User login

What could be behind your elderly patient’s subjective memory complaints?

Depression, anxiety, and dementia, as well as older age, female gender, lower education level, and decreased physical activity, have all been associated with memory loss reported by patients or family members (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cross-sectional studies). Memory complaints in patients with no cognitive impairment on short cognitive screening tests, such as the mini-mental status exam, may predict dementia (SOR: B, longitudinal studies). No consistent evidence supports pharmacologic treatment of reported memory loss that is not corroborated by objective findings (SOR: B, nonrandomized, poor-quality studies).

Is depression or polypharmacy at work?

Rajasree Nair, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

As the population ages, primary care physicians encounter a significant number of patients with memory loss and dementia. In clinical practice, patients with subjective memory complaints but normal cognitive testing present a diagnostic dilemma. Close attention to comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as polypharmacy, is essential.

While the US Preventive Services Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to screen, it notes that recognizing cognitive impairment early not only facilitates diagnostic and treatment decisions, but also allows clinicians to anticipate problems the patient may have in understanding and adhering to recommended therapy. Even though evidence of early or minimal dementia may be difficult to detect, identifying it promptly enables physicians to counsel patients and caregivers on the course of disease progression, warning signs, medication adherence, finances, and safety.

Evidence Summary

Several cross-sectional studies indicate that patients with subjective memory loss are more likely to be older, female, less physically active, in poorer health, less educated, and more depressed or anxious than unaffected patients.1-4 These studies concentrate mostly on elderly people living in the community.

A study of 1883 patients with normal baseline short-cognitive test results found that those with subjective memory complaints had a higher incidence of dementia.5 At 5-year follow-up, 15% of patients with baseline subjective memory complaints had developed dementia compared to only 6% of those without such complaints (odds ratio=2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-4.98).

A prospective cohort study that followed 158 patients with no evidence of dementia showed a significant correlation between informant-reported memory problems and development of dementia at 5 years.6 Forty-five percent of patients with informant-reported memory problems developed dementia after 5 years compared with 25% of patients who had only self-reported memory problems (P =.02). This result suggests that subjective memory problems reported by observers (family or caregivers) may be more predictive of dementia than self-reported memory complaints.

Donepezil, ginkgo biloba may not help these patients

Most trials of interventions to preserve memory have not enrolled patients with subjective memory complaints. However, data from trials that enrolled either asymptomatic elderly patients or patients with mild cognitive impairment don’t support the use of donepezil, ginkgo biloba, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, vitamin E, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, statins, hormone replacement therapy, or omega-3 fatty acids to delay progression to dementia.7-16

Could mental exercise help?

One systematic review of 22 longitudinal cohort studies, which included more than 29,000 patients, evaluated complex patterns of mental activity in early, mid-, and late-life in relation to the incidence of dementia. Dementia was diagnosed at a significantly lower rate in patients with a higher level of cognitive exercise, such as memory-based leisure activities and social interactions, than those with less rigorous daily cognitive challenges (relative risk=0.54; 95% CI, 0.49-0.59).17

This raises the possibility that mental exercise has neuroprotective effects. No randomized trials exist to support this hypothesis, however.

Recommendations

There is no consensus regarding the nomenclature applied to reported memory loss and mild cognitive impairment. The Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry provides definitions that can be used in the clinical setting (TABLE).18

The US Preventive Services Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for dementia in older adults (I recommendation).19 However, the Task Force notes that clinicians should assess cognitive function whenever they suspect impairment or deterioration based on direct observation, patient report, or concerns raised by family members, friends, or care-takers.

The American Geriatrics Society20 and American Academy of Neurology (AAN)21 acknowledge the subtle difference between age-associated memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment, and the difficulty of differentiating normal changes of aging from abnormal changes. The AAN’s guidelines for early detection of dementia emphasize the importance of diagnosing mild cognitive impairment or dementia early. However, the guidelines specifically exclude patients with subjective memory loss unaccompanied by objective cognitive deficits and offer no further discussion about these patients.

TABLE

Features of age-associated memory impairment vs mild cognitive impairment

| FEATURE | AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY IMPAIRMENT | MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

| Memory test results |

|

|

| Clinical course |

|

|

| ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation. | ||

| Source: Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry.18 | ||

1. St John P, Montgomery P. Is subjective memory loss correlated with MMSE scores or dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:80-83.

2. Lautenschlager NT, Flicker L, Vasikaran S, et al. Subjective memory complaints with and without objective memory impairment: relationship with risk factors for dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:731-734.

3. Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:983-991.

4. Mol ME, van Boxtel MP, Willems D, et al. Do subjective memory complaints predict cognitive dysfunction over time? A six-year follow-up of the Maastricht aging study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:432-441.

5. Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2045-2051.

6. Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724-1726.

