User login

Multicentric Reticulohistiocytosis With Arthralgia and Red-Orange Papulonodules

To the Editor:

A 50-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the dorsal aspect of the hands, abdomen, and face of 6 months’ duration. The eruption was associated with generalized arthralgia and fatigue. Within several weeks of onset of the cutaneous eruption, the patient developed swelling in the hands as well as worsening arthralgia. She was treated for presumed Lyme borreliosis but reported no improvement in the symptoms. She was then referred to dermatology for further management.

Physical examination revealed red-orange, edematous, monomorphic papulonodules scattered on the nasolabial folds, upper lip, and along the dorsal aspect of the hands and fingers (Figure 1). A brown rippled plaque was present on the left lower abdomen. The oral mucosa and nails were unremarkable. Laboratory studies showed elevated total cholesterol (244 mg/dL [reference range, <200 mg/dL]), low-density lipoproteins (130 mg/dL [reference range, 10–30 mg/dL]), aspartate aminotransferase (140 U/L [reference range, 10–30 U/L]), alanine aminotransferase (110 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]), and total bilirubin (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL]). White blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 with a homogenous pattern was found, and aldolase levels were elevated. Laboratory investigations for rheumatoid factor, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. A chest radiograph was normal.

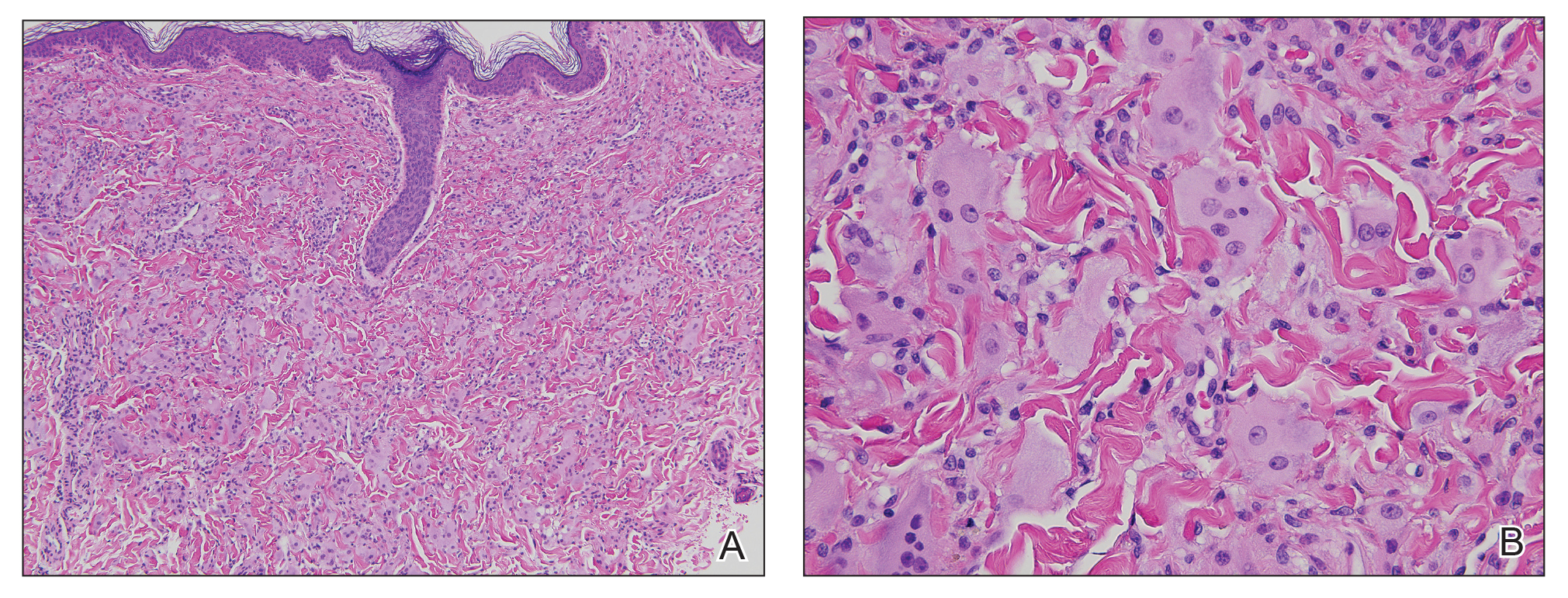

A punch biopsy from the right dorsal hand revealed a dermal proliferation of mononucleated and multinucleated epithelioid histiocytes with ample amounts of eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry revealed epithelioid histiocytes reactive for CD68, CD163, and factor XIIIA, and negative for S-100 and CD1a.

The patient was diagnosed with multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) and was initially treated with prednisone. Treatment was later augmented with etanercept and methotrexate with improvement in both the skin and joint symptoms.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis with both cutaneous and systemic features. Although case reports date back to the late 1800s, the term multicentric reticulohistiocytosis was first used in 1954.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is extremely uncommon and precludes thorough investigation of its etiology and management. The condition typically presents in the fifth to sixth decades of life and occurs more frequently in women with a female to male ratio estimated at 3 to 1.2,3 Pediatric cases have been reported but are exceedingly rare.4

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents with a severe erosive arthropathy known as arthritis mutilans. Patients display a symmetric polyarthritis that commonly involves the elbows, wrists, and proximal and distal aspects of the interphalangeal joints. Onset and progression can be rapid, and the erosive nature leads to deformities in up to 45% of patients.2,5,6 Cutaneous findings arise an average of 3 years after the development of arthritis, though one-fifth of patients will initially present with cutaneous findings followed by the development of arthritis at any time.3,6 Clinical features include flesh-colored to reddish brown or yellow papulonodules that range in size from several millimeters to 2 cm. The lesions most commonly occur on the face (eg, ears, nose, paranasal cheeks), scalp, dorsal and lateral aspects of the hands and fingers, and overlying articular regions of the extremities. Characteristic periungual lesions classically are referred to as coral beads.4,6 Patients commonly report pruritus that may precede the development of the papules and nodules. Other cutaneous manifestations include xanthelasma, nail changes, and a photodistributed erythematous maculopapular eruption that may mimic dermatomyositis.6

