User login

Do abnormal fetal kick counts predict intrauterine death in average-risk pregnancies?

No. Structured daily monitoring of fetal movement doesn’t decrease the rate of all-cause antenatal death in average-risk pregnancies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, single good-quality, randomized controlled trial [RCT]). Although maternal perception of decreased fetal movement may herald fetal death, it isn’t specific for poor neonatal outcome (SOR: B, single good-quality, diagnostic cohort study). Monitoring fetal movement increases the frequency of non-stress-test monitoring (SOR: B, single good-quality RCT).

A rare tragedy that monitoring can’t prevent

Johanna Warren, MD

Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland

Fetal movement is a marker of well-being. We draw on our experience with fetal monitoring to know that in healthy fetuses, movement increases sympathetic response and accelerates heart rate. Fetuses with severe acid-base disorders can’t oxygenate their muscles adequately and don’t move. Fetal movement, therefore, is a relatively simple indirect means of fetal assessment that indicates a lack of significant acidosis.

Intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD) is a rare but devastating event in an uncomplicated term pregnancy; it occurs in about 5000 of nearly 4 million us births each year (0.125). As the authors of this Clinical Inquiry state, nearly half of term IUFDs are unexpected and unexplained. Although it may be a logical extension to apply our knowledge of fetal physiology in an attempt to prevent IUFD, no conclusive evidence suggests that daily monitoring of fetal movement improves fetal or neonatal outcomes. We can hope that, with more accurate dating methods and more aggressive control of hypertension, diabetes, and anemia in pregnancy, the number of term IUFDs will continue to fall.

Evidence summary

Nearly 50% of late-pregnancy IUFDs have no associated risk factors. Fetal demise, however, may be heralded by decreased fetal movement followed by cessation of movement at least 12 hours before death.1 Maternal monitoring of fetal movement by kick counts has been proposed as a method to verify fetal well-being and decrease the rate of IUFD in the general obstetric population.

Counting doesn’t reduce antenatal death, large study shows

A well-done RCT randomized 68,654 women to either usual care or structured, daily monitoring of fetal movement using the count-to-10 method—daily maternal documentation of the amount of time it takes to perceive 10 fetal movements. Usual care was comprised of a query about fetal movement at antenatal visits and instruction to perform fetal movement monitoring at the provider’s discretion. Mothers were told to visit their health-care provider for evaluation if they felt no movement in 24 hours or fewer than 10 movements in 10 hours during a 48-hour period. The trial showed no benefit from monitoring in reducing the rate of antenatal death from all causes.

The rate of all fetal deaths in the counting group was 2.9 per 1000 normally formed, live, singleton births; the rate in the control group was 2.67 (absolute risk reduction=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.5 to 0.98). Women in the counting group spent an average of 160 hours counting during pregnancy and had a statistically significant increase in fetal non-stress-test (NST) monitoring (odds ratio [OR]=1.39; 95% CI, 1.31-1.49; number needed to harm [NNH]=50 to cause 1 additional NST). A statistically insignificant trend toward increased antepartum admissions was also noted in the counting group.2

Maternal perception of less movement not linked to fetal outcome

A retrospective cohort study of 6793 patients compared pregnancy outcomes of 463 women who presented for evaluation of decreased fetal movement with outcomes among the general obstetric population. The study excluded women who reported complete cessation of fetal movement.

Pregnancies evaluated for decreased fetal movement were less likely to have an Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes (relative risk [RR]=0.56; 95% CI, 0.29-0.96; P=.05) and less likely to be preterm (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.94; P=.02). No significant difference in cesarean section for fetal distress or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit was noted between the study and control groups. The study suggests that maternal perception of decreased fetal movement is not associated with poor fetal outcome.3

A recent rigorous systematic review yielded no significant outcome effect related to fetal kick counts.4 A prospective cohort study of 4383 births in California, using historical controls, found a drop in fetal mortality from 8.7 to 2.1 deaths/1000. The historical control rate was higher than statewide data from the same time period, however. The overall weaker design of the study and probable effect of regression to the mean significantly limit the interpretation of outcomes.5

Recommendations

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) makes no recommendation for or against assessing daily fetal movement in routine pregnancies. ACOG notes that no consistent evidence suggests that formal assessment of fetal movement decreases IUFD.6

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends instructing patients on “daily identification of fetal movement at the 28-week visit.” The institute doesn’t recommend specific criteria for evaluating fetal movements or offer recommendations for follow-up of a maternal report of decreased fetal movement.1 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in Great Britain recommends against routine formal fetal-movement counting.7

1. Institute for Clinical systems Improvement. Routine Prenatal Care. 12th ed. August 2008. Available at: http://www.icsi.org/prenatal_care_4/prenatal_care__routine__full_version__2.html. Accessed november 7, 2008.

2. Grant A, Elbourne D, Valentin L, et al. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risk of antepartum late death in normally formed singletons. Lancet. 1989;2:345-349.

3. Harrington K, Thompson O, Jordan L, et al. Obstetric outcome in women who present with a reduction in fetal movements in the third trimester of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:77-82.

4. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

5. Moore TR, Piacquadio K. A prospective evaluation of fetal movement screening to reduce the incidence of antepartum fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1075-1080.

6. ACOG. Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 9. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology; October 1999.

7. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. Clinical Guideline 62. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; March 2008.

No. Structured daily monitoring of fetal movement doesn’t decrease the rate of all-cause antenatal death in average-risk pregnancies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, single good-quality, randomized controlled trial [RCT]). Although maternal perception of decreased fetal movement may herald fetal death, it isn’t specific for poor neonatal outcome (SOR: B, single good-quality, diagnostic cohort study). Monitoring fetal movement increases the frequency of non-stress-test monitoring (SOR: B, single good-quality RCT).

A rare tragedy that monitoring can’t prevent

Johanna Warren, MD

Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland

Fetal movement is a marker of well-being. We draw on our experience with fetal monitoring to know that in healthy fetuses, movement increases sympathetic response and accelerates heart rate. Fetuses with severe acid-base disorders can’t oxygenate their muscles adequately and don’t move. Fetal movement, therefore, is a relatively simple indirect means of fetal assessment that indicates a lack of significant acidosis.

Intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD) is a rare but devastating event in an uncomplicated term pregnancy; it occurs in about 5000 of nearly 4 million us births each year (0.125). As the authors of this Clinical Inquiry state, nearly half of term IUFDs are unexpected and unexplained. Although it may be a logical extension to apply our knowledge of fetal physiology in an attempt to prevent IUFD, no conclusive evidence suggests that daily monitoring of fetal movement improves fetal or neonatal outcomes. We can hope that, with more accurate dating methods and more aggressive control of hypertension, diabetes, and anemia in pregnancy, the number of term IUFDs will continue to fall.

