User login

Helping patients quit smoking: Lessons from the EAGLES trial

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

Psychiatrists often fail to adequately address their patients’ smoking, and often underestimate the impact of ongoing tobacco use. Evidence suggests that heavy smoking is a risk factor for major depressive disorder; it also is associated with increased suicidal ideations and attempts.1,2 Tobacco use also has a mood-altering impact that can change the trajectory of mental illness, and alters the metabolism of most psychotropics.

Previously, psychiatrists may have been reluctant to prescribe the most effective interventions for smoking cessation—varenicline and bupropion—because these medications carried an FDA “black-box” warning of neuropsychiatric adverse effects, including increased aggression and suicidality. However,

The EAGLES trial was a large, multi-site global trial that included patients with and without mental illness. Its primary objective was to assess the risk of “clinically significant” adverse effects for individuals receiving varenicline, bupropion, nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), or placebo, and whether having a history of psychiatric conditions increased the risk of developing adverse effects when taking these therapies. Overall, 2% of smokers without mental illness experienced adverse effects, compared with 5% to 7% in the psychiatric cohort, regardless of treatment arm. The rate of neuropsychiatric events and scores on suicide severity scales were similar across treatment arms in both cohorts.3

We should take lessons from the EAGLES trial. We propose that clinicians ask themselves the following 6 questions when forming a treatment plan to address their patients’ tobacco use:

1. Does the patient meet DSM-5 criteria for nicotine use disorder and, if yes, what is the severity of his or her nicotine dependence? The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND)5 is a 6-question instrument for evaluating the quantity of cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence. It provides clinicians with guidelines on preventing withdrawal by implementing NRTs, such as lozenges, an inhaler, patches, and/or gum. A score of 1 to 2 (low dependence) indicates that no NRT is needed; a score of 3 to 4 (low to moderate dependence) requires 1 NRT; and scores of 5 to 7 (moderate dependence) and ≥8 (high dependence) require a combination of NRTs.

In the EAGLES trial, all participants smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day, and had moderate dependence, with an average FTND score of 5 to 6.

2. What stage of change is the patient in, and how many times has he or she attempted to quit? Based on the answers, motivational interviewing may be appropriate.

Continue to: In the EAGLES trial...

In the EAGLES trial, the participants were motivated individuals who had on average 3 past quit attempts. Research suggests that even patients who have a serious mental illness can be motivated to quit (Box).6-9

Box

Mental illness and motivation to quit smoking

In the past, clinicians may have believed that many individuals with mental illness typically weren’t motivated to quit smoking. We now know this is not the case and that such patients’ motivation is similar to that of the general population, and the reasons driving their desire are the same—health concerns and social influences.6 Even individuals with serious mental illness such as schizophrenia who have a long history of tobacco use are highly motivated and persistent in their attempts to quit.7,8 The prevalence of future “readiness to quit” among individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia and depression ranges from 21% to 49%, which is similar to that among the general population (26% to 41%). Evidence also suggests that motivation translates into successful quitting, with quit rates of up to 22% for people with mental illness who use a combination of psychosocial and pharmacological interventions.9

3. What is the patient’s mental health status? What is the patient’s psychiatric diagnosis and how clinically stable is he or she? What is his or her suicide risk? Consider using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS).10

In the EAGLES trial, the psychiatric cohort included only patients who had been clinically stable for the past 6 months and had received the same medication regimen for at least the past 3 months, with no expected changes for 12 weeks. Patients with certain diagnoses were excluded (eg, delusional disorder, schizophreniform disorder, impulse control disorders), and only 1% had a personality disorder, which increases mood lability and likelihood of suicidality behavior.

Continue to: Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder?

4. Does the patient have another comorbid substance use disorder? In the EAGLES trial, those who had active substance use in the past year or were receiving methadone or buprenorphine/naloxone were excluded.

5. Does the patient have any medical conditions? Does he or she have a history of seizures or eating disorders? It is important to determine if a patient has a seizure disorder or another medical condition that is a contraindication for using varenicline or bupropion.

I

6. Have you discussed smoking cessation and a treatment plan with the patient at every visit? In the EAGLES trial, participants received 10-minute cessation counseling at every outpatient visit.

Continue to: When it comes time to select a medication regimen...

