User login

Sign‐Out within the Electronic Medical Record

The delivery of safe, high‐quality care to hospitalized patients depends on effective communication among providers.1, 2 Inpatients may receive care from a number of specialists in addition to their primary hospital physicians, and each provider may practice in a group that transfers care of individual patients among its members. This issue is exacerbated in teaching hospitals because fellows, residents, and interns make frequent transfers of care because of work‐hour rules.3, 4 Finally, teams of physician providers making management decisions must effectively communicate with other members of the care team, such as nurses, dieticians, and social workers, who also may be part of a group practice involving transfers. A patient hospitalized for just a few days in a modern hospital may receive care from dozens of providers and be the subject of multiple transfers of care, or handoffs, that require effective communication. Therefore, as part of its 2006 National Patient Safety Goals,5 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) now requires that each hospital implement a standardized, structured approach to transfers of care.

Transfers of care have been shown to be a source of medical errors and adverse patient outcomes.2, 6, 7 In many cases, the critical information necessary to avert medical errors exists but is not available in real time to providers.6

Traditionally, provider teams have relied on the patient chart, in concert with direct patient evaluation, to provide the information to guide decision making during a hospitalization. Unfortunately, the structure of the chart in most hospitals has evolved little over the past 80 years810 and remains organized so that information is more easily filed than retrieved, read, or summarized.811 Typically, electronic medical records (EMRs) mimic the appearance of paper records and include similar organizational flaws.12 As a result, many providers have created ad hoc informational systems, separate from the chart, designed to track a patient's progress over time and to facilitate transfers of care. These sign‐out systems, which are intended to complement verbal sign‐out between providers,1315 range in complexity from simple handwritten index cards16 to adapted spreadsheets, PDA systems,17, 18 and more complex data systems (eg, FileMaker Pro)19 and often contain crucial information not found elsewhere in the medical record.20, 21

Although sign‐out systems are crucial to patient safety, they have several drawbacks. First, ad‐hoc informational systems may not be standardized, resulting in content and accuracy that vary among providers.22 These systems may fail to identify critical elements of a patient's condition, promoting ineffective communication and placing the patient at increased risk of adverse events.7, 13, 23

These observations underscore the need for a standardized patient‐tracking instrument that can distill crucial patient information, enhance communication, support transfers, improve efficiency, and enhance continuity of patient care.

We aimed to develop an integrated, problem‐based patient‐tracking tool as part of our hospital's EMR. The tool, SynopSIS, supports patient tracking, transfers of care (ie, sign‐outs), and daily rounds.

METHODS

Setting

The study took place at a 547‐bed adult and pediatric tertiary‐care university‐based teaching hospital with 2 campuses at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center (UCSFMC).

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Development and Design

A multidisciplinary team of practicing residents and attending physicians, information technology leaders, software engineers, and experts in medical communication and sign‐out developed the SynopSIS tool. We reviewed the literature to incorporate key design elements of other successfully implemented information transfer systems.24, 25

We conducted a formal review of existing patient‐tracking and sign‐out systems at our hospital to characterize provider work practices, with an emphasis on the specific information requirements of different specialties. A needs assessment of current sign‐out processes at UCSFMC was conducted by personal interviews with a chief resident or representative of each of the 18 Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited residency programs through the dean's office of Graduate Medical Education. This needs assessment revealed that the majority of the programs did not have a standardized mechanism for sign‐out. Although most did use a written format for sign‐out, the actual type of written format varied from handwritten cards to databases using a variety of programs including Filemaker Pro, Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft Word. When asked what could improve the sign‐out system for their program, they most often responded that it would be having a standardized computerized sign‐out system in the hospital.26

During the design and pilot phase, we presented each SynopSIS function to an advisory committee of more than 50 trainees in medical, surgical, and pediatric general and subspecialty fields. Their input shaped the information content and presentation of our tool. In addition, we discussed the tool with the attending‐physician advisory group that oversees the implementation of clinical information systems in our hospital system.

Conceptual Model

We developed this conceptual model by integrating existing scholarship and input from stakeholders at our institution. First, we reviewed existing literature on documentation and transfers of care. Next, we conducted several focus group sessions with our EMR Residents' Advisory Group to conceptualize work flow and handoff needs for hospital physicians across specialties. We arrived at this model after several iterations of feedback from providers.

