User login

Young, pregnant, ataxic—and jilted

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

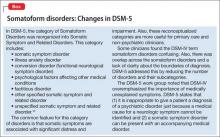

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Difficulty walking

Ms. M, age 15, is a pregnant, Spanish-speaking Guatemalan woman who is brought to obstetrics triage in a large academic medical center at 35 weeks gestational age. She complains of dizziness, tinnitus, left orbital headache, and difficulty walking.

The neurology service finds profound truncal ataxia, astasia-abasia, and buckling of the knees; a normal brain and spine MRI are not consistent with a neurologic etiology. Otolaryngology service evaluates Ms. M to rule out a cholesteatoma and suggests a head CT and endoscopy, which are normal.

Ms. M’s symptoms resolve after 3 days, although the gait disturbances persist. When no clear cause is found for her difficulty walking, the psychiatry service is consulted to evaluate whether an underlying psychiatric disorder is contributing to symptoms.

What could be causing Ms. M’s symptoms?

a) malingering

b) factitious disorder

c) undiagnosed neurologic disorder

d) conversion disorder

The authors’ observations

Women are vulnerable to a variety of psychiatric illnesses during pregnancy1 that have deleterious effects on mother, baby, and family.2-6 Although there is a burgeoning literature on affective and anxiety disorders occurring in pregnancy, there is a dearth of information about somatoform disorders.

HISTORY Abandonment

Ms. M reports that, although her boyfriend deserted her after learning about the unexpected pregnancy, she will welcome the baby and looks forward to motherhood. She seems unaware of the responsibilities of being a mother.

Ms. M acknowledges a history of depression and self-harm a few years earlier, yet says she feels better now and thinks that psychiatric care is unnecessary. Because she does not endorse a history of trauma or symptoms suggesting an affective, anxiety, or psychotic illness, the psychiatrist does not recommend treatment with psychotropic medication.

At age 5, Ms. M’s parents sent her to the United States with her aunt, hoping that she would have a better life than she would have had in Guatemala. Her aunt reports that Ms. M initially had difficulty adjusting to life in the United States without her parents, yet she has made substantial strides over the years and is now quite accustomed to the country. Her aunt describes Ms. M as an independent high school student who earns good grades.

During the interview, the psychiatrist observes that Ms. M exhibits childlike mannerisms, including sleeping with stuffed toys and coloring in Disney books with crayons. She also is indifferent to her gait difficulty, pregnancy, and psychosocial stressors. Her affect is inconsistent with the content of her speech and she is alexithymic.

Ms. M’s aunt reports that her niece is becoming more dependent on her, which is not consistent with her baseline. Her aunt also notes that several years earlier, Ms. M’s nephew was diagnosed with a cholesteatoma after he presented with similar symptoms.

The combination of (1) Ms. M’s clinical presentation, which was causing her significant impairment in her social functioning, (2) the incompatibility of symptoms with any recognized neurologic and medical disease, and (3) prior family experience with cholesteatoma leads the consulting psychiatrist to suspect conversion disorder. Ms. M’s alexithymia, indifference to her symptoms, and recent abandonment by the baby’s father also support a conversion disorder diagnosis.

From a psychodynamic perspective, the ataxia appears to be her way of protecting herself from the abandonment she is experiencing by being left again to “stand alone” by her boyfriend as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States. Her regressive behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.

The authors’ observations

This is the first case of psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy described in the literature. Authors have reported on pseudotoxemia,7 hyperemesis gravidarum,8 and pesudocyesis,9 yet there is a paucity of information on psychogenic gait disturbance during pregnancy. Ms. M’s case elucidates many of the clinical quandaries that occur when managing psychiatric illness—and, more specifically, conversion disorder— during pregnancy. Many women are hesitant to seek psychiatric treatment during pregnancy because of shame, stigma, and fear of loss of personal or parental rights10,11; it is not surprising that emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms.

