User login

Assessing the Quality of VA Animal Care and Use Programs

Institutions conducting research involving animals have established operational frameworks, referred to as animal care and use programs (ACUPs), to ensure research animal welfare and high-quality research data and to meet ethical and regulatory requirements.1-4 The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) is a critical component of the ACUP and is responsible for the oversight and evaluation of all aspects of the ACUP.5 However, investigators, IACUCs, institutions, the research sponsor, and the federal government share responsibilities for ensuring research animal welfare.

Effective policies, procedures, practices, and systems in the ACUP are critical to an institution’s ability to ensure that animal research is conducted humanely and complies with applicable regulations, policies, and guidelines. To this end, considerable effort and resources have been devoted to improve the effectiveness of ACUPs, including external accreditation of ACUPs by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) and implementation of science-based performance standards, postapproval monitoring, and risk assessments and mitigation of identified vulnerability.6-9 However, the impact of these quality improvement measures remains unclear. There have been no valid, reliable, and quantifiable measures to assess the effectiveness and quality of ACUPs.

Compliance with federal regulations is not only required, but also essential in protecting laboratory animals. However, the goal is not to ensure compliance but to prevent unnecessary harm, injury, and suffering to those research animals. Overemphasis on compliance and documentation may negatively impact the system by diverting resources away from ensuring research animal welfare. The authors propose that although research animal welfare cannot be directly measured, it is possible to assess the quality of ACUPs. High-quality ACUPs are expected to minimize risk to research animals to the extent possible while maintaining the integrity of the research.

The authors previously developed a set of quality indicators (QIs) for human research protection programs (HRPPs) at the VA, emphasizing performance outcomes built on a foundation of compliance.10 Implementation of these QIs allowed the research team to collect data to assess the quality of VA HRPPs.11 It also allowed the team to answer important questions, such as whether there were significant differences in the quality of HRPPs among facilities using their own institutional review boards (IRBs) and those using affiliated university IRBs as their IRBs of record.12

Background

The VA health care system (VAHCS) is the largest integrated health care system in the U.S. Currently, there are 77 VA facilities conducting research involving laboratory animals. In addition to federal regulations governing research with animals, researchers in the VAHCS must comply with requirements established by VA.1-4 For example, in the VAHCS, the IACUC is a subcommittee of the Research and Development Committee (R&DC). Research involving animals may not be initiated until it has been approved by both the IACUC and the R&DC.13,14 All investigators, including animal research investigators, are required to have approved scopes of practice.14 Furthermore, all VA facilities that conduct animal research are required to have their ACUPs accredited by the AAALAC International.13

Based on the experience gained from the VA HRPP QIs, the authors developed a set of QIs that emphasize assessing the outcome of ACUPs rather than solely on IACUC review or compliance with animal research regulations and policies. This report describes the proposed QIs for assessing the quality of VA ACUPs and presents preliminary data using some of these QIs.

Methods

The VA ACUP QIs were developed through a process that included (1) identification of a set of potential indicators by the authors; (2) review and comments on the potential indicators by individuals within and outside VA who have expertise in protecting research animal welfare, including veterinarians with board certification in laboratory animal medicine, IACUC chairs, and individuals involved in the accreditation and oversight of ACUPs; and (3) review and revision by the authors of the proposed QIs in light of the suggestions and comments received. After 6 months of deliberation, a set of 13 QIs was finalized for consideration for implementation.

Data Collection

As part of the VA ACUP quality assurance program, each VA research facility is required to conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years by qualified research compliance officers (RCOs).15 Audit tools were developed for the triennial animal protocol regulatory audits (available at http://www.va.gov/oro/rcep.asp).11,12 Facility RCOs were then trained to use these tools to conduct audits throughout the year.

Results of the protocol regulatory audits, conducted between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, were collected through a Web-based system from all 74 VA facilities conducting animal research during that period. Information collected included IACUC and R&DC initial approval of human research protocols; for-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols; compliance with continuing review requirements; research personnel scopes of practice; and investigator animal research protection training requirements.

Because this study did not involve the use of laboratory animals, no ACUC review and approval was required.

Data Analysis

All data collected were entered into a database for analysis. When necessary, facilities were contacted to verify the accuracy and uniformity of data reported. Only descriptive statistics were obtained and presented.

Quality Indicators

As shown in the Box, a total of 13 QIs covering a broad range of areas that may have significant impact on research animal welfare were selected.

QI 1. ACUP accreditation status was chosen, because accreditation of an institutional ACUP by AAALAC International, the sole widely accepted ACUP accrediting organization, suggests that the institution establish acceptable operational frameworks to ensure research animal welfare. Because VA policy requires that all facilities conducting animal research be accredited, failure to achieve full accreditation may indicate that research animals are at an elevated risk due to a less than optimal system to protect research animals.13

QI 2. IACUC and R&DC initial approval of animal research protocols was chosen because of the importance of IACUC and R&DC review and approval in ensuring the scientific merit of the research and the adequacy of research animal protection. The number and the percentage of protocols conducted without or initiated prior to IACUC and/or R&DC approval, which may put animals at risk, is a good measure of the adequacy of the institution’s ACUP.

QI 3. For-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols was chosen, because this is a serious event. Protocols can be suspended or prematurely terminated by IACUCs due to investigators’ serious or continuing noncompliance or due to serious adverse events/injuries to the animals or research personnel. The number and percentage of protocols suspended reflect the adequacy of the IACUC oversight of the institution’s animal research program.

QI 4. Investigator sanction was chosen, because investigators and research personnel play an important role in protecting research animals. The number and percentage of investigators or technicians whose research privileges were suspended due to noncompliance reflect the adequacy of the institution’s education and training program as well as oversight of the ACUP.

QI 5. Annual review requirement was chosen because of the importance of ongoing oversight of approved animal research by the IACUC. The number and percentage of protocols lapsed in annual reviews, particularly when research activities continued during the lapse reflects the adequacy of IACUC oversight.

QI 6. Unanticipated loss of animal lives was chosen, because loss of animal lives is the most serious harm to animals that the ACUP is intended to prevent. The number and percentage of animals whose lives are unnecessarily lost due to heating, ventilation, or air-conditioning failure reflect the adequacy of the institution’s animal care infrastructure and effectiveness of the emergency response plan.

QI 7. Serious or continuing noncompliance resulting in actual harm to animals was chosen, because actual harm to animals is an important outcome measure of the adequacy of ACUP. The number and percentage of animals harmed due to investigator noncompliance or inadequate care reflect the adequacy of the institution’s veterinarian and IACUC oversight.

QI 8. Semi-annual program review and facility inspection was chosen because of the importance of semi-annual program review and facility inspection in IACUC’s oversight of the institution’s ACUP. This QI emphasizes the timely correction and remediation of both major and minor deficiencies identified during semi-annual program reviews and facility inspections. Failure to promptly address identified deficiencies in a timely manner may place research animals at significant risk.

QI 9. Scope of practice was chosen because of the importance of the investigator’s qualification in ensuring not only high-quality research data, but also adequate protection of research animals. Certain animal procedures can be safely performed only by investigators with adequate training and experience. Allowing investigators who are unqualified to perform these procedures places animals at significant risk of being harmed.