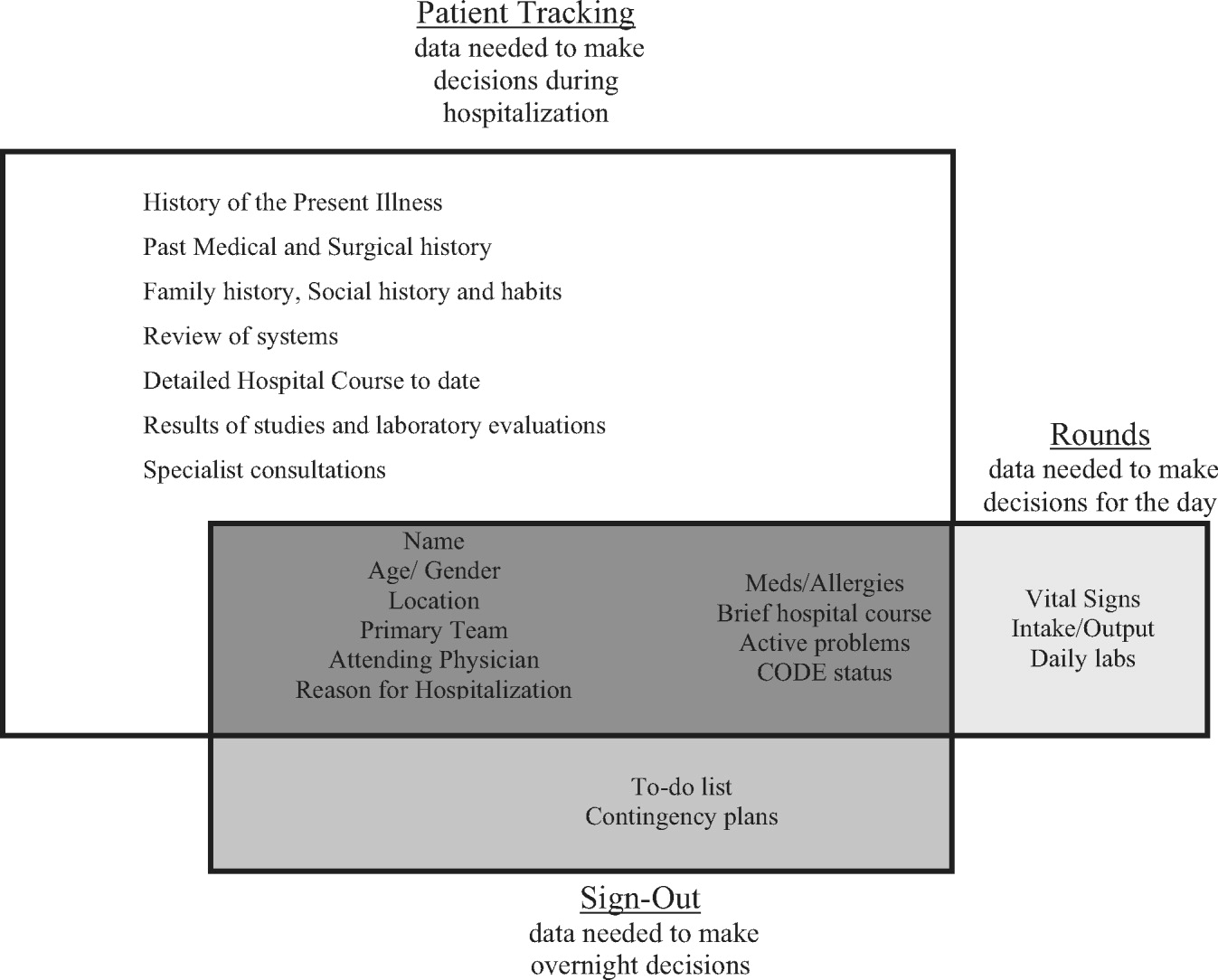

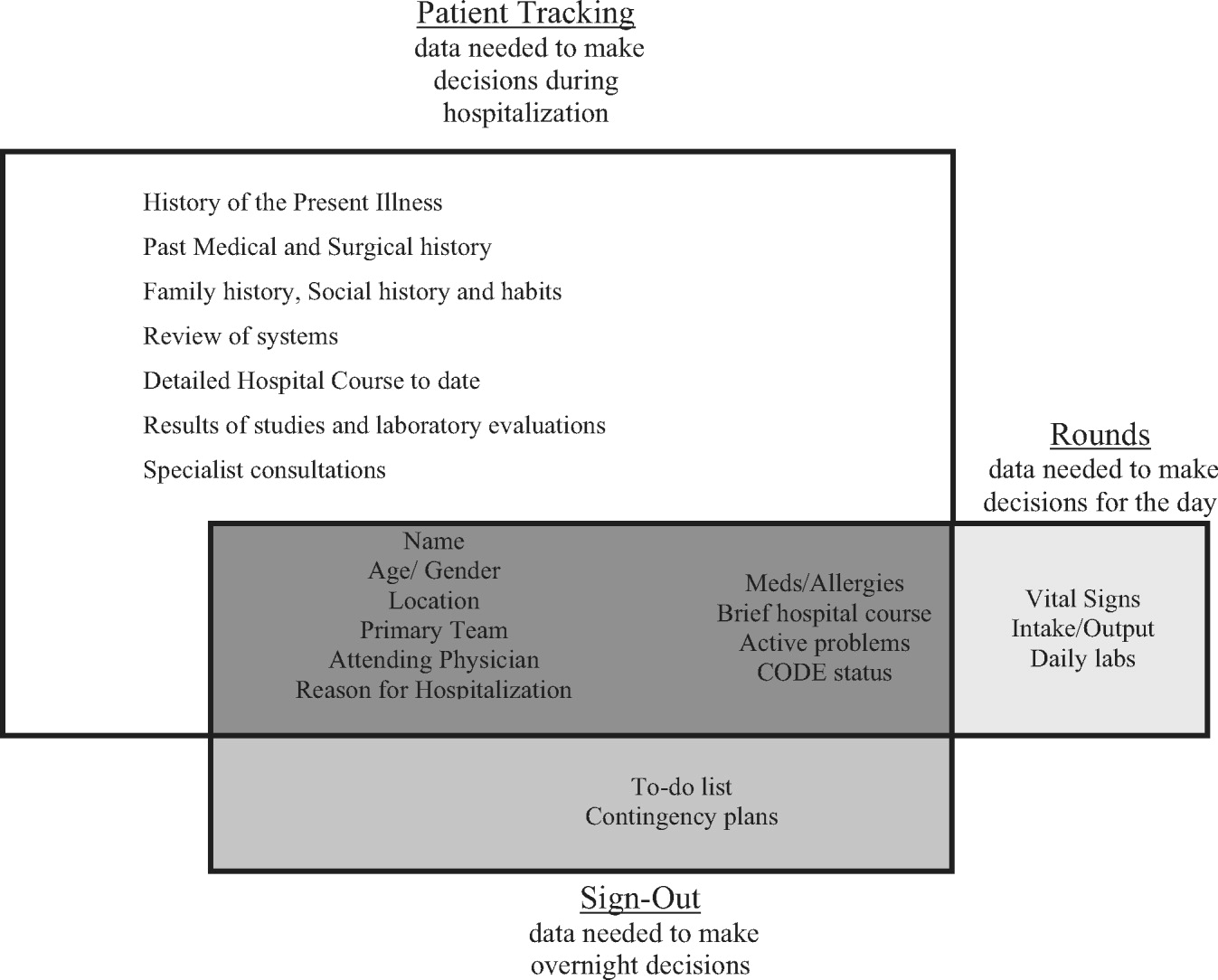

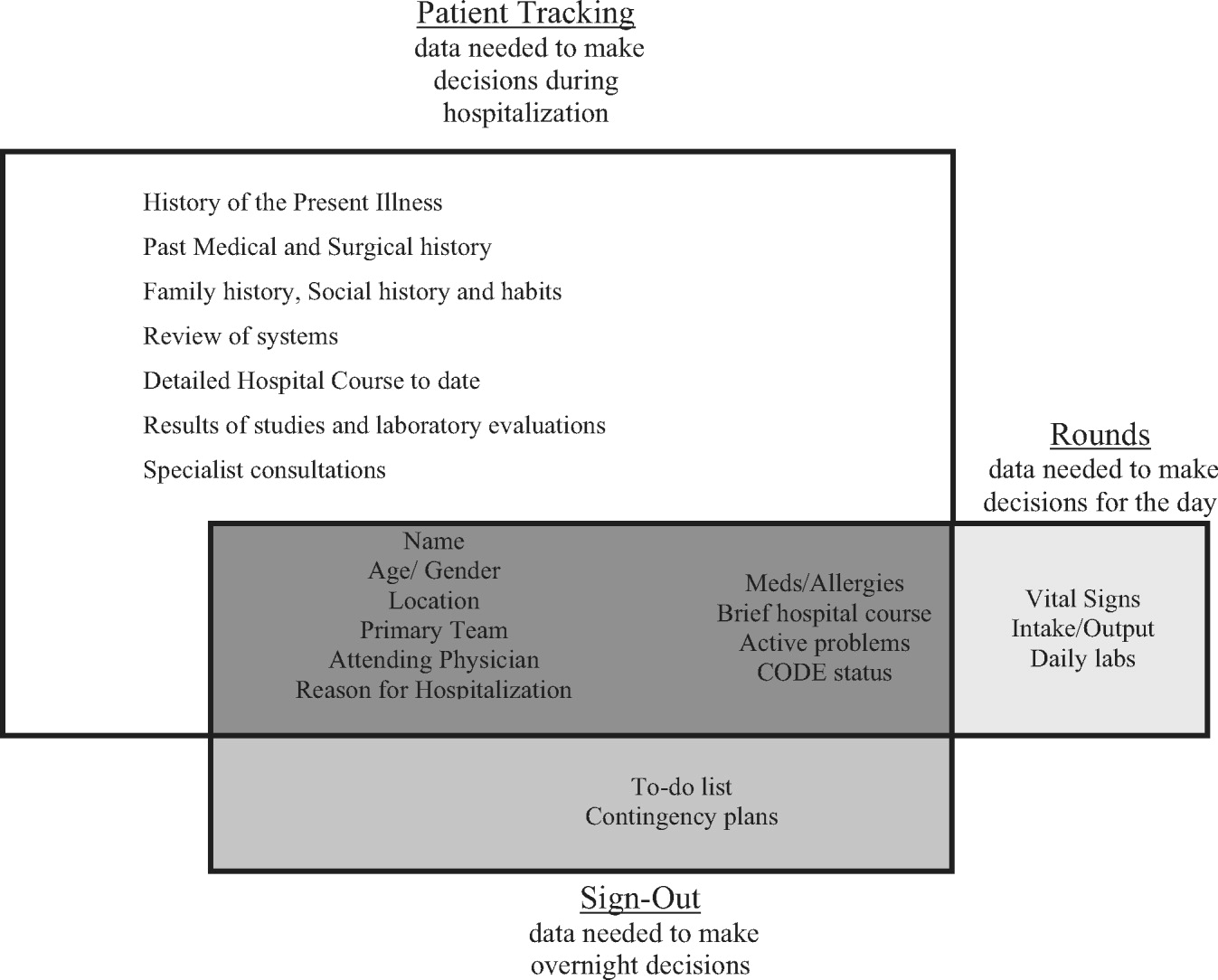

SynopSIS maps patient data available in the EMR to each of the 3 main functions according to type of clinical decisions supported by that function (Fig. 1). For example, data needed for effective patient tracking, such as likely functional status, are required to make decisions over the course of a patient's hospitalization. Similarly, data needed for sign‐out are used to make decisions over the course of a shift, typically overnight; and data needed for morning rounds are used to make decisions for the day. Although the information required for each function overlaps considerably, there are specialized data elements unique to each function.