Likely diagnosis

Conversion disorder is the presence of neurologic symptoms in the absence of a neurologic diagnosis that fully explains those symptoms. Conversion disorder, previously known as hysteria, is called functional neurologic symptom disorder in DSM-5 (Box).12 Symptoms are not feigned; instead, they represent “conversion” of emotional distress into neurologic symptoms.13,14 Although misdiagnosing conversion disorder in patients with true neurologic disease is uncommon, clinicians often are uncomfortable making the diagnosis until all medical causes have been ruled out.14 It is not always possible to find a psychological explanation for conversion disorder, but a history of childhood abuse, particularly sexual abuse, could play a role.14

Because of the variety of presentations, clinicians in all specialties should be familiar with somatoform disorders; this is especially important in obstetrics and gynecology because women are more likely than men to develop these disorders.15 It is important to consider that Ms. M is a teenager and somatoform disorders can present differently in adults. The diagnostic process should include a diligent somatic workup and a personal and social history to identify the patient’s developmental tasks, stressors, and coping style.15

How would you treat Ms. M?

a) destigmatize psychiatric illness and provide psychoeducation regarding treatment benefits

b) identify and treat any comorbid psychiatric disorders

c) maintain a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy

d) all of the above

TREATMENT Close follow-up

The psychiatrist recommends continued close psychiatric follow-up as well as multidisciplinary involvement, including physical therapy, neurology, and obstetrics.

Ms. M initially is resistant to psychiatric follow-up because she says that “people on the street” told her that, if she saw a psychiatrist, her baby would be taken away. After the psychiatrist explains that it is unlikely her baby would be taken away, Ms. M immediately appears relieved, smiles, and readily agrees to outpatient psychotherapy.

Over the next 24 hours, she continues to work with a physical therapist and her gait significantly improves. She is discharged home 2 days later with a walking aid (Zimmer frame) for assistance.

Four days later, however, Ms. M is readmitted with worsening ataxia. Her aunt reports that, at home, Ms. M’s regressed behaviors are worsening; she is sleeping in bed with her and had several episodes of enuresis at home.

Ms. M continues to deny psychiatric symptoms or anxiety about the delivery. Although she shows some improvement when working with physical therapists, they note that Ms. M is still unable to ambulate or stand on her own. The psychiatrist is increasingly concerned about her regressed behavior and continued ataxia.

A family meeting is held and the psychiatrist and social worker educate Ms. M and her aunt about conversion disorder, including how some emotionally distressed women communicate their feelings or troubled thoughts through physical symptoms and how that may apply to Ms. M. During the meeting, the team also destigmatizes psychiatric illness and treatment and provides psychoeducation regarding its benefits. The psychiatrist and social worker also provide a psychodynamic interpretation that her ataxia could be a way of protecting herself against the abandonment she is experiencing by being left to “stand alone” by her boyfriend— as she had been when her parents sent her to the United States, and that her behavior could be her way of securing her aunt’s love and support.Ms. M and her aunt both readily agree with this interpretation. The aunt notes that her niece is more anxious about motherhood than she acknowledges and is concerned that Ms. M expects her to be the primary caregiver for the baby. Those present note that Ms. M is becoming increasingly dependent on her aunt, and that it is important for her to retain her independence, especially once she becomes a mother.

Ms. M immediately begins to display more affect; she smiles and reports feeling relieved. Similar to the previous admission, her gait significantly improves over the next 2 days and she is discharged home with a walking aid.

The authors’ observations

A broad differential diagnosis and early multidisciplinary involvement might facilitate earlier diagnosis and treatment.16 Assessment of psychosocial stressors in the patient’s personal and family life, including circumstances around the pregnancy and the meaning of motherhood, as well as investigation of what the patient may gain from the sick role, are paramount. In Ms. M’s case, cultural background, separation from her parents at a young age, and recent abandonment by her boyfriend have contributed to her inability to “stand alone,” which manifested as ataxia. Young age, regressed behavior, and her minimization of stressors also point to her difficulty acknowledging and coping with psychosocial stressors.

Successful delivery of the diagnosis is key to treatment success. After building a therapeutic alliance, a multidisciplinary discussion should take place that allows the patient to understand the diagnosis and treatment plan.17,18 The patient and family should be reassured that the fetus is healthy and all organic causes of symptoms have been investigated.17 Although management of conversion disorder during pregnancy is similar to that in non-pregnant women, several additional avenues of investigation should be considered:

• Explore the psychodynamic basis of the disorder and the role of the pregnancy and motherhood.

• Identify any comorbid psychiatric disorders, particularly those specific to pregnancy or the postpartum period.

• Because of the shame and stigma associated with seeking psychiatric treatment during pregnancy,10,11 it is imperative to destigmatize treatment and provide psychoeducation regarding its benefits.