Evidence summary

Nearly 50% of late-pregnancy IUFDs have no associated risk factors. Fetal demise, however, may be heralded by decreased fetal movement followed by cessation of movement at least 12 hours before death.1 Maternal monitoring of fetal movement by kick counts has been proposed as a method to verify fetal well-being and decrease the rate of IUFD in the general obstetric population.

Counting doesn’t reduce antenatal death, large study shows

A well-done RCT randomized 68,654 women to either usual care or structured, daily monitoring of fetal movement using the count-to-10 method—daily maternal documentation of the amount of time it takes to perceive 10 fetal movements. Usual care was comprised of a query about fetal movement at antenatal visits and instruction to perform fetal movement monitoring at the provider’s discretion. Mothers were told to visit their health-care provider for evaluation if they felt no movement in 24 hours or fewer than 10 movements in 10 hours during a 48-hour period. The trial showed no benefit from monitoring in reducing the rate of antenatal death from all causes.

The rate of all fetal deaths in the counting group was 2.9 per 1000 normally formed, live, singleton births; the rate in the control group was 2.67 (absolute risk reduction=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.5 to 0.98). Women in the counting group spent an average of 160 hours counting during pregnancy and had a statistically significant increase in fetal non-stress-test (NST) monitoring (odds ratio [OR]=1.39; 95% CI, 1.31-1.49; number needed to harm [NNH]=50 to cause 1 additional NST). A statistically insignificant trend toward increased antepartum admissions was also noted in the counting group.2

Maternal perception of less movement not linked to fetal outcome

A retrospective cohort study of 6793 patients compared pregnancy outcomes of 463 women who presented for evaluation of decreased fetal movement with outcomes among the general obstetric population. The study excluded women who reported complete cessation of fetal movement.

Pregnancies evaluated for decreased fetal movement were less likely to have an Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes (relative risk [RR]=0.56; 95% CI, 0.29-0.96; P=.05) and less likely to be preterm (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.94; P=.02). No significant difference in cesarean section for fetal distress or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit was noted between the study and control groups. The study suggests that maternal perception of decreased fetal movement is not associated with poor fetal outcome.3

A recent rigorous systematic review yielded no significant outcome effect related to fetal kick counts.4 A prospective cohort study of 4383 births in California, using historical controls, found a drop in fetal mortality from 8.7 to 2.1 deaths/1000. The historical control rate was higher than statewide data from the same time period, however. The overall weaker design of the study and probable effect of regression to the mean significantly limit the interpretation of outcomes.5

Recommendations

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) makes no recommendation for or against assessing daily fetal movement in routine pregnancies. ACOG notes that no consistent evidence suggests that formal assessment of fetal movement decreases IUFD.6

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends instructing patients on “daily identification of fetal movement at the 28-week visit.” The institute doesn’t recommend specific criteria for evaluating fetal movements or offer recommendations for follow-up of a maternal report of decreased fetal movement.1 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in Great Britain recommends against routine formal fetal-movement counting.7

No. Structured daily monitoring of fetal movement doesn’t decrease the rate of all-cause antenatal death in average-risk pregnancies (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, single good-quality, randomized controlled trial [RCT]). Although maternal perception of decreased fetal movement may herald fetal death, it isn’t specific for poor neonatal outcome (SOR: B, single good-quality, diagnostic cohort study). Monitoring fetal movement increases the frequency of non-stress-test monitoring (SOR: B, single good-quality RCT).

A rare tragedy that monitoring can’t prevent

Johanna Warren, MD

Oregon Health and Sciences University, Portland

Fetal movement is a marker of well-being. We draw on our experience with fetal monitoring to know that in healthy fetuses, movement increases sympathetic response and accelerates heart rate. Fetuses with severe acid-base disorders can’t oxygenate their muscles adequately and don’t move. Fetal movement, therefore, is a relatively simple indirect means of fetal assessment that indicates a lack of significant acidosis.

Intrauterine fetal demise (IUFD) is a rare but devastating event in an uncomplicated term pregnancy; it occurs in about 5000 of nearly 4 million us births each year (0.125). As the authors of this Clinical Inquiry state, nearly half of term IUFDs are unexpected and unexplained. Although it may be a logical extension to apply our knowledge of fetal physiology in an attempt to prevent IUFD, no conclusive evidence suggests that daily monitoring of fetal movement improves fetal or neonatal outcomes. We can hope that, with more accurate dating methods and more aggressive control of hypertension, diabetes, and anemia in pregnancy, the number of term IUFDs will continue to fall.

Evidence summary

Nearly 50% of late-pregnancy IUFDs have no associated risk factors. Fetal demise, however, may be heralded by decreased fetal movement followed by cessation of movement at least 12 hours before death.1 Maternal monitoring of fetal movement by kick counts has been proposed as a method to verify fetal well-being and decrease the rate of IUFD in the general obstetric population.

Counting doesn’t reduce antenatal death, large study shows

A well-done RCT randomized 68,654 women to either usual care or structured, daily monitoring of fetal movement using the count-to-10 method—daily maternal documentation of the amount of time it takes to perceive 10 fetal movements. Usual care was comprised of a query about fetal movement at antenatal visits and instruction to perform fetal movement monitoring at the provider’s discretion. Mothers were told to visit their health-care provider for evaluation if they felt no movement in 24 hours or fewer than 10 movements in 10 hours during a 48-hour period. The trial showed no benefit from monitoring in reducing the rate of antenatal death from all causes.

The rate of all fetal deaths in the counting group was 2.9 per 1000 normally formed, live, singleton births; the rate in the control group was 2.67 (absolute risk reduction=0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI], –0.5 to 0.98). Women in the counting group spent an average of 160 hours counting during pregnancy and had a statistically significant increase in fetal non-stress-test (NST) monitoring (odds ratio [OR]=1.39; 95% CI, 1.31-1.49; number needed to harm [NNH]=50 to cause 1 additional NST). A statistically insignificant trend toward increased antepartum admissions was also noted in the counting group.2

Maternal perception of less movement not linked to fetal outcome

A retrospective cohort study of 6793 patients compared pregnancy outcomes of 463 women who presented for evaluation of decreased fetal movement with outcomes among the general obstetric population. The study excluded women who reported complete cessation of fetal movement.

