User login

Things We Do For No Reason: Two-Unit Red Cell Transfusions in Stable Anemic Patients

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is not only the most common procedure performed in US hospitals but is also widely overused, according to The Joint Commission. Unnecessary transfusions can increase risks and costs, and now, multiple landmark trials support using restrictive transfusion strategies. This manuscript discusses the importance and potential impacts of giving single-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in anemic patients who are not actively bleeding and are hemodynamically stable. The “thing we do for no reason” is giving 2-unit RBC transfusions when 1 unit would suffice. We call this the “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” campaign for RBC transfusion.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old, 70-kg male with a known history of myelodysplastic syndrome is admitted for dizziness and shortness of breath. His hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is 6.2 g/dL (baseline Hb of 8 g/dL). The patient denies any hematuria, hematemesis, and melena. Physical examination is remarkable only for tachycardia—heart rate of 110. The admitting hospitalist ponders whether to order a 2-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK DOUBLE UNIT RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSIONS ARE HELPFUL

RBC transfusion is the most common procedure performed in US hospitals, with about 12 million RBC units given to patients in the United States each year.1 Based on an opinion paper published in 1942 by Adams and Lundy2 the “10/30 rule” set the standard that the ideal transfusion thresholds were an Hb of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%. Until human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) became a threat to the nation’s blood supply in the early 1980s, few questioned the 10/30 rule. There is no doubt that blood transfusions can be lifesaving in the presence of active bleeding or hemorrhagic shock; in fact, many hospitals have blood donation campaigns reminding us to “give blood—save a life.” To some, these messages may suggest that more blood is better. Prior to the 1990s, clinicians were taught that if the patient needed an RBC transfusion, 2 units was the optimal dose for adult patients. In fact, single-unit transfusions were strongly discouraged, and authorities on the risks of transfusion wrote that single-unit transfusions were acknowledged to be unnecessary.3

WHY THERE IS “NO REASON” TO ROUTINELY ORDER DOUBLE UNIT TRANSFUSIONS

According to a recent Joint Commission Overuse Summit, transfusion was identified as 1 of the top 5 overused medical procedures.4 Blood transfusions can cause complications such as transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, the number 1 and 2 causes of transfusion-related deaths, respectively,5 as well as other transfusion reactions (eg, allergic and hemolytic) and alloimmunization. Transfusion-related morbidity and mortality have been shown to be dose dependent,6 suggesting that the lowest effective number of units should be transfused. Although, with modern-day testing, the risks of HIV and viral hepatitis are exceedingly low, emerging infectious diseases such as the Zika virus and Babesiosis represent new threats to the nation’s blood supply, with potential transfusion-related transmission and severe consequences, especially for the immunosuppressed. As quality-improvement, patient safety, and cost-saving initiatives, many hospitals have implemented strategies to reduce unnecessary transfusions and decrease overall blood utilization.

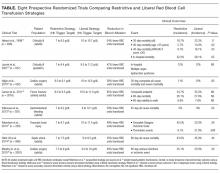

The above-mentioned studies support the concept that oftentimes less is more for transfusions, which includes giving the lowest effective amount of transfused blood. These trials have enrolled multiple patient populations, such as critically ill patients in the intensive care unit,11,13 elderly orthopedic surgery patients,14 cardiac surgery patients,12 and patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage,15 traumatic brain injury,17 and septicemia.16 Outcomes in the trials included mortality, serious infections, thrombotic and ischemic events, neurologic deficits, multiple-organ dysfunction, and inability to ambulate (Table). The findings in these studies suggest that we increase risks and cost without improving outcomes only by giving more blood than is necessary. Since most of these trials were published in the last decade, some very recently, clinicians have not fully adopted these newer, restrictive transfusion strategies.19

ARE THERE REASONS TO ORDER 2-UNIT TRANSFUSIONS IN CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES?

