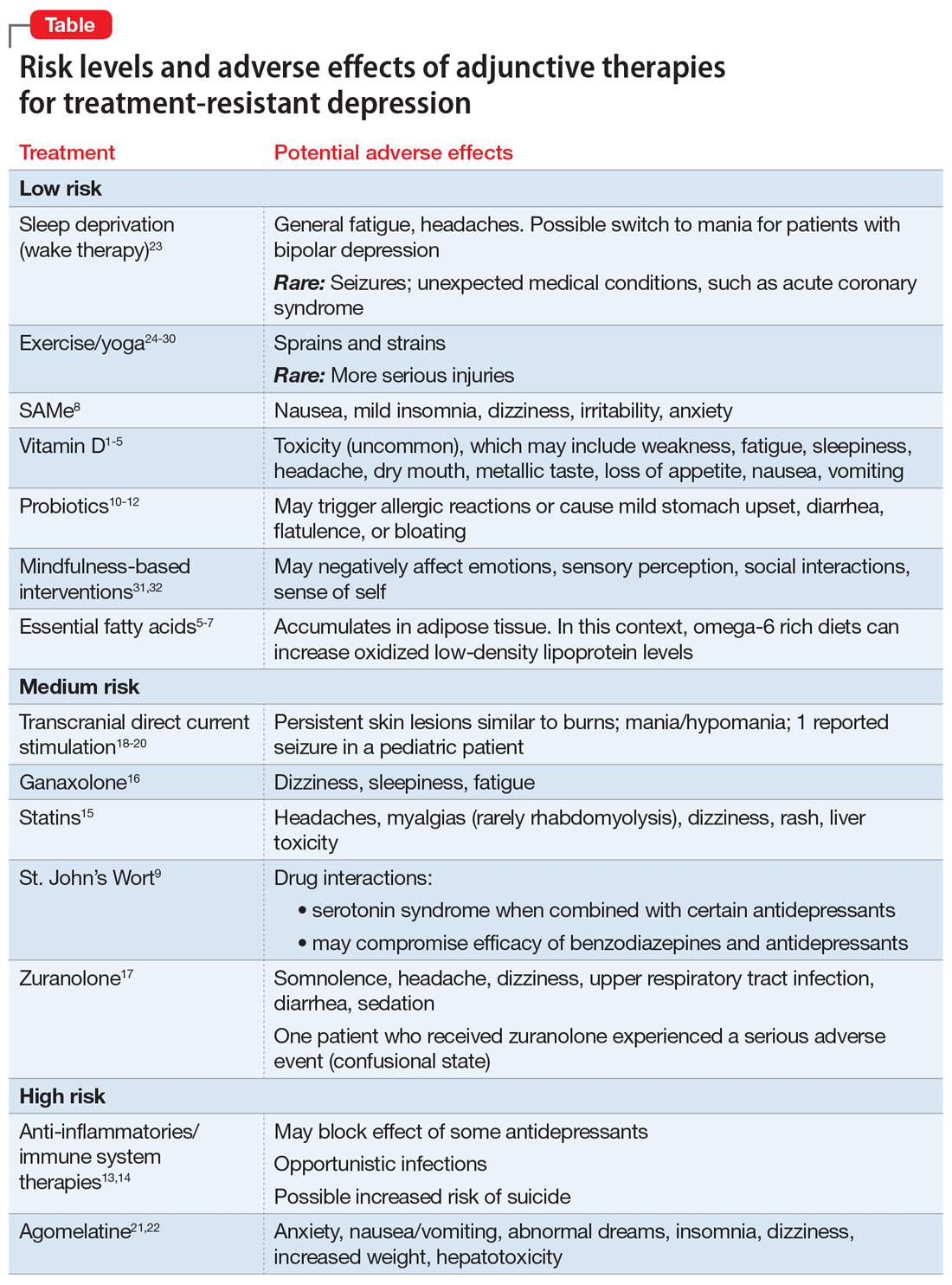

When patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not achieve optimal outcomes after FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies, clinicians look for additional approaches to alleviate their patients’ symptoms. Recent research suggests that several “nontraditional” treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have promise for treatment-resistant depression.

In Part 1 of this article (

Herbal/nutraceutical agents

This category encompasses a variety of commonly available “natural” options patients often ask about and at times self-prescribe. Examples evaluated in clinical trials include:

- vitamin D

- essential fatty acids (omega-3, omega-6)

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe)

- hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort)

- probiotics.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to depression, possibly by lowering serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine concentrations.1-3

A meta-analysis of 3 prospective, observational studies (N = 8,815) found an elevated risk of affective disorders in patients with low vitamin D levels.4 In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis supported a potential role for vitamin D supplementation for patients with treatment-resistant depresssion.5

Toxicity can occur at levels >100 ng/mL, and resulting adverse effects may include weakness, fatigue, sleepiness, headache, loss of appetite, dry mouth, metallic taste, nausea, and vomiting. This vitamin can be considered as an adjunct to standard antidepressants, particularly in patients with treatment-resistant depression who have low vitamin D levels, but regular monitoring is necessary to avoid toxicity.

Essential fatty acids. Protein receptors embedded in lipid membranes and their binding affinities are influenced by omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Thus, essential fatty acids may benefit depression by maintaining membrane integrity and fluidity, as well as via their anti-inflammatory activity.

Continue to: Although results from...

Although results from controlled trials are mixed, a systematic review and meta-analysis of adjunctive nutraceuticals supported a potential role for essential fatty acids, primarily eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), by itself or in combination with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), with total EPA >60%.5 A second meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 2,160) that considered only essential fatty acids concluded that EPA ≥60% at ≤1 g/d could benefit depression.6 Furthermore, omega-3 fatty acids may be helpful as an add-on agent for postpartum depression.7

Be aware that a diet rich in omega-6 greatly increases oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels in adipose tissue, potentially posing a cardiac risk factor. Clinicians need to be aware that self-prescribed use of essential fatty acids is common, and to ask about and monitor their patients’ use of these agents.

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) is an intracellular amino acid and methyl donor. Among other actions, it is involved in the biosynthesis of hormones and neurotransmitters. There is promising but limited preliminary evidence of its efficacy and safety as a monotherapy or for antidepressant augmentation.

- Five out of 6 earlier controlled studies reported SAMe IV (200 to 400 mg/d) or IM (45 to 50 mg/d) was more effective than placebo

- When the above studies were added to 14 subsequent studies for a meta-analysis, 12 of 19 RCTs reported that parenteral or oral SAMe was significantly more effective than placebo for depression (P < .05).

Overall, the safety and tolerability of SAMe are good. Common adverse effects include nausea, mild insomnia, dizziness, irritability, and anxiety. This is another compound widely available without a prescription and at times self-prescribed. It carries an acceptable risk/benefit balance, with decades of experience.

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort) is widely prescribed for depression in China and Europe, typically in doses ranging from 500 to 900 mg/d. Its mechanism of action in depression may relate to inhibition of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine uptake from the synaptic cleft of these interconnecting neurotransmitter systems.

Continue to: A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials...

A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials (N = 3,808) comparing St. John’s Wort with various selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) reported comparable rates of response (pooled relative risk .983, 95% CI .924 to 1.042; P < .001) and remission (pooled relative risk 1.013, 95% CI .892 to 1.134; P < .001).9 Further, there were significantly lower discontinuation/dropout rates (pooled odds ratio .587, 95% CI .478 to 0.697; P < .001) for St. John’s Wort compared with the SSRIs.

Existing evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety is limited (studies ranged from 4 to 12 weeks), as is evidence for patients with more severe depression or high suicidality.

Serious drug interactions include the potential for serotonin syndrome when St. John’s Wort is combined with certain antidepressants, compromised efficacy of benzodiazepines and standard antidepressants, and severe skin reactions to sun exposure. In addition, St. John’s Wort may not be safe to use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Because potential drug interactions can be serious and individuals often self-prescribe this agent, it is important to ask patients about their use of St. John’s Wort, and to be vigilant for such potential adverse interactions.

Probiotics. These agents produce neuroactive substances that act on the brain/gut axis. Preliminary evidence suggests that these “psychobiotics” confer mental health benefits.10-12 Relative to other approaches, their low-risk profile make them an attractive option for some patients.

Anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies

Inflammation is linked to various medical and brain disorders. For example, patients with depression often demonstrate increased levels of peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 and -17) that are known to alter norepinephrine, neuroendocrine (eg, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), and microglia function in addition to neuroplasticity. Thus, targeting inflammation may facilitate the development of novel antidepressants. In addition, these agents may benefit depression associated with comorbid autoimmune disorders, such as psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 RCTs (N = 10,000) found 5 out of 6 anti-inflammatory agents improved depression.13,14 In general, reported disadvantages of anti-inflammatories/immunosuppressants include the potential to block the antidepressant effect of some agents, the risk of opportunistic infections, and an increased risk of suicide.

Continue to: Statins

Statins

In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind trials, 3 statins (lovastatin, atorvastatin, and simvastatin) significantly improved depression scores when used as an adjunctive therapy to fluoxetine and citalopram, compared with adjunctive placebo (N = 165, P < .001).15

Specific adverse effects of statins include headaches, muscle pain (rarely rhabdomyolysis), dizziness, rash, and liver damage. Statins also have the potential for adverse interactions with other medications. Given the limited efficacy literature on statins for depression and the potential for serious adverse effects, these agents probably should be limited to patients with treatment-resistant depression for whom a statin is indicated for a comorbid medical disorder, such as hypercholesteremia.

Neurosteroids

Brexanolone is FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression. It is an IV formulation of the neuroactive steroid hormone allopregnanolone (a metabolite of progesterone), which acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. Unfortunately, the infusion needs to occur over a 60-hour period.

Ganaxolone is an oral analog formulation of allopregnanolone. In an uncontrolled, open-label pilot study, this medication was administered for 8 weeks as an adjunct to an adequately dosed antidepressant to 10 postmenopausal women with persistent MDD.16 Of the 9 women who completed the study, 4 (44%) improved significantly (P < .019) and the benefit was sustained for 2 additional weeks.16 Adverse effects of ganaxolone included dizziness in 60% of participants, and sleepiness and fatigue in all of them with twice-daily dosing. If the FDA approves ganaxolone, it would become an easier-to-administer option to brexanolone.

Zuranolone is an investigational agent being studied as a treatment for postpartum depression. In a double-blind RCT that evaluated 151 women with postpartum depression, those who took oral zuranolone, 30 mg daily at bedtime for 2 weeks, experienced significant reductions in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HDRS-17) scores compared with placebo (P < .003).17 Improvement in core depression symptom ratings was seen as early as Day 3 and persisted through Day 45.

Continue to: The most common...

The most common (≥5%) treatment-emergent adverse effects were somnolence (15%), headache (9%), dizziness (8%), upper respiratory tract infection (8%), diarrhea (6%), and sedation (5%). Two patients experienced a serious adverse event: one who received zuranolone (confusional state) and one who received placebo (pancreatitis). One patient discontinued zuranolone due to adverse effects vs no discontinuations among those who received placebo. The risk of taking zuranolone while breastfeeding is not known.

Device-based strategies

In addition to FDA-cleared approaches (eg, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT], vagus nerve stimulation [VNS], transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS]), other devices have also demonstrated promising results.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) involves delivering weak electrical current to the cerebral cortex through small scalp electrodes to produce the following effects:

- anodal tDCS enhances cortical excitability

- cathodal tDCS reduces cortical excitability.

A typical protocol consists of delivering 1 to 2 mA over 20 minutes with scalp electrodes placed in different configurations based on the targeted symptom(s).

While tDCS has been evaluated as a treatment for various neuropsychiatric disorders, including bipolar depression, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia, most trials have looked at its use for treating depression. Results have been promising but mixed. For example, 1 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (comprising 96 active and 80 sham tDCS courses) reported that active tDCS was superior to a sham procedure (Hedges’ g = 0.743) for symptoms of depression.18 By contrast, another meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (N = 200) did not find a significant difference between active and sham tDCS for response and remission rates.19 More recently, a group of experts created an evidence-based guideline using a systematic review of the controlled trial literature. These authors concluded there is “probable efficacy for anodal tDCS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (with right orbitofrontal cathode) in major depressive episodes without drug resistance but probable inefficacy for drug-resistant major depressive episodes.”20

Continue to: Adverse effects of tDCS...

Adverse effects of tDCS are typically mild but may include persistent skin lesions similar to burns; mania or hypomania; and one reported seizure in a pediatric patient.

Because various over-the-counter direct current stimulation devices are available for purchase at modest cost, clinicians should ask patients if they have been self-administering this treatment.

Chronotherapy strategies

Agomelatine combines serotonergic (5-HT2B and 5-HT2C antagonist) and melatonergic (MT1-MT2 agonist in the suprachiasmatic nucleus) actions that contribute to stabilization of circadian rhythms and subsequent improvement in sleep patterns. Agomelatine (n = 1,274) significantly lowered depression symptoms compared with placebo (n = 689) (standardized mean difference −0.26; P < 3.48×10-11), but the clinical relevance was questionable.21 A recent review of the literature and expert opinion suggest this agent may also have efficacy for anhedonia; however, in placebo-controlled, relapse prevention studies, its long-term efficacy was not consistent.22

Common adverse effects include anxiety; nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain; abnormal dreams and insomnia; dizziness; drowsiness and fatigue; and weight gain. Some reviewers have expressed concerns about agomelatine’s potential for hepatotoxicity and the need for repeated clinical laboratory tests. Although agomelatine is approved outside of the United States, limited efficacy data and the potential for serious adverse effects have precluded FDA approval of this agent.

Sleep deprivation as a treatment technique for depression has been developed over the past 50 years. With total sleep deprivation (TSD) over 1 cycle, patients stay awake for approximately 36 hours, from daytime until the next day’s evening. While 1 to 6 cycles can produce acute antidepressant effects, prompt relapse after sleep recovery is common.

Continue to: In a systematic review...

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies that included a total of 311 patients with bipolar depression23:

- TSD plus medications resulted in a significant decrease in depressive symptoms at 1 week compared with medications alone

- higher response rates were maintained after 3 months with lithium.

Adverse effects commonly include general fatigue and headaches; possible switch into mania with bipolar depression; and rarely, seizures or other unexpected medical conditions (eg, acute coronary syndrome). Presently, this approach is limited to research laboratories with the appropriate sophistication to safely conduct such trials.

Other nontraditional strategies

Cardiovascular exercise, resistance training, mindfulness, and yoga have been shown to decrease severe depressive symptoms when used as adjuncts for patients with treatment-resistant depression, or as monotherapy to treat patients with milder depression.

Exercise. The significant benefits of exercise in various forms as treatment for mild to moderate depression are well described in the literature, but it is less clear if it is effective for treatment-resistant depression. A 2013 Cochrane report24 (39 studies with 2,326 participants total) and 2 meta-analyses undertaken in 2015 (Kvam et al25 included 23 studies with 977 participants, and Schuh et al26 included 25 trials with 1,487 participants) reported that various types of exercise ameliorate depression of differing subtypes and severity, with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Schuh et al26 found that publication bias underestimated effect size. Also, not surprisingly, separate analysis of only higher-quality trials decreased effect size.24-26 A meta-analysis that included tai chi and yoga in addition to aerobic exercise and strength training (25 trials with 2,083 participants) found low to moderate benefit for exercise and yoga.27 Finally, a meta-analysis by Cramer et al28 that included 12 RCTs (N = 619) supported the use of yoga plus controlled breathing techniques as an ancillary treatment for depression.

Two small exercise trials specifically evaluated patients with treatment-resistant depression.29,30 Mota-Pereira et al29 compared 22 participants who walked for 30 to 45 minutes, 5 days a week for 12 weeks in addition to pharmacotherapy with 11 patients who received pharmacotherapy only. Exercise improved all outcomes, including HDRS score (both compared to baseline and to the control group). Moreover, 26% of the exercise group went into remission. Pilu et al30 evaluated strength training as an adjunctive treatment. Participants received 1 hour of strength training twice weekly for 8 months (n = 10), or pharmacotherapy only (n = 20). The adjunct strength training group had a statistically significant (P < .0001) improvement in HDRS scores at the end of the 8 months, whereas the control group did not (P < .28).