Cutaneous findings of MRH can mimic rheumatoid nodules, gout, Gottron papules of dermatomyositis, lipoid proteinosis, sarcoidosis, lepromatous leprosy, granuloma annulare, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, and fibroxanthoma.6,7 Histopathologic features may distinguish MRH from such entities. Findings include fairly well-circumscribed aggregates of large multinucleated giant cells with characteristic eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm. Histiocytes stain positively for CD68, HAM56, CD11b, and CD14, and variably for factor XIIIa. CD68, which is expressed by monocytes/macrophages, has been universally reported to be the most reliable marker of MRH. Negative staining for S-100 and CD1a supports a non-Langerhans origin for the involved histiocytes. If arthritic symptoms predominate, MRH must be distinguished from rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis.6,7

Mucosal involvement occurs in approximately 50% of patients and includes the presence of nodules in the oral, nasal, and pharyngeal mucosae, as well as eye structures.2,3 Histiocytic infiltration has been documented in the heart, lungs, thyroid, liver, stomach, kidneys, muscle, bone marrow, and urogenital tract. Histiocytes also can invade the cartilage of the ears and nose causing disfigurement and characteristic leonine facies. Pathologic fractures may occur with bone involvement.5

Systemic features associated with MRH include hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, hypergammaglobulinemia, and various autoimmune diseases. Patients less frequently report fever and weight loss.2,5,6,8 Additionally, a positive tuberculin test occurs in 12% to 50% of patients.6 Various autoimmune diseases occur in 6% to 17% of cases including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, Sjögren syndrome, and primary biliary cirrhosis.2,5,6,8 The most clinically salient feature of MRH is its association with malignant conditions, which occur in up to 31% of patients. A variety of cancers have been reported in association with MRH, including breast, cervical, ovarian, stomach, penile, lymphoma, mesothelioma, and melanoma.7

The etiology of MRH is unclear. Although onset may precede the development of a malignant condition and regress with treatment, it cannot be considered a true paraneoplastic disorder, as it has no association with a specific cancer and does not typically parallel the disease course.6,9 Reports of increased levels of inflammatory mediators released from macrophages and endothelial cells, specifically IL-12, IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), have been thought to drive the destruction of bone and cartilage.6 In particular, TNF-α acts to indirectly induce destruction by stimulating proteolytic activity in macrophages, similar to the pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis.8 Osteoclastic activity may play a role in the pathogenesis of MRH, as multinucleated giant cells in MRH can mature into osteoclasts by receptor activated nuclear factor–κB ligand signaling. In addition, patients treated with bisphosphonates have had decreased lacunar resorption.2,8

Initial management of MRH should include screening for hyperlipidemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, hyperglycemia, thyroid dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, as well as age-appropriate cancer screening. Imaging studies should evaluate for the presence of erosive arthritis. There are no well-defined treatment algorithms for MRH due to the rarity of the disease, and recommendations largely rely on case reports. Although spontaneous remission typically occurs within 5 to 10 years, the risk for joint destruction argues for early pharmacologic intervention. Current management includes the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and various immunosuppressants including oral glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, methotrexate, or azathioprine.2 A combination of methotrexate with cyclophosphamide or glucocorticoids also has shown efficacy.10 Anti–TNF-α agents, such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab, have been used with some success.2 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors used in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate may have an increased benefit.2,9,11 Evidence suggesting that TNF-α plays a role in the destruction of bone and cartilage led to the successful use of infliximab in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate, which prevented possible development of antibodies to infliximab and increased its efficacy.12 Bisphosphonate use in combination with glucocorticoids and methotrexate may prevent joint destruction without the serious adverse events associated with anti–TNF-α agents.2,9,13,14

- Goltz RW, Laymon CW. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis of the skin and synovia; reticulohistiocytoma or ganglioneuroma. AMA Arch Derma Syphilol. 1954;69:717-731.

- Islam AD, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a rare yet challenging disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:281-289.

- West KL, Sporn T, Puri PK. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a unique case with pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:228-232.

- Outland JD, Keiran SJ, Schikler KN, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis in a 14-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:527-531.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Trotta F, Castellino G, Lo Monaco A. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:759-772.

- Kalajian AH, Callen JP. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis successfully treated with infliximab: an illustrative case and evaluation of cytokine expression supporting anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arch Derm. 2008;144:1360-1366.

- Liang GC, Granston AS. Complete remission of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with combination therapy of steroid, cyclophosphamide, and low-dose pulse methotrexate. case report, review of the literature, and proposal for treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:171-174.

- Lovelace K, Loyd A, Adelson D, et al. Etanercept and the treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1167-1168.

- Lee MW, Lee EY, Jeong YI, et al. Successful treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of infliximab, prednisolone and methotrexate. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:478-479.

- Adamopoulos IE, Wordsworth PB, Edwards JR, et al. Osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1176-1185.

- Satoh M, Oyama N, Yamada H, et al. Treatment trial of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of predonisolone, methotrexate and alendronate. J Dermatol. 2008;35:168-171.

To the Editor:

A 50-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the dorsal aspect of the hands, abdomen, and face of 6 months’ duration. The eruption was associated with generalized arthralgia and fatigue. Within several weeks of onset of the cutaneous eruption, the patient developed swelling in the hands as well as worsening arthralgia. She was treated for presumed Lyme borreliosis but reported no improvement in the symptoms. She was then referred to dermatology for further management.

