User login

The case for behavioral health integration into primary care

In a typical primary care practice, detecting and managing mental health problems competes with other priorities such as treating acute physical illness, monitoring chronic disease, providing preventive health services, and assessing compliance with standards of care.1 These competing demands for a primary care provider’s time, paired with limited mental health resources in the community, may result in suboptimal behavioral health care.1-3 Even when referrals are made to

Approximately 30% of adults with physical disorders also have one or more behavioral health conditions, such as anxiety, panic, mood, or substance use disorders.6 Although physical and behavioral health conditions are inextricably linked, their assessment and treatment get separated into different silos.7 Given that fewer than 20% of depressed patients are seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist,8 the responsibility of providing mental health care often falls on the primary care physician.8,9

Efforts to improve the treatment of common mental disorders in primary care have traditionally focused on screening for these disorders, educating primary care providers, developing treatment guidelines, and referring patients to mental health specialty care.10 However, behavioral health integration offers another way forward.

WHAT IS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION?

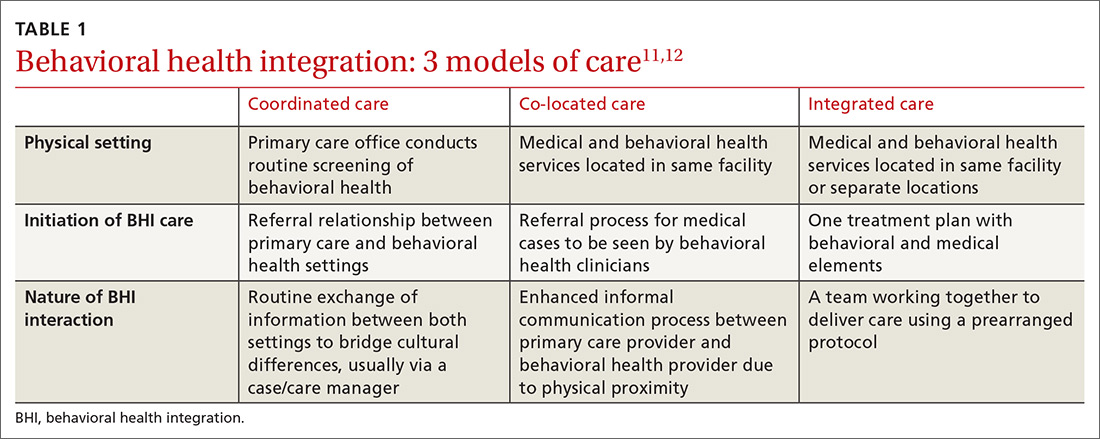

Behavioral health integration (BHI) in primary care refers to primary care physicians and behavioral health clinicians working in concert with patients to address their primary care and behavioral health needs.11

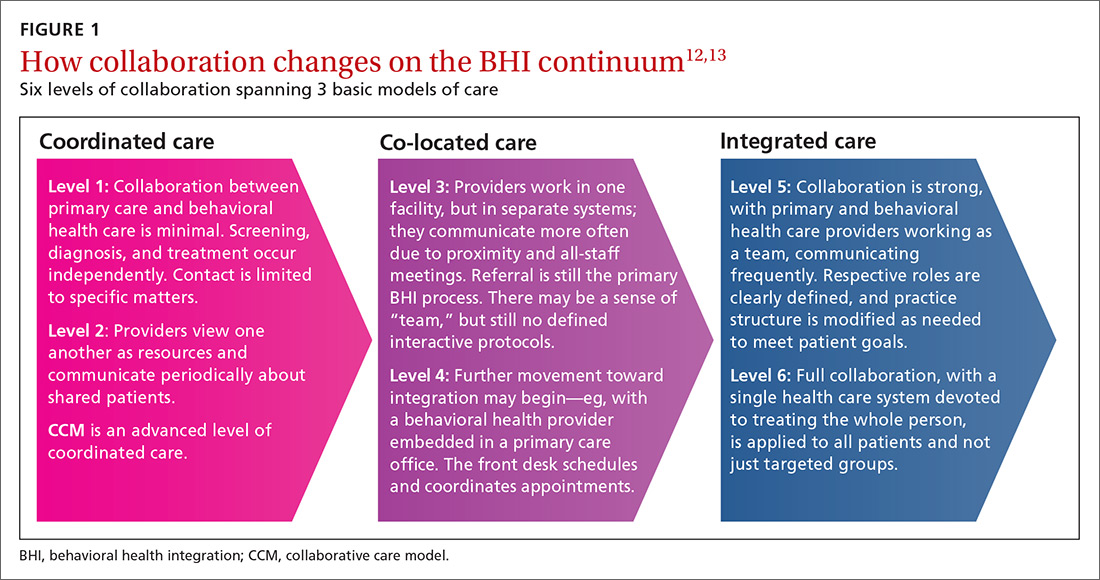

Numerous overlapping terms have been used to describe BHI, and this has caused some confusion. In 2013, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) issued a lexicon standardizing the terminology used in BHI.11 The commonly used terms are

COORDINATED CARE AND THE COLLABORATIVE CARE MODEL

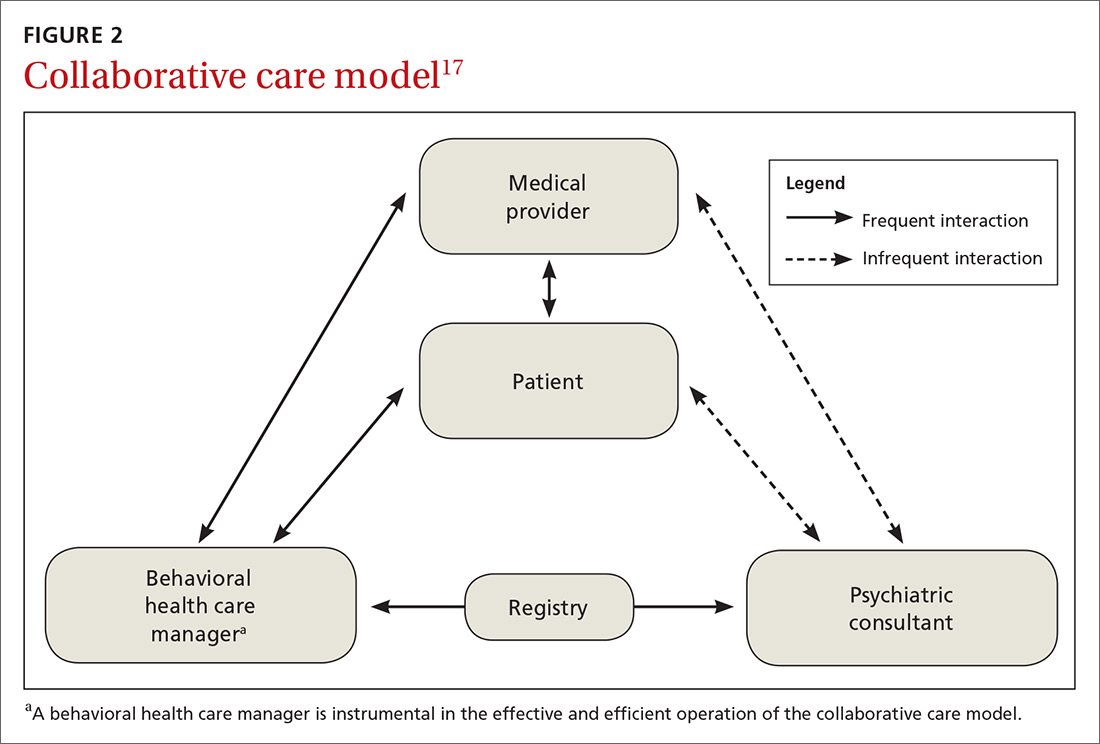

BHI at the level of coordinated care has almost exclusively been studied and practiced along the lines of the collaborative care model (CCM).14-16 This model represents an advanced level of coordinated care in the BHI continuum. The most substantial evidence for CCM lies in the management of depression and anxiety.14-16

Usual care involves the primary care physician and the patient. CCM adds 2 vital roles—a behavioral health care manager and a psychiatric consultant. A behavioral health care manager is typically a counselor, clinical social worker, psychologist, or psychiatric nurse who performs all care-management tasks including offering psychotherapy when that is part of the treatment plan.

