User login

More on prescribing controlled substances

I was disheartened with the June 2023 issue of

The benzodiazepine pharmacology discussed in this article is interesting, but it would be helpful if it had been integrated within a much more extensive discussion of careful prescribing practices. In 2020, the FDA updated the boxed warning to alert prescribers to the serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with benzodiazepines.2 I would hope that an article on benzodiazepines would provide more discussion and guidance surrounding these important issues.

The June 2023 issue also included “High-dose stimulants for adult ADHD” (p. 34-39, doi:10.12788/cp.0366). This article provided esoteric advice on managing stimulant therapy in the setting of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, yet I would regard stimulant misuse as a far more common and pressing issue.3,4 The recent Drug Enforcement Administration investigation of telehealth stimulant prescribing is a notable example of this problem.5

The patient discussed in this article was receiving large doses of stimulants for a purported case of refractory attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The article provided a sparse differential diagnosis for the patient’s intractable symptoms. While rapid metabolism may be an explanation, I would also like to know how the authors ruled out physiological dependence and/or addiction to a controlled substance. How was misuse excluded? Was urine drug testing (UDS) performed? UDS is highly irregular among prescribers,6 which suggests that practices for detecting covert substance abuse and stimulant misuse are inadequate. Wouldn’t such investigations be fundamental to ethical stimulant prescribing?

Jeff Sanders, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines—38 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7034a2.htm

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requiring boxed warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class

3. McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Wilens TE, et al. Prescription stimulant medical and nonmedical use among US secondary school students, 2005 to 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e238707. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.8707

4. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA updating warnings to improve safe use of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fda-updating-warnings-improve-safe-use-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

5. Vaidya A. Report: telehealth company’s prescribing practices come under DEA scrutiny. September 16, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/report-telehealth-company-dones-prescribing-practices-come-under-dea-scrutiny

6. Zionts A. Some ADHD patients are drug-tested often, while others are never asked. Kaiser Health News. March 25, 2023. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna76330

Continue to: Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

We thank Dr. Sanders for highlighting the need for clinical equipoise in considering the risks and benefits of medications—something that is true for benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and in fact all medications. He reminds us that the risks of misuse, dependence, and withdrawal associated with benzodiazepines led to a boxed warning in September 2020 and highlights recent trends of fatal and nonfatal benzodiazepine overdose, especially when combined with opiates.

Our article, which aimed to educate clinicians on benzodiazepine pharmacology and patient-specific factors influencing benzodiazepine selection and dosing, did not focus significantly on the risks associated with benzodiazepines. We do encourage careful and individualized benzodiazepine prescribing. However, we wish to remind our colleagues that benzodiazepines, while associated with risks, continue to have utility in acute and periprocedural settings, and remain an important treatment option for patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (especially while waiting for other medications to take effect), catatonia, seizure disorders, and alcohol withdrawal.

We agree that patient-specific risk assessment is essential, as some patients benefit from benzodiazepines despite the risks. However, we also acknowledge that some individuals are at higher risk for adverse outcomes, including those with concurrent opiate use or who are prescribed other sedative-hypnotics; older adults and those with neurocognitive disorders; and patients susceptible to respiratory depression due to other medical reasons (eg, myasthenia gravis, sleep apnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Further, we agree that benzodiazepine use during pregnancy is generally not advised due to the risks of neonatal hypotonia and neonatal withdrawal syndrome1 as well as a possible risk of cleft palate that has been reported in some studies.2 Finally, paradoxical reactions may be more common at the extremes of age and in patients with intellectual disability or personality disorders.3,4

Patient characteristics that have been associated with a higher risk of benzodiazepine use disorder include lower education/income, unemployment, having another substance use disorder, and severe psychopathology.5 In some studies, using benzodiazepines for prolonged periods at high doses as well as using those with a rapid onset of action was associated with an increased risk of benzodiazepine use disorder.5-7

Ultimately, we concur with Dr. Sanders on the perils of the “irresponsible use” of medication and emphasize the need for discernment when choosing treatments to avoid rashly discarding an effective remedy while attempting to mitigate all conceivable risks.

