User login

‘They’re out to get me!’: Evaluating rational fears and bizarre delusions in paranoia

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

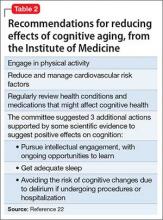

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

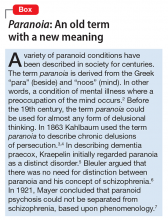

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

Even among healthy individuals, feelings of paranoia are not unusual. In modern psychiatry, we consider paranoia to be a pattern of unfounded thinking, centered on the fearful experience of perceived victimization or threat of intentional harm. This means that a patient with paranoia is, by nature, difficult to engage in treatment. A patient might perceive the clinician as attempting to mislead or manipulate him. A therapeutic alliance could require patience on the part of the clinician, creativity,1 and abandoning attempts at rational “therapeutic” persuasion. The severity of symptoms determines the approach.

In this article, we review the nature of paranoia and the continuum of syndromes to which it is a central feature, as well as treatment approaches.

Categorization and etiology

Until recently, clinicians considered “paranoid” to be a subtype of schizophrenia (Box2-7); in DSM-5 the limited diagnostic stability and reliability of the categorization rendered the distinction obsolete.8 There are several levels of severity of paranoia; this thought process can present in simple variations of normal fears and concerns or in severe forms, with highly organized delusional systems.

The etiology of paranoia is not clear. Over the years, it has been attributed to defense mechanisms of the ego, habitual fears from repetitive exposure, or irregular activity of the amygdala. It is possible that various types of paranoia could have different causes. Functional MRIs indicate that the amygdala is involved in anxiety and threat perception in both primates and humans.9

Rational fear vs paranoia

Under the right circumstances, anyone could sense that he (she) is being threatened. Such feelings are normal in occupied countries and nations at war, and are not pathologic in such contexts. Anxiety about potential danger and harassment under truly oppressive circumstances might be biologically ingrained and have value for survival. It is important to employ cultural sensitivity when distinguishing pathological and nonpathological paranoia because some immigrant populations might have increased prevalence rates but without a true mental illness.10

Perhaps the key to separating realistic fear from paranoia is the recognition of whether the environment is truly safe or hostile; sometimes this is not initially evident to the clinician. The first author (J.A.W.) experienced this when discovering that a patient who was thought to be paranoid was indeed being stalked by another patient.

Rapid social change makes sweeping explanations about the range of threats experienced by any one person of limited value. Persons living with serious and persistent mental illness experience stigma—harassment, abuse, disgrace—and, similar to victims of repeated sexual abuse and other violence, are not necessarily unreasonable in their inner experience of omnipresent threat. In addition, advances in surveillance technology, as well as the media proliferation of depictions of vulnerability and threat, can plant generalized doubt of historically trusted individuals and systems. Under conditions of severe social discrimination or life under a totalitarian regime, constant fear for safety and worry about the intentions of others is reasonable. We must remember that during the Cold War many people in Eastern Europe had legitimate concerns that their phones were tapped. There are still many places in the world where the fear of government or of one’s neighbors exists.

- paranoid personality disorder

- delusional disorder

- paranoia in schizophrenia (Table).

Paranoid personality disorder

The nature of any personality disorder is a long-standing psychological and behavioral pattern that differs significantly from the expectations of one’s culture. Such beliefs and behaviors typically are pervasive across most aspects of the individual’s interactions, and these enduring patterns of personality usually are evident by adolescence or young adulthood. Paranoid personality disorder is marked by pervasive distrust of others. Typical features include:

- suspicion about other people’s motives

- sensitivity to criticism

- keeping grudges against alleged offenders.8

The patient must have 4 of the following symptoms to confirm the diagnosis:

- suspicion of others and their motives

- reluctance to confide in others, due to lack of trust

- recurrent doubts about the fidelity of a significant other

- preoccupation with doubt regarding trusting others

- seeing threatening meanings behind benign remarks or events

- perception of attacks upon one’s character or reputation

- bears persistent grudges.8

Individuals with paranoid personality disorder tend to lead maladaptive lifestyles and might present as irritable, unpleasant, and emotionally guarded. Paranoid personality disorder is not a form of delusion, but is a pattern of habitual distrust of others.

The disorder generally is expressed verbally, and is seldom accompanied by hallucinations or unpredictable behavior. Distrust of others might result in social isolation and litigious behavior.8 Alternately, a patient with this disorder might not present for treatment until later in life after the loss of significant supporting factors, such as the death of parents or loss of steady employment. Examination of these older individuals is likely to reveal long-standing suspiciousness and distrust that previously was hidden by family members. For example, a 68-year-old woman might present saying that she can’t trust her daughter, but her recently deceased spouse would not let her discuss the topic outside of the home.