Continue to: The care manager's functions include...

The care manager’s functions include systematic follow-up with structured monitoring of symptoms and treatment adherence, coordination and communication among care providers, patient education, and self-management support, including the use of motivational interviewing. The behavioral health care manager performs this systematic follow up by maintaining a patient “registry”—case-management software used in conjunction with, or embedded in, the practice electronic health record to track patients’ data and clinical outcomes, as well as to facilitate decision-making.

The care manager communicates with the psychiatrist, who offers suggestions for drug therapy, which is prescribed by the primary care physician. The care manager also regularly evaluates the patient’s status using a standardized scale, communicates these scores to the psychiatrist, and transmits any recommendations to the primary care physician (FIGURE 2).17

EVIDENCE FOR CCM

Collaborative and routine care were compared in a 2012 Cochrane review that included 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 24,308 patients worldwide.16 Seventy-two of the 79 RCTs focused on patients with depression or depression with anxiety, while 6 studies included participants with only anxiety disorders.16 One additional study focused on mental health quality of life. (To learn about CCM and severe mental illness and substance use disorder, see “Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence.”18-20)

SIDEBAR

Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence

Evidence for collaborative care in severe mental illness (SMI) is very limited. SMI is defined as schizophrenia or other schizophrenia-like psychoses (eg, schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), bipolar affective disorder, or other psychosis.

A 2013 Cochrane review identified only 1 RCT involving 306 veterans with bipolar disease.18 The review concluded that there was low-quality evidence that collaborative care led to a relative risk reduction of 25% for psychiatric admissions at Year 2 compared with standard care (RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.99).18

One 2017 RCT involving 245 veterans that looked at a collaborative care model for patients with severe mental illness found a modest benefit for physical health-related quality of life, but did not find any benefit in mental health outcomes.19

Alcohol dependence. There is very limited, but high-quality, evidence for the utility of CCM in alcohol dependence. In one RCT, 163 veterans were assigned to either CCM or referral to standard treatment in a specialty outpatient addiction treatment program. The CCM group had a significantly higher proportion of participants engaged in treatment over the study’s 26 weeks (odds ratio [OR] = 5.36; 95% CI, 2.99-9.59). The percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly lower in the CCM group (OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 1.27-3.66), while overall abstinence did not differ between groups.20

For adults with depression treated with the CCM, significantly greater improvement in depression outcome measures was seen in the short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] = -0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.41 to -0.27; risk ratio [RR] = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.22-1.43), in the medium term (SMD = -0.28; 95% CI, -0.41 to -0.15; RR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17–1.48), and in the long term (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI, -0.46 to -0.24; RR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18–1.41).16

Comparisons of mental health quality of life over the short term (0-6 months), medium term (7-12 months), and long term (13-24 months) did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16 Comparisons of physical health quality of life over the short term and medium term did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16

Continue to: Significantly greater improvement...

Significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes was seen for adults treated with CCM in the short term (SMD = -0.30; 95% CI, -0.44 to -0.17; RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.21–1.87), in the medium term (SMD = -0.33; 95% CI, -0.47 to -0.19; RR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18-1.69), and in the long term (SMD = -0.20; 95% CI, -0.34 to -0.06; RR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42).16

A 2016 systematic review of 94 RCTs involving more than 25,000 patients also provided high-quality evidence that collaborative care yields small-to-moderate improvements in symptoms from mood disorders and mental health-related quality of life.15 A 2006 meta-analysis of 37 RCTs comprising 12,355 patients showed that collaborative care involving a case manager is more effective than standard care in improving depression outcomes at 6 months (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.32) and up to 5 years (SMD = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.001-0.31).21

Better care of mental health disorders also improves medical outcomes

Several trials have focused on jointly managing depression and a chronic physical condition such as chronic pain, diabetes, and coronary heart disease,22 demonstrating improved outcomes for both depression and the comanaged conditions.

- Chronic pain. When compared with usual care, collaborative care resulted in moderate reductions in both pain severity and associated disability (41.5% vs 17.3%; RR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6-3.2).23

- Diabetes. Patients managed collaboratively were more likely to have a decrease of ≥ 1% in the glycated hemoglobin level from baseline (36% vs 19%; P = .006).24

- Cardiovascular disease. Significant real-world risk reduction was achieved by improving blood pressure control (58% achieved blood pressure control compared with a projected target of 20%).22

IS THERE A COMMON THREAD AMONG SUCCESSFUL CCMs?

Attempts to identify commonalities between the many iterations of successful CCMs have produced varying results due to differing selections of relevant RCTs.25-29 However, a few common features have been identified:

- care managers assess symptoms at baseline and at follow-up using a standardized measure such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);

- care managers monitor treatment adherence;

- follow-up is active for at least 16 weeks;

- primary care and mental health providers actively engage in patient management; and

- mental health specialists regularly supervise care managers.

The one feature that is consistent with improved outcomes is the presence of the care manager.25-29

Continue to: The improvement associated...

The improvement associated with collaborative care is clinically meaningful to patients and physicians. In one RCT, collaborative care doubled response rates of depression treatment compared with usual care.3 Quality improvement data from real-world implementation of collaborative care programs suggests that similar outcomes can be achieved in a variety of settings.30

COST BENEFITS OF CCM

Collaborative care for depression is associated with lower health care costs.29,31

A meta-analysis of 57 RCTs in 2012 showed that CCM improves depression outcomes across populations, settings, and outcome domains, and that these results are achieved at little to no increase in treatment costs compared with usual care (Cohen’s d = 0.05; 95% CI, –0.02–0.12).26

When collaborative care was compared with routine care in an RCT involving 1801 primary care patients ≥ 60 years who were suffering from depression, a cost saving of $3363 per patient over 4 years was demonstrated in the intervention arm.31

A technical analysis of 94 RCTs in 2015 concluded that CCM is cost effective compared with usual care, with a range of $15,000 to $80,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained. These studies also indicated that organizations’ costs to implement CCM increase in the short term. Based on this analysis, organizations would need to invest between $3 to $22 per patient per month to implement and sustain CCMs, depending on the prevalence of depression in the population.29

Continue to: OTHER MODELS OF BHI

OTHER MODELS OF BHI

Higher levels of BHI such as co-location and integration do not have the same quality of evidence as CCM.