Julia Stimpfl, MD

Jeffrey R. Strawn, MD

Cincinnati, Ohio

References

1. McElhatton PR. The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation. Reprod Toxicol. 1994;8(6):461-475. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9

2. Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(1):46-48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7 Erratum in: J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(4):319.

3. Hakimi Y, Petitpain N, Pinzani V, et al. Paradoxical adverse drug reactions: descriptive analysis of French reports. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(8):1169-1174. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-02892-2

4. Paton C. Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2002;26(12):460-462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460

5. Fride Tvete I, Bjørner T, Skomedal T. Risk factors for excessive benzodiazepine use in a working age population: a nationwide 5-year survey in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):252-259. doi:10.3109/02813432.2015.1117282

6. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 9:31-41.

7. Kan CC, Hilberink SR, Breteler MH. Determination of the main risk factors for benzodiazepine dependence using a multivariate and multidimensional approach. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):88-94. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.12.007

Continue to: Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Dr. Sanders’ letter highlights the potential caveats associated with prescribing controlled substances. We agree that our short case summary includes numerous interesting elements, each of which would be worthy of further exploration and discussion. Our choice was to highlight the patient history of bariatric surgery and use this as a springboard into a review of stimulants, including the newest formulations for ADHD. For more than 1 year, many generic stimulants have been in short supply, and patients and clinicians have been seeking other therapeutic options. Given this background and with newer, branded stimulant use becoming more commonplace, we believe our article was useful and timely.

Our original intent had been to include an example of a controlled substance agreement. Regrettably, there was simply not enough space for this document or the additional discussion that its inclusion would deem necessary. Nevertheless, had the May 2023 FDA requirement for manufacturers to update the labeling of prescription stimulants1 to clarify misuse and abuse been published before our article’s final revision, we would have mentioned it and provided the appropriate link.

Subbu J. Sarma, MD, FAPA

Kansas City, Missouri

Sarah E. Grady, PharmD, BCPS, BCPP

Des Moines, Iowa

References

1. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requires updates to clarify labeling of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-updates-clarify-labeling-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

I was disheartened with the June 2023 issue of

The benzodiazepine pharmacology discussed in this article is interesting, but it would be helpful if it had been integrated within a much more extensive discussion of careful prescribing practices. In 2020, the FDA updated the boxed warning to alert prescribers to the serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with benzodiazepines.2 I would hope that an article on benzodiazepines would provide more discussion and guidance surrounding these important issues.

The June 2023 issue also included “High-dose stimulants for adult ADHD” (p. 34-39, doi:10.12788/cp.0366). This article provided esoteric advice on managing stimulant therapy in the setting of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, yet I would regard stimulant misuse as a far more common and pressing issue.3,4 The recent Drug Enforcement Administration investigation of telehealth stimulant prescribing is a notable example of this problem.5

The patient discussed in this article was receiving large doses of stimulants for a purported case of refractory attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The article provided a sparse differential diagnosis for the patient’s intractable symptoms. While rapid metabolism may be an explanation, I would also like to know how the authors ruled out physiological dependence and/or addiction to a controlled substance. How was misuse excluded? Was urine drug testing (UDS) performed? UDS is highly irregular among prescribers,6 which suggests that practices for detecting covert substance abuse and stimulant misuse are inadequate. Wouldn’t such investigations be fundamental to ethical stimulant prescribing?