Physical examination revealed red-orange, edematous, monomorphic papulonodules scattered on the nasolabial folds, upper lip, and along the dorsal aspect of the hands and fingers (Figure 1). A brown rippled plaque was present on the left lower abdomen. The oral mucosa and nails were unremarkable. Laboratory studies showed elevated total cholesterol (244 mg/dL [reference range, <200 mg/dL]), low-density lipoproteins (130 mg/dL [reference range, 10–30 mg/dL]), aspartate aminotransferase (140 U/L [reference range, 10–30 U/L]), alanine aminotransferase (110 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]), and total bilirubin (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL]). White blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 with a homogenous pattern was found, and aldolase levels were elevated. Laboratory investigations for rheumatoid factor, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. A chest radiograph was normal.

A punch biopsy from the right dorsal hand revealed a dermal proliferation of mononucleated and multinucleated epithelioid histiocytes with ample amounts of eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry revealed epithelioid histiocytes reactive for CD68, CD163, and factor XIIIA, and negative for S-100 and CD1a.

The patient was diagnosed with multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) and was initially treated with prednisone. Treatment was later augmented with etanercept and methotrexate with improvement in both the skin and joint symptoms.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis with both cutaneous and systemic features. Although case reports date back to the late 1800s, the term multicentric reticulohistiocytosis was first used in 1954.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is extremely uncommon and precludes thorough investigation of its etiology and management. The condition typically presents in the fifth to sixth decades of life and occurs more frequently in women with a female to male ratio estimated at 3 to 1.2,3 Pediatric cases have been reported but are exceedingly rare.4

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents with a severe erosive arthropathy known as arthritis mutilans. Patients display a symmetric polyarthritis that commonly involves the elbows, wrists, and proximal and distal aspects of the interphalangeal joints. Onset and progression can be rapid, and the erosive nature leads to deformities in up to 45% of patients.2,5,6 Cutaneous findings arise an average of 3 years after the development of arthritis, though one-fifth of patients will initially present with cutaneous findings followed by the development of arthritis at any time.3,6 Clinical features include flesh-colored to reddish brown or yellow papulonodules that range in size from several millimeters to 2 cm. The lesions most commonly occur on the face (eg, ears, nose, paranasal cheeks), scalp, dorsal and lateral aspects of the hands and fingers, and overlying articular regions of the extremities. Characteristic periungual lesions classically are referred to as coral beads.4,6 Patients commonly report pruritus that may precede the development of the papules and nodules. Other cutaneous manifestations include xanthelasma, nail changes, and a photodistributed erythematous maculopapular eruption that may mimic dermatomyositis.6

Cutaneous findings of MRH can mimic rheumatoid nodules, gout, Gottron papules of dermatomyositis, lipoid proteinosis, sarcoidosis, lepromatous leprosy, granuloma annulare, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, and fibroxanthoma.6,7 Histopathologic features may distinguish MRH from such entities. Findings include fairly well-circumscribed aggregates of large multinucleated giant cells with characteristic eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm. Histiocytes stain positively for CD68, HAM56, CD11b, and CD14, and variably for factor XIIIa. CD68, which is expressed by monocytes/macrophages, has been universally reported to be the most reliable marker of MRH. Negative staining for S-100 and CD1a supports a non-Langerhans origin for the involved histiocytes. If arthritic symptoms predominate, MRH must be distinguished from rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis.6,7

Mucosal involvement occurs in approximately 50% of patients and includes the presence of nodules in the oral, nasal, and pharyngeal mucosae, as well as eye structures.2,3 Histiocytic infiltration has been documented in the heart, lungs, thyroid, liver, stomach, kidneys, muscle, bone marrow, and urogenital tract. Histiocytes also can invade the cartilage of the ears and nose causing disfigurement and characteristic leonine facies. Pathologic fractures may occur with bone involvement.5

Systemic features associated with MRH include hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, hypergammaglobulinemia, and various autoimmune diseases. Patients less frequently report fever and weight loss.2,5,6,8 Additionally, a positive tuberculin test occurs in 12% to 50% of patients.6 Various autoimmune diseases occur in 6% to 17% of cases including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, Sjögren syndrome, and primary biliary cirrhosis.2,5,6,8 The most clinically salient feature of MRH is its association with malignant conditions, which occur in up to 31% of patients. A variety of cancers have been reported in association with MRH, including breast, cervical, ovarian, stomach, penile, lymphoma, mesothelioma, and melanoma.7

The etiology of MRH is unclear. Although onset may precede the development of a malignant condition and regress with treatment, it cannot be considered a true paraneoplastic disorder, as it has no association with a specific cancer and does not typically parallel the disease course.6,9 Reports of increased levels of inflammatory mediators released from macrophages and endothelial cells, specifically IL-12, IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), have been thought to drive the destruction of bone and cartilage.6 In particular, TNF-α acts to indirectly induce destruction by stimulating proteolytic activity in macrophages, similar to the pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis.8 Osteoclastic activity may play a role in the pathogenesis of MRH, as multinucleated giant cells in MRH can mature into osteoclasts by receptor activated nuclear factor–κB ligand signaling. In addition, patients treated with bisphosphonates have had decreased lacunar resorption.2,8

Initial management of MRH should include screening for hyperlipidemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, hyperglycemia, thyroid dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, as well as age-appropriate cancer screening. Imaging studies should evaluate for the presence of erosive arthritis. There are no well-defined treatment algorithms for MRH due to the rarity of the disease, and recommendations largely rely on case reports. Although spontaneous remission typically occurs within 5 to 10 years, the risk for joint destruction argues for early pharmacologic intervention. Current management includes the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and various immunosuppressants including oral glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, methotrexate, or azathioprine.2 A combination of methotrexate with cyclophosphamide or glucocorticoids also has shown efficacy.10 Anti–TNF-α agents, such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab, have been used with some success.2 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors used in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate may have an increased benefit.2,9,11 Evidence suggesting that TNF-α plays a role in the destruction of bone and cartilage led to the successful use of infliximab in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate, which prevented possible development of antibodies to infliximab and increased its efficacy.12 Bisphosphonate use in combination with glucocorticoids and methotrexate may prevent joint destruction without the serious adverse events associated with anti–TNF-α agents.2,9,13,14

To the Editor:

A 50-year-old woman presented with an asymptomatic eruption on the dorsal aspect of the hands, abdomen, and face of 6 months’ duration. The eruption was associated with generalized arthralgia and fatigue. Within several weeks of onset of the cutaneous eruption, the patient developed swelling in the hands as well as worsening arthralgia. She was treated for presumed Lyme borreliosis but reported no improvement in the symptoms. She was then referred to dermatology for further management.