QI 10. Work- or research-related injuries was chosen because of the importance of the safety of investigators and animal caretakers in the institution’s ACUP. The importance of the institution’s occupational health and safety program in protecting investigators and animal care workers cannot be overemphasized. The number and percentage of investigators and animal care workers covered by the occupational health and safety program and work- or research-related injuries reflect the adequacy of the ACUP.

QI 11. Investigator animal care and use education/training requirements was chosen because of the important role of investigators in protecting animal welfare. The number and percentage of investigators who fail to maintain required animal care and use education/training reflect the adequacy of the institution’s IACUC oversight.

QI 12. IACUC chair and members’ animal care and use education and training requirements was chosen because of the important role of the IACUC chair and members in the institution’s ACUP. To appropriately evaluate and approve/disapprove animal research protocols, the chair and members of IACUC must maintain sufficient knowledge of federal regulations and VA policies regarding animal protections.

QI 13. Veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff qualification was chosen because of the important role of veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff in the day-to-day care of research animals and the specialized knowledge and qualification they need to maintain the animal research facilities. The number of veterinarians and nonveterinary animal care staff with appropriate board certifications reflects the strength of an institution’s ACUP.

Results

Recognizing the importance of assessing the quality of VA ACUPs, the authors started to collect some QI data of VA ACUPs parallel to those of VA HRPPs before the aforementioned proposed QIs for VA ACUPs were fully developed. These preliminary data are included here to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing these proposed VA ACUP QIs.

IACUC and R&DC Approvals (QI 2)

VA policies require that all animal research protocols be reviewed and approved first by the IACUC and then by the R&DC.13,14 The IACUC is a subcommittee of the R&DC. No animal research activities in VA may be initiated before receiving both IACUC and R&DC approval.13,14

Between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, regulatory audits were conducted on 1,286 animal research protocols. Among them, 1 (0.08%) protocol was conducted and completed without the required IACUC approval, 1 (0.08%) was conducted and completed without the required R&DC approval, 1 (0.08%) was initiated prior to IACUC approval, and 2 (0.16%) were initiated prior to R&DC approval.

For-Cause Suspension or Termination (QI 3)

Among the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 14 (1.09%) protocols were suspended or terminated for cause; 10 (0.78%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to animal safety concerns; and 4 (0.31%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to investigator-related concerns.

Lapse in Continuing Reviews (QI 5)

Federal regulations and VA policies require that IACUC conduct continuing review of all animal research protocols annually.2,13 Of the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 1,159 protocols required IACUC continuing reviews during the auditing period. Fifty-three protocols (4.57%) lapsed in IACUC annual reviews, and in 25 of these 53 protocols, investigators continued research activities during the lapse.

Scope of Practice (QI 9)

VA policies require all research personnel to have an approved research scope of practice or functional statement that defines the duties that the individual is qualified and allowed to perform for research purposes.14

A total of 4,604 research personnel records were reviewed from the 1,286 animal research protocols audited. Of these, 276 (5.99%) did not have an approved research scope of practice; 1 (0.02%) had an approved research scope of practice but was working outside the approved research scope of practice.

Training Requirements (QI 11)

VA policies require that all research personnel who participate in animal research complete initial and annual training to ensure that they can competently and humanely perform their duties related to animal research.14

Among the 4,604 animal research personnel records reviewed, 186 (4.04%) did not maintain their training requirements, including 26 (0.56%) without required initial training and 160 (3.48%) with lapses in required continuing training.

Discussion

Collectively, these proposed QIs should provide useful information about the overall quality of an ACUP. This allows semiquantitative assessment of the quality and performance of VA facilities’ ACUPs over time and comparison of the performance of ACUPs across research facilities in the VAHCS. The information obtained may also help administrators identify program vulnerabilities and make management decisions regarding where improvements are most needed. Specifically, QI data will be collected from all VA research facilities’ ACUPs annually. National averages for all QIs will be calculated. Each facility will then be provided with the results of its own ACUP QI data as well as the national averages, allowing the facility to compare its QI data with the national averages and determine how its ACUP performs compared with the overall VA ACUP performance.

These QIs were designed for use in assessing the quality of ACUPs at VA research facilities annually or at least once every other year. With the recent requirement that a full-time RCO at each VA research facility conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years, it is feasible that an assessment of the VA ACUPs using these QIs could be conducted annually as demonstrated by the preliminary data for QIs 2, 3, 5, 9, and 11 reported here.15,16 These preliminary data also showed high rates of lapses in IACUC continuing review (4.57%), lack of research personnel scopes of practice (5.99%), and noncompliance with training requirements (4.04%). These are areas that need improvements.

The size and complexity of animal research programs are different among different facilities, which can make it difficult to compare different facilities’ ACUPs using the same quality measures. In addition, VA facilities may use their own IACUCs or the affiliate university IACUCs as the IACUCs of record. However, based on the authors’ experience using HRPP QIs to assess the quality of VA HRPPs, the collected data using ACUP QIs will help determine whether such variables as the size and complexity of a program or the kind of IACUCs used (either VA, own IACUC, or affiliate IACUC) affect the quality of VA ACUPs.10-12

Limitations

There is no evidence proving that these QIs are the most optimal measures for evaluating the quality of a VA facility’s ACUP. It is also unknown whether these QIs correlate directly with the protection of research animals. Furthermore, a quantitative, numerical value cannot be put on each indicator to allow evaluators to rank facilities’ ACUPs.

Some QIs, such as QIs 3, 4, 7, and 8, may depend on how stringent an IACUC is. For example, it is possible that a conscientious IACUC may report more noncompliance or suspend more protocols, giving the appearance of a poor quality ACUP, whereas in fact it might be an excellent program. However, the authors want to emphasize that no single QI by itself is sufficient to assess the quality of a program. It is the combination of various QIs that provides information about the overall quality of a program. It is also through the data collected that the usefulness of any particular indicators may be determined.

Conclusion

These proposed QIs provide a useful first step toward developing a robust and valid assessment of VA ACUPs. As these QIs are used at VA facilities, they will likely be redefined and modified. The authors hope that other institutions will find these indicators useful as they develop instruments to assess their own ACUPs.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Bayne, Global Director, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, for her suggestions and comments during the development of these quality indicators and critical review of the manuscript, and Dr. J. Thomas Puglisi, Chief Officer, VA Office of Research Oversight, for his support and critical review of the manuscript.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Animal Welfare Act, 7 USC §2131-2156 (2008).

2. Animal Welfare Regulations, 9 CFR §1-4 (2008).

3. National Research Council of the National Academies. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Public Health Service Policy On Humane Care And Use Of Laboratory Animals. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. NIH publication 15-8013. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw//PHSPolicyLabAnimals.pdf. Revised 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

5. Sandgren EP. Defining the animal care and use program. Lab Anim (NY). 2005;34(10):41-44.

6. Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The AAALAC International accreditation program. The Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International Website. http://www.aaalac.org/accreditation/index.cfm. Updated 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

7. Klein HJ, Bayne KA. Establishing a culture of care, conscience, and responsibility: addressing the improvement of scientific discovery and animal welfare through science-based performance standards. ILAR J. 2007;48(1):3-11.