Pregnancies evaluated for decreased fetal movement were less likely to have an Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes (relative risk [RR]=0.56; 95% CI, 0.29-0.96; P=.05) and less likely to be preterm (RR=0.68; 95% CI, 0.48-0.94; P=.02). No significant difference in cesarean section for fetal distress or admission to the neonatal intensive care unit was noted between the study and control groups. The study suggests that maternal perception of decreased fetal movement is not associated with poor fetal outcome.3

A recent rigorous systematic review yielded no significant outcome effect related to fetal kick counts.4 A prospective cohort study of 4383 births in California, using historical controls, found a drop in fetal mortality from 8.7 to 2.1 deaths/1000. The historical control rate was higher than statewide data from the same time period, however. The overall weaker design of the study and probable effect of regression to the mean significantly limit the interpretation of outcomes.5

Recommendations

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) makes no recommendation for or against assessing daily fetal movement in routine pregnancies. ACOG notes that no consistent evidence suggests that formal assessment of fetal movement decreases IUFD.6

The Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement recommends instructing patients on “daily identification of fetal movement at the 28-week visit.” The institute doesn’t recommend specific criteria for evaluating fetal movements or offer recommendations for follow-up of a maternal report of decreased fetal movement.1 The National Institute for Clinical Excellence in Great Britain recommends against routine formal fetal-movement counting.7

1. Institute for Clinical systems Improvement. Routine Prenatal Care. 12th ed. August 2008. Available at: http://www.icsi.org/prenatal_care_4/prenatal_care__routine__full_version__2.html. Accessed november 7, 2008.

2. Grant A, Elbourne D, Valentin L, et al. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risk of antepartum late death in normally formed singletons. Lancet. 1989;2:345-349.

3. Harrington K, Thompson O, Jordan L, et al. Obstetric outcome in women who present with a reduction in fetal movements in the third trimester of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:77-82.

4. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

5. Moore TR, Piacquadio K. A prospective evaluation of fetal movement screening to reduce the incidence of antepartum fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1075-1080.

6. ACOG. Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 9. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology; October 1999.

7. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. Clinical Guideline 62. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; March 2008.

1. Institute for Clinical systems Improvement. Routine Prenatal Care. 12th ed. August 2008. Available at: http://www.icsi.org/prenatal_care_4/prenatal_care__routine__full_version__2.html. Accessed november 7, 2008.

2. Grant A, Elbourne D, Valentin L, et al. Routine formal fetal movement counting and risk of antepartum late death in normally formed singletons. Lancet. 1989;2:345-349.

3. Harrington K, Thompson O, Jordan L, et al. Obstetric outcome in women who present with a reduction in fetal movements in the third trimester of pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 1998;26:77-82.

4. Mangesi L, Hofmeyr GJ. Fetal movement counting for assessment of fetal wellbeing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD004909.-

5. Moore TR, Piacquadio K. A prospective evaluation of fetal movement screening to reduce the incidence of antepartum fetal death. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1075-1080.

6. ACOG. Antepartum Fetal Surveillance. ACOG Practice Bulletin, Number 9. Washington, DC: American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology; October 1999.

7. National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Antenatal Care: Routine Care for the Healthy Pregnant Woman. Clinical Guideline 62. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence; March 2008.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

How should patients with Barrett’s esophagus be monitored?

Some patients who have been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus will develop dysplasia and, in some cases, esophageal carcinoma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on consistent cohort studies). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for all patients with Barrett’s esophagus as it is superior to other methods for detecting esophageal cancer (SOR: B, based on systematic review). The degree of dysplasia noted on biopsy specimens correlates with the risk of esophageal carcinoma development and should guide the frequency of subsequent evaluations (SOR: B, based on consistent cohort studies). The optimal frequency of endoscopy has yet to be determined in any randomized trial.

Recommendations from the 2002 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Practice Guideline provide guidance as to the frequency of endoscopy surveillance but were not based on an explicit systematic review of the literature (SOR: C, based on expert opinion; see TABLE 1).

Reduced monitoring for most patients with Barrett’s esophagus appears safe

Paul Crawford, MD

USAF–Eglin Family Practice Residency, Eglin Air Force Base, Fla

Family physicians have long been at the mercy of expert opinion when considering how to monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus. This review of the evidence clearly shows that the days of yearly EGD for all Barrett’s esophagus patients are over.

Unlike other conditions—such as cervical dysplasia, where monitoring and therapies to remove dysplasia are proven to save lives—Barrett’s esophagus progresses slowly and unpredictably. Thus, until technological advances allow identification of higher risk Barrett’s esophagus patients, an EGD every 3 years for those without dysplasia seems to be a reasonable monitoring interval. Perhaps most importantly, family physicians can reassure Barrett’s esophagus patients in the community that they are likely to live a normal lifespan and die of something other than esophageal cancer.

Evidence summary

Barrett’s esophagus has been defined as “a change in the esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus.”1 Intestinal metaplasia is a premalignant lesion for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Surveillance by serial endoscopy with biopsy has been recommended in an effort to find high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in an early, asymptomatic, and potentially curable stage.1-4 Approximately 75% of patients involved in a Barrett’s esophagus surveillance program will present with resectable tumors, compared with only 25% of those not receiving surveillance.4

A recent systematic review assessing screening tools for esophageal carcinoma found standard endoscopy to be superior (90%–100% sensitivity) to other less invasive methods such as questionnaire (60%–70%), and fecal occult blood testing (20%).4 Additional endoscopy tools such as brush and balloon cytology increased the cost of surveillance without any improvement in diagnostic yield.

The degree of dysplasia on esophageal biopsy in Barrett’s esophagus patients is currently the best indicator of risk of progression to esophageal carcinoma. The data reviewed by the ACG for the practice guideline was drawn from several prospective studies and one available registry. In sum, a total of 783 Barrett’s esophagus patients were followed for a mean of 2.9 to 7.3 years. Esophageal carcinoma developed in 2% of patients with no dysplasia, 7% of patients with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and 22% of patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD).1 The ACG recommendations regarding frequency of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were not based on an explicit critical appraisal of the literature. Recent cohort studies are consistent with recommendations for graded surveillance frequency. A randomized clinical trial to determine optimal endoscopic frequency and benefit has not been reported.

Several concerns have been raised regarding the utility of degree of dysplasia in determining optimal frequency of endoscopic surveillance. First, the progression of esophageal lesions over time is unpredictable. Skacel et al5 reported a series of 34 patients with LGD at initial pathologic examination. On subsequent surveillance endoscopy with repeat biopsy, 73% no longer demonstrated dysplasia. Such patients can be allowed to return to having surveillance every 3 years.