Physical examination revealed red-orange, edematous, monomorphic papulonodules scattered on the nasolabial folds, upper lip, and along the dorsal aspect of the hands and fingers (Figure 1). A brown rippled plaque was present on the left lower abdomen. The oral mucosa and nails were unremarkable. Laboratory studies showed elevated total cholesterol (244 mg/dL [reference range, <200 mg/dL]), low-density lipoproteins (130 mg/dL [reference range, 10–30 mg/dL]), aspartate aminotransferase (140 U/L [reference range, 10–30 U/L]), alanine aminotransferase (110 U/L [reference range, 10–40 U/L]), and total bilirubin (1.5 mg/dL [reference range, 0.3–1.2 mg/dL]). White blood cell count and C-reactive protein levels were within reference range. An antinuclear antibody titer of 1:80 with a homogenous pattern was found, and aldolase levels were elevated. Laboratory investigations for rheumatoid factor, Lyme disease, tuberculosis, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus were negative. A chest radiograph was normal.

A punch biopsy from the right dorsal hand revealed a dermal proliferation of mononucleated and multinucleated epithelioid histiocytes with ample amounts of eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm (Figure 2). Immunohistochemistry revealed epithelioid histiocytes reactive for CD68, CD163, and factor XIIIA, and negative for S-100 and CD1a.

The patient was diagnosed with multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) and was initially treated with prednisone. Treatment was later augmented with etanercept and methotrexate with improvement in both the skin and joint symptoms.

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is a rare, non–Langerhans cell histiocytosis with both cutaneous and systemic features. Although case reports date back to the late 1800s, the term multicentric reticulohistiocytosis was first used in 1954.1 Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis is extremely uncommon and precludes thorough investigation of its etiology and management. The condition typically presents in the fifth to sixth decades of life and occurs more frequently in women with a female to male ratio estimated at 3 to 1.2,3 Pediatric cases have been reported but are exceedingly rare.4

Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis typically presents with a severe erosive arthropathy known as arthritis mutilans. Patients display a symmetric polyarthritis that commonly involves the elbows, wrists, and proximal and distal aspects of the interphalangeal joints. Onset and progression can be rapid, and the erosive nature leads to deformities in up to 45% of patients.2,5,6 Cutaneous findings arise an average of 3 years after the development of arthritis, though one-fifth of patients will initially present with cutaneous findings followed by the development of arthritis at any time.3,6 Clinical features include flesh-colored to reddish brown or yellow papulonodules that range in size from several millimeters to 2 cm. The lesions most commonly occur on the face (eg, ears, nose, paranasal cheeks), scalp, dorsal and lateral aspects of the hands and fingers, and overlying articular regions of the extremities. Characteristic periungual lesions classically are referred to as coral beads.4,6 Patients commonly report pruritus that may precede the development of the papules and nodules. Other cutaneous manifestations include xanthelasma, nail changes, and a photodistributed erythematous maculopapular eruption that may mimic dermatomyositis.6

Cutaneous findings of MRH can mimic rheumatoid nodules, gout, Gottron papules of dermatomyositis, lipoid proteinosis, sarcoidosis, lepromatous leprosy, granuloma annulare, xanthoma, xanthogranuloma, and fibroxanthoma.6,7 Histopathologic features may distinguish MRH from such entities. Findings include fairly well-circumscribed aggregates of large multinucleated giant cells with characteristic eosinophilic ground-glass cytoplasm. Histiocytes stain positively for CD68, HAM56, CD11b, and CD14, and variably for factor XIIIa. CD68, which is expressed by monocytes/macrophages, has been universally reported to be the most reliable marker of MRH. Negative staining for S-100 and CD1a supports a non-Langerhans origin for the involved histiocytes. If arthritic symptoms predominate, MRH must be distinguished from rheumatoid and psoriatic arthritis.6,7

Mucosal involvement occurs in approximately 50% of patients and includes the presence of nodules in the oral, nasal, and pharyngeal mucosae, as well as eye structures.2,3 Histiocytic infiltration has been documented in the heart, lungs, thyroid, liver, stomach, kidneys, muscle, bone marrow, and urogenital tract. Histiocytes also can invade the cartilage of the ears and nose causing disfigurement and characteristic leonine facies. Pathologic fractures may occur with bone involvement.5

Systemic features associated with MRH include hyperlipidemia, diabetes mellitus, thyroid disease, hypergammaglobulinemia, and various autoimmune diseases. Patients less frequently report fever and weight loss.2,5,6,8 Additionally, a positive tuberculin test occurs in 12% to 50% of patients.6 Various autoimmune diseases occur in 6% to 17% of cases including systemic lupus erythematosus, systemic sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis, dermatomyositis, Sjögren syndrome, and primary biliary cirrhosis.2,5,6,8 The most clinically salient feature of MRH is its association with malignant conditions, which occur in up to 31% of patients. A variety of cancers have been reported in association with MRH, including breast, cervical, ovarian, stomach, penile, lymphoma, mesothelioma, and melanoma.7

