User login

Sexual dysfunction in women: Can we talk about it?

Many women experience some form of sexual dysfunction, be it lack of desire, lack of arousal, failure to achieve orgasm, or pain during sexual activity.

Sexual health may be difficult to discuss, for both the patient and the provider. Here, we describe how primary care physicians can approach this topic, assess potential problems, and begin treatment.

A COMMON PROBLEM

The age-adjusted prevalence of sexual dysfunction in US women was reported at 44% in the Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated With Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking (PRESIDE) study,1 but the prevalence of distress associated with sexual dysfunction was 12%. The most common type of sexual dysfunction reported by women was low sexual desire, a finding consistent with that of another large population-based study.2

While the prevalence of any type of sexual dysfunction was highest in women over age 65,1 the prevalence of distress was lowest in this age group and highest in midlife between the ages of 45 and 65. The diagnostic criteria require both a problem and distress over the problem.

Sexual dysfunction negatively affects quality of life and emotional health, regardless of age.3

LIFESTYLE AND SEXUAL FUNCTION

Various lifestyle factors have been linked to either more or less sexual activity. For example, a Mediterranean diet was associated with increased sexual activity, as were social activity, social support, psychological well-being, self-reported good quality of life, moderate alcohol intake, absence of tobacco use, a normal body mass index, and exercise.4–6 A higher sense of purpose in life has been associated with greater sexual enjoyment.7

Conversely, sexual inactivity has been associated with alcohol misuse, an elevated body mass index, and somatization.4–6

SEXUAL RESPONSE: LINEAR OR CIRCULAR?

Masters and Johnson8 initially proposed a linear model of human sexual response, which Kaplan later modified to include desire and applied to both men and women.9,10 This model presumed that sexual response begins with spontaneous sexual desire, followed by arousal, and then (sometimes) orgasm and resolution.

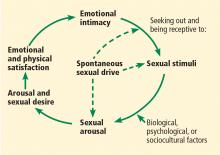

In 2000, Basson11 proposed a circular, intimacy-based model of sexual response in women that acknowledged the complexities involved in a woman’s motivation to be sexual (Figure 1). While a woman may enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, she may also enter it as sexually neutral, with arousal in response to a sexual stimulus. Emotional intimacy is an important part of the cycle, and emotional closeness and bonding with the partner may provide motivation for a woman to enter into the cycle again in the future.

In a Danish survey,12 more people of both sexes said the 2 linear models described their experiences better than the circular model, but more women than men endorsed the circular model, and more men than women endorsed a linear model.

In evaluating women who complain of low sexual desire, clinicians should be aware that women, particularly those who are postmenopausal, may not enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, but instead may experience arousal in response to a sexual stimulus followed by desire—ie, responsive rather than spontaneous sexual desire. Sexual arousal may precede desire, especially for women in long-term relationships, and emotional intimacy is a key driver for sexual engagement in women.11

CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION IN WOMEN

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and “not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.”13

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),14 published in 2013, defines three categories of sexual dysfunction in women:

- Female sexual interest and arousal disorder

- Female sexual orgasmic disorder

- Genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

To meet the diagnosis of any of these, symptoms must:

- Persist for at least 6 months

- Occur in 75% to 100% of sexual encounters

- Be accompanied by personal distress

- Not be related to another psychological or medical condition, medication or substance use, or relationship distress.

Sexual problems may be lifelong or acquired after a period of normal functioning, and may be situational (present only in certain situations) or generalized (present in all situations).

Female sexual interest and arousal disorder used to be 2 separate categories in earlier editions of the DSM. Proponents of merging the 2 categories in DSM-5 cited several reasons, including difficulty in clearly distinguishing desire from other motivations for sexual activity, the relatively low reporting of fantasy in women, the complexity of distinguishing spontaneous from responsive desire, and the common co-occurrence of decreased desire and arousal difficulties.15

Other experts, however, have recommended keeping the old, separate categories of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and arousal disorder.16 The recommendation to preserve the diagnostic category of hypoactive sexual desire disorder is based on robust observational and registry data, as well as the results of randomized controlled trials that used the old criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder to assess responses to pharmacologic treatment of this condition.17–19 In addition, this classification as a separate and distinct diagnosis is consistent with the nomenclature used in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and was endorsed by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine in 2015.16

HOW TO ASK ABOUT SEXUAL HEALTH

Assessment of sexual health concerns should be a part of a routine health examination, particularly after childbirth and other major medical, surgical, psychological, and life events. Women are unlikely to bring up sexual health concerns with their healthcare providers, but instead hope that their providers will bring up the topic.20

Barriers to the discussion include lack of provider education and training, patient and provider discomfort, perceived lack of time during an office visit, and lack of approved treatments.21,22 Additionally, older women are less likely than men to discuss sexual health with their providers.23 Other potential barriers to communication include negative societal attitudes about sexuality in women and in older individuals.24,25 To overcome these barriers:

Legitimize sexual health as an important health concern and normalize its discussion as part of a routine clinical health assessment. Prefacing a query about sexual health with a normalizing and universalizing statement can help: eg, “Many women going through menopause have concerns about their sexual health. Do you have any sexual problems or concerns?” Table 1 contains examples of questions to use for initial screening for sexual dysfunction.22,26

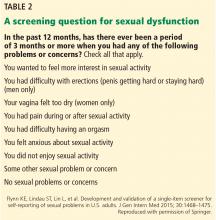

Flynn et al27 proposed a validated single-question checklist to screen for sexual dysfunction that is an efficient way to identify specific sexual concerns, guide selection of interventions, and facilitate patient-provider communication (Table 2).

Don’t judge and don’t make assumptions about sexuality and sexual practices.

Assure confidentiality.

Use simple, direct language that is appropriate for the patient’s age, ethnicity, culture, and level of health literacy.3

Take a thorough history (sexual and reproductive, medical-surgical, and psychosocial).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Perform a focused physical examination to evaluate for potential causes of pain (eg, infectious causes, vulvar dermatoses, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction). The examination is also an opportunity to teach the patient about anatomy and normal sexual function.

No standard laboratory tests or imaging studies are required for the assessment of sexual dysfunction.28

IT’S NOT JUST PHYSICAL

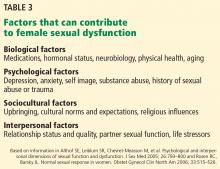

Evaluation and treatment of female sexual dysfunction is guided by the biopsychosocial model, with potential influences from the biological, psychological, sociocultural, and interpersonal realms (Table 3).29,30

Biological factors include pelvic surgery, cancer and its treatment, neurologic diseases, and vascular diseases. Medications, including antidepressants, narcotics, anticholinergics, antihistamines, antihypertensives, oral contraceptives, and antiestrogens may also adversely affect sexual response.26

Psychological factors include a history of sexual abuse or trauma, body image concerns, distraction, stress, anxiety, depression, and personality disorders.22

Sociocultural factors include lack of sex education, unrealistic expectations, cultural norms, and religious influences.

Relationship factors include conflict with one’s partner, lack of emotional intimacy, absence of a partner, and partner sexual dysfunction. While there appears to be a close link between sexual satisfaction and a woman’s relationship with her partner in correlational studies and in clinical experience, there has been little research about relationship factors and their contribution to desire and arousal concerns.31 Sexual dysfunction in one’s partner (eg, erectile dysfunction) has been shown to negatively affect the female partner’s sexual desire.32

GENERAL APPROACH TO TREATMENT

In treating sexual health problems in women, we address contributing factors identified during the initial assessment.

