User login

Advanced-stage calciphylaxis: Think before you punch

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

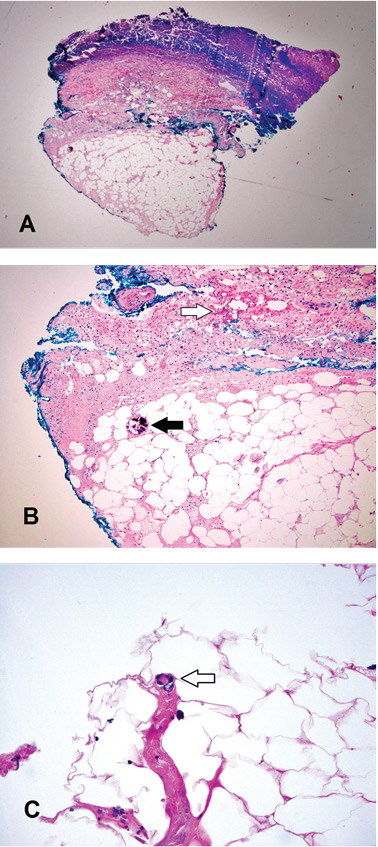

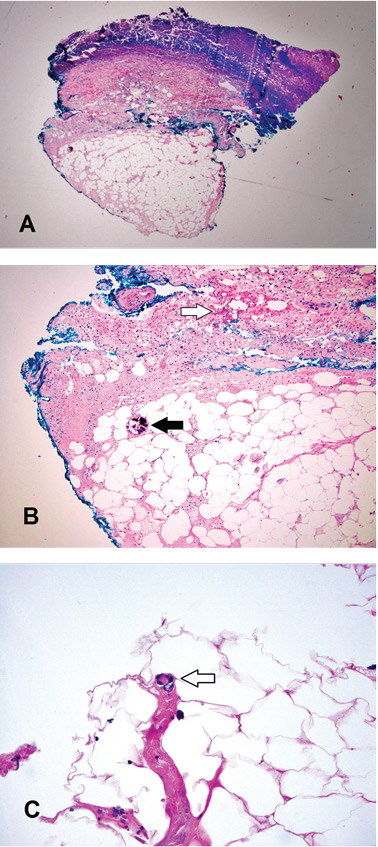

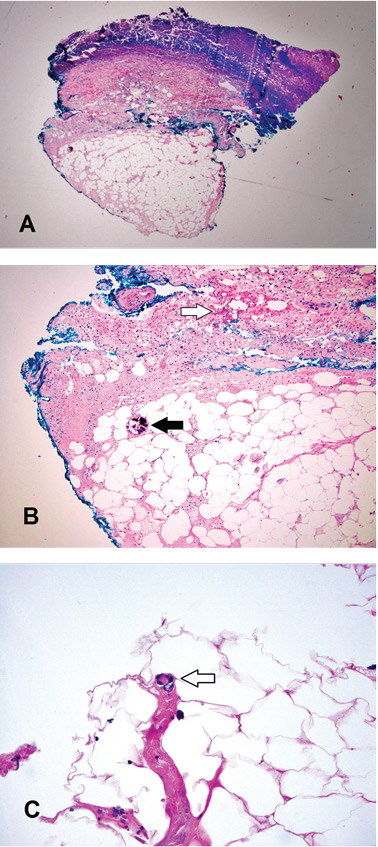

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

A 53-year-old woman presented with extensive, nonulcerated, painful plaques on both calves. She had long-standing diabetes mellitus and had recently started hemodialysis. She had no fever or trauma and did not appear to be in shock.

On physical examination, she had extensive, well-demarcated, nonulcerated, indurated dark eschar over the right calf (Figure 1). Her left calf had similar lesions that appeared as focal, discrete, nonulcerated, violaceous plaques, with associated tenderness. No significant erythema, edema, drainage, or fluctuance was noted.

A broad-spectrum antibiotic was started empirically but was discontinued when routine blood testing and magnetic resonance imaging showed no evidence of infection. Histologic study of a full-thickness skin biopsy specimen (Figure 2) showed tissue necrosis, ulceration, and concentric calcification of small and medium-sized blood vessels, many with luminal thrombi, all of which together were diagnostic for calciphylaxis.

Treatment was started with cinacalcet, low-calcium dialysis baths, phosphate binders, and sodium thiosulfate. However, within a few days of the biopsy procedure, an infection developed at the biopsy site, and the patient developed sepsis and septic shock. She received broad-spectrum antibiotics and underwent extensive debridement with wound care. After a protracted hospital course, the infection resolved.

CALCIPHYLAXIS RISK FACTORS

Calciphylaxis, also referred to as calcific uremic arteriolopathy, is a rare and often fatal condition in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis (1% to 4% of dialysis patients).1–3 It is also seen in patients who have undergone renal transplant and in patients with chronic kidney disease who have a chronic inflammatory disease or who have been exposed to corticosteroids or warfarin. However, it can also occur in patients without chronic kidney disease or end-stage renal disease.