Continue to: Adverse effects...

Adverse effects of exercise are typically limited to sprains or strains; rarely, participants experience serious injuries.

Mindfulness-based interventions involve purposely paying attention in the present moment to enhance self-understanding and decrease anxiety about the future and regrets about the past, both of which complicate depression. A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs (N = 578) found this approach significantly reduced depression severity when used as an adjunctive therapy.31 There may be risks if mindfulness-based interventions are practiced incorrectly. For example, some reports have linked mindfulness-based interventions to psychotic episodes, meditation addiction, and antisocial or asocial behavior.32

Bottom Line

Nonpharmacologic options for patients with treatment-resistant depression include herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, and devices. While research suggests some of these approaches are promising, clinicians need to carefully consider potential adverse effects, some of which may be serious.

Related Resources

- Kaur M, Sanches M. Experimental therapeutics in treatmentresistant major depressive disorder. J Exp Pharmacol. 2021;13:181-196.

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Citalopram • Celexa

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lovastatin • Altoprev, Mevacor

Minocycline • Dynacin, Minocin

Simvastatin • Flolipid, Zocor

1. Pittampalli S, Mekala HM, Upadhyayula, S, et al. Does vitamin D deficiency cause depression? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):17l02263.

2. Parker GB, Brotchie H, Graham RK. Vitamin D and depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:56-61.

3. Berridge MJ. Vitamin D and depression: cellular and regulatory mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69(2):80-92.

4. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

5. Sarris J, Murphy J, Mischoulon D, et al. Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(6);575-587.

6. Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):190.

7. Mocking RJT, Steijn K, Roos C, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for perinatal depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):19r13106.

8. Sharma A, Gerbarg P, Bottiglieri T, et al; Work Group of the American Psychiatric Association Council on Research. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for neuropsychiatric disorders: a clinician-oriented review of research. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e656-e667.

9. Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CY. Clinical use of hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017;210:211-221.

10. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):483.

11. Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;102:13-23.

12. Wallace CJK, Milev RV. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of probiotics on depression: clinical results from an open-label pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12(132):618279.

13. Köhler-Forsberg O, N Lyndholm C, Hjorthøj C, et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(5):404-419.

14. Jha MK. Anti-inflammatory treatments for major depressive disorder: what’s on the horizon? J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6)18ac12630.

15. Salagre E, Fernandes BS, Dodd S, et al. Statins for the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:235-242.

16. Dichtel LE, Nyer M, Dording C, et al. Effects of open-label, adjunctive ganaxolone on persistent depression despite adequate antidepressant treatment in postmenopausal women: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):19m12887.

17. Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(9):951-959.

18. Kalu UG, Sexton CE, Loo CK, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1791-800.

19. Berlim MT, Van den Eynde F, Daskalakis ZJ. Clinical utility of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for treating major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):1-7.

20. Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(1):56-92.

21. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N. Efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and appraisal. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(3):417-428.

22. Norman TR, Olver JS. Agomelatine for depression: expanding the horizons? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(6):647-656.

23. Ramirez-Mahaluf JP, Rozas-Serri E, Ivanovic-Zuvic F, et al. Effectiveness of sleep deprivation in treating acute bipolar depression as augmentation strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:70.

24. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD004366.

25. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:67-86.

26. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42-51.

27. Seshadri A, Adaji A, Orth SS, et al. Exercise, yoga, and tai chi for treatment of major depressive disorder in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;23(1):20r02722.

28. Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, et al. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(11):1068-1083.

29. Mota-Pereira J, Silverio J, Carvalho S, et al. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005-1011.

30. Pilu A, Sorba M, Hardoy MC, et al. Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:8.

31. Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96110.

32. Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD. Are there risks associated with using mindfulness for the treatment of psychopathology? Clinical Practice. 2014;11(4):389-392.

When patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not achieve optimal outcomes after FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies, clinicians look for additional approaches to alleviate their patients’ symptoms. Recent research suggests that several “nontraditional” treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have promise for treatment-resistant depression.

In Part 1 of this article (

Herbal/nutraceutical agents

This category encompasses a variety of commonly available “natural” options patients often ask about and at times self-prescribe. Examples evaluated in clinical trials include:

- vitamin D

- essential fatty acids (omega-3, omega-6)

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe)

- hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort)

- probiotics.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to depression, possibly by lowering serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine concentrations.1-3

A meta-analysis of 3 prospective, observational studies (N = 8,815) found an elevated risk of affective disorders in patients with low vitamin D levels.4 In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis supported a potential role for vitamin D supplementation for patients with treatment-resistant depresssion.5

Toxicity can occur at levels >100 ng/mL, and resulting adverse effects may include weakness, fatigue, sleepiness, headache, loss of appetite, dry mouth, metallic taste, nausea, and vomiting. This vitamin can be considered as an adjunct to standard antidepressants, particularly in patients with treatment-resistant depression who have low vitamin D levels, but regular monitoring is necessary to avoid toxicity.

Essential fatty acids. Protein receptors embedded in lipid membranes and their binding affinities are influenced by omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Thus, essential fatty acids may benefit depression by maintaining membrane integrity and fluidity, as well as via their anti-inflammatory activity.

Continue to: Although results from...

Although results from controlled trials are mixed, a systematic review and meta-analysis of adjunctive nutraceuticals supported a potential role for essential fatty acids, primarily eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), by itself or in combination with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), with total EPA >60%.5 A second meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 2,160) that considered only essential fatty acids concluded that EPA ≥60% at ≤1 g/d could benefit depression.6 Furthermore, omega-3 fatty acids may be helpful as an add-on agent for postpartum depression.7

Be aware that a diet rich in omega-6 greatly increases oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels in adipose tissue, potentially posing a cardiac risk factor. Clinicians need to be aware that self-prescribed use of essential fatty acids is common, and to ask about and monitor their patients’ use of these agents.

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) is an intracellular amino acid and methyl donor. Among other actions, it is involved in the biosynthesis of hormones and neurotransmitters. There is promising but limited preliminary evidence of its efficacy and safety as a monotherapy or for antidepressant augmentation.

- Five out of 6 earlier controlled studies reported SAMe IV (200 to 400 mg/d) or IM (45 to 50 mg/d) was more effective than placebo

- When the above studies were added to 14 subsequent studies for a meta-analysis, 12 of 19 RCTs reported that parenteral or oral SAMe was significantly more effective than placebo for depression (P < .05).

Overall, the safety and tolerability of SAMe are good. Common adverse effects include nausea, mild insomnia, dizziness, irritability, and anxiety. This is another compound widely available without a prescription and at times self-prescribed. It carries an acceptable risk/benefit balance, with decades of experience.

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort) is widely prescribed for depression in China and Europe, typically in doses ranging from 500 to 900 mg/d. Its mechanism of action in depression may relate to inhibition of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine uptake from the synaptic cleft of these interconnecting neurotransmitter systems.

Continue to: A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials...

A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials (N = 3,808) comparing St. John’s Wort with various selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) reported comparable rates of response (pooled relative risk .983, 95% CI .924 to 1.042; P < .001) and remission (pooled relative risk 1.013, 95% CI .892 to 1.134; P < .001).9 Further, there were significantly lower discontinuation/dropout rates (pooled odds ratio .587, 95% CI .478 to 0.697; P < .001) for St. John’s Wort compared with the SSRIs.

Existing evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety is limited (studies ranged from 4 to 12 weeks), as is evidence for patients with more severe depression or high suicidality.

Serious drug interactions include the potential for serotonin syndrome when St. John’s Wort is combined with certain antidepressants, compromised efficacy of benzodiazepines and standard antidepressants, and severe skin reactions to sun exposure. In addition, St. John’s Wort may not be safe to use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Because potential drug interactions can be serious and individuals often self-prescribe this agent, it is important to ask patients about their use of St. John’s Wort, and to be vigilant for such potential adverse interactions.

Probiotics. These agents produce neuroactive substances that act on the brain/gut axis. Preliminary evidence suggests that these “psychobiotics” confer mental health benefits.10-12 Relative to other approaches, their low-risk profile make them an attractive option for some patients.

Anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies

Inflammation is linked to various medical and brain disorders. For example, patients with depression often demonstrate increased levels of peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 and -17) that are known to alter norepinephrine, neuroendocrine (eg, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), and microglia function in addition to neuroplasticity. Thus, targeting inflammation may facilitate the development of novel antidepressants. In addition, these agents may benefit depression associated with comorbid autoimmune disorders, such as psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 RCTs (N = 10,000) found 5 out of 6 anti-inflammatory agents improved depression.13,14 In general, reported disadvantages of anti-inflammatories/immunosuppressants include the potential to block the antidepressant effect of some agents, the risk of opportunistic infections, and an increased risk of suicide.

Continue to: Statins

Statins

In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind trials, 3 statins (lovastatin, atorvastatin, and simvastatin) significantly improved depression scores when used as an adjunctive therapy to fluoxetine and citalopram, compared with adjunctive placebo (N = 165, P < .001).15

Specific adverse effects of statins include headaches, muscle pain (rarely rhabdomyolysis), dizziness, rash, and liver damage. Statins also have the potential for adverse interactions with other medications. Given the limited efficacy literature on statins for depression and the potential for serious adverse effects, these agents probably should be limited to patients with treatment-resistant depression for whom a statin is indicated for a comorbid medical disorder, such as hypercholesteremia.

Neurosteroids

Brexanolone is FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression. It is an IV formulation of the neuroactive steroid hormone allopregnanolone (a metabolite of progesterone), which acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. Unfortunately, the infusion needs to occur over a 60-hour period.

Ganaxolone is an oral analog formulation of allopregnanolone. In an uncontrolled, open-label pilot study, this medication was administered for 8 weeks as an adjunct to an adequately dosed antidepressant to 10 postmenopausal women with persistent MDD.16 Of the 9 women who completed the study, 4 (44%) improved significantly (P < .019) and the benefit was sustained for 2 additional weeks.16 Adverse effects of ganaxolone included dizziness in 60% of participants, and sleepiness and fatigue in all of them with twice-daily dosing. If the FDA approves ganaxolone, it would become an easier-to-administer option to brexanolone.

Zuranolone is an investigational agent being studied as a treatment for postpartum depression. In a double-blind RCT that evaluated 151 women with postpartum depression, those who took oral zuranolone, 30 mg daily at bedtime for 2 weeks, experienced significant reductions in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HDRS-17) scores compared with placebo (P < .003).17 Improvement in core depression symptom ratings was seen as early as Day 3 and persisted through Day 45.

Continue to: The most common...

The most common (≥5%) treatment-emergent adverse effects were somnolence (15%), headache (9%), dizziness (8%), upper respiratory tract infection (8%), diarrhea (6%), and sedation (5%). Two patients experienced a serious adverse event: one who received zuranolone (confusional state) and one who received placebo (pancreatitis). One patient discontinued zuranolone due to adverse effects vs no discontinuations among those who received placebo. The risk of taking zuranolone while breastfeeding is not known.

Device-based strategies

In addition to FDA-cleared approaches (eg, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT], vagus nerve stimulation [VNS], transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS]), other devices have also demonstrated promising results.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) involves delivering weak electrical current to the cerebral cortex through small scalp electrodes to produce the following effects:

- anodal tDCS enhances cortical excitability

- cathodal tDCS reduces cortical excitability.

A typical protocol consists of delivering 1 to 2 mA over 20 minutes with scalp electrodes placed in different configurations based on the targeted symptom(s).

While tDCS has been evaluated as a treatment for various neuropsychiatric disorders, including bipolar depression, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia, most trials have looked at its use for treating depression. Results have been promising but mixed. For example, 1 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (comprising 96 active and 80 sham tDCS courses) reported that active tDCS was superior to a sham procedure (Hedges’ g = 0.743) for symptoms of depression.18 By contrast, another meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (N = 200) did not find a significant difference between active and sham tDCS for response and remission rates.19 More recently, a group of experts created an evidence-based guideline using a systematic review of the controlled trial literature. These authors concluded there is “probable efficacy for anodal tDCS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (with right orbitofrontal cathode) in major depressive episodes without drug resistance but probable inefficacy for drug-resistant major depressive episodes.”20

Continue to: Adverse effects of tDCS...

Adverse effects of tDCS are typically mild but may include persistent skin lesions similar to burns; mania or hypomania; and one reported seizure in a pediatric patient.

Because various over-the-counter direct current stimulation devices are available for purchase at modest cost, clinicians should ask patients if they have been self-administering this treatment.

Chronotherapy strategies

Agomelatine combines serotonergic (5-HT2B and 5-HT2C antagonist) and melatonergic (MT1-MT2 agonist in the suprachiasmatic nucleus) actions that contribute to stabilization of circadian rhythms and subsequent improvement in sleep patterns. Agomelatine (n = 1,274) significantly lowered depression symptoms compared with placebo (n = 689) (standardized mean difference −0.26; P < 3.48×10-11), but the clinical relevance was questionable.21 A recent review of the literature and expert opinion suggest this agent may also have efficacy for anhedonia; however, in placebo-controlled, relapse prevention studies, its long-term efficacy was not consistent.22

Common adverse effects include anxiety; nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain; abnormal dreams and insomnia; dizziness; drowsiness and fatigue; and weight gain. Some reviewers have expressed concerns about agomelatine’s potential for hepatotoxicity and the need for repeated clinical laboratory tests. Although agomelatine is approved outside of the United States, limited efficacy data and the potential for serious adverse effects have precluded FDA approval of this agent.

Sleep deprivation as a treatment technique for depression has been developed over the past 50 years. With total sleep deprivation (TSD) over 1 cycle, patients stay awake for approximately 36 hours, from daytime until the next day’s evening. While 1 to 6 cycles can produce acute antidepressant effects, prompt relapse after sleep recovery is common.

Continue to: In a systematic review...

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies that included a total of 311 patients with bipolar depression23:

- TSD plus medications resulted in a significant decrease in depressive symptoms at 1 week compared with medications alone

- higher response rates were maintained after 3 months with lithium.

Adverse effects commonly include general fatigue and headaches; possible switch into mania with bipolar depression; and rarely, seizures or other unexpected medical conditions (eg, acute coronary syndrome). Presently, this approach is limited to research laboratories with the appropriate sophistication to safely conduct such trials.

Other nontraditional strategies

Cardiovascular exercise, resistance training, mindfulness, and yoga have been shown to decrease severe depressive symptoms when used as adjuncts for patients with treatment-resistant depression, or as monotherapy to treat patients with milder depression.

Exercise. The significant benefits of exercise in various forms as treatment for mild to moderate depression are well described in the literature, but it is less clear if it is effective for treatment-resistant depression. A 2013 Cochrane report24 (39 studies with 2,326 participants total) and 2 meta-analyses undertaken in 2015 (Kvam et al25 included 23 studies with 977 participants, and Schuh et al26 included 25 trials with 1,487 participants) reported that various types of exercise ameliorate depression of differing subtypes and severity, with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Schuh et al26 found that publication bias underestimated effect size. Also, not surprisingly, separate analysis of only higher-quality trials decreased effect size.24-26 A meta-analysis that included tai chi and yoga in addition to aerobic exercise and strength training (25 trials with 2,083 participants) found low to moderate benefit for exercise and yoga.27 Finally, a meta-analysis by Cramer et al28 that included 12 RCTs (N = 619) supported the use of yoga plus controlled breathing techniques as an ancillary treatment for depression.

Two small exercise trials specifically evaluated patients with treatment-resistant depression.29,30 Mota-Pereira et al29 compared 22 participants who walked for 30 to 45 minutes, 5 days a week for 12 weeks in addition to pharmacotherapy with 11 patients who received pharmacotherapy only. Exercise improved all outcomes, including HDRS score (both compared to baseline and to the control group). Moreover, 26% of the exercise group went into remission. Pilu et al30 evaluated strength training as an adjunctive treatment. Participants received 1 hour of strength training twice weekly for 8 months (n = 10), or pharmacotherapy only (n = 20). The adjunct strength training group had a statistically significant (P < .0001) improvement in HDRS scores at the end of the 8 months, whereas the control group did not (P < .28).

Continue to: Adverse effects...

Adverse effects of exercise are typically limited to sprains or strains; rarely, participants experience serious injuries.