The etiology of paranoid personality disorder is unknown. Family studies suggest a possible a genetic connection to paranoia in schizophrenia.12 Others hypothesize that this dysfunction of personality might originate in early feelings of anxiety and low self-esteem, learned from a controlling, cruel, or sadistic parent; the patient then expects others to reject him (her) as the parent did.13,14 Such individuals might develop deep-seated distrust of others as a defense mechanism. Under stress, such as during a medical illness, patients could develop brief psychoses. Antipsychotic treatment might be useful in some cases of paranoid personality disorder, but should be limited.

Delusional disorder

Delusional disorder is a unique form of psychosis. Patients with delusional disorder might appear rational—as long as they are in independent roles—and their general functioning could go unnoticed. This could change when the delusions predominate their thoughts, or their delusional behavior is unacceptable in a structured environment. Such individuals often suffer from a highly specific delusion fixed on 1 topic. These delusions generally are the only psychotic feature. The most common theme is that of persecution. For example, a person firmly believes he is being followed by foreign agents or by a religious organization, which is blatantly untrue. Another common theme is infidelity.

Paranoia in delusional disorder is about something that is not actually occurring, but could.3 In other words, the delusion is not necessarily bizarre. The patient may have no evidence or could invent “evidence,” yet remain completely resistant to any logical argument against his belief system. In many situations, individuals with delusional disorder function normally in society, until the delusion becomes severe enough to prompt clinical attention.

Paranoia in schizophrenia

In patients with schizophrenia with paranoia, the typical symptoms of disorganization and disturbed affect are less prominent. The condition develops in young adulthood, but could start at any age. Its course typically is chronic and requires psychiatric treatment; the patient may require hospital care.

Although patients with delusional disorder and those with schizophrenia both have delusions, the delusions of the latter typically are bizarre and unlikely to be possible. For example, the patient might believe that her body has been replaced with the inner workings of an alien being or a robot. The paranoid delusions of persons with delusional disorder are much more mundane and could be plausible. Karl Jaspers, a clinician and researcher in the early 20th century, separated delusional disorder from paranoid schizophrenia by noting that the former could be “understandable, even if untrue” while the latter was “not within the realm of understandability.”5

A patient with schizophrenia with paranoid delusions usually experiences auditory hallucinations, such as voices threatening persecution or harm. When predominant, patients could be aroused by these fears and can be dangerous to others.2,4,5

Other presentations of paranoia

Paranoia can occur in affective disorders as well.13 Although the cause is only now being understood, clinicians have put forth theories for many years. A depressed person might suffer from excessive guilt and feel that he deserves to be persecuted, while a manic patient might think she is being persecuted for her greatness. In the past, response to electroconvulsive therapy was used to distinguish affective paranoia from other types.2

Paranoia in organic states

Substance use. Psychostimulants, which are known for their motor activity and arousal enhancing properties, as well as the potential for abuse and other negative consequences, could lead to acute paranoid states in susceptible individuals.15-17 In addition, tetrahydrocannabinol, the active chemical in Cannabis, can cause acute psychotic symptoms, such as paranoia,18,19 in a dose-dependent manner. A growing body of evidence suggests that a combination of Cannabis use with a genetic predisposition to psychosis may put some individuals at high risk of decompensation.19 Of growing concern is the evidence that synthetic cannabinoids, which are among the most commonly used new psychoactive substances, could be associated with psychosis, including paranoia.20

Dementia. Persons with dementia often are paranoid. In geriatric patients with dementia, a delusion of thievery is common. When a person has misplaced objects and can’t remember where, the “default” cognition is that someone has taken them. This confabulation may progress to a persistent paranoia and can be draining on caregivers.

Treating paranoia

A patient with paranoia usually has poor insight and cannot be reasoned with. Such individuals are quick to incorporate others into their delusional theories and easily develop notions of conspiracy. In acute psychosis, when the patient presents with fixed beliefs that are not amenable to reality orientation, and poses a threat to his well-being or that of others, alleviating underlying fear and anxiety is the first priority. Swift pharmacologic measures are required to decrease the patient’s underlying anxiety or anger, before you can try to earn his trust.

Psychopharmacologic interventions should be specific to the diagnosis. Antipsychotic medications generally will help decrease most paranoia, but affective syndromes usually require lithium or divalproex for best results.14,21

Develop a therapeutic relationship. The clinician must approach the patient in a practical and straightforward manner, and should not expect a quick therapeutic alliance. Transference and countertransference develop easily in the context of paranoia. Focus on behaviors that are problematic for the patient or the milieu, such as to ensure a safe environment. The patient needs to be aware of how he could come across to others. Clear feedback about behavior, such as “I cannot really listen to you when you’re yelling,” may be effective. It might be unwise to confront delusional paranoia in an agitated patient. Honesty and respect must continue in all communications to build trust. During assessment of a paranoid individual, evaluate the level of dangerousness. Ask your patient if he feels like acting on his beliefs or harming the people that are the targets of his paranoia.