A multidisciplinary approach

As sexual dysfunction in women is often multifactorial, management of the problem is well suited to a multidisciplinary approach. The team of providers may include:

- A medical provider (primary care provider, gynecologist, or sexual health specialist) to coordinate care and manage biological factors contributing to sexual dysfunction

- A physical therapist with expertise in treating pelvic floor disorders

- A psychologist to address psychological, relational, and sociocultural contributors to sexual dysfunction

- A sex therapist (womenshealthapta.org, aasect.org) to facilitate treatment of tight, tender pelvic floor muscles through education and guidance about kinesthetic awareness, muscle relaxation, and dilator therapy.33

Even in the initial visit, the primary care provider can educate, reassure regarding normal sexual function, and treat conditions such as genitourinary syndrome of menopause and antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. The PLISSIT model (Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy) is a useful tool for initiating counseling about sexual health (Table 4).34

AGING VS MENOPAUSE

Aging can affect sexual function in both men and women. About 40% of women experience changes in sexual function around the menopausal transition, with common complaints being loss of sexual responsiveness and desire, sexual pain, decreased sexual activity, and partner sexual dysfunction.35 However, studies seem to show that while menopause results in hormonal changes that affect sexual function, other factors may have a greater impact.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation36 found vaginal and pelvic pain and decreased sexual desire were associated with the menopausal transition, but other sexual health outcomes (frequency of sexual activities, arousal, importance of sex, emotional satisfaction, or physical pleasure) were not. Physical and psychological health, marital status, and a change in relationship were all associated with differences in sexual health.

The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study II37 found a greater association between physical and mental health, relationship status, and smoking and women’s sexual functioning than menopausal status.

The Penn Ovarian Aging Study38 found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction included postmenopausal status, anxiety, and absence of a sexual partner.

The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project39 also found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Sexual dysfunction with distress was associated with relationship factors and depression.37

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause and its treatment

As the ovaries shut down during menopause, estradiol levels decrease. Nearly 50% of women experience symptoms related to genitourinary syndrome of menopause (formerly called atrophic vaginitis or vulvovaginal atrophy).40,41 These symptoms include vaginal dryness and discomfort or pain with sexual activity, but menopausal hormone loss can also result in reduced genital blood flow, decreased sensory perception, and decreased sexual responsiveness.22

Estrogen is the most effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, with low-dose vaginal preparations preferred over systemic ones for isolated vulvar and vaginal symptoms.40 While estrogen is effective for vaginal dryness and sexual pain associated with estrogen loss, replacing estrogen systemically has not been associated with improvements in sexual desire.42

DEPRESSION AND ANTIDEPRESSANT-INDUCED SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Depression increases the risk of sexual dysfunction, and vice versa.

A meta-analysis that included 12 studies involving almost 15,000 patients confirmed that depression increased the risk of sexual dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction increased the risk of depression.43 This interaction may be related to the overlap in affected neurotransmitters and neuroendocrine systems.44

In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial, Ishak et al45 found that patients treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) who experienced remission of depression had a lower prevalence of impaired sexual satisfaction and much greater improvements in sexual satisfaction than did those who remained depressed. The severity of depressive symptoms predicted impairment in sexual satisfaction, which in turn predicted poorer quality of life. The authors suggested that physicians encourage patients to remain on SSRI treatment, given that improvement in depressive symptoms is likely to improve sexual satisfaction.

Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction

As many as 70% of patients taking an SSRI or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) experience antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, though this is difficult to estimate across studies of different medications due to differences in methods and because many patients only report it when directly asked about it.46

Treatment of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction includes not only optimal management of depression but reassessment of the antidepressant treatment. If using only nondrug treatments for the mood disorder is not feasible, switching to (or ideally, starting with) an antidepressant with fewer sexual side effects such as mirtazapine, vilazodone, or bupropion is an option.46

A drug holiday (suspending antidepressant treatment for 1 or 2 days) has been suggested as a means of treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, but this may result in poorer control of depressive symptoms and discontinuation symptoms, and it encourages medication noncompliance.46,47

Treatment with a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (eg, sildenafil) has been studied in women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, with modest results.48

A Cochrane review reported that treatment with bupropion shows promise at higher doses (300 mg daily).49

Exercise for 20 minutes 3 times weekly is associated with improvement in antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction when the exercise is performed immediately before sexual activity.50

LOW SEXUAL DESIRE

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is defined as persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity associated with marked distress and not due exclusively to a medication, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Low or decreased sexual desire is the most commonly reported sexual health concern in women of all ages, with an unadjusted prevalence of 39.7%. When the criterion of personal distress is included, the prevalence is 8.9% in women ages 18 to 44, 12.3% in women ages 45 to 64, and 7.4% in women ages 65 and older.1

Multiple biological, psychological, and social factors may contribute to the problem. Identifying the ones that are present can help in planning treatment. A multifaceted approach may be appropriate.

Mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for low sexual desire

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is designed to improve awareness, focusing on and accepting the present moment, and directing attention away from and lessening self-criticism and evaluation of one’s sexual responsiveness.

Mindfulness-based therapy has been associated with improvements in sexual desire and associated distress.51 Similarly, the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder is supported by 3 controlled trials, although concerns exist about the adequacy of these trials, and further study is needed.52

Androgen therapy in women

In randomized controlled trials in women with low sexual desire who were either naturally or surgically menopausal, sexual function improved with testosterone therapy that resulted in mostly supraphysiologic total testosterone levels (which may not reflect free testosterone levels) with or without concurrent estrogen treatment.53–57

Testosterone is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in women, primarily because of the lack of long-term safety and efficacy data (ie, beyond 24 months). However, studies have shown no evidence of increased risk of endometrial cancer or cardiovascular disease with testosterone dosed to achieve physiologic premenopausal levels.58 Data on breast cancer risk are less clear, but observational studies over the last decade do not support an association with testosterone use in women.58 There is no clearly defined androgen deficiency syndrome in women, and androgen levels do not reliably correlate with symptoms.59

The Endocrine Society59 guidelines endorse the use of testosterone in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. They say to aim for the midnormal premenopausal range and suggest discontinuing the drug if there is no response in 6 months. They recommend checking testosterone levels at baseline, after 3 to 6 weeks of therapy, and every 6 months to monitor for excessive use, to avoid supraphysiologic dosing and to evaluate for signs of androgen excess (eg, acne, hair growth). The use of products formulated for men or those formulated by pharmacies is discouraged; however, no FDA-approved products are currently available for use in women in the United States.

Flibanserin

A postsynaptic serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist and 5-HT2A receptor agonist, flibanserin was approved by the FDA in 2015 for treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. Its mechanism of action is likely through an effect on neurotransmitters that suppresses serotonin (which has sexually inhibitory effects) and promotes dopamine and norepinephrine (which have excitatory effects).60

The efficacy of flibanserin has been demonstrated in 3 randomized controlled trials, with significant increases in the number of sexually satisfying events and in sexual desire scores and a decrease in distress associated with low sexual desire.17–19 While the increase in sexually satisfying events was modest (about 1 extra event per month), some have suggested that the frequency of sexual activity may not be the best measure of sexual function in women.61 Further, responders to this drug showed a return to near-normal premenopausal frequencies of sexual activity in a separate analysis.61

The drug is generally well tolerated, with common adverse effects being somnolence, dizziness, and fatigue.18,19 Flibanserin has been associated with orthostatic hypotension with alcohol use and carries a boxed warning highlighting this potential interaction.62 Use of this drug is contraindicated in women who drink alcohol or take medications that are moderate or strong inhibitors of CYP-3A4 (eg, some antiretroviral drugs, antihypertensive drugs, antibiotics, and fluconazole, which can increase systemic exposure to flibanserin and potential side effects), and in those with liver impairment.

SEXUAL AROUSAL DISORDERS

Female sexual arousal disorder is the persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain an adequate lubrication-swelling response of sexual excitement. Sexual arousal results from a complex interaction between genital response, central nervous system activity, and information processing of the sexual stimulus. Difficulty with sexual arousal can result from neurovascular or neuroendocrine dysfunction or impaired central nervous system processing.