Description of Functionality

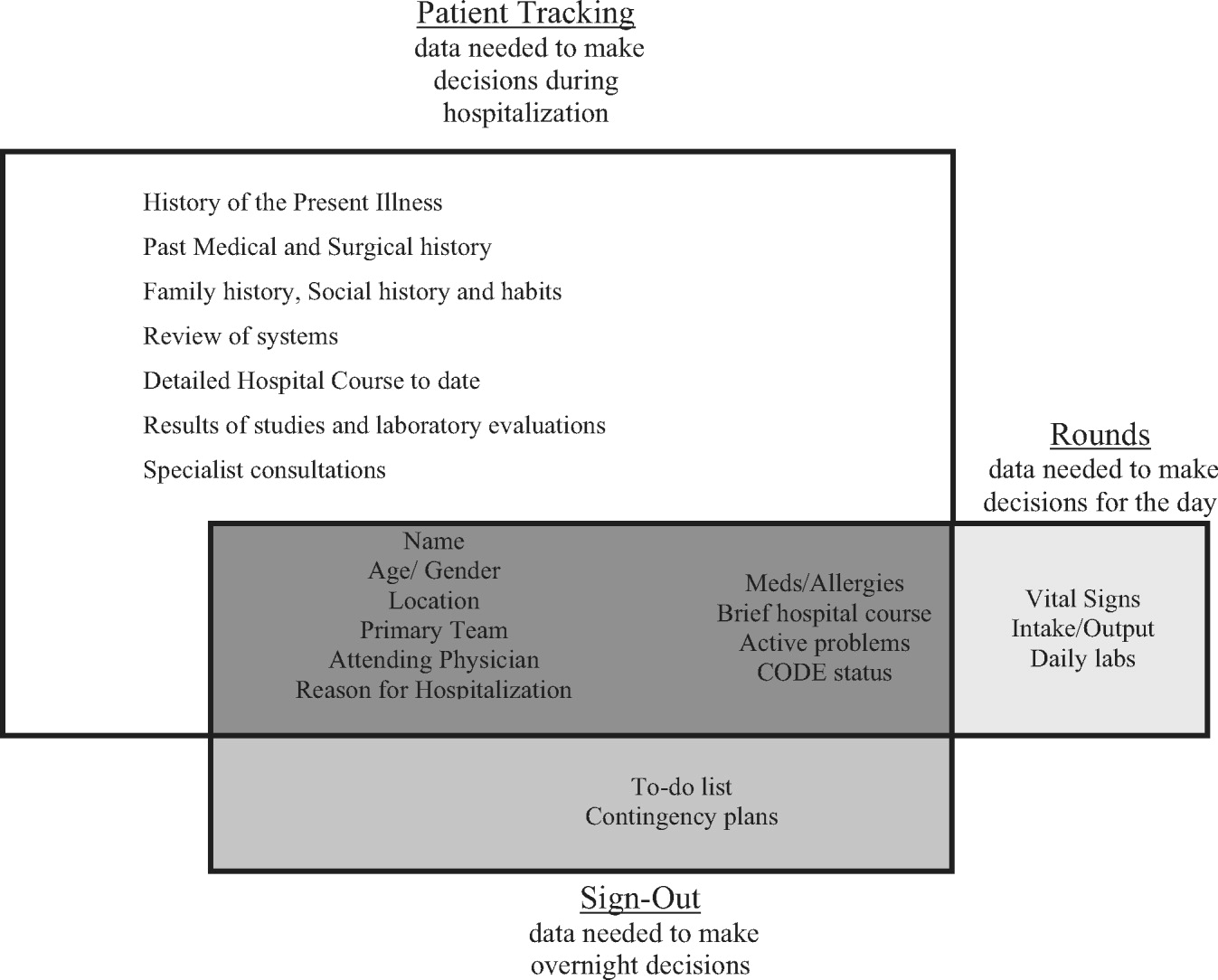

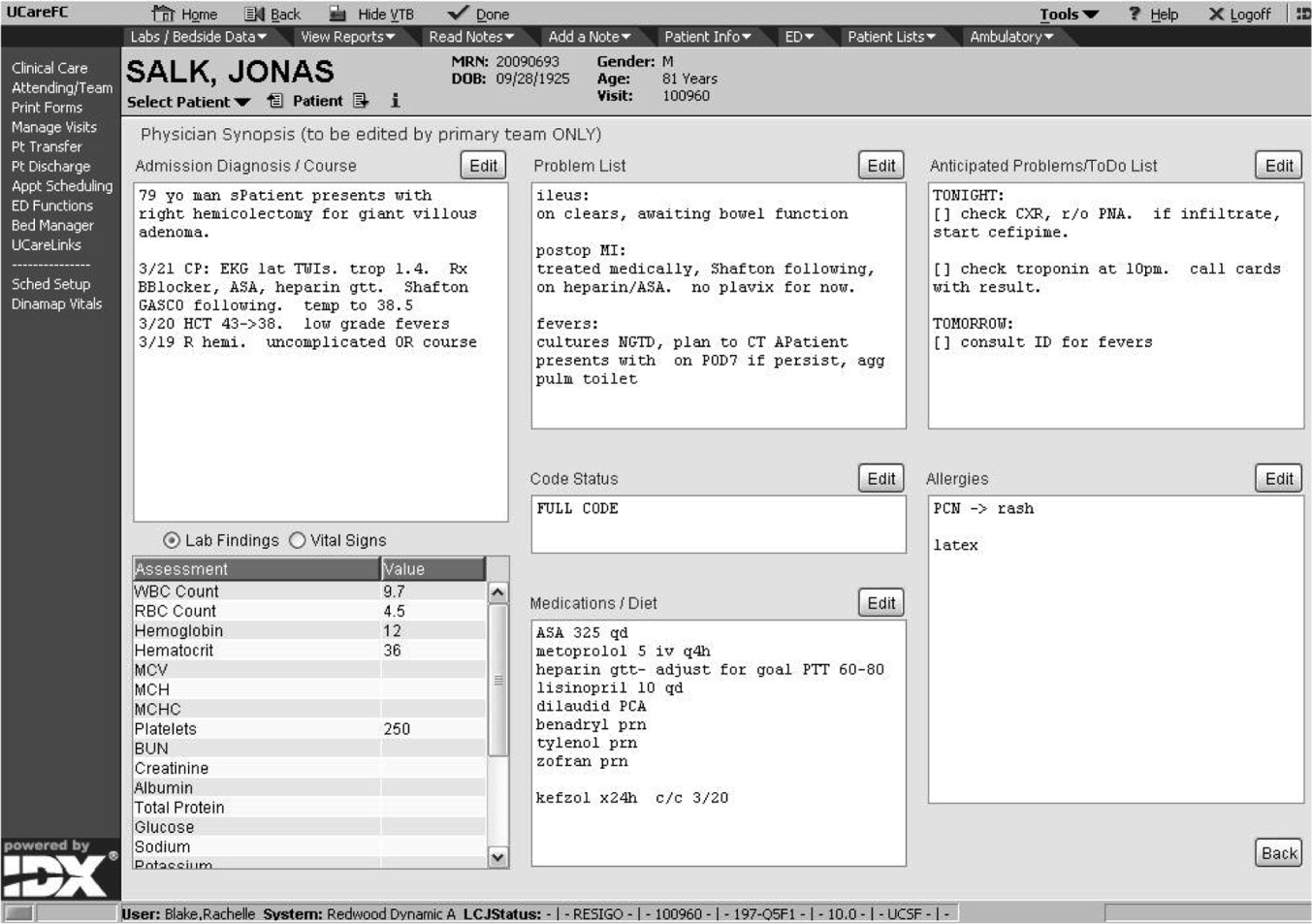

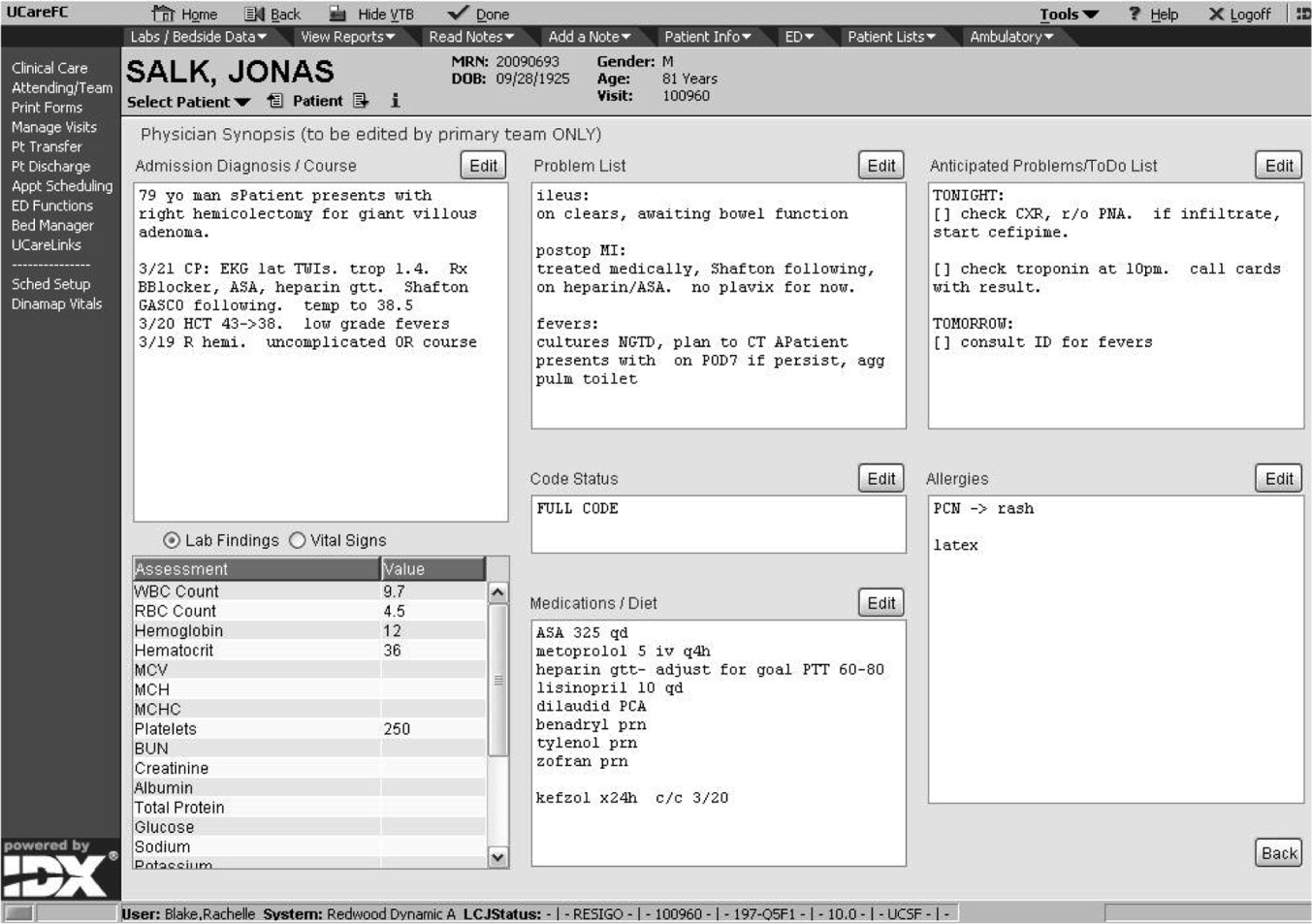

SynopSIS is integrated with our hospital's EMR, General Electric (GE) Centricity Enterprise. The physician interface for SynopSIS is shown in Figure 2. After selecting a patient from a list corresponding to a given inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B), the user selects the menu option to view the SynopSIS screen, which provides an at a glance overview of the patient's current condition. Different fields on the screen support each of SynopSIS's 3 main functions. At the top, the patient's demographic and registration information is displayed, including name, location, age, medical record number, and attending physician. Below are fields viewable and editable by users of the EMR. The Admission Diagnosis/Course and Problem List fields support patient tracking and allow a receiving physician to understand the reason for the patient's admission, the overall course of the illness, and the current active problems. The problem list is entered by the primary hospital physician. The Anticipated Problems/To Do List field supports the sign‐out function from which providers can coordinate care‐related activities and make contingency plans for anticipated events. The patients' most recent laboratory results and vital signs are displayed on the lower left of the screen for easy reference during face‐to‐face physician sign‐outs. Finally, the CODE status, Allergies, and Medications fields allow efficient tracking of information. Temporarily, until the pharmacy component of the EMR goes into use, the primary hospital physician will enter and update the medications. When the pharmacy is linked to the EMR, medications will be added directly from the inpatient pharmacy records to the EMR‐linked sign‐out tool.