Jeff Sanders, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines—38 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7034a2.htm

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requiring boxed warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class

3. McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Wilens TE, et al. Prescription stimulant medical and nonmedical use among US secondary school students, 2005 to 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e238707. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.8707

4. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA updating warnings to improve safe use of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fda-updating-warnings-improve-safe-use-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

5. Vaidya A. Report: telehealth company’s prescribing practices come under DEA scrutiny. September 16, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/report-telehealth-company-dones-prescribing-practices-come-under-dea-scrutiny

6. Zionts A. Some ADHD patients are drug-tested often, while others are never asked. Kaiser Health News. March 25, 2023. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna76330

Continue to: Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

We thank Dr. Sanders for highlighting the need for clinical equipoise in considering the risks and benefits of medications—something that is true for benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and in fact all medications. He reminds us that the risks of misuse, dependence, and withdrawal associated with benzodiazepines led to a boxed warning in September 2020 and highlights recent trends of fatal and nonfatal benzodiazepine overdose, especially when combined with opiates.

Our article, which aimed to educate clinicians on benzodiazepine pharmacology and patient-specific factors influencing benzodiazepine selection and dosing, did not focus significantly on the risks associated with benzodiazepines. We do encourage careful and individualized benzodiazepine prescribing. However, we wish to remind our colleagues that benzodiazepines, while associated with risks, continue to have utility in acute and periprocedural settings, and remain an important treatment option for patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (especially while waiting for other medications to take effect), catatonia, seizure disorders, and alcohol withdrawal.

We agree that patient-specific risk assessment is essential, as some patients benefit from benzodiazepines despite the risks. However, we also acknowledge that some individuals are at higher risk for adverse outcomes, including those with concurrent opiate use or who are prescribed other sedative-hypnotics; older adults and those with neurocognitive disorders; and patients susceptible to respiratory depression due to other medical reasons (eg, myasthenia gravis, sleep apnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Further, we agree that benzodiazepine use during pregnancy is generally not advised due to the risks of neonatal hypotonia and neonatal withdrawal syndrome1 as well as a possible risk of cleft palate that has been reported in some studies.2 Finally, paradoxical reactions may be more common at the extremes of age and in patients with intellectual disability or personality disorders.3,4

Patient characteristics that have been associated with a higher risk of benzodiazepine use disorder include lower education/income, unemployment, having another substance use disorder, and severe psychopathology.5 In some studies, using benzodiazepines for prolonged periods at high doses as well as using those with a rapid onset of action was associated with an increased risk of benzodiazepine use disorder.5-7

Ultimately, we concur with Dr. Sanders on the perils of the “irresponsible use” of medication and emphasize the need for discernment when choosing treatments to avoid rashly discarding an effective remedy while attempting to mitigate all conceivable risks.

Julia Stimpfl, MD

Jeffrey R. Strawn, MD

Cincinnati, Ohio

References

1. McElhatton PR. The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation. Reprod Toxicol. 1994;8(6):461-475. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9

2. Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(1):46-48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7 Erratum in: J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(4):319.

3. Hakimi Y, Petitpain N, Pinzani V, et al. Paradoxical adverse drug reactions: descriptive analysis of French reports. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(8):1169-1174. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-02892-2

4. Paton C. Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2002;26(12):460-462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460

5. Fride Tvete I, Bjørner T, Skomedal T. Risk factors for excessive benzodiazepine use in a working age population: a nationwide 5-year survey in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):252-259. doi:10.3109/02813432.2015.1117282

6. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 9:31-41.

7. Kan CC, Hilberink SR, Breteler MH. Determination of the main risk factors for benzodiazepine dependence using a multivariate and multidimensional approach. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):88-94. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.12.007

Continue to: Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Dr. Sanders’ letter highlights the potential caveats associated with prescribing controlled substances. We agree that our short case summary includes numerous interesting elements, each of which would be worthy of further exploration and discussion. Our choice was to highlight the patient history of bariatric surgery and use this as a springboard into a review of stimulants, including the newest formulations for ADHD. For more than 1 year, many generic stimulants have been in short supply, and patients and clinicians have been seeking other therapeutic options. Given this background and with newer, branded stimulant use becoming more commonplace, we believe our article was useful and timely.