When it comes time to select a medication regimen, for bupropion, consider starting the patient with 150 mg/d, and increasing the dose to 150 mg twice a day 4 days later. The target quit date should be 7 days after starting the medication. Monitor the patient for symptoms of anxiety and insomnia.

For varenicline, start the patient at 0.5 mg/d, and increase the dose to 0.5 mg twice a day 4 days later. After another 4 days, increase the dose to 1 mg twice a day. Set a target quit date for 7 days after starting medication. Monitor the patient for nausea, insomnia, and abnormal dreams.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

1. Khaled SM, Bulloch AG, Williams JV, et al. Persistent heavy smoking as risk factor for major depression (MD) incidence--evidence from a longitudinal Canadian cohort of the National Population Health Survey. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(4):436-443.

2. Han B, Compton WM, Blanco C. Tobacco use and 12-month suicidality among adults in the United States. Nicotine Tob Res. 2017;19(1):39-48.

3. Anthenelli RM, Benowitz NL, West R, et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507-2520.

4. FDA Drug Safety Communication: FDA revises description of mental health side effects of the stop-smoking medicines Chantix (varenicline) and Zyban (bupropion) to reflect clinical trial findings. https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm532221.htm. Accessed April 16, 2018.

5. Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, et al. The Fagerström Test for nicotine dependence: a revision of the Fagerström Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86(9):1119-1127.

6. Moeller‐Saxone K. Cigarette smoking and interest in quitting among consumers at a psychiatric disability rehabilitation and support service in Victoria. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2008;32(5):479-481.

7. Evins AE, Cather C, Rigotti NA, et al. Two-year follow-up of a smoking cessation trial in patients with schizophrenia: increased rates of smoking cessation and reduction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(3):307-311; quiz 452-453.

8. Weiner E, Ahmed S. Smoking cessation in schizophrenia. Cur Psychiatry Rev. 2013;9(2):164-172.

9. Banham L, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental illness: what works? Addiction. 2010;105(7):1176-1189.

10. Posner K, Brent D, Lucas C, et al. Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS). The Research Foundation for Mental Hygiene, Inc. http://cssrs.columbia.edu/wp-content/uploads/C-SSRS_Pediatric-SLC_11.14.16.pdf. Updated June 23, 2010. Accessed April 26, 2018.

Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for the most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

