User login

Population Management of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an umbrella term that covers a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from nonalcoholic fatty liver or simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) defined by histologic findings of steatosis, lobular inflammation, cytologic ballooning, and some degree of fibrosis.1 While frequently observed in patients with at least 1 risk factor (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, hypertension), NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for type 2 DM (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease.2 At early disease stages with absence of liver fibrosis, mortality is linked to cardiovascular and not liver disease. However, in the presence of NASH, fibrosis progression to liver cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represent the most important liver-related outcomes that determine morbidity and mortality.3 Mirroring the obesity and T2DM epidemics, the health care burden is projected to dramatically rise.

In the following article, we will discuss how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is well positioned to implement an organizational strategy of comprehensive care for veterans with NAFLD. This comprehensive care strategy should include the development of a NAFLD clinic offering care for comorbid conditions frequently present in these patients, point-of-care testing, access to clinical trials, and outcomes monitoring as a key performance target for providers and the respective facility.

NAFLD disease burden

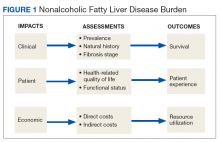

To fully appreciate the burden of a chronic disease like NAFLD, it is important to assess its long- and short-term consequences in a comprehensive manner with regard to its clinical impact, impact on the patient, and economic impact (Figure 1).

Clinical Impact

Clinical impact is assessed based on the prevalence and natural history of NAFLD and the liver fibrosis stage and determines patient survival. Coinciding with the epidemic of obesity and T2DM, the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population in North America is 24% and even higher with older age and higher body mass index (BMI).4,5 The prevalence for NAFLD is particularly high in patients with T2DM (47%). Of patients with T2DM and NAFLD, 65% have biopsy-proven NASH of which 15% have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis.6

NAFLD is the fastest growing cause of cirrhosis in the US with a forecasted NAFLD population of 101 million by 2030.7 At the same time, the number of patients with NASH will rise to 27 million of which > 7 million will have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis; hepatic decompensation events are estimated to occur in 105,430 patients with liver cirrhosis, posing a major public health threat related to organ availability for liver transplantation.8 Since 2013, NAFLD has been the second leading cause for liver transplantation and the top reason for transplantation in patients aged < 50 years.9,10 As many patients with NAFLD are diagnosed with HCC at stages where liver transplantation is not an option, mortality from HCC in NAFLD patients is higher than with other etiologies as treatment options are restricted.11,12

Compared with that of the general population, veterans seeking care are older and sicker with 43% of veterans taking > 5 prescribed medications.13 Of those receiving VHA care, 6.6 million veterans are either overweight or obese; 165,000 are morbidly obese with a BMI > 40.14 In addition, veterans are 2.5 times more likely to have T2DM compared with that of nonveterans. Because T2DM and obesity are the most common risk factors for NAFLD, it is not surprising that NAFLD prevalence among veterans rose 3-fold from 2003 to 2011.15 It is now estimated that 540,000 veterans will progress to NASH and 108,000 will develop bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis by 2030.8 Similar to that of the general population, liver cirrhosis is attributed to NAFLD in 15% of veterans.15,16 NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 years and 70 years, respectively.16,17 Shockingly, 20% of HCCs were not linked to liver cirrhosis and escaped recommended HCC screening for patients with cirrhosis.18,19

Patient Impact

Assessment of disease burden should not be restricted to clinical outcomes as patients can experience a range of symptoms that may have significant impact on their health-related quality of life (QOL) and functional status.20 Using general but not disease-specific instruments, NAFLD patients reported outcomes score low regarding fatigue, activity, and emotions.21 More disease-specific questionnaires may provide better and disease-specific insights as how NASH impacts patients’ QOL.22-24

Economic Impact

There is mounting evidence that the clinical implications of NAFLD directly influence the economic burden of NAFLD.25 The annual burden associated with all incident and prevalent NAFLD cases in the US has been estimated at $103 billion, and projections suggest that the expected 10-year burden of NAFLD may increase to $1.005 trillion.26 It is anticipated that increased NAFLD costs will affect the VHA with billions of dollars in annual expenditures in addition to the $1.5 billion already spent annually for T2DM care (4% of the VA pharmacy budget is spent on T2DM treatment).27-29

Current Patient Care

Obesity, DM, and dyslipidemia are common conditions managed by primary care providers (PCPs). Given the close association of these conditions with NAFLD, the PCP is often the first point of medical contact for patients with or at risk for NAFLD.30 For that reason, PCP awareness of NAFLD is critical for effective management of these patients. PCPs should be actively involved in the management of patients with NAFLD with pathways in place for identifying patients at high risk of liver disease for timely referral to a specialist and adequate education on the follow-up and treatment of low-risk patients. Instead, diagnosis of NAFLD is primarily triggered by either abnormal aminotransferases or detection of steatosis on imaging performed for other indications.

Barriers to optimal management of NAFLD by PCPs have been identified and occur at different levels of patient care. In the absence of clinical practice guidelines by the American Association of Family Practice covering NAFLD and a substantial latency period without signs of symptoms, NAFLD may not be perceived as a potentially serious condition by PCPs and their patients; interestingly this holds true even for some medical specialties.31-39 More than half of PCPs do not test their patients at highest risk for NAFLD (eg, patients with obesity or T2DM) and may be unaware of practice guidelines.40-42

Guidelines from Europe and the US are not completely in accordance. The US guidelines are vague regarding screening and are supported by only 1 medical society, due to the lack of NASH-specific drug therapies. The European guidelines are built on the support of 3 different stakeholders covering liver diseases, obesity, and DM and the experience using noninvasive liver fibrosis assessments for patients with NAFLD. To overcome this apparent conflict, a more practical and risk-stratified approach is warranted.41,42

Making the diagnosis can be challenging in cases with competing etiologies, such as T2DM and alcohol misuse. There also is an overreliance on aminotransferase levels to diagnose NAFLD. Significant liver disease can exist in the presence of normal aminotransferases, and this may be attributed to either spontaneous aminotransferase fluctuations or upper limits of normal that have been chosen too high.43-47 Often additional workup by PCPs depends on the magnitude of aminotransferase abnormalities.

Even if NAFLD has been diagnosed by PCPs, identifying those with NASH is hindered by the absence of an accurate noninvasive diagnostic method and the need to perform a liver biopsy. Liver biopsy is often not considered or delayed to monitor patients with serial aminotransferases, regardless of the patient’s metabolic comorbidity profile or baseline aminotransferases.32 As a result, referral to a specialist often depends on the magnitude of the aminotransferase abnormality,30,48 and often occurs when advanced liver disease is already present.49 Finally, providers may not be aware of beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions and certain medications, including statins on NASH and liver fibrosis.50-53 As NAFLD is associated with excess cardiovascular- and cancer-related morbidity and mortality, it is possible that regression of NAFLD may improve associated risk for these outcomes as well.

Framework for Comprehensive NAFLD Care

Chronic liver diseases and associated comorbidities have long been addressed by PCPs and specialty providers working in isolation and within the narrow focus of each discipline. Contrary to working in silos of the past, a coordinated management strategy with other disciplines that cover these comorbidities needs to be established, or alternatively the PCP must be aware of the management of comorbidities to execute them independently. Integration of hepatology-driven NAFLD care with other specialties involves communication, collaboration, and sharing of resources and expertise that will address patient care needs. Obviously, this cannot be undertaken in a single outpatient visit and requires vertical and longitudinal follow-up over time. One important aspect of comprehensive NAFLD care is the targeting of a particular patient population rather than being seen as a panacea for all; cost-utility analysis is hampered by uncertainties around accuracy of noninvasive biomarkers reflecting liver injury and a lack of effectiveness data for treatment. However, it seems reasonable to screen patients at high risk for NASH and adverse clinical outcomes. Such a risk stratification approach should be cost-effective.

