User login

Adult ADHD: A sensible approach to diagnosis and treatment

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is common, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5.29% among children and adolescents and 2.5% among adults.1 DSM-5-TR classifies ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, “a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period [that] typically manifest early in development, often before the child enters school.”2 Because of the expectation that ADHD symptoms emerge early in development, the diagnostic criteria specify that symptoms must have been present prior to age 12 to qualify as ADHD. However, recent years have shown a significant increase in the number of patients being diagnosed with ADHD for the first time in adulthood. One study found that the diagnosis of ADHD among adults in the United States doubled between 2007 and 2016.3

First-line treatment for ADHD is the stimulants methylphenidate and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. In the United States, these medications are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, indicating a high risk for abuse. However, just as ADHD diagnoses among adults have increased, so have prescriptions for stimulants. For example, Olfson et al4 found that stimulant prescriptions among young adults increased by a factor of 10 between 1994 and 2009.

The increased prevalence of adult patients diagnosed with ADHD and taking stimulants frequently places clinicians in a position to consider the validity of existing diagnoses and evaluate new patients with ADHD-related concerns. In this article, we review some of the challenges associated with diagnosing ADHD in adults, discuss the risks of stimulant treatment, and present a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults.

Challenges in diagnosis

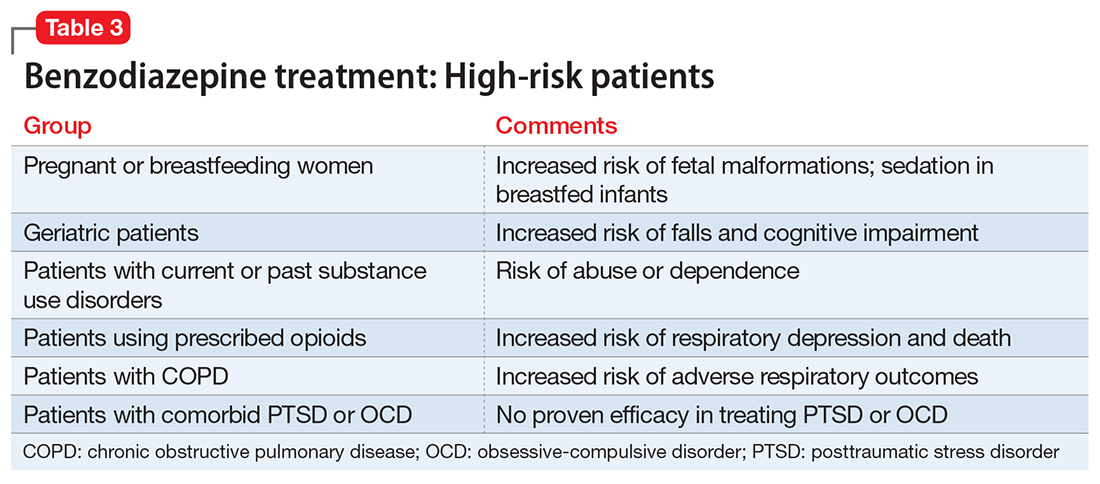

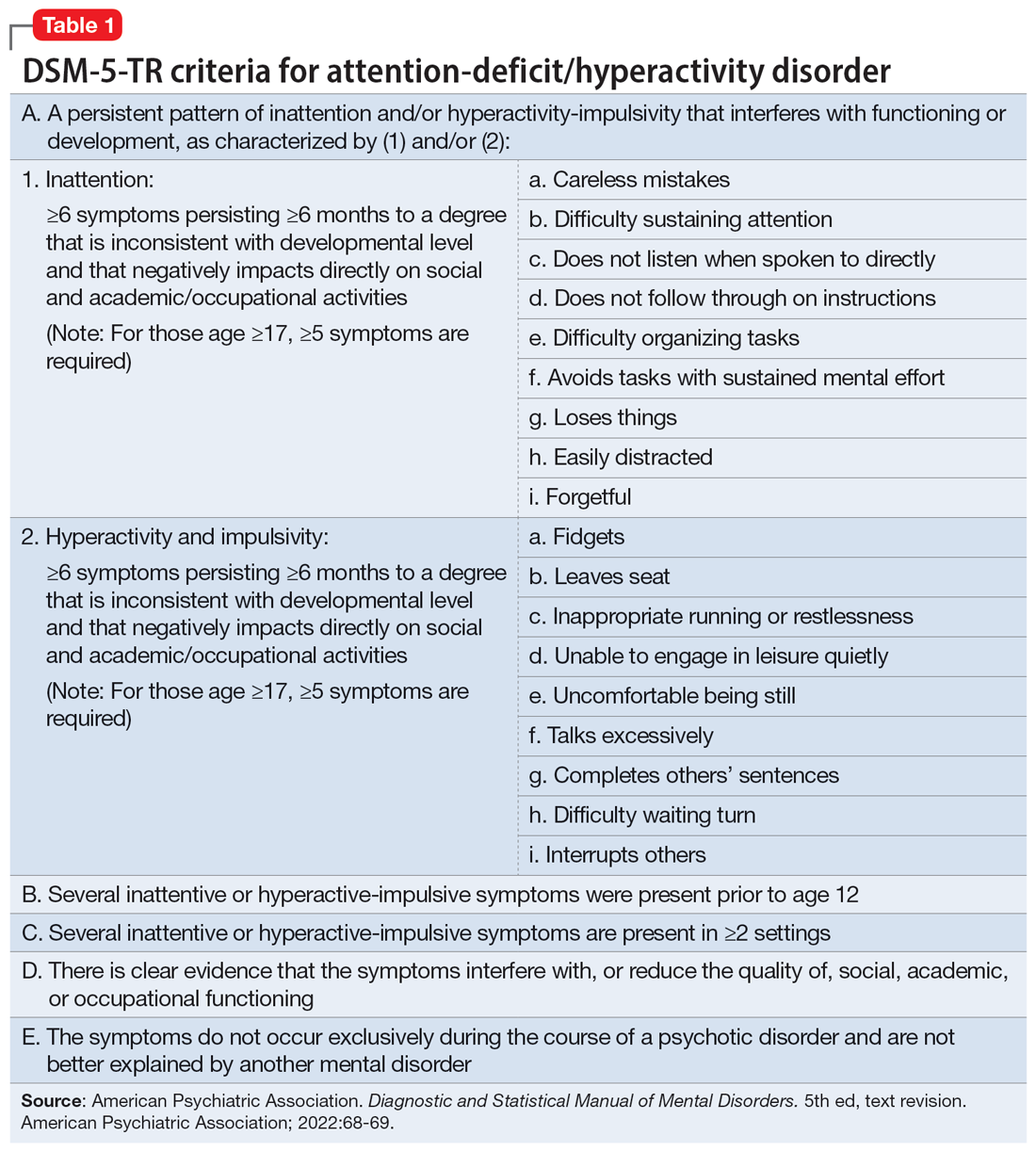

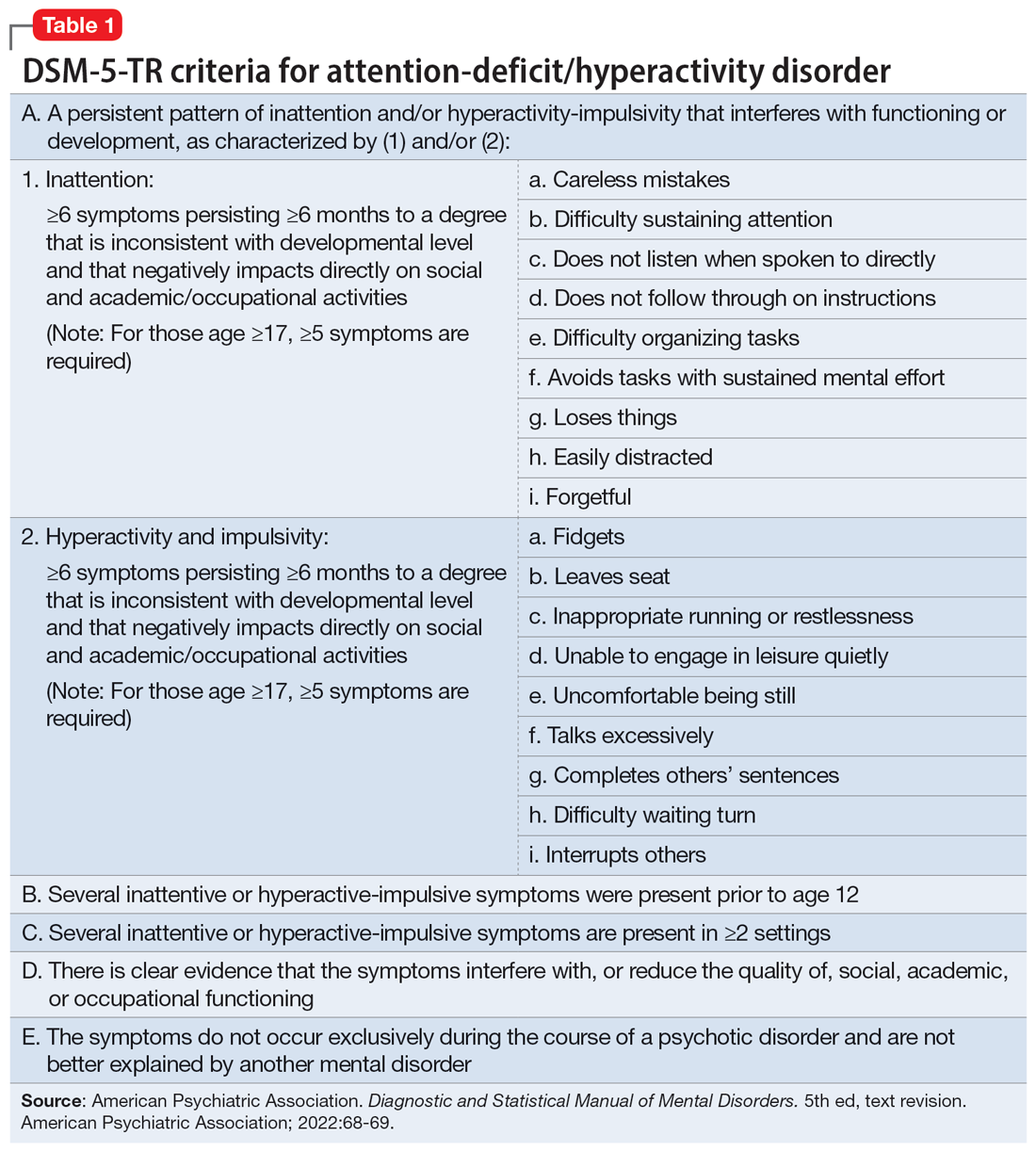

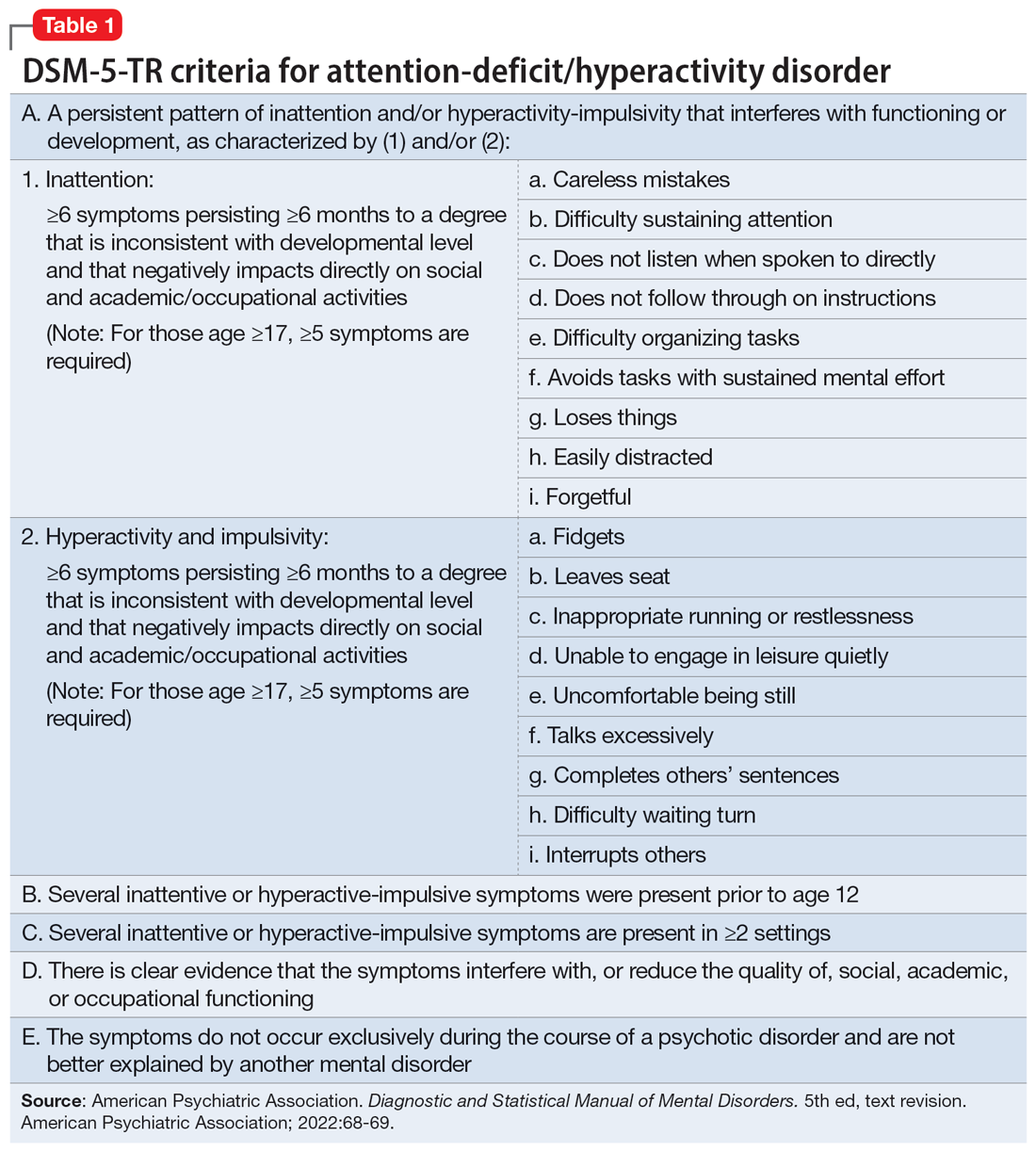

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD are summarized in Table 1. Establishing a diagnosis of adult ADHD can be challenging. As with many psychiatric conditions, symptoms of ADHD are highly subjective. Retrospectively diagnosing a developmental condition in adults is often biased by the patient’s current functioning.5 ADHD has a high heritability and adults may inquire about the diagnosis if their children are diagnosed with ADHD.6 Some experts have cautioned that clinicians must be careful in diagnosing ADHD in adults.7 Just as there are risks associated with underdiagnosing ADHD, there are risks associated with overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis may medicalize normal variants in the population and lead to unnecessary treatment and a misappropriation of limited medical resources.8 Many false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be attributable to nonimpairing cognitive fluctuations.9