As the patient begins to manage his anxiety and fear, you can develop a therapeutic alliance. The goals of treatment need be those of the patient—such as staying out of the hospital, or behaving in a manner that is required for employment. Over time, work toward growing the patient’s capacity for social interaction and productive activity. Insight might be elusive; however, some patients with paranoia can learn to take a detached view of their thoughts and emotions, and consider them impermanent events of the mind that make their lives difficult. Practice good judgment when aiming for recovery in a patient who does not have insight. For example, a patient can recognize that although there could be a microchip in his brain, he feels better when he takes medication.

In the case of paranoid personality disorder, treatment, as with most personality disorders, can be difficult. The patient might be unlikely to accept help and could distrust caregivers. Cognitive-behavioral therapy could be useful, if the patient can be engaged in the therapeutic process. Although it might be difficult to obtain enhanced insight, the patient could accept logical explanations for situations that provoke distrust. As long as anxiety and anger can be kept under control, the individual might learn the value of adopting the lessons of therapy. Pharmacological treatments are aimed at reducing the anxiety and anger experienced by the paranoid individual. Antipsychotics may be useful for short periods or during a crisis.14,21

The clinician must remain calm and reassuring when approaching an individual with paranoia, and not react to the projection of paranoid feelings from the patient. Respect for the patient can be conveyed without agreeing with delusions or bizarre thinking. The clinician must keep agreements and appointments with the client to prevent the erosion of trust. Paranoid conditions might respond slowly to pharmacological treatment, therefore establishing a consistent therapeutic relationship is essential.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

1. Frank C. Delirium, consent to treatment, and Shakespeare. A geriatric experience. Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:875-876.

2. Hamilton M. Fish’s schizophrenia. Bristol, United Kingdom: John Wright and Sons; 1962.

3. Munro A. Delusional disorder. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2000.

4. Kahlbaum K. Die gruppierung de psychischen krankheiten. Danzig, Germany: Verlag von A. W. Kafemann; 1853.

5. Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Barclay RM, trans. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1976.

6. Bleuler E. Dementia praecox or the group of schizophrenias. Ainkia J, trans. New York, NY: International University Press; 1950.

7. Mayer W. Uber paraphrene psychosen. Zeitschrift fur die gesamte. Neurology und Psychiatrie. 1921;71:187-206.

8. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

9. Pinkham AE, Liu P, Lu H, et al. Amygdala hyperactivity at rest in paranoid individuals with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(8):784-792.

10. Sen P, Chowdhury AN. Culture, ethnicity and paranoia. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2006;8(3):174-178.

11. Szasz TS. The manufacture of madness: a comparative study of the inquisition and the mental health movement. New York, NY: Harper and Row; 1970.

12. Schanda H, Berner P, Gabriel E, et al. The genetics of delusional psychosis. Schizophr Bull. 1983;9(4):563-570.

13. Levy B, Tsoy E, Brodt T, et al. Stigma, social anxiety and illness severity in bipolar disorder: implications for treatment. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):55-64.

14. Benjamin LS. Interpersonal diagnosis and treatment of personality disorders. New York, NY: Gilford Press; 1993.

15. Busardo FP, Kyriakou C, Cipilloni L, et al. From clinical application to cognitive enhancement. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(2):281-295.

16. McKetin R, Gardner J, Baker AL, et al. Correlates of transient versus persistent psychotic symptoms among dependent methylamphetamine users. Psychiatry Res. 2016;238:166-171.

17. Djamshidian A. The neurobehavioral sequelae of psychostimulant abuse. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2015;120:161-177.

18. Haney M, Evins AE. Does cannabis cause, exacerbate or ameliorate psychiatric disorders? An oversimplified debate discussed. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41(2):393-401.

19. Bui QM, Simpson S, Nordstrom K. Psychiatric and medical management of marijuana intoxication in the emergency department. West J Emerg Med. 2015;16(3):414-417.

20. Seely KA, Lapoint J, Moran JH, et al. Spice drugs are more than harmless herbal blends: a review of the pharmacology and toxicology of synthetic cannabinoids. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012;39(2):234-243.

21. Lake CR. Hypothesis: grandiosity and guilt cause paranoia; paranoid schizophrenia is a psychotic mood disorder: a review. Schizophr Bull. 2008;34(6):1151-1162.