Women may experience a mismatch between subjective and objective genital arousal. A subjective report of decreased genital arousal may not be confirmed with measurement of vaginal pulse amplitude by photoplethysmography.63 Even in postmenopausal women, in the absence of significant neurovascular or neuroendocrine dysfunction, it is likely that either contextual or relational variables resulting in inadequate sexual stimulation or cognitive inhibition are more important factors contributing to difficulty with sexual arousal.63

Although there are no standard recommendations for evaluation of arousal disorders and advanced testing is often unnecessary, nerve function can be assessed with genital sensory testing utilizing thermal and vibratory threshholds64; vaginal blood flow can be assessed with vaginal photoplethysmography63; and imaging of the spine and pelvis can help to rule out neurovascular pathology.

Treatment of arousal disorders

As with other forms of female sexual dysfunction, treatment of arousal disorders includes addressing contributing factors.

Although there are few data from randomized controlled trials, psychological treatments such as sensate focus exercises and masturbation training have been suggested, centered on women becoming more self-focused and assertive.31 Sensate focus exercises are a series of graded, nondemand, sensual touching exercises aimed at reducing anxiety and avoidance of sexual activity, and improving sexual communication and intimacy by the gradual reintroduction of sexual activity.65 More recently, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has been associated with improvements in sexual arousal as well as other parameters of sexual function.51

Currently, no pharmacologic treatments are recommended for arousal disorders because of a lack of evidence of efficacy and because of adverse effects.31

ORGASMIC DISORDER

Female orgasmic disorder is the marked delay, marked infrequency, or absence of orgasm, or markedly reduced intensity of orgasm.

Important considerations in evaluating orgasm disorders include psychosocial factors (eg, lack of sex education, negative feelings about sex, religiosity), psychological factors (eg, anxiety, depression, body image concerns), relational factors (eg, communication issues, lack of emotional intimacy, partner sexual dysfunction), adverse childhood or adult experiences (eg, physical, sexual, or emotional or verbal abuse), medical history (pelvic surgery, neurologic, or vascular disease) and medications (eg, SSRIs, SNRIs, and antipsychotic medications).66

Treatment of orgasmic disorder

Involving the partner in treatment is important, particularly if the difficulty with orgasm is acquired and only occurs with sex with a partner. Using the PLISSIT model to provide targeted, office-based interventions can be helpful.

Behavioral therapies such as directed masturbation, sensate focus exercises, or a combination of these have been shown to be effective, as has coital alignment during intercourse (positioning of male partner with his pelvis above the pubic bone of his partner to maximize clitoral stimulation with penile penetration).66

Hormonal therapy may be useful in postmenopausal women. However, there are no data on it for women whose primary complaint is female orgasmic disorder, and further study is needed.66

SEXUAL PAIN DISORDERS

The DSM-5 describes genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder as fear or anxiety, marked tightening or tensing of abdominal and pelvic muscles, or actual pain with vaginal penetration that is recurrent or persistent for a minimum of 6 months.14 Pain may occur with initial penetration, with deeper thrusting, or both.

Although the DSM-5 definition focuses on pain with penetration, it is important to recognize and ask about noncoital sexual pain. Women may also present with persistent vulvar pain or pain at the vulvar vestibule with provocation, (eg, sexual activity, tampon insertion, sitting), also known as provoked vestibulodynia.

Assessment of vaginal and vulvar pain includes a directed history and physical examination aimed at identifying potential etiologies or contributing factors, including infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, neurologic, traumatic, iatrogenic, or factors related to hormonal deficiency.67

Treatment of sexual pain

Removal of offending agents is a first step. This includes a thorough review of vulvar and vaginal hygiene practices and emphasis on avoiding the use of any product containing potential irritants (eg, soaps or detergents containing perfumes or dyes) and using lubricants and moisturizers without gimmicks (no warming or tingling agents or flavors). Oral contraceptives have been associated with vestibulodynia, and women in whom the sexual pain started when they started an oral contraceptive may benefit from switching to an alternate form of contraception.68

Dysfunction of pelvic floor muscles may result in sexual pain and may be a primary problem or a secondary complication related to other issues such as symptomatic genitourinary syndrome of menopause. The symptoms of nonrelaxing pelvic floor dysfunction (also known as hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction or pelvic floor tension myalgia) include pain in the pelvis with sexual activity that may linger for hours or even days, and may also include bowel and bladder dysfunction and low back pain or hip pain radiating to the thighs or groin.33 Physical therapy under the care of a physical therapist with expertise in the management of pelvic floor disorders is the cornerstone of treatment for this condition.33

Treatment of the genital and urinary symptoms related to loss of estrogen after menopause (genitourinary syndrome of menopause) includes the use of vaginal lubricants with sexual activity and vaginal moisturizers on a regular basis (2 to 5 times per week).40 Low-dose vaginal estrogen creams, rings, or tablets and the oral selective estrogen receptor antagonist ospemifene are recommended for moderate to severe symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause.40 Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone was recently approved by the FDA for treatment of dyspareunia associated with menopause.69 Topical lidocaine applied to the introitus before sexual activity has been found to be effective for reducing sexual pain in women with breast cancer, and when used in combination with vaginal lubricants and moisturizers is a practical option for women, particularly those unable to use estrogen-based therapies.70

- Shifren JL, Monz BU, Russo PA, Segreti A, Johannes CB. Sexual problems and distress in United States women: prevalence and correlates. Obstet Gynecol 2008; 112:970–978.

- Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999; 281:537–544.

- Sadovsky R, Nusbaum M. Sexual health inquiry and support is a primary care priority. J Sex Med 2006; 3:3–11.

- Alvisi S, Baldassarre M, Lambertini M, et al. Sexuality and psychopathological aspects in premenopausal women with metabolic syndrome. J Sex Med 2014; 11:2020–2028.

- Bach LE, Mortimer JA, VandeWeerd C, Corvin J. The association of physical and mental health with sexual activity in older adults in a retirement community. J Sex Med 2013; 10:2671–2678.

- Esposito K, Ciotola M, Giugliano F, et al. Mediterranean diet improves sexual function in women with the metabolic syndrome. Int J Impot Res 2007; 19:486–491.

- Prairie BA, Scheier MF, Matthews KA, Chang CC, Hess R. A higher sense of purpose in life is associated with sexual enjoyment in midlife women. Menopause 2011; 18:839–844.

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual response. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1966.

- Kaplan HS. The new sex therapy. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1974.

- Robinson PA. The modernization of sex: Havelock Ellis, Alfred Kinsey, William Masters, and Virginia Johnson. New York, NY: Harper & Row; 1976.

- Basson R. The female sexual response: a different model. J Sex Marital Ther 2000; 26:51–65.

- Giraldi A, Kristensen E, Sand M. Endorsement of models describing sexual response of men and women with a sexual partner: an online survey in a population sample of Danish adults ages 20–65 years. J Sex Med 2015; 12:116–128.

- World Health Organization. Defining sexual health. Report of a technical consultation on sexual health, 28–31 January 2002, Geneva. Geneva; 2006.

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM-5: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013.

- Brotto LA. The DSM diagnostic criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder in women. Arch Sex Behav 2010; 39:221–239.

- McCabe MP, Sharlip ID, Atalla E, et al. Definitions of sexual dysfunctions in women and men: a consensus statement from the Fourth International Consultation on Sexual Medicine 2015. J Sex Med 2016; 13:135–143.

- Derogatis LR, Komer L, Katz M, et al; VIOLET Trial Investigators. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: efficacy of flibanserin in the VIOLET study. J Sex Med 2012; 9:1074–1085.

