User login

Do asymptomatic adults need screening EKGs?

PROBABLY NOT. Although certain electrocardiogram (EKG) findings in asymptomatic adults are associated with increased mortality (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, high-quality cohort studies), no randomized trials demonstrate that any intervention based on abnormal screening EKGs improves outcomes in this group of patients. Comparison to a baseline EKG has a minimal effect on emergency department (ED) management.(SOR: B, 2 prospective studies and one retrospective study).

Evidence summary

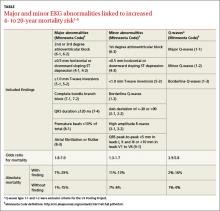

The US Pooling Project divided EKG abnormalities into major and minor findings.1 A number of large cohort studies have shown that both major and minor findings are associated with an elevated odds ratio for mortality (TABLE).1-5 However, these studies, completed before the development of modern medical management of acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease, may no longer estimate mortality accurately. Moreover, no studies have examined the effect of screening EKGs on coronary heart disease (CHD) outcomes.

Neither major nor minor EKG abnormalities linked to higher mortality

A 2012 cohort study—which included Q-waves as major criteria and examined fewer minor abnormalities than previous studies—followed 2192 patients 70 to 79 years of age for 8 years.6 The study enrolled a higher percentage of women and blacks than earlier investigations had.

Major EKG abnormalities predicted an increase in CHD events (hazard ratio [HR]=1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-1.90) as did minor abnormalities (HR=1.35; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81). In contrast to earlier studies, which tended to enroll younger patients, neither type of abnormality was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality.6

Including EKG abnormalities in a regression model of traditional risk factors improved stratification (overall net reclassification improvement [NRI]=7.4%; 95% CI, 3.1%-19.0%).6 No low-risk patients were reclassified as high risk and no high-risk patients were reclassified as low risk. Overall, 156 intermediate risk patients were correctly reclassified and an equal number were incorrectly reclassified. Adding EKG abnormalities to the Framingham Risk Score (which hasn’t been validated in adults >75 years) didn’t significantly improve stratification (NRI=5.7%; 95% CI, −0.4% to 11.8%).6

Comparing ED with baseline EKGs has little effect on management

A 1980 retrospective study looked at 236 patients with acute chest pain and no known CHD who were seen in the ED. Comparing routine baseline EKGs obtained before ED presentation for 6 of 41 patients with equivocal EKGs in the ED—including T-wave inversions, nonspecific T-wave and ST-segment abnormalities, and bundle branch blocks—prevented 2 admissions (no EKG change from baseline) and caused 4 unnecessary admissions (EKG changed from baseline with no subsequent evidence of acute coronary syndromes).7

A 1985 prospective study of 84 ED patients, in which treating physicians were given baseline EKGs after committing to an initial disposition plan, showed that the baseline EKG altered the decision to admit or discharge in only one case.8

A 1990 prospective multicenter study of 5673 patients older than 30 years—41% of whom had known CHD—reported that when the current EKG was consistent with ischemia or infarction, a baseline EKG showing the changes to be old (10% of study population) increased the likelihood that the patient would be discharged from the ED to home (26% vs 12%; risk difference=14%; 95% CI, 7%-23%). Unlike previous studies, however, the exact role of the baseline EKG in the admission decision was isolated not by study design but rather by multivariate logistic regression modeling.9

Recommendations

The 2010 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults states that a resting EKG is probably indicated in patients with diabetes and hypertension and that its usefulness in patients without these conditions isn’t well established.2

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening EKGs in adults at low risk for CHD events (grade D recommendation).10

1. Sosenko J, Gardner L. Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to incidence of major coronary events: final report of the pooling project. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:201-306.

2. Greenland P, Alpert J, Beller G, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50-e103.

3. Sox HC Jr, Garber AM, Littenberg B. The resting electrocardiogram as a screening test. A clinical analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:489-502.

4. DeBaquer D, De Backer G, Kornitzer M, et al. Prognostic value of ECG findings for total, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease death in men and women. Heart. 1998;80: 570-577.

5. Whinnicup P, Goya W, Marcarlane P, et al. Resting electrocardiogram and risk of coronary heart disease in middle-aged British men. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1995;2:533-543.

6. Auer R, Bauer DC, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Association of major and minor ECG abnormalities with coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2012;307:1497-1505.

