User login

Cervical cancer screening: Should my practice switch to primary HPV testing?

How should I be approaching cervical cancer screening: with primary human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, or cotesting? We get this question all the time from clinicians. Although they have heard of the latest cervical cancer screening guidelines for stand-alone “primary” HPV testing, they are still ordering cervical cytology (Papanicolaou, or Pap, test) for women aged 21 to 29 years and cotesting (cervical cytology with HPV testing) for women with a cervix aged 30 and older.

Changes in cervical cancer testing guidance

Cervical cancer occurs in more than 13,000 women in the United States annually.1 High-risk types of HPV—the known cause of cervical cancer—also cause a large majority of cancers of the anus, vagina, vulva, and oropharynx.2

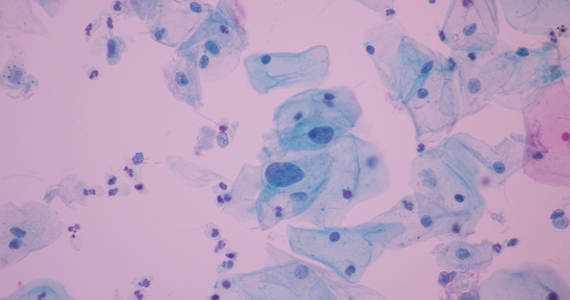

Cervical cancer screening programs in the United States have markedly decreased the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer since introduction of the Pap smear in the 1950s. In 2000, HPV testing was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a reflex test to a Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). HPV testing was then approved for use with cytology as a cotest in 2003 and subsequently as a primary stand-alone test in 2014.

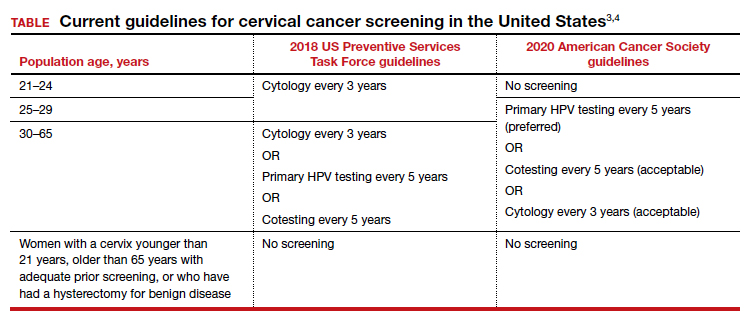

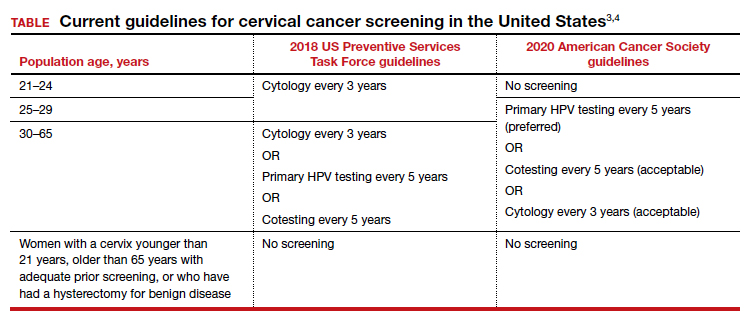

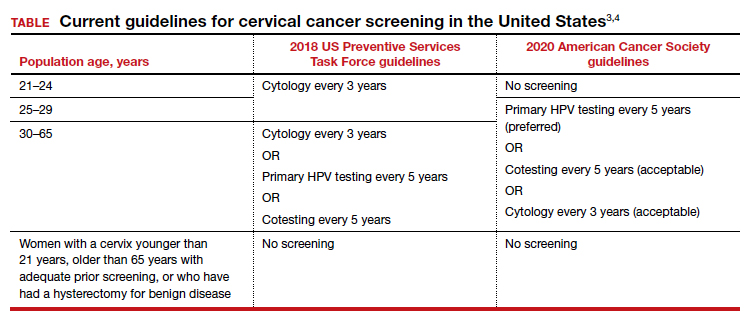

Recently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) released new cervical screening guidelines that depart from prior guidelines.3 They recommend not to screen 21- to 24-year-olds and to start screening at age 25 until age 65 with the preferred strategy of primary HPV testing every 5 years, using an FDA-approved HPV test. Alternative screening strategies are cytology (Pap) every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years.