Is it a 'senior moment' or early dementia? Addressing memory concerns in older patients

Many older patients are concerned about their memory. The “worried well” may come into your office with a list of things they can’t recall, yet they remember each “deficit” quite well. Anticipatory anxiety about one’s own decline is common, and is most often concerned with changes in memory.1,2

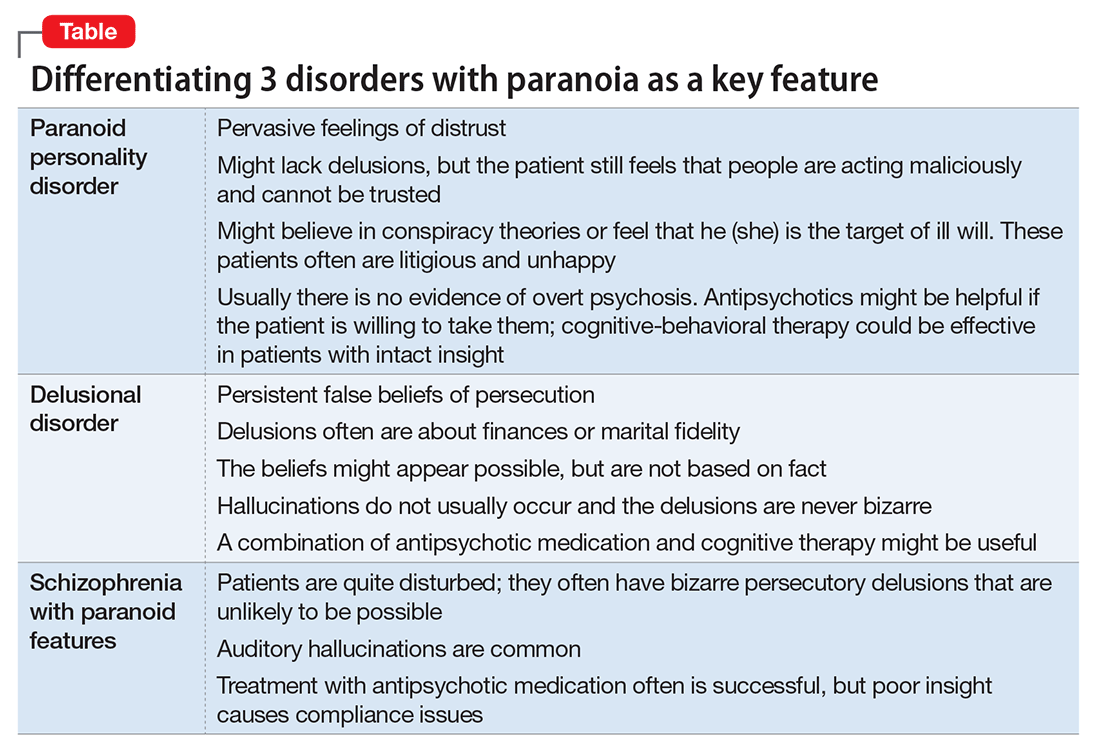

Patients with dementia or early cognitive decline often are oblivious to their cognitive changes, however. Of particular concern is progressive dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Although jokes about “senior moments” are common, concern about AD incurs deep-seated worry. It is essential for clinicians to differentiate normal cognitive changes of aging—particularly those in memory—from early signs of neurodegenerative disease (Table 13).

In this article, we review typical memory changes in persons age >65, and differentiate these from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an increasingly recognized prodrome of AD. Clinicians armed with knowledge of MCI are able to reassure the worried well, or recommend neuropsychological testing as indicated.

Is memory change inevitable with aging?

Memory loss is a common problem in aging, with variable severity. Research is establishing norms in cognitive functioning through the ninth decade of life.4 Controversy about sampling, measures, and methods abound,5 and drives prolific research on the subject, which is beyond the scope of this article. It has been demonstrated that there are a few “optimally aging” persons who avoid memory decline altogether.5,6 Most researchers and clinicians agree, however, that memory change is pervasive with advancing age.

Memory change follows a gradient with recent memories lost to a greater degree than remote memories (Ribot’s Law).7 Forgetfulness is characteristic of normal aging, and frequently manifests with misplaced objects and short-term lapses. However, this is not pathological—as long as the item or memory is recalled within 24 to 48 hours.

Compared with younger adults, healthy older adults are less efficient at encoding new information. Subsequently, they have more difficulty retrieving data, particularly after a delay. The time needed to learn and use new information increases, which is referred to as processing inefficiency. This influences changes in test performance across all cognitive domains, with decreases in measures of mental processing speed, working memory, and problem-solving.

Many patients who complain about “forgetfulness” are experiencing this normal change. It is not uncommon for a patient to offer a list of things she has forgotten recently, along with the dates and circumstances in which she forgot them. Because she sometimes forgets things, but remembers them later, there likely is nothing to worry about. If reminders—such as her list—help, this too is a good sign, because it shows her resourcefulness in using accommodations. If the patient is managing her normal activities, reassurance is warranted.

Mild cognitive impairment

Since at least 1958,8 clinical observations and research have recognized a prodrome that differentiates cognitive changes predictive of dementia from those that represent typical aging. Several studies and methods have converged toward consensus that MCI is a valid construct for that purpose, with ecological validity and sound predictive value. Clinical value is evident when a patient does not meet criteria for MCI; in this case, the clinician can reassure the worried well with conviction.