A treatment plan can then be developed that involves psychotherapy, psychoeducation, stress management, and, when appropriate, pharmacotherapy.17

Providing psychoeducation about postpartum depression and other perinatal psychiatric illness could be beneficial. Physical therapy often is culturally acceptable and can help re-establish healthy patterns of motor function.19 Ms. M’s gait showed some improvement with physical therapy as part of the multidisciplinary approach, which also should include a thorough medical workup. Appropriate psychiatric treatment can help patients give up the sick role and return to their previous level of functioning.17

Maintain close communication with the outpatient perinatal care team as they monitor the patient’s parenting capacity. The outpatient perinatal care team also should engage pregnant or postpartum women in prioritizing their emotional well-being and encourage outpatient mental health treatment. Despite a dearth of data on the regressive symptoms and prognosis for future pregnancies, it is important to monitor maternal capacity and discuss the possibility of symptom recurrence.

OUTCOME Healthy baby

Three days later, Ms. M returns in labor with improved gait yet still using a walking aid. She has a normal vaginal delivery of a healthy baby boy at 37 weeks’ gestational age.

After the birth, Ms. M reports feeling well and enjoying motherhood, and denies psychiatric symptoms. She is ambulating without assistance within hours of delivery. This spontaneous resolution of symptoms could have been because of the psychodynamically oriented multidisciplinary approach to her care, which may have helped her realize that she did not have to “stand alone” as she embarked on motherhood.

Before being discharged home, Ms. M and her aunt meet with the inpatient obstetric social worker to assess Ms. M’s ability to care for the baby and discuss the importance of continued emotional support. The social worker does not contact the Department of Children and Families because Ms. M is walking independently and not endorsing or exhibiting regressive behaviors. Ms. M also reports that she will ask her aunt to take care of the baby should ataxia recur. Her aunt reassures the social workers that she will encourage Ms. M to attend outpatient psychotherapy and will contact the social worker if she becomes concerned about Ms. M’s or the baby’s well-being.

During her postpartum obstetric visit, Ms. M is walking independently and does not exhibit or endorse neurologic symptoms. The social worker provides psychoeducation about the importance of outpatient psychotherapy and schedules an initial appointment; Ms. M does not attend outpatient psychotherapy after discharge.

Bottom Line

Consider conversion disorder in obstetric patients who present with ataxia without a neurologic cause. Management involves a proactive and multidisciplinary approach that includes a thorough medical workup and assessment of psychosocial stressors and psychodynamic factors, particularly those related to the pregnancy. Early identification and delivery of the diagnosis, destigmatization, and provision of appropriate psychiatric treatment can facilitate treatment success.

Disclosures

Dr. Byatt has received grant funding/support for this project from the National Center for Research Resources and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant KL2TR000160. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Dr. Toor reports no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or manufacturers of competing products.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.

1. Vesga-Lopez O, Blanco C, Keyes K, et al. Psychiatric disorders in pregnant and postpartum women in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):805-815.

2. Britton HL, Gronwaldt V, Britton JR. Maternal postpartum behaviors and mother-infant relationship during the first year of life. J Pediatr. 2001;138(6):905-909.

3. Deave T, Heron J, Evans J, et al. The impact of maternal depression in pregnancy on early child development. BJOG. 2008;115(8):1043-1051.

4. Paulson JF, Keefe HA, Leiferman JA. Early parental depression and child language development. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(3):254-262.

5. Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, et al. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160(5 pt 1):1107-1111.

6. Forman DR, O’Hara MW, Stuart S, et al. Effective treatment for postpartum depression is not sufficient to improve the developing mother-child relationship. Dev Psychopathol. 2007;19(2):585-602.

7. Brady WJ Jr, Huff JS. Pseudotoxemia: new onset psychogenic seizure in third trimester pregnancy. J Emerg Med. 1997;15(6):815-820.

8. el-Mallakh RS, Liebowitz NR, Hale MS. Hyperemesis gravidarum as conversion disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1990; 178(10):655-659.

9. Paulman PM, Sadat A. Pseudocyesis. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(5):575-576.

10. Dennis CL, Chung-Lee L. Postpartum depression help-seeking barriers and maternal treatment p: a qualitative systematic review. Birth. 2006;33(4):323-331.

11. Byatt N, Simas TA, Lundquist RS, et al. Strategies for improving perinatal depression treatment in North American outpatient obstetric settings. J Psychosom Obstetr Gynaecol. 2012;33(4):143-161.

12. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

13. Feinstein A. Conversion disorder: advances in our understanding. CMAJ. 2011;183(8):915-920.

14. Nicholson TR, Stone J, Kanaan RA. Conversion disorder: a problematic diagnosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(11):1267-1273.

15. Bitzer J. Somatization disorders in obstetrics and gynecology. Arch Womens Mental health, 2003;6(2):99-107.

16. Smith HE, Rynning RE, Okafor C, et al. Evaluation of neurologic deficit without apparent cause: the importance of a multidisciplinary approach. J Spinal Cord Med. 2007;30(5):509-517.

