User login

‘Joker’ filled with mental illness misconceptions

The Batman characters have been cultural icons for generations – spanning more than three-quarters of a century. How many of us had Batman (or the Joker) on our school lunch box or watched reruns of Adam West’s campy televised rendition of Batman? The October release of “Joker” has been breaking contemporary box office records.

(Spoiler alert!) The Todd Phillips film associates mental illness with violent acts, spurring a slew of articles explaining that this association is uncommon and may promote stigmatization and public fear of people with obvious symptoms of mental illness. The protagonist, Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), suffers from a condition in which his affect and facial expressions are not appropriate to his emotions or to the situation. He laughs uncontrollably when a situation is sad or upsetting. Sometimes he laughs and cries at the same time. As a result, he often is misunderstood, ridiculed, and victimized – like many people with obvious mental illness.

Arthur Fleck is a loner who has difficulty with relationships and self-esteem, and is beaten severely while at work as a clown. Shortly after the incident, he is given a gun by one of his coworkers. He keeps it with him even when working as a clown in a children’s hospital – where it is accidentally revealed, and he is subsequently fired. Still in his clown garb, he later uses the gun when he is mocked and assaulted on the subway by three Gotham City bankers.

In an unusual tone, his mental health worker reminds him early in the film that he is prescribed seven different psychotropic medications, helping to cement for the viewer that mental illness is the cause of Arthur’s problems and the Joker’s origin story. Then the funding for Arthur’s mental health treatment (even if it was not good treatment) was cut – a problem not just in Gotham.

While some of Arthur Fleck’s symptoms are consistent with real mental illness, the combination of symptoms is unusual. Although he is being treated with a variety of medications, it is unclear whether any of them are helping him or what exactly they are helping him with. (Ironically, once he is off of his medications, he becomes a better dresser and a better dancer.) He writes in a disorganized way in his journal; the only intelligible sentence that is focused on is, “The worst part about having mental illness is people expect you to behave as if you DONT.” A smiley face in the ‘O’ suggests that his affect is inappropriate even in his writing. Arthur’s condition of uncontrollable laughing and/or crying, associated with head trauma, appears more consistent with the neurologic condition pseudobulbar affect rather than a mental illness. In addition to pseudobulbar affect, Arthur demonstrates a constellation of symptoms of different kinds of mental illness, including erotomanic delusions, ideas of reference, and disorganized thinking. He also does not appear to take social cues, such as knowing when he is being mocked. He appears to believe that his neighbor is his girlfriend (as the viewer was similarly led to believe), eventually breaking into her apartment where he thought he belonged, much to her horror when she finds him there. Some of his symptoms may run in his family (whether it be his biological or adoptive family).

Penny (Arthur’s mother) strongly believes (perhaps a delusion, perhaps not) that her previous employer Thomas Wayne (the future Batman’s father) is the father of her love-child, Arthur. When Arthur obtains Penny’s mental health records (through his own violent devices), he finds that she had been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder and a psychotic disorder. She had been found guilty of endangering the welfare of her (perhaps adopted, perhaps not) child Arthur, who had been malnourished, with severe head trauma, and tied to a radiator.

Arthur’s smothering of his mother with a pillow in her hospital bed, after he was devastated by both her stroke and this newfound data, occurred in a perfect storm. The killing is not portrayed as an act of euthanasia. We know that schizophrenia is overrepresented among matricide perpetrators and that long-term dysfunctional relationships between mother and (grown) child usually precede matricides. Mothers are often seen as controlling, fathers are often absent (as in Arthur’s case), and the child is often overly dependent. The mother and child (as seen here) often have a relationship marked by love and hate – mutual dependence and hostility. But Arthur is not the only character in the Batman universe to commit matricide. Recall that the Batman’s psychiatrist Amadeus Arkham himself killed his own mentally ill mother during his young adulthood.

Pop culture can give the public negative impressions of mental illness. While filmmakers need not portray actual mental illnesses or their symptoms in moving their stories forward, their portrayals have an impact on what the public sees as mental illness. This is similar to the current American president and others in political power asserting that mental illness causes mass shootings, and those in the public taking their word for it rather than the word of psychiatry.

In actuality, what felt the most true to life in the film was the early scene in which Arthur was seriously assaulted while waving the going-out-of-business sign on the sidewalk, just trying to make a living. As psychiatrists know, people with mental illness are more likely to be victimized by others in society than to be perpetrators of violence. To be sure, some of Arthur’s characteristics are dynamic risk factors, such as his unemployment and social isolation. However, society often conflates mental illness with dangerousness, but most people with mental illness are not violent.

In the final scenes, Arthur Fleck (who is now the Joker) is apparently back in the white-walled Arkham State Hospital, with an implication that he has gotten away with the murders, either found incompetent or insane. This, too, has negative implications for the public viewing the film – and further perpetuates the misunderstanding that people with mental illness “get away” with their crimes. In reality, depending on the study, approximately one-quarter of those who pleaded insanity were found insane, and those facing jury trials (and public perception) are less likely to be found insane than those with bench trials. Public misinterpretations and outrage over the idea that a mentally unwell person might be found insane rather than guilty have existed for centuries, perhaps most memorably when John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate former President Ronald Reagan, after identifying with a character in the film “Taxi Driver.” Let’s presume that Gotham has an insanity defense similar to other places in America. Then, in order to be found insane, Arthur’s pseudobulbar affect or his (unclear) mental illness would have either caused him not to know the nature and consequences of his acts, and/or to appreciate the wrongfulness of his acts (if we are fairly certain that Gotham is actually New York City). Neither of these appear to be true from the film. He knew that he was killing. No delusions or hallucinations made him think his acts were not wrong. Rather, he had an arguably rational motive – certainly the multitudes wearing clown masks in the subsequent uprisings against the powerful also believed his motive to be rational. He deliberately killed the bankers who mocked and beat him. He was also able to defer his killings until what he calculated was the right time to have the most impact – for example, on live television, or when he was alone with his mother in the hospital.

In closing, unrealistic portrayals of the link between mental illness, violence, and forensic hospitalization are seen on the silver screen in “Joker.” We hope that others who feign mental illness symptoms to evade criminal responsibility will emulate Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker as it will make it much easier for forensic psychiatrists to ferret out malingerers!

Dr. Hatters Friedman serves as the Phillip Resnick Professor of Forensic Psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. She is also editor of Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate (Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing [2019]), which was written by the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Committee on Psychiatry & Law. Dr. Rosenbaum is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in private practice in New York. She is an assistant clinical professor at New York University Langone Medical Center and on the faculty at Weill-Cornell Medical Center.

The Batman characters have been cultural icons for generations – spanning more than three-quarters of a century. How many of us had Batman (or the Joker) on our school lunch box or watched reruns of Adam West’s campy televised rendition of Batman? The October release of “Joker” has been breaking contemporary box office records.

(Spoiler alert!) The Todd Phillips film associates mental illness with violent acts, spurring a slew of articles explaining that this association is uncommon and may promote stigmatization and public fear of people with obvious symptoms of mental illness. The protagonist, Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), suffers from a condition in which his affect and facial expressions are not appropriate to his emotions or to the situation. He laughs uncontrollably when a situation is sad or upsetting. Sometimes he laughs and cries at the same time. As a result, he often is misunderstood, ridiculed, and victimized – like many people with obvious mental illness.

Arthur Fleck is a loner who has difficulty with relationships and self-esteem, and is beaten severely while at work as a clown. Shortly after the incident, he is given a gun by one of his coworkers. He keeps it with him even when working as a clown in a children’s hospital – where it is accidentally revealed, and he is subsequently fired. Still in his clown garb, he later uses the gun when he is mocked and assaulted on the subway by three Gotham City bankers.

In an unusual tone, his mental health worker reminds him early in the film that he is prescribed seven different psychotropic medications, helping to cement for the viewer that mental illness is the cause of Arthur’s problems and the Joker’s origin story. Then the funding for Arthur’s mental health treatment (even if it was not good treatment) was cut – a problem not just in Gotham.

While some of Arthur Fleck’s symptoms are consistent with real mental illness, the combination of symptoms is unusual. Although he is being treated with a variety of medications, it is unclear whether any of them are helping him or what exactly they are helping him with. (Ironically, once he is off of his medications, he becomes a better dresser and a better dancer.) He writes in a disorganized way in his journal; the only intelligible sentence that is focused on is, “The worst part about having mental illness is people expect you to behave as if you DONT.” A smiley face in the ‘O’ suggests that his affect is inappropriate even in his writing. Arthur’s condition of uncontrollable laughing and/or crying, associated with head trauma, appears more consistent with the neurologic condition pseudobulbar affect rather than a mental illness. In addition to pseudobulbar affect, Arthur demonstrates a constellation of symptoms of different kinds of mental illness, including erotomanic delusions, ideas of reference, and disorganized thinking. He also does not appear to take social cues, such as knowing when he is being mocked. He appears to believe that his neighbor is his girlfriend (as the viewer was similarly led to believe), eventually breaking into her apartment where he thought he belonged, much to her horror when she finds him there. Some of his symptoms may run in his family (whether it be his biological or adoptive family).

