User login

CAPO Aspiration Pneumonia

Pneumonia is a common clinical syndrome with well‐described epidemiology and microbiology. Aspiration pneumonia comprises 5% to 15% of patients with pneumonia acquired outside of the hospital,[1] but is less well characterized despite being a major syndrome of pneumonia in the elderly.[2, 3] Difficulties in studying aspiration pneumonia include the lack of a sensitive and specific marker for aspiration as well as the potential overlap between aspiration pneumonia and other forms of pneumonia.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, clinicians have difficulty distinguishing between aspiration pneumonia, which develops after the aspiration of oropharyngeal contents, and aspiration pneumonitis, wherein inhalation of gastric contents causes inflammation without the subsequent development of bacterial infection.[7, 8] Central to the study of aspiration pneumonia is whether it should exist as its own entity, or if aspiration is really a designation used for pneumonia in an older patient with greater comorbidities. The ability to clearly understand how a clinician diagnoses aspiration pneumonia, and whether that method has face validity with expert definitions may allow for improved future research, improved generalizability of current or past research, and possibly better clinical care.

Several validated mortality prediction models exist for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) using a variety of clinical predictors, but their performance in patients with aspiration pneumonia is less well characterized. Most studies validating pneumonia severity scoring systems excluded aspiration pneumonia from their study population.[9, 10, 11] Severity scoring systems for CAP may not accurately predict disease severity in patients with aspiration pneumonia. The CURB‐65[9] (confusion, uremia, respiratory rate, blood pressure, age 65 years) and the eCURB[12] scoring systems are poor predictors of mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia, perhaps because they do not account for patient comorbidities.[13] The pneumonia severity index (PSI)[10] might predict mortality better than CURB‐65 in the aspiration population due to the inclusion of comorbidities.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with aspiration pneumonia are older and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities.[13, 14, 15] These single‐center studies also demonstrated greater mortality, more frequent admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and longer hospital lengths of stay in patients with aspiration pneumonia. These studies identified aspiration pneumonia by the presence of a risk factor for aspiration[15] or by physician billing codes.[13] In practice, however, the bedside clinician diagnoses a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, but the logic is likely vague and inconsistent. Despite the potential for variability with individual judgment, an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may perform better than individual judgments.[16] Because there is no gold standard for defining aspiration pneumonia, all previous research has been limited to definitions created by investigators. This multicenter study seeks to determine what clinical characteristics lead physicians to diagnose a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, and whether or not the clinician‐derived diagnosis is distinct and clinically useful.

Our objectives were to: (1) identify covariates associated with bedside clinicians diagnosing a pneumonia patient as having aspiration pneumonia; (2) compare aspiration pneumonia and nonaspiration pneumonia in regard to disease severity, patient demographics, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes; and (3) measure the performance of the PSI in aspiration pneumonia versus nonaspiration pneumonia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We performed a secondary analysis of the Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) database, which contains retrospectively collected data from 71 hospitals in 16 countries between June 2001 and December 2012. In each participating center, primary investigators selected nonconsecutive, adult hospitalized patients diagnosed with CAP. To decrease systematic selection biases, the selection of patients with CAP for enrollment in the trial was based on the date of hospital admission. Each investigator completed a case report form that was transferred via the internet to the CAPO study center at the University of Louisville (Louisville, KY). A sample of the data collection form is available at the study website (

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients 18 years of age and satisfying criteria for CAP were included in this study. A diagnosis of CAP required a new pulmonary infiltrate at time of hospitalization, and at least 1 of the following: new or increased cough; leukocytosis; leukopenia, or left shift pattern on white blood cell count; and temperature >37.8C or <35.6 C. We excluded patients with pneumonia attributed to mycobacterial or fungal infection, and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus, as we believed these types of pneumonia differ fundamentally from typical CAP.

Patient Variables

Patient variables included presence of aspiration pneumonia, laboratory data, comorbidities, and measures of disease severity, including the PSI. The clinician made a clinical diagnosis of the presence or absence of aspiration for each patient by marking a box on the case report form. Outcomes included in‐hospital mortality, hospital length of stay up to 14 days, and time to clinical stability up to 8 days. All variables were obtained directly from the case report form. In accordance with previously published definitions, we defined clinical stability as the day the following criteria were all met: improved clinical signs (improved cough and shortness of breath), lack of fever for >8 hours, improving leukocytosis (decreased at least 10% from the previous day), and tolerating oral intake.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients with aspiration and nonaspiration CAP were compared using 2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and the Mann‐Whitney U test for continuous variables.

To determine which patient variables were important in the physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, we performed logistic regression with initial covariates comprising the demographic, comorbidity, and disease severity measurements listed in Table 1. We included interactions between cerebrovascular disease and age, nursing home status, and confusion to improve model fit. We centered all variables (including binary indicators) according to the method outlined by Kraemer and Blasey to improve interpretation of the main effects.[19]

| Aspiration Pneumonia, N=451 | Nonaspiration Pneumonia, N=4,734 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 79 (6587) | 69 (5380) | <0.001 |

| % Male | 59% | 60% | 0.58 |

| Nursing home residence | 25% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Recent (30 days) antibiotic use | 21% | 16% | 0.017 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 35% | 14% | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25% | 27% | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23% | 19% | 0.027 |

| Diabetes | 18% | 18% | 0.85 |

| Cancer | 12% | 10% | 0.12 |

| Renal disease | 10% | 11% | 0.53 |

| Liver disease | 6% | 5% | 0.29 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Pneumonia severity index | 123 (99153) | 92 (68117) | <0.001 |

| Confusion | 49% | 12% | <0.001 |

| PaO2 <60 mm Hg | 43% | 33% | <0.001 |

| BUN >30 g/dL | 42% | 23% | <0.001 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 34% | 28% | 0.003 |

| Pleural effusion | 25% | 21% | 0.07 |

| Respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute | 21% | 20% | 0.95 |

| pH <7.35 | 13% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 11% | 6% | 0.001 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 9% | 7% | 0.30 |

| Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg | 8% | 9% | 0.003 |

| Sodium <130 mEq/L | 8% | 6% | 0.08 |

| Heart rate >125 beats/minute | 8% | 5% | 0.71 |

| Glucose >250 mg/dL | 6% | 7% | 0.06 |

| Cavitary lesion | 0% | 0% | 0.67 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| In‐hospital mortality | 23% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 19% | 13% | 0.002 |

| Hospital length of stay, d | 9 (515) | 7 (412) | <0.001 |

| Time to clinical stability, d | 8 (48) | 4 (38) | <0.001 |

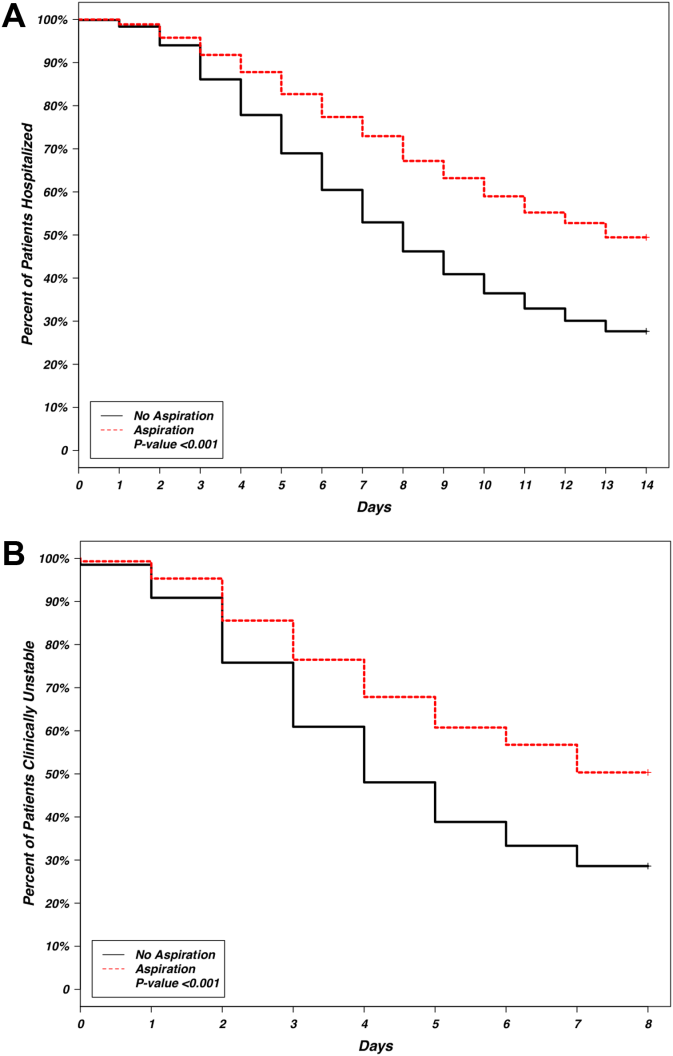

To determine if aspiration pneumonia had worse clinical outcomes compared to nonaspiration pneumonia, multiple methods were used. To compare the differences between the 2 groups with respect to time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay, we constructed Kaplan‐Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards regression models. The log‐rank test was used to determine statistical differences between the Kaplan‐Meier survival curves. To compare the impact of aspiration on mortality in patients with CAP, we conducted a propensity scorematched analysis. We chose propensity score matching over traditional logistic regression to balance variables among groups and to avoid the potential for overfit and multicollinearity. We considered a variable balanced after matching if its standardized difference was <10. All variables in the propensity scorematched analysis were balanced.

Although our dataset contained minimal missing data, we imputed any missing values to maintain the full study population in the creation of the propensity score. Missing data were imputed using the aregImpute function of the hmisc package of R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).[20, 21] We built the propensity score model using a variable selection algorithm described by Bursac et al.[22] Our model included variables for region (United States/Canada, Europe, Asia/Africa or Latin America) and the variables listed in Table 1, with the exception of the PSI and the 4 clinical outcomes. Given that previous analyses accounting for clustering by physician did not substantially affect our results,[23] our model did not include physician‐level variables and did not account for the clustering effects of physicians. Using the propensity scores generated from this model, we matched a case of aspiration CAP with a case of nonaspiration CAP.[24] We then constructed a general linear model using the matched dataset to obtain the magnitude of effect of aspiration on mortality.

