User login

What is the role of dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin?

In patients at risk of myocardial infarction or stroke, two antiplatelet drugs are not always better than one. In a large recent trial,1,2 adding clopidogrel (Plavix) to aspirin therapy did not offer much benefit to a cohort of patients at risk of cardiovascular events, although a subgroup did appear to benefit: those at even higher risk because they already had a history of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or peripheral arterial disease.

These were the principal findings in the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study,1,2 in which one of us (D.L.B.) was principal investigator.

These findings further our understanding of who should receive dual antiplatelet therapy, and who would be better served with aspirin therapy alone. In this article, we discuss important studies that led up to the CHARISMA trial, review CHARISMA’s purpose and study design, and interpret its results.

PREVENTING ATHEROTHROMBOSIS BY BLOCKING PLATELETS

Platelets are key players in the atherothrom-botic process.3–5 The Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration,6 in a meta-analysis of trials performed up to 1997, calculated that antiplatelet therapy (mostly with aspirin) reduced the vascular mortality rate by 15% in patients with acute or previous vascular disease or some other predisposing condition. Thus, aspirin has already been shown to be effective as primary prevention (ie, in patients at risk but without established vascular disease) and as secondary prevention (ie, in those with established disease).7,8

Yet many patients have significant vascular events in spite of taking aspirin.6 Aspirin failure is thought to be multifactorial, with causes that include weak platelet inhibition, noncompliance, discontinuation due to adverse effects (including severe bleeding), and drug interactions. In addition, aspirin resistance has been linked to worse prognosis and may prove to be another cause of aspirin failure.9–11

Clopidogrel, an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist, has also been studied extensively as an antiplatelet agent.5,12 Several studies have indicated that clopidogrel and ticlopidine (Ticlid, a related drug) may be more potent than aspirin, both in the test tube and in real patients.13–15

KEY TRIALS LEADING TO CHARISMA

- Clopidogrel is more effective and slightly safer than aspirin as secondary prevention, as shown in the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial.16–21

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is more beneficial than placebo plus aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes, as shown in the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,22–24 the Clopidogrel as Adjunctive Reperfusion Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myo-car-dial Infarction (CLARITY-TIMI 28) trial,25 and the Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial (COMMIT).26

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions, with or without drug-eluting stent placement,27–30 as shown in the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial,28 the Effect of Clopidogrel Pretreatment Before Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Fibrinolytics (PCI-CLARITY) study,29 and the Effects of Pre-treatment With Clopidogrel and Aspirin Followed by Long-term Therapy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI-CURE) study.30 In fact, most patients undergoing percutaneous interventions now receive a loading dose of clopidogrel before the procedure and continue to take it for up to 1 year afterward. However, the ideal long-term duration of clopidogrel treatment is still under debate.

In view of these previous studies, we wanted to test dual antiplatelet therapy in a broader population at high risk of atherothrombosis, ie, in patients with either established vascular disease or with multiple risk factors for it.

CHARISMA STUDY DESIGN

CHARISMA was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events.

A total of 15,603 patients, all older than 45 years, were randomly assigned to receive clopidogrel 75 mg/day plus aspirin 75 to 162 mg/day or placebo plus aspirin, in addition to standard therapy as directed by individual clinicians (eg, statins, beta-blockers). Patients were followed up at 1, 3, and 6 months and every 6 months thereafter until study completion, which occurred after 1,040 primary efficacy end points. The median duration of follow-up was 28 months.1

Patients had to have one of the following to be included: multiple atherothrombotic risk factors, documented coronary disease, documented cerebrovascular disease, or documented peripheral arterial disease (Table 2). Specific exclusion criteria included the use of oral antithrombotic or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.1

End points

The primary end point was the combined incidence of the first episode of myocardial infarction or stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes.

The secondary end point was the combined incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, death from cardiovascular causes, or hospitalization for unstable angina, a transient ischemic attack, or revascularization procedure.

The primary safety end point was severe bleeding, as defined in the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) study31 as intracranial hemorrhage, fatal bleeding, or bleeding leading to hemody-namic compromise. Moderate bleeding was defined as bleeding that required transfusion but did not meet the GUSTO definition of severe bleeding.

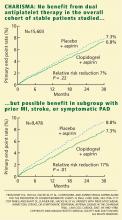

OVERALL, NO BENEFIT

The rates of the secondary end point were 16.7% vs 17.9% (absolute risk reduction 1.2%; relative risk reduction 8%; P = .04).