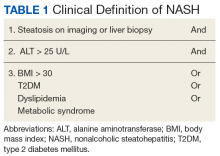

A first key step by the PCP is to identify whether a patient is at risk, especially patients with NASH. The majority of patients at risk are already seen by PCPs. While there is no consensus on ideal screening for NAFLD by PCPs, the use of ultrasound in the at-risk population is recommended in Europe.42 Although NASH remains a histopathologic diagnosis, a reasonable approach is to define NASH based on clinical criteria as done similarly in a real-world observational NAFLD cohort study.54 In the absence of chronic alcohol consumption and viral hepatitis and in a real-world scenario, NASH can be defined as steatosis shown on liver imaging or biopsy and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of > 25 U/L. In addition, ≥ 1 of the following criteria must be met: BMI > 30, T2DM, dyslipidemia, or metabolic syndrome (Table 1).

In the absence of easy-to-use validated tests, all patients with NAFLD need to be assessed with simple, noninvasive scores for the presence of clinically relevant liver fibrosis (F2-portal fibrosis with septa; F3-bridging fibrosis; F4-liver cirrhosis); those that meet the fibrosis criteria should receive further assessment usually only offered in a comprehensive NAFLD clinic.1 PCPs should focus on addressing 2 aspects related to NAFLD: (1) Does my patient have NASH based on clinical criteria; and (2) Is my patient at risk for clinically relevant liver fibrosis? PCPs are integral in optimal management of comorbidities and metabolic syndrome abnormalities with lifestyle and exercise interventions.

The care needs of a typical patient with NAFLD can be classified into 3 categories: liver disease (NAFLD) management, addressing NAFLD associated comorbidities, and attending to the personal care needs of the patient. With considerable interactions between these categories, interventions done within the framework of 1 category can influence the needs pertaining to another, requiring closer monitoring of the patient and potentially modifying care. For example, initiating a low carbohydrate diet in a patient with DM and NAFLD who is on antidiabetic medication may require adjusting the medication; disease progression or failure to achieve treatment goals may affect the emotional state of the patient, which can affect adherence.

Referrals to a comprehensive NAFLD clinic need to be standardized. Clearly, the referral process depends in part on local resources, comprehensiveness of available services, and patient characteristics, among others. Most often, PCPs refer patients with suspected diagnosis of NAFLD, with or without abnormal aminotransferases, to a hepatologist to confirm the diagnosis and for disease staging and liver disease management. This may have the advantage of greatest extent of access and should limit the number of patients with advanced liver fibrosis who otherwise may have been missed. On the other hand, different thresholds of PCPs for referrals may delay the patient’s access to comprehensive NAFLD care. Of those referred by primary care, the hepatologist identifies patients with NAFLD who benefit most from a comprehensive care approach. This automated referral process without predefined criteria remains more a vision than reality as it would require an infrastructure and resources that no health care system can provide currently.

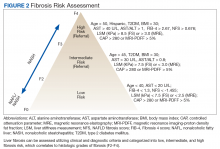

The alternative approach of automatic referral may use predefined criteria related to patients’ diagnoses and prognoses (Figure 2).

Patient-Centered Care

At present the narrow focus of VHA specialty outpatient clinics associated with time constraints of providers and gaps in NAFLD awareness clearly does not address the complex metabolic needs of veterans with NAFLD. This is in striking contrast to the comprehensive care offered to patients with cancer. To overcome these limitations, new care delivery models need to be explored. At first it seems attractive to embed NAFLD patient care geographically into a hepatology clinic with the potential advantages of improving volume and timeliness of referral and reinforcing communication among specialty providers while maximizing convenience for patients. However, this is resource intensive not only concerning clinic space, but also in terms of staffing clinics with specialty providers.

Patient-centered care for veterans with NAFLD seems to be best organized around a comprehensive NAFLD clinic with access to specialized diagnostics and knowledge in day-to-day NAFLD management. This evolving care concept has been developed already for patients with liver cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease and considers NAFLD a chronic disease that cannot be addressed sufficiently by providing episodic care.55,56 The development of comprehensive NAFLD care can build on the great success of the Hepatitis Innovation Team Collaborative that employed lean management strategies with local and regional teams to facilitate efforts to make chronic hepatitis C virus a rare disease in the VHA.57

NAFLD Care Team

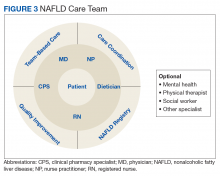

Given the central role of the liver and gastrointestinal tract in the field of nutrition, knowledge of the pathophysiology of the liver and digestive tract as well as emerging therapeutic options offered via metabolic endoscopy uniquely positions the hepatologist/gastroenterologist to take the lead in managing NAFLD. Treating NAFLD is best accomplished when the specialist partners with other health care providers who have expertise in the nutritional, behavioral, and physical activity aspects of treatment. The composition of the NAFLD care team and the roles that different providers fulfill can vary depending on the clinical setting; however, the hepatologist/gastroenterologist is best suited to lead the team, or alternatively, this role can be fulfilled by a provider with liver disease expertise.

Based on experiences from the United Kingdom, the minimum staffing of a NAFLD clinic should include a physician and nurse practitioner who has expertise in managing patients with chronic liver disease, a registered nurse, a dietitian, and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS).58 With coexistent diseases common and many veterans who have > 5 prescribed medications, risk of polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions are a concern, particularly since adherence in patients with chronic diseases has been reported to be as low as 43%.59-61 Risk of medication errors and serious adverse effects are magnified by difficulties with patient adherence, medication interactions, and potential need for frequent dose adjustments, particularly when on a weight-loss diet.

Without doubt, comprehensive medication management, offered by a highly trained CPS with independent prescriptive authority occurring while the veteran is in the NAFLD clinic, is highly desirable. Establishing a functional statement and care coordination agreement could describe the role of the CPS as a member of the NAFLD provider team.

Patient Evaluation

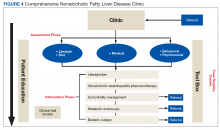

After being referred to the NAFLD clinic, the veteran should have a thorough assessment, including medical, nutritional, physical activity, exercise, and psychosocial evaluations (Figure 4).

The assessment also should include patient education to ensure that the patient has sufficient knowledge and skills to achieve the treatment goals. Educating on NAFLD is critical as most patients with NAFLD do not think of themselves as sick and have limited readiness for lifestyle changes.63,64 A better understanding of NAFLD combined with a higher self-efficacy seems to be positively linked to better nutritional habits.65

An online patient-reported outcomes measurement information system for a patient with NAFLD (eg, assessmentcenter.net) may be beneficial and can be applied within a routine NAFLD clinic visit because of its multidimensionality and compatibility with other chronic diseases.66-68 Other tools to assess health-related QOL include questionnaires, such as the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue, work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire: specific health problem, Short Form-36, and chronic liver disease questionnaire-NAFLD.23,69

The medical evaluation includes assessment of secondary causes of NAFLD and identification of NAFLD-related comorbidities. Weight, height, blood pressure, waist circumference, and BMI should be recorded. The physical exam should focus on signs of chronic liver disease and include inspection for acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, and large neck circumference, which are associated with insulin resistance, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea, respectively. NAFLD-associated comorbidities may contribute to frailty or physical limitations that affect treatment with diet and exercise and need to be assessed. A thorough medication reconciliation will reveal whether the patient is prescribed obesogenic medications and whether comorbidities (eg, DM and dyslipidemia) are being treated optimally and according to current society guidelines.

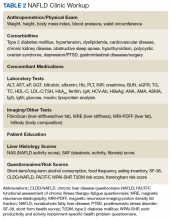

Making the diagnosis of NAFLD requires excluding other (concomitant) chronic liver diseases. While often this is done indirectly using order sets with a panoply of available serologic tests without accounting for risks for rare causes of liver injury, a more focused and cost-effective approach is warranted. As most patients will already have had imaging studies that show fatty liver, assessment of liver fibrosis is an important step for risk stratification. Noninvasive scores (eg, FIB-4) can be used by the PCP to identify high-risk patients requiring further workup and referral.1,70 More sophisticated tools, including transient elastography and/or magnetic resonance elastography are applied for more sophisticated risk stratification and liver disease management (Table 2).71

A nutritional evaluation includes information about eating behavior and food choices, body composition analysis, and an assessment of short- and long-term alcohol consumption. Presence of bilateral muscle wasting, subcutaneous fat loss, and signs of micronutrient deficiencies also should be explored. The lifestyle evaluation should include the patient’s typical physical activity and exercise as well as limiting factors.