This on‐screen SynopSIS view is distinct from the summary screen typically seen in EMRs, including vendor‐based and the Veterans' Affairs systems. For instance, the Veterans' Affairs summary screen incorporates clinical and nonclinical data, including demographic and payment information, upcoming appointments, and patient‐specific information such as allergies. Moreover, it is not editable by primary hospital physicians. Unlike a summary screen, which collates select patient information from other parts of the EMR, SynopSIS is specific to the current acute hospitalization and includes information not found elsewhere in the medical record.

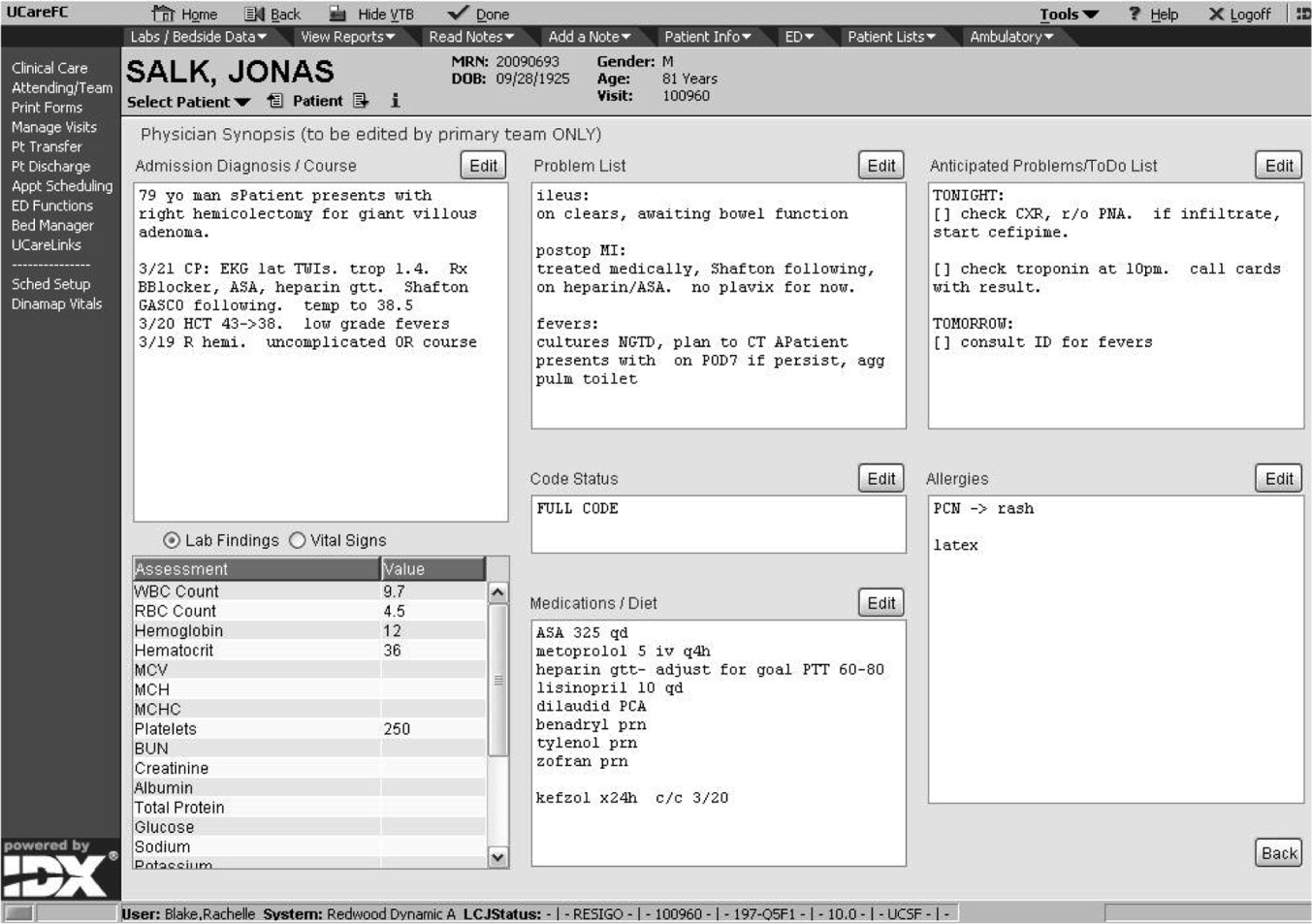

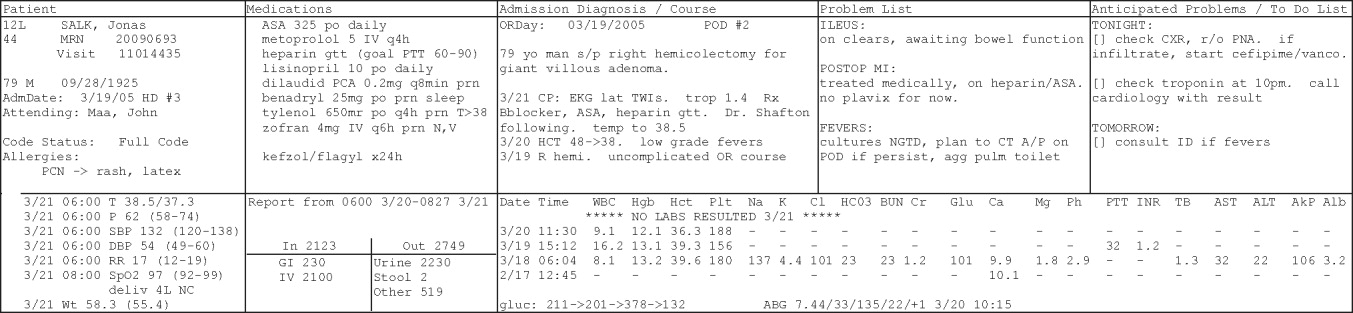

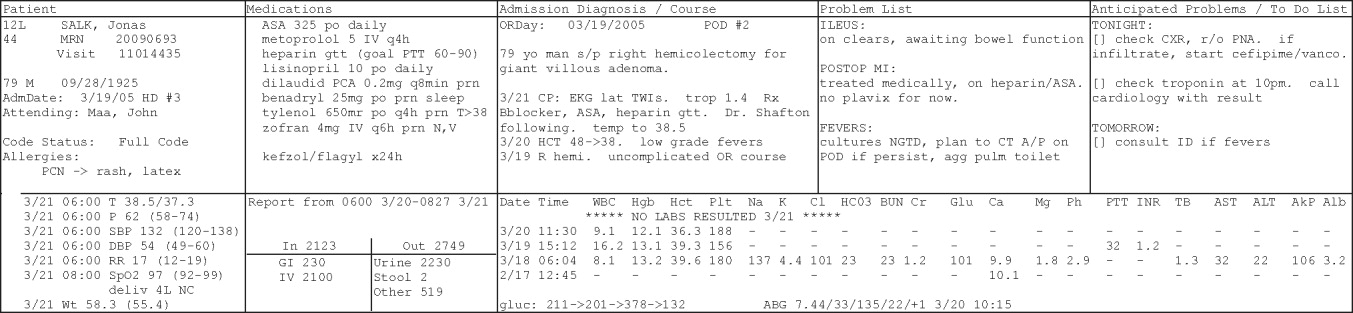

To support rounding, SynopSIS gathers and presents data from the EMR in a printed Rounds Report (Fig. 3). The report is generated for all patients assigned to an inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B) and emphasizes clarity and brevity using a format validated in the medical literature.24, 25 Each patient's report covers one fourth of a standard 8‐by‐11‐inch landscape‐printed page. The top half of each of these quarter‐page patient reports displays data stored in SynopSIS's interface and summarizes the patient's illness and the course of that illness. The lower half displays vital signs, intake/output, and laboratory data over the 24 hours from the time of printing. The most recent value and the range over the previous 24 hours of all vital signs are displayed. Intake/output totals are listed together with a structured breakdown. Laboratory results for the past 24 hours are listed with the most immediate prior values, allowing providers to discern trends. We envision providers obtaining a rounds report on arrival each day before examining their patients.

Importantly, although SynopSIS is part of the patient's medical record, physician users may change or overwrite the data in any field. This ability is a critical feature of the toolthe focus is on providing an interpretable snapshot of the patient. Data may be removed as their importance lessens or as the patient's condition changes, which contrasts with unchangeable documentation geared for alternative purposes, such as billing or medical‐legal requirements. Deleted data are saved in the medical record and are viewable by audit.

Program Evaluation

We have planned a postimplementation evaluation for SynopSIS. Each of the 3 functions (patient tracking, rounding, and care transitions) will be assessed separately. We will explore rounding efficiency and quality by survey and through direct observation. We plan to assess the percentage of time spent on direct patient care versus gathering patient data during morning rounds. We adapted elements of SynopSIS from UWCores, an existing sign‐out application in place at the University of Washington.24, 25 In a randomized trial, UWCores was shown to improve indicators of quality of care (more time spent with patients on rounds, fewer patients missed on rounds) and rounding efficiency (less time prerounding and rounding).25 For evaluation, we plan to use a previously published instrument25 in an online survey of SynopSIS users to assess perceived changes in the quality of sign‐out, providerprovider communication, and patient continuity of care. We intend to measure daily use of SynopSIS by primary providers, covering providers, and consulting physicians in order to assess its impact on each patient's care plan. We hypothesize that primary hospital physicians will access SynopSIS at least 3 times daily: on arrival at the hospital, after rounding, and prior to handoffs. We also plan to investigate whether consulting physicians will view SynopSIS daily rather than obtaining patient data such as labs and vital signs from separate parts of the EMR. Finally, we hypothesize that SynopSIS may facilitate initiation of appropriate discharge planning earlier in a patient's hospital course because it is viewable by nursing, care management, and social work personnel. Importantly, we will implement SynopSIS after the EMR gains universal use at our hospital. We will then wait for a washout following the EMR implementation in order to avoid confounding with the effects of the EMR. We will then be able to separate the effects of this tool from the effects of the EMR. Our EMR does not offer a function comparable to the rounds report or sign‐out tool in SynopSIS.