Perhaps the most common indication for ordering multiunit RBC transfusions is active bleeding, as it is clear that whatever Hb threshold is chosen, transfusion should be given in sufficient amounts to stay ahead of the bleeding.20 It is important to remember that we treat patients and their symptoms, not just their laboratory values. Good medical care adapts and/or modifies treatment protocols and guidelines according to the clinical situation. Intravascular volume is also important to consider because what really matters for oxygen content and delivery is the total red cell mass (ie, the Hb concentration times the blood volume). If a patient is hypovolemic and/or actively bleeding, the Hb transfusion trigger, as well as the dose of blood, may need to be adjusted upward, creating clinical scenarios in which 2-unit RBC transfusions may be appropriate. Other clinical settings for which multiunit RBC transfusions may be indicated include patients with severe anemia, for whom both the pretransfusion Hb (the trigger) and the posttransfusion Hb (the target) should be considered. Patients with hemoglobinopathies (eg, sickle cell or thalassemia) sometimes require multiunit transfusions or even exchange transfusions to improve oxygen delivery. Other patients who may benefit from higher Hb levels achieved by multiunit transfusions include those with acute coronary syndromes; however, the ideal Hb transfusion threshold in this setting has yet to be determined.21

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

For hemodynamically stable patients and in the absence of active bleeding, single-unit RBC transfusions, followed by reassessment, should be the standard for most patients. The reassessment should include measuring the posttransfusion Hb level and checking for improvement in vital sign abnormalities and signs or symptoms of anemia or end-organ ischemia. A recent publication on our hospital-wide campaign called “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” showed a significant (35%) reduction in 2-unit transfusion orders along with an 18% overall decrease in RBC utilization and substantial cost savings (≈$600,000 per year).10 These findings demonstrate that there is a large opportunity to reduce transfusion overuse by encouraging single-unit transfusions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For nonbleeding, hemodynamically stable patients who require a transfusion, transfuse a single RBC unit and then reassess the Hb level before transfusing a second unit.

- The decision to transfuse RBCs should take into account the patient’s overall condition, including their symptoms, intravascular volume, and the occurrence and rate of active bleeding, not just the Hb value alone.

CONCLUSIONS

In stable patients, a single unit of RBCs often is adequate to raise the Hb to an acceptable level and relieve the signs and symptoms of anemia. Additional units should be prescribed only after reassessment of the patient and the Hb level. For our patient with symptomatic anemia, it is reasonable to transfuse 1 RBC unit, and then measure the Hb level, and reassess his symptoms before giving additional RBC units.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Acknowledgments

This publication is dedicated to our beloved colleague, Dr. Rajiv N. Thakkar, who recently and unexpectedly suffered a fatal cardiac event. We will miss him dearly.

Disclosure

S.M.F. has been on advisory boards for the Haemonetics Corporation (Braintree, MA), Medtronic Inc. (Minneapolis, MN), and Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN). All other authors declare no competing interests.

1. Whitaker B, Rajbhandary S, Kleinman S, Harris A, Kamani N. Trends in United States blood collection and transfusion: results from the 2013 AABB Blood Collection, Utilization, and Patient Blood Management Survey. Transfusion. 2016;56:2173-2183. PubMed

2. Adams C, Lundy JS. Anesthesia in cases of poor surgical risk – Some suggestions for decreasing the risk. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1942;74:1011-1019.

3. Morton JH. An evaluation of blood-transfusion practices on a surgical service. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:1285-1287. PubMed

4. Pfunter A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb165.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2017.

5. Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogeneic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention. Blood. 2009;113:3406-3417. PubMed

6. Koch CG, Li L, Duncan AI, et al. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1608-1616. PubMed

7. Carson JL, Guyatt G, Heddle NM, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-2035. PubMed

8. Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:944-982. PubMed

9. Callum JL, Waters JH, Shaz BH, et al. The AABB recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Transfusion. 2014;54:2344-2352. PubMed

10. Podlasek SJ, Thakkar RN, Rotello LC, et al. Implementing a “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” Choosing Wisely campaign. Transfusion. 2016;56:2164. PubMed

11. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

12. Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: The TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567. PubMed

13. Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Hutchison JS, et al. Transfusion strategies for patients in pediatric intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1609-1619. PubMed

14. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462. PubMed

15. Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21. PubMed

16. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-1391. PubMed

17. Robertson CS, Hannay HJ, Yamal JM, et al. Effect of erythropoietin and transfusion threshold on neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:36-47. PubMed

18. Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:997-1008.