Mindfulness-based interventions involve purposely paying attention in the present moment to enhance self-understanding and decrease anxiety about the future and regrets about the past, both of which complicate depression. A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs (N = 578) found this approach significantly reduced depression severity when used as an adjunctive therapy.31 There may be risks if mindfulness-based interventions are practiced incorrectly. For example, some reports have linked mindfulness-based interventions to psychotic episodes, meditation addiction, and antisocial or asocial behavior.32

Bottom Line

Nonpharmacologic options for patients with treatment-resistant depression include herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, and devices. While research suggests some of these approaches are promising, clinicians need to carefully consider potential adverse effects, some of which may be serious.

Related Resources

- Kaur M, Sanches M. Experimental therapeutics in treatmentresistant major depressive disorder. J Exp Pharmacol. 2021;13:181-196.

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Citalopram • Celexa

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lovastatin • Altoprev, Mevacor

Minocycline • Dynacin, Minocin

Simvastatin • Flolipid, Zocor

When patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) do not achieve optimal outcomes after FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies, clinicians look for additional approaches to alleviate their patients’ symptoms. Recent research suggests that several “nontraditional” treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have promise for treatment-resistant depression.

In Part 1 of this article (

Herbal/nutraceutical agents

This category encompasses a variety of commonly available “natural” options patients often ask about and at times self-prescribe. Examples evaluated in clinical trials include:

- vitamin D

- essential fatty acids (omega-3, omega-6)

- S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe)

- hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort)

- probiotics.

Vitamin D deficiency has been linked to depression, possibly by lowering serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine concentrations.1-3

A meta-analysis of 3 prospective, observational studies (N = 8,815) found an elevated risk of affective disorders in patients with low vitamin D levels.4 In addition, a systematic review and meta-analysis supported a potential role for vitamin D supplementation for patients with treatment-resistant depresssion.5

Toxicity can occur at levels >100 ng/mL, and resulting adverse effects may include weakness, fatigue, sleepiness, headache, loss of appetite, dry mouth, metallic taste, nausea, and vomiting. This vitamin can be considered as an adjunct to standard antidepressants, particularly in patients with treatment-resistant depression who have low vitamin D levels, but regular monitoring is necessary to avoid toxicity.

Essential fatty acids. Protein receptors embedded in lipid membranes and their binding affinities are influenced by omega-3 and omega-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Thus, essential fatty acids may benefit depression by maintaining membrane integrity and fluidity, as well as via their anti-inflammatory activity.

Continue to: Although results from...

Although results from controlled trials are mixed, a systematic review and meta-analysis of adjunctive nutraceuticals supported a potential role for essential fatty acids, primarily eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), by itself or in combination with docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), with total EPA >60%.5 A second meta-analysis of 26 studies (N = 2,160) that considered only essential fatty acids concluded that EPA ≥60% at ≤1 g/d could benefit depression.6 Furthermore, omega-3 fatty acids may be helpful as an add-on agent for postpartum depression.7

Be aware that a diet rich in omega-6 greatly increases oxidized low-density lipoprotein levels in adipose tissue, potentially posing a cardiac risk factor. Clinicians need to be aware that self-prescribed use of essential fatty acids is common, and to ask about and monitor their patients’ use of these agents.

S-adenosyl-L-methionine (SAMe) is an intracellular amino acid and methyl donor. Among other actions, it is involved in the biosynthesis of hormones and neurotransmitters. There is promising but limited preliminary evidence of its efficacy and safety as a monotherapy or for antidepressant augmentation.

- Five out of 6 earlier controlled studies reported SAMe IV (200 to 400 mg/d) or IM (45 to 50 mg/d) was more effective than placebo

- When the above studies were added to 14 subsequent studies for a meta-analysis, 12 of 19 RCTs reported that parenteral or oral SAMe was significantly more effective than placebo for depression (P < .05).

Overall, the safety and tolerability of SAMe are good. Common adverse effects include nausea, mild insomnia, dizziness, irritability, and anxiety. This is another compound widely available without a prescription and at times self-prescribed. It carries an acceptable risk/benefit balance, with decades of experience.

Hypericum perforatum (St. John’s Wort) is widely prescribed for depression in China and Europe, typically in doses ranging from 500 to 900 mg/d. Its mechanism of action in depression may relate to inhibition of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine uptake from the synaptic cleft of these interconnecting neurotransmitter systems.

Continue to: A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials...

A meta-analysis of 7 clinical trials (N = 3,808) comparing St. John’s Wort with various selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) reported comparable rates of response (pooled relative risk .983, 95% CI .924 to 1.042; P < .001) and remission (pooled relative risk 1.013, 95% CI .892 to 1.134; P < .001).9 Further, there were significantly lower discontinuation/dropout rates (pooled odds ratio .587, 95% CI .478 to 0.697; P < .001) for St. John’s Wort compared with the SSRIs.

Existing evidence on the long-term efficacy and safety is limited (studies ranged from 4 to 12 weeks), as is evidence for patients with more severe depression or high suicidality.

Serious drug interactions include the potential for serotonin syndrome when St. John’s Wort is combined with certain antidepressants, compromised efficacy of benzodiazepines and standard antidepressants, and severe skin reactions to sun exposure. In addition, St. John’s Wort may not be safe to use during pregnancy or while breastfeeding. Because potential drug interactions can be serious and individuals often self-prescribe this agent, it is important to ask patients about their use of St. John’s Wort, and to be vigilant for such potential adverse interactions.

Probiotics. These agents produce neuroactive substances that act on the brain/gut axis. Preliminary evidence suggests that these “psychobiotics” confer mental health benefits.10-12 Relative to other approaches, their low-risk profile make them an attractive option for some patients.

Anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies

Inflammation is linked to various medical and brain disorders. For example, patients with depression often demonstrate increased levels of peripheral blood inflammatory biomarkers (such as C-reactive protein and interleukin-6 and -17) that are known to alter norepinephrine, neuroendocrine (eg, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis), and microglia function in addition to neuroplasticity. Thus, targeting inflammation may facilitate the development of novel antidepressants. In addition, these agents may benefit depression associated with comorbid autoimmune disorders, such as psoriasis or rheumatoid arthritis. A systematic review and meta-analysis of 36 RCTs (N = 10,000) found 5 out of 6 anti-inflammatory agents improved depression.13,14 In general, reported disadvantages of anti-inflammatories/immunosuppressants include the potential to block the antidepressant effect of some agents, the risk of opportunistic infections, and an increased risk of suicide.

Continue to: Statins

Statins

In a meta-analysis of 3 randomized, double-blind trials, 3 statins (lovastatin, atorvastatin, and simvastatin) significantly improved depression scores when used as an adjunctive therapy to fluoxetine and citalopram, compared with adjunctive placebo (N = 165, P < .001).15

Specific adverse effects of statins include headaches, muscle pain (rarely rhabdomyolysis), dizziness, rash, and liver damage. Statins also have the potential for adverse interactions with other medications. Given the limited efficacy literature on statins for depression and the potential for serious adverse effects, these agents probably should be limited to patients with treatment-resistant depression for whom a statin is indicated for a comorbid medical disorder, such as hypercholesteremia.

Neurosteroids

Brexanolone is FDA-approved for the treatment of postpartum depression. It is an IV formulation of the neuroactive steroid hormone allopregnanolone (a metabolite of progesterone), which acts as a positive allosteric modulator of the GABA-A receptor. Unfortunately, the infusion needs to occur over a 60-hour period.

Ganaxolone is an oral analog formulation of allopregnanolone. In an uncontrolled, open-label pilot study, this medication was administered for 8 weeks as an adjunct to an adequately dosed antidepressant to 10 postmenopausal women with persistent MDD.16 Of the 9 women who completed the study, 4 (44%) improved significantly (P < .019) and the benefit was sustained for 2 additional weeks.16 Adverse effects of ganaxolone included dizziness in 60% of participants, and sleepiness and fatigue in all of them with twice-daily dosing. If the FDA approves ganaxolone, it would become an easier-to-administer option to brexanolone.