7. Rubenstein LZ, Greenfield S. The baseline ECG in the evaluation of acute cardiac complaints. JAMA. 1980;244:2536-2539.

8. Hoffman JR, Igarashi E. Influence of electrocardiographic findings on admission decisions in patients with acute chest pain. Am J Med. 1985;79:699-707.

9. Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg MC, et al. Impact of the availability of a prior electrocardiogram on the triage of the patient with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:381-388.

10. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

PROBABLY NOT. Although certain electrocardiogram (EKG) findings in asymptomatic adults are associated with increased mortality (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, high-quality cohort studies), no randomized trials demonstrate that any intervention based on abnormal screening EKGs improves outcomes in this group of patients. Comparison to a baseline EKG has a minimal effect on emergency department (ED) management.(SOR: B, 2 prospective studies and one retrospective study).

Evidence summary

The US Pooling Project divided EKG abnormalities into major and minor findings.1 A number of large cohort studies have shown that both major and minor findings are associated with an elevated odds ratio for mortality (TABLE).1-5 However, these studies, completed before the development of modern medical management of acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease, may no longer estimate mortality accurately. Moreover, no studies have examined the effect of screening EKGs on coronary heart disease (CHD) outcomes.

Neither major nor minor EKG abnormalities linked to higher mortality

A 2012 cohort study—which included Q-waves as major criteria and examined fewer minor abnormalities than previous studies—followed 2192 patients 70 to 79 years of age for 8 years.6 The study enrolled a higher percentage of women and blacks than earlier investigations had.

Major EKG abnormalities predicted an increase in CHD events (hazard ratio [HR]=1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-1.90) as did minor abnormalities (HR=1.35; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81). In contrast to earlier studies, which tended to enroll younger patients, neither type of abnormality was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality.6

Including EKG abnormalities in a regression model of traditional risk factors improved stratification (overall net reclassification improvement [NRI]=7.4%; 95% CI, 3.1%-19.0%).6 No low-risk patients were reclassified as high risk and no high-risk patients were reclassified as low risk. Overall, 156 intermediate risk patients were correctly reclassified and an equal number were incorrectly reclassified. Adding EKG abnormalities to the Framingham Risk Score (which hasn’t been validated in adults >75 years) didn’t significantly improve stratification (NRI=5.7%; 95% CI, −0.4% to 11.8%).6

Comparing ED with baseline EKGs has little effect on management

A 1980 retrospective study looked at 236 patients with acute chest pain and no known CHD who were seen in the ED. Comparing routine baseline EKGs obtained before ED presentation for 6 of 41 patients with equivocal EKGs in the ED—including T-wave inversions, nonspecific T-wave and ST-segment abnormalities, and bundle branch blocks—prevented 2 admissions (no EKG change from baseline) and caused 4 unnecessary admissions (EKG changed from baseline with no subsequent evidence of acute coronary syndromes).7

A 1985 prospective study of 84 ED patients, in which treating physicians were given baseline EKGs after committing to an initial disposition plan, showed that the baseline EKG altered the decision to admit or discharge in only one case.8

A 1990 prospective multicenter study of 5673 patients older than 30 years—41% of whom had known CHD—reported that when the current EKG was consistent with ischemia or infarction, a baseline EKG showing the changes to be old (10% of study population) increased the likelihood that the patient would be discharged from the ED to home (26% vs 12%; risk difference=14%; 95% CI, 7%-23%). Unlike previous studies, however, the exact role of the baseline EKG in the admission decision was isolated not by study design but rather by multivariate logistic regression modeling.9

Recommendations

The 2010 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults states that a resting EKG is probably indicated in patients with diabetes and hypertension and that its usefulness in patients without these conditions isn’t well established.2

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening EKGs in adults at low risk for CHD events (grade D recommendation).10

PROBABLY NOT. Although certain electrocardiogram (EKG) findings in asymptomatic adults are associated with increased mortality (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, high-quality cohort studies), no randomized trials demonstrate that any intervention based on abnormal screening EKGs improves outcomes in this group of patients. Comparison to a baseline EKG has a minimal effect on emergency department (ED) management.(SOR: B, 2 prospective studies and one retrospective study).

