User login

Veterans as Caregivers:Those Who Continue to Serve

More than 20% of the U.S. population will be aged ≥ 65 years by 2030, an increase from 13% in 2012.1 The likelihood of needing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) increases with age.2 People who need such assistance often depend on informal and unpaid assistance from friends and family. In 2009, about 65.7 million Americans (28.5%) provided informal care for people with an illness or disability, and that number only is expected to rise.3 These informal caregivers provide up to 80% of the total care hours needed by community-dwelling older adults—an estimated economic value of $450 billion in unpaid contributions in 2009.4,5

Caregiving can lead to significant physical, psychological, social, and financial burdens.6 The caregiving burden is associated with a host of adverse health behaviors and outcomes such as poor diet, lack of exercise and sleep, smoking, decreased participation in preventive health care, anxiety, depression, relationship difficulties, employment disruption, financial hardship, suicide, and higher mortality compared with that of noncaregivers.6-10 Additionally, care recipients are at increased risk for abuse or neglect when the caregiver is experiencing a significant burden.11 Therefore, efforts to improve caregiver support are important for both partners in the caregiver/care recipient dyad.

Caregiver support is beneficial to the health of caregivers and care recipients.10,12 For example, the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) program has been shown to reduce the stress of informal caregiving and the risk of depression in caregivers.13,14 This program showed similar effects when implemented within the VHA.14 In the Partners in Dementia Care project, the VHA and Alzheimer’s Association coordinated care and support for veterans with dementia and their family and friends. This intervention resulted in lower caregiver strain and depression scores among participants.15

With a growing medical literature that shows the benefits of caregiver support interventions, the VHA developed a robust support program for informal caregivers of veterans. The VA caregiver support website (www.caregiver.va.gov) provides information and resources targeted to caregivers for veterans, including psychosocial and functional support for caregivers. The psychosocial support provided by the VA includes caregiver education, counseling, access to caregiver support coordinators, a caregiver support line, support groups, and referral to community support organizations.16 Functional support on the site includes financial assistance toward skilled home care, home hospice care, adult day care, home-based primary care, homemaker and home health aide services, telehealth, and respite care.16 Veterans who are caregiving for nonveterans have access to VHA psychosocial support but not to functional support services. For these veterans, functional caregiver support must come from family or referral to community organizations.

Background

In the U.S., about 11% of caregivers are veterans, but the availability of data about these caregivers is limited to veteran subgroups.3 For example, a 2011 study reported that 20% of veterans aged ≥ 60 years are caregivers.17 However, this estimate included child care for unimpaired children, which is not commonly included in other caregiving estimates. In another study, 30% of middle-aged active-duty officers reported helping their parents with instrumental ADLs (IADLs).18 These data suggest a significant proportion of veterans may be caregivers; however, the estimates do not identify prevalence of caregiving among a population of VHA enrolled veterans.

Likewise, few studies discuss the burden veterans experience from caregiving. A study of the 2009/2010 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data found that female caregivers were more likely to report problems with sleep and mental health if they were veterans vs nonveterans.19 In a second study, caregiving veterans frequently reported physical (39%) and emotional (53%) strain, with emotional strain relating to depressive symptoms. The study of active-duty officers noted that worry was prevalent among military officers caregiving for parents from a distance.18 In contrast to the negative outcomes of caregiving, Monin and colleagues found that many veterans perceived caregiving as rewarding. Since caregiving may be a positive experience, veterans may benefit and be a potential resource for care to elderly and disabled citizens.17

Project Rationale and Goals

Social workers are the cornerstone of caregiver support at the George E. Wahlen VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) in Utah. They educate veterans and caregivers about VA resources to support caregivers of veterans. For those veterans who are caregiving for a nonveteran, the VASLCHCS social workers provide psychosocial support and help veterans connect to a local area agency on aging (AAA) for access to functional support. In practice, primary care clinic (PCC) providers have observed that directing a veteran to call the AAA does not usually result in a phone call. Therefore, an aim of this quality improvement (QI) project was to determine the most effective means of completing a successful AAA referral.

The VASLCHCS Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center collaborates with the Utah Aging and Disability Resource Connection (ADRC) to improve awareness of available resources for veterans. Building on this collaborative project, the authors created a formal referral process for veterans needing local AAA services. This QI project had 3 aims: (1) estimate the prevalence of caregiving among veterans in the VASLCHCS primary care clinic; (2) identify perceived caregiving difficulties and resource use difficulty in caregiving tasks; and (3) test different strategies to connect veterans with a referral to community resources through the AAA.

The authors hypothesized that a veteran would be more likely to connect with the AAA if contact was initiated by the AAA rather than the standard practice of asking the veteran to make the call. However, the authors also hypothesized that a veteran who took the time to make the call would be more likely to use AAA resources compared with veterans who were called by the AAA.

Methods

The VASLCHCS Research and Development Office reviewed this project and determined that it met the definition of QI. Therefore, it did not require IRB approval.

The study drew from a convenience sample of veterans who were waiting for appointments in the PCC and who were referred by their health care provider (HCP). To identify caregivers, veterans were asked: “People may provide regular care or assistance to a friend or family member who has a health problem, long-term illness, or disability. During the past month, did you provide any such care or assistance to a friend or family member?” Referrals from HCPs were included in all calculations except the prevalence estimate.

The authors interviewed veterans over a 3-month period in 2015. As of November 2014, the clinic was serving about 11,000 veterans, of which 6,589 lived in Salt Lake County. The clinic also serves veterans who live in other counties in Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Idaho, and Colorado.

Intervention and Partnering With Community Resources

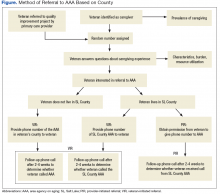

All willing caregivers were provided a referral to a local AAA (Figure). Salt Lake County veterans interested in referral to the AAA were randomized to 1 of 2 referral methods: veteran-initiated referral (VIR), in which the veteran was given a handout with the phone number of the Salt Lake County caregiver support program (CSP), or provider-initiated referral (PIR), in which the veteran’s phone number was given to the CSP. Caregiving veterans living outside Salt Lake County were provided the AAA phone number in their area and instructed to call for information.