19. Meybohm P, Richards T, Isbister J, et al. Patient blood management bundles to facilitate implementation. Transfus Med Rev. 2017;31:62-71. PubMed

20. Frank SM, Resar LM, Rothschild JA, et al. A novel method of data analysis for utilization of red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion. 2013;53:3052-9. PubMed

21. Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, et al. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165:964.el-971.e1. PubMed

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is not only the most common procedure performed in US hospitals but is also widely overused, according to The Joint Commission. Unnecessary transfusions can increase risks and costs, and now, multiple landmark trials support using restrictive transfusion strategies. This manuscript discusses the importance and potential impacts of giving single-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in anemic patients who are not actively bleeding and are hemodynamically stable. The “thing we do for no reason” is giving 2-unit RBC transfusions when 1 unit would suffice. We call this the “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” campaign for RBC transfusion.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old, 70-kg male with a known history of myelodysplastic syndrome is admitted for dizziness and shortness of breath. His hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is 6.2 g/dL (baseline Hb of 8 g/dL). The patient denies any hematuria, hematemesis, and melena. Physical examination is remarkable only for tachycardia—heart rate of 110. The admitting hospitalist ponders whether to order a 2-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK DOUBLE UNIT RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSIONS ARE HELPFUL

RBC transfusion is the most common procedure performed in US hospitals, with about 12 million RBC units given to patients in the United States each year.1 Based on an opinion paper published in 1942 by Adams and Lundy2 the “10/30 rule” set the standard that the ideal transfusion thresholds were an Hb of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%. Until human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) became a threat to the nation’s blood supply in the early 1980s, few questioned the 10/30 rule. There is no doubt that blood transfusions can be lifesaving in the presence of active bleeding or hemorrhagic shock; in fact, many hospitals have blood donation campaigns reminding us to “give blood—save a life.” To some, these messages may suggest that more blood is better. Prior to the 1990s, clinicians were taught that if the patient needed an RBC transfusion, 2 units was the optimal dose for adult patients. In fact, single-unit transfusions were strongly discouraged, and authorities on the risks of transfusion wrote that single-unit transfusions were acknowledged to be unnecessary.3

WHY THERE IS “NO REASON” TO ROUTINELY ORDER DOUBLE UNIT TRANSFUSIONS

According to a recent Joint Commission Overuse Summit, transfusion was identified as 1 of the top 5 overused medical procedures.4 Blood transfusions can cause complications such as transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, the number 1 and 2 causes of transfusion-related deaths, respectively,5 as well as other transfusion reactions (eg, allergic and hemolytic) and alloimmunization. Transfusion-related morbidity and mortality have been shown to be dose dependent,6 suggesting that the lowest effective number of units should be transfused. Although, with modern-day testing, the risks of HIV and viral hepatitis are exceedingly low, emerging infectious diseases such as the Zika virus and Babesiosis represent new threats to the nation’s blood supply, with potential transfusion-related transmission and severe consequences, especially for the immunosuppressed. As quality-improvement, patient safety, and cost-saving initiatives, many hospitals have implemented strategies to reduce unnecessary transfusions and decrease overall blood utilization.

The above-mentioned studies support the concept that oftentimes less is more for transfusions, which includes giving the lowest effective amount of transfused blood. These trials have enrolled multiple patient populations, such as critically ill patients in the intensive care unit,11,13 elderly orthopedic surgery patients,14 cardiac surgery patients,12 and patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage,15 traumatic brain injury,17 and septicemia.16 Outcomes in the trials included mortality, serious infections, thrombotic and ischemic events, neurologic deficits, multiple-organ dysfunction, and inability to ambulate (Table). The findings in these studies suggest that we increase risks and cost without improving outcomes only by giving more blood than is necessary. Since most of these trials were published in the last decade, some very recently, clinicians have not fully adopted these newer, restrictive transfusion strategies.19

ARE THERE REASONS TO ORDER 2-UNIT TRANSFUSIONS IN CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES?

