User login

Physician wellness: Managing stress and preventing burnout

Meet Dr. A and Dr. M

Dr. A is a 50-year-old family physician who provides prenatal care in a busy practice. She sees patients in eight 4-hour clinic sessions per week and is on inpatient call 1 week out of every 2 months. Dr. A has become disillusioned with her practice. She typically works until 7

Dr. M is a single, 32-year-old family physician working at an academic medical center. Dr. M is unhappy in his job, is trying to grow his practice, and views himself as having little impact or autonomy. He finds himself lost while navigating the electronic health record (EHR) and struggles to be efficient in the clinic. Dr. M has multiple administrative responsibilities that require him to work evenings and weekends. Debt from medical school loans also motivates him to moonlight several weekends per month. Over the past few months, Dr. M has become frustrated and discouraged, making his depression more difficult to manage. He feels drained by the time he arrives home, where he lives alone. He has stopped exercising, socializing with friends, and dating. Dr. M often wonders if he is in the wrong profession.

Defining burnout, stress, and wellness

Dr. A and Dr. M are experiencing symptoms of burnout, common to physicians and other health care professionals. Recent studies showed an increase in burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 In a survey using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), approximately 44% of physicians reported at least one symptom of burnout.3 After adjusting for age, gender, relationship status, and hours worked per week, physicians were found to be at greater risk for burnout than nonphysician workers.3 The latest Medscape physician burnout survey found an increase in burnout among US physicians from 42% in 2021 to 47% in 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Rates of burnout were even higher among family physicians and other frontline (eg, emergency, infectious disease, and critical care) physicians.1

Burnout has 3 key dimensions: (1) overwhelming exhaustion; (2) feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job; and (3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4 The MBI is considered the standard tool for research in the field of burnout and has been repeatedly assessed for reliability and validity.4 The original MBI includes such items as: “I feel emotionally drained from my work,” “I feel like I’m working too hard on my job,” and “I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally.”5

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is an occupational phenomenon associated with chronic work-related stress that is not successfully managed.6 This definition emphasizes work stress as the cause of burnout, thus highlighting the importance of addressing the work environment.7 Physician burnout can affect physician health and wellness and the quality of patient care.8-13 Because of the cost of burnout to individuals and the health care system, it is important to understand stressors that can lead to physician burnout.

Stress has been described as “physical, mental, or emotional strain or tension … when a person perceives that demands exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize.”14 Work-related sources of stress affecting practicing physicians include long workdays, multiple bureaucratic tasks, lack of autonomy/control, and complex patients.1,15

The COVID-19 pandemic is a stressor that increased physicians’ exposure to patient suffering and deaths and physicians’ vulnerability to disease at work.16 Physicians taking care of patients with COVID-19 risk infection and the possibility of infecting others.Online health records are another source of stress for many physicians.17,18 Access to online health records on personal devices can blur the line between work and home. For each hour of direct patient contact, a physician spends an additional 2 hours interacting with an EHR.19 Among family physicians and other primary care physicians, increased EHR interaction outside clinic hours has been associated with decreased workplace satisfaction and increased rates of burnout.11,19,20 Time spent on non-patient-facing clinical tasks, such as peer-to-peer reviews and billing queries, contributes more to burnout than clinic time alone.17

Continue to: These and other organizational factors...

These and other organizational factors contribute to the stress experienced by physicians. Many describe themselves as feeling consumed by their work. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians (and the rest of the health care team) had to quickly learn how to conduct virtual office visits. Clerical responsibilities increased as patients relied more on patient portals and telephone calls to receive care.

Who is predisposed to burnout? Although burnout is a work-related syndrome, studies have shown an increase in burnout associated with individual (ie, personal) factors. For example, female physicians have been shown to have higher rates of burnout compared with male physicians.1,3 The stress of balancing the demands of the profession can begin during medical school and residency, with younger physicians having nearly twice the risk for stress-related symptoms when compared with older colleagues.15,20-23 Having a child younger than 21 years old, and other personal factors related to balancing family and life demands, increases the likelihood of burnout.11,21,22

Physicians with certain personality types and predispositions are at increased risk for burnout.23-25 For example, neuroticism on the Big Five Personality Inventory (one of the most well-known of the psychology inventories) is associated with an increased risk for burnout. Neuroticism may manifest as sadness or related emotional dysregulation (eg, irritability, anxiety).26 Other traits measured by the Big Five Personality Inventory include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.26

A history of depression is also associated with an increased risk for burnout.27 Although depression and burnout are separate conditions, a 2016 study found significant overlap between the two.27 Physicians in this study who were depressed were more likely to experience burnout symptoms (87.5%); however, only 26.2% of physicians experiencing burnout were diagnosed as having depression.27 Rates of depression are higher among physicians when compared with nonphysicians, yet physicians are less likely to seek help due to fear of stigma and potential licensing concerns.28,29 Because of this, when physicians experience depressive symptoms, they may respond by working harder rather than seeking professional counseling or emotional support. They might believe that “asking for help is a sign of weakness,” thus sacrificing their wellness.

Wellness encompasses a sense of thriving characterized by thoughts and feelings of contentment, joy, and fulfillment—and the absence of severe distress.30 Wellness is a multifaceted condition that includes physical, psychological, and social aspects of an individual’s personal and professional life. Individuals experience a sense of wellness when they nurture their physical selves, minds, and relationships. People experience a sense of wellness when they balance their schedules, eat well, and maintain physical activity. Making time to enjoy family and friends also contributes to wellness.

Continue to: The culture of medicine often rewards...

The culture of medicine often rewards physician attitudes and behaviors that detract from wellness.31 Physicians internalize the culture of medicine that promotes perfectionism and downplays personal vulnerability.32 Physicians are reluctant to protect and preserve their wellness, believing self-sacrifice makes them good doctors. Physicians may spend countless hours counseling patients on the importance of wellness, but then work when ill or neglect their personal health needs and self-care—potentially decreasing their resilience and increasing the risk for burnout.31