8. Banks RE, Norton JN. A sample postapproval monitoring program in academia. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):402-418.

9. Van Sluyters RC. A guide to risk assessment in animal care and use programs: the metaphor of the 3-legged stool. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):372-378.

10. Tsan MF, Smith K, Gao B. Assessing the quality of human research protection programs: the experience at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2010;32(4):16-19.

11. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks R. Using quality indicators to assess human research protection programs at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2013;35(1):10-14.

12. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks B. Assessing the quality of VA Human Research Protection Programs: VA vs. affiliated University Institutional Review Board. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics. 2013;8(2):153-160.

13. VA Research and Development Service. Use of Animals in Research. VHA Handbook 1200.07. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2011.

14. VA Research and Development Service. Research and Development (R&D) Committee. VHA Handbook 1200.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2009.

15. Research Compliance Officers and the Auditing of VHA Human Subjects Research to Determine Compliance with Applicable Laws, Regulations, and Policies. VHA Directive 2008-064. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2008.

16. VA Office of Research Oversight. Research Compliance Reporting Requirements. VHA Handbook 1058.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2015.

Institutions conducting research involving animals have established operational frameworks, referred to as animal care and use programs (ACUPs), to ensure research animal welfare and high-quality research data and to meet ethical and regulatory requirements.1-4 The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) is a critical component of the ACUP and is responsible for the oversight and evaluation of all aspects of the ACUP.5 However, investigators, IACUCs, institutions, the research sponsor, and the federal government share responsibilities for ensuring research animal welfare.

Effective policies, procedures, practices, and systems in the ACUP are critical to an institution’s ability to ensure that animal research is conducted humanely and complies with applicable regulations, policies, and guidelines. To this end, considerable effort and resources have been devoted to improve the effectiveness of ACUPs, including external accreditation of ACUPs by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) and implementation of science-based performance standards, postapproval monitoring, and risk assessments and mitigation of identified vulnerability.6-9 However, the impact of these quality improvement measures remains unclear. There have been no valid, reliable, and quantifiable measures to assess the effectiveness and quality of ACUPs.

Compliance with federal regulations is not only required, but also essential in protecting laboratory animals. However, the goal is not to ensure compliance but to prevent unnecessary harm, injury, and suffering to those research animals. Overemphasis on compliance and documentation may negatively impact the system by diverting resources away from ensuring research animal welfare. The authors propose that although research animal welfare cannot be directly measured, it is possible to assess the quality of ACUPs. High-quality ACUPs are expected to minimize risk to research animals to the extent possible while maintaining the integrity of the research.

The authors previously developed a set of quality indicators (QIs) for human research protection programs (HRPPs) at the VA, emphasizing performance outcomes built on a foundation of compliance.10 Implementation of these QIs allowed the research team to collect data to assess the quality of VA HRPPs.11 It also allowed the team to answer important questions, such as whether there were significant differences in the quality of HRPPs among facilities using their own institutional review boards (IRBs) and those using affiliated university IRBs as their IRBs of record.12

Background

The VA health care system (VAHCS) is the largest integrated health care system in the U.S. Currently, there are 77 VA facilities conducting research involving laboratory animals. In addition to federal regulations governing research with animals, researchers in the VAHCS must comply with requirements established by VA.1-4 For example, in the VAHCS, the IACUC is a subcommittee of the Research and Development Committee (R&DC). Research involving animals may not be initiated until it has been approved by both the IACUC and the R&DC.13,14 All investigators, including animal research investigators, are required to have approved scopes of practice.14 Furthermore, all VA facilities that conduct animal research are required to have their ACUPs accredited by the AAALAC International.13

Based on the experience gained from the VA HRPP QIs, the authors developed a set of QIs that emphasize assessing the outcome of ACUPs rather than solely on IACUC review or compliance with animal research regulations and policies. This report describes the proposed QIs for assessing the quality of VA ACUPs and presents preliminary data using some of these QIs.

Methods

The VA ACUP QIs were developed through a process that included (1) identification of a set of potential indicators by the authors; (2) review and comments on the potential indicators by individuals within and outside VA who have expertise in protecting research animal welfare, including veterinarians with board certification in laboratory animal medicine, IACUC chairs, and individuals involved in the accreditation and oversight of ACUPs; and (3) review and revision by the authors of the proposed QIs in light of the suggestions and comments received. After 6 months of deliberation, a set of 13 QIs was finalized for consideration for implementation.

Data Collection

As part of the VA ACUP quality assurance program, each VA research facility is required to conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years by qualified research compliance officers (RCOs).15 Audit tools were developed for the triennial animal protocol regulatory audits (available at http://www.va.gov/oro/rcep.asp).11,12 Facility RCOs were then trained to use these tools to conduct audits throughout the year.

Results of the protocol regulatory audits, conducted between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, were collected through a Web-based system from all 74 VA facilities conducting animal research during that period. Information collected included IACUC and R&DC initial approval of human research protocols; for-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols; compliance with continuing review requirements; research personnel scopes of practice; and investigator animal research protection training requirements.

Because this study did not involve the use of laboratory animals, no ACUC review and approval was required.

Data Analysis

All data collected were entered into a database for analysis. When necessary, facilities were contacted to verify the accuracy and uniformity of data reported. Only descriptive statistics were obtained and presented.

Quality Indicators

As shown in the Box, a total of 13 QIs covering a broad range of areas that may have significant impact on research animal welfare were selected.

QI 1. ACUP accreditation status was chosen, because accreditation of an institutional ACUP by AAALAC International, the sole widely accepted ACUP accrediting organization, suggests that the institution establish acceptable operational frameworks to ensure research animal welfare. Because VA policy requires that all facilities conducting animal research be accredited, failure to achieve full accreditation may indicate that research animals are at an elevated risk due to a less than optimal system to protect research animals.13

QI 2. IACUC and R&DC initial approval of animal research protocols was chosen because of the importance of IACUC and R&DC review and approval in ensuring the scientific merit of the research and the adequacy of research animal protection. The number and the percentage of protocols conducted without or initiated prior to IACUC and/or R&DC approval, which may put animals at risk, is a good measure of the adequacy of the institution’s ACUP.

QI 3. For-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols was chosen, because this is a serious event. Protocols can be suspended or prematurely terminated by IACUCs due to investigators’ serious or continuing noncompliance or due to serious adverse events/injuries to the animals or research personnel. The number and percentage of protocols suspended reflect the adequacy of the IACUC oversight of the institution’s animal research program.

QI 4. Investigator sanction was chosen, because investigators and research personnel play an important role in protecting research animals. The number and percentage of investigators or technicians whose research privileges were suspended due to noncompliance reflect the adequacy of the institution’s education and training program as well as oversight of the ACUP.

QI 5. Annual review requirement was chosen because of the importance of ongoing oversight of approved animal research by the IACUC. The number and percentage of protocols lapsed in annual reviews, particularly when research activities continued during the lapse reflects the adequacy of IACUC oversight.