Our original intent had been to include an example of a controlled substance agreement. Regrettably, there was simply not enough space for this document or the additional discussion that its inclusion would deem necessary. Nevertheless, had the May 2023 FDA requirement for manufacturers to update the labeling of prescription stimulants1 to clarify misuse and abuse been published before our article’s final revision, we would have mentioned it and provided the appropriate link.

Subbu J. Sarma, MD, FAPA

Kansas City, Missouri

Sarah E. Grady, PharmD, BCPS, BCPP

Des Moines, Iowa

References

1. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requires updates to clarify labeling of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-updates-clarify-labeling-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

I was disheartened with the June 2023 issue of

The benzodiazepine pharmacology discussed in this article is interesting, but it would be helpful if it had been integrated within a much more extensive discussion of careful prescribing practices. In 2020, the FDA updated the boxed warning to alert prescribers to the serious risks of abuse, addiction, physical dependence, and withdrawal reactions associated with benzodiazepines.2 I would hope that an article on benzodiazepines would provide more discussion and guidance surrounding these important issues.

The June 2023 issue also included “High-dose stimulants for adult ADHD” (p. 34-39, doi:10.12788/cp.0366). This article provided esoteric advice on managing stimulant therapy in the setting of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery, yet I would regard stimulant misuse as a far more common and pressing issue.3,4 The recent Drug Enforcement Administration investigation of telehealth stimulant prescribing is a notable example of this problem.5

The patient discussed in this article was receiving large doses of stimulants for a purported case of refractory attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The article provided a sparse differential diagnosis for the patient’s intractable symptoms. While rapid metabolism may be an explanation, I would also like to know how the authors ruled out physiological dependence and/or addiction to a controlled substance. How was misuse excluded? Was urine drug testing (UDS) performed? UDS is highly irregular among prescribers,6 which suggests that practices for detecting covert substance abuse and stimulant misuse are inadequate. Wouldn’t such investigations be fundamental to ethical stimulant prescribing?

Jeff Sanders, MD, PhD

Atlanta, Georgia

References

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in nonfatal and fatal overdoses involving benzodiazepines—38 states and the District of Columbia, 2019-2020. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7034a2.htm

2. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requiring boxed warning updated to improve safe use of benzodiazepine drug class. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requiring-boxed-warning-updated-improve-safe-use-benzodiazepine-drug-class

3. McCabe SE, Schulenberg JE, Wilens TE, et al. Prescription stimulant medical and nonmedical use among US secondary school students, 2005 to 2020. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e238707. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.8707

4. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA updating warnings to improve safe use of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/fda-updating-warnings-improve-safe-use-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

5. Vaidya A. Report: telehealth company’s prescribing practices come under DEA scrutiny. September 16, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://mhealthintelligence.com/news/report-telehealth-company-dones-prescribing-practices-come-under-dea-scrutiny

6. Zionts A. Some ADHD patients are drug-tested often, while others are never asked. Kaiser Health News. March 25, 2023. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/rcna76330

Continue to: Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

Drs. Stimpfl and Strawn respond

We thank Dr. Sanders for highlighting the need for clinical equipoise in considering the risks and benefits of medications—something that is true for benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and in fact all medications. He reminds us that the risks of misuse, dependence, and withdrawal associated with benzodiazepines led to a boxed warning in September 2020 and highlights recent trends of fatal and nonfatal benzodiazepine overdose, especially when combined with opiates.

Our article, which aimed to educate clinicians on benzodiazepine pharmacology and patient-specific factors influencing benzodiazepine selection and dosing, did not focus significantly on the risks associated with benzodiazepines. We do encourage careful and individualized benzodiazepine prescribing. However, we wish to remind our colleagues that benzodiazepines, while associated with risks, continue to have utility in acute and periprocedural settings, and remain an important treatment option for patients with panic disorder, generalized anxiety disorder (especially while waiting for other medications to take effect), catatonia, seizure disorders, and alcohol withdrawal.