7. Birks J, Flicker L. Donepezil for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD006104.-

8. Birks J, Grimley EV, Van Dongen M. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and demetia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD003120.-

9. Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br Med J. 2003;327:128-131.

10. Aisen P, Schafer K, Grundman M. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2819-2826.

11. Isaac M, Quinn R, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD002854.-

12. Malouf R, Grimley Evans J. Vitamin B6 for cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004393.-

13. Malouf M, Grimley Evans J, Areosa SA. Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for cognition and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):004514.-

14. Scott HD, Laake K. Statins for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):003160.-

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: recommendations and rationale. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:358-364.

16. Lim WS, Gammack JK, Van Niekerk JK, et al. Omega 3 fatty acid for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005379.-

17. Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P. Brain reserve and dementia: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:441-454.

18. Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry. Illustrated ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2006.

19. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for dementia: recommendation and rationale summary for patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:925-926.

20. Durso SC, Gwyther L, Roos B, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Abstracted from the American Academy of Neurology’s dementia guidelines for early detection, diagnosis and management of dementia. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2006. Available at: www.americangeriatrics.org/products/positionpapers/aan_dementia.shtml. Accessed April 9, 2007.

21. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1133-1142.

Depression, anxiety, and dementia, as well as older age, female gender, lower education level, and decreased physical activity, have all been associated with memory loss reported by patients or family members (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cross-sectional studies). Memory complaints in patients with no cognitive impairment on short cognitive screening tests, such as the mini-mental status exam, may predict dementia (SOR: B, longitudinal studies). No consistent evidence supports pharmacologic treatment of reported memory loss that is not corroborated by objective findings (SOR: B, nonrandomized, poor-quality studies).

Is depression or polypharmacy at work?

Rajasree Nair, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

As the population ages, primary care physicians encounter a significant number of patients with memory loss and dementia. In clinical practice, patients with subjective memory complaints but normal cognitive testing present a diagnostic dilemma. Close attention to comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as polypharmacy, is essential.

While the US Preventive Services Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to screen, it notes that recognizing cognitive impairment early not only facilitates diagnostic and treatment decisions, but also allows clinicians to anticipate problems the patient may have in understanding and adhering to recommended therapy. Even though evidence of early or minimal dementia may be difficult to detect, identifying it promptly enables physicians to counsel patients and caregivers on the course of disease progression, warning signs, medication adherence, finances, and safety.

Evidence Summary

Several cross-sectional studies indicate that patients with subjective memory loss are more likely to be older, female, less physically active, in poorer health, less educated, and more depressed or anxious than unaffected patients.1-4 These studies concentrate mostly on elderly people living in the community.

A study of 1883 patients with normal baseline short-cognitive test results found that those with subjective memory complaints had a higher incidence of dementia.5 At 5-year follow-up, 15% of patients with baseline subjective memory complaints had developed dementia compared to only 6% of those without such complaints (odds ratio=2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-4.98).

A prospective cohort study that followed 158 patients with no evidence of dementia showed a significant correlation between informant-reported memory problems and development of dementia at 5 years.6 Forty-five percent of patients with informant-reported memory problems developed dementia after 5 years compared with 25% of patients who had only self-reported memory problems (P =.02). This result suggests that subjective memory problems reported by observers (family or caregivers) may be more predictive of dementia than self-reported memory complaints.

Donepezil, ginkgo biloba may not help these patients

Most trials of interventions to preserve memory have not enrolled patients with subjective memory complaints. However, data from trials that enrolled either asymptomatic elderly patients or patients with mild cognitive impairment don’t support the use of donepezil, ginkgo biloba, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, vitamin E, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, statins, hormone replacement therapy, or omega-3 fatty acids to delay progression to dementia.7-16

Could mental exercise help?

One systematic review of 22 longitudinal cohort studies, which included more than 29,000 patients, evaluated complex patterns of mental activity in early, mid-, and late-life in relation to the incidence of dementia. Dementia was diagnosed at a significantly lower rate in patients with a higher level of cognitive exercise, such as memory-based leisure activities and social interactions, than those with less rigorous daily cognitive challenges (relative risk=0.54; 95% CI, 0.49-0.59).17

This raises the possibility that mental exercise has neuroprotective effects. No randomized trials exist to support this hypothesis, however.

Recommendations

There is no consensus regarding the nomenclature applied to reported memory loss and mild cognitive impairment. The Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry provides definitions that can be used in the clinical setting (TABLE).18

The US Preventive Services Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for dementia in older adults (I recommendation).19 However, the Task Force notes that clinicians should assess cognitive function whenever they suspect impairment or deterioration based on direct observation, patient report, or concerns raised by family members, friends, or care-takers.