- Katz M, DeRogatis LR, Ackerman R, et al; BEGONIA trial investigators. Efficacy of flibanserin in women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder: results from the BEGONIA trial. J Sex Med 2013; 10:1807–1815.

- Thorp J, Simon J, Dattani D, et al; DAISY trial investigators. Treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women: efficacy of flibanserin in the DAISY study. J Sex Med 2012; 9:793–804.

- Berman L, Berman J, Felder S, et al. Seeking help for sexual function complaints: what gynecologists need to know about the female patient's experience. Fertil Steril 2003; 79:572–576.

- Kingsberg SA. Taking a sexual history. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2006; 33:535–547.

- Kingsberg SA, Rezaee RL. Hypoactive sexual desire in women. Menopause 2013; 20:1284–1300.

- Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, Levinson W, O’Muircheartaigh CA, Waite LJ. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med 2007; 357:762–774.

- Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med 2004; 58:2093–2103.

- Lindau ST, Leitsch SA, Lundberg KL, Jerome J. Older women's attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: a community-based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006; 15:747–753.

- Faubion SS, Rullo JE. Sexual dysfunction in women: a practical approach. Am Fam Physician 2015; 92:281–288.

- Flynn KE, Lindau ST, Lin L, et al. Development and validation of a single-item screener for self-reporting sexual problems in US adults. J Gen Intern Med 2015; 30:1468–1475.

- Latif EZ, Diamond MP. Arriving at the diagnosis of female sexual dysfunction. Fertil Steril 2013; 100:898–904.

- Althof SE, Leiblum SR, Chevret-Measson M, et al. Psychological and interpersonal dimensions of sexual function and dysfunction. J Sex Med 2005; 2:793–800.

- Rosen RC, Barsky JL. Normal sexual response in women. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2006; 33:515–526.

- Brotto LA, Bitzer J, Laan E, Leiblum S, Luria M. Women's sexual desire and arousal disorders. J Sex Med 2010; 7:586–614.

- Rubio-Aurioles E, Kim ED, Rosen RC, et al. Impact on erectile function and sexual quality of life of couples: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of tadalafil taken once daily. J Sex Med 2009; 6:1314–1323.

- Faubion SS, Shuster LT, Bharucha AE. Recognition and management of nonrelaxing pelvic floor dysfunction. Mayo Clin Proc 2012; 87:187–193.

- Annon JS. The PLISSIT model: a proposed conceptual scheme for the behavioral treatment of sexual problems. J Sex Educ Ther 1976; 2:1–15.

- Sarrel PM. Sexuality and menopause. Obstet Gynecol 1990; 75(suppl 4):26S–30S; discussion 31S–35S.

- Avis NE, Brockwell S, Randolph JF, Jr, et al. Longitudinal changes in sexual functioning as women transition through menopause: results from the Study of Women's Health Across the Nation. Menopause 2009; 16:442–452.

- Avis NE, Stellato R, Crawford S, Johannes C, Longcope C. Is there an association between menopause status and sexual functioning? Menopause 2000; 7:297–309.

- Gracia CR, Freeman EW, Sammel MD, Lin H, Mogul M. Hormones and sexuality during transition to menopause. Obstet Gynecol 2007; 109:831–840.

- Dennerstein L, Guthrie JR, Hayes RD, DeRogatis LR, Lehert P. Sexual function, dysfunction, and sexual distress in a prospective, population-based sample of mid-aged, Australian-born women. J Sex Med 2008; 5:2291–2299.

- Management of symptomatic vulvovaginal atrophy: 2013 position statement of The North American Menopause Society. Menopause 2013; 20:888–902.

- Mac Bride MB, Rhodes DJ, Shuster LT. Vulvovaginal atrophy. Mayo Clin Proc 2010; 85:87–94.

- Nastri CO, Lara LA, Ferriani RA, Rosa ESAC, Figueiredo JB, Martins WP. Hormone therapy for sexual function in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 6:CD009672.

- Atlantis E, Sullivan T. Bidirectional association between depression and sexual dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sex Med 2012; 9:1497–1507.

- Clayton AH, Maserejian NN, Connor MK, Huang L, Heiman JR, Rosen RC. Depression in premenopausal women with HSDD: baseline findings from the HSDD Registry for Women. Psychosom Med 2012; 74:305–311.

- Ishak WW, Christensen S, Sayer G, et al. Sexual satisfaction and quality of life in major depressive disorder before and after treatment with citalopram in the STAR*D study. J Clin Psychiatry 2013; 74:256–261.

- Clayton AH, Croft HA, Handiwala L. Antidepressants and sexual dysfunction: mechanisms and clinical implications. Postgrad Med 2014; 126:91–99.

- Rothschild AJ. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-induced sexual dysfunction: efficacy of a drug holiday. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:1514–1516.

- Nurnberg HG, Hensley PL, Heiman JR, Croft HA, Debattista C, Paine S. Sildenafil treatment of women with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2008; 300:395–404.

- Taylor MJ, Rudkin L, Bullemor-Day P, Lubin J, Chukwujekwu C, Hawton K. Strategies for managing sexual dysfunction induced by antidepressant medication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 5:CD003382.

- Lorenz TA, Meston CM. Exercise improves sexual function in women taking antidepressants: results from a randomized crossover trial. Depress Anxiety 2014; 31:188–195.

- Brotto LA, Basson R. Group mindfulness-based therapy significantly improves sexual desire in women. Behav Res Ther 2014; 5743–5754.

- Pyke RE, Clayton AH. Psychological treatment trials for hypoactive sexual desire disorder: a sexual medicine critique and perspective. J Sex Med 2015; 12:2451–2458.

- Cappelletti M, Wallen K. Increasing women's sexual desire: the comparative effectiveness of estrogens and androgens. Horm Behav 2016; 78:178–193.

- Davis SR, Moreau M, Kroll R, et al. Testosterone for low libido in postmenopausal women not taking estrogen. N Engl J Med 2008; 359:2005–2017.

- Davis SR, van der Mooren MJ, van Lunsen RH, et al. Efficacy and safety of a testosterone patch for the treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in surgically menopausal women: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Menopause 2006; 13:387–396.

- Panay N, Al-Azzawi F, Bouchard C, et al. Testosterone treatment of HSDD in naturally menopausal women: the ADORE study. Climacteric 2010; 13:121–131.

- Somboonporn W, Davis S, Seif MW, Bell R. Testosterone for peri- and postmenopausal women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 4:CD004509.

- Davis SR. Cardiovascular and cancer safety of testosterone in women. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2011; 18:198–203.

- Wierman ME, Arlt W, Basson R, et al. Androgen therapy in women: a reappraisal: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2014; 99:3489–3510.

- Stahl SM, Sommer B, Allers KA. Multifunctional pharmacology of flibanserin: possible mechanism of therapeutic action in hypoactive sexual desire disorder. J Sex Med 2011; 8:15–27.

- Simon JA, Goldstein I, Kim N, Freedman M, Parish S. Flibanserin approval: facts or feelings? Sex Med 2016; 4:e69–e70.

- Joffe HV, Chang C, Sewell C, et al. FDA approval of flibanserin—treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder. N Engl J Med 2016; 374:101–104.

- van Lunsen RH, Laan E. Genital vascular responsiveness and sexual feelings in midlife women: psychophysiologic, brain, and genital imaging studies. Menopause 2004; 11:741–748.

- Beco J, Seidel L, Albert A. Normative values of skin temperature and thermal sensory thresholds in the pudendal nerve territory. Neurourol Urodyn 2015; 34:571–577.

- Masters WH, Johnson VE. Human sexual inadequacy. Boston, MA: Little, Brown and Company; 1970.

- Laan E, Rellini AH, Barnes T; International Society for Sexual Medicine. Standard operating procedures for female orgasmic disorder: consensus of the International Society for Sexual Medicine. J Sex Med 2013; 10:74–82.