Finally, and equally important, the patient’s psychosocial situation should be assessed, as motivation and accountability are key to success and may require behavioral modification. Assessing readiness is done best with motivational interviewing, the 5As counseling framework (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) or using open-ended questions, affirmation, reflections, and summaries.72,73 Even if not personally delivering behavioral treatment, such an approach also can help move patients toward addressing important health-related behaviors.

Personalized Interventions

If available, patients should be offered participation in NAFLD clinical trials. A personalized treatment plan should be developed for each patient with input from all NAFLD care team members. The patient and providers should work together to make important decisions about the treatment plan and goals of care. Making the patient an active participant in their treatment rather than the passive recipient will lead to improvement in adherence and outcomes. Patients will engage when they are comfortable speaking with providers and are sufficiently educated about their disease.

Personalized interventions may be built by combining different strategies, such as lifestyle and dietary interventions, NASH-specific pharmacotherapy, comorbidity management, metabolic endoscopy, and bariatric surgery. Although NASH-specific medications are not currently available, approved medications, including pioglitazone or liraglutide, can be considered for therapy.74,75 Ideally, the NAFLD team CPS would manage comorbidities, such as T2DM and dyslipidemia, but this also can be done by a hepatologist or other specialist. Metabolic endoscopy (eg, intragastric balloons) or bariatric surgery would be done by referral.

Resource-Limited Settings

Although the VHA offers care at > 150 medical centers and > 1,000 outpatient clinics, specialty care such as hepatology and sophisticated and novel testing modalities are not available at many facilities. In 2011 VHA launched the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes to bring hepatitis C therapy and liver transplantation evaluations to rural areas without specialists.76-78 It is logical to explore how telehealth can be used for NAFLD care that requires complex management using new treatments and has a high societal impact, particularly when left untreated.

Telehealth must be easy to use and integrated into everyday routines to be useful for NAFLD management by addressing different aspects of promoting self-management, optimizing therapy, and care coordination. Participation in a structured face-to-face or group-based lifestyle program is often jeopardized by time and job constraints but can be successfully overcome using online approaches.79 The Internet-based VA Video Connect videoconferencing, which incorporates cell phone, laptop, or tablet use could help expand lifestyle interventions to a much larger community of patients with NAFLD and overcome local resource constraints. Finally, e-consultation also can be used in circumstances where synchronous communication with specialists may not be necessary.

Patient Monitoring and Quality Metrics

Monitoring of the patient after initiation of an intervention is variable but occurs more frequently at the beginning. For high-intensity dietary interventions, weekly monitoring for the first several weeks can ensure ongoing motivation, and accountability may increase the patient’s confidence and provide encouragement for further weight loss. It also is an opportunity to reestablish goals with patients with declining motivation. Long-term monitoring of patients may occur in 6- to 12-month intervals to document patient-reported outcomes, liver-related mortality, cardiovascular events, malignancies, and disease progression or regression.

While quality indicators have been proposed for cirrhosis care, such indicators have yet to be defined for NALD care.80 Such quality indicators assessed with validated questionnaires should include knowledge about NAFLD, satisfaction with care, perception of quality of care, and patient-reported outcomes. Other indicators may include use of therapies to treat dyslipidemia and T2DM. Last and likely the most important indicator of improved liver health in NAFLD will be either histologic improvement of NASH or improvement of the fibrosis risk category.

Outlook

With the enormous burden of NAFLD on the rise for many more years to come, quality care delivered to patients with NAFLD warrants resource-adaptive population health management strategies. With a limited number of providers specialized in liver disease, provider education assisted by clinical guidelines and decision support tools, development of referral and access to care mechanisms through integrated care, remote monitoring strategies as well as development of patient self-management and community resources will become more important. We have outlined essential components of an effective population health management strategy for NAFLD and actionable items for the VHA to consider when implementing these strategies. This is the time for the VHA to invest in efforts for NAFLD population care. Clearly, consideration must be given to local needs and resources and integration of technology platforms. Addressing NAFLD at a population level will provide yet another opportunity to demonstrate that VHA performs better on quality when compared with care systems in the private sector.81

1. Hunt CM, Turner MJ, Gifford EJ, Britt RB, Su GL. Identifying and treating nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Fed Pract. 2019;36(1):20-29.

2. Glass LM, Hunt CM, Fuchs M, Su GL. Comorbidities and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: the chicken, the egg, or both? Fed Pract. 2019;36(2):64-71.

3. Vilar-Gomez E, Calzadilla-Bertot L, Wai-Sun Wong V, et al. Fibrosis severity as a determinant of cause-specific mortality in patients with advanced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a multi-national cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(2):443-457.e17.

4. Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73-84.

5. Yki-Järvinen H. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease as a cause and a consequence of metabolic syndrome. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(11):901-910.

6. Golabi P, Shahab O, Stepanova M, Sayiner M, Clement SC, Younossi ZM. Long-term outcomes of diabetic patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [abstract]. Hepatology. 2017;66(suppl 1):1142A-1143A.

7. Wong RJ, Cheung R, Ahmed A. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the most rapidly growing indication for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in the U.S. Hepatology. 2014;59(6):2188-2195.

8. Estes C, Razavi H, Loomba R, Younossi Z, Sanyal AJ. Modeling the epidemic of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease demonstrates an exponential increase in burden of disease. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):123-133.

9. Wong RJ, Aguilar M, Cheung R, et al. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is the second leading etiology of liver disease among adults awaiting liver transplantation in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2015;148(3):547-555.

10. Banini B, Mota M, Behnke M, Sharma A, Sanyal AJ. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) has surpassed hepatitis C as the leading cause for listing for liver transplant: implications for NASH in children and young adults. Presented at the American College of Gastroenterology Annual Scientific Meeting, Las Vegas, NV, October 18, 2016. Abstract 46. https://www.eventscribe.com/2016/ACG/QRcode.asp?Pres=199366. Accessed January 15, 2019.

11. Bruix J, Sherman M; American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53(3):1020-1022.

12. Younossi ZM, Otgonsuren M, Henry L, et al. Association of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in the United States from 2004-2009. Hepatology. 2015;62(6):1723-1730.

13. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. The obesity epidemic in the Veterans Health Administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):11-17.

14. Gunnar W. Bariatric surgery provided by the Veterans Health Administration: current state and a look to the future. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(suppl 1):4-5.

15. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Duan Z, Yu X, White D, El-Seraq HB. Trends in the burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in a United States cohort of veterans. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(2):301-308.e1-2.

16. Goldberg D, Ditah IC, Saeian K, et al. Changes in the prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and alcoholic liver disease among patients with cirrhosis or liver failure on the wait list for liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(5):1090-1099.e1.

17. Beste L, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.e5.

18. Mittal S, El-Seraq HB, Sada YH, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the absence of cirrhosis in United States veterans is associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(1):124-131.

19. Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Mapakshi S, et al. Risk of hepatocellular cancer in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;55(6):1828-1837.e2.

20. David K, Kowdley KV, Unalp A, Kanwal F, Brunt EM, Schwimmer JB; NASH CRN Research Group. Quality of life in adults with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: baseline data from the nonalcoholic steatohepatitis clinical research network. Hepatology. 2009;49(6):1904-1912.

21. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L. Performance and validation of Chronic Liver Disease Questionnaire-Hepatitis C Version (CLDQ-HCV) in clinical trials of patients with chronic hepatitis C. Value Health. 2016;19(5):544-551.

