User login

Home-based care for heart failure: Cleveland Clinic’s “Heart Care at Home” transitional care program

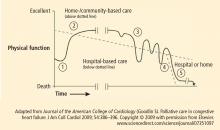

The home is the most important context of care for individuals with chronic heart failure and yet it is the least accessible to caregivers. Patients often struggle to manage a complex regimen of medications, follow an unfamiliar diet, monitor weight and vital signs, and work to coordinate care among various providers who, in some cases, fail to communicate effectively. Heart failure patients do all this while making difficult decisions about their livelihoods, social condition, and future direction. With progression of the disease and comorbidity, these patients often experience a downward cycle of repeat hospitalization and worsening functional capacity (Figure 1). Each subsequent transition from acute care to home becomes incrementally more difficult to manage.

According to the latest American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults, appropriate care for patients with heart failure should include:

- Intensive patient education

- Encouragement of patients to be more aggressive participants in their care

- Close monitoring of patients through telephone follow-up or home nursing

- Careful review of medications to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines

- Multidisciplinary care with nurse case management directed by a physician1

Beyond these general suggestions, recommendations about specific approaches and models of care in the home are lacking.

Contemporary research suggests that postacute, home-based care of heart failure patients may yield outcomes similar to those of clinic-based outpatient care. Results of the Which Heart Failure Intervention is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer-Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care (WHICH?) trial support this hypothesis. This multicenter, randomized clinical trial (n = 280) compared home- with clinic-based multidisciplinary management for postacute heart failure patients.2 Investigators compared outcomes in patients managed at a heart failure clinic with those managed at home. They found that postdischarge home visits by heart failure nurses did not significantly alter the primary composite end point of death or unplanned rehospitalization from any cause over 18 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–1.30, P = .8621). The rate of unplanned and total hospitalization was also similar in the two groups. However, the average length of hospital stay was significantly lower in the home care group (4 days) than in the clinic-based group (6 days); P = .004. A cost-effectiveness analysis is planned but has not yet been presented.

HEART CARE AT HOME

At Cleveland Clinic, our group of physicians (geriatrics and cardiology), nurses, nurse practitioners, and hospital administrators founded a primarily home-based postacute transitional care program in 2010 called “Heart Care at Home.” The design of our program was influenced by Coleman et al’s care transitions interventions program,3 Naylor et al’s transitional care intervention,4 and the contemporary remote monitoring literature.5 The program focuses primarily on older adults hospitalized for heart failure who are transitioning from hospital to home. In our model:

- Inpatient care advocates identify candidates during the index inpatient stay, introduce a model of care, and begin a coaching intervention.

- After discharge, home liaisons visit the patient at home, continue coaching intervention, and teach the patient to use the newly installed remote monitoring equipment.

- For 30 to 40 days after discharge, a team of telehealth nurses monitors the patient, makes contact with him or her weekly in order to reinforce coaching intervention, coordinates care, and tracks outcomes.

- Nurse practitioners experienced both in home care and heart failure provide clinical oversight and leadership and visit the highest-acuity patients at home.

To date, the program has provided care in more than 2,100 patient encounters, with approximately 50 to 80 patients actively enrolled at any time. We identified potential program candidates using a digital list tool embedded in Cleveland Clinic’s electronic medical record (EMR) system. This tool was developed by our team together with an internal business intelligence team. We have been approximately 65% successful in identifying eligible inpatients. Patients enrolled in our transitional care program tend to be older, have longer hospital stays, and have more comorbidities than other older adults hospitalized at Cleveland Clinic for similar reasons.

Following index hospital discharge, our home liaisons have been able to make an initial home visit after a median of 2 days (25th to 75th percentile: 1 to 3 days). Patients thought to be at higher risk for hospital readmissions have been seen at home by our nurse practitioners within the first week of discharge. The most common challenge that our at-home team members have faced relates to patients’ medications (for example, unfilled prescriptions and errors in utilization). On many occasions our at-home team has succeeded in transitioning patients not benefiting from care at home to nonhospital venues (skilled nursing facilities, chronic care facilities, inpatient hospice) or to higher levels of at-home care (at-home physician visits, home-care nursing and therapy, at-home hospice).

To date, patients have been enrolled in our program for a median of 30 days (25th to 75th percentile: 20 to 35 days). We have observed an increased level of patient satisfaction. Among heart failure patients enrolled in our program for the first time, we have observed a lower readmission rate compared with publicly reported Cleveland Clinic rates (24.5% vs 28.2%). However, there are several ongoing challenges in the care of heart failure patients in the home environment. These relate to longitudinal care across venues, cross training of providers, and home monitoring.

Longitudinal care across venues

Our program aims to address the lack of integrated care over time and between care venues. This problem lies at the intersection of health care reimbursement policy and clinical practice. Currently, the hospital reimbursement system does not encourage care coordination across settings. The system has, in fact, evolved into a string of disconnected care providers who act as “toll booths” providing services for a fee in isolation from other providers. Coleman and colleagues have documented the complexity of the transitions among these care providers for older patients with chronic disease, noting the implications for patient safety and cost.6

Hospitals receive a fixed payment for an inpatient admission, which increases the financial incentive to discharge patients faster to other venues of care. The study by Bueno et al of a Medicare population treated between 1993 and 2006 confirms that such a trend exists for heart failure patients.7 The authors found a steady decrease in the mean length of hospital stay from 8.81 days to 6.33 days over the study period (28% relative reduction, P < .001). During this same period, the 30-day all-cause readmission rate increased from 17.2% to 20.1% (a 17% relative increase, P < .001) with an associated 10% relative reduction in the proportion of patients discharged to home.7 Experience in other populations with heart failure, such as patients in the Veterans Affairs health care system, has shown similar trends in length of hospital stay and readmissions.8

During these transitions, information is often lost in the handoff from the discharging hospital to the next venue of care. Medication management is the most common problem area with the potential for patient noncompliance with prescriptions,9,10 which can have serious deleterious effects on quality and safety. Forster et al found that 66% of untoward outcomes in discharged patients were due to adverse drug events.11 Similarly, Gray et al identified adverse drug events in 20% of patients discharged from hospital to home with home health care services.12

In the Cleveland Clinic Health System, we are coupling our “Heart Care at Home” transitional care program with an aggressive plan to develop a more comprehensive cross-venue EMR. Connecting the hospital EMR with our health system–owned home health agency will enable a consistent medication record and communication system for patients transitioning from our hospitals to Cleveland Clinic home care services (nearly 20,000 patients per year).

Despite these issues, several care transition interventions have shown promising clinical and economic results. Coleman and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled trial of a transition coaching model in which patients and caregivers were encouraged to take a more active role in care transitions. Results of this trial showed a significant decrease in 30- and 90-day rehospitalizations (the 90-day read-mission rate in the treatment group was 16.7 vs 22.5 in the control group, P = .04) with associated cost savings.3 Voss et al showed similar results in reduction of readmissions in a nonintegrated delivery system.13 Additionally, telephone-based chronic disease management programs have been shown to be cost-effective in chronically ill Medicare patients.14

When will the clinical evidence behind care transitions and financial incentives converge to create an atmosphere conducive to more optimal care coordination? Today, this question remains unanswered. Health care reform, with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf), may spur the creation of programs to increase incentives for care coordination. These include a move to episodic reimbursement that would bundle payments for acute and postacute care, thus creating more incentives for coordinating care across settings. The “Bundled Payments for Care Improvement” project run by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation will test different models and approaches to bundled payments (http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments). Additionally, beginning in fiscal year 2013, Medicare will penalize hospitals that have high readmission rates for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia with a financial risk of up to 3% of total hospital Medicare payments by year 3 of the program.

The PPACA will have a significant effect on home-based care for older adults with chronic conditions. The PPACA reforms will likely lead to more patients being treated at home (the lower-cost care setting), ideally under the care of highly skilled teams. Payment reforms will also create new incentives for providers to better coordinate care, keep patients healthy at home, and avoid the “toll-booth” description entirely, enabling providers to focus on patient care. However, more research and experimentation are required to streamline the elements on the transitions spectrum in order to create the most value for specific patient populations. New infrastructure, use of technology, changing culture, and dedicated clinical teams will be necessary to deliver on the hopes of more integrated longitudinal care across venues.

Cross training of providers

Older community-dwelling adults with heart failure exhibit more health instability; take more medications; have more comorbidities; and receive more nursing, homemaking, and meal services than do other home care clients.15 Nurses thus have a unique opportunity to improve outcomes for home-based heart failure patients,16,17 but are often insufficiently trained to do so. Delaney et al administered a validated 20-item heart failure knowledge questionnaire to 94 home care nurses from four different home care agencies.18 The investigators found a 79% knowledge level in overall heart failure education principles, with lowest scores related to issues of asymptomatic hypotension (25% answered correctly), daily weight monitoring (27%), and transient dizziness (31%). Nurses with poorer heart failure–related knowledge may partially explain worse process and outcome measures among this patient population.19

The home-based nursing workforce of the future, and specifically nurses who care for heart failure patients at home, will need to be better trained and specialized in issues relating both to home-based nursing and medical heart failure. These “hybrid nurses” should be allowed a central clinical leadership role among their peers, as they will need to be empowered to make medical and care coordination decisions.

At our center, hybrid-trained home care/heart failure nurse practitioners make home visits for higher-acuity home-based patients and provide clinical leadership and support for other home care nurses. These nurse practitioners have been instrumental in identifying and correcting heart failure medication–related problems, as well as effectively coordinating care. Examples include: independently prescribing and coordinating administration of intravenous diuretics at home for patients who have difficulty managing volume overload, avoiding hospital readmissions by transitioning ill patients to a skilled nursing facility or an at-home hospice, and effectively educating patients and families about appropriate heart failure self-care.

Home monitoring

Home monitoring of selected physiologic parameters and patient-reported health status measures among heart failure patients may facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration and direct timely intervention to prevent adverse outcomes.20 Desai and Stevenson have previously proposed the “circle from home to heart-failure disease management,” a concept illustrating how home monitoring can be embedded in a comprehensive heart failure management approach (Figure 2).20 This concept emphasizes the following:

- Home monitoring should facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration.20

- Home monitoring data will most directly lead to action if the data can be used by the patient to improve self-care.

- In the setting of multidisciplinary care, data should be remotely transmitted to a midlevel team, preferably one empowered to make therapeutic decisions.

- Further engagement of physicians or other clinical providers may be beneficial but will delay the clinical response.

The most commonly monitored physiologic parameter of heart failure patients is daily weight. While nearly universally used, this parameter is in fact a poor surrogate for subclinical hemodynamic congestion and has poor diagnostic performance for clinical decompensation. Results are conflicting from studies evaluating the utility of daily body weight measurements in patients with heart failure who are being cared for in the home environment.

In one study, an increase in body weight of > 2 kg over 24 to 72 hours had a 9% sensitivity for detecting clinical deterioration.21 In another study, Chaudhry et al performed a nested case-control trial in 134 patients with heart failure and 134 matched controls referred to a home monitoring system by managed care organizations. The researchers found that increases in body weight were associated with hospitalization for heart failure and that the increases began at least 1 week before admission.22 However, they did not investigate whether the use of this information by clinicians altered outcomes. In a prior randomized clinical trial of symptom monitoring versus transtelephonic body weight monitoring in patients with symptomatic heart failure, the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure trial (n = 280), weight monitoring did not result in improvement in the primary outcome of hospitalizations for heart failure over a 6-month period.23

The ideal monitoring parameters in heart failure patients may include direct hemodynamic measurements from the right ventricular outflow tract,24 pulmonary artery,25 or left atrium,26 using implantable devices. For example, the CHAMPION (CardioMEMS Heart Sensor Allows Monitoring of Pressure to Improve Outcomes in NYHA Class III Patients) trial (n = 550) was a randomized, single-blind, industry-sponsored trial of heart failure management guided by physiologic hemodynamic data derived from a percutaneously inserted pulmonary artery hemodynamic monitor (Champion HF Monitoring System; CardioMEMS, Atlanta, Georgia). The researchers found that monitoring these parameters was associated with a 28% reduction in heart failure–related hospitalizations during the first 6 months (rate 0.32 vs 0.44, HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60–0.85, P = .0002) compared with usual care.25 At 6 months, the freedom from device- or system-related complications was 98.6%.

Despite success in the trial, the US Food and Drug Administration Circulatory System Devices Panel voted against approving the device. The panel was concerned that the e-mail–alert and care systems built into the intervention arm of the trial created bias in favor of the device, and that in a real-world situation it may not be as effective. This demonstrates the ongoing challenges and barriers to adoption of invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

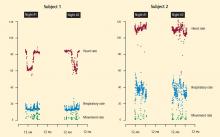

At our center, we are conducting an institutional review board–approved investigation of an entirely noninvasive under-the-mattress piezoelectric monitor in a cohort of postacute heart failure patients. Piezoelectricity is the charge that accumulates in certain solid materials in response to mechanical stress. Common applications of piezoelectricity include microphones, push-start propane barbecues, and cigarette lighters. The device under investigation (EverOn; EarlySense, Ramat-Gan, Israel) detects heart rate, respiratory rate, and movement rate through vibrations of the mattress. Case examples are shown in Figure 3. Whether such monitoring technology will play a future role in the home environment remains to be seen.

SUMMARY

At the time of this writing, the Supreme Court of the United States has reaffirmed the constitutionality of the PPACA, clearing the way for implementation of significant changes in the US health care delivery system. The implications for in-home care for older adults with chronic conditions, including heart failure, are significant. The home will become an increasingly common venue of postacute care. Today is the time to investigate beneficial models of care and optimal uses of technology, and to develop a specialized mobile workforce that will confidently care for individuals with heart failure at home, responsibly and at lower cost.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009; 119:e391–e479.

- Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH, et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective and Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1239–1248.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-J. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:675–684.

- Klersy C, De Silvestri A, Gabutti G, Regoli F, Auricchio A. A meta-analysis of remote monitoring of heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:1683–1694.

- Coleman EA, Min S-J, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Posthospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA 2010; 303:2141–2147.

- Heidenreich PA, Sahay A, Kapoor JR, Pham MX, Massie B. Divergent trends in survival and readmission following a hospitalization for heart failure in the Veterans Affairs health care system 2002 to 2006. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56:362–368.

- Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18:646–651.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min S-J. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1842–1847.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:161–167.

- Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Adverse drug events in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33:1147–1153.

- Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfeld K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1232–1237.

- Baker LC, Johnson SJ, Macaulay D, Birnbaum H. Integrated telehealth and care management program for Medicare benefciaries with chronic disease linked to savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:1689–1697.

- Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, Tyas SL, Tjam EY. A profile of older community-dwelling home care clients with heart failure in Ontario. Chronic Dis Can 2011; 31:49–57.

- Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, et al. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:83–89.

- González B, Lupón J, Herreros J, et al. Patient’s education by nurse: what we really do achieve? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 4:107–111.

- Delaney C, Apostolidis B, Lachapelle L, Fortinsky R. Home care nurses’ knowledge of evidence-based education topics for management of heart failure. Heart Lung 2011; 40:285–292.

- Foebel AD, Heckman GA, Hirdes JP, et al. Clinical, demographic and functional characteristics associated with pharmacotherapy for heart failure in older home care clients: a retrospective, population-level, cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging 2011; 28:561–573.

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Connecting the circle from home to heart-failure disease management. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2364–2367.

- Lewin J, Ledwidge M, O’Loughlin C, McNally C, McDonald K. Clinical deterioration in established heart failure: what is the value of BNP and weight gain in aiding diagnosis? Eur J Heart Fail 2005; 7:953–957.

- Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Concato J, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116:1549–1554.

- Goldberg LR, Piette JD, Walsh MN, et al. Randomized trial of a daily electronic home monitoring system in patients with advanced heart failure: the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure (WHARF) trial. Am Heart J 2003; 146:705–712.

- Bourge RC, Abraham WT, Adamson PB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an implantable continuous hemodynamic monitor in patients with advanced heart failure: the Compass-HF study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51:1073–1079.

- Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:658–666.

- Ritzema J, Troughton R, Melton I, et al. Physician-directed patient self-management of left atrial pressure in advanced chronic heart failure. Circulation 2010; 121:1086–1095.

The home is the most important context of care for individuals with chronic heart failure and yet it is the least accessible to caregivers. Patients often struggle to manage a complex regimen of medications, follow an unfamiliar diet, monitor weight and vital signs, and work to coordinate care among various providers who, in some cases, fail to communicate effectively. Heart failure patients do all this while making difficult decisions about their livelihoods, social condition, and future direction. With progression of the disease and comorbidity, these patients often experience a downward cycle of repeat hospitalization and worsening functional capacity (Figure 1). Each subsequent transition from acute care to home becomes incrementally more difficult to manage.

According to the latest American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults, appropriate care for patients with heart failure should include:

- Intensive patient education

- Encouragement of patients to be more aggressive participants in their care

- Close monitoring of patients through telephone follow-up or home nursing

- Careful review of medications to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines

- Multidisciplinary care with nurse case management directed by a physician1

Beyond these general suggestions, recommendations about specific approaches and models of care in the home are lacking.

Contemporary research suggests that postacute, home-based care of heart failure patients may yield outcomes similar to those of clinic-based outpatient care. Results of the Which Heart Failure Intervention is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer-Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care (WHICH?) trial support this hypothesis. This multicenter, randomized clinical trial (n = 280) compared home- with clinic-based multidisciplinary management for postacute heart failure patients.2 Investigators compared outcomes in patients managed at a heart failure clinic with those managed at home. They found that postdischarge home visits by heart failure nurses did not significantly alter the primary composite end point of death or unplanned rehospitalization from any cause over 18 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–1.30, P = .8621). The rate of unplanned and total hospitalization was also similar in the two groups. However, the average length of hospital stay was significantly lower in the home care group (4 days) than in the clinic-based group (6 days); P = .004. A cost-effectiveness analysis is planned but has not yet been presented.

HEART CARE AT HOME

At Cleveland Clinic, our group of physicians (geriatrics and cardiology), nurses, nurse practitioners, and hospital administrators founded a primarily home-based postacute transitional care program in 2010 called “Heart Care at Home.” The design of our program was influenced by Coleman et al’s care transitions interventions program,3 Naylor et al’s transitional care intervention,4 and the contemporary remote monitoring literature.5 The program focuses primarily on older adults hospitalized for heart failure who are transitioning from hospital to home. In our model:

- Inpatient care advocates identify candidates during the index inpatient stay, introduce a model of care, and begin a coaching intervention.

- After discharge, home liaisons visit the patient at home, continue coaching intervention, and teach the patient to use the newly installed remote monitoring equipment.

- For 30 to 40 days after discharge, a team of telehealth nurses monitors the patient, makes contact with him or her weekly in order to reinforce coaching intervention, coordinates care, and tracks outcomes.

- Nurse practitioners experienced both in home care and heart failure provide clinical oversight and leadership and visit the highest-acuity patients at home.

To date, the program has provided care in more than 2,100 patient encounters, with approximately 50 to 80 patients actively enrolled at any time. We identified potential program candidates using a digital list tool embedded in Cleveland Clinic’s electronic medical record (EMR) system. This tool was developed by our team together with an internal business intelligence team. We have been approximately 65% successful in identifying eligible inpatients. Patients enrolled in our transitional care program tend to be older, have longer hospital stays, and have more comorbidities than other older adults hospitalized at Cleveland Clinic for similar reasons.

Following index hospital discharge, our home liaisons have been able to make an initial home visit after a median of 2 days (25th to 75th percentile: 1 to 3 days). Patients thought to be at higher risk for hospital readmissions have been seen at home by our nurse practitioners within the first week of discharge. The most common challenge that our at-home team members have faced relates to patients’ medications (for example, unfilled prescriptions and errors in utilization). On many occasions our at-home team has succeeded in transitioning patients not benefiting from care at home to nonhospital venues (skilled nursing facilities, chronic care facilities, inpatient hospice) or to higher levels of at-home care (at-home physician visits, home-care nursing and therapy, at-home hospice).

To date, patients have been enrolled in our program for a median of 30 days (25th to 75th percentile: 20 to 35 days). We have observed an increased level of patient satisfaction. Among heart failure patients enrolled in our program for the first time, we have observed a lower readmission rate compared with publicly reported Cleveland Clinic rates (24.5% vs 28.2%). However, there are several ongoing challenges in the care of heart failure patients in the home environment. These relate to longitudinal care across venues, cross training of providers, and home monitoring.

Longitudinal care across venues

Our program aims to address the lack of integrated care over time and between care venues. This problem lies at the intersection of health care reimbursement policy and clinical practice. Currently, the hospital reimbursement system does not encourage care coordination across settings. The system has, in fact, evolved into a string of disconnected care providers who act as “toll booths” providing services for a fee in isolation from other providers. Coleman and colleagues have documented the complexity of the transitions among these care providers for older patients with chronic disease, noting the implications for patient safety and cost.6

Hospitals receive a fixed payment for an inpatient admission, which increases the financial incentive to discharge patients faster to other venues of care. The study by Bueno et al of a Medicare population treated between 1993 and 2006 confirms that such a trend exists for heart failure patients.7 The authors found a steady decrease in the mean length of hospital stay from 8.81 days to 6.33 days over the study period (28% relative reduction, P < .001). During this same period, the 30-day all-cause readmission rate increased from 17.2% to 20.1% (a 17% relative increase, P < .001) with an associated 10% relative reduction in the proportion of patients discharged to home.7 Experience in other populations with heart failure, such as patients in the Veterans Affairs health care system, has shown similar trends in length of hospital stay and readmissions.8

During these transitions, information is often lost in the handoff from the discharging hospital to the next venue of care. Medication management is the most common problem area with the potential for patient noncompliance with prescriptions,9,10 which can have serious deleterious effects on quality and safety. Forster et al found that 66% of untoward outcomes in discharged patients were due to adverse drug events.11 Similarly, Gray et al identified adverse drug events in 20% of patients discharged from hospital to home with home health care services.12

In the Cleveland Clinic Health System, we are coupling our “Heart Care at Home” transitional care program with an aggressive plan to develop a more comprehensive cross-venue EMR. Connecting the hospital EMR with our health system–owned home health agency will enable a consistent medication record and communication system for patients transitioning from our hospitals to Cleveland Clinic home care services (nearly 20,000 patients per year).

Despite these issues, several care transition interventions have shown promising clinical and economic results. Coleman and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled trial of a transition coaching model in which patients and caregivers were encouraged to take a more active role in care transitions. Results of this trial showed a significant decrease in 30- and 90-day rehospitalizations (the 90-day read-mission rate in the treatment group was 16.7 vs 22.5 in the control group, P = .04) with associated cost savings.3 Voss et al showed similar results in reduction of readmissions in a nonintegrated delivery system.13 Additionally, telephone-based chronic disease management programs have been shown to be cost-effective in chronically ill Medicare patients.14

When will the clinical evidence behind care transitions and financial incentives converge to create an atmosphere conducive to more optimal care coordination? Today, this question remains unanswered. Health care reform, with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf), may spur the creation of programs to increase incentives for care coordination. These include a move to episodic reimbursement that would bundle payments for acute and postacute care, thus creating more incentives for coordinating care across settings. The “Bundled Payments for Care Improvement” project run by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation will test different models and approaches to bundled payments (http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments). Additionally, beginning in fiscal year 2013, Medicare will penalize hospitals that have high readmission rates for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia with a financial risk of up to 3% of total hospital Medicare payments by year 3 of the program.

The PPACA will have a significant effect on home-based care for older adults with chronic conditions. The PPACA reforms will likely lead to more patients being treated at home (the lower-cost care setting), ideally under the care of highly skilled teams. Payment reforms will also create new incentives for providers to better coordinate care, keep patients healthy at home, and avoid the “toll-booth” description entirely, enabling providers to focus on patient care. However, more research and experimentation are required to streamline the elements on the transitions spectrum in order to create the most value for specific patient populations. New infrastructure, use of technology, changing culture, and dedicated clinical teams will be necessary to deliver on the hopes of more integrated longitudinal care across venues.

Cross training of providers

Older community-dwelling adults with heart failure exhibit more health instability; take more medications; have more comorbidities; and receive more nursing, homemaking, and meal services than do other home care clients.15 Nurses thus have a unique opportunity to improve outcomes for home-based heart failure patients,16,17 but are often insufficiently trained to do so. Delaney et al administered a validated 20-item heart failure knowledge questionnaire to 94 home care nurses from four different home care agencies.18 The investigators found a 79% knowledge level in overall heart failure education principles, with lowest scores related to issues of asymptomatic hypotension (25% answered correctly), daily weight monitoring (27%), and transient dizziness (31%). Nurses with poorer heart failure–related knowledge may partially explain worse process and outcome measures among this patient population.19

The home-based nursing workforce of the future, and specifically nurses who care for heart failure patients at home, will need to be better trained and specialized in issues relating both to home-based nursing and medical heart failure. These “hybrid nurses” should be allowed a central clinical leadership role among their peers, as they will need to be empowered to make medical and care coordination decisions.

At our center, hybrid-trained home care/heart failure nurse practitioners make home visits for higher-acuity home-based patients and provide clinical leadership and support for other home care nurses. These nurse practitioners have been instrumental in identifying and correcting heart failure medication–related problems, as well as effectively coordinating care. Examples include: independently prescribing and coordinating administration of intravenous diuretics at home for patients who have difficulty managing volume overload, avoiding hospital readmissions by transitioning ill patients to a skilled nursing facility or an at-home hospice, and effectively educating patients and families about appropriate heart failure self-care.

Home monitoring

Home monitoring of selected physiologic parameters and patient-reported health status measures among heart failure patients may facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration and direct timely intervention to prevent adverse outcomes.20 Desai and Stevenson have previously proposed the “circle from home to heart-failure disease management,” a concept illustrating how home monitoring can be embedded in a comprehensive heart failure management approach (Figure 2).20 This concept emphasizes the following:

- Home monitoring should facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration.20

- Home monitoring data will most directly lead to action if the data can be used by the patient to improve self-care.

- In the setting of multidisciplinary care, data should be remotely transmitted to a midlevel team, preferably one empowered to make therapeutic decisions.

- Further engagement of physicians or other clinical providers may be beneficial but will delay the clinical response.

The most commonly monitored physiologic parameter of heart failure patients is daily weight. While nearly universally used, this parameter is in fact a poor surrogate for subclinical hemodynamic congestion and has poor diagnostic performance for clinical decompensation. Results are conflicting from studies evaluating the utility of daily body weight measurements in patients with heart failure who are being cared for in the home environment.

In one study, an increase in body weight of > 2 kg over 24 to 72 hours had a 9% sensitivity for detecting clinical deterioration.21 In another study, Chaudhry et al performed a nested case-control trial in 134 patients with heart failure and 134 matched controls referred to a home monitoring system by managed care organizations. The researchers found that increases in body weight were associated with hospitalization for heart failure and that the increases began at least 1 week before admission.22 However, they did not investigate whether the use of this information by clinicians altered outcomes. In a prior randomized clinical trial of symptom monitoring versus transtelephonic body weight monitoring in patients with symptomatic heart failure, the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure trial (n = 280), weight monitoring did not result in improvement in the primary outcome of hospitalizations for heart failure over a 6-month period.23

The ideal monitoring parameters in heart failure patients may include direct hemodynamic measurements from the right ventricular outflow tract,24 pulmonary artery,25 or left atrium,26 using implantable devices. For example, the CHAMPION (CardioMEMS Heart Sensor Allows Monitoring of Pressure to Improve Outcomes in NYHA Class III Patients) trial (n = 550) was a randomized, single-blind, industry-sponsored trial of heart failure management guided by physiologic hemodynamic data derived from a percutaneously inserted pulmonary artery hemodynamic monitor (Champion HF Monitoring System; CardioMEMS, Atlanta, Georgia). The researchers found that monitoring these parameters was associated with a 28% reduction in heart failure–related hospitalizations during the first 6 months (rate 0.32 vs 0.44, HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60–0.85, P = .0002) compared with usual care.25 At 6 months, the freedom from device- or system-related complications was 98.6%.

Despite success in the trial, the US Food and Drug Administration Circulatory System Devices Panel voted against approving the device. The panel was concerned that the e-mail–alert and care systems built into the intervention arm of the trial created bias in favor of the device, and that in a real-world situation it may not be as effective. This demonstrates the ongoing challenges and barriers to adoption of invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

At our center, we are conducting an institutional review board–approved investigation of an entirely noninvasive under-the-mattress piezoelectric monitor in a cohort of postacute heart failure patients. Piezoelectricity is the charge that accumulates in certain solid materials in response to mechanical stress. Common applications of piezoelectricity include microphones, push-start propane barbecues, and cigarette lighters. The device under investigation (EverOn; EarlySense, Ramat-Gan, Israel) detects heart rate, respiratory rate, and movement rate through vibrations of the mattress. Case examples are shown in Figure 3. Whether such monitoring technology will play a future role in the home environment remains to be seen.

SUMMARY

At the time of this writing, the Supreme Court of the United States has reaffirmed the constitutionality of the PPACA, clearing the way for implementation of significant changes in the US health care delivery system. The implications for in-home care for older adults with chronic conditions, including heart failure, are significant. The home will become an increasingly common venue of postacute care. Today is the time to investigate beneficial models of care and optimal uses of technology, and to develop a specialized mobile workforce that will confidently care for individuals with heart failure at home, responsibly and at lower cost.

The home is the most important context of care for individuals with chronic heart failure and yet it is the least accessible to caregivers. Patients often struggle to manage a complex regimen of medications, follow an unfamiliar diet, monitor weight and vital signs, and work to coordinate care among various providers who, in some cases, fail to communicate effectively. Heart failure patients do all this while making difficult decisions about their livelihoods, social condition, and future direction. With progression of the disease and comorbidity, these patients often experience a downward cycle of repeat hospitalization and worsening functional capacity (Figure 1). Each subsequent transition from acute care to home becomes incrementally more difficult to manage.

According to the latest American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Heart Failure in Adults, appropriate care for patients with heart failure should include:

- Intensive patient education

- Encouragement of patients to be more aggressive participants in their care

- Close monitoring of patients through telephone follow-up or home nursing

- Careful review of medications to improve adherence to evidence-based guidelines

- Multidisciplinary care with nurse case management directed by a physician1

Beyond these general suggestions, recommendations about specific approaches and models of care in the home are lacking.

Contemporary research suggests that postacute, home-based care of heart failure patients may yield outcomes similar to those of clinic-based outpatient care. Results of the Which Heart Failure Intervention is Most Cost-Effective & Consumer-Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care (WHICH?) trial support this hypothesis. This multicenter, randomized clinical trial (n = 280) compared home- with clinic-based multidisciplinary management for postacute heart failure patients.2 Investigators compared outcomes in patients managed at a heart failure clinic with those managed at home. They found that postdischarge home visits by heart failure nurses did not significantly alter the primary composite end point of death or unplanned rehospitalization from any cause over 18 months (hazard ratio [HR] 0.97, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.73–1.30, P = .8621). The rate of unplanned and total hospitalization was also similar in the two groups. However, the average length of hospital stay was significantly lower in the home care group (4 days) than in the clinic-based group (6 days); P = .004. A cost-effectiveness analysis is planned but has not yet been presented.

HEART CARE AT HOME

At Cleveland Clinic, our group of physicians (geriatrics and cardiology), nurses, nurse practitioners, and hospital administrators founded a primarily home-based postacute transitional care program in 2010 called “Heart Care at Home.” The design of our program was influenced by Coleman et al’s care transitions interventions program,3 Naylor et al’s transitional care intervention,4 and the contemporary remote monitoring literature.5 The program focuses primarily on older adults hospitalized for heart failure who are transitioning from hospital to home. In our model:

- Inpatient care advocates identify candidates during the index inpatient stay, introduce a model of care, and begin a coaching intervention.

- After discharge, home liaisons visit the patient at home, continue coaching intervention, and teach the patient to use the newly installed remote monitoring equipment.

- For 30 to 40 days after discharge, a team of telehealth nurses monitors the patient, makes contact with him or her weekly in order to reinforce coaching intervention, coordinates care, and tracks outcomes.

- Nurse practitioners experienced both in home care and heart failure provide clinical oversight and leadership and visit the highest-acuity patients at home.

To date, the program has provided care in more than 2,100 patient encounters, with approximately 50 to 80 patients actively enrolled at any time. We identified potential program candidates using a digital list tool embedded in Cleveland Clinic’s electronic medical record (EMR) system. This tool was developed by our team together with an internal business intelligence team. We have been approximately 65% successful in identifying eligible inpatients. Patients enrolled in our transitional care program tend to be older, have longer hospital stays, and have more comorbidities than other older adults hospitalized at Cleveland Clinic for similar reasons.

Following index hospital discharge, our home liaisons have been able to make an initial home visit after a median of 2 days (25th to 75th percentile: 1 to 3 days). Patients thought to be at higher risk for hospital readmissions have been seen at home by our nurse practitioners within the first week of discharge. The most common challenge that our at-home team members have faced relates to patients’ medications (for example, unfilled prescriptions and errors in utilization). On many occasions our at-home team has succeeded in transitioning patients not benefiting from care at home to nonhospital venues (skilled nursing facilities, chronic care facilities, inpatient hospice) or to higher levels of at-home care (at-home physician visits, home-care nursing and therapy, at-home hospice).

To date, patients have been enrolled in our program for a median of 30 days (25th to 75th percentile: 20 to 35 days). We have observed an increased level of patient satisfaction. Among heart failure patients enrolled in our program for the first time, we have observed a lower readmission rate compared with publicly reported Cleveland Clinic rates (24.5% vs 28.2%). However, there are several ongoing challenges in the care of heart failure patients in the home environment. These relate to longitudinal care across venues, cross training of providers, and home monitoring.

Longitudinal care across venues

Our program aims to address the lack of integrated care over time and between care venues. This problem lies at the intersection of health care reimbursement policy and clinical practice. Currently, the hospital reimbursement system does not encourage care coordination across settings. The system has, in fact, evolved into a string of disconnected care providers who act as “toll booths” providing services for a fee in isolation from other providers. Coleman and colleagues have documented the complexity of the transitions among these care providers for older patients with chronic disease, noting the implications for patient safety and cost.6

Hospitals receive a fixed payment for an inpatient admission, which increases the financial incentive to discharge patients faster to other venues of care. The study by Bueno et al of a Medicare population treated between 1993 and 2006 confirms that such a trend exists for heart failure patients.7 The authors found a steady decrease in the mean length of hospital stay from 8.81 days to 6.33 days over the study period (28% relative reduction, P < .001). During this same period, the 30-day all-cause readmission rate increased from 17.2% to 20.1% (a 17% relative increase, P < .001) with an associated 10% relative reduction in the proportion of patients discharged to home.7 Experience in other populations with heart failure, such as patients in the Veterans Affairs health care system, has shown similar trends in length of hospital stay and readmissions.8

During these transitions, information is often lost in the handoff from the discharging hospital to the next venue of care. Medication management is the most common problem area with the potential for patient noncompliance with prescriptions,9,10 which can have serious deleterious effects on quality and safety. Forster et al found that 66% of untoward outcomes in discharged patients were due to adverse drug events.11 Similarly, Gray et al identified adverse drug events in 20% of patients discharged from hospital to home with home health care services.12

In the Cleveland Clinic Health System, we are coupling our “Heart Care at Home” transitional care program with an aggressive plan to develop a more comprehensive cross-venue EMR. Connecting the hospital EMR with our health system–owned home health agency will enable a consistent medication record and communication system for patients transitioning from our hospitals to Cleveland Clinic home care services (nearly 20,000 patients per year).

Despite these issues, several care transition interventions have shown promising clinical and economic results. Coleman and colleagues conducted a randomized, controlled trial of a transition coaching model in which patients and caregivers were encouraged to take a more active role in care transitions. Results of this trial showed a significant decrease in 30- and 90-day rehospitalizations (the 90-day read-mission rate in the treatment group was 16.7 vs 22.5 in the control group, P = .04) with associated cost savings.3 Voss et al showed similar results in reduction of readmissions in a nonintegrated delivery system.13 Additionally, telephone-based chronic disease management programs have been shown to be cost-effective in chronically ill Medicare patients.14

When will the clinical evidence behind care transitions and financial incentives converge to create an atmosphere conducive to more optimal care coordination? Today, this question remains unanswered. Health care reform, with the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) (http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf), may spur the creation of programs to increase incentives for care coordination. These include a move to episodic reimbursement that would bundle payments for acute and postacute care, thus creating more incentives for coordinating care across settings. The “Bundled Payments for Care Improvement” project run by the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Innovation will test different models and approaches to bundled payments (http://innovations.cms.gov/initiatives/bundled-payments). Additionally, beginning in fiscal year 2013, Medicare will penalize hospitals that have high readmission rates for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, and pneumonia with a financial risk of up to 3% of total hospital Medicare payments by year 3 of the program.

The PPACA will have a significant effect on home-based care for older adults with chronic conditions. The PPACA reforms will likely lead to more patients being treated at home (the lower-cost care setting), ideally under the care of highly skilled teams. Payment reforms will also create new incentives for providers to better coordinate care, keep patients healthy at home, and avoid the “toll-booth” description entirely, enabling providers to focus on patient care. However, more research and experimentation are required to streamline the elements on the transitions spectrum in order to create the most value for specific patient populations. New infrastructure, use of technology, changing culture, and dedicated clinical teams will be necessary to deliver on the hopes of more integrated longitudinal care across venues.

Cross training of providers

Older community-dwelling adults with heart failure exhibit more health instability; take more medications; have more comorbidities; and receive more nursing, homemaking, and meal services than do other home care clients.15 Nurses thus have a unique opportunity to improve outcomes for home-based heart failure patients,16,17 but are often insufficiently trained to do so. Delaney et al administered a validated 20-item heart failure knowledge questionnaire to 94 home care nurses from four different home care agencies.18 The investigators found a 79% knowledge level in overall heart failure education principles, with lowest scores related to issues of asymptomatic hypotension (25% answered correctly), daily weight monitoring (27%), and transient dizziness (31%). Nurses with poorer heart failure–related knowledge may partially explain worse process and outcome measures among this patient population.19

The home-based nursing workforce of the future, and specifically nurses who care for heart failure patients at home, will need to be better trained and specialized in issues relating both to home-based nursing and medical heart failure. These “hybrid nurses” should be allowed a central clinical leadership role among their peers, as they will need to be empowered to make medical and care coordination decisions.

At our center, hybrid-trained home care/heart failure nurse practitioners make home visits for higher-acuity home-based patients and provide clinical leadership and support for other home care nurses. These nurse practitioners have been instrumental in identifying and correcting heart failure medication–related problems, as well as effectively coordinating care. Examples include: independently prescribing and coordinating administration of intravenous diuretics at home for patients who have difficulty managing volume overload, avoiding hospital readmissions by transitioning ill patients to a skilled nursing facility or an at-home hospice, and effectively educating patients and families about appropriate heart failure self-care.

Home monitoring

Home monitoring of selected physiologic parameters and patient-reported health status measures among heart failure patients may facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration and direct timely intervention to prevent adverse outcomes.20 Desai and Stevenson have previously proposed the “circle from home to heart-failure disease management,” a concept illustrating how home monitoring can be embedded in a comprehensive heart failure management approach (Figure 2).20 This concept emphasizes the following:

- Home monitoring should facilitate early detection of clinical deterioration.20

- Home monitoring data will most directly lead to action if the data can be used by the patient to improve self-care.

- In the setting of multidisciplinary care, data should be remotely transmitted to a midlevel team, preferably one empowered to make therapeutic decisions.

- Further engagement of physicians or other clinical providers may be beneficial but will delay the clinical response.

The most commonly monitored physiologic parameter of heart failure patients is daily weight. While nearly universally used, this parameter is in fact a poor surrogate for subclinical hemodynamic congestion and has poor diagnostic performance for clinical decompensation. Results are conflicting from studies evaluating the utility of daily body weight measurements in patients with heart failure who are being cared for in the home environment.

In one study, an increase in body weight of > 2 kg over 24 to 72 hours had a 9% sensitivity for detecting clinical deterioration.21 In another study, Chaudhry et al performed a nested case-control trial in 134 patients with heart failure and 134 matched controls referred to a home monitoring system by managed care organizations. The researchers found that increases in body weight were associated with hospitalization for heart failure and that the increases began at least 1 week before admission.22 However, they did not investigate whether the use of this information by clinicians altered outcomes. In a prior randomized clinical trial of symptom monitoring versus transtelephonic body weight monitoring in patients with symptomatic heart failure, the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure trial (n = 280), weight monitoring did not result in improvement in the primary outcome of hospitalizations for heart failure over a 6-month period.23

The ideal monitoring parameters in heart failure patients may include direct hemodynamic measurements from the right ventricular outflow tract,24 pulmonary artery,25 or left atrium,26 using implantable devices. For example, the CHAMPION (CardioMEMS Heart Sensor Allows Monitoring of Pressure to Improve Outcomes in NYHA Class III Patients) trial (n = 550) was a randomized, single-blind, industry-sponsored trial of heart failure management guided by physiologic hemodynamic data derived from a percutaneously inserted pulmonary artery hemodynamic monitor (Champion HF Monitoring System; CardioMEMS, Atlanta, Georgia). The researchers found that monitoring these parameters was associated with a 28% reduction in heart failure–related hospitalizations during the first 6 months (rate 0.32 vs 0.44, HR 0.72, 95% CI 0.60–0.85, P = .0002) compared with usual care.25 At 6 months, the freedom from device- or system-related complications was 98.6%.

Despite success in the trial, the US Food and Drug Administration Circulatory System Devices Panel voted against approving the device. The panel was concerned that the e-mail–alert and care systems built into the intervention arm of the trial created bias in favor of the device, and that in a real-world situation it may not be as effective. This demonstrates the ongoing challenges and barriers to adoption of invasive hemodynamic monitoring.

At our center, we are conducting an institutional review board–approved investigation of an entirely noninvasive under-the-mattress piezoelectric monitor in a cohort of postacute heart failure patients. Piezoelectricity is the charge that accumulates in certain solid materials in response to mechanical stress. Common applications of piezoelectricity include microphones, push-start propane barbecues, and cigarette lighters. The device under investigation (EverOn; EarlySense, Ramat-Gan, Israel) detects heart rate, respiratory rate, and movement rate through vibrations of the mattress. Case examples are shown in Figure 3. Whether such monitoring technology will play a future role in the home environment remains to be seen.

SUMMARY

At the time of this writing, the Supreme Court of the United States has reaffirmed the constitutionality of the PPACA, clearing the way for implementation of significant changes in the US health care delivery system. The implications for in-home care for older adults with chronic conditions, including heart failure, are significant. The home will become an increasingly common venue of postacute care. Today is the time to investigate beneficial models of care and optimal uses of technology, and to develop a specialized mobile workforce that will confidently care for individuals with heart failure at home, responsibly and at lower cost.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009; 119:e391–e479.

- Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH, et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective and Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1239–1248.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-J. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:675–684.

- Klersy C, De Silvestri A, Gabutti G, Regoli F, Auricchio A. A meta-analysis of remote monitoring of heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:1683–1694.

- Coleman EA, Min S-J, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Posthospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA 2010; 303:2141–2147.