17. Hinson VK, Haren WB. Psychogenic movement disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(8):695-700.

18. Oyama O, Paltoo C, Greengold J. Somatoform disorders. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(9):1333-1338.

19. Ness D. Physical therapy management for conversion disorder: case series. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):30-39.

Hospitalized, elderly, and delirious: What should you do for these patients?

Delirium is a common condition in hospitalized older patients. Often, a report of a “change in mental status” is the reason geriatric patients are sent to the emergency room for evaluation, although delirium also can develop after admission.

Delirium is a marker of underlying medical illness that needs careful workup and treatment. The condition can be iatrogenic, resulting from prescribed medication or a surgical procedure; most often, it is the consequence of multiple factors. Delirium can be expensive, because it increases hospital length of stay and overall costs—particularly if the patient is discharged to a nursing facility, not to home. Patients with delirium are at higher risk of death.

Delirium often goes unrecognized by physicians and nursing staff, and is not documented in medical records. Educating the medical staff on the identification and management of delirium is a key role for consulting psychiatrists.

CASE: Confused and agitated

Ms. T, a 93-year-old resident of an assisted living facility with a history of three

cerebral vascular accidents, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, multiple deep venous thromboses, blindness in her right eye, and deafness in her right ear without a hearing aid, is brought to the hospital after a syncopal episode lasting 10 minutes that was followed by slurred speech, confusion, and transient hypotension. Her dentist recently started her on azithromycin.

In the emergency room, Ms. T’s elevated blood pressure is managed with hydralazine and diltiazem. A CT scan of the head rules out hemorrhagic stroke. Complete blood count and tests of electrolytes, vitamin B12, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are within normal limits; urinalysis is negative for urinary tract infection.

Ms. T is noted to be in and out of sleep, with some confusion. She is maintained without oral food or fluids because of concerns about her ability to swallow. After 5 or 6 hours in the ER, Ms. T is transferred to a medical unit, where she becomes agitated and paranoid, with the delusion that her daughter is an impostor. She yells, is combative, and refuses medication.

Her confusion and behaviors become worse at night: She pulls out her IV line and telemetry leads. Blood pressure remains elevated, for which she receives additional doses of hydralazine.

For behavioral management, the medical team orders a one-time IM dose of haloperidol and starts her on risperidone, 0.5 mg every 4 hours as needed, which Ms. T refuses to take. She is incontinent and has foul-smelling urine.

Ms. T’s family is shocked at her condition; nursing staff is frustrated. With her worsening paranoia, delusions, and combative behaviors towards the nursing staff, psychiatry is consulted.

How to recognize and diagnose

The Box lists DSM-5 criteria for delirium.1 The key feature is a disturbance in attention—what was referred to in DSM-IV-TR as “disturbance in consciousness.” That finding contrasts with what is seen in dementia, with its hallmark memory impairment and chronic deterioration.

In a hospital setting, the question is often asked: Does this patient have dementia or delirium? In many cases, the answer is both, because preexisting cognitive impairment is an important risk factor for delirium.

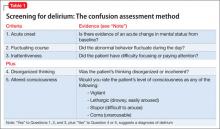

In addition to the standard clinical interview, several screening instruments or delirium rating scales have been developed. The most commonly used (Table 1) is the Confusion Assessment Method developed by Inouye and colleagues.2

Subtypes of delirium have been described, largely based on motor activity. Patients can present as hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, or neither.3 Psychiatrists are more likely to be consulted regarding patients with hyperactive delirium, because they are the ones who scream, pull out their IV line, hallucinate, and are delusional, insisting they “have to go home”—such as the patient described in the case above.

Patients with hypoactive delirium often, on the other hand, are difficult to recognize; they present with lethargy, drowsiness, apathy, and confusion. They become withdrawn and answer slowly4; often, psychiatry is consulted to assess them for depression.

Delirium can be difficult to diagnose in patients with underlying dementia, who are not able to provide information. In such cases, obtaining collateral information from a family member or primary caretaker is crucial. Knowing the patient’s baseline helps to determine whether there has been an acute change in mental status.

CASE CONTINUED: Acute mental status changes

Ms. T’s daughter reports that her mother has not been in this condition before. At baseline, Ms. T has had memory problems but no paranoia, delusions, or agitated behaviors. Her daughter also reports that Ms. T has visual and hearing impairments and is not wearing her hearing aid.

The acute change in mental status and the perceptual disturbances indicate that Ms. T has delirium, not dementia.

Who is likely to develop delirium?