Possible benefit in symptomatic patients

In a prespecified analysis, patients were classified as being “symptomatic” (having documented cardiovascular disease, ie, coronary, cerebrovascular, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease) or “asymptomatic” (having multiple risk factors without established cardiovascular disease).1

In the symptomatic group (n = 12,153), the primary end point was reached in 6.9% of patients treated with clopidogrel vs 7.9% with placebo (absolute risk reduction 1.0%; relative risk reduction 13%; P = .046). The 3,284 asymptomatic patients showed no benefit; the rate of the primary end point for the clopido-grel group was 6.6% vs 5.5% in the placebo group (P = .20).

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the data from 9,478 patients who were similar to those in the CAPRIE study (ie, with documented prior myocardial infarction, prior ischemic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease). The rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 8.8% in the placebo-plus-aspirin group and 7.3% in the clopidogrel-plus-aspirin group (absolute risk reduction 1.5%; relative risk reduction 17%; P = .01; Figure 1).2

HOW SHOULD WE INTERPRET THESE FINDINGS?

CHARISMA was the first trial to evaluate whether adding clopidogrel to aspirin therapy would reduce the rates of vascular events and death from cardiovascular causes in stable patients at risk of ischemic events. As in other trials, the benefit of clopidogrel-plus-aspirin therapy was weighed against the risk of bleeding with this regimen. How are we to interpret the findings?

- In the group with multiple risk factors but without clearly documented cardiovascular disease, there was no benefit—and there was an increase in moderate bleeding. Given these findings, physicians should not prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for primary prevention in patients without known vascular disease.

- A potential benefit was seen in a prespecified subgroup who had documented cardiovascular disease. Given the limitations of subgroup analysis, however, and given the increased risk of moderate bleeding, this positive result should be interpreted with some degree of caution.

- CHARISMA suggests that there may be benefit of protracted dual antiplatelet therapy in stable patients with documented prior ischemic events.

A possible reason for the observed lack of benefit in the overall cohort but the positive results in the subgroups with established vascular disease is that plaque rupture and thrombosis may be a precondition for dual antiplatelet therapy to work.

Another possibility is that, although we have been saying that diabetes mellitus (one of the possible entry criteria in CHARISMA) is a “coronary risk equivalent,” this may not be absolutely true. Although it had been demonstrated that patients with certain risk factors, such as diabetes, have an incidence of ischemic events similar to that in patients with prior MI and should be considered for antiplatelet therapy to prevent vascular events,32 more recent data have shown that patients with prior ischemic events are at much higher risk than patients without ischemic events, even if the latter have diabetes.33,34

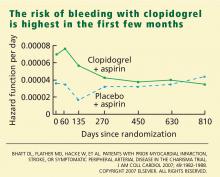

- The observation in CHARISMA that the incremental bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin does not persist beyond a year in patients who have tolerated therapy for a year without a bleeding event may affect the decision to continue clopidogrel beyond 1 year, such as in patients with acute coronary syndromes or patients who have received drug-eluting stents.35,36

- Another important consideration is cost-effectiveness. Several studies have analyzed the impact of cost and found clopidogrel to be cost-effective by preventing ischemic events and adding years of life.37,38 A recent analysis from CHARISMA also shows cost-effectiveness in the subgroup of patients enrolled with established cardiovascular disease.39 Once clopidogrel becomes generic, the cost-effectiveness will become even better.

Further studies should better define which stable patients with cardiovascular disease should be on more than aspirin alone.

- Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1706–1717.

- Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1982–1988.

- Ruggeri ZM. Platelets in atherothrombosis. Nat Med 2002; 8:1227–1234.

- Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ. Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:937–954.

- Meadows TA, Bhatt DL. Clinical aspects of platelet inhibitors and thrombus formation. Circ Res 2007; 100:1261–1275.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324:71–86.

- Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001; 85:265–271.

- Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:161–172.

- Helgason CM, Bolin KM, Hoff JA, et al. Development of aspirin resistance in persons with previous ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25:2331–2336.

- Helgason CM, Tortorice KL, Winkler SR, et al. Aspirin response and failure in cerebral infarction. Stroke 1993; 24:345–350.

- Gum PA, Kottke-Marchant K, Poggio ED, et al. Profile and prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:230–235.

- Coukell AJ, Markham A. Clopidogrel. Drugs 1997; 54:745–750.

- Humbert M, Nurden P, Bihour C, et al. Ultrastructural studies of platelet aggregates from human subjects receiving clopidogrel and from a patient with an inherited defect of an ADP-dependent pathway of platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996; 16:1532–1543.

- Hass WK, Easton JD, Adams HP, et al. A randomized trial comparing ticlopidine hydrochloride with aspirin for the prevention of stroke in high-risk patients. Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:501–507.

- Savi P, Bernat A, Dumas A, Ait-Chek L, Herbert JM. Effect of aspirin and clopidogrel on platelet-dependent tissue factor expression in endothelial cells. Thromb Res 1994; 73:117–124.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopido-grel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348:1329–1339.

- Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Amplified benefit of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90:625–628.

- Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Reduction in the need for hospitalization for recurrent ischemic events and bleeding with clopidogrel instead of aspirin. CAPRIE investigators. Am Heart J 2000; 140:67–73.

- Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in the secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease. Med Clin North Am 2000; 84 1:163–179.

- Ringleb PA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Topol EJ, Hacke W Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events Investigators. Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke 2004; 35:528–532.

- Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Superiority of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation 2001; 103:363–368.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494–502.

- Budaj A, Yusuf S, Mehta SR, et al. Benefit of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation in various risk groups. Circulation 2002; 106:1622–1626.

- Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events (CURE) Trial. Circulation 2004; 110:1202–1208.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1179–1189.

- Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366:1607–1621.

- Bhatt DL, Kapadia SR, Bajzer CT, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin after carotid artery stenting. J Invasive Cardiol 2001; 13:767–771.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:2411–2420.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Effect of clopidogrel pre-treatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytics: the PCI-CLARITY study. JAMA 2005; 294:1224–1232.

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001; 358:527–533.

- The GUSTO Investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:673–682.

- Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:229–234.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006; 295:180–189.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007; 297:1197–1206.

- Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Helton TJ, Borek PP, Mood GR, Bhatt DL. Late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Med 2006; 119:1056–1061.

- Rabbat MG, Bavry AA, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG. Understanding and minimizing late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:129–136.

- Gaspoz JM, Coxson PG, Goldman PA, et al. Cost effectiveness of aspirin, clopidogrel, or both for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1800–1806.

- Beinart SC, Kolm P, Veledar E, et al. Longterm cost effectiveness of early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel given for up to one year after percutaneous coronary intervention results: from the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:761–769.

- Chen J, Bhatt DL, Schneider E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel + aspirin vs. aspirin alone for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the CHARISMA Trial Session; APS.96.1; Presentation 3855; American Heart Association Scientific Sessions; Nov 12–15, 2006; Chicago IL.

In patients at risk of myocardial infarction or stroke, two antiplatelet drugs are not always better than one. In a large recent trial,1,2 adding clopidogrel (Plavix) to aspirin therapy did not offer much benefit to a cohort of patients at risk of cardiovascular events, although a subgroup did appear to benefit: those at even higher risk because they already had a history of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or peripheral arterial disease.

These were the principal findings in the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study,1,2 in which one of us (D.L.B.) was principal investigator.

These findings further our understanding of who should receive dual antiplatelet therapy, and who would be better served with aspirin therapy alone. In this article, we discuss important studies that led up to the CHARISMA trial, review CHARISMA’s purpose and study design, and interpret its results.

PREVENTING ATHEROTHROMBOSIS BY BLOCKING PLATELETS

Platelets are key players in the atherothrom-botic process.3–5 The Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration,6 in a meta-analysis of trials performed up to 1997, calculated that antiplatelet therapy (mostly with aspirin) reduced the vascular mortality rate by 15% in patients with acute or previous vascular disease or some other predisposing condition. Thus, aspirin has already been shown to be effective as primary prevention (ie, in patients at risk but without established vascular disease) and as secondary prevention (ie, in those with established disease).7,8

Yet many patients have significant vascular events in spite of taking aspirin.6 Aspirin failure is thought to be multifactorial, with causes that include weak platelet inhibition, noncompliance, discontinuation due to adverse effects (including severe bleeding), and drug interactions. In addition, aspirin resistance has been linked to worse prognosis and may prove to be another cause of aspirin failure.9–11

Clopidogrel, an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist, has also been studied extensively as an antiplatelet agent.5,12 Several studies have indicated that clopidogrel and ticlopidine (Ticlid, a related drug) may be more potent than aspirin, both in the test tube and in real patients.13–15

KEY TRIALS LEADING TO CHARISMA

- Clopidogrel is more effective and slightly safer than aspirin as secondary prevention, as shown in the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial.16–21

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is more beneficial than placebo plus aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes, as shown in the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,22–24 the Clopidogrel as Adjunctive Reperfusion Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myo-car-dial Infarction (CLARITY-TIMI 28) trial,25 and the Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial (COMMIT).26

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions, with or without drug-eluting stent placement,27–30 as shown in the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial,28 the Effect of Clopidogrel Pretreatment Before Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Fibrinolytics (PCI-CLARITY) study,29 and the Effects of Pre-treatment With Clopidogrel and Aspirin Followed by Long-term Therapy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI-CURE) study.30 In fact, most patients undergoing percutaneous interventions now receive a loading dose of clopidogrel before the procedure and continue to take it for up to 1 year afterward. However, the ideal long-term duration of clopidogrel treatment is still under debate.

In view of these previous studies, we wanted to test dual antiplatelet therapy in a broader population at high risk of atherothrombosis, ie, in patients with either established vascular disease or with multiple risk factors for it.

