User login

Combined Tibial Tubercle Avulsion Fracture and Patellar Avulsion Fracture: An Unusual Variant in an Adolescent Patient

Tibial tubercle fractures are rare injuries accounting for less than 1% of all pediatric physeal injuries.1 The original classification scheme for such fractures was proposed by Watson-Jones.2 Initially modified by Ogden and colleagues,3 the classification system has had numerous additions and modifications as new patterns of injury have been identified.4-6 Patellar fractures are also rare in children, making up 1% of all pediatric fractures, with less than 2% of these occurring in skeletally immature children.7

We present a case of an unreported combined tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and patellar avulsion fracture in an adolescent boy. The patient and his guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

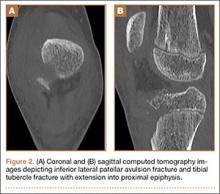

A 12-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with acute onset of right-knee pain and inability to ambulate after falling off a skateboard on the day of the injury. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no noteworthy medical or surgical history, including no prior fractures. On physical examination, he was noted to have a large right-knee effusion presumed to be hemarthrosis, and inability to perform a straight-leg raise against gravity. There were no neurologic deficits and his leg compartments were soft. Plain radiographs showed patella alta and numerous bony fragments believed to represent a complex tibial tubercle fracture. One bony fragment was identified closer to the patella, suggesting a possible concurrent patellar fracture (Figures 1A, 1B). A computed tomography (CT) scan further characterized both the tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and the lateral inferior pole patellar avulsion fracture (Figures 2A, 2B). The patient’s knee was immobilized, and he was admitted for soft-tissue rest and overnight observation to ensure that compartment syndrome did not develop.

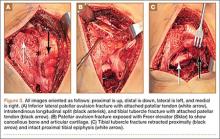

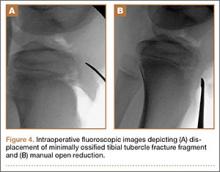

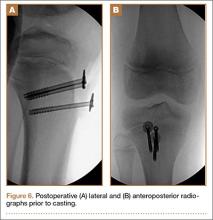

Five days after injury, open reduction and internal fixation were performed. After limb exsanguination and tourniquet insufflation, the fracture was visualized through a direct midline approach. The patient was found to have a Z-type injury pattern to the extensor mechanism: an inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture, longitudinal splits of the patellar tendon, and 2 large, mainly cartilaginous tibial tubercle fracture fragments, 1 of which extended into the proximal tibial epiphysis (Ogden type III) (Figures 3A-3C). Under direct visualization, the tibial tubercle fragments were reduced and stabilized with 3 cannulated 3.5-mm titanium, partially threaded screws with washers. Smaller screws were used to prevent fragmentation of these mostly cartilaginous fragments. Anatomic reduction was ensured along the articular surface, visualized through an arthrotomy, as well as on the distal cortex (Figures 4A, 4B). The patellar avulsion fracture included a very small section of articular surface and the decision was made to preserve the fragment. Because the patellar fragment was too small for screw fixation, the fracture was secured with suture fixation through bone tunnels over a patellar bony bridge using size 2 Phantom Fiber suture (Tornier) (Figure 5). Vicryl was used to repair the longitudinal patellar tendon split as well as the capsular and paratenon traumatic tears. Layered closure was completed and intraoperative radiographs were obtained (Figures 6A, 6B) prior to placement of a cylinder cast in full extension. Postoperatively, the patient remained overnight for observation and physical therapy evaluation. He was encouraged to bear weight in his cylinder cast as tolerated with crutches to assist with ambulation.