The etiology of MRH is unclear. Although onset may precede the development of a malignant condition and regress with treatment, it cannot be considered a true paraneoplastic disorder, as it has no association with a specific cancer and does not typically parallel the disease course.6,9 Reports of increased levels of inflammatory mediators released from macrophages and endothelial cells, specifically IL-12, IL-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), have been thought to drive the destruction of bone and cartilage.6 In particular, TNF-α acts to indirectly induce destruction by stimulating proteolytic activity in macrophages, similar to the pathogenesis of joint damage in rheumatoid arthritis.8 Osteoclastic activity may play a role in the pathogenesis of MRH, as multinucleated giant cells in MRH can mature into osteoclasts by receptor activated nuclear factor–κB ligand signaling. In addition, patients treated with bisphosphonates have had decreased lacunar resorption.2,8

Initial management of MRH should include screening for hyperlipidemia, hypergammaglobulinemia, hyperglycemia, thyroid dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases, as well as age-appropriate cancer screening. Imaging studies should evaluate for the presence of erosive arthritis. There are no well-defined treatment algorithms for MRH due to the rarity of the disease, and recommendations largely rely on case reports. Although spontaneous remission typically occurs within 5 to 10 years, the risk for joint destruction argues for early pharmacologic intervention. Current management includes the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and various immunosuppressants including oral glucocorticoids, cyclophosphamide, chlorambucil, methotrexate, or azathioprine.2 A combination of methotrexate with cyclophosphamide or glucocorticoids also has shown efficacy.10 Anti–TNF-α agents, such as etanercept, adalimumab, and infliximab, have been used with some success.2 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors used in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate may have an increased benefit.2,9,11 Evidence suggesting that TNF-α plays a role in the destruction of bone and cartilage led to the successful use of infliximab in combination with oral glucocorticoids and methotrexate, which prevented possible development of antibodies to infliximab and increased its efficacy.12 Bisphosphonate use in combination with glucocorticoids and methotrexate may prevent joint destruction without the serious adverse events associated with anti–TNF-α agents.2,9,13,14

- Goltz RW, Laymon CW. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis of the skin and synovia; reticulohistiocytoma or ganglioneuroma. AMA Arch Derma Syphilol. 1954;69:717-731.

- Islam AD, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a rare yet challenging disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:281-289.

- West KL, Sporn T, Puri PK. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a unique case with pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:228-232.

- Outland JD, Keiran SJ, Schikler KN, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis in a 14-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:527-531.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Trotta F, Castellino G, Lo Monaco A. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:759-772.

- Kalajian AH, Callen JP. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis successfully treated with infliximab: an illustrative case and evaluation of cytokine expression supporting anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arch Derm. 2008;144:1360-1366.

- Liang GC, Granston AS. Complete remission of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with combination therapy of steroid, cyclophosphamide, and low-dose pulse methotrexate. case report, review of the literature, and proposal for treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:171-174.

- Lovelace K, Loyd A, Adelson D, et al. Etanercept and the treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1167-1168.

- Lee MW, Lee EY, Jeong YI, et al. Successful treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of infliximab, prednisolone and methotrexate. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:478-479.

- Adamopoulos IE, Wordsworth PB, Edwards JR, et al. Osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1176-1185.

- Satoh M, Oyama N, Yamada H, et al. Treatment trial of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of predonisolone, methotrexate and alendronate. J Dermatol. 2008;35:168-171.

- Goltz RW, Laymon CW. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis of the skin and synovia; reticulohistiocytoma or ganglioneuroma. AMA Arch Derma Syphilol. 1954;69:717-731.

- Islam AD, Naguwa SM, Cheema GS, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a rare yet challenging disease. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2013;45:281-289.

- West KL, Sporn T, Puri PK. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: a unique case with pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Dermatol. 2012;148:228-232.

- Outland JD, Keiran SJ, Schikler KN, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis in a 14-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol. 2002;19:527-531.

- Gorman JD, Danning C, Schumacher HR, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis: case report with immunohistochemical analysis and literature review. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43:930-938.

- Tajirian AL, Malik MK, Robinson-Bostom L, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:486-492.

- Luz FB, Gaspar TAP, Kalil-Gaspar N, et al. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:524-531.

- Trotta F, Castellino G, Lo Monaco A. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2004;18:759-772.

- Kalajian AH, Callen JP. Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis successfully treated with infliximab: an illustrative case and evaluation of cytokine expression supporting anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy. Arch Derm. 2008;144:1360-1366.

- Liang GC, Granston AS. Complete remission of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with combination therapy of steroid, cyclophosphamide, and low-dose pulse methotrexate. case report, review of the literature, and proposal for treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 1996;39:171-174.

- Lovelace K, Loyd A, Adelson D, et al. Etanercept and the treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1167-1168.

- Lee MW, Lee EY, Jeong YI, et al. Successful treatment of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of infliximab, prednisolone and methotrexate. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:478-479.

- Adamopoulos IE, Wordsworth PB, Edwards JR, et al. Osteoclast differentiation and bone resorption in multicentric reticulohistiocytosis. Hum Pathol. 2006;37:1176-1185.

- Satoh M, Oyama N, Yamada H, et al. Treatment trial of multicentric reticulohistiocytosis with a combination of predonisolone, methotrexate and alendronate. J Dermatol. 2008;35:168-171.

Practice Points

- Multicentric reticulohistiocytosis (MRH) is an important entity to recognize given its association with underlying malignancy and irreversible destructive arthritis.

- Diagnosis of MRH warrants extensive review of systems, age-appropriate cancer screening, and relevant systemic workup.

- Early pharmacologic intervention should be initiated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or immunosuppressant agents.