Evidence summary

The US Pooling Project divided EKG abnormalities into major and minor findings.1 A number of large cohort studies have shown that both major and minor findings are associated with an elevated odds ratio for mortality (TABLE).1-5 However, these studies, completed before the development of modern medical management of acute coronary syndrome and stable coronary artery disease, may no longer estimate mortality accurately. Moreover, no studies have examined the effect of screening EKGs on coronary heart disease (CHD) outcomes.

Neither major nor minor EKG abnormalities linked to higher mortality

A 2012 cohort study—which included Q-waves as major criteria and examined fewer minor abnormalities than previous studies—followed 2192 patients 70 to 79 years of age for 8 years.6 The study enrolled a higher percentage of women and blacks than earlier investigations had.

Major EKG abnormalities predicted an increase in CHD events (hazard ratio [HR]=1.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.20-1.90) as did minor abnormalities (HR=1.35; 95% CI, 1.02-1.81). In contrast to earlier studies, which tended to enroll younger patients, neither type of abnormality was associated with a significantly increased risk of all-cause mortality.6

Including EKG abnormalities in a regression model of traditional risk factors improved stratification (overall net reclassification improvement [NRI]=7.4%; 95% CI, 3.1%-19.0%).6 No low-risk patients were reclassified as high risk and no high-risk patients were reclassified as low risk. Overall, 156 intermediate risk patients were correctly reclassified and an equal number were incorrectly reclassified. Adding EKG abnormalities to the Framingham Risk Score (which hasn’t been validated in adults >75 years) didn’t significantly improve stratification (NRI=5.7%; 95% CI, −0.4% to 11.8%).6

Comparing ED with baseline EKGs has little effect on management

A 1980 retrospective study looked at 236 patients with acute chest pain and no known CHD who were seen in the ED. Comparing routine baseline EKGs obtained before ED presentation for 6 of 41 patients with equivocal EKGs in the ED—including T-wave inversions, nonspecific T-wave and ST-segment abnormalities, and bundle branch blocks—prevented 2 admissions (no EKG change from baseline) and caused 4 unnecessary admissions (EKG changed from baseline with no subsequent evidence of acute coronary syndromes).7

A 1985 prospective study of 84 ED patients, in which treating physicians were given baseline EKGs after committing to an initial disposition plan, showed that the baseline EKG altered the decision to admit or discharge in only one case.8

A 1990 prospective multicenter study of 5673 patients older than 30 years—41% of whom had known CHD—reported that when the current EKG was consistent with ischemia or infarction, a baseline EKG showing the changes to be old (10% of study population) increased the likelihood that the patient would be discharged from the ED to home (26% vs 12%; risk difference=14%; 95% CI, 7%-23%). Unlike previous studies, however, the exact role of the baseline EKG in the admission decision was isolated not by study design but rather by multivariate logistic regression modeling.9

Recommendations

The 2010 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association (ACCF/AHA) guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults states that a resting EKG is probably indicated in patients with diabetes and hypertension and that its usefulness in patients without these conditions isn’t well established.2

The US Preventive Services Task Force recommends against screening EKGs in adults at low risk for CHD events (grade D recommendation).10

1. Sosenko J, Gardner L. Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to incidence of major coronary events: final report of the pooling project. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:201-306.

2. Greenland P, Alpert J, Beller G, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50-e103.

3. Sox HC Jr, Garber AM, Littenberg B. The resting electrocardiogram as a screening test. A clinical analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:489-502.

4. DeBaquer D, De Backer G, Kornitzer M, et al. Prognostic value of ECG findings for total, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease death in men and women. Heart. 1998;80: 570-577.

5. Whinnicup P, Goya W, Marcarlane P, et al. Resting electrocardiogram and risk of coronary heart disease in middle-aged British men. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1995;2:533-543.

6. Auer R, Bauer DC, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Association of major and minor ECG abnormalities with coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2012;307:1497-1505.

7. Rubenstein LZ, Greenfield S. The baseline ECG in the evaluation of acute cardiac complaints. JAMA. 1980;244:2536-2539.

8. Hoffman JR, Igarashi E. Influence of electrocardiographic findings on admission decisions in patients with acute chest pain. Am J Med. 1985;79:699-707.

9. Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg MC, et al. Impact of the availability of a prior electrocardiogram on the triage of the patient with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:381-388.

10. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

1. Sosenko J, Gardner L. Relationship of blood pressure, serum cholesterol, smoking habit, relative weight and ECG abnormalities to incidence of major coronary events: final report of the pooling project. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31:201-306.

2. Greenland P, Alpert J, Beller G, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:e50-e103.

3. Sox HC Jr, Garber AM, Littenberg B. The resting electrocardiogram as a screening test. A clinical analysis. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:489-502.

4. DeBaquer D, De Backer G, Kornitzer M, et al. Prognostic value of ECG findings for total, cardiovascular disease, and coronary heart disease death in men and women. Heart. 1998;80: 570-577.

5. Whinnicup P, Goya W, Marcarlane P, et al. Resting electrocardiogram and risk of coronary heart disease in middle-aged British men. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1995;2:533-543.

6. Auer R, Bauer DC, Marques-Vidal P, et al. Association of major and minor ECG abnormalities with coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2012;307:1497-1505.

7. Rubenstein LZ, Greenfield S. The baseline ECG in the evaluation of acute cardiac complaints. JAMA. 1980;244:2536-2539.

8. Hoffman JR, Igarashi E. Influence of electrocardiographic findings on admission decisions in patients with acute chest pain. Am J Med. 1985;79:699-707.

9. Lee TH, Cook EF, Weisberg MC, et al. Impact of the availability of a prior electrocardiogram on the triage of the patient with acute chest pain. J Gen Intern Med. 1990;5:381-388.

10. Chou R, Arora B, Dana T, et al. Screening asymptomatic adults with resting or exercise electrocardiography: a review of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:375-385.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best treatment for plant-induced contact dermatitis?

IT’S UNCLEAR which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

It’s unclear which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Two prospective, self-controlled cohort studies (N=30) showed that high-potency topical steroids improved symptoms associated with artificially induced Rhus dermatitis in a group with a history of that type of dermatitis.

The first study found that 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment applied twice a day significantly reduced overall vesiculation, erythema, induration, and pruritus compared with the control (P<.05, .01, .01, and .05, respectively).1 Investigators evaluated erythema, induration, and pruritus on a scale of 0 to 3 (absent, mild, moderate, or severe) and graded vesiculation on a similar 0- to 3-point scale (a frank bulla was graded 3). They started treatment at 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure and followed patients for 14 days. The greatest difference in mean scores—a reduction in vesiculation scores of approximately 1 point—occurred between 2 and 7 days of therapy.

The second study compared improvement in symptoms of Rhus dermatitis with daily application of topical steroids of different potencies and a control ointment.2 Investigators evaluated healing using a 0- to 4-point scale (0=clearing and 4=marked edema, erythema, and vesiculation). They found that lower-potency topical steroids such as 1% hydrocortisone and 0.1% triamcinolone were equivalent to the control ointment, but high-potency (class IV) steroid ointments produced significant improvement in symptoms (by a mean of 1.07 points vs the control ointment; supporting statistics not given).

A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention identified 4 “good-quality” RCTs that evaluated effective remedies for nickel-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a predominantly female Caucasian population.3 All found that moderately high-potency topical steroid therapy improved symptoms, but heterogeneity among the studies made it impossible to determine the best agent.

Topical immunomodulatory drugs and jewelweed are no help

In a double-blinded RCT of 12 adults with a history of Rhus dermatitis and a significant reaction to tincture of poison ivy, topical pimecrolimus didn’t improve the duration or severity of symptoms (P=nonsignificant).4

A similar RCT from a dermatology clinic of 10 adults with confirmed sensitivity to poison oak or ivy found that topical jewelweed extract didn’t improve symptoms of artificially induced Rhus dermatitis. Investigators didn’t report P values.5

Oral steroids haven’t been studied

No studies have evaluated the effectiveness of oral steroids for Rhus dermatitis. Expert opinion recommends prednisone (60 mg daily, tapered over 14 days) for severe and widespread cases of poison ivy dermatitis.6,7

Recommendations

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology jointly recommend topical corticosteroids as firstline treatment for localized allergic contact dermatitis. They advise giving systemic corticosteroids for lesions covering more than 20% of body surface area (for example, prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg per day for 5-7 days, then 50% of the dose for another 5-7 days).6

The American Academy of Dermatology hasn’t issued guidelines on plant-induced dermatitis.