Poor diagnostic practices can impede accuracy in establishing the presence or absence of ADHD. Unfortunately, methods of diagnosing adult ADHD have been shown to vary widely in terms of information sources, diagnostic instruments used, symptom threshold, and whether functional impairment is a requirement for diagnosis.10 A common practice in diagnosing adult ADHD involves asking patients to complete self-report questionnaires that list symptoms of ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale developed by the World Health Organization.11 However, self-reports of ADHD in adults are less reliable than informant reports, and some young adults without ADHD overreport symptoms.12,13 Symptom checklists are particularly susceptible to faking, which lessens their diagnostic value.14

The possibility of malingered symptoms of ADHD further increases the diagnostic difficulty. College students may be particularly susceptible to overreporting ADHD symptoms in order to obtain academic accommodations or stimulants in the hopes of improving school performance.15 One study found that 25% to 48% of college students self-referred for ADHD evaluations exaggerated their symptoms.16 In another study, 31% of adults failed the Word Memory Test, which suggests noncredible performance in their ADHD evaluation.17 College students can successfully feign ADHD symptoms in both self-reported symptoms and computer-based tests of attention.18 Harrison et al19 summarized many of these concerns in their 2007 study of ADHD malingering, noting the “almost perfect ability of the Faking group to choose items … that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms, and to report these at levels even higher than persons with diagnosed ADHD.” They suggested “Clinicians should be suspicious of students or young adults presenting for a first-time diagnosis who rate themselves as being significantly symptomatic, yet have managed to achieve well in school and other life activities.”19

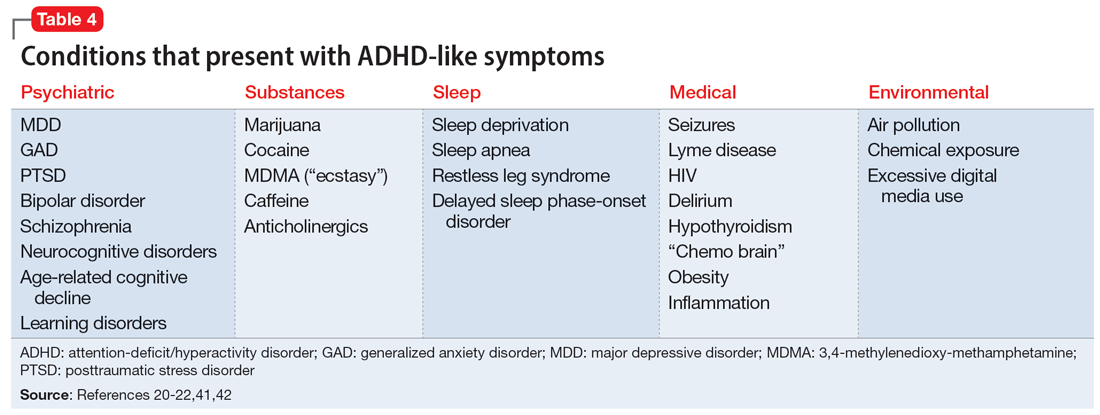

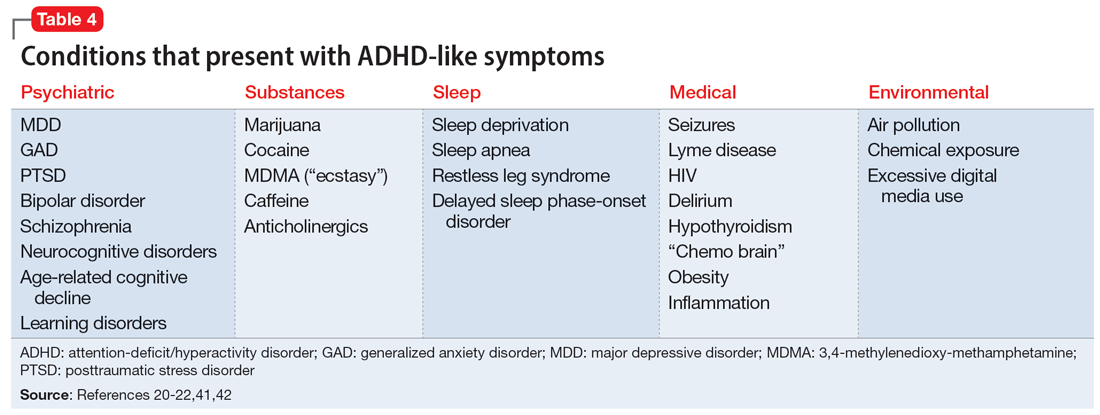

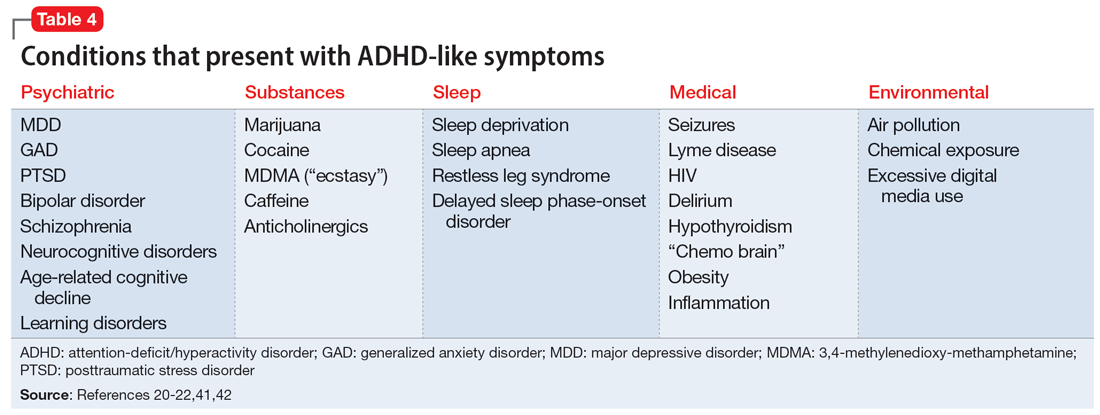

Another challenge in correctly diagnosing adult ADHD is identifying other conditions that may impair attention.20 Psychiatric conditions that may impair concentration include anxiety disorders, chronic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, recent trauma, major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar disorder (BD). Undiagnosed learning disorders may present like ADHD. Focus can be negatively affected by sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, or delayed sleep phase-onset disorder. Marijuana, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA; “ecstasy”), caffeine, or prescription medications such as anticholinergics can also impair attention. Medical conditions that can present with attentional or executive functioning deficits include seizures, Lyme disease, HIV, encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, and “chemo brain.”21 Environmental factors such as age-related cognitive decline, sleep deprivation, inflammation, obesity, air pollution, chemical exposure, and excessive use of digital media may also produce symptoms similar to ADHD. Two studies of adult-onset ADHD concluded that 93% to 95% of cases were better explained by other conditions such as sleep disorders, substance use disorders, or another psychiatric disorder.22