In addition to this quantitative evaluation process, we plan to solicit feedback from SynopSIS users in focus groups, including physicians at all levels of training as well as nonphysicians. We will use this information to revise SynopSIS according to the users' needs and to tailor the application to diverse specialty services.

DISCUSSION

Several systems have been developed to enhance communication among providers and to support the transfer of care of hospitalized patients.13, 14, 16, 19, 24, 25 We have developed a tool to support patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding that incorporates key elements of previously designed systems and may improve communication among providers. SynopSIS helps to fulfill the 2006 JCAHO accreditation requirement for standardized communication for transfers of care when used with appropriate verbal communication, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions.5 Research from other safety‐oriented industries recommends standardized information transfer, which SynopSIS will provide.20 What is innovative about SynopSIS is that it is not a stand‐alone system, but an integrated part of the EMR.

Currently, fewer than 5% of hospitals have an electronic sign‐out tool linked to hospital information systems27; therefore, SynopSIS has great potential for dissemination. In technical terms, this tool was coded by GE and could be readily adopted by any other GE Centricity Enterprise customer. Moreover, the conceptual model, the design strategy, and the critical system elements should be relevant to effective patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding across different IT platforms.

Despite its strengths, the SynopSIS system has several limitations. First, appropriate transfer of care is a learned process that incorporates well‐described provider and system elements.15, 21, 2830 This tool cannot perform sign‐out; it makes up one part of an effective sign‐out process. As our institution implements SynopSIS, we will also proceed with educational efforts and infrastructure to improve the sign‐out process. Second, although data can be overwritten, prior screen versions are archived in the database. Because SynopSIS is part of the medical record, users may omit sensitive or clinically useful information because of medical‐legal concerns, such as sensitive family dynamics or patient behavioral issues that providers may be reluctant to document in the patient chart. Currently, such information is conveyed verbally during sign‐out. Third, as information gathering and transfer become more automated, informal person‐to‐person interactions among providers (eg, physicians and nurses) may erode. However, we expect that SynopSIS actually will enhance the quality of this communication because it places them on the same page. Finally, SynopSIS generates paper reports that must be disposed of in accordance with standards of patient confidentiality.

We believe that SynopSIS will improve the quality of care through several mechanisms. Because this single‐screen summary will be available to all members of a patients' care team, it is possible that SynopSIS will enable providers to share management plans more readily. Although nursing and care management do not use SynopSIS for their own handoffs, they have clamored for the ability to view it. In addition, rotating providers can readily assume care of an unfamiliar patient. By automating data‐gathering tasks, SynopSIS may foster efficiency and increase time with patients during rounds. For trainee providers in particular, such increased efficiency should allow more time for education and alleviate some of the pressures of duty‐hour compliance. Most important, SynopSIS frees the EMR from emulating the historic paper chart as its method of supporting clinical work flow and communication. That paradigm does not harness the power of today's EMR databases and integration capabilities31 and creates extra work through interruptive work flow and redundant effort.32 With SynopSIS reengineering, instead of providers having to serve the needs of the chart, the chart serves the needs of providers and patients.

Future clinical documentation and EMR systems should focus on provider work flow to improve quality and efficiency in patient care. Moreover, involving providers, including residents, in system design fosters innovation and optimally applies information technology to supporting clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Harry Wong, Chutima Assapimonwait, and Vern Rogers for programming the application. Deborah G. Airo edited the manuscript.

- ,,.Crew resource managment and its applications in medicine. Making health care safer: A critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evidence report/technology assessment2001. AHRQ publication 01‐E058(43).

- ,.Internal Bleeding: The Truth behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes.New York, NY:Rugged Land;2004.

- ,,.New requirements for resident duty hours.JAMA.2002;288:1112–1124.

- ,,,.The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care.JAMA.1993;269:374–378.

- Joint Commission 2006 National Patient Safety Goals Implementation Expectations.2005. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/patient+safety/06_npsg_ie.pdf.

- ,,.Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety.BMJ.2000;320:791–794.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121:866–872.

- .The problem‐oriented record—its organizing principles and its structure.League Exch.1975 (103):3–6.

- .The problem oriented record as a basic tool in medical education, patient care and clinical research.Ann Clin Res.1971;3(3):131–134.

- .Medical records, patient care, and medical education.Ir J Med Sci.1964;17:271–282.

- ,,, et al.Creating a note classification scheme for a multi‐institutional electronic medical record.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2003:968.

- ,,,,,.Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:300–309.

- ,,,,.Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1998;24(2):77–87.

- ,.Signing out patients for off‐hours coverage: comparison of manual and computer‐aided methods.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1992:114–118.

- ,,,,.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1:257–266.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,.The potential role of IT in supporting the work of junior doctors.J R Coll Physicians Lond.2000;34:366–370.

- ,,,.Electronic Sign‐out using a personal digital assistant.Psychiatr Serv.2001;52(2):173–174.

- .“Doctor's notes”: a computerized method for managing inpatient care.Fam Med.1988;20:223–224.

- ,,,,.Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations.Int J Qual Health Care.2004;16(2):125–132.

- ,,, et al.Understanding patient‐centered care in the context of total quality management and continuous quality improvement.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1994;20(3):152–161.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,,.Post‐call transfer of resident responsibility: its effect on patient care.J Gen Intern Med.1990;5:501–505.

- ,,,.Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system.Surgery.2004;136(1):5–13.

- ,,,,.A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours.J Am Coll Surg.2005;200:538–545.

- .UCSFMC sign‐out needs assessment [personal communication].2007.

- ,.Is 80 the cost of saving lives? Reduced duty hours, errors, and cost.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20:969–970.

- ,,.Intern curriculum: the impact of a focused training program on the process and content of sign‐out out patients. Harvard Medical School Education Day2004.

- .When conversation is better than computation.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7:277–286.

- ,.Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study.BMJ.1998;316:673–676.

- ,,,.Integration and beyond: linking information from disparate sources and into workflow.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7(2):135–145.

- .Update on the electronic medical record.Otolaryngol Clin North Am.2002;35:1223–1236, vii.

The delivery of safe, high‐quality care to hospitalized patients depends on effective communication among providers.1, 2 Inpatients may receive care from a number of specialists in addition to their primary hospital physicians, and each provider may practice in a group that transfers care of individual patients among its members. This issue is exacerbated in teaching hospitals because fellows, residents, and interns make frequent transfers of care because of work‐hour rules.3, 4 Finally, teams of physician providers making management decisions must effectively communicate with other members of the care team, such as nurses, dieticians, and social workers, who also may be part of a group practice involving transfers. A patient hospitalized for just a few days in a modern hospital may receive care from dozens of providers and be the subject of multiple transfers of care, or handoffs, that require effective communication. Therefore, as part of its 2006 National Patient Safety Goals,5 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) now requires that each hospital implement a standardized, structured approach to transfers of care.

Transfers of care have been shown to be a source of medical errors and adverse patient outcomes.2, 6, 7 In many cases, the critical information necessary to avert medical errors exists but is not available in real time to providers.6

Traditionally, provider teams have relied on the patient chart, in concert with direct patient evaluation, to provide the information to guide decision making during a hospitalization. Unfortunately, the structure of the chart in most hospitals has evolved little over the past 80 years810 and remains organized so that information is more easily filed than retrieved, read, or summarized.811 Typically, electronic medical records (EMRs) mimic the appearance of paper records and include similar organizational flaws.12 As a result, many providers have created ad hoc informational systems, separate from the chart, designed to track a patient's progress over time and to facilitate transfers of care. These sign‐out systems, which are intended to complement verbal sign‐out between providers,1315 range in complexity from simple handwritten index cards16 to adapted spreadsheets, PDA systems,17, 18 and more complex data systems (eg, FileMaker Pro)19 and often contain crucial information not found elsewhere in the medical record.20, 21

Although sign‐out systems are crucial to patient safety, they have several drawbacks. First, ad‐hoc informational systems may not be standardized, resulting in content and accuracy that vary among providers.22 These systems may fail to identify critical elements of a patient's condition, promoting ineffective communication and placing the patient at increased risk of adverse events.7, 13, 23

These observations underscore the need for a standardized patient‐tracking instrument that can distill crucial patient information, enhance communication, support transfers, improve efficiency, and enhance continuity of patient care.

We aimed to develop an integrated, problem‐based patient‐tracking tool as part of our hospital's EMR. The tool, SynopSIS, supports patient tracking, transfers of care (ie, sign‐outs), and daily rounds.

METHODS

Setting

The study took place at a 547‐bed adult and pediatric tertiary‐care university‐based teaching hospital with 2 campuses at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center (UCSFMC).