- Bornstein J, Goldstein A, Coady D. Consensus terminology and classification of persistent vulvar pain. Vulvar pain/Vulvodynia Nomenclature Consensus Conference. Annapolis, MD; 2015.

- Burrows LJ, Goldstein AT. The treatment of vestibulodynia with topical estradiol and testosterone. Sex Med 2013; 1:30–33.

- Labrie F. Efficacy of intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) on moderate to severe dyspareunia and vaginal dryness, symptoms of vulvovaginal atrophy, and of the genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Manopause 2016; 23:243–256.

- Goetsch MF, Lim JY, Caughey AB. A practical solution for dyspareunia in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33:3394–3400.

Many women experience some form of sexual dysfunction, be it lack of desire, lack of arousal, failure to achieve orgasm, or pain during sexual activity.

Sexual health may be difficult to discuss, for both the patient and the provider. Here, we describe how primary care physicians can approach this topic, assess potential problems, and begin treatment.

A COMMON PROBLEM

The age-adjusted prevalence of sexual dysfunction in US women was reported at 44% in the Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated With Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking (PRESIDE) study,1 but the prevalence of distress associated with sexual dysfunction was 12%. The most common type of sexual dysfunction reported by women was low sexual desire, a finding consistent with that of another large population-based study.2

While the prevalence of any type of sexual dysfunction was highest in women over age 65,1 the prevalence of distress was lowest in this age group and highest in midlife between the ages of 45 and 65. The diagnostic criteria require both a problem and distress over the problem.

Sexual dysfunction negatively affects quality of life and emotional health, regardless of age.3

LIFESTYLE AND SEXUAL FUNCTION

Various lifestyle factors have been linked to either more or less sexual activity. For example, a Mediterranean diet was associated with increased sexual activity, as were social activity, social support, psychological well-being, self-reported good quality of life, moderate alcohol intake, absence of tobacco use, a normal body mass index, and exercise.4–6 A higher sense of purpose in life has been associated with greater sexual enjoyment.7

Conversely, sexual inactivity has been associated with alcohol misuse, an elevated body mass index, and somatization.4–6

SEXUAL RESPONSE: LINEAR OR CIRCULAR?

Masters and Johnson8 initially proposed a linear model of human sexual response, which Kaplan later modified to include desire and applied to both men and women.9,10 This model presumed that sexual response begins with spontaneous sexual desire, followed by arousal, and then (sometimes) orgasm and resolution.

In 2000, Basson11 proposed a circular, intimacy-based model of sexual response in women that acknowledged the complexities involved in a woman’s motivation to be sexual (Figure 1). While a woman may enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, she may also enter it as sexually neutral, with arousal in response to a sexual stimulus. Emotional intimacy is an important part of the cycle, and emotional closeness and bonding with the partner may provide motivation for a woman to enter into the cycle again in the future.

In a Danish survey,12 more people of both sexes said the 2 linear models described their experiences better than the circular model, but more women than men endorsed the circular model, and more men than women endorsed a linear model.

In evaluating women who complain of low sexual desire, clinicians should be aware that women, particularly those who are postmenopausal, may not enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, but instead may experience arousal in response to a sexual stimulus followed by desire—ie, responsive rather than spontaneous sexual desire. Sexual arousal may precede desire, especially for women in long-term relationships, and emotional intimacy is a key driver for sexual engagement in women.11

CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION IN WOMEN

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and “not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.”13

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),14 published in 2013, defines three categories of sexual dysfunction in women:

- Female sexual interest and arousal disorder

- Female sexual orgasmic disorder

- Genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

To meet the diagnosis of any of these, symptoms must:

- Persist for at least 6 months

- Occur in 75% to 100% of sexual encounters

- Be accompanied by personal distress

- Not be related to another psychological or medical condition, medication or substance use, or relationship distress.

Sexual problems may be lifelong or acquired after a period of normal functioning, and may be situational (present only in certain situations) or generalized (present in all situations).

Female sexual interest and arousal disorder used to be 2 separate categories in earlier editions of the DSM. Proponents of merging the 2 categories in DSM-5 cited several reasons, including difficulty in clearly distinguishing desire from other motivations for sexual activity, the relatively low reporting of fantasy in women, the complexity of distinguishing spontaneous from responsive desire, and the common co-occurrence of decreased desire and arousal difficulties.15

Other experts, however, have recommended keeping the old, separate categories of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and arousal disorder.16 The recommendation to preserve the diagnostic category of hypoactive sexual desire disorder is based on robust observational and registry data, as well as the results of randomized controlled trials that used the old criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder to assess responses to pharmacologic treatment of this condition.17–19 In addition, this classification as a separate and distinct diagnosis is consistent with the nomenclature used in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and was endorsed by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine in 2015.16

HOW TO ASK ABOUT SEXUAL HEALTH

Assessment of sexual health concerns should be a part of a routine health examination, particularly after childbirth and other major medical, surgical, psychological, and life events. Women are unlikely to bring up sexual health concerns with their healthcare providers, but instead hope that their providers will bring up the topic.20

Barriers to the discussion include lack of provider education and training, patient and provider discomfort, perceived lack of time during an office visit, and lack of approved treatments.21,22 Additionally, older women are less likely than men to discuss sexual health with their providers.23 Other potential barriers to communication include negative societal attitudes about sexuality in women and in older individuals.24,25 To overcome these barriers:

Legitimize sexual health as an important health concern and normalize its discussion as part of a routine clinical health assessment. Prefacing a query about sexual health with a normalizing and universalizing statement can help: eg, “Many women going through menopause have concerns about their sexual health. Do you have any sexual problems or concerns?” Table 1 contains examples of questions to use for initial screening for sexual dysfunction.22,26

Flynn et al27 proposed a validated single-question checklist to screen for sexual dysfunction that is an efficient way to identify specific sexual concerns, guide selection of interventions, and facilitate patient-provider communication (Table 2).

Don’t judge and don’t make assumptions about sexuality and sexual practices.

Assure confidentiality.

Use simple, direct language that is appropriate for the patient’s age, ethnicity, culture, and level of health literacy.3

Take a thorough history (sexual and reproductive, medical-surgical, and psychosocial).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Perform a focused physical examination to evaluate for potential causes of pain (eg, infectious causes, vulvar dermatoses, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction). The examination is also an opportunity to teach the patient about anatomy and normal sexual function.

No standard laboratory tests or imaging studies are required for the assessment of sexual dysfunction.28

IT’S NOT JUST PHYSICAL

Evaluation and treatment of female sexual dysfunction is guided by the biopsychosocial model, with potential influences from the biological, psychological, sociocultural, and interpersonal realms (Table 3).29,30

Biological factors include pelvic surgery, cancer and its treatment, neurologic diseases, and vascular diseases. Medications, including antidepressants, narcotics, anticholinergics, antihistamines, antihypertensives, oral contraceptives, and antiestrogens may also adversely affect sexual response.26

Psychological factors include a history of sexual abuse or trauma, body image concerns, distraction, stress, anxiety, depression, and personality disorders.22

Sociocultural factors include lack of sex education, unrealistic expectations, cultural norms, and religious influences.

Relationship factors include conflict with one’s partner, lack of emotional intimacy, absence of a partner, and partner sexual dysfunction. While there appears to be a close link between sexual satisfaction and a woman’s relationship with her partner in correlational studies and in clinical experience, there has been little research about relationship factors and their contribution to desire and arousal concerns.31 Sexual dysfunction in one’s partner (eg, erectile dysfunction) has been shown to negatively affect the female partner’s sexual desire.32

GENERAL APPROACH TO TREATMENT

In treating sexual health problems in women, we address contributing factors identified during the initial assessment.