A dermatology textbook states that topical steroids are effective during the early stages of an outbreak, when vesicles and blisters aren’t yet present, and that systemic steroids are extremely effective for severe outbreaks. The authors recommend treating weepy lesions with tepid baths, wet to dry soaks, or calamine lotion to dry the lesions.7

1. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

2. Kaidbey KH, Kligman AM. Assay of topical corticosteroids: efficacy of suppression of experimental Rhus dermatitis in humans. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:808-813.

3. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

4. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

5. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/ oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermatol. 1997;8:150-153.

6. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(suppl 2):S1-S38.

7. Habif TP. Contact dermatitis and patch testing. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2010:130-153.

IT’S UNCLEAR which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

It’s unclear which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Two prospective, self-controlled cohort studies (N=30) showed that high-potency topical steroids improved symptoms associated with artificially induced Rhus dermatitis in a group with a history of that type of dermatitis.

The first study found that 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment applied twice a day significantly reduced overall vesiculation, erythema, induration, and pruritus compared with the control (P<.05, .01, .01, and .05, respectively).1 Investigators evaluated erythema, induration, and pruritus on a scale of 0 to 3 (absent, mild, moderate, or severe) and graded vesiculation on a similar 0- to 3-point scale (a frank bulla was graded 3). They started treatment at 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure and followed patients for 14 days. The greatest difference in mean scores—a reduction in vesiculation scores of approximately 1 point—occurred between 2 and 7 days of therapy.

The second study compared improvement in symptoms of Rhus dermatitis with daily application of topical steroids of different potencies and a control ointment.2 Investigators evaluated healing using a 0- to 4-point scale (0=clearing and 4=marked edema, erythema, and vesiculation). They found that lower-potency topical steroids such as 1% hydrocortisone and 0.1% triamcinolone were equivalent to the control ointment, but high-potency (class IV) steroid ointments produced significant improvement in symptoms (by a mean of 1.07 points vs the control ointment; supporting statistics not given).

A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention identified 4 “good-quality” RCTs that evaluated effective remedies for nickel-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a predominantly female Caucasian population.3 All found that moderately high-potency topical steroid therapy improved symptoms, but heterogeneity among the studies made it impossible to determine the best agent.

Topical immunomodulatory drugs and jewelweed are no help

In a double-blinded RCT of 12 adults with a history of Rhus dermatitis and a significant reaction to tincture of poison ivy, topical pimecrolimus didn’t improve the duration or severity of symptoms (P=nonsignificant).4

A similar RCT from a dermatology clinic of 10 adults with confirmed sensitivity to poison oak or ivy found that topical jewelweed extract didn’t improve symptoms of artificially induced Rhus dermatitis. Investigators didn’t report P values.5

Oral steroids haven’t been studied

No studies have evaluated the effectiveness of oral steroids for Rhus dermatitis. Expert opinion recommends prednisone (60 mg daily, tapered over 14 days) for severe and widespread cases of poison ivy dermatitis.6,7

Recommendations

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology jointly recommend topical corticosteroids as firstline treatment for localized allergic contact dermatitis. They advise giving systemic corticosteroids for lesions covering more than 20% of body surface area (for example, prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg per day for 5-7 days, then 50% of the dose for another 5-7 days).6

The American Academy of Dermatology hasn’t issued guidelines on plant-induced dermatitis.

A dermatology textbook states that topical steroids are effective during the early stages of an outbreak, when vesicles and blisters aren’t yet present, and that systemic steroids are extremely effective for severe outbreaks. The authors recommend treating weepy lesions with tepid baths, wet to dry soaks, or calamine lotion to dry the lesions.7

IT’S UNCLEAR which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

It’s unclear which treatment is best, because there have been no head-to-head comparisons of treatments for Rhus (plant-induced) contact dermatitis. That said, topical high-potency steroids slightly improve pruritus and the appearance of the rash (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small cohort studies).

Neither topical pimecrolimus (an immunomodulatory drug) nor jewelweed extract are helpful (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Oral steroids improve symptoms in severe cases (SOR: C, expert opinion).

Evidence summary

Two prospective, self-controlled cohort studies (N=30) showed that high-potency topical steroids improved symptoms associated with artificially induced Rhus dermatitis in a group with a history of that type of dermatitis.