Penny (Arthur’s mother) strongly believes (perhaps a delusion, perhaps not) that her previous employer Thomas Wayne (the future Batman’s father) is the father of her love-child, Arthur. When Arthur obtains Penny’s mental health records (through his own violent devices), he finds that she had been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder and a psychotic disorder. She had been found guilty of endangering the welfare of her (perhaps adopted, perhaps not) child Arthur, who had been malnourished, with severe head trauma, and tied to a radiator.

Arthur’s smothering of his mother with a pillow in her hospital bed, after he was devastated by both her stroke and this newfound data, occurred in a perfect storm. The killing is not portrayed as an act of euthanasia. We know that schizophrenia is overrepresented among matricide perpetrators and that long-term dysfunctional relationships between mother and (grown) child usually precede matricides. Mothers are often seen as controlling, fathers are often absent (as in Arthur’s case), and the child is often overly dependent. The mother and child (as seen here) often have a relationship marked by love and hate – mutual dependence and hostility. But Arthur is not the only character in the Batman universe to commit matricide. Recall that the Batman’s psychiatrist Amadeus Arkham himself killed his own mentally ill mother during his young adulthood.

Pop culture can give the public negative impressions of mental illness. While filmmakers need not portray actual mental illnesses or their symptoms in moving their stories forward, their portrayals have an impact on what the public sees as mental illness. This is similar to the current American president and others in political power asserting that mental illness causes mass shootings, and those in the public taking their word for it rather than the word of psychiatry.

In actuality, what felt the most true to life in the film was the early scene in which Arthur was seriously assaulted while waving the going-out-of-business sign on the sidewalk, just trying to make a living. As psychiatrists know, people with mental illness are more likely to be victimized by others in society than to be perpetrators of violence. To be sure, some of Arthur’s characteristics are dynamic risk factors, such as his unemployment and social isolation. However, society often conflates mental illness with dangerousness, but most people with mental illness are not violent.

In the final scenes, Arthur Fleck (who is now the Joker) is apparently back in the white-walled Arkham State Hospital, with an implication that he has gotten away with the murders, either found incompetent or insane. This, too, has negative implications for the public viewing the film – and further perpetuates the misunderstanding that people with mental illness “get away” with their crimes. In reality, depending on the study, approximately one-quarter of those who pleaded insanity were found insane, and those facing jury trials (and public perception) are less likely to be found insane than those with bench trials. Public misinterpretations and outrage over the idea that a mentally unwell person might be found insane rather than guilty have existed for centuries, perhaps most memorably when John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate former President Ronald Reagan, after identifying with a character in the film “Taxi Driver.” Let’s presume that Gotham has an insanity defense similar to other places in America. Then, in order to be found insane, Arthur’s pseudobulbar affect or his (unclear) mental illness would have either caused him not to know the nature and consequences of his acts, and/or to appreciate the wrongfulness of his acts (if we are fairly certain that Gotham is actually New York City). Neither of these appear to be true from the film. He knew that he was killing. No delusions or hallucinations made him think his acts were not wrong. Rather, he had an arguably rational motive – certainly the multitudes wearing clown masks in the subsequent uprisings against the powerful also believed his motive to be rational. He deliberately killed the bankers who mocked and beat him. He was also able to defer his killings until what he calculated was the right time to have the most impact – for example, on live television, or when he was alone with his mother in the hospital.

In closing, unrealistic portrayals of the link between mental illness, violence, and forensic hospitalization are seen on the silver screen in “Joker.” We hope that others who feign mental illness symptoms to evade criminal responsibility will emulate Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker as it will make it much easier for forensic psychiatrists to ferret out malingerers!

Dr. Hatters Friedman serves as the Phillip Resnick Professor of Forensic Psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. She is also editor of Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate (Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing [2019]), which was written by the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Committee on Psychiatry & Law. Dr. Rosenbaum is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in private practice in New York. She is an assistant clinical professor at New York University Langone Medical Center and on the faculty at Weill-Cornell Medical Center.

The Batman characters have been cultural icons for generations – spanning more than three-quarters of a century. How many of us had Batman (or the Joker) on our school lunch box or watched reruns of Adam West’s campy televised rendition of Batman? The October release of “Joker” has been breaking contemporary box office records.

(Spoiler alert!) The Todd Phillips film associates mental illness with violent acts, spurring a slew of articles explaining that this association is uncommon and may promote stigmatization and public fear of people with obvious symptoms of mental illness. The protagonist, Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix), suffers from a condition in which his affect and facial expressions are not appropriate to his emotions or to the situation. He laughs uncontrollably when a situation is sad or upsetting. Sometimes he laughs and cries at the same time. As a result, he often is misunderstood, ridiculed, and victimized – like many people with obvious mental illness.

Arthur Fleck is a loner who has difficulty with relationships and self-esteem, and is beaten severely while at work as a clown. Shortly after the incident, he is given a gun by one of his coworkers. He keeps it with him even when working as a clown in a children’s hospital – where it is accidentally revealed, and he is subsequently fired. Still in his clown garb, he later uses the gun when he is mocked and assaulted on the subway by three Gotham City bankers.

In an unusual tone, his mental health worker reminds him early in the film that he is prescribed seven different psychotropic medications, helping to cement for the viewer that mental illness is the cause of Arthur’s problems and the Joker’s origin story. Then the funding for Arthur’s mental health treatment (even if it was not good treatment) was cut – a problem not just in Gotham.

While some of Arthur Fleck’s symptoms are consistent with real mental illness, the combination of symptoms is unusual. Although he is being treated with a variety of medications, it is unclear whether any of them are helping him or what exactly they are helping him with. (Ironically, once he is off of his medications, he becomes a better dresser and a better dancer.) He writes in a disorganized way in his journal; the only intelligible sentence that is focused on is, “The worst part about having mental illness is people expect you to behave as if you DONT.” A smiley face in the ‘O’ suggests that his affect is inappropriate even in his writing. Arthur’s condition of uncontrollable laughing and/or crying, associated with head trauma, appears more consistent with the neurologic condition pseudobulbar affect rather than a mental illness. In addition to pseudobulbar affect, Arthur demonstrates a constellation of symptoms of different kinds of mental illness, including erotomanic delusions, ideas of reference, and disorganized thinking. He also does not appear to take social cues, such as knowing when he is being mocked. He appears to believe that his neighbor is his girlfriend (as the viewer was similarly led to believe), eventually breaking into her apartment where he thought he belonged, much to her horror when she finds him there. Some of his symptoms may run in his family (whether it be his biological or adoptive family).

Penny (Arthur’s mother) strongly believes (perhaps a delusion, perhaps not) that her previous employer Thomas Wayne (the future Batman’s father) is the father of her love-child, Arthur. When Arthur obtains Penny’s mental health records (through his own violent devices), he finds that she had been diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder and a psychotic disorder. She had been found guilty of endangering the welfare of her (perhaps adopted, perhaps not) child Arthur, who had been malnourished, with severe head trauma, and tied to a radiator.

Arthur’s smothering of his mother with a pillow in her hospital bed, after he was devastated by both her stroke and this newfound data, occurred in a perfect storm. The killing is not portrayed as an act of euthanasia. We know that schizophrenia is overrepresented among matricide perpetrators and that long-term dysfunctional relationships between mother and (grown) child usually precede matricides. Mothers are often seen as controlling, fathers are often absent (as in Arthur’s case), and the child is often overly dependent. The mother and child (as seen here) often have a relationship marked by love and hate – mutual dependence and hostility. But Arthur is not the only character in the Batman universe to commit matricide. Recall that the Batman’s psychiatrist Amadeus Arkham himself killed his own mentally ill mother during his young adulthood.

Pop culture can give the public negative impressions of mental illness. While filmmakers need not portray actual mental illnesses or their symptoms in moving their stories forward, their portrayals have an impact on what the public sees as mental illness. This is similar to the current American president and others in political power asserting that mental illness causes mass shootings, and those in the public taking their word for it rather than the word of psychiatry.

In actuality, what felt the most true to life in the film was the early scene in which Arthur was seriously assaulted while waving the going-out-of-business sign on the sidewalk, just trying to make a living. As psychiatrists know, people with mental illness are more likely to be victimized by others in society than to be perpetrators of violence. To be sure, some of Arthur’s characteristics are dynamic risk factors, such as his unemployment and social isolation. However, society often conflates mental illness with dangerousness, but most people with mental illness are not violent.

In the final scenes, Arthur Fleck (who is now the Joker) is apparently back in the white-walled Arkham State Hospital, with an implication that he has gotten away with the murders, either found incompetent or insane. This, too, has negative implications for the public viewing the film – and further perpetuates the misunderstanding that people with mental illness “get away” with their crimes. In reality, depending on the study, approximately one-quarter of those who pleaded insanity were found insane, and those facing jury trials (and public perception) are less likely to be found insane than those with bench trials. Public misinterpretations and outrage over the idea that a mentally unwell person might be found insane rather than guilty have existed for centuries, perhaps most memorably when John Hinckley Jr. attempted to assassinate former President Ronald Reagan, after identifying with a character in the film “Taxi Driver.” Let’s presume that Gotham has an insanity defense similar to other places in America. Then, in order to be found insane, Arthur’s pseudobulbar affect or his (unclear) mental illness would have either caused him not to know the nature and consequences of his acts, and/or to appreciate the wrongfulness of his acts (if we are fairly certain that Gotham is actually New York City). Neither of these appear to be true from the film. He knew that he was killing. No delusions or hallucinations made him think his acts were not wrong. Rather, he had an arguably rational motive – certainly the multitudes wearing clown masks in the subsequent uprisings against the powerful also believed his motive to be rational. He deliberately killed the bankers who mocked and beat him. He was also able to defer his killings until what he calculated was the right time to have the most impact – for example, on live television, or when he was alone with his mother in the hospital.