In addition to the non-linear progression of dysplasia, inter-rater reliability of the interpretation of pathology specimens varies substantially. Adequate reliability has been demonstrated among pathologists assigning results to 2 categories (either no dysplasia and LGD or HGD and carcinoma) (κ=0.7). Assignment to four distinct pathologic grades, however, was not reliable (κ=0.46, where 1.0 is complete agreement).1 In order to make a diagnosis of HGD or carcinoma, interpretation must be independently confirmed by 2 expert pathologists.1-3

Recommendations for frequent endoscopic surveillance are also weakened by the overall low rate of mortality from esophageal carcinoma noted in Barrett’s esophagus patients. A recent population based study demonstrated that there was no difference in overall mortality in those with a Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis compared with the general population.6 An increased risk of death from esophageal carcinoma was seen in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (4.7% seen in Barrett’s esophagus patients compared with 0.8% predicted in the general population; P<.05). The overall increased effect on mortality, however, was relatively small. Esophageal carcinoma accounted for less then 5% of deaths in Barrett’s esophagus patients reported during the study’s 6-year follow-up period.

Data from prospective studies published after 2002 may better predict prognosis for Barrett’s esophagus patients.6-9 Even lower rates of progression to esophageal carcinoma (<0.5% a year or <1/220 patient-years) have been reported in these studies drawing from the general population rather than referred patients, likely stemming from differences in gender mix, patient age, and risk factors.

In addition to grade of dysplasia, the length of the dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus segment is emerging as a potentially predictive risk factor. While the ACG cautions that esophageal cancer has been reported in patients with so-called “short segment” Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE) (≤3 cm),1 recent prospective studies have shown an increased risk of carcinoma development with long segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE).7-9 Weston et al7 reported a 2.4% progression rate to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with SSBE and no dysplasia compared with 6.8% with LSBE (P=.002). If patients had LGD, the rate of progression to esophageal carcinoma with SSBE was 5.3% and jumped to 35% in patients with LSBE (P<.001). Conio et al8 reported that 4 of 5 cases of esophageal carcinoma noted through surveillance had LSBE. Hage et al9 reported a significantly increased risk of progression to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with long segment disease (P<.02).

While currently still considered investigational, DNA content flow cytometry may be a future tool used in risk stratification. Reid et al10 report a 5-year cumulative risk of esophageal carcinoma of 1.7% in Barrett’s esophagus patients with negative, low-grade or indefinite grades of dysplasia. Subsequent application of flow cytometry allowed for further stratification of these low-risk patients. Those with neither aneuploidy nor an increased 4N had a 5-year cumulative risk of cancer of 0% while the risk for those with abnormalities on cytometry increased to 28% (relative risk=19; P<.001).

TABLE

Grade of dysplasia and recommendations for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance as proposed by the ACG

| DYSPLASIA | DOCUMENTATION | FOLLOW-UP ENDOSCOPY |

|---|---|---|

| None | Two EGDs with biopsy | 3 years |

| Low-grade | Highest grade on repeat | 1 year until no dysplasia |

| High-grade | Repeat EGD with biopsy to rule out cancer/document high-grade dysplasia; expert pathologist confirmation | Focal: every 3 months |

| Multifocal: intervention | ||

| Mucosal irregularity: EMR | ||

| ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection. Intervention: ie, esophagectomy. Ablative therapies only in the setting of a clinical trial or for those unable to tolerate surgery. | ||

Recommendations from others

The French Society of Digestive Endoscopy has published guidelines on monitoring Barrett’s esophagus.3 Their recommendations differ only slightly from the ACG in advocating a slightly increased frequency of EGD surveillance based on degree of dysplasia, and utilizing the length of the dysplastic segment in decision-making. Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the US Preventive Services Task Force make any specific recommendations about Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

1. Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1888-1895.

2. Management of Barrett’s esophagus. The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT), American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Consensus Panel. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:115-116.

3. Boyer J, Robaszkiewicz M. Guidelines of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy: Monitoring of Barrett’s esophagus. The Council of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy. Endoscopy 2000;32:498-499.

4. Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma: an evidence-based approach. Am J Med 2002;113:499-505.

5. Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, et al. The diagnosis of low grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3383-3387.

6. Anderson LA, Murray LJ, Murphy SJ, et al. Mortality in Barrett’s oesophagus: results from a population based study. Gut 2003;52:1081-1084.

7. Weston AP, Sharma P, Mathur S, et al. Risk stratification of barrett’s esophagus: updated prospective multivariate analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1657-1666.

8. Conio M, Blanchi S, Laertosa G, et al. Long-term endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1931-1939.

9. Hage M, Siersema PD, van Dekken H, Steyerber EW, Dees J, Kuipers EJ. Oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus after a mean follow-up of 12.7 years. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1175-1179.

10. Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, Blount P, Rabinovitch PS. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1669-1676.

Some patients who have been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus will develop dysplasia and, in some cases, esophageal carcinoma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on consistent cohort studies). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for all patients with Barrett’s esophagus as it is superior to other methods for detecting esophageal cancer (SOR: B, based on systematic review). The degree of dysplasia noted on biopsy specimens correlates with the risk of esophageal carcinoma development and should guide the frequency of subsequent evaluations (SOR: B, based on consistent cohort studies). The optimal frequency of endoscopy has yet to be determined in any randomized trial.

Recommendations from the 2002 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Practice Guideline provide guidance as to the frequency of endoscopy surveillance but were not based on an explicit systematic review of the literature (SOR: C, based on expert opinion; see TABLE 1).

Reduced monitoring for most patients with Barrett’s esophagus appears safe

Paul Crawford, MD

USAF–Eglin Family Practice Residency, Eglin Air Force Base, Fla

Family physicians have long been at the mercy of expert opinion when considering how to monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus. This review of the evidence clearly shows that the days of yearly EGD for all Barrett’s esophagus patients are over.

Unlike other conditions—such as cervical dysplasia, where monitoring and therapies to remove dysplasia are proven to save lives—Barrett’s esophagus progresses slowly and unpredictably. Thus, until technological advances allow identification of higher risk Barrett’s esophagus patients, an EGD every 3 years for those without dysplasia seems to be a reasonable monitoring interval. Perhaps most importantly, family physicians can reassure Barrett’s esophagus patients in the community that they are likely to live a normal lifespan and die of something other than esophageal cancer.

Evidence summary

Barrett’s esophagus has been defined as “a change in the esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus.”1 Intestinal metaplasia is a premalignant lesion for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Surveillance by serial endoscopy with biopsy has been recommended in an effort to find high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in an early, asymptomatic, and potentially curable stage.1-4 Approximately 75% of patients involved in a Barrett’s esophagus surveillance program will present with resectable tumors, compared with only 25% of those not receiving surveillance.4

A recent systematic review assessing screening tools for esophageal carcinoma found standard endoscopy to be superior (90%–100% sensitivity) to other less invasive methods such as questionnaire (60%–70%), and fecal occult blood testing (20%).4 Additional endoscopy tools such as brush and balloon cytology increased the cost of surveillance without any improvement in diagnostic yield.