A multidisciplinary approach

As sexual dysfunction in women is often multifactorial, management of the problem is well suited to a multidisciplinary approach. The team of providers may include:

- A medical provider (primary care provider, gynecologist, or sexual health specialist) to coordinate care and manage biological factors contributing to sexual dysfunction

- A physical therapist with expertise in treating pelvic floor disorders

- A psychologist to address psychological, relational, and sociocultural contributors to sexual dysfunction

- A sex therapist (womenshealthapta.org, aasect.org) to facilitate treatment of tight, tender pelvic floor muscles through education and guidance about kinesthetic awareness, muscle relaxation, and dilator therapy.33

Even in the initial visit, the primary care provider can educate, reassure regarding normal sexual function, and treat conditions such as genitourinary syndrome of menopause and antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. The PLISSIT model (Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy) is a useful tool for initiating counseling about sexual health (Table 4).34

AGING VS MENOPAUSE

Aging can affect sexual function in both men and women. About 40% of women experience changes in sexual function around the menopausal transition, with common complaints being loss of sexual responsiveness and desire, sexual pain, decreased sexual activity, and partner sexual dysfunction.35 However, studies seem to show that while menopause results in hormonal changes that affect sexual function, other factors may have a greater impact.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation36 found vaginal and pelvic pain and decreased sexual desire were associated with the menopausal transition, but other sexual health outcomes (frequency of sexual activities, arousal, importance of sex, emotional satisfaction, or physical pleasure) were not. Physical and psychological health, marital status, and a change in relationship were all associated with differences in sexual health.

The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study II37 found a greater association between physical and mental health, relationship status, and smoking and women’s sexual functioning than menopausal status.

The Penn Ovarian Aging Study38 found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction included postmenopausal status, anxiety, and absence of a sexual partner.

The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project39 also found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Sexual dysfunction with distress was associated with relationship factors and depression.37

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause and its treatment

As the ovaries shut down during menopause, estradiol levels decrease. Nearly 50% of women experience symptoms related to genitourinary syndrome of menopause (formerly called atrophic vaginitis or vulvovaginal atrophy).40,41 These symptoms include vaginal dryness and discomfort or pain with sexual activity, but menopausal hormone loss can also result in reduced genital blood flow, decreased sensory perception, and decreased sexual responsiveness.22

Estrogen is the most effective treatment for genitourinary syndrome of menopause, with low-dose vaginal preparations preferred over systemic ones for isolated vulvar and vaginal symptoms.40 While estrogen is effective for vaginal dryness and sexual pain associated with estrogen loss, replacing estrogen systemically has not been associated with improvements in sexual desire.42

DEPRESSION AND ANTIDEPRESSANT-INDUCED SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION

Depression increases the risk of sexual dysfunction, and vice versa.

A meta-analysis that included 12 studies involving almost 15,000 patients confirmed that depression increased the risk of sexual dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction increased the risk of depression.43 This interaction may be related to the overlap in affected neurotransmitters and neuroendocrine systems.44

In the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression trial, Ishak et al45 found that patients treated with a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) who experienced remission of depression had a lower prevalence of impaired sexual satisfaction and much greater improvements in sexual satisfaction than did those who remained depressed. The severity of depressive symptoms predicted impairment in sexual satisfaction, which in turn predicted poorer quality of life. The authors suggested that physicians encourage patients to remain on SSRI treatment, given that improvement in depressive symptoms is likely to improve sexual satisfaction.

Antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction

As many as 70% of patients taking an SSRI or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) experience antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, though this is difficult to estimate across studies of different medications due to differences in methods and because many patients only report it when directly asked about it.46

Treatment of antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction includes not only optimal management of depression but reassessment of the antidepressant treatment. If using only nondrug treatments for the mood disorder is not feasible, switching to (or ideally, starting with) an antidepressant with fewer sexual side effects such as mirtazapine, vilazodone, or bupropion is an option.46

A drug holiday (suspending antidepressant treatment for 1 or 2 days) has been suggested as a means of treating antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, but this may result in poorer control of depressive symptoms and discontinuation symptoms, and it encourages medication noncompliance.46,47

Treatment with a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (eg, sildenafil) has been studied in women with antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction, with modest results.48

A Cochrane review reported that treatment with bupropion shows promise at higher doses (300 mg daily).49

Exercise for 20 minutes 3 times weekly is associated with improvement in antidepressant-induced sexual dysfunction when the exercise is performed immediately before sexual activity.50

LOW SEXUAL DESIRE

Hypoactive sexual desire disorder is defined as persistent or recurrent deficiency or absence of sexual fantasies and desire for sexual activity associated with marked distress and not due exclusively to a medication, substance abuse, or a medical condition.

Low or decreased sexual desire is the most commonly reported sexual health concern in women of all ages, with an unadjusted prevalence of 39.7%. When the criterion of personal distress is included, the prevalence is 8.9% in women ages 18 to 44, 12.3% in women ages 45 to 64, and 7.4% in women ages 65 and older.1

Multiple biological, psychological, and social factors may contribute to the problem. Identifying the ones that are present can help in planning treatment. A multifaceted approach may be appropriate.

Mindfulness and cognitive behavioral therapy for low sexual desire

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy is designed to improve awareness, focusing on and accepting the present moment, and directing attention away from and lessening self-criticism and evaluation of one’s sexual responsiveness.

Mindfulness-based therapy has been associated with improvements in sexual desire and associated distress.51 Similarly, the effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy for treating hypoactive sexual desire disorder is supported by 3 controlled trials, although concerns exist about the adequacy of these trials, and further study is needed.52

Androgen therapy in women

In randomized controlled trials in women with low sexual desire who were either naturally or surgically menopausal, sexual function improved with testosterone therapy that resulted in mostly supraphysiologic total testosterone levels (which may not reflect free testosterone levels) with or without concurrent estrogen treatment.53–57

Testosterone is not approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in women, primarily because of the lack of long-term safety and efficacy data (ie, beyond 24 months). However, studies have shown no evidence of increased risk of endometrial cancer or cardiovascular disease with testosterone dosed to achieve physiologic premenopausal levels.58 Data on breast cancer risk are less clear, but observational studies over the last decade do not support an association with testosterone use in women.58 There is no clearly defined androgen deficiency syndrome in women, and androgen levels do not reliably correlate with symptoms.59

The Endocrine Society59 guidelines endorse the use of testosterone in postmenopausal women with hypoactive sexual desire disorder. They say to aim for the midnormal premenopausal range and suggest discontinuing the drug if there is no response in 6 months. They recommend checking testosterone levels at baseline, after 3 to 6 weeks of therapy, and every 6 months to monitor for excessive use, to avoid supraphysiologic dosing and to evaluate for signs of androgen excess (eg, acne, hair growth). The use of products formulated for men or those formulated by pharmacies is discouraged; however, no FDA-approved products are currently available for use in women in the United States.

Flibanserin

A postsynaptic serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist and 5-HT2A receptor agonist, flibanserin was approved by the FDA in 2015 for treatment of hypoactive sexual desire disorder in premenopausal women. Its mechanism of action is likely through an effect on neurotransmitters that suppresses serotonin (which has sexually inhibitory effects) and promotes dopamine and norepinephrine (which have excitatory effects).60

The efficacy of flibanserin has been demonstrated in 3 randomized controlled trials, with significant increases in the number of sexually satisfying events and in sexual desire scores and a decrease in distress associated with low sexual desire.17–19 While the increase in sexually satisfying events was modest (about 1 extra event per month), some have suggested that the frequency of sexual activity may not be the best measure of sexual function in women.61 Further, responders to this drug showed a return to near-normal premenopausal frequencies of sexual activity in a separate analysis.61

The drug is generally well tolerated, with common adverse effects being somnolence, dizziness, and fatigue.18,19 Flibanserin has been associated with orthostatic hypotension with alcohol use and carries a boxed warning highlighting this potential interaction.62 Use of this drug is contraindicated in women who drink alcohol or take medications that are moderate or strong inhibitors of CYP-3A4 (eg, some antiretroviral drugs, antihypertensive drugs, antibiotics, and fluconazole, which can increase systemic exposure to flibanserin and potential side effects), and in those with liver impairment.