QI 6. Unanticipated loss of animal lives was chosen, because loss of animal lives is the most serious harm to animals that the ACUP is intended to prevent. The number and percentage of animals whose lives are unnecessarily lost due to heating, ventilation, or air-conditioning failure reflect the adequacy of the institution’s animal care infrastructure and effectiveness of the emergency response plan.

QI 7. Serious or continuing noncompliance resulting in actual harm to animals was chosen, because actual harm to animals is an important outcome measure of the adequacy of ACUP. The number and percentage of animals harmed due to investigator noncompliance or inadequate care reflect the adequacy of the institution’s veterinarian and IACUC oversight.

QI 8. Semi-annual program review and facility inspection was chosen because of the importance of semi-annual program review and facility inspection in IACUC’s oversight of the institution’s ACUP. This QI emphasizes the timely correction and remediation of both major and minor deficiencies identified during semi-annual program reviews and facility inspections. Failure to promptly address identified deficiencies in a timely manner may place research animals at significant risk.

QI 9. Scope of practice was chosen because of the importance of the investigator’s qualification in ensuring not only high-quality research data, but also adequate protection of research animals. Certain animal procedures can be safely performed only by investigators with adequate training and experience. Allowing investigators who are unqualified to perform these procedures places animals at significant risk of being harmed.

QI 10. Work- or research-related injuries was chosen because of the importance of the safety of investigators and animal caretakers in the institution’s ACUP. The importance of the institution’s occupational health and safety program in protecting investigators and animal care workers cannot be overemphasized. The number and percentage of investigators and animal care workers covered by the occupational health and safety program and work- or research-related injuries reflect the adequacy of the ACUP.

QI 11. Investigator animal care and use education/training requirements was chosen because of the important role of investigators in protecting animal welfare. The number and percentage of investigators who fail to maintain required animal care and use education/training reflect the adequacy of the institution’s IACUC oversight.

QI 12. IACUC chair and members’ animal care and use education and training requirements was chosen because of the important role of the IACUC chair and members in the institution’s ACUP. To appropriately evaluate and approve/disapprove animal research protocols, the chair and members of IACUC must maintain sufficient knowledge of federal regulations and VA policies regarding animal protections.

QI 13. Veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff qualification was chosen because of the important role of veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff in the day-to-day care of research animals and the specialized knowledge and qualification they need to maintain the animal research facilities. The number of veterinarians and nonveterinary animal care staff with appropriate board certifications reflects the strength of an institution’s ACUP.

Results

Recognizing the importance of assessing the quality of VA ACUPs, the authors started to collect some QI data of VA ACUPs parallel to those of VA HRPPs before the aforementioned proposed QIs for VA ACUPs were fully developed. These preliminary data are included here to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing these proposed VA ACUP QIs.

IACUC and R&DC Approvals (QI 2)

VA policies require that all animal research protocols be reviewed and approved first by the IACUC and then by the R&DC.13,14 The IACUC is a subcommittee of the R&DC. No animal research activities in VA may be initiated before receiving both IACUC and R&DC approval.13,14

Between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, regulatory audits were conducted on 1,286 animal research protocols. Among them, 1 (0.08%) protocol was conducted and completed without the required IACUC approval, 1 (0.08%) was conducted and completed without the required R&DC approval, 1 (0.08%) was initiated prior to IACUC approval, and 2 (0.16%) were initiated prior to R&DC approval.

For-Cause Suspension or Termination (QI 3)

Among the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 14 (1.09%) protocols were suspended or terminated for cause; 10 (0.78%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to animal safety concerns; and 4 (0.31%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to investigator-related concerns.

Lapse in Continuing Reviews (QI 5)

Federal regulations and VA policies require that IACUC conduct continuing review of all animal research protocols annually.2,13 Of the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 1,159 protocols required IACUC continuing reviews during the auditing period. Fifty-three protocols (4.57%) lapsed in IACUC annual reviews, and in 25 of these 53 protocols, investigators continued research activities during the lapse.

Scope of Practice (QI 9)

VA policies require all research personnel to have an approved research scope of practice or functional statement that defines the duties that the individual is qualified and allowed to perform for research purposes.14

A total of 4,604 research personnel records were reviewed from the 1,286 animal research protocols audited. Of these, 276 (5.99%) did not have an approved research scope of practice; 1 (0.02%) had an approved research scope of practice but was working outside the approved research scope of practice.

Training Requirements (QI 11)

VA policies require that all research personnel who participate in animal research complete initial and annual training to ensure that they can competently and humanely perform their duties related to animal research.14

Among the 4,604 animal research personnel records reviewed, 186 (4.04%) did not maintain their training requirements, including 26 (0.56%) without required initial training and 160 (3.48%) with lapses in required continuing training.

Discussion

Collectively, these proposed QIs should provide useful information about the overall quality of an ACUP. This allows semiquantitative assessment of the quality and performance of VA facilities’ ACUPs over time and comparison of the performance of ACUPs across research facilities in the VAHCS. The information obtained may also help administrators identify program vulnerabilities and make management decisions regarding where improvements are most needed. Specifically, QI data will be collected from all VA research facilities’ ACUPs annually. National averages for all QIs will be calculated. Each facility will then be provided with the results of its own ACUP QI data as well as the national averages, allowing the facility to compare its QI data with the national averages and determine how its ACUP performs compared with the overall VA ACUP performance.

These QIs were designed for use in assessing the quality of ACUPs at VA research facilities annually or at least once every other year. With the recent requirement that a full-time RCO at each VA research facility conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years, it is feasible that an assessment of the VA ACUPs using these QIs could be conducted annually as demonstrated by the preliminary data for QIs 2, 3, 5, 9, and 11 reported here.15,16 These preliminary data also showed high rates of lapses in IACUC continuing review (4.57%), lack of research personnel scopes of practice (5.99%), and noncompliance with training requirements (4.04%). These are areas that need improvements.

The size and complexity of animal research programs are different among different facilities, which can make it difficult to compare different facilities’ ACUPs using the same quality measures. In addition, VA facilities may use their own IACUCs or the affiliate university IACUCs as the IACUCs of record. However, based on the authors’ experience using HRPP QIs to assess the quality of VA HRPPs, the collected data using ACUP QIs will help determine whether such variables as the size and complexity of a program or the kind of IACUCs used (either VA, own IACUC, or affiliate IACUC) affect the quality of VA ACUPs.10-12

Limitations

There is no evidence proving that these QIs are the most optimal measures for evaluating the quality of a VA facility’s ACUP. It is also unknown whether these QIs correlate directly with the protection of research animals. Furthermore, a quantitative, numerical value cannot be put on each indicator to allow evaluators to rank facilities’ ACUPs.

Some QIs, such as QIs 3, 4, 7, and 8, may depend on how stringent an IACUC is. For example, it is possible that a conscientious IACUC may report more noncompliance or suspend more protocols, giving the appearance of a poor quality ACUP, whereas in fact it might be an excellent program. However, the authors want to emphasize that no single QI by itself is sufficient to assess the quality of a program. It is the combination of various QIs that provides information about the overall quality of a program. It is also through the data collected that the usefulness of any particular indicators may be determined.