The degree of dysplasia on esophageal biopsy in Barrett’s esophagus patients is currently the best indicator of risk of progression to esophageal carcinoma. The data reviewed by the ACG for the practice guideline was drawn from several prospective studies and one available registry. In sum, a total of 783 Barrett’s esophagus patients were followed for a mean of 2.9 to 7.3 years. Esophageal carcinoma developed in 2% of patients with no dysplasia, 7% of patients with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and 22% of patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD).1 The ACG recommendations regarding frequency of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were not based on an explicit critical appraisal of the literature. Recent cohort studies are consistent with recommendations for graded surveillance frequency. A randomized clinical trial to determine optimal endoscopic frequency and benefit has not been reported.

Several concerns have been raised regarding the utility of degree of dysplasia in determining optimal frequency of endoscopic surveillance. First, the progression of esophageal lesions over time is unpredictable. Skacel et al5 reported a series of 34 patients with LGD at initial pathologic examination. On subsequent surveillance endoscopy with repeat biopsy, 73% no longer demonstrated dysplasia. Such patients can be allowed to return to having surveillance every 3 years.

In addition to the non-linear progression of dysplasia, inter-rater reliability of the interpretation of pathology specimens varies substantially. Adequate reliability has been demonstrated among pathologists assigning results to 2 categories (either no dysplasia and LGD or HGD and carcinoma) (κ=0.7). Assignment to four distinct pathologic grades, however, was not reliable (κ=0.46, where 1.0 is complete agreement).1 In order to make a diagnosis of HGD or carcinoma, interpretation must be independently confirmed by 2 expert pathologists.1-3

Recommendations for frequent endoscopic surveillance are also weakened by the overall low rate of mortality from esophageal carcinoma noted in Barrett’s esophagus patients. A recent population based study demonstrated that there was no difference in overall mortality in those with a Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis compared with the general population.6 An increased risk of death from esophageal carcinoma was seen in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (4.7% seen in Barrett’s esophagus patients compared with 0.8% predicted in the general population; P<.05). The overall increased effect on mortality, however, was relatively small. Esophageal carcinoma accounted for less then 5% of deaths in Barrett’s esophagus patients reported during the study’s 6-year follow-up period.

Data from prospective studies published after 2002 may better predict prognosis for Barrett’s esophagus patients.6-9 Even lower rates of progression to esophageal carcinoma (<0.5% a year or <1/220 patient-years) have been reported in these studies drawing from the general population rather than referred patients, likely stemming from differences in gender mix, patient age, and risk factors.

In addition to grade of dysplasia, the length of the dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus segment is emerging as a potentially predictive risk factor. While the ACG cautions that esophageal cancer has been reported in patients with so-called “short segment” Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE) (≤3 cm),1 recent prospective studies have shown an increased risk of carcinoma development with long segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE).7-9 Weston et al7 reported a 2.4% progression rate to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with SSBE and no dysplasia compared with 6.8% with LSBE (P=.002). If patients had LGD, the rate of progression to esophageal carcinoma with SSBE was 5.3% and jumped to 35% in patients with LSBE (P<.001). Conio et al8 reported that 4 of 5 cases of esophageal carcinoma noted through surveillance had LSBE. Hage et al9 reported a significantly increased risk of progression to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with long segment disease (P<.02).

While currently still considered investigational, DNA content flow cytometry may be a future tool used in risk stratification. Reid et al10 report a 5-year cumulative risk of esophageal carcinoma of 1.7% in Barrett’s esophagus patients with negative, low-grade or indefinite grades of dysplasia. Subsequent application of flow cytometry allowed for further stratification of these low-risk patients. Those with neither aneuploidy nor an increased 4N had a 5-year cumulative risk of cancer of 0% while the risk for those with abnormalities on cytometry increased to 28% (relative risk=19; P<.001).

TABLE

Grade of dysplasia and recommendations for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance as proposed by the ACG

| DYSPLASIA | DOCUMENTATION | FOLLOW-UP ENDOSCOPY |

|---|---|---|

| None | Two EGDs with biopsy | 3 years |

| Low-grade | Highest grade on repeat | 1 year until no dysplasia |

| High-grade | Repeat EGD with biopsy to rule out cancer/document high-grade dysplasia; expert pathologist confirmation | Focal: every 3 months |

| Multifocal: intervention | ||

| Mucosal irregularity: EMR | ||

| ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection. Intervention: ie, esophagectomy. Ablative therapies only in the setting of a clinical trial or for those unable to tolerate surgery. | ||

Recommendations from others

The French Society of Digestive Endoscopy has published guidelines on monitoring Barrett’s esophagus.3 Their recommendations differ only slightly from the ACG in advocating a slightly increased frequency of EGD surveillance based on degree of dysplasia, and utilizing the length of the dysplastic segment in decision-making. Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the US Preventive Services Task Force make any specific recommendations about Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

Some patients who have been diagnosed with Barrett’s esophagus will develop dysplasia and, in some cases, esophageal carcinoma (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, based on consistent cohort studies). Endoscopic surveillance is recommended for all patients with Barrett’s esophagus as it is superior to other methods for detecting esophageal cancer (SOR: B, based on systematic review). The degree of dysplasia noted on biopsy specimens correlates with the risk of esophageal carcinoma development and should guide the frequency of subsequent evaluations (SOR: B, based on consistent cohort studies). The optimal frequency of endoscopy has yet to be determined in any randomized trial.

Recommendations from the 2002 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) Practice Guideline provide guidance as to the frequency of endoscopy surveillance but were not based on an explicit systematic review of the literature (SOR: C, based on expert opinion; see TABLE 1).

Reduced monitoring for most patients with Barrett’s esophagus appears safe

Paul Crawford, MD

USAF–Eglin Family Practice Residency, Eglin Air Force Base, Fla

Family physicians have long been at the mercy of expert opinion when considering how to monitor patients with Barrett’s esophagus. This review of the evidence clearly shows that the days of yearly EGD for all Barrett’s esophagus patients are over.

Unlike other conditions—such as cervical dysplasia, where monitoring and therapies to remove dysplasia are proven to save lives—Barrett’s esophagus progresses slowly and unpredictably. Thus, until technological advances allow identification of higher risk Barrett’s esophagus patients, an EGD every 3 years for those without dysplasia seems to be a reasonable monitoring interval. Perhaps most importantly, family physicians can reassure Barrett’s esophagus patients in the community that they are likely to live a normal lifespan and die of something other than esophageal cancer.