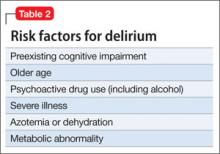

Risk factors for delirium (Table 2) include preexisting cognitive impairment, older age, vision and hearing impairment, use of psychoactive drugs, severe illness, azotemia and dehydration, a metabolic abnormality, and infection. Male sex also seems to be a risk factor, perhaps because men are more likely to abuse alcohol before admission.

Many patients become delirious after starting a new medication. An experienced geriatrician teaches that the main causes of delirium are “drugs, drugs, drugs, infections, and everything else” (Kenneth Rockwood, MD, personal communication, 2012). At admission, urinary tract infection and pneumonia are common causes of delirium, especially in geriatric patients.

What is the clinical course?

The clinical course varies widely. Delirium often is the reason that a patient is brought to the hospital, presenting with the condition at admission or early in hospitalization. The highest incidence among surgical patients appears to be on the third postoperative day—in some cases because of alcohol or drug withdrawal.

As noted in the DSM-5 criteria, delirium often comes on acutely, over hours or days. Symptoms can persist for weeks after initial onset of episodes of delirium.5 Symptoms fluctuate over the course of the day; at times, they can be missed if a provider sees the patient only while she (he) is clearer and doesn’t review nursing notes from other shifts.

How does delirium affect outcome?

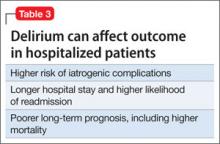

Delirium has been shown to be associated with prolonged hospital stay (21 days, compared with 11 days in the absence of delirium), functional decline during hospitalization, and increased admission to long-term care (36% compared with 13%).6 In a study by O’Keefe and Lavan,6 delirious patients were more likely to sustain falls and to develop urinary incontinence, pressure sores, and other complications during hospitalization.

Older patients with delirium superimposed on dementia had a more than twofold increased risk of mortality compared with patients with dementia alone or with neither dementia nor delirium.7 Rockwood found that an episode of delirium was associated with a much higher rate of subsequent dementia.8

Think of an acute medical illness as a “stress test” for the brain, such that, if the patient develops delirium, it suggests an underlying brain disease that was not evident before the acute episode. After hip fracture, for example, delirium was independently associated with poor functional recovery at 1 month9 and at 2 years.10

Older patients admitted to a skilled nursing facility with delirium are more likely to experience one or more complications (73% compared with 41%).11 In the study by Marcantonio and colleagues, patients with delirium were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized again within 30 days (30% and 13%), and less than half as likely to be discharged to the community (30% and 73%). Table 3 summarizes the impact of delirium on outcomes.

Appropriate management steps

Identifying and treating underlying medical illness is the definitive treatment for delirium; in a geriatric patient with multiple medical comorbidities the pathogenesis often is multifactorial or a definitive precipitant cannot always be identified.12

Managing a patient with delirium includes both non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions, which should be considered first-line, and pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions include, but are not limited to:

• support and close observation by nursing staff

• placing a clock or calendar in the room

• frequent reorientation and reminders

• placing familiar possessions in the room

• putting the patient in an isolated room with a window

• regulating the sleep-wake cycle.4

Pharmacotherapeutic intervention in delirium should be used for behavioral symptoms, but only for the minimum duration necessary4 and preferably oral or IV. No drugs are FDA-approved for delirium, which means that use of any agent is off-label.13

Antipsychotics are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for delirium in most settings. The use of antipsychotics relates to the dopamine excess-acetylcholine deficiency hypothesis of delirium pathophysiology.12 Haloperidol remains the first-line agent because it is available in multiple dosages and can be given by various routes. IV haloperidol appears to carry less risk of extrapyramidal symptoms than oral haloperidol does but, as with all antipsychotics, its use warrants monitoring for QTc prolongation.12

Studies have not shown that atypical antipsychotics are superior to typical antipsychotics for delirium. Multiple studies have shown that atypicals are as efficacious as haloperidol.

Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal. A Cochrane review found no evidence that benzodiazepines were helpful in treating delirium unrelated to alcohol withdrawal.14 In some studies, benzodiazepines were associated with an increased risk of delirium, especially in patients in the intensive care unit.15

More recently, cholinesterase inhibitors have been used to treat delirium. The reasoning behind their use is the hypothesis of a central cholinergic deficiency in delirium.12 Regrettably, there have been few well-conducted studies of these agents in delirium, and a Cochrane review found no significant benefit for cholinesterase inhibitors.16 With the same hypothesis in mind, anticholinergic medications in patients with delirium should be avoided because these agents could exacerbate delirium by further decreasing the acetylcholine level.