22. Younossi ZM, Henry L. Economic and quality-of-life implications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(12):1245-1253.

23. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Henry L, et al. A disease-specific quality of life instrument for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis: CLDQ-NAFLD. Liver Int. 2017;37(8):1209-1218.

24. Chawla KS, Talwalkar JA, Keach JC, Malinchoc M, Lindor KD, Jorgensen R. Reliability and validity of the chronic liver disease questionnaire (CLDQ) in adults with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000069.

25. Shetty A, Syn WK. Health, and economic burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in the United States and its impact on Veterans. Fed Pract. 2019;36(1):14-19.

26. Younossi ZM, Blissett D, Blissett R, et al. The economic and clinical burden of nonalcoholic liver disease in the United States and Europe. Hepatology. 2016;64(5):1577-1586.

27. Younossi ZM, Tampi R, Priyadarshini M, Nader F, Younossi IM, Racila A. Burden of illness and economic model for patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in the United States. Hepatology. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

28. Allen AM, van Houten HK, Sangaralingham LR, Talwalkar JA, McCoy RG. Healthcare cost and utilization in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: real-world data from a large U.S. claims database. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2230-2238.

29. Diabetes mellitus. http://www.fedprac-digital.com/federalpractitioner/data_trends_2017?pg=20#pg20. Published July 2017. Accessed January 15, 2019.

30. Grattagliano I, D’Ambrosio G, Palmieri VO, Moschetta A, Palasciano G, Portincasa P; “Steatostop Project” Group. Improving nonalcoholic fatty liver disease management by general practitioners: a critical evaluation and impact of an educational training program. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2008;17(4):389-394.

31. Polanco-Briceno S, Glass D, Stuntz M, Caze A. Awareness of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and associated practice patterns of primary care physicians and specialists. BMC Res Notes. 2016;9:157.

32. Patel PJ, Banh X, Horsfall LU, et al. Underappreciation of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by primary care clinicians: limited awareness of surrogate markers of fibrosis. Intern Med. 2018;48(2):144-151.

33. Standing HC, Jarvis H, Orr J, et al. GPs’ experiences and perceptions of early detection of liver disease: a qualitative study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(676):e743-e749.

34. Wieland AC, Quallick M, Truesdale A, Mettler P, Bambha KM. Identifying practice gaps to optimize medical care for patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58(10):2809-2816.

35. Alexander M, Loomis AK, Fairburn-Beech J, et al. Real-world data reveal a diagnostic gap in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):130.

36. Ratziu V, Cadranel JF, Serfaty L, et al. A survey of patterns of practice and perception of NAFLD in a large sample of practicing gastroenterologists in France. J Hepatol. 2012;57(2):376-383.

37. Blais P, Husain N, Kramer JR, Kowalkowski M, El-Seraq H, Kanwal F. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is underrecognized in the primary care setting. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110(1):10-14.

38. Bergqvist CJ, Skoien R, Horsfall L, Clouston AD, Jonsson JR, Powell EE. Awareness and opinions of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease by hospital specialists. Intern Med J. 2013;43(3):247-253.

39. Said A, Gagovic V, Malecki K, Givens ML, Nieto FJ. Primary care practitioners survey of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Ann Hepatol. 2013;12(5):758-765.

40. Chalasani N, Younossi Z, Lavine JE, et al. The diagnosis and management of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: practice guidance from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2018;67(1):328-357.

41. NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD): assessment and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng49. Published July 2016. Accessed January 15, 2019.

42. European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), European Association for the Study of diabetes (EASD), European Association for the study of obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2016;64(6):1388-1402.

43. Mofrad P, Contos MJ, Haque M, et al. Clinical and histologic spectrum of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease associated with normal ALT values. Hepatology. 2003;37(6):1286-1292.

44. Koehler EM, Plompen EP, Schouten JN, et al. Presence of diabetes mellitus and steatosis is associated with liver stiffness in a general population: the Rotterdam study. Hepatology. 2016;63(1):138-147.

45. Kwok R, Choi KC, Wong GL, et al. Screening diabetic patients for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with controlled attenuation parameter and liver stiffness measurements: a prospective cohort study. Gut. 2016;65(8):1359-1368.

46. Harman DJ, Ryder SD, James MW, et al. Obesity and type 2 diabetes are important risk factors underlying previously undiagnosed cirrhosis in general practice: a cross-sectional study using transient elastography. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(4):504-515.

47. Prati D, Taioli E, Zanella A, et al. Updated definitions of healthy ranges for serum alanine aminotransferase levels. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(1):1-10.

48. Rinella ME, Lominadze Z, Loomba R, et al. Practice pattern in NAFLD and NASH: real life differs from published guidelines. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9(1):4-12.

49. El-Atem NA, Wojcik K, Horsfall L, et al. Patterns of service utilization within Australian hepatology clinics: high prevalence of advanced liver disease. Intern Med. 2016;46(4):420-426.

50. Dongiovanni P, Petta S, Mannisto V, et al. Statin use and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in at risk individuals. J Hepatol. 2015;63(3):705-712.

51. Nascimbeni F, Aron-Wisnewsky J, Pais R, et al; LIDO Study Group. Statins, antidiabetic medications and liver histology in patients with diabetes with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. BMJ Open Gastroenterol. 2016;3(1):e000075.

52. Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Trenell M. Treatment of NAFLD with diet, physical activity and exercise. J Hepatol. 2017;67(4):829-846.

53. Vilar-Gomez E, Martinez-Perez Y, Calzadilla-Bertot L, et al. Weight loss through lifestyle modification significantly reduces features of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(2):367-378.

54. Barritt AS 4th, Gitlin N, Klein S, et al. Design and rationale for a real-world observational cohort of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: The TARGET-NASH study. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017;61:33-38.

55. Meier SK, Shah ND, Talwalkar JA. Adapting the patient-centered specialty practice model for populations with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14(4):492-496.

56. Dulai PS, Singh S, Ohno-Machado L, Sandborn WJ. Population health management for inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(1):37-45.

57. Park A, Gonzalez R, Chartier M, et al. Screening and treating hepatitis C in the VA: achieving excellence using lean and system redesign. Fed Pract. 2018;35(7):24-29.

58. Cobbold JFL, Raveendran S, Peake CM, Anstee QM, Yee MS, Thursz MR. Piloting a multidisciplinary clinic for the management of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: initial 5-year experience. Frontline Gastroenterol. 2013;4(4):263-269.

59. Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):487-497.

60. Harrison SA. NASH, from diagnosis to treatment: where do we stand? Hepatology. 2015;62(6):1652-1655.

61. Patel PJ, Hayward KL, Rudra R, et al. Multimorbidity and polypharmacy in diabetic patients with NAFLD: implications for disease severity and management. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017;96(26):e6761.

62. Kanwal F, Mapashki S, Smith D, et al. Implementation of a population-based cirrhosis identification and management system. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(8):1182-1186.e2.

63. Mlynarski L, Schlesinger D, Lotan R, et al. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not associated with a lower health perception. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22(17):4362-4372.

64. Centis E, Moscatiello S, Bugianesi E, et al. Stage of change and motivation to healthier lifestyle in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58(4):771-777.

65. Zelber-Sagi S, Bord S, Dror-Lavi G, et al. Role of illness perception and self-efficacy in lifestyle modification among non-alcoholic fatty liver disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(10):1881-1890.

66. Bajaj JS, Thacker LR, Wade JB, et al. PROMIS computerized adaptive tests are dynamic instruments to measure health-related quality of life in patients with cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(9):1123-1132.

67. Verma M, Stites S, Navarro V. Bringing assessment of patient-reported outcomes to hepatology practice. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(3):447-448.

68. Ahmed S, Ware P, Gardner W, et al. Montreal Accord on patient-reported outcomes (PROs) use series – paper 8: patient-reported outcomes in electronic health records can inform clinical and policy decisions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;89:160-167.