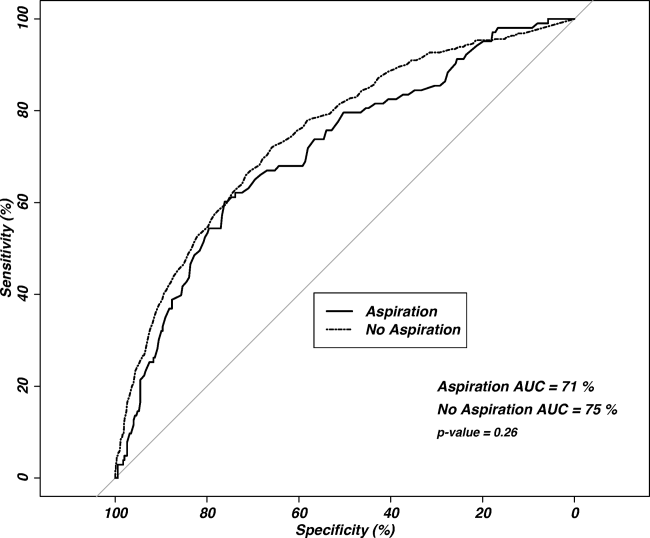

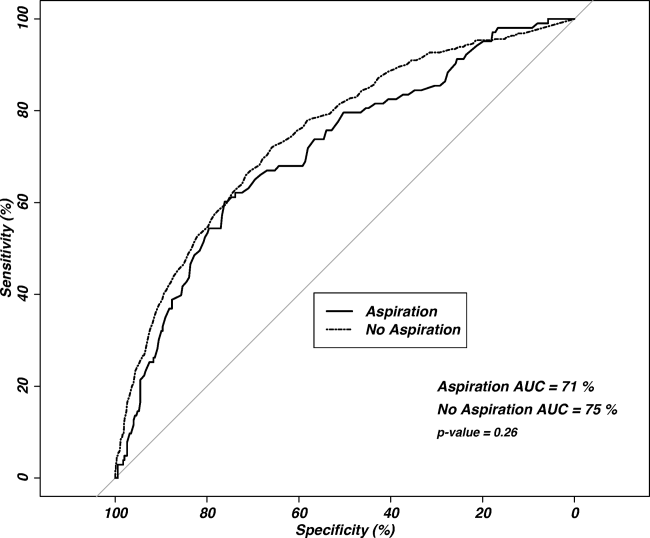

We used receiver operating characteristic curves to define the diagnostic accuracy of the pneumonia severity index for the prediction of mortality among patients with aspiration pneumonia and those with nonaspiration pneumonia. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 2.15.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used for all analyses. P values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