The interview form was randomized using an even or odd number before the interview. Some veterans who were randomized to a PIR needed to be moved into the VIR intervention arm because of the following reasons: the veteran’s care recipient was aged < 18 years (3); the veteran lived outside of Salt Lake County (20); the veteran did not want his/her name given to an outside agency (5); or the interviewer mistakenly gave the veteran the AAA contact information (4).

The primary author called caregivers in the PIR and VIR groups 2 to 4 weeks after the referral to determine whether they had contacted or were contacted by the AAA. Ten call attempts were made before participants were considered lost to follow-up. Caregivers that had been in contact with the AAA reported in open-ended fashion the resources to which they had been referred and whether those resources had been helpful.

Analysis

In this evaluation, the primary outcome of interest was whether contact between the veteran and AAA occurred. For the VIR group, contact was defined as the veteran having called the AAA, regardless of whether he or she actually spoke to someone. For the PIR group, contact occurred if the veteran reported receiving a phone call from AAA regardless of whether he or she had actually spoken with someone (eg, if the veteran reported that the AAA had left a voice mail, this was considered contact). Veterans also were asked whether connecting with the AAA led to resource referrals and whether these referrals were useful.

To achieve a power of 80% with a 95% confidence interval, 20 people were needed in each intervention group to detect a 40% difference in the rate of contact between the 2 groups. STATA12 (College Station, TX) was used to calculate Fisher exact and chi-square values to evaluate differences between groups.

Results

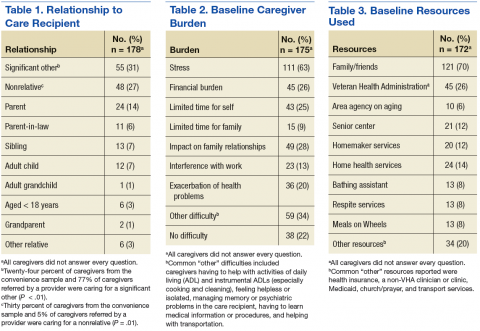

For the study, 433 PCC veterans were interviewed, and 157 (36%) self-identified as a caregiver. An additional 22 referrals were included for a total of 179 caregivers. Caregiver and care recipient characteristics, caregiver burden, and resource utilization were calculated for all 179 caregivers; however, all caregivers did not answer every question. Ninety-eight percent (176) of caregivers were men; 64% (109/170) were from Salt Lake County, and 5% were from outside Utah (8). Twelve percent (21) of the 179 caregivers were providing care for > 1 person. Of 177 caregivers, 3% (5) were caring for both a veteran and a nonveteran, 69% (122) were caring for a nonveteran only, and 28% (49) were caring for another veteran only (Table 1).

The most common burden reported by caregivers was stress (63%); 70% endorsed family/friends as a resource (Table 2). Just 6% (10) of caregivers used the AAA, whereas 26% (45) received VHA support. Of the 54 veterans who were caring for a veteran, 40 reported using the VHA as a resource. Five people caring for nonveterans reported using the VHA as a resource; however, data about which resources those caregivers were accessing were not collected (Table 3).

AAA Referral and Randomization

Sixty-five percent of caregivers accepted AAA referrals. Of 109 Salt Lake County caregivers, 70% accepted referral to the AAA. There was no statistically significant difference in referral acceptance rates when comparing Salt Lake County residents with nonresidents (P = .09).The authors were unable to obtain the phone number for 1 caregiver who had accepted a referral, and 1 caregiver who accepted referral did not want a follow-up. This left 111 caregivers available for follow-up, 75 in Salt Lake County. Fifty Salt Lake County veterans were randomly assigned to the VIR group and 25 to the PIR group. The 36 caregivers who accepted referrals outside Salt Lake County also were placed in the VIR group, for a total of 86 caregivers.

Follow-up

Ninety-eight percent of caregivers were reached for follow-up. Both people lost to follow-up were in Salt Lake County (1 in each group).

In Salt Lake County, 12% (6) of the VIR group and 64% (16) of the PIR group had connected with the AAA (P < .01). Although 64% of those in the PIR group reported having been called by the AAA, the AAA representative reported all 25 had been called. The AAA records showed 9 of those called were reached by voice mail, 6 were provided information about caregiving resources, 2 formally joined the support program, 5 declined help, 1 was no longer caregiving, 1 was too busy to talk, and 1 was the wrong phone number (and was lost to follow-up as well).

Outside of Salt Lake County 19% (7) reported calling the local AAA. There was no difference in referral completion between the Salt Lake County/non-Salt Lake County VIR groups (P = .4).

Fifteen percent of all VIR caregivers reported calling the AAA. There were no statistical differences between Salt Lake County VIR and non-Salt Lake County VIR for reasons why the veteran had not called the AAA (Table 4).

Of 28 people who connected with the AAA, 16 (57%) said they had received access to a needed resource as a result of the phone call. Seven caregivers (25%) said they had not been referred to other resources as a result of the call. The VIR group was more likely to be referred to other resources after contacting the AAA than was the PIR group, although this difference did not reach significance (69% vs 47%, P = .28).

Discussion

More than one-third (36%) of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. This prevalence is higher than that reported for the general U.S. population and higher than that reported in other veteran groups.5,17,18 Most caregivers in this project were caring for nonveterans and only had access to VHA psychosocial caregiver support programs because VHA functional caregiver support (eg, respite, homemaker services) is not available to veterans who care for nonveterans. A majority (78%) of caregiving veterans reported some caregiver burden. Despite the burden, most are not using community resources. However when offered, more than half the caregivers were interested in an AAA referral.

Although the VHA does not provide functional caregiver support resources to veterans caring for nonveterans, there are other agencies that can assist veterans: AAAs for care recipients aged ≥ 60 years and the ADRCs for younger veterans. Through AAAs, caregivers can access a variety of support services, including transportation, adult day care, caregiver support, and health promotion programs. Partnership between agencies such as the VHA and the AAAs could benefit caregiving veterans. This QI project suggests ways to strengthen interagency cooperation.

This study also suggests that a provider or clinic-initiated referral is more likely to connect veterans with information and resources than the current practice of recommending that the veteran initiate the referral. Once in contact with the AAA, most caregivers were referred to needed resources. The next step will be to establish an efficient way for clinic staff to identify caregiving veterans and make referrals to community programs. Referrals could be made by any member of the patient aligned care team (PACT) to further standardize and streamline the process.