A 2009 Cochrane review of 42 studies involving 3880 patients found that mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care settings brought about significant reductions in primary care physician consultations (SMD = ‐0.17; 95% CI, ‐0.30 to ‐0.05); a relative risk reduction of 23% in psychotropic prescribing (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56–0.79); a decrease in prescribing costs (SMD = ‐0.22; 95% CI, ‐0.38 to ‐0.07); and a relative risk reduction in mental health referral of 87% (RR = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09–0.20) for the patients they were seeing.32 The authors concluded the changes were modest in magnitude and inconsistent across different studies.32

Embedding medical providers in behavior health centers—ie, the reverse co-location model—also has very limited evidence. An RCT involving 120 veterans found that patients enrolled in a reverse co-location clinic did significantly better than controls seen in a general care clinic in terms of continuity of care and preventive care such as screening for hypertension (84.7% vs 65.6%; X 2 = 5.9, P = .01), diabetes (71.2% vs 45.9%; X 2 = 7.9, P < .005), hepatitis (39% vs 14.8%; X 2 = 9, P = .003), and cholesterol (79.7% vs 57.4%; X 2 = 6.9, P = .009).33

HOW TO IMPLEMENT A SUCCESSFUL BHI PROGRAM

A demonstration and evaluation project involving 11 diverse practices in Colorado explored ways to integrate behavioral health in primary care. Five main themes emerged34,35:

- Frame integrated care as a necessary paradigm shift to patient-centered, whole-person health care.

- Define relationships and protocols up front, understanding that they will evolve.

- Build inclusive, empowered teams to provide the foundation for integration.

- Develop a change management strategy of continuous evaluation and course correction.

- Use targeted data collection pertinent to integrated care to drive improvement and impart accountability.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review has organized an extensive list of resources36 for implementing BHI models, a sampling of which is shown in TABLE 2.

Continue to: TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

There is high quality evidence that collaborative care works for the management of depression and anxiety disorder in primary care, and this is associated with significant cost savings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (FNU) Rajesh, MD, Main Campus Family Medicine Clinic, MetroHealth, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; frajesh@metrohealth.org

1. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:150-154.

2. Rush A, Trivedi M, Carmody T, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:46-53.

3. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Bradford DW, Slubicki MN, McDuffie J, et al. Effects of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness. 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/smi-REPORT.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. Druss BG, von Esenwein S. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:145-153.

6. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental Disorders and Medical Comorbidity. Research Synthesis Report No. 21. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; February 2011.

7. Reed SJ, Shore KK, Tice JA. Effectiveness and value of integrating behavioral health into primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:691-692.

8. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55-61.

9. Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38632/. Accessed March 2, 2019.

10. Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss B, et al. Transforming mental health care at the interface with general medicine: report for the presidents commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:37-47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37.

11. Peek CJ; the National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. AHRQ. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

12. Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare and update throughout the document. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/A_Standard_Framework_for_Levels_of_Integrated_Healthcare.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

13. Integrating physical and behavioral health care: promising Medicaid models. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/8553-integrating-physical-and-behavioral-health-care-promising-medicaid-models.pdf. Published February 2014. Accessed May 29, 2019.

14. Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: the collaborative care model. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

15. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

16. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10.1002/14651858.cd006525.pub2.

17. Team Structure. University of Washington AIMs Center. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure. Published 2017.Accessed May 29, 2019.

18. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

19. Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, et al. Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:129-137.

20. Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto HSA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29:162-168.

21. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314-2321.

22. Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Magnan S, et al. Impact of a national collaborative care initiative for patients with depression and diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;15:77-85.

23. Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain. JAMA. 2009;301:2009-2110.

24. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611-2620.

25. Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, et al. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions. Med Care. 2013;51:922-930.

26. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;11:790-804.

27. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Rubenstein LV, Williams JW Jr, Danz M, et al. Determining key features of effective depression interventions. 2009. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/depinter.cfm. Accessed August 22, 2018.

28. Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E, et al. Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108114.

29. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Tice JA, Ollendorf DA, Reed SJ, et al. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BHI_Final_Report_0602151.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2018.

30. Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91-113.

31. Unützer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95-100.

32. Harkness EF, Bower PJ. On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000532.

33. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:861-868.

34. Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, Waller E, et al. Integrating behavioral and physical health care in the real world: early lessons from advancing care together. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:588-602.

35. Gold SB, Green LA, Peek CJ. From our practices to yours: key messages for the journey to integrated behavioral health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:25-34.

36. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CTAF_BHI_Action_Guide_060215.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019.

In a typical primary care practice, detecting and managing mental health problems competes with other priorities such as treating acute physical illness, monitoring chronic disease, providing preventive health services, and assessing compliance with standards of care.1 These competing demands for a primary care provider’s time, paired with limited mental health resources in the community, may result in suboptimal behavioral health care.1-3 Even when referrals are made to

Approximately 30% of adults with physical disorders also have one or more behavioral health conditions, such as anxiety, panic, mood, or substance use disorders.6 Although physical and behavioral health conditions are inextricably linked, their assessment and treatment get separated into different silos.7 Given that fewer than 20% of depressed patients are seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist,8 the responsibility of providing mental health care often falls on the primary care physician.8,9

Efforts to improve the treatment of common mental disorders in primary care have traditionally focused on screening for these disorders, educating primary care providers, developing treatment guidelines, and referring patients to mental health specialty care.10 However, behavioral health integration offers another way forward.

WHAT IS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION?

Behavioral health integration (BHI) in primary care refers to primary care physicians and behavioral health clinicians working in concert with patients to address their primary care and behavioral health needs.11

Numerous overlapping terms have been used to describe BHI, and this has caused some confusion. In 2013, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) issued a lexicon standardizing the terminology used in BHI.11 The commonly used terms are

COORDINATED CARE AND THE COLLABORATIVE CARE MODEL

BHI at the level of coordinated care has almost exclusively been studied and practiced along the lines of the collaborative care model (CCM).14-16 This model represents an advanced level of coordinated care in the BHI continuum. The most substantial evidence for CCM lies in the management of depression and anxiety.14-16

Usual care involves the primary care physician and the patient. CCM adds 2 vital roles—a behavioral health care manager and a psychiatric consultant. A behavioral health care manager is typically a counselor, clinical social worker, psychologist, or psychiatric nurse who performs all care-management tasks including offering psychotherapy when that is part of the treatment plan.

Continue to: The care manager's functions include...

The care manager’s functions include systematic follow-up with structured monitoring of symptoms and treatment adherence, coordination and communication among care providers, patient education, and self-management support, including the use of motivational interviewing. The behavioral health care manager performs this systematic follow up by maintaining a patient “registry”—case-management software used in conjunction with, or embedded in, the practice electronic health record to track patients’ data and clinical outcomes, as well as to facilitate decision-making.

The care manager communicates with the psychiatrist, who offers suggestions for drug therapy, which is prescribed by the primary care physician. The care manager also regularly evaluates the patient’s status using a standardized scale, communicates these scores to the psychiatrist, and transmits any recommendations to the primary care physician (FIGURE 2).17

EVIDENCE FOR CCM

Collaborative and routine care were compared in a 2012 Cochrane review that included 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 24,308 patients worldwide.16 Seventy-two of the 79 RCTs focused on patients with depression or depression with anxiety, while 6 studies included participants with only anxiety disorders.16 One additional study focused on mental health quality of life. (To learn about CCM and severe mental illness and substance use disorder, see “Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence.”18-20)

SIDEBAR

Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence

Evidence for collaborative care in severe mental illness (SMI) is very limited. SMI is defined as schizophrenia or other schizophrenia-like psychoses (eg, schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), bipolar affective disorder, or other psychosis.