Postirradiation Morphea: Unique Presentation on the Breast

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

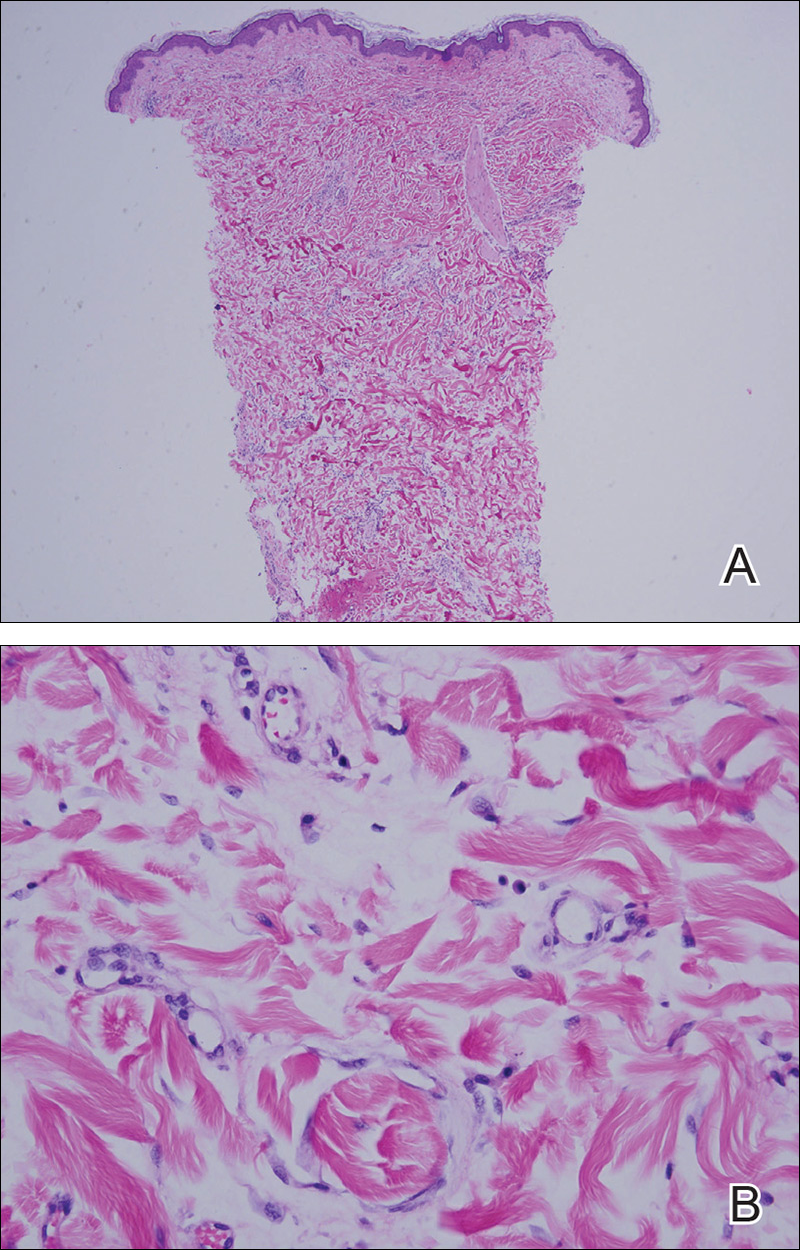

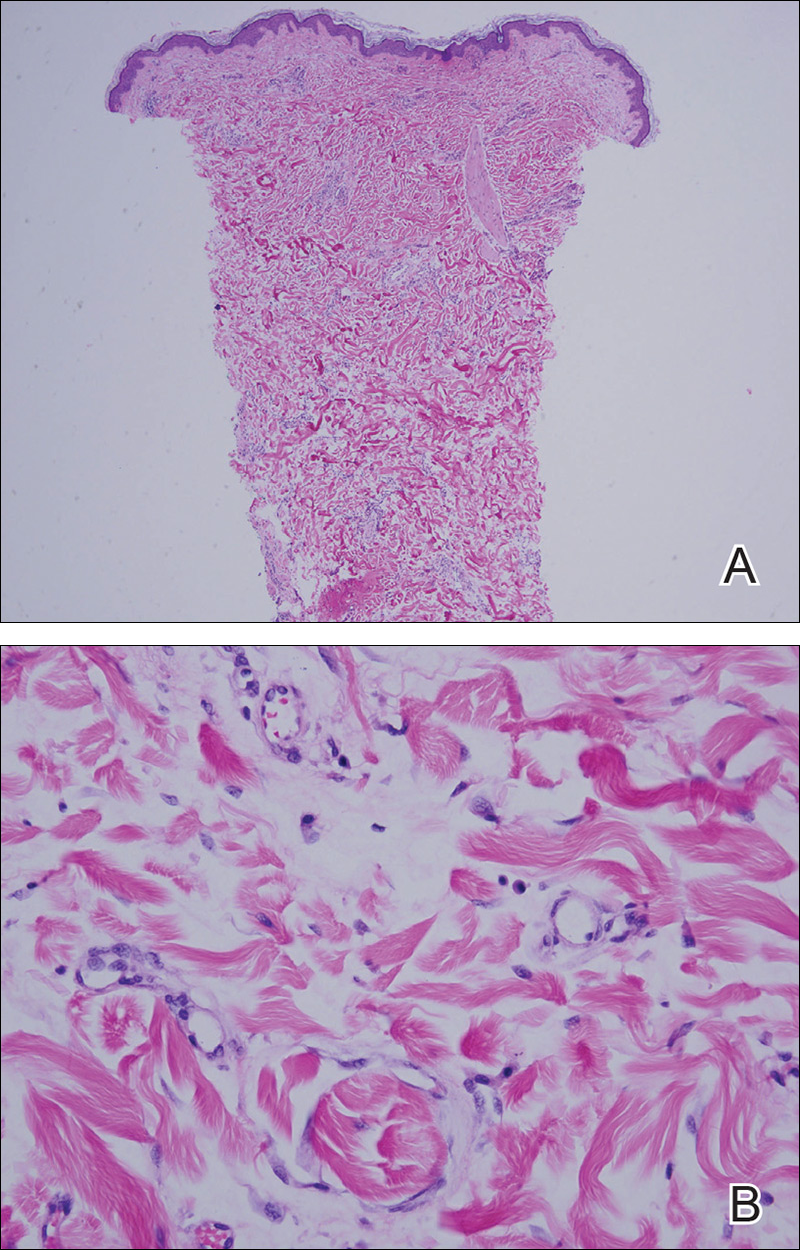

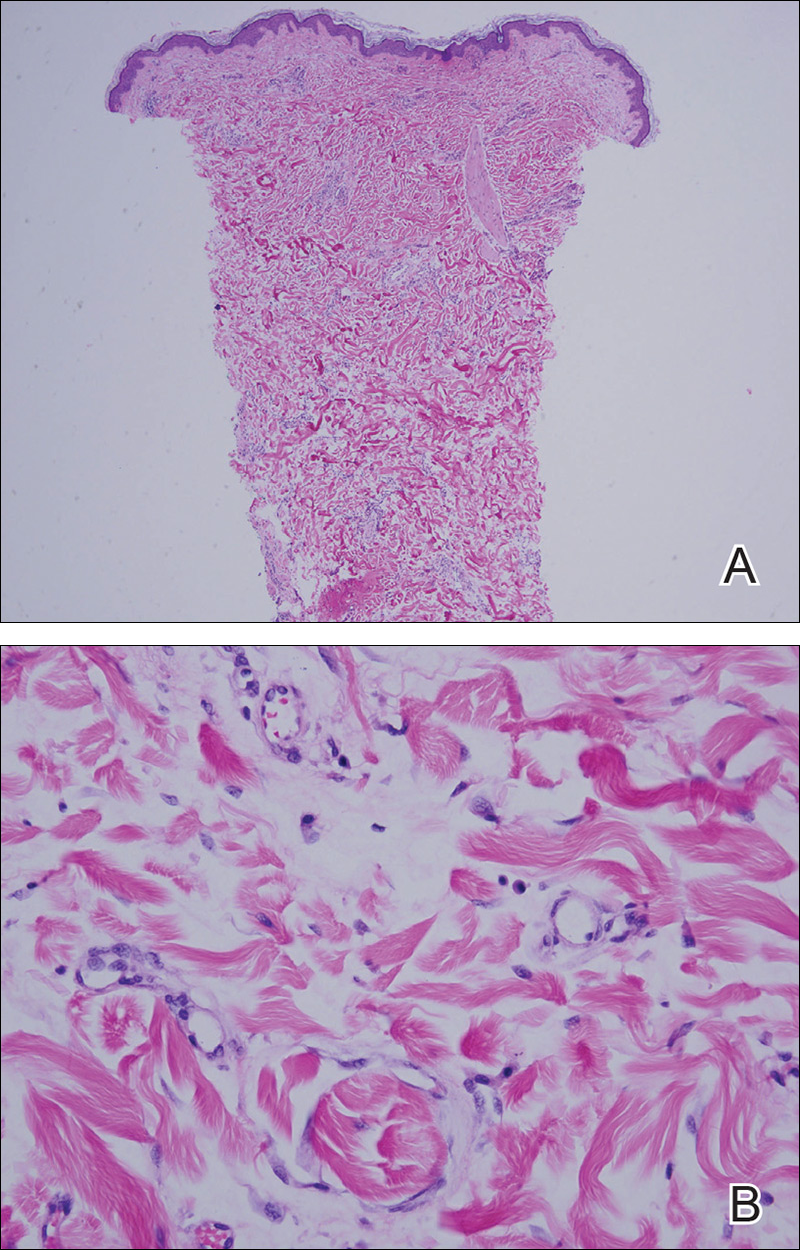

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

To the Editor:

Postirradiation morphea (PIM) is a rare but well-documented phenomenon that primarily occurs in breast cancer patients who have received radiation therapy; however, it also has been reported in patients who have received radiation therapy for lymphoma as well as endocervical, endometrial, and gastric carcinomas.1 Importantly, clinicians must be able to recognize and differentiate this condition from other causes of new-onset induration and erythema of the breast, such as cancer recurrence, a new primary malignancy, or inflammatory etiologies (eg, radiation or contact dermatitis). Typically, PIM presents months to years after radiation therapy as an erythematous patch within the irradiated area that progressively becomes indurated. We report an unusual case of PIM with a reticulated appearance occurring 3 weeks after radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and surgery for an infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast.

A 62-year-old woman presented to the dermatology department with a stage IIA, lymph node–negative, estrogen and progesterone receptor–negative, human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–negative infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the left breast. She was treated with a partial mastectomy of the left breast followed by external beam radiotherapy to the entire left breast in combination with chemotherapy (doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, paclitaxel). The patient received 15 fractions of 270 cGy (4050 cGy total) with a weekly 600-cGy boost over 21 days without any complications.

Three weeks after finishing radiation therapy, the patient developed redness and swelling of the left breast that did not encompass the entire radiation field. There was no associated pain or pruritus. She was treated by her surgical oncologist with topical calendula and 3 courses of cephalexin for suspected mastitis with only modest improvement, then was referred to dermatology 3 months later.