Thirty-one percent of veterans in this project were eligible for the VHA caregiver support program because they cared for a veteran. However, 25% of these caregiving veterans were not accessing this resource. Increasing awareness of the VHA caregiver support program among veterans caring for other veterans would improve caregiver support to both caregiving and care recipient veterans.

Limitations

One limitation of this project was the intentional exclusion of the women’s clinic from the sampling process. For consistency, the authors wanted to limit the intervention to 1 PCC and so they chose the clinic that serves the majority of the veterans who receive primary care at VASLCHCS. Additionally, the literature showed that male caregivers compared with women caregivers20,21 have different characteristics in regards to caregiver burden, and a well-designed study of women caregivers already has been published.19

Also, this study did not obtain data on age, health problems, or socioeconomic status of the caregivers to avoid identifying information. Last, the authors did not ask about time spent caregiving or type of care provided. These questions may be important for future studies. Future investigations should evaluate health care use and health of caregivers vs noncaregivers in the veteran population. It also could be important to determine methods for building bridges between the VHA, AAAs, and other community services.

Conclusion

To minimize the disruption that a research study might have caused to normal clinical workflow, the primary author played the role that a medical social worker or other PACT member might play in the future. This project sheds light on how to improve outcomes for community referrals and an important future step in this research would be to develop and test a process that would integrate the PACT into the referral process.

More than one-third of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first estimate of prevalence of caregiving in veterans who receive primary care from the VHA. About 63% of caregiving veterans perceived some burden due to caregiving, and 66% accepted referral to community resources. However, only 12% who were asked to self-refer made contact with the AAA compared with 64% when a provider made the referral for them. Provider referral is more effective in connecting caregiving veterans with resources. Development of interagency partnerships should be fostered to help veterans decrease caregiving burden.

This project is one of the few studies looking at this special group of caregivers: veterans who serve as caregivers. It highlights the need for the VHA to establish policies and partnerships to improve caregiver support to this valuable group of veterans.

1. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States: population estimates and projections. http://www.census .gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

2. Smith AK, Walter LC, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE. Disability during the last two years of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1506-1513.

3. National Alliance for Caregiving, American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009 executive summary. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/caregiving_09_es.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 9, 2017.

4. Spillman BC, Wolff J, Freedman VA, Kasper JD; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Informal caregiving for older Americans: an analysis of the 2011 national study of caregiving. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/informal-caregiving-older-americans-analysis-2011-national-study-caregiving. Published April 1, 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

5. Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R; AARP Public Policy Institute. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update. The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. https://assets.aarp .org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed March 9, 2017.

6. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052-1059.

7. Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26(2):162-169.

8. Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):224-228.

9. Hoffman GJ, Lee J, Mendez-Luck CA. Health behaviors among baby boomer informal caregivers. Gerontologist. 2012;52(2):219-230.

10. National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregivers of veterans—serving on the homefront: report of study findings. http://www.caregiving.org/data/2010 _Caregivers_of_Veterans_FULLREPORT_WEB_FINAL.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

11. Johannesen M, LoGuidice D. Elder abuse: a systematic review of risk factors in community dwelling elders. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):292-298.

12. Goy E, Kansagara D, Freeman M;Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service. A systematic evidence review of interventions for non-professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. http://www.hsrd.research .va.gov/publications/esp/DementiaCaregivers-EXEC .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

13. Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al; Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) II Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727-738.

14. Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, Graney MJ, Zuber J. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system—REACH VA. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):353-359.

15. Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377-1386.

16. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. VA caregiver support: caregiver services. http://www.caregiver .va.gov/support/support_services.asp. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed March 9, 2017.

17. Monin JK, Levy BR, Pietrzak RH. From serving in the military to serving loved ones: unique experiences of older veteran caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):570-579.

18. Parker MW, Call VR, Dunkle R, Vaitkus M. “Out of sight” but not “out of mind”: parent contact and worry among senior ranking male officers in the military who live long distances from parents. Milit Psychol. 2002;14(4):257-277.

19. Lavela SL, Etingen B, Louise-Bender Pape T. Caregiving experiences and health conditions of women veteran and non-veteran caregivers. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(4):e225-e232.

20. Yee JL, Schultz RS. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147-164.

21. Collins CR. Men as caregivers of the elderly: support for the contributions of sons. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:525-531.

More than 20% of the U.S. population will be aged ≥ 65 years by 2030, an increase from 13% in 2012.1 The likelihood of needing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) increases with age.2 People who need such assistance often depend on informal and unpaid assistance from friends and family. In 2009, about 65.7 million Americans (28.5%) provided informal care for people with an illness or disability, and that number only is expected to rise.3 These informal caregivers provide up to 80% of the total care hours needed by community-dwelling older adults—an estimated economic value of $450 billion in unpaid contributions in 2009.4,5

Caregiving can lead to significant physical, psychological, social, and financial burdens.6 The caregiving burden is associated with a host of adverse health behaviors and outcomes such as poor diet, lack of exercise and sleep, smoking, decreased participation in preventive health care, anxiety, depression, relationship difficulties, employment disruption, financial hardship, suicide, and higher mortality compared with that of noncaregivers.6-10 Additionally, care recipients are at increased risk for abuse or neglect when the caregiver is experiencing a significant burden.11 Therefore, efforts to improve caregiver support are important for both partners in the caregiver/care recipient dyad.

Caregiver support is beneficial to the health of caregivers and care recipients.10,12 For example, the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) program has been shown to reduce the stress of informal caregiving and the risk of depression in caregivers.13,14 This program showed similar effects when implemented within the VHA.14 In the Partners in Dementia Care project, the VHA and Alzheimer’s Association coordinated care and support for veterans with dementia and their family and friends. This intervention resulted in lower caregiver strain and depression scores among participants.15

With a growing medical literature that shows the benefits of caregiver support interventions, the VHA developed a robust support program for informal caregivers of veterans. The VA caregiver support website (www.caregiver.va.gov) provides information and resources targeted to caregivers for veterans, including psychosocial and functional support for caregivers. The psychosocial support provided by the VA includes caregiver education, counseling, access to caregiver support coordinators, a caregiver support line, support groups, and referral to community support organizations.16 Functional support on the site includes financial assistance toward skilled home care, home hospice care, adult day care, home-based primary care, homemaker and home health aide services, telehealth, and respite care.16 Veterans who are caregiving for nonveterans have access to VHA psychosocial support but not to functional support services. For these veterans, functional caregiver support must come from family or referral to community organizations.