A 2013 Cochrane review identified only 1 RCT involving 306 veterans with bipolar disease.18 The review concluded that there was low-quality evidence that collaborative care led to a relative risk reduction of 25% for psychiatric admissions at Year 2 compared with standard care (RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.99).18

One 2017 RCT involving 245 veterans that looked at a collaborative care model for patients with severe mental illness found a modest benefit for physical health-related quality of life, but did not find any benefit in mental health outcomes.19

Alcohol dependence. There is very limited, but high-quality, evidence for the utility of CCM in alcohol dependence. In one RCT, 163 veterans were assigned to either CCM or referral to standard treatment in a specialty outpatient addiction treatment program. The CCM group had a significantly higher proportion of participants engaged in treatment over the study’s 26 weeks (odds ratio [OR] = 5.36; 95% CI, 2.99-9.59). The percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly lower in the CCM group (OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 1.27-3.66), while overall abstinence did not differ between groups.20

For adults with depression treated with the CCM, significantly greater improvement in depression outcome measures was seen in the short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] = -0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.41 to -0.27; risk ratio [RR] = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.22-1.43), in the medium term (SMD = -0.28; 95% CI, -0.41 to -0.15; RR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17–1.48), and in the long term (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI, -0.46 to -0.24; RR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18–1.41).16

Comparisons of mental health quality of life over the short term (0-6 months), medium term (7-12 months), and long term (13-24 months) did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16 Comparisons of physical health quality of life over the short term and medium term did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16

Continue to: Significantly greater improvement...

Significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes was seen for adults treated with CCM in the short term (SMD = -0.30; 95% CI, -0.44 to -0.17; RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.21–1.87), in the medium term (SMD = -0.33; 95% CI, -0.47 to -0.19; RR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18-1.69), and in the long term (SMD = -0.20; 95% CI, -0.34 to -0.06; RR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42).16

A 2016 systematic review of 94 RCTs involving more than 25,000 patients also provided high-quality evidence that collaborative care yields small-to-moderate improvements in symptoms from mood disorders and mental health-related quality of life.15 A 2006 meta-analysis of 37 RCTs comprising 12,355 patients showed that collaborative care involving a case manager is more effective than standard care in improving depression outcomes at 6 months (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.32) and up to 5 years (SMD = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.001-0.31).21

Better care of mental health disorders also improves medical outcomes

Several trials have focused on jointly managing depression and a chronic physical condition such as chronic pain, diabetes, and coronary heart disease,22 demonstrating improved outcomes for both depression and the comanaged conditions.

- Chronic pain. When compared with usual care, collaborative care resulted in moderate reductions in both pain severity and associated disability (41.5% vs 17.3%; RR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6-3.2).23

- Diabetes. Patients managed collaboratively were more likely to have a decrease of ≥ 1% in the glycated hemoglobin level from baseline (36% vs 19%; P = .006).24

- Cardiovascular disease. Significant real-world risk reduction was achieved by improving blood pressure control (58% achieved blood pressure control compared with a projected target of 20%).22

IS THERE A COMMON THREAD AMONG SUCCESSFUL CCMs?

Attempts to identify commonalities between the many iterations of successful CCMs have produced varying results due to differing selections of relevant RCTs.25-29 However, a few common features have been identified:

- care managers assess symptoms at baseline and at follow-up using a standardized measure such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);

- care managers monitor treatment adherence;

- follow-up is active for at least 16 weeks;

- primary care and mental health providers actively engage in patient management; and

- mental health specialists regularly supervise care managers.

The one feature that is consistent with improved outcomes is the presence of the care manager.25-29

Continue to: The improvement associated...

The improvement associated with collaborative care is clinically meaningful to patients and physicians. In one RCT, collaborative care doubled response rates of depression treatment compared with usual care.3 Quality improvement data from real-world implementation of collaborative care programs suggests that similar outcomes can be achieved in a variety of settings.30

COST BENEFITS OF CCM

Collaborative care for depression is associated with lower health care costs.29,31

A meta-analysis of 57 RCTs in 2012 showed that CCM improves depression outcomes across populations, settings, and outcome domains, and that these results are achieved at little to no increase in treatment costs compared with usual care (Cohen’s d = 0.05; 95% CI, –0.02–0.12).26

When collaborative care was compared with routine care in an RCT involving 1801 primary care patients ≥ 60 years who were suffering from depression, a cost saving of $3363 per patient over 4 years was demonstrated in the intervention arm.31

A technical analysis of 94 RCTs in 2015 concluded that CCM is cost effective compared with usual care, with a range of $15,000 to $80,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained. These studies also indicated that organizations’ costs to implement CCM increase in the short term. Based on this analysis, organizations would need to invest between $3 to $22 per patient per month to implement and sustain CCMs, depending on the prevalence of depression in the population.29

Continue to: OTHER MODELS OF BHI

OTHER MODELS OF BHI

Higher levels of BHI such as co-location and integration do not have the same quality of evidence as CCM.

A 2009 Cochrane review of 42 studies involving 3880 patients found that mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care settings brought about significant reductions in primary care physician consultations (SMD = ‐0.17; 95% CI, ‐0.30 to ‐0.05); a relative risk reduction of 23% in psychotropic prescribing (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56–0.79); a decrease in prescribing costs (SMD = ‐0.22; 95% CI, ‐0.38 to ‐0.07); and a relative risk reduction in mental health referral of 87% (RR = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09–0.20) for the patients they were seeing.32 The authors concluded the changes were modest in magnitude and inconsistent across different studies.32

Embedding medical providers in behavior health centers—ie, the reverse co-location model—also has very limited evidence. An RCT involving 120 veterans found that patients enrolled in a reverse co-location clinic did significantly better than controls seen in a general care clinic in terms of continuity of care and preventive care such as screening for hypertension (84.7% vs 65.6%; X 2 = 5.9, P = .01), diabetes (71.2% vs 45.9%; X 2 = 7.9, P < .005), hepatitis (39% vs 14.8%; X 2 = 9, P = .003), and cholesterol (79.7% vs 57.4%; X 2 = 6.9, P = .009).33

HOW TO IMPLEMENT A SUCCESSFUL BHI PROGRAM

A demonstration and evaluation project involving 11 diverse practices in Colorado explored ways to integrate behavioral health in primary care. Five main themes emerged34,35:

- Frame integrated care as a necessary paradigm shift to patient-centered, whole-person health care.

- Define relationships and protocols up front, understanding that they will evolve.

- Build inclusive, empowered teams to provide the foundation for integration.

- Develop a change management strategy of continuous evaluation and course correction.

- Use targeted data collection pertinent to integrated care to drive improvement and impart accountability.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review has organized an extensive list of resources36 for implementing BHI models, a sampling of which is shown in TABLE 2.

Continue to: TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

There is high quality evidence that collaborative care works for the management of depression and anxiety disorder in primary care, and this is associated with significant cost savings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (FNU) Rajesh, MD, Main Campus Family Medicine Clinic, MetroHealth, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; frajesh@metrohealth.org

In a typical primary care practice, detecting and managing mental health problems competes with other priorities such as treating acute physical illness, monitoring chronic disease, providing preventive health services, and assessing compliance with standards of care.1 These competing demands for a primary care provider’s time, paired with limited mental health resources in the community, may result in suboptimal behavioral health care.1-3 Even when referrals are made to

Approximately 30% of adults with physical disorders also have one or more behavioral health conditions, such as anxiety, panic, mood, or substance use disorders.6 Although physical and behavioral health conditions are inextricably linked, their assessment and treatment get separated into different silos.7 Given that fewer than 20% of depressed patients are seen by a psychiatrist or psychologist,8 the responsibility of providing mental health care often falls on the primary care physician.8,9

Efforts to improve the treatment of common mental disorders in primary care have traditionally focused on screening for these disorders, educating primary care providers, developing treatment guidelines, and referring patients to mental health specialty care.10 However, behavioral health integration offers another way forward.

WHAT IS BEHAVIORAL HEALTH INTEGRATION?