69. Younossi ZM, Stepanova M, Lawitz E, et al. Improvement of hepatic fibrosis and patient-reported outcomes in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis treated with selonsertib. Liver Int. 2018;38(10):1849-1859.

70. Patel YA, Gifford EJ, Glass LM, et al. Identifying nonalcoholic fatty liver disease advanced fibrosis in the Veterans Health Administration. Dig Dis Sci. 2018;63(9):2259-2266.

71. Hsu C, Caussy C, Imajo K, et al. Magnetic resonance vs transient elastography analysis of patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a systematic review and pooled analysis of individual participants. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;pii:S1542-3565(18)30613-X. [Epub ahead of print.]

72. Searight R. Realistic approaches to counseling in the office setting. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(4):277-284.

73. Vallis M, Piccinini-Vallis H, Sharma AM, Freedhoff Y. Clinical review: modified 5 As: minimal intervention for obesity counseling in primary care. Can Fam Physician. 2013:59(1):27-31.

74. Cusi K, Orsak B, Bril F, et al. Long-term pioglitazone treatment for patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(5):305-315.

75. Armstrong MJ, Gaunt P, Aithal GP, et al. Liraglutide safety and efficacy in patients with non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (LEAN): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 2 study. Lancet. 2016;387(10019):679-690.

76. Salgia RJ, Mullan PB, McCurdy H, Sales A, Moseley RH, Su GL. The educational impact of the specialty care access network-extension of community healthcare outcomes program. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20(11):1004-1008.

77. Konjeti VR, Heuman D, Bajaj J, et al. Telehealth-based evaluation identifies patients who are not candidates for liver transplantation. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(1):207-209.e1

78. Su GL, Glass L, Tapper EB, Van T, Waljee AK, Sales AE. Virtual consultations through the Veterans Administration SCAN-ECHO project improves survival for veterans with liver disease. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2317-2324.

79. Mazzotti A, Caletti MT, Brodosi L, et al. An internet-based approach for lifestyle changes in patients with NAFLD: two-year effects on weight loss and surrogate markers. J Hepatol. 2018;69(5):1155-1163.

80. Kanwal F, Kramer J, Asch SM, et al. An explicit quality indicator set for measurement of quality of care in patients with cirrhosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010,8(8):709-717.

81. Blay E Jr, DeLancey JO, Hewitt DB, Chung JW, Bilimoria KY. Initial public reporting of quality at Veterans Affairs vs Non-Veterans Affairs hospitals. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(6):882-885.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an umbrella term that covers a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from nonalcoholic fatty liver or simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) defined by histologic findings of steatosis, lobular inflammation, cytologic ballooning, and some degree of fibrosis.1 While frequently observed in patients with at least 1 risk factor (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, hypertension), NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for type 2 DM (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease.2 At early disease stages with absence of liver fibrosis, mortality is linked to cardiovascular and not liver disease. However, in the presence of NASH, fibrosis progression to liver cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represent the most important liver-related outcomes that determine morbidity and mortality.3 Mirroring the obesity and T2DM epidemics, the health care burden is projected to dramatically rise.

In the following article, we will discuss how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is well positioned to implement an organizational strategy of comprehensive care for veterans with NAFLD. This comprehensive care strategy should include the development of a NAFLD clinic offering care for comorbid conditions frequently present in these patients, point-of-care testing, access to clinical trials, and outcomes monitoring as a key performance target for providers and the respective facility.

NAFLD disease burden

To fully appreciate the burden of a chronic disease like NAFLD, it is important to assess its long- and short-term consequences in a comprehensive manner with regard to its clinical impact, impact on the patient, and economic impact (Figure 1).

Clinical Impact

Clinical impact is assessed based on the prevalence and natural history of NAFLD and the liver fibrosis stage and determines patient survival. Coinciding with the epidemic of obesity and T2DM, the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population in North America is 24% and even higher with older age and higher body mass index (BMI).4,5 The prevalence for NAFLD is particularly high in patients with T2DM (47%). Of patients with T2DM and NAFLD, 65% have biopsy-proven NASH of which 15% have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis.6

NAFLD is the fastest growing cause of cirrhosis in the US with a forecasted NAFLD population of 101 million by 2030.7 At the same time, the number of patients with NASH will rise to 27 million of which > 7 million will have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis; hepatic decompensation events are estimated to occur in 105,430 patients with liver cirrhosis, posing a major public health threat related to organ availability for liver transplantation.8 Since 2013, NAFLD has been the second leading cause for liver transplantation and the top reason for transplantation in patients aged < 50 years.9,10 As many patients with NAFLD are diagnosed with HCC at stages where liver transplantation is not an option, mortality from HCC in NAFLD patients is higher than with other etiologies as treatment options are restricted.11,12

Compared with that of the general population, veterans seeking care are older and sicker with 43% of veterans taking > 5 prescribed medications.13 Of those receiving VHA care, 6.6 million veterans are either overweight or obese; 165,000 are morbidly obese with a BMI > 40.14 In addition, veterans are 2.5 times more likely to have T2DM compared with that of nonveterans. Because T2DM and obesity are the most common risk factors for NAFLD, it is not surprising that NAFLD prevalence among veterans rose 3-fold from 2003 to 2011.15 It is now estimated that 540,000 veterans will progress to NASH and 108,000 will develop bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis by 2030.8 Similar to that of the general population, liver cirrhosis is attributed to NAFLD in 15% of veterans.15,16 NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 years and 70 years, respectively.16,17 Shockingly, 20% of HCCs were not linked to liver cirrhosis and escaped recommended HCC screening for patients with cirrhosis.18,19

Patient Impact

Assessment of disease burden should not be restricted to clinical outcomes as patients can experience a range of symptoms that may have significant impact on their health-related quality of life (QOL) and functional status.20 Using general but not disease-specific instruments, NAFLD patients reported outcomes score low regarding fatigue, activity, and emotions.21 More disease-specific questionnaires may provide better and disease-specific insights as how NASH impacts patients’ QOL.22-24

Economic Impact

There is mounting evidence that the clinical implications of NAFLD directly influence the economic burden of NAFLD.25 The annual burden associated with all incident and prevalent NAFLD cases in the US has been estimated at $103 billion, and projections suggest that the expected 10-year burden of NAFLD may increase to $1.005 trillion.26 It is anticipated that increased NAFLD costs will affect the VHA with billions of dollars in annual expenditures in addition to the $1.5 billion already spent annually for T2DM care (4% of the VA pharmacy budget is spent on T2DM treatment).27-29

Current Patient Care

Obesity, DM, and dyslipidemia are common conditions managed by primary care providers (PCPs). Given the close association of these conditions with NAFLD, the PCP is often the first point of medical contact for patients with or at risk for NAFLD.30 For that reason, PCP awareness of NAFLD is critical for effective management of these patients. PCPs should be actively involved in the management of patients with NAFLD with pathways in place for identifying patients at high risk of liver disease for timely referral to a specialist and adequate education on the follow-up and treatment of low-risk patients. Instead, diagnosis of NAFLD is primarily triggered by either abnormal aminotransferases or detection of steatosis on imaging performed for other indications.

Barriers to optimal management of NAFLD by PCPs have been identified and occur at different levels of patient care. In the absence of clinical practice guidelines by the American Association of Family Practice covering NAFLD and a substantial latency period without signs of symptoms, NAFLD may not be perceived as a potentially serious condition by PCPs and their patients; interestingly this holds true even for some medical specialties.31-39 More than half of PCPs do not test their patients at highest risk for NAFLD (eg, patients with obesity or T2DM) and may be unaware of practice guidelines.40-42

Guidelines from Europe and the US are not completely in accordance. The US guidelines are vague regarding screening and are supported by only 1 medical society, due to the lack of NASH-specific drug therapies. The European guidelines are built on the support of 3 different stakeholders covering liver diseases, obesity, and DM and the experience using noninvasive liver fibrosis assessments for patients with NAFLD. To overcome this apparent conflict, a more practical and risk-stratified approach is warranted.41,42

Making the diagnosis can be challenging in cases with competing etiologies, such as T2DM and alcohol misuse. There also is an overreliance on aminotransferase levels to diagnose NAFLD. Significant liver disease can exist in the presence of normal aminotransferases, and this may be attributed to either spontaneous aminotransferase fluctuations or upper limits of normal that have been chosen too high.43-47 Often additional workup by PCPs depends on the magnitude of aminotransferase abnormalities.