Background

In the U.S., about 11% of caregivers are veterans, but the availability of data about these caregivers is limited to veteran subgroups.3 For example, a 2011 study reported that 20% of veterans aged ≥ 60 years are caregivers.17 However, this estimate included child care for unimpaired children, which is not commonly included in other caregiving estimates. In another study, 30% of middle-aged active-duty officers reported helping their parents with instrumental ADLs (IADLs).18 These data suggest a significant proportion of veterans may be caregivers; however, the estimates do not identify prevalence of caregiving among a population of VHA enrolled veterans.

Likewise, few studies discuss the burden veterans experience from caregiving. A study of the 2009/2010 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data found that female caregivers were more likely to report problems with sleep and mental health if they were veterans vs nonveterans.19 In a second study, caregiving veterans frequently reported physical (39%) and emotional (53%) strain, with emotional strain relating to depressive symptoms. The study of active-duty officers noted that worry was prevalent among military officers caregiving for parents from a distance.18 In contrast to the negative outcomes of caregiving, Monin and colleagues found that many veterans perceived caregiving as rewarding. Since caregiving may be a positive experience, veterans may benefit and be a potential resource for care to elderly and disabled citizens.17

Project Rationale and Goals

Social workers are the cornerstone of caregiver support at the George E. Wahlen VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) in Utah. They educate veterans and caregivers about VA resources to support caregivers of veterans. For those veterans who are caregiving for a nonveteran, the VASLCHCS social workers provide psychosocial support and help veterans connect to a local area agency on aging (AAA) for access to functional support. In practice, primary care clinic (PCC) providers have observed that directing a veteran to call the AAA does not usually result in a phone call. Therefore, an aim of this quality improvement (QI) project was to determine the most effective means of completing a successful AAA referral.

The VASLCHCS Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center collaborates with the Utah Aging and Disability Resource Connection (ADRC) to improve awareness of available resources for veterans. Building on this collaborative project, the authors created a formal referral process for veterans needing local AAA services. This QI project had 3 aims: (1) estimate the prevalence of caregiving among veterans in the VASLCHCS primary care clinic; (2) identify perceived caregiving difficulties and resource use difficulty in caregiving tasks; and (3) test different strategies to connect veterans with a referral to community resources through the AAA.

The authors hypothesized that a veteran would be more likely to connect with the AAA if contact was initiated by the AAA rather than the standard practice of asking the veteran to make the call. However, the authors also hypothesized that a veteran who took the time to make the call would be more likely to use AAA resources compared with veterans who were called by the AAA.

Methods

The VASLCHCS Research and Development Office reviewed this project and determined that it met the definition of QI. Therefore, it did not require IRB approval.

The study drew from a convenience sample of veterans who were waiting for appointments in the PCC and who were referred by their health care provider (HCP). To identify caregivers, veterans were asked: “People may provide regular care or assistance to a friend or family member who has a health problem, long-term illness, or disability. During the past month, did you provide any such care or assistance to a friend or family member?” Referrals from HCPs were included in all calculations except the prevalence estimate.

The authors interviewed veterans over a 3-month period in 2015. As of November 2014, the clinic was serving about 11,000 veterans, of which 6,589 lived in Salt Lake County. The clinic also serves veterans who live in other counties in Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Idaho, and Colorado.

Intervention and Partnering With Community Resources

All willing caregivers were provided a referral to a local AAA (Figure). Salt Lake County veterans interested in referral to the AAA were randomized to 1 of 2 referral methods: veteran-initiated referral (VIR), in which the veteran was given a handout with the phone number of the Salt Lake County caregiver support program (CSP), or provider-initiated referral (PIR), in which the veteran’s phone number was given to the CSP. Caregiving veterans living outside Salt Lake County were provided the AAA phone number in their area and instructed to call for information.

The interview form was randomized using an even or odd number before the interview. Some veterans who were randomized to a PIR needed to be moved into the VIR intervention arm because of the following reasons: the veteran’s care recipient was aged < 18 years (3); the veteran lived outside of Salt Lake County (20); the veteran did not want his/her name given to an outside agency (5); or the interviewer mistakenly gave the veteran the AAA contact information (4).

The primary author called caregivers in the PIR and VIR groups 2 to 4 weeks after the referral to determine whether they had contacted or were contacted by the AAA. Ten call attempts were made before participants were considered lost to follow-up. Caregivers that had been in contact with the AAA reported in open-ended fashion the resources to which they had been referred and whether those resources had been helpful.

Analysis

In this evaluation, the primary outcome of interest was whether contact between the veteran and AAA occurred. For the VIR group, contact was defined as the veteran having called the AAA, regardless of whether he or she actually spoke to someone. For the PIR group, contact occurred if the veteran reported receiving a phone call from AAA regardless of whether he or she had actually spoken with someone (eg, if the veteran reported that the AAA had left a voice mail, this was considered contact). Veterans also were asked whether connecting with the AAA led to resource referrals and whether these referrals were useful.

To achieve a power of 80% with a 95% confidence interval, 20 people were needed in each intervention group to detect a 40% difference in the rate of contact between the 2 groups. STATA12 (College Station, TX) was used to calculate Fisher exact and chi-square values to evaluate differences between groups.

Results

For the study, 433 PCC veterans were interviewed, and 157 (36%) self-identified as a caregiver. An additional 22 referrals were included for a total of 179 caregivers. Caregiver and care recipient characteristics, caregiver burden, and resource utilization were calculated for all 179 caregivers; however, all caregivers did not answer every question. Ninety-eight percent (176) of caregivers were men; 64% (109/170) were from Salt Lake County, and 5% were from outside Utah (8). Twelve percent (21) of the 179 caregivers were providing care for > 1 person. Of 177 caregivers, 3% (5) were caring for both a veteran and a nonveteran, 69% (122) were caring for a nonveteran only, and 28% (49) were caring for another veteran only (Table 1).

The most common burden reported by caregivers was stress (63%); 70% endorsed family/friends as a resource (Table 2). Just 6% (10) of caregivers used the AAA, whereas 26% (45) received VHA support. Of the 54 veterans who were caring for a veteran, 40 reported using the VHA as a resource. Five people caring for nonveterans reported using the VHA as a resource; however, data about which resources those caregivers were accessing were not collected (Table 3).