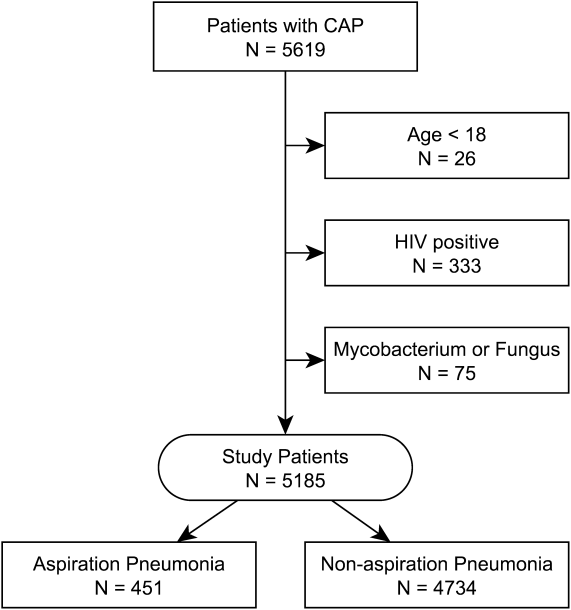

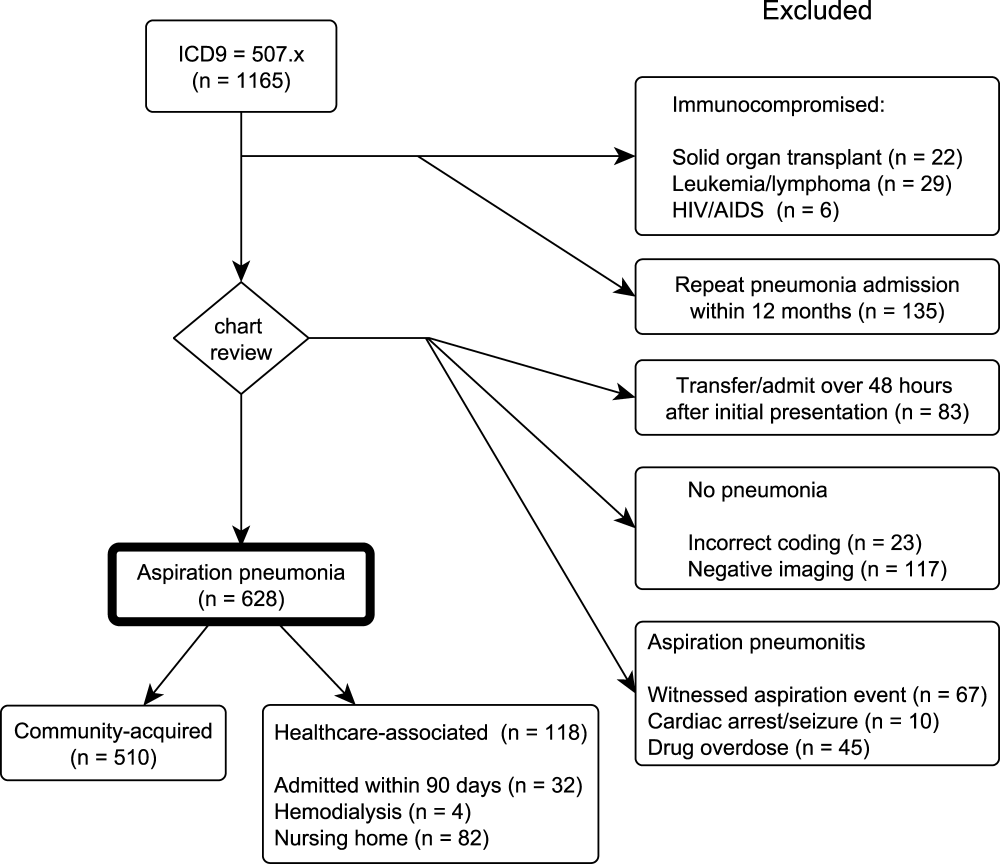

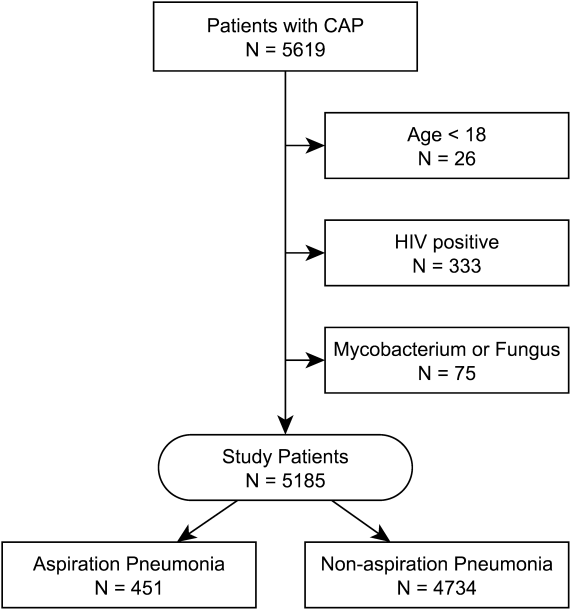

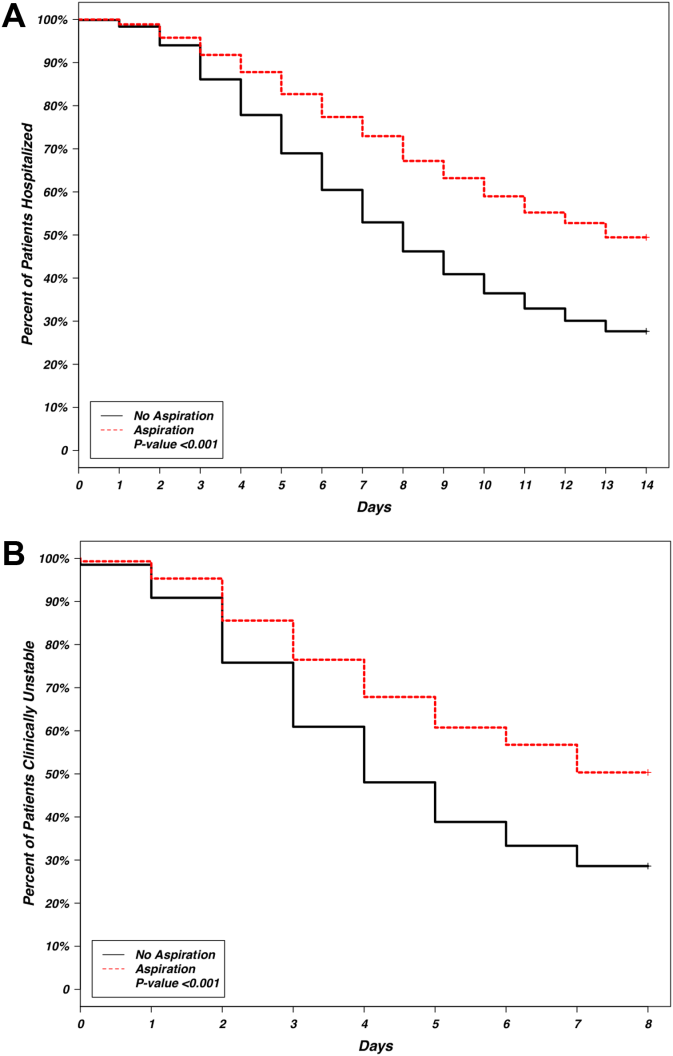

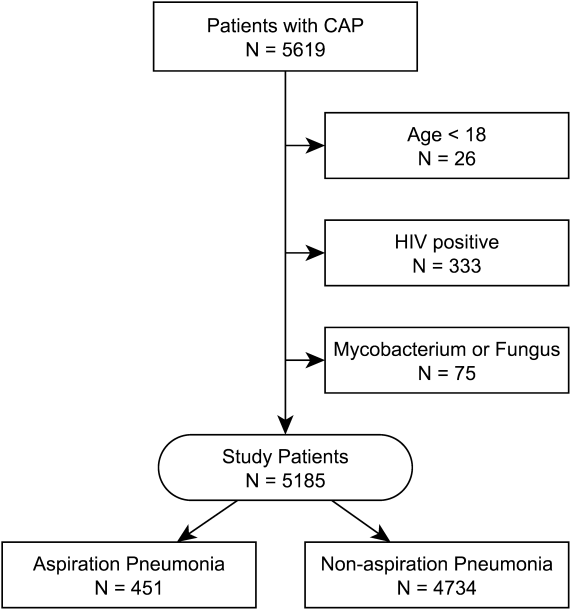

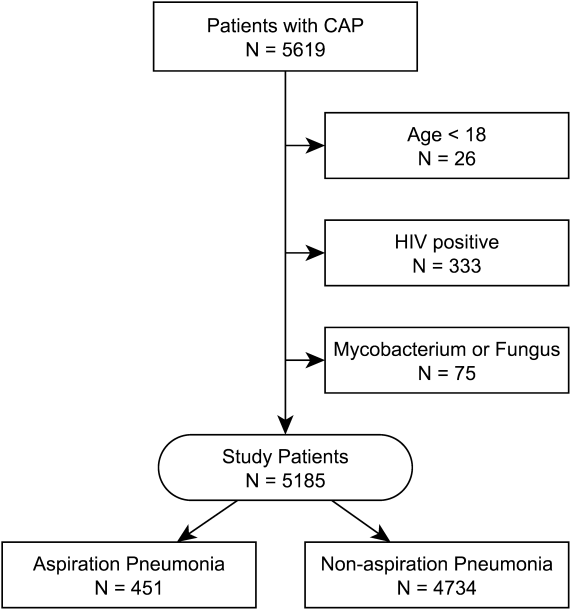

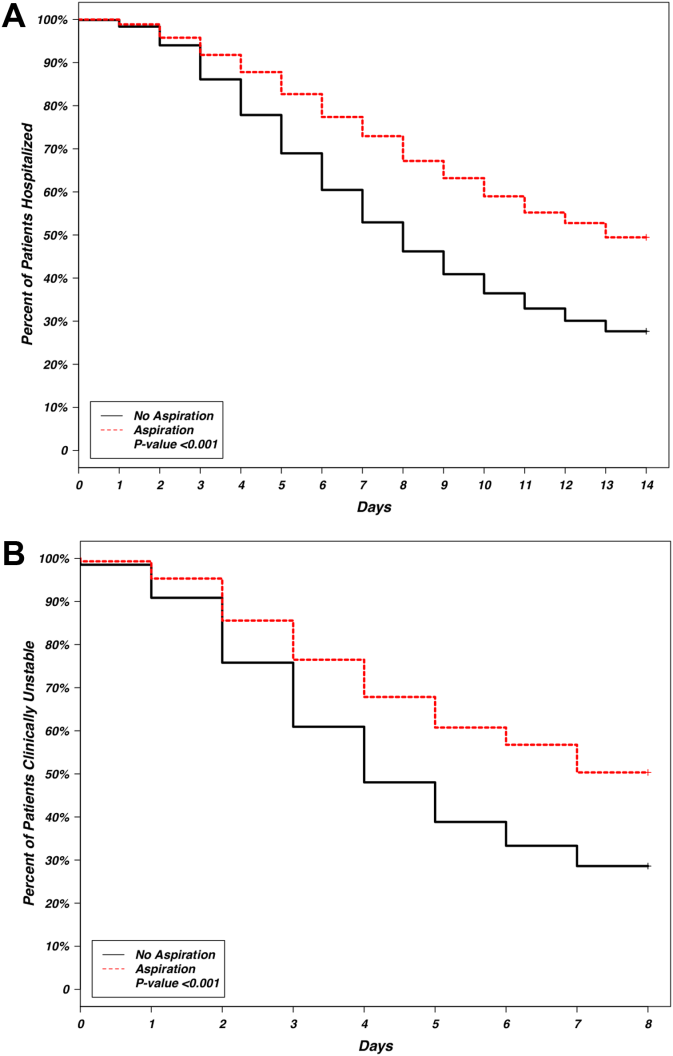

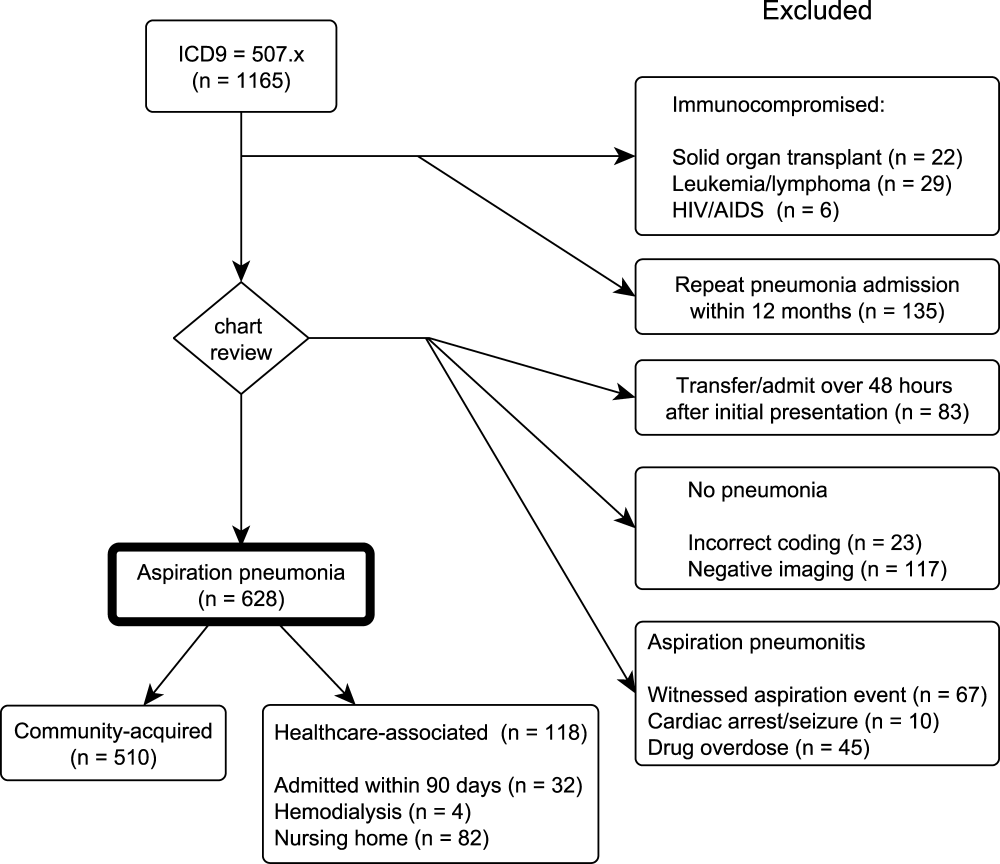

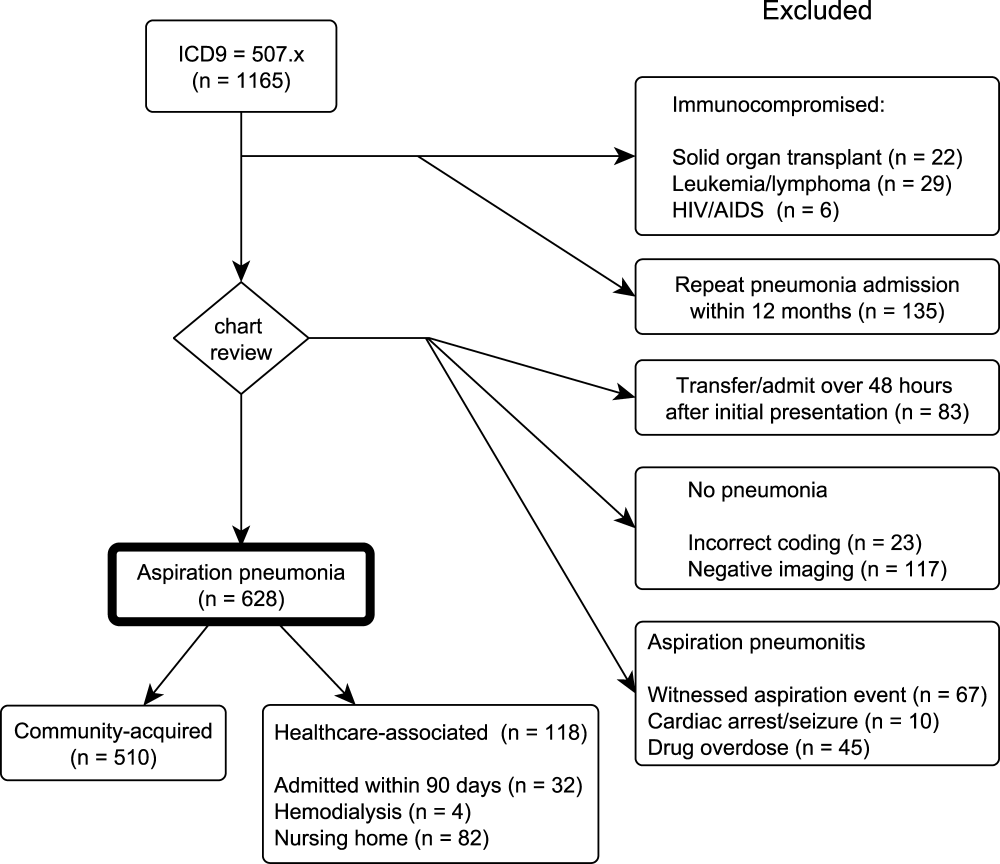

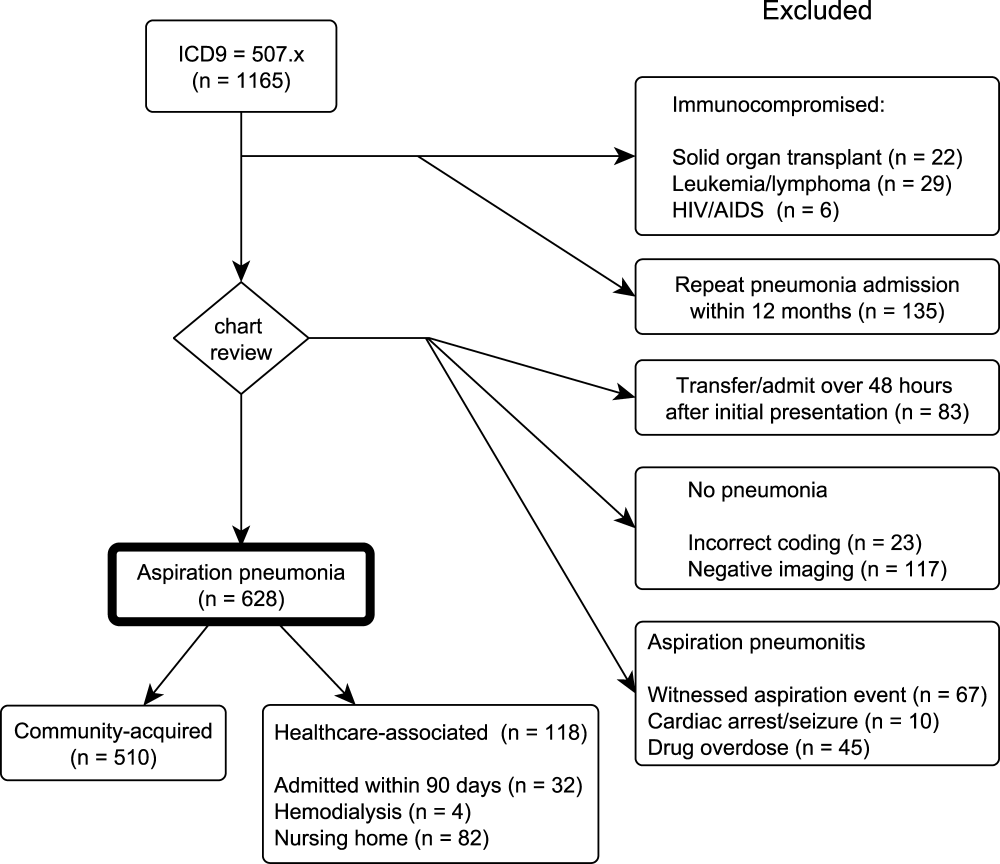

Our initial query, after exclusion criteria, yielded a study population of 5185 patients (Figure 1). We compared 451 patients diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia to 4734 with CAP (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were older, more likely to live in a nursing home, had greater disease severity, and were more likely to be admitted to an ICU. Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer adjusted hospital lengths of stay and took more days to achieve clinical stability than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (Figure 2). After adjusting for all variables in Table 1, the Cox proportional hazards models demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia was associated with ongoing hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR] for discharge: 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.65‐0.91, P=0.002) and clinical instability (HR for attaining clinical stability: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.61‐0.84, P<0.001). Patients with aspiration pneumonia presented with greater disease severity than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Although there was no difference between groups in regard to temperature, respiratory rate, hyponatremia, or presence of pleural effusions or cavitary lesions, all other measured indices of disease severity were worse in patients with aspiration pneumonia. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were more likely to have cerebrovascular disease than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia patients also had increased prevalence of congestive heart failure. There was no appreciable difference between groups among other measured comorbidities.

The patient characteristics most associated with a physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, identified using logistic regression, were confusion, residence in nursing home, and presence of cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio [OR]: of 4.4, 2.9, and 2.3, respectively), whereas renal disease was associated with decreased physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia over nonaspiration pneumonia (OR: 0.58) (Table 2).

| Covariate | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 1.00 | 0.991.01 | 0.948 |

| Male | 1.20 | 0.941.54 | 0.148 |

| Nursing home residence | 2.93 | 2.134.00 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.26 | 1.533.32 | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 0.58 | 0.390.85 | 0.006 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Confusion | 4.41 | 3.405.72 | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 1.59 | 1.062.33 | 0.020 |

| pH <7.35 | 1.67 | 1.102.47 | 0.013 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 1.60 | 1.072.35 | 0.019 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 1.29 | 1.001.65 | 0.047 |

| Interaction terms | |||

| Age * cerebrovascular disease | 0.98 | 0.960.99 | 0.011 |

| Nursing home * cerebrovascular disease | 0.51 | 0.270.96 | 0.037 |

| Confusion * cerebrovascular disease | 0.70 | 0.421.17 | 0.175 |

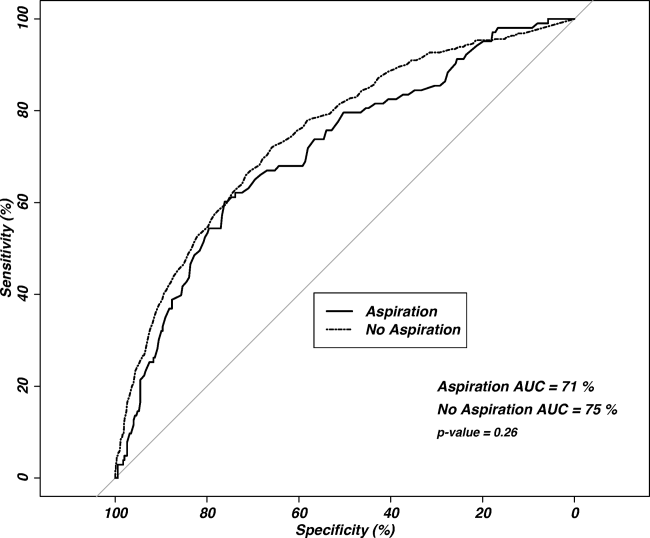

Observed in‐patient mortality of aspiration pneumonia was 23%. This mortality was considerably higher than a mean PSI score of 123 would predict (class IV risk group, with expected 30‐day mortality of 8%9%[25]). The PSI score's ability to predict inpatient mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia was moderate, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.71. This was similar to its performance in patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (AUC of 0.75) (Figure 3). These values are lower than the AUC of 0.81 for the PSI in predicting mortality derived from a meta‐analysis of 31 other studies.[26]

Our regression model after propensity score matching demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia independently confers a 2.3‐fold increased odds for inpatient mortality (95% CI: 1.56‐3.45, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, nursing home residence, or cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Although this is unsurprising, it is notable that these patients are more than twice as likely to die in the inpatient setting, even after accounting for age, comorbidities, and disease severity. These findings are similar to three previously published studies comparing aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia at single institutions, albeit using different aspiration pneumonia definitions.[13, 14, 15] This study is the first large, multicenter, multinational study to demonstrate these findings.

Central to the interpretation of our results is the method of diagnosing aspiration versus nonaspiration. A bottom‐up method that relies on a clinician to check a box for aspiration may appear poorly reproducible. Because there is no diagnostic gold standard, clinicians may use different criteria to diagnose aspiration, creating potential for idiosyncratic noise. The strength of the wisdom of the crowd method used in this study is that an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may reduce the noise from individual judgments.[16] Although clinicians may vary in why they diagnose a particular patient as having aspiration pneumonia, it appears that the overwhelming reason for diagnosing a patient as having aspiration pneumonia is the presence of confusion, followed by previous nursing home residence or cerebrovascular disease. This finding has some face validity when compared with studies using an investigator definition, as altered mental status, chronic debility, and cerebrovascular disease are either prominent features of the definition of aspiration pneumonia[8] or frequently observed in patients with aspiration pneumonia.[13, 15] The distribution of cerebrovascular disease among our study's aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia patients was similar to studies that used formal criteria in their definitions.[13, 15] Although nursing home residence was more likely in aspiration pneumonia patients, the majority of aspiration pneumonia patients were residing in the community, suggesting that aspiration is not simply a surrogate for healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Although patients with aspiration pneumonia are typically older than their nonaspiration counterparts, it appears that age is not a key determinant in the diagnosis of aspiration. With aspiration pneumonia, confusion, nursing home residence, and the presence of cerebrovascular disease are the greatest contributors in the clinical diagnosis, more than age.