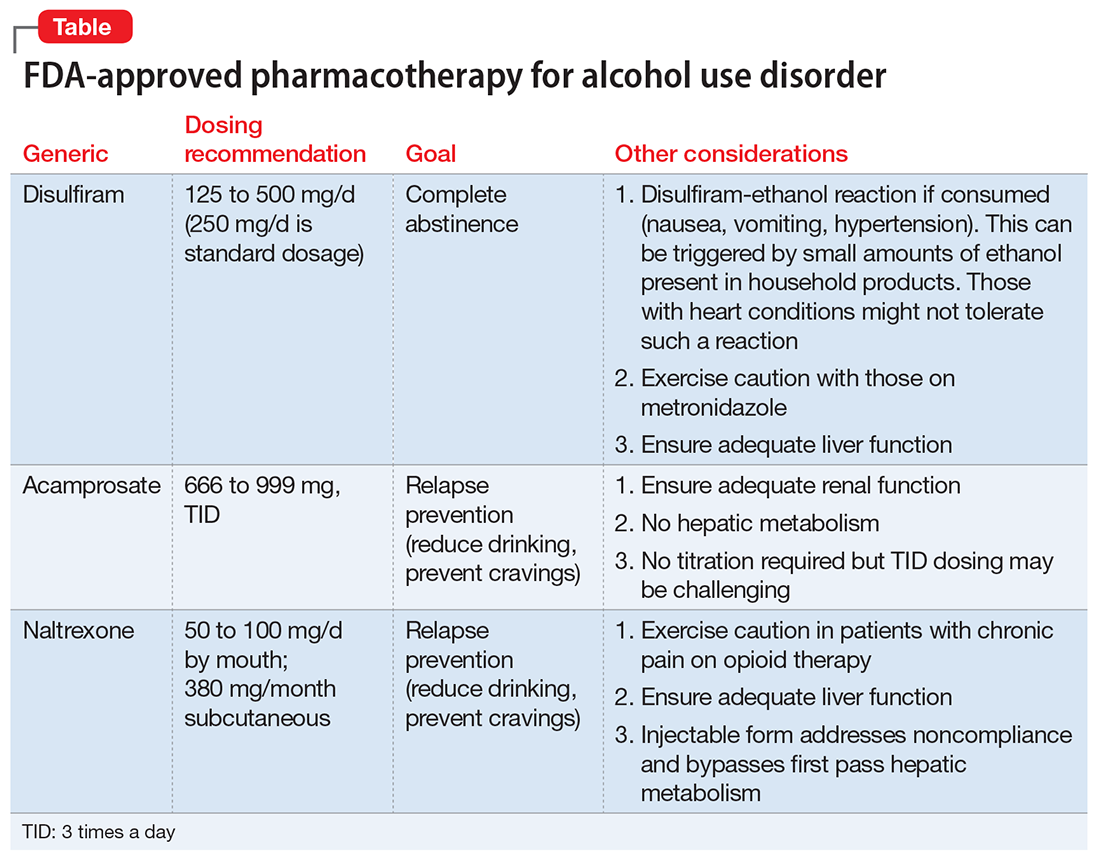

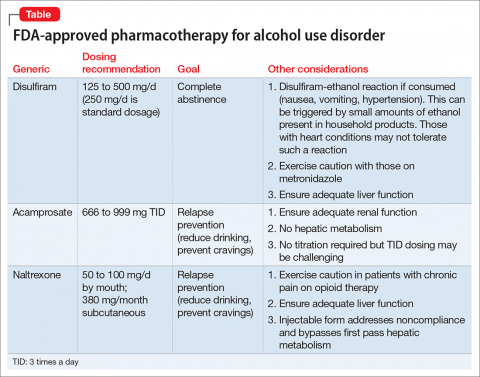

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

In July 2017, Dr. Stanciu will be entering PGY-5 Addiction Psychiatry Fellowship, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and Dr. Gnanasegaram has accepted a Clinical Instructor position, Department of Psychiatric Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, New Hampshire.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for the most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

In July 2017, Dr. Stanciu will be entering PGY-5 Addiction Psychiatry Fellowship, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and Dr. Gnanasegaram has accepted a Clinical Instructor position, Department of Psychiatric Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, New Hampshire.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for the most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

In July 2017, Dr. Stanciu will be entering PGY-5 Addiction Psychiatry Fellowship, Geisel School of Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, New Hampshire, and Dr. Gnanasegaram has accepted a Clinical Instructor position, Department of Psychiatric Medicine, Dartmouth-Hitchcock, New Hampshire.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

There is ample evidence in the medical literature, as well as clinical experience, that patients seeking help for chemical dependency benefit from pharmacotherapy. It is common, however, for physicians, patients, and family to balk at the idea. Even within the psychiatry community, where there should be better understanding of substance use disorders, many practitioners hesitate to employ medications, especially for alcohol use disorder (AUD).

Efficacy for such FDA-approved medications has been demonstrated in well-designed, randomized controlled trials, but many trainees, and even experienced professionals, have never seen these medications used effectively and appropriately. Medication-assisted treatment (MAT) is not an alternative to biopsychosocial approaches but is an augmentation that can (1) help stabilize the patient until he (she) can be educated in relapse prevention skills and (2) allow the brain to rewire and heal until he regains impulse control.

Diverse presentations

Do you remember that patient who often arrived for appointments intoxicated, promising that he plans to cut down? How about the man you saw in the emergency department with an elevated blood alcohol level, who was constantly endorsing suicidal thoughts that subsided when he reached clinical sobriety? What about the college student who often was treated for alcohol poisoning after binge drinking on weekends, but who never considered this behavior problematic? And, how about the elderly woman who was evaluated for anxiety, but had been drinking 4 beers nightly for the past 30 years?

Despite the diverse presentations, these patients all have a chronic disease and we fail them when we do not apply evidence-based medicine to their treatment.

As psychiatrists, we encounter many patients with AUD as a primary or comorbid diagnosis. This is a global problem associated with significant human and financial cost. With 80% of American adolescents having reported using alcohol in the past year, the problem will continue to grow.1 Furthermore, a greater prevalence of AUD is noted in clinical populations undergoing psychiatric treatment.2 Ongoing alcohol abuse complicates the course of medical and psychiatric conditions and incites significant societal exclusion.