CHARISMA STUDY DESIGN

CHARISMA was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events.

A total of 15,603 patients, all older than 45 years, were randomly assigned to receive clopidogrel 75 mg/day plus aspirin 75 to 162 mg/day or placebo plus aspirin, in addition to standard therapy as directed by individual clinicians (eg, statins, beta-blockers). Patients were followed up at 1, 3, and 6 months and every 6 months thereafter until study completion, which occurred after 1,040 primary efficacy end points. The median duration of follow-up was 28 months.1

Patients had to have one of the following to be included: multiple atherothrombotic risk factors, documented coronary disease, documented cerebrovascular disease, or documented peripheral arterial disease (Table 2). Specific exclusion criteria included the use of oral antithrombotic or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.1

End points

The primary end point was the combined incidence of the first episode of myocardial infarction or stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes.

The secondary end point was the combined incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, death from cardiovascular causes, or hospitalization for unstable angina, a transient ischemic attack, or revascularization procedure.

The primary safety end point was severe bleeding, as defined in the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) study31 as intracranial hemorrhage, fatal bleeding, or bleeding leading to hemody-namic compromise. Moderate bleeding was defined as bleeding that required transfusion but did not meet the GUSTO definition of severe bleeding.

OVERALL, NO BENEFIT

The rates of the secondary end point were 16.7% vs 17.9% (absolute risk reduction 1.2%; relative risk reduction 8%; P = .04).

Possible benefit in symptomatic patients

In a prespecified analysis, patients were classified as being “symptomatic” (having documented cardiovascular disease, ie, coronary, cerebrovascular, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease) or “asymptomatic” (having multiple risk factors without established cardiovascular disease).1

In the symptomatic group (n = 12,153), the primary end point was reached in 6.9% of patients treated with clopidogrel vs 7.9% with placebo (absolute risk reduction 1.0%; relative risk reduction 13%; P = .046). The 3,284 asymptomatic patients showed no benefit; the rate of the primary end point for the clopido-grel group was 6.6% vs 5.5% in the placebo group (P = .20).

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the data from 9,478 patients who were similar to those in the CAPRIE study (ie, with documented prior myocardial infarction, prior ischemic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease). The rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 8.8% in the placebo-plus-aspirin group and 7.3% in the clopidogrel-plus-aspirin group (absolute risk reduction 1.5%; relative risk reduction 17%; P = .01; Figure 1).2

HOW SHOULD WE INTERPRET THESE FINDINGS?

CHARISMA was the first trial to evaluate whether adding clopidogrel to aspirin therapy would reduce the rates of vascular events and death from cardiovascular causes in stable patients at risk of ischemic events. As in other trials, the benefit of clopidogrel-plus-aspirin therapy was weighed against the risk of bleeding with this regimen. How are we to interpret the findings?

- In the group with multiple risk factors but without clearly documented cardiovascular disease, there was no benefit—and there was an increase in moderate bleeding. Given these findings, physicians should not prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for primary prevention in patients without known vascular disease.

- A potential benefit was seen in a prespecified subgroup who had documented cardiovascular disease. Given the limitations of subgroup analysis, however, and given the increased risk of moderate bleeding, this positive result should be interpreted with some degree of caution.

- CHARISMA suggests that there may be benefit of protracted dual antiplatelet therapy in stable patients with documented prior ischemic events.

A possible reason for the observed lack of benefit in the overall cohort but the positive results in the subgroups with established vascular disease is that plaque rupture and thrombosis may be a precondition for dual antiplatelet therapy to work.

Another possibility is that, although we have been saying that diabetes mellitus (one of the possible entry criteria in CHARISMA) is a “coronary risk equivalent,” this may not be absolutely true. Although it had been demonstrated that patients with certain risk factors, such as diabetes, have an incidence of ischemic events similar to that in patients with prior MI and should be considered for antiplatelet therapy to prevent vascular events,32 more recent data have shown that patients with prior ischemic events are at much higher risk than patients without ischemic events, even if the latter have diabetes.33,34

- The observation in CHARISMA that the incremental bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin does not persist beyond a year in patients who have tolerated therapy for a year without a bleeding event may affect the decision to continue clopidogrel beyond 1 year, such as in patients with acute coronary syndromes or patients who have received drug-eluting stents.35,36

- Another important consideration is cost-effectiveness. Several studies have analyzed the impact of cost and found clopidogrel to be cost-effective by preventing ischemic events and adding years of life.37,38 A recent analysis from CHARISMA also shows cost-effectiveness in the subgroup of patients enrolled with established cardiovascular disease.39 Once clopidogrel becomes generic, the cost-effectiveness will become even better.