Postoperatively, the patient was maintained in full extension in the cylinder cast for 4 weeks. After cast removal, the patient was placed in a range-of-motion brace locked in extension for ambulation. He started physical therapy and was allowed to perform prone active-knee flexion limited to 90º, with passive extension, for an additional 4 weeks. At 8 weeks, the patient was allowed full-knee motion both active and passive, and the brace was discontinued. At his 18-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported successful return to all his normal activities, including skateboarding, with no apparent limitation in motion or weight-bearing. Examination at that time demonstrated knee range of motion from 5º in hyperextension to 135º in flexion, with his left knee having 5º in hyperextension and 145º in flexion. The patient appeared to have no gait abnormalities, and radiographs showed healed fractures. Because of a concern that continued compression across his tibial physis could lead to greater risk of growth arrest, the decision was made to remove the implants when radiographs showed healing. The patient returned to surgery at 20 weeks for implant removal. At 6 weeks after implant removal, the patient had returned to full activity with no residual pain and full-knee flexion equal to the uninvolved left knee. He was able to perform a stable single-leg squat on his affected leg, and his single-leg hop for distance was the same as his uninvolved leg. He was allowed to return to full sports activity. The patient will be followed with serial radiographs at 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months to look for premature physeal arrest. If an arrest occurs, treatment will be dictated by the extent of the arrest and the potential to cause either limb-length difference or angular deformity.

Discussion

Tibial tubercle fractures typically result from quadriceps contraction during sporting activities, predominantly in adolescent boys with open physes. Numerous modifications and additions have been made to the original classification of such fractures by Watson-Jones,2 most notably by Ogden and colleagues3 in 1980. These additions have included combined tendon avulsions and tubercle fractures as described by Frankl and coauthors,4 complete proximal tibial physeal separation now classified as type 4 by Ryu and Debenham,5 and a “Y” fracture configuration now termed type 5 by McKoy and Stanitski.6 Pandya and colleagues8 reported on 41 tibial tubercle fractures and described a new classification scheme based on the known anatomical closure pattern of the proximal tibial physis and tibial tubercle apophysis. The authors stressed the role of advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, in preoperative management of these complex high-energy fractures in adolescents, and the need for intraoperative arthroscopy or arthrotomy to ensure anatomical reduction of the articular involvement.

Tibial tubercle fractures and extensor mechanism injuries that do not fit these classification patterns have also been described. In 1979, Houghton and Ackroyd9 reported 3 cases of acute loss of extensor mechanism secondary to a traumatic patellar sleeve avulsion. In 1995, Berg10 described an ipsilateral inferior pole osteochondral patellar avulsion fracture with patellar tendon avulsion without fracture at the tubercle in a 12-year-old boy. Another variant was described in a 2002 case series of 3 adolescent boys who underwent operative fixation for tibial metaphyseal partial-sleeve avulsion injuries.11

Conclusion

We report a case of combined ipsilateral inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture and an intra-articular tibial tubercle avulsion fracture with intervening longitudinal patellar tendon split. Preoperative standard radiographs were confusing, given the bony fragment high up by the patella, but use of advanced imaging, in this case CT, allowed us to fully characterize the origin of fracture fragments and realize we were dealing with a unique fracture pattern previously unreported in a pediatric patient. The CT findings allowed us to be better prepared preoperatively by having options for fixation of the patellar fracture, and the extent of articular involvement led us to decide that intra-articular evaluation would be required. Through the use of an open arthrotomy, anatomical articular reduction could be visualized and stabilized with screw fixation of the large, mostly cartilaginous tubercle fracture. Following the principles described by Pandya and colleagues,8 anatomical reduction was achieved, and, 6 months after the original surgery, the patient had return of full motion, clinical and radiographic union, and no clinical pain or limp, with no retained metallic implants across the tibial apophysis. Longer-term follow-up as planned will demonstrate any growth abnormality that would require further surgical intervention.

1. Mosier SM, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(2):181-184.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1955.

3. Ogden JA, Tross RB, Murphy MJ. Fractures of the tibial tuberosity in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(2):205-215.

4. Frankl U, Wasilewski SA, Healy WL. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(9):1411-1413.

5. Ryu RK, Debenham JO. An unusual avulsion fracture of the proximal tibial epiphysis. Case report and proposed addition to the Watson-Jones classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;(194):181-184.

6. McKoy BE, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(3):397-403.

7. Hunt DM, Somashekar N. A review of sleeve fractures of the patella in children. Knee. 2005;12:3-7.

8. Pandya NK, Edmonds EW, Roocroft JH, Mubarak SJ. Tibial tubercle fractures: complications, classification, and the need for intra-articular assessment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(8):749-759.