The American Geriatrics Society20 and American Academy of Neurology (AAN)21 acknowledge the subtle difference between age-associated memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment, and the difficulty of differentiating normal changes of aging from abnormal changes. The AAN’s guidelines for early detection of dementia emphasize the importance of diagnosing mild cognitive impairment or dementia early. However, the guidelines specifically exclude patients with subjective memory loss unaccompanied by objective cognitive deficits and offer no further discussion about these patients.

TABLE

Features of age-associated memory impairment vs mild cognitive impairment

| FEATURE | AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY IMPAIRMENT | MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

| Memory test results |

|

|

| Clinical course |

|

|

| ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation. | ||

| Source: Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry.18 | ||

Depression, anxiety, and dementia, as well as older age, female gender, lower education level, and decreased physical activity, have all been associated with memory loss reported by patients or family members (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, cross-sectional studies). Memory complaints in patients with no cognitive impairment on short cognitive screening tests, such as the mini-mental status exam, may predict dementia (SOR: B, longitudinal studies). No consistent evidence supports pharmacologic treatment of reported memory loss that is not corroborated by objective findings (SOR: B, nonrandomized, poor-quality studies).

Is depression or polypharmacy at work?

Rajasree Nair, MD

Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, Tex

As the population ages, primary care physicians encounter a significant number of patients with memory loss and dementia. In clinical practice, patients with subjective memory complaints but normal cognitive testing present a diagnostic dilemma. Close attention to comorbid psychiatric conditions such as depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders, as well as polypharmacy, is essential.

While the US Preventive Services Task Force indicates that there is insufficient evidence to screen, it notes that recognizing cognitive impairment early not only facilitates diagnostic and treatment decisions, but also allows clinicians to anticipate problems the patient may have in understanding and adhering to recommended therapy. Even though evidence of early or minimal dementia may be difficult to detect, identifying it promptly enables physicians to counsel patients and caregivers on the course of disease progression, warning signs, medication adherence, finances, and safety.

Evidence Summary

Several cross-sectional studies indicate that patients with subjective memory loss are more likely to be older, female, less physically active, in poorer health, less educated, and more depressed or anxious than unaffected patients.1-4 These studies concentrate mostly on elderly people living in the community.

A study of 1883 patients with normal baseline short-cognitive test results found that those with subjective memory complaints had a higher incidence of dementia.5 At 5-year follow-up, 15% of patients with baseline subjective memory complaints had developed dementia compared to only 6% of those without such complaints (odds ratio=2.7; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.45-4.98).

A prospective cohort study that followed 158 patients with no evidence of dementia showed a significant correlation between informant-reported memory problems and development of dementia at 5 years.6 Forty-five percent of patients with informant-reported memory problems developed dementia after 5 years compared with 25% of patients who had only self-reported memory problems (P =.02). This result suggests that subjective memory problems reported by observers (family or caregivers) may be more predictive of dementia than self-reported memory complaints.

Donepezil, ginkgo biloba may not help these patients

Most trials of interventions to preserve memory have not enrolled patients with subjective memory complaints. However, data from trials that enrolled either asymptomatic elderly patients or patients with mild cognitive impairment don’t support the use of donepezil, ginkgo biloba, NSAIDs, COX-2 inhibitors, vitamin E, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, statins, hormone replacement therapy, or omega-3 fatty acids to delay progression to dementia.7-16

Could mental exercise help?

One systematic review of 22 longitudinal cohort studies, which included more than 29,000 patients, evaluated complex patterns of mental activity in early, mid-, and late-life in relation to the incidence of dementia. Dementia was diagnosed at a significantly lower rate in patients with a higher level of cognitive exercise, such as memory-based leisure activities and social interactions, than those with less rigorous daily cognitive challenges (relative risk=0.54; 95% CI, 0.49-0.59).17

This raises the possibility that mental exercise has neuroprotective effects. No randomized trials exist to support this hypothesis, however.

Recommendations

There is no consensus regarding the nomenclature applied to reported memory loss and mild cognitive impairment. The Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry provides definitions that can be used in the clinical setting (TABLE).18

The US Preventive Services Task Force concludes that evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against routine screening for dementia in older adults (I recommendation).19 However, the Task Force notes that clinicians should assess cognitive function whenever they suspect impairment or deterioration based on direct observation, patient report, or concerns raised by family members, friends, or care-takers.

The American Geriatrics Society20 and American Academy of Neurology (AAN)21 acknowledge the subtle difference between age-associated memory impairment and mild cognitive impairment, and the difficulty of differentiating normal changes of aging from abnormal changes. The AAN’s guidelines for early detection of dementia emphasize the importance of diagnosing mild cognitive impairment or dementia early. However, the guidelines specifically exclude patients with subjective memory loss unaccompanied by objective cognitive deficits and offer no further discussion about these patients.