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Development and Design

A multidisciplinary team of practicing residents and attending physicians, information technology leaders, software engineers, and experts in medical communication and sign‐out developed the SynopSIS tool. We reviewed the literature to incorporate key design elements of other successfully implemented information transfer systems.24, 25

We conducted a formal review of existing patient‐tracking and sign‐out systems at our hospital to characterize provider work practices, with an emphasis on the specific information requirements of different specialties. A needs assessment of current sign‐out processes at UCSFMC was conducted by personal interviews with a chief resident or representative of each of the 18 Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited residency programs through the dean's office of Graduate Medical Education. This needs assessment revealed that the majority of the programs did not have a standardized mechanism for sign‐out. Although most did use a written format for sign‐out, the actual type of written format varied from handwritten cards to databases using a variety of programs including Filemaker Pro, Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft Word. When asked what could improve the sign‐out system for their program, they most often responded that it would be having a standardized computerized sign‐out system in the hospital.26

During the design and pilot phase, we presented each SynopSIS function to an advisory committee of more than 50 trainees in medical, surgical, and pediatric general and subspecialty fields. Their input shaped the information content and presentation of our tool. In addition, we discussed the tool with the attending‐physician advisory group that oversees the implementation of clinical information systems in our hospital system.

Conceptual Model

We developed this conceptual model by integrating existing scholarship and input from stakeholders at our institution. First, we reviewed existing literature on documentation and transfers of care. Next, we conducted several focus group sessions with our EMR Residents' Advisory Group to conceptualize work flow and handoff needs for hospital physicians across specialties. We arrived at this model after several iterations of feedback from providers.

SynopSIS maps patient data available in the EMR to each of the 3 main functions according to type of clinical decisions supported by that function (Fig. 1). For example, data needed for effective patient tracking, such as likely functional status, are required to make decisions over the course of a patient's hospitalization. Similarly, data needed for sign‐out are used to make decisions over the course of a shift, typically overnight; and data needed for morning rounds are used to make decisions for the day. Although the information required for each function overlaps considerably, there are specialized data elements unique to each function.

Description of Functionality

SynopSIS is integrated with our hospital's EMR, General Electric (GE) Centricity Enterprise. The physician interface for SynopSIS is shown in Figure 2. After selecting a patient from a list corresponding to a given inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B), the user selects the menu option to view the SynopSIS screen, which provides an at a glance overview of the patient's current condition. Different fields on the screen support each of SynopSIS's 3 main functions. At the top, the patient's demographic and registration information is displayed, including name, location, age, medical record number, and attending physician. Below are fields viewable and editable by users of the EMR. The Admission Diagnosis/Course and Problem List fields support patient tracking and allow a receiving physician to understand the reason for the patient's admission, the overall course of the illness, and the current active problems. The problem list is entered by the primary hospital physician. The Anticipated Problems/To Do List field supports the sign‐out function from which providers can coordinate care‐related activities and make contingency plans for anticipated events. The patients' most recent laboratory results and vital signs are displayed on the lower left of the screen for easy reference during face‐to‐face physician sign‐outs. Finally, the CODE status, Allergies, and Medications fields allow efficient tracking of information. Temporarily, until the pharmacy component of the EMR goes into use, the primary hospital physician will enter and update the medications. When the pharmacy is linked to the EMR, medications will be added directly from the inpatient pharmacy records to the EMR‐linked sign‐out tool.

This on‐screen SynopSIS view is distinct from the summary screen typically seen in EMRs, including vendor‐based and the Veterans' Affairs systems. For instance, the Veterans' Affairs summary screen incorporates clinical and nonclinical data, including demographic and payment information, upcoming appointments, and patient‐specific information such as allergies. Moreover, it is not editable by primary hospital physicians. Unlike a summary screen, which collates select patient information from other parts of the EMR, SynopSIS is specific to the current acute hospitalization and includes information not found elsewhere in the medical record.

To support rounding, SynopSIS gathers and presents data from the EMR in a printed Rounds Report (Fig. 3). The report is generated for all patients assigned to an inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B) and emphasizes clarity and brevity using a format validated in the medical literature.24, 25 Each patient's report covers one fourth of a standard 8‐by‐11‐inch landscape‐printed page. The top half of each of these quarter‐page patient reports displays data stored in SynopSIS's interface and summarizes the patient's illness and the course of that illness. The lower half displays vital signs, intake/output, and laboratory data over the 24 hours from the time of printing. The most recent value and the range over the previous 24 hours of all vital signs are displayed. Intake/output totals are listed together with a structured breakdown. Laboratory results for the past 24 hours are listed with the most immediate prior values, allowing providers to discern trends. We envision providers obtaining a rounds report on arrival each day before examining their patients.

Importantly, although SynopSIS is part of the patient's medical record, physician users may change or overwrite the data in any field. This ability is a critical feature of the toolthe focus is on providing an interpretable snapshot of the patient. Data may be removed as their importance lessens or as the patient's condition changes, which contrasts with unchangeable documentation geared for alternative purposes, such as billing or medical‐legal requirements. Deleted data are saved in the medical record and are viewable by audit.

Program Evaluation

We have planned a postimplementation evaluation for SynopSIS. Each of the 3 functions (patient tracking, rounding, and care transitions) will be assessed separately. We will explore rounding efficiency and quality by survey and through direct observation. We plan to assess the percentage of time spent on direct patient care versus gathering patient data during morning rounds. We adapted elements of SynopSIS from UWCores, an existing sign‐out application in place at the University of Washington.24, 25 In a randomized trial, UWCores was shown to improve indicators of quality of care (more time spent with patients on rounds, fewer patients missed on rounds) and rounding efficiency (less time prerounding and rounding).25 For evaluation, we plan to use a previously published instrument25 in an online survey of SynopSIS users to assess perceived changes in the quality of sign‐out, providerprovider communication, and patient continuity of care. We intend to measure daily use of SynopSIS by primary providers, covering providers, and consulting physicians in order to assess its impact on each patient's care plan. We hypothesize that primary hospital physicians will access SynopSIS at least 3 times daily: on arrival at the hospital, after rounding, and prior to handoffs. We also plan to investigate whether consulting physicians will view SynopSIS daily rather than obtaining patient data such as labs and vital signs from separate parts of the EMR. Finally, we hypothesize that SynopSIS may facilitate initiation of appropriate discharge planning earlier in a patient's hospital course because it is viewable by nursing, care management, and social work personnel. Importantly, we will implement SynopSIS after the EMR gains universal use at our hospital. We will then wait for a washout following the EMR implementation in order to avoid confounding with the effects of the EMR. We will then be able to separate the effects of this tool from the effects of the EMR. Our EMR does not offer a function comparable to the rounds report or sign‐out tool in SynopSIS.

In addition to this quantitative evaluation process, we plan to solicit feedback from SynopSIS users in focus groups, including physicians at all levels of training as well as nonphysicians. We will use this information to revise SynopSIS according to the users' needs and to tailor the application to diverse specialty services.

DISCUSSION

Several systems have been developed to enhance communication among providers and to support the transfer of care of hospitalized patients.13, 14, 16, 19, 24, 25 We have developed a tool to support patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding that incorporates key elements of previously designed systems and may improve communication among providers. SynopSIS helps to fulfill the 2006 JCAHO accreditation requirement for standardized communication for transfers of care when used with appropriate verbal communication, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions.5 Research from other safety‐oriented industries recommends standardized information transfer, which SynopSIS will provide.20 What is innovative about SynopSIS is that it is not a stand‐alone system, but an integrated part of the EMR.

Currently, fewer than 5% of hospitals have an electronic sign‐out tool linked to hospital information systems27; therefore, SynopSIS has great potential for dissemination. In technical terms, this tool was coded by GE and could be readily adopted by any other GE Centricity Enterprise customer. Moreover, the conceptual model, the design strategy, and the critical system elements should be relevant to effective patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding across different IT platforms.

Despite its strengths, the SynopSIS system has several limitations. First, appropriate transfer of care is a learned process that incorporates well‐described provider and system elements.15, 21, 2830 This tool cannot perform sign‐out; it makes up one part of an effective sign‐out process. As our institution implements SynopSIS, we will also proceed with educational efforts and infrastructure to improve the sign‐out process. Second, although data can be overwritten, prior screen versions are archived in the database. Because SynopSIS is part of the medical record, users may omit sensitive or clinically useful information because of medical‐legal concerns, such as sensitive family dynamics or patient behavioral issues that providers may be reluctant to document in the patient chart. Currently, such information is conveyed verbally during sign‐out. Third, as information gathering and transfer become more automated, informal person‐to‐person interactions among providers (eg, physicians and nurses) may erode. However, we expect that SynopSIS actually will enhance the quality of this communication because it places them on the same page. Finally, SynopSIS generates paper reports that must be disposed of in accordance with standards of patient confidentiality.

We believe that SynopSIS will improve the quality of care through several mechanisms. Because this single‐screen summary will be available to all members of a patients' care team, it is possible that SynopSIS will enable providers to share management plans more readily. Although nursing and care management do not use SynopSIS for their own handoffs, they have clamored for the ability to view it. In addition, rotating providers can readily assume care of an unfamiliar patient. By automating data‐gathering tasks, SynopSIS may foster efficiency and increase time with patients during rounds. For trainee providers in particular, such increased efficiency should allow more time for education and alleviate some of the pressures of duty‐hour compliance. Most important, SynopSIS frees the EMR from emulating the historic paper chart as its method of supporting clinical work flow and communication. That paradigm does not harness the power of today's EMR databases and integration capabilities31 and creates extra work through interruptive work flow and redundant effort.32 With SynopSIS reengineering, instead of providers having to serve the needs of the chart, the chart serves the needs of providers and patients.

Future clinical documentation and EMR systems should focus on provider work flow to improve quality and efficiency in patient care. Moreover, involving providers, including residents, in system design fosters innovation and optimally applies information technology to supporting clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Harry Wong, Chutima Assapimonwait, and Vern Rogers for programming the application. Deborah G. Airo edited the manuscript.