Two paths to managing stress and preventing burnout

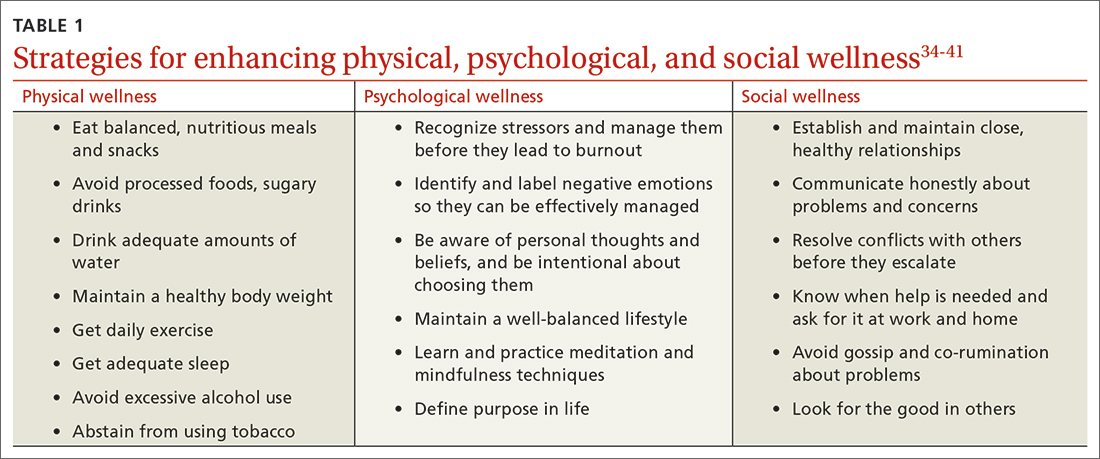

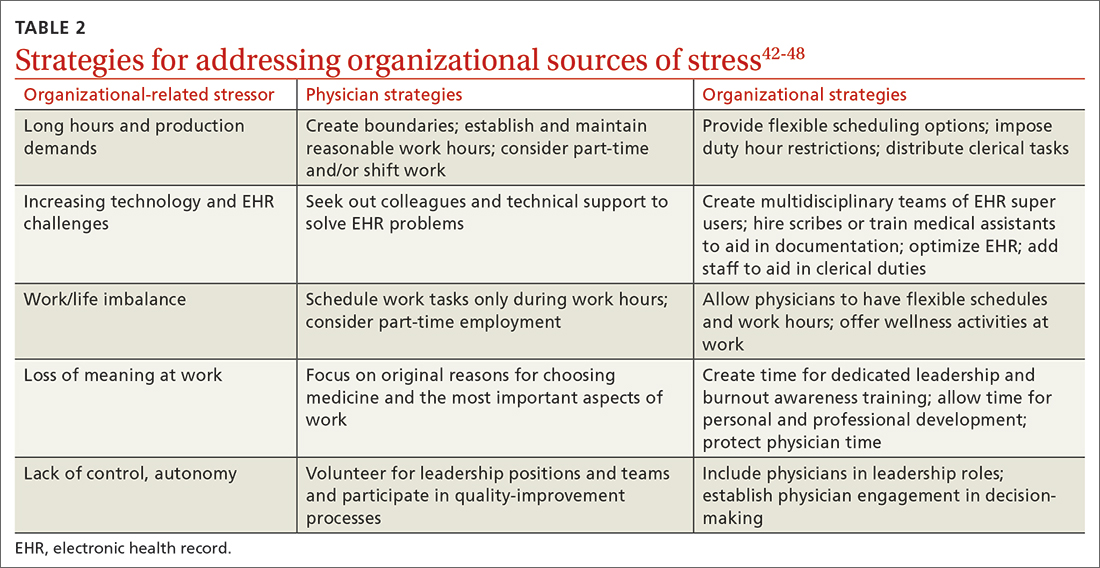

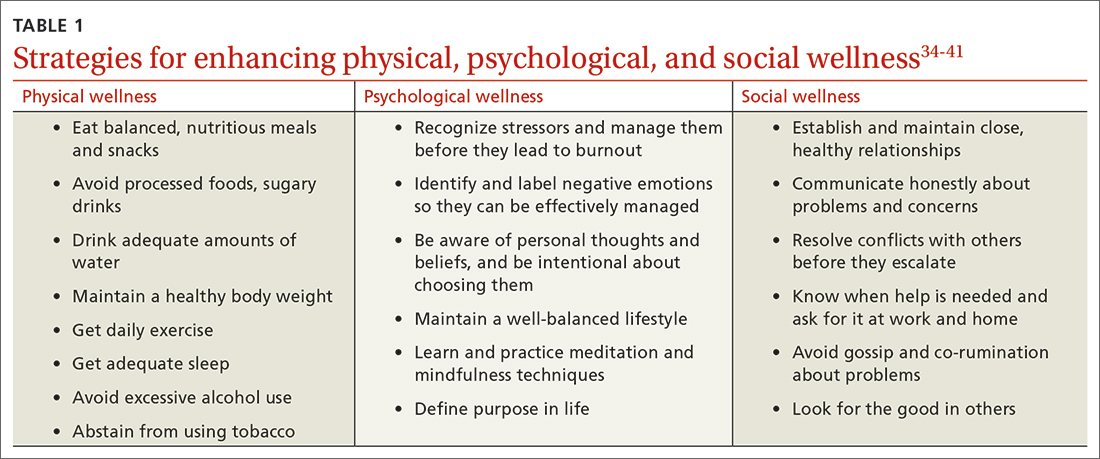

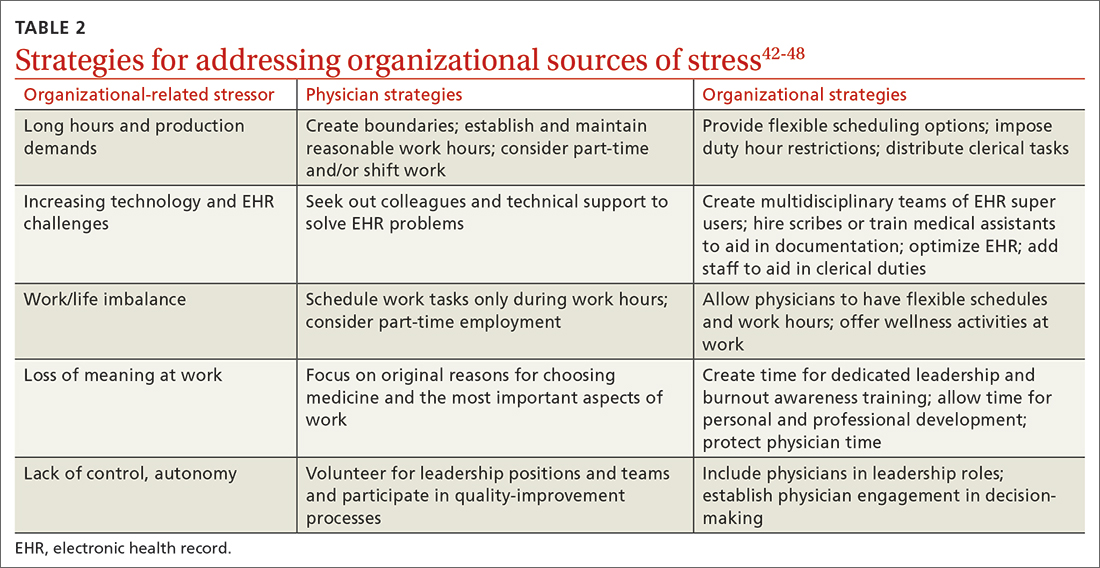

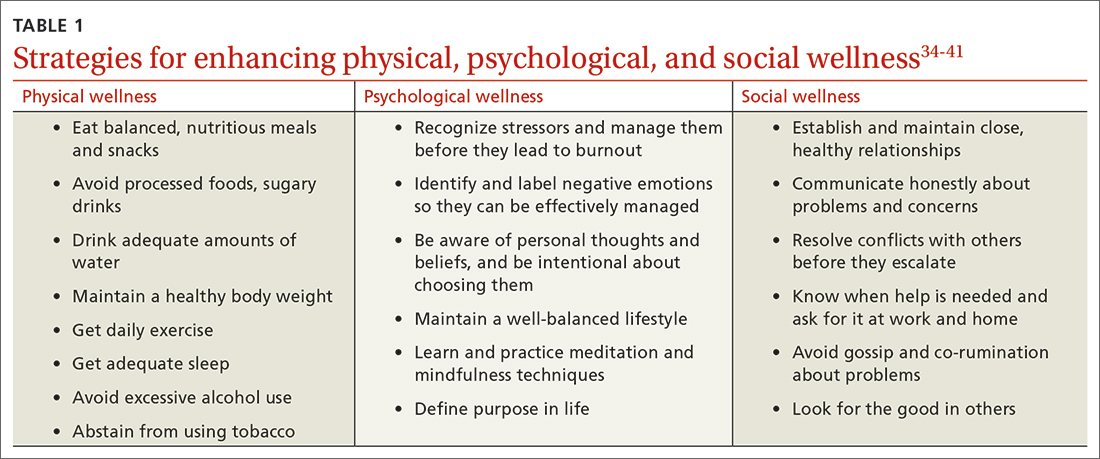

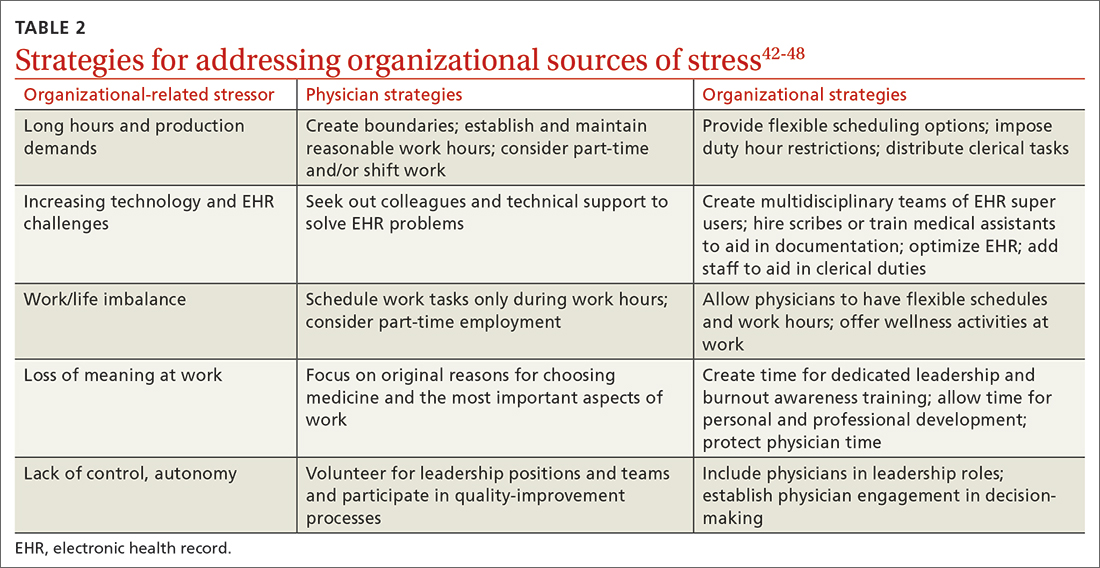

Patel and colleagues distinguish between 2 burnout intervention categories: (1) those that focus on individual physicians and (2) those that focus on the organizational environment.33 We find these distinctions useful and offer strategies for enhancing individual physician wellness (TABLE 134-41). Similar to West and colleagues,11 we offer strategies for addressing organizational sources of stress (TABLE 242-48). The following text describes these burnout intervention categories, emphasizing increasing self-care and changes that enable physicians to adapt effectively.

The recommendations outlined in this article are based on published stress and burnout literature, as well as the experiences of the authors. However, the number of randomized controlled studies of interventions aimed at reducing physician stress and burnout is limited. In addition, strategies proposed to reduce burnout in other professions may not address the unique stressors physicians encounter. Hence, our recommendations are limited. We have included interventions that seem optimal for individual physicians and the organizations that employ them.

Individual strategies target physical, psychological, and social wellness

Physician wellness strategies are divided into 3 categories: physical, psychological, and social wellness. Most strategies to improve physical wellness are widely known, evidence based, and recommended to patients by physicians.34-36 For example, most physicians advise their patients to eat healthy balanced meals, avoid unhealthy foods and beverages, maintain a healthy body weight, get daily exercise and adequate sleep, avoid excessive alcohol use, and abstain from tobacco use. However, discrepancies between physicians’ advice to patients and their own behaviors are common. Simply stated, physicians are well advised to follow their own advice regarding physical self-care.

CBT and mindfulness are key to psychological wellness. Recommendations for enhancing psychological wellness are primarily derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness principles and practices.37,38 CBT has been called the “gold standard” of psychotherapy, based on the breadth of research demonstrating that “no other form of psychotherapy has been shown to be systematically superior to CBT.”39

Continue to: CBT is based on the premise...

CBT is based on the premise that individuals’ thoughts and beliefs largely determine how they feel (emotions) and act (behaviors). Certain thoughts lead to positive feelings and effective behaviors, while others lead to negative feelings and less effective behaviors. For example, when a physician has self-critical or helpless thoughts (eg, “I’m just no good at managing my life”), they are more likely to feel unhappy and abandon problem-solving. In contrast, when a physician has self-affirming or hopeful thoughts (eg, “This is difficult, but I have the personal resources to succeed”), they are more likely to feel confident and act to solve problems.

Physicians vacillate between these thoughts and beliefs, and their emotions and behaviors follow accordingly. When hyper-focused on “the hassles of medicine,” physicians feel defeated, depressed, and anxious about their work. In contrast, when physicians recognize and challenge problematic thoughts and focus on what they love about medicine, they feel good and interact with patients and coworkers in positive and self-reinforcing ways.

Mindfulness can help reduce psychological stress and increase personal fulfillment. Mindfulness is characterized as being in the present moment, fully accepting “what is,” and having a sense of gratitude and compassion for self and others.40 In practice, mindfulness involves being intentional.

Dahl and colleagues41 describe a framework for human flourishing that includes 4 core dimensions of well-being (awareness, insight, connection, and purpose) that are all closely linked to mindful, intentional living. Based on their work, it is apparent that those who maintain a “heightened and flexible attentiveness” to their thoughts and feelings are likely to benefit by experiencing “improved mental health and psychological well-being.”41