Our data demonstrate that aspiration pneumonia confers increased odds for mortality, even after adjustment for age, disease severity, and comorbidities. These data suggest that aspiration pneumonia is a distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia, and that this disease is worse than nonaspiration CAP. If aspiration pneumonia is distinct from nonaspiration pneumonia, some unrecognized host factor other than age, disease severity, or the captured comorbidities decreases survival in aspiration pneumonia patients. However, it is also possible that aspiration pneumonia is merely a clinical designation for one end of the pneumonia spectrum, and we and others have failed to completely account for all measures of disease severity or all measures of comorbidities. Examples of unmeasured comorbidities would include presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, which is not assessed in the database but could have a significant effect on clinical diagnosis. Unmeasured covariates can include measures beyond that of disease severity or comorbidity, such as the presence of a do not resuscitate (DNR) order, which could have a significant confounding effect on the observed association. A previous, single‐center study demonstrated that increased 30‐day mortality in aspiration pneumonia was mostly attributable to greater disease severity and comorbidities, although aspiration pneumonia independently conferred greater risk for adverse long‐term outcomes.[15] We propose that aspiration pneumonia represents a clinically distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia. Patients with chronic aspiration are often chronically malnourished and may have different oral flora than patients without chronic aspiration.[27, 28] Chronic aspiration has been associated with granulomatous reaction, organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, and chronic bronchiolitis.[29] Chronic aspiration may elicit changes in the host physiology, and may render the host more susceptible to the development of secondary bacterial infection with morbid consequences.

The ability of the PSI to predict inpatient mortality was moderate (AUC only 0.7), with no significant additional discrimination between the aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia groups. Although the PSI had moderate ability to predict inpatient mortality, the observed mortality was considerably higher than predicted. It is possible that the PSI incompletely captures clinically relevant comorbidities (eg, malnutrition). Further study to improve mortality prediction of aspiration pneumonia patients could employ sensitivity analysis to determine optimal thresholds and weighting of the PSI components.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer hospital lengths of stay and took longer to achieve clinical stability than their nonaspiration counterparts. Time to clinical stability has been associated with increased posthospitalization mortality and is associated with time to switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics.[17] Although some component of hospital length‐of‐stay is subject to local practice patterns, time to clinical stability has explicit criteria for clinical improvement and failure, and therefore is less likely to be affected by local practice patterns.

We noted a relatively high (16%21%) incidence of prior antibiotic use among patients in this database. Analysis of antibiotic prescription patterns was limited, given the several different countries from which the database draws its cases. Although we used accepted criteria to define CAP cases, it is possible that this population may have a higher rate of resistant or uncommon pathogens than other studies of CAP that have populations with lower incidence of prior antibiotic use. Although not assessed, we suspect a significant component of the prior antibiotic use represented outpatient pneumonia treatment during the few days prior to visiting the hospital.

This study has several limitations, of which the most important may be that we used clinical determination for defining presence of aspiration pneumonia. This method is susceptible to the subjective perceptions of the treating clinician. We did not account for the effect of individual physicians in our model, although we did adjust for regional differences. The retrospective identification of patients allows for the possibility of selection bias, and therefore we have not attempted to make inferences regarding the relative incidence of pneumonia, nor did we adjust for temporal trends in diagnosis. The ratio of aspiration pneumonia patients to nonaspiration pneumonia patients may not necessarily reflect that observed in reality. Microbiologic and antibiotic data were unavailable for analysis. This study cannot inform on nonhospitalized patients with aspiration pneumonia, as only hospitalized patients were enrolled. The database identified cases of pneumonia, so it is possible for a patient to enter into the database more than once. Detection of mortality was limited to the inpatient setting rather than a set interval of 30 days. Inpatient mortality depends on length‐of‐stay patterns that may bias the mortality endpoint.[30] Also not assessed was the presence of a DNR order. It is possible that an older patient with greater comorbidities and disease severity may have care intentionally limited or withdrawn early by the family or clinicians.