Revealing the diagnosis of MCI to patients requires sensitivity and assurance that you will reevaluate the condition annually. Although there is no evidence-based remedy for MCI or means to slow its progression to dementia, data are rapidly accruing regarding the value of lifestyle changes and other nonpharmacologic interventions.9

Recognizing MCI most simply requires 2 criteria:

The patient’s expressed concern about decline in cognitive functioning from a previous level of performance. Alternately, a caretaker’s report is valuable because the patient might lack insight. You are not looking for an inability to perform activities of daily living, which is indicative of frank dementia; rather, you want to determine whether the person’s independence in functional abilities is preserved, although less efficient. Patients might repeatedly report occurrences of new problems, although modest, in some cases. Although problems with memory often are the most frequently reported symptoms, changes can be observed in any cognitive domain. Uncharacteristic inability to understand instructions, frustration with new tasks, and inflexibility are common.

Quantified clinical assessment that the patient’s cognitive decline exceeds norms of his age cohort. Clinicians are already familiar with many of these tests (5-minute recall, clock face drawing, etc.). For MCI, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which is specifically designed for MCI.10 It takes only 10 minutes to administer. Multiple versions of the MoCA, and instructions for its administration are available for provider use at www.mocatest.org.

When these criteria are met—a decline in previous functioning and an objective clinical confirmation—referral for neuropsychological testing is recommended. Subtypes of MCI—amnestic and non-amnestic—have been employed to specify the subtype (amnesic) that is most consistent with prodromal AD. However, this dichotomous scheme does not adequately explain or capture the heterogeneity of MCI.11,12

Medical considerations

Just as all domains of cognition are correlated to some degree, the overall health status of a person influences evaluation of memory. Variables, such as fatigue, test anxiety, mood, motivation, visual and auditory acuity, education, language fluency, attention, and pain, affect test performance. In addition, clinician rapport and the manner in which tests are administered must be considered.

Depression can mimic MCI. A depressed patient often has poor expectations of himself and slowed thinking, and might exaggerate symptoms. He might give up on tests or refuse to complete them. His presentation initially could suggest cognitive decline, but depression is revealed when the clinician pays attention to vegetative signs (insomnia, poor appetite) or suicidal ideation. There is growing evidence that subjective complaints of memory loss are more frequently associated with depression than with objective measures of cognitive impairment.13,14

Other treatable conditions can present with cognitive change (the so-called reversible dementias). A deficiency of vitamin B12, thiamine, or folate often is seen because quality of nutrition generally decreases with age. Hyponatremia and dehydration can present with confusion and memory impairment. Other treatable conditions include:

- cerebral vasculitis, which could improve with immune suppressants

- endocrine diseases, which might respond to hormonal or surgical treatment

- normal pressure hydrocephalus, which can be relieved by surgical placement of a shunt.

Take a complete history. What exactly is the nature of the patient or caregiver’s complaint? You need to attempt to engage the patient in conversation, observing his behavior during the evaluation. Is there notable delay in response, difficulty in attention and focus, or in understanding questions?

The content of speech is an indicator of the patient’s information processing. Ask the patient to recite as many animals from the jungle as possible. Most people can come up with at least 15. The person with MCI will likely name fewer animals, but may respond well to cueing, and perform better in recognition (eg, pictures or drawings) vs retrieval. When asked to describe a typical day, the patient may offer a vague, nonchalant response eg, “I keep busy watching the news.” This kind of response may be evidence of confabulation; with further questioning, he is unable to identify current issues of interest.

Substance abuse. It is essential that clinicians recognize that elders are not exempt from alcohol and other drug abuse that affects cognition. Skilled history taking, including attention to non-verbal responses, is indicated. A defensive tone, rolling of eyes, or silent yet affirmative nodding are means by which caregivers offer essential “clues” to the provider.

A quick screening tool for the office is valuable; many clinicians are most familiar with the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination, which are known to be sensitive in detecting memory problems and other cognitive defects. As we noted, the MoCA is now recommended for differentiating more subtle changes of MCI.10,15 It is important to remember that common conditions such as an urinary tract infection or trauma after anesthesia for routine procedures such as colonoscopy can cause cognitive impairment. Again, eliciting history from a family member is valuable because the patient may have forgotten vital data.

A good physical exam is important when evaluating for dementia. Look for any neurologic anomaly. Check for disinhibition of primitive reflexes, eg, abnormal grasp or snout response or Babinski sign. Compare the symmetry and strength of deep tendon reflexes. Look for neurologic soft signs. Any pathological reflex response can be an important clue about neurodegeneration or space-occupying lesions. We recall seeing a 62-year-old man whose spouse brought him for evaluation for new-onset reckless driving and marked inattention to personal hygiene that developed over the previous 3 months. On examination, he appeared disheveled and had a dull affect, although disinhibited and careless. His mentation and gait were slowed. He denied distress of any kind. Frontal release signs were noted on exam. An MRI revealed a space-occupying lesion of the frontal lobe measuring 3 cm wide with a thickness of 2 cm, which pathology confirmed as a benign tumor.