Zuranolone is an investigational agent being studied as a treatment for postpartum depression. In a double-blind RCT that evaluated 151 women with postpartum depression, those who took oral zuranolone, 30 mg daily at bedtime for 2 weeks, experienced significant reductions in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 (HDRS-17) scores compared with placebo (P < .003).17 Improvement in core depression symptom ratings was seen as early as Day 3 and persisted through Day 45.

Continue to: The most common...

The most common (≥5%) treatment-emergent adverse effects were somnolence (15%), headache (9%), dizziness (8%), upper respiratory tract infection (8%), diarrhea (6%), and sedation (5%). Two patients experienced a serious adverse event: one who received zuranolone (confusional state) and one who received placebo (pancreatitis). One patient discontinued zuranolone due to adverse effects vs no discontinuations among those who received placebo. The risk of taking zuranolone while breastfeeding is not known.

Device-based strategies

In addition to FDA-cleared approaches (eg, electroconvulsive therapy [ECT], vagus nerve stimulation [VNS], transcranial magnetic stimulation [TMS]), other devices have also demonstrated promising results.

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) involves delivering weak electrical current to the cerebral cortex through small scalp electrodes to produce the following effects:

- anodal tDCS enhances cortical excitability

- cathodal tDCS reduces cortical excitability.

A typical protocol consists of delivering 1 to 2 mA over 20 minutes with scalp electrodes placed in different configurations based on the targeted symptom(s).

While tDCS has been evaluated as a treatment for various neuropsychiatric disorders, including bipolar depression, Parkinson’s disease, and schizophrenia, most trials have looked at its use for treating depression. Results have been promising but mixed. For example, 1 meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (comprising 96 active and 80 sham tDCS courses) reported that active tDCS was superior to a sham procedure (Hedges’ g = 0.743) for symptoms of depression.18 By contrast, another meta-analysis of 6 RCTs (N = 200) did not find a significant difference between active and sham tDCS for response and remission rates.19 More recently, a group of experts created an evidence-based guideline using a systematic review of the controlled trial literature. These authors concluded there is “probable efficacy for anodal tDCS of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) (with right orbitofrontal cathode) in major depressive episodes without drug resistance but probable inefficacy for drug-resistant major depressive episodes.”20

Continue to: Adverse effects of tDCS...

Adverse effects of tDCS are typically mild but may include persistent skin lesions similar to burns; mania or hypomania; and one reported seizure in a pediatric patient.

Because various over-the-counter direct current stimulation devices are available for purchase at modest cost, clinicians should ask patients if they have been self-administering this treatment.

Chronotherapy strategies

Agomelatine combines serotonergic (5-HT2B and 5-HT2C antagonist) and melatonergic (MT1-MT2 agonist in the suprachiasmatic nucleus) actions that contribute to stabilization of circadian rhythms and subsequent improvement in sleep patterns. Agomelatine (n = 1,274) significantly lowered depression symptoms compared with placebo (n = 689) (standardized mean difference −0.26; P < 3.48×10-11), but the clinical relevance was questionable.21 A recent review of the literature and expert opinion suggest this agent may also have efficacy for anhedonia; however, in placebo-controlled, relapse prevention studies, its long-term efficacy was not consistent.22

Common adverse effects include anxiety; nausea, vomiting, and stomach pain; abnormal dreams and insomnia; dizziness; drowsiness and fatigue; and weight gain. Some reviewers have expressed concerns about agomelatine’s potential for hepatotoxicity and the need for repeated clinical laboratory tests. Although agomelatine is approved outside of the United States, limited efficacy data and the potential for serious adverse effects have precluded FDA approval of this agent.

Sleep deprivation as a treatment technique for depression has been developed over the past 50 years. With total sleep deprivation (TSD) over 1 cycle, patients stay awake for approximately 36 hours, from daytime until the next day’s evening. While 1 to 6 cycles can produce acute antidepressant effects, prompt relapse after sleep recovery is common.

Continue to: In a systematic review...

In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 7 studies that included a total of 311 patients with bipolar depression23:

- TSD plus medications resulted in a significant decrease in depressive symptoms at 1 week compared with medications alone

- higher response rates were maintained after 3 months with lithium.

Adverse effects commonly include general fatigue and headaches; possible switch into mania with bipolar depression; and rarely, seizures or other unexpected medical conditions (eg, acute coronary syndrome). Presently, this approach is limited to research laboratories with the appropriate sophistication to safely conduct such trials.

Other nontraditional strategies

Cardiovascular exercise, resistance training, mindfulness, and yoga have been shown to decrease severe depressive symptoms when used as adjuncts for patients with treatment-resistant depression, or as monotherapy to treat patients with milder depression.

Exercise. The significant benefits of exercise in various forms as treatment for mild to moderate depression are well described in the literature, but it is less clear if it is effective for treatment-resistant depression. A 2013 Cochrane report24 (39 studies with 2,326 participants total) and 2 meta-analyses undertaken in 2015 (Kvam et al25 included 23 studies with 977 participants, and Schuh et al26 included 25 trials with 1,487 participants) reported that various types of exercise ameliorate depression of differing subtypes and severity, with effect sizes ranging from small to large. Schuh et al26 found that publication bias underestimated effect size. Also, not surprisingly, separate analysis of only higher-quality trials decreased effect size.24-26 A meta-analysis that included tai chi and yoga in addition to aerobic exercise and strength training (25 trials with 2,083 participants) found low to moderate benefit for exercise and yoga.27 Finally, a meta-analysis by Cramer et al28 that included 12 RCTs (N = 619) supported the use of yoga plus controlled breathing techniques as an ancillary treatment for depression.

Two small exercise trials specifically evaluated patients with treatment-resistant depression.29,30 Mota-Pereira et al29 compared 22 participants who walked for 30 to 45 minutes, 5 days a week for 12 weeks in addition to pharmacotherapy with 11 patients who received pharmacotherapy only. Exercise improved all outcomes, including HDRS score (both compared to baseline and to the control group). Moreover, 26% of the exercise group went into remission. Pilu et al30 evaluated strength training as an adjunctive treatment. Participants received 1 hour of strength training twice weekly for 8 months (n = 10), or pharmacotherapy only (n = 20). The adjunct strength training group had a statistically significant (P < .0001) improvement in HDRS scores at the end of the 8 months, whereas the control group did not (P < .28).

Continue to: Adverse effects...

Adverse effects of exercise are typically limited to sprains or strains; rarely, participants experience serious injuries.

Mindfulness-based interventions involve purposely paying attention in the present moment to enhance self-understanding and decrease anxiety about the future and regrets about the past, both of which complicate depression. A meta-analysis of 12 RCTs (N = 578) found this approach significantly reduced depression severity when used as an adjunctive therapy.31 There may be risks if mindfulness-based interventions are practiced incorrectly. For example, some reports have linked mindfulness-based interventions to psychotic episodes, meditation addiction, and antisocial or asocial behavior.32

Bottom Line

Nonpharmacologic options for patients with treatment-resistant depression include herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, and devices. While research suggests some of these approaches are promising, clinicians need to carefully consider potential adverse effects, some of which may be serious.

Related Resources

- Kaur M, Sanches M. Experimental therapeutics in treatmentresistant major depressive disorder. J Exp Pharmacol. 2021;13:181-196.

- Janicak PG. What’s new in transcranial magnetic stimulation. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(3):10-16.

Drug Brand Names

Atorvastatin • Lipitor

Brexanolone • Zulresso

Citalopram • Celexa

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Lovastatin • Altoprev, Mevacor

Minocycline • Dynacin, Minocin

Simvastatin • Flolipid, Zocor

1. Pittampalli S, Mekala HM, Upadhyayula, S, et al. Does vitamin D deficiency cause depression? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):17l02263.

2. Parker GB, Brotchie H, Graham RK. Vitamin D and depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:56-61.

3. Berridge MJ. Vitamin D and depression: cellular and regulatory mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69(2):80-92.

4. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

5. Sarris J, Murphy J, Mischoulon D, et al. Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(6);575-587.

6. Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):190.

7. Mocking RJT, Steijn K, Roos C, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for perinatal depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):19r13106.

8. Sharma A, Gerbarg P, Bottiglieri T, et al; Work Group of the American Psychiatric Association Council on Research. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for neuropsychiatric disorders: a clinician-oriented review of research. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e656-e667.

9. Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CY. Clinical use of hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017;210:211-221.

10. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):483.

11. Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;102:13-23.

12. Wallace CJK, Milev RV. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of probiotics on depression: clinical results from an open-label pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12(132):618279.

13. Köhler-Forsberg O, N Lyndholm C, Hjorthøj C, et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(5):404-419.

14. Jha MK. Anti-inflammatory treatments for major depressive disorder: what’s on the horizon? J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6)18ac12630.

15. Salagre E, Fernandes BS, Dodd S, et al. Statins for the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:235-242.

16. Dichtel LE, Nyer M, Dording C, et al. Effects of open-label, adjunctive ganaxolone on persistent depression despite adequate antidepressant treatment in postmenopausal women: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):19m12887.

17. Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(9):951-959.

18. Kalu UG, Sexton CE, Loo CK, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1791-800.

19. Berlim MT, Van den Eynde F, Daskalakis ZJ. Clinical utility of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for treating major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):1-7.

20. Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(1):56-92.

21. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N. Efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and appraisal. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(3):417-428.

22. Norman TR, Olver JS. Agomelatine for depression: expanding the horizons? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(6):647-656.

23. Ramirez-Mahaluf JP, Rozas-Serri E, Ivanovic-Zuvic F, et al. Effectiveness of sleep deprivation in treating acute bipolar depression as augmentation strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:70.

24. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD004366.

25. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:67-86.

26. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42-51.

27. Seshadri A, Adaji A, Orth SS, et al. Exercise, yoga, and tai chi for treatment of major depressive disorder in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;23(1):20r02722.

28. Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, et al. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(11):1068-1083.

29. Mota-Pereira J, Silverio J, Carvalho S, et al. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005-1011.

30. Pilu A, Sorba M, Hardoy MC, et al. Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:8.

31. Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96110.

32. Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD. Are there risks associated with using mindfulness for the treatment of psychopathology? Clinical Practice. 2014;11(4):389-392.

1. Pittampalli S, Mekala HM, Upadhyayula, S, et al. Does vitamin D deficiency cause depression? Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2018;20(5):17l02263.

2. Parker GB, Brotchie H, Graham RK. Vitamin D and depression. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:56-61.

3. Berridge MJ. Vitamin D and depression: cellular and regulatory mechanisms. Pharmacol Rev. 2017;69(2):80-92.

4. Anglin RE, Samaan Z, Walter SD, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and depression in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202:100-107.

5. Sarris J, Murphy J, Mischoulon D, et al. Adjunctive nutraceuticals for depression: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am J Psychiatry 2016;173(6);575-587.

6. Liao Y, Xie B, Zhang H, et al. Efficacy of omega-3 PUFAs in depression: a meta-analysis. Transl Psychiatry. 2019;9(1):190.

7. Mocking RJT, Steijn K, Roos C, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid supplementation for perinatal depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(5):19r13106.

8. Sharma A, Gerbarg P, Bottiglieri T, et al; Work Group of the American Psychiatric Association Council on Research. S-Adenosylmethionine (SAMe) for neuropsychiatric disorders: a clinician-oriented review of research. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e656-e667.

9. Ng QX, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CY. Clinical use of hypericum perforatum (St John’s wort) in depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2017;210:211-221.

10. Huang R, Wang K, Hu J. Effect of probiotics on depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2016;8(8):483.

11. Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE. Prebiotics and probiotics for depression and anxiety: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;102:13-23.

12. Wallace CJK, Milev RV. The efficacy, safety, and tolerability of probiotics on depression: clinical results from an open-label pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12(132):618279.

13. Köhler-Forsberg O, N Lyndholm C, Hjorthøj C, et al. Efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatment on major depressive disorder or depressive symptoms: meta-analysis of clinical trials. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2019;139(5):404-419.

14. Jha MK. Anti-inflammatory treatments for major depressive disorder: what’s on the horizon? J Clin Psychiatry. 2019;80(6)18ac12630.

15. Salagre E, Fernandes BS, Dodd S, et al. Statins for the treatment of depression: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:235-242.

16. Dichtel LE, Nyer M, Dording C, et al. Effects of open-label, adjunctive ganaxolone on persistent depression despite adequate antidepressant treatment in postmenopausal women: a pilot study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):19m12887.

17. Deligiannidis KM, Meltzer-Brody S, Gunduz-Bruce H, et al. Effect of zuranolone vs placebo in postpartum depression: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(9):951-959.

18. Kalu UG, Sexton CE, Loo CK, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation in the treatment of major depression: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1791-800.

19. Berlim MT, Van den Eynde F, Daskalakis ZJ. Clinical utility of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for treating major depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind and sham-controlled trials. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47(1):1-7.

20. Lefaucheur JP, Antal A, Ayache SS, et al. Evidence-based guidelines on the therapeutic use of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS). Clin Neurophysiol. 2017;128(1):56-92.

21. Singh SP, Singh V, Kar N. Efficacy of agomelatine in major depressive disorder: meta-analysis and appraisal. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(3):417-428.

22. Norman TR, Olver JS. Agomelatine for depression: expanding the horizons? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(6):647-656.

23. Ramirez-Mahaluf JP, Rozas-Serri E, Ivanovic-Zuvic F, et al. Effectiveness of sleep deprivation in treating acute bipolar depression as augmentation strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:70.

24. Cooney GM, Dwan K, Greig CA, et al. Exercise for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD004366.

25. Kvam S, Kleppe CL, Nordhus IH, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2016;202:67-86.

26. Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Richards J, et al. Exercise as a treatment for depression: a meta-analysis adjusting for publication bias. J Psychiatr Res. 2016;77:42-51.

27. Seshadri A, Adaji A, Orth SS, et al. Exercise, yoga, and tai chi for treatment of major depressive disorder in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;23(1):20r02722.

28. Cramer H, Lauche R, Langhorst J, et al. Yoga for depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(11):1068-1083.

29. Mota-Pereira J, Silverio J, Carvalho S, et al. Moderate exercise improves depression parameters in treatment-resistant patients with major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1005-1011.

30. Pilu A, Sorba M, Hardoy MC, et al. Efficacy of physical activity in the adjunctive treatment of major depressive disorders: preliminary results. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 2007;3:8.

31. Strauss C, Cavanagh K, Oliver A, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for people diagnosed with a current episode of an anxiety or depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e96110.

32. Shonin E, Van Gordon W, Griffiths MD. Are there risks associated with using mindfulness for the treatment of psychopathology? Clinical Practice. 2014;11(4):389-392.

Nontraditional therapies for treatment-resistant depression

Presently, FDA-approved first-line treatments and standard adjunctive strategies (eg, lithium, thyroid supplementation, stimulants, second-generation antipsychotics) for major depressive disorder (MDD) often produce less-than-desired outcomes while carrying a potentially substantial safety and tolerability burden. The lack of clinically useful and individual-based biomarkers (eg, genetic, neurophysiological, imaging) is a major obstacle to enhancing treatment efficacy and/or decreasing associated adverse effects (AEs). While the discovery of such tools is being aggressively pursued and ultimately will facilitate a more precision-based choice of therapy, empirical strategies remain our primary approach.