Even if NAFLD has been diagnosed by PCPs, identifying those with NASH is hindered by the absence of an accurate noninvasive diagnostic method and the need to perform a liver biopsy. Liver biopsy is often not considered or delayed to monitor patients with serial aminotransferases, regardless of the patient’s metabolic comorbidity profile or baseline aminotransferases.32 As a result, referral to a specialist often depends on the magnitude of the aminotransferase abnormality,30,48 and often occurs when advanced liver disease is already present.49 Finally, providers may not be aware of beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions and certain medications, including statins on NASH and liver fibrosis.50-53 As NAFLD is associated with excess cardiovascular- and cancer-related morbidity and mortality, it is possible that regression of NAFLD may improve associated risk for these outcomes as well.

Framework for Comprehensive NAFLD Care

Chronic liver diseases and associated comorbidities have long been addressed by PCPs and specialty providers working in isolation and within the narrow focus of each discipline. Contrary to working in silos of the past, a coordinated management strategy with other disciplines that cover these comorbidities needs to be established, or alternatively the PCP must be aware of the management of comorbidities to execute them independently. Integration of hepatology-driven NAFLD care with other specialties involves communication, collaboration, and sharing of resources and expertise that will address patient care needs. Obviously, this cannot be undertaken in a single outpatient visit and requires vertical and longitudinal follow-up over time. One important aspect of comprehensive NAFLD care is the targeting of a particular patient population rather than being seen as a panacea for all; cost-utility analysis is hampered by uncertainties around accuracy of noninvasive biomarkers reflecting liver injury and a lack of effectiveness data for treatment. However, it seems reasonable to screen patients at high risk for NASH and adverse clinical outcomes. Such a risk stratification approach should be cost-effective.

A first key step by the PCP is to identify whether a patient is at risk, especially patients with NASH. The majority of patients at risk are already seen by PCPs. While there is no consensus on ideal screening for NAFLD by PCPs, the use of ultrasound in the at-risk population is recommended in Europe.42 Although NASH remains a histopathologic diagnosis, a reasonable approach is to define NASH based on clinical criteria as done similarly in a real-world observational NAFLD cohort study.54 In the absence of chronic alcohol consumption and viral hepatitis and in a real-world scenario, NASH can be defined as steatosis shown on liver imaging or biopsy and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of > 25 U/L. In addition, ≥ 1 of the following criteria must be met: BMI > 30, T2DM, dyslipidemia, or metabolic syndrome (Table 1).

In the absence of easy-to-use validated tests, all patients with NAFLD need to be assessed with simple, noninvasive scores for the presence of clinically relevant liver fibrosis (F2-portal fibrosis with septa; F3-bridging fibrosis; F4-liver cirrhosis); those that meet the fibrosis criteria should receive further assessment usually only offered in a comprehensive NAFLD clinic.1 PCPs should focus on addressing 2 aspects related to NAFLD: (1) Does my patient have NASH based on clinical criteria; and (2) Is my patient at risk for clinically relevant liver fibrosis? PCPs are integral in optimal management of comorbidities and metabolic syndrome abnormalities with lifestyle and exercise interventions.

The care needs of a typical patient with NAFLD can be classified into 3 categories: liver disease (NAFLD) management, addressing NAFLD associated comorbidities, and attending to the personal care needs of the patient. With considerable interactions between these categories, interventions done within the framework of 1 category can influence the needs pertaining to another, requiring closer monitoring of the patient and potentially modifying care. For example, initiating a low carbohydrate diet in a patient with DM and NAFLD who is on antidiabetic medication may require adjusting the medication; disease progression or failure to achieve treatment goals may affect the emotional state of the patient, which can affect adherence.

Referrals to a comprehensive NAFLD clinic need to be standardized. Clearly, the referral process depends in part on local resources, comprehensiveness of available services, and patient characteristics, among others. Most often, PCPs refer patients with suspected diagnosis of NAFLD, with or without abnormal aminotransferases, to a hepatologist to confirm the diagnosis and for disease staging and liver disease management. This may have the advantage of greatest extent of access and should limit the number of patients with advanced liver fibrosis who otherwise may have been missed. On the other hand, different thresholds of PCPs for referrals may delay the patient’s access to comprehensive NAFLD care. Of those referred by primary care, the hepatologist identifies patients with NAFLD who benefit most from a comprehensive care approach. This automated referral process without predefined criteria remains more a vision than reality as it would require an infrastructure and resources that no health care system can provide currently.

The alternative approach of automatic referral may use predefined criteria related to patients’ diagnoses and prognoses (Figure 2).

Patient-Centered Care

At present the narrow focus of VHA specialty outpatient clinics associated with time constraints of providers and gaps in NAFLD awareness clearly does not address the complex metabolic needs of veterans with NAFLD. This is in striking contrast to the comprehensive care offered to patients with cancer. To overcome these limitations, new care delivery models need to be explored. At first it seems attractive to embed NAFLD patient care geographically into a hepatology clinic with the potential advantages of improving volume and timeliness of referral and reinforcing communication among specialty providers while maximizing convenience for patients. However, this is resource intensive not only concerning clinic space, but also in terms of staffing clinics with specialty providers.

Patient-centered care for veterans with NAFLD seems to be best organized around a comprehensive NAFLD clinic with access to specialized diagnostics and knowledge in day-to-day NAFLD management. This evolving care concept has been developed already for patients with liver cirrhosis and inflammatory bowel disease and considers NAFLD a chronic disease that cannot be addressed sufficiently by providing episodic care.55,56 The development of comprehensive NAFLD care can build on the great success of the Hepatitis Innovation Team Collaborative that employed lean management strategies with local and regional teams to facilitate efforts to make chronic hepatitis C virus a rare disease in the VHA.57

NAFLD Care Team

Given the central role of the liver and gastrointestinal tract in the field of nutrition, knowledge of the pathophysiology of the liver and digestive tract as well as emerging therapeutic options offered via metabolic endoscopy uniquely positions the hepatologist/gastroenterologist to take the lead in managing NAFLD. Treating NAFLD is best accomplished when the specialist partners with other health care providers who have expertise in the nutritional, behavioral, and physical activity aspects of treatment. The composition of the NAFLD care team and the roles that different providers fulfill can vary depending on the clinical setting; however, the hepatologist/gastroenterologist is best suited to lead the team, or alternatively, this role can be fulfilled by a provider with liver disease expertise.

Based on experiences from the United Kingdom, the minimum staffing of a NAFLD clinic should include a physician and nurse practitioner who has expertise in managing patients with chronic liver disease, a registered nurse, a dietitian, and a clinical pharmacy specialist (CPS).58 With coexistent diseases common and many veterans who have > 5 prescribed medications, risk of polypharmacy and adverse drug reactions are a concern, particularly since adherence in patients with chronic diseases has been reported to be as low as 43%.59-61 Risk of medication errors and serious adverse effects are magnified by difficulties with patient adherence, medication interactions, and potential need for frequent dose adjustments, particularly when on a weight-loss diet.

Without doubt, comprehensive medication management, offered by a highly trained CPS with independent prescriptive authority occurring while the veteran is in the NAFLD clinic, is highly desirable. Establishing a functional statement and care coordination agreement could describe the role of the CPS as a member of the NAFLD provider team.

Patient Evaluation

After being referred to the NAFLD clinic, the veteran should have a thorough assessment, including medical, nutritional, physical activity, exercise, and psychosocial evaluations (Figure 4).

The assessment also should include patient education to ensure that the patient has sufficient knowledge and skills to achieve the treatment goals. Educating on NAFLD is critical as most patients with NAFLD do not think of themselves as sick and have limited readiness for lifestyle changes.63,64 A better understanding of NAFLD combined with a higher self-efficacy seems to be positively linked to better nutritional habits.65

An online patient-reported outcomes measurement information system for a patient with NAFLD (eg, assessmentcenter.net) may be beneficial and can be applied within a routine NAFLD clinic visit because of its multidimensionality and compatibility with other chronic diseases.66-68 Other tools to assess health-related QOL include questionnaires, such as the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-fatigue, work productivity and activity impairment questionnaire: specific health problem, Short Form-36, and chronic liver disease questionnaire-NAFLD.23,69

The medical evaluation includes assessment of secondary causes of NAFLD and identification of NAFLD-related comorbidities. Weight, height, blood pressure, waist circumference, and BMI should be recorded. The physical exam should focus on signs of chronic liver disease and include inspection for acanthosis nigricans, hirsutism, and large neck circumference, which are associated with insulin resistance, polycystic ovarian syndrome, and obstructive sleep apnea, respectively. NAFLD-associated comorbidities may contribute to frailty or physical limitations that affect treatment with diet and exercise and need to be assessed. A thorough medication reconciliation will reveal whether the patient is prescribed obesogenic medications and whether comorbidities (eg, DM and dyslipidemia) are being treated optimally and according to current society guidelines.

Making the diagnosis of NAFLD requires excluding other (concomitant) chronic liver diseases. While often this is done indirectly using order sets with a panoply of available serologic tests without accounting for risks for rare causes of liver injury, a more focused and cost-effective approach is warranted. As most patients will already have had imaging studies that show fatty liver, assessment of liver fibrosis is an important step for risk stratification. Noninvasive scores (eg, FIB-4) can be used by the PCP to identify high-risk patients requiring further workup and referral.1,70 More sophisticated tools, including transient elastography and/or magnetic resonance elastography are applied for more sophisticated risk stratification and liver disease management (Table 2).71

A nutritional evaluation includes information about eating behavior and food choices, body composition analysis, and an assessment of short- and long-term alcohol consumption. Presence of bilateral muscle wasting, subcutaneous fat loss, and signs of micronutrient deficiencies also should be explored. The lifestyle evaluation should include the patient’s typical physical activity and exercise as well as limiting factors.

Finally, and equally important, the patient’s psychosocial situation should be assessed, as motivation and accountability are key to success and may require behavioral modification. Assessing readiness is done best with motivational interviewing, the 5As counseling framework (Ask, Advise, Assess, Assist, Arrange) or using open-ended questions, affirmation, reflections, and summaries.72,73 Even if not personally delivering behavioral treatment, such an approach also can help move patients toward addressing important health-related behaviors.

Personalized Interventions

If available, patients should be offered participation in NAFLD clinical trials. A personalized treatment plan should be developed for each patient with input from all NAFLD care team members. The patient and providers should work together to make important decisions about the treatment plan and goals of care. Making the patient an active participant in their treatment rather than the passive recipient will lead to improvement in adherence and outcomes. Patients will engage when they are comfortable speaking with providers and are sufficiently educated about their disease.

Personalized interventions may be built by combining different strategies, such as lifestyle and dietary interventions, NASH-specific pharmacotherapy, comorbidity management, metabolic endoscopy, and bariatric surgery. Although NASH-specific medications are not currently available, approved medications, including pioglitazone or liraglutide, can be considered for therapy.74,75 Ideally, the NAFLD team CPS would manage comorbidities, such as T2DM and dyslipidemia, but this also can be done by a hepatologist or other specialist. Metabolic endoscopy (eg, intragastric balloons) or bariatric surgery would be done by referral.

Resource-Limited Settings

Although the VHA offers care at > 150 medical centers and > 1,000 outpatient clinics, specialty care such as hepatology and sophisticated and novel testing modalities are not available at many facilities. In 2011 VHA launched the Specialty Care Access Network Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes to bring hepatitis C therapy and liver transplantation evaluations to rural areas without specialists.76-78 It is logical to explore how telehealth can be used for NAFLD care that requires complex management using new treatments and has a high societal impact, particularly when left untreated.

Telehealth must be easy to use and integrated into everyday routines to be useful for NAFLD management by addressing different aspects of promoting self-management, optimizing therapy, and care coordination. Participation in a structured face-to-face or group-based lifestyle program is often jeopardized by time and job constraints but can be successfully overcome using online approaches.79 The Internet-based VA Video Connect videoconferencing, which incorporates cell phone, laptop, or tablet use could help expand lifestyle interventions to a much larger community of patients with NAFLD and overcome local resource constraints. Finally, e-consultation also can be used in circumstances where synchronous communication with specialists may not be necessary.

Patient Monitoring and Quality Metrics

Monitoring of the patient after initiation of an intervention is variable but occurs more frequently at the beginning. For high-intensity dietary interventions, weekly monitoring for the first several weeks can ensure ongoing motivation, and accountability may increase the patient’s confidence and provide encouragement for further weight loss. It also is an opportunity to reestablish goals with patients with declining motivation. Long-term monitoring of patients may occur in 6- to 12-month intervals to document patient-reported outcomes, liver-related mortality, cardiovascular events, malignancies, and disease progression or regression.

While quality indicators have been proposed for cirrhosis care, such indicators have yet to be defined for NALD care.80 Such quality indicators assessed with validated questionnaires should include knowledge about NAFLD, satisfaction with care, perception of quality of care, and patient-reported outcomes. Other indicators may include use of therapies to treat dyslipidemia and T2DM. Last and likely the most important indicator of improved liver health in NAFLD will be either histologic improvement of NASH or improvement of the fibrosis risk category.

Outlook

With the enormous burden of NAFLD on the rise for many more years to come, quality care delivered to patients with NAFLD warrants resource-adaptive population health management strategies. With a limited number of providers specialized in liver disease, provider education assisted by clinical guidelines and decision support tools, development of referral and access to care mechanisms through integrated care, remote monitoring strategies as well as development of patient self-management and community resources will become more important. We have outlined essential components of an effective population health management strategy for NAFLD and actionable items for the VHA to consider when implementing these strategies. This is the time for the VHA to invest in efforts for NAFLD population care. Clearly, consideration must be given to local needs and resources and integration of technology platforms. Addressing NAFLD at a population level will provide yet another opportunity to demonstrate that VHA performs better on quality when compared with care systems in the private sector.81

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is an umbrella term that covers a spectrum of phenotypes ranging from nonalcoholic fatty liver or simple hepatic steatosis to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) defined by histologic findings of steatosis, lobular inflammation, cytologic ballooning, and some degree of fibrosis.1 While frequently observed in patients with at least 1 risk factor (eg, obesity, diabetes mellitus [DM], dyslipidemia, hypertension), NAFLD also is an independent risk factor for type 2 DM (T2DM), chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease.2 At early disease stages with absence of liver fibrosis, mortality is linked to cardiovascular and not liver disease. However, in the presence of NASH, fibrosis progression to liver cirrhosis, or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) represent the most important liver-related outcomes that determine morbidity and mortality.3 Mirroring the obesity and T2DM epidemics, the health care burden is projected to dramatically rise.

In the following article, we will discuss how the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is well positioned to implement an organizational strategy of comprehensive care for veterans with NAFLD. This comprehensive care strategy should include the development of a NAFLD clinic offering care for comorbid conditions frequently present in these patients, point-of-care testing, access to clinical trials, and outcomes monitoring as a key performance target for providers and the respective facility.

NAFLD disease burden

To fully appreciate the burden of a chronic disease like NAFLD, it is important to assess its long- and short-term consequences in a comprehensive manner with regard to its clinical impact, impact on the patient, and economic impact (Figure 1).