Continue to: Risks associated with treatment

Risks associated with treatment

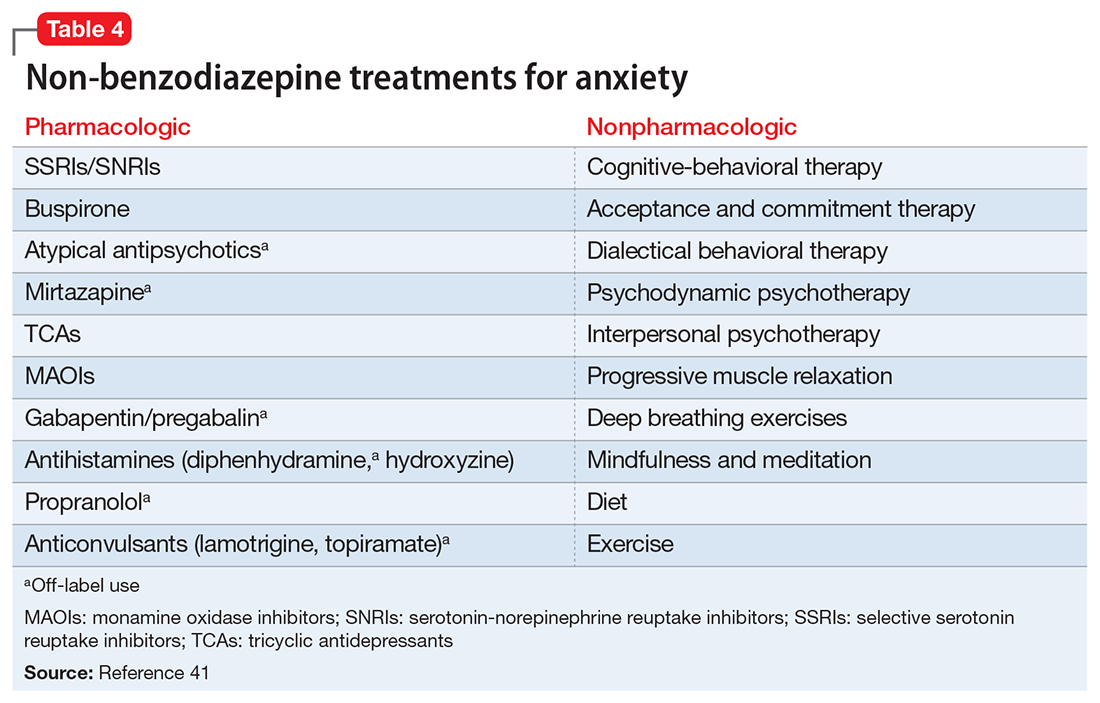

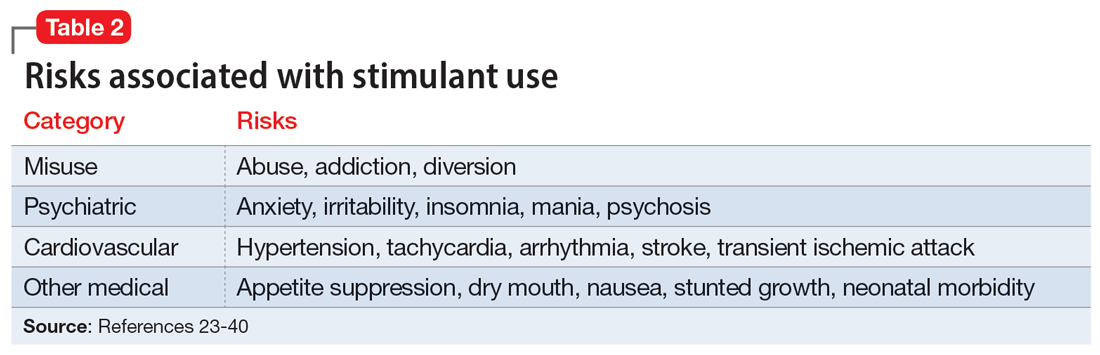

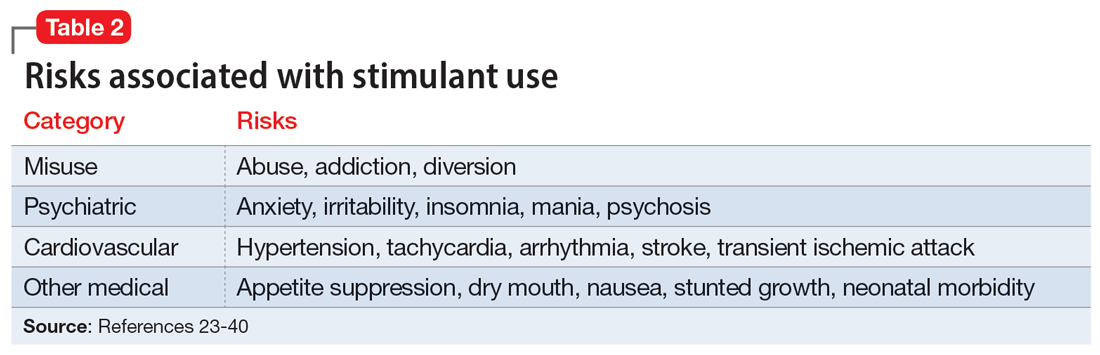

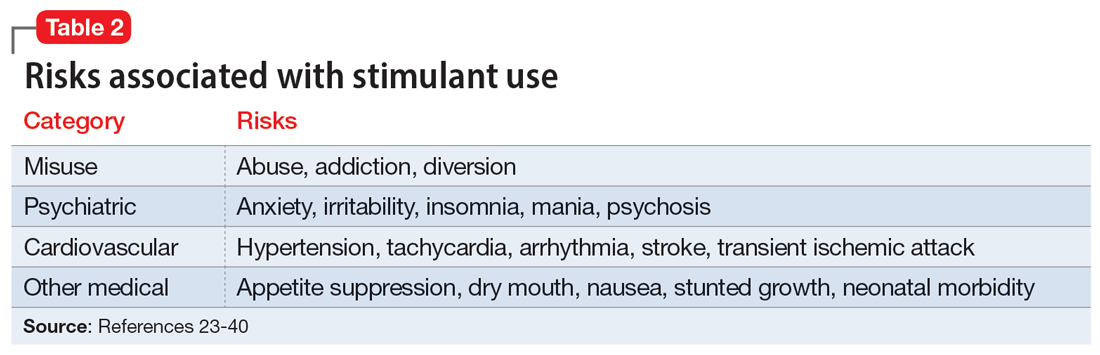

With or without an accurate ADHD diagnosis, prescribing stimulants presents certain risks (Table 223-40). One of the more well-known risks of stimulants is addiction or misuse.23 An estimated 5 million American adults misused prescription stimulants in 2016.24 Despite stimulants’ status as controlled substances, long-term concurrent use of stimulants with opioids is common among adults with ADHD.25 College students are particularly susceptible to misusing or diverting stimulants, often to improve their academic performance.26 At 1 university, 22% of students had misused stimulants in the past year.27 Prescribing short-acting stimulants (rather than extended-release formulations) increases the likelihood of misuse.28 Patients prescribed stimulants begin to receive requests to divert their medications to others as early as elementary school, and by college more than one-third of those taking stimulants have been asked to give, sell, or trade their medications.29 Diversion of stimulants by students with ADHD is prevalent, with 62% of patients engaging in diversion during their lifetime.15 Diverted stimulants can come from family members, black market sources, or deceived clinicians.30 Although students’ stimulant misuse/diversion often is academically motivated, nonmedical use of psychostimulants does not appear to have a statistically significant effect on improving grade point average.31 Despite a negligible impact on grades, most students who take stimulants identify their effect as strongly positive, producing a situation in which misusers of stimulants have little motivation to stop.32 While some patients might ask for a stimulant prescription with the rationale that liking the effects proves they have ADHD, this is inappropriate because most individuals like the effects of stimulant medications.33

The use of stimulants increases the risk for several adverse psychiatric outcomes. Stimulants increase the risk of anxiety, so exercise caution when prescribing to patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder.34 Stimulants can also worsen irritability and insomnia, 2 issues common among patients with ADHD.32 Use of stimulant medications can trigger manic episodes. Viktorin et al35 found a >6-fold increase in manic episodes among patients with BD receiving methylphenidate monotherapy compared to those receiving a combination of methylphenidate and a mood stabilizer.35 The use of methylphenidate and amphetamine can lead to new-onset psychosis (or exacerbation of pre-existing psychotic illness); amphetamine use is associated with a higher risk of psychosis than methylphenidate.36

General medical adverse effects are also possible with stimulant use. Stimulants’ adverse effect profiles include appetite suppression, dry mouth, and nausea. Long-term use poses a risk for stunting growth in children.1 Using stimulants during pregnancy is associated with higher risk for neonatal morbidity, including preterm birth, CNS-related disorders, and seizures.37 Stimulants can raise blood pressure and increase heart rate. Serious cardiovascular events associated with stimulant use include ventricular arrhythmias, strokes, and transient ischemic attacks.38

Nonstimulant ADHD treatments are less risky than stimulants but still require monitoring for common adverse effects. Atomoxetine has been associated with sedation, growth retardation (in children), and in severe cases, liver injury or suicidal ideation.39 Bupropion (commonly used off-label for ADHD) can lower the seizure threshold and cause irritability, anorexia, and insomnia.39 Viloxazine, a newer agent, can cause hypertension, increased heart rate, nausea, drowsiness, headache, and insomnia.40

Sensible diagnosing

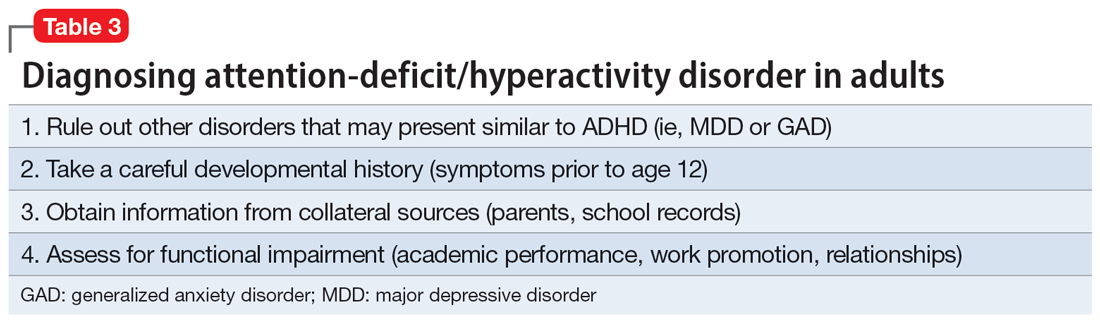

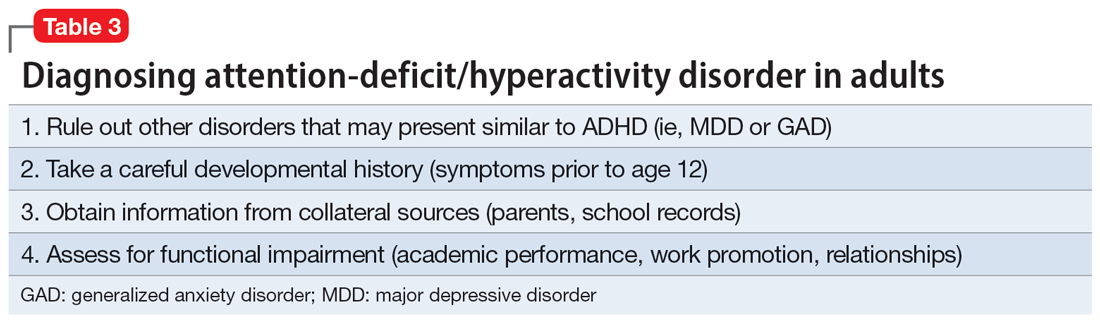

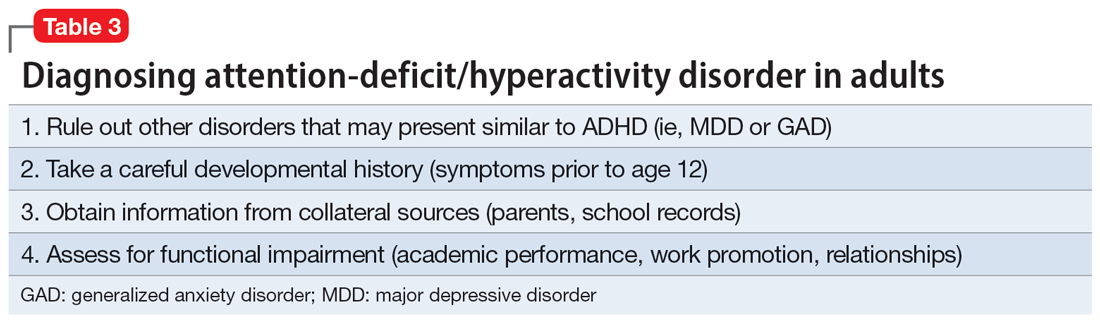

Given the challenges in accurately diagnosing ADHD in adults, we present a sensible approach to making the diagnosis (Table 3). The first step is to rule out other conditions that might better explain the patient’s symptoms. A thorough clinical interview (including a psychiatric review of symptoms) is the cornerstone of an initial diagnostic assessment. The use of validated screening questionnaires such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and General Anxiety Disorder-7 may also provide information regarding psychiatric conditions that require additional evaluation.

Continue to: Some of the most common conditions...

Some of the most common conditions we see mistaken for ADHD are MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and BD. In DSM-5-TR, 1 of the diagnostic criteria for MDD is “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).”41 Similarly, criteria for GAD include “difficulty concentrating.”42 DSM-5-TR also includes distractibility as one of the criteria for mania/hypomania. Table 420-22,41,42 lists other psychiatric, substance-related, medical, and environmental conditions that can produce ADHD-like symptoms. Referring to some medical and environmental explanations for inattention, Aiken22 pointed out, “Patients who suffer from these problems might ask their doctor for a stimulant, but none of those syndromes require a psychopharmacologic approach.” ADHD can be comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, so the presence of another psychiatric illness does not automatically rule out ADHD. If alternative psychiatric diagnoses have been identified, these can be discussed with the patient and treatment offered that targets the specified condition.