In closing, unrealistic portrayals of the link between mental illness, violence, and forensic hospitalization are seen on the silver screen in “Joker.” We hope that others who feign mental illness symptoms to evade criminal responsibility will emulate Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker as it will make it much easier for forensic psychiatrists to ferret out malingerers!

Dr. Hatters Friedman serves as the Phillip Resnick Professor of Forensic Psychiatry at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland. She is also editor of Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate (Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association Publishing [2019]), which was written by the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry’s Committee on Psychiatry & Law. Dr. Rosenbaum is a clinical and forensic psychiatrist in private practice in New York. She is an assistant clinical professor at New York University Langone Medical Center and on the faculty at Weill-Cornell Medical Center.

Postpartum psychosis: Protecting mother and infant

A new mother drowned her 6-month-old daughter in the bathtub. The married woman, who had a history of schizoaffective disorder, had been high functioning and worked in a managerial role prior to giving birth. However, within a day of delivery, her mental state deteriorated. She quickly became convinced that her daughter had a genetic disorder such as achondroplasia. Physical examinations, genetic testing, and x-rays all failed to alleviate her concerns. Examination of her computer revealed thousands of searches for various medical conditions and surgical treatments. After the baby’s death, the mother was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She eventually pled guilty to manslaughter.1

Mothers with postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically present fulminantly within days to weeks of giving birth. Symptoms of PPP may include not only psychosis, but also confusion and dysphoric mania. These symptoms often wax and wane, which can make it challenging to establish the diagnosis. In addition, many mothers hide their symptoms due to poor insight, delusions, or fear of loss of custody of their infant. In the vast majority of cases, psychiatric hospitalization is required to protect both mother and baby; untreated, there is an elevated risk of both maternal suicide and infanticide. This article discusses the presentation of PPP, its differential diagnosis, risk factors for developing PPP, suicide and infanticide risk assessment, treatment (including during breastfeeding), and prevention.

The bipolar connection

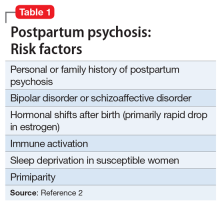

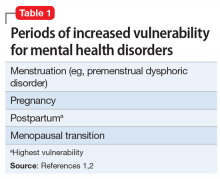

While multiple factors may increase the risk of PPP (Table 12), women with bipolar disorder have a particularly elevated risk. After experiencing incipient postpartum affective psychosis, a woman has a 50% to 80% chance of having another psychiatric episode, usually within the bipolar spectrum.2 Of all women with PPP, 70% to 90% have bipolar illness or schizoaffective disorder, while approximately 12% have schizophrenia.3,4Women with bipolar disorder are more likely to experience a postpartum psychiatric admission than mothers with any other psychiatric diagnosis5 and have an increased risk of PPP by a factor of 100 over the general population.2

For women with bipolar disorder, PPP should be understood as a recurrence of the chronic disease. Recent evidence does suggest, however, that a significant minority of women progress to experience mood and psychotic symptoms only in the postpartum period.6,7 It is hypothesized that this subgroup of women has a biologic vulnerability to affective psychosis that is limited to the postpartum period. Clinically, understanding a woman’s disease course is important because it may guide decision-making about prophylactic medications during or after pregnancy.

A rapid, delirium-like presentation

Postpartum psychosis is a rare disorder, with a prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 childbirths.3 While symptoms may begin days to weeks postpartum, the typical time of onset is between 3 to 10 days after birth, occurring after a woman has been discharged from the hospital and during a time of change and uncertainty. This can make the presentation of PPP a confusing and distressing experience for both the new mother and the family, resulting in delays in seeking care.

Subtle prodromal symptoms may include insomnia, mood fluctuation, and irritability. As symptoms progress, PPP is notable for a rapid onset and a delirium-like appearance that may include waxing and waning cognitive symptoms such as disorientation and confusion.8 Grossly disorganized behaviors and rapid mood fluctuations are typical. Distinct from mood episodes outside the peripartum period, women with PPP often experience mood-incongruent delusions and obsessive thoughts, often focused on their child.9 Women with PPP appear less likely to experience thought insertion or withdrawal or auditory hallucinations that give a running commentary.2

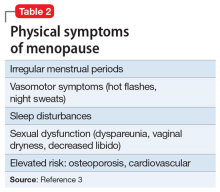

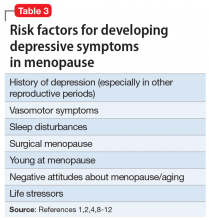

Differential diagnosis includes depression, OCD

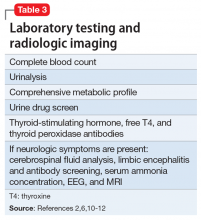

When evaluating a woman with possible postpartum psychotic symptoms or delirium, it is important to include a thorough history, physical examination, and relevant laboratory and/or imaging investigations to assess for organic causes or contributors (Table 22,6,10-12 and Table 32,6,10-12). A detailed psychiatric history should establish whether the patient is presenting with new-onset psychosis or has had previous mood or psychotic episodes that may have gone undetected. Important perinatal psychiatric differential diagnoses should include “baby blues,” postpartum depression (PPD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Continue to: PPP vs "baby blues."

PPP vs “baby blues.” “Baby blues” is not an official DSM-5 diagnosis but rather a normative postpartum experience that affects 50% to 80% of postpartum women. A woman with the “baby blues” may feel weepy or have mild mood lability, irritability, or anxiety; however, these symptoms do not significantly impair function. Peak symptoms typically occur between 2 to 5 days postpartum and generally resolve within 2 weeks. Women who have the “baby blues” are at an increased risk for PPD and should be monitored over time.13,14

PPP vs PPD. Postpartum depression affects approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers.15 Women with PPD may experience feelings of persistent and severe sadness, feelings of detachment, insomnia, and fatigue. Symptoms of PPD can interfere with a mother’s interest in caring for her baby and present a barrier to maternal bonding.16,17

As the awareness of PPD has increased in recent years, screening for depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy has increasingly become the standard of care.18 When evaluating a postpartum woman for PPD, it is important to consider PPP in the differential. Women with severe or persistent depressive symptoms may also develop psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, suicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming the infant may be present in either PPD or PPP. One study found that 41% of mothers with depression endorsed thoughts of harming their infants.19

PPP vs postpartum OCD. Postpartum obsessive-compulsive symptoms commonly occur comorbidly with PPD,9 and OCD often presents for the first time in the postpartum period.20 Obsessive-compulsive disorder affects between 2% to 9% of new mothers.21,22 It is critical to properly differentiate PPP from postpartum OCD. Clinical questions should be posed with a non-judgmental stance. Just as delusions in PPP are often focused on the infant, for women with OCD, obsessive thoughts may center on worries about the infant’s safety. Distressing obsessions about violence are common in OCD.23 Mothers with OCD may experience intrusive thinking about accidentally or purposefully harming their infant. For example, they may intrusively worry that they will accidentally put the baby in the microwave or oven, leave the baby in a hot car, or throw the baby down the stairs. However, a postpartum woman with OCD may be reluctant to share her ego-dystonic thoughts of infant harm. Mothers with OCD are not out of touch with reality; instead, their intrusive thoughts are ego-dystonic and distressing. These are thoughts and fears that they focus on and try to avoid, rather than plan. The psychiatrist must carefully differentiate between ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic thoughts. These patients often avoid seeking treatment because of their shame and guilt.23 Clinicians often under-recognize OCD and risk inappropriate hospitalization, treatment, and inappropriate referral to Child Protective Services (CPS).23

Perinatal psychiatric risk assessment

When a mother develops PPP, consider the risks of suicide, child harm, and infanticide. Although suicide risk is generally lower in the postpartum period, suicide is the cause of 20% of postpartum deaths.24,25 When PPP is untreated, suicide risk is elevated. A careful suicide risk assessment should be completed.

Continue to: Particularly in PPP...

Particularly in PPP, a mother may be at risk of child neglect or abuse due to her confused or delusional thinking and mood state.26 For example, one mother heated empty bottles and gave them to her baby, and then became frustrated when the baby continued to cry.