Behavioral health integration (BHI) in primary care refers to primary care physicians and behavioral health clinicians working in concert with patients to address their primary care and behavioral health needs.11

Numerous overlapping terms have been used to describe BHI, and this has caused some confusion. In 2013, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) issued a lexicon standardizing the terminology used in BHI.11 The commonly used terms are

COORDINATED CARE AND THE COLLABORATIVE CARE MODEL

BHI at the level of coordinated care has almost exclusively been studied and practiced along the lines of the collaborative care model (CCM).14-16 This model represents an advanced level of coordinated care in the BHI continuum. The most substantial evidence for CCM lies in the management of depression and anxiety.14-16

Usual care involves the primary care physician and the patient. CCM adds 2 vital roles—a behavioral health care manager and a psychiatric consultant. A behavioral health care manager is typically a counselor, clinical social worker, psychologist, or psychiatric nurse who performs all care-management tasks including offering psychotherapy when that is part of the treatment plan.

Continue to: The care manager's functions include...

The care manager’s functions include systematic follow-up with structured monitoring of symptoms and treatment adherence, coordination and communication among care providers, patient education, and self-management support, including the use of motivational interviewing. The behavioral health care manager performs this systematic follow up by maintaining a patient “registry”—case-management software used in conjunction with, or embedded in, the practice electronic health record to track patients’ data and clinical outcomes, as well as to facilitate decision-making.

The care manager communicates with the psychiatrist, who offers suggestions for drug therapy, which is prescribed by the primary care physician. The care manager also regularly evaluates the patient’s status using a standardized scale, communicates these scores to the psychiatrist, and transmits any recommendations to the primary care physician (FIGURE 2).17

EVIDENCE FOR CCM

Collaborative and routine care were compared in a 2012 Cochrane review that included 79 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) involving 24,308 patients worldwide.16 Seventy-two of the 79 RCTs focused on patients with depression or depression with anxiety, while 6 studies included participants with only anxiety disorders.16 One additional study focused on mental health quality of life. (To learn about CCM and severe mental illness and substance use disorder, see “Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence.”18-20)

SIDEBAR

Less well studied: CCM and severe mental illness, alcohol dependence

Evidence for collaborative care in severe mental illness (SMI) is very limited. SMI is defined as schizophrenia or other schizophrenia-like psychoses (eg, schizophreniform and schizoaffective disorders), bipolar affective disorder, or other psychosis.

A 2013 Cochrane review identified only 1 RCT involving 306 veterans with bipolar disease.18 The review concluded that there was low-quality evidence that collaborative care led to a relative risk reduction of 25% for psychiatric admissions at Year 2 compared with standard care (RR = 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57-0.99).18

One 2017 RCT involving 245 veterans that looked at a collaborative care model for patients with severe mental illness found a modest benefit for physical health-related quality of life, but did not find any benefit in mental health outcomes.19

Alcohol dependence. There is very limited, but high-quality, evidence for the utility of CCM in alcohol dependence. In one RCT, 163 veterans were assigned to either CCM or referral to standard treatment in a specialty outpatient addiction treatment program. The CCM group had a significantly higher proportion of participants engaged in treatment over the study’s 26 weeks (odds ratio [OR] = 5.36; 95% CI, 2.99-9.59). The percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly lower in the CCM group (OR = 2.16; 95% CI, 1.27-3.66), while overall abstinence did not differ between groups.20

For adults with depression treated with the CCM, significantly greater improvement in depression outcome measures was seen in the short-term (standardized mean difference [SMD] = -0.34; 95% confidence interval [CI], -0.41 to -0.27; risk ratio [RR] = 1.32; 95% CI, 1.22-1.43), in the medium term (SMD = -0.28; 95% CI, -0.41 to -0.15; RR = 1.31; 95% CI, 1.17–1.48), and in the long term (SMD = -0.35; 95% CI, -0.46 to -0.24; RR = 1.29; 95% CI, 1.18–1.41).16

Comparisons of mental health quality of life over the short term (0-6 months), medium term (7-12 months), and long term (13-24 months) did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16 Comparisons of physical health quality of life over the short term and medium term did not show any significant difference between CCM and routine care.16

Continue to: Significantly greater improvement...

Significantly greater improvement in anxiety outcomes was seen for adults treated with CCM in the short term (SMD = -0.30; 95% CI, -0.44 to -0.17; RR = 1.50; 95% CI, 1.21–1.87), in the medium term (SMD = -0.33; 95% CI, -0.47 to -0.19; RR = 1.41; 95% CI, 1.18-1.69), and in the long term (SMD = -0.20; 95% CI, -0.34 to -0.06; RR = 1.26; 95% CI, 1.11–1.42).16

A 2016 systematic review of 94 RCTs involving more than 25,000 patients also provided high-quality evidence that collaborative care yields small-to-moderate improvements in symptoms from mood disorders and mental health-related quality of life.15 A 2006 meta-analysis of 37 RCTs comprising 12,355 patients showed that collaborative care involving a case manager is more effective than standard care in improving depression outcomes at 6 months (SMD = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.18-0.32) and up to 5 years (SMD = 0.15; 95% CI, 0.001-0.31).21

Better care of mental health disorders also improves medical outcomes

Several trials have focused on jointly managing depression and a chronic physical condition such as chronic pain, diabetes, and coronary heart disease,22 demonstrating improved outcomes for both depression and the comanaged conditions.

- Chronic pain. When compared with usual care, collaborative care resulted in moderate reductions in both pain severity and associated disability (41.5% vs 17.3%; RR = 2.4; 95% CI, 1.6-3.2).23

- Diabetes. Patients managed collaboratively were more likely to have a decrease of ≥ 1% in the glycated hemoglobin level from baseline (36% vs 19%; P = .006).24

- Cardiovascular disease. Significant real-world risk reduction was achieved by improving blood pressure control (58% achieved blood pressure control compared with a projected target of 20%).22

IS THERE A COMMON THREAD AMONG SUCCESSFUL CCMs?

Attempts to identify commonalities between the many iterations of successful CCMs have produced varying results due to differing selections of relevant RCTs.25-29 However, a few common features have been identified:

- care managers assess symptoms at baseline and at follow-up using a standardized measure such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9);

- care managers monitor treatment adherence;

- follow-up is active for at least 16 weeks;

- primary care and mental health providers actively engage in patient management; and

- mental health specialists regularly supervise care managers.

The one feature that is consistent with improved outcomes is the presence of the care manager.25-29

Continue to: The improvement associated...

The improvement associated with collaborative care is clinically meaningful to patients and physicians. In one RCT, collaborative care doubled response rates of depression treatment compared with usual care.3 Quality improvement data from real-world implementation of collaborative care programs suggests that similar outcomes can be achieved in a variety of settings.30

COST BENEFITS OF CCM

Collaborative care for depression is associated with lower health care costs.29,31

A meta-analysis of 57 RCTs in 2012 showed that CCM improves depression outcomes across populations, settings, and outcome domains, and that these results are achieved at little to no increase in treatment costs compared with usual care (Cohen’s d = 0.05; 95% CI, –0.02–0.12).26

When collaborative care was compared with routine care in an RCT involving 1801 primary care patients ≥ 60 years who were suffering from depression, a cost saving of $3363 per patient over 4 years was demonstrated in the intervention arm.31

A technical analysis of 94 RCTs in 2015 concluded that CCM is cost effective compared with usual care, with a range of $15,000 to $80,000 per quality-adjusted life year gained. These studies also indicated that organizations’ costs to implement CCM increase in the short term. Based on this analysis, organizations would need to invest between $3 to $22 per patient per month to implement and sustain CCMs, depending on the prevalence of depression in the population.29

Continue to: OTHER MODELS OF BHI

OTHER MODELS OF BHI

Higher levels of BHI such as co-location and integration do not have the same quality of evidence as CCM.