Strengths of the study include its size and its multicenter, multinational population. The CAPO database is a large and well‐described population of patients with CAP.[17, 31] These attributes, as well as the clinician‐determined diagnosis, increase the generalizability of the study compared to a single‐center, single‐country study that employs investigator‐defined criteria.

CONCLUSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, who are nursing home residence, and have cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Our clinician‐diagnosed cohort appears similar to those derived using an investigator definition. Patients with aspiration pneumonia are older, and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia. They have greater mortality than their PSI score class would predict. Even after accounting for age, disease severity, and comorbidities, the presence of aspiration pneumonia independently conferred a greater than 2‐fold increase in inpatient mortality. These findings together suggest that aspiration pneumonia should be considered a distinct entity from typical pneumonia, and that additional research should be done in this field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.J.L. contributed to the study design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript. P.P. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. T.W. and E.W. contributed to the study design, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.A.R. and N.C.D. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.L. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. This investigation was partly supported with funding from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant 8UL1TR000105 [formerly UL1RR025764]). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Epidemiology and prognostic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(2):312–318.

- , , . Risk factors for pneumonia in the elderly. Am J Med. 1994;96(4):313–320.

- , . Aspiration pneumonia and dysphagia in the elderly. Chest. 2003;124(1):328–336.

- , , . Pneumonia versus aspiration pneumonitis in nursing home residents: diagnosis and management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):17–23.

- . Aspiration pneumonia: mixing apples with oranges and tangerines. Crit Care Med. 2004;32(5):1236; author reply 1236–1237.

- , , , , . Epidemiology and impact of aspiration pneumonia in patients undergoing surgery in Maryland, 1999–2000. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(7):1930–1937.

- . Aspiration syndromes: aspiration pneumonia and pneumonitis. Hosp Pract (Minneap). 2010;38(1):35–42.

- . Aspiration pneumonitis and aspiration pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(9):665–671.

- , , , et al. Defining community acquired pneumonia severity on presentation to hospital: an international derivation and validation study. Thorax. 2003;58(5):377–382.

- , , , et al. Comparison of a disease‐specific and a generic severity of illness measure for patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(7):359–368.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a clinical prediction rule for severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;174(11):1249–1256.

- , , , et al. CURB‐65 pneumonia severity assessment adapted for electronic decision support. Chest. 2011;140(1):156–163.

- , , , . Mortality, morbidity, and disease severity of patients with aspiration pneumonia. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):83–90.

- , , , , . Pneumonia Severity Index (PSI), CURB‐65, and mortality in hospitalized elderly patients with aspiration pneumonia [in German]. Z Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;44(4):229–234.

- , , , , . Risk factors for aspiration in community‐acquired pneumonia: analysis of a hospitalized UK cohort. Am J Med. 2013;126(11):995–1001.

- , , , . The wisdom of the crowd in combinatorial problems. Cogn Sci. 2012;36(3):452–470.

- , , , et al. Association between time to clinical stability and outcomes after discharge in hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Chest. 2011;140(2):482–488.

- . Clinical stability and switch therapy in hospitalised patients with community‐acquired pneumonia: are we there yet? Eur Respir J. 2013;41(1):5–6.

- , . Centring in regression analyses: a strategy to prevent errors in statistical inference. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13(3):141–151.

- . Hmisc: Harrell miscellaneous. Available at: http://CRAN.R‐project.org/package=Hmisc. Published Sept 12, 2014. Last accessed Oct 27, 2014.

- , . Multiple imputation for the fatal accident reporting system. J R Stat Soc Ser C Appl Stat. 1991;40(1):13–29.

- , , , . Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17.

- , , , , ; CAPO authors. Mortality differences among hospitalized patients with community‐acquired pneumonia in three world regions: results from the Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) International Cohort Study. Respir Med. 2013;107(7):1101–1111.

- . Reducing bias in a propensity score matched‐pair sample using greedy matching techniques. In: Proceedings of the 26th Annual SAS Users Group International Conference. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2001:214–226. Available at: http://www2.sas.com/proceedings/sugi26/p214–26.pdf. Last accessed Oct 27, 2014.

- , , , et al. A prediction rule to identify low‐risk patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1997;336(4):243–250.

- , , , et al. Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community‐acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta‐analysis. Thorax. 2010;65(10):878–883.

- , , , , , . Prevalence and prognostic implications of dysphagia in elderly patients with pneumonia. Age Ageing. 2010;39(1):39–45.

- , . The association between oral microorgansims and aspiration pneumonia in the institutionalized elderly: review and recommendations. Dysphagia. 2010;25(4):307–322.

- , . Histopathology of aspiration pneumonia not associated with food or other particulate matter: a clinicopathologic study of 10 cases diagnosed on biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(3):426–431.

- , , , , , . Interpreting hospital mortality data. The role of clinical risk adjustment. JAMA. 1988;260(24):3611–3616.

- , , , . Hospitalization for community‐acquired pneumonia: the pneumonia severity index vs clinical judgment. Chest. 2003;124(1):121–124.

Pneumonia is a common clinical syndrome with well‐described epidemiology and microbiology. Aspiration pneumonia comprises 5% to 15% of patients with pneumonia acquired outside of the hospital,[1] but is less well characterized despite being a major syndrome of pneumonia in the elderly.[2, 3] Difficulties in studying aspiration pneumonia include the lack of a sensitive and specific marker for aspiration as well as the potential overlap between aspiration pneumonia and other forms of pneumonia.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, clinicians have difficulty distinguishing between aspiration pneumonia, which develops after the aspiration of oropharyngeal contents, and aspiration pneumonitis, wherein inhalation of gastric contents causes inflammation without the subsequent development of bacterial infection.[7, 8] Central to the study of aspiration pneumonia is whether it should exist as its own entity, or if aspiration is really a designation used for pneumonia in an older patient with greater comorbidities. The ability to clearly understand how a clinician diagnoses aspiration pneumonia, and whether that method has face validity with expert definitions may allow for improved future research, improved generalizability of current or past research, and possibly better clinical care.

Several validated mortality prediction models exist for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) using a variety of clinical predictors, but their performance in patients with aspiration pneumonia is less well characterized. Most studies validating pneumonia severity scoring systems excluded aspiration pneumonia from their study population.[9, 10, 11] Severity scoring systems for CAP may not accurately predict disease severity in patients with aspiration pneumonia. The CURB‐65[9] (confusion, uremia, respiratory rate, blood pressure, age 65 years) and the eCURB[12] scoring systems are poor predictors of mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia, perhaps because they do not account for patient comorbidities.[13] The pneumonia severity index (PSI)[10] might predict mortality better than CURB‐65 in the aspiration population due to the inclusion of comorbidities.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with aspiration pneumonia are older and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities.[13, 14, 15] These single‐center studies also demonstrated greater mortality, more frequent admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and longer hospital lengths of stay in patients with aspiration pneumonia. These studies identified aspiration pneumonia by the presence of a risk factor for aspiration[15] or by physician billing codes.[13] In practice, however, the bedside clinician diagnoses a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, but the logic is likely vague and inconsistent. Despite the potential for variability with individual judgment, an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may perform better than individual judgments.[16] Because there is no gold standard for defining aspiration pneumonia, all previous research has been limited to definitions created by investigators. This multicenter study seeks to determine what clinical characteristics lead physicians to diagnose a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, and whether or not the clinician‐derived diagnosis is distinct and clinically useful.

Our objectives were to: (1) identify covariates associated with bedside clinicians diagnosing a pneumonia patient as having aspiration pneumonia; (2) compare aspiration pneumonia and nonaspiration pneumonia in regard to disease severity, patient demographics, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes; and (3) measure the performance of the PSI in aspiration pneumonia versus nonaspiration pneumonia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We performed a secondary analysis of the Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) database, which contains retrospectively collected data from 71 hospitals in 16 countries between June 2001 and December 2012. In each participating center, primary investigators selected nonconsecutive, adult hospitalized patients diagnosed with CAP. To decrease systematic selection biases, the selection of patients with CAP for enrollment in the trial was based on the date of hospital admission. Each investigator completed a case report form that was transferred via the internet to the CAPO study center at the University of Louisville (Louisville, KY). A sample of the data collection form is available at the study website (

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients 18 years of age and satisfying criteria for CAP were included in this study. A diagnosis of CAP required a new pulmonary infiltrate at time of hospitalization, and at least 1 of the following: new or increased cough; leukocytosis; leukopenia, or left shift pattern on white blood cell count; and temperature >37.8C or <35.6 C. We excluded patients with pneumonia attributed to mycobacterial or fungal infection, and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus, as we believed these types of pneumonia differ fundamentally from typical CAP.

Patient Variables

Patient variables included presence of aspiration pneumonia, laboratory data, comorbidities, and measures of disease severity, including the PSI. The clinician made a clinical diagnosis of the presence or absence of aspiration for each patient by marking a box on the case report form. Outcomes included in‐hospital mortality, hospital length of stay up to 14 days, and time to clinical stability up to 8 days. All variables were obtained directly from the case report form. In accordance with previously published definitions, we defined clinical stability as the day the following criteria were all met: improved clinical signs (improved cough and shortness of breath), lack of fever for >8 hours, improving leukocytosis (decreased at least 10% from the previous day), and tolerating oral intake.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients with aspiration and nonaspiration CAP were compared using 2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and the Mann‐Whitney U test for continuous variables.