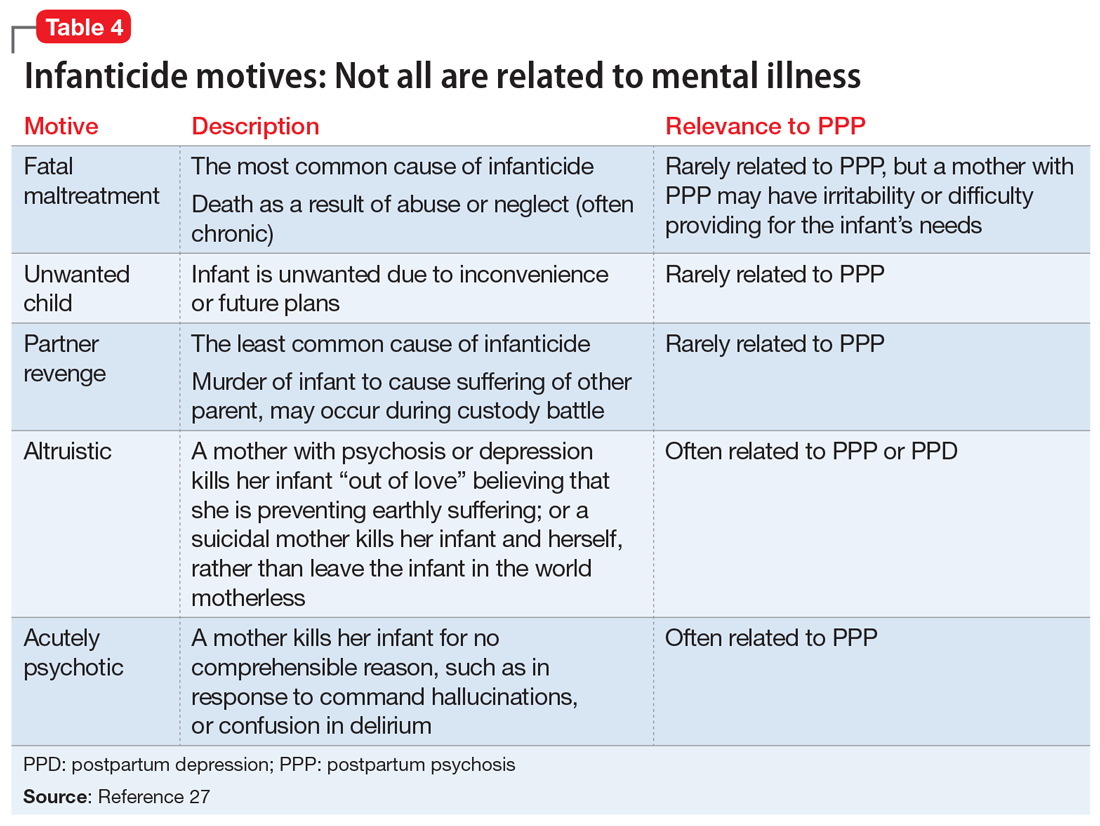

The risk of infanticide is also elevated in untreated PPP, with approximately 4% of these women committing infanticide.9 There are 5 motives for infanticide (Table 427). Altruistic and acutely psychotic motives are more likely to be related to PPP, while fatal maltreatment, unwanted child, and partner revenge motives are less likely to be related to PPP. Among mothers who kill both their child and themselves (filicide-suicide), altruistic motives were the most common.28 Mothers in psychiatric samples who kill their children have often experienced psychosis, suicidality, depression, and significant life stresses.27 Both infanticidal ideas and behaviors have been associated with psychotic thinking about the infant,29 so it is critical to ascertain whether the mother’s delusions or hallucinations involve the infant.30 In contrast, neonaticide (murder in the first day of life) is rarely related to PPP because PPP typically has a later onset.31

Treating acute PPP

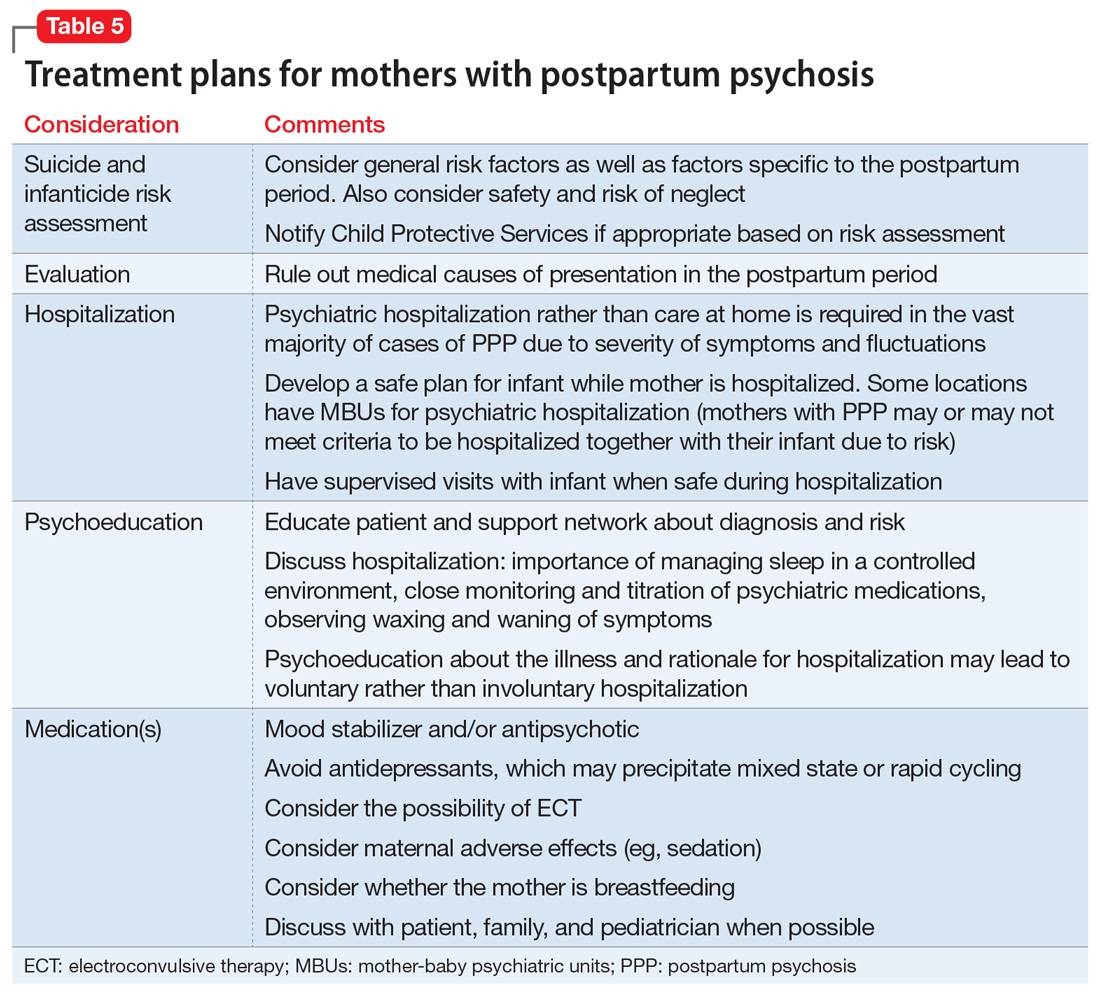

The fulminant nature of PPP can make its treatment difficult. Thinking through the case in an organized fashion is critical (Table 5).

Hospitalization. Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency with a rapid onset of symptoms. Hospitalization is required in almost all cases for diagnostic evaluation, assessment and management of safety, and initiation of treatment. While maternal-infant bonding in the perinatal period is important, infant safety is critical and usually requires maternal psychiatric hospitalization.

The specialized mother-baby psychiatric unit (MBU) is a model of care first developed in the United Kingdom and is now available in many European countries as well as in New Zealand and Australia. Mother-baby psychiatric units admit the mother and the baby together and provide dyadic treatment to allow for enhanced bonding and parenting support, and often to encourage breastfeeding.30 In the United States, there has been growing interest in specialized inpatient settings that acknowledge the importance of maternal-infant attachment in the treatment of perinatal disorders and provide care with a dyadic focus; however, differences in the health care payer system have been a barrier to full-scale MBUs. The Perinatal Psychiatry Inpatient Unit at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill is among the first of such a model in the United States.32

Continue to: Although this specialized treatment setting...

Although this specialized treatment setting is unlikely to be available in most American cities, treatment should still consider the maternal role. When possible, the infant should stay with the father or family members during the mother’s hospitalization, and supervised visits should be arranged when appropriate. If the mother is breastfeeding, or plans to breastfeed after the hospitalization, the treatment team may consider providing supervised use of a breast pump and making arrangements for breast milk storage. During the mother’s hospitalization, staff should provide psychoeducation and convey hopefulness and support.

Medication management. Mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are often used for acute management of PPP. The choice of medication is determined by individual symptoms, severity of presentation, previous response to medication, and maternal adverse effects.30 In a naturalistic study of 64 women admitted for new-onset PPP, sequential administration of benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and lithium was found to be effective in achieving remission for 99% of patients, with 80% sustaining remission at 9 months postpartum.6 Second-generation antipsychotics such as

Breastfeeding. It is important to discuss breastfeeding with the mother and her partner or family. The patient’s preference, the maternal and infant benefits of breastfeeding, the potential for sleep disruption, and the safety profile of needed medications should all be considered. Because sleep loss is a modifiable risk factor in PPP, the benefits of breastfeeding may be outweighed by the risks for some patients.9 For others, breastfeeding during the day and bottle-feeding at night may be preferred.