Always check for arrhythmia and hypertension. These are significant risk factors for ischemic brain disease, multiple-infarct stroke, or other forms of vascular dementia. A shuffling gait suggests Parkinson’s disease, or even Lewy body dementia, or medication-related conditions, for example, from antipsychotics.

Take a medication history. Many common treatments for anxiety and insomnia can cause symptoms that mimic dementia. Digitalis toxicity results in poor recall and confusion. Combinations of common medicines (antacids, antihistamines, and others) compete for metabolic pathways and lead to altered mental status. Referencing the Beers List16 is valuable; anticholinergics, benzodiazepines, and narcotic analgesics are of special concern. The latter could still be useful for comfort care at the end of life.

It is common for seniors to take a variety of untested and unproven supplements in the hope of preventing or lessening memory problems. In addition to incurring significant costs, the indiscriminate use of supplements poses risks of toxicity, including unintended interactions with prescribed medications. Many older adults do not disclose their use of these supplements to providers because they do not consider them “medicine.”

Labs. The next level of evaluation calls for a basic laboratory workup. Check complete blood count, liver enzymes, thyroid function tests, vitamin D, B12 and folate levels; perform urinalysis and a complete metabolic panel. Look at a general hormone panel; abnormal values could reveal a pituitary adenoma. (In the past 33 years, the first author has found 42 pituitary tumors in the workup of mental status change.)

We use imaging, such as a CT or MRI of the brain, in almost all cases of suspected dementia. Cerebral atrophy, space-occupying lesions, and shifting of the ventricles often correspond with cognitive decline.

Treatment

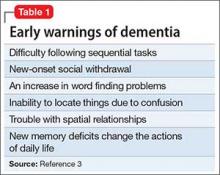

Effective treatment of dementia remains elusive. Other than for the “reversible dementias,” pharmacotherapy has shown less progress than had been expected. Donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine, and memantine could slow disease progression in some cases. There have been many studies for dementia preventives and treatments. Extensive reviews and meta-analyses, including those of randomized controlled trials17-19 abound for a variety of herbs, supplements, and antioxidants; none have shown compelling results. Table 2 lists Institute of Medicine recommendations supported by evidence that could reduce effects of cognitive aging.20

Recommendations from collaboration between the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association21 state that research should focus on biomarkers, such as neural substrates or genotypes. Indicators of oxidative stress (cytokines) and inflammation (isoprostanes) show promise as measures of brain changes that correspond with increased risk of AD or other dementias.

Summing up

Older adults are a heterogeneous group. Intellectual capacity does not diminish with advancing age. Many elders now exceed expectations for productivity, athletic ability, scientific achievement, and the creative arts. Others live longer with diminished quality of life, their health compromised by progressive neurodegenerative disease.

Age-associated memory change often is exaggerated and feared by older adults and, regrettably, is associated with inevitable functional impairment and is seen as heralding the loss of autonomy. The worried well are anxious, although the stigma associated with cognitive decline may preclude confiding their concerns.

Providers need the tools and acumen to treat patients along an increasingly long continuum of time, including conveyance of evidence-based encouragement toward optimal health and vitality.

1. Serby MJ, Yhap C, Landron EY. A study of herbal remedies for memory complaints. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22(3):345-347.

2. Jaremka LM, Derry HM, Bornstein R, et al. Omega-3 supplementation and loneliness-related memory problems: secondary analyses of a randomized controlled trial. Psychosom Med. 2014;76(8):650-658.

3. Depp CA, Harmell A, Vania IV. Successful cognitive aging. In: Pardon MC, Bondi MW, eds. Behavioral neurobiology of aging. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2012:35-50.

4. Invik RJ, Malec JF, Smith GE, et al. Mayo’s older Americans normative studies: WAIS-R, WMS-R, and AVLT norms for ages 56 to 97. Clin Neuropsychol. 1992;6(suppl 1):1-104.

5. Powell DH, Whitla DK. Profiles in cognitive aging. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press; 1994.

6. Negash S, Smith GE, Pankratz SE, et al. Successful aging: definitions and prediction of longevity and conversion to mild cognitive impairment. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(6):581-588.

7. Ribot T. Diseases of memory: an essay in the positive psychology. London, United Kingdom: Kegan Paul Trench; 1882.

8. Kral VA. Neuropsychiatric observations in old peoples home: studies of memory dysfunction in senescence. J Gerontol. 1958;13(2):169-176.

9. Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2020-2029.

10. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(4):695-699.