9. Houghton GR, Ackroyd CE. Sleeve fractures of the patella in children: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61(2):165-168.

10. Berg EE. Bipolar infrapatellar tendon rupture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(3):302-303.

11. Davidson D, Letts M. Partial sleeve fractures of the tibia in children: an unusual fracture pattern. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):36-40.

Tibial tubercle fractures are rare injuries accounting for less than 1% of all pediatric physeal injuries.1 The original classification scheme for such fractures was proposed by Watson-Jones.2 Initially modified by Ogden and colleagues,3 the classification system has had numerous additions and modifications as new patterns of injury have been identified.4-6 Patellar fractures are also rare in children, making up 1% of all pediatric fractures, with less than 2% of these occurring in skeletally immature children.7

We present a case of an unreported combined tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and patellar avulsion fracture in an adolescent boy. The patient and his guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with acute onset of right-knee pain and inability to ambulate after falling off a skateboard on the day of the injury. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no noteworthy medical or surgical history, including no prior fractures. On physical examination, he was noted to have a large right-knee effusion presumed to be hemarthrosis, and inability to perform a straight-leg raise against gravity. There were no neurologic deficits and his leg compartments were soft. Plain radiographs showed patella alta and numerous bony fragments believed to represent a complex tibial tubercle fracture. One bony fragment was identified closer to the patella, suggesting a possible concurrent patellar fracture (Figures 1A, 1B). A computed tomography (CT) scan further characterized both the tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and the lateral inferior pole patellar avulsion fracture (Figures 2A, 2B). The patient’s knee was immobilized, and he was admitted for soft-tissue rest and overnight observation to ensure that compartment syndrome did not develop.

Five days after injury, open reduction and internal fixation were performed. After limb exsanguination and tourniquet insufflation, the fracture was visualized through a direct midline approach. The patient was found to have a Z-type injury pattern to the extensor mechanism: an inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture, longitudinal splits of the patellar tendon, and 2 large, mainly cartilaginous tibial tubercle fracture fragments, 1 of which extended into the proximal tibial epiphysis (Ogden type III) (Figures 3A-3C). Under direct visualization, the tibial tubercle fragments were reduced and stabilized with 3 cannulated 3.5-mm titanium, partially threaded screws with washers. Smaller screws were used to prevent fragmentation of these mostly cartilaginous fragments. Anatomic reduction was ensured along the articular surface, visualized through an arthrotomy, as well as on the distal cortex (Figures 4A, 4B). The patellar avulsion fracture included a very small section of articular surface and the decision was made to preserve the fragment. Because the patellar fragment was too small for screw fixation, the fracture was secured with suture fixation through bone tunnels over a patellar bony bridge using size 2 Phantom Fiber suture (Tornier) (Figure 5). Vicryl was used to repair the longitudinal patellar tendon split as well as the capsular and paratenon traumatic tears. Layered closure was completed and intraoperative radiographs were obtained (Figures 6A, 6B) prior to placement of a cylinder cast in full extension. Postoperatively, the patient remained overnight for observation and physical therapy evaluation. He was encouraged to bear weight in his cylinder cast as tolerated with crutches to assist with ambulation.

Postoperatively, the patient was maintained in full extension in the cylinder cast for 4 weeks. After cast removal, the patient was placed in a range-of-motion brace locked in extension for ambulation. He started physical therapy and was allowed to perform prone active-knee flexion limited to 90º, with passive extension, for an additional 4 weeks. At 8 weeks, the patient was allowed full-knee motion both active and passive, and the brace was discontinued. At his 18-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported successful return to all his normal activities, including skateboarding, with no apparent limitation in motion or weight-bearing. Examination at that time demonstrated knee range of motion from 5º in hyperextension to 135º in flexion, with his left knee having 5º in hyperextension and 145º in flexion. The patient appeared to have no gait abnormalities, and radiographs showed healed fractures. Because of a concern that continued compression across his tibial physis could lead to greater risk of growth arrest, the decision was made to remove the implants when radiographs showed healing. The patient returned to surgery at 20 weeks for implant removal. At 6 weeks after implant removal, the patient had returned to full activity with no residual pain and full-knee flexion equal to the uninvolved left knee. He was able to perform a stable single-leg squat on his affected leg, and his single-leg hop for distance was the same as his uninvolved leg. He was allowed to return to full sports activity. The patient will be followed with serial radiographs at 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months to look for premature physeal arrest. If an arrest occurs, treatment will be dictated by the extent of the arrest and the potential to cause either limb-length difference or angular deformity.