AAA Referral and Randomization

Sixty-five percent of caregivers accepted AAA referrals. Of 109 Salt Lake County caregivers, 70% accepted referral to the AAA. There was no statistically significant difference in referral acceptance rates when comparing Salt Lake County residents with nonresidents (P = .09).The authors were unable to obtain the phone number for 1 caregiver who had accepted a referral, and 1 caregiver who accepted referral did not want a follow-up. This left 111 caregivers available for follow-up, 75 in Salt Lake County. Fifty Salt Lake County veterans were randomly assigned to the VIR group and 25 to the PIR group. The 36 caregivers who accepted referrals outside Salt Lake County also were placed in the VIR group, for a total of 86 caregivers.

Follow-up

Ninety-eight percent of caregivers were reached for follow-up. Both people lost to follow-up were in Salt Lake County (1 in each group).

In Salt Lake County, 12% (6) of the VIR group and 64% (16) of the PIR group had connected with the AAA (P < .01). Although 64% of those in the PIR group reported having been called by the AAA, the AAA representative reported all 25 had been called. The AAA records showed 9 of those called were reached by voice mail, 6 were provided information about caregiving resources, 2 formally joined the support program, 5 declined help, 1 was no longer caregiving, 1 was too busy to talk, and 1 was the wrong phone number (and was lost to follow-up as well).

Outside of Salt Lake County 19% (7) reported calling the local AAA. There was no difference in referral completion between the Salt Lake County/non-Salt Lake County VIR groups (P = .4).

Fifteen percent of all VIR caregivers reported calling the AAA. There were no statistical differences between Salt Lake County VIR and non-Salt Lake County VIR for reasons why the veteran had not called the AAA (Table 4).

Of 28 people who connected with the AAA, 16 (57%) said they had received access to a needed resource as a result of the phone call. Seven caregivers (25%) said they had not been referred to other resources as a result of the call. The VIR group was more likely to be referred to other resources after contacting the AAA than was the PIR group, although this difference did not reach significance (69% vs 47%, P = .28).

Discussion

More than one-third (36%) of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. This prevalence is higher than that reported for the general U.S. population and higher than that reported in other veteran groups.5,17,18 Most caregivers in this project were caring for nonveterans and only had access to VHA psychosocial caregiver support programs because VHA functional caregiver support (eg, respite, homemaker services) is not available to veterans who care for nonveterans. A majority (78%) of caregiving veterans reported some caregiver burden. Despite the burden, most are not using community resources. However when offered, more than half the caregivers were interested in an AAA referral.

Although the VHA does not provide functional caregiver support resources to veterans caring for nonveterans, there are other agencies that can assist veterans: AAAs for care recipients aged ≥ 60 years and the ADRCs for younger veterans. Through AAAs, caregivers can access a variety of support services, including transportation, adult day care, caregiver support, and health promotion programs. Partnership between agencies such as the VHA and the AAAs could benefit caregiving veterans. This QI project suggests ways to strengthen interagency cooperation.

This study also suggests that a provider or clinic-initiated referral is more likely to connect veterans with information and resources than the current practice of recommending that the veteran initiate the referral. Once in contact with the AAA, most caregivers were referred to needed resources. The next step will be to establish an efficient way for clinic staff to identify caregiving veterans and make referrals to community programs. Referrals could be made by any member of the patient aligned care team (PACT) to further standardize and streamline the process.

Thirty-one percent of veterans in this project were eligible for the VHA caregiver support program because they cared for a veteran. However, 25% of these caregiving veterans were not accessing this resource. Increasing awareness of the VHA caregiver support program among veterans caring for other veterans would improve caregiver support to both caregiving and care recipient veterans.

Limitations

One limitation of this project was the intentional exclusion of the women’s clinic from the sampling process. For consistency, the authors wanted to limit the intervention to 1 PCC and so they chose the clinic that serves the majority of the veterans who receive primary care at VASLCHCS. Additionally, the literature showed that male caregivers compared with women caregivers20,21 have different characteristics in regards to caregiver burden, and a well-designed study of women caregivers already has been published.19

Also, this study did not obtain data on age, health problems, or socioeconomic status of the caregivers to avoid identifying information. Last, the authors did not ask about time spent caregiving or type of care provided. These questions may be important for future studies. Future investigations should evaluate health care use and health of caregivers vs noncaregivers in the veteran population. It also could be important to determine methods for building bridges between the VHA, AAAs, and other community services.

Conclusion

To minimize the disruption that a research study might have caused to normal clinical workflow, the primary author played the role that a medical social worker or other PACT member might play in the future. This project sheds light on how to improve outcomes for community referrals and an important future step in this research would be to develop and test a process that would integrate the PACT into the referral process.

More than one-third of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first estimate of prevalence of caregiving in veterans who receive primary care from the VHA. About 63% of caregiving veterans perceived some burden due to caregiving, and 66% accepted referral to community resources. However, only 12% who were asked to self-refer made contact with the AAA compared with 64% when a provider made the referral for them. Provider referral is more effective in connecting caregiving veterans with resources. Development of interagency partnerships should be fostered to help veterans decrease caregiving burden.

This project is one of the few studies looking at this special group of caregivers: veterans who serve as caregivers. It highlights the need for the VHA to establish policies and partnerships to improve caregiver support to this valuable group of veterans.

More than 20% of the U.S. population will be aged ≥ 65 years by 2030, an increase from 13% in 2012.1 The likelihood of needing assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs) increases with age.2 People who need such assistance often depend on informal and unpaid assistance from friends and family. In 2009, about 65.7 million Americans (28.5%) provided informal care for people with an illness or disability, and that number only is expected to rise.3 These informal caregivers provide up to 80% of the total care hours needed by community-dwelling older adults—an estimated economic value of $450 billion in unpaid contributions in 2009.4,5

Caregiving can lead to significant physical, psychological, social, and financial burdens.6 The caregiving burden is associated with a host of adverse health behaviors and outcomes such as poor diet, lack of exercise and sleep, smoking, decreased participation in preventive health care, anxiety, depression, relationship difficulties, employment disruption, financial hardship, suicide, and higher mortality compared with that of noncaregivers.6-10 Additionally, care recipients are at increased risk for abuse or neglect when the caregiver is experiencing a significant burden.11 Therefore, efforts to improve caregiver support are important for both partners in the caregiver/care recipient dyad.