We agree that patient-specific risk assessment is essential, as some patients benefit from benzodiazepines despite the risks. However, we also acknowledge that some individuals are at higher risk for adverse outcomes, including those with concurrent opiate use or who are prescribed other sedative-hypnotics; older adults and those with neurocognitive disorders; and patients susceptible to respiratory depression due to other medical reasons (eg, myasthenia gravis, sleep apnea, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). Further, we agree that benzodiazepine use during pregnancy is generally not advised due to the risks of neonatal hypotonia and neonatal withdrawal syndrome1 as well as a possible risk of cleft palate that has been reported in some studies.2 Finally, paradoxical reactions may be more common at the extremes of age and in patients with intellectual disability or personality disorders.3,4

Patient characteristics that have been associated with a higher risk of benzodiazepine use disorder include lower education/income, unemployment, having another substance use disorder, and severe psychopathology.5 In some studies, using benzodiazepines for prolonged periods at high doses as well as using those with a rapid onset of action was associated with an increased risk of benzodiazepine use disorder.5-7

Ultimately, we concur with Dr. Sanders on the perils of the “irresponsible use” of medication and emphasize the need for discernment when choosing treatments to avoid rashly discarding an effective remedy while attempting to mitigate all conceivable risks.

Julia Stimpfl, MD

Jeffrey R. Strawn, MD

Cincinnati, Ohio

References

1. McElhatton PR. The effects of benzodiazepine use during pregnancy and lactation. Reprod Toxicol. 1994;8(6):461-475. doi:10.1016/0890-6238(94)90029-9

2. Enato E, Moretti M, Koren G. The fetal safety of benzodiazepines: an updated meta-analysis. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(1):46-48. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)34772-7 Erratum in: J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2011;33(4):319.

3. Hakimi Y, Petitpain N, Pinzani V, et al. Paradoxical adverse drug reactions: descriptive analysis of French reports. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76(8):1169-1174. doi:10.1007/s00228-020-02892-2

4. Paton C. Benzodiazepines and disinhibition: a review. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2002;26(12):460-462. doi:10.1192/pb.26.12.460

5. Fride Tvete I, Bjørner T, Skomedal T. Risk factors for excessive benzodiazepine use in a working age population: a nationwide 5-year survey in Norway. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(4):252-259. doi:10.3109/02813432.2015.1117282

6. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW. Relative abuse liability of hypnotic drugs: a conceptual framework and algorithm for differentiating among compounds. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66 Suppl 9:31-41.

7. Kan CC, Hilberink SR, Breteler MH. Determination of the main risk factors for benzodiazepine dependence using a multivariate and multidimensional approach. Compr Psychiatry. 2004;45(2):88-94. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2003.12.007

Continue to: Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Drs. Sarma and Grady respond

Dr. Sanders’ letter highlights the potential caveats associated with prescribing controlled substances. We agree that our short case summary includes numerous interesting elements, each of which would be worthy of further exploration and discussion. Our choice was to highlight the patient history of bariatric surgery and use this as a springboard into a review of stimulants, including the newest formulations for ADHD. For more than 1 year, many generic stimulants have been in short supply, and patients and clinicians have been seeking other therapeutic options. Given this background and with newer, branded stimulant use becoming more commonplace, we believe our article was useful and timely.

Our original intent had been to include an example of a controlled substance agreement. Regrettably, there was simply not enough space for this document or the additional discussion that its inclusion would deem necessary. Nevertheless, had the May 2023 FDA requirement for manufacturers to update the labeling of prescription stimulants1 to clarify misuse and abuse been published before our article’s final revision, we would have mentioned it and provided the appropriate link.