Conclusion

These proposed QIs provide a useful first step toward developing a robust and valid assessment of VA ACUPs. As these QIs are used at VA facilities, they will likely be redefined and modified. The authors hope that other institutions will find these indicators useful as they develop instruments to assess their own ACUPs.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Bayne, Global Director, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, for her suggestions and comments during the development of these quality indicators and critical review of the manuscript, and Dr. J. Thomas Puglisi, Chief Officer, VA Office of Research Oversight, for his support and critical review of the manuscript.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Institutions conducting research involving animals have established operational frameworks, referred to as animal care and use programs (ACUPs), to ensure research animal welfare and high-quality research data and to meet ethical and regulatory requirements.1-4 The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) is a critical component of the ACUP and is responsible for the oversight and evaluation of all aspects of the ACUP.5 However, investigators, IACUCs, institutions, the research sponsor, and the federal government share responsibilities for ensuring research animal welfare.

Effective policies, procedures, practices, and systems in the ACUP are critical to an institution’s ability to ensure that animal research is conducted humanely and complies with applicable regulations, policies, and guidelines. To this end, considerable effort and resources have been devoted to improve the effectiveness of ACUPs, including external accreditation of ACUPs by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International) and implementation of science-based performance standards, postapproval monitoring, and risk assessments and mitigation of identified vulnerability.6-9 However, the impact of these quality improvement measures remains unclear. There have been no valid, reliable, and quantifiable measures to assess the effectiveness and quality of ACUPs.

Compliance with federal regulations is not only required, but also essential in protecting laboratory animals. However, the goal is not to ensure compliance but to prevent unnecessary harm, injury, and suffering to those research animals. Overemphasis on compliance and documentation may negatively impact the system by diverting resources away from ensuring research animal welfare. The authors propose that although research animal welfare cannot be directly measured, it is possible to assess the quality of ACUPs. High-quality ACUPs are expected to minimize risk to research animals to the extent possible while maintaining the integrity of the research.

The authors previously developed a set of quality indicators (QIs) for human research protection programs (HRPPs) at the VA, emphasizing performance outcomes built on a foundation of compliance.10 Implementation of these QIs allowed the research team to collect data to assess the quality of VA HRPPs.11 It also allowed the team to answer important questions, such as whether there were significant differences in the quality of HRPPs among facilities using their own institutional review boards (IRBs) and those using affiliated university IRBs as their IRBs of record.12

Background

The VA health care system (VAHCS) is the largest integrated health care system in the U.S. Currently, there are 77 VA facilities conducting research involving laboratory animals. In addition to federal regulations governing research with animals, researchers in the VAHCS must comply with requirements established by VA.1-4 For example, in the VAHCS, the IACUC is a subcommittee of the Research and Development Committee (R&DC). Research involving animals may not be initiated until it has been approved by both the IACUC and the R&DC.13,14 All investigators, including animal research investigators, are required to have approved scopes of practice.14 Furthermore, all VA facilities that conduct animal research are required to have their ACUPs accredited by the AAALAC International.13

Based on the experience gained from the VA HRPP QIs, the authors developed a set of QIs that emphasize assessing the outcome of ACUPs rather than solely on IACUC review or compliance with animal research regulations and policies. This report describes the proposed QIs for assessing the quality of VA ACUPs and presents preliminary data using some of these QIs.

Methods

The VA ACUP QIs were developed through a process that included (1) identification of a set of potential indicators by the authors; (2) review and comments on the potential indicators by individuals within and outside VA who have expertise in protecting research animal welfare, including veterinarians with board certification in laboratory animal medicine, IACUC chairs, and individuals involved in the accreditation and oversight of ACUPs; and (3) review and revision by the authors of the proposed QIs in light of the suggestions and comments received. After 6 months of deliberation, a set of 13 QIs was finalized for consideration for implementation.

Data Collection

As part of the VA ACUP quality assurance program, each VA research facility is required to conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years by qualified research compliance officers (RCOs).15 Audit tools were developed for the triennial animal protocol regulatory audits (available at http://www.va.gov/oro/rcep.asp).11,12 Facility RCOs were then trained to use these tools to conduct audits throughout the year.

Results of the protocol regulatory audits, conducted between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, were collected through a Web-based system from all 74 VA facilities conducting animal research during that period. Information collected included IACUC and R&DC initial approval of human research protocols; for-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols; compliance with continuing review requirements; research personnel scopes of practice; and investigator animal research protection training requirements.

Because this study did not involve the use of laboratory animals, no ACUC review and approval was required.

Data Analysis

All data collected were entered into a database for analysis. When necessary, facilities were contacted to verify the accuracy and uniformity of data reported. Only descriptive statistics were obtained and presented.

Quality Indicators

As shown in the Box, a total of 13 QIs covering a broad range of areas that may have significant impact on research animal welfare were selected.

QI 1. ACUP accreditation status was chosen, because accreditation of an institutional ACUP by AAALAC International, the sole widely accepted ACUP accrediting organization, suggests that the institution establish acceptable operational frameworks to ensure research animal welfare. Because VA policy requires that all facilities conducting animal research be accredited, failure to achieve full accreditation may indicate that research animals are at an elevated risk due to a less than optimal system to protect research animals.13

QI 2. IACUC and R&DC initial approval of animal research protocols was chosen because of the importance of IACUC and R&DC review and approval in ensuring the scientific merit of the research and the adequacy of research animal protection. The number and the percentage of protocols conducted without or initiated prior to IACUC and/or R&DC approval, which may put animals at risk, is a good measure of the adequacy of the institution’s ACUP.

QI 3. For-cause suspension or termination of animal research protocols was chosen, because this is a serious event. Protocols can be suspended or prematurely terminated by IACUCs due to investigators’ serious or continuing noncompliance or due to serious adverse events/injuries to the animals or research personnel. The number and percentage of protocols suspended reflect the adequacy of the IACUC oversight of the institution’s animal research program.

QI 4. Investigator sanction was chosen, because investigators and research personnel play an important role in protecting research animals. The number and percentage of investigators or technicians whose research privileges were suspended due to noncompliance reflect the adequacy of the institution’s education and training program as well as oversight of the ACUP.

QI 5. Annual review requirement was chosen because of the importance of ongoing oversight of approved animal research by the IACUC. The number and percentage of protocols lapsed in annual reviews, particularly when research activities continued during the lapse reflects the adequacy of IACUC oversight.

QI 6. Unanticipated loss of animal lives was chosen, because loss of animal lives is the most serious harm to animals that the ACUP is intended to prevent. The number and percentage of animals whose lives are unnecessarily lost due to heating, ventilation, or air-conditioning failure reflect the adequacy of the institution’s animal care infrastructure and effectiveness of the emergency response plan.

QI 7. Serious or continuing noncompliance resulting in actual harm to animals was chosen, because actual harm to animals is an important outcome measure of the adequacy of ACUP. The number and percentage of animals harmed due to investigator noncompliance or inadequate care reflect the adequacy of the institution’s veterinarian and IACUC oversight.

QI 8. Semi-annual program review and facility inspection was chosen because of the importance of semi-annual program review and facility inspection in IACUC’s oversight of the institution’s ACUP. This QI emphasizes the timely correction and remediation of both major and minor deficiencies identified during semi-annual program reviews and facility inspections. Failure to promptly address identified deficiencies in a timely manner may place research animals at significant risk.