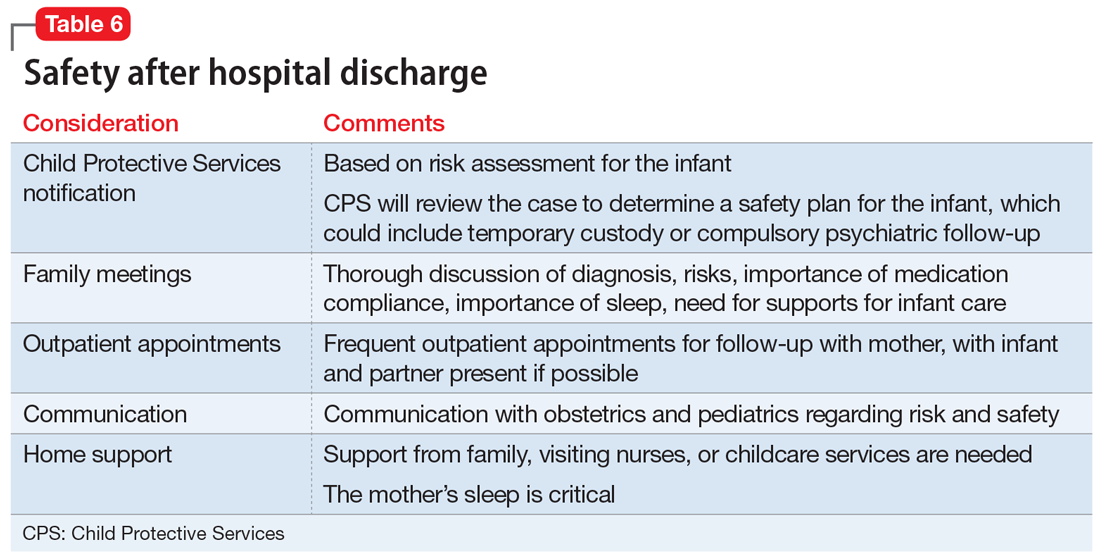

What to consider during discharge planning

Discharge arrangements require careful consideration (Table 6). Meet with the family prior to discharge to provide psychoeducation and to underscore the importance of family involvement with both mother and infant. It is important to ensure adequate support at home, including at night, since sleep is critical to improved stability. Encourage the patient and her family to monitor for early warning signs of relapse, which might include refractory insomnia, mood instability, poor judgment, or hypomanic symptoms.35 She should be followed closely as an outpatient. Having her partner (or another close family member) and infant present during appointments can help in obtaining collateral information and assessing mother-infant bonding. The clinician should also consider whether it is necessary to contact CPS. Many mothers with mental illness appropriately parent their child, but CPS should be alerted when there is a reasonable concern about safe parenting—abuse, neglect, or significant risk.36

Take steps for prevention

An important part of managing PPP is prevention. This involves providing preconception counseling to the woman and her partner.30 Preconception advice should be individualized and include discussion of:

- risks of relapse in pregnancy and the postpartum period

- optimal physical and mental health

- potential risks and benefits of medication options in pregnancy

- potential effects of untreated illness for the fetus, infant, and family

- a strategy outlining whether medication is continued in pregnancy or started in the postpartum period.

Continue to: For women at risk of PPP...

For women at risk of PPP, the risks of medications need to be balanced with the risks of untreated illness. To reduce the risk of PPP relapse, guidelines recommend a robust antenatal care plan that should include37,38:

- close monitoring of a woman’s mental state for early warning signs of PPP, with active participation from the woman’s partner and family

- ongoing discussion of the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy (and, for women who prefer to not take medication in the first trimester, a plan for when medications will be restarted)

- collaboration with other professionals involved in care during pregnancy and postpartum (eg, obstetricians, midwives, family practitioners, pediatricians)

- planning to minimize risk factors associated with relapse (eg, sleep deprivation, lack of social supports, domestic violence, and substance abuse).

Evidence clearly suggests that women with bipolar disorder are at increased risk for illness recurrence without continued maintenance medication.39 A subgroup of women with PPP go on to have psychosis limited to the postpartum period, and reinstating prophylactic medication in late pregnancy (preferably) or immediately after birth should be discussed.2 The choice of prophylactic medication should be determined by the woman’s previous response.

Regarding prophylaxis, the most evidence exists for lithium.6 Lithium use during the first trimester carries a risk of Ebstein’s anomaly. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis have concluded that the teratogenic risks of lithium have been overestimated.40,41

Lamotrigine is an alternative mood stabilizer with a favorable safety profile in pregnancy. In a small naturalistic study in which lamotrigine was continued in pregnancy in women with bipolar disorder, the medication was effective in preventing relapse in pregnancy and postpartum.42 A small population-based cohort study found lamotrigine was as effective as lithium in preventing severe postpartum relapse in women with bipolar disorder,43 although this study was limited by its observational design. Recently published studies have found no significant association between

Box

It is essential to consider the patient’s individual symptoms and treatment history when making pharmacologic recommendations during pregnancy. Discussion with the patient about the risks and benefits of lithium is recommended. For women who continue to use lithium during pregnancy, ongoing pharmacokinetic changes warrant more frequent monitoring (some experts advise monthly monitoring throughout pregnancy, moving to more frequent monitoring at 36 weeks).47 During labor, the team might consider temporary cessation of lithium and particular attention to hydration status.30 In the postpartum period, there is a quick return to baseline glomerular filtration rate and a rapid decrease in vascular volume, so it is advisable to restart the patient at her pre-pregnancy lithium dosage. It is recommended to check lithium levels within 24 hours of delivery.47 While lithium is not an absolute contraindication to breastfeeding, there is particular concern in situations of prematurity or neonatal dehydration. Collaboration with and close monitoring by the pediatrician is essential to determine an infant monitoring plan.48

If lamotrigine is used during pregnancy, be aware that pregnancy-related pharmacokinetic changes result in increased lamotrigine clearance, which will vary in magnitude among individuals. Faster clearance may necessitate dose increases during pregnancy and a taper back to pre-pregnancy dose in the postpartum period. Dosing should always take clinical symptoms into account.

Pharmacotherapy can reduce relapse risk

To prevent relapse in the postpartum period, consider initiating treatment with mood stabilizers and/or SGAs, particularly for women with bipolar disorder who do not take medication during pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis found a high postpartum relapse rate (66%) in women with bipolar disorder who did not take prophylactic medication, compared with a relapse rate of 23% for women who did take such medication. In women with psychosis limited to the postpartum period, prophylaxis with lithium or antipsychotics in the immediate postpartum can prevent relapse.39 The SGAs olanzapine and quetiapine are often used to manage acute symptoms because they are considered acceptable during breastfeeding.33 The use of lithium when breastfeeding is complex to manage48 and may require advice to not breastfeed, which can be an important consideration for patients and their families.

Bottom Line

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically presents with a rapid onset of hallucinations, delusions, confusion, and mood swings within days to weeks of giving birth. Mothers with PPP almost always require hospitalization for the safety of their infants and themselves. Mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics are used for acute management.

Related Resources

- Clark CT, Wisner KL. Treatment of peripartum bipolar disorder. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2018;45:403-417.

- Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health. https://womensmentalhealth.org/. 2018.

- Postpartum Support International. Postpartum psychosis. http://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/postpartumpsychosis/. 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Bromocriptine • Cycloset, Parlodel

Cabergoline • Dostinex

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

1. Hall L. Mother who killed baby believing she was a dwarf should not be jailed, court told. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://www.smh.com.au/national/nsw/mother-who-killed-baby-believing-she-was-a-dwarf-should-not-be-jailed-court-told-20170428-gvud4d.html. Published April 28, 2017. Accessed March 12, 2019.

2. Bergink V, Rasgon N, Wisner KL. Postpartum psychosis: madness, mania, and melancholia in motherhood. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(12):1179-1188.

3. Sit D, Rothschild AJ, Wisner KL. A review of postpartum psychosis. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2006;15(4):352-368.

4. Kendell RE, Chalmers JC, Platz C. Epidemiology of puerperal psychoses. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(5):662-673.

5. Munk-Olsen T, Laursen TM, Mendelson T, et al. Risks and predictors of readmission for a mental disorder during the postpartum period. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66(2):189-195.

6. Bergink V, Burgerhout KM, Koorengevel KM, et al. Treatment of psychosis and mania in the postpartum period. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(2):115-123.

7. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Munk-Olsen T, et al. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;173(2):117-127.

8. Wisner KL, Peindl K, Hanusa BH. Symptomatology of affective and psychotic illnesses related to childbearing. J Affect Disord. 1994;30(2):77-87.

9. Spinelli MG. Postpartum psychosis: detection of risk and management. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(4):405-408.

10. Fassier T, Guffon N, Acquaviva C, et al. Misdiagnosed postpartum psychosis revealing a late-onset urea cycle disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(6):576-580.

11. Yu AYX, Moore FG. Paraneoplastic encephalitis presenting as postpartum psychosis. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):568-570.

12. Patil NJ, Yadav SS, Gokhale YA, et al. Primary hypoparathyroidism: psychosis in postpartum period. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:506-508.

13. O’Hara MW, Schlechte JA, Lewis DA, et al. Prospective study of postpartum blues: biologic and psychosocial factors. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48(9):801-806.

14. Burt VK, Hendrick VC. Clinical manual of women’s mental health. Washington, DC. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2007:79-80.