Perhaps the most common indication for ordering multiunit RBC transfusions is active bleeding, as it is clear that whatever Hb threshold is chosen, transfusion should be given in sufficient amounts to stay ahead of the bleeding.20 It is important to remember that we treat patients and their symptoms, not just their laboratory values. Good medical care adapts and/or modifies treatment protocols and guidelines according to the clinical situation. Intravascular volume is also important to consider because what really matters for oxygen content and delivery is the total red cell mass (ie, the Hb concentration times the blood volume). If a patient is hypovolemic and/or actively bleeding, the Hb transfusion trigger, as well as the dose of blood, may need to be adjusted upward, creating clinical scenarios in which 2-unit RBC transfusions may be appropriate. Other clinical settings for which multiunit RBC transfusions may be indicated include patients with severe anemia, for whom both the pretransfusion Hb (the trigger) and the posttransfusion Hb (the target) should be considered. Patients with hemoglobinopathies (eg, sickle cell or thalassemia) sometimes require multiunit transfusions or even exchange transfusions to improve oxygen delivery. Other patients who may benefit from higher Hb levels achieved by multiunit transfusions include those with acute coronary syndromes; however, the ideal Hb transfusion threshold in this setting has yet to be determined.21

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

For hemodynamically stable patients and in the absence of active bleeding, single-unit RBC transfusions, followed by reassessment, should be the standard for most patients. The reassessment should include measuring the posttransfusion Hb level and checking for improvement in vital sign abnormalities and signs or symptoms of anemia or end-organ ischemia. A recent publication on our hospital-wide campaign called “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” showed a significant (35%) reduction in 2-unit transfusion orders along with an 18% overall decrease in RBC utilization and substantial cost savings (≈$600,000 per year).10 These findings demonstrate that there is a large opportunity to reduce transfusion overuse by encouraging single-unit transfusions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For nonbleeding, hemodynamically stable patients who require a transfusion, transfuse a single RBC unit and then reassess the Hb level before transfusing a second unit.

- The decision to transfuse RBCs should take into account the patient’s overall condition, including their symptoms, intravascular volume, and the occurrence and rate of active bleeding, not just the Hb value alone.

CONCLUSIONS

In stable patients, a single unit of RBCs often is adequate to raise the Hb to an acceptable level and relieve the signs and symptoms of anemia. Additional units should be prescribed only after reassessment of the patient and the Hb level. For our patient with symptomatic anemia, it is reasonable to transfuse 1 RBC unit, and then measure the Hb level, and reassess his symptoms before giving additional RBC units.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Acknowledgments

This publication is dedicated to our beloved colleague, Dr. Rajiv N. Thakkar, who recently and unexpectedly suffered a fatal cardiac event. We will miss him dearly.

Disclosure

S.M.F. has been on advisory boards for the Haemonetics Corporation (Braintree, MA), Medtronic Inc. (Minneapolis, MN), and Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN). All other authors declare no competing interests.

The “Things We Do for No Reason” (TWDFNR) series reviews practices which have become common parts of hospital care but which may provide little value to our patients. Practices reviewed in the TWDFNR series do not represent “black and white” conclusions or clinical practice standards, but are meant as a starting place for research and active discussions among hospitalists and patients. We invite you to be part of that discussion. https://www.choosingwisely.org/