Subbu J. Sarma, MD, FAPA

Kansas City, Missouri

Sarah E. Grady, PharmD, BCPS, BCPP

Des Moines, Iowa

References

1. US Food & Drug Administration. FDA requires updates to clarify labeling of prescription stimulants used to treat ADHD and other conditions. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-requires-updates-clarify-labeling-prescription-stimulants-used-treat-adhd-and-other-conditions

High-dose stimulants for adult ADHD

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

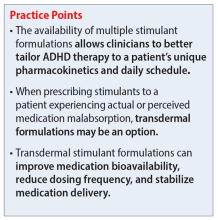

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

Ms. H, age 30, presents to the outpatient clinic for a follow-up visit, where she reports difficulty paying attention to conversations, starting and completing tasks, and meeting deadlines. These challenges occur at work and home. Her psychiatric history includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), major depressive disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder. Approximately 10 years ago, she underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery. Following surgery, Ms. H’s care team prescribed liquid formulations of medications whenever possible to minimize malabsorption. Ms. H may be a rapid metabolizer; she says the effects of her prescribed stimulants only last briefly, so she has to frequently redose. As a result, she often runs out of her monthly stimulant allotment earlier than expected.

Ms. H’s current medications include dextroamphetamine/amphetamine immediate-release (IR) 30 mg 3 times daily, atenolol 50 mg/d, and escitalopram oral solution 10 mg/d. Previous unsuccessful medication trials for her ADHD include methylphenidate IR 20 mg 3 times daily and lisdexamfetamine 70 mg/d. Ms. H reports that when her responsibilities increased at work or home, she took methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily to relieve her symptoms.

In the United States, ADHD affects an estimated 4.4% of adults age 18 to 44.1 The actual rate may be higher, however, as recent research has called into question the hypothesis that approximately 50% of cases of childhood ADHD remit by adulthood.2 Prevalence estimates relying on DSM-IV criteria (which were designed with children in mind) can underestimate this condition in adults. Newer data suggest that up to 90% of individuals with ADHD in childhood continue to experience significant ADHD symptoms into adulthood.2

Unless contraindications are present, methylphenidate or amphetamine-based stimulants are the medications of choice for treating adult ADHD.3 Many formulations of both medications are available,4 which allows clinicians to better tailor therapy to each patient’s pharmacokinetics and daily schedule. Although there can be differences in response and tolerability, methylphenidate and amphetamine offer comparable efficacy and a similar adverse effect profile.5

Because amphetamine is more potent than methylphenidate, clinicians commonly start treatment with an amphetamine dose that is one-half to two-thirds the dose of methylphenidate.6 While both classes of stimulants inhibit the reuptake of dopamine and norepinephrine into presynaptic neurons, amphetamines also promote the release of dopamine and norepinephrine from their storage sites in presynaptic nerve terminals.3

Methylphenidate

Methylphenidate IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 3 to 4 hours. The extended-release (XR) formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 12 hours (Table 13,7).4 The XR products usually immediately release a certain percentage of the medication, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. One methylphenidate XR product (Jornay) as well as serdexmethylphenidate/dexmethylphenidate (Azstarys) offer durations of action of 24 to 36 hours. Methylphenidate is primarily metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 (CES1) to the inactive metabolite ritalinic acid. Most of the medication (60% to 80%) is excreted in the urine as ritalinic acid.4 Theoretically, genetic variations in the CES1 and concomitant use of medications that compete with or alter this pathway may impact methylphenidate pharmacokinetics.8 However, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.4

Amphetamine

Dextroamphetamine/amphetamine IR has an average onset of action of 30 to 45 minutes and its effects last approximately 4 to 6 hours. XR formulations have varying onsets of action, with durations of action up to 13 hours (Table 23,7,9).4 One XR product, mixed salts of single amphetamine entity (Mydayis), has a duration of action of 16 hours. In XR formulations, a certain percentage of the medication is typically released immediately, eliminating the need for an additional IR tablet. Amphetamine is primarily metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2D6 hydroxylation and oxidative deamination. Genetic variability in amphetamine metabolism may be relevant due to CYP2D6 polymorphisms. Ultra-rapid metabolizers might need higher doses, while poor metabolizers might require smaller amounts and may be more susceptible to adverse effects.4 However, there is currently insufficient data supporting gene/medication concentration relationships. As is the case with methylphenidate, plasma levels have not yet shown to be helpful in guiding treatment selection or dosing.6