15. Melzer-Brody S. Postpartum depression: what to tell patients who breast-feed. Current Psychiatry. 2008;7(5):87-95.

16. Alhusen JL, Gross D, Hayat MJ, et al. The role of mental health on maternal‐fetal attachment in low‐income women. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2012;41(6):E71-E81.

17. McLearn KT, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms at 2 to 4 months postpartum and early parenting practices. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160(3):279-284.

18. Committee on Obstetric Practice. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion no. 630. Screening for perinatal depression. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1268-1271.

19. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

20. Miller ES, Hoxha D, Wisner KL, et al. Obsessions and compulsions in postpartum women without obsessive compulsive disorder. J Womens Health. 2015;24(10):825-830.

21. Russell EJ, Fawcett JM, Mazmanian D. Risk of obsessive-compulsive disorder in pregnant and postpartum women: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(4):377-385.

22. Zambaldi CF, Cantilino A, Montenegro AC, et al. Postpartum obsessive-compulsive disorder: prevalence and clinical characteristics. Compr Psychiatry. 2009;50(6):503-509.

23. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

24. Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2005;8(2):77-87.

25. Samandari G, Martin SL, Kupper LL, et al. Are pregnant and postpartum women: at increased risk for violent death? Suicide and homicide findings from North Carolina. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(5):660-669.

26. Friedman SH, Sorrentino R. Commentary: postpartum psychosis, infanticide, and insanity—implications for forensic psychiatry. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2012;40(3):326-332.

27. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

28. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

29. Chandra PS, Venkatasubramanian G, Thomas T. Infanticidal ideas and infanticidal behavior in Indian women with severe postpartum psychiatric disorders. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190(7):457-461.

30. Jones I, Chandra PS, Dazzan P, et al. Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1789-1799.

31. Friedman SH. Neonaticide. In: Friedman SH. Family murder: pathologies of love and hate. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018:53-67.

32. Meltzer-Brody S, Brandon AR, Pearson B, et al. Evaluating the clinical effectiveness of a specialized perinatal psychiatry inpatient unit. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2014;17(2):107-113.

33. Klinger G, Stahl B, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Antipsychotic drugs and breastfeeding. Pediatri Endocrinol Rev. 2013;10(3):308-317.

34. Focht A, Kellner CH. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) in the treatment of postpartum psychosis. J ECT. 2012;28(1):31-33.

35. Heron J, McGuinness M, Blackmore ER, et al. Early postpartum symptoms in puerperal psychosis. BJOG. 2008;115(3):348-353.

36. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

37. Centre of Perinatal Excellence. National Perinatal Mental Health Guideline. http://cope.org.au/about/review-of-new-perinatal-mental-health-guidelines/. Published October 27, 2017. Accessed November 22, 2018.

38. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Antenatal and postnatal mental health overview. https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/antenatal-and-postnatal-mental-health. 2017. Accessed November 22, 2018.

39. Wesseloo R, Kamperman AM, Olsen TM, et al. Risk of postpartum relapse in bipolar disorder and postpartum psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(2):117-127.

40. McKnight RF, Adida M, Budge K, et al. Lithium toxicity profile: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2012;379(9817):721-728.

41. Munk-Olsen T, Liu X, Viktorin A, et al. Maternal and infant outcomes associated with lithium use in pregnancy: an international collaborative meta-analysis of six cohort studies. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(8):644-652.

42. Prakash C, Friedman SH, Moller-Olsen C, et al. Maternal and fetal outcomes after lamotrigine use in pregnancy: a retrospective analysis from an urban maternal mental health centre in New Zealand. Psychopharmacology Bull. 2016;46(2):63-69.

43. Wesseloo R, Liu X, Clark CT, et al. Risk of postpartum episodes in women with bipolar disorder after lamotrigine or lithium use in pregnancy: a population-based cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2017;218:394-397.

44. Dolk H, Wang H, Loane M, et al. Lamotrigine use in pregnancy and risk of orofacial cleft and other congenital anomalies. Neurology. 2016;86(18):1716-1725.

45. Diav-Citrin O, Shechtman S, Zvi N, et al. Is it safe to use lamotrigine during pregnancy? A prospective comparative observational study. Birth Defects Res. 2017;109(15):1196-1203.

46. Kong L, Zhou T, Wang B, et al. The risks associated with the use of lamotrigine during pregnancy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2018;22(1):2-5.

47. Deligiannidis KM, Byatt N, Freeman MP. Pharmacotherapy for mood disorders in pregnancy: a review of pharmacokinetic changes and clinical recommendations for therapeutic drug monitoring. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34(2):244.

48. Bogen DL, Sit D, Genovese A, et al. Three cases of lithium exposure and exclusive breastfeeding. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(1):69-72.

A new mother drowned her 6-month-old daughter in the bathtub. The married woman, who had a history of schizoaffective disorder, had been high functioning and worked in a managerial role prior to giving birth. However, within a day of delivery, her mental state deteriorated. She quickly became convinced that her daughter had a genetic disorder such as achondroplasia. Physical examinations, genetic testing, and x-rays all failed to alleviate her concerns. Examination of her computer revealed thousands of searches for various medical conditions and surgical treatments. After the baby’s death, the mother was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She eventually pled guilty to manslaughter.1

Mothers with postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically present fulminantly within days to weeks of giving birth. Symptoms of PPP may include not only psychosis, but also confusion and dysphoric mania. These symptoms often wax and wane, which can make it challenging to establish the diagnosis. In addition, many mothers hide their symptoms due to poor insight, delusions, or fear of loss of custody of their infant. In the vast majority of cases, psychiatric hospitalization is required to protect both mother and baby; untreated, there is an elevated risk of both maternal suicide and infanticide. This article discusses the presentation of PPP, its differential diagnosis, risk factors for developing PPP, suicide and infanticide risk assessment, treatment (including during breastfeeding), and prevention.

The bipolar connection

While multiple factors may increase the risk of PPP (Table 12), women with bipolar disorder have a particularly elevated risk. After experiencing incipient postpartum affective psychosis, a woman has a 50% to 80% chance of having another psychiatric episode, usually within the bipolar spectrum.2 Of all women with PPP, 70% to 90% have bipolar illness or schizoaffective disorder, while approximately 12% have schizophrenia.3,4Women with bipolar disorder are more likely to experience a postpartum psychiatric admission than mothers with any other psychiatric diagnosis5 and have an increased risk of PPP by a factor of 100 over the general population.2

For women with bipolar disorder, PPP should be understood as a recurrence of the chronic disease. Recent evidence does suggest, however, that a significant minority of women progress to experience mood and psychotic symptoms only in the postpartum period.6,7 It is hypothesized that this subgroup of women has a biologic vulnerability to affective psychosis that is limited to the postpartum period. Clinically, understanding a woman’s disease course is important because it may guide decision-making about prophylactic medications during or after pregnancy.

A rapid, delirium-like presentation

Postpartum psychosis is a rare disorder, with a prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 childbirths.3 While symptoms may begin days to weeks postpartum, the typical time of onset is between 3 to 10 days after birth, occurring after a woman has been discharged from the hospital and during a time of change and uncertainty. This can make the presentation of PPP a confusing and distressing experience for both the new mother and the family, resulting in delays in seeking care.

Subtle prodromal symptoms may include insomnia, mood fluctuation, and irritability. As symptoms progress, PPP is notable for a rapid onset and a delirium-like appearance that may include waxing and waning cognitive symptoms such as disorientation and confusion.8 Grossly disorganized behaviors and rapid mood fluctuations are typical. Distinct from mood episodes outside the peripartum period, women with PPP often experience mood-incongruent delusions and obsessive thoughts, often focused on their child.9 Women with PPP appear less likely to experience thought insertion or withdrawal or auditory hallucinations that give a running commentary.2

Differential diagnosis includes depression, OCD

When evaluating a woman with possible postpartum psychotic symptoms or delirium, it is important to include a thorough history, physical examination, and relevant laboratory and/or imaging investigations to assess for organic causes or contributors (Table 22,6,10-12 and Table 32,6,10-12). A detailed psychiatric history should establish whether the patient is presenting with new-onset psychosis or has had previous mood or psychotic episodes that may have gone undetected. Important perinatal psychiatric differential diagnoses should include “baby blues,” postpartum depression (PPD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Continue to: PPP vs "baby blues."