Discussion

Tibial tubercle fractures typically result from quadriceps contraction during sporting activities, predominantly in adolescent boys with open physes. Numerous modifications and additions have been made to the original classification of such fractures by Watson-Jones,2 most notably by Ogden and colleagues3 in 1980. These additions have included combined tendon avulsions and tubercle fractures as described by Frankl and coauthors,4 complete proximal tibial physeal separation now classified as type 4 by Ryu and Debenham,5 and a “Y” fracture configuration now termed type 5 by McKoy and Stanitski.6 Pandya and colleagues8 reported on 41 tibial tubercle fractures and described a new classification scheme based on the known anatomical closure pattern of the proximal tibial physis and tibial tubercle apophysis. The authors stressed the role of advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, in preoperative management of these complex high-energy fractures in adolescents, and the need for intraoperative arthroscopy or arthrotomy to ensure anatomical reduction of the articular involvement.

Tibial tubercle fractures and extensor mechanism injuries that do not fit these classification patterns have also been described. In 1979, Houghton and Ackroyd9 reported 3 cases of acute loss of extensor mechanism secondary to a traumatic patellar sleeve avulsion. In 1995, Berg10 described an ipsilateral inferior pole osteochondral patellar avulsion fracture with patellar tendon avulsion without fracture at the tubercle in a 12-year-old boy. Another variant was described in a 2002 case series of 3 adolescent boys who underwent operative fixation for tibial metaphyseal partial-sleeve avulsion injuries.11

Conclusion

We report a case of combined ipsilateral inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture and an intra-articular tibial tubercle avulsion fracture with intervening longitudinal patellar tendon split. Preoperative standard radiographs were confusing, given the bony fragment high up by the patella, but use of advanced imaging, in this case CT, allowed us to fully characterize the origin of fracture fragments and realize we were dealing with a unique fracture pattern previously unreported in a pediatric patient. The CT findings allowed us to be better prepared preoperatively by having options for fixation of the patellar fracture, and the extent of articular involvement led us to decide that intra-articular evaluation would be required. Through the use of an open arthrotomy, anatomical articular reduction could be visualized and stabilized with screw fixation of the large, mostly cartilaginous tubercle fracture. Following the principles described by Pandya and colleagues,8 anatomical reduction was achieved, and, 6 months after the original surgery, the patient had return of full motion, clinical and radiographic union, and no clinical pain or limp, with no retained metallic implants across the tibial apophysis. Longer-term follow-up as planned will demonstrate any growth abnormality that would require further surgical intervention.

Tibial tubercle fractures are rare injuries accounting for less than 1% of all pediatric physeal injuries.1 The original classification scheme for such fractures was proposed by Watson-Jones.2 Initially modified by Ogden and colleagues,3 the classification system has had numerous additions and modifications as new patterns of injury have been identified.4-6 Patellar fractures are also rare in children, making up 1% of all pediatric fractures, with less than 2% of these occurring in skeletally immature children.7

We present a case of an unreported combined tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and patellar avulsion fracture in an adolescent boy. The patient and his guardian provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 12-year-old boy presented to the emergency department with acute onset of right-knee pain and inability to ambulate after falling off a skateboard on the day of the injury. The patient was otherwise healthy and had no noteworthy medical or surgical history, including no prior fractures. On physical examination, he was noted to have a large right-knee effusion presumed to be hemarthrosis, and inability to perform a straight-leg raise against gravity. There were no neurologic deficits and his leg compartments were soft. Plain radiographs showed patella alta and numerous bony fragments believed to represent a complex tibial tubercle fracture. One bony fragment was identified closer to the patella, suggesting a possible concurrent patellar fracture (Figures 1A, 1B). A computed tomography (CT) scan further characterized both the tibial tubercle avulsion fracture and the lateral inferior pole patellar avulsion fracture (Figures 2A, 2B). The patient’s knee was immobilized, and he was admitted for soft-tissue rest and overnight observation to ensure that compartment syndrome did not develop.