Pharmacotherapy is underutilized

Despite an increase in the use of psychotropic medications for treating psychiatric illness, pharmacotherapy for AUD is underutilized: only 3% of patients have received an FDA-approved treatment.2,3 Nearly one-third of adults are affected by AUD during their lifetime, yet only 20% seek help.3 Management today remains limited to episodic, brief inpatient detoxification and psychosocial therapy.

Recovery rates are highest when addiction treatment that monitors abstinence is continuous; yet, for most part, alcohol addiction is treated in discrete episodes upon relapse. Although MAT is recommended by experts for “moderate” and “severe” substance use disorders, practitioners, in general, have demonstrated considerable resistance to using this modality as part of routine practice.4,5 This is regrettable: Regardless of terminology used to describe their condition, these people suffer a potentially fatal disease characterized by high post-treatment recidivism.

Neuroscience supports the brain disease model of addiction, with neuroplasticity changes being made during phases of drug use. Medications are shown to assist in preventing relapse while the brain is healing and normal emotional and decision-making capacities are being restored.6

Why hesitate to use pharmacotherapeutics?

There are diverse pharmacotherapeutic options that can be pursued for treating AUD with minimal disruption to home and work life. Alarmingly, many trainees have never prescribed or even considered such medications. Despite modest effect sizes in randomized controlled trials, efficacy has been demonstrated in reducing relapse rates and overall severity of drinking days.4,5 So, from where does the ambivalence of patients and providers about using these treatments to achieve lasting recovery stem?

Starting MAT certainly requires both parties to be in agreement. A patient might decline medication because of a fear of dependence or because he overestimates his ability to achieve remission on his own. There also may be financial barriers in a current alcohol treatment system that is traditionally non-medically oriented. Prescribers also fail to offer medications because of:

- lack of familiarity with available agents

- absence of guidelines for use

- disbelief that the condition is treatable.

Given that treatment often is based on a 12-step approach, such as Alcoholics Anonymous (AA), providers might hesitate to prescribe medication for an illness that is thought to be managed through psychosocial interventions, such as group and motivational therapy.

Therapeutic options

Choice of medication depends on the prescriber’s comfort level, reputation of the medication, potential side-effect profile, medical contraindications, and affordability; the most important consideration, however, should be the overall goals and expectations of the patient.

There are 4 FDA-approved medications for AUD (Table); many others are off-label. It is advisable to start with an FDA-approved medication such as disulfiram for the motivated patient who has a collaborator and desires complete abstinence; naltrexone for a patient who wants to cut down on intake (a long-acting formulation can be used for poorly adherent patients); and acamprosate for a patient with at least some established sobriety who needs help with post-withdrawal sleep disturbances.

With regard to off-label medications, topiramate has the highest evidence for efficacy. Gabapentin can augment naltrexone and also helps with sleep, anxiety, withdrawal, and cravings.4,5

Psychosocial interventions

Medications are just 1 tool in recovery; patients should be engaged in a program of counseling. Encourage attendance at AA meetings. An up-and-coming concept is the use of smartphone applications to prevent relapse (or even induce remission); apps that provide an accurate blood alcohol tracking systems and integrated psychosocial therapies are in the pipeline. The novel Reddit online forum r/StopDrinking is a 24-hour peer-support community that relies on

fellowship, accountability, monitoring, and anonymity; the forum can compete with

motivational interviewing for efficacy in increasing abstinence and preventing relapse.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.

1. Johnson L, O’Malley P, Miech RA, et al. Monitoring the Future national survey results on drug use, 1975-2015: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/pubs/monographs/mtf-overview2015.pdf. Published February 2016. Accessed January 20, 2016.

2. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: mental health findings, NSDUH Series H-49, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4887. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014.

3. Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, et al. Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72(8):757-766.

4. Robinson S, Meeks TW, Geniza C. Medication for alcohol use disorder: which agents work best. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):22-29.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Medication for the treatment of alcohol use disorder: a brief guide. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4907. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2015.

6. Volkow ND, Koob GF, McLellan AT. Neurobiological advances from the brain disease model of addiction. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(4):363-371.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Thomas M. Penders, MS, MD, Medical Director for Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry at Cape Cod Healthcare, Hyannis, Massachusetts, and Affiliate Professor at East Carolina University, Greenville, North Carolina, for all his guidance, support, and mentorship.