To determine which patient variables were important in the physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, we performed logistic regression with initial covariates comprising the demographic, comorbidity, and disease severity measurements listed in Table 1. We included interactions between cerebrovascular disease and age, nursing home status, and confusion to improve model fit. We centered all variables (including binary indicators) according to the method outlined by Kraemer and Blasey to improve interpretation of the main effects.[19]

| Aspiration Pneumonia, N=451 | Nonaspiration Pneumonia, N=4,734 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 79 (6587) | 69 (5380) | <0.001 |

| % Male | 59% | 60% | 0.58 |

| Nursing home residence | 25% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Recent (30 days) antibiotic use | 21% | 16% | 0.017 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 35% | 14% | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25% | 27% | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23% | 19% | 0.027 |

| Diabetes | 18% | 18% | 0.85 |

| Cancer | 12% | 10% | 0.12 |

| Renal disease | 10% | 11% | 0.53 |

| Liver disease | 6% | 5% | 0.29 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Pneumonia severity index | 123 (99153) | 92 (68117) | <0.001 |

| Confusion | 49% | 12% | <0.001 |

| PaO2 <60 mm Hg | 43% | 33% | <0.001 |

| BUN >30 g/dL | 42% | 23% | <0.001 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 34% | 28% | 0.003 |

| Pleural effusion | 25% | 21% | 0.07 |

| Respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute | 21% | 20% | 0.95 |

| pH <7.35 | 13% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 11% | 6% | 0.001 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 9% | 7% | 0.30 |

| Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg | 8% | 9% | 0.003 |

| Sodium <130 mEq/L | 8% | 6% | 0.08 |

| Heart rate >125 beats/minute | 8% | 5% | 0.71 |

| Glucose >250 mg/dL | 6% | 7% | 0.06 |

| Cavitary lesion | 0% | 0% | 0.67 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| In‐hospital mortality | 23% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 19% | 13% | 0.002 |

| Hospital length of stay, d | 9 (515) | 7 (412) | <0.001 |

| Time to clinical stability, d | 8 (48) | 4 (38) | <0.001 |

To determine if aspiration pneumonia had worse clinical outcomes compared to nonaspiration pneumonia, multiple methods were used. To compare the differences between the 2 groups with respect to time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay, we constructed Kaplan‐Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards regression models. The log‐rank test was used to determine statistical differences between the Kaplan‐Meier survival curves. To compare the impact of aspiration on mortality in patients with CAP, we conducted a propensity scorematched analysis. We chose propensity score matching over traditional logistic regression to balance variables among groups and to avoid the potential for overfit and multicollinearity. We considered a variable balanced after matching if its standardized difference was <10. All variables in the propensity scorematched analysis were balanced.

Although our dataset contained minimal missing data, we imputed any missing values to maintain the full study population in the creation of the propensity score. Missing data were imputed using the aregImpute function of the hmisc package of R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).[20, 21] We built the propensity score model using a variable selection algorithm described by Bursac et al.[22] Our model included variables for region (United States/Canada, Europe, Asia/Africa or Latin America) and the variables listed in Table 1, with the exception of the PSI and the 4 clinical outcomes. Given that previous analyses accounting for clustering by physician did not substantially affect our results,[23] our model did not include physician‐level variables and did not account for the clustering effects of physicians. Using the propensity scores generated from this model, we matched a case of aspiration CAP with a case of nonaspiration CAP.[24] We then constructed a general linear model using the matched dataset to obtain the magnitude of effect of aspiration on mortality.

We used receiver operating characteristic curves to define the diagnostic accuracy of the pneumonia severity index for the prediction of mortality among patients with aspiration pneumonia and those with nonaspiration pneumonia. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 2.15.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used for all analyses. P values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

Our initial query, after exclusion criteria, yielded a study population of 5185 patients (Figure 1). We compared 451 patients diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia to 4734 with CAP (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were older, more likely to live in a nursing home, had greater disease severity, and were more likely to be admitted to an ICU. Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer adjusted hospital lengths of stay and took more days to achieve clinical stability than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (Figure 2). After adjusting for all variables in Table 1, the Cox proportional hazards models demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia was associated with ongoing hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR] for discharge: 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.65‐0.91, P=0.002) and clinical instability (HR for attaining clinical stability: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.61‐0.84, P<0.001). Patients with aspiration pneumonia presented with greater disease severity than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Although there was no difference between groups in regard to temperature, respiratory rate, hyponatremia, or presence of pleural effusions or cavitary lesions, all other measured indices of disease severity were worse in patients with aspiration pneumonia. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were more likely to have cerebrovascular disease than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia patients also had increased prevalence of congestive heart failure. There was no appreciable difference between groups among other measured comorbidities.

The patient characteristics most associated with a physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, identified using logistic regression, were confusion, residence in nursing home, and presence of cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio [OR]: of 4.4, 2.9, and 2.3, respectively), whereas renal disease was associated with decreased physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia over nonaspiration pneumonia (OR: 0.58) (Table 2).

| Covariate | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 1.00 | 0.991.01 | 0.948 |

| Male | 1.20 | 0.941.54 | 0.148 |

| Nursing home residence | 2.93 | 2.134.00 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.26 | 1.533.32 | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 0.58 | 0.390.85 | 0.006 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Confusion | 4.41 | 3.405.72 | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 1.59 | 1.062.33 | 0.020 |

| pH <7.35 | 1.67 | 1.102.47 | 0.013 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 1.60 | 1.072.35 | 0.019 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 1.29 | 1.001.65 | 0.047 |

| Interaction terms | |||

| Age * cerebrovascular disease | 0.98 | 0.960.99 | 0.011 |

| Nursing home * cerebrovascular disease | 0.51 | 0.270.96 | 0.037 |

| Confusion * cerebrovascular disease | 0.70 | 0.421.17 | 0.175 |

Observed in‐patient mortality of aspiration pneumonia was 23%. This mortality was considerably higher than a mean PSI score of 123 would predict (class IV risk group, with expected 30‐day mortality of 8%9%[25]). The PSI score's ability to predict inpatient mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia was moderate, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.71. This was similar to its performance in patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (AUC of 0.75) (Figure 3). These values are lower than the AUC of 0.81 for the PSI in predicting mortality derived from a meta‐analysis of 31 other studies.[26]

Our regression model after propensity score matching demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia independently confers a 2.3‐fold increased odds for inpatient mortality (95% CI: 1.56‐3.45, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, nursing home residence, or cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Although this is unsurprising, it is notable that these patients are more than twice as likely to die in the inpatient setting, even after accounting for age, comorbidities, and disease severity. These findings are similar to three previously published studies comparing aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia at single institutions, albeit using different aspiration pneumonia definitions.[13, 14, 15] This study is the first large, multicenter, multinational study to demonstrate these findings.

Central to the interpretation of our results is the method of diagnosing aspiration versus nonaspiration. A bottom‐up method that relies on a clinician to check a box for aspiration may appear poorly reproducible. Because there is no diagnostic gold standard, clinicians may use different criteria to diagnose aspiration, creating potential for idiosyncratic noise. The strength of the wisdom of the crowd method used in this study is that an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may reduce the noise from individual judgments.[16] Although clinicians may vary in why they diagnose a particular patient as having aspiration pneumonia, it appears that the overwhelming reason for diagnosing a patient as having aspiration pneumonia is the presence of confusion, followed by previous nursing home residence or cerebrovascular disease. This finding has some face validity when compared with studies using an investigator definition, as altered mental status, chronic debility, and cerebrovascular disease are either prominent features of the definition of aspiration pneumonia[8] or frequently observed in patients with aspiration pneumonia.[13, 15] The distribution of cerebrovascular disease among our study's aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia patients was similar to studies that used formal criteria in their definitions.[13, 15] Although nursing home residence was more likely in aspiration pneumonia patients, the majority of aspiration pneumonia patients were residing in the community, suggesting that aspiration is not simply a surrogate for healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Although patients with aspiration pneumonia are typically older than their nonaspiration counterparts, it appears that age is not a key determinant in the diagnosis of aspiration. With aspiration pneumonia, confusion, nursing home residence, and the presence of cerebrovascular disease are the greatest contributors in the clinical diagnosis, more than age.

Our data demonstrate that aspiration pneumonia confers increased odds for mortality, even after adjustment for age, disease severity, and comorbidities. These data suggest that aspiration pneumonia is a distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia, and that this disease is worse than nonaspiration CAP. If aspiration pneumonia is distinct from nonaspiration pneumonia, some unrecognized host factor other than age, disease severity, or the captured comorbidities decreases survival in aspiration pneumonia patients. However, it is also possible that aspiration pneumonia is merely a clinical designation for one end of the pneumonia spectrum, and we and others have failed to completely account for all measures of disease severity or all measures of comorbidities. Examples of unmeasured comorbidities would include presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, which is not assessed in the database but could have a significant effect on clinical diagnosis. Unmeasured covariates can include measures beyond that of disease severity or comorbidity, such as the presence of a do not resuscitate (DNR) order, which could have a significant confounding effect on the observed association. A previous, single‐center study demonstrated that increased 30‐day mortality in aspiration pneumonia was mostly attributable to greater disease severity and comorbidities, although aspiration pneumonia independently conferred greater risk for adverse long‐term outcomes.[15] We propose that aspiration pneumonia represents a clinically distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia. Patients with chronic aspiration are often chronically malnourished and may have different oral flora than patients without chronic aspiration.[27, 28] Chronic aspiration has been associated with granulomatous reaction, organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, and chronic bronchiolitis.[29] Chronic aspiration may elicit changes in the host physiology, and may render the host more susceptible to the development of secondary bacterial infection with morbid consequences.

The ability of the PSI to predict inpatient mortality was moderate (AUC only 0.7), with no significant additional discrimination between the aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia groups. Although the PSI had moderate ability to predict inpatient mortality, the observed mortality was considerably higher than predicted. It is possible that the PSI incompletely captures clinically relevant comorbidities (eg, malnutrition). Further study to improve mortality prediction of aspiration pneumonia patients could employ sensitivity analysis to determine optimal thresholds and weighting of the PSI components.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer hospital lengths of stay and took longer to achieve clinical stability than their nonaspiration counterparts. Time to clinical stability has been associated with increased posthospitalization mortality and is associated with time to switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics.[17] Although some component of hospital length‐of‐stay is subject to local practice patterns, time to clinical stability has explicit criteria for clinical improvement and failure, and therefore is less likely to be affected by local practice patterns.

We noted a relatively high (16%21%) incidence of prior antibiotic use among patients in this database. Analysis of antibiotic prescription patterns was limited, given the several different countries from which the database draws its cases. Although we used accepted criteria to define CAP cases, it is possible that this population may have a higher rate of resistant or uncommon pathogens than other studies of CAP that have populations with lower incidence of prior antibiotic use. Although not assessed, we suspect a significant component of the prior antibiotic use represented outpatient pneumonia treatment during the few days prior to visiting the hospital.