Further studies should better define which stable patients with cardiovascular disease should be on more than aspirin alone.

In patients at risk of myocardial infarction or stroke, two antiplatelet drugs are not always better than one. In a large recent trial,1,2 adding clopidogrel (Plavix) to aspirin therapy did not offer much benefit to a cohort of patients at risk of cardiovascular events, although a subgroup did appear to benefit: those at even higher risk because they already had a history of myocardial infarction, ischemic stroke, or peripheral arterial disease.

These were the principal findings in the Clopidogrel for High Atherothrombotic Risk and Ischemic Stabilization, Management, and Avoidance (CHARISMA) study,1,2 in which one of us (D.L.B.) was principal investigator.

These findings further our understanding of who should receive dual antiplatelet therapy, and who would be better served with aspirin therapy alone. In this article, we discuss important studies that led up to the CHARISMA trial, review CHARISMA’s purpose and study design, and interpret its results.

PREVENTING ATHEROTHROMBOSIS BY BLOCKING PLATELETS

Platelets are key players in the atherothrom-botic process.3–5 The Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration,6 in a meta-analysis of trials performed up to 1997, calculated that antiplatelet therapy (mostly with aspirin) reduced the vascular mortality rate by 15% in patients with acute or previous vascular disease or some other predisposing condition. Thus, aspirin has already been shown to be effective as primary prevention (ie, in patients at risk but without established vascular disease) and as secondary prevention (ie, in those with established disease).7,8

Yet many patients have significant vascular events in spite of taking aspirin.6 Aspirin failure is thought to be multifactorial, with causes that include weak platelet inhibition, noncompliance, discontinuation due to adverse effects (including severe bleeding), and drug interactions. In addition, aspirin resistance has been linked to worse prognosis and may prove to be another cause of aspirin failure.9–11

Clopidogrel, an adenosine diphosphate (ADP) receptor antagonist, has also been studied extensively as an antiplatelet agent.5,12 Several studies have indicated that clopidogrel and ticlopidine (Ticlid, a related drug) may be more potent than aspirin, both in the test tube and in real patients.13–15

KEY TRIALS LEADING TO CHARISMA

- Clopidogrel is more effective and slightly safer than aspirin as secondary prevention, as shown in the Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events (CAPRIE) trial.16–21

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is more beneficial than placebo plus aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes, as shown in the Clopidogrel in Unstable Angina to Prevent Recurrent Ischemic Events (CURE) trial,22–24 the Clopidogrel as Adjunctive Reperfusion Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myo-car-dial Infarction (CLARITY-TIMI 28) trial,25 and the Clopidogrel and Metoprolol in Myocardial Infarction Trial (COMMIT).26

- The combination of clopidogrel plus aspirin is beneficial in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions, with or without drug-eluting stent placement,27–30 as shown in the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial,28 the Effect of Clopidogrel Pretreatment Before Percutaneous Coronary Intervention in Patients With ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction With Fibrinolytics (PCI-CLARITY) study,29 and the Effects of Pre-treatment With Clopidogrel and Aspirin Followed by Long-term Therapy in Patients Undergoing Percutaneous Coronary Intervention (PCI-CURE) study.30 In fact, most patients undergoing percutaneous interventions now receive a loading dose of clopidogrel before the procedure and continue to take it for up to 1 year afterward. However, the ideal long-term duration of clopidogrel treatment is still under debate.

In view of these previous studies, we wanted to test dual antiplatelet therapy in a broader population at high risk of atherothrombosis, ie, in patients with either established vascular disease or with multiple risk factors for it.

CHARISMA STUDY DESIGN

CHARISMA was a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of clopidogrel plus aspirin vs placebo plus aspirin in patients at high risk of cardiovascular events.

A total of 15,603 patients, all older than 45 years, were randomly assigned to receive clopidogrel 75 mg/day plus aspirin 75 to 162 mg/day or placebo plus aspirin, in addition to standard therapy as directed by individual clinicians (eg, statins, beta-blockers). Patients were followed up at 1, 3, and 6 months and every 6 months thereafter until study completion, which occurred after 1,040 primary efficacy end points. The median duration of follow-up was 28 months.1

Patients had to have one of the following to be included: multiple atherothrombotic risk factors, documented coronary disease, documented cerebrovascular disease, or documented peripheral arterial disease (Table 2). Specific exclusion criteria included the use of oral antithrombotic or chronic nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications.1

End points

The primary end point was the combined incidence of the first episode of myocardial infarction or stroke, or death from cardiovascular causes.

The secondary end point was the combined incidence of myocardial infarction, stroke, death from cardiovascular causes, or hospitalization for unstable angina, a transient ischemic attack, or revascularization procedure.