Evidence summary

Barrett’s esophagus has been defined as “a change in the esophageal epithelium of any length that can be recognized at endoscopy and is confirmed to have intestinal metaplasia by biopsy of the tubular esophagus.”1 Intestinal metaplasia is a premalignant lesion for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Surveillance by serial endoscopy with biopsy has been recommended in an effort to find high-grade dysplasia or carcinoma in an early, asymptomatic, and potentially curable stage.1-4 Approximately 75% of patients involved in a Barrett’s esophagus surveillance program will present with resectable tumors, compared with only 25% of those not receiving surveillance.4

A recent systematic review assessing screening tools for esophageal carcinoma found standard endoscopy to be superior (90%–100% sensitivity) to other less invasive methods such as questionnaire (60%–70%), and fecal occult blood testing (20%).4 Additional endoscopy tools such as brush and balloon cytology increased the cost of surveillance without any improvement in diagnostic yield.

The degree of dysplasia on esophageal biopsy in Barrett’s esophagus patients is currently the best indicator of risk of progression to esophageal carcinoma. The data reviewed by the ACG for the practice guideline was drawn from several prospective studies and one available registry. In sum, a total of 783 Barrett’s esophagus patients were followed for a mean of 2.9 to 7.3 years. Esophageal carcinoma developed in 2% of patients with no dysplasia, 7% of patients with low-grade dysplasia (LGD) and 22% of patients with high-grade dysplasia (HGD).1 The ACG recommendations regarding frequency of esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) were not based on an explicit critical appraisal of the literature. Recent cohort studies are consistent with recommendations for graded surveillance frequency. A randomized clinical trial to determine optimal endoscopic frequency and benefit has not been reported.

Several concerns have been raised regarding the utility of degree of dysplasia in determining optimal frequency of endoscopic surveillance. First, the progression of esophageal lesions over time is unpredictable. Skacel et al5 reported a series of 34 patients with LGD at initial pathologic examination. On subsequent surveillance endoscopy with repeat biopsy, 73% no longer demonstrated dysplasia. Such patients can be allowed to return to having surveillance every 3 years.

In addition to the non-linear progression of dysplasia, inter-rater reliability of the interpretation of pathology specimens varies substantially. Adequate reliability has been demonstrated among pathologists assigning results to 2 categories (either no dysplasia and LGD or HGD and carcinoma) (κ=0.7). Assignment to four distinct pathologic grades, however, was not reliable (κ=0.46, where 1.0 is complete agreement).1 In order to make a diagnosis of HGD or carcinoma, interpretation must be independently confirmed by 2 expert pathologists.1-3

Recommendations for frequent endoscopic surveillance are also weakened by the overall low rate of mortality from esophageal carcinoma noted in Barrett’s esophagus patients. A recent population based study demonstrated that there was no difference in overall mortality in those with a Barrett’s esophagus diagnosis compared with the general population.6 An increased risk of death from esophageal carcinoma was seen in patients with Barrett’s esophagus (4.7% seen in Barrett’s esophagus patients compared with 0.8% predicted in the general population; P<.05). The overall increased effect on mortality, however, was relatively small. Esophageal carcinoma accounted for less then 5% of deaths in Barrett’s esophagus patients reported during the study’s 6-year follow-up period.

Data from prospective studies published after 2002 may better predict prognosis for Barrett’s esophagus patients.6-9 Even lower rates of progression to esophageal carcinoma (<0.5% a year or <1/220 patient-years) have been reported in these studies drawing from the general population rather than referred patients, likely stemming from differences in gender mix, patient age, and risk factors.

In addition to grade of dysplasia, the length of the dysplastic Barrett’s esophagus segment is emerging as a potentially predictive risk factor. While the ACG cautions that esophageal cancer has been reported in patients with so-called “short segment” Barrett’s esophagus (SSBE) (≤3 cm),1 recent prospective studies have shown an increased risk of carcinoma development with long segment Barrett’s esophagus (LSBE).7-9 Weston et al7 reported a 2.4% progression rate to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with SSBE and no dysplasia compared with 6.8% with LSBE (P=.002). If patients had LGD, the rate of progression to esophageal carcinoma with SSBE was 5.3% and jumped to 35% in patients with LSBE (P<.001). Conio et al8 reported that 4 of 5 cases of esophageal carcinoma noted through surveillance had LSBE. Hage et al9 reported a significantly increased risk of progression to HGD or esophageal carcinoma with long segment disease (P<.02).

While currently still considered investigational, DNA content flow cytometry may be a future tool used in risk stratification. Reid et al10 report a 5-year cumulative risk of esophageal carcinoma of 1.7% in Barrett’s esophagus patients with negative, low-grade or indefinite grades of dysplasia. Subsequent application of flow cytometry allowed for further stratification of these low-risk patients. Those with neither aneuploidy nor an increased 4N had a 5-year cumulative risk of cancer of 0% while the risk for those with abnormalities on cytometry increased to 28% (relative risk=19; P<.001).

TABLE

Grade of dysplasia and recommendations for Barrett’s esophagus surveillance as proposed by the ACG

| DYSPLASIA | DOCUMENTATION | FOLLOW-UP ENDOSCOPY |

|---|---|---|

| None | Two EGDs with biopsy | 3 years |

| Low-grade | Highest grade on repeat | 1 year until no dysplasia |

| High-grade | Repeat EGD with biopsy to rule out cancer/document high-grade dysplasia; expert pathologist confirmation | Focal: every 3 months |

| Multifocal: intervention | ||

| Mucosal irregularity: EMR | ||

| ACG, American College of Gastroenterology; EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy; EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection. Intervention: ie, esophagectomy. Ablative therapies only in the setting of a clinical trial or for those unable to tolerate surgery. | ||

Recommendations from others

The French Society of Digestive Endoscopy has published guidelines on monitoring Barrett’s esophagus.3 Their recommendations differ only slightly from the ACG in advocating a slightly increased frequency of EGD surveillance based on degree of dysplasia, and utilizing the length of the dysplastic segment in decision-making. Neither the American Academy of Family Physicians nor the US Preventive Services Task Force make any specific recommendations about Barrett’s esophagus surveillance.

1. Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1888-1895.

2. Management of Barrett’s esophagus. The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT), American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Consensus Panel. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:115-116.

3. Boyer J, Robaszkiewicz M. Guidelines of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy: Monitoring of Barrett’s esophagus. The Council of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy. Endoscopy 2000;32:498-499.

4. Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma: an evidence-based approach. Am J Med 2002;113:499-505.

5. Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, et al. The diagnosis of low grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3383-3387.

6. Anderson LA, Murray LJ, Murphy SJ, et al. Mortality in Barrett’s oesophagus: results from a population based study. Gut 2003;52:1081-1084.

7. Weston AP, Sharma P, Mathur S, et al. Risk stratification of barrett’s esophagus: updated prospective multivariate analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1657-1666.

8. Conio M, Blanchi S, Laertosa G, et al. Long-term endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1931-1939.

9. Hage M, Siersema PD, van Dekken H, Steyerber EW, Dees J, Kuipers EJ. Oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus after a mean follow-up of 12.7 years. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1175-1179.

10. Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, Blount P, Rabinovitch PS. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1669-1676.

1. Sampliner RE. Updated guidelines for the diagnosis, surveillance, and therapy of Barrett’s esophagus. Am J Gastroenterol 2002;97:1888-1895.

2. Management of Barrett’s esophagus. The Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract (SSAT), American Gastroenterological Association (AGA), American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) Consensus Panel. J Gastrointest Surg 2000;4:115-116.

3. Boyer J, Robaszkiewicz M. Guidelines of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy: Monitoring of Barrett’s esophagus. The Council of the French Society of Digestive Endoscopy. Endoscopy 2000;32:498-499.

4. Gerson LB, Triadafilopoulos G. Screening for esophageal adenocarcinoma: an evidence-based approach. Am J Med 2002;113:499-505.

5. Skacel M, Petras RE, Gramlich TL, et al. The diagnosis of low grade dysplasia in Barrett’s esophagus and its implications for disease progression. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:3383-3387.

6. Anderson LA, Murray LJ, Murphy SJ, et al. Mortality in Barrett’s oesophagus: results from a population based study. Gut 2003;52:1081-1084.

7. Weston AP, Sharma P, Mathur S, et al. Risk stratification of barrett’s esophagus: updated prospective multivariate analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:1657-1666.

8. Conio M, Blanchi S, Laertosa G, et al. Long-term endoscopic surveillance of patients with Barrett’s esophagus. Incidence of dysplasia and adenocarcinoma: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2003;98:1931-1939.

9. Hage M, Siersema PD, van Dekken H, Steyerber EW, Dees J, Kuipers EJ. Oesophageal cancer incidence and mortality in patients with long-segment Barrett’s oesophagus after a mean follow-up of 12.7 years. Scand J Gastroenterol 2004;39:1175-1179.

10. Reid BJ, Levine DS, Longton G, Blount P, Rabinovitch PS. Predictors of progression to cancer in Barrett’s esophagus: baseline histology and flow cytometry identify low- and high-risk patient subsets. Am J Gastroenterol 2000;95:1669-1676.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

What is the best way to manage benign paroxysmal positional vertigo?

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

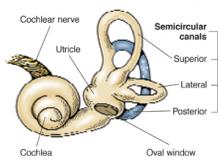

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

A simple repositioning maneuver, such as the Epley maneuver (Figures 1 and 2 ), performed by an experienced clinician, can provide symptom relief from benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) lasting at least 1 month (strength of recommendation [SOR]: A, systematic review of randomized controlled trials). Medical therapy with benzodiazepines for vestibular suppression provides no proven benefit for BPPV (SOR: B, 1 small randomized controlled trial). For undifferentiated dizziness, vestibular rehabilitation may provide symptomatic relief (SOR: B, 1 randomized controlled trial).

FIGURE 1

Cause of BPPVE

FIGURE 2

Pley maneuver for BPPV

BPPV is characterized by brief, self-limited episodes of vertigo, provoked by typical position changes. This condition may result from free-floating debris in the endolymph of the posterior semicircular canal. This debris moves with position change, causing an abnormal perception of movement and classic symptoms of vertigo. Dix-Hallpike testing aids in the diagnosis, but treatment is often prescribed empirically.1

The most widely studied treatments for BPPV are the single-treatment repositioning techniques, such as the Epley maneuver.2A Cochrane review of treatments for BPPV yielded 11 trials, of which 9 were excluded due to a high risk of bias.3 The 2 remaining trials compared the Epley maneuver with a sham procedure among 86 patients referred to specialty care.4,5 Outcomes included conversion of the Dix-Hallpike test from positive to negative, as well as resolution of symptoms by patient report. Assessment occurred 1–4 weeks following the intervention in the 2 trials.4,5 Pooled data yielded odds ratios in favor of treatment for both objective testing (OR=5.67; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.21–14.56) and symptom resolution (OR=4.92; 95% CI, 1.84–13.16), with no adverse outcomes reported.3We found no trials comparing the Epley maneuver with either vestibular habituation therapy or surgical management of BPPV.

There is no direct evidence for vestibular rehabilitation in BPPV. In a trial of vestibular rehabilitation for prolonged, undifferentiated dizziness, patients were randomized to usual care (n=76) or treatment with two 30-minute home education sessions at baseline and 6 weeks (n=67). A nurse, who had received 2 weeks of training, led the sessions, which included basic education on the vestibular system, causes of dizziness, and the rationale for exercise therapy. The nurse then taught the patients 8 sets of standard head and body movements to be performed twice daily. At 6 months, 69% of the treatment group vs 37% of the control group reported subjective improvement (OR=3.8 at 6 months; 95% CI, 1.6–8.7).6

Lorazepam and diazepam had no effect in 1 small randomized controlled trial.7 In this study, 25 BPPV patients from specialty clinics were randomized to placebo, diazepam 5 mg, or lorazepam 1 mg 3 times daily for 4 weeks. Patients reported dizziness on a 10-point scale at baseline and after 4 weeks of therapy. Nystagmus severity was also assessed using a 10-point scale at baseline and within 2 days following completion of treatment. The authors found no significant difference between the treatment and placebo arms; however, the study may have been underpowered to detect a clinically significant difference.

Recommendations from others

The Vestibular Disorders Association recommends the Epley maneuver as first-line treatment for BPPV, as does the Mayo Clinic.8,9 The National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders suggests that vestibular rehabilitation may be useful as a treatment for dizziness depending on the cause.10

Use otolith repositioning maneuvers

Grant Hoekzema, MD

Mercy Family Medicine Residency, St. Louis, MO

Although BPPV has a benign long-term outcome, it can be quite bothersome to patients and I have always felt compelled to offer some trial of therapy. Given the overall success and the relative safety of otolith repositioning maneuvers, such as the Epley maneuver, it has become my practice to refer patients to a physical therapist or other provider trained in these techniques. This makes sense from a pathophysiologic standpoint as well. I reserve antihistamines, such as meclizine, for those patients who have frequent, daily symptoms and who have not benefited from otolith repositioning.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

1. Dix MR, Hallpike CS. Pathology, symptomatology and diagnosis of certain common disorders of the vestibular system. Proc Roy Soc Med 1952;45:341-354.

2. Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1992;107:399-404.

3. Hilton M, Pinder D. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 3, 2003. Oxford: Update Software, last updated October 25, 2001.

4. Lynn S, Pool A, Rose D, Brey R, Suman V. Randomized trial of the canalith repositioning procedure. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;113:712-720.