However, the utility of CBT and mindfulness practices depends on receptivity to psychological interventions. Individuals who are not receptive may be hesitant to use these practices or likely will not benefit from them. Given these limitations of behavioral interventions, it would be helpful if more attention were paid to preventing and managing physician stress and burnout, especially through research focused on organizational changes.

Continue to: Supportive relationships are powerful

Supportive relationships are powerful. Finally, to enhance social wellness, it would be difficult to overstate the potential benefits of positive, supportive, close relationships.42 However, the demands of a career in medicine, starting in medical school, have the potential for inhibiting (rather than enhancing) close relationships.

Placing value on relationships with friends and family members is essential. As Dr. M began experiencing burnout, he felt increasingly lonely, yet he isolated himself from those who cared about him. Dr. A felt lonely at home, even though she was surrounded by family. Physicians are often reluctant to initiate vulnerable communication with others, believing “no one wants to hear about my problems.” However, by realizing the need for help and asking friends and family for emotional support, physicians can improve their wellness. Fostering supportive relationships can help provide the resilience needed to address organizational stressors.

Tackling organizational challenges

Long hours and pressure to see large numbers of patients (production demands) are a challenge across practice settings. Limiting work hours has been effective in improving the well-being of physician trainees but has had an inconsistent effect on burnout.43,44

Organizations can offer flexible scheduling, and physicians considering limiting work hours may switch to part-time status or shift work. However, decreasing work hours may have the unintended consequence of increased stress as some physicians feel pressure to do more in less time.45 Therefore, it’s important to set clear boundaries around work time and when and where work tasks are completed (eg, home vs office).

How we use technology matters. Given technology’s ever-increasing role in medicine, organizations must identify and use the most efficient, effective technology for managing clerical processes. When physicians participate in these decisions and share their experiences, technology is likely to be more user-friendly and impose less stress.46

Continue to: If technology contributes to stress...

If technology contributes to stress by being too complex or impractical, it’s important to identify individuals in the workplace (eg, IT support or “super-users”) to help address these challenges. Organizations can implement multidisciplinary teams to address EHR challenges and decrease physician stress and burnout by training support staff to assist with clerical duties, allowing physicians to focus on patient care.47,48 Such organizational-directed interventions will be most successful when physicians are included in the decision-making process.47

Take on leadership roles to influence change. Leadership may be formal (involving a title and authority) or informal (leading by example). Health care organizations that are committed to the well-being of physicians will make the effort to improve the systems in which physicians work. Physicians working in organizations that are reluctant to change have several choices: implement individual strategies, take on leadership roles to influence change, or reconsider their fit for the organization. Physicians in solo practice might consider joining others in solo practices to share systems (call, phone triage, technical resources, etc) to implement some of these interventions.

Dr. A and Dr. M implement new wellness strategies

Dr. A and Dr. M have recently committed to addressing stressors in their lives and improving their wellness. Dr. A has become more assertive at work, highlighting her need for additional resources to function effectively. In response, her practice has hired scribes to assist in documenting visits. This success has inspired Dr. A to pay attention to her lifestyle choices. Gradually, she has begun to exercise and engage in healthy eating.

Dr. M has begun to utilize resources at his medical center to improve his EHR efficiency and patient flow. He has taken steps to address his financial concerns, developing a budget and spending judiciously. He practices mindfulness and ensures that he gets at least 7 hours of sleep per night, improving his mental and physical health. By doing so, he has more energy to connect with friends, exercise, and date.