The primary safety end point was severe bleeding, as defined in the Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries (GUSTO) study31 as intracranial hemorrhage, fatal bleeding, or bleeding leading to hemody-namic compromise. Moderate bleeding was defined as bleeding that required transfusion but did not meet the GUSTO definition of severe bleeding.

OVERALL, NO BENEFIT

The rates of the secondary end point were 16.7% vs 17.9% (absolute risk reduction 1.2%; relative risk reduction 8%; P = .04).

Possible benefit in symptomatic patients

In a prespecified analysis, patients were classified as being “symptomatic” (having documented cardiovascular disease, ie, coronary, cerebrovascular, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease) or “asymptomatic” (having multiple risk factors without established cardiovascular disease).1

In the symptomatic group (n = 12,153), the primary end point was reached in 6.9% of patients treated with clopidogrel vs 7.9% with placebo (absolute risk reduction 1.0%; relative risk reduction 13%; P = .046). The 3,284 asymptomatic patients showed no benefit; the rate of the primary end point for the clopido-grel group was 6.6% vs 5.5% in the placebo group (P = .20).

In a post hoc analysis, we examined the data from 9,478 patients who were similar to those in the CAPRIE study (ie, with documented prior myocardial infarction, prior ischemic stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease). The rate of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, or stroke was 8.8% in the placebo-plus-aspirin group and 7.3% in the clopidogrel-plus-aspirin group (absolute risk reduction 1.5%; relative risk reduction 17%; P = .01; Figure 1).2

HOW SHOULD WE INTERPRET THESE FINDINGS?

CHARISMA was the first trial to evaluate whether adding clopidogrel to aspirin therapy would reduce the rates of vascular events and death from cardiovascular causes in stable patients at risk of ischemic events. As in other trials, the benefit of clopidogrel-plus-aspirin therapy was weighed against the risk of bleeding with this regimen. How are we to interpret the findings?

- In the group with multiple risk factors but without clearly documented cardiovascular disease, there was no benefit—and there was an increase in moderate bleeding. Given these findings, physicians should not prescribe dual antiplatelet therapy for primary prevention in patients without known vascular disease.

- A potential benefit was seen in a prespecified subgroup who had documented cardiovascular disease. Given the limitations of subgroup analysis, however, and given the increased risk of moderate bleeding, this positive result should be interpreted with some degree of caution.

- CHARISMA suggests that there may be benefit of protracted dual antiplatelet therapy in stable patients with documented prior ischemic events.

A possible reason for the observed lack of benefit in the overall cohort but the positive results in the subgroups with established vascular disease is that plaque rupture and thrombosis may be a precondition for dual antiplatelet therapy to work.

Another possibility is that, although we have been saying that diabetes mellitus (one of the possible entry criteria in CHARISMA) is a “coronary risk equivalent,” this may not be absolutely true. Although it had been demonstrated that patients with certain risk factors, such as diabetes, have an incidence of ischemic events similar to that in patients with prior MI and should be considered for antiplatelet therapy to prevent vascular events,32 more recent data have shown that patients with prior ischemic events are at much higher risk than patients without ischemic events, even if the latter have diabetes.33,34

- The observation in CHARISMA that the incremental bleeding risk of dual antiplatelet therapy vs aspirin does not persist beyond a year in patients who have tolerated therapy for a year without a bleeding event may affect the decision to continue clopidogrel beyond 1 year, such as in patients with acute coronary syndromes or patients who have received drug-eluting stents.35,36

- Another important consideration is cost-effectiveness. Several studies have analyzed the impact of cost and found clopidogrel to be cost-effective by preventing ischemic events and adding years of life.37,38 A recent analysis from CHARISMA also shows cost-effectiveness in the subgroup of patients enrolled with established cardiovascular disease.39 Once clopidogrel becomes generic, the cost-effectiveness will become even better.

Further studies should better define which stable patients with cardiovascular disease should be on more than aspirin alone.

- Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1706–1717.

- Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1982–1988.

- Ruggeri ZM. Platelets in atherothrombosis. Nat Med 2002; 8:1227–1234.

- Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ. Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:937–954.

- Meadows TA, Bhatt DL. Clinical aspects of platelet inhibitors and thrombus formation. Circ Res 2007; 100:1261–1275.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324:71–86.

- Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001; 85:265–271.

- Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:161–172.

- Helgason CM, Bolin KM, Hoff JA, et al. Development of aspirin resistance in persons with previous ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25:2331–2336.

- Helgason CM, Tortorice KL, Winkler SR, et al. Aspirin response and failure in cerebral infarction. Stroke 1993; 24:345–350.

- Gum PA, Kottke-Marchant K, Poggio ED, et al. Profile and prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:230–235.

- Coukell AJ, Markham A. Clopidogrel. Drugs 1997; 54:745–750.