This study has several limitations, of which the most important may be that we used clinical determination for defining presence of aspiration pneumonia. This method is susceptible to the subjective perceptions of the treating clinician. We did not account for the effect of individual physicians in our model, although we did adjust for regional differences. The retrospective identification of patients allows for the possibility of selection bias, and therefore we have not attempted to make inferences regarding the relative incidence of pneumonia, nor did we adjust for temporal trends in diagnosis. The ratio of aspiration pneumonia patients to nonaspiration pneumonia patients may not necessarily reflect that observed in reality. Microbiologic and antibiotic data were unavailable for analysis. This study cannot inform on nonhospitalized patients with aspiration pneumonia, as only hospitalized patients were enrolled. The database identified cases of pneumonia, so it is possible for a patient to enter into the database more than once. Detection of mortality was limited to the inpatient setting rather than a set interval of 30 days. Inpatient mortality depends on length‐of‐stay patterns that may bias the mortality endpoint.[30] Also not assessed was the presence of a DNR order. It is possible that an older patient with greater comorbidities and disease severity may have care intentionally limited or withdrawn early by the family or clinicians.

Strengths of the study include its size and its multicenter, multinational population. The CAPO database is a large and well‐described population of patients with CAP.[17, 31] These attributes, as well as the clinician‐determined diagnosis, increase the generalizability of the study compared to a single‐center, single‐country study that employs investigator‐defined criteria.

CONCLUSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, who are nursing home residence, and have cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Our clinician‐diagnosed cohort appears similar to those derived using an investigator definition. Patients with aspiration pneumonia are older, and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia. They have greater mortality than their PSI score class would predict. Even after accounting for age, disease severity, and comorbidities, the presence of aspiration pneumonia independently conferred a greater than 2‐fold increase in inpatient mortality. These findings together suggest that aspiration pneumonia should be considered a distinct entity from typical pneumonia, and that additional research should be done in this field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.J.L. contributed to the study design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript. P.P. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. T.W. and E.W. contributed to the study design, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.A.R. and N.C.D. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.L. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. This investigation was partly supported with funding from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant 8UL1TR000105 [formerly UL1RR025764]). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Pneumonia is a common clinical syndrome with well‐described epidemiology and microbiology. Aspiration pneumonia comprises 5% to 15% of patients with pneumonia acquired outside of the hospital,[1] but is less well characterized despite being a major syndrome of pneumonia in the elderly.[2, 3] Difficulties in studying aspiration pneumonia include the lack of a sensitive and specific marker for aspiration as well as the potential overlap between aspiration pneumonia and other forms of pneumonia.[4, 5, 6] Additionally, clinicians have difficulty distinguishing between aspiration pneumonia, which develops after the aspiration of oropharyngeal contents, and aspiration pneumonitis, wherein inhalation of gastric contents causes inflammation without the subsequent development of bacterial infection.[7, 8] Central to the study of aspiration pneumonia is whether it should exist as its own entity, or if aspiration is really a designation used for pneumonia in an older patient with greater comorbidities. The ability to clearly understand how a clinician diagnoses aspiration pneumonia, and whether that method has face validity with expert definitions may allow for improved future research, improved generalizability of current or past research, and possibly better clinical care.

Several validated mortality prediction models exist for community‐acquired pneumonia (CAP) using a variety of clinical predictors, but their performance in patients with aspiration pneumonia is less well characterized. Most studies validating pneumonia severity scoring systems excluded aspiration pneumonia from their study population.[9, 10, 11] Severity scoring systems for CAP may not accurately predict disease severity in patients with aspiration pneumonia. The CURB‐65[9] (confusion, uremia, respiratory rate, blood pressure, age 65 years) and the eCURB[12] scoring systems are poor predictors of mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia, perhaps because they do not account for patient comorbidities.[13] The pneumonia severity index (PSI)[10] might predict mortality better than CURB‐65 in the aspiration population due to the inclusion of comorbidities.

Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with aspiration pneumonia are older and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities.[13, 14, 15] These single‐center studies also demonstrated greater mortality, more frequent admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and longer hospital lengths of stay in patients with aspiration pneumonia. These studies identified aspiration pneumonia by the presence of a risk factor for aspiration[15] or by physician billing codes.[13] In practice, however, the bedside clinician diagnoses a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, but the logic is likely vague and inconsistent. Despite the potential for variability with individual judgment, an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may perform better than individual judgments.[16] Because there is no gold standard for defining aspiration pneumonia, all previous research has been limited to definitions created by investigators. This multicenter study seeks to determine what clinical characteristics lead physicians to diagnose a patient as having aspiration pneumonia, and whether or not the clinician‐derived diagnosis is distinct and clinically useful.

Our objectives were to: (1) identify covariates associated with bedside clinicians diagnosing a pneumonia patient as having aspiration pneumonia; (2) compare aspiration pneumonia and nonaspiration pneumonia in regard to disease severity, patient demographics, comorbidities, and clinical outcomes; and (3) measure the performance of the PSI in aspiration pneumonia versus nonaspiration pneumonia.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

We performed a secondary analysis of the Community‐Acquired Pneumonia Organization (CAPO) database, which contains retrospectively collected data from 71 hospitals in 16 countries between June 2001 and December 2012. In each participating center, primary investigators selected nonconsecutive, adult hospitalized patients diagnosed with CAP. To decrease systematic selection biases, the selection of patients with CAP for enrollment in the trial was based on the date of hospital admission. Each investigator completed a case report form that was transferred via the internet to the CAPO study center at the University of Louisville (Louisville, KY). A sample of the data collection form is available at the study website (

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Patients 18 years of age and satisfying criteria for CAP were included in this study. A diagnosis of CAP required a new pulmonary infiltrate at time of hospitalization, and at least 1 of the following: new or increased cough; leukocytosis; leukopenia, or left shift pattern on white blood cell count; and temperature >37.8C or <35.6 C. We excluded patients with pneumonia attributed to mycobacterial or fungal infection, and patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus, as we believed these types of pneumonia differ fundamentally from typical CAP.

Patient Variables

Patient variables included presence of aspiration pneumonia, laboratory data, comorbidities, and measures of disease severity, including the PSI. The clinician made a clinical diagnosis of the presence or absence of aspiration for each patient by marking a box on the case report form. Outcomes included in‐hospital mortality, hospital length of stay up to 14 days, and time to clinical stability up to 8 days. All variables were obtained directly from the case report form. In accordance with previously published definitions, we defined clinical stability as the day the following criteria were all met: improved clinical signs (improved cough and shortness of breath), lack of fever for >8 hours, improving leukocytosis (decreased at least 10% from the previous day), and tolerating oral intake.[17, 18]

Statistical Analysis

Baseline characteristics of patients with aspiration and nonaspiration CAP were compared using 2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and the Mann‐Whitney U test for continuous variables.

To determine which patient variables were important in the physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, we performed logistic regression with initial covariates comprising the demographic, comorbidity, and disease severity measurements listed in Table 1. We included interactions between cerebrovascular disease and age, nursing home status, and confusion to improve model fit. We centered all variables (including binary indicators) according to the method outlined by Kraemer and Blasey to improve interpretation of the main effects.[19]

| Aspiration Pneumonia, N=451 | Nonaspiration Pneumonia, N=4,734 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 79 (6587) | 69 (5380) | <0.001 |

| % Male | 59% | 60% | 0.58 |

| Nursing home residence | 25% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Recent (30 days) antibiotic use | 21% | 16% | 0.017 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 35% | 14% | <0.001 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 25% | 27% | 0.62 |

| Congestive heart failure | 23% | 19% | 0.027 |

| Diabetes | 18% | 18% | 0.85 |

| Cancer | 12% | 10% | 0.12 |

| Renal disease | 10% | 11% | 0.53 |

| Liver disease | 6% | 5% | 0.29 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Pneumonia severity index | 123 (99153) | 92 (68117) | <0.001 |

| Confusion | 49% | 12% | <0.001 |

| PaO2 <60 mm Hg | 43% | 33% | <0.001 |

| BUN >30 g/dL | 42% | 23% | <0.001 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 34% | 28% | 0.003 |

| Pleural effusion | 25% | 21% | 0.07 |

| Respiratory rate >30 breaths/minute | 21% | 20% | 0.95 |

| pH <7.35 | 13% | 5% | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 11% | 6% | 0.001 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 9% | 7% | 0.30 |

| Systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg | 8% | 9% | 0.003 |

| Sodium <130 mEq/L | 8% | 6% | 0.08 |

| Heart rate >125 beats/minute | 8% | 5% | 0.71 |

| Glucose >250 mg/dL | 6% | 7% | 0.06 |

| Cavitary lesion | 0% | 0% | 0.67 |

| Clinical outcomes | |||

| In‐hospital mortality | 23% | 9% | <0.001 |

| Intensive care unit admission | 19% | 13% | 0.002 |

| Hospital length of stay, d | 9 (515) | 7 (412) | <0.001 |

| Time to clinical stability, d | 8 (48) | 4 (38) | <0.001 |

To determine if aspiration pneumonia had worse clinical outcomes compared to nonaspiration pneumonia, multiple methods were used. To compare the differences between the 2 groups with respect to time to clinical stability and length of hospital stay, we constructed Kaplan‐Meier survival curves and Cox proportional hazards regression models. The log‐rank test was used to determine statistical differences between the Kaplan‐Meier survival curves. To compare the impact of aspiration on mortality in patients with CAP, we conducted a propensity scorematched analysis. We chose propensity score matching over traditional logistic regression to balance variables among groups and to avoid the potential for overfit and multicollinearity. We considered a variable balanced after matching if its standardized difference was <10. All variables in the propensity scorematched analysis were balanced.

Although our dataset contained minimal missing data, we imputed any missing values to maintain the full study population in the creation of the propensity score. Missing data were imputed using the aregImpute function of the hmisc package of R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).[20, 21] We built the propensity score model using a variable selection algorithm described by Bursac et al.[22] Our model included variables for region (United States/Canada, Europe, Asia/Africa or Latin America) and the variables listed in Table 1, with the exception of the PSI and the 4 clinical outcomes. Given that previous analyses accounting for clustering by physician did not substantially affect our results,[23] our model did not include physician‐level variables and did not account for the clustering effects of physicians. Using the propensity scores generated from this model, we matched a case of aspiration CAP with a case of nonaspiration CAP.[24] We then constructed a general linear model using the matched dataset to obtain the magnitude of effect of aspiration on mortality.

We used receiver operating characteristic curves to define the diagnostic accuracy of the pneumonia severity index for the prediction of mortality among patients with aspiration pneumonia and those with nonaspiration pneumonia. SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and R version 2.15.3 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing) were used for all analyses. P values of 0.05 were considered statistically significant in all analyses.