The first study found that 0.05% clobetasol propionate ointment applied twice a day significantly reduced overall vesiculation, erythema, induration, and pruritus compared with the control (P<.05, .01, .01, and .05, respectively).1 Investigators evaluated erythema, induration, and pruritus on a scale of 0 to 3 (absent, mild, moderate, or severe) and graded vesiculation on a similar 0- to 3-point scale (a frank bulla was graded 3). They started treatment at 12, 24, and 48 hours after exposure and followed patients for 14 days. The greatest difference in mean scores—a reduction in vesiculation scores of approximately 1 point—occurred between 2 and 7 days of therapy.

The second study compared improvement in symptoms of Rhus dermatitis with daily application of topical steroids of different potencies and a control ointment.2 Investigators evaluated healing using a 0- to 4-point scale (0=clearing and 4=marked edema, erythema, and vesiculation). They found that lower-potency topical steroids such as 1% hydrocortisone and 0.1% triamcinolone were equivalent to the control ointment, but high-potency (class IV) steroid ointments produced significant improvement in symptoms (by a mean of 1.07 points vs the control ointment; supporting statistics not given).

A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention identified 4 “good-quality” RCTs that evaluated effective remedies for nickel-induced allergic contact dermatitis in a predominantly female Caucasian population.3 All found that moderately high-potency topical steroid therapy improved symptoms, but heterogeneity among the studies made it impossible to determine the best agent.

Topical immunomodulatory drugs and jewelweed are no help

In a double-blinded RCT of 12 adults with a history of Rhus dermatitis and a significant reaction to tincture of poison ivy, topical pimecrolimus didn’t improve the duration or severity of symptoms (P=nonsignificant).4

A similar RCT from a dermatology clinic of 10 adults with confirmed sensitivity to poison oak or ivy found that topical jewelweed extract didn’t improve symptoms of artificially induced Rhus dermatitis. Investigators didn’t report P values.5

Oral steroids haven’t been studied

No studies have evaluated the effectiveness of oral steroids for Rhus dermatitis. Expert opinion recommends prednisone (60 mg daily, tapered over 14 days) for severe and widespread cases of poison ivy dermatitis.6,7

Recommendations

The American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology and the American College of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology jointly recommend topical corticosteroids as firstline treatment for localized allergic contact dermatitis. They advise giving systemic corticosteroids for lesions covering more than 20% of body surface area (for example, prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg per day for 5-7 days, then 50% of the dose for another 5-7 days).6

The American Academy of Dermatology hasn’t issued guidelines on plant-induced dermatitis.

A dermatology textbook states that topical steroids are effective during the early stages of an outbreak, when vesicles and blisters aren’t yet present, and that systemic steroids are extremely effective for severe outbreaks. The authors recommend treating weepy lesions with tepid baths, wet to dry soaks, or calamine lotion to dry the lesions.7

1. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

2. Kaidbey KH, Kligman AM. Assay of topical corticosteroids: efficacy of suppression of experimental Rhus dermatitis in humans. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:808-813.

3. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

4. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

5. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/ oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermatol. 1997;8:150-153.

6. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(suppl 2):S1-S38.

7. Habif TP. Contact dermatitis and patch testing. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2010:130-153.

1. Vernon HJ, Olsen EA. A controlled trial of clobetasol propionate ointment 0.05% in the treatment of experimentally induced Rhus dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23:829-832.

2. Kaidbey KH, Kligman AM. Assay of topical corticosteroids: efficacy of suppression of experimental Rhus dermatitis in humans. Arch Dermatol. 1976;112:808-813.

3. Saary J, Qureshi R, Palda V, et al. A systematic review of contact dermatitis treatment and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:845.

4. Amrol D, Keitel D, Hagaman D, et al. Topical pimecrolimus in the treatment of human allergic contact dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2003;91:563-566.

5. Long D, Ballentine NH, Marks JG Jr. Treatment of poison ivy/ oak allergic contact dermatitis with an extract of jewelweed. Am J Contact Dermatol. 1997;8:150-153.

6. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology; American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Contact dermatitis: a practice parameter. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2006;97(suppl 2):S1-S38.

7. Habif TP. Contact dermatitis and patch testing. In: Habif TP. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy. 5th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2010:130-153.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network