- Humbert M, Nurden P, Bihour C, et al. Ultrastructural studies of platelet aggregates from human subjects receiving clopidogrel and from a patient with an inherited defect of an ADP-dependent pathway of platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996; 16:1532–1543.

- Hass WK, Easton JD, Adams HP, et al. A randomized trial comparing ticlopidine hydrochloride with aspirin for the prevention of stroke in high-risk patients. Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:501–507.

- Savi P, Bernat A, Dumas A, Ait-Chek L, Herbert JM. Effect of aspirin and clopidogrel on platelet-dependent tissue factor expression in endothelial cells. Thromb Res 1994; 73:117–124.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopido-grel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348:1329–1339.

- Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Amplified benefit of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90:625–628.

- Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Reduction in the need for hospitalization for recurrent ischemic events and bleeding with clopidogrel instead of aspirin. CAPRIE investigators. Am Heart J 2000; 140:67–73.

- Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in the secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease. Med Clin North Am 2000; 84 1:163–179.

- Ringleb PA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Topol EJ, Hacke W Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events Investigators. Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke 2004; 35:528–532.

- Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Superiority of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation 2001; 103:363–368.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494–502.

- Budaj A, Yusuf S, Mehta SR, et al. Benefit of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation in various risk groups. Circulation 2002; 106:1622–1626.

- Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events (CURE) Trial. Circulation 2004; 110:1202–1208.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1179–1189.

- Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366:1607–1621.

- Bhatt DL, Kapadia SR, Bajzer CT, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin after carotid artery stenting. J Invasive Cardiol 2001; 13:767–771.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:2411–2420.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Effect of clopidogrel pre-treatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytics: the PCI-CLARITY study. JAMA 2005; 294:1224–1232.

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001; 358:527–533.

- The GUSTO Investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:673–682.

- Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:229–234.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006; 295:180–189.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007; 297:1197–1206.

- Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Helton TJ, Borek PP, Mood GR, Bhatt DL. Late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Med 2006; 119:1056–1061.

- Rabbat MG, Bavry AA, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG. Understanding and minimizing late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:129–136.

- Gaspoz JM, Coxson PG, Goldman PA, et al. Cost effectiveness of aspirin, clopidogrel, or both for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1800–1806.

- Beinart SC, Kolm P, Veledar E, et al. Longterm cost effectiveness of early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel given for up to one year after percutaneous coronary intervention results: from the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:761–769.

- Chen J, Bhatt DL, Schneider E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel + aspirin vs. aspirin alone for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the CHARISMA Trial Session; APS.96.1; Presentation 3855; American Heart Association Scientific Sessions; Nov 12–15, 2006; Chicago IL.

- Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, et al. Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. N Engl J Med 2006; 354:1706–1717.

- Bhatt DL, Flather MD, Hacke W, et al. Patients with prior myocardial infarction, stroke, or symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the CHARISMA trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:1982–1988.

- Ruggeri ZM. Platelets in atherothrombosis. Nat Med 2002; 8:1227–1234.

- Fuster V, Moreno PR, Fayad ZA, Corti R, Badimon JJ. Atherothrombosis and high-risk plaque: part I: evolving concepts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:937–954.

- Meadows TA, Bhatt DL. Clinical aspects of platelet inhibitors and thrombus formation. Circ Res 2007; 100:1261–1275.

- Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ 2002; 324:71–86.

- Sanmuganathan PS, Ghahramani P, Jackson PR, Wallis EJ, Ramsay LE. Aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: safety and absolute benefit related to coronary risk derived from meta-analysis of randomised trials. Heart 2001; 85:265–271.

- Hayden M, Pignone M, Phillips C, Mulrow C. Aspirin for the primary prevention of cardiovascular events: a summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:161–172.

- Helgason CM, Bolin KM, Hoff JA, et al. Development of aspirin resistance in persons with previous ischemic stroke. Stroke 1994; 25:2331–2336.

- Helgason CM, Tortorice KL, Winkler SR, et al. Aspirin response and failure in cerebral infarction. Stroke 1993; 24:345–350.

- Gum PA, Kottke-Marchant K, Poggio ED, et al. Profile and prevalence of aspirin resistance in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2001; 88:230–235.

- Coukell AJ, Markham A. Clopidogrel. Drugs 1997; 54:745–750.

- Humbert M, Nurden P, Bihour C, et al. Ultrastructural studies of platelet aggregates from human subjects receiving clopidogrel and from a patient with an inherited defect of an ADP-dependent pathway of platelet activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1996; 16:1532–1543.

- Hass WK, Easton JD, Adams HP, et al. A randomized trial comparing ticlopidine hydrochloride with aspirin for the prevention of stroke in high-risk patients. Ticlopidine Aspirin Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:501–507.