Caregiver support is beneficial to the health of caregivers and care recipients.10,12 For example, the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) program has been shown to reduce the stress of informal caregiving and the risk of depression in caregivers.13,14 This program showed similar effects when implemented within the VHA.14 In the Partners in Dementia Care project, the VHA and Alzheimer’s Association coordinated care and support for veterans with dementia and their family and friends. This intervention resulted in lower caregiver strain and depression scores among participants.15

With a growing medical literature that shows the benefits of caregiver support interventions, the VHA developed a robust support program for informal caregivers of veterans. The VA caregiver support website (www.caregiver.va.gov) provides information and resources targeted to caregivers for veterans, including psychosocial and functional support for caregivers. The psychosocial support provided by the VA includes caregiver education, counseling, access to caregiver support coordinators, a caregiver support line, support groups, and referral to community support organizations.16 Functional support on the site includes financial assistance toward skilled home care, home hospice care, adult day care, home-based primary care, homemaker and home health aide services, telehealth, and respite care.16 Veterans who are caregiving for nonveterans have access to VHA psychosocial support but not to functional support services. For these veterans, functional caregiver support must come from family or referral to community organizations.

Background

In the U.S., about 11% of caregivers are veterans, but the availability of data about these caregivers is limited to veteran subgroups.3 For example, a 2011 study reported that 20% of veterans aged ≥ 60 years are caregivers.17 However, this estimate included child care for unimpaired children, which is not commonly included in other caregiving estimates. In another study, 30% of middle-aged active-duty officers reported helping their parents with instrumental ADLs (IADLs).18 These data suggest a significant proportion of veterans may be caregivers; however, the estimates do not identify prevalence of caregiving among a population of VHA enrolled veterans.

Likewise, few studies discuss the burden veterans experience from caregiving. A study of the 2009/2010 CDC Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System data found that female caregivers were more likely to report problems with sleep and mental health if they were veterans vs nonveterans.19 In a second study, caregiving veterans frequently reported physical (39%) and emotional (53%) strain, with emotional strain relating to depressive symptoms. The study of active-duty officers noted that worry was prevalent among military officers caregiving for parents from a distance.18 In contrast to the negative outcomes of caregiving, Monin and colleagues found that many veterans perceived caregiving as rewarding. Since caregiving may be a positive experience, veterans may benefit and be a potential resource for care to elderly and disabled citizens.17

Project Rationale and Goals

Social workers are the cornerstone of caregiver support at the George E. Wahlen VA Salt Lake City Health Care System (VASLCHCS) in Utah. They educate veterans and caregivers about VA resources to support caregivers of veterans. For those veterans who are caregiving for a nonveteran, the VASLCHCS social workers provide psychosocial support and help veterans connect to a local area agency on aging (AAA) for access to functional support. In practice, primary care clinic (PCC) providers have observed that directing a veteran to call the AAA does not usually result in a phone call. Therefore, an aim of this quality improvement (QI) project was to determine the most effective means of completing a successful AAA referral.

The VASLCHCS Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center collaborates with the Utah Aging and Disability Resource Connection (ADRC) to improve awareness of available resources for veterans. Building on this collaborative project, the authors created a formal referral process for veterans needing local AAA services. This QI project had 3 aims: (1) estimate the prevalence of caregiving among veterans in the VASLCHCS primary care clinic; (2) identify perceived caregiving difficulties and resource use difficulty in caregiving tasks; and (3) test different strategies to connect veterans with a referral to community resources through the AAA.

The authors hypothesized that a veteran would be more likely to connect with the AAA if contact was initiated by the AAA rather than the standard practice of asking the veteran to make the call. However, the authors also hypothesized that a veteran who took the time to make the call would be more likely to use AAA resources compared with veterans who were called by the AAA.

Methods

The VASLCHCS Research and Development Office reviewed this project and determined that it met the definition of QI. Therefore, it did not require IRB approval.

The study drew from a convenience sample of veterans who were waiting for appointments in the PCC and who were referred by their health care provider (HCP). To identify caregivers, veterans were asked: “People may provide regular care or assistance to a friend or family member who has a health problem, long-term illness, or disability. During the past month, did you provide any such care or assistance to a friend or family member?” Referrals from HCPs were included in all calculations except the prevalence estimate.

The authors interviewed veterans over a 3-month period in 2015. As of November 2014, the clinic was serving about 11,000 veterans, of which 6,589 lived in Salt Lake County. The clinic also serves veterans who live in other counties in Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Idaho, and Colorado.

Intervention and Partnering With Community Resources

All willing caregivers were provided a referral to a local AAA (Figure). Salt Lake County veterans interested in referral to the AAA were randomized to 1 of 2 referral methods: veteran-initiated referral (VIR), in which the veteran was given a handout with the phone number of the Salt Lake County caregiver support program (CSP), or provider-initiated referral (PIR), in which the veteran’s phone number was given to the CSP. Caregiving veterans living outside Salt Lake County were provided the AAA phone number in their area and instructed to call for information.

The interview form was randomized using an even or odd number before the interview. Some veterans who were randomized to a PIR needed to be moved into the VIR intervention arm because of the following reasons: the veteran’s care recipient was aged < 18 years (3); the veteran lived outside of Salt Lake County (20); the veteran did not want his/her name given to an outside agency (5); or the interviewer mistakenly gave the veteran the AAA contact information (4).

The primary author called caregivers in the PIR and VIR groups 2 to 4 weeks after the referral to determine whether they had contacted or were contacted by the AAA. Ten call attempts were made before participants were considered lost to follow-up. Caregivers that had been in contact with the AAA reported in open-ended fashion the resources to which they had been referred and whether those resources had been helpful.

Analysis

In this evaluation, the primary outcome of interest was whether contact between the veteran and AAA occurred. For the VIR group, contact was defined as the veteran having called the AAA, regardless of whether he or she actually spoke to someone. For the PIR group, contact occurred if the veteran reported receiving a phone call from AAA regardless of whether he or she had actually spoken with someone (eg, if the veteran reported that the AAA had left a voice mail, this was considered contact). Veterans also were asked whether connecting with the AAA led to resource referrals and whether these referrals were useful.

To achieve a power of 80% with a 95% confidence interval, 20 people were needed in each intervention group to detect a 40% difference in the rate of contact between the 2 groups. STATA12 (College Station, TX) was used to calculate Fisher exact and chi-square values to evaluate differences between groups.