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret L. Smith, MD, MPH, MHSA, KUMC, Family Medicine and Community Health, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard – Mailstop 4010, Kansas City, KS 66160; msmith33@kumc.edu

1. Kane L. Physician burnout & depression report: stress, anxiety, and anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664

2. Lockwood L, Patel N, Bukelis I. 45.5 Physician burnout and the COVID-19 pandemic: the silent epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:S242. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.09.354

3. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1681-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023

4. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311

5. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99-113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205

6. World Health Organization. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. May 28, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

7. Berg S. WHO adds burnout to ICD-11. What it means for physicians. American Medical Association. July 23, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/who-adds-burnout-icd-11-what-it-means-physicians

8. Brown SD, Goske MJ, Johnson CM. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:479-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.11.029

9. Williams ES, Rathert C, Buttigieg SC. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77:371-386. doi: 10.1177/ 1077558719856787

10. Yates SW. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am J Med. 2020;133:160-164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.034

11. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752

12. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017-1022. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00227-4

13. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

14. American Institute of Stress. What is stress? April 29, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.stress.org/daily-life

15. Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A, et al. Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: a review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:353-359. doi: 10.1097/NMD. 0000000000000130

16. Fitzpatrick K, Patterson R, Morley K, et al. Physician wellness during a pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:83-87. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48472

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836-848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007

18. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:419-426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121

19. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961

20. Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic health record effects on work-life balance and burnout within the I3 Population Collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:479-484. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00123.1

21. Fares J, Al Tabosh H, Saadeddin Z, et al. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8:75-81. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.177299

22. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018; 8:98. doi: 10.3390/bs8110098

23. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513-519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7

24. Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

25. Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169-177. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S195633.

26. John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4A and 54. Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California; 1991.

27. Wurm W, Vogel K, Holl A, et al. Depression-burnout overlap in physicians. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149913

28. Mehta SS, Edwards ML. Suffering in silence: Mental health stigma and physicians’ licensing fears. Am J Psychiatry Resid J. 2018;13:2-4.

29. Adam AR, Golu FT. Prevalence of depression among physicians: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Ro Med J. 2021;68:327-337. doi: 10.37897/RMJ.2021.3.1

30. Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:94-108. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0781-6

31. Shanafelt TD, Schein E, Minor LB, et al. Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1556-1566. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026

32. Horan S, Flaxman PE, Stride CB. The perfect recovery? Interactive influence of perfectionism and spillover work tasks on changes in exhaustion and mood around a vacation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2021;26:86-107. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000208

33. Patel RS, Sekhri S, Bhimanadham NN, et al. A review on strategies to manage physician burnout. Cureus. 2019;11:e4805. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4805

34. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

35. Kim ES, Chen Y, Nakamura JS, et al. Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: an outcome-wide approach. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:137-147. doi: 10.1177/08901171211038545

36. Ogilvie RP, Patel SR. The epidemiology of sleep and obesity. Sleep Health. 2017;3:383-388. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.07.013

37. Fordham B, Sugavanam T, Edwards K, et al. The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: a meta-review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:21-29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005292

38. Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

39. David D, Cristea I, Hofmann SG. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

40. Fendel JC, Bürkle JJ, Göritz AS. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout and stress in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2021;96:751-764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003936

41. Dahl CJ, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Davidson RJ. The plasticity of well-being: a training-based framework for the cultivation of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:32197-32206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014859117

42. Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu Rev Psychol. 2018;69:437-458. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

43. Desai SV, Asch DA, Bellini LM, et al. Education outcomes in a duty-hour flexibility trial in internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1494-1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800965

44. Shea JA, Bellini LM, Dinges DF, et al. Impact of protected sleep period for internal medicine interns on overnight call on depression, burnout, and empathy. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:256-263. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00241.1

45. Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M, et al. Have restricted working hours reduced junior doctors’ experience of fatigue? A focus group and telephone interview study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004222. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004222

46. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

47. Sequeira L, Almilaji K, Strudwick G, et al. EHR “SWAT” teams: a physician engagement initiative to improve Electronic Health Record (EHR) experiences and mitigate possible causes of EHR-related burnout. JAMA Open. 2021;4:1-7. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab018

48. Smith PC, Lyon C, English AF, et al. Practice transformation under the University of Colorado’s primary care redesign model. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17:S24-S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.2424

Meet Dr. A and Dr. M

Dr. A is a 50-year-old family physician who provides prenatal care in a busy practice. She sees patients in eight 4-hour clinic sessions per week and is on inpatient call 1 week out of every 2 months. Dr. A has become disillusioned with her practice. She typically works until 7

Dr. M is a single, 32-year-old family physician working at an academic medical center. Dr. M is unhappy in his job, is trying to grow his practice, and views himself as having little impact or autonomy. He finds himself lost while navigating the electronic health record (EHR) and struggles to be efficient in the clinic. Dr. M has multiple administrative responsibilities that require him to work evenings and weekends. Debt from medical school loans also motivates him to moonlight several weekends per month. Over the past few months, Dr. M has become frustrated and discouraged, making his depression more difficult to manage. He feels drained by the time he arrives home, where he lives alone. He has stopped exercising, socializing with friends, and dating. Dr. M often wonders if he is in the wrong profession.

Defining burnout, stress, and wellness

Dr. A and Dr. M are experiencing symptoms of burnout, common to physicians and other health care professionals. Recent studies showed an increase in burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 In a survey using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), approximately 44% of physicians reported at least one symptom of burnout.3 After adjusting for age, gender, relationship status, and hours worked per week, physicians were found to be at greater risk for burnout than nonphysician workers.3 The latest Medscape physician burnout survey found an increase in burnout among US physicians from 42% in 2021 to 47% in 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Rates of burnout were even higher among family physicians and other frontline (eg, emergency, infectious disease, and critical care) physicians.1

Burnout has 3 key dimensions: (1) overwhelming exhaustion; (2) feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job; and (3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4 The MBI is considered the standard tool for research in the field of burnout and has been repeatedly assessed for reliability and validity.4 The original MBI includes such items as: “I feel emotionally drained from my work,” “I feel like I’m working too hard on my job,” and “I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally.”5

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is an occupational phenomenon associated with chronic work-related stress that is not successfully managed.6 This definition emphasizes work stress as the cause of burnout, thus highlighting the importance of addressing the work environment.7 Physician burnout can affect physician health and wellness and the quality of patient care.8-13 Because of the cost of burnout to individuals and the health care system, it is important to understand stressors that can lead to physician burnout.

Stress has been described as “physical, mental, or emotional strain or tension … when a person perceives that demands exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize.”14 Work-related sources of stress affecting practicing physicians include long workdays, multiple bureaucratic tasks, lack of autonomy/control, and complex patients.1,15

The COVID-19 pandemic is a stressor that increased physicians’ exposure to patient suffering and deaths and physicians’ vulnerability to disease at work.16 Physicians taking care of patients with COVID-19 risk infection and the possibility of infecting others.Online health records are another source of stress for many physicians.17,18 Access to online health records on personal devices can blur the line between work and home. For each hour of direct patient contact, a physician spends an additional 2 hours interacting with an EHR.19 Among family physicians and other primary care physicians, increased EHR interaction outside clinic hours has been associated with decreased workplace satisfaction and increased rates of burnout.11,19,20 Time spent on non-patient-facing clinical tasks, such as peer-to-peer reviews and billing queries, contributes more to burnout than clinic time alone.17

Continue to: These and other organizational factors...

These and other organizational factors contribute to the stress experienced by physicians. Many describe themselves as feeling consumed by their work. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians (and the rest of the health care team) had to quickly learn how to conduct virtual office visits. Clerical responsibilities increased as patients relied more on patient portals and telephone calls to receive care.