PPP vs “baby blues.” “Baby blues” is not an official DSM-5 diagnosis but rather a normative postpartum experience that affects 50% to 80% of postpartum women. A woman with the “baby blues” may feel weepy or have mild mood lability, irritability, or anxiety; however, these symptoms do not significantly impair function. Peak symptoms typically occur between 2 to 5 days postpartum and generally resolve within 2 weeks. Women who have the “baby blues” are at an increased risk for PPD and should be monitored over time.13,14

PPP vs PPD. Postpartum depression affects approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers.15 Women with PPD may experience feelings of persistent and severe sadness, feelings of detachment, insomnia, and fatigue. Symptoms of PPD can interfere with a mother’s interest in caring for her baby and present a barrier to maternal bonding.16,17

As the awareness of PPD has increased in recent years, screening for depressive symptoms during and after pregnancy has increasingly become the standard of care.18 When evaluating a postpartum woman for PPD, it is important to consider PPP in the differential. Women with severe or persistent depressive symptoms may also develop psychotic symptoms. Furthermore, suicidal thoughts or thoughts of harming the infant may be present in either PPD or PPP. One study found that 41% of mothers with depression endorsed thoughts of harming their infants.19

PPP vs postpartum OCD. Postpartum obsessive-compulsive symptoms commonly occur comorbidly with PPD,9 and OCD often presents for the first time in the postpartum period.20 Obsessive-compulsive disorder affects between 2% to 9% of new mothers.21,22 It is critical to properly differentiate PPP from postpartum OCD. Clinical questions should be posed with a non-judgmental stance. Just as delusions in PPP are often focused on the infant, for women with OCD, obsessive thoughts may center on worries about the infant’s safety. Distressing obsessions about violence are common in OCD.23 Mothers with OCD may experience intrusive thinking about accidentally or purposefully harming their infant. For example, they may intrusively worry that they will accidentally put the baby in the microwave or oven, leave the baby in a hot car, or throw the baby down the stairs. However, a postpartum woman with OCD may be reluctant to share her ego-dystonic thoughts of infant harm. Mothers with OCD are not out of touch with reality; instead, their intrusive thoughts are ego-dystonic and distressing. These are thoughts and fears that they focus on and try to avoid, rather than plan. The psychiatrist must carefully differentiate between ego-syntonic and ego-dystonic thoughts. These patients often avoid seeking treatment because of their shame and guilt.23 Clinicians often under-recognize OCD and risk inappropriate hospitalization, treatment, and inappropriate referral to Child Protective Services (CPS).23

Perinatal psychiatric risk assessment

When a mother develops PPP, consider the risks of suicide, child harm, and infanticide. Although suicide risk is generally lower in the postpartum period, suicide is the cause of 20% of postpartum deaths.24,25 When PPP is untreated, suicide risk is elevated. A careful suicide risk assessment should be completed.

Continue to: Particularly in PPP...

Particularly in PPP, a mother may be at risk of child neglect or abuse due to her confused or delusional thinking and mood state.26 For example, one mother heated empty bottles and gave them to her baby, and then became frustrated when the baby continued to cry.

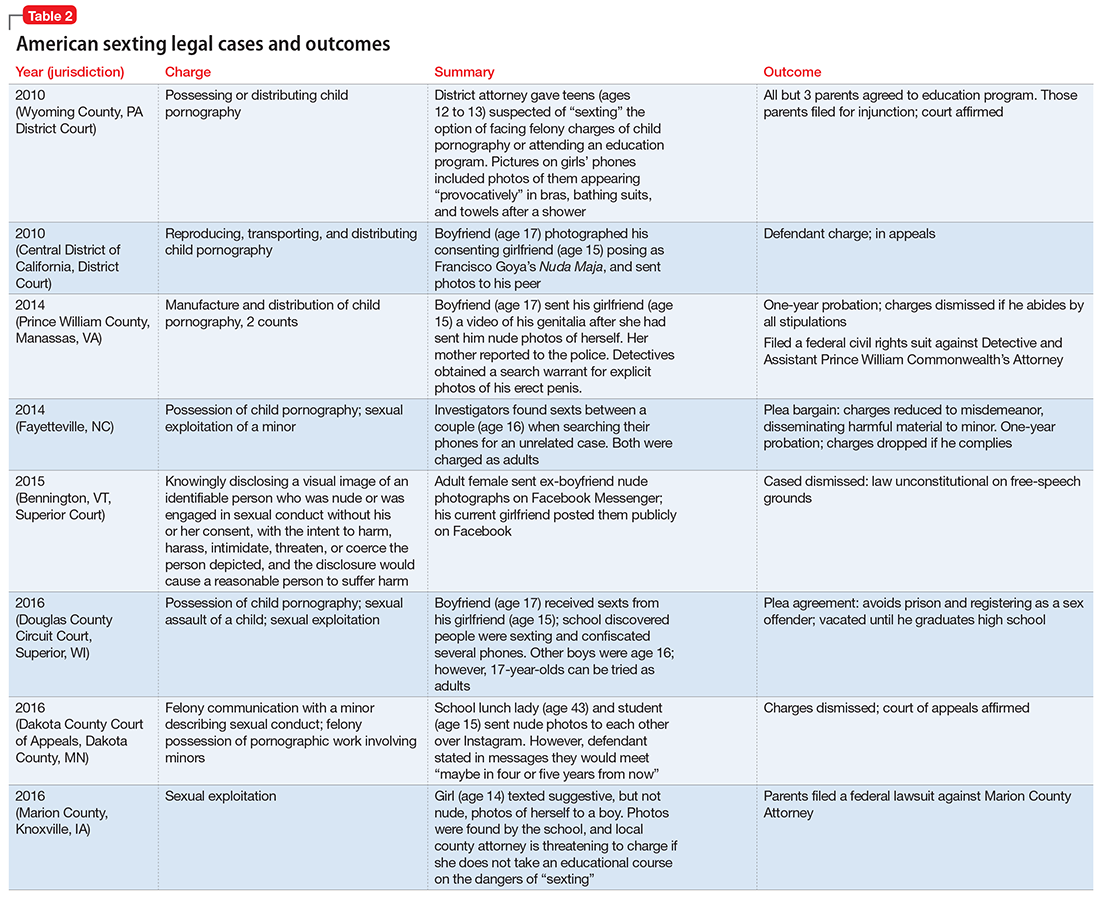

The risk of infanticide is also elevated in untreated PPP, with approximately 4% of these women committing infanticide.9 There are 5 motives for infanticide (Table 427). Altruistic and acutely psychotic motives are more likely to be related to PPP, while fatal maltreatment, unwanted child, and partner revenge motives are less likely to be related to PPP. Among mothers who kill both their child and themselves (filicide-suicide), altruistic motives were the most common.28 Mothers in psychiatric samples who kill their children have often experienced psychosis, suicidality, depression, and significant life stresses.27 Both infanticidal ideas and behaviors have been associated with psychotic thinking about the infant,29 so it is critical to ascertain whether the mother’s delusions or hallucinations involve the infant.30 In contrast, neonaticide (murder in the first day of life) is rarely related to PPP because PPP typically has a later onset.31

Treating acute PPP

The fulminant nature of PPP can make its treatment difficult. Thinking through the case in an organized fashion is critical (Table 5).

Hospitalization. Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency with a rapid onset of symptoms. Hospitalization is required in almost all cases for diagnostic evaluation, assessment and management of safety, and initiation of treatment. While maternal-infant bonding in the perinatal period is important, infant safety is critical and usually requires maternal psychiatric hospitalization.

The specialized mother-baby psychiatric unit (MBU) is a model of care first developed in the United Kingdom and is now available in many European countries as well as in New Zealand and Australia. Mother-baby psychiatric units admit the mother and the baby together and provide dyadic treatment to allow for enhanced bonding and parenting support, and often to encourage breastfeeding.30 In the United States, there has been growing interest in specialized inpatient settings that acknowledge the importance of maternal-infant attachment in the treatment of perinatal disorders and provide care with a dyadic focus; however, differences in the health care payer system have been a barrier to full-scale MBUs. The Perinatal Psychiatry Inpatient Unit at University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill is among the first of such a model in the United States.32

Continue to: Although this specialized treatment setting...

Although this specialized treatment setting is unlikely to be available in most American cities, treatment should still consider the maternal role. When possible, the infant should stay with the father or family members during the mother’s hospitalization, and supervised visits should be arranged when appropriate. If the mother is breastfeeding, or plans to breastfeed after the hospitalization, the treatment team may consider providing supervised use of a breast pump and making arrangements for breast milk storage. During the mother’s hospitalization, staff should provide psychoeducation and convey hopefulness and support.

Medication management. Mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are often used for acute management of PPP. The choice of medication is determined by individual symptoms, severity of presentation, previous response to medication, and maternal adverse effects.30 In a naturalistic study of 64 women admitted for new-onset PPP, sequential administration of benzodiazepines, antipsychotics, and lithium was found to be effective in achieving remission for 99% of patients, with 80% sustaining remission at 9 months postpartum.6 Second-generation antipsychotics such as

Breastfeeding. It is important to discuss breastfeeding with the mother and her partner or family. The patient’s preference, the maternal and infant benefits of breastfeeding, the potential for sleep disruption, and the safety profile of needed medications should all be considered. Because sleep loss is a modifiable risk factor in PPP, the benefits of breastfeeding may be outweighed by the risks for some patients.9 For others, breastfeeding during the day and bottle-feeding at night may be preferred.

What to consider during discharge planning

Discharge arrangements require careful consideration (Table 6). Meet with the family prior to discharge to provide psychoeducation and to underscore the importance of family involvement with both mother and infant. It is important to ensure adequate support at home, including at night, since sleep is critical to improved stability. Encourage the patient and her family to monitor for early warning signs of relapse, which might include refractory insomnia, mood instability, poor judgment, or hypomanic symptoms.35 She should be followed closely as an outpatient. Having her partner (or another close family member) and infant present during appointments can help in obtaining collateral information and assessing mother-infant bonding. The clinician should also consider whether it is necessary to contact CPS. Many mothers with mental illness appropriately parent their child, but CPS should be alerted when there is a reasonable concern about safe parenting—abuse, neglect, or significant risk.36

Take steps for prevention

An important part of managing PPP is prevention. This involves providing preconception counseling to the woman and her partner.30 Preconception advice should be individualized and include discussion of:

- risks of relapse in pregnancy and the postpartum period

- optimal physical and mental health

- potential risks and benefits of medication options in pregnancy

- potential effects of untreated illness for the fetus, infant, and family

- a strategy outlining whether medication is continued in pregnancy or started in the postpartum period.