Five days after injury, open reduction and internal fixation were performed. After limb exsanguination and tourniquet insufflation, the fracture was visualized through a direct midline approach. The patient was found to have a Z-type injury pattern to the extensor mechanism: an inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture, longitudinal splits of the patellar tendon, and 2 large, mainly cartilaginous tibial tubercle fracture fragments, 1 of which extended into the proximal tibial epiphysis (Ogden type III) (Figures 3A-3C). Under direct visualization, the tibial tubercle fragments were reduced and stabilized with 3 cannulated 3.5-mm titanium, partially threaded screws with washers. Smaller screws were used to prevent fragmentation of these mostly cartilaginous fragments. Anatomic reduction was ensured along the articular surface, visualized through an arthrotomy, as well as on the distal cortex (Figures 4A, 4B). The patellar avulsion fracture included a very small section of articular surface and the decision was made to preserve the fragment. Because the patellar fragment was too small for screw fixation, the fracture was secured with suture fixation through bone tunnels over a patellar bony bridge using size 2 Phantom Fiber suture (Tornier) (Figure 5). Vicryl was used to repair the longitudinal patellar tendon split as well as the capsular and paratenon traumatic tears. Layered closure was completed and intraoperative radiographs were obtained (Figures 6A, 6B) prior to placement of a cylinder cast in full extension. Postoperatively, the patient remained overnight for observation and physical therapy evaluation. He was encouraged to bear weight in his cylinder cast as tolerated with crutches to assist with ambulation.

Postoperatively, the patient was maintained in full extension in the cylinder cast for 4 weeks. After cast removal, the patient was placed in a range-of-motion brace locked in extension for ambulation. He started physical therapy and was allowed to perform prone active-knee flexion limited to 90º, with passive extension, for an additional 4 weeks. At 8 weeks, the patient was allowed full-knee motion both active and passive, and the brace was discontinued. At his 18-week follow-up appointment, the patient reported successful return to all his normal activities, including skateboarding, with no apparent limitation in motion or weight-bearing. Examination at that time demonstrated knee range of motion from 5º in hyperextension to 135º in flexion, with his left knee having 5º in hyperextension and 145º in flexion. The patient appeared to have no gait abnormalities, and radiographs showed healed fractures. Because of a concern that continued compression across his tibial physis could lead to greater risk of growth arrest, the decision was made to remove the implants when radiographs showed healing. The patient returned to surgery at 20 weeks for implant removal. At 6 weeks after implant removal, the patient had returned to full activity with no residual pain and full-knee flexion equal to the uninvolved left knee. He was able to perform a stable single-leg squat on his affected leg, and his single-leg hop for distance was the same as his uninvolved leg. He was allowed to return to full sports activity. The patient will be followed with serial radiographs at 4 months, 8 months, and 12 months to look for premature physeal arrest. If an arrest occurs, treatment will be dictated by the extent of the arrest and the potential to cause either limb-length difference or angular deformity.

Discussion

Tibial tubercle fractures typically result from quadriceps contraction during sporting activities, predominantly in adolescent boys with open physes. Numerous modifications and additions have been made to the original classification of such fractures by Watson-Jones,2 most notably by Ogden and colleagues3 in 1980. These additions have included combined tendon avulsions and tubercle fractures as described by Frankl and coauthors,4 complete proximal tibial physeal separation now classified as type 4 by Ryu and Debenham,5 and a “Y” fracture configuration now termed type 5 by McKoy and Stanitski.6 Pandya and colleagues8 reported on 41 tibial tubercle fractures and described a new classification scheme based on the known anatomical closure pattern of the proximal tibial physis and tibial tubercle apophysis. The authors stressed the role of advanced imaging, such as CT or magnetic resonance imaging, in preoperative management of these complex high-energy fractures in adolescents, and the need for intraoperative arthroscopy or arthrotomy to ensure anatomical reduction of the articular involvement.