Continue to: Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Impaired medication absorption after bariatric surgery

Medication malabsorption following bariatric surgery is a significant concern. In a systematic review of 22 studies, Padwal et al10 found that in one-third of these studies, decreased absorption following bariatric surgery may be present in patients taking medications that have poor absorption, high lipophilicity, or enterohepatic recirculation. Childress et al11 found that methylphenidate IR and dextroamphetamine/amphetamine are both well absorbed, with bioavailability percentages of 100% and 90%, respectively. Additional research shows both stimulants have rapid absorption rates but relatively poor bioavailability.12 In one study analyzing the dissolution of common psychiatric medications, methylphenidate was shown to dissolve slightly more in the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery model (80 mg) compared to controls (70 mg).13 One case indicated potential methylphenidate toxicity following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery,14 while another suggested impaired absorption following the same procedure.15 A case-control design study assessing the impact of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery on the pharmacokinetic properties of lisdexamfetamine found no significant differences between the Roux-en-Y group (n = 10) and nonsurgical controls (n = 10). The investigators concluded that while data suggest adjusting lisdexamfetamine dosing following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery is unnecessary, there may be interindividual differences, and individualized dosing regimens may be needed.16

When managing patients who might be experiencing medication malabsorption, it may be helpful to use dosage forms that avoid disintegration, acidic environments, and slow dissolution. Because they are more rapidly absorbed and not susceptible to disintegration and dissolution, liquid formulations are recommended.17 For medications that are not available as a liquid, an IR formulation is recommended.18

Using nonoral routes of administration that avoid the anatomical changes of the gastrointestinal tract should be considered for patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery.17 The methylphenidate transdermal patch, a medication delivery system that avoids gut and hepatic first-pass metabolism, can improve medication bioavailability, reduce dose frequency, and stabilize medication delivery. It is available in 4 sizes/dosages: 10 mg/9 hours, 15 mg/9 hours, 20 mg/9 hours, and 30 mg/9 hours. Methylphenidate is delivered at a steady rate based upon patch size. The onset of action of the patch is approximately 2 hours, and patients should wear the patch for 9 hours, then remove it. Methylphenidate will still be absorbed up to 2 to 3 hours after patch removal. Appropriate application and removal of the patch is important for optimal effectiveness and to avoid adverse effects.4

In March 2022, t

CASE CONTINUED

Ms. H emphasizes her desire to maintain functionality in all areas of life, while her care team reiterates the risks of continuing to take high-dose stimulants. Both Ms. H and her care team acknowledge that stimulant usage could be worsening her anxiety, and that Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery may be a possible explanation for her dosing challenges.

Continue to: Following consultation with the pharmacist...

Following consultation with the pharmacist, the care team explains the possible pharmacokinetic benefits of using the methylphenidate transdermal patch. After completing the prior authorization paperwork, Ms. H is started on the 30 mg/d patch. This dose was selected because she previously tolerated high-dose stimulants, including methylphenidate IR 20 mg up to 6 times daily. At a follow-up visit 1 month after starting the patch, Ms. H reports an improvement in her ADHD symptoms and says she is not experiencing any adverse effects.