Once alternative explanations have been ruled out, focus on the patient’s developmental history. DSM-5-TR conceptualizes ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning it is expected to emerge early in life. Whereas previous editions of DSM specified that ADHD symptoms must be present before age 7, DSM-5 modified this age threshold to before age 12.1 This necessitates taking a careful life history in order to understand the presence or absence of symptoms at earlier developmental stages.5 ADHD should be verified by symptoms apparent in childhood and present across the lifespan.15

While this retrospective history is necessary, histories that rely on self-report alone are often unreliable. Collateral sources of information are generally more reliable when assessing for ADHD symptoms.13 Third-party sources can help confirm that any impairment is best attributed to ADHD rather than to another condition.15 Unfortunately, the difficulty of obtaining collateral information means it is often neglected, even in the literature.10 A parent is the ideal informant for gathering collateral information regarding a patient’s functioning in childhood.5 Suggested best practices also include obtaining collateral information from interviews with significant others, behavioral questionnaires completed by parents (for current and childhood symptoms), review of school records, and consideration of intellectual and achievement testing.43 If psychological testing is pursued, include validity testing to detect feigned symptoms.18,44

When evaluating for ADHD, assess not only for the presence of symptoms, but also if these symptoms produce significant functional impairment.13,15 Impairments in daily functioning can include impaired school participation, social participation, quality of relationships, family conflict, family activities, family functioning, and emotional functioning.45 Some symptoms may affect functioning in an adult’s life differently than they did during childhood, from missed work appointments to being late picking up kids from school. Research has shown that the correlation between the number of symptoms and functional impairment is weak, which means someone could experience all of the symptoms of ADHD without experiencing functional impairment.45 To make an accurate diagnosis, it is therefore important to clearly establish both the number of symptoms the patient is experiencing and whether these symptoms are clearly linked to functional impairments.10

Sensible treatment

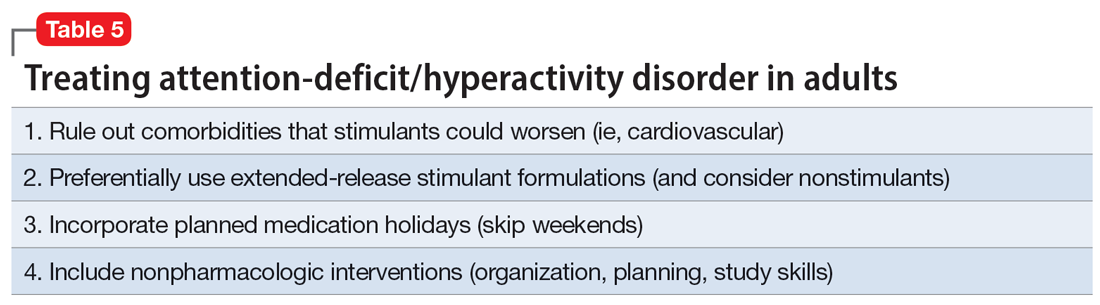

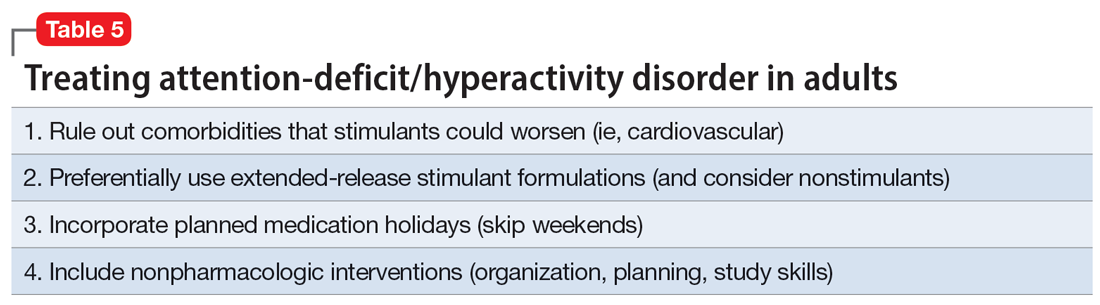

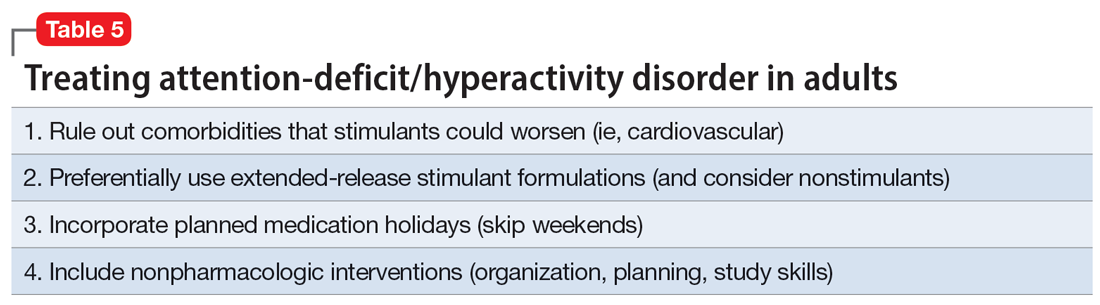

Once a diagnosis of ADHD has been clearly established, clinicians need to consider how best to treat the condition (Table 5). Stimulants are generally considered first-line treatment for ADHD. In randomized clinical trials, they showed significant efficacy; for example, one study of 146 adults with ADHD found a 76% improvement with methylphenidate compared to 19% for the placebo group.46 Before starting a stimulant, certain comorbidities should be ruled out. If a patient has glaucoma or pheochromocytoma, they may first need treatment from or clearance by other specialists. Stimulants should likely be held in patients with hypertension, angina, or cardiovascular defects until receiving medical clearance. The risks of stimulants need to be discussed with female patients of childbearing age, weighing the benefits of treatment against the risks of medication use should the patient get pregnant. Patients with comorbid psychosis or uncontrolled bipolar illness should not receive stimulants due to the risk of exacerbation. Patients with active substance use disorders (SUDs) are generally not good candidates for stimulants because of the risk of misusing or diverting stimulants and the possibility that substance abuse may be causing their inattentive symptoms. Patients whose SUDs are in remission may cautiously be considered as candidates for stimulants. If patients misuse their prescribed stimulants, they should be switched to a nonstimulant medication such as atomoxetine, bupropion, guanfacine, or clonidine.47

Continue to: Once a patient is deemed...