The delivery of safe, high‐quality care to hospitalized patients depends on effective communication among providers.1, 2 Inpatients may receive care from a number of specialists in addition to their primary hospital physicians, and each provider may practice in a group that transfers care of individual patients among its members. This issue is exacerbated in teaching hospitals because fellows, residents, and interns make frequent transfers of care because of work‐hour rules.3, 4 Finally, teams of physician providers making management decisions must effectively communicate with other members of the care team, such as nurses, dieticians, and social workers, who also may be part of a group practice involving transfers. A patient hospitalized for just a few days in a modern hospital may receive care from dozens of providers and be the subject of multiple transfers of care, or handoffs, that require effective communication. Therefore, as part of its 2006 National Patient Safety Goals,5 the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) now requires that each hospital implement a standardized, structured approach to transfers of care.

Transfers of care have been shown to be a source of medical errors and adverse patient outcomes.2, 6, 7 In many cases, the critical information necessary to avert medical errors exists but is not available in real time to providers.6

Traditionally, provider teams have relied on the patient chart, in concert with direct patient evaluation, to provide the information to guide decision making during a hospitalization. Unfortunately, the structure of the chart in most hospitals has evolved little over the past 80 years810 and remains organized so that information is more easily filed than retrieved, read, or summarized.811 Typically, electronic medical records (EMRs) mimic the appearance of paper records and include similar organizational flaws.12 As a result, many providers have created ad hoc informational systems, separate from the chart, designed to track a patient's progress over time and to facilitate transfers of care. These sign‐out systems, which are intended to complement verbal sign‐out between providers,1315 range in complexity from simple handwritten index cards16 to adapted spreadsheets, PDA systems,17, 18 and more complex data systems (eg, FileMaker Pro)19 and often contain crucial information not found elsewhere in the medical record.20, 21

Although sign‐out systems are crucial to patient safety, they have several drawbacks. First, ad‐hoc informational systems may not be standardized, resulting in content and accuracy that vary among providers.22 These systems may fail to identify critical elements of a patient's condition, promoting ineffective communication and placing the patient at increased risk of adverse events.7, 13, 23

These observations underscore the need for a standardized patient‐tracking instrument that can distill crucial patient information, enhance communication, support transfers, improve efficiency, and enhance continuity of patient care.

We aimed to develop an integrated, problem‐based patient‐tracking tool as part of our hospital's EMR. The tool, SynopSIS, supports patient tracking, transfers of care (ie, sign‐outs), and daily rounds.

METHODS

Setting

The study took place at a 547‐bed adult and pediatric tertiary‐care university‐based teaching hospital with 2 campuses at the University of California, San Francisco, Medical Center (UCSFMC).

PROGRAM DESCRIPTION

Development and Design

A multidisciplinary team of practicing residents and attending physicians, information technology leaders, software engineers, and experts in medical communication and sign‐out developed the SynopSIS tool. We reviewed the literature to incorporate key design elements of other successfully implemented information transfer systems.24, 25

We conducted a formal review of existing patient‐tracking and sign‐out systems at our hospital to characterize provider work practices, with an emphasis on the specific information requirements of different specialties. A needs assessment of current sign‐out processes at UCSFMC was conducted by personal interviews with a chief resident or representative of each of the 18 Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) accredited residency programs through the dean's office of Graduate Medical Education. This needs assessment revealed that the majority of the programs did not have a standardized mechanism for sign‐out. Although most did use a written format for sign‐out, the actual type of written format varied from handwritten cards to databases using a variety of programs including Filemaker Pro, Microsoft Excel, and Microsoft Word. When asked what could improve the sign‐out system for their program, they most often responded that it would be having a standardized computerized sign‐out system in the hospital.26

During the design and pilot phase, we presented each SynopSIS function to an advisory committee of more than 50 trainees in medical, surgical, and pediatric general and subspecialty fields. Their input shaped the information content and presentation of our tool. In addition, we discussed the tool with the attending‐physician advisory group that oversees the implementation of clinical information systems in our hospital system.

Conceptual Model

We developed this conceptual model by integrating existing scholarship and input from stakeholders at our institution. First, we reviewed existing literature on documentation and transfers of care. Next, we conducted several focus group sessions with our EMR Residents' Advisory Group to conceptualize work flow and handoff needs for hospital physicians across specialties. We arrived at this model after several iterations of feedback from providers.

SynopSIS maps patient data available in the EMR to each of the 3 main functions according to type of clinical decisions supported by that function (Fig. 1). For example, data needed for effective patient tracking, such as likely functional status, are required to make decisions over the course of a patient's hospitalization. Similarly, data needed for sign‐out are used to make decisions over the course of a shift, typically overnight; and data needed for morning rounds are used to make decisions for the day. Although the information required for each function overlaps considerably, there are specialized data elements unique to each function.

Description of Functionality

SynopSIS is integrated with our hospital's EMR, General Electric (GE) Centricity Enterprise. The physician interface for SynopSIS is shown in Figure 2. After selecting a patient from a list corresponding to a given inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B), the user selects the menu option to view the SynopSIS screen, which provides an at a glance overview of the patient's current condition. Different fields on the screen support each of SynopSIS's 3 main functions. At the top, the patient's demographic and registration information is displayed, including name, location, age, medical record number, and attending physician. Below are fields viewable and editable by users of the EMR. The Admission Diagnosis/Course and Problem List fields support patient tracking and allow a receiving physician to understand the reason for the patient's admission, the overall course of the illness, and the current active problems. The problem list is entered by the primary hospital physician. The Anticipated Problems/To Do List field supports the sign‐out function from which providers can coordinate care‐related activities and make contingency plans for anticipated events. The patients' most recent laboratory results and vital signs are displayed on the lower left of the screen for easy reference during face‐to‐face physician sign‐outs. Finally, the CODE status, Allergies, and Medications fields allow efficient tracking of information. Temporarily, until the pharmacy component of the EMR goes into use, the primary hospital physician will enter and update the medications. When the pharmacy is linked to the EMR, medications will be added directly from the inpatient pharmacy records to the EMR‐linked sign‐out tool.

This on‐screen SynopSIS view is distinct from the summary screen typically seen in EMRs, including vendor‐based and the Veterans' Affairs systems. For instance, the Veterans' Affairs summary screen incorporates clinical and nonclinical data, including demographic and payment information, upcoming appointments, and patient‐specific information such as allergies. Moreover, it is not editable by primary hospital physicians. Unlike a summary screen, which collates select patient information from other parts of the EMR, SynopSIS is specific to the current acute hospitalization and includes information not found elsewhere in the medical record.

To support rounding, SynopSIS gathers and presents data from the EMR in a printed Rounds Report (Fig. 3). The report is generated for all patients assigned to an inpatient service (eg, Medicine Team B) and emphasizes clarity and brevity using a format validated in the medical literature.24, 25 Each patient's report covers one fourth of a standard 8‐by‐11‐inch landscape‐printed page. The top half of each of these quarter‐page patient reports displays data stored in SynopSIS's interface and summarizes the patient's illness and the course of that illness. The lower half displays vital signs, intake/output, and laboratory data over the 24 hours from the time of printing. The most recent value and the range over the previous 24 hours of all vital signs are displayed. Intake/output totals are listed together with a structured breakdown. Laboratory results for the past 24 hours are listed with the most immediate prior values, allowing providers to discern trends. We envision providers obtaining a rounds report on arrival each day before examining their patients.

Importantly, although SynopSIS is part of the patient's medical record, physician users may change or overwrite the data in any field. This ability is a critical feature of the toolthe focus is on providing an interpretable snapshot of the patient. Data may be removed as their importance lessens or as the patient's condition changes, which contrasts with unchangeable documentation geared for alternative purposes, such as billing or medical‐legal requirements. Deleted data are saved in the medical record and are viewable by audit.

Program Evaluation

We have planned a postimplementation evaluation for SynopSIS. Each of the 3 functions (patient tracking, rounding, and care transitions) will be assessed separately. We will explore rounding efficiency and quality by survey and through direct observation. We plan to assess the percentage of time spent on direct patient care versus gathering patient data during morning rounds. We adapted elements of SynopSIS from UWCores, an existing sign‐out application in place at the University of Washington.24, 25 In a randomized trial, UWCores was shown to improve indicators of quality of care (more time spent with patients on rounds, fewer patients missed on rounds) and rounding efficiency (less time prerounding and rounding).25 For evaluation, we plan to use a previously published instrument25 in an online survey of SynopSIS users to assess perceived changes in the quality of sign‐out, providerprovider communication, and patient continuity of care. We intend to measure daily use of SynopSIS by primary providers, covering providers, and consulting physicians in order to assess its impact on each patient's care plan. We hypothesize that primary hospital physicians will access SynopSIS at least 3 times daily: on arrival at the hospital, after rounding, and prior to handoffs. We also plan to investigate whether consulting physicians will view SynopSIS daily rather than obtaining patient data such as labs and vital signs from separate parts of the EMR. Finally, we hypothesize that SynopSIS may facilitate initiation of appropriate discharge planning earlier in a patient's hospital course because it is viewable by nursing, care management, and social work personnel. Importantly, we will implement SynopSIS after the EMR gains universal use at our hospital. We will then wait for a washout following the EMR implementation in order to avoid confounding with the effects of the EMR. We will then be able to separate the effects of this tool from the effects of the EMR. Our EMR does not offer a function comparable to the rounds report or sign‐out tool in SynopSIS.