Because delirium is common in the hospitalized population (especially older patients), a number of studies have examined strategies to prevent or reduce its development. Inouye and colleagues conducted a controlled clinical trial, in which they intervened to reduce six risk factors for delirium: cognitive impairment, sleep deprivation, immobility, visual and hearing impairment, and dehydration in hospitalized geriatric patients. The number and duration of events of delirium were significantly lower in the intervention group.17

Brummel et al reported that reducing modifiable risk factors in intensive care unit patients—including sedation management, minimizing deliriogenic medications (anticholinergics, antihistamines), minimizing sleep disruption, and encouraging early mobility—could prevent or reduce the incidence of delirium.15

CASE CONCLUDED: Return to baseline

Ms. T’s medications are minimized or discontinued, including azithromycin, based on case reports in the literature. She is stabilized hemodynamically.

Clinicians educate Ms. T’s family about delirium. To address Ms. T’s aggressive and paranoid behaviors, clinicians request that a family member is present to reassure Ms. T. She is continued on low-dose haloperidol. The family also is asked to bring Ms. T’s hearing aid and eyeglasses.

MRI is performed after Ms. T’s behavior is under control. The scan is negative for a new stroke.

Repeat blood tests the following day show an elevated white blood cell count; urinalysis is positive for a urinary tract infection. Ms. T is started on antibiotics. Subsequent urine culture shows no bacterial growth; the antibiotics are stopped after 3 days.

Ms. T slowly improves. According to her family, she is back at baseline in 3 or 4 days.

This case illustrates the complexity of trying to identify the precise cause of delirium among the many that could be involved. Often, no single cause can be found.18

Bottom Line

Delirium is a common and potentially life-threatening condition in hospitalized geriatric patients. General hospital psychiatrists should know how to recognize and treat the condition in collaboration with their medical colleagues.

Related Resources

- Treating delirium: a quick reference guide. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1662986.

- Cook IA. Guideline watch: practice guidelines for the treatment of patients with delirium. http://psychiatryonline.org/content.aspx?bookid=28§ionid=1681952.

- Fearing MA, Inouye SK. Delirium. In: Blazer DG, Steffens D, eds. The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of geriatric psychiatry. 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2009:229-241.

- Ghandour A, Saab R, Mehr D. Detecting and treating delirium—key interventions you may be missing. J Fam Pract. 2011;60(12):726-734.

- Leentjens AF, Rundell J, Rummans T, et al. Delirium: an evidence-based medicine (EBM) monograph for psychosomatic medicine practice. J Psychosom Res. 2012;73:149-152.

- Liptzin B, Jacobson SA. Delirium. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2009:4066-4073.

Drug Brand Names

Azithromycin • Zithromax Hydralazine • Apresoline

Diltiazem • Cardizem Risperidone • Risperdal

Haloperidol • Haldo

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Featured Audio

Benjamin Liptzin, MD, describes the distinction between dementia and delirium. Dr. Liptzin is Chair of Psychiatry, Baystate Medical Center, Springfield, Massachusetts, and Professor and Deputy Chair, Department of Psychiatry, Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, et al. Clarifying confusion: The Confusion Assessment Method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:941-948.

3. Liptzin B, Levkoff SE. An empirical study of delirium subtypes. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:843-845.

4. Martins S, Fernandes L. Delirium in elderly people: a review. Front Neurol. 2012;3:101.

5. Levkoff SE, Liptzin B, Evans D, et al. Progression and resolution of delirium in elderly patients hospitalized for acute care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1994;2:230-238.

6. O’Keefe S, Lavan J. The prognostic significance of delirium in older hospitalized patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:247-248.

7. Tsai MC, Weng HH, Chou SY, et al. One-year mortality of elderly inpatients with delirium, dementia or depression seen by a consultation-liaison service. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:433-438.

8. Rockwood K, Cosway S, Carver D, et al. The risk of dementia and death after delirium. Age Ageing. 1999;28:551-556.

9. Marcantonio E, Flacker JM, Michaels M, et al. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:618-624.

10. Dolan MM, Hawkes WG, Zimmerman SI, et al. Delirium on hospital admission in aged hip fracture patients: prediction of mortality and 2-year functional outcomes. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2000;55:M27-M34.

11. Marcantonio ER, Kiely DK, Simon SE, et al. Outcomes of elders admitted to post-acute facilities with delirium. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:963-969.

12. Bledowski J, Trutia A. A review of pharmacologic management and prevention strategies of delirium in the intensive care unit. Psychosomatics. 2012;53:203-211.