SEXUAL AROUSAL DISORDERS

Female sexual arousal disorder is the persistent or recurrent inability to attain or maintain an adequate lubrication-swelling response of sexual excitement. Sexual arousal results from a complex interaction between genital response, central nervous system activity, and information processing of the sexual stimulus. Difficulty with sexual arousal can result from neurovascular or neuroendocrine dysfunction or impaired central nervous system processing.

Women may experience a mismatch between subjective and objective genital arousal. A subjective report of decreased genital arousal may not be confirmed with measurement of vaginal pulse amplitude by photoplethysmography.63 Even in postmenopausal women, in the absence of significant neurovascular or neuroendocrine dysfunction, it is likely that either contextual or relational variables resulting in inadequate sexual stimulation or cognitive inhibition are more important factors contributing to difficulty with sexual arousal.63

Although there are no standard recommendations for evaluation of arousal disorders and advanced testing is often unnecessary, nerve function can be assessed with genital sensory testing utilizing thermal and vibratory threshholds64; vaginal blood flow can be assessed with vaginal photoplethysmography63; and imaging of the spine and pelvis can help to rule out neurovascular pathology.

Treatment of arousal disorders

As with other forms of female sexual dysfunction, treatment of arousal disorders includes addressing contributing factors.

Although there are few data from randomized controlled trials, psychological treatments such as sensate focus exercises and masturbation training have been suggested, centered on women becoming more self-focused and assertive.31 Sensate focus exercises are a series of graded, nondemand, sensual touching exercises aimed at reducing anxiety and avoidance of sexual activity, and improving sexual communication and intimacy by the gradual reintroduction of sexual activity.65 More recently, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy has been associated with improvements in sexual arousal as well as other parameters of sexual function.51

Currently, no pharmacologic treatments are recommended for arousal disorders because of a lack of evidence of efficacy and because of adverse effects.31

ORGASMIC DISORDER

Female orgasmic disorder is the marked delay, marked infrequency, or absence of orgasm, or markedly reduced intensity of orgasm.

Important considerations in evaluating orgasm disorders include psychosocial factors (eg, lack of sex education, negative feelings about sex, religiosity), psychological factors (eg, anxiety, depression, body image concerns), relational factors (eg, communication issues, lack of emotional intimacy, partner sexual dysfunction), adverse childhood or adult experiences (eg, physical, sexual, or emotional or verbal abuse), medical history (pelvic surgery, neurologic, or vascular disease) and medications (eg, SSRIs, SNRIs, and antipsychotic medications).66

Treatment of orgasmic disorder

Involving the partner in treatment is important, particularly if the difficulty with orgasm is acquired and only occurs with sex with a partner. Using the PLISSIT model to provide targeted, office-based interventions can be helpful.

Behavioral therapies such as directed masturbation, sensate focus exercises, or a combination of these have been shown to be effective, as has coital alignment during intercourse (positioning of male partner with his pelvis above the pubic bone of his partner to maximize clitoral stimulation with penile penetration).66

Hormonal therapy may be useful in postmenopausal women. However, there are no data on it for women whose primary complaint is female orgasmic disorder, and further study is needed.66

SEXUAL PAIN DISORDERS

The DSM-5 describes genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder as fear or anxiety, marked tightening or tensing of abdominal and pelvic muscles, or actual pain with vaginal penetration that is recurrent or persistent for a minimum of 6 months.14 Pain may occur with initial penetration, with deeper thrusting, or both.

Although the DSM-5 definition focuses on pain with penetration, it is important to recognize and ask about noncoital sexual pain. Women may also present with persistent vulvar pain or pain at the vulvar vestibule with provocation, (eg, sexual activity, tampon insertion, sitting), also known as provoked vestibulodynia.

Assessment of vaginal and vulvar pain includes a directed history and physical examination aimed at identifying potential etiologies or contributing factors, including infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, neurologic, traumatic, iatrogenic, or factors related to hormonal deficiency.67

Treatment of sexual pain

Removal of offending agents is a first step. This includes a thorough review of vulvar and vaginal hygiene practices and emphasis on avoiding the use of any product containing potential irritants (eg, soaps or detergents containing perfumes or dyes) and using lubricants and moisturizers without gimmicks (no warming or tingling agents or flavors). Oral contraceptives have been associated with vestibulodynia, and women in whom the sexual pain started when they started an oral contraceptive may benefit from switching to an alternate form of contraception.68

Dysfunction of pelvic floor muscles may result in sexual pain and may be a primary problem or a secondary complication related to other issues such as symptomatic genitourinary syndrome of menopause. The symptoms of nonrelaxing pelvic floor dysfunction (also known as hypertonic pelvic floor dysfunction or pelvic floor tension myalgia) include pain in the pelvis with sexual activity that may linger for hours or even days, and may also include bowel and bladder dysfunction and low back pain or hip pain radiating to the thighs or groin.33 Physical therapy under the care of a physical therapist with expertise in the management of pelvic floor disorders is the cornerstone of treatment for this condition.33

Treatment of the genital and urinary symptoms related to loss of estrogen after menopause (genitourinary syndrome of menopause) includes the use of vaginal lubricants with sexual activity and vaginal moisturizers on a regular basis (2 to 5 times per week).40 Low-dose vaginal estrogen creams, rings, or tablets and the oral selective estrogen receptor antagonist ospemifene are recommended for moderate to severe symptoms of genitourinary syndrome of menopause.40 Intravaginal dehydroepiandrosterone was recently approved by the FDA for treatment of dyspareunia associated with menopause.69 Topical lidocaine applied to the introitus before sexual activity has been found to be effective for reducing sexual pain in women with breast cancer, and when used in combination with vaginal lubricants and moisturizers is a practical option for women, particularly those unable to use estrogen-based therapies.70

Many women experience some form of sexual dysfunction, be it lack of desire, lack of arousal, failure to achieve orgasm, or pain during sexual activity.

Sexual health may be difficult to discuss, for both the patient and the provider. Here, we describe how primary care physicians can approach this topic, assess potential problems, and begin treatment.

A COMMON PROBLEM

The age-adjusted prevalence of sexual dysfunction in US women was reported at 44% in the Prevalence of Female Sexual Problems Associated With Distress and Determinants of Treatment Seeking (PRESIDE) study,1 but the prevalence of distress associated with sexual dysfunction was 12%. The most common type of sexual dysfunction reported by women was low sexual desire, a finding consistent with that of another large population-based study.2

While the prevalence of any type of sexual dysfunction was highest in women over age 65,1 the prevalence of distress was lowest in this age group and highest in midlife between the ages of 45 and 65. The diagnostic criteria require both a problem and distress over the problem.

Sexual dysfunction negatively affects quality of life and emotional health, regardless of age.3

LIFESTYLE AND SEXUAL FUNCTION

Various lifestyle factors have been linked to either more or less sexual activity. For example, a Mediterranean diet was associated with increased sexual activity, as were social activity, social support, psychological well-being, self-reported good quality of life, moderate alcohol intake, absence of tobacco use, a normal body mass index, and exercise.4–6 A higher sense of purpose in life has been associated with greater sexual enjoyment.7

Conversely, sexual inactivity has been associated with alcohol misuse, an elevated body mass index, and somatization.4–6

SEXUAL RESPONSE: LINEAR OR CIRCULAR?