Related Resources

- DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

- Santos MG, Majarwitz DJ, Saeed SA. Adult ADHD: 6 studies of pharmacologic interventions. Current Psychiatry. 2023;22(4):16-27. doi:10.12788/cp.0344

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine sulfate • Adzenys ER, Adzenys XR-ODT, Dyanavel XR, Evekeo

Atenolol • Tenormin

Dexmethylphenidate • Focalin, Focalin XR

Dextroamphetamine transdermal • Xelstrym

Dextroamphetamine • Dexedrine, Dexedrine Spansule, ProCentra, Zenzedi

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Methylphenidate • Aptensio XR, Adhansia XR, Concerta, Cotempla, Jornay PM, Metadate CD, Metadate ER, Methylin, Qullichew ER, Quillivant XR, Relexxii, Ritalin, Ritalin LA

Methylphenidate transdermal • Daytrana

Mixed amphetamine salts • Adderall, Adderall XR

Mixed salts of a single-entity amphetamine • Mydayis

Serdexmethylphenidate and dexmethylphenidate • Azstarys

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271

1. Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(4):716-723. doi:10.1176/ajp.2006.163.4.716

2. Sibley MH, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. Variable patterns of remission from ADHD in the multimodal treatment study of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry. 2022;179(2):142-151. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2021.21010032

3. Cleveland KW, Boyle J, Robinson RF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. In: Chisholm-Burns MA, Schwinghammer TL, Malone PM, et al, eds. Pharmacotherapy Principles & Practice. 6th ed. McGraw Hill; 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://ppp.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=3114§ionid=261474885

4. Steingard R, Taskiran S, Connor DF, et al. New formulations of stimulants: an update for clinicians. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2019;29(5):324-339. doi:10.1089/cap.2019.0043

5. Faraone SV. The pharmacology of amphetamine and methylphenidate: relevance to the neurobiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and other psychiatric comorbidities. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2018;87:255-270. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2018.02.001

6. Markowitz JS, Patrick KS. The clinical pharmacokinetics of amphetamines utilized in the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2017;27(8):678-689. doi:10.1089/cap.2017.0071

7. Mullen S. Medication Table 2: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. In: English C, ed. CPNP Psychiatric Pharmacotherapy Review Course. 2022-2023 ed. College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists; 2022.

8. Zhu HJ, Patrick KS, Yuan HJ, et al. Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82(6):1241-1248. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015

9. Xelstrym [package insert]. Miami, FL: Noven Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2022.

10. Padwal R, Brocks D, Sharma AM. A systematic review of drug absorption following bariatric surgery and its theoretical implications. Obes Rev. 2010;11(1):41-50. doi:10.1111/j.1467-789X.2009.00614.x

11. Childress AC, Komolova M, Sallee FR. An update on the pharmacokinetic considerations in the treatment of ADHD with long-acting methylphenidate and amphetamine formulations. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2019;15(11):937-974. doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1675636

12. Markowitz JS, Melchert PW. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacogenomics of psychostimulants. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2022;31(3):393-416. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2022.03.003

13. Seaman JS, Bowers SP, Dixon P, et al. Dissolution of common psychiatric medications in a Roux-en-Y gastric bypass model. Psychosomatics. 2005;46(3):250-253. doi:10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.250

14. Ludvigsson M, Haenni A. Methylphenidate toxicity after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(5):e55-e57. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.015

15. Azran C, Langguth P, Dahan A. Impaired oral absorption of methylphenidate after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(7):1245-1247. doi:10.1016/j.soard.2017.03.003

16. Steffen KJ, Mohammad AS, Roerig JL, et al. Lisdexamfetamine pharmacokinetic comparison between patients who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and nonsurgical controls. Obes Surg. 2021;31(10):4289-4294. doi:10.1007/s11695-020-04969-4

17. Buxton ILO. Pharmacokinetics: the dynamics of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and elimination. In: Brunton LL, Knollmann BC, eds. Goodman & Gilman’s: The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 14th ed. McGraw Hill; 2023. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://accesspharmacy.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2189§ionid=166182905

18. DeMarco R, Rana R, Powell K, et al. How bariatric surgery affects psychotropic drug absorption. Current Psychiatry. 2022;21(8):39-44. doi:10.12788/cp.0271