Who is predisposed to burnout? Although burnout is a work-related syndrome, studies have shown an increase in burnout associated with individual (ie, personal) factors. For example, female physicians have been shown to have higher rates of burnout compared with male physicians.1,3 The stress of balancing the demands of the profession can begin during medical school and residency, with younger physicians having nearly twice the risk for stress-related symptoms when compared with older colleagues.15,20-23 Having a child younger than 21 years old, and other personal factors related to balancing family and life demands, increases the likelihood of burnout.11,21,22

Physicians with certain personality types and predispositions are at increased risk for burnout.23-25 For example, neuroticism on the Big Five Personality Inventory (one of the most well-known of the psychology inventories) is associated with an increased risk for burnout. Neuroticism may manifest as sadness or related emotional dysregulation (eg, irritability, anxiety).26 Other traits measured by the Big Five Personality Inventory include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.26

A history of depression is also associated with an increased risk for burnout.27 Although depression and burnout are separate conditions, a 2016 study found significant overlap between the two.27 Physicians in this study who were depressed were more likely to experience burnout symptoms (87.5%); however, only 26.2% of physicians experiencing burnout were diagnosed as having depression.27 Rates of depression are higher among physicians when compared with nonphysicians, yet physicians are less likely to seek help due to fear of stigma and potential licensing concerns.28,29 Because of this, when physicians experience depressive symptoms, they may respond by working harder rather than seeking professional counseling or emotional support. They might believe that “asking for help is a sign of weakness,” thus sacrificing their wellness.

Wellness encompasses a sense of thriving characterized by thoughts and feelings of contentment, joy, and fulfillment—and the absence of severe distress.30 Wellness is a multifaceted condition that includes physical, psychological, and social aspects of an individual’s personal and professional life. Individuals experience a sense of wellness when they nurture their physical selves, minds, and relationships. People experience a sense of wellness when they balance their schedules, eat well, and maintain physical activity. Making time to enjoy family and friends also contributes to wellness.

Continue to: The culture of medicine often rewards...

The culture of medicine often rewards physician attitudes and behaviors that detract from wellness.31 Physicians internalize the culture of medicine that promotes perfectionism and downplays personal vulnerability.32 Physicians are reluctant to protect and preserve their wellness, believing self-sacrifice makes them good doctors. Physicians may spend countless hours counseling patients on the importance of wellness, but then work when ill or neglect their personal health needs and self-care—potentially decreasing their resilience and increasing the risk for burnout.31

Two paths to managing stress and preventing burnout

Patel and colleagues distinguish between 2 burnout intervention categories: (1) those that focus on individual physicians and (2) those that focus on the organizational environment.33 We find these distinctions useful and offer strategies for enhancing individual physician wellness (TABLE 134-41). Similar to West and colleagues,11 we offer strategies for addressing organizational sources of stress (TABLE 242-48). The following text describes these burnout intervention categories, emphasizing increasing self-care and changes that enable physicians to adapt effectively.

The recommendations outlined in this article are based on published stress and burnout literature, as well as the experiences of the authors. However, the number of randomized controlled studies of interventions aimed at reducing physician stress and burnout is limited. In addition, strategies proposed to reduce burnout in other professions may not address the unique stressors physicians encounter. Hence, our recommendations are limited. We have included interventions that seem optimal for individual physicians and the organizations that employ them.

Individual strategies target physical, psychological, and social wellness

Physician wellness strategies are divided into 3 categories: physical, psychological, and social wellness. Most strategies to improve physical wellness are widely known, evidence based, and recommended to patients by physicians.34-36 For example, most physicians advise their patients to eat healthy balanced meals, avoid unhealthy foods and beverages, maintain a healthy body weight, get daily exercise and adequate sleep, avoid excessive alcohol use, and abstain from tobacco use. However, discrepancies between physicians’ advice to patients and their own behaviors are common. Simply stated, physicians are well advised to follow their own advice regarding physical self-care.

CBT and mindfulness are key to psychological wellness. Recommendations for enhancing psychological wellness are primarily derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness principles and practices.37,38 CBT has been called the “gold standard” of psychotherapy, based on the breadth of research demonstrating that “no other form of psychotherapy has been shown to be systematically superior to CBT.”39

Continue to: CBT is based on the premise...

CBT is based on the premise that individuals’ thoughts and beliefs largely determine how they feel (emotions) and act (behaviors). Certain thoughts lead to positive feelings and effective behaviors, while others lead to negative feelings and less effective behaviors. For example, when a physician has self-critical or helpless thoughts (eg, “I’m just no good at managing my life”), they are more likely to feel unhappy and abandon problem-solving. In contrast, when a physician has self-affirming or hopeful thoughts (eg, “This is difficult, but I have the personal resources to succeed”), they are more likely to feel confident and act to solve problems.

Physicians vacillate between these thoughts and beliefs, and their emotions and behaviors follow accordingly. When hyper-focused on “the hassles of medicine,” physicians feel defeated, depressed, and anxious about their work. In contrast, when physicians recognize and challenge problematic thoughts and focus on what they love about medicine, they feel good and interact with patients and coworkers in positive and self-reinforcing ways.

Mindfulness can help reduce psychological stress and increase personal fulfillment. Mindfulness is characterized as being in the present moment, fully accepting “what is,” and having a sense of gratitude and compassion for self and others.40 In practice, mindfulness involves being intentional.

Dahl and colleagues41 describe a framework for human flourishing that includes 4 core dimensions of well-being (awareness, insight, connection, and purpose) that are all closely linked to mindful, intentional living. Based on their work, it is apparent that those who maintain a “heightened and flexible attentiveness” to their thoughts and feelings are likely to benefit by experiencing “improved mental health and psychological well-being.”41

However, the utility of CBT and mindfulness practices depends on receptivity to psychological interventions. Individuals who are not receptive may be hesitant to use these practices or likely will not benefit from them. Given these limitations of behavioral interventions, it would be helpful if more attention were paid to preventing and managing physician stress and burnout, especially through research focused on organizational changes.

Continue to: Supportive relationships are powerful

Supportive relationships are powerful. Finally, to enhance social wellness, it would be difficult to overstate the potential benefits of positive, supportive, close relationships.42 However, the demands of a career in medicine, starting in medical school, have the potential for inhibiting (rather than enhancing) close relationships.

Placing value on relationships with friends and family members is essential. As Dr. M began experiencing burnout, he felt increasingly lonely, yet he isolated himself from those who cared about him. Dr. A felt lonely at home, even though she was surrounded by family. Physicians are often reluctant to initiate vulnerable communication with others, believing “no one wants to hear about my problems.” However, by realizing the need for help and asking friends and family for emotional support, physicians can improve their wellness. Fostering supportive relationships can help provide the resilience needed to address organizational stressors.

Tackling organizational challenges

Long hours and pressure to see large numbers of patients (production demands) are a challenge across practice settings. Limiting work hours has been effective in improving the well-being of physician trainees but has had an inconsistent effect on burnout.43,44

Organizations can offer flexible scheduling, and physicians considering limiting work hours may switch to part-time status or shift work. However, decreasing work hours may have the unintended consequence of increased stress as some physicians feel pressure to do more in less time.45 Therefore, it’s important to set clear boundaries around work time and when and where work tasks are completed (eg, home vs office).

How we use technology matters. Given technology’s ever-increasing role in medicine, organizations must identify and use the most efficient, effective technology for managing clerical processes. When physicians participate in these decisions and share their experiences, technology is likely to be more user-friendly and impose less stress.46

Continue to: If technology contributes to stress...

If technology contributes to stress by being too complex or impractical, it’s important to identify individuals in the workplace (eg, IT support or “super-users”) to help address these challenges. Organizations can implement multidisciplinary teams to address EHR challenges and decrease physician stress and burnout by training support staff to assist with clerical duties, allowing physicians to focus on patient care.47,48 Such organizational-directed interventions will be most successful when physicians are included in the decision-making process.47

Take on leadership roles to influence change. Leadership may be formal (involving a title and authority) or informal (leading by example). Health care organizations that are committed to the well-being of physicians will make the effort to improve the systems in which physicians work. Physicians working in organizations that are reluctant to change have several choices: implement individual strategies, take on leadership roles to influence change, or reconsider their fit for the organization. Physicians in solo practice might consider joining others in solo practices to share systems (call, phone triage, technical resources, etc) to implement some of these interventions.

Dr. A and Dr. M implement new wellness strategies

Dr. A and Dr. M have recently committed to addressing stressors in their lives and improving their wellness. Dr. A has become more assertive at work, highlighting her need for additional resources to function effectively. In response, her practice has hired scribes to assist in documenting visits. This success has inspired Dr. A to pay attention to her lifestyle choices. Gradually, she has begun to exercise and engage in healthy eating.