11. Clark LR, Delano-Wood L, Lisbon DJ, et al. Are empirically-derived subtypes of mild cognitive impairment consistent with conventional subtypes? J Intl Neuropsychol Soc. 2013;19(6):1-11.

12. Ganguli M, Snitz BE, Saxton JA, et al. Outcomes of mild cognitive impairment by definition: a population study. Arch Neurol. 2011;68(6):761-767.

13. Bartley M, Bokde AL, Ewers M, et al. Subjective memory complaints in community dwelling older people: the influence of brain and psychopathology. Intl J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;27(8):836-843.

14. Chung JC, Man DW. Self-appraised, informant-reported, and objective memory and cognitive function in mild cognitive impairment. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(2):187-193.

15. Tsoi KK, Chan JY, Hirai HW, et al. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(9):1450-1458.

16. American Geriatrics Society 2012 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society updated Beers Criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(4):616-631.

17. May BH, Yang AW, Zhang AL, et al. Chinese herbal medicine for mild cognitive impairment and age associated memory impairment: a review of randomised controlled trials. Biogerontology. 2009;10(2):109-123.

18. Loef M, Walach H. The omega-6/omega-3 ratio and dementia or cognitive decline: a systematic review on human studies and biological evidence. J Nutr Gerontol Geriatr. 2013;32(1):1-23.

19. Solfrizzi VP, Panza F. Plant-based nutraceutical interventions against cognitive impairment and dementia: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy of a standardized Gingko biloba extract. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43(2):605-611.

20. Institute of Medicine. Cognitive aging: progress in understanding and opportunities for action. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

21. Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):270-279.

Many older patients are concerned about their memory. The “worried well” may come into your office with a list of things they can’t recall, yet they remember each “deficit” quite well. Anticipatory anxiety about one’s own decline is common, and is most often concerned with changes in memory.1,2

Patients with dementia or early cognitive decline often are oblivious to their cognitive changes, however. Of particular concern is progressive dementia, especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Although jokes about “senior moments” are common, concern about AD incurs deep-seated worry. It is essential for clinicians to differentiate normal cognitive changes of aging—particularly those in memory—from early signs of neurodegenerative disease (Table 13).

In this article, we review typical memory changes in persons age >65, and differentiate these from mild cognitive impairment (MCI), an increasingly recognized prodrome of AD. Clinicians armed with knowledge of MCI are able to reassure the worried well, or recommend neuropsychological testing as indicated.

Is memory change inevitable with aging?

Memory loss is a common problem in aging, with variable severity. Research is establishing norms in cognitive functioning through the ninth decade of life.4 Controversy about sampling, measures, and methods abound,5 and drives prolific research on the subject, which is beyond the scope of this article. It has been demonstrated that there are a few “optimally aging” persons who avoid memory decline altogether.5,6 Most researchers and clinicians agree, however, that memory change is pervasive with advancing age.

Memory change follows a gradient with recent memories lost to a greater degree than remote memories (Ribot’s Law).7 Forgetfulness is characteristic of normal aging, and frequently manifests with misplaced objects and short-term lapses. However, this is not pathological—as long as the item or memory is recalled within 24 to 48 hours.

Compared with younger adults, healthy older adults are less efficient at encoding new information. Subsequently, they have more difficulty retrieving data, particularly after a delay. The time needed to learn and use new information increases, which is referred to as processing inefficiency. This influences changes in test performance across all cognitive domains, with decreases in measures of mental processing speed, working memory, and problem-solving.

Many patients who complain about “forgetfulness” are experiencing this normal change. It is not uncommon for a patient to offer a list of things she has forgotten recently, along with the dates and circumstances in which she forgot them. Because she sometimes forgets things, but remembers them later, there likely is nothing to worry about. If reminders—such as her list—help, this too is a good sign, because it shows her resourcefulness in using accommodations. If the patient is managing her normal activities, reassurance is warranted.

Mild cognitive impairment

Since at least 1958,8 clinical observations and research have recognized a prodrome that differentiates cognitive changes predictive of dementia from those that represent typical aging. Several studies and methods have converged toward consensus that MCI is a valid construct for that purpose, with ecological validity and sound predictive value. Clinical value is evident when a patient does not meet criteria for MCI; in this case, the clinician can reassure the worried well with conviction.

Revealing the diagnosis of MCI to patients requires sensitivity and assurance that you will reevaluate the condition annually. Although there is no evidence-based remedy for MCI or means to slow its progression to dementia, data are rapidly accruing regarding the value of lifestyle changes and other nonpharmacologic interventions.9

Recognizing MCI most simply requires 2 criteria:

The patient’s expressed concern about decline in cognitive functioning from a previous level of performance. Alternately, a caretaker’s report is valuable because the patient might lack insight. You are not looking for an inability to perform activities of daily living, which is indicative of frank dementia; rather, you want to determine whether the person’s independence in functional abilities is preserved, although less efficient. Patients might repeatedly report occurrences of new problems, although modest, in some cases. Although problems with memory often are the most frequently reported symptoms, changes can be observed in any cognitive domain. Uncharacteristic inability to understand instructions, frustration with new tasks, and inflexibility are common.