The 2018 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines differ from the ACS guidelines. The USPSTF recommends cytology every 3 years as the preferred method for women with a cervix who are aged 21 to 29 years and, for women with a cervix who are aged 30 to 65 years, the option for cytology every 3 years, primary HPV testing every 5 years, or cotesting every 5 years (TABLE).4

Why the reluctance to switch to HPV testing?

Despite FDA approval in 2014 for primary HPV testing and concurrent professional society guidance to use this testing strategy in women with a cervix who are aged 25 years and older, few practices in the United States have switched over to primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening.5,6 Several reasons underlie this inertia:

- Many practices currently use HPV tests that are not FDA approved for primary HPV testing.

- Until recently, national screening guidelines did not recommend primary HPV testing as the preferred testing strategy.

- Long-established guidance on the importance of regular cervical cytology screening promoted by the ACS and others (which especially impacts women with a cervix older than age 50 who guide their younger daughters) will rely on significant re-education to move away from the established “Pap smear” cultural icon to a new approach.

- Last but not least, companies that manufacture HPV tests and laboratories integrated to offer such tests not yet approved for primary screening are promoting reliance on the prior proven cotest strategy. They have lobbied to preserve cotesting as a primary test, with some laboratory database studies showing gaps in detection with HPV test screening alone.7-9

Currently, the FDA-approved HPV tests for primary HPV screening include the Cobas HPV test (Roche) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Both are DNA tests for 14 high-risk types of HPV that include genotyping for HPV 16 and 18.

Continue to: Follow the evidence...

Follow the evidence

Several trials in Europe and Canada provide supporting evidence for primary HPV testing, and many European countries have moved to primary HPV testing as their preferred screening method.10,11 The new ACS guidelines put us more in sync with the rest of the world, where HPV testing is the dominant strategy.

It is true that doing additional tests will find more disease; cotesting has been shown to very minimally increase detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3 (CIN 2/3) compared with HPV testing alone, but it incurs many more costs and procedures.12 The vast majority of cervical cancer is HPV positive, and cytology still can be used as a triage to primary HPV screening until tests with better sensitivity and/or specificity (such as dual stain and methylation) can be employed to reduce unnecessary “false-positive” driven procedures.

As mentioned, many strong forces are trying to keep cotesting as the preferred strategy. It is important for clinicians to recognize the corporate investment into screening platforms, relationships, and products that underlie some of these efforts so as not to be unfairly influenced by their lobbying. Data from well-conducted, high-quality studies should be the evidence on which one bases a cervical cancer screening strategy.

Innovation catalyzes change

We acknowledge that it is difficult to give up something you have been doing for decades, so there is natural resistance by both patients and clinicians to move the Pap smear into a secondary role. But the data support primary HPV testing as the best screening option from a public health perspective.

At some point, hopefully soon, primary HPV testing will receive approval for self-sampling; this has the potential to reach patients in rural or remote locations who may otherwise not get screened for cervical cancer.13

The 2019 risk-based management guidelines from the ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) also incorporate the use of HPV-based screening and surveillance after abnormal tests or colposcopy. Therefore, switching to primary HPV screening will not impact your ability to follow patients appropriately based on clinical guidelines.

Our advice to clinicians is to switch to primary HPV screening now if possible. If that is not feasible, continue your current strategy until you can make the change. And, of course, we recommend that you implement an HPV vaccination program in your practice to maximize primary prevention of HPV-related cancers. ●

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers–United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:661-666.

- Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, KristAH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337.

- Cooper CP, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer screening intervals preferred by US women. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:389-394.

- Austin RM, Onisko A, Zhao C. Enhanced detection of cervical cancer and precancer through use of imaged liquid-based cytology in routine cytology and HPV cotesting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150:385-392.

- Kaufman HW, Alagia DP, Chen Z, et al. Contributions of liquid-based (Papanicolaou) cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cotesting for detection of cervical cancer and precancer in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:510-516.

- Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, et al. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:282-288.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Kim JJ, Burger EA, Regan C, et al. Screening for cervical cancer in primary care: a decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:706-714.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al; on behalf of the Collaboration on Self-Sampling and HPV Testing. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.

How should I be approaching cervical cancer screening: with primary human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, or cotesting? We get this question all the time from clinicians. Although they have heard of the latest cervical cancer screening guidelines for stand-alone “primary” HPV testing, they are still ordering cervical cytology (Papanicolaou, or Pap, test) for women aged 21 to 29 years and cotesting (cervical cytology with HPV testing) for women with a cervix aged 30 and older.

Changes in cervical cancer testing guidance

Cervical cancer occurs in more than 13,000 women in the United States annually.1 High-risk types of HPV—the known cause of cervical cancer—also cause a large majority of cancers of the anus, vagina, vulva, and oropharynx.2

Cervical cancer screening programs in the United States have markedly decreased the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer since introduction of the Pap smear in the 1950s. In 2000, HPV testing was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a reflex test to a Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). HPV testing was then approved for use with cytology as a cotest in 2003 and subsequently as a primary stand-alone test in 2014.

Recently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) released new cervical screening guidelines that depart from prior guidelines.3 They recommend not to screen 21- to 24-year-olds and to start screening at age 25 until age 65 with the preferred strategy of primary HPV testing every 5 years, using an FDA-approved HPV test. Alternative screening strategies are cytology (Pap) every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years.

The 2018 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines differ from the ACS guidelines. The USPSTF recommends cytology every 3 years as the preferred method for women with a cervix who are aged 21 to 29 years and, for women with a cervix who are aged 30 to 65 years, the option for cytology every 3 years, primary HPV testing every 5 years, or cotesting every 5 years (TABLE).4

Why the reluctance to switch to HPV testing?

Despite FDA approval in 2014 for primary HPV testing and concurrent professional society guidance to use this testing strategy in women with a cervix who are aged 25 years and older, few practices in the United States have switched over to primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening.5,6 Several reasons underlie this inertia:

- Many practices currently use HPV tests that are not FDA approved for primary HPV testing.

- Until recently, national screening guidelines did not recommend primary HPV testing as the preferred testing strategy.

- Long-established guidance on the importance of regular cervical cytology screening promoted by the ACS and others (which especially impacts women with a cervix older than age 50 who guide their younger daughters) will rely on significant re-education to move away from the established “Pap smear” cultural icon to a new approach.

- Last but not least, companies that manufacture HPV tests and laboratories integrated to offer such tests not yet approved for primary screening are promoting reliance on the prior proven cotest strategy. They have lobbied to preserve cotesting as a primary test, with some laboratory database studies showing gaps in detection with HPV test screening alone.7-9

Currently, the FDA-approved HPV tests for primary HPV screening include the Cobas HPV test (Roche) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Both are DNA tests for 14 high-risk types of HPV that include genotyping for HPV 16 and 18.

Continue to: Follow the evidence...

Follow the evidence

Several trials in Europe and Canada provide supporting evidence for primary HPV testing, and many European countries have moved to primary HPV testing as their preferred screening method.10,11 The new ACS guidelines put us more in sync with the rest of the world, where HPV testing is the dominant strategy.

It is true that doing additional tests will find more disease; cotesting has been shown to very minimally increase detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3 (CIN 2/3) compared with HPV testing alone, but it incurs many more costs and procedures.12 The vast majority of cervical cancer is HPV positive, and cytology still can be used as a triage to primary HPV screening until tests with better sensitivity and/or specificity (such as dual stain and methylation) can be employed to reduce unnecessary “false-positive” driven procedures.

As mentioned, many strong forces are trying to keep cotesting as the preferred strategy. It is important for clinicians to recognize the corporate investment into screening platforms, relationships, and products that underlie some of these efforts so as not to be unfairly influenced by their lobbying. Data from well-conducted, high-quality studies should be the evidence on which one bases a cervical cancer screening strategy.

Innovation catalyzes change

We acknowledge that it is difficult to give up something you have been doing for decades, so there is natural resistance by both patients and clinicians to move the Pap smear into a secondary role. But the data support primary HPV testing as the best screening option from a public health perspective.