Results

For the study, 433 PCC veterans were interviewed, and 157 (36%) self-identified as a caregiver. An additional 22 referrals were included for a total of 179 caregivers. Caregiver and care recipient characteristics, caregiver burden, and resource utilization were calculated for all 179 caregivers; however, all caregivers did not answer every question. Ninety-eight percent (176) of caregivers were men; 64% (109/170) were from Salt Lake County, and 5% were from outside Utah (8). Twelve percent (21) of the 179 caregivers were providing care for > 1 person. Of 177 caregivers, 3% (5) were caring for both a veteran and a nonveteran, 69% (122) were caring for a nonveteran only, and 28% (49) were caring for another veteran only (Table 1).

The most common burden reported by caregivers was stress (63%); 70% endorsed family/friends as a resource (Table 2). Just 6% (10) of caregivers used the AAA, whereas 26% (45) received VHA support. Of the 54 veterans who were caring for a veteran, 40 reported using the VHA as a resource. Five people caring for nonveterans reported using the VHA as a resource; however, data about which resources those caregivers were accessing were not collected (Table 3).

AAA Referral and Randomization

Sixty-five percent of caregivers accepted AAA referrals. Of 109 Salt Lake County caregivers, 70% accepted referral to the AAA. There was no statistically significant difference in referral acceptance rates when comparing Salt Lake County residents with nonresidents (P = .09).The authors were unable to obtain the phone number for 1 caregiver who had accepted a referral, and 1 caregiver who accepted referral did not want a follow-up. This left 111 caregivers available for follow-up, 75 in Salt Lake County. Fifty Salt Lake County veterans were randomly assigned to the VIR group and 25 to the PIR group. The 36 caregivers who accepted referrals outside Salt Lake County also were placed in the VIR group, for a total of 86 caregivers.

Follow-up

Ninety-eight percent of caregivers were reached for follow-up. Both people lost to follow-up were in Salt Lake County (1 in each group).

In Salt Lake County, 12% (6) of the VIR group and 64% (16) of the PIR group had connected with the AAA (P < .01). Although 64% of those in the PIR group reported having been called by the AAA, the AAA representative reported all 25 had been called. The AAA records showed 9 of those called were reached by voice mail, 6 were provided information about caregiving resources, 2 formally joined the support program, 5 declined help, 1 was no longer caregiving, 1 was too busy to talk, and 1 was the wrong phone number (and was lost to follow-up as well).

Outside of Salt Lake County 19% (7) reported calling the local AAA. There was no difference in referral completion between the Salt Lake County/non-Salt Lake County VIR groups (P = .4).

Fifteen percent of all VIR caregivers reported calling the AAA. There were no statistical differences between Salt Lake County VIR and non-Salt Lake County VIR for reasons why the veteran had not called the AAA (Table 4).

Of 28 people who connected with the AAA, 16 (57%) said they had received access to a needed resource as a result of the phone call. Seven caregivers (25%) said they had not been referred to other resources as a result of the call. The VIR group was more likely to be referred to other resources after contacting the AAA than was the PIR group, although this difference did not reach significance (69% vs 47%, P = .28).

Discussion

More than one-third (36%) of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. This prevalence is higher than that reported for the general U.S. population and higher than that reported in other veteran groups.5,17,18 Most caregivers in this project were caring for nonveterans and only had access to VHA psychosocial caregiver support programs because VHA functional caregiver support (eg, respite, homemaker services) is not available to veterans who care for nonveterans. A majority (78%) of caregiving veterans reported some caregiver burden. Despite the burden, most are not using community resources. However when offered, more than half the caregivers were interested in an AAA referral.

Although the VHA does not provide functional caregiver support resources to veterans caring for nonveterans, there are other agencies that can assist veterans: AAAs for care recipients aged ≥ 60 years and the ADRCs for younger veterans. Through AAAs, caregivers can access a variety of support services, including transportation, adult day care, caregiver support, and health promotion programs. Partnership between agencies such as the VHA and the AAAs could benefit caregiving veterans. This QI project suggests ways to strengthen interagency cooperation.

This study also suggests that a provider or clinic-initiated referral is more likely to connect veterans with information and resources than the current practice of recommending that the veteran initiate the referral. Once in contact with the AAA, most caregivers were referred to needed resources. The next step will be to establish an efficient way for clinic staff to identify caregiving veterans and make referrals to community programs. Referrals could be made by any member of the patient aligned care team (PACT) to further standardize and streamline the process.

Thirty-one percent of veterans in this project were eligible for the VHA caregiver support program because they cared for a veteran. However, 25% of these caregiving veterans were not accessing this resource. Increasing awareness of the VHA caregiver support program among veterans caring for other veterans would improve caregiver support to both caregiving and care recipient veterans.

Limitations

One limitation of this project was the intentional exclusion of the women’s clinic from the sampling process. For consistency, the authors wanted to limit the intervention to 1 PCC and so they chose the clinic that serves the majority of the veterans who receive primary care at VASLCHCS. Additionally, the literature showed that male caregivers compared with women caregivers20,21 have different characteristics in regards to caregiver burden, and a well-designed study of women caregivers already has been published.19

Also, this study did not obtain data on age, health problems, or socioeconomic status of the caregivers to avoid identifying information. Last, the authors did not ask about time spent caregiving or type of care provided. These questions may be important for future studies. Future investigations should evaluate health care use and health of caregivers vs noncaregivers in the veteran population. It also could be important to determine methods for building bridges between the VHA, AAAs, and other community services.

Conclusion

To minimize the disruption that a research study might have caused to normal clinical workflow, the primary author played the role that a medical social worker or other PACT member might play in the future. This project sheds light on how to improve outcomes for community referrals and an important future step in this research would be to develop and test a process that would integrate the PACT into the referral process.

More than one-third of veterans seen in the VASLCHCS PCC are caregivers. To the authors’ knowledge, this is the first estimate of prevalence of caregiving in veterans who receive primary care from the VHA. About 63% of caregiving veterans perceived some burden due to caregiving, and 66% accepted referral to community resources. However, only 12% who were asked to self-refer made contact with the AAA compared with 64% when a provider made the referral for them. Provider referral is more effective in connecting caregiving veterans with resources. Development of interagency partnerships should be fostered to help veterans decrease caregiving burden.