INTRODUCTION

Blood transfusion is not only the most common procedure performed in US hospitals but is also widely overused, according to The Joint Commission. Unnecessary transfusions can increase risks and costs, and now, multiple landmark trials support using restrictive transfusion strategies. This manuscript discusses the importance and potential impacts of giving single-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusions in anemic patients who are not actively bleeding and are hemodynamically stable. The “thing we do for no reason” is giving 2-unit RBC transfusions when 1 unit would suffice. We call this the “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” campaign for RBC transfusion.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 74-year-old, 70-kg male with a known history of myelodysplastic syndrome is admitted for dizziness and shortness of breath. His hemoglobin (Hb) concentration is 6.2 g/dL (baseline Hb of 8 g/dL). The patient denies any hematuria, hematemesis, and melena. Physical examination is remarkable only for tachycardia—heart rate of 110. The admitting hospitalist ponders whether to order a 2-unit red blood cell (RBC) transfusion.

WHY YOU MIGHT THINK DOUBLE UNIT RED BLOOD CELL TRANSFUSIONS ARE HELPFUL

RBC transfusion is the most common procedure performed in US hospitals, with about 12 million RBC units given to patients in the United States each year.1 Based on an opinion paper published in 1942 by Adams and Lundy2 the “10/30 rule” set the standard that the ideal transfusion thresholds were an Hb of 10 g/dL or a hematocrit of 30%. Until human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) became a threat to the nation’s blood supply in the early 1980s, few questioned the 10/30 rule. There is no doubt that blood transfusions can be lifesaving in the presence of active bleeding or hemorrhagic shock; in fact, many hospitals have blood donation campaigns reminding us to “give blood—save a life.” To some, these messages may suggest that more blood is better. Prior to the 1990s, clinicians were taught that if the patient needed an RBC transfusion, 2 units was the optimal dose for adult patients. In fact, single-unit transfusions were strongly discouraged, and authorities on the risks of transfusion wrote that single-unit transfusions were acknowledged to be unnecessary.3

WHY THERE IS “NO REASON” TO ROUTINELY ORDER DOUBLE UNIT TRANSFUSIONS

According to a recent Joint Commission Overuse Summit, transfusion was identified as 1 of the top 5 overused medical procedures.4 Blood transfusions can cause complications such as transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-associated circulatory overload, the number 1 and 2 causes of transfusion-related deaths, respectively,5 as well as other transfusion reactions (eg, allergic and hemolytic) and alloimmunization. Transfusion-related morbidity and mortality have been shown to be dose dependent,6 suggesting that the lowest effective number of units should be transfused. Although, with modern-day testing, the risks of HIV and viral hepatitis are exceedingly low, emerging infectious diseases such as the Zika virus and Babesiosis represent new threats to the nation’s blood supply, with potential transfusion-related transmission and severe consequences, especially for the immunosuppressed. As quality-improvement, patient safety, and cost-saving initiatives, many hospitals have implemented strategies to reduce unnecessary transfusions and decrease overall blood utilization.

The above-mentioned studies support the concept that oftentimes less is more for transfusions, which includes giving the lowest effective amount of transfused blood. These trials have enrolled multiple patient populations, such as critically ill patients in the intensive care unit,11,13 elderly orthopedic surgery patients,14 cardiac surgery patients,12 and patients with gastrointestinal hemorrhage,15 traumatic brain injury,17 and septicemia.16 Outcomes in the trials included mortality, serious infections, thrombotic and ischemic events, neurologic deficits, multiple-organ dysfunction, and inability to ambulate (Table). The findings in these studies suggest that we increase risks and cost without improving outcomes only by giving more blood than is necessary. Since most of these trials were published in the last decade, some very recently, clinicians have not fully adopted these newer, restrictive transfusion strategies.19

ARE THERE REASONS TO ORDER 2-UNIT TRANSFUSIONS IN CERTAIN CIRCUMSTANCES?