13. Breitbart W, Alici-Evcimen Y. Why off-label antipsychotics remain first-choice drugs for delirium. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(9):49-63.

14. Lonergan E, Luxenberg J, Areosa Sastre A. Benzodiazepines for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(4):CD006379. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006379.pub3.

15. Brummel NE, Girard TD. Preventing delirium in the ICU. Crit Care Clin. 2013;(29):51-65.

16. Overshott R, Karim S, Burns A. Cholinesterase inhibitors for delirium. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(1):CD005317. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005317.

17. Inouye SK, Bogardus ST, Charpentier PA, et al. A multicomponent intervention to prevent delirium in hospitalized older patients. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:669-676.

18. Francis J, Martin D, Kapoor WN. A prospective study of delirium in hospitalized elderly. JAMA. 1990;263:1097-1101.

Delirium is a common condition in hospitalized older patients. Often, a report of a “change in mental status” is the reason geriatric patients are sent to the emergency room for evaluation, although delirium also can develop after admission.

Delirium is a marker of underlying medical illness that needs careful workup and treatment. The condition can be iatrogenic, resulting from prescribed medication or a surgical procedure; most often, it is the consequence of multiple factors. Delirium can be expensive, because it increases hospital length of stay and overall costs—particularly if the patient is discharged to a nursing facility, not to home. Patients with delirium are at higher risk of death.

Delirium often goes unrecognized by physicians and nursing staff, and is not documented in medical records. Educating the medical staff on the identification and management of delirium is a key role for consulting psychiatrists.

CASE: Confused and agitated

Ms. T, a 93-year-old resident of an assisted living facility with a history of three

cerebral vascular accidents, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, multiple deep venous thromboses, blindness in her right eye, and deafness in her right ear without a hearing aid, is brought to the hospital after a syncopal episode lasting 10 minutes that was followed by slurred speech, confusion, and transient hypotension. Her dentist recently started her on azithromycin.

In the emergency room, Ms. T’s elevated blood pressure is managed with hydralazine and diltiazem. A CT scan of the head rules out hemorrhagic stroke. Complete blood count and tests of electrolytes, vitamin B12, and thyroid-stimulating hormone are within normal limits; urinalysis is negative for urinary tract infection.

Ms. T is noted to be in and out of sleep, with some confusion. She is maintained without oral food or fluids because of concerns about her ability to swallow. After 5 or 6 hours in the ER, Ms. T is transferred to a medical unit, where she becomes agitated and paranoid, with the delusion that her daughter is an impostor. She yells, is combative, and refuses medication.

Her confusion and behaviors become worse at night: She pulls out her IV line and telemetry leads. Blood pressure remains elevated, for which she receives additional doses of hydralazine.

For behavioral management, the medical team orders a one-time IM dose of haloperidol and starts her on risperidone, 0.5 mg every 4 hours as needed, which Ms. T refuses to take. She is incontinent and has foul-smelling urine.

Ms. T’s family is shocked at her condition; nursing staff is frustrated. With her worsening paranoia, delusions, and combative behaviors towards the nursing staff, psychiatry is consulted.

How to recognize and diagnose

The Box lists DSM-5 criteria for delirium.1 The key feature is a disturbance in attention—what was referred to in DSM-IV-TR as “disturbance in consciousness.” That finding contrasts with what is seen in dementia, with its hallmark memory impairment and chronic deterioration.

In a hospital setting, the question is often asked: Does this patient have dementia or delirium? In many cases, the answer is both, because preexisting cognitive impairment is an important risk factor for delirium.

In addition to the standard clinical interview, several screening instruments or delirium rating scales have been developed. The most commonly used (Table 1) is the Confusion Assessment Method developed by Inouye and colleagues.2

Subtypes of delirium have been described, largely based on motor activity. Patients can present as hyperactive, hypoactive, mixed, or neither.3 Psychiatrists are more likely to be consulted regarding patients with hyperactive delirium, because they are the ones who scream, pull out their IV line, hallucinate, and are delusional, insisting they “have to go home”—such as the patient described in the case above.

Patients with hypoactive delirium often, on the other hand, are difficult to recognize; they present with lethargy, drowsiness, apathy, and confusion. They become withdrawn and answer slowly4; often, psychiatry is consulted to assess them for depression.

Delirium can be difficult to diagnose in patients with underlying dementia, who are not able to provide information. In such cases, obtaining collateral information from a family member or primary caretaker is crucial. Knowing the patient’s baseline helps to determine whether there has been an acute change in mental status.