A 2009 Cochrane review of 42 studies involving 3880 patients found that mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions in primary care settings brought about significant reductions in primary care physician consultations (SMD = ‐0.17; 95% CI, ‐0.30 to ‐0.05); a relative risk reduction of 23% in psychotropic prescribing (RR = 0.67; 95% CI, 0.56–0.79); a decrease in prescribing costs (SMD = ‐0.22; 95% CI, ‐0.38 to ‐0.07); and a relative risk reduction in mental health referral of 87% (RR = 0.13; 95% CI, 0.09–0.20) for the patients they were seeing.32 The authors concluded the changes were modest in magnitude and inconsistent across different studies.32

Embedding medical providers in behavior health centers—ie, the reverse co-location model—also has very limited evidence. An RCT involving 120 veterans found that patients enrolled in a reverse co-location clinic did significantly better than controls seen in a general care clinic in terms of continuity of care and preventive care such as screening for hypertension (84.7% vs 65.6%; X 2 = 5.9, P = .01), diabetes (71.2% vs 45.9%; X 2 = 7.9, P < .005), hepatitis (39% vs 14.8%; X 2 = 9, P = .003), and cholesterol (79.7% vs 57.4%; X 2 = 6.9, P = .009).33

HOW TO IMPLEMENT A SUCCESSFUL BHI PROGRAM

A demonstration and evaluation project involving 11 diverse practices in Colorado explored ways to integrate behavioral health in primary care. Five main themes emerged34,35:

- Frame integrated care as a necessary paradigm shift to patient-centered, whole-person health care.

- Define relationships and protocols up front, understanding that they will evolve.

- Build inclusive, empowered teams to provide the foundation for integration.

- Develop a change management strategy of continuous evaluation and course correction.

- Use targeted data collection pertinent to integrated care to drive improvement and impart accountability.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review has organized an extensive list of resources36 for implementing BHI models, a sampling of which is shown in TABLE 2.

Continue to: TAKE-AWAY POINTS

TAKE-AWAY POINTS

There is high quality evidence that collaborative care works for the management of depression and anxiety disorder in primary care, and this is associated with significant cost savings.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rajesh (FNU) Rajesh, MD, Main Campus Family Medicine Clinic, MetroHealth, 2500 MetroHealth Drive, Cleveland, OH 44109; frajesh@metrohealth.org

1. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:150-154.

2. Rush A, Trivedi M, Carmody T, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:46-53.

3. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Bradford DW, Slubicki MN, McDuffie J, et al. Effects of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness. 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/smi-REPORT.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. Druss BG, von Esenwein S. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:145-153.

6. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental Disorders and Medical Comorbidity. Research Synthesis Report No. 21. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; February 2011.

7. Reed SJ, Shore KK, Tice JA. Effectiveness and value of integrating behavioral health into primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:691-692.

8. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55-61.

9. Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38632/. Accessed March 2, 2019.

10. Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss B, et al. Transforming mental health care at the interface with general medicine: report for the presidents commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:37-47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37.

11. Peek CJ; the National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. AHRQ. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

12. Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare and update throughout the document. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/A_Standard_Framework_for_Levels_of_Integrated_Healthcare.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

13. Integrating physical and behavioral health care: promising Medicaid models. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/8553-integrating-physical-and-behavioral-health-care-promising-medicaid-models.pdf. Published February 2014. Accessed May 29, 2019.

14. Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: the collaborative care model. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

15. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

16. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10.1002/14651858.cd006525.pub2.

17. Team Structure. University of Washington AIMs Center. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure. Published 2017.Accessed May 29, 2019.

18. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

19. Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, et al. Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:129-137.

20. Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto HSA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29:162-168.

21. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314-2321.

22. Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Magnan S, et al. Impact of a national collaborative care initiative for patients with depression and diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;15:77-85.

23. Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain. JAMA. 2009;301:2009-2110.

24. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611-2620.

25. Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, et al. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions. Med Care. 2013;51:922-930.

26. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;11:790-804.

27. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Rubenstein LV, Williams JW Jr, Danz M, et al. Determining key features of effective depression interventions. 2009. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/depinter.cfm. Accessed August 22, 2018.

28. Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E, et al. Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108114.

29. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Tice JA, Ollendorf DA, Reed SJ, et al. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BHI_Final_Report_0602151.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2018.

30. Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91-113.

31. Unützer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95-100.

32. Harkness EF, Bower PJ. On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000532.

33. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:861-868.

34. Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, Waller E, et al. Integrating behavioral and physical health care in the real world: early lessons from advancing care together. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:588-602.

35. Gold SB, Green LA, Peek CJ. From our practices to yours: key messages for the journey to integrated behavioral health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:25-34.

36. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CTAF_BHI_Action_Guide_060215.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019.

1. Rost K, Nutting P, Smith J, et al. The role of competing demands in the treatment provided primary care patients with major depression. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:150-154.

2. Rush A, Trivedi M, Carmody T, et al. One-year clinical outcomes of depressed public sector outpatients: a benchmark for subsequent studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:46-53.

3. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting. JAMA. 2002;288:2836-2845.

4. Department of Veterans Affairs. Bradford DW, Slubicki MN, McDuffie J, et al. Effects of care models to improve general medical outcomes for individuals with serious mental illness. 2011. https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/smi-REPORT.pdf. Accessed August 22, 2018.

5. Druss BG, von Esenwein S. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:145-153.

6. Druss BG, Walker ER. Mental Disorders and Medical Comorbidity. Research Synthesis Report No. 21. Princeton, NJ: The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; February 2011.

7. Reed SJ, Shore KK, Tice JA. Effectiveness and value of integrating behavioral health into primary care. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176:691-692.

8. Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, et al. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55-61.

9. Butler M, Kane RL, McAlpine D, et al. Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38632/. Accessed March 2, 2019.

10. Unützer J, Schoenbaum M, Druss B, et al. Transforming mental health care at the interface with general medicine: report for the presidents commission. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:37-47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.1.37.

11. Peek CJ; the National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. AHRQ. https://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/Lexicon.pdf. Published April 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

12. Heath B, Wise Romero P, Reynolds K. A standard framework for levels of integrated healthcare and update throughout the document. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/A_Standard_Framework_for_Levels_of_Integrated_Healthcare.pdf. Published March 2013. Accessed May 29, 2019.

13. Integrating physical and behavioral health care: promising Medicaid models. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/8553-integrating-physical-and-behavioral-health-care-promising-medicaid-models.pdf. Published February 2014. Accessed May 29, 2019.

14. Vanderlip ER, Rundell J, Avery M, et al. Dissemination of integrated care within adult primary care settings: the collaborative care model. SAMHSA-HRSA. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/integrated-care-models/APA-APM-Dissemination-Integrated-Care-Report.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

15. Gerrity M. Evolving models of behavioral health integration: evidence update 2010-2015. Milbank Memorial Fund. https://www.milbank.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Evolving-Models-of-BHI.pdf. Published May 2016. Accessed May 29, 2019.

16. Archer J, Bower P, Gilbody S, et al. Collaborative care for depression and anxiety problems. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10.1002/14651858.cd006525.pub2.

17. Team Structure. University of Washington AIMs Center. https://aims.uw.edu/collaborative-care/team-structure. Published 2017.Accessed May 29, 2019.

18. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

19. Kilbourne AM, Barbaresso MM, Lai Z, et al. Improving physical health in patients with chronic mental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78:129-137.