QI 9. Scope of practice was chosen because of the importance of the investigator’s qualification in ensuring not only high-quality research data, but also adequate protection of research animals. Certain animal procedures can be safely performed only by investigators with adequate training and experience. Allowing investigators who are unqualified to perform these procedures places animals at significant risk of being harmed.

QI 10. Work- or research-related injuries was chosen because of the importance of the safety of investigators and animal caretakers in the institution’s ACUP. The importance of the institution’s occupational health and safety program in protecting investigators and animal care workers cannot be overemphasized. The number and percentage of investigators and animal care workers covered by the occupational health and safety program and work- or research-related injuries reflect the adequacy of the ACUP.

QI 11. Investigator animal care and use education/training requirements was chosen because of the important role of investigators in protecting animal welfare. The number and percentage of investigators who fail to maintain required animal care and use education/training reflect the adequacy of the institution’s IACUC oversight.

QI 12. IACUC chair and members’ animal care and use education and training requirements was chosen because of the important role of the IACUC chair and members in the institution’s ACUP. To appropriately evaluate and approve/disapprove animal research protocols, the chair and members of IACUC must maintain sufficient knowledge of federal regulations and VA policies regarding animal protections.

QI 13. Veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff qualification was chosen because of the important role of veterinarian and veterinary medical unit staff in the day-to-day care of research animals and the specialized knowledge and qualification they need to maintain the animal research facilities. The number of veterinarians and nonveterinary animal care staff with appropriate board certifications reflects the strength of an institution’s ACUP.

Results

Recognizing the importance of assessing the quality of VA ACUPs, the authors started to collect some QI data of VA ACUPs parallel to those of VA HRPPs before the aforementioned proposed QIs for VA ACUPs were fully developed. These preliminary data are included here to demonstrate the feasibility of implementing these proposed VA ACUP QIs.

IACUC and R&DC Approvals (QI 2)

VA policies require that all animal research protocols be reviewed and approved first by the IACUC and then by the R&DC.13,14 The IACUC is a subcommittee of the R&DC. No animal research activities in VA may be initiated before receiving both IACUC and R&DC approval.13,14

Between June 1, 2011, and May 31, 2012, regulatory audits were conducted on 1,286 animal research protocols. Among them, 1 (0.08%) protocol was conducted and completed without the required IACUC approval, 1 (0.08%) was conducted and completed without the required R&DC approval, 1 (0.08%) was initiated prior to IACUC approval, and 2 (0.16%) were initiated prior to R&DC approval.

For-Cause Suspension or Termination (QI 3)

Among the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 14 (1.09%) protocols were suspended or terminated for cause; 10 (0.78%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to animal safety concerns; and 4 (0.31%) protocols were suspended or terminated due to investigator-related concerns.

Lapse in Continuing Reviews (QI 5)

Federal regulations and VA policies require that IACUC conduct continuing review of all animal research protocols annually.2,13 Of the 1,286 animal research protocols audited, 1,159 protocols required IACUC continuing reviews during the auditing period. Fifty-three protocols (4.57%) lapsed in IACUC annual reviews, and in 25 of these 53 protocols, investigators continued research activities during the lapse.

Scope of Practice (QI 9)

VA policies require all research personnel to have an approved research scope of practice or functional statement that defines the duties that the individual is qualified and allowed to perform for research purposes.14

A total of 4,604 research personnel records were reviewed from the 1,286 animal research protocols audited. Of these, 276 (5.99%) did not have an approved research scope of practice; 1 (0.02%) had an approved research scope of practice but was working outside the approved research scope of practice.

Training Requirements (QI 11)

VA policies require that all research personnel who participate in animal research complete initial and annual training to ensure that they can competently and humanely perform their duties related to animal research.14

Among the 4,604 animal research personnel records reviewed, 186 (4.04%) did not maintain their training requirements, including 26 (0.56%) without required initial training and 160 (3.48%) with lapses in required continuing training.

Discussion

Collectively, these proposed QIs should provide useful information about the overall quality of an ACUP. This allows semiquantitative assessment of the quality and performance of VA facilities’ ACUPs over time and comparison of the performance of ACUPs across research facilities in the VAHCS. The information obtained may also help administrators identify program vulnerabilities and make management decisions regarding where improvements are most needed. Specifically, QI data will be collected from all VA research facilities’ ACUPs annually. National averages for all QIs will be calculated. Each facility will then be provided with the results of its own ACUP QI data as well as the national averages, allowing the facility to compare its QI data with the national averages and determine how its ACUP performs compared with the overall VA ACUP performance.

These QIs were designed for use in assessing the quality of ACUPs at VA research facilities annually or at least once every other year. With the recent requirement that a full-time RCO at each VA research facility conduct regulatory audits of all animal research protocols once every 3 years, it is feasible that an assessment of the VA ACUPs using these QIs could be conducted annually as demonstrated by the preliminary data for QIs 2, 3, 5, 9, and 11 reported here.15,16 These preliminary data also showed high rates of lapses in IACUC continuing review (4.57%), lack of research personnel scopes of practice (5.99%), and noncompliance with training requirements (4.04%). These are areas that need improvements.

The size and complexity of animal research programs are different among different facilities, which can make it difficult to compare different facilities’ ACUPs using the same quality measures. In addition, VA facilities may use their own IACUCs or the affiliate university IACUCs as the IACUCs of record. However, based on the authors’ experience using HRPP QIs to assess the quality of VA HRPPs, the collected data using ACUP QIs will help determine whether such variables as the size and complexity of a program or the kind of IACUCs used (either VA, own IACUC, or affiliate IACUC) affect the quality of VA ACUPs.10-12

Limitations

There is no evidence proving that these QIs are the most optimal measures for evaluating the quality of a VA facility’s ACUP. It is also unknown whether these QIs correlate directly with the protection of research animals. Furthermore, a quantitative, numerical value cannot be put on each indicator to allow evaluators to rank facilities’ ACUPs.

Some QIs, such as QIs 3, 4, 7, and 8, may depend on how stringent an IACUC is. For example, it is possible that a conscientious IACUC may report more noncompliance or suspend more protocols, giving the appearance of a poor quality ACUP, whereas in fact it might be an excellent program. However, the authors want to emphasize that no single QI by itself is sufficient to assess the quality of a program. It is the combination of various QIs that provides information about the overall quality of a program. It is also through the data collected that the usefulness of any particular indicators may be determined.

Conclusion

These proposed QIs provide a useful first step toward developing a robust and valid assessment of VA ACUPs. As these QIs are used at VA facilities, they will likely be redefined and modified. The authors hope that other institutions will find these indicators useful as they develop instruments to assess their own ACUPs.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Kathryn Bayne, Global Director, Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International, for her suggestions and comments during the development of these quality indicators and critical review of the manuscript, and Dr. J. Thomas Puglisi, Chief Officer, VA Office of Research Oversight, for his support and critical review of the manuscript.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Animal Welfare Act, 7 USC §2131-2156 (2008).