TABLE

Features of age-associated memory impairment vs mild cognitive impairment

| FEATURE | AGE-ASSOCIATED MEMORY IMPAIRMENT | MILD COGNITIVE IMPAIRMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical presentation |

|

|

| Memory test results |

|

|

| Clinical course |

|

|

| ADLs, activities of daily living; IADLs, instrumental activities of daily living; SD, standard deviation. | ||

| Source: Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry.18 | ||

1. St John P, Montgomery P. Is subjective memory loss correlated with MMSE scores or dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:80-83.

2. Lautenschlager NT, Flicker L, Vasikaran S, et al. Subjective memory complaints with and without objective memory impairment: relationship with risk factors for dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:731-734.

3. Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:983-991.

4. Mol ME, van Boxtel MP, Willems D, et al. Do subjective memory complaints predict cognitive dysfunction over time? A six-year follow-up of the Maastricht aging study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:432-441.

5. Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2045-2051.

6. Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724-1726.

7. Birks J, Flicker L. Donepezil for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD006104.-

8. Birks J, Grimley EV, Van Dongen M. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and demetia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD003120.-

9. Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br Med J. 2003;327:128-131.

10. Aisen P, Schafer K, Grundman M. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2819-2826.

11. Isaac M, Quinn R, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD002854.-

12. Malouf R, Grimley Evans J. Vitamin B6 for cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004393.-

13. Malouf M, Grimley Evans J, Areosa SA. Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for cognition and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):004514.-

14. Scott HD, Laake K. Statins for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):003160.-

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: recommendations and rationale. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:358-364.

16. Lim WS, Gammack JK, Van Niekerk JK, et al. Omega 3 fatty acid for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005379.-

17. Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P. Brain reserve and dementia: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:441-454.

18. Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry. Illustrated ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2006.

19. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for dementia: recommendation and rationale summary for patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:925-926.

20. Durso SC, Gwyther L, Roos B, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Abstracted from the American Academy of Neurology’s dementia guidelines for early detection, diagnosis and management of dementia. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2006. Available at: www.americangeriatrics.org/products/positionpapers/aan_dementia.shtml. Accessed April 9, 2007.

21. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1133-1142.

1. St John P, Montgomery P. Is subjective memory loss correlated with MMSE scores or dementia? J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2003;16:80-83.

2. Lautenschlager NT, Flicker L, Vasikaran S, et al. Subjective memory complaints with and without objective memory impairment: relationship with risk factors for dementia. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13:731-734.

3. Jonker C, Geerlings MI, Schmand B. Are memory complaints predictive for dementia? A review of clinical and population-based studies. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;15:983-991.

4. Mol ME, van Boxtel MP, Willems D, et al. Do subjective memory complaints predict cognitive dysfunction over time? A six-year follow-up of the Maastricht aging study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:432-441.

5. Wang L, van Belle G, Crane PK, et al. Subjective memory deterioration and future dementia in people aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:2045-2051.

6. Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus individual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neurology. 2000;55:1724-1726.

7. Birks J, Flicker L. Donepezil for mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD006104.-

8. Birks J, Grimley EV, Van Dongen M. Ginkgo biloba for cognitive impairment and demetia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(2):CD003120.-

9. Etminan M, Gill S, Samii A. Effect of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on risk of Alzheimer’s disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Br Med J. 2003;327:128-131.

10. Aisen P, Schafer K, Grundman M. Effects of rofecoxib or naproxen vs placebo on Alzheimer disease progression: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2819-2826.

11. Isaac M, Quinn R, Tabet N. Vitamin E for Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(4):CD002854.-

12. Malouf R, Grimley Evans J. Vitamin B6 for cognition. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):CD004393.-

13. Malouf M, Grimley Evans J, Areosa SA. Folic acid with or without vitamin B12 for cognition and dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;(4):004514.-

14. Scott HD, Laake K. Statins for the prevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(3):003160.-

15. US Preventive Services Task Force. Postmenopausal hormone replacement therapy for the primary prevention of chronic conditions: recommendations and rationale. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67:358-364.

16. Lim WS, Gammack JK, Van Niekerk JK, et al. Omega 3 fatty acid for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(1):CD005379.-

17. Valenzuela MJ, Sachdev P. Brain reserve and dementia: a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2006;36:441-454.

18. Spar JE, La Rue A. Clinical Manual of Geriatric Psychiatry. Illustrated ed. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2006.

19. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for dementia: recommendation and rationale summary for patients. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:925-926.

20. Durso SC, Gwyther L, Roos B, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines. Abstracted from the American Academy of Neurology’s dementia guidelines for early detection, diagnosis and management of dementia. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2006. Available at: www.americangeriatrics.org/products/positionpapers/aan_dementia.shtml. Accessed April 9, 2007.

21. Petersen RC, Stevens JC, Ganguli M, et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the quality standards subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1133-1142.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best way to manage benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

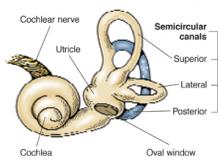

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network