At some point, hopefully soon, primary HPV testing will receive approval for self-sampling; this has the potential to reach patients in rural or remote locations who may otherwise not get screened for cervical cancer.13

The 2019 risk-based management guidelines from the ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) also incorporate the use of HPV-based screening and surveillance after abnormal tests or colposcopy. Therefore, switching to primary HPV screening will not impact your ability to follow patients appropriately based on clinical guidelines.

Our advice to clinicians is to switch to primary HPV screening now if possible. If that is not feasible, continue your current strategy until you can make the change. And, of course, we recommend that you implement an HPV vaccination program in your practice to maximize primary prevention of HPV-related cancers. ●

How should I be approaching cervical cancer screening: with primary human papillomavirus (HPV) testing, or cotesting? We get this question all the time from clinicians. Although they have heard of the latest cervical cancer screening guidelines for stand-alone “primary” HPV testing, they are still ordering cervical cytology (Papanicolaou, or Pap, test) for women aged 21 to 29 years and cotesting (cervical cytology with HPV testing) for women with a cervix aged 30 and older.

Changes in cervical cancer testing guidance

Cervical cancer occurs in more than 13,000 women in the United States annually.1 High-risk types of HPV—the known cause of cervical cancer—also cause a large majority of cancers of the anus, vagina, vulva, and oropharynx.2

Cervical cancer screening programs in the United States have markedly decreased the incidence of and mortality from cervical cancer since introduction of the Pap smear in the 1950s. In 2000, HPV testing was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a reflex test to a Pap smear result of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASC-US). HPV testing was then approved for use with cytology as a cotest in 2003 and subsequently as a primary stand-alone test in 2014.

Recently, the American Cancer Society (ACS) released new cervical screening guidelines that depart from prior guidelines.3 They recommend not to screen 21- to 24-year-olds and to start screening at age 25 until age 65 with the preferred strategy of primary HPV testing every 5 years, using an FDA-approved HPV test. Alternative screening strategies are cytology (Pap) every 3 years or cotesting every 5 years.

The 2018 US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) guidelines differ from the ACS guidelines. The USPSTF recommends cytology every 3 years as the preferred method for women with a cervix who are aged 21 to 29 years and, for women with a cervix who are aged 30 to 65 years, the option for cytology every 3 years, primary HPV testing every 5 years, or cotesting every 5 years (TABLE).4

Why the reluctance to switch to HPV testing?

Despite FDA approval in 2014 for primary HPV testing and concurrent professional society guidance to use this testing strategy in women with a cervix who are aged 25 years and older, few practices in the United States have switched over to primary HPV testing for cervical cancer screening.5,6 Several reasons underlie this inertia:

- Many practices currently use HPV tests that are not FDA approved for primary HPV testing.

- Until recently, national screening guidelines did not recommend primary HPV testing as the preferred testing strategy.

- Long-established guidance on the importance of regular cervical cytology screening promoted by the ACS and others (which especially impacts women with a cervix older than age 50 who guide their younger daughters) will rely on significant re-education to move away from the established “Pap smear” cultural icon to a new approach.

- Last but not least, companies that manufacture HPV tests and laboratories integrated to offer such tests not yet approved for primary screening are promoting reliance on the prior proven cotest strategy. They have lobbied to preserve cotesting as a primary test, with some laboratory database studies showing gaps in detection with HPV test screening alone.7-9

Currently, the FDA-approved HPV tests for primary HPV screening include the Cobas HPV test (Roche) and the BD Onclarity HPV assay (Becton, Dickinson and Company). Both are DNA tests for 14 high-risk types of HPV that include genotyping for HPV 16 and 18.

Continue to: Follow the evidence...

Follow the evidence

Several trials in Europe and Canada provide supporting evidence for primary HPV testing, and many European countries have moved to primary HPV testing as their preferred screening method.10,11 The new ACS guidelines put us more in sync with the rest of the world, where HPV testing is the dominant strategy.

It is true that doing additional tests will find more disease; cotesting has been shown to very minimally increase detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2/3 (CIN 2/3) compared with HPV testing alone, but it incurs many more costs and procedures.12 The vast majority of cervical cancer is HPV positive, and cytology still can be used as a triage to primary HPV screening until tests with better sensitivity and/or specificity (such as dual stain and methylation) can be employed to reduce unnecessary “false-positive” driven procedures.

