User login

‘Non-criteria’ antiphospholipid antibodies and thrombosis

To the Editor: We read with great interest the excellent article on thrombosis secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.1 We wish to comment on the section “Antiphospholipid antibodies are not all the same,” specifically on question 6: “Which of the following antiphospholipid antibodies have not been associated with an increased thrombotic risk?”

The answer offered was antiphosphatidylserine, and the authors stated, “While lupus anticoagulant, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I, and anticardiolipin antibodies are associated with thrombosis, antiprothrombin antibodies (including antiprothrombin and antiphosphatidylserine antibodies) are not.”1

Antiphospholipid antibody testing in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is complicated, but we feel the information provided was inaccurate. It should be noted that 3 antibodies are under discussion: in addition to antiphosphatidylserine (aPS) antibodies, antiprothrombin antibodies are heterogeneous, comprising antibodies to prothrombin alone (aPT-A) and antibodies to the antiphosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex (aPS/PT). While the diagnostic utility of these antibodies is in evolution, there are numerous studies on their association with thrombosis or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or both.2,3 Most recently, a systematic review (N = 7,000) concluded that prothrombin antibodies (aPT, aPS/PT) were strong risk factors for thrombosis (odds ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.72–3.5).4

The revised Sapporo (Sydney) guidelines referenced by the authors addressed these “non-criteria” antiphospholipid antibodies.5 At that time (2006), it was thought premature to include these antibodies as independent criteria for definite antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, even though their association with the syndrome was recognized by the committee. The guidelines considered an interesting scenario: What if a case fulfills the clinical criteria of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, but serology is positive only for these “non-criteria” antibodies? It was suggested that these cases be classified as “probable” antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Also, aPS/PT was proposed as a confirmatory assay for lupus anticoagulant testing.

In 2010, the International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies concluded that aPS/PT is truly relevant to thrombosis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, with the possibility of aPS/PT becoming a criterion for the syndrome in the future.6 Studies have already started on this.7 Since then, 2 scoring systems to quantify the risk of thrombosis and obstetric events have incorporated aPS/PT—the Antiphospholipid Score (2012) and the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score (2013).8.9

In conclusion, these antibodies are associated with thrombosis, can be considered features of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome in the right clinical context, and have a role in contemporary discussion of this disease.

- Serhal M, Evans N, Gornik HL. A 75-year-old with abdominal pain, hypoxia, and weak pulses in the left leg. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(2):145–154. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.16069

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, Al Shehri T, Khojah O, Owaidah T. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2015; 24(2):186–190. doi:10.1177/0961203314552462

- Sciascia S, Bertolaccini ML. Antibodies to phosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex and the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2014; 23(12):1309–1312. doi:10.1177/0961203314538332

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. Anti-prothrombin (aPT) and anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin (aPS/PT) antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2014; 111(2):354–364. doi:10.1160/TH13-06-0509

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4(2):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. ‘Non-criteria’ aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus 2011; 20:191–205. doi:10.1177/0961203310397082

- Fabris M, Giacomello R, Poz A, et al. The introduction of anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin autoantibodies in the laboratory diagnostic process of anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome: 6 months of observation. Auto-Immunity Highlights 2014; 5(2):63–67. doi:10.1007/s13317-014-0061-3

- Otomo K, Atsumi T, Amengual O, et al. Efficacy of the antiphospholipid score for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome and its predictive value for thrombotic events. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(2):504–512. doi:10.1002/art.33340

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. GAPSS: the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013; 52(8):1397–1403. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kes388

To the Editor: We read with great interest the excellent article on thrombosis secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.1 We wish to comment on the section “Antiphospholipid antibodies are not all the same,” specifically on question 6: “Which of the following antiphospholipid antibodies have not been associated with an increased thrombotic risk?”

The answer offered was antiphosphatidylserine, and the authors stated, “While lupus anticoagulant, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I, and anticardiolipin antibodies are associated with thrombosis, antiprothrombin antibodies (including antiprothrombin and antiphosphatidylserine antibodies) are not.”1

Antiphospholipid antibody testing in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is complicated, but we feel the information provided was inaccurate. It should be noted that 3 antibodies are under discussion: in addition to antiphosphatidylserine (aPS) antibodies, antiprothrombin antibodies are heterogeneous, comprising antibodies to prothrombin alone (aPT-A) and antibodies to the antiphosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex (aPS/PT). While the diagnostic utility of these antibodies is in evolution, there are numerous studies on their association with thrombosis or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or both.2,3 Most recently, a systematic review (N = 7,000) concluded that prothrombin antibodies (aPT, aPS/PT) were strong risk factors for thrombosis (odds ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.72–3.5).4

The revised Sapporo (Sydney) guidelines referenced by the authors addressed these “non-criteria” antiphospholipid antibodies.5 At that time (2006), it was thought premature to include these antibodies as independent criteria for definite antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, even though their association with the syndrome was recognized by the committee. The guidelines considered an interesting scenario: What if a case fulfills the clinical criteria of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, but serology is positive only for these “non-criteria” antibodies? It was suggested that these cases be classified as “probable” antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Also, aPS/PT was proposed as a confirmatory assay for lupus anticoagulant testing.