At the initial dermatology evaluation, the patient reported little improvement after antibiotics and topical calendula. On physical examination, there were erythematous, reticulated, dusky, indurated patches on the entire left breast. The area of most pronounced induration surrounded the surgical scar on the left superior breast. Punch biopsy for hematoxylin and eosin staining and tissue cultures was obtained at this appointment. The patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily and was instructed to apply triamcinolone ointment 0.1% twice daily to the affected area. After 1 month of therapy, she reported slight improvement in the degree of erythema with this regimen, but the involved area continued to extend outside of the radiation field to the central chest wall and medial right breast (Figure 1). Two additional biopsies—one from the central chest and another from the right breast—were then taken over the course of 4 months, given the consistently inconclusive clinicopathologic nature and failure of the eruption to respond to antibiotics plus topical corticosteroids.

Punch biopsy from the central chest revealed a sparse perivascular infiltrate comprised predominantly of lymphocytes with occasional eosinophils (Figure 2). There were foci suggestive of early dermal sclerosis, an increased number of small blood vessels in the dermis, and scattered enlarged fibroblasts. Metastatic carcinoma was not identified. Although the histologic findings were not entirely specific, the changes were most suggestive of PIM, for which the patient was started on pentoxifylline (400 mg 3 times daily) and oral vitamin E supplementation (400 IU daily). At subsequent follow-up appointments, she showed markedly decreased skin erythema and induration.

Morphea, also known as localized scleroderma, is an inflammatory skin condition characterized by sclerosis of the dermis and subcutis leading to scarlike tissue formation. Worldwide incidence ranges from 0.4 to 2.7 cases per 100,000 individuals with a predilection for white women.2 Unlike systemic scleroderma, morphea patients lack Raynaud phenomenon and visceral involvement.3,4

There are several clinical subtypes of morphea, including plaque, linear, generalized, and pansclerotic morphea. Lesions may vary in appearance based on configuration, stage of development, and depth of involvement.4 During the earliest phases, morphea lesions are asymptomatic, asymmetrically distributed, erythematous to violaceous patches or subtly indurated plaques expanding centrifugally with a lilac ring. Central sclerosis with loss of follicles and sweat glands is a later finding associated with advanced disease. Moreover, some reports of early-stage morphea have suggested a reticulated or geographic vascular morphology that may be misdiagnosed for other conditions such as a port-wine stain.5

Local skin exposures have long been hypothesized to contribute to development of morphea, including infection, especially Borrelia burgdorferi; trauma; chronic venous insufficiency; cosmetic surgery; medications; and exposure to toxic cooking oils, silicones, silica, pesticides, organic solvents, and vinyl chloride.2,6,7

Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea. It was first described in 1905 but then rarely discussed until a 1989 case series of 9 patients, 7 of whom had received irradiation for breast cancer.8,9 Today, the increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in PIM incidence.10

In contrast to other radiation-induced skin conditions, development of PIM is independent of the presence or absence of adjuvant chemotherapy, type of radiation therapy, or the total radiation dose or fractionation number, with reported doses ranging from less than 20.0 Gy to up to 59.4 Gy and dose fractions ranging from 10 to 30. In 20% to 30% of cases, PIM extends beyond the radiation field, sometimes involving distant sites never exposed to high-energy rays.1,10,11 This observation suggests a mechanism reliant on more widespread cascade rather than solely local tissue damage.

Prominent culture-negative, lymphoplasmacytic inflammation is another important diagnostic clue. Radiation dermatitis and fibrosis do not have the marked erythematous to violaceous hue seen in early morphea plaques. This color seen in early morphea plaques may be intense enough and in a geographic pattern, emulating a vascular lesion.

There is no standardized treatment of PIM, but traditional therapies for morphea may provide some benefit. Several randomized controlled clinical trials have shown success with pentoxifylline and oral vitamin E supplementation to treat or prevent radiation-induced breast fibrosis.12 Extrapolating from this data, our patient was started on this combination therapy and showed marked improvement in skin color and texture.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

- Morganroth PA, Dehoratius D, Curry H, et al. Postirradiation morphea: a case report with a review of the literature and summary of the clinicopathologic differential diagnosis [published online October 4, 2013]. Am J

Dermatopathol. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181cb3fdd. - Fett N, Werth VP. Update on morphea: part I. epidemiology, clinical presentation, and pathogenesis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:217-228; quiz 229-230.

- Noh JW, Kim J, Kim JW. Localized scleroderma: a clinical study at a single center in Korea. Int J Rheum Dis. 2013;16:437-441.

- Vasquez R, Sendejo C, Jacobe H. Morphea and other localized forms of scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24:685-693.

- Nijhawan RI, Bard S, Blyumin M, et al. Early localized morphea mimicking an acquired port-wine stain. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:779-782.

- Haustein UF, Ziegler V. Environmentally induced systemic sclerosis-like disorders. Int J Dermatol. 1985;24:147-151.

- Mora GF. Systemic sclerosis: environmental factors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:2383-2396.

- Colver GB, Rodger A, Mortimer PS, et al. Post-irradiation morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 1989;120:831-835.

- Crocker HR. Diseases of the Skin: Their Description, Pathology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Philadelphia, PA: P. Blakiston Son & Co; 1905.

- Laetsch B, Hofer T, Lombriser N, et al. Irradiation-induced morphea: x-rays as triggers of autoimmunity. Dermatology. 2011;223:9-12.

- Shetty G, Lewis F, Thrush S. Morphea of the breast: case reports and review of literature. Breast J. 2007;13:302-304.

- Jacobson G, Bhatia S, Smith BJ, et al. Randomized trial of pentoxifylline and vitamin E vs standard follow-up after breast irradiation to prevent breast fibrosis, evaluated by tissue compliance meter. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2013;85:604-608.

Practice Points

- Radiation therapy is an often overlooked cause of morphea.

- The increasing popularity of lumpectomy plus radiation therapy for treatment of early-stage breast cancer has led to a rise in postirradiation morphea incidence.

- Tissue changes occur as early as weeks or as late as 32 years after radiation treatment.

- Postirradiation morphea may extend beyond the radiation field.