20. Oslin DW, Lynch KG, Maisto HSA, et al. A randomized clinical trial of alcohol care management delivered in Department of Veterans Affairs primary care clinics versus specialty addiction treatment. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;29:162-168.

21. Gilbody S, Bower P, Fletcher J, et al. Collaborative care for depression: a cumulative meta-analysis and review of longer-term outcomes. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:2314-2321.

22. Rossom RC, Solberg LI, Magnan S, et al. Impact of a national collaborative care initiative for patients with depression and diabetes or cardiovascular disease. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2017;15:77-85.

23. Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain. JAMA. 2009;301:2009-2110.

24. Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611-2620.

25. Miller CJ, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron BE, et al. Collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions. Med Care. 2013;51:922-930.

26. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;11:790-804.

27. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Rubenstein LV, Williams JW Jr, Danz M, et al. Determining key features of effective depression interventions. 2009. http://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/publications/esp/depinter.cfm. Accessed August 22, 2018.

28. Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E, et al. Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9:e108114.

29. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Tice JA, Ollendorf DA, Reed SJ, et al. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/BHI_Final_Report_0602151.pdf. Accessed August 27, 2018.

30. Rubenstein LV, Chaney EF, Ober S, et al. Using evidence-based quality improvement methods for translating depression collaborative care research into practice. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:91-113.

31. Unützer J, Katon WJ, Fan MY, et al. Long-term cost effects of collaborative care for late-life depression. Am J Manag Care. 2008;14:95-100.

32. Harkness EF, Bower PJ. On-site mental health workers delivering psychological therapy and psychosocial interventions to patients in primary care: effects on the professional practice of primary care providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD000532.

33. Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, et al. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:861-868.

34. Davis M, Balasubramanian BA, Waller E, et al. Integrating behavioral and physical health care in the real world: early lessons from advancing care together. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013;26:588-602.

35. Gold SB, Green LA, Peek CJ. From our practices to yours: key messages for the journey to integrated behavioral health. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30:25-34.

36. Institute for Clinical and Economic Review. Integrating behavioral health into primary care. 2015. https://icer-review.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/CTAF_BHI_Action_Guide_060215.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2019.

Beware the men with toupees

HISTORY: Treatment-refractory depression

Mr. S, age 78, has a history of depression that has not responded to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

According to his niece, Mr. S had become withdrawn, suspicious, and forgetful. Several times over the past year, police found him wandering the streets and brought him to the community hospital’s emergency room.

During one emergency room visit, he complained of decreased appetite, poor sleep, and depressed mood. He was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric unit, where he was treated with ECT and discharged on citalopram, 20 mg/d. His symptoms did not improve and he became ataxic and incontinent of urine.

Mr. S’ family placed him in a nursing home, where he became increasingly paranoid. The attending physician prescribed risperidone, 3 mg/d, with no effect. He was then transferred to our psychiatric facility.

At admission, Mr. S told us that a group of men disguised in toupees and mustaches were out to kill him. He said these men had recently killed his niece—with whom he had just spoken on the phone and had seen at the hospital. He suspected that these men were after his money, hired a woman to impersonate his niece and spy on him, and planned to bury his body and his niece’s in a remote place.

On evaluation, Mr. S was suspicious, guarded, and uncooperative, and often ended conversations abruptly. He denied auditory and visual hallucinations, was not suicidal or homicidal, and denied abusing drugs or alcohol. He said constant fear of his imminent murder left him feeling depressed.

Physical and neurologic exams were unremarkable except for mild ataxia. Mr. S’ Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score was 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment.

Mr. S’ history and behavior suggest depression with psychotic features. Do we have enough information for a diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S is displaying mood symptoms consistent with his prior diagnosis of depression, but with new-onset psychosis as well.

Because of Mr. S’ neurobiologic symptoms, it is improper to diagnose depression with psychotic features without first performing a full medical and neurologic workup. The differential diagnosis needs to include medical and neurologic diagnoses, including:

- delirium secondary to urinary tract infection

- Alzheimer’s and/or vascular dementia

- normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- substance abuse.

A complete dementia and delirium workup and detailed medical history are imperative.

FURTHER HISTORY: Risky behavior

Further history reveals that Mr. S had been having sexual intercourse with prostitutes since his early teens and that this habit continued into his 70s. He had been diagnosed with syphilis in his teens and again in his 50s. Both times he refused to complete the recommended penicillin regimen because he was embarrassed by the diagnosis and had falsely believed that a single penicillin injection would cure him.

Lab tests showed a white blood cell count of 3.5 and a weakly reactive serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) reading.

Reporting of syphilis cases in the United States began in 1941.1 At about that time, Yale University and the Mayo Clinic began conducting clinical trials of penicillin in syphilis treatment.2

Thanks to the advent of penicillin, syphilis incidence has declined dramatically since 1943, when 575,593 cases were reported.3 Only 5,979 cases were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000.4 A slight increase in cases, mainly among homosexual men, was reported in 2001.1,4

The AIDS epidemic and the emergence of crack/cocaine use5,6 were believed to have triggered a brief increase in cases that peaked in 1990. This was likely caused by the high-risk sexual behavior observed in individuals with sexually transmitted diseases and the practice of exchanging sex for drugs.6

Could Mr. S’ syphilis—inadequately treated in his youth—be causing his depression and paranoia decades later? If so, how would you confirm this finding?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S has a longstanding history of syphilis secondary to high-risk sexual activity. This, combined with the lab findings and his worsening depression and paranoia, points to possible neurosyphilis.

Syphilis, caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum., can traverse mucous membranes and abraded skin. Transmission is most common during sexual activity but also occurs through blood transfusions and nonsexual lesion contact and from mother to fetus.

Prevalence

- 6,103 cases reported in 2001

- More prevalent among men than women (2.1:1), probably because of elevated prevalence among homosexual men

- African-Americans accounted for 62% of cases in 2001. Prevalence in African–Americans that year was 16 times greater than in whites

Risk factors

- Presence of HIV infection or other sexually transmitted disease

- Unprotected sex

- Residence in urban areas

- Substance abuse

- Homosexuality

Source: References 5 and 6

Because syphilis and its psychiatric effects are relatively uncommon (Box 1), many psychiatrists do not consider neurosyphilis in high-risk patients who present with depression, dementia, or psychosis (Box 2).

HOW SYPHILIS BECOMES NEUROSYPHILIS

Primary syphilis incubates for 10 to 90 days following infection. After this period, an infectious chancre appears along with regional adenopathy. If untreated, the chancre will disappear but the infection will progress.

Secondary syphilis is characterized by skin manifestations and occasionally affects the joints, eyes, bones, kidneys, liver, and CNS. Common effects include condylomata—highly infectious warty lesions—and a diffuse maculopapular rash on the palms and soles. These lesions disappear if left untreated, but most patients then either enter syphilis’ latent stage or experience a potentially fatal relapse of secondary syphilis.5

Latent syphilis usually remains latent or resolves, but about one-third of patients with latent syphilis slowly progress to tertiary syphilis. Neurosyphilis, one of the main forms of tertiary syphilis, can surface 5 to 35 years after an untreated primary infection.7

There are four categories of neurosyphilis:

- General paresis results in dementia, changes in personality, transient hemiparesis, depression, and psychosis.

- Tabes dorsalis degenerates the posterior columns and dorsal root ganglia of the spinal cord. This results in ataxia, parasthesias, decreased proprioception and vibratory sense, Argyll Robertson pupil (an optical disorder in which the pupil does not react normally to light), neurogenic bladder, and sharp shooting pains throughout the body.