This project is one of the few studies looking at this special group of caregivers: veterans who serve as caregivers. It highlights the need for the VHA to establish policies and partnerships to improve caregiver support to this valuable group of veterans.

1. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States: population estimates and projections. http://www.census .gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

2. Smith AK, Walter LC, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE. Disability during the last two years of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1506-1513.

3. National Alliance for Caregiving, American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009 executive summary. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/caregiving_09_es.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 9, 2017.

4. Spillman BC, Wolff J, Freedman VA, Kasper JD; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Informal caregiving for older Americans: an analysis of the 2011 national study of caregiving. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/informal-caregiving-older-americans-analysis-2011-national-study-caregiving. Published April 1, 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

5. Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R; AARP Public Policy Institute. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update. The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. https://assets.aarp .org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed March 9, 2017.

6. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052-1059.

7. Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26(2):162-169.

8. Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):224-228.

9. Hoffman GJ, Lee J, Mendez-Luck CA. Health behaviors among baby boomer informal caregivers. Gerontologist. 2012;52(2):219-230.

10. National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregivers of veterans—serving on the homefront: report of study findings. http://www.caregiving.org/data/2010 _Caregivers_of_Veterans_FULLREPORT_WEB_FINAL.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

11. Johannesen M, LoGuidice D. Elder abuse: a systematic review of risk factors in community dwelling elders. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):292-298.

12. Goy E, Kansagara D, Freeman M;Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service. A systematic evidence review of interventions for non-professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. http://www.hsrd.research .va.gov/publications/esp/DementiaCaregivers-EXEC .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

13. Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al; Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) II Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727-738.

14. Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, Graney MJ, Zuber J. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system—REACH VA. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):353-359.

15. Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377-1386.

16. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. VA caregiver support: caregiver services. http://www.caregiver .va.gov/support/support_services.asp. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed March 9, 2017.

17. Monin JK, Levy BR, Pietrzak RH. From serving in the military to serving loved ones: unique experiences of older veteran caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):570-579.

18. Parker MW, Call VR, Dunkle R, Vaitkus M. “Out of sight” but not “out of mind”: parent contact and worry among senior ranking male officers in the military who live long distances from parents. Milit Psychol. 2002;14(4):257-277.

19. Lavela SL, Etingen B, Louise-Bender Pape T. Caregiving experiences and health conditions of women veteran and non-veteran caregivers. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(4):e225-e232.

20. Yee JL, Schultz RS. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147-164.

21. Collins CR. Men as caregivers of the elderly: support for the contributions of sons. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:525-531.

1. Ortman JM, Velkoff VA, Hogan H. An aging nation: the older population in the United States: population estimates and projections. http://www.census .gov/prod/2014pubs/p25-1140.pdf. Published May 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

2. Smith AK, Walter LC, Miao Y, Boscardin WJ, Covinsky KE. Disability during the last two years of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(16):1506-1513.

3. National Alliance for Caregiving, American Association of Retired Persons. Caregiving in the U.S. 2009 executive summary. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/il/caregiving_09_es.pdf. Published November 2009. Accessed March 9, 2017.

4. Spillman BC, Wolff J, Freedman VA, Kasper JD; Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Informal caregiving for older Americans: an analysis of the 2011 national study of caregiving. https://aspe.hhs.gov/report/informal-caregiving-older-americans-analysis-2011-national-study-caregiving. Published April 1, 2014. Accessed March 9, 2017.

5. Feinberg L, Reinhard SC, Houser A, Choula R; AARP Public Policy Institute. Valuing the invaluable: 2011 update. The growing contributions and costs of family caregiving. https://assets.aarp .org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf. Published June 2011. Accessed March 9, 2017.

6. Adelman RD, Tmanova LL, Delgado D, Dion S, Lachs MS. Caregiver burden: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014;311(10):1052-1059.

7. Burton LC, Newsom JT, Schulz R, Hirsch CH, German PS. Preventive health behaviors among spousal caregivers. Prev Med. 1997;26(2):162-169.

8. Talley RC, Crews JE. Framing the public health of caregiving. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(2):224-228.

9. Hoffman GJ, Lee J, Mendez-Luck CA. Health behaviors among baby boomer informal caregivers. Gerontologist. 2012;52(2):219-230.

10. National Alliance for Caregiving. Caregivers of veterans—serving on the homefront: report of study findings. http://www.caregiving.org/data/2010 _Caregivers_of_Veterans_FULLREPORT_WEB_FINAL.pdf. Published November 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

11. Johannesen M, LoGuidice D. Elder abuse: a systematic review of risk factors in community dwelling elders. Age Ageing. 2013;42(3):292-298.

12. Goy E, Kansagara D, Freeman M;Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service. A systematic evidence review of interventions for non-professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. http://www.hsrd.research .va.gov/publications/esp/DementiaCaregivers-EXEC .pdf. Published October 2010. Accessed March 9, 2017.

13. Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al; Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) II Investigators. Enhancing the quality of life of dementia caregivers from different ethnic or racial groups: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):727-738.

14. Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Burns R, Graney MJ, Zuber J. Translation of a dementia caregiver support program in a health care system—REACH VA. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):353-359.

15. Bass DM, Judge KS, Snow AL, et al. Caregiver outcomes of partners in dementia care: effect of a care coordination program for veterans with dementia and their family members and friends. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(8):1377-1386.

16. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs. VA caregiver support: caregiver services. http://www.caregiver .va.gov/support/support_services.asp. Updated June 3, 2015. Accessed March 9, 2017.

17. Monin JK, Levy BR, Pietrzak RH. From serving in the military to serving loved ones: unique experiences of older veteran caregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2014;22(6):570-579.

18. Parker MW, Call VR, Dunkle R, Vaitkus M. “Out of sight” but not “out of mind”: parent contact and worry among senior ranking male officers in the military who live long distances from parents. Milit Psychol. 2002;14(4):257-277.

19. Lavela SL, Etingen B, Louise-Bender Pape T. Caregiving experiences and health conditions of women veteran and non-veteran caregivers. Womens Health Issues. 2013;23(4):e225-e232.

20. Yee JL, Schultz RS. Gender differences in psychiatric morbidity among family caregivers: a review and analysis. Gerontologist. 2000;40(2):147-164.

21. Collins CR. Men as caregivers of the elderly: support for the contributions of sons. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2014;7:525-531.