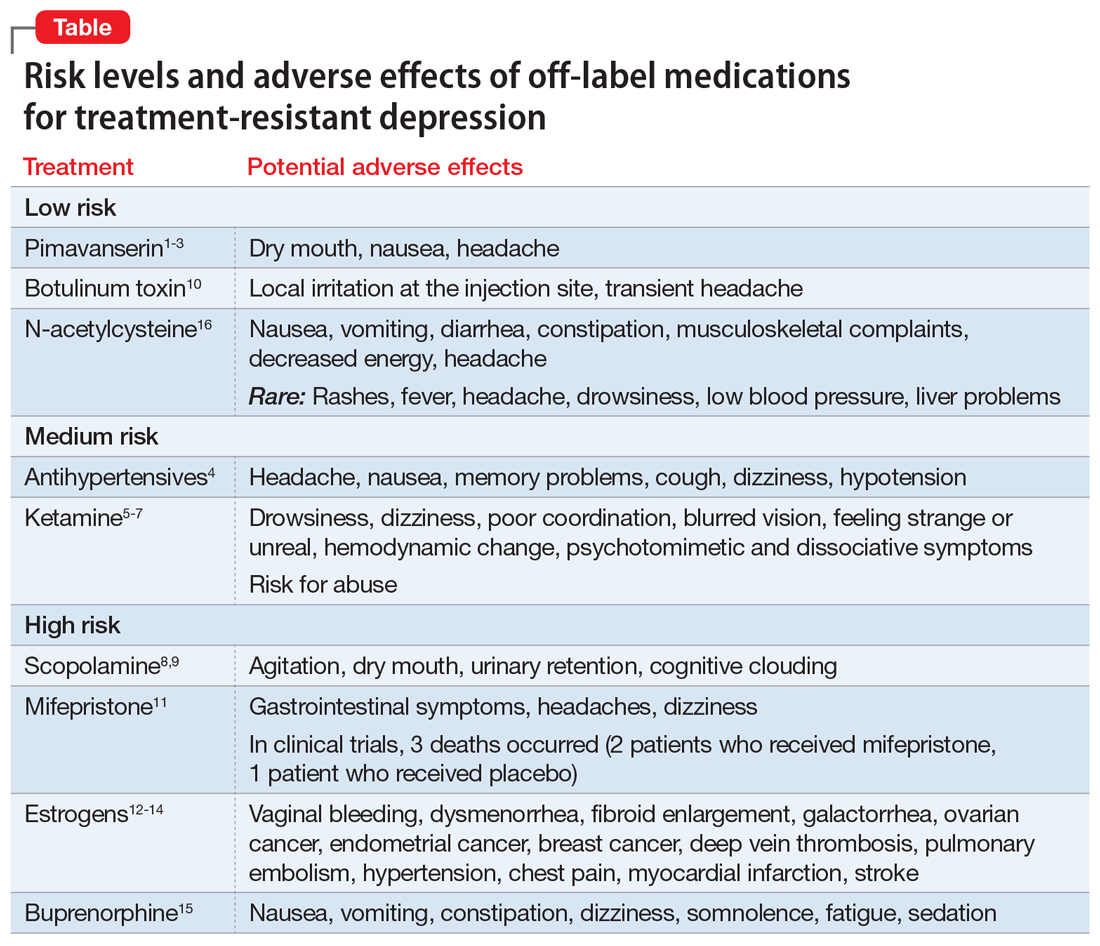

In controlled trials, several nontraditional treatments used primarily as adjuncts to standard antidepressants have shown promise. These include “repurposed” (off-label) medications, herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

Importantly, some nontraditional treatments also demonstrate AEs (Table1-16). With a careful consideration of the risk/benefit balance, this article reviews some of the better-studied treatment options for patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD). In Part 1, we will examine off-label medications. In Part 2, we will review other nontraditional approaches to TRD, including herbal/nutraceuticals, anti-inflammatory/immune system therapies, device-based treatments, and other alternative approaches.

We believe this review will help clinicians who need to formulate a different approach after their patient with depression is not helped by traditional first-, second-, and third-line treatments. The potential options discussed in Part 1 of this article are categorized based on their putative mechanism of action (MOA) for depression.

Serotonergic and noradrenergic strategies

Pimavanserin is FDA-approved for treatment of Parkinson’s psychosis. Its potential MOA as an adjunctive strategy for MDD may involve 5-HT2A antagonist and inverse agonist receptor activity, as well as lesser effects at the 5-HT2Creceptor.

A 2-stage, 5-week randomized controlled trial (RCT) (CLARITY; N = 207) found adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) produced a robust antidepressant effect vs placebo in patients whose depression did not respond to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).1 Furthermore, a secondary analysis of the data suggested that pimavanserin also improved sleepiness (P < .0003) and daily functioning (P < .014) at Week 5.2

Unfortunately, two 6-week, Phase III RCTs (CLARITY-2 and -3; N = 298) did not find a statistically significant difference between active treatment and placebo. This was based on change in the primary outcome measure (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale-17 score) when adjunctive pimavanserin (34 mg/d) was added to an SSRI or SNRI in patients with TRD.3 There was, however, a significant difference favoring active treatment over placebo based on the Clinical Global Impression–Severity score.

Continue to: In these trials...

In these trials, pimavanserin was generally well-tolerated. The most common AEs were dry mouth, nausea, and headache. Pimavanserin has minimal activity at norepinephrine, dopamine, histamine, or acetylcholine receptors, thus avoiding AEs associated with these receptor interactions.

Given the mixed efficacy results of existing trials, further studies are needed to clarify this agent’s overall risk/benefit in the context of TRD.

Antihypertensive medications

Emerging data suggest that some beta-adrenergic blockers, angiotensin-inhibiting agents, and calcium antagonists are associated with a decreased incidence of depression. A large 2020 study (N = 3,747,190) used population-based Danish registries (2005 to 2015) to evaluate if any of the 41 most commonly prescribed antihypertensive medications were associated with the diagnosis of depressive disorder or use of antidepressants.4 These researchers found that enalapril, ramipril, amlodipine, propranolol, atenolol, bisoprolol, carvedilol (P < .001), and verapamil (P < .004) were strongly associated with a decreased risk of depression.4

Adverse effects across these different classes of antihypertensives are well characterized, can be substantial, and commonly are related to their impact on cardiovascular function (eg, hypotension). Clinically, these agents may be potential adjuncts for patients with TRD who need antihypertensive therapy. Their use and the choice of specific agent should only be determined in consultation with the patient’s primary care physician (PCP) or appropriate specialist.

Glutamatergic strategies

Ketamine is a dissociative anesthetic and analgesic. Its MOA for treating depression appears to occur primarily through antagonist activity at the N-methyl-

Continue to: Many published studies...

Many published studies and reviews have described ketamine’s role for treating MDD. Several studies have reported that low-dose (0.5 mg/kg) IV ketamine infusions can rapidly attenuate severe episodes of MDD as well as associated suicidality. For example, a meta-analysis of 9 RCTs (N = 368) comparing ketamine to placebo for acute treatment of unipolar and bipolar depression reported superior therapeutic effects with active treatment at 24 hours, 72 hours, and 7 days.6 The response and remission rates for ketamine were 52% and 21% at 24 hours; 48% and 24% at 72 hours; and 40% and 26% at 7 days, respectively.6

The most commonly reported AEs during the 4 hours after ketamine infusion included7:

- drowsiness, dizziness, poor coordination

- blurred vision, feeling strange or unreal

- hemodynamic changes (approximately 33%)

- small but significant (P < .05) increases in psychotomimetic and dissociative symptoms.

Because some individuals use ketamine recreationally, this agent also carries the risk of abuse.

Research is ongoing on strategies for long-term maintenance ketamine treatment, and the results of both short- and long-term trials will require careful scrutiny to better assess this agent’s safety and tolerability. Clinicians should first consider esketamine—the S-enantiomer of ketamine—because an intranasal formulation of this agent is FDA-approved for treating patients with TRD or MDD with suicidality when administered in a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy–certified setting.

Cholinergic strategies

Scopolamine is a potent muscarinic receptor antagonist used to prevent nausea and vomiting caused by motion sickness or medications used during surgery. Its use for MDD is based on the theory that muscarinic receptors may be hypersensitive in mood disorders.

Continue to: Several double-blind RCTs...

Several double-blind RCTs of patients with unipolar or bipolar depression that used 3 pulsed IV infusions (4.0 mcg/kg) over 15 minutes found a rapid, robust antidepressant effect with scopolamine vs placebo.8,9 The oral formulation might also be effective, but would not have a rapid onset.

Common adverse effects of scopolamine include agitation, dry mouth, urinary retention, and cognitive clouding. Given scopolamine’s substantial AE profile, it should be considered only for patients with TRD who could also benefit from the oral formulation for the medical indications noted above, should generally be avoided in older patients, and should be prescribed in consultation with the patient’s PCP.

Botulinum toxin. This neurotoxin inhibits acetylcholine release. It is used to treat disorders characterized by abnormal muscular contraction, such as strabismus, blepharospasm, and chronic pain syndromes. Its MOA for depression may involve its paralytic effects after injection into the glabella forehead muscle (based on the facial feedback hypothesis), as well as modulation of neurotransmitters implicated in the pathophysiology of depression.