In 2010, the International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies concluded that aPS/PT is truly relevant to thrombosis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, with the possibility of aPS/PT becoming a criterion for the syndrome in the future.6 Studies have already started on this.7 Since then, 2 scoring systems to quantify the risk of thrombosis and obstetric events have incorporated aPS/PT—the Antiphospholipid Score (2012) and the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score (2013).8.9

In conclusion, these antibodies are associated with thrombosis, can be considered features of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome in the right clinical context, and have a role in contemporary discussion of this disease.

To the Editor: We read with great interest the excellent article on thrombosis secondary to antiphospholipid antibody syndrome.1 We wish to comment on the section “Antiphospholipid antibodies are not all the same,” specifically on question 6: “Which of the following antiphospholipid antibodies have not been associated with an increased thrombotic risk?”

The answer offered was antiphosphatidylserine, and the authors stated, “While lupus anticoagulant, anti-beta-2-glycoprotein I, and anticardiolipin antibodies are associated with thrombosis, antiprothrombin antibodies (including antiprothrombin and antiphosphatidylserine antibodies) are not.”1

Antiphospholipid antibody testing in antiphospholipid antibody syndrome is complicated, but we feel the information provided was inaccurate. It should be noted that 3 antibodies are under discussion: in addition to antiphosphatidylserine (aPS) antibodies, antiprothrombin antibodies are heterogeneous, comprising antibodies to prothrombin alone (aPT-A) and antibodies to the antiphosphatidylserine-prothrombin complex (aPS/PT). While the diagnostic utility of these antibodies is in evolution, there are numerous studies on their association with thrombosis or antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, or both.2,3 Most recently, a systematic review (N = 7,000) concluded that prothrombin antibodies (aPT, aPS/PT) were strong risk factors for thrombosis (odds ratio 2.3, 95% confidence interval 1.72–3.5).4

The revised Sapporo (Sydney) guidelines referenced by the authors addressed these “non-criteria” antiphospholipid antibodies.5 At that time (2006), it was thought premature to include these antibodies as independent criteria for definite antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, even though their association with the syndrome was recognized by the committee. The guidelines considered an interesting scenario: What if a case fulfills the clinical criteria of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, but serology is positive only for these “non-criteria” antibodies? It was suggested that these cases be classified as “probable” antiphospholipid antibody syndrome. Also, aPS/PT was proposed as a confirmatory assay for lupus anticoagulant testing.

In 2010, the International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies concluded that aPS/PT is truly relevant to thrombosis and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, with the possibility of aPS/PT becoming a criterion for the syndrome in the future.6 Studies have already started on this.7 Since then, 2 scoring systems to quantify the risk of thrombosis and obstetric events have incorporated aPS/PT—the Antiphospholipid Score (2012) and the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score (2013).8.9

In conclusion, these antibodies are associated with thrombosis, can be considered features of antiphospholipid antibody syndrome in the right clinical context, and have a role in contemporary discussion of this disease.

- Serhal M, Evans N, Gornik HL. A 75-year-old with abdominal pain, hypoxia, and weak pulses in the left leg. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(2):145–154. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.16069

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, Al Shehri T, Khojah O, Owaidah T. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2015; 24(2):186–190. doi:10.1177/0961203314552462

- Sciascia S, Bertolaccini ML. Antibodies to phosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex and the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2014; 23(12):1309–1312. doi:10.1177/0961203314538332

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. Anti-prothrombin (aPT) and anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin (aPS/PT) antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2014; 111(2):354–364. doi:10.1160/TH13-06-0509

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4(2):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. ‘Non-criteria’ aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus 2011; 20:191–205. doi:10.1177/0961203310397082

- Fabris M, Giacomello R, Poz A, et al. The introduction of anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin autoantibodies in the laboratory diagnostic process of anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome: 6 months of observation. Auto-Immunity Highlights 2014; 5(2):63–67. doi:10.1007/s13317-014-0061-3

- Otomo K, Atsumi T, Amengual O, et al. Efficacy of the antiphospholipid score for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome and its predictive value for thrombotic events. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(2):504–512. doi:10.1002/art.33340

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. GAPSS: the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013; 52(8):1397–1403. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kes388

- Serhal M, Evans N, Gornik HL. A 75-year-old with abdominal pain, hypoxia, and weak pulses in the left leg. Cleve Clin J Med 2018; 85(2):145–154. doi:10.3949/ccjm.85a.16069

- Khogeer H, Alfattani A, Al Kaff M, Al Shehri T, Khojah O, Owaidah T. Antiphosphatidylserine antibodies as diagnostic indicators of antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2015; 24(2):186–190. doi:10.1177/0961203314552462