Perhaps the most common indication for ordering multiunit RBC transfusions is active bleeding, as it is clear that whatever Hb threshold is chosen, transfusion should be given in sufficient amounts to stay ahead of the bleeding.20 It is important to remember that we treat patients and their symptoms, not just their laboratory values. Good medical care adapts and/or modifies treatment protocols and guidelines according to the clinical situation. Intravascular volume is also important to consider because what really matters for oxygen content and delivery is the total red cell mass (ie, the Hb concentration times the blood volume). If a patient is hypovolemic and/or actively bleeding, the Hb transfusion trigger, as well as the dose of blood, may need to be adjusted upward, creating clinical scenarios in which 2-unit RBC transfusions may be appropriate. Other clinical settings for which multiunit RBC transfusions may be indicated include patients with severe anemia, for whom both the pretransfusion Hb (the trigger) and the posttransfusion Hb (the target) should be considered. Patients with hemoglobinopathies (eg, sickle cell or thalassemia) sometimes require multiunit transfusions or even exchange transfusions to improve oxygen delivery. Other patients who may benefit from higher Hb levels achieved by multiunit transfusions include those with acute coronary syndromes; however, the ideal Hb transfusion threshold in this setting has yet to be determined.21

WHAT YOU SHOULD DO INSTEAD

For hemodynamically stable patients and in the absence of active bleeding, single-unit RBC transfusions, followed by reassessment, should be the standard for most patients. The reassessment should include measuring the posttransfusion Hb level and checking for improvement in vital sign abnormalities and signs or symptoms of anemia or end-organ ischemia. A recent publication on our hospital-wide campaign called “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” showed a significant (35%) reduction in 2-unit transfusion orders along with an 18% overall decrease in RBC utilization and substantial cost savings (≈$600,000 per year).10 These findings demonstrate that there is a large opportunity to reduce transfusion overuse by encouraging single-unit transfusions.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- For nonbleeding, hemodynamically stable patients who require a transfusion, transfuse a single RBC unit and then reassess the Hb level before transfusing a second unit.

- The decision to transfuse RBCs should take into account the patient’s overall condition, including their symptoms, intravascular volume, and the occurrence and rate of active bleeding, not just the Hb value alone.

CONCLUSIONS

In stable patients, a single unit of RBCs often is adequate to raise the Hb to an acceptable level and relieve the signs and symptoms of anemia. Additional units should be prescribed only after reassessment of the patient and the Hb level. For our patient with symptomatic anemia, it is reasonable to transfuse 1 RBC unit, and then measure the Hb level, and reassess his symptoms before giving additional RBC units.

Do you think this is a low-value practice? Is this truly a “Thing We Do for No Reason?” Share what you do in your practice and join in the conversation online by retweeting it on Twitter (#TWDFNR) and liking it on Facebook. We invite you to propose ideas for other “Things We Do for No Reason” topics by emailing TWDFNR@hospitalmedicine.org.

Acknowledgments

This publication is dedicated to our beloved colleague, Dr. Rajiv N. Thakkar, who recently and unexpectedly suffered a fatal cardiac event. We will miss him dearly.

Disclosure

S.M.F. has been on advisory boards for the Haemonetics Corporation (Braintree, MA), Medtronic Inc. (Minneapolis, MN), and Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN). All other authors declare no competing interests.

1. Whitaker B, Rajbhandary S, Kleinman S, Harris A, Kamani N. Trends in United States blood collection and transfusion: results from the 2013 AABB Blood Collection, Utilization, and Patient Blood Management Survey. Transfusion. 2016;56:2173-2183. PubMed

2. Adams C, Lundy JS. Anesthesia in cases of poor surgical risk – Some suggestions for decreasing the risk. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1942;74:1011-1019.

3. Morton JH. An evaluation of blood-transfusion practices on a surgical service. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:1285-1287. PubMed

4. Pfunter A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb165.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2017.

5. Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogeneic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention. Blood. 2009;113:3406-3417. PubMed

6. Koch CG, Li L, Duncan AI, et al. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1608-1616. PubMed

7. Carson JL, Guyatt G, Heddle NM, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-2035. PubMed

8. Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:944-982. PubMed

9. Callum JL, Waters JH, Shaz BH, et al. The AABB recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Transfusion. 2014;54:2344-2352. PubMed

10. Podlasek SJ, Thakkar RN, Rotello LC, et al. Implementing a “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” Choosing Wisely campaign. Transfusion. 2016;56:2164. PubMed

11. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

12. Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: The TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567. PubMed

13. Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Hutchison JS, et al. Transfusion strategies for patients in pediatric intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1609-1619. PubMed

14. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462. PubMed

15. Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21. PubMed

16. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-1391. PubMed

17. Robertson CS, Hannay HJ, Yamal JM, et al. Effect of erythropoietin and transfusion threshold on neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:36-47. PubMed

18. Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:997-1008.

19. Meybohm P, Richards T, Isbister J, et al. Patient blood management bundles to facilitate implementation. Transfus Med Rev. 2017;31:62-71. PubMed

20. Frank SM, Resar LM, Rothschild JA, et al. A novel method of data analysis for utilization of red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion. 2013;53:3052-9. PubMed

21. Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, et al. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165:964.el-971.e1. PubMed

1. Whitaker B, Rajbhandary S, Kleinman S, Harris A, Kamani N. Trends in United States blood collection and transfusion: results from the 2013 AABB Blood Collection, Utilization, and Patient Blood Management Survey. Transfusion. 2016;56:2173-2183. PubMed

2. Adams C, Lundy JS. Anesthesia in cases of poor surgical risk – Some suggestions for decreasing the risk. Surg Gynec Obstet. 1942;74:1011-1019.

3. Morton JH. An evaluation of blood-transfusion practices on a surgical service. N Engl J Med. 1960;263:1285-1287. PubMed

4. Pfunter A, Wier LM, Stocks C. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb165.pdf. Accessed January 7, 2017.

5. Vamvakas EC, Blajchman MA. Transfusion-related mortality: the ongoing risks of allogeneic blood transfusion and the available strategies for their prevention. Blood. 2009;113:3406-3417. PubMed

6. Koch CG, Li L, Duncan AI, et al. Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1608-1616. PubMed

7. Carson JL, Guyatt G, Heddle NM, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines From the AABB: Red Blood Cell Transfusion Thresholds and Storage. JAMA. 2016;316:2025-2035. PubMed

8. Ferraris VA, Brown JR, Despotis GJ, et al. 2011 update to the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists blood conservation clinical practice guidelines. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:944-982. PubMed

9. Callum JL, Waters JH, Shaz BH, et al. The AABB recommendations for the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine. Transfusion. 2014;54:2344-2352. PubMed

10. Podlasek SJ, Thakkar RN, Rotello LC, et al. Implementing a “Why give 2 when 1 will do?” Choosing Wisely campaign. Transfusion. 2016;56:2164. PubMed

11. Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409-417. PubMed

12. Hajjar LA, Vincent JL, Galas FR, et al. Transfusion requirements after cardiac surgery: The TRACS randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1559-1567. PubMed

13. Lacroix J, Hebert PC, Hutchison JS, et al. Transfusion strategies for patients in pediatric intensive care units. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1609-1619. PubMed

14. Carson JL, Terrin ML, Noveck H, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion in high-risk patients after hip surgery. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2453-2462. PubMed

15. Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. New Engl J Med. 2013;368:11-21. PubMed

16. Holst LB, Haase N, Wetterslev J, et al. Lower versus higher hemoglobin threshold for transfusion in septic shock. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1381-1391. PubMed

17. Robertson CS, Hannay HJ, Yamal JM, et al. Effect of erythropoietin and transfusion threshold on neurological recovery after traumatic brain injury: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:36-47. PubMed

18. Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al. Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:997-1008.

19. Meybohm P, Richards T, Isbister J, et al. Patient blood management bundles to facilitate implementation. Transfus Med Rev. 2017;31:62-71. PubMed

20. Frank SM, Resar LM, Rothschild JA, et al. A novel method of data analysis for utilization of red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion. 2013;53:3052-9. PubMed

21. Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, et al. Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165:964.el-971.e1. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine