User login

ChatGPT in Dermatology Clinical Practice: Potential Uses and Pitfalls

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology has increasingly been incorporated in medicine. In dermatology, AI has been used to detect and diagnose skin lesions, including skin cancer.1 ChatGPT (OpenAI) is a novel, highly popular development in generative AI technology. A large language model released in 2022, ChatGPT is a chatbot designed to mimic human conversation and generate specific detailed information when prompted. Free and publicly available, it has been used by millions of people. ChatGPT’s application in the medical field currently is being evaluated across several specialties, including plastic surgery, radiology, and urology.2-4 ChatGPT has the potential to assist health care professionals, including dermatologists, though its use raises important ethical considerations. Herein, we focus on the potential benefits as well as the pitfalls of using ChatGPT in dermatology clinical practice.

Potential Uses of ChatGPT in Practice

A major benefit of ChatGPT is its ability to improve clinical efficiency. First, ChatGPT can provide quick access to general medical information, similar to a search engine but with more natural language processing and contextual understanding to synthesize information.5 This function is useful for rapid concise answers to specific and directed questions. ChatGPT also can interact with its user by asking follow-up questions to produce more precise and relevant responses; this feature may help dermatologists form more accurate differential diagnoses. Additionally, ChatGPT can increase efficiency in clinical practice by drafting generic medical documents,2 including templates for after-visit summaries, postprocedure instructions, referrals, prior authorization appeal letters, and educational handouts. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. Another useful feature of ChatGPT is its ability to output information modeling human conversation. Because of this feature, ChatGPT also could be employed in clinical practice to serve as an interpreter for patients during clinic visits. Currently, the use of virtual translators can be cumbersome and subject to technical constraints. ChatGPT can provide accurate and conversational translations for patients and dermatologists, improving the patient-provider relationship.

ChatGPT also can contribute to major advancements in the field of dermatology beyond the clinical setting. Because of its ability to draw from extensive data that have already been uploaded, there are some uses of ChatGPT in a research context: to assist in finding resources for research and reviews, formulating hypotheses, drafting study protocols, and collecting large amounts of data within seconds.6

ChatGPT also has potential in advancing medical education. It could be used by medical schools to model interactive patient encounters to help students practice taking a patient’s history and creating differential diagnoses.6 This application of ChatGPT may help medical students hone their clinical skills in a low-stress environment without the restrictions that can come with hiring and training standardized patients, especially when mimicking dermatologic clinical encounters.

Other possibilities for ChatGPT in dermatologic practice include survey administration, clinical trial recruitment, and even automatic high-risk medication monitoring. Despite the many potential applications of ChatGPT in clinical practice, the question raised in each scenario is the quality, accuracy, and safety of what it produces.

Potential Pitfalls of ChatGPT in Practice and Possible Mitigation Strategies

A main concern in using ChatGPT in clinical practice is its potential to produce inaccurate or biased information. When prompted to create a research abstract based on previously published research, ChatGPT drafted abstracts that were clear and digestible but supplemented with incorrect data.7 A group of medical researchers who reviewed these ChatGPT-generated abstracts mistook 32% of the abstracts as having been written by human researchers. The implications of this finding are worrisome. If inaccurate or false information is used by ChatGPT in documents sent to insurance companies or patients, the patient’s safety as well as the dermatologist’s license and credibility are at stake. Thus, dermatologists looking to use ChatGPT to draft generic medical documents should actively review the output to ensure that the information is accurate. Importantly, ChatGPT also is only currently programmed with information up to 2021, limiting its access to recently published research articles and updated International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes.5 The continued development of ChatGPT will lead to regular updates by OpenAI that resolve this shortcoming in the future. Further, AI models may encode and perpetuate harmful stereotypes and social biases that are present in training data.8

When considering its potential in clinical practice, ChatGPT itself states that it can aid in clinical decision-making by processing patient information, including history, current symptoms, and biopsy and test results. This is uncharted territory, and providers who use ChatGPT at this stage to aid in decision-making should regard it similarly to information retrieved from a search engine. The information produced by ChatGPT should be used to substantiate but not definitively confirm a diagnosis or dictate management. Clinical suspicion by the dermatologist should always trump ChatGPT output. If physicians recommend ChatGPT output over their own advice, it can become a liability, as the technology is not regulated to any degree. Patients also should be cautious when seeking and following medical advice from ChatGPT, as it could be misleading or incorrect and could undermine the patient-physician relationship.6

Additionally, the specific use of ChatGPT to evaluate patient health records raises concerns related to patient privacy and confidentiality. Providers should never enter patient information protected by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act into ChatGPT or anywhere else on the internet. Mitigation of this risk is not currently possible; ChatGPT requires more development and further understanding to even consider its integration into current electronic health records without compromising patient confidentiality.

The Bottom Line

Overall, ChatGPT has the potential to improve efficiency in clinical practice by assisting with informational searches and document drafting. Importantly, increased efficiency can reduce provider burnout and lead to improved patient care. However, dermatologists should carefully weigh the ethical issues of nonmaleficence and justice in evaluating ChatGPT for accuracy, biases, and the protection of patient confidentiality.

Finally, we asked ChatGPT on February 28, 2023, what it thinks:

User: Should dermatologists use ChatGPT in clinical practice?

ChatGPT: As an AI language model, ChatGPT can be a useful tool in dermatology clinical practice, but it should be used with caution in conjunction with other sources of information and clinical judgement.

Dermatologists should be aware of the potential benefits and risks of using ChatGPT and make informed decisions about how to integrate it into their clinical practice. It’s important to remember that ChatGPT is not a substitute for clinical expertise or human interaction with patients, and it should only be used as a supplement to enhance the quality of patient care.

Dermatologists who choose to use ChatGPT should also be aware of its limitations and potential risks, such as limited accuracy, lack of context, and liability issues if it provides incorrect information or recommendations that lead to patient harm. Dermatologists should use their professional judgement and consult with other health care professionals when making important decisions regarding patient care.

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

- Thomsen K, Iversen L, Titlestad TL, et al. Systematic review of machine learning for diagnosis and prognosis in dermatology. J Dermatol Treat. 2020;31:496-510. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1682500

- Shen Y, Heacock L, Elias J, et al. ChatGPT and other large language models are double-edged swords. Radiology. 2023;307:E230163. doi:10.1148/radiol.230163

- Gupta R, Pande P, Herzog I, et al. Application of ChatGPT in cosmetic plastic surgery: ally or antagonist? Aesthet Surg J. 2023;43:NP587-NP590. doi: 10.1093/asj/sjad042

- Gabrielson AT, Odisho AY, Canes D. Harnessing generative artificial intelligence to improve efficiency among urologists: welcome ChatGPT. J Urol. 2023;209:827-829. doi:10.1097/JU.0000000000003383

- What is ChatGPT? OpenAI. Accessed August 10, 2023. https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq

- Haupt CE, Marks M. AI-generated medical advice—GPT and beyond. JAMA. 2023;329:1349-1350. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.5321

- Gao CA, Howard FM, Markov NS, et al. Comparing Scientific Abstracts Generated by ChatGPT to Original Abstracts Using an Artificial Intelligence Output Detector, Plagiarism Detector, and Blinded Human Reviewers. Scientific Communication and Education; 2022. doi:10.1101/2022.12.23.521610

- Weidinger L, Mellor J, Rauh M, et al. Ethical and social risks of harm from language models. arXiv. Preprint posted online December 8, 2021. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2112.04359

Practice Points

- ChatGPT potentially can play a beneficial role in dermatologic practice by quickly accessing and synthesizing information, drafting generic medical documents, interpreting visits, advancing medical education, and more.

- Dermatologists using ChatGPT should be extremely cautious, as it can produce false or biased information, perpetuate harmful stereotypes, and present information that is not up-to-date.

Erythematous Dermal Facial Plaques in a Neutropenic Patient

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

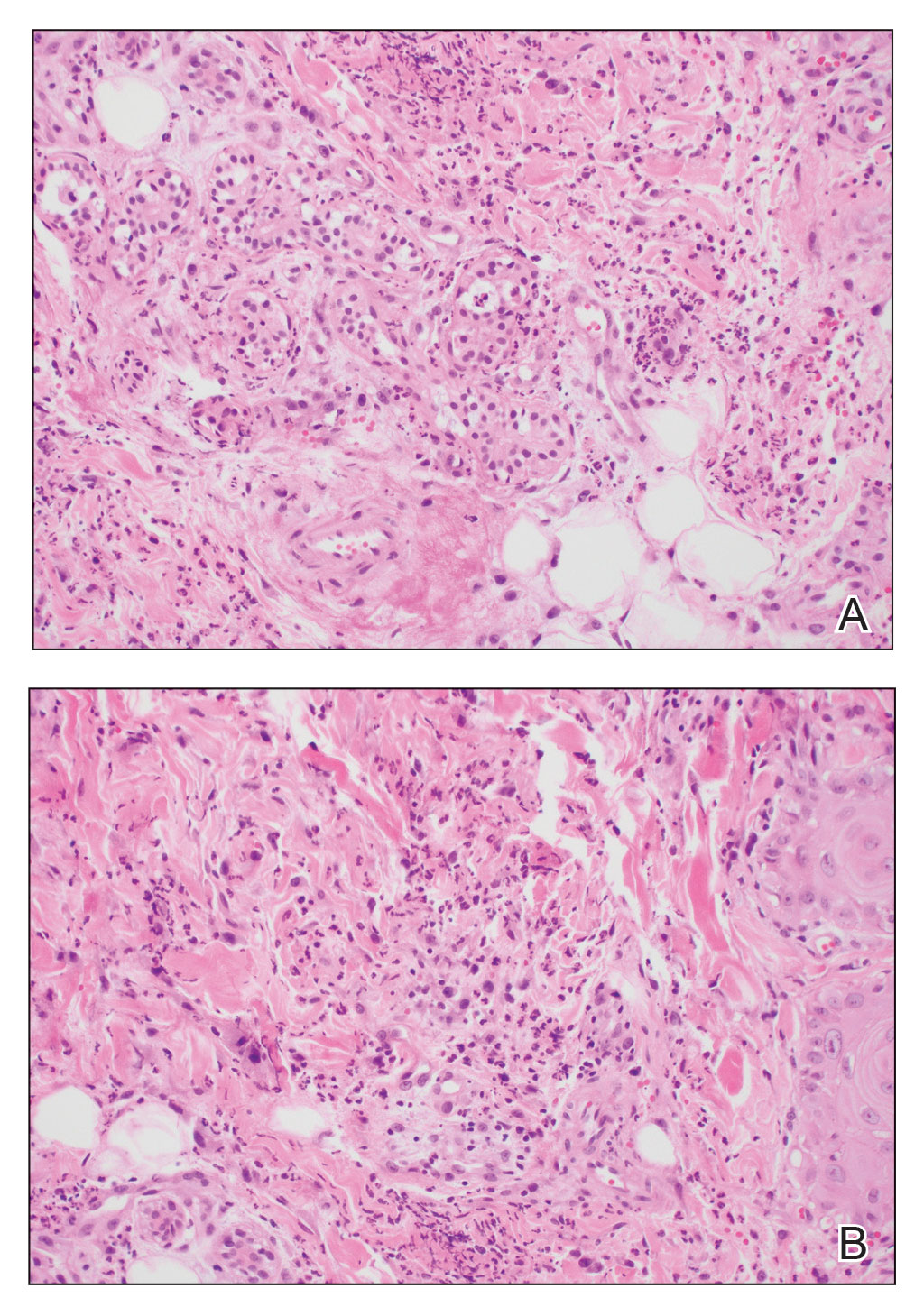

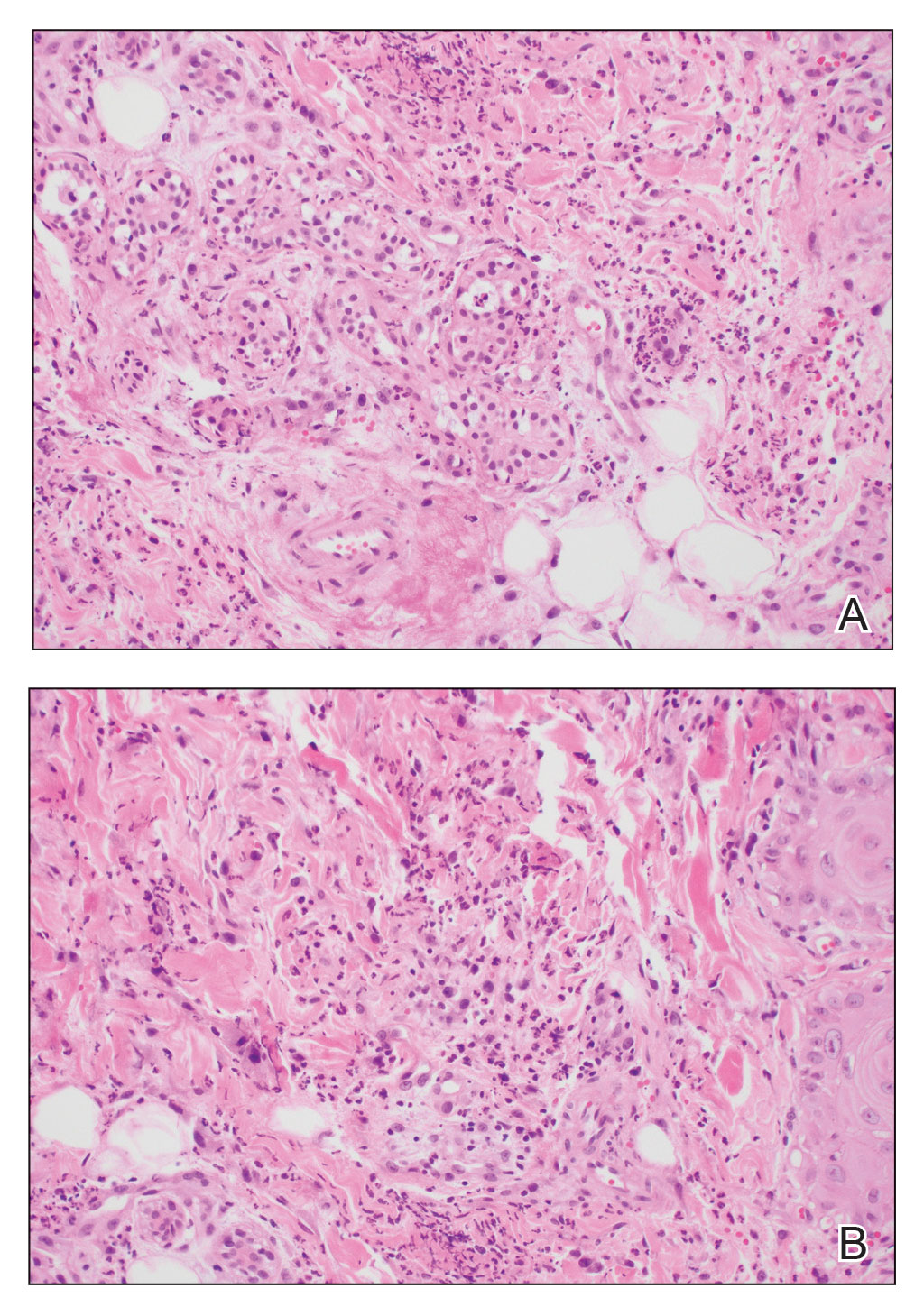

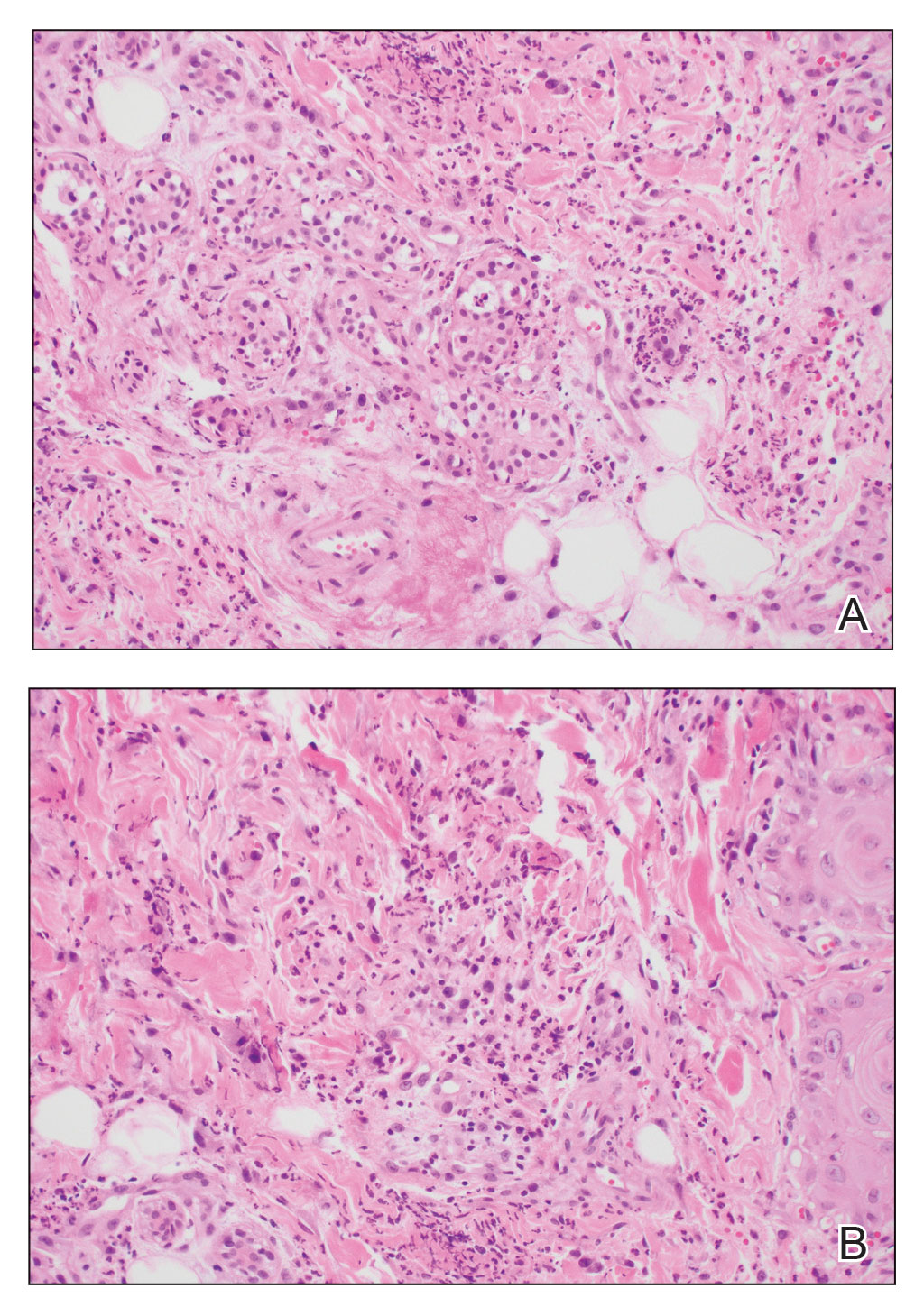

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

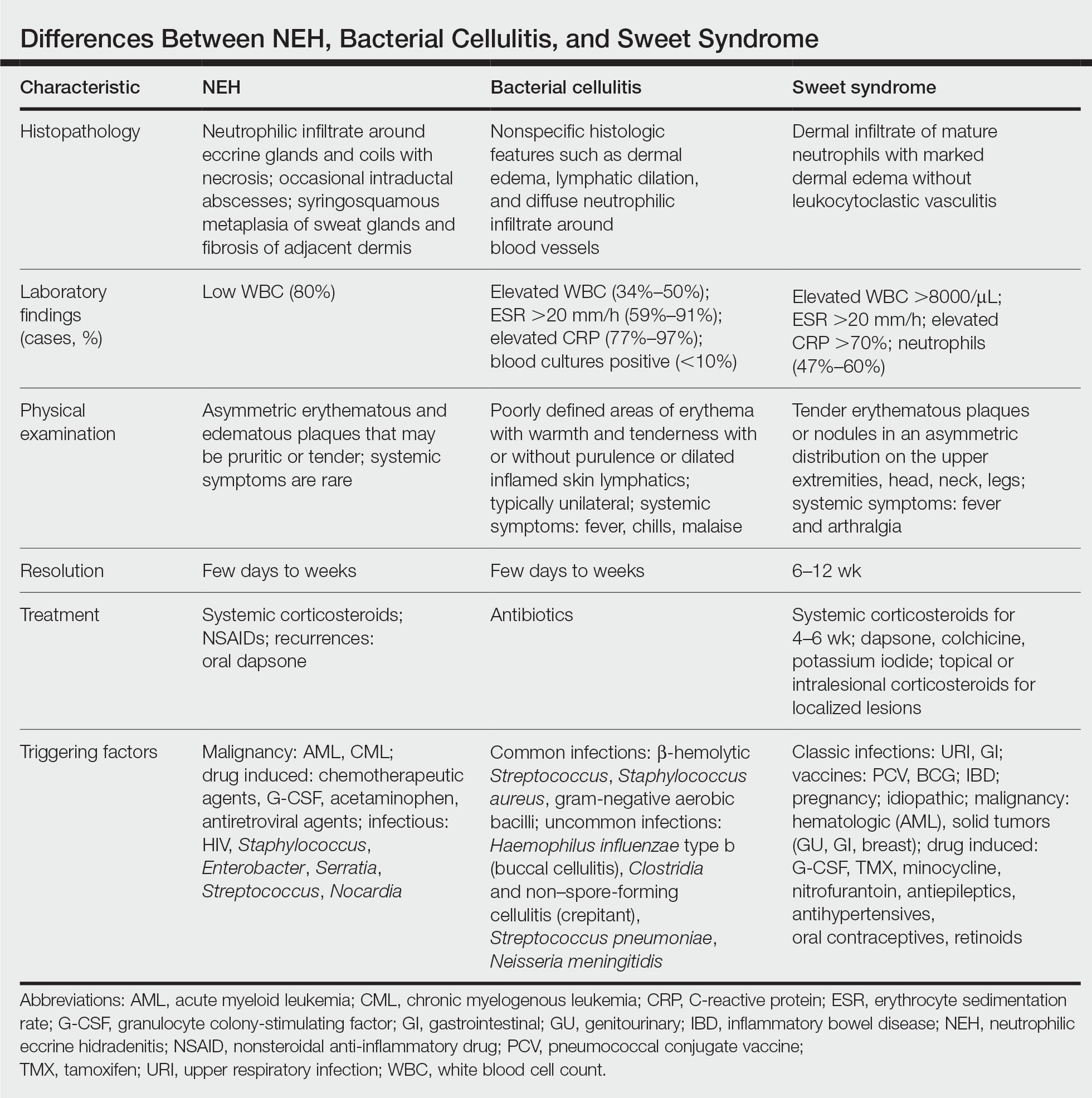

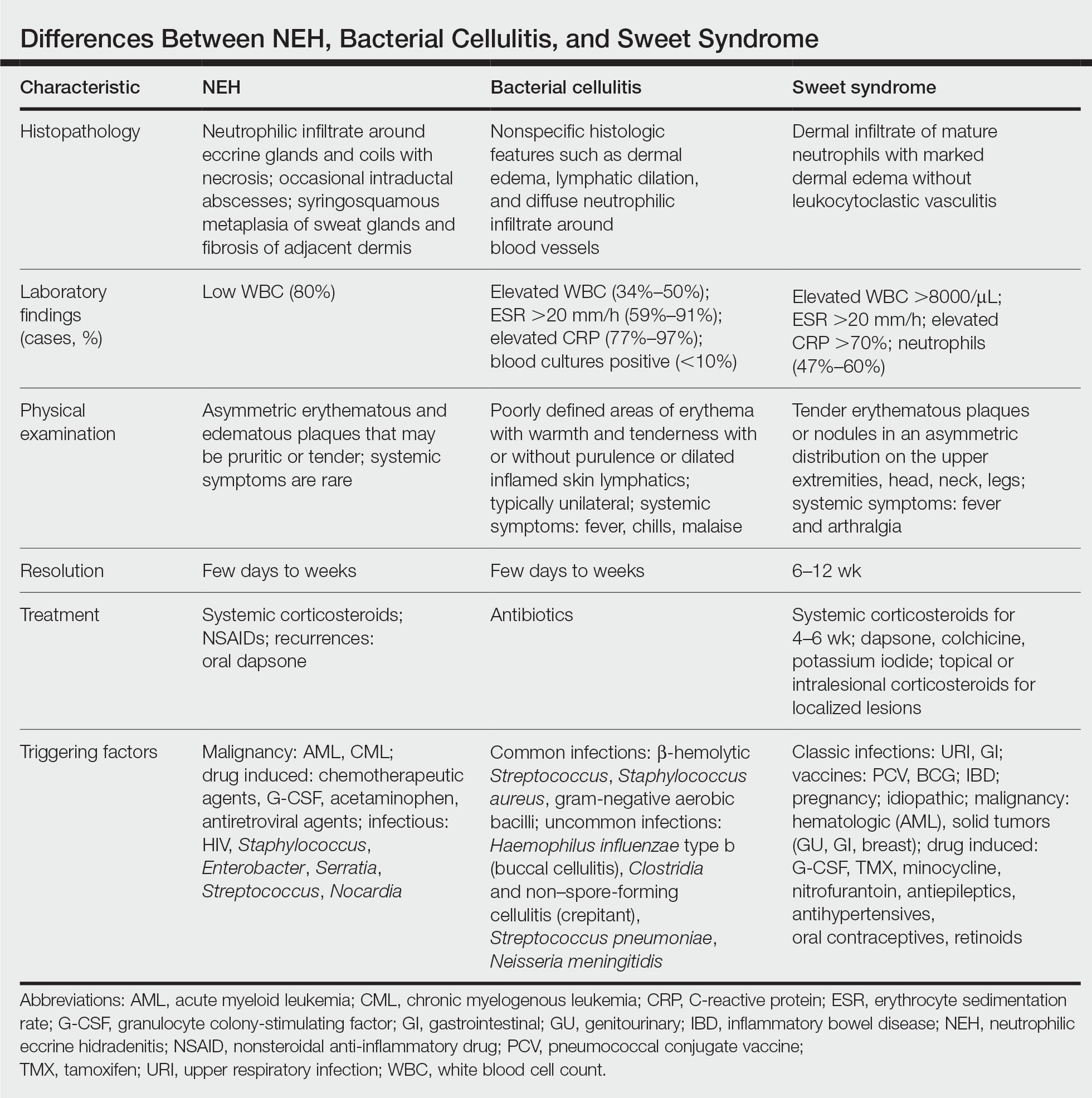

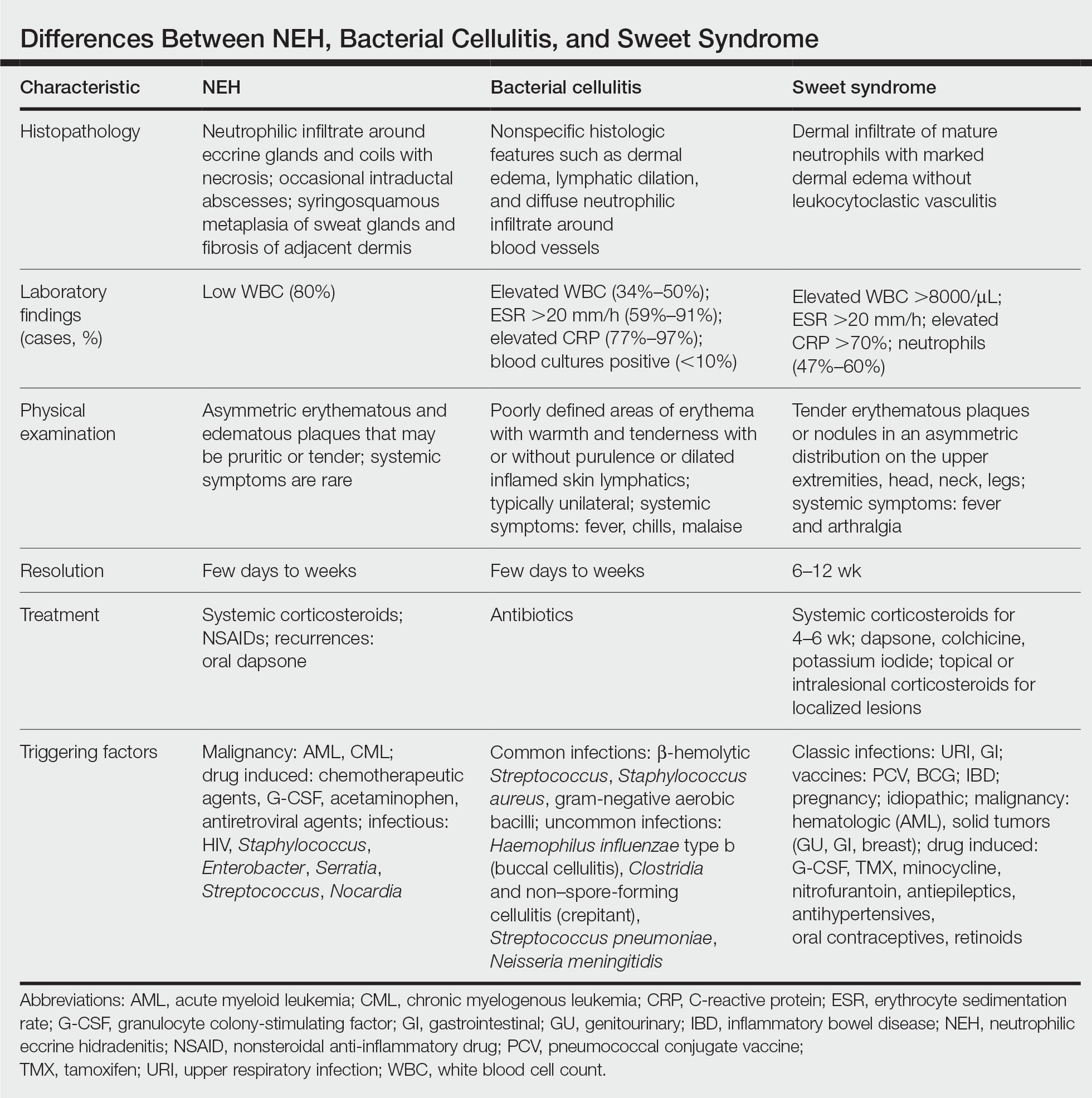

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

THE DIAGNOSIS: Neutrophilic Eccrine Hidradenitis

A biopsy from the left preauricular cheek demonstrated dermal neutrophilic inflammation around eccrine coils with focal necrosis (Figure). No notable diffuse dermal neutrophilic infiltrate was present, ruling out Sweet syndrome, and no notable interstitial neutrophilic infiltrate was present, making cellulitis and erysipelas less likely; panculture of tissue also was negative.1,2 Atypical cells in the deep dermis were positive for CD163 and negative for CD117, CD34, CD123, and myeloperoxidase, consistent with a diagnosis of neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis (NEH) and reactive histiocytes.3 Treatment with oral prednisone resulted in rapid improvement of symptoms.

Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is a rare reactive neutrophilic dermatosis characterized by eccrine gland involvement. This benign and self-limited condition presents as asymmetric erythematous papules and plaques.2 Among 8 granulocytopenic patients with neutrophilic dermatoses, 5 were diagnosed with NEH.4 Although first identified in 1982, NEH remains poorly understood.2 Initial theories suggested that NEH developed due to cytotoxic substances secreted in sweat glands causing necrosis and neutrophil chemotaxis; however, chemotherapy exposure cannot be linked to every case of NEH. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis can be extremely difficult to differentiate clinically from conditions such as cellulitis and Sweet syndrome.

A patient history can be helpful in identifying triggering factors. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis most commonly is associated with malignant, drug-induced, or infectious triggers, while Sweet syndrome has a broad range of associations including infections, vaccines, inflammatory bowel disease, pregnancy, malignancy, and drug-induced etiologies (Table).1 On average, NEH presents 10 days after chemotherapy induction, with 70% of cases presenting after the first chemotherapy cycle.5 Bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas have an infectious etiology, and patients may report symptoms such as fever, chills, or malaise. Immunosuppressed patients are at greater risk for infection; therefore, clinical signs of infection in a granulocytopenic patient should be addressed urgently.

Physical examination may have limited value in differentiating between these diagnoses, as neutrophilic dermatoses notoriously mimic infection. Cutaneous lesions can appear as pruritic or tender erythematous plaques, papules, or nodules in these conditions, though cellulitis and erysipelas tend to be unilateral and may have associated purulence or inflamed skin lymphatics. Given the potential for misdiagnosis, approaching patients with a broad differential can be helpful. In our patient, the differential diagnosis included Sweet syndrome, NEH, bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, leukemia cutis, sarcoid, and eosinophilic cellulitis.

Leukemia cutis refers to the infiltration of neoplastic leukocytes in the skin and often occurs in patients with peripheral leukemia, most often acute myeloid leukemia or chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Patients with leukemia cutis often have a worse prognosis, as this finding signifies extramedullary spread of disease.6 Clinically, lesions can appear similar to those seen in our patient, though they typically are not symptomatic, can be nodular, tend to exhibit a violaceous hue, and occasionally may be hemorrhagic. Wells syndrome (also known as eosinophilic cellulitis) is an inflammatory dermatosis that presents as painful or pruritic, edematous and erythematous plaques.7,8 A green hue on resolution is present in some cases and may help clinicians differentiate this disease from mimickers.7 Often, eosinophilic cellulitis is misdiagnosed as bacterial cellulitis and treated with antibiotics. The presence of systemic symptoms such as fever or arthralgia is more typical of bacterial cellulitis, erysipelas, eosinophilic cellulitis, or Sweet syndrome than of NEH.1 Additionally, inflammatory markers (ie, C-reactive protein) and white blood cell counts tend to be elevated in bacterial cellulitis and Sweet syndrome, while leukopenia often is seen in NEH.

Histopathology is crucial in distinguishing these disease etiologies. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis is diagnosed by the characteristic neutrophilic infiltrate and necrosis surrounding eccrine glands and coils. There also may be occasional intraductal abscesses and syringosquamous metaplasia of the sweat glands along with fibrosis of the adjacent dermis. In contrast, histologic sections of Sweet syndrome show numerous mature neutrophils infiltrating the dermis with marked papillary dermal edema. The histopathology of bacterial cellulitis and erysipelas is less specific, but common features include dermal edema, lymphatic dilation, and a diffuse neutrophilic infiltrate surrounding blood vessels. Pathogenic organisms may be seen on histopathology but are not required for the diagnosis of bacterial cellulitis or erysipelas.2 Additionally, blood and tissue culture can assist in identification of both the source of infection and the causative organism, but cultures may not always be positive.

Comparatively, the histopathologic features of eosinophilic cellulitis include dermal edema, eosinophilic infiltration, and flame figures that form when eosinophils degranulate and coat collagen fibers with major basic protein. Flame figures are characteristic but not pathognomonic for eosinophilic cellulitis.7 The histopathology of leukemia cutis varies based on the leukemia classification; generally, in acute myeloid leukemia the infiltrate is composed of neoplastic cells in the early stages of development that are positive for myeloid markers such as myeloperoxidase. Atypical and immature granulocytes within the leukocytic infiltrate differentiate this condition from the other diagnoses. Treatment may entail chemotherapy or radiotherapy, and this diagnosis generally carries the worst prognosis of all the conditions in the differential.6

Differentiating between these conditions is important in guiding treatment, especially in patients with febrile neutropenia. Unnecessary steroids in immunosuppressed patients can be dangerous, especially if the patient has an infection such as bacterial cellulitis. Furthermore, unwarranted antibiotic use for noninfectious conditions may expose patients to substantial side effects and not improve the condition. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis typically is self-limited and treated symptomatically with systemic corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.3 Sweet syndrome often requires a longer course of oral steroids. Leukemia cutis worsens as the leukemia advances, and treatment of the underlying malignancy is the most effective treatment.9

Early and accurate recognition of the diagnosis can prevent harmful diagnostic delay, unnecessary antibiotic use, or extended steroid taper in neutropenic patients. Appreciating the differences between these diagnoses can assist clinicians in investigating and tailoring a broad differential to specific patient presentations, which is especially critical when considering common mimickers for life-threatening conditions.

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

- Nelson CA, Stephen S, Ashchyan HJ, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:987-1006. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.11.0642

- Srivastava M, Scharf S, Meehan SA, et al. Neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis masquerading as facial cellulitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56:693-696. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.07.032

- Copaescu AM, Castilloux JF, Chababi-Atallah M, et al. A classic clinical case: neutrophilic eccrine hidradenitis. Case Rep Dermatol. 2013; 5:340-346. doi:10.1159/000356229

- Aractingi S, Mallet V, Pinquier L, et al. Neutrophilic dermatoses during granulocytopenia. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:1141-1145.

- Cohen PR. Neutrophilic dermatoses occurring in oncology patients. Int J Dermatol. 2007;46:106-111. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4632.2006.02605.x

- Wang CX, Pusic I, Anadkat MJ. Association of leukemia cutis with survival in acute myeloid leukemia. JAMA Dermatol. 2019;155:826. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.0052

- Chung CL, Cusack CA. Wells syndrome: an enigmatic and therapeutically challenging disease. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:908-911.

- Räßler F, Lukács J, Elsner P. Treatment of eosinophilic cellulitis (Wells syndrome): a systematic review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2016;30:1465-1479. doi:10.1111/jdv.13706

- Hobbs LK, Carr PC, Gru AA, et al. Case and review: cutaneous involvement by chronic neutrophilic leukemia vs Sweet syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma. J Cutan Pathol. 2021;48:644-649. doi:10.1111 /cup.13925

A 50-year-old woman undergoing cytarabine induction therapy for acute myeloid leukemia developed tender, erythematous, dermal plaques on the nasal dorsum, left medial eyebrow, left preauricular cheek, and right cheek. The rash erupted 7 days after receiving the cytarabine induction regimen. She had a fever (temperature, 39.9 °C [103.8 °F]) and also was neutropenic.