Tibial tubercle fractures and extensor mechanism injuries that do not fit these classification patterns have also been described. In 1979, Houghton and Ackroyd9 reported 3 cases of acute loss of extensor mechanism secondary to a traumatic patellar sleeve avulsion. In 1995, Berg10 described an ipsilateral inferior pole osteochondral patellar avulsion fracture with patellar tendon avulsion without fracture at the tubercle in a 12-year-old boy. Another variant was described in a 2002 case series of 3 adolescent boys who underwent operative fixation for tibial metaphyseal partial-sleeve avulsion injuries.11

Conclusion

We report a case of combined ipsilateral inferior lateral patellar avulsion fracture and an intra-articular tibial tubercle avulsion fracture with intervening longitudinal patellar tendon split. Preoperative standard radiographs were confusing, given the bony fragment high up by the patella, but use of advanced imaging, in this case CT, allowed us to fully characterize the origin of fracture fragments and realize we were dealing with a unique fracture pattern previously unreported in a pediatric patient. The CT findings allowed us to be better prepared preoperatively by having options for fixation of the patellar fracture, and the extent of articular involvement led us to decide that intra-articular evaluation would be required. Through the use of an open arthrotomy, anatomical articular reduction could be visualized and stabilized with screw fixation of the large, mostly cartilaginous tubercle fracture. Following the principles described by Pandya and colleagues,8 anatomical reduction was achieved, and, 6 months after the original surgery, the patient had return of full motion, clinical and radiographic union, and no clinical pain or limp, with no retained metallic implants across the tibial apophysis. Longer-term follow-up as planned will demonstrate any growth abnormality that would require further surgical intervention.

1. Mosier SM, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(2):181-184.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1955.

3. Ogden JA, Tross RB, Murphy MJ. Fractures of the tibial tuberosity in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(2):205-215.

4. Frankl U, Wasilewski SA, Healy WL. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(9):1411-1413.

5. Ryu RK, Debenham JO. An unusual avulsion fracture of the proximal tibial epiphysis. Case report and proposed addition to the Watson-Jones classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;(194):181-184.

6. McKoy BE, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(3):397-403.

7. Hunt DM, Somashekar N. A review of sleeve fractures of the patella in children. Knee. 2005;12:3-7.

8. Pandya NK, Edmonds EW, Roocroft JH, Mubarak SJ. Tibial tubercle fractures: complications, classification, and the need for intra-articular assessment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(8):749-759.

9. Houghton GR, Ackroyd CE. Sleeve fractures of the patella in children: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61(2):165-168.

10. Berg EE. Bipolar infrapatellar tendon rupture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(3):302-303.

11. Davidson D, Letts M. Partial sleeve fractures of the tibia in children: an unusual fracture pattern. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):36-40.

1. Mosier SM, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24(2):181-184.

2. Watson-Jones R. Fractures and Joint Injuries. Baltimore, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1955.

3. Ogden JA, Tross RB, Murphy MJ. Fractures of the tibial tuberosity in adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62(2):205-215.

4. Frankl U, Wasilewski SA, Healy WL. Avulsion fracture of the tibial tubercle with avulsion of the patellar ligament. Report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72(9):1411-1413.

5. Ryu RK, Debenham JO. An unusual avulsion fracture of the proximal tibial epiphysis. Case report and proposed addition to the Watson-Jones classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;(194):181-184.

6. McKoy BE, Stanitski CL. Acute tibial tubercle avulsion fractures. Orthop Clin North Am. 2003;34(3):397-403.

7. Hunt DM, Somashekar N. A review of sleeve fractures of the patella in children. Knee. 2005;12:3-7.

8. Pandya NK, Edmonds EW, Roocroft JH, Mubarak SJ. Tibial tubercle fractures: complications, classification, and the need for intra-articular assessment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2012;32(8):749-759.

9. Houghton GR, Ackroyd CE. Sleeve fractures of the patella in children: a report of three cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1979;61(2):165-168.

10. Berg EE. Bipolar infrapatellar tendon rupture. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15(3):302-303.

11. Davidson D, Letts M. Partial sleeve fractures of the tibia in children: an unusual fracture pattern. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22(1):36-40.