RESULTS

Our initial query, after exclusion criteria, yielded a study population of 5185 patients (Figure 1). We compared 451 patients diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia to 4734 with CAP (Figure 1). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were older, more likely to live in a nursing home, had greater disease severity, and were more likely to be admitted to an ICU. Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer adjusted hospital lengths of stay and took more days to achieve clinical stability than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (Figure 2). After adjusting for all variables in Table 1, the Cox proportional hazards models demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia was associated with ongoing hospitalization (hazard ratio [HR] for discharge: 0.77, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.65‐0.91, P=0.002) and clinical instability (HR for attaining clinical stability: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.61‐0.84, P<0.001). Patients with aspiration pneumonia presented with greater disease severity than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Although there was no difference between groups in regard to temperature, respiratory rate, hyponatremia, or presence of pleural effusions or cavitary lesions, all other measured indices of disease severity were worse in patients with aspiration pneumonia. Patients with aspiration pneumonia were more likely to have cerebrovascular disease than those with nonaspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia patients also had increased prevalence of congestive heart failure. There was no appreciable difference between groups among other measured comorbidities.

The patient characteristics most associated with a physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia, identified using logistic regression, were confusion, residence in nursing home, and presence of cerebrovascular disease (odds ratio [OR]: of 4.4, 2.9, and 2.3, respectively), whereas renal disease was associated with decreased physician diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia over nonaspiration pneumonia (OR: 0.58) (Table 2).

| Covariate | Odds Ratio | 95% Confidence Intervals | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| Demographics | |||

| Age, y | 1.00 | 0.991.01 | 0.948 |

| Male | 1.20 | 0.941.54 | 0.148 |

| Nursing home residence | 2.93 | 2.134.00 | <0.001 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Cerebrovascular disease | 2.26 | 1.533.32 | <0.001 |

| Renal disease | 0.58 | 0.390.85 | 0.006 |

| Disease severity | |||

| Confusion | 4.41 | 3.405.72 | <0.001 |

| Hematocrit <30% | 1.59 | 1.062.33 | 0.020 |

| pH <7.35 | 1.67 | 1.102.47 | 0.013 |

| Temperature >37.8C or <35.6C | 1.60 | 1.072.35 | 0.019 |

| Multilobar pneumonia | 1.29 | 1.001.65 | 0.047 |

| Interaction terms | |||

| Age * cerebrovascular disease | 0.98 | 0.960.99 | 0.011 |

| Nursing home * cerebrovascular disease | 0.51 | 0.270.96 | 0.037 |

| Confusion * cerebrovascular disease | 0.70 | 0.421.17 | 0.175 |

Observed in‐patient mortality of aspiration pneumonia was 23%. This mortality was considerably higher than a mean PSI score of 123 would predict (class IV risk group, with expected 30‐day mortality of 8%9%[25]). The PSI score's ability to predict inpatient mortality in patients with aspiration pneumonia was moderate, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.71. This was similar to its performance in patients with nonaspiration pneumonia (AUC of 0.75) (Figure 3). These values are lower than the AUC of 0.81 for the PSI in predicting mortality derived from a meta‐analysis of 31 other studies.[26]

Our regression model after propensity score matching demonstrated that aspiration pneumonia independently confers a 2.3‐fold increased odds for inpatient mortality (95% CI: 1.56‐3.45, P<0.001).

DISCUSSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, nursing home residence, or cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Although this is unsurprising, it is notable that these patients are more than twice as likely to die in the inpatient setting, even after accounting for age, comorbidities, and disease severity. These findings are similar to three previously published studies comparing aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia at single institutions, albeit using different aspiration pneumonia definitions.[13, 14, 15] This study is the first large, multicenter, multinational study to demonstrate these findings.

Central to the interpretation of our results is the method of diagnosing aspiration versus nonaspiration. A bottom‐up method that relies on a clinician to check a box for aspiration may appear poorly reproducible. Because there is no diagnostic gold standard, clinicians may use different criteria to diagnose aspiration, creating potential for idiosyncratic noise. The strength of the wisdom of the crowd method used in this study is that an aggregate estimation from independent judgments may reduce the noise from individual judgments.[16] Although clinicians may vary in why they diagnose a particular patient as having aspiration pneumonia, it appears that the overwhelming reason for diagnosing a patient as having aspiration pneumonia is the presence of confusion, followed by previous nursing home residence or cerebrovascular disease. This finding has some face validity when compared with studies using an investigator definition, as altered mental status, chronic debility, and cerebrovascular disease are either prominent features of the definition of aspiration pneumonia[8] or frequently observed in patients with aspiration pneumonia.[13, 15] The distribution of cerebrovascular disease among our study's aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia patients was similar to studies that used formal criteria in their definitions.[13, 15] Although nursing home residence was more likely in aspiration pneumonia patients, the majority of aspiration pneumonia patients were residing in the community, suggesting that aspiration is not simply a surrogate for healthcare‐associated pneumonia. Although patients with aspiration pneumonia are typically older than their nonaspiration counterparts, it appears that age is not a key determinant in the diagnosis of aspiration. With aspiration pneumonia, confusion, nursing home residence, and the presence of cerebrovascular disease are the greatest contributors in the clinical diagnosis, more than age.

Our data demonstrate that aspiration pneumonia confers increased odds for mortality, even after adjustment for age, disease severity, and comorbidities. These data suggest that aspiration pneumonia is a distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia, and that this disease is worse than nonaspiration CAP. If aspiration pneumonia is distinct from nonaspiration pneumonia, some unrecognized host factor other than age, disease severity, or the captured comorbidities decreases survival in aspiration pneumonia patients. However, it is also possible that aspiration pneumonia is merely a clinical designation for one end of the pneumonia spectrum, and we and others have failed to completely account for all measures of disease severity or all measures of comorbidities. Examples of unmeasured comorbidities would include presence of oropharyngeal dysphagia, which is not assessed in the database but could have a significant effect on clinical diagnosis. Unmeasured covariates can include measures beyond that of disease severity or comorbidity, such as the presence of a do not resuscitate (DNR) order, which could have a significant confounding effect on the observed association. A previous, single‐center study demonstrated that increased 30‐day mortality in aspiration pneumonia was mostly attributable to greater disease severity and comorbidities, although aspiration pneumonia independently conferred greater risk for adverse long‐term outcomes.[15] We propose that aspiration pneumonia represents a clinically distinct entity from nonaspiration pneumonia. Patients with chronic aspiration are often chronically malnourished and may have different oral flora than patients without chronic aspiration.[27, 28] Chronic aspiration has been associated with granulomatous reaction, organizing pneumonia, diffuse alveolar damage, and chronic bronchiolitis.[29] Chronic aspiration may elicit changes in the host physiology, and may render the host more susceptible to the development of secondary bacterial infection with morbid consequences.

The ability of the PSI to predict inpatient mortality was moderate (AUC only 0.7), with no significant additional discrimination between the aspiration and nonaspiration pneumonia groups. Although the PSI had moderate ability to predict inpatient mortality, the observed mortality was considerably higher than predicted. It is possible that the PSI incompletely captures clinically relevant comorbidities (eg, malnutrition). Further study to improve mortality prediction of aspiration pneumonia patients could employ sensitivity analysis to determine optimal thresholds and weighting of the PSI components.

Patients with aspiration pneumonia had longer hospital lengths of stay and took longer to achieve clinical stability than their nonaspiration counterparts. Time to clinical stability has been associated with increased posthospitalization mortality and is associated with time to switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics.[17] Although some component of hospital length‐of‐stay is subject to local practice patterns, time to clinical stability has explicit criteria for clinical improvement and failure, and therefore is less likely to be affected by local practice patterns.

We noted a relatively high (16%21%) incidence of prior antibiotic use among patients in this database. Analysis of antibiotic prescription patterns was limited, given the several different countries from which the database draws its cases. Although we used accepted criteria to define CAP cases, it is possible that this population may have a higher rate of resistant or uncommon pathogens than other studies of CAP that have populations with lower incidence of prior antibiotic use. Although not assessed, we suspect a significant component of the prior antibiotic use represented outpatient pneumonia treatment during the few days prior to visiting the hospital.

This study has several limitations, of which the most important may be that we used clinical determination for defining presence of aspiration pneumonia. This method is susceptible to the subjective perceptions of the treating clinician. We did not account for the effect of individual physicians in our model, although we did adjust for regional differences. The retrospective identification of patients allows for the possibility of selection bias, and therefore we have not attempted to make inferences regarding the relative incidence of pneumonia, nor did we adjust for temporal trends in diagnosis. The ratio of aspiration pneumonia patients to nonaspiration pneumonia patients may not necessarily reflect that observed in reality. Microbiologic and antibiotic data were unavailable for analysis. This study cannot inform on nonhospitalized patients with aspiration pneumonia, as only hospitalized patients were enrolled. The database identified cases of pneumonia, so it is possible for a patient to enter into the database more than once. Detection of mortality was limited to the inpatient setting rather than a set interval of 30 days. Inpatient mortality depends on length‐of‐stay patterns that may bias the mortality endpoint.[30] Also not assessed was the presence of a DNR order. It is possible that an older patient with greater comorbidities and disease severity may have care intentionally limited or withdrawn early by the family or clinicians.

Strengths of the study include its size and its multicenter, multinational population. The CAPO database is a large and well‐described population of patients with CAP.[17, 31] These attributes, as well as the clinician‐determined diagnosis, increase the generalizability of the study compared to a single‐center, single‐country study that employs investigator‐defined criteria.

CONCLUSION

Pneumonia patients with confusion, who are nursing home residence, and have cerebrovascular disease are more likely to be diagnosed with aspiration pneumonia by clinicians. Our clinician‐diagnosed cohort appears similar to those derived using an investigator definition. Patients with aspiration pneumonia are older, and have greater disease severity and more comorbidities than patients with nonaspiration pneumonia. They have greater mortality than their PSI score class would predict. Even after accounting for age, disease severity, and comorbidities, the presence of aspiration pneumonia independently conferred a greater than 2‐fold increase in inpatient mortality. These findings together suggest that aspiration pneumonia should be considered a distinct entity from typical pneumonia, and that additional research should be done in this field.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Disclosures: M.J.L. contributed to the study design, data analysis, statistical analysis, and writing of the manuscript. P.P. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. T.W. and E.W. contributed to the study design, statistical analysis, and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. J.A.R. and N.C.D. contributed to the study design and revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. M.L. takes responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, from inception to published article. This investigation was partly supported with funding from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health (grant 8UL1TR000105 [formerly UL1RR025764]). The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Severe community‐acquired pneumonia. Epidemiology and prognostic factors. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144(2):312–318.