- Sciascia S, Bertolaccini ML. Antibodies to phosphatidylserine/prothrombin complex and the antiphospholipid syndrome. Lupus 2014; 23(12):1309–1312. doi:10.1177/0961203314538332

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. Anti-prothrombin (aPT) and anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin (aPS/PT) antibodies and the risk of thrombosis in the antiphospholipid syndrome. A systematic review. Thromb Haemost 2014; 111(2):354–364. doi:10.1160/TH13-06-0509

- Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost 2006; 4(2):295–306. doi:10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01753.x

- Bertolaccini ML, Amengual O, Atsumi T, et al. ‘Non-criteria’ aPL tests: report of a task force and preconference workshop at the 13th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies, Galveston, TX, USA, April 2010. Lupus 2011; 20:191–205. doi:10.1177/0961203310397082

- Fabris M, Giacomello R, Poz A, et al. The introduction of anti-phosphatidylserine/prothrombin autoantibodies in the laboratory diagnostic process of anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome: 6 months of observation. Auto-Immunity Highlights 2014; 5(2):63–67. doi:10.1007/s13317-014-0061-3

- Otomo K, Atsumi T, Amengual O, et al. Efficacy of the antiphospholipid score for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome and its predictive value for thrombotic events. Arthritis Rheum 2012; 64(2):504–512. doi:10.1002/art.33340

- Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. GAPSS: the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013; 52(8):1397–1403. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kes388

Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

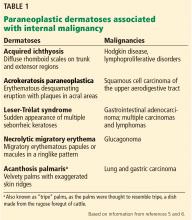

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

A 66-year-old woman presented to the emergency room with pain and bluish discoloration of her left great toe for the past 2 days. She had no history of trauma to the toe or of peripheral vascular disease. She also complained of intermittent abdominal pain for the last 5 months and unintentional weight loss of 8 pounds.

Vascular disease was suspected, and the patient was started on systemic anticoagulation. However, chest computed tomography (CT) and conventional angiography showed no aortic disease; vessels were of normal caliber, and no distal filling defects were noted.

A routine evaluation with complete blood cell count, peripheral smear, renal function testing, and urinalysis with eosinophil smear was also unrevealing. An extensive investigation followed, including serum complement testing, assays for antinuclear, antineutrophil cytoplasmic, and anti-Sjögren syndrome A and B antibodies, cryoglobulin testing, and hepatitis B and C virus serology, as well as screening for syphilis and lupus anticoagulant, anticardiolipin, and beta-2 glycoprotein antibodies. The results for all these tests were also unremarkable.

Results of coagulation testing and venous duplex ultrasonography of the legs were normal, and electrocardiography and echocardiography showed no signs of valvular vegetation, myxoma, or patent foramen ovale.

Given our patient’s age, abdominal pain, and weight loss but negative vascular evaluation, we considered a diagnosis of paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome. Abdominal CT revealed a tumor of the pancreatic head with multiple liver lesions, and cytologic study confirmed pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

DISTANT MARKERS OF MALIGNANCY

Causes of blue toe syndrome to consider in the differential diagnosis include arterial thromboembolism, vasoconstrictive drug use or disorders, vasculitis, and venous thrombosis.1 These are common and deserve prompt investigation. However, if they are ruled out, a peripheral acral vascular syndrome should be considered. These syndromes present as Raynaud phenomenon, gangrene, or acrocyanosis of the fingers or toes with underlying neoplasia. Unusual features such as sudden onset in a patient over age 50, an acral distribution, and associated symptoms such as unrelated pain and weight loss should spark concern for underlying malignancy.

Paraneoplastic syndromes are defined as signs and symptoms that present distant from the site of malignancy. Dermatoses as markers of internal malignancy are well-established but perplexing clinical entities whose exact causes remain unknown.2

Paraneoplastic dermatoses are well recognized as harbingers of metastatic disease.5,6 Our patient’s story demonstrates need for a thorough diagnostic investigation.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.

- Hirschmann JV, Raugi GJ. Blue (or purple) toe syndrome. J Am Acad Dermatol 2009; 60:1–20.

- Naschitz JE, Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Zuckerman E, Yeshurun D. Rheumatic syndromes: clues to occult neoplasia. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1999; 29:43–55.

- Poszepczynska-Guigné E, Viguier M, Chosidow O, Orcel B, Emmerich J, Dubertret L. Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome: epidemiologic features, clinical manifestations, and disease sequelae. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002; 47:47–52.

- DeCross AJ, Sahasrabudhe DM. Paraneoplastic Raynaud's phenomenon. Am J Med 1992; 92:571–572.

- Ramos-E-Silva M, Carvalho JC, Carneiro SC. Cutaneous paraneoplasia. Clin Dermatol 2011; 29:541–547.

- Chung VQ, Moschella SL, Zembowicz A, Liu V. Clinical and pathologic findings of paraneoplastic dermatoses. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006; 54:745–762.