2. Animal Welfare Regulations, 9 CFR §1-4 (2008).

3. National Research Council of the National Academies. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Public Health Service Policy On Humane Care And Use Of Laboratory Animals. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. NIH publication 15-8013. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw//PHSPolicyLabAnimals.pdf. Revised 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

5. Sandgren EP. Defining the animal care and use program. Lab Anim (NY). 2005;34(10):41-44.

6. Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The AAALAC International accreditation program. The Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International Website. http://www.aaalac.org/accreditation/index.cfm. Updated 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

7. Klein HJ, Bayne KA. Establishing a culture of care, conscience, and responsibility: addressing the improvement of scientific discovery and animal welfare through science-based performance standards. ILAR J. 2007;48(1):3-11.

8. Banks RE, Norton JN. A sample postapproval monitoring program in academia. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):402-418.

9. Van Sluyters RC. A guide to risk assessment in animal care and use programs: the metaphor of the 3-legged stool. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):372-378.

10. Tsan MF, Smith K, Gao B. Assessing the quality of human research protection programs: the experience at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2010;32(4):16-19.

11. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks R. Using quality indicators to assess human research protection programs at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2013;35(1):10-14.

12. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks B. Assessing the quality of VA Human Research Protection Programs: VA vs. affiliated University Institutional Review Board. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics. 2013;8(2):153-160.

13. VA Research and Development Service. Use of Animals in Research. VHA Handbook 1200.07. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2011.

14. VA Research and Development Service. Research and Development (R&D) Committee. VHA Handbook 1200.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2009.

15. Research Compliance Officers and the Auditing of VHA Human Subjects Research to Determine Compliance with Applicable Laws, Regulations, and Policies. VHA Directive 2008-064. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2008.

16. VA Office of Research Oversight. Research Compliance Reporting Requirements. VHA Handbook 1058.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2015.

1. Animal Welfare Act, 7 USC §2131-2156 (2008).

2. Animal Welfare Regulations, 9 CFR §1-4 (2008).

3. National Research Council of the National Academies. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. 8th ed. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

4. Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. Public Health Service Policy On Humane Care And Use Of Laboratory Animals. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2015. NIH publication 15-8013. http://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw//PHSPolicyLabAnimals.pdf. Revised 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

5. Sandgren EP. Defining the animal care and use program. Lab Anim (NY). 2005;34(10):41-44.

6. Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. The AAALAC International accreditation program. The Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International Website. http://www.aaalac.org/accreditation/index.cfm. Updated 2015. Accessed August 3, 2015.

7. Klein HJ, Bayne KA. Establishing a culture of care, conscience, and responsibility: addressing the improvement of scientific discovery and animal welfare through science-based performance standards. ILAR J. 2007;48(1):3-11.

8. Banks RE, Norton JN. A sample postapproval monitoring program in academia. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):402-418.

9. Van Sluyters RC. A guide to risk assessment in animal care and use programs: the metaphor of the 3-legged stool. ILAR J. 2008;49(4):372-378.

10. Tsan MF, Smith K, Gao B. Assessing the quality of human research protection programs: the experience at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2010;32(4):16-19.

11. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks R. Using quality indicators to assess human research protection programs at the Department of Veterans Affairs. IRB. 2013;35(1):10-14.

12. Tsan MF, Nguyen Y, Brooks B. Assessing the quality of VA Human Research Protection Programs: VA vs. affiliated University Institutional Review Board. J Emp Res Hum Res Ethics. 2013;8(2):153-160.

13. VA Research and Development Service. Use of Animals in Research. VHA Handbook 1200.07. Washington, DC: Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration; 2011.

14. VA Research and Development Service. Research and Development (R&D) Committee. VHA Handbook 1200.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2009.

15. Research Compliance Officers and the Auditing of VHA Human Subjects Research to Determine Compliance with Applicable Laws, Regulations, and Policies. VHA Directive 2008-064. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2008.

16. VA Office of Research Oversight. Research Compliance Reporting Requirements. VHA Handbook 1058.01. Washington, DC: Veterans Health Administration; 2015.

Using Quality Indicators to Assess and Improve Human Research Protection Programs at the VA

Protection of human subjects participating in research is critically important during this era of rapid medical progress and the increasing emphasis on translating discoveries from basic science research into clinical practices. The Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects, also known as the Common Rule, was established based on the Belmont Report’s ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice.1,2 Under the Common Rule, institutional review boards (IRBs) are responsible for reviewing and approving human research protocols and providing oversight to ensure protection of human research subjects.1

In addition to IRBs, investigators, institutions, research volunteers, sponsors of research, and the federal government share responsibilities for protecting research subjects.3 Institutions conducting research involving human subjects have thus established operational frameworks, referred to as human research protection programs (HRPPs), to ensure the rights and welfare of research participants and to meet the ethical and regulatory requirements.3,4

Related: Empathic Disclosure of Adverse Events to Patients

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a number of major academic institutions’ federally supported research programs were suspended due to persistent noncompliance with federal regulations, including some issues that resulted in the death of healthy volunteers.5,6 In response to increased public scrutiny of clinical research, considerable efforts have been made to improve the protection of research subjects.5,7-9 These efforts included stronger federal oversight of research, voluntary accreditation of institutional HRPPs, increased institutional support for HRPPs, improved training for investigators and IRB members, improved monitoring and reporting of adverse events (AEs), and greater involvement of research participants and the public.9

Despite considerable investment to improve research subject protections, scant data exist showing that these efforts have made human research safer than before. Although research subject protection cannot be directly measured, quality assessment of HRPPs is possible. High-quality HRPPs are expected to minimize risk to research participants to the extent possible while maintaining the integrity of the research.10

Related: Improving Veteran Access to Clinical Trials

The VA health care system is the largest integrated health care system in the country. Currently, there are 107 VA facilities conducting research involving human subjects. In addition to federal regulations governing research with human subjects, VA researchers must also comply with requirements established by the VA. For example, in the VA the IRB is a subcommittee of the research and development committee (R&DC). Research involving human subjects may not be initiated until approved by both the IRB and the R&DC.4,11 All VA investigators are required to have approved research scopes of practice and training in ethical principles and current good clinical practices.4

Recently, the VA Office of Research Oversight (VAORO) developed a set of indicators for assessing the quality of VA HRPPs.10 Since 2010, VAORO has been collecting quality indicator (QI) data from all VA research facilities for quality improvement purposes.12-14 In this study, VAORO analyzed these data to assess changes in VA HRPP QI data from 2010 to 2012 and identify areas for improvement.

Methods

As part of the VA HRPP quality assurance program, each VA research facility was required to conduct annual audits of all informed consent documents (ICDs) and regulatory audits of all human research protocols once every 3 years by qualified research compliance officers (RCOs).15 Protocol regulatory audits were limited to a 3-year look back of the protocols. Tools were developed for the annual ICD and triennial protocol regulatory audits (available at http://www.va.gov/ORO/Research_Compliance_Education.asp). Facility RCOs were then trained to use these tools to conduct audits.