In addition to this quantitative evaluation process, we plan to solicit feedback from SynopSIS users in focus groups, including physicians at all levels of training as well as nonphysicians. We will use this information to revise SynopSIS according to the users' needs and to tailor the application to diverse specialty services.

DISCUSSION

Several systems have been developed to enhance communication among providers and to support the transfer of care of hospitalized patients.13, 14, 16, 19, 24, 25 We have developed a tool to support patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding that incorporates key elements of previously designed systems and may improve communication among providers. SynopSIS helps to fulfill the 2006 JCAHO accreditation requirement for standardized communication for transfers of care when used with appropriate verbal communication, including an opportunity to ask and respond to questions.5 Research from other safety‐oriented industries recommends standardized information transfer, which SynopSIS will provide.20 What is innovative about SynopSIS is that it is not a stand‐alone system, but an integrated part of the EMR.

Currently, fewer than 5% of hospitals have an electronic sign‐out tool linked to hospital information systems27; therefore, SynopSIS has great potential for dissemination. In technical terms, this tool was coded by GE and could be readily adopted by any other GE Centricity Enterprise customer. Moreover, the conceptual model, the design strategy, and the critical system elements should be relevant to effective patient tracking, sign‐out, and rounding across different IT platforms.

Despite its strengths, the SynopSIS system has several limitations. First, appropriate transfer of care is a learned process that incorporates well‐described provider and system elements.15, 21, 2830 This tool cannot perform sign‐out; it makes up one part of an effective sign‐out process. As our institution implements SynopSIS, we will also proceed with educational efforts and infrastructure to improve the sign‐out process. Second, although data can be overwritten, prior screen versions are archived in the database. Because SynopSIS is part of the medical record, users may omit sensitive or clinically useful information because of medical‐legal concerns, such as sensitive family dynamics or patient behavioral issues that providers may be reluctant to document in the patient chart. Currently, such information is conveyed verbally during sign‐out. Third, as information gathering and transfer become more automated, informal person‐to‐person interactions among providers (eg, physicians and nurses) may erode. However, we expect that SynopSIS actually will enhance the quality of this communication because it places them on the same page. Finally, SynopSIS generates paper reports that must be disposed of in accordance with standards of patient confidentiality.

We believe that SynopSIS will improve the quality of care through several mechanisms. Because this single‐screen summary will be available to all members of a patients' care team, it is possible that SynopSIS will enable providers to share management plans more readily. Although nursing and care management do not use SynopSIS for their own handoffs, they have clamored for the ability to view it. In addition, rotating providers can readily assume care of an unfamiliar patient. By automating data‐gathering tasks, SynopSIS may foster efficiency and increase time with patients during rounds. For trainee providers in particular, such increased efficiency should allow more time for education and alleviate some of the pressures of duty‐hour compliance. Most important, SynopSIS frees the EMR from emulating the historic paper chart as its method of supporting clinical work flow and communication. That paradigm does not harness the power of today's EMR databases and integration capabilities31 and creates extra work through interruptive work flow and redundant effort.32 With SynopSIS reengineering, instead of providers having to serve the needs of the chart, the chart serves the needs of providers and patients.

Future clinical documentation and EMR systems should focus on provider work flow to improve quality and efficiency in patient care. Moreover, involving providers, including residents, in system design fosters innovation and optimally applies information technology to supporting clinical practice.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Harry Wong, Chutima Assapimonwait, and Vern Rogers for programming the application. Deborah G. Airo edited the manuscript.

- ,,.Crew resource managment and its applications in medicine. Making health care safer: A critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evidence report/technology assessment2001. AHRQ publication 01‐E058(43).

- ,.Internal Bleeding: The Truth behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes.New York, NY:Rugged Land;2004.

- ,,.New requirements for resident duty hours.JAMA.2002;288:1112–1124.

- ,,,.The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care.JAMA.1993;269:374–378.

- Joint Commission 2006 National Patient Safety Goals Implementation Expectations.2005. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/patient+safety/06_npsg_ie.pdf.

- ,,.Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety.BMJ.2000;320:791–794.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121:866–872.

- .The problem‐oriented record—its organizing principles and its structure.League Exch.1975 (103):3–6.

- .The problem oriented record as a basic tool in medical education, patient care and clinical research.Ann Clin Res.1971;3(3):131–134.

- .Medical records, patient care, and medical education.Ir J Med Sci.1964;17:271–282.

- ,,, et al.Creating a note classification scheme for a multi‐institutional electronic medical record.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2003:968.

- ,,,,,.Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:300–309.

- ,,,,.Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1998;24(2):77–87.

- ,.Signing out patients for off‐hours coverage: comparison of manual and computer‐aided methods.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1992:114–118.

- ,,,,.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1:257–266.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,.The potential role of IT in supporting the work of junior doctors.J R Coll Physicians Lond.2000;34:366–370.

- ,,,.Electronic Sign‐out using a personal digital assistant.Psychiatr Serv.2001;52(2):173–174.

- .“Doctor's notes”: a computerized method for managing inpatient care.Fam Med.1988;20:223–224.

- ,,,,.Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations.Int J Qual Health Care.2004;16(2):125–132.

- ,,, et al.Understanding patient‐centered care in the context of total quality management and continuous quality improvement.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1994;20(3):152–161.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,,.Post‐call transfer of resident responsibility: its effect on patient care.J Gen Intern Med.1990;5:501–505.

- ,,,.Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system.Surgery.2004;136(1):5–13.

- ,,,,.A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours.J Am Coll Surg.2005;200:538–545.

- .UCSFMC sign‐out needs assessment [personal communication].2007.

- ,.Is 80 the cost of saving lives? Reduced duty hours, errors, and cost.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20:969–970.

- ,,.Intern curriculum: the impact of a focused training program on the process and content of sign‐out out patients. Harvard Medical School Education Day2004.

- .When conversation is better than computation.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7:277–286.

- ,.Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study.BMJ.1998;316:673–676.

- ,,,.Integration and beyond: linking information from disparate sources and into workflow.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7(2):135–145.

- .Update on the electronic medical record.Otolaryngol Clin North Am.2002;35:1223–1236, vii.

- ,,.Crew resource managment and its applications in medicine. Making health care safer: A critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evidence report/technology assessment2001. AHRQ publication 01‐E058(43).

- ,.Internal Bleeding: The Truth behind America's Terrifying Epidemic of Medical Mistakes.New York, NY:Rugged Land;2004.

- ,,.New requirements for resident duty hours.JAMA.2002;288:1112–1124.

- ,,,.The impact of a regulation restricting medical house staff working hours on the quality of patient care.JAMA.1993;269:374–378.

- Joint Commission 2006 National Patient Safety Goals Implementation Expectations.2005. Available at: http://www.jcaho.org/accredited+organizations/patient+safety/06_npsg_ie.pdf.

- ,,.Gaps in the continuity of care and progress on patient safety.BMJ.2000;320:791–794.

- ,,,,.Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events?Ann Intern Med.1994;121:866–872.

- .The problem‐oriented record—its organizing principles and its structure.League Exch.1975 (103):3–6.

- .The problem oriented record as a basic tool in medical education, patient care and clinical research.Ann Clin Res.1971;3(3):131–134.

- .Medical records, patient care, and medical education.Ir J Med Sci.1964;17:271–282.

- ,,, et al.Creating a note classification scheme for a multi‐institutional electronic medical record.AMIA Annu Symp Proc.2003:968.

- ,,,,,.Impacts of computerized physician documentation in a teaching hospital: perceptions of faculty and resident physicians.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11:300–309.

- ,,,,.Using a computerized sign‐out program to improve continuity of inpatient care and prevent adverse events.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1998;24(2):77–87.

- ,.Signing out patients for off‐hours coverage: comparison of manual and computer‐aided methods.Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care.1992:114–118.

- ,,,,.Managing discontinuity in academic medical centers: strategies for a safe and effective resident sign‐out.J Hosp Med.2006;1:257–266.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,.The potential role of IT in supporting the work of junior doctors.J R Coll Physicians Lond.2000;34:366–370.

- ,,,.Electronic Sign‐out using a personal digital assistant.Psychiatr Serv.2001;52(2):173–174.

- .“Doctor's notes”: a computerized method for managing inpatient care.Fam Med.1988;20:223–224.

- ,,,,.Handoff strategies in settings with high consequences for failure: lessons for health care operations.Int J Qual Health Care.2004;16(2):125–132.

- ,,, et al.Understanding patient‐centered care in the context of total quality management and continuous quality improvement.Jt Comm J Qual Improv.1994;20(3):152–161.

- ,,.Utility of a standardized sign‐out card for new medical interns.J Gen Intern Med.1996;11:753–755.

- ,,,.Post‐call transfer of resident responsibility: its effect on patient care.J Gen Intern Med.1990;5:501–505.

- ,,,.Organizing the transfer of patient care information: the development of a computerized resident sign‐out system.Surgery.2004;136(1):5–13.

- ,,,,.A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours.J Am Coll Surg.2005;200:538–545.

- .UCSFMC sign‐out needs assessment [personal communication].2007.

- ,.Is 80 the cost of saving lives? Reduced duty hours, errors, and cost.J Gen Intern Med.2005;20:969–970.

- ,,.Intern curriculum: the impact of a focused training program on the process and content of sign‐out out patients. Harvard Medical School Education Day2004.

- .When conversation is better than computation.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7:277–286.

- ,.Communication behaviours in a hospital setting: an observational study.BMJ.1998;316:673–676.

- ,,,.Integration and beyond: linking information from disparate sources and into workflow.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2000;7(2):135–145.

- .Update on the electronic medical record.Otolaryngol Clin North Am.2002;35:1223–1236, vii.