As mentioned, many strong forces are trying to keep cotesting as the preferred strategy. It is important for clinicians to recognize the corporate investment into screening platforms, relationships, and products that underlie some of these efforts so as not to be unfairly influenced by their lobbying. Data from well-conducted, high-quality studies should be the evidence on which one bases a cervical cancer screening strategy.

Innovation catalyzes change

We acknowledge that it is difficult to give up something you have been doing for decades, so there is natural resistance by both patients and clinicians to move the Pap smear into a secondary role. But the data support primary HPV testing as the best screening option from a public health perspective.

At some point, hopefully soon, primary HPV testing will receive approval for self-sampling; this has the potential to reach patients in rural or remote locations who may otherwise not get screened for cervical cancer.13

The 2019 risk-based management guidelines from the ASCCP (American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology) also incorporate the use of HPV-based screening and surveillance after abnormal tests or colposcopy. Therefore, switching to primary HPV screening will not impact your ability to follow patients appropriately based on clinical guidelines.

Our advice to clinicians is to switch to primary HPV screening now if possible. If that is not feasible, continue your current strategy until you can make the change. And, of course, we recommend that you implement an HPV vaccination program in your practice to maximize primary prevention of HPV-related cancers. ●

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers–United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:661-666.

- Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, KristAH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337.

- Cooper CP, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer screening intervals preferred by US women. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:389-394.

- Austin RM, Onisko A, Zhao C. Enhanced detection of cervical cancer and precancer through use of imaged liquid-based cytology in routine cytology and HPV cotesting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150:385-392.

- Kaufman HW, Alagia DP, Chen Z, et al. Contributions of liquid-based (Papanicolaou) cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cotesting for detection of cervical cancer and precancer in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:510-516.

- Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, et al. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:282-288.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Kim JJ, Burger EA, Regan C, et al. Screening for cervical cancer in primary care: a decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:706-714.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al; on behalf of the Collaboration on Self-Sampling and HPV Testing. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7-30.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers–United States, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:661-666.

- Fontham ET, Wolf AM, Church TR, et al. Cervical cancer screening for individuals at average risk: 2020 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:321-346.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Curry SJ, KristAH, Owens DK, et al. Screening for cervical cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. JAMA. 2018;320:674-686.

- Huh WK, Ault KA, Chelmow D, et al. Use of primary high-risk human papillomavirus testing for cervical cancer screening: interim clinical guidance. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125:330-337.

- Cooper CP, Saraiya M. Cervical cancer screening intervals preferred by US women. Am J Prev Med. 2018;55:389-394.

- Austin RM, Onisko A, Zhao C. Enhanced detection of cervical cancer and precancer through use of imaged liquid-based cytology in routine cytology and HPV cotesting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2018;150:385-392.

- Kaufman HW, Alagia DP, Chen Z, et al. Contributions of liquid-based (Papanicolaou) cytology and human papillomavirus testing in cotesting for detection of cervical cancer and precancer in the United States. Am J Clin Pathol. 2020;154:510-516.

- Blatt AJ, Kennedy R, Luff RD, et al. Comparison of cervical cancer screening results among 256,648 women in multiple clinical practices. Cancer Cytopathol. 2015;123:282-288.

- Ronco G, Dillner J, Elfstrom KM, et al; International HPV Screening Working Group. Efficacy of HPV-based screening for prevention of invasive cervical cancer: follow-up of four European randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2014;383:524-532.

- Ogilvie GS, van Niekerk D, Krajden M, et al. Effect of screening with primary cervical HPV testing vs cytology testing on high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia at 48 months: the HPV FOCAL randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;320:43-52.

- Kim JJ, Burger EA, Regan C, et al. Screening for cervical cancer in primary care: a decision analysis for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320:706-714.

- Arbyn M, Smith SB, Temin S, et al; on behalf of the Collaboration on Self-Sampling and HPV Testing. Detecting cervical precancer and reaching underscreened women by using HPV testing on self samples: updated meta-analyses. BMJ. 2018;363:k4823.