Data Collection

Data were collected annually from all 107 VA research facilities. Information collected included compliance with ICD and Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act authorization requirements; compliance with requirements for IRB and R&DC initial approval of human research protocols; compliance with selected informed consent requirements; for-cause suspension or termination of human research protocols; research-related serious AEs; compliance with continuing review requirements; subject enrollment according to inclusion and exclusion criteria; research personnel scopes of practice; investigator human research protection training; international research; and research involving vulnerable subjects. No individually identifiable personal information was collected. As this was a VA quality assurance project and no individually identifiable information was collected, no IRB review and approval of the project was required.16

All data collected were entered into a database for analysis. When necessary, facilities were contacted to verify the accuracy and uniformity of data reported.

Data Analysis

The Mantel-Haenszel chi-square test for trend was used to determine the trend of changes from 2010 through 2012.17 A P value of < .05 was considered to be statistically significant. For those QIs with statistically significant changes, VAORO calculated the percent changes and the actual numbers impacted, ie, the actual numbers of ICDs, human research protocols, case histories, or research personnel affected by these changes.18

Results

The HRPP QI data was collected from 2010 through 2012 from all 107 VA research facilities (Table 1). There were a total of 25 QIs; 18 had all 3-year data available and 7 lacked 2010 data. Only those 18 QI data available from all 3 years were included for this analysis. The 2010 data collected for QIs related to for-cause suspension or termination of protocols and research personnel scopes of practice and training requirements were derived from all human, animal, and safety research protocols audited, not just the human research protocols audited. However, these data were included for comparison with the 2011 and 2012 data, because nonhuman research protocols audited constituted < 30% of the total. Based on VAORO on-site routine reviews of facilities’ HRPPs, animal care and use programs, as well as research safety and security programs, the authors believe that the QI rates in these nonhuman research protocols were similar to those of human research protocols.

From a total of 18 QIs with all 3-year data available for analysis, 9 QIs did not show any statistically significant changes; whereas 9 QIs showed statistically significant changes from 2010 to 2012 (Table 1). These 9 QIs were: (1) incorrect ICDs used; (2) number of protocols suspended or terminated due to cause; (3) protocols suspended or terminated due to investigator concerns; (4) informed consent not obtained prior to initiation of the study; (5) research personnel without research scopes of practice; (6) research personnel working outside of scopes of practice; (7) required training not current for research personnel; (8) research personnel working without initial training; and (9) research personnel lapsed in continuing training.

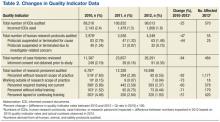

Table 2 shows the percent changes and the actual numbers impacted by the changes in the 9 QIs that showed statistically significant changes. The percent changes describe the magnitude of changes, and the numbers impacted provide information on the actual numbers of events (ie, ICDs, human research protocols, case histories, or research personnel) affected by these changes in 2012 if the QI rates had stayed the same as those of 2010.

All 9 QIs with statistically significant changes showed improvement, ranging from 25% improvement in incorrect ICDs used to 92% improvement in research personnel without scopes of practice (Table 2). The actual numbers impacted (ie, the difference between numbers expected in 2012 based on 2010 QI rates and the actual numbers observed in 2012) ranged from 55 protocols suspended or terminated for cause to 1,177 research scopes of practice.

Of the 9 QIs with no statistically significant changes, all but 2 QIs had QI rates of < 1% in 2010, suggesting that these QI rates were already so low that further improvement was difficult to achieve. The 2 exceptions were lapses in IRB continuing reviews and international research conducted without VA Chief Research and Development Officer (CRADO) approval.

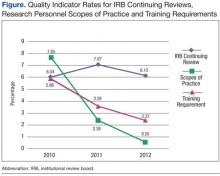

The rates of lapse in IRB continuing reviews remained high at 6% to 7% between 2010 and 2012 (Figure). In contrast, the rates of research personnel lacking scopes of practice and required training not current, which had comparable high rates in 2010, decreased sharply from 2010 to 2012.

Federal policies require that all individuals participating in research at international sites be provided with appropriate protections that are in accord with those given to research subjects within the U.S. as well as protections considered appropriate by local authorities and customary at the international site.1 VA policies require that permissions be obtained from the CRADO prior to initiating any VA-approved international research.4

Likewise, federal policies require additional protections when research involves vulnerable populations, such as children and prisoners.1 VA policies require that permission be obtained from the CRADO prior to initiating any research involving children or prisoners.4

Data on international research were available for all 3 years (Table 1). However, data on research involving children and prisoners were available only in 2011 and 2012. Although the numbers of these research protocols were small, ranging from 0 to 8 protocols, a high percentage of these protocols, ranging from 21% to 100%, did not receive CRADO approval prior to the initiation of the studies.

Discussion

The data presented in this report reveal that there has been considerable improvement in VA HRPPs since VAORO started to collect QI data in 2010. Of the QI data available from 2010 through 2012, 9 showed improvement, none showed deterioration. Of the 9 QIs that showed no statistically significant differences, 7 had very low QI rates in 2010 (most were < 1%). Consequently, further improvement may be difficult to achieve. On the other hand, VAORO identified 2 QIs to be in need of improvement.

The main purpose of collecting these data is to promote quality improvement. Each year VAORO provides feedback to VA research facilities by giving each facility its QI data along with the national and network averages so that each facility knows where it stands at the national and VISN level. It is hoped that with this information, facilities will be able to identify strengths and weaknesses and carry out quality improvement measures accordingly.

Several potential reasons exist for the observed improvements. Possibly, improvements could be due to reporting errors, for example, if facilities were underreporting noncompliance. However, underreporting is unlikely, because data were collected from independent RCO audits of ICDs and regulatory protocol audits. At VA, RCOs report directly to institutional officials and function independently of the Research Service.

Some facilities also may have been systematically “gaming the system” in order to make their programs look better. For example, some IRBs might become less likely to suspend a protocol when it should be suspended. While the above possibilities cannot be ruled out completely, the authors believe that they are unlikely. First, not all QIs were improved. Particularly, lapse in IRB continuing reviews remained high and unchanged from 2010 to 2012. In addition, routine on-site reviews of facility’s HRPPs have independently verified some of the improvements observed in these QI data.

Two areas in need of improvement have been identified: lapses in IRB continuing reviews and studies requiring CRADO. These 2 areas can be easily improved if facilities are willing to devote effort and resources to improve IRB procedures and practices. In a previous study based on 2011 QI data, the authors reported that VA facilities with a small human research program (active human research protocols of < 50) had a rate of lapse in IRB continuing reviews of 3.2%; facilities with a medium research program (50-200 active human research protocols) had a rate of 5.5%; and facilities with a large research program (> 200 active human research protocols) had a rate of 8.6%.14 Thus, facilities with a large research program particularly need to improve their IRB continuing review processes.

In addition to QI, these data provide opportunities to answer a number of important questions regarding HRPPs. For example, based on 2011 QI data, the authors had previously shown that HRPPs of facilities using their own VA IRBs and those using affiliated university IRBs as their IRBs of record performed equally well, providing scientific data for the first time to support the long-standing VA policy that it is acceptable for VA facilities to use their own IRB or the affiliated university IRB as the IRB of record.4,13 Likewise, there has been concern that facilities with small research programs may not have sufficient resources to support a vigorous HRPP.