Masters and Johnson8 initially proposed a linear model of human sexual response, which Kaplan later modified to include desire and applied to both men and women.9,10 This model presumed that sexual response begins with spontaneous sexual desire, followed by arousal, and then (sometimes) orgasm and resolution.

In 2000, Basson11 proposed a circular, intimacy-based model of sexual response in women that acknowledged the complexities involved in a woman’s motivation to be sexual (Figure 1). While a woman may enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, she may also enter it as sexually neutral, with arousal in response to a sexual stimulus. Emotional intimacy is an important part of the cycle, and emotional closeness and bonding with the partner may provide motivation for a woman to enter into the cycle again in the future.

In a Danish survey,12 more people of both sexes said the 2 linear models described their experiences better than the circular model, but more women than men endorsed the circular model, and more men than women endorsed a linear model.

In evaluating women who complain of low sexual desire, clinicians should be aware that women, particularly those who are postmenopausal, may not enter the cycle with spontaneous sexual desire, but instead may experience arousal in response to a sexual stimulus followed by desire—ie, responsive rather than spontaneous sexual desire. Sexual arousal may precede desire, especially for women in long-term relationships, and emotional intimacy is a key driver for sexual engagement in women.11

CATEGORIES OF SEXUAL DYSFUNCTION IN WOMEN

The World Health Organization defines sexual health as “a state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being in relation to sexuality” and “not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction, or infirmity.”13

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),14 published in 2013, defines three categories of sexual dysfunction in women:

- Female sexual interest and arousal disorder

- Female sexual orgasmic disorder

- Genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.

To meet the diagnosis of any of these, symptoms must:

- Persist for at least 6 months

- Occur in 75% to 100% of sexual encounters

- Be accompanied by personal distress

- Not be related to another psychological or medical condition, medication or substance use, or relationship distress.

Sexual problems may be lifelong or acquired after a period of normal functioning, and may be situational (present only in certain situations) or generalized (present in all situations).

Female sexual interest and arousal disorder used to be 2 separate categories in earlier editions of the DSM. Proponents of merging the 2 categories in DSM-5 cited several reasons, including difficulty in clearly distinguishing desire from other motivations for sexual activity, the relatively low reporting of fantasy in women, the complexity of distinguishing spontaneous from responsive desire, and the common co-occurrence of decreased desire and arousal difficulties.15

Other experts, however, have recommended keeping the old, separate categories of hypoactive sexual desire disorder and arousal disorder.16 The recommendation to preserve the diagnostic category of hypoactive sexual desire disorder is based on robust observational and registry data, as well as the results of randomized controlled trials that used the old criteria for hypoactive sexual desire disorder to assess responses to pharmacologic treatment of this condition.17–19 In addition, this classification as a separate and distinct diagnosis is consistent with the nomenclature used in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision and was endorsed by the International Consultation on Sexual Medicine in 2015.16

HOW TO ASK ABOUT SEXUAL HEALTH

Assessment of sexual health concerns should be a part of a routine health examination, particularly after childbirth and other major medical, surgical, psychological, and life events. Women are unlikely to bring up sexual health concerns with their healthcare providers, but instead hope that their providers will bring up the topic.20

Barriers to the discussion include lack of provider education and training, patient and provider discomfort, perceived lack of time during an office visit, and lack of approved treatments.21,22 Additionally, older women are less likely than men to discuss sexual health with their providers.23 Other potential barriers to communication include negative societal attitudes about sexuality in women and in older individuals.24,25 To overcome these barriers:

Legitimize sexual health as an important health concern and normalize its discussion as part of a routine clinical health assessment. Prefacing a query about sexual health with a normalizing and universalizing statement can help: eg, “Many women going through menopause have concerns about their sexual health. Do you have any sexual problems or concerns?” Table 1 contains examples of questions to use for initial screening for sexual dysfunction.22,26

Flynn et al27 proposed a validated single-question checklist to screen for sexual dysfunction that is an efficient way to identify specific sexual concerns, guide selection of interventions, and facilitate patient-provider communication (Table 2).

Don’t judge and don’t make assumptions about sexuality and sexual practices.

Assure confidentiality.

Use simple, direct language that is appropriate for the patient’s age, ethnicity, culture, and level of health literacy.3

Take a thorough history (sexual and reproductive, medical-surgical, and psychosocial).

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Perform a focused physical examination to evaluate for potential causes of pain (eg, infectious causes, vulvar dermatoses, pelvic floor muscle dysfunction). The examination is also an opportunity to teach the patient about anatomy and normal sexual function.

No standard laboratory tests or imaging studies are required for the assessment of sexual dysfunction.28

IT’S NOT JUST PHYSICAL

Evaluation and treatment of female sexual dysfunction is guided by the biopsychosocial model, with potential influences from the biological, psychological, sociocultural, and interpersonal realms (Table 3).29,30

Biological factors include pelvic surgery, cancer and its treatment, neurologic diseases, and vascular diseases. Medications, including antidepressants, narcotics, anticholinergics, antihistamines, antihypertensives, oral contraceptives, and antiestrogens may also adversely affect sexual response.26

Psychological factors include a history of sexual abuse or trauma, body image concerns, distraction, stress, anxiety, depression, and personality disorders.22

Sociocultural factors include lack of sex education, unrealistic expectations, cultural norms, and religious influences.

Relationship factors include conflict with one’s partner, lack of emotional intimacy, absence of a partner, and partner sexual dysfunction. While there appears to be a close link between sexual satisfaction and a woman’s relationship with her partner in correlational studies and in clinical experience, there has been little research about relationship factors and their contribution to desire and arousal concerns.31 Sexual dysfunction in one’s partner (eg, erectile dysfunction) has been shown to negatively affect the female partner’s sexual desire.32

GENERAL APPROACH TO TREATMENT

In treating sexual health problems in women, we address contributing factors identified during the initial assessment.

A multidisciplinary approach

As sexual dysfunction in women is often multifactorial, management of the problem is well suited to a multidisciplinary approach. The team of providers may include:

- A medical provider (primary care provider, gynecologist, or sexual health specialist) to coordinate care and manage biological factors contributing to sexual dysfunction

- A physical therapist with expertise in treating pelvic floor disorders

- A psychologist to address psychological, relational, and sociocultural contributors to sexual dysfunction

- A sex therapist (womenshealthapta.org, aasect.org) to facilitate treatment of tight, tender pelvic floor muscles through education and guidance about kinesthetic awareness, muscle relaxation, and dilator therapy.33

Even in the initial visit, the primary care provider can educate, reassure regarding normal sexual function, and treat conditions such as genitourinary syndrome of menopause and antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction. The PLISSIT model (Permission, Limited Information, Specific Suggestions, and Intensive Therapy) is a useful tool for initiating counseling about sexual health (Table 4).34

AGING VS MENOPAUSE

Aging can affect sexual function in both men and women. About 40% of women experience changes in sexual function around the menopausal transition, with common complaints being loss of sexual responsiveness and desire, sexual pain, decreased sexual activity, and partner sexual dysfunction.35 However, studies seem to show that while menopause results in hormonal changes that affect sexual function, other factors may have a greater impact.

The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation36 found vaginal and pelvic pain and decreased sexual desire were associated with the menopausal transition, but other sexual health outcomes (frequency of sexual activities, arousal, importance of sex, emotional satisfaction, or physical pleasure) were not. Physical and psychological health, marital status, and a change in relationship were all associated with differences in sexual health.

The Massachusetts Women’s Health Study II37 found a greater association between physical and mental health, relationship status, and smoking and women’s sexual functioning than menopausal status.

The Penn Ovarian Aging Study38 found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Risk factors for sexual dysfunction included postmenopausal status, anxiety, and absence of a sexual partner.

The Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project39 also found that sexual function declined across the menopausal transition. Sexual dysfunction with distress was associated with relationship factors and depression.37

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause and its treatment