CASE CONTINUED: Acute mental status changes

Ms. T’s daughter reports that her mother has not been in this condition before. At baseline, Ms. T has had memory problems but no paranoia, delusions, or agitated behaviors. Her daughter also reports that Ms. T has visual and hearing impairments and is not wearing her hearing aid.

The acute change in mental status and the perceptual disturbances indicate that Ms. T has delirium, not dementia.

Who is likely to develop delirium?

Risk factors for delirium (Table 2) include preexisting cognitive impairment, older age, vision and hearing impairment, use of psychoactive drugs, severe illness, azotemia and dehydration, a metabolic abnormality, and infection. Male sex also seems to be a risk factor, perhaps because men are more likely to abuse alcohol before admission.

Many patients become delirious after starting a new medication. An experienced geriatrician teaches that the main causes of delirium are “drugs, drugs, drugs, infections, and everything else” (Kenneth Rockwood, MD, personal communication, 2012). At admission, urinary tract infection and pneumonia are common causes of delirium, especially in geriatric patients.

What is the clinical course?

The clinical course varies widely. Delirium often is the reason that a patient is brought to the hospital, presenting with the condition at admission or early in hospitalization. The highest incidence among surgical patients appears to be on the third postoperative day—in some cases because of alcohol or drug withdrawal.

As noted in the DSM-5 criteria, delirium often comes on acutely, over hours or days. Symptoms can persist for weeks after initial onset of episodes of delirium.5 Symptoms fluctuate over the course of the day; at times, they can be missed if a provider sees the patient only while she (he) is clearer and doesn’t review nursing notes from other shifts.

How does delirium affect outcome?

Delirium has been shown to be associated with prolonged hospital stay (21 days, compared with 11 days in the absence of delirium), functional decline during hospitalization, and increased admission to long-term care (36% compared with 13%).6 In a study by O’Keefe and Lavan,6 delirious patients were more likely to sustain falls and to develop urinary incontinence, pressure sores, and other complications during hospitalization.

Older patients with delirium superimposed on dementia had a more than twofold increased risk of mortality compared with patients with dementia alone or with neither dementia nor delirium.7 Rockwood found that an episode of delirium was associated with a much higher rate of subsequent dementia.8

Think of an acute medical illness as a “stress test” for the brain, such that, if the patient develops delirium, it suggests an underlying brain disease that was not evident before the acute episode. After hip fracture, for example, delirium was independently associated with poor functional recovery at 1 month9 and at 2 years.10

Older patients admitted to a skilled nursing facility with delirium are more likely to experience one or more complications (73% compared with 41%).11 In the study by Marcantonio and colleagues, patients with delirium were more than twice as likely to be hospitalized again within 30 days (30% and 13%), and less than half as likely to be discharged to the community (30% and 73%). Table 3 summarizes the impact of delirium on outcomes.

Appropriate management steps

Identifying and treating underlying medical illness is the definitive treatment for delirium; in a geriatric patient with multiple medical comorbidities the pathogenesis often is multifactorial or a definitive precipitant cannot always be identified.12

Managing a patient with delirium includes both non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions, which should be considered first-line, and pharmacotherapeutic interventions. Non-pharmacotherapeutic interventions include, but are not limited to:

• support and close observation by nursing staff

• placing a clock or calendar in the room

• frequent reorientation and reminders

• placing familiar possessions in the room

• putting the patient in an isolated room with a window

• regulating the sleep-wake cycle.4

Pharmacotherapeutic intervention in delirium should be used for behavioral symptoms, but only for the minimum duration necessary4 and preferably oral or IV. No drugs are FDA-approved for delirium, which means that use of any agent is off-label.13

Antipsychotics are the mainstay of pharmacotherapy for delirium in most settings. The use of antipsychotics relates to the dopamine excess-acetylcholine deficiency hypothesis of delirium pathophysiology.12 Haloperidol remains the first-line agent because it is available in multiple dosages and can be given by various routes. IV haloperidol appears to carry less risk of extrapyramidal symptoms than oral haloperidol does but, as with all antipsychotics, its use warrants monitoring for QTc prolongation.12

Studies have not shown that atypical antipsychotics are superior to typical antipsychotics for delirium. Multiple studies have shown that atypicals are as efficacious as haloperidol.

Benzodiazepines are the treatment of choice for delirium caused by alcohol withdrawal. A Cochrane review found no evidence that benzodiazepines were helpful in treating delirium unrelated to alcohol withdrawal.14 In some studies, benzodiazepines were associated with an increased risk of delirium, especially in patients in the intensive care unit.15