Continue to: For women at risk of PPP...

For women at risk of PPP, the risks of medications need to be balanced with the risks of untreated illness. To reduce the risk of PPP relapse, guidelines recommend a robust antenatal care plan that should include37,38:

- close monitoring of a woman’s mental state for early warning signs of PPP, with active participation from the woman’s partner and family

- ongoing discussion of the risks and benefits of pharmacotherapy (and, for women who prefer to not take medication in the first trimester, a plan for when medications will be restarted)

- collaboration with other professionals involved in care during pregnancy and postpartum (eg, obstetricians, midwives, family practitioners, pediatricians)

- planning to minimize risk factors associated with relapse (eg, sleep deprivation, lack of social supports, domestic violence, and substance abuse).

Evidence clearly suggests that women with bipolar disorder are at increased risk for illness recurrence without continued maintenance medication.39 A subgroup of women with PPP go on to have psychosis limited to the postpartum period, and reinstating prophylactic medication in late pregnancy (preferably) or immediately after birth should be discussed.2 The choice of prophylactic medication should be determined by the woman’s previous response.

Regarding prophylaxis, the most evidence exists for lithium.6 Lithium use during the first trimester carries a risk of Ebstein’s anomaly. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis have concluded that the teratogenic risks of lithium have been overestimated.40,41

Lamotrigine is an alternative mood stabilizer with a favorable safety profile in pregnancy. In a small naturalistic study in which lamotrigine was continued in pregnancy in women with bipolar disorder, the medication was effective in preventing relapse in pregnancy and postpartum.42 A small population-based cohort study found lamotrigine was as effective as lithium in preventing severe postpartum relapse in women with bipolar disorder,43 although this study was limited by its observational design. Recently published studies have found no significant association between

Box

It is essential to consider the patient’s individual symptoms and treatment history when making pharmacologic recommendations during pregnancy. Discussion with the patient about the risks and benefits of lithium is recommended. For women who continue to use lithium during pregnancy, ongoing pharmacokinetic changes warrant more frequent monitoring (some experts advise monthly monitoring throughout pregnancy, moving to more frequent monitoring at 36 weeks).47 During labor, the team might consider temporary cessation of lithium and particular attention to hydration status.30 In the postpartum period, there is a quick return to baseline glomerular filtration rate and a rapid decrease in vascular volume, so it is advisable to restart the patient at her pre-pregnancy lithium dosage. It is recommended to check lithium levels within 24 hours of delivery.47 While lithium is not an absolute contraindication to breastfeeding, there is particular concern in situations of prematurity or neonatal dehydration. Collaboration with and close monitoring by the pediatrician is essential to determine an infant monitoring plan.48

If lamotrigine is used during pregnancy, be aware that pregnancy-related pharmacokinetic changes result in increased lamotrigine clearance, which will vary in magnitude among individuals. Faster clearance may necessitate dose increases during pregnancy and a taper back to pre-pregnancy dose in the postpartum period. Dosing should always take clinical symptoms into account.

Pharmacotherapy can reduce relapse risk

To prevent relapse in the postpartum period, consider initiating treatment with mood stabilizers and/or SGAs, particularly for women with bipolar disorder who do not take medication during pregnancy. A recent meta-analysis found a high postpartum relapse rate (66%) in women with bipolar disorder who did not take prophylactic medication, compared with a relapse rate of 23% for women who did take such medication. In women with psychosis limited to the postpartum period, prophylaxis with lithium or antipsychotics in the immediate postpartum can prevent relapse.39 The SGAs olanzapine and quetiapine are often used to manage acute symptoms because they are considered acceptable during breastfeeding.33 The use of lithium when breastfeeding is complex to manage48 and may require advice to not breastfeed, which can be an important consideration for patients and their families.

Bottom Line

Postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically presents with a rapid onset of hallucinations, delusions, confusion, and mood swings within days to weeks of giving birth. Mothers with PPP almost always require hospitalization for the safety of their infants and themselves. Mood stabilizers and second-generation antipsychotics are used for acute management.

Related Resources

- Clark CT, Wisner KL. Treatment of peripartum bipolar disorder. Obstet Gynecol Clin N Am. 2018;45:403-417.

- Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health. https://womensmentalhealth.org/. 2018.

- Postpartum Support International. Postpartum psychosis. http://www.postpartum.net/learn-more/postpartumpsychosis/. 2019.

Drug Brand Names

Bromocriptine • Cycloset, Parlodel

Cabergoline • Dostinex

Lamotrigine • Lamictal

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

A new mother drowned her 6-month-old daughter in the bathtub. The married woman, who had a history of schizoaffective disorder, had been high functioning and worked in a managerial role prior to giving birth. However, within a day of delivery, her mental state deteriorated. She quickly became convinced that her daughter had a genetic disorder such as achondroplasia. Physical examinations, genetic testing, and x-rays all failed to alleviate her concerns. Examination of her computer revealed thousands of searches for various medical conditions and surgical treatments. After the baby’s death, the mother was admitted to a psychiatric hospital. She eventually pled guilty to manslaughter.1

Mothers with postpartum psychosis (PPP) typically present fulminantly within days to weeks of giving birth. Symptoms of PPP may include not only psychosis, but also confusion and dysphoric mania. These symptoms often wax and wane, which can make it challenging to establish the diagnosis. In addition, many mothers hide their symptoms due to poor insight, delusions, or fear of loss of custody of their infant. In the vast majority of cases, psychiatric hospitalization is required to protect both mother and baby; untreated, there is an elevated risk of both maternal suicide and infanticide. This article discusses the presentation of PPP, its differential diagnosis, risk factors for developing PPP, suicide and infanticide risk assessment, treatment (including during breastfeeding), and prevention.

The bipolar connection

While multiple factors may increase the risk of PPP (Table 12), women with bipolar disorder have a particularly elevated risk. After experiencing incipient postpartum affective psychosis, a woman has a 50% to 80% chance of having another psychiatric episode, usually within the bipolar spectrum.2 Of all women with PPP, 70% to 90% have bipolar illness or schizoaffective disorder, while approximately 12% have schizophrenia.3,4Women with bipolar disorder are more likely to experience a postpartum psychiatric admission than mothers with any other psychiatric diagnosis5 and have an increased risk of PPP by a factor of 100 over the general population.2

For women with bipolar disorder, PPP should be understood as a recurrence of the chronic disease. Recent evidence does suggest, however, that a significant minority of women progress to experience mood and psychotic symptoms only in the postpartum period.6,7 It is hypothesized that this subgroup of women has a biologic vulnerability to affective psychosis that is limited to the postpartum period. Clinically, understanding a woman’s disease course is important because it may guide decision-making about prophylactic medications during or after pregnancy.

A rapid, delirium-like presentation

Postpartum psychosis is a rare disorder, with a prevalence of 1 to 2 cases per 1,000 childbirths.3 While symptoms may begin days to weeks postpartum, the typical time of onset is between 3 to 10 days after birth, occurring after a woman has been discharged from the hospital and during a time of change and uncertainty. This can make the presentation of PPP a confusing and distressing experience for both the new mother and the family, resulting in delays in seeking care.

Subtle prodromal symptoms may include insomnia, mood fluctuation, and irritability. As symptoms progress, PPP is notable for a rapid onset and a delirium-like appearance that may include waxing and waning cognitive symptoms such as disorientation and confusion.8 Grossly disorganized behaviors and rapid mood fluctuations are typical. Distinct from mood episodes outside the peripartum period, women with PPP often experience mood-incongruent delusions and obsessive thoughts, often focused on their child.9 Women with PPP appear less likely to experience thought insertion or withdrawal or auditory hallucinations that give a running commentary.2

Differential diagnosis includes depression, OCD

When evaluating a woman with possible postpartum psychotic symptoms or delirium, it is important to include a thorough history, physical examination, and relevant laboratory and/or imaging investigations to assess for organic causes or contributors (Table 22,6,10-12 and Table 32,6,10-12). A detailed psychiatric history should establish whether the patient is presenting with new-onset psychosis or has had previous mood or psychotic episodes that may have gone undetected. Important perinatal psychiatric differential diagnoses should include “baby blues,” postpartum depression (PPD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Continue to: PPP vs "baby blues."

PPP vs “baby blues.” “Baby blues” is not an official DSM-5 diagnosis but rather a normative postpartum experience that affects 50% to 80% of postpartum women. A woman with the “baby blues” may feel weepy or have mild mood lability, irritability, or anxiety; however, these symptoms do not significantly impair function. Peak symptoms typically occur between 2 to 5 days postpartum and generally resolve within 2 weeks. Women who have the “baby blues” are at an increased risk for PPD and should be monitored over time.13,14

PPP vs PPD. Postpartum depression affects approximately 10% to 15% of new mothers.15 Women with PPD may experience feelings of persistent and severe sadness, feelings of detachment, insomnia, and fatigue. Symptoms of PPD can interfere with a mother’s interest in caring for her baby and present a barrier to maternal bonding.16,17