5. Froehling DA, Bowen JM, Mohr DN, et al. The canalith repositioning procedure for the treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc 2000;75:695-700.

6. Yardley L, Beech S, Zander L, Evans T, Weinman J. A randomized controlled trial of exercise therapy for dizziness and vertigo in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 1998;48:1136-1140.

7. McClure JA, Willett JM. Lorazepam and diazepam in the treatment of benign paroxysmal vertigo. J Otolaryngol 1980;9:472-477.

8. Mayo Clinic website. Vestibular rehabilitation. Available at www.mayoclinic.org/balance-rst/vestrehab.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

9. Vestibular Disorders Association (VEDA) website. Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo (BPPV). March 1995 (modified April 17, 2003). Available at www.vestibular.org/bppv.html. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

10. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Balance disorders. Available at www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/balance/balance_disorders.asp. Accessed on October 8, 2003.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network

Benefits of tamoxifen for breast cancer prevention do not always outweigh overall risks

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Results have been mixed from 3 previous clinical trials of the use of tamoxifen for preventing breast cancer in high-risk women. A recently updated analysis from 1 negative study showed a decrease in the incidence of estrogen-receptor–positive breast cancer, adding support for the effectiveness of tamoxifen in some high-risk women. Tamoxifen therapy, however, is associated with significant adverse outcomes that may outweigh any benefits.

POPULATION STUDIED: Recruitment took place among outpatients at breast screening centers, primary care offices, and family history clinics. The media and contact of relatives of women with breast cancer provided additional recruitment. Women aged 35 to 70 years met criteria for entry if their risk for developing breast cancer was at least double that for women between 45 and 70 years, at least 4-fold that for women between 40 and 44 years, and 10-fold that for women aged 35 to 39 years. Risk was determined by an unpublished alternative to the Gail model. Patients were excluded if they had current or desired pregnancy, previous invasive cancer, previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, current use of anticoagulant agents, or a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: In this randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial, eligible women were randomized to receive either 20 mg tamoxifen (N=3573) or a matched placebo (N=3566) daily for 5 years. Thirteen women with findings on mammogram at the time of randomization were excluded from subsequent analysis. Participants received clinical evaluations every 6 months during the 5-year active treatment interval. Follow-up continued for up to 5 years beyond treatment by annual questionnaire or clinical visit. Symptoms, side effects, diagnoses, procedures, and concomitant medications were recorded at each evaluation. A mammogram was performed every 12 to 18 months. External reviewers, masked to treatment allocation, evaluated all end points and deaths.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measure was the frequency of breast cancer including ductal carcinoma in situ. Secondary outcomes included side effects, thromboembolic events, procedures, and deaths.

RESULTS: Women given tamoxifen had fewer breast cancers (n=60, 1.9%) than individuals given placebo (n=101, 2.8%; numbers needed to treat=112 for 5 years of treatment). As expected, prevention occurred at a cost of a greater incidence of venous thromboembolic events (1.2% vs 0.5%; numbers needed to harm [NNH]=137 for 5 years of treatment) and symptoms such as hot flashes and breast tenderness, and procedures including dilation and curettage and hysterectomy. More importantly, significantly more women on tamoxifen (n=25, 0.7%) died as compared with those on placebo (n=11, 0.3%; NNH=256 for 5 years of treatment).

In women at high risk of breast cancer, tamoxifen is effective in reducing the incidence of the disease. The intervention, however, is associated with significant risk. During the 5-year period of this study, although the number of breast cancers was reduced, the number of serious adverse effects and deaths were higher in the treated group. Women at a lower risk of breast cancer than those studied would be even less likely to benefit from tamoxifen while risking the same serious adverse outcomes. For the small proportion of women with a high risk of breast cancer and a low risk of adverse events, discussion of this intervention may be warranted.

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND: Results have been mixed from 3 previous clinical trials of the use of tamoxifen for preventing breast cancer in high-risk women. A recently updated analysis from 1 negative study showed a decrease in the incidence of estrogen-receptor–positive breast cancer, adding support for the effectiveness of tamoxifen in some high-risk women. Tamoxifen therapy, however, is associated with significant adverse outcomes that may outweigh any benefits.

POPULATION STUDIED: Recruitment took place among outpatients at breast screening centers, primary care offices, and family history clinics. The media and contact of relatives of women with breast cancer provided additional recruitment. Women aged 35 to 70 years met criteria for entry if their risk for developing breast cancer was at least double that for women between 45 and 70 years, at least 4-fold that for women between 40 and 44 years, and 10-fold that for women aged 35 to 39 years. Risk was determined by an unpublished alternative to the Gail model. Patients were excluded if they had current or desired pregnancy, previous invasive cancer, previous deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism, current use of anticoagulant agents, or a life expectancy of less than 10 years.

STUDY DESIGN AND VALIDITY: In this randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial, eligible women were randomized to receive either 20 mg tamoxifen (N=3573) or a matched placebo (N=3566) daily for 5 years. Thirteen women with findings on mammogram at the time of randomization were excluded from subsequent analysis. Participants received clinical evaluations every 6 months during the 5-year active treatment interval. Follow-up continued for up to 5 years beyond treatment by annual questionnaire or clinical visit. Symptoms, side effects, diagnoses, procedures, and concomitant medications were recorded at each evaluation. A mammogram was performed every 12 to 18 months. External reviewers, masked to treatment allocation, evaluated all end points and deaths.

OUTCOMES MEASURED: The primary outcome measure was the frequency of breast cancer including ductal carcinoma in situ. Secondary outcomes included side effects, thromboembolic events, procedures, and deaths.

RESULTS: Women given tamoxifen had fewer breast cancers (n=60, 1.9%) than individuals given placebo (n=101, 2.8%; numbers needed to treat=112 for 5 years of treatment). As expected, prevention occurred at a cost of a greater incidence of venous thromboembolic events (1.2% vs 0.5%; numbers needed to harm [NNH]=137 for 5 years of treatment) and symptoms such as hot flashes and breast tenderness, and procedures including dilation and curettage and hysterectomy. More importantly, significantly more women on tamoxifen (n=25, 0.7%) died as compared with those on placebo (n=11, 0.3%; NNH=256 for 5 years of treatment).

In women at high risk of breast cancer, tamoxifen is effective in reducing the incidence of the disease. The intervention, however, is associated with significant risk. During the 5-year period of this study, although the number of breast cancers was reduced, the number of serious adverse effects and deaths were higher in the treated group. Women at a lower risk of breast cancer than those studied would be even less likely to benefit from tamoxifen while risking the same serious adverse outcomes. For the small proportion of women with a high risk of breast cancer and a low risk of adverse events, discussion of this intervention may be warranted.

ABSTRACT