- Meningovascular neurosyphilis can result in cranial nerve abnormalities, symptoms of meningitis, and cerebral infarctions.

- Asymptomatic but with CSF positive for syphilis.

Neurosyphilis is fatal if untreated, and treatment usually does not eliminate symptoms but prevents further progression. Approximately 8% of patients with untreated primary syphilis develop neurosyphilis.5,7

Standard nontreponemal tests, such as the VDRL or rapid plasmin reagin, can be used to screen for syphilis. Because these tests often produce false positives, confirm positive results with a syphilis-specific test, such as the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, microhemagglutination assay for antibodies to T pallidum., and the T pallidum. hemagglutination assay.

If neurosyphilis is suspected, CSF testing is strongly recommended. Diagnostic findings include elevated white blood cell and protein counts and a positive VDRL. If the CSF is negative, refer the patient for treatment anyway because false negatives are common. Patients with consistent neurologic symptoms, positive VDRL and/or FTA-ABS, and negative CSF are diagnosed with neurosyphilis and warrant treatment.7

How would you manage Mr. S’ psychiatric symptoms concomitant with medical treatment of late-stage syphilis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Although no specific guidelines exist for treating psychosis secondary to neurosyphilis, atypical antipsychotics remain the first-line treatment. Atypicals do not interact significantly with penicillin and can be given safely with syphilis treatment. Atypicals also are better tolerated than typical antipsychotics and produce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms, which are common among older patients and those with neurologic diseases.

Screening for syphilis. Every patient with a history of high-risk sexual behavior who presents with new-onset dementia or psychosis should be screened for syphilis. Sexual history can be difficult to obtain from some patients and family members, so communication between providers becomes crucial. Obtain lab test results from other care team members to monitor compliance, and coordinate patient education with other doctors on safe sexual practices.

TREATMENT: Taking his medicine

Mr. S refused further testing and emergency conservatorship was sought. Citalopram was discontinued and risperidone was gradually increased to 6 mg at bedtime. He remained paranoid and delusional.

A brain MRI showed chronic ischemic small-vessel disease. HIV testing was negative, and serum FTA-ABS was reactive. CSF showed elevated protein and white blood cell count with a nonreactive VDRL and a reactive FTA-ABS. A diagnosis of neurosyphilis was made, and treatment was initiated with aqueous crystalline penicillin G, 4 million units every 4 hours for 2 weeks.

Mr. S was discharged back to the nursing home where his penicillin injections were continued. His paranoia diminished slightly but he remained ataxic, incontinent, and confused. He was discharged from the nursing home but needed confirmative HIV screening and repeated CSF testing to determine if syphilis treatment was effective.

Six months after treatment, Mr. S’ niece reports that his paranoia has decreased. He has not needed additional psychiatric hospitalizations.

Related resources

- Merck Manual. www.merck.com. Search: “syphilis”

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention—Syphilis elimination: History in the making. www.cdc.gov. Click on “Health Topics A-Z,” then click on “S” and find “syphilis.”

- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. www.niaid.nih.gov. Search: “syphilis”

Drug brand names

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Primary and secondary syphilis—United States, 2000-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:971-3.

2. Mandell GL, Petri WA. Antimicrobial agents: penicillins, cephalosporins, and other beta-lactam antibiotics. In:Hardman JG, Limbird LE, Molinoff PB, et al (eds) Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. (9th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1996;1073-4.

3. Lukehart SA, Holmes KK. Spirochetal diseases. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, et al (eds). Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. (14th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill, 1998;1023.-

4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2001 supplement, syphilis surveillance report. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats/2001syphilis.htm. Accessed October 10, 2003.

5. Jacobs RA. Infectious diseases: spirochetal. In: Tierney LM, McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA (eds). Current medical diagnosis and treatment. (39th ed). New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill, 2000;1376-86.

6. Hutto B. Syphilis in clinical psychiatry: a review. Psychosomatics. 2001;42:453-60.

7. Carpenter CJ, Lederman MM, Salata RA. Sexually transmitted diseases. In: Andreoli TE, Bennett JC, Carpenter CJ, Plum F (eds). Cecil essentials of medicine. (4th ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders Co, 1997;742-5.

HISTORY: Treatment-refractory depression

Mr. S, age 78, has a history of depression that has not responded to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

According to his niece, Mr. S had become withdrawn, suspicious, and forgetful. Several times over the past year, police found him wandering the streets and brought him to the community hospital’s emergency room.

During one emergency room visit, he complained of decreased appetite, poor sleep, and depressed mood. He was subsequently admitted to the psychiatric unit, where he was treated with ECT and discharged on citalopram, 20 mg/d. His symptoms did not improve and he became ataxic and incontinent of urine.

Mr. S’ family placed him in a nursing home, where he became increasingly paranoid. The attending physician prescribed risperidone, 3 mg/d, with no effect. He was then transferred to our psychiatric facility.

At admission, Mr. S told us that a group of men disguised in toupees and mustaches were out to kill him. He said these men had recently killed his niece—with whom he had just spoken on the phone and had seen at the hospital. He suspected that these men were after his money, hired a woman to impersonate his niece and spy on him, and planned to bury his body and his niece’s in a remote place.

On evaluation, Mr. S was suspicious, guarded, and uncooperative, and often ended conversations abruptly. He denied auditory and visual hallucinations, was not suicidal or homicidal, and denied abusing drugs or alcohol. He said constant fear of his imminent murder left him feeling depressed.

Physical and neurologic exams were unremarkable except for mild ataxia. Mr. S’ Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination score was 19/30, indicating moderate cognitive impairment.

Mr. S’ history and behavior suggest depression with psychotic features. Do we have enough information for a diagnosis?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S is displaying mood symptoms consistent with his prior diagnosis of depression, but with new-onset psychosis as well.

Because of Mr. S’ neurobiologic symptoms, it is improper to diagnose depression with psychotic features without first performing a full medical and neurologic workup. The differential diagnosis needs to include medical and neurologic diagnoses, including:

- delirium secondary to urinary tract infection

- Alzheimer’s and/or vascular dementia

- normal-pressure hydrocephalus

- substance abuse.

A complete dementia and delirium workup and detailed medical history are imperative.

FURTHER HISTORY: Risky behavior

Further history reveals that Mr. S had been having sexual intercourse with prostitutes since his early teens and that this habit continued into his 70s. He had been diagnosed with syphilis in his teens and again in his 50s. Both times he refused to complete the recommended penicillin regimen because he was embarrassed by the diagnosis and had falsely believed that a single penicillin injection would cure him.

Lab tests showed a white blood cell count of 3.5 and a weakly reactive serum venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) reading.

Reporting of syphilis cases in the United States began in 1941.1 At about that time, Yale University and the Mayo Clinic began conducting clinical trials of penicillin in syphilis treatment.2

Thanks to the advent of penicillin, syphilis incidence has declined dramatically since 1943, when 575,593 cases were reported.3 Only 5,979 cases were reported to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2000.4 A slight increase in cases, mainly among homosexual men, was reported in 2001.1,4

The AIDS epidemic and the emergence of crack/cocaine use5,6 were believed to have triggered a brief increase in cases that peaked in 1990. This was likely caused by the high-risk sexual behavior observed in individuals with sexually transmitted diseases and the practice of exchanging sex for drugs.6

Could Mr. S’ syphilis—inadequately treated in his youth—be causing his depression and paranoia decades later? If so, how would you confirm this finding?

Dr. Greenberg’s and Tampi’s observations

Mr. S has a longstanding history of syphilis secondary to high-risk sexual activity. This, combined with the lab findings and his worsening depression and paranoia, points to possible neurosyphilis.