The term “calcific uremic arteriolopathy” is a misnomer, as this condition can occur in patients with normal renal function (nonuremic calciphylaxis). Also, despite what the term calciphylaxis implies, there is no systemic anaphylaxis.3–5

Documented risk factors include obesity; female sex; use of warfarin, corticosteroids, or vitamin D analogues; low serum albumin; hypercoagulable states; hyperparathyroidism; alcoholic liver disease; elevated calcium-phosphorus product; inflammation; connective tissue disease; and cancer.4–6

DIAGNOSTIC CLUES

There are no strict guidelines for the diagnosis of calciphylaxis, and the exact pathophysiology of calciphylaxis is not understood.1–4

Ulceration is considered the clinical hallmark, but there are increasing reports of patients presenting with nonulcerated plaques, as in our patient. The literature suggests a mortality rate of 33% at 6 months in these patients, but ulceration increases the risk of death to over 80%, and sepsis is the leading cause of death.7,8

Histologic features identified on full-thickness biopsy specimens are intravascular deposition of calcium in the media of the blood vessels, as well as fibrin thrombi formation, intimal proliferation, tissue necrosis, and resultant ischemia. However, as in our patient and as discussed below, the biopsy procedure can induce or exacerbate ulceration, increasing the risk of sepsis, and is thus controversial.7

In the early stages, lesions of calciphylaxis are focal and appear as erythema or livedo reticularis with or without subcutaneous plaques or ulcers. As the disease progresses, the ischemic changes coalesce to form denser violaceous, painful, plaquelike subcutaneous nodules with eschar. In the advanced stages, the eschar or ulceration involves an extensive area.

Diagnosis in the early stages is challenging because of the focal nature of involvement. The differential diagnosis includes potentially fatal conditions such as systemic vasculitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, pyoderma gangrenosum, gangrene from peripheral arterial disease, cholesterol embolization, warfarin-induced necrosis, purpura fulminans, and oxalate vasculopathy.7

In the advanced stages, the diagnosis of calciphylaxis is clinically more evident, and the differential diagnosis usually narrows. Well-demarcated, necrotic, indurated lesions that are bilateral in a patient with end-stage renal disease without shock makes the diagnosis very likely.

The dangers of biopsy

As seen in our patient, biopsy for histologic confirmation of calciphylaxis can increase the risk of infection and sepsis.7 Also, the efficacy and clinical utility are uncertain because the quantity or depth of tissue obtained may not be enough for diagnosis. Deep incisional cutaneous biopsy is needed rather than punch biopsy to provide ample subcutaneous tissue for histologic study.3

Further, the biopsy procedure induces ulceration in the region of the incision, increasing the risk of infection and poor healing and escalating the risk of sepsis and death.7–9 Since extensive necrosis predisposes to a negative biopsy, a high clinical suspicion should drive early treatment of calciphylaxis.10 Noninvasive imaging studies such as plain radiography and bone scintigraphy can aid the diagnosis by detecting moderate to severe soft-tissue vascular calcification in these areas.7–11

DEBRIDEMENT IS CONTROVERSIAL

Conservative measures are the mainstay of care and include dietary alterations, noncalcium and nonaluminum phosphate binders, and low-calcium bath dialysis. There is mounting evidence for the use of calcimimetics and sodium thiosulfate.7,12–14

The role of wound debridement is controversial, as concomitant poor peripheral vascular perfusion can delay wound healing and, if ulceration ensues, there is a dramatic escalation of mortality risk. The decision for wound debridement is determined case by case, based on an assessment of the comorbidities, vascular perfusion, and status of the eschar.

Extensive wound debridement should be considered immediately after biopsy or with any signs of ulceration or infection—this in addition to meticulous wound care, which will promote healing and prevent serious complications secondary to infection.15

A TEAM APPROACH IMPROVES OUTCOMES

A multidisciplinary approach involving surgeons, nephrologists, dermatologists, dermatopathologists, wound or burn care team, nutrition team, pain management team, and infectious disease team is important to improve outcomes.7

Management mainly involves controlling pain; avoiding local trauma; treating and preventing infection; stopping causative agents such as warfarin and corticosteroids; intensive hemodialysis with an increase in both frequency and duration; intravenous sodium thiosulphate; non-calcium-phosphorus binders and cinacalcet in patients with elevated parathyroid hormone; and hyperbaric oxygen.12–14 There are also reports of success with oral etidronate and intravenous pamidronate.16,17

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

- Spanakis EK, Sellmeyer DE. Nonuremic calciphylaxis precipitated by teriparatide [rhPTH(1-34)] therapy in the setting of chronic warfarin and glucocorticoid treatment. Osteoporos Int 2014; 25:1411–1414.

- Brandenburg VM, Cozzolino M, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis: a still unmet challenge. J Nephrol 2011; 24:142–148.

- Wilmer WA, Magro CM. Calciphylaxis: emerging concepts in prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Semin Dial 2002; 15:172–186.