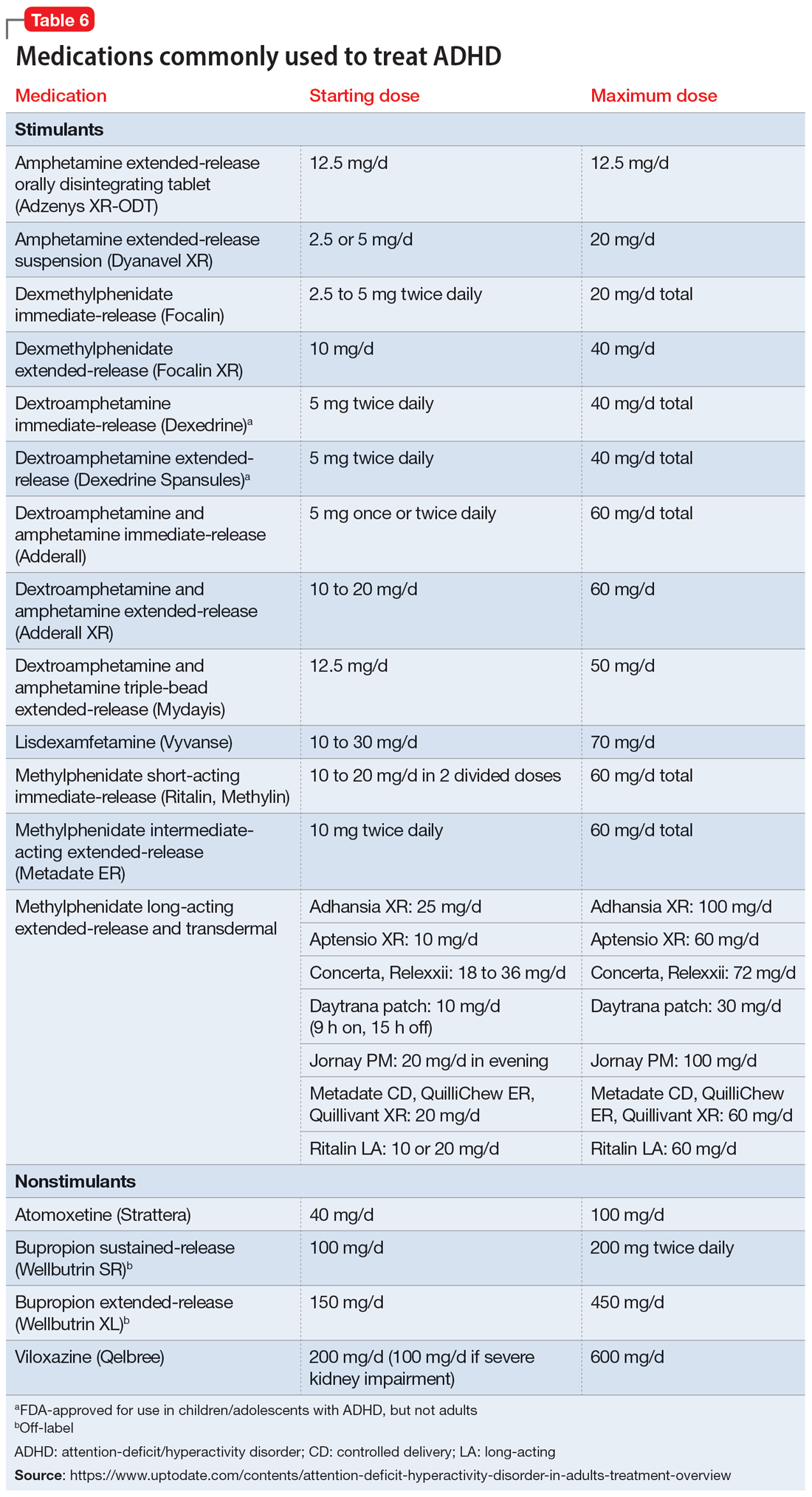

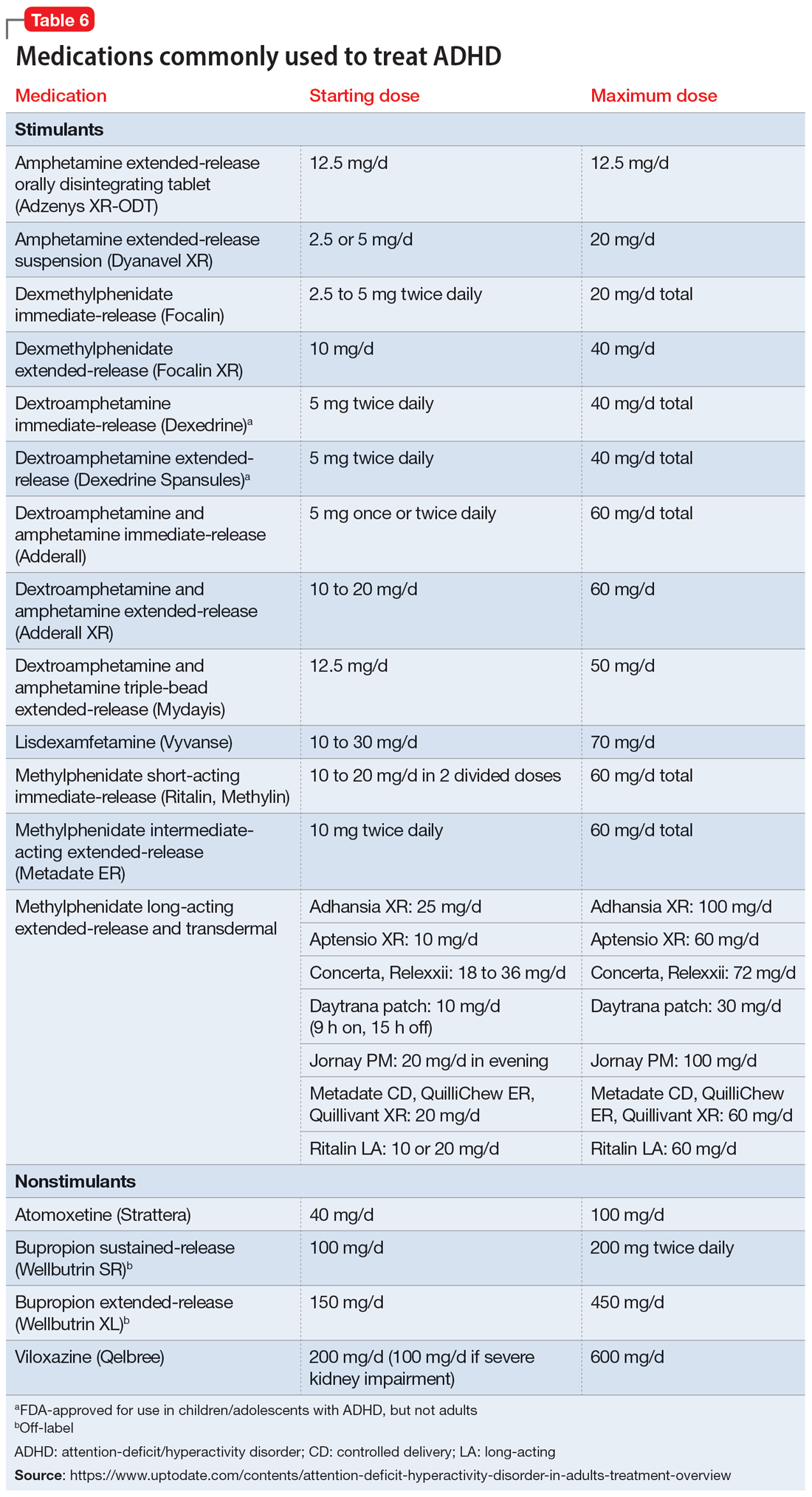

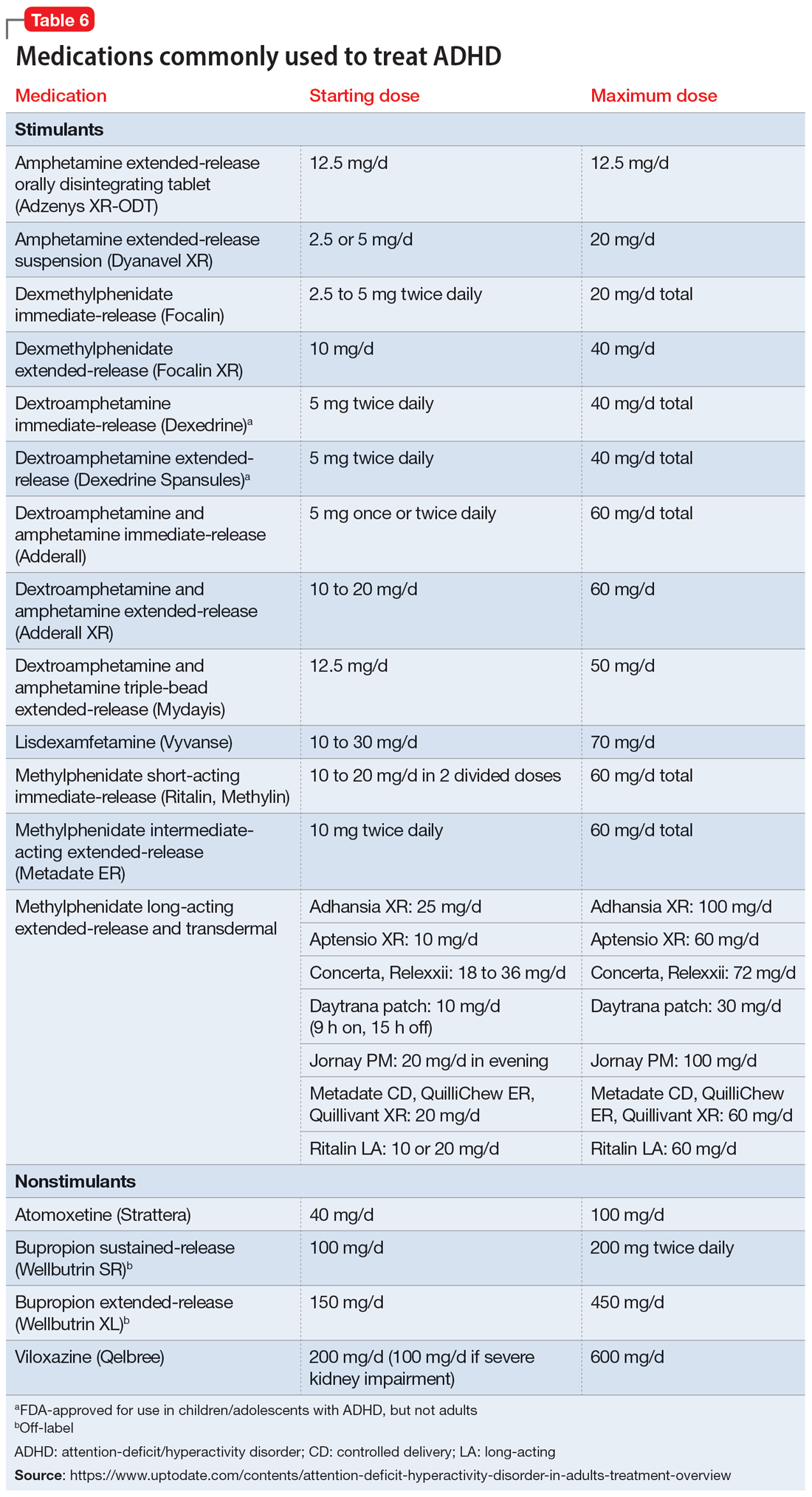

Once a patient is deemed to be a candidate for stimulants, clinicians need to choose between methylphenidate or amphetamine/dextroamphetamine formulations. Table 6 lists medications that are commonly prescribed to treat ADHD; unless otherwise noted, these are FDA-approved for this indication. As a general rule, for adults, long-acting stimulant formulations are preferred over short-acting formulations.28 Immediate-release stimulants are more prone to misuse or diversion compared to extended-release medications.29 Longer-acting formulations may also provide better full-day symptom control.48

In contrast to many other psychiatric medications, it may be beneficial to encourage periodically taking breaks or “medication holidays” from stimulants. Planned medication holidays for adults can involve intentionally not taking the medication over the weekend when the patient is not involved in work or school responsibilities. Such breaks have been shown to reduce adverse effects of stimulants (such as appetite suppression and insomnia) without significantly increasing ADHD symptoms.49 Short breaks can also help prevent medication tolerance and the subsequent need to increase doses.50 Medication holidays provide an opportunity to verify the ongoing benefits of the medication. It is advisable to periodically assess whether there is a continued need for stimulant treatment.51 If patients do not tolerate stimulants or have other contraindications, nonstimulants should be considered.

Lastly, no psychiatric patient should be treated with medication alone, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be incorporated as needed. Clear instructions, visual aids, nonverbal cues, frequent breaks to stand and stretch, schedules, normalizing failure as part of growth, and identifying triggers for emotional reactivity may help patients with ADHD.52 In a study of the academic performance of 92 college students taking medication for ADHD and 146 control students, treatment with stimulants alone did not eliminate the academic achievement deficit of those individuals with ADHD.53 Good study habits (even without stimulants) appeared more important in overcoming the achievement disparity of students with ADHD.53 Providing psychoeducation and training in concrete organization and planning skills have shown benefit.54 Practice of skills on a daily basis appears to be especially beneficial.55

Bottom Line

A sensible approach to diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults includes ruling out other disorders that may present similar to ADHD, taking an appropriate developmental history, obtaining collateral information, and assessing for functional impairment. Sensible treatment involves ruling out comorbidities that stimulants could worsen, selecting extended-release stimulants, incorporating medication holidays, and using nonpharmacologic interventions.

Related Resources

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: Prescription Stimulant Misuse Among Youth and Young Adults. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/prescription-stimulant-misuse-among-youth-young-adults/PEP21-06-01-003

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine • Adzenys, Dyanavel, others

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Forfivo

Clonidine • Catapres, Kapvay

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine • Adderall, Mydayis

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin, others

Viloxazine • Qelbree

1. Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450-462.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:35.

3. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

4. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, et al. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulants in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

5. McGough JJ, Barkley RA. Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1948-1956.

6. Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562-575.

7. Solanto MV. Child vs adult onset of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):421.

8. Jummani RR, Hirsch E, Hirsch GS. Are we overdiagnosing and overtreating ADHD? Psychiatric Times. Published May 31, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/are-we-overdiagnosing-and-overtreating-adhd

9. Sibley MH, Rohde LA, Swanson JM, et al; Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) Cooperative Group. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):140-149.

10. Sibley MH, Mitchell JT, Becker SP. Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(12):1157-1165.

11. Ustun B, Adler LA, Rudin C, et al. The World Health Organization adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report screening scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):520-527.

12. Faraone SV, Biederman J. Can attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder onset occur in adulthood? JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):655-656.

13. Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. When diagnosing ADHD in young adults emphasize informant reports, DSM items, and impairment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(6):1052-1061.

14. Sollman MJ, Ranseen JD, Berry DT. Detection of feigned ADHD in college students. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):325-335.

15. Green AL, Rabiner DL. What do we really know about ADHD in college students? Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):559-568.

16. Sullivan BK, May K, Galbally L. Symptom exaggeration by college adults in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disorder assessments. Appl Neuropsychol. 2007;14(3):189-207.

17. Suhr J, Hammers D, Dobbins-Buckland K, et al. The relationship of malingering test failure to self-reported symptoms and neuropsychological findings in adults referred for ADHD evaluation. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(5):521-530.

18. Lee Booksh R, Pella RD, Singh AN, et al. Ability of college students to simulate ADHD on objective measures of attention. J Atten Disord. 2010;13(4):325-338.

19. Harrison AG, Edwards MJ, Parker KC. Identifying students faking ADHD: preliminary findings and strategies for detection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(5):577-588.

20. Lopez R, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Galeria C, et al. Is adult-onset attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder frequent in clinical practice? Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:238-241.

21. Bhatia R. Rule out these causes of inattention before diagnosing ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(10):32-33.

22. Aiken C. Adult-onset ADHD raises questions. Psychiatric Times. 2021;38(3):24.

23. Bjorn S, Weyandt LL. Issues pertaining to misuse of ADHD prescription medications. Psychiatric Times. 2018;35(9):17-19.

24. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, and motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.

25. Wei YJ, Zhu Y, Liu W, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with long-term concurrent use of stimulants and opioids among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181152. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1152

26. Benson K, Flory K, Humphreys KL, et al. Misuse of stimulant medication among college students: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(1):50-76.

27. Benson K, Woodlief DT, Flory K, et al. Is ADHD, independent of ODD, associated with whether and why college students misuse stimulant medication? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26(5):476-487.

28. Froehlich TE. ADHD medication adherence in college students-- a call to action for clinicians and researchers: commentary on “transition to college and adherence to prescribed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication.” J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39(1):77-78.

29. Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, et al. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21-31.

30. Vrecko S. Everyday drug diversions: a qualitative study of the illicit exchange and non-medical use of prescription stimulants on a university campus. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131:297-304.

31. Munro BA, Weyandt LL, Marraccini ME, et al. The relationship between nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, executive functioning and academic outcomes. Addict Behav. 2017;65:250-257.

32. Rabiner DL, Anastopoulos AD, Costello EJ, et al. Motives and perceived consequences of nonmedical ADHD medication use by college students: are students treating themselves for attention problems? J Atten Disord. 2009;13(3)259-270.

33. Tayag Y. Adult ADHD is the wild west of psychiatry. The Atlantic. Published April 14, 2023. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/04/adult-adhd-diagnosis-treatment-adderall-shortage/673719/

34. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270.

35. Viktorin A, Rydén E, Thase ME, et al. The risk of treatment-emergent mania with methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(4):341-348.

36. Moran LV, Ongur D, Hsu J, et al. Psychosis with methylphenidate or amphetamine in patients with ADHD. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380(12):1128-1138.

37. Nörby U, Winbladh B, Källén K. Perinatal outcomes after treatment with ADHD medication during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170747. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0747

38. Tadrous M, Shakeri A, Chu C, et al. Assessment of stimulant use and cardiovascular event risks among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30795

39. Daughton JM, Kratochvil CJ. Review of ADHD pharmacotherapies: advantages, disadvantages, and clinical pearls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):240-248.

40. Qelbree [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Supernus Pharmaceuticals; 2021.

41. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:183.

42. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:250.

43. DuPaul GJ, Weyandt LL, O’Dell SM, et al. College students with ADHD: current status and future directions. J Atten Disord. 2009;13(3):234-250.

44. Edmundson M, Berry DTR, Combs HL, et al. The effects of symptom information coaching on the feigning of adult ADHD. Psychol Assess. 2017;29(12):1429-1436.

45. Gordon M, Antshel K, Faraone S, et al. Symptoms versus impairment: the case for respecting DSM-IV’s criterion D. J Atten Disord. 2006;9(3):465-475.

46. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):456-463.

47. Osser D, Awidi B. Treating adults with ADHD requires special considerations. Psychiatric News. Published August 30, 2018. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.pp8a1

48. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management; Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown, RT, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007-1022.

49. Martins S, Tramontina S, Polanczyk G, et al. Weekend holidays during methylphenidate use in ADHD children: a randomized clinical trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):195-206.

50. Ibrahim K, Donyai P. Drug holidays from ADHD medication: international experience over the past four decades. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(7):551-568.

51. Matthijssen AM, Dietrich A, Bierens M, et al. Continued benefits of methylphenidate in ADHD after 2 years in clinical practice: a randomized placebo-controlled discontinuation study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(9):754-762.

52. Mason EJ, Joshi KG. Nonpharmacologic strategies for helping children with ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2018;7(1):42,46.

53. Advokat C, Lane SM, Luo C. College students with and without ADHD: comparison of self-report of medication usage, study habits, and academic achievement. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(8):656-666.

54. Knouse LE, Cooper-Vince C, Sprich S, et al. Recent developments in the psychosocial treatment of adult ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1537-1548.

55. Evans SW, Owens JS, Wymbs BT, et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):157-198.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is common, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5.29% among children and adolescents and 2.5% among adults.1 DSM-5-TR classifies ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, “a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period [that] typically manifest early in development, often before the child enters school.”2 Because of the expectation that ADHD symptoms emerge early in development, the diagnostic criteria specify that symptoms must have been present prior to age 12 to qualify as ADHD. However, recent years have shown a significant increase in the number of patients being diagnosed with ADHD for the first time in adulthood. One study found that the diagnosis of ADHD among adults in the United States doubled between 2007 and 2016.3

First-line treatment for ADHD is the stimulants methylphenidate and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. In the United States, these medications are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, indicating a high risk for abuse. However, just as ADHD diagnoses among adults have increased, so have prescriptions for stimulants. For example, Olfson et al4 found that stimulant prescriptions among young adults increased by a factor of 10 between 1994 and 2009.