Quantified clinical assessment that the patient’s cognitive decline exceeds norms of his age cohort. Clinicians are already familiar with many of these tests (5-minute recall, clock face drawing, etc.). For MCI, we recommend the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), which is specifically designed for MCI.10 It takes only 10 minutes to administer. Multiple versions of the MoCA, and instructions for its administration are available for provider use at www.mocatest.org.

When these criteria are met—a decline in previous functioning and an objective clinical confirmation—referral for neuropsychological testing is recommended. Subtypes of MCI—amnestic and non-amnestic—have been employed to specify the subtype (amnesic) that is most consistent with prodromal AD. However, this dichotomous scheme does not adequately explain or capture the heterogeneity of MCI.11,12

Medical considerations

Just as all domains of cognition are correlated to some degree, the overall health status of a person influences evaluation of memory. Variables, such as fatigue, test anxiety, mood, motivation, visual and auditory acuity, education, language fluency, attention, and pain, affect test performance. In addition, clinician rapport and the manner in which tests are administered must be considered.

Depression can mimic MCI. A depressed patient often has poor expectations of himself and slowed thinking, and might exaggerate symptoms. He might give up on tests or refuse to complete them. His presentation initially could suggest cognitive decline, but depression is revealed when the clinician pays attention to vegetative signs (insomnia, poor appetite) or suicidal ideation. There is growing evidence that subjective complaints of memory loss are more frequently associated with depression than with objective measures of cognitive impairment.13,14

Other treatable conditions can present with cognitive change (the so-called reversible dementias). A deficiency of vitamin B12, thiamine, or folate often is seen because quality of nutrition generally decreases with age. Hyponatremia and dehydration can present with confusion and memory impairment. Other treatable conditions include:

- cerebral vasculitis, which could improve with immune suppressants

- endocrine diseases, which might respond to hormonal or surgical treatment

- normal pressure hydrocephalus, which can be relieved by surgical placement of a shunt.

Take a complete history. What exactly is the nature of the patient or caregiver’s complaint? You need to attempt to engage the patient in conversation, observing his behavior during the evaluation. Is there notable delay in response, difficulty in attention and focus, or in understanding questions?

The content of speech is an indicator of the patient’s information processing. Ask the patient to recite as many animals from the jungle as possible. Most people can come up with at least 15. The person with MCI will likely name fewer animals, but may respond well to cueing, and perform better in recognition (eg, pictures or drawings) vs retrieval. When asked to describe a typical day, the patient may offer a vague, nonchalant response eg, “I keep busy watching the news.” This kind of response may be evidence of confabulation; with further questioning, he is unable to identify current issues of interest.

Substance abuse. It is essential that clinicians recognize that elders are not exempt from alcohol and other drug abuse that affects cognition. Skilled history taking, including attention to non-verbal responses, is indicated. A defensive tone, rolling of eyes, or silent yet affirmative nodding are means by which caregivers offer essential “clues” to the provider.

A quick screening tool for the office is valuable; many clinicians are most familiar with the Mini-Mental State Examination or the Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination, which are known to be sensitive in detecting memory problems and other cognitive defects. As we noted, the MoCA is now recommended for differentiating more subtle changes of MCI.10,15 It is important to remember that common conditions such as an urinary tract infection or trauma after anesthesia for routine procedures such as colonoscopy can cause cognitive impairment. Again, eliciting history from a family member is valuable because the patient may have forgotten vital data.

A good physical exam is important when evaluating for dementia. Look for any neurologic anomaly. Check for disinhibition of primitive reflexes, eg, abnormal grasp or snout response or Babinski sign. Compare the symmetry and strength of deep tendon reflexes. Look for neurologic soft signs. Any pathological reflex response can be an important clue about neurodegeneration or space-occupying lesions. We recall seeing a 62-year-old man whose spouse brought him for evaluation for new-onset reckless driving and marked inattention to personal hygiene that developed over the previous 3 months. On examination, he appeared disheveled and had a dull affect, although disinhibited and careless. His mentation and gait were slowed. He denied distress of any kind. Frontal release signs were noted on exam. An MRI revealed a space-occupying lesion of the frontal lobe measuring 3 cm wide with a thickness of 2 cm, which pathology confirmed as a benign tumor.

Always check for arrhythmia and hypertension. These are significant risk factors for ischemic brain disease, multiple-infarct stroke, or other forms of vascular dementia. A shuffling gait suggests Parkinson’s disease, or even Lewy body dementia, or medication-related conditions, for example, from antipsychotics.