Dr. M has begun to utilize resources at his medical center to improve his EHR efficiency and patient flow. He has taken steps to address his financial concerns, developing a budget and spending judiciously. He practices mindfulness and ensures that he gets at least 7 hours of sleep per night, improving his mental and physical health. By doing so, he has more energy to connect with friends, exercise, and date.

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret L. Smith, MD, MPH, MHSA, KUMC, Family Medicine and Community Health, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard – Mailstop 4010, Kansas City, KS 66160; msmith33@kumc.edu

Meet Dr. A and Dr. M

Dr. A is a 50-year-old family physician who provides prenatal care in a busy practice. She sees patients in eight 4-hour clinic sessions per week and is on inpatient call 1 week out of every 2 months. Dr. A has become disillusioned with her practice. She typically works until 7

Dr. M is a single, 32-year-old family physician working at an academic medical center. Dr. M is unhappy in his job, is trying to grow his practice, and views himself as having little impact or autonomy. He finds himself lost while navigating the electronic health record (EHR) and struggles to be efficient in the clinic. Dr. M has multiple administrative responsibilities that require him to work evenings and weekends. Debt from medical school loans also motivates him to moonlight several weekends per month. Over the past few months, Dr. M has become frustrated and discouraged, making his depression more difficult to manage. He feels drained by the time he arrives home, where he lives alone. He has stopped exercising, socializing with friends, and dating. Dr. M often wonders if he is in the wrong profession.

Defining burnout, stress, and wellness

Dr. A and Dr. M are experiencing symptoms of burnout, common to physicians and other health care professionals. Recent studies showed an increase in burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic.1,2 In a survey using the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI), approximately 44% of physicians reported at least one symptom of burnout.3 After adjusting for age, gender, relationship status, and hours worked per week, physicians were found to be at greater risk for burnout than nonphysician workers.3 The latest Medscape physician burnout survey found an increase in burnout among US physicians from 42% in 2021 to 47% in 2022 during the COVID-19 pandemic.1 Rates of burnout were even higher among family physicians and other frontline (eg, emergency, infectious disease, and critical care) physicians.1

Burnout has 3 key dimensions: (1) overwhelming exhaustion; (2) feelings of cynicism and detachment from the job; and (3) a sense of ineffectiveness and lack of accomplishment.4 The MBI is considered the standard tool for research in the field of burnout and has been repeatedly assessed for reliability and validity.4 The original MBI includes such items as: “I feel emotionally drained from my work,” “I feel like I’m working too hard on my job,” and “I worry that this job is hardening me emotionally.”5

According to the World Health Organization, burnout is an occupational phenomenon associated with chronic work-related stress that is not successfully managed.6 This definition emphasizes work stress as the cause of burnout, thus highlighting the importance of addressing the work environment.7 Physician burnout can affect physician health and wellness and the quality of patient care.8-13 Because of the cost of burnout to individuals and the health care system, it is important to understand stressors that can lead to physician burnout.

Stress has been described as “physical, mental, or emotional strain or tension … when a person perceives that demands exceed the personal and social resources the individual is able to mobilize.”14 Work-related sources of stress affecting practicing physicians include long workdays, multiple bureaucratic tasks, lack of autonomy/control, and complex patients.1,15

The COVID-19 pandemic is a stressor that increased physicians’ exposure to patient suffering and deaths and physicians’ vulnerability to disease at work.16 Physicians taking care of patients with COVID-19 risk infection and the possibility of infecting others.Online health records are another source of stress for many physicians.17,18 Access to online health records on personal devices can blur the line between work and home. For each hour of direct patient contact, a physician spends an additional 2 hours interacting with an EHR.19 Among family physicians and other primary care physicians, increased EHR interaction outside clinic hours has been associated with decreased workplace satisfaction and increased rates of burnout.11,19,20 Time spent on non-patient-facing clinical tasks, such as peer-to-peer reviews and billing queries, contributes more to burnout than clinic time alone.17

Continue to: These and other organizational factors...

These and other organizational factors contribute to the stress experienced by physicians. Many describe themselves as feeling consumed by their work. At the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, physicians (and the rest of the health care team) had to quickly learn how to conduct virtual office visits. Clerical responsibilities increased as patients relied more on patient portals and telephone calls to receive care.

Who is predisposed to burnout? Although burnout is a work-related syndrome, studies have shown an increase in burnout associated with individual (ie, personal) factors. For example, female physicians have been shown to have higher rates of burnout compared with male physicians.1,3 The stress of balancing the demands of the profession can begin during medical school and residency, with younger physicians having nearly twice the risk for stress-related symptoms when compared with older colleagues.15,20-23 Having a child younger than 21 years old, and other personal factors related to balancing family and life demands, increases the likelihood of burnout.11,21,22

Physicians with certain personality types and predispositions are at increased risk for burnout.23-25 For example, neuroticism on the Big Five Personality Inventory (one of the most well-known of the psychology inventories) is associated with an increased risk for burnout. Neuroticism may manifest as sadness or related emotional dysregulation (eg, irritability, anxiety).26 Other traits measured by the Big Five Personality Inventory include extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience.26

A history of depression is also associated with an increased risk for burnout.27 Although depression and burnout are separate conditions, a 2016 study found significant overlap between the two.27 Physicians in this study who were depressed were more likely to experience burnout symptoms (87.5%); however, only 26.2% of physicians experiencing burnout were diagnosed as having depression.27 Rates of depression are higher among physicians when compared with nonphysicians, yet physicians are less likely to seek help due to fear of stigma and potential licensing concerns.28,29 Because of this, when physicians experience depressive symptoms, they may respond by working harder rather than seeking professional counseling or emotional support. They might believe that “asking for help is a sign of weakness,” thus sacrificing their wellness.

Wellness encompasses a sense of thriving characterized by thoughts and feelings of contentment, joy, and fulfillment—and the absence of severe distress.30 Wellness is a multifaceted condition that includes physical, psychological, and social aspects of an individual’s personal and professional life. Individuals experience a sense of wellness when they nurture their physical selves, minds, and relationships. People experience a sense of wellness when they balance their schedules, eat well, and maintain physical activity. Making time to enjoy family and friends also contributes to wellness.

Continue to: The culture of medicine often rewards...

The culture of medicine often rewards physician attitudes and behaviors that detract from wellness.31 Physicians internalize the culture of medicine that promotes perfectionism and downplays personal vulnerability.32 Physicians are reluctant to protect and preserve their wellness, believing self-sacrifice makes them good doctors. Physicians may spend countless hours counseling patients on the importance of wellness, but then work when ill or neglect their personal health needs and self-care—potentially decreasing their resilience and increasing the risk for burnout.31

Two paths to managing stress and preventing burnout

Patel and colleagues distinguish between 2 burnout intervention categories: (1) those that focus on individual physicians and (2) those that focus on the organizational environment.33 We find these distinctions useful and offer strategies for enhancing individual physician wellness (TABLE 134-41). Similar to West and colleagues,11 we offer strategies for addressing organizational sources of stress (TABLE 242-48). The following text describes these burnout intervention categories, emphasizing increasing self-care and changes that enable physicians to adapt effectively.

The recommendations outlined in this article are based on published stress and burnout literature, as well as the experiences of the authors. However, the number of randomized controlled studies of interventions aimed at reducing physician stress and burnout is limited. In addition, strategies proposed to reduce burnout in other professions may not address the unique stressors physicians encounter. Hence, our recommendations are limited. We have included interventions that seem optimal for individual physicians and the organizations that employ them.

Individual strategies target physical, psychological, and social wellness

Physician wellness strategies are divided into 3 categories: physical, psychological, and social wellness. Most strategies to improve physical wellness are widely known, evidence based, and recommended to patients by physicians.34-36 For example, most physicians advise their patients to eat healthy balanced meals, avoid unhealthy foods and beverages, maintain a healthy body weight, get daily exercise and adequate sleep, avoid excessive alcohol use, and abstain from tobacco use. However, discrepancies between physicians’ advice to patients and their own behaviors are common. Simply stated, physicians are well advised to follow their own advice regarding physical self-care.