The increased prevalence of adult patients diagnosed with ADHD and taking stimulants frequently places clinicians in a position to consider the validity of existing diagnoses and evaluate new patients with ADHD-related concerns. In this article, we review some of the challenges associated with diagnosing ADHD in adults, discuss the risks of stimulant treatment, and present a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults.

Challenges in diagnosis

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD are summarized in Table 1. Establishing a diagnosis of adult ADHD can be challenging. As with many psychiatric conditions, symptoms of ADHD are highly subjective. Retrospectively diagnosing a developmental condition in adults is often biased by the patient’s current functioning.5 ADHD has a high heritability and adults may inquire about the diagnosis if their children are diagnosed with ADHD.6 Some experts have cautioned that clinicians must be careful in diagnosing ADHD in adults.7 Just as there are risks associated with underdiagnosing ADHD, there are risks associated with overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis may medicalize normal variants in the population and lead to unnecessary treatment and a misappropriation of limited medical resources.8 Many false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be attributable to nonimpairing cognitive fluctuations.9

Poor diagnostic practices can impede accuracy in establishing the presence or absence of ADHD. Unfortunately, methods of diagnosing adult ADHD have been shown to vary widely in terms of information sources, diagnostic instruments used, symptom threshold, and whether functional impairment is a requirement for diagnosis.10 A common practice in diagnosing adult ADHD involves asking patients to complete self-report questionnaires that list symptoms of ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale developed by the World Health Organization.11 However, self-reports of ADHD in adults are less reliable than informant reports, and some young adults without ADHD overreport symptoms.12,13 Symptom checklists are particularly susceptible to faking, which lessens their diagnostic value.14

The possibility of malingered symptoms of ADHD further increases the diagnostic difficulty. College students may be particularly susceptible to overreporting ADHD symptoms in order to obtain academic accommodations or stimulants in the hopes of improving school performance.15 One study found that 25% to 48% of college students self-referred for ADHD evaluations exaggerated their symptoms.16 In another study, 31% of adults failed the Word Memory Test, which suggests noncredible performance in their ADHD evaluation.17 College students can successfully feign ADHD symptoms in both self-reported symptoms and computer-based tests of attention.18 Harrison et al19 summarized many of these concerns in their 2007 study of ADHD malingering, noting the “almost perfect ability of the Faking group to choose items … that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms, and to report these at levels even higher than persons with diagnosed ADHD.” They suggested “Clinicians should be suspicious of students or young adults presenting for a first-time diagnosis who rate themselves as being significantly symptomatic, yet have managed to achieve well in school and other life activities.”19

Another challenge in correctly diagnosing adult ADHD is identifying other conditions that may impair attention.20 Psychiatric conditions that may impair concentration include anxiety disorders, chronic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, recent trauma, major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar disorder (BD). Undiagnosed learning disorders may present like ADHD. Focus can be negatively affected by sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, or delayed sleep phase-onset disorder. Marijuana, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA; “ecstasy”), caffeine, or prescription medications such as anticholinergics can also impair attention. Medical conditions that can present with attentional or executive functioning deficits include seizures, Lyme disease, HIV, encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, and “chemo brain.”21 Environmental factors such as age-related cognitive decline, sleep deprivation, inflammation, obesity, air pollution, chemical exposure, and excessive use of digital media may also produce symptoms similar to ADHD. Two studies of adult-onset ADHD concluded that 93% to 95% of cases were better explained by other conditions such as sleep disorders, substance use disorders, or another psychiatric disorder.22

Continue to: Risks associated with treatment

Risks associated with treatment

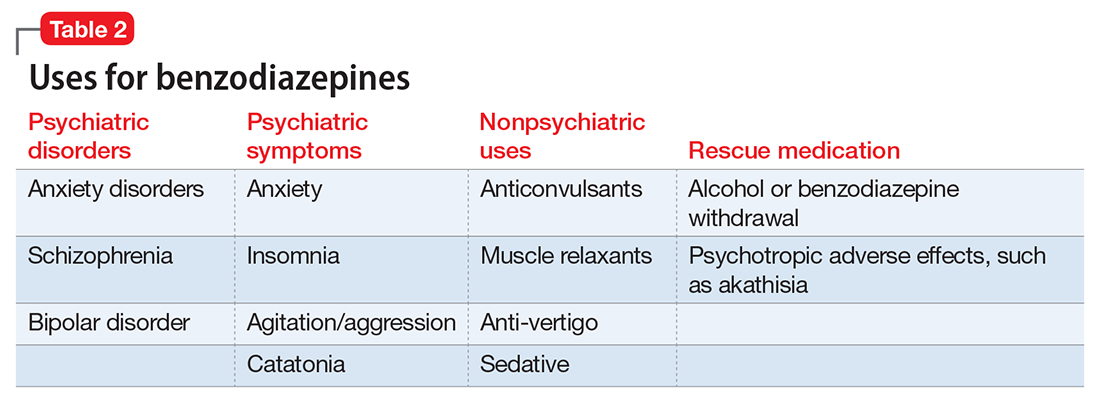

With or without an accurate ADHD diagnosis, prescribing stimulants presents certain risks (Table 223-40). One of the more well-known risks of stimulants is addiction or misuse.23 An estimated 5 million American adults misused prescription stimulants in 2016.24 Despite stimulants’ status as controlled substances, long-term concurrent use of stimulants with opioids is common among adults with ADHD.25 College students are particularly susceptible to misusing or diverting stimulants, often to improve their academic performance.26 At 1 university, 22% of students had misused stimulants in the past year.27 Prescribing short-acting stimulants (rather than extended-release formulations) increases the likelihood of misuse.28 Patients prescribed stimulants begin to receive requests to divert their medications to others as early as elementary school, and by college more than one-third of those taking stimulants have been asked to give, sell, or trade their medications.29 Diversion of stimulants by students with ADHD is prevalent, with 62% of patients engaging in diversion during their lifetime.15 Diverted stimulants can come from family members, black market sources, or deceived clinicians.30 Although students’ stimulant misuse/diversion often is academically motivated, nonmedical use of psychostimulants does not appear to have a statistically significant effect on improving grade point average.31 Despite a negligible impact on grades, most students who take stimulants identify their effect as strongly positive, producing a situation in which misusers of stimulants have little motivation to stop.32 While some patients might ask for a stimulant prescription with the rationale that liking the effects proves they have ADHD, this is inappropriate because most individuals like the effects of stimulant medications.33

The use of stimulants increases the risk for several adverse psychiatric outcomes. Stimulants increase the risk of anxiety, so exercise caution when prescribing to patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder.34 Stimulants can also worsen irritability and insomnia, 2 issues common among patients with ADHD.32 Use of stimulant medications can trigger manic episodes. Viktorin et al35 found a >6-fold increase in manic episodes among patients with BD receiving methylphenidate monotherapy compared to those receiving a combination of methylphenidate and a mood stabilizer.35 The use of methylphenidate and amphetamine can lead to new-onset psychosis (or exacerbation of pre-existing psychotic illness); amphetamine use is associated with a higher risk of psychosis than methylphenidate.36

General medical adverse effects are also possible with stimulant use. Stimulants’ adverse effect profiles include appetite suppression, dry mouth, and nausea. Long-term use poses a risk for stunting growth in children.1 Using stimulants during pregnancy is associated with higher risk for neonatal morbidity, including preterm birth, CNS-related disorders, and seizures.37 Stimulants can raise blood pressure and increase heart rate. Serious cardiovascular events associated with stimulant use include ventricular arrhythmias, strokes, and transient ischemic attacks.38

Nonstimulant ADHD treatments are less risky than stimulants but still require monitoring for common adverse effects. Atomoxetine has been associated with sedation, growth retardation (in children), and in severe cases, liver injury or suicidal ideation.39 Bupropion (commonly used off-label for ADHD) can lower the seizure threshold and cause irritability, anorexia, and insomnia.39 Viloxazine, a newer agent, can cause hypertension, increased heart rate, nausea, drowsiness, headache, and insomnia.40

Sensible diagnosing

Given the challenges in accurately diagnosing ADHD in adults, we present a sensible approach to making the diagnosis (Table 3). The first step is to rule out other conditions that might better explain the patient’s symptoms. A thorough clinical interview (including a psychiatric review of symptoms) is the cornerstone of an initial diagnostic assessment. The use of validated screening questionnaires such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and General Anxiety Disorder-7 may also provide information regarding psychiatric conditions that require additional evaluation.

Continue to: Some of the most common conditions...

Some of the most common conditions we see mistaken for ADHD are MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and BD. In DSM-5-TR, 1 of the diagnostic criteria for MDD is “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).”41 Similarly, criteria for GAD include “difficulty concentrating.”42 DSM-5-TR also includes distractibility as one of the criteria for mania/hypomania. Table 420-22,41,42 lists other psychiatric, substance-related, medical, and environmental conditions that can produce ADHD-like symptoms. Referring to some medical and environmental explanations for inattention, Aiken22 pointed out, “Patients who suffer from these problems might ask their doctor for a stimulant, but none of those syndromes require a psychopharmacologic approach.” ADHD can be comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, so the presence of another psychiatric illness does not automatically rule out ADHD. If alternative psychiatric diagnoses have been identified, these can be discussed with the patient and treatment offered that targets the specified condition.

Once alternative explanations have been ruled out, focus on the patient’s developmental history. DSM-5-TR conceptualizes ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning it is expected to emerge early in life. Whereas previous editions of DSM specified that ADHD symptoms must be present before age 7, DSM-5 modified this age threshold to before age 12.1 This necessitates taking a careful life history in order to understand the presence or absence of symptoms at earlier developmental stages.5 ADHD should be verified by symptoms apparent in childhood and present across the lifespan.15

While this retrospective history is necessary, histories that rely on self-report alone are often unreliable. Collateral sources of information are generally more reliable when assessing for ADHD symptoms.13 Third-party sources can help confirm that any impairment is best attributed to ADHD rather than to another condition.15 Unfortunately, the difficulty of obtaining collateral information means it is often neglected, even in the literature.10 A parent is the ideal informant for gathering collateral information regarding a patient’s functioning in childhood.5 Suggested best practices also include obtaining collateral information from interviews with significant others, behavioral questionnaires completed by parents (for current and childhood symptoms), review of school records, and consideration of intellectual and achievement testing.43 If psychological testing is pursued, include validity testing to detect feigned symptoms.18,44

When evaluating for ADHD, assess not only for the presence of symptoms, but also if these symptoms produce significant functional impairment.13,15 Impairments in daily functioning can include impaired school participation, social participation, quality of relationships, family conflict, family activities, family functioning, and emotional functioning.45 Some symptoms may affect functioning in an adult’s life differently than they did during childhood, from missed work appointments to being late picking up kids from school. Research has shown that the correlation between the number of symptoms and functional impairment is weak, which means someone could experience all of the symptoms of ADHD without experiencing functional impairment.45 To make an accurate diagnosis, it is therefore important to clearly establish both the number of symptoms the patient is experiencing and whether these symptoms are clearly linked to functional impairments.10

Sensible treatment

Once a diagnosis of ADHD has been clearly established, clinicians need to consider how best to treat the condition (Table 5). Stimulants are generally considered first-line treatment for ADHD. In randomized clinical trials, they showed significant efficacy; for example, one study of 146 adults with ADHD found a 76% improvement with methylphenidate compared to 19% for the placebo group.46 Before starting a stimulant, certain comorbidities should be ruled out. If a patient has glaucoma or pheochromocytoma, they may first need treatment from or clearance by other specialists. Stimulants should likely be held in patients with hypertension, angina, or cardiovascular defects until receiving medical clearance. The risks of stimulants need to be discussed with female patients of childbearing age, weighing the benefits of treatment against the risks of medication use should the patient get pregnant. Patients with comorbid psychosis or uncontrolled bipolar illness should not receive stimulants due to the risk of exacerbation. Patients with active substance use disorders (SUDs) are generally not good candidates for stimulants because of the risk of misusing or diverting stimulants and the possibility that substance abuse may be causing their inattentive symptoms. Patients whose SUDs are in remission may cautiously be considered as candidates for stimulants. If patients misuse their prescribed stimulants, they should be switched to a nonstimulant medication such as atomoxetine, bupropion, guanfacine, or clonidine.47

Continue to: Once a patient is deemed...