- Rimtepathip P, Cohen D. A rare presentation of calciphylaxis in normal renal function. Int J Case Rep Images 2015; 6:366–369.

- Lonowski S, Martin S, Worswick S. Widespread calciphylaxis and normal renal function: no improvement with sodium thiosulfate. Dermatol Online J 2015; 21:13030/qt76845802.

- Zhou Q, Neubauer J, Kern JS, Grotz W, Walz G, Huber TB. Calciphylaxis. Lancet 2014; 383:1067.

- Nigwekar SU, Kroshinsky D, Nazarian RM, et al. Calciphylaxis: risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 66:133–146.

- Fine A, Zacharias J. Calciphylaxis is usually non-ulcerating: risk factors, outcome and therapy. Kidney Int 2002; 61:2210–2217.

- Hayashi M. Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features. Clin Exp Nephrol 2013; 17:498–503.

- Stavros K, Motiwala R, Zhou L, Sejdiu F, Shin S. Calciphylaxis in a dialysis patient diagnosed by muscle biopsy. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2014; 15:108–111.

- Bonchak JG, Park KK, Vethanayagamony T, Sheikh MM, Winterfield LS. Calciphylaxis: a case series and the role of radiology in diagnosis. Int J Dermatol 2015. [Epub ahead of print]

- Ross EA. Evolution of treatment strategies for calciphylaxis. Am J Nephrol 2011; 34:460–467.

- Cicone JS, Petronis JB, Embert CD, Spector DA. Successful treatment of calciphylaxis with intravenous sodium thiosulfate. Am J Kidney Dis 2004; 43:1104–1108.

- Brandenburg VM, Kramann R, Specht P, Ketteler M. Calciphylaxis in CKD and beyond. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2012; 27:1314–1318.

- Martin R. Mysterious calciphylaxis: wounds with eschar—to debride or not to debride? Ostomy Wound Manage 2004; 50:64–66.

- Shiraishi N, Kitamura K, Miyoshi T, et al. Successful treatment of a patient with severe calcific uremic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis) by etidronate disodium. Am J Kidney Dis 2006; 48:151–154.

- Hanafusa T, Yamaguchi Y, Tani M, Umegaki N, Nishimura Y, Katayama I. Intractable wounds caused by calcific uremic arteriolopathy treated with bisphosphonates. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57:1021–1025.

Miss the ear, and you may miss the diagnosis

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

A 52-year-old woman presented with pain in both ears associated with redness and swelling. The symptoms appeared 3 weeks earlier. The pain had started on one side, then spread to the other over a period of 2 weeks. She denied fever, chills, rigor, rash, or upper respiratory symptoms. She had experienced similar but unilateral ear pain months before. Her medical history included bilateral knee pain and swelling (treated as osteoarthritis), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and hypothyroidism. She also reported progressive bilateral hearing loss, for which she now uses hearing aids. She had no history of conjunctivitis or uveitis.

Physical examination showed swelling and erythema of both ears, sparing the earlobes (Figure 1), as well as bilateral knee-joint tenderness and restricted joint movement. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated at 52 mm/h (reference range 0–20); the complete blood cell count, creatinine, and liver enzyme levels were normal. An autoimmune panel was negative for antinuclear antibody, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody, and rheumatoid factor.

A clinical diagnosis of relapsing polychondritis was made based on the McAdam criteria.1 The patient was initially started on steroids and then was maintained on methotrexate. Her symptoms improved dramatically by 3 weeks.

RELAPSING POLYCHONDRITIS

Relapsing polychondritis is a rare, chronic, and potentially multisystem disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of cartilaginous inflammation that often lead to progressive destruction of the cartilage.2,3

Auricular chondritis is the initial presentation in 43% of cases and eventually develops in 89% of patients.2,4 The earlobes are spared, as they are devoid of cartilage, and this feature helps to differentiate the condition from an infection.

If the condition is not treated, recurrent attacks can result in irreversible cartilage damage and drooping of the pinna (ie, “cauliflower ear”). Biopsy is usually avoided, as it may further damage the ear. The diagnostic criteria for relapsing polychondritis formulated by McAdam et al1 accommodate the different presentations in order to limit the need for biopsy. Systemic involvement may include external eye structures, vasculitis affecting the eighth cranial (vestibulocochlear) nerve, noninflammatory large-joint arthritis, and the trachea. There is also an association with myelodysplasia.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.

- McAdam LP, O’Hanlan MA, Bluestone R, Pearson CM. Relapsing polychondritis: prospective study of 23 patients and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1976; 55:193–215.

- Mathew SD, Battafarano DF, Morris MJ. Relapsing polychondritis in the Department of Defense population and review of the literature. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2012; 42:70–83.

- Letko E, Zafirakis P, Baltatzis S, Voudouri A, Livir-Rallatos C, Foster CS. Relapsing polychondritis: a clinical review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002; 31:384–395.

- Kent PD, Michet CJ, Luthra HS. Relapsing polychondritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2004; 16:56–61.