CBT and mindfulness are key to psychological wellness. Recommendations for enhancing psychological wellness are primarily derived from cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and mindfulness principles and practices.37,38 CBT has been called the “gold standard” of psychotherapy, based on the breadth of research demonstrating that “no other form of psychotherapy has been shown to be systematically superior to CBT.”39

Continue to: CBT is based on the premise...

CBT is based on the premise that individuals’ thoughts and beliefs largely determine how they feel (emotions) and act (behaviors). Certain thoughts lead to positive feelings and effective behaviors, while others lead to negative feelings and less effective behaviors. For example, when a physician has self-critical or helpless thoughts (eg, “I’m just no good at managing my life”), they are more likely to feel unhappy and abandon problem-solving. In contrast, when a physician has self-affirming or hopeful thoughts (eg, “This is difficult, but I have the personal resources to succeed”), they are more likely to feel confident and act to solve problems.

Physicians vacillate between these thoughts and beliefs, and their emotions and behaviors follow accordingly. When hyper-focused on “the hassles of medicine,” physicians feel defeated, depressed, and anxious about their work. In contrast, when physicians recognize and challenge problematic thoughts and focus on what they love about medicine, they feel good and interact with patients and coworkers in positive and self-reinforcing ways.

Mindfulness can help reduce psychological stress and increase personal fulfillment. Mindfulness is characterized as being in the present moment, fully accepting “what is,” and having a sense of gratitude and compassion for self and others.40 In practice, mindfulness involves being intentional.

Dahl and colleagues41 describe a framework for human flourishing that includes 4 core dimensions of well-being (awareness, insight, connection, and purpose) that are all closely linked to mindful, intentional living. Based on their work, it is apparent that those who maintain a “heightened and flexible attentiveness” to their thoughts and feelings are likely to benefit by experiencing “improved mental health and psychological well-being.”41

However, the utility of CBT and mindfulness practices depends on receptivity to psychological interventions. Individuals who are not receptive may be hesitant to use these practices or likely will not benefit from them. Given these limitations of behavioral interventions, it would be helpful if more attention were paid to preventing and managing physician stress and burnout, especially through research focused on organizational changes.

Continue to: Supportive relationships are powerful

Supportive relationships are powerful. Finally, to enhance social wellness, it would be difficult to overstate the potential benefits of positive, supportive, close relationships.42 However, the demands of a career in medicine, starting in medical school, have the potential for inhibiting (rather than enhancing) close relationships.

Placing value on relationships with friends and family members is essential. As Dr. M began experiencing burnout, he felt increasingly lonely, yet he isolated himself from those who cared about him. Dr. A felt lonely at home, even though she was surrounded by family. Physicians are often reluctant to initiate vulnerable communication with others, believing “no one wants to hear about my problems.” However, by realizing the need for help and asking friends and family for emotional support, physicians can improve their wellness. Fostering supportive relationships can help provide the resilience needed to address organizational stressors.

Tackling organizational challenges

Long hours and pressure to see large numbers of patients (production demands) are a challenge across practice settings. Limiting work hours has been effective in improving the well-being of physician trainees but has had an inconsistent effect on burnout.43,44

Organizations can offer flexible scheduling, and physicians considering limiting work hours may switch to part-time status or shift work. However, decreasing work hours may have the unintended consequence of increased stress as some physicians feel pressure to do more in less time.45 Therefore, it’s important to set clear boundaries around work time and when and where work tasks are completed (eg, home vs office).

How we use technology matters. Given technology’s ever-increasing role in medicine, organizations must identify and use the most efficient, effective technology for managing clerical processes. When physicians participate in these decisions and share their experiences, technology is likely to be more user-friendly and impose less stress.46

Continue to: If technology contributes to stress...

If technology contributes to stress by being too complex or impractical, it’s important to identify individuals in the workplace (eg, IT support or “super-users”) to help address these challenges. Organizations can implement multidisciplinary teams to address EHR challenges and decrease physician stress and burnout by training support staff to assist with clerical duties, allowing physicians to focus on patient care.47,48 Such organizational-directed interventions will be most successful when physicians are included in the decision-making process.47

Take on leadership roles to influence change. Leadership may be formal (involving a title and authority) or informal (leading by example). Health care organizations that are committed to the well-being of physicians will make the effort to improve the systems in which physicians work. Physicians working in organizations that are reluctant to change have several choices: implement individual strategies, take on leadership roles to influence change, or reconsider their fit for the organization. Physicians in solo practice might consider joining others in solo practices to share systems (call, phone triage, technical resources, etc) to implement some of these interventions.

Dr. A and Dr. M implement new wellness strategies

Dr. A and Dr. M have recently committed to addressing stressors in their lives and improving their wellness. Dr. A has become more assertive at work, highlighting her need for additional resources to function effectively. In response, her practice has hired scribes to assist in documenting visits. This success has inspired Dr. A to pay attention to her lifestyle choices. Gradually, she has begun to exercise and engage in healthy eating.

Dr. M has begun to utilize resources at his medical center to improve his EHR efficiency and patient flow. He has taken steps to address his financial concerns, developing a budget and spending judiciously. He practices mindfulness and ensures that he gets at least 7 hours of sleep per night, improving his mental and physical health. By doing so, he has more energy to connect with friends, exercise, and date.

CORRESPONDENCE

Margaret L. Smith, MD, MPH, MHSA, KUMC, Family Medicine and Community Health, 3901 Rainbow Boulevard – Mailstop 4010, Kansas City, KS 66160; msmith33@kumc.edu

1. Kane L. Physician burnout & depression report: stress, anxiety, and anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664

2. Lockwood L, Patel N, Bukelis I. 45.5 Physician burnout and the COVID-19 pandemic: the silent epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:S242. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.09.354

3. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1681-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023

4. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311

5. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99-113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205

6. World Health Organization. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. May 28, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

7. Berg S. WHO adds burnout to ICD-11. What it means for physicians. American Medical Association. July 23, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/who-adds-burnout-icd-11-what-it-means-physicians

8. Brown SD, Goske MJ, Johnson CM. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:479-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.11.029

9. Williams ES, Rathert C, Buttigieg SC. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77:371-386. doi: 10.1177/ 1077558719856787

10. Yates SW. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am J Med. 2020;133:160-164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.034

11. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752

12. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017-1022. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00227-4

13. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

14. American Institute of Stress. What is stress? April 29, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.stress.org/daily-life

15. Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A, et al. Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: a review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:353-359. doi: 10.1097/NMD. 0000000000000130

16. Fitzpatrick K, Patterson R, Morley K, et al. Physician wellness during a pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:83-87. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48472

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836-848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007

18. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:419-426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121

19. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961

20. Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic health record effects on work-life balance and burnout within the I3 Population Collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:479-484. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00123.1

21. Fares J, Al Tabosh H, Saadeddin Z, et al. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8:75-81. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.177299

22. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018; 8:98. doi: 10.3390/bs8110098

23. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513-519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7

24. Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

25. Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169-177. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S195633.

26. John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4A and 54. Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California; 1991.

27. Wurm W, Vogel K, Holl A, et al. Depression-burnout overlap in physicians. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149913

28. Mehta SS, Edwards ML. Suffering in silence: Mental health stigma and physicians’ licensing fears. Am J Psychiatry Resid J. 2018;13:2-4.