Once a patient is deemed to be a candidate for stimulants, clinicians need to choose between methylphenidate or amphetamine/dextroamphetamine formulations. Table 6 lists medications that are commonly prescribed to treat ADHD; unless otherwise noted, these are FDA-approved for this indication. As a general rule, for adults, long-acting stimulant formulations are preferred over short-acting formulations.28 Immediate-release stimulants are more prone to misuse or diversion compared to extended-release medications.29 Longer-acting formulations may also provide better full-day symptom control.48

In contrast to many other psychiatric medications, it may be beneficial to encourage periodically taking breaks or “medication holidays” from stimulants. Planned medication holidays for adults can involve intentionally not taking the medication over the weekend when the patient is not involved in work or school responsibilities. Such breaks have been shown to reduce adverse effects of stimulants (such as appetite suppression and insomnia) without significantly increasing ADHD symptoms.49 Short breaks can also help prevent medication tolerance and the subsequent need to increase doses.50 Medication holidays provide an opportunity to verify the ongoing benefits of the medication. It is advisable to periodically assess whether there is a continued need for stimulant treatment.51 If patients do not tolerate stimulants or have other contraindications, nonstimulants should be considered.

Lastly, no psychiatric patient should be treated with medication alone, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be incorporated as needed. Clear instructions, visual aids, nonverbal cues, frequent breaks to stand and stretch, schedules, normalizing failure as part of growth, and identifying triggers for emotional reactivity may help patients with ADHD.52 In a study of the academic performance of 92 college students taking medication for ADHD and 146 control students, treatment with stimulants alone did not eliminate the academic achievement deficit of those individuals with ADHD.53 Good study habits (even without stimulants) appeared more important in overcoming the achievement disparity of students with ADHD.53 Providing psychoeducation and training in concrete organization and planning skills have shown benefit.54 Practice of skills on a daily basis appears to be especially beneficial.55

Bottom Line

A sensible approach to diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults includes ruling out other disorders that may present similar to ADHD, taking an appropriate developmental history, obtaining collateral information, and assessing for functional impairment. Sensible treatment involves ruling out comorbidities that stimulants could worsen, selecting extended-release stimulants, incorporating medication holidays, and using nonpharmacologic interventions.

Related Resources

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: Prescription Stimulant Misuse Among Youth and Young Adults. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/prescription-stimulant-misuse-among-youth-young-adults/PEP21-06-01-003

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine • Adzenys, Dyanavel, others

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Forfivo

Clonidine • Catapres, Kapvay

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine • Adderall, Mydayis

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin, others

Viloxazine • Qelbree

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is common, with an estimated worldwide prevalence of 5.29% among children and adolescents and 2.5% among adults.1 DSM-5-TR classifies ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, “a group of conditions with onset in the developmental period [that] typically manifest early in development, often before the child enters school.”2 Because of the expectation that ADHD symptoms emerge early in development, the diagnostic criteria specify that symptoms must have been present prior to age 12 to qualify as ADHD. However, recent years have shown a significant increase in the number of patients being diagnosed with ADHD for the first time in adulthood. One study found that the diagnosis of ADHD among adults in the United States doubled between 2007 and 2016.3

First-line treatment for ADHD is the stimulants methylphenidate and amphetamine/dextroamphetamine. In the United States, these medications are classified as Schedule II controlled substances, indicating a high risk for abuse. However, just as ADHD diagnoses among adults have increased, so have prescriptions for stimulants. For example, Olfson et al4 found that stimulant prescriptions among young adults increased by a factor of 10 between 1994 and 2009.

The increased prevalence of adult patients diagnosed with ADHD and taking stimulants frequently places clinicians in a position to consider the validity of existing diagnoses and evaluate new patients with ADHD-related concerns. In this article, we review some of the challenges associated with diagnosing ADHD in adults, discuss the risks of stimulant treatment, and present a practical approach to the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD in adults.

Challenges in diagnosis

DSM-5-TR diagnostic criteria for ADHD are summarized in Table 1. Establishing a diagnosis of adult ADHD can be challenging. As with many psychiatric conditions, symptoms of ADHD are highly subjective. Retrospectively diagnosing a developmental condition in adults is often biased by the patient’s current functioning.5 ADHD has a high heritability and adults may inquire about the diagnosis if their children are diagnosed with ADHD.6 Some experts have cautioned that clinicians must be careful in diagnosing ADHD in adults.7 Just as there are risks associated with underdiagnosing ADHD, there are risks associated with overdiagnosis. Overdiagnosis may medicalize normal variants in the population and lead to unnecessary treatment and a misappropriation of limited medical resources.8 Many false positive cases of late-onset ADHD may be attributable to nonimpairing cognitive fluctuations.9

Poor diagnostic practices can impede accuracy in establishing the presence or absence of ADHD. Unfortunately, methods of diagnosing adult ADHD have been shown to vary widely in terms of information sources, diagnostic instruments used, symptom threshold, and whether functional impairment is a requirement for diagnosis.10 A common practice in diagnosing adult ADHD involves asking patients to complete self-report questionnaires that list symptoms of ADHD, such as the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale developed by the World Health Organization.11 However, self-reports of ADHD in adults are less reliable than informant reports, and some young adults without ADHD overreport symptoms.12,13 Symptom checklists are particularly susceptible to faking, which lessens their diagnostic value.14

The possibility of malingered symptoms of ADHD further increases the diagnostic difficulty. College students may be particularly susceptible to overreporting ADHD symptoms in order to obtain academic accommodations or stimulants in the hopes of improving school performance.15 One study found that 25% to 48% of college students self-referred for ADHD evaluations exaggerated their symptoms.16 In another study, 31% of adults failed the Word Memory Test, which suggests noncredible performance in their ADHD evaluation.17 College students can successfully feign ADHD symptoms in both self-reported symptoms and computer-based tests of attention.18 Harrison et al19 summarized many of these concerns in their 2007 study of ADHD malingering, noting the “almost perfect ability of the Faking group to choose items … that correspond to the DSM-IV symptoms, and to report these at levels even higher than persons with diagnosed ADHD.” They suggested “Clinicians should be suspicious of students or young adults presenting for a first-time diagnosis who rate themselves as being significantly symptomatic, yet have managed to achieve well in school and other life activities.”19

Another challenge in correctly diagnosing adult ADHD is identifying other conditions that may impair attention.20 Psychiatric conditions that may impair concentration include anxiety disorders, chronic stress, posttraumatic stress disorder, recent trauma, major depressive disorder (MDD), and bipolar disorder (BD). Undiagnosed learning disorders may present like ADHD. Focus can be negatively affected by sleep disorders such as sleep apnea, restless leg syndrome, or delayed sleep phase-onset disorder. Marijuana, cocaine, 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA; “ecstasy”), caffeine, or prescription medications such as anticholinergics can also impair attention. Medical conditions that can present with attentional or executive functioning deficits include seizures, Lyme disease, HIV, encephalopathy, hypothyroidism, and “chemo brain.”21 Environmental factors such as age-related cognitive decline, sleep deprivation, inflammation, obesity, air pollution, chemical exposure, and excessive use of digital media may also produce symptoms similar to ADHD. Two studies of adult-onset ADHD concluded that 93% to 95% of cases were better explained by other conditions such as sleep disorders, substance use disorders, or another psychiatric disorder.22

Continue to: Risks associated with treatment

Risks associated with treatment

With or without an accurate ADHD diagnosis, prescribing stimulants presents certain risks (Table 223-40). One of the more well-known risks of stimulants is addiction or misuse.23 An estimated 5 million American adults misused prescription stimulants in 2016.24 Despite stimulants’ status as controlled substances, long-term concurrent use of stimulants with opioids is common among adults with ADHD.25 College students are particularly susceptible to misusing or diverting stimulants, often to improve their academic performance.26 At 1 university, 22% of students had misused stimulants in the past year.27 Prescribing short-acting stimulants (rather than extended-release formulations) increases the likelihood of misuse.28 Patients prescribed stimulants begin to receive requests to divert their medications to others as early as elementary school, and by college more than one-third of those taking stimulants have been asked to give, sell, or trade their medications.29 Diversion of stimulants by students with ADHD is prevalent, with 62% of patients engaging in diversion during their lifetime.15 Diverted stimulants can come from family members, black market sources, or deceived clinicians.30 Although students’ stimulant misuse/diversion often is academically motivated, nonmedical use of psychostimulants does not appear to have a statistically significant effect on improving grade point average.31 Despite a negligible impact on grades, most students who take stimulants identify their effect as strongly positive, producing a situation in which misusers of stimulants have little motivation to stop.32 While some patients might ask for a stimulant prescription with the rationale that liking the effects proves they have ADHD, this is inappropriate because most individuals like the effects of stimulant medications.33

The use of stimulants increases the risk for several adverse psychiatric outcomes. Stimulants increase the risk of anxiety, so exercise caution when prescribing to patients with a comorbid anxiety disorder.34 Stimulants can also worsen irritability and insomnia, 2 issues common among patients with ADHD.32 Use of stimulant medications can trigger manic episodes. Viktorin et al35 found a >6-fold increase in manic episodes among patients with BD receiving methylphenidate monotherapy compared to those receiving a combination of methylphenidate and a mood stabilizer.35 The use of methylphenidate and amphetamine can lead to new-onset psychosis (or exacerbation of pre-existing psychotic illness); amphetamine use is associated with a higher risk of psychosis than methylphenidate.36

General medical adverse effects are also possible with stimulant use. Stimulants’ adverse effect profiles include appetite suppression, dry mouth, and nausea. Long-term use poses a risk for stunting growth in children.1 Using stimulants during pregnancy is associated with higher risk for neonatal morbidity, including preterm birth, CNS-related disorders, and seizures.37 Stimulants can raise blood pressure and increase heart rate. Serious cardiovascular events associated with stimulant use include ventricular arrhythmias, strokes, and transient ischemic attacks.38

Nonstimulant ADHD treatments are less risky than stimulants but still require monitoring for common adverse effects. Atomoxetine has been associated with sedation, growth retardation (in children), and in severe cases, liver injury or suicidal ideation.39 Bupropion (commonly used off-label for ADHD) can lower the seizure threshold and cause irritability, anorexia, and insomnia.39 Viloxazine, a newer agent, can cause hypertension, increased heart rate, nausea, drowsiness, headache, and insomnia.40

Sensible diagnosing

Given the challenges in accurately diagnosing ADHD in adults, we present a sensible approach to making the diagnosis (Table 3). The first step is to rule out other conditions that might better explain the patient’s symptoms. A thorough clinical interview (including a psychiatric review of symptoms) is the cornerstone of an initial diagnostic assessment. The use of validated screening questionnaires such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and General Anxiety Disorder-7 may also provide information regarding psychiatric conditions that require additional evaluation.

Continue to: Some of the most common conditions...

Some of the most common conditions we see mistaken for ADHD are MDD, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), and BD. In DSM-5-TR, 1 of the diagnostic criteria for MDD is “diminished ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness, nearly every day (either by subjective account or as observed by others).”41 Similarly, criteria for GAD include “difficulty concentrating.”42 DSM-5-TR also includes distractibility as one of the criteria for mania/hypomania. Table 420-22,41,42 lists other psychiatric, substance-related, medical, and environmental conditions that can produce ADHD-like symptoms. Referring to some medical and environmental explanations for inattention, Aiken22 pointed out, “Patients who suffer from these problems might ask their doctor for a stimulant, but none of those syndromes require a psychopharmacologic approach.” ADHD can be comorbid with other psychiatric conditions, so the presence of another psychiatric illness does not automatically rule out ADHD. If alternative psychiatric diagnoses have been identified, these can be discussed with the patient and treatment offered that targets the specified condition.