- Savi P, Bernat A, Dumas A, Ait-Chek L, Herbert JM. Effect of aspirin and clopidogrel on platelet-dependent tissue factor expression in endothelial cells. Thromb Res 1994; 73:117–124.

- CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded, trial of clopido-grel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996; 348:1329–1339.

- Bhatt DL, Marso SP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Amplified benefit of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol 2002; 90:625–628.

- Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Reduction in the need for hospitalization for recurrent ischemic events and bleeding with clopidogrel instead of aspirin. CAPRIE investigators. Am Heart J 2000; 140:67–73.

- Bhatt DL, Topol EJ. Antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapy in the secondary prevention of ischemic heart disease. Med Clin North Am 2000; 84 1:163–179.

- Ringleb PA, Bhatt DL, Hirsch AT, Topol EJ, Hacke W Clopidogrel Versus Aspirin in Patients at Risk of Ischemic Events Investigators. Benefit of clopidogrel over aspirin is amplified in patients with a history of ischemic events. Stroke 2004; 35:528–532.

- Bhatt DL, Chew DP, Hirsch AT, Ringleb PA, Hacke W, Topol EJ. Superiority of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients with prior cardiac surgery. Circulation 2001; 103:363–368.

- Yusuf S, Zhao F, Mehta SR, et al. Effects of clopidogrel in addition to aspirin in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2001; 345:494–502.

- Budaj A, Yusuf S, Mehta SR, et al. Benefit of clopidogrel in patients with acute coronary syndromes without ST-segment elevation in various risk groups. Circulation 2002; 106:1622–1626.

- Fox KA, Mehta SR, Peters R, et al. Benefits and risks of the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin in patients undergoing surgical revascularization for non–ST-elevation acute coronary syndrome: the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent ischemic Events (CURE) Trial. Circulation 2004; 110:1202–1208.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin and fibrinolytic therapy for myocardial infarction with ST-segment elevation. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:1179–1189.

- Chen ZM, Jiang LX, Chen YP, et al. Addition of clopidogrel to aspirin in 45,852 patients with acute myocardial infarction: randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2005; 366:1607–1621.

- Bhatt DL, Kapadia SR, Bajzer CT, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel and aspirin after carotid artery stenting. J Invasive Cardiol 2001; 13:767–771.

- Steinhubl SR, Berger PB, Mann JT, et al. Early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002; 288:2411–2420.

- Sabatine MS, Cannon CP, Gibson CM, et al. Effect of clopidogrel pre-treatment before percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with fibrinolytics: the PCI-CLARITY study. JAMA 2005; 294:1224–1232.

- Mehta SR, Yusuf S, Peters RJ, et al. Effects of pretreatment with clopidogrel and aspirin followed by long-term therapy in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: the PCI-CURE study. Lancet 2001; 358:527–533.

- The GUSTO Investigators. An international randomized trial comparing four thrombolytic strategies for acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1993; 329:673–682.

- Haffner SM, Lehto S, Ronnemaa T, Pyorala K, Laakso M. Mortality from coronary heart disease in subjects with type 2 diabetes and in nondiabetic subjects with and without prior myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 1998; 339:229–234.

- Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Ohman EM, et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2006; 295:180–189.

- Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA 2007; 297:1197–1206.

- Bavry AA, Kumbhani DJ, Helton TJ, Borek PP, Mood GR, Bhatt DL. Late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Med 2006; 119:1056–1061.

- Rabbat MG, Bavry AA, Bhatt DL, Ellis SG. Understanding and minimizing late thrombosis of drug-eluting stents. Cleve Clin J Med 2007; 74:129–136.

- Gaspoz JM, Coxson PG, Goldman PA, et al. Cost effectiveness of aspirin, clopidogrel, or both for secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:1800–1806.

- Beinart SC, Kolm P, Veledar E, et al. Longterm cost effectiveness of early and sustained dual oral antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel given for up to one year after percutaneous coronary intervention results: from the Clopidogrel for the Reduction of Events During Observation (CREDO) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46:761–769.

- Chen J, Bhatt DL, Schneider E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of clopidogrel + aspirin vs. aspirin alone for secondary prevention of cardiovascular events: results from the CHARISMA Trial Session; APS.96.1; Presentation 3855; American Heart Association Scientific Sessions; Nov 12–15, 2006; Chicago IL.

KEY POINTS

- Platelets are key players in atherothrombosis, and antiplatelet drugs such as aspirin and clopidogrel prevent events in patients at risk.

- In studies leading up to CHARISMA, the combination of clopidogrel and aspirin was found to be beneficial in patients with acute coronary syndromes and in those undergoing percutaneous coronary interventions.

- Clopidogrel should not be combined with aspirin as a primary preventive therapy (ie, for people without established vascular disease). How dual antiplatelet therapy should be used as secondary prevention in stable patients needs further study.