Clinical Impact

Clinical impact is assessed based on the prevalence and natural history of NAFLD and the liver fibrosis stage and determines patient survival. Coinciding with the epidemic of obesity and T2DM, the prevalence of NAFLD in the general population in North America is 24% and even higher with older age and higher body mass index (BMI).4,5 The prevalence for NAFLD is particularly high in patients with T2DM (47%). Of patients with T2DM and NAFLD, 65% have biopsy-proven NASH of which 15% have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis.6

NAFLD is the fastest growing cause of cirrhosis in the US with a forecasted NAFLD population of 101 million by 2030.7 At the same time, the number of patients with NASH will rise to 27 million of which > 7 million will have bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis; hepatic decompensation events are estimated to occur in 105,430 patients with liver cirrhosis, posing a major public health threat related to organ availability for liver transplantation.8 Since 2013, NAFLD has been the second leading cause for liver transplantation and the top reason for transplantation in patients aged < 50 years.9,10 As many patients with NAFLD are diagnosed with HCC at stages where liver transplantation is not an option, mortality from HCC in NAFLD patients is higher than with other etiologies as treatment options are restricted.11,12

Compared with that of the general population, veterans seeking care are older and sicker with 43% of veterans taking > 5 prescribed medications.13 Of those receiving VHA care, 6.6 million veterans are either overweight or obese; 165,000 are morbidly obese with a BMI > 40.14 In addition, veterans are 2.5 times more likely to have T2DM compared with that of nonveterans. Because T2DM and obesity are the most common risk factors for NAFLD, it is not surprising that NAFLD prevalence among veterans rose 3-fold from 2003 to 2011.15 It is now estimated that 540,000 veterans will progress to NASH and 108,000 will develop bridging fibrosis or liver cirrhosis by 2030.8 Similar to that of the general population, liver cirrhosis is attributed to NAFLD in 15% of veterans.15,16 NAFLD is the third most common cause of cirrhosis and HCC, occurring at an average age of 66 years and 70 years, respectively.16,17 Shockingly, 20% of HCCs were not linked to liver cirrhosis and escaped recommended HCC screening for patients with cirrhosis.18,19

Patient Impact

Assessment of disease burden should not be restricted to clinical outcomes as patients can experience a range of symptoms that may have significant impact on their health-related quality of life (QOL) and functional status.20 Using general but not disease-specific instruments, NAFLD patients reported outcomes score low regarding fatigue, activity, and emotions.21 More disease-specific questionnaires may provide better and disease-specific insights as how NASH impacts patients’ QOL.22-24

Economic Impact

There is mounting evidence that the clinical implications of NAFLD directly influence the economic burden of NAFLD.25 The annual burden associated with all incident and prevalent NAFLD cases in the US has been estimated at $103 billion, and projections suggest that the expected 10-year burden of NAFLD may increase to $1.005 trillion.26 It is anticipated that increased NAFLD costs will affect the VHA with billions of dollars in annual expenditures in addition to the $1.5 billion already spent annually for T2DM care (4% of the VA pharmacy budget is spent on T2DM treatment).27-29

Current Patient Care

Obesity, DM, and dyslipidemia are common conditions managed by primary care providers (PCPs). Given the close association of these conditions with NAFLD, the PCP is often the first point of medical contact for patients with or at risk for NAFLD.30 For that reason, PCP awareness of NAFLD is critical for effective management of these patients. PCPs should be actively involved in the management of patients with NAFLD with pathways in place for identifying patients at high risk of liver disease for timely referral to a specialist and adequate education on the follow-up and treatment of low-risk patients. Instead, diagnosis of NAFLD is primarily triggered by either abnormal aminotransferases or detection of steatosis on imaging performed for other indications.

Barriers to optimal management of NAFLD by PCPs have been identified and occur at different levels of patient care. In the absence of clinical practice guidelines by the American Association of Family Practice covering NAFLD and a substantial latency period without signs of symptoms, NAFLD may not be perceived as a potentially serious condition by PCPs and their patients; interestingly this holds true even for some medical specialties.31-39 More than half of PCPs do not test their patients at highest risk for NAFLD (eg, patients with obesity or T2DM) and may be unaware of practice guidelines.40-42

Guidelines from Europe and the US are not completely in accordance. The US guidelines are vague regarding screening and are supported by only 1 medical society, due to the lack of NASH-specific drug therapies. The European guidelines are built on the support of 3 different stakeholders covering liver diseases, obesity, and DM and the experience using noninvasive liver fibrosis assessments for patients with NAFLD. To overcome this apparent conflict, a more practical and risk-stratified approach is warranted.41,42

Making the diagnosis can be challenging in cases with competing etiologies, such as T2DM and alcohol misuse. There also is an overreliance on aminotransferase levels to diagnose NAFLD. Significant liver disease can exist in the presence of normal aminotransferases, and this may be attributed to either spontaneous aminotransferase fluctuations or upper limits of normal that have been chosen too high.43-47 Often additional workup by PCPs depends on the magnitude of aminotransferase abnormalities.

Even if NAFLD has been diagnosed by PCPs, identifying those with NASH is hindered by the absence of an accurate noninvasive diagnostic method and the need to perform a liver biopsy. Liver biopsy is often not considered or delayed to monitor patients with serial aminotransferases, regardless of the patient’s metabolic comorbidity profile or baseline aminotransferases.32 As a result, referral to a specialist often depends on the magnitude of the aminotransferase abnormality,30,48 and often occurs when advanced liver disease is already present.49 Finally, providers may not be aware of beneficial effects of lifestyle interventions and certain medications, including statins on NASH and liver fibrosis.50-53 As NAFLD is associated with excess cardiovascular- and cancer-related morbidity and mortality, it is possible that regression of NAFLD may improve associated risk for these outcomes as well.

Framework for Comprehensive NAFLD Care

Chronic liver diseases and associated comorbidities have long been addressed by PCPs and specialty providers working in isolation and within the narrow focus of each discipline. Contrary to working in silos of the past, a coordinated management strategy with other disciplines that cover these comorbidities needs to be established, or alternatively the PCP must be aware of the management of comorbidities to execute them independently. Integration of hepatology-driven NAFLD care with other specialties involves communication, collaboration, and sharing of resources and expertise that will address patient care needs. Obviously, this cannot be undertaken in a single outpatient visit and requires vertical and longitudinal follow-up over time. One important aspect of comprehensive NAFLD care is the targeting of a particular patient population rather than being seen as a panacea for all; cost-utility analysis is hampered by uncertainties around accuracy of noninvasive biomarkers reflecting liver injury and a lack of effectiveness data for treatment. However, it seems reasonable to screen patients at high risk for NASH and adverse clinical outcomes. Such a risk stratification approach should be cost-effective.

A first key step by the PCP is to identify whether a patient is at risk, especially patients with NASH. The majority of patients at risk are already seen by PCPs. While there is no consensus on ideal screening for NAFLD by PCPs, the use of ultrasound in the at-risk population is recommended in Europe.42 Although NASH remains a histopathologic diagnosis, a reasonable approach is to define NASH based on clinical criteria as done similarly in a real-world observational NAFLD cohort study.54 In the absence of chronic alcohol consumption and viral hepatitis and in a real-world scenario, NASH can be defined as steatosis shown on liver imaging or biopsy and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels of > 25 U/L. In addition, ≥ 1 of the following criteria must be met: BMI > 30, T2DM, dyslipidemia, or metabolic syndrome (Table 1).

In the absence of easy-to-use validated tests, all patients with NAFLD need to be assessed with simple, noninvasive scores for the presence of clinically relevant liver fibrosis (F2-portal fibrosis with septa; F3-bridging fibrosis; F4-liver cirrhosis); those that meet the fibrosis criteria should receive further assessment usually only offered in a comprehensive NAFLD clinic.1 PCPs should focus on addressing 2 aspects related to NAFLD: (1) Does my patient have NASH based on clinical criteria; and (2) Is my patient at risk for clinically relevant liver fibrosis? PCPs are integral in optimal management of comorbidities and metabolic syndrome abnormalities with lifestyle and exercise interventions.