Once alternative explanations have been ruled out, focus on the patient’s developmental history. DSM-5-TR conceptualizes ADHD as a neurodevelopmental disorder, meaning it is expected to emerge early in life. Whereas previous editions of DSM specified that ADHD symptoms must be present before age 7, DSM-5 modified this age threshold to before age 12.1 This necessitates taking a careful life history in order to understand the presence or absence of symptoms at earlier developmental stages.5 ADHD should be verified by symptoms apparent in childhood and present across the lifespan.15

While this retrospective history is necessary, histories that rely on self-report alone are often unreliable. Collateral sources of information are generally more reliable when assessing for ADHD symptoms.13 Third-party sources can help confirm that any impairment is best attributed to ADHD rather than to another condition.15 Unfortunately, the difficulty of obtaining collateral information means it is often neglected, even in the literature.10 A parent is the ideal informant for gathering collateral information regarding a patient’s functioning in childhood.5 Suggested best practices also include obtaining collateral information from interviews with significant others, behavioral questionnaires completed by parents (for current and childhood symptoms), review of school records, and consideration of intellectual and achievement testing.43 If psychological testing is pursued, include validity testing to detect feigned symptoms.18,44

When evaluating for ADHD, assess not only for the presence of symptoms, but also if these symptoms produce significant functional impairment.13,15 Impairments in daily functioning can include impaired school participation, social participation, quality of relationships, family conflict, family activities, family functioning, and emotional functioning.45 Some symptoms may affect functioning in an adult’s life differently than they did during childhood, from missed work appointments to being late picking up kids from school. Research has shown that the correlation between the number of symptoms and functional impairment is weak, which means someone could experience all of the symptoms of ADHD without experiencing functional impairment.45 To make an accurate diagnosis, it is therefore important to clearly establish both the number of symptoms the patient is experiencing and whether these symptoms are clearly linked to functional impairments.10

Sensible treatment

Once a diagnosis of ADHD has been clearly established, clinicians need to consider how best to treat the condition (Table 5). Stimulants are generally considered first-line treatment for ADHD. In randomized clinical trials, they showed significant efficacy; for example, one study of 146 adults with ADHD found a 76% improvement with methylphenidate compared to 19% for the placebo group.46 Before starting a stimulant, certain comorbidities should be ruled out. If a patient has glaucoma or pheochromocytoma, they may first need treatment from or clearance by other specialists. Stimulants should likely be held in patients with hypertension, angina, or cardiovascular defects until receiving medical clearance. The risks of stimulants need to be discussed with female patients of childbearing age, weighing the benefits of treatment against the risks of medication use should the patient get pregnant. Patients with comorbid psychosis or uncontrolled bipolar illness should not receive stimulants due to the risk of exacerbation. Patients with active substance use disorders (SUDs) are generally not good candidates for stimulants because of the risk of misusing or diverting stimulants and the possibility that substance abuse may be causing their inattentive symptoms. Patients whose SUDs are in remission may cautiously be considered as candidates for stimulants. If patients misuse their prescribed stimulants, they should be switched to a nonstimulant medication such as atomoxetine, bupropion, guanfacine, or clonidine.47

Continue to: Once a patient is deemed...

Once a patient is deemed to be a candidate for stimulants, clinicians need to choose between methylphenidate or amphetamine/dextroamphetamine formulations. Table 6 lists medications that are commonly prescribed to treat ADHD; unless otherwise noted, these are FDA-approved for this indication. As a general rule, for adults, long-acting stimulant formulations are preferred over short-acting formulations.28 Immediate-release stimulants are more prone to misuse or diversion compared to extended-release medications.29 Longer-acting formulations may also provide better full-day symptom control.48

In contrast to many other psychiatric medications, it may be beneficial to encourage periodically taking breaks or “medication holidays” from stimulants. Planned medication holidays for adults can involve intentionally not taking the medication over the weekend when the patient is not involved in work or school responsibilities. Such breaks have been shown to reduce adverse effects of stimulants (such as appetite suppression and insomnia) without significantly increasing ADHD symptoms.49 Short breaks can also help prevent medication tolerance and the subsequent need to increase doses.50 Medication holidays provide an opportunity to verify the ongoing benefits of the medication. It is advisable to periodically assess whether there is a continued need for stimulant treatment.51 If patients do not tolerate stimulants or have other contraindications, nonstimulants should be considered.

Lastly, no psychiatric patient should be treated with medication alone, and nonpharmacologic approaches should be incorporated as needed. Clear instructions, visual aids, nonverbal cues, frequent breaks to stand and stretch, schedules, normalizing failure as part of growth, and identifying triggers for emotional reactivity may help patients with ADHD.52 In a study of the academic performance of 92 college students taking medication for ADHD and 146 control students, treatment with stimulants alone did not eliminate the academic achievement deficit of those individuals with ADHD.53 Good study habits (even without stimulants) appeared more important in overcoming the achievement disparity of students with ADHD.53 Providing psychoeducation and training in concrete organization and planning skills have shown benefit.54 Practice of skills on a daily basis appears to be especially beneficial.55

Bottom Line

A sensible approach to diagnosing attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults includes ruling out other disorders that may present similar to ADHD, taking an appropriate developmental history, obtaining collateral information, and assessing for functional impairment. Sensible treatment involves ruling out comorbidities that stimulants could worsen, selecting extended-release stimulants, incorporating medication holidays, and using nonpharmacologic interventions.

Related Resources

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng87

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Advisory: Prescription Stimulant Misuse Among Youth and Young Adults. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/prescription-stimulant-misuse-among-youth-young-adults/PEP21-06-01-003

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine • Adzenys, Dyanavel, others

Atomoxetine • Strattera

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Forfivo

Clonidine • Catapres, Kapvay

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine

Dextroamphetamine and amphetamine • Adderall, Mydayis

Guanfacine • Intuniv, Tenex

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Methylin, others

Viloxazine • Qelbree

1. Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450-462.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:35.

3. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

4. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, et al. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulants in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

5. McGough JJ, Barkley RA. Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1948-1956.

6. Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562-575.

7. Solanto MV. Child vs adult onset of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):421.

8. Jummani RR, Hirsch E, Hirsch GS. Are we overdiagnosing and overtreating ADHD? Psychiatric Times. Published May 31, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/are-we-overdiagnosing-and-overtreating-adhd

9. Sibley MH, Rohde LA, Swanson JM, et al; Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) Cooperative Group. Late-onset ADHD reconsidered with comprehensive repeated assessments between ages 10 and 25. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(2):140-149.

10. Sibley MH, Mitchell JT, Becker SP. Method of adult diagnosis influences estimated persistence of childhood ADHD: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(12):1157-1165.

11. Ustun B, Adler LA, Rudin C, et al. The World Health Organization adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report screening scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(5):520-527.

12. Faraone SV, Biederman J. Can attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder onset occur in adulthood? JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(7):655-656.

13. Sibley MH, Pelham WE, Molina BSG, et al. When diagnosing ADHD in young adults emphasize informant reports, DSM items, and impairment. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80(6):1052-1061.

14. Sollman MJ, Ranseen JD, Berry DT. Detection of feigned ADHD in college students. Psychol Assess. 2010;22(2):325-335.

15. Green AL, Rabiner DL. What do we really know about ADHD in college students? Neurotherapeutics. 2012;9(3):559-568.

16. Sullivan BK, May K, Galbally L. Symptom exaggeration by college adults in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and learning disorder assessments. Appl Neuropsychol. 2007;14(3):189-207.

17. Suhr J, Hammers D, Dobbins-Buckland K, et al. The relationship of malingering test failure to self-reported symptoms and neuropsychological findings in adults referred for ADHD evaluation. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2008;23(5):521-530.

18. Lee Booksh R, Pella RD, Singh AN, et al. Ability of college students to simulate ADHD on objective measures of attention. J Atten Disord. 2010;13(4):325-338.

19. Harrison AG, Edwards MJ, Parker KC. Identifying students faking ADHD: preliminary findings and strategies for detection. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2007;22(5):577-588.

20. Lopez R, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, Galeria C, et al. Is adult-onset attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder frequent in clinical practice? Psychiatry Res. 2017;257:238-241.

21. Bhatia R. Rule out these causes of inattention before diagnosing ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2016;15(10):32-33.

22. Aiken C. Adult-onset ADHD raises questions. Psychiatric Times. 2021;38(3):24.

23. Bjorn S, Weyandt LL. Issues pertaining to misuse of ADHD prescription medications. Psychiatric Times. 2018;35(9):17-19.

24. Compton WM, Han B, Blanco C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of prescription stimulant use, misuse, use disorders, and motivations for misuse among adults in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):741-755.

25. Wei YJ, Zhu Y, Liu W, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with long-term concurrent use of stimulants and opioids among adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(4):e181152. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1152

26. Benson K, Flory K, Humphreys KL, et al. Misuse of stimulant medication among college students: a comprehensive review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2015;18(1):50-76.

27. Benson K, Woodlief DT, Flory K, et al. Is ADHD, independent of ODD, associated with whether and why college students misuse stimulant medication? Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26(5):476-487.

28. Froehlich TE. ADHD medication adherence in college students-- a call to action for clinicians and researchers: commentary on “transition to college and adherence to prescribed attention deficit hyperactivity disorder medication.” J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2018;39(1):77-78.

29. Wilens TE, Adler LA, Adams J, et al. Misuse and diversion of stimulants prescribed for ADHD: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47(1):21-31.

30. Vrecko S. Everyday drug diversions: a qualitative study of the illicit exchange and non-medical use of prescription stimulants on a university campus. Soc Sci Med. 2015;131:297-304.

31. Munro BA, Weyandt LL, Marraccini ME, et al. The relationship between nonmedical use of prescription stimulants, executive functioning and academic outcomes. Addict Behav. 2017;65:250-257.

32. Rabiner DL, Anastopoulos AD, Costello EJ, et al. Motives and perceived consequences of nonmedical ADHD medication use by college students: are students treating themselves for attention problems? J Atten Disord. 2009;13(3)259-270.

33. Tayag Y. Adult ADHD is the wild west of psychiatry. The Atlantic. Published April 14, 2023. Accessed May 3, 2023. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/04/adult-adhd-diagnosis-treatment-adderall-shortage/673719/

34. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270.

35. Viktorin A, Rydén E, Thase ME, et al. The risk of treatment-emergent mania with methylphenidate in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2017;174(4):341-348.

36. Moran LV, Ongur D, Hsu J, et al. Psychosis with methylphenidate or amphetamine in patients with ADHD. N Engl J Med. 2019; 380(12):1128-1138.

37. Nörby U, Winbladh B, Källén K. Perinatal outcomes after treatment with ADHD medication during pregnancy. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20170747. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0747

38. Tadrous M, Shakeri A, Chu C, et al. Assessment of stimulant use and cardiovascular event risks among older adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(10):e2130795. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.30795

39. Daughton JM, Kratochvil CJ. Review of ADHD pharmacotherapies: advantages, disadvantages, and clinical pearls. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(3):240-248.

40. Qelbree [package insert]. Rockville, MD: Supernus Pharmaceuticals; 2021.

41. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:183.

42. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:250.

43. DuPaul GJ, Weyandt LL, O’Dell SM, et al. College students with ADHD: current status and future directions. J Atten Disord. 2009;13(3):234-250.

44. Edmundson M, Berry DTR, Combs HL, et al. The effects of symptom information coaching on the feigning of adult ADHD. Psychol Assess. 2017;29(12):1429-1436.

45. Gordon M, Antshel K, Faraone S, et al. Symptoms versus impairment: the case for respecting DSM-IV’s criterion D. J Atten Disord. 2006;9(3):465-475.

46. Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):456-463.

47. Osser D, Awidi B. Treating adults with ADHD requires special considerations. Psychiatric News. Published August 30, 2018. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.pp8a1

48. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management; Wolraich M, Brown L, Brown, RT, et al. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007-1022.

49. Martins S, Tramontina S, Polanczyk G, et al. Weekend holidays during methylphenidate use in ADHD children: a randomized clinical trial. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2004;14(2):195-206.

50. Ibrahim K, Donyai P. Drug holidays from ADHD medication: international experience over the past four decades. J Atten Disord. 2015;19(7):551-568.

51. Matthijssen AM, Dietrich A, Bierens M, et al. Continued benefits of methylphenidate in ADHD after 2 years in clinical practice: a randomized placebo-controlled discontinuation study. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(9):754-762.

52. Mason EJ, Joshi KG. Nonpharmacologic strategies for helping children with ADHD. Current Psychiatry. 2018;7(1):42,46.

53. Advokat C, Lane SM, Luo C. College students with and without ADHD: comparison of self-report of medication usage, study habits, and academic achievement. J Atten Disord. 2011;15(8):656-666.

54. Knouse LE, Cooper-Vince C, Sprich S, et al. Recent developments in the psychosocial treatment of adult ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1537-1548.

55. Evans SW, Owens JS, Wymbs BT, et al. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):157-198.

1. Posner J, Polanczyk GV, Sonuga-Barke E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2020;395(10222):450-462.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed, text revision. American Psychiatric Association; 2022:35.

3. Chung W, Jiang SF, Paksarian D, et al. Trends in the prevalence and incidence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among adults and children of different racial and ethnic groups. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1914344. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14344

4. Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, et al. Trends in office-based treatment of adults with stimulants in the United States. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(1):43-50.

5. McGough JJ, Barkley RA. Diagnostic controversies in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(11):1948-1956.

6. Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562-575.

7. Solanto MV. Child vs adult onset of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(4):421.

8. Jummani RR, Hirsch E, Hirsch GS. Are we overdiagnosing and overtreating ADHD? Psychiatric Times. Published May 31, 2017. Accessed March 17, 2023. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/are-we-overdiagnosing-and-overtreating-adhd