29. Adam AR, Golu FT. Prevalence of depression among physicians: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Ro Med J. 2021;68:327-337. doi: 10.37897/RMJ.2021.3.1

30. Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:94-108. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0781-6

31. Shanafelt TD, Schein E, Minor LB, et al. Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1556-1566. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026

32. Horan S, Flaxman PE, Stride CB. The perfect recovery? Interactive influence of perfectionism and spillover work tasks on changes in exhaustion and mood around a vacation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2021;26:86-107. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000208

33. Patel RS, Sekhri S, Bhimanadham NN, et al. A review on strategies to manage physician burnout. Cureus. 2019;11:e4805. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4805

34. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

35. Kim ES, Chen Y, Nakamura JS, et al. Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: an outcome-wide approach. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:137-147. doi: 10.1177/08901171211038545

36. Ogilvie RP, Patel SR. The epidemiology of sleep and obesity. Sleep Health. 2017;3:383-388. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.07.013

37. Fordham B, Sugavanam T, Edwards K, et al. The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: a meta-review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:21-29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005292

38. Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

39. David D, Cristea I, Hofmann SG. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

40. Fendel JC, Bürkle JJ, Göritz AS. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout and stress in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2021;96:751-764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003936

41. Dahl CJ, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Davidson RJ. The plasticity of well-being: a training-based framework for the cultivation of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:32197-32206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014859117

42. Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu Rev Psychol. 2018;69:437-458. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

43. Desai SV, Asch DA, Bellini LM, et al. Education outcomes in a duty-hour flexibility trial in internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1494-1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800965

44. Shea JA, Bellini LM, Dinges DF, et al. Impact of protected sleep period for internal medicine interns on overnight call on depression, burnout, and empathy. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:256-263. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00241.1

45. Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M, et al. Have restricted working hours reduced junior doctors’ experience of fatigue? A focus group and telephone interview study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004222. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004222

46. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

47. Sequeira L, Almilaji K, Strudwick G, et al. EHR “SWAT” teams: a physician engagement initiative to improve Electronic Health Record (EHR) experiences and mitigate possible causes of EHR-related burnout. JAMA Open. 2021;4:1-7. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab018

48. Smith PC, Lyon C, English AF, et al. Practice transformation under the University of Colorado’s primary care redesign model. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17:S24-S32. doi: 10.1370/afm.2424

1. Kane L. Physician burnout & depression report: stress, anxiety, and anger. Medscape. January 21, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.medscape.com/slideshow/2022-lifestyle-burnout-6014664

2. Lockwood L, Patel N, Bukelis I. 45.5 Physician burnout and the COVID-19 pandemic: the silent epidemic. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;60:S242. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2021.09.354

3. Shanafelt TD, West CP, Sinsky C, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life integration in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2017. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1681-1694. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.10.023

4. Maslach C, Leiter MP. Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry. 2016;15:103-111. doi: 10.1002/wps.20311

5. Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2:99-113. doi: 10.1002/job.4030020205

6. World Health Organization. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases. May 28, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.who.int/news/item/28-05-2019-burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon-international-classification-of-diseases

7. Berg S. WHO adds burnout to ICD-11. What it means for physicians. American Medical Association. July 23, 2019. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/who-adds-burnout-icd-11-what-it-means-physicians

8. Brown SD, Goske MJ, Johnson CM. Beyond substance abuse: stress, burnout, and depression as causes of physician impairment and disruptive behavior. J Am Coll Radiol. 2009;6:479-485. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2008.11.029

9. Williams ES, Rathert C, Buttigieg SC. The personal and professional consequences of physician burnout: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2020;77:371-386. doi: 10.1177/ 1077558719856787

10. Yates SW. Physician Stress and Burnout. Am J Med. 2020;133:160-164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.08.034

11. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283:516-529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752

12. Firth-Cozens J, Greenhalgh J. Doctors’ perceptions of the links between stress and lowered clinical care. Soc Sci Med. 1997;44:1017-1022. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(96)00227-4

13. Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, et al. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141

14. American Institute of Stress. What is stress? April 29, 2022. Accessed February 23, 2023. www.stress.org/daily-life

15. Regehr C, Glancy D, Pitts A, et al. Interventions to reduce the consequences of stress in physicians: a review and meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2014;202:353-359. doi: 10.1097/NMD. 0000000000000130

16. Fitzpatrick K, Patterson R, Morley K, et al. Physician wellness during a pandemic. West J Emerg Med. 2020;21:83-87. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2020.7.48472

17. Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91:836-848. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007

18. Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, et al. Tethered to the EHR: primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15:419-426. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121

19. Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165:753-760. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961

20. Robertson SL, Robinson MD, Reid A. Electronic health record effects on work-life balance and burnout within the I3 Population Collaborative. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:479-484. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00123.1

21. Fares J, Al Tabosh H, Saadeddin Z, et al. Stress, burnout and coping strategies in preclinical medical students. N Am J Med Sci. 2016;8:75-81. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.177299

22. Patel RS, Bachu R, Adikey A, et al. Factors related to physician burnout and its consequences: a review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2018; 8:98. doi: 10.3390/bs8110098

23. Shanafelt TD, Sloan JA, Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513-519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7

24. Drummond D. Physician burnout: its origin, symptoms, and five main causes. Fam Pract Manag. 2015;22:42-47.

25. Brown PA, Slater M, Lofters A. Personality and burnout among primary care physicians: an international study. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:169-177. doi: 10.2147/PRBM.S195633.

26. John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL. The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4A and 54. Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California; 1991.

27. Wurm W, Vogel K, Holl A, et al. Depression-burnout overlap in physicians. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0149913. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0149913

28. Mehta SS, Edwards ML. Suffering in silence: Mental health stigma and physicians’ licensing fears. Am J Psychiatry Resid J. 2018;13:2-4.

29. Adam AR, Golu FT. Prevalence of depression among physicians: A comprehensive meta-analysis. Ro Med J. 2021;68:327-337. doi: 10.37897/RMJ.2021.3.1

30. Brady KJS, Trockel MT, Khan CT, et al. What do we mean by physician wellness? A systematic review of its definition and measurement. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:94-108. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0781-6

31. Shanafelt TD, Schein E, Minor LB, et al. Healing the professional culture of medicine. Mayo Clin Proc. 2019;94:1556-1566. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.03.026

32. Horan S, Flaxman PE, Stride CB. The perfect recovery? Interactive influence of perfectionism and spillover work tasks on changes in exhaustion and mood around a vacation. J Occup Health Psychol. 2021;26:86-107. doi: 10.1037/ocp0000208

33. Patel RS, Sekhri S, Bhimanadham NN, et al. A review on strategies to manage physician burnout. Cureus. 2019;11:e4805. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4805

34. US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. US Department of Health and Human Services; 2018.

35. Kim ES, Chen Y, Nakamura JS, et al. Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: an outcome-wide approach. Am J Health Promot. 2022;36:137-147. doi: 10.1177/08901171211038545

36. Ogilvie RP, Patel SR. The epidemiology of sleep and obesity. Sleep Health. 2017;3:383-388. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2017.07.013

37. Fordham B, Sugavanam T, Edwards K, et al. The evidence for cognitive behavioural therapy in any condition, population or context: a meta-review of systematic reviews and panoramic meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:21-29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720005292

38. Goldberg SB, Tucker RP, Greene PA, et al. Mindfulness-based interventions for psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;59:52-60. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.011

39. David D, Cristea I, Hofmann SG. Why cognitive behavioral therapy is the current gold standard of psychotherapy. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:4. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00004

40. Fendel JC, Bürkle JJ, Göritz AS. Mindfulness-based interventions to reduce burnout and stress in physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2021;96:751-764. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003936

41. Dahl CJ, Wilson-Mendenhall CD, Davidson RJ. The plasticity of well-being: a training-based framework for the cultivation of human flourishing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:32197-32206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2014859117

42. Holt-Lunstad J. Why social relationships are important for physical health: a systems approach to understanding and modifying risk and protection. Annu Rev Psychol. 2018;69:437-458. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011902

43. Desai SV, Asch DA, Bellini LM, et al. Education outcomes in a duty-hour flexibility trial in internal medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018; 378:1494-1508. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1800965

44. Shea JA, Bellini LM, Dinges DF, et al. Impact of protected sleep period for internal medicine interns on overnight call on depression, burnout, and empathy. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6:256-263. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-13-00241.1

45. Morrow G, Burford B, Carter M, et al. Have restricted working hours reduced junior doctors’ experience of fatigue? A focus group and telephone interview study. BMJ Open. 2014;4:e004222. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004222

46. Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:129-146. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004

47. Sequeira L, Almilaji K, Strudwick G, et al. EHR “SWAT” teams: a physician engagement initiative to improve Electronic Health Record (EHR) experiences and mitigate possible causes of EHR-related burnout. JAMA Open. 2021;4:1-7. doi: 10.1093/jamiaopen/ooab018