- Heidenreich PA, Sahay A, Kapoor JR, Pham MX, Massie B. Divergent trends in survival and readmission following a hospitalization for heart failure in the Veterans Affairs health care system 2002 to 2006. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56:362–368.

- Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18:646–651.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min S-J. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1842–1847.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:161–167.

- Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Adverse drug events in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33:1147–1153.

- Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfeld K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1232–1237.

- Baker LC, Johnson SJ, Macaulay D, Birnbaum H. Integrated telehealth and care management program for Medicare benefciaries with chronic disease linked to savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:1689–1697.

- Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, Tyas SL, Tjam EY. A profile of older community-dwelling home care clients with heart failure in Ontario. Chronic Dis Can 2011; 31:49–57.

- Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, et al. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:83–89.

- González B, Lupón J, Herreros J, et al. Patient’s education by nurse: what we really do achieve? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 4:107–111.

- Delaney C, Apostolidis B, Lachapelle L, Fortinsky R. Home care nurses’ knowledge of evidence-based education topics for management of heart failure. Heart Lung 2011; 40:285–292.

- Foebel AD, Heckman GA, Hirdes JP, et al. Clinical, demographic and functional characteristics associated with pharmacotherapy for heart failure in older home care clients: a retrospective, population-level, cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging 2011; 28:561–573.

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Connecting the circle from home to heart-failure disease management. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2364–2367.

- Lewin J, Ledwidge M, O’Loughlin C, McNally C, McDonald K. Clinical deterioration in established heart failure: what is the value of BNP and weight gain in aiding diagnosis? Eur J Heart Fail 2005; 7:953–957.

- Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Concato J, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116:1549–1554.

- Goldberg LR, Piette JD, Walsh MN, et al. Randomized trial of a daily electronic home monitoring system in patients with advanced heart failure: the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure (WHARF) trial. Am Heart J 2003; 146:705–712.

- Bourge RC, Abraham WT, Adamson PB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an implantable continuous hemodynamic monitor in patients with advanced heart failure: the Compass-HF study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51:1073–1079.

- Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:658–666.

- Ritzema J, Troughton R, Melton I, et al. Physician-directed patient self-management of left atrial pressure in advanced chronic heart failure. Circulation 2010; 121:1086–1095.

- Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, et al. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2009; 119:e391–e479.

- Stewart S, Carrington MJ, Marwick TH, et al. Impact of home versus clinic-based management of chronic heart failure: the WHICH? (Which Heart Failure Intervention Is Most Cost-Effective and Consumer Friendly in Reducing Hospital Care) multicenter, randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60:1239–1248.

- Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min S-J. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 2006; 166:1822–1828.

- Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, Maislin G, McCauley KM, Schwartz JS. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004; 52:675–684.

- Klersy C, De Silvestri A, Gabutti G, Regoli F, Auricchio A. A meta-analysis of remote monitoring of heart failure patients. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:1683–1694.

- Coleman EA, Min S-J, Chomiak A, Kramer AM. Posthospital care transitions: patterns, complications, and risk identification. Health Serv Res 2004; 39:1449–1465.

- Bueno H, Ross JS, Wang Y, et al. Trends in length of stay and short-term outcomes among Medicare patients hospitalized for heart failure, 1993–2006. JAMA 2010; 303:2141–2147.

- Heidenreich PA, Sahay A, Kapoor JR, Pham MX, Massie B. Divergent trends in survival and readmission following a hospitalization for heart failure in the Veterans Affairs health care system 2002 to 2006. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 56:362–368.

- Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003; 18:646–651.

- Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min S-J. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165:1842–1847.

- Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003; 138:161–167.

- Gray SL, Mahoney JE, Blough DK. Adverse drug events in elderly patients receiving home health services following hospital discharge. Ann Pharmacother 1999; 33:1147–1153.

- Voss R, Gardner R, Baier R, Butterfeld K, Lehrman S, Gravenstein S. The care transitions intervention: translating from efficacy to effectiveness. Arch Intern Med 2011; 171:1232–1237.

- Baker LC, Johnson SJ, Macaulay D, Birnbaum H. Integrated telehealth and care management program for Medicare benefciaries with chronic disease linked to savings. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30:1689–1697.

- Foebel AD, Hirdes JP, Heckman GA, Tyas SL, Tjam EY. A profile of older community-dwelling home care clients with heart failure in Ontario. Chronic Dis Can 2011; 31:49–57.

- Krumholz HM, Amatruda J, Smith GL, et al. Randomized trial of an education and support intervention to prevent readmission of patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol 2002; 39:83–89.

- González B, Lupón J, Herreros J, et al. Patient’s education by nurse: what we really do achieve? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2005; 4:107–111.

- Delaney C, Apostolidis B, Lachapelle L, Fortinsky R. Home care nurses’ knowledge of evidence-based education topics for management of heart failure. Heart Lung 2011; 40:285–292.

- Foebel AD, Heckman GA, Hirdes JP, et al. Clinical, demographic and functional characteristics associated with pharmacotherapy for heart failure in older home care clients: a retrospective, population-level, cross-sectional study. Drugs Aging 2011; 28:561–573.

- Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Connecting the circle from home to heart-failure disease management. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2364–2367.

- Lewin J, Ledwidge M, O’Loughlin C, McNally C, McDonald K. Clinical deterioration in established heart failure: what is the value of BNP and weight gain in aiding diagnosis? Eur J Heart Fail 2005; 7:953–957.

- Chaudhry SI, Wang Y, Concato J, Gill TM, Krumholz HM. Patterns of weight change preceding hospitalization for heart failure. Circulation 2007; 116:1549–1554.

- Goldberg LR, Piette JD, Walsh MN, et al. Randomized trial of a daily electronic home monitoring system in patients with advanced heart failure: the Weight Monitoring in Heart Failure (WHARF) trial. Am Heart J 2003; 146:705–712.

- Bourge RC, Abraham WT, Adamson PB, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an implantable continuous hemodynamic monitor in patients with advanced heart failure: the Compass-HF study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008; 51:1073–1079.

- Abraham WT, Adamson PB, Bourge RC, et al. Wireless pulmonary artery haemodynamic monitoring in chronic heart failure: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377:658–666.

- Ritzema J, Troughton R, Melton I, et al. Physician-directed patient self-management of left atrial pressure in advanced chronic heart failure. Circulation 2010; 121:1086–1095.