User login

The confused binge drinker

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

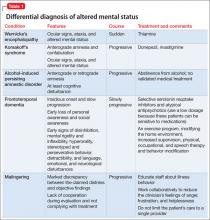

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

CASE Paranoid and confused

Mr. P, age 46, presents to the emergency department (ED) with a chief complaint of feeling “very weird.” Although he has seen a number of psychiatrists in the past, he does not recall being given a specific diagnosis. He describes his feelings as “1 minute I am fine and the next minute I am confused.” He endorses feeling paranoid for the past 6 to 12 months and reports a history of passive suicidal ideations. On the day he presents to the ED, however, he has a specific plan to shoot himself. He does not report audiovisual hallucinations, but has noticed that he talks to himself often.

Mr. P reports feeling worthless at times. He has a history of manic symptoms, including decreased need for sleep and hypersexuality. He describes verbal and sexual abuse by his foster parents. Mr. P reports using Cannabis and opioids occasionally and to drinking every “now and then” but not every day. He denies using benzodiazepines. When he is evaluated, he is not taking any medication and has no significant medical problems. Mr. P reports a history of several hospitalizations, but he could not describe the reasons or timing of past admissions.

Mr. P has a 10th-grade education. He lives with his fiancée, who reports that he has been behaving oddly for some time. She noticed that he has memory problems and describes violent behavior, such as shaking his fist at her, breaking the television, and attempting to cut his throat once when he was “intoxicated.” She says she does not feel safe around him because of his labile mood and history of

aggression. She confirms that Mr. P does not drink daily but binge-drinks at times.

Initial mental status examination of evaluation reveals hyperverbal, rapid speech. Mr. P is circumstantial and tangential in his thought process. He has poor judgment and insight and exhibits suicidal ideations with a plan. Toxicology screening reveals a blood alcohol level of 50 mg/dL and is positive for Cannabis and opiates.

Which condition most likely accounts for Mr. P’s presentation?

a) bipolar disorder, currently manic

b) substance-induced mood disorder

c) cognitive disorder

d) delirium

TREATMENT Rapid improvement

From the ED, Mr. P was admitted to an inpatient psychiatric unit, where he was found initially to be disoriented to time, place, and person. His thought process remained disorganized and irrational, with significant memory difficulties. He is noted to have an unsteady gait. Nursing staff observes that Mr. P has significant difficulties with activities of daily living and requires assistance. He talks in circles

and uses nonsensical words.

His serum vitamin B12 level, folate level, rapid plasma reagin, magnesium level, and thiamine level are within normal limits; CT scan of the brain is unremarkable. Neuropsychological testing reveals significant and diffuse cognitive deficits suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. He is deemed to not have decision-making capacity; because he has no family, his fiancée is appointed as his temporary health care proxy.

Thiamine and lorazepam are prescribed as needed because of Mr. P’s history of alcohol abuse. However, it’s determined that he does not need lorazepam because his vital signs are stable and there is no evidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms.

During the course of his 10-day hospitalization, Mr. P’s cognitive difficulties resolved. He regains orientation to time, place, and person. He gains skill in all his activities of daily living, to the point of independence, and is discharged with minimal supervision. Vitamin B supplementation is prescribed, with close follow up in an outpatient day program. MRI/SPECT scan is considered to rule out frontotemporal dementia as recommended by the results of his neurocognitive testing profile.

Which condition likely account for Mr. P’s presentation during inpatient hospitalization?

a) Wernicke’s encephalopathy

b) Korsakoff’s syndrome

c) malingering

d) frontotemporal dementia

e) a neurodegenerative disease

The author's observations

Mr. P’s fluctuating mental status, gait instability, and confabulation create high suspicion for Wernicke’s encephalopathy; his dramatic improvement with IV thiamine supports that diagnosis. Mr. P attends the outpatient day program once after his discharge, and is then lost to follow-up.

During inpatient stay, Mr. P eventually admits to binge drinking several times a week, and drinking early in the morning, which would continue throughout the day. His significant cognitive deficits revealed by neuropsychological testing suggests consideration of a differential diagnosis of multifactorial cognitive dysfunction because of:

• long-term substance use

• Korsakoff’s syndrome

• frontotemporal dementia

• a neurodegenerative disease

• malingering (Table 1).

Wernicke’s encephalopathy

Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a life-threatening neurologic disorder caused by thiamine deficiency. The disease is rare, catastrophic in onset, and clinically complex1; as in Mr. P’s case, diagnosis often is delayed. In autopsy studies, the reported prevalence of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is 0.4% to 2.8%.1 Wernicke’s encephalopathy was suspected before death in 33% of alcohol-dependent patientsand 6% of nonalcoholics.1 Other causes of Wernicke’s encephalopathy include cancer, gastrointestinal surgery, hyperemesis gravidarum, a starvation or malnutrition state, GI tract disease, AIDS, parenteral nutrition, repetitive vomiting, and infection.1

Diagnosis. Making the correct diagnosis is challenging because the clinical presentation can be variable. No lab or imaging studies confirm the diagnosis. The triad of signs considered to support the diagnosis include ocular signs such as nystagmus, cerebellar signs, and confusion. These signs occur in only 8% to 10% of patients in whom the diagnosis likely.1,2

Attempts to increase the likelihood of making an accurate lifetime diagnosis of

Wernicke’s encephalopathy include expanding the focus to 8 clinical domains:

• dietary deficiency

• eye signs

• cerebellar signs

• seizures

• frontal lobe dysfunction

• amnesia

• mild memory impairment

• altered mental status.1

The sensitivity of making a correct diagnosis increases to 85% if at least 2 of 4 features—namely dietary deficiency, eye signs, cerebellar signs, memory impairment, and altered mental status—are present. These criteria can be applied to alcoholic and nonalcoholic patients.1Table 23 lists common and uncommon symptoms of Wernicke’s encephalopathy.

Although CT scan of the brain is not a reliable test for the disorder, MRI can be powerful tool that could support a diagnosis of acute Wernicke’s encephalopathy.1 We did not consider MRI in Mr. P’s case because the consulting neurologist thought this was unnecessary because of the quick improvement in his cognitive status with IV thiamine—although MRI might have helped to detect the disease earlier. In some studies, brain MRI revealed lesions in two-thirds of Wernicke’s encephalopathy patients.1 Typically, lesions are symmetrical and seen in the thalamus, mammillary body, and periaqueductal areas.1,4 Atypical lesions commonly are seen in the cerebellum, dentate nuclei, caudate nucleus, and cerebral cortex.1

Treatment. Evidence supports use of IV thiamine, 200 mg 3 times a day, when the disease is suspected or established.1,2 Thiamine has been associated with sporadic anaphylactic reactions, and should be administered when resuscitation facilities are available. Do not delay treatment because resuscitation measures are unavailable because you risk causing irreversible brain damage.1

In Mr. P’s case, prompt recognition of the need for thiamine likely led to a better outcome. Thiamine supplementation can prevent Wernicke’s encephalopathy in some patients. Prophylactic parenteral administration of thiamine before administration of glucose in the ED is recommended, as well as vitamin B supplementation with thiamine included upon discharge.1,2 Studies support several treatment regimens for patients with Wernicke’s encephalopathy and those at risk of it.1,3,5

Neither the optimal dosage of thiamine nor the appropriate duration of treatment have been determined by randomized, double-blind, controlled studies; empirical clinical practice and recommendations by Royal College of Physicians, London, suggest that a more prolonged course of thiamine—administered as long as improvement continues—might be beneficial.6

Left untreated, Wernicke’s encephalopathy can lead to irreversible brain damage.2

Mortality has been reported as 17% to 20%; 82% of patients develop Korsakoff’s syndrome, a chronic condition characterized by short-term memory loss. One-quarter of patients who develop Korsakoff’s syndrome require long-term residential care because of permanent brain damage.2

Making a diagnosis of Wernicke’s encephalopathy is a challenge because no specific symptom or diagnostic test can be relied upon to confirm the diagnosis. Also, patients might deny that they have an alcohol problem or give an inaccurate history of their alcohol use,2 as Mr. P did. The disorder is substantially underdiagnosed; as a consequence, patients are at risk of brain damage.2

Bottom Line

Not all patients who present with aggressive behavior, mania, and psychiatric

symptoms have a primary psychiatric diagnosis. It is important to consider

nutritional deficiencies caused by chronic alcohol abuse in patients presenting

with acute onset of confusion or altered mental status. Wernicke’s encephalopathy

might be the result of alcohol abuse and can be treated with IV thiamine.

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationships with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.

1. Galvin R, Bråthen G, Ivashynka A, et al; EFNS. Guidelines for diagnosis, therapy and prevention of Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(12):

1408-1418.

2. Robinson K. Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Emerg Nurse. 2003;11(5):30-33.

3. Sechi G, Serra A. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: new clinical settings and recent advances in diagnosis and management. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(5):442-455.

4. Celik Y, Kaya M. Brain SPECT findings in Wernicke’s encephalopathy. Neurol Sci. 2004;25(1):23-26.

5. Thomson AD, Guerrini I, Marshall JE. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: role of thiamine. Practical Gastroenterology. 2009;33(6):21-30.

6. Thomson AD, Cook CCH, Guerrini I, et al. Wernicke’s encephalopathy: ‘plus